Tone Glow 174: Daniel Blumberg

An interview with composer Daniel Blumberg about recording improvised music, how microphones became an integral part of his practice, and making the score for Brady Corbet's 'The Brutalist' (2024)

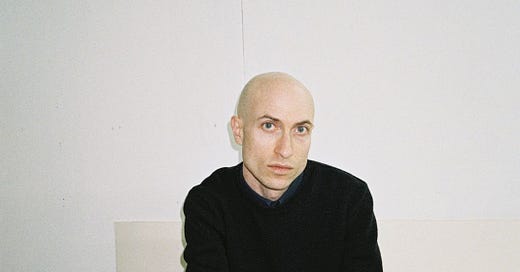

Daniel Blumberg

Daniel Blumberg (b. 1990) is a multi-instrumentalist, film composer, songwriter, and visual artist living in London. He has released numerous solo albums, including Liv (2014), Minus (2018), On&On (2020), and GUT (2023), with a trio of core collaborators across records: cellist Ute Kanngiesser, violinist Billy Steiger, and bassist Tom Wheatley. The latter three records were co-produced by award-winning record producer Peter Walsh. A mainstay of the city’s iconic experimental music hub Cafe OTO, Blumberg plays fluidly with a host of kindred spirits that intermittently coalesce as duos and quartets. He has performed under the projects GUO (with Seymour Wright), BAHK (with Elvin Brandhi), and VAKA (with Joel Grip, Antonin Gerbal, and Elvin Brandhi).

Blumberg is a self-taught artist whose eclectic career has traversed the terrain of intimate piano balladry, folk-inflected innovation, and free improvisation, and whose wheelhouse encompasses slowcore and avant-rock sensibilities. His songs simmer, manic and melancholy in equal measure, given over to the hysteria of strings and the meandering groan of Steinberger guitar, but always suffuse with the lucidity of his vocals and the good humor of his lyrics, which ring out a strange wisdom accompanied by trusty harmonica. Blumberg’s idiosyncratic figure drawings have graced the covers of nearly every album, and comprise a prolific art practice that has seen the artist exhibited in major art institutions around Europe.

His early love of cinema, his deep friendship with film director and actor Brady Corbet, and his grandiose sound palette have nurtured an ever-expanding creative life in the film world. Blumberg has composed music for Agnès Varda’s retrospective “Gleaning Truths” (2018) from Curzon Cinemas and the British Film Institute, joined forces with Peter Strickland on the short film GUO4 (2019), and scored Mona Fastvold’s feature film The World to Come (2020). The past years, Blumberg has been engrossed in composing an instant-classic score for The Brutalist (2024), Brady Corbet’s great American epic about a Jewish-Hungarian brutalist architect who survives the Holocaust, emigrates to Pennsylvania, and becomes entangled in a discordant, decades-spanning relationship with a wealthy industrialist patron. Unsurprisingly, Blumberg is up for Best Original Score at this year’s Oscars.

Elise Schierbeek spoke with Daniel Blumberg over Zoom on January 27, 2025. They spoke about working with artists one admires, capturing improvisation in recorded form, and the demystification of the filmmaking process.

Elise Schierbeek: Good afternoon slash good morning, here.

Daniel Blumberg: Yeah, I’m good. Whereabouts are you?

I’m in Chicago, so morning my time. How’s your day going?

It’s alright. Yeah, just a bit slow. I mean—(laughter).

All good.

To speak on the phone in the mornings at the moment, all the time...

You prefer night, for phone? Oh, you’re always on the phone in the mornings?

Yeah, no, just at the moment, because they’re putting out the [The Brutalist (2024)] soundtrack and stuff. I prefer nights for working on music. I was literally just tidying up because I’m doing a recording session over the next few weeks—but probably months—for something, and I was clearing stuff out and I just found my copy of Humboldt’s Gift (1975).

Oh, what is that?

It’s [a novel by] Saul Bellow and it’s set in Chicago. I was given it. Do you know David Berman?

Not personally (laughs), but I absolutely know of him.

Yeah, he came to my show in Nashville and gave me this book, Humboldt’s Gift, years ago. And then I read it when I was in Chicago.

That’s amazing. And it just kind of turned up this morning? A little kismet.

I was just holding it and thinking of Chicago, but I didn’t know that you were going to be [in Chicago].

I’m glad you held Chicago in mind. I saw you were at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, introducing The Brutalist last night. Had you introduced the film at screenings this year?

That was the first time I’ve done one not in America. The first one was in New York for the New York Film Festival. And I’ve been to Los Angeles a few times for Q&As with Brady [Corbet], but it’s not my natural habitat. Last night was the first time that it was actually quite nice to just talk about the work. The ICA’s relatively local.

Was Brady there?

No (laughs). I was with him the night before and we were drinking and I kept saying, “Come to the Q&A!” but I think he’s just done. He was like, “No!” (laughter) because it’s sort of this full-time thing for him at the moment, all the press and stuff.

You’re like the understudy, you can just swap in for him. You kind of had a director role for the film, or the level of coordinating parts seemed on par.

It is interesting, the sort of crossover of certain things. You know, one of the things that I was talking to [Brady] about recently was how just because of the nature of stuff, they normally just put my name [in the credits], and obviously I instigated it and wrote [The Brutalist score], but it was a massively collaborative project. There were like 20 musicians, and I worked very closely with Pete Walsh on it. When you see your name only, it always feels a bit weird, but that’s an example of what Brady has to go through but on a huge scale because he’s obviously working with so many people, hundreds of people—a scale more than I can imagine.

