Tone Glow 075: Jean-Luc Guionnet

An interview with Parisian composer and improviser Jean-Luc Guionnet

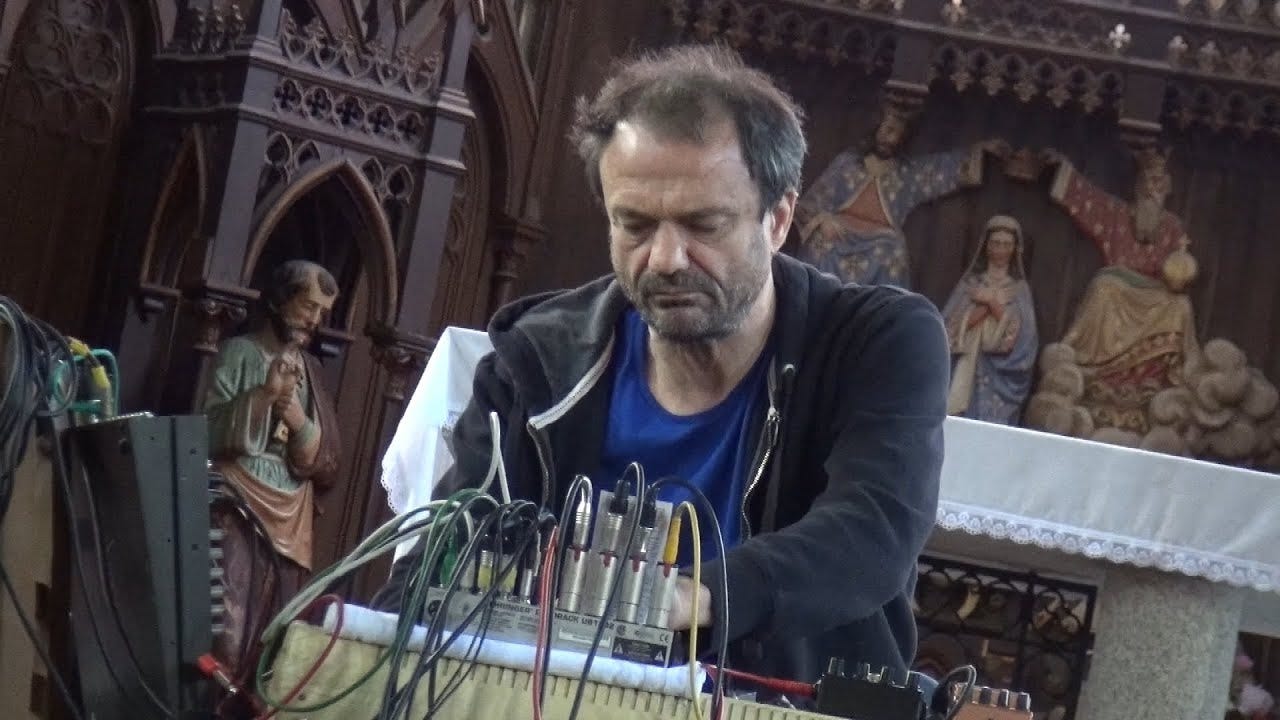

Jean-Luc Guionnet

Jean-Luc Guionnet is a Parisian artist whose practice encompasses composition, improvisation, filmmaking, and philosophy. He has toured extensively as a solo saxophonist, and has spent the past 15 years performing on historic church organs around the world. For him, music is one of many methods by which to test reality. Having studied musique concrète under Iannis Xenakis, his acousmatic sensitivities reveal themselves through the reverence that guides these interrogations. Approaching his instruments as imperfect vehicles of artificial intelligence, his attentive engagement applies speculative pressure to the expressive limits of their material properties. In his hands, design flaws and repressed qualities transform into catalysts for novel sonic emanations, and the simplest of processes are mobilized to extract infinitesimal acoustic detail. Although a formidable solo performer, Guionnet is no stranger to collaboration. In addition to his ongoing relationship to the seminal French improvisation group Hubbub, he has worked extensively with artists such as Taku Unami, Eric La Casa, Toshimaru Nakamura, Will Guthrie, and Mattin.

Sunik Kim talked with Guionnet via Zoom on August 24th, 2021, to discuss problems of improvisation, interpretation, “worldwide stupidity,” anarchic songs, abstraction and concreteness, art and politics, the musical instrument as tool, the microphone as robot, Arthur Blythe, the structure of noise, materialism in music, the struggle between painting and photography, the electroacoustic studio of the 18th century, his 2021 opus Totality, his upcoming collaboration album with Will Guthrie, Electric Rag, and Willem de Kooning’s liver, among many other things.

Sunik Kim: How are you doing?

Jean-Luc Guionnet: Well, and you?

I’m okay! If you don’t mind, I’m gonna record our conversation. Is that okay with you?

Yes.

Cool. So how’s your day been so far? You’ve been on the road for a while?

Actually, I was working on several compositions. I also organize a small series.

Like a concert series?

Yeah, with Lotus [Edde-Khouri], who was there on camera just before.

Awesome! I actually just watched a video of you two...

Oh, yeah.

You on solo sax—yeah, that was very cool. Do you want to tell me more about the series? What’s involved with that? And how long has it been running?

It’s the first time we’re doing it.

Oh, I see.

So no, I don’t have anything to say, more than: We tried something and it went very well (laughter).

Gotcha (laughter). I’m glad to hear it.

We did it in Brittany, in the countryside. We were afraid that nobody would come, but in fact many people came.

That’s great. I’m glad to hear it. So you said you were working on some compositions? Do you work on many things at once? Do you want to tell me about some of those projects that you’re currently working on?

Yeah, the next one... on Monday we will rehearse. It’s a composition for an orchestra from Paris named ONCEIM. The idea of the composition is that I want to make an instrumental version of an electroacoustic piece I did years ago. So I want to translate, in a way, everything into instrumental language. But also with PA, so it’s instrumental, but amplified. I will tell you more when we try. I’ve never done that, so I’m very curious about the results. The idea isn’t to make a “copy,” but to make a “version.” A very different version.

That immediately reminds me of Lachenmann, in terms of trying to do “acoustic electroacoustic” music. Is he an influence of yours at all? Helmut Lachenmann?

Oh, yeah. I like him a lot. But this one… the original was more like a soundtrack, with some kind of text. Actually, it’s close to Totality. It’s like I was translating Totality for orchestra. More than, like, noisy tape. Some parts can be like that, but it’s not the main thing.

