Tone Glow 137: Joel Grip

The first in a series of five interviews with jazz quartet [Ahmed]. Bassist Joel Grip talks about the importance of failure, learning through listening, his extramusical endeavors, and Chester Zardis.

All week, Tone Glow is hosting five different interviews in celebration of [Ahmed]’s two new albums, Giant Beauty and Wood Blues. The series will feature individual interviews with all four members and conclude with a group interview. The other interviews can be found here: Pat Thomas, Seymour Wright, Antonin Gerbal, [Ahmed].

Joel Grip

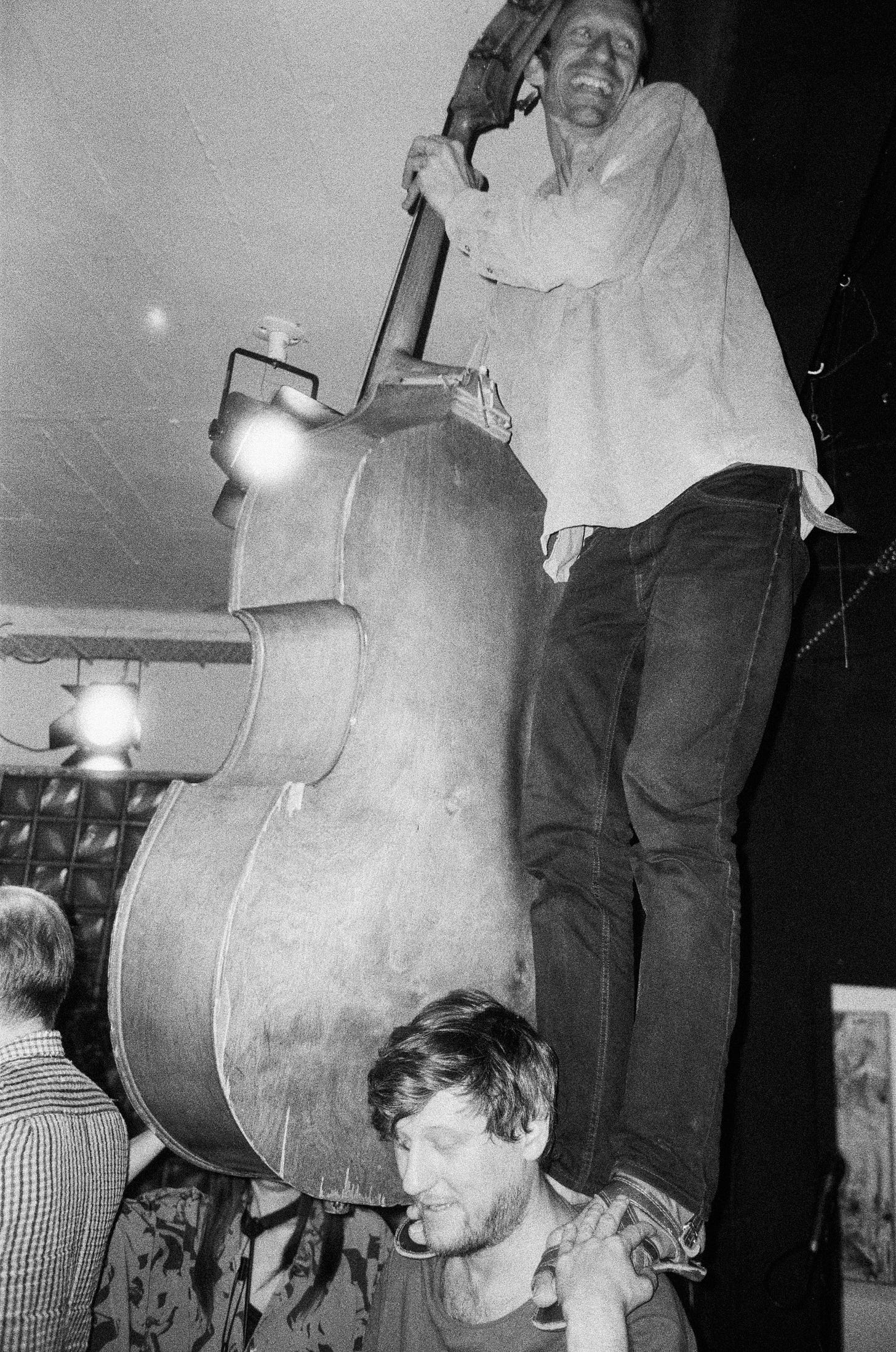

Joel Grip (b. 1982) is a Stockholm-born, Berlin-based improvising bassist who has spent the past two decades playing in a variety of groups, including [Ahmed], [ISM], Oùat, Klub Demboh, Vaka, Peeping Tom, and Corpulent. In 2004, he began Umlaut Records out of a desire to see more music get made and performed in Sweden. Ever since, his life has been fueled by a passion to create what he wants to see happen, often centered around collaboration. This has recently included Au Topsi Pohl, a jazz club in Berlin that led to him organizing 550 concerts in three years. Grip is also a visual artist, primarily working in analog filmmaking, oil painting, and graphite and charcoal-based drawing. He has appeared on around 50 releases throughout his life on labels like Fönstret, Astral Spirits, OTOroku, Corbett vs Dempsey, Topsi Series, 577 Records, Bison, and Rune Grammofon.

Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Grip on February 21st, 2024 via Zoom to discuss how [Ahmed] forces him to evolve as a bassist, the connection between music and dance, the importance of failure, New Orleans bassist Chester Zardis, his recent trip to Senegal, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: How has your day been so far?

Joel Grip: Oh, it’s been good. I have been practicing with my friend Simon Sieger, a piano player. We’re trying to make some new boogie-woogie (laughs). As our society is so fast and our concentration span can be quite short, we are working on a boogie-woogie that has new thoughts and is adapted to our screen society. So, boogie-woogie with flashes of disturbance.

Interesting. So do you feel like music is a byproduct of our own attention span in some way? And do you feel like your own music over the past decade has changed accordingly?

I have kids, so it’s quite nice to have access to different generations. I think it does have an impact on the music—the way you can listen to a little bit and then flip to the next thing, but as soon as it’s a little bit demanding—I mean, I am speaking generally, but for myself, I like when it’s demanding. Maybe that’s why I like to discover and see what is there. We think, maybe we can use this attention span in a way to connect to the past and the future? So yeah, it’s exciting but also a little bit frightening, you know? (laughs).

How old are your kids?

Eight and eleven.

I wanted to mention this clip that you have on your Vimeo page called Movement and Sound with Claire Malchrowicz.

Oh yeah, okay! Wow, you found that one (laughs).

What’s interesting to me is that you’re playing and she’s dancing. In the description, it says she’s “moving” and you’re “sounding” but that it could also be the inverse. That’s exciting to me because when someone is dancing you can hear the sounds of them moving their feet. And, of course, when you’re playing the contrabass you’re also moving in some way. I’m curious how long you’ve thought about performing your instrument in this context of movement and dance. Is that something you’ve always thought about, or is it something that came about later?

I think it’s always been there, and I remember the first time I even touched a double bass it was like dancing with someone. You know, the physicality of the instrument itself… it’s like hugging someone. I think I really loved the double bass by embracing the sound—it enters your body and vibrates in you. So this physical aspect was there right from the beginning even though I didn’t analyze it that way. I remember I got really hit by that because it’s a difficult instrument to start playing nicely. It will take ten years before you start enjoying it, like, “Okay, this can almost be a nice sound.” (laughter). It’s like the trumpet—it takes time.

It’s nice that you asked about Claire and dancing. It’s funny how someone you don’t know looks on the internet and finds things. It’s maybe also connected to the first question about how there’s so much stuff—so much dust and dirt on the internet lying around—that all of a sudden this comes up. It’s like an old wine (laughter). I remember playing a lot with Claire. When I play with a dancer, I often play with my eyes closed. You feel the presence of the body, and you can hear her, and I let her be the instrument and let myself be the person moving. This really opens up a space to meet. It’s like when you talk, you don’t only talk, you listen. I lived in Sweden, and in the US, and then in France, and now in Germany. The way you listen is very different in each country. In Sweden, you listen through being silent. And in France, you listen by talking (laughter).

As soon as I go on stage, I’ll stand still and play the bass, but there’s also a way of moving. And there’s a choice—I could move a meter away, and that might change the music a lot. With any group, but especially with [Ahmed], placement is important. I play the acoustic bass in a group which is extremely intense and has a lot of sound. How do I make my bass come out through that? I have to really dig down. I listen to a lot of bass players—like hundred-year-old recordings—and think, how did they make their sound come through? They’re maybe playing outside with a big band or an orchestra, and walking through New Orleans. In big bands, how did the bass players do it? They have to move. Where did they put the bass in the room? You work as an acoustician or a sound engineer at the same time as being a bass player. I have to think about where people can hear me best, depending on where I stand in relation to the drums and the piano and the saxophone. It’s a kind of dance, all the time.

There’s so much you just said in your answer that is so interesting to me. Are there specific recordings that you heard that helped you recognize how you should be moving or where you should be positioning yourself in a space?

There was one guy, a New Orleans bass player—there’s a documentary on him, even—Chester Zardis. He stayed there, so he didn’t become famous like Pops Foster or Wellman Braud and all the bass players who left New Orleans. He had this technique where he turned his back to the audience and put the bass towards the wall so the sound bounced out into the audience. He had to do it; it was not just a schtick. Maybe it became a funny thing, but it was useful. The necessity of the movement was there. The necessity is the main thing for moving forward and finding new things. Like, how can I possibly make myself heard in this context with [Ahmed], in this quite extreme energy, where normal practices will not do? By the force of necessity, you have to improvise. There is no other way around it. I often find myself in that situation when playing with [Ahmed] in particular. There’s no room for preparation on the spot. You cannot think, “Oh, wait a minute, if he plays that, I should play a little bit more like this.” It’s way too late. You are forced to act in the moment, and this is very exciting. It’s about taking huge risks, because you are basically failing and failing and failing and failing, and failing becomes a locomotive for moving forward.