It’s so social, such a web of relationships with both of these roles. And having to be the insurer of trust across all parts.

Yeah (lights cigarette). Yeah, definitely. I think all those things were just getting the work done without any compromising. And then I think, for Brady, he’s just happy that it’s actually in cinemas.

There’s such a risk nowadays that a film will barely have a run.

It’s crazy. But the thing is, I went to the ICA yesterday to do this Q&A and it was sold out. And people turned up for the Q&A. But then I remember doing something a few years ago [at the ICA]. It was just this sort of idea that I worked on with my friend Yuki [Yamamoto] for like two days. It was a lot of work and we did it. And there were about 20 people there and we didn’t get any feedback. That was an occasion where you try something and you learn from it, but you’re not sure if it’s entirely worked.

The people weren’t ready.

No, no. It’s just funny the different scales of audiences and feedback, but I’m definitely used to getting no feedback. I have friends who make extraordinary work visible to very few people. So, it’s interesting to see Brady’s film access this wide audience.

I have a mentor who says, you know, you ultimately make work for like five people. Those five people, you really care what they’re going to think and you just have to accept that it will have a broader audience. Do you have a little cadre? Brady seems to be one of them. I’ve read that he’s listening to your mixes before they’re mastered.

Yeah, so like Brady, Seymour Wright—the saxophonist, he’s in [Ahmed] and he’s an amazing solo artist as well—but he’s someone that I always play stuff to. With The Brutalist, we talked endlessly about it. Sometimes I put “consultant” in the credits (laughs). But yeah, there’s definitely a few people, then definitely myself (laughs). Generally, I try to get to the end with everything having been investigated that needs to be, and try not to get to the end and think, “Oh, I should have done this.”

It feels like you and Brady knew that the film would be pretty major. I am curious how you got to such an interesting composer-director relationship, having met during pre-production of The Childhood of a Leader (2015), and now getting involved at the very beginning of the conception of a film.

We met, we had dinner in London, and then we went to Cafe OTO. I took him to OTO because we got on straight away. He was putting his film together. I remember reading—they call it like a bible, or something, when it’s not the script. It’s just sort of who’s working on the production and maybe some images. But I just saw [the name] Scott Walker and I thought, “Wow!” because I’d seen Scott had done a film. I knew Scott had done Pola X (1999), which is one of my favorite films—the Leos Carax film.

Brady’s very into music. I think it was over ten years ago that we met. But I was massively into film and still am. We just got on very well and then I took him to OTO and then ended up coming here. He slept on the sofa in my flat. We became very close immediately and always have talked about our work. I went to the scoring sessions for his first film [The Childhood of a Leader]. Well, I went to the brass session for his first film and the string session for the second film [Vox Lux (2018)]. When I did go to the set, we would always talk on set. We’re just very close. Obviously he’s a director, but I’m used to collaborating with people with music. He’s someone I had an instant affinity with and it was quite natural to work together. I work with a lot of very close friends.

It seems like your collaboration stemmed from a friendship more so than just being similar artists or working in similar ways. Do you gravitate toward the same ideas?

It’s great having grown together over many years, like introducing each other to music or films. The reason we have similar tastes is also because of the time we spent together or experiences we shared.

That makes sense. So you met Scott Walker and that was when you also met Walsh?

I was surprised to have been invited because I don’t have people in my sessions at all. The way I work is a lot about the direct communication between me and the musician. So, if people come here to work, we might make progress on what we’re working on just by having a coffee or spending time together. That was an orchestral session and I was quite surprised that I was able to go. It was very interesting to meet Pete at that time in my life, or to see Pete working with Scott, because Scott is a very different artist from me in the way that he works. One of the things that I found interesting was the communication between Pete and Scott, and then with Mark [Warman], who was the conductor, who also worked with Scott for many years. I saw Pete working and thought he would be really... I sort of knew. Not in that moment, but when I was putting together my next solo album, I thought of Pete, and we’d got to know each other after that, going to that session.

At that time, I was really only working at the project space in OTO, so when I was making music, it was always improvised music. For about five years, I was very uninterested in songs because I’d fallen in love with improvised music. And I just thought, why would you corner the listener with, like, a lyric, or… I just thought songs were silly. I definitely don’t anymore. At that time I was playing improvised shows in gallery spaces or smaller spaces in London. And one of the things about that was the recordings. Even in the flat here, we’d play quite a lot. I’d play regularly with people here, and we’d normally record on a cassette. I have a really nice Walkman, like one of the later kind. I think it was the last Sony Walkman, so it sounds really beautiful, the recording. I think it’s like when I listen to the—I can never say the name—Les Rallizes Dénudés. When I started using that Walkman, I thought, “Maybe those records were recorded on that.” But anyway, a lot of my friends or people that I was working with, when you’d hear their recordings, they were kind of Zoom recordings in a concert environment. You know, those little kind of—even this (holds up small portable recorder). Not this, but the the bigger kind of Zoom.

Yeah, like the Zoom H4n?

Exactly. When I signed to Mute [Records], I was very curious about making a record with the people I’d been working with but recorded very well, actually capturing these mad dynamics that they work with, with their playing, and thinking about how those should exist in a recorded environment rather than a live environment. I have friends who release records and it’s from a show they’ve done. But with Pete, I thought it’d be interesting to really work on capturing those dynamics that you hear.