I see. Awesome. Since you brought up Totality, obviously, I was a huge fan. It’s one of my favorite releases of the year. I’m curious—I have a lot of questions about it—but since you brought up the question of text: Is an interest in text and spoken word a newer interest for you, or has this been a constant throughout your work, even if there isn’t verbal language involved? Why the emphasis on text? I’m also interested in the durational aspect—but yeah, first of all, what inspired you to gather spoken fragments from all these different people and collect them together?

I think the main thing is the magic. The coincidence. Between this sentence that I recorded a few years ago, which I didn’t write. I just said it like this. I don’t know why. And then the situation at that time was this new situation with the pandemic. But [Totality is] not about the pandemic. It’s more like, what politics can say to give order, to make people do things or not do things… it reminded me of this sentence I had recorded that was on my computer. So I took it back and then began to work on it. At the beginning, the idea was to only use my voice, and I couldn’t manage to do anything. And then a few weeks later, I decided to write to all these people. I said I decided, but I didn’t really decide. I don’t know why I did it. And I don’t know why I’d choose this guy and not this other one.

Do you see that as an improvisational element, in terms of, “I don’t know why I did it”? What do you see as the driving force behind that kind of thinking?

Sometimes I do the same thing in improvisation. In a concert, I prefer to have some arbitrary position, instead of questioning forever. And sometimes, I give up. Actually, that was the point. Given where I was at that time, it was either I give up, because I can’t work with only my voice and I was not happy with it, or I find something else. And that something was to try all these languages. So the title Totality was already there. It helped me, also, to have… a worldwide stupidity (laughter).

That’s great. I love that. I was wondering… I don’t know if you remember what I wrote about Totality in Tone Glow, where I made this very surface-level comparison to Stockhausen’s Hymnen, but in a negative sense—in the sense that Totality, I think, is fulfilling some of the promises of Hymnen, and overcoming some of the limitations of Stockhausen’s political framework. I was wondering if you agreed or disagreed with that, or if you had any thoughts on him in general, or that piece in particular?

No, I agree with your piece. I like Hymnen a lot. But for me [Stockhausen’s] emphasis on romantic positivity about people and nations, blah blah blah blah blah… is something ironical for me. So I wanted to be negative.

Actively negative?

But I didn’t think about it when I did it. I think about it now. I listened to Hymnen a lot and I saw it in the concept. So of course it’s somewhere. But also Alfred Jarry’s Ubu [Roi]. For me, the text, the connection between all these people, me, the text, and all the languages, and what is said, is close to many things that’s happening in Ubu. I don’t know in English...

Yeah, I might ask you to send me…

It’s “the king” or something. But Ubu is a dictator. It’s a theater play. But you never know if it’s funny or sad, dramatical or ridiculous. Most of it is ridiculous. But at the same time, it’s poetic. What he says is so crazy that it’s poetic. But it’s very violent also.

That’s really interesting, and it makes me wonder if you think about politics in relation to your work, and in general the relationship between art and politics? Do you think about that actively? Do you have strong opinions on it, on ways that it should or shouldn’t be approached? Or is it not something that’s central to the way that you work, or questions that you’re trying to answer?

Oh, I think about it quite a lot, actually. I try to avoid any kind of translation of anything, I would think, in politics.

What do you mean by translation?

Like, Totality is a good example for me. I don’t know what it means. I don’t know. What is—is there a political message? Which I am not sure of? I don’t know which one is the—I don’t know. And I like that. I don’t like when music is a vehicle for a message. I don’t like that.

Do you think, though, that it always is bearing a message, even if it isn’t claiming to on the surface? Do you think it’s possible to have music without meaning or message?

With a meaning or without meaning?

Without.

Without?

Yeah, do you think that’s possible?

I didn’t say there was no message. I’d say that I don’t know it. I’m sure there’s a message, many messages. To be honest, some of the people are talking in their own language [on Totality] and I don’t know what they said. I don’t know if they really translated my sentence, or if they said strange things. And I like that. One of the people speaks Arabic at the beginning, like half an hour after the beginning. This guy, I don’t know what he said.

And you like that?

Yeah. But soon I will ask a friend who speaks Arabic what he said.

But you still don’t know right now.

Yeah, I didn’t want to know.

I see… that’s very interesting.

Yeah. But I also think we’re thinking about messages because there’s language and sentences and some words. But when music has no words, no language, I’m sure there are a lot of messages in the music. But it’s not the composer or the musician who knows about it—[they’re] not the best interpreter. It’s a connection between the listener and the musician. We need both. So it’s a collective work to raise this message or this other message. I’m sorry for my English.

No, no, I think I’m following you.

You know, very often, when you see contemporary music or classical music, classical modern music, like Lachenmann for example. When you go to a concert and you see Lachenmann, you have Lachenmann, you have the interpreter, and you have the audience. I think none of them [individually] knows what the message is. But all of them? Yes. We have to take everybody into account. And perhaps we can define little by little something that would be a message or could have meaning. But it’s never closed. I think that about art, but especially about music.

Yeah, that makes sense. I guess because there are these layers, as you say—it’s the piece itself, the interpretation, and then the space in which it’s performed and who’s listening to it—you’re saying none of those should be taken in isolation. They’re always interconnected.

Yeah. And when the composer is delivering a message, which happens a lot of times, I don’t believe in it. Sometimes I think the opposite.

What’s the opposite?

Like if he says, I don’t know… a very good example for me is songs. When you have in France, it’s a national speciality. Anarchic songs...

What does that mean?

Like, songs with anarchic messages.

Oh, I see. Okay.

But the music is not anarchic at all. And this is very funny to me. I think the anarchic music is more anarchic than the anarchic song. And this is actually… there are just many, many examples.

I see.

But I think if I said, “Okay, Totality, the meaning of Totality is this or that, or blah blah blah,” it would be the same. You would say, “You say that, but look, your music says the opposite.” I’m sure that would be true—truer than me. So I prefer having discussions about the piece, like what you said about Stockhausen. I thought about it, but not clearly. So thanks to you, I see, yes, there’s this irony that perhaps I raised in the piece, but not consciously. Usually I’m not ironical in music, but this one, I don’t know why, it came out like this.