Like Seymour, for example, when he plays. I remember seeing him in Paris once with Jean-Luc Guionnet, who’s an amazing saxophonist, and another guy [Pierre-Antoine Badaroux]. They did three saxophone solos and it was the most extreme music I’d ever heard. I mean, I literally thought my ears were going to break because they were doing a lot of, like, moving the sound around (rapidly pans hands back and forth from his ears). Like, really quickly around the room. And it was acoustic saxophone. So that was definitely something that appealed to me working with Pete. And I’m very happy that we started working together because it’s been very productive and now recording is a massive part of my work creatively.

When did microphones become integral to your practice? I’m thinking now of your gallery installation, actually, sync (2022). Did that stem from work with Pete?

There were two elements. I think he’s an incredible mixer. He’s just such a talented mixing engineer. And with those Scott Walker records, it was balancing very complicated sounds in a very musical way. And then my work, my sort of sounds (or the musicians I work with make sounds), where you have to look in the mix from sort of a blank canvas to see how they go… you’re not just like, “Oh, the drums are there, the bass is there, the electric guitar, or the saxophone’s there.” You have to start from a blank canvas. When I started working with Pete, it was the first time where I was really asking, “Oh, why that microphone?” I remember we rented these Schoeps. He wanted to rent some Schoeps, which are beautiful German mics that are used a lot for recording classical music and jazz, actually. And they’re very good for film dialogue, as well. But yeah, my mic case, I have a suitcase—(gets up to visit equipment shelf).

For The Brutalist, I just had all my mics in there (gestures toward the lower compartment of a silver suitcase) and then the recorder in there (gestures toward the upper compartment of the suitcase). The recorder’s like this (holds up stack of equipment, the SONOSAX SX-R4+ audio recorder and the SONOSAX SX-AD8+ preamp). That’s, like, my studio. All the mics, they’re either Schoeps or U89s, which are a specific Neumann that has lots of different polar patterns. I started getting interested in [microphones] and asking questions. I hadn’t even really recorded. I didn’t even know how to use Pro Tools before I met Pete. And he’s someone where it’s very natural, teaching or explaining things. It’s very natural to him.

The piece with Lydia [Ourahmane] at KW [Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin]. We did it and we did the Venice Biennale this year, as well. We were using this microphone called a Schertler, which I used for the initial prepared piano sessions on The Brutalist. It’s a very high end contact microphone—it has a lot of contact. Some people have experiences with contact microphones where they’re quite noisy. These were designed by someone for his double bass—this Swiss guy [Stephan Schertler]—and they were very successful at capturing acoustic instruments. They’re phantom powered and they have a big dynamic range. The idea to mic the heart with those came from my results from mic’ing the piano. I think Billy Steiger introduced me to Schertler. He’s the violinist I work with. And, actually, at the ICA show that I said we did years ago, I used Schertler to mic up a piece of wood. To draw. I was trying to get the sound of drawing, and I was drawing on wood. They’re interesting contact microphones.

I’ve been curious how that kind of gallery work cross-pollinated with the production of The Brutalist. Was Lydia involved with any of your work on the film?

Yeah, Lydia and I had done a project that sort of evolved into sync, but we started with hydrophonic microphones—hydrophones, underwater microphones. And then on The Brutalist, she came with me to Carrara to record the impulse response. She was actually the one shooting the gun [to capture the reverb pattern of the quarry’s valley]. She was actually quite fundamental to that. I couldn’t go on the set because it was such a small crew. And when I saw the images of Carrara and the marble and sort of imagining how sound might move in that space, I was desperate to go. And she’s a conceptual artist. Someone asked me the other day, how did you end up in the quarry with a hard hat and a gun? And that’s one of the amazing things about her work, is that she makes these strange things happen.

We worked on a show together as well. She had a show in Milan at a similar time, so we sort of combined the trip. Her show [Polvere] in Milan was using that reverb. Ordet, where she had the show, there was someone who had something to do with the marble quarry. They have some art programs with the marble. Practically, we combined those two things to make it happen.

The impulse response ended up being routed with Evan Parker’s sax?

Yeah, yeah. His saxophone went through the reverb.

What made you think saxophone for Carrara? There’s obviously, like, a vertigo, but there’s almost a nice clash with the austerity of the quarry. Did you immediately think, yeah, it’s going to be sax?

I’m always zooming in to a film. I’m always zooming really hard into it and then always zooming out. It’s almost like thinking about it as a song. There’s different choruses in the song, with the themes. So, having this sort of balance. The first thing before he goes to Carrara, the character László, he packs up his heroin in the bathroom in New York and that’s the cut before Carrara. Most of the film is brass and piano. The appearance of the saxophone first happens in the jazz scene.

We were trying to evoke the forties because Adrien Brody’s character, László, and Isaach de Bankolé’s character, Gordon, go and listen to jazz music and that scene is like, it’s Joel Grip on double bass, Antonin Gerbal from Paris on drums, Simon Sieger from Art Ensemble of Chicago—he’s a younger player, he’s on piano—and Pierre Borel who’s an incredible saxophone player from Marseilles. And they all came to play on the set. And the idea for the scene was that there would be this kind of—Brady described it as like a George Grosz painting—like this really dynamic bar scene with a live jazz band. And then [László and Gordon] go and shoot up heroin in the toilet. So, the music would still be coming through the wall.

The third chapter is them coming back in the room high. Brady wanted to shoot it with this in-camera [effect] with VistaVision, where you can sort of trick the camera to stretch the light out in this quite specific way. I wanted the music to be played and for that jazz to kind of be deconstructed into this quite woozy, more abstract piece. I got those musicians specifically because I know them from improvised music, but they also can really play jazz. So I associated that saxophone with the heroin. That was just a small instinct for Carrara. It’s all these different bits of information Brady and I use to decide the events of the score.