Yeah, I see that. So would you then disagree with this idea that music is some kind of expression of the person who’s making it, that it’s an embodiment of the person? You might disagree with that, right? Because it’s very commonly accepted that this song or this piece is an expression of the person who made it, how they were feeling at the time, the things they were experiencing, the situation they were in… what do you think of that?

I think it’s bad. It’s bullshit (laughter). I don’t like this constant reference about myself. Me, myself, I. Because first of all, I think we don’t know who we are. When people say, “I do what I want”—what do you want? And who is you, that is supposed to want? And what is want? No, I don’t believe in it. But I believe in some kind of freedom that is not my own, a freedom that everybody is inventing when they are doing something. When I did Totality, I invented a little part, a little piece, a degree of freedom that I didn’t have before. And then when it’s finished, you are like… a cow in a field (laughter). You have to do another one. But it expresses a lot of things, I’m sure, about many things, but not me. I really think that when I play sax, or when I compose, myself is not there. Perhaps, at the end, a little bit of it, at the end of the process, but not at the beginning. There’s a lot of expression, but there’s no expression of one ego.

That makes sense. And I’ve read in an article that you wrote a few years ago—I’m gonna quote you—you said your work often stems from a “strong meeting with an outside element, like an instrument, theoretical idea or a collaborator.” So this, I guess, would be the real starting point for all of your work. Is that correct?

Yeah.

And you were saying that you originally thought Totality would only use your own voice, but you couldn’t make it work without this outside stimulus and collaboration. Do you want to elaborate more on that?

For sure, yeah. Totality is a good example of that. This text [you referenced], I wrote it a long time ago. I kept it because it’s always true for me. So when people ask me for text about what I do, I always send this text. I’d change a little bit of things sometimes, but not a lot. I still agree with this completely.

That’s really interesting, and makes me wonder—you’ve worked in so many different mediums, but also within music, I know you have different groups, like with Will Guthrie, which we can talk about later, electroacoustic work, solo sax, improvisation, all these kinds of things. I found it interesting that you said you wrote that statement about your process many years ago, but you still think it’s true. Do you think there’s been a common thread through all of your work across mediums? And across, say, the past few decades? Or have your interests shifted at all during that time? Has it been one steady process of trying out different things, ultimately with a similar approach in mind, or have you had different phases?

One common line in all this would be this [aforementioned] text, for example. What is in this text is something I really… not really believe in, but experiment with when I work. There’s another good example of that. Meeting an “outsider” can be very simple. It can be when a musician or orchestra is asking me to compose a piece. So the orchestra can tell me, “Okay, do what you want?” I know it’s not true. So I say, “What do you want?” And they say, “We don’t want anything!” Okay. So do what you want? But I know it’s not true. For example, you don’t have as much money as you want. Or you don’t have as many times for rehearsal as you want, etc. So, first: Tell me what the conditions are. Very often, people say, “Ah, you mean the constraints?” And I say, “No, the conditions.” Because for me, they are not constraints. It’s not negative. It’s positive. If they tell me, “Okay, we have three days of rehearsal. Ten players don’t know how to read music. Five others never show up to rehearsal. Fifteen others read music and they are very serious. And the concert will be in a spheric room.” For me, this is very interesting. Very interesting. So I like to invent a form with all these conditions. I don’t like to come up with something out of nowhere.

That makes a lot of sense, and it gets to something else I wanted to ask you. I was going through your website. I don’t speak French, obviously, otherwise, we’d probably be speaking in French (laughter). But I tried to Google Translate some of the writings on your website, and I noticed one where you talked about [Morton] Feldman, in the context of abstraction. And you just talked about how you see these real world conditions as very concrete. Like, as you said, three people will be there, three people… it’s very concrete. But it seems like you also see your work as creating these abstract systems that are somewhat self-contained, if that’s correct. I’m wondering how you see the relationship between abstraction and concreteness in your work?

It’s a big question actually. I don’t know how to… I like to think about it through visual art. I’ll just tell a story as an answer.

Yes. That’s great.

For example, we always say that music is abstract—more abstract than some other art. But we never consider that the trumpet player is playing a tool. That is very concrete. And making sounds that are very concrete, and making form with this tool. So I think it’s the listener that is constructing the abstraction, not the player. The player is like the guy who’s hammering nails. Then hammering nails will be abstract also. That’s one side. And the other side is, we always say that reality came in music when, in the 19th century, we began to do poetic symphonies, program music, blah blah blah blah. Okay. I don’t believe in it at all, because if you don’t know the cause, you don’t recognize anything. You don’t know if it’s a storm, or sunshine, or countryside. It’s very aesthetic. And then comes the recordings.

I was gonna ask you about that.

The recordings, and then you say, “Ah, here is the reality in music.” But I think it’s not true. Because, for me, the real question would be, why—and it’s a question I’ve never asked to a musicologist, but—why does nobody in the world have music that imitates nature?

Hmm.

With paintings, when you draw a body, you try to make your drawing look like the body more or less everywhere, even if it’s different from Africa to Asia or anywhere. Each time, you want to recognize something like a face or nose. But in music, it doesn’t exist.

You don’t think it exists?

No. There’s no example. We have small, small, small examples. Like, you can notice that there’s the influence of frogs on percussion...

Or bird song…

But it’s very weak. It’s like, when you think about the landscape in China, in Beijing, or in Europe, it’s huge. And the thinking of it is very powerful.

And is that because it becomes abstracted into the same material? Is that what you’re saying? That ultimately, it’s just a note that’s being played?

I have no idea actually. I have no idea why. Why an orchestra never comes in front of an audience and really imitates, like, the sound of a car. But perhaps it wouldn’t be interesting. I don’t know. But we don’t do it. We don’t want to do it. But as soon as we have paper and pencil, we want to draw a town or a house.

That’s true.

So the relation between abstraction and the concrete is very complex. If you think about all this—the event of the recording in music is not at all the equivalent of photography in painting. Because painting and photography struggled. But recording and music didn’t struggle with anything, because they don’t do the same thing. The recording was used to record music (laughter). In photography, you can photograph paintings, of course. But that’s not the main thing.

Since you brought up recordings and imitating nature… well, this is very silly, but what would you say if someone performed and [just played] a field recording of a place or a mountain or a stream? Is that still not a reflection of that place, in your opinion?

Oh, yeah, it is. It is. But for me, it’s very different. It’s nearly opposite to the question I ask. It’s like a filmmaker who would do a very long sequence of a landscape. Like [Alexander] Sokurov or [Jean-Marie] Straub.

Yeah, I was gonna raise [Straub-Huillet].

It very often goes with sound—that’s the same idea. But it’s not the idea of including in your mind, like the painter: What do I have in front of me? And how can I put it on my paper? So what do I hear? And how can I play it? That’s different from placing microphones, which is very interesting. But it’s nearly the opposite for me. Because the microphones are machines. What I like about machines is that they are bodies, robots. Very simple robots. Microphones are robots. A painter has a brush. A brush is not a robot. He can do it with his fingers if he wants. Actually I said I don’t have any idea, but I have a small idea. My idea is that perhaps a long, long time ago, people were imitating landscapes with sounds. But perhaps when language came, it separated music from representation, because language was more efficient. And it’s also sound. Writing came a long time later. So the problem between writing and representation was not so violent. But I like to think that there was a deep crisis when language came, and music changed. Perhaps before, for example, a guy was coming back from somewhere, and wanted to describe the landscape that he saw yesterday. Perhaps he played music to imitate the sounds of this landscape, because he couldn’t say, because he didn’t have language. But when language came, it wasn’t useful to do that anymore. So then music appears.

That’s—I love that.

But I don’t know… (laughter).

So for you, then, the really important aspect is not directly capturing whatever it is… as you said, the microphone is just a robot. It’ll do what it’s told, always the same way. But what’s important is the mediation through the person, and their attempt to reconstruct and synthesize whatever they’re seeing or experiencing. Is that correct? Or would you disagree with that?

No, no, it’s correct. I like the opposition between the robot and the brain. But there’s no hierarchy for me. For me, microphones are very interesting. I love to work with microphones. But when I work with microphones, I like to think about them like working with somebody. Nearly like an extra head that I put somewhere, and they are listening for me, and memorizing for me. I did it a lot in Totality. I like to record and not listen. There are several long recordings, field recordings—most of them I didn’t listen to before. There are old ones, like several years old, I’ve never listened to them. And one of my favorites is in the middle. Actually, I was working for a theater piece. I was recording, and I forgot to turn down the recorder. Everybody went out to eat and drink, blah blah blah… so the space was completely empty. And the recording was on. So I have two hours of an empty room. I checked, and I used nearly three quarters of an hour [of this recording in Totality]. I really liked this recording. You can hear many things. You can hear the technicians who are coming back, and they don’t notice that there’s microphones. And they say, “Ah… pfff… we have to work…” (laughter).

So you like the fact that that was unplanned and a mistake, in a certain way.

And also, it worked without me. So what’s subjective in the recording is where I put the microphones—but then it’s a mistake, because I forgot to shut down the recording. So it’s not really subjective. So what is subjective is when, a few months ago, I chose this recording. It’s like I was recording it again—my “microphone,” my ear, said, “This landscape is interesting.” But it’s not outside, it’s in the computer.

Totally. This is related, and I think you explicitly said this earlier… I don’t know who wrote your bio for the Cafe OTO website. But I noticed it said—I’m going to quote again—it says you approach instruments as “imperfect vehicles of artificial intelligence.” And I think before you were talking about the robot aspect. Do you want to explain more what you mean by artificial intelligence here and how that plays into your work?

Yeah. It took me a long time to accept that because I came to music from visual art. And for me, instruments… I couldn’t take it seriously, in a way.

What do you mean by that?

I preferred to work in a studio and make electroacoustic music. For me, that was more “serious.” And, in fact, also connected to what I was interested in, in visual arts. So I could make easy connections between, I don’t know… Giuseppe Penone, the Italian sculptor, and some process in electroacoustic music, and Joseph Beuys. It was easy for me to make… how do you say… to go and come back. Music to visual art and back. The instrument was like an enigma. But I was playing sax for pleasure. Little by little I played more and more and did concerts. But it took me a long time to understand my relation with the instrument. And one of the keys is that it’s not only a tool. Actually it is a tool. But what is a tool? It became very, very interesting for me, when I went into, what is a tool? What is a hammer? How did we invent the hammer? And how do we invent the saxophone or organ? Then there are all these layers of intelligence, past intelligence, human work that’s gathered in one object. And you are the interpreter. Once again, there is a question of interpretation. Actually the musician, the instrumentalist, is interpreting his instrument. You know, he’s on the top, with his contemporaries, on top of a huge mountain. In the mountain there’s everybody that plays this instrument, and making little modifications, and all the workers also, the manual workers who made this instrument. All this is gathering in the music you do. And then—AH!—the instrument became very interesting for me (laughter).

I’m now more interested after you said that.

I even like to listen to saxophone player I don’t like. It is interesting. I like to understand why I don’t like it. And where is he in the mountain? Perhaps he’s not on the same mountain.

That’s fascinating to me, and it makes me wonder about a couple things. One is, do you ever think of this question of materialism in your work? I know you brought up Straub, for instance, who sees his film as materialist, engaging with history in this way. And you talked about this mountain of history, let’s say, human thinking and work, down to the actual physical crafting of the instrument. That to me feels like a direct engagement with the history behind that instrument, and all of the contexts that it’s been situated in, and your comment about, “Oh, yeah, I’ll listen to a recording of someone playing the sax even if I hate it”—that to me feels like you’re trying to get at the quality of the sound itself and the context, and what exactly is creating that sensation. I’m wondering if you have ever thought about this question of materialism, in music or sound.

Yes, a lot. But like abstract and concrete, we could talk about this for a long time. Because what is funny is that in this concept of the instrument, like this mountain… it’s the first time I’ve said mountain, but I think it’s good.

I think it’s fantastic.

So the mountain is a way of “charging.” On one side, it’s a purely materialistic history of the object. But on the other side, when I play the instrument or when I touch it, it’s charged. It’s nearly an animistic relation to the object. But then when I read stuff about animism, it’s close to certain kinds of materialism, I think. I like this border a lot. I also like… you know, for example, in Marxism… actually you have to go back to Hegel. So in Hegel the result is the negation of the process, okay? I don’t agree with this at all. But anyway, this logic has a lot of influence. Then Marxism says the same, but with work. So, the work of people is disappearing in the object. The workers that did the saxophone, their work is disappearing into the saxophone. That’s the equivalent of this theory. But I like to put upon them another guy named [Gilbert] Simondon. I don’t know if you know him.

No, I don’t think so.