They were performing that jazz set live, and both parts, played straight and played heroin-ed out. Was any of it improvisational?

It depends what I’m doing, but with something like that, I try and bring as little as possible to a session. I had the theme that I wanted [the players] to play because I wanted the theme to relate. Later in the film, there’s this construction theme where the building really starts getting underway and it’s got this theme of, say, doo-doo, doo-doo, doo, doo, doo. I wanted that melody to be implanted in the character’s mind, as if he retains that theme. It’s such an amazing experience that he just never forgets it. I brought them the theme, told them the era, and showed them—because this was at the start of the shoot—I showed them an image of the camera test of the effect. Then, we talked about length and how long it might be, and then they tried something. We worked in a studio the day before, which was actually like—I pulled out everything in the studio to plug in my mics—more like just finding a space in Budapest to make it work. I would give feedback: “Go to the theme more often... Come out of it...” It’s a conversation, it’s a dialogue.

There’s a reason why I’ve asked specific people to play. It’s because of the way they play. It’s not reading music. That’s why the scene has that atmosphere. It’s actually happening, it’s unfolding. If there’s an element of improvisation—obviously, there were limitations on that, but there’s always limitations on improvised music anyway—we definitely wanted to retain the quality of what the characters would feel like going into this place and seeing people actually playing. I’ve worked with Joel Grip probably the most out of [the players], and Antonin. I have a quartet with them, an improvised quartet [VAKA] with a singer called Elvin Brandhi. So, there was a shorthand with those two. I’ve known Pierre, and Simon I got to know through this project, actually, because he played a lot of the tuba. He was the lead tuba player on the film.

It’s amazing that you all got the opportunity to affect the set. You did the prepared piano for the overture ahead of the production at Cafe OTO. Did you know that it would become a blueprint for the film’s opening minutes?

That was actually for a teaser Brady made very early. It was way before production got underway with the film. He made a teaser in Venice to try and raise money for the film. It was when we were premiering The World to Come (2020), which is the film I did with Brady’s partner Mona [Fastvold] before, and it was during COVID. They had the [Venice Film Festival], and Brady saw it as an opportunity to shoot in the Giardini [della Biennale] and shoot on [35mm film] in Venice. It was just loads of favors. The festival helped him get access to the Giardini. I worked on it as an excuse to get my head in a bit to the project and experiment a bit with initial sonic ideas. (Blumberg rolls a cigarette). Brady also used that footage in the end, for the epilogue. That gondola going through Venice is really useful footage. It was COVID. The streets were empty, so he didn’t have to pull out people on their phones or any modern people walking around. It takes part in the eighties, that part of the film.

That piece of music actually became the construction piece, but generating it was this day of just recording for that demo. When you’re doing prepared piano, you never know exactly how it’s going to sound. I had 16 microphones on the piano, experimenting. I did it with Tom [Wheatley] and Billy [Steiger]. Tom Wheatley played a bit of double bass on the film, and Billy normally plays violin when I work with him. We were just putting stuff on the piano and then seeing how it sounded and then putting different microphone formations on it. So for example, I was really excited about the low end because I had one of those contact microphones, the Schertler, and I have these two U89s, which I use for vocals and brass and everything. Two on the different parts of the piano. Getting really big stereo images of these sounds, it almost became, like you said, a blueprint. I had those as samples throughout the process. When I went on set, I brought this little keyboard, one of the things that was at my fingertips for all of those samples. When I was watching the monitor, sometimes, I could play with those sounds. I made the demo for the overture with those sounds that we recorded at OTO. That’s quite different work. One of the technical processes that was very new to me was using a click and having things on a grid, having a tick in your head.

Like a metronome?

Metronome, yeah. (Blumberg seals his cigarette). That’s very different from how I work normally. For this project, for some of the cues, I wanted to retain that sound of people playing, and other cues it’s a desire to have this quite built sound. The overture, it’s built, but also… like with Sophie Agnel, the pianist who played a lot on the score, she’s from Paris and she plays just the strings of the piano. She plays the strings, she doesn’t prepare the piano. She plays the strings with various objects and the sound obviously has a relationship to the prepared piano, but it’s a very live energy because she was listening to the track and responding to it. That gives it a sense of being performed, as well as being a very meticulous, constructed thing.

When the cast and crew were hearing the demo, was it transmitted via speakers to the whole set or is it just in [cinematographer Lol Crawley]’s headphones?

With the overture, I did a demo before. I had the date they were going to shoot it, and I was staying with Brady in Budapest. We spent some time where he was sitting next to me and explaining how the scene would unfold, just for timing. So he would say, “Oh, and then László goes up the stairs, and then he looks out the window, and light shines in, and then he goes up. Up, up, up. And then they open the door.” I was sort of taking notes about what would happen. With that demo, I informed the length of that oner, that one-shot, because they then shot it to the demo and it was played out on huge speakers on set. Because it was handheld, I had to be in the room at the top of the boat. I was watching on a little monitor. It was a one-shot, so everything had to be sort of choreographed. I think I’ve got a photograph of the situation (pulls up photo on phone). This was the ship (shows photo of walkway leading down to the ship from The Brutalist set, and then pulls up another photo in which two people sit beneath the set’s monitor screen). I was sitting next to the makeup [crew]. Yeah. So like... (taps to zoom in on the monitor in the photo).

You’re manning the ship.