This guy thought all his life about technique. He was a philosopher about techniques. I’m very influenced by him. So he says that the tiniest object around us like this [holds up yellow sticky note with drawings on it] is a concretion of a huge amount of knowledge. A huge amount of time. People spent time to invent this glue, the ink of the yellow, the square. And all is gathering in the tiniest things that are around us. And I like to think about Simondon with Hegel and Marx: No, actually it doesn’t disappear so purely, it’s charged. It’s here. But it doesn’t mean that there’s a spirit. It means that it’s there. It couldn’t exist without that. That’s the process I am in. So that’s how I see materialism… I like to see animals when they find something like this sticky note. They know that it’s not normal (laughter). They know that there’s something strange… it’s not like a piece of wood…

A twig…

Yeah. I like to notice that. And so that’s one side of materialism I like. The other side would be connected to abstract and concrete. Because I wonder why nobody noticed that no orchestra is playing a landscape. That would be materialist. Materialist notation, or materialistic remark. Historical remark. And then many other things probably… but that’s the main thing, I think.

That’s very interesting, and I agree with a lot of what you said. It’s making me wonder… you’ve made lots of references to other mediums. And I know you’ve worked in drawing and you had an interest in film as well. I know you answered this question in another interview, but I noticed that in the first question in this interview, you said that you first hated music, and that you loved to paint and draw. And separately, in another thing on your website, I saw that you originally wanted to be a painter and experimental filmmaker. What do you think of that now? Do you see yourself as those things? Do you have an interest in working in those mediums? How do they relate to music? Do you prefer one medium over another? I’m just curious, as someone working in multiple mediums.

No, now I mainly work with sounds. And I draw. Perhaps I’ll come back to film, but I don’t make film anymore. I don’t know why exactly, but perhaps I don’t have the time or… no, sounds took up a lot of space, and a lot of time in my life. And also I like this relation with instruments. It took a lot of space also. I like to… people call it practice. I don’t really practice. I like to just do music with my instrument. With no purpose. I play every day. I don’t know why (laughter).

I see. So what do you think of technique, then? There is this popular idea that some people do their best work when they don’t have full technical… let’s say with music, knowledge of music theory, like compositional techniques, and just approach it naively. Do you believe that or not?

No.

I agree. Why, though?

What I think is that there’s no rule. For some people, it’s better when they don’t know, because they become stupid when they know. For some others, they are stupid when they don’t know and they become better when they know (laughter). And everybody has many examples around them. So I don’t know where I am. What I know is that I tried to do my process. I don’t think it’s something that I can generalize, but I like to know about what I do. I like that my practice has me go out of what I know. I choose to put my knowledge in a very bad situation. Not comfortable. Sometimes I feel comfortable with what I do, but actually my knowledge, somewhere, is not comfortable with what I do. It doesn’t understand. And for me, it’s a good sign. It means that something is happening, something interesting. So the process is connected to this “in and out.” But you don’t generalize, to stay polite. I’m sure there’s something like this everywhere. Dialectics between knowledge and practice. Which is not really theory and practice, because for me, theory is a practice. But knowledge is not really a practice. Knowledge is like... I have to know about this composer, I have to know about acoustics, about the computer… then theory is more like the practice of all this knowledge in an abstract way. To invent concepts, for example, like Deleuze.

I think we all invent many concepts when we think about what we do. Even if we don’t say it, even if we are not good at saying it. For example, I like to read what painters wrote because very often they are not into theory. They are really into practice, but there’s so much intensity in their practice that the theory comes out by itself. It’s very powerful. I like that. For example, what de Kooning wrote is incredible. It’s not theory. It’s not supposed to be theory. But it is.

Do you want to share any texts or thoughts on texts of his off the top of your head? No worries if you can’t, but I’m curious to hear more about de Kooning.

Actually, I have a book with everything he wrote. He didn’t write so much, it’s like 200 pages. There’s one—it’s difficult to explain in English—but he was ill, he had a liver illness, he saw the picture of his liver in the hospital, and he saw the color of it. And then he went back to his workshop, which was by the sea. And everything was gray in the landscape. He said all this gray is looking like my liver (laughter). So it’s like… inside outside. And then it comes back to his painting. And he looked for this color. All this process goes into one color. It’s very interesting. It’s like the charge. It’s like the mountain. The gray is on top of a huge mountain, with the liver, the landscape, what is gray, what is health, atmosphere, weather, also organs. What is liver? This text is fantastic.

I will need to look it up, I’m fascinated. So in that sense—maybe this is too big a question—but you were talking about theory and practice, the distinction between knowledge and theory, and I’m wondering if you think that theory is an actual reflection of objective reality, or whether it’s just a convenient framework with no necessary relation to [objective reality]. Do you think that it’s just a tool, or is it an actual reflection of objective processes that are happening independently of us?

Theory?

Yeah.

For me, the main thing in theory is none of them. It’s inventing what is possible. But to do that, you can analyze, of course, reality, or blah blah blah, but you don’t have to. I think, for example, there’s a lot of theory in poetic practice. In a lot of poetic practice, there’s no difference between analysis and synthesis. No, it’s all at the same time. But it’s still theory for me, it’s still connected to theory, and sometimes it’s stronger than proper theory. So yeah, for me, what is interesting in theory is to make something possible. The two things you said are also true in theory. It’s a relation with reality, and a tool, of course. But it’s not the main thing. But for me, theory is very important. It’s a practice that I have every day. Perhaps it’s an illness (laughter). In university, I studied philosophy. Since I am a musician, it’s like if I was still in university. I read, and I try to think about the history of philosophy. What is the path of the concepts? And also connecting to art… it’s very disappointing for me.

Care to elaborate?

Yeah, for example, what philosophers say about music.

Not interesting to you?

Not really. I don’t know. I don’t need it. And also, their reference is always very strange for me. It’s either music from the past, and in the past… they are never talking about the music they are listening to at the time. So they don’t listen to music (laughter). Or it’s about popular music as a social phenomenon. So I don’t know. Of course there are a lot of small exceptions, like Schopenhauer. But it’s always small. So I don’t read philosophy or theory to learn about music. I learn about music when I listen to music or play it.

Yeah, definitely. And… I don’t want this to be a lofty claim. But do you think that you’re trying to fill that gap, that kind of philosophical gap through your work?

No. I don’t spend enough time. I have many ideas. Perhaps to do it, I should work with a proper philosopher. Perhaps we could build something. But I don’t, my background is not strong enough in philosophy to do serious work. But what I can do, and I would like to do it sometime, is to give ideas, to give directions. But it wouldn’t be a finished… yeah. Technically, philosophy takes a long time, it takes a lifetime. I still like it a lot, but I know that, for example, I take very long to read. I like to read very carefully. When I read Kant or Hegel or Marx, it takes me a long time. I can’t read it in like two or three weeks. But I like it. To be really… you have to have this strong background, you have to read everything. You know? Which is not my case. I read a lot, but not enough (laughter).

I think that’s how a lot of us feel. I’m trying to think… we’re at about an hour and ten minutes. I do have a few other things I wanted to ask you. But did you want to talk about this Will Guthrie collaboration album [Electric Rag] you have coming up?

I can say a few things, but perhaps it’s better if you listen to it. What I can say is that with Will, the work we do together is very connected to what I said about this mountain. We take the path of common culture, which is connected to Black music from America, the history of jazz. In the musical network in Europe, for example, many people don’t like jazz in this area, like experimental music and contemporary music. And Will and I, we take this interest in jazz and put it in the music we do. So the reference, the origin of the music we do is this common culture. Which is not always the case when you play with musicians. We are conscious of this common path we have with a lot of things, and we like to talk about it and listen to music together. We send each other links (laughter). And so the music is coming from that. What is impressive for me is that it works. You don’t know really where it’s coming from, especially when I play electric organ. Because to be honest, electric organ is my first instrument. But before I played with Will, I never played in any kind of jazz group with the organ. I don’t know what to do. But I know that I have to do it (laughter). It’s strongly connected to this common culture. That’s what I think is interesting to say. I won’t explain the music, out of nowhere [before you listen to it].

Definitely. I’ll keep that in mind.

The other thing is that Will and I are interested in electroacoustic music. So there is a little connection between this huge mountain of Black music and perhaps a small mountain of amplified music. We like to take into account all the processes from the instrument, from the object to the speaker. Everything has something to do with the music. It’s not hi-fi. But it’s not lo-fi. It’s just no-fi (laughter). Because we don’t have to be “fi” to anything. It’s the other thing that we agree on. It’s like this common culture going through a technical process. Connected to amplification. Connected to speakers. The organ I use—I use several kinds of organ, and they are all fucked up and old (laughter). I use a lot of the defaults, when they’re out of tune. I really like to make up some scales. I know these organs are making these scales. So it’s scaling, like in jazz, but in this strange way, using the default of the instrument. Stuff like this.

You bringing up jazz is very interesting, and I wanted to ask you about that in general. Just as an aside, I thought it was very interesting that you commented that a lot of people in the kind of experimental music world in Europe aren’t interested in jazz, because on the one hand, I thought that there was a time when a lot of jazz groups couldn’t find any success in the US, and their only audience was in Europe. So I had this sense that there was more of an audience for it there. So it was interesting to hear that. But in general, I wanted to ask you—I read in interviews, for instance, that big inspirations and moments for you were when you listened to Cecil Taylor, [John] Coltrane, Arthur Blythe, all these people. Is that something you still think actively about, even in electroacoustic work, or in other mediums? What influence does that play today?

What is the last sentence?

What influence does this interest in jazz play on your work today?

What is difficult is making a relation between, like, Cecil Taylor, Coltrane and electroacoustic music. But I think I do. I do a connection, but it’s very complicated to explain. But there are some directions that I like to think about, like the physicality of the sound. Also, the idea that you never make the same sound twice. I like the connection between improvised music and free jazz, which is part of it, and the fact that this phrase… we did [this phrase] once this day, and we never did it again. It was recorded, so because I was not at the concert, I can listen to it… in the studio, you can do the same. Totality is full of stuff I’ll never be able to do again. It’s nearly only that, actually. This singularity of things for me comes strongly from visual art, some part of it, but mainly from jazz. And also the singularity of their sound. If you think about Arthur Blythe, the fact that I recognize him in a quarter of a second or even less is really strange. Strange. Because there are so many alto players in the world. But him I recognize—and many others, but you talked about him—all of us saxophone players, how are we able to recognize the players? It’s incredible. Each of us can recognize fifty players in a few seconds. This is incredible. For me this comes from jazz. I know people in classical music say, “Oh, it’s the same for us.” But I don’t believe it (laughter). I think they are right… but it’s not the same level. For me, Arthur Blythe invented his own instrument. You know the mountain? On the mountain, there’s a small mountain, it goes very high, and it’s Arthur Blythe (laughter). So I like to think about it like this. And I like to think about that when I record with microphones. I like microphones to be the witness of singularity, like they are when they record a concert. The point is the connection between concert or performance, and recording sessions in front of microphones. I look for something that I will never be able to do again.

That’s very interesting. I—wow, I want to ask a bunch of different questions based on that. But first: you mentioned that someone like Arthur Blythe has invented his own instrument, as you said, or he has his own little part on the mountain (laughter). And part of that is the ability to recognize his sound immediately. I’m wondering if you think that it’s important for artists or musicians to search for “new” things, things that are like that, that are identifiable as such, or whether that’s just a non-issue. This question of newness—I’m curious what you think of it.

Oh, I don’t think about it. I think we shouldn’t. Even if like everybody, I happened to need to say, “Oh, I’ve heard it millions of times. It’s boring.” It’s not a good thing to say. I think when I say that, it’s not what I think. What I should say is: “This guy is playing badly.” (laughter). Because what is important for me is to be convinced by what you do. In a social environment, the problem is that there is a huge amount of musicians who are playing music that they don’t want to play. They get bored playing it. They don’t even know that they’re getting boring. So yeah, I think the question we have to ask ourselves is: Is this really what I want to do? Am I really into what I do? Completely? That’s why interpretation is very complicated work. It’s very hard to be a good interpreter. I am not. I can’t do that. Because I always think that I am wrong or that there’s part of myself which is not into what I do. It’s very difficult. And I think that newness in art comes from this process. When you are bored because you’ve played one thing so many times, then you have to invent something else. To get involved. Otherwise, you commit suicide (laughter). Or you just give up and do something else. Actually that’s what we see all the time, people who give up on music, give up on whatever, they don’t see why they should continue. They don’t see the point. I think it’s right to do that, it’s right to stop. Better to stop than to continue.