(Holds zoomed-in phone picture closer, revealing a monitor that shows Adrien Brody acting). You see, in black and white. But yeah, I had headphones on, so I could hear the set. When you shoot, all the actors have mics and normally they would have recorded the bustling of the extras and all that stuff. But because it was so loud—the music—it had to be replaced because the demo was going into all the microphones. The sound mixer, Steve Single, who I worked with quite a lot throughout the process, he then built the sound for that scene. It was a real coming together of departments because the cinematographer was moving to my music and Adrien, and then the sound mixer would sort of respond to their movements and the music, and then I would get a mix from the sound team and Pete and I would have to work out, “Okay, the low end of the piano is interfering or confusing the sound of the waves, but is that good?” It was really interesting in post-production, months later.

There’s kind of an imperative to sample sounds from architecture and construction, but I imagine you were trying to avoid literalism. How did you balance that with the sound designers or Foley artists?

(Smokes cigarette). Well, when I saw the first cut of the film, there was one idea conceptually that I was excited about. These ideas are sometimes interesting to follow through but then don’t work, but this one was a good one. It was this idea that these elements of sound that you start hearing through the second half of the film, these little spurts of trumpet or piano, would formulate into the construction montage. It’s like a little collage. During the second half of the film, on the construction site, you’ll hear a trumpet or a piano, and then it literally became the construction, the nuts and bolts of the building. And one of the things that Axel [Dörner] was doing, was he had two microphones and he did this sort of drill sound (trills lips to mimic drill sound, pantomimes trumpet playing) on the trumpet.

The two microphones correspond to the left and right. So it’d be like this (pans hand across body, trills lips) on the trumpet, and every time László was on the construction site I’d use these sounds that I did with Axel. Simon, who played tuba, also did some amazing sounds. I think I’ve got some videos. It would just be a part of the session where I’d say, “Can you see what you can do in terms of construction, drills and banging and stuff like that?” Then we had this sort of library, Pete and I, of these sounds. Steve Single, the sound mixer, would have—by the time [he got] the premixes—the dialogue, the sound effects, and then the music. And by sound effects, I mean, including Foley. There was definitely overlap with Foley and some of the sounds that I was recording (pulls up phone video of Simon Sieger playing tuba in a living room).

I love how many kitchen, studio, and home recordings went into the score.

Yeah, that was my friend’s flat in Berlin where I did a lot of recording. We did a session in Berlin because Axel was based in Berlin. I had my set up here on the table. (Shows photo of his computer and recording gear on a table and Simon Sieger playing tuba in the background). Just these recorders, and then found a nice sounding spot in the living room. That place sounded nice because initially I stayed there and was recording at Joel Grip’s painting studio. I just thought, “Wow, this room sounds great.” I went back to do the jazz in a studio around the corner to get that sound of people playing together… Oh, yeah, that’s nice. (Plays video of players playing upright bass and open lid piano in a small studio). So yeah, this was in the studio.

It’s movie magic. You’re taking these small spaces and turning them into something gigantic. I remember reading, about a decade ago, when you found yourself on the set of Nymphomaniac (2013), that you were happy to be ignorant to the process. Are there things about film that are still a mystery to you?

The Nymphomaniac set was the first set I went on because Stacy [Martin], who I was with for 14 years, that was her first film. She wanted me to be there. I’d just done a record in Denver. And I felt like when you finish a record—you feel quite relaxed. I really got on with Lars [von Trier]. It was amazing to spend a lot of time with him and Manuel [Alberto Claro], the [Director of Photography]. The first time I met Lars—I can’t remember—we were having dinner and someone asked what my favorite film was and I said Peter Watkins’ [Edvard] Munch (1974). And Lars was just like, “Yes!” We really got on and Brady got on very well with Lars because he [starred in] Melancholia (2011). Lars was very generous with me and Manuel as well. Manuel saw the Oscars thing [recently] and texted me, and I was thinking of being on the [Nymphomaniac] set with him because I was just asking so many questions. I remember [Lars] giving me his chair to sit next to the monitor. He was just very generous. He actually got me to record an answering phone message to Stacy in the film. (Pantomimes a phone call). Oh shit, Brady’s calling. One sec. (Blumberg briefly says hello to Brady).

But yeah, [being on set] was cool. It was amazing, actually. I was worried about demystifying something. I’ve been on sets over the years. Particularly Brady has always been very communicative about the process. When he was making his first two films, maybe even [he had me] to whine to, or unload to, which I have with my work, as well. People where I can just say, “This is really hard,” or they can see it from a different perspective.

I spent a lot of time on the set of The Brutalist. There’s very practical things, like the jazz band. I was giving them notes during the performance. Then there’s other scenes. I was playing the piano for the train station scene to give the actors this sort of feeling. And then with the Jewish prayer scene, which turns into score, I was literally standing behind the camera with a keyboard, giving them the notes, so that it would be in the right tuning for me to be able to work with [the recording] afterwards. Also, being able to work with Adrien or the extras. Knowing the rhythms was useful because, especially on a film like this, you can’t say, “Could I have two minutes to work on this?” It’s so tight with budget. I just did a musical which was like that to the extreme. I had to be on set all the time for two months and no one really had done a musical before, apart from Amanda [Seyfried], the main actress, who had done Mamma Mia! (2008).

(Laughs). Oh, Amanda Seyfried.

Yeah. She’s the star of the musical.

Is this Fastvold’s next project?