That’s true. That makes me wonder what you think of the words “experimentation” and “experimental.” I know some people working as “experimental musicians” don’t like that word. But what do you think experimental means? Do you relate to it? Do you dislike that word? What is an experiment to you? What does that actually mean?

I prefer “experimental music” over “contemporary music.” I like “experimental” in its connection to performance, for example. And also the connection to trial. There’s another thing I was gonna say about jazz—about the group [context].

I was gonna ask about that next.

Which is very important for me. And I also like to compose with people. I compose with Eric La Casa, for example. I don’t know why, but not many people are composing not alone. Or writing not alone. And my interest in collaboration comes from jazz. Definitely, like all these groups, all these relations. For example, the relation between Cecil Taylor and Jimmy Lyons is incredible for me. There are many examples. And you can feel that the music wouldn’t be the same if they didn’t meet. Like Coltrane with Elvin Jones, or stuff like this. I like to think about my work like this. So that’s why I didn’t want to agree with this “expression of myself.” In my music even when I play a sax solo, there’s all my collaborations in the music. For example, for a long time I played with a guy named Eric Cordier, who plays hurdy-gurdy. So I played the “sax hurdy-gurdy.” And I think hurdy-gurdy is a huge influence on the sax. I think now, even though we haven’t played with each other for like twenty years, in the solo saxophone work I do today, there will be a part coming from the hurdy-gurdy even if I don’t know it. Like the way I use circular breathing. The way I use the saturation, the natural overdrive with the sax—part of it is coming from how you can do it with the hurdy-gurdy wheel, by pushing the wheel. So I work on finding some similar effects.

I wouldn’t have guessed that, but I hear it now. That makes a lot of sense.

It brings me to something like pipes. Bagpipes. But actually, the influence is not bagpipe but rather hurdy-gurdy. But hurdy-gurdy is a kind of bagpipe. So it’s funny.

Absolutely. You brought up exactly what I wanted to ask you next, which is just coming off of the jazz discussion, and the idea of singularity. I was gonna say exactly—as you said—that that singularity emerges only from that group interaction. And that is different every hour even—it’s never going to be the same, even between the same group of people playing the same instruments. I was wondering—you said for instance, with Will Guthrie, you work together really well because you have shared agreements. But is that always what you look for in a collaborator? Or do you look for disagreements too, or clashes?

Also we disagree. On a lot of things, with Will. No, what I really wanted to say is that what brings us to our music is our common culture. But when I play with Seijiro Murayama, I think it’s quite different. I think our common culture is what we do together. When we began to play, we didn’t really know what or why we wanted to play together. And it changed little by little to what we do now. Of course, there are a lot of connections with many, many other music, but it’s mainly connected to our own history. And then disagreements and agreements are part of the music. When we do a concert, there’s a lot of drama (laughter). There’s a lot of… it’s like the music is a stage for the space of the relation. The music is not really a discussion, because there’s no argument. But it looks like a discussion. Between fights, love… (laughter).

You bringing up performance and space is very interesting. I know you’ve been asked this before, I’m sure, but because of your extreme focus—or not extreme, but significant, focus—on physical surroundings and space and performance, and what you’ve said—I’m quoting you—that [when I improvise,] “space is not a parameter, but a partner,” I’m curious if you want to elaborate on that. What is your interest in space, and performance in that space? And why are you interested in those questions?

Because especially the sax and organ, the instruments I play, are strongly connected to space. Space is a strong way to adapt to the solo what I think about the group. Everything I said about the group, I can say also to the solo. And space is part of the logic, part of this “outside.” But it’s not the only part. The audience also… many, many things. But the space is the first entrance. And even very physically, with the sax I like to go to very fragile registers, or very fragile vibrations. These things are so fragile that they become dependent on the space. So this sound... I can do it here, but I can’t do it there. It’s a physical reality. But I know that I can guess in this space, I can work on that… There’s a really simple example. Sometimes I like to do a very short and strong note in the low register. Like [makes a poof sound], very loud. And then very quickly I do a very tiny, medium or high pitch, that’s like the resonance of the low note. So this, of course, doesn’t work when the space is dry. It’s even ugly. And you can say, “Ah, this space is very wet.” So then I will do that. But no, it doesn’t work the same on all reverberations. So you have to work on the interval. Not all intervals work everywhere. It’s very tricky. And to be honest, I’ve fucked up some concerts because of that, because I’m too sure of myself. Like I said, I play in the church, so there’s reverb, I will do that [technique] at one point in the solo. Because I didn’t try it before, when I do the concert, it doesn’t work. It doesn’t work at all. So if I am clever, I manage with it, but I can be stupid sometimes. And then it’s fucked up (laughter).

Yeah, it happens (laughter). You bringing up the church organ… it seems like that’s a very big part of your work right now, including visiting different locations to test out organs. What drew you to that? And what interests you about that whole process? I’m sure it’s related to this question of space, because these organs are rooted in place, right? You can’t move them. So if you could talk more about that, I’d love to hear.

My first instrument was a keyboard. Electric keyboard, electric organs. And then the church organs came later. The connection for me is very clear. The connection is with visual art and electroacoustic music. The church organ is like a huge permanent installation. And so you have the huge space. You are the interpreter of the guy who made the church space. And the guy who made the organ—and I said the guy, but usually there are millions of people. All the people who worked on all this. So I am the last one coming in today. And I try to interpret something about all this. And so I love that—it’s very close to doing installation. The other connection is: When you play church organ, it’s like being in the studio. It’s like an archetype of the studio. Or archaeology. You go in the past, what was the electroacoustic studio of the 18th century. That’s what it was. This for me is very touching. So for me, it’s a way of doing music without thinking about music. I really like to have access to the organ like a sound artist.

That’s really interesting, especially the archaeology aspect. And I’m wondering, beyond being this kind of prototype of a studio, do you think of the social and cultural context of the church and the space when you’re working? Or is it purely about the instrument itself and the physical space and the resonances?

You mean the religious aspect?

Yeah.

In a way, it’s a simple question, because I have no connection with any kind of religious belief. But then, on the other hand, I am very interested in theology. But all the books I read about theology, they’re not really connected to what I do with the organ. Sometimes, sometimes not. And also, more and more churches are becoming spaces in town, that sometimes it’s a church, sometimes it’s not… I like this changing. I like the fact that they can still be used as a religious space, and the next day for a noise concert. I think it’s important. I always like to go into churches. When I go into town, if I pass in front of the church, I like to go inside to see it. In all the countries I went to, I did that. So yeah, I’m curious about it. But I have no message about it.

For sure. I mainly asked because I wanted to transition to talking about Home: Handover, if you’re willing. And I view that almost as a documentary, in terms of—it is reflecting a particular culture in a particular social space and refracting it, almost. So that made me wonder how often you think about that aspect. I know, as you mentioned, when philosophers talk about music, it’s often popular music and the social and cultural roles. And I wonder if you do think about that, especially through a work like Home: Handover. Plus, I know you mentioned you’re working on something in a similar vein. I’m just curious to hear more about what inspires that kind of work.

I think we tried to do a lot of things in this work. We tried to do live radio, experimental radio. But we have a documentary side of it. Then it’s also a way to question what I was saying about conflict and representation. I think with Home: Handover, we tried to make a concept that would have some information, that would be a documentary. You can have a film that is a documentary, you learn things with the film, and you can do a concert that is also a documentary. With Eric [La Casa], we did a lot of radio. It’s something we talk about a lot. And information can be language, but also sounds. And also the music was like some kind of inquiry about music, about how you listen to music at home. Which is also an interesting question for us. We were curious about it. And what is very instructive, but also sad in a way, is that many people today, everybody, has a lot of tools to listen to music. Many of them are the old hi-fi player, a good one, that’s somewhere in the space. And when we ask, “Can we listen to something?” there’s panic because they don’t know how to plug it in properly. And finally, they listen to it on the computer or on the mobile phone. Not only songs but also classical music—they will listen on the phone, in the kitchen. In the living room, they have a proper player, but they don’t even know how to plug it in, or they lost the wire. Or very often they say, “Oh no, my son took it.” (laughter). But there are no exceptions. We saw twenty people, twenty-five people, perhaps more. All of them with that problem. I say that, and I have that problem.

Yeah, me too! (laughter)

It’s not properly connected. It’s always a big mess (laughter).

I’m curious, if you’re willing, how you found all the people that were involved in that project? Were they just strangers?

We didn’t find them, we asked. We don’t know them at all. That was one of the rules.

And so you’re working on a new project along similar lines. Is that correct?

With Eric?

Yeah, I know you mentioned something about that in our emails, but maybe I misremembered.

No, we are supposed to do some other thing. Actually we did something in Glasgow, we did several ones, in Paris, Marseilles, in France. And there’s some project to do with some places. But nothing very precise. Actually, the next thing of mine is this composition, which is a translation of electroacoustic into instrumental music. The one after is a complicated project with another orchestra in an archive museum. So perhaps that’s what I was referring to. But I am alone, Eric is not with me. The idea is to make a concert which would also be some kind of installation, for all evenings from six to midnight, a very long concert. The space is huge. It’s an archive on the world of work. Everything about what work is—it’s very interesting. It’s an archive of big businessmen, syndicates, trade unions, political militants, all kinds, a lot of anarchists, but also big boss, that gave the archives. It’s huge. So I picked up some part of it and tried to build something with some text, some music, because I also found some songs. But it’s not done, so I won’t tell you a lot about it. But what is good is that there’s a lot in common with Home: Handover. Because there’s some kind of document. Music and document, relation between music and document.

That makes a lot of sense. I look forward to it. I think I’m pretty much running out of things I wanted to ask you. I think we’ve had a really amazing conversation. It’s been two hours (laughter). But before I ask you for final comments—I’m sorry in advance, you probably get asked this a lot, maybe. But you mentioned… you’re working on this installation piece. And that made me think of what I saw in your bio on Cafe OTO’s site, which is that you’ve studied with Xenakis. And I was wondering if you would like to talk more about that, how that influenced your work, and what it was like to study with him.

I could talk a long time about Xenakis. What I can say is that he is one of my main influences. Many things… the relation between visual art and music. Also the physicality of sounds. Like what I said about Cecil Taylor, I could say about Xenakis. Many things. I don’t like everything he did, to be honest, but it doesn’t matter. I like the process. I like the formal process of the whole thing. I like the relation to mathematics, because mathematics is another thing I like. I am very bad at it, but I love it (laughter). I like what he did with it. But then what we could develop—we could do it another time—is really in the process itself, which is stochastic. What is statistics? The relation also with natural phenomena is very interesting, because it’s connected to what I said about the landscape.

Exactly. Yes. I just want to say, I’m interested to hear more about this if you want to go on at length about it.

Yeah, an example of someone who thought about [the problem of the landscape and representation] is Xenakis. In a way that a visual artist would think also. There aren’t many. I think he’s one of the only ones. Also, I like the idea that he did formal processes. This is complicated. He has both sides. On one side is electroacoustic music with lots of recordings which become nearly noise music. And on the other side, he did the same with instruments. But he didn’t say, “Okay, just play as loud as you can.” He could’ve said that, but he did not want to say that. He went into the structure, the structure of noise. His noise is all the noise of noises, and this is really interesting for me. That’s very often what I don’t like about noise music, that it’s just one noise. One kind of noise. But there are many kinds of noise. That’s what I like about Xenakis. Because he went into that whole structure.

Do you want to explain what you imagine different types of noise to be?

It’s connected to the structure, like the micro-level structure, and how the micro level can be something very different to the macro level. You ask the musician to do something that is actually not connected to the result, but if he doesn’t do it, the result will be different. But he doesn’t have control.

And do you think randomness plays any role in this? Or is that just irrelevant?

I think you don’t need that to understand Xenakis. No, it’s more like big numbers. Or statistic logic, which is not random. Just that there are many elements, many many elements that look like each other, that are similar. So for me, it’s very different to what is random.

That makes a lot of sense. I think I am pretty much at the end of my questions. Is there anything else you wanted to talk about or mention before we close out for today?

No, thank you very much. I was very touched by your [review of Totality]. So I’m very happy to have this discussion today.

Absolutely.

We can continue some part of it by writing each other, or by doing it again, or…

I would love that.

So thank you very much.

Thank you, too. I really enjoyed this conversation! Cool. I guess we should close out then. What’s the rest of your day looking like?

I think I will go out and have a bowl of air (laughter).

That sounds good. Maybe I should do the same (laughter).

Thank you for reading the seventy-fifth issue of Tone Glow. Let’s all get a bowl of air.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.