Yeah. Now, for example, with the demystifying thing. I was nervous about that because film was a big part of my life, watching films, and I was worried about it being ruined. But still when I watch something I love, I don’t pay attention to anything. It was always the most experiential thing. It was like everything beyond the frame of the film is just dead. It’s just the film. I’m just in the film. I love that about cinema and it’s still the same. I never used to come out of films that I love thinking, “Oh, that’s a great performance” or “that’s a great score.” And still, I don’t even really hear the score sometimes when I’m watching something I love.

The Brutalist is such a smoking film.

(Lights cigarette).

It’s one of those movies that makes you want a cigarette, or you want to count how many times they take a drag.

It was annoying because I stopped smoking for a few years and then I think it’s crept up a bit because of the process of the film (laughter), including watching Adrien smoke over and over again. When you’re working with the picture finally, you’re just watching someone smoking.

Those period-accurate cigarettes that were so crumpled throughout made me want a cigarette every time. Did you smoke with Adrien?

I don’t think he smokes.

I suspended my disbelief too much.

You know, he’s not actually László. Like, he’s an actor.

Oh! Okay! (Laughter).

Brady is someone who likes to bring people together. Everyone’s different with their shoots. Brady likes to have dinner together with everyone. But Adrien was very, very focused on the film. He would go and study in the evenings and he was really committed. All actors have different ways of doing things. He wanted to be focused all the time, he was so committed to it. I was really impressed. It means a lot to me because, in the context of Brady’s work, if anyone’s not invested in it, I get so offended because I know how much pain and weight goes into it. You know, I’ve sat on his sofa in New York with him sort of [going like this] (puts hands to his head as if in agony, laughs). The idea of someone turning up and also thinking it’s an important thing to make well is moving.

It seems like you went to great lengths to gather the dream team. Throughout your life, you’ve found ways to work with people you admire. From a young age, there was Kurt Wagner, Niel Hagerty, David Berman. And then later, Keiji Haino. And working with John Tilbury on The Brutalist. Can you speak about obsession with other artists?

I don’t think the word obsession is right. I think with footballers, soccer players, they’re just sort of these other aliens. I’ve seen footballers in real life and I just melt. That’s my understanding when people say “starstruck.” I get so starstruck, there’s no point in me even... I was at Frieze in London and one of the footballers that I’d seen the night before playing was at Frieze. It’s like this art place where people go every year. All these galleries show their work. I could not believe that he was just standing there. And my friend said, “Go and say hello.” And I just went up to him and said (croaking), “Hello,” and then ran away really quickly. I went so red.

But no, I mean, John Tilbury. I had a festival with him in Switzerland and we had dinner a few years ago. We had dinner together and actually we mostly spoke about football because he supports QPR [Queens Park Rangers Football Club] and I support Tottenham [Tottenham Hotspur Football Club], but we got on really well and for a long time on The Brutalist, so we’re very close now. I think sometimes when you admire someone’s work—well, in my case, I’m sometimes not surprised that I connect on a human level because I connect to [someone’s] work. Billy Steiger is someone that I work with and he’s one of my closest friends. I really think he’s one of the greatest artists of our time. His shows are really surprising and they’re just extraordinary experiences. And people don’t really know his work. He released a solo record on OTO a couple of years ago that I recorded with him. I admire him as much as someone like—you know, I mean, Lars von Trier is different because he’s made lots of work, or—like John, who has made a whole body of work.

When [Tilbury] agreed to do [the film], it meant so much to Brady and I because we’re young artists and I definitely was aware when I was working with him that I was learning a lot. It’s the same with Pete. I feel very lucky to be able to work with him because he’s someone that has a lot of experience that he can share. That is something that I really value, working with people that are from other generations.

There’s an element of mentorship.

Definitely. I didn’t go to school or learn music at school. I mean, I’m a school drop-out. So that’s how I’ve learned. There was a video shop in Stoke Newington, the DVD shop that closed down a few years ago. When I moved here, I would go there multiple times a week and speak to Alan who worked there. He was someone who introduced me to [the films of Robert] Bresson. In my mind, that’s like this incredible thing that he’s given. I see him in the park sometimes and it’s like seeing someone who’s just given me loads of presents (laughs). Seymour’s recommended me amazing books. That’s basically my life, the work I do, apart from watching football. Well, not football, but Tottenham. If I’m spending all my time making work, my aim is for that to be an experience that I want to spend my life doing. So if that’s drinking wine with Axel Dörner… You know, that was another amazing person that I spent a lot of time with during this process… I was very aware that [The Brutalist] was an important project and I get to really work with someone I love with Brady.

I’m thinking about the nontraditional education, and I do want to know how you got to Nashville when you met Berman. What brought you to that kind of mentorship situation?

Well, that was really when I was young. When I started making music, I started a school band [Cajun Dance Party] and I was signed and then I had another band [Yuck] and then we were signed. Now there’s enough distance to look back on those things with a bit less embarrassment. But I would hate the music I’d made because I was growing and changing taste and it was sort of unbelievable. It was like a huge weight. I can’t believe I shared [those projects]. It’s like writing a poem when you’re 12 and it being published or something, you know? It’s like, really? And Brady had that as well with Thunderbirds (2004). He started as an actor when he was very young. I think when he was very young, he was a cinephile. I think I was 16 or 17 when I started reading and having my own taste. It was even after I started releasing records. I got into music. But Nashville, I’d been introduced to Lambchop and Bonnie “Prince” Billy. Mark Nevers in Nashville was making these records that I loved. So I asked him to produce an album of songs because I’d written some songs on piano, which now sounds like a teenage diary to me.

I was a fan of Oupa. I can’t lie, I loved those ballads. Is there a lost Lambchop collaboration?

There’s a Low album. I did a record with Low that hasn’t come out, that hasn’t been mixed. There’s a few records that I’ve made that haven’t been released and one of them’s with Alan [Sparhawk] and Mimi [Parker] in their house in Minnesota. We made a record together, which is beautiful, but I think we’ll release it one day. [It was recorded] before I did a record called Liv (2014), which in a way I feel is my first. You know, when artists have a catalog résumé (in terms of visual artists), there’s a moment where they decide their work starts. And so for me, that’s Liv, where my work started to actually... Before, I’d started very young. It was one of the reasons I stopped releasing records. I actually just wanted to get to develop more as an artist. Then naturally, I just was making stuff anyway because that’s sort of what I do. But Liv was the first record. I always have problems with albums that I’ve made, or think, “That’s shit.” That’s cool that you know those records. I have a friend called Kohhei [Matsuda]. He actually played synth on Liv and I saw him in London. He had moved to Amsterdam, and he still listens to the Oupa record.

Liv came out, and then there’s a single from that period, “Family.” It was spinning for me this year. It’s cinematic.

That’s one of my favorite songs I’ve ever made. Liv got released four years after it was made, but between then was this record called Minus (2018), and “Family” was part of that. There were a few songs off Minus that didn’t make the actual cut of the record, and “Family” was just part of that record, basically. When you sequence a record, it’s like making a film. You might have a great scene, but it’s just not adding to the whole of it, the balance of the dynamics of the record. It just wasn’t right. And, you know, there’s definitely more. I’ve got like a 40-minute song from that album that didn’t go in it. Just didn’t want the record to be two hours (laughs).

Yeah, not ideal. You could do a Brutalist: Hey, pay attention.

The Brutalist has a lot of recordings that I love that are not on the film, just because of the way that I work. I’ve got a lot of recordings with John. It becomes so much about the scene. That’s why the intermission was really beautiful. It’s my favorite piece of music on the film.

Did you know going into the session with Tilbury that it would become the intermission?

John was the first musician I thought of for the whole film. For years, I waited to ask him to do it because you have to ask people at the right time. The whole production can be very confusing if you don’t know how films come about. Really, it can take years. Then you don’t know how the shoot is going to go, and whether the music is going to have a different responsibility. So I had to wait so long to ask him to do it and I was so happy that he agreed. And the same with, like, Sophie. And it was nice working with Vince Clarke as well, because I’ve never worked with him before.

Did you jam out together?

Yeah, we worked together in New York, and then I brought it back and Brady and I actually finished it in London, in that room (points behind his shoulder). I have a Moog, and Brady and I just had one of the funnest nights. It was so nice to do that because post-production is very stressful in terms of deadlines. He had so much VFX [visual effects] and it’s just a lot of work. It was almost like they tricked everyone. I mean, I knew, because I’d read the script, and it’s long, and it has an intermission. But it was scheduled as shooting a film, not two films (laughter). He had a lot of pressure on him to make it two and a half hours after he’d cut it. That was a big stress, as well, for him to navigate.

Were you involved much in the edit suite, seeing the visuals come together?

Day to day, the edit is Brady and Dávid Jancsó. But I’m in there a lot, yeah. In my last film [The World to Come], I was in the edit a lot. The more peculiar situation [with The Brutalist] was that I was very involved with the sound mix, in the sense that it was a dialogue and I was in the room. For example, I would go into the sound mix, be in constant dialogue with the sound mixer, Steve, and he was very supportive of the way that I was working. It’s not necessarily how things are done. You’re normally meant to give stems and then just fuck off, but Brady was very encouraging of all of us being together on the last day. The big mix on the last few days was in a cinema in London. We were really, not arguing, but trying to work out a fight between the dialogue, the music, and the sound. They wanted to dip the audio so you could hear this Hungarian dialogue and I was like, “There’s subtitles on there anyway!” (laughter). There’s a crescendo in the music, you can’t just dip it. Then you have this conversation and you’re like, “Okay, well maybe you can dip the high end, but keep the low end because the dialogue is in the sort of high-mid frequencies” and it’s those types of things. The fact that people are responding to the overture, I think those are the sort of details that help the audience feel.

I’ve talked to multiple people who say, “You know, I haven’t seen The Brutalist, but I keep running that score.” Did you expect the score to have a life of its own?

As someone who makes records meticulously—and I drive Pete mad when we’re mixing—you have to take a step back. The thing that I say to myself is that the scene happens and then there’s another scene. The audience doesn’t listen back to the track in the cinema. They don’t say, “Oh, what was that? I heard some... I’m going to listen...” I was a bit nervous about doing the vinyl or the soundtrack afterwards. We’d had a few months of break, Pete and I, because our mix was so intense. It was just every day, ten ’til ten. And then I’d have to go and speak to Brady into the evenings, into the night. You know, Brady would call me at midnight, and then I’d text him QuickTime files because he’s working on VFX. It was long. I would go to bed at two and then have to wake up early and then it got longer and longer because it’s just a lot of volume of work. The way that I work is with acoustic instruments. So you’re not moving MIDI files around, and it’s really listening, and it’s very intricate. But when we did the vinyl, a double vinyl is like 20 minutes a side. That’s why the soundtrack’s 80 minutes. It’s cut, it’s less music than I delivered than is on the actual film.

Even the overture, actually, in the film, its parts two and three are actually the same piece, but we split it up for the track so that you could listen to [part] three separately from [part] two. I thought about it as a piece of music for the first time [while making the soundtrack]. I was relieved because it was still a week of tweaking stuff but it wasn’t as triggering as I was worried it might be in terms of reopening these crazy sessions. Sophie Agnel’s piano had about nine mics on it. There’s occasions where her piano… there’s four of them, you know, in the same session, so that’s a lot of microphones.

It’s important to me not to think of [the score] outside of the context of the film. People are enjoying the film. I think that’s one of the reasons why people want to listen to [the soundtrack]. They also enjoy the production design. Collectively, it was a good collaboration. The music’s just something that can be experienced outside of that. You can’t really sit with the cinematography outside of the film. You don’t really have a relationship or platform to engage with other elements of the film.

I don’t really listen to film music. I do listen to [the soundtrack of The] Naked Island (1960). I had to do this list of my favorite five film scores, for BBC the other day. And I was thinking. I never thought about it. There were some obvious ones. I mean, the Charles Mingus’ score for Shadows (1959) or the Art Ensemble [of Chicago] score for Les stances à Sophie (1970). Sort of obvious ones, musically exciting. But then it was interesting to think about Dekalog (1989). I’ve always loved the music when I watch Dekalog, but out of context, I’ve never listened to it. I saw they have the record at OTO—they have a record shop. I saw the Dekalog vinyl a few years ago, and I’d been meaning to listen to it out of context, but I just watch. I watch Dekalog most years, you know, it’s something that I watch regularly.

The big arthouse cinema here, Gene Siskel Film Center, does a series every January called “Settle In” where they show longform works. I missed Dekalog during their first edition, but they did show it in a cinema setting, which is pretty special.

I have seen it in the cinema in New York, and it’s so beautiful because it was made for TV. It was nice to see the print. The last one I saw as a full day thing was Fassbinder’s Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (1972). That wasn’t available for many years. And then a few years ago they showed it at the BFI [British Film Institute] and I had never seen it, and it was so exciting. It was his sitcom. It’s brilliant. I went with Seymour and we watched. I think there’s eight episodes. But the eighth episode was a [scheduling] clash with John Tilbury playing with Ute Kanngiesser, my favorite cellist. I ended up staying for Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day and Seymour went and saw them play. And I actually was talking to John about it because he said, “What’s your favorite?” He didn’t ask it like that, but he was just curious to see what my favorite gig was, because I’ve seen him over the years at OTO. I said my favorite concert I saw of his was the one where I was watching the eighth episode of Eight Hours Don’t Make a Day (laughter).

Split timeline. Do you have a favorite Dekalog episode?

Yeah, I love the first one [Dekalog I].

It is kind of perfect. God and man. I think I like the final one [Dekalog X]. It has a great humor to it, like a dark comedy. I guess you could say that about a couple of the episodes.

The first one I watched was A Short Film About Killing (1988).

What are you watching lately?

Brady and I watched Squid Game (2021) yesterday. That was really funny. I love watching stuff with Brady. I hate going to the cinema with people or watching films with people and they talk. I hate coming out of the cinema and people want to talk about the film. I just don’t like it. But with Brady, I’ve watched films with him for many years and he just talks the whole way through. I love it, though. That trip when we were in Venice together, it was after the premiere of The World to Come. It was after the shoot that we did for The Brutalist. Because it was COVID, we watched Death in Venice (1971). It has that context of everyone walking around Venice and there’s the plague. I can’t remember what plague it is. It’s just beautiful because Brady explains, like, “Wow, that shot, that shot is so amazing because it must be on a dolly, and then...”

Director’s commentary.

Exactly. One of the things I’ve been doing is watching some films related to [Brady’s] next project, or just from the [time period]. I was trying to watch some musicals when I started Mona’s musical. I just watched Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964), which is incredible, but it’s just so unrelated to what we were doing. I was thinking the other day of my favorite film scores. And then I just thought, “Well, The Wizard of Oz is just obviously better than all of these put together.”

Isn’t the Wicked (2024) soundtrack up for the Oscar?

Oh, I don’t know about that. But no, no, the The Wizard of Oz (1939). (Singing) “Somewhere over...” Like imagine someone making that music. It’s amazing. What are you watching?

You know, I’ve mostly been watching short experimental works because I’m co-programming a film festival in April, so I’ve just been spending all my watching time with film submissions. Then, my landlord is one of the voting members for the Academy, and he had to watch a lot of the new releases. We threw on Mike Leigh’s Hard Truths (2024).

Oh yeah!

It was quite good. You know, the only other Mike Leigh I’ve seen is Naked (1993). So it was funny because the main character is a total misanthrope, wreaking havoc on everybody in her life. It’s very, very different from Naked, but there’s some kind of weird connection point across that whole filmography.

Yeah, I’d like to see that in a cinema. I want to see that and I want to see Flow (2024), the animation.

Is there anything else you want to talk about today that we haven’t covered?

Not really… It’s been really nice. I’ve really enjoyed it. The film has gone into this dimension. I went to the Golden Globes with Brady. It’s a slightly strange world. The conversations for that are sometimes quite bizarre. But it’s nice to actually talk about the work or reflect on it. That exchange, I think, is quite rare.

Daniel Blumberg’s soundtrack for The Brutalist is out now via Milan Records. Some of Blumberg’s other music can be found at his Bandcamp page.

Thank you for reading the 174th issue of Tone Glow. Microphone nerds are so up right now.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Amazing work on "The Brutalist". The music really stuck out of me while watching that movie.