I think Seymour talks a lot about that and the learning process. You learn. You just stand there and you learn from each other and from yourself. You think, how can I possibly move further? And then you do it. And then you’re in another spot, and you’re completely locked up, and you have to move out of that too. And when the four of us in [Ahmed] are in these positions, it creates some kind of swarming. It’s slow, very slow—and fast at the same time—moving music. This is connected, of course, to the history of jazz and all our knowledge.

So Chester Zardis was an eye-opener. He lived, I think, well into the 1980s. Like, almost a hundred years old. There are many people you can listen to, like the bass player of Thelonious Monk, just how they’re kind of stubbornly being the… walking time for the music. He’s making it swing, and making a dancefloor for the dancers. For Monk, I mean—Monk was dancing. He’s the main figure in everything I do in music. For him, I think a good way to measure if the music was the way he wanted it is… if you could dance to it, it’s good. So the movement of the body, the connection to the body, is something that I really like to work with.

I want to talk about something you mentioned earlier. You said that when you first touched a double bass, it felt like this intimacy of you dancing with a partner. When did you first start playing it? Was this the first instrument you played?

I started playing electric bass. Well, actually, I started playing drums even longer ago, when I was maybe 10. It was a little bit too much of an industrial way of learning drums. You’re sitting with four kids playing the same doot-doot-doot-doot, seeing if you could do it or not, so I stopped doing that. Then, my friends had this rock-pop-punk band and they asked me if I wanted to play the electric bass and I joined them. So I learned the electric bass for maybe three years before I picked up the double bass the first time. I had quite a good teacher because we played to James Brown and to James Jamerson, Motown stuff. Coming to the double bass was then like, “Oh, wow, okay. This is where all this music comes from.”

Was this in Stockholm? Were you born in Stockholm?

Yeah.

You said that in Sweden, people listen by being silent. And then you said for people in France, they’re always talking (laughter). I’m trying to understand the experiences you had as a child in Sweden, of gaining an appreciation for listening, and how that compared to when you were in different countries. I’m not quite sure what it means to listen by talking, like what does that look like? How does that compare to what you were doing in Sweden? How does that compare to when you were in Baltimore?

Talk about an alarming process and adapting to situations that are uncomfortable. Coming to Baltimore, I could speak English quite okay, but you still have to learn a whole new system of culture. I think the key thing is to listen. You have to learn the culture of listening to be able to tap into the timing, the timing of, “When can I actually cut through? When can I say ‘no, I don’t agree?’ When can I just throw out an idea?” Of course you don’t have to learn this, you can do it however you want in the end, but there’s always some kind of system to find, which interests me.

The way I work is I spend maybe a year just listening (laughs) to get into the timing of the language, to get into the language itself, to get the words, of where to put my tongue in my mouth. Then you start to understand how you listen and how you communicate. In Sweden, you really let people talk until they end. You even have a way of talking through silence, almost. You can say very little, compressed sentences into sounds. Like, breathing in can mean “yes” or “no.” It can mean, “Yeah, let’s go find an ice cream,” depending on the situation (laughter).

In France, you might have to go through talking about a philosophical concept before you start ordering a coffee (laughter). It can be really interesting. It’s fantastic, but you stand there and it’s like, “Wow, it’s been two hours that we’ve been talking about this, I just wanted to buy a coffee.” (laughter). Of course these two extremes can be hard to combine, and I love that. To be able to do both, I think that’s wild. I love discovering these hard moments—it’s a little bit like [Ahmed]. You understand, “Wow, how will this be possible? How will I come out of this situation?” But you have to just push further, to put yourself in some kind of check, like in chess. You have to accept that condition in order to learn.

There comes a point where I have to let go of everything and just accept, “Okay, I don’t understand anything, but there’s one little thing I understand and that’s how to hold a fork.” So I just hold on to my fork, and then you get a knife, and then you are invited to a tea ceremony in a small house on the beach in Senegal—which happened a month ago—where you don’t speak Wolof but you’re there and there’s this political discussion, and you wish you could take part in everything, but in a way you are part of everything. I mean, the worst thing would be to leave. That might be the first thought that comes to you, where you’re like, “No, it’s uncomfortable.” And then we are back to the first question about attention span. As soon as something is a little bit uncomfortable, you flip to the next thing, to the eternal screen. I really learned quite early on to enjoy this position where I’m like, “Okay, I have to let go and things will come to me and I will learn.” In that way, I learned to live and enjoy Baltimore. That was quite a big thing. That, and then there was French culture, and now the German culture which is also the opposite of French culture even though it’s very close geographically.

How so? How would you say they’re different?

(laughs). Well, without any judgment, I think it’s very much the opposite in many ways. The way you walk and talk, the way you attack a problem. In Germany, you go directly to a problem—you try to make it appear and then take it away. In France, it’s more like embracing everything that’s not the problem in an effort to take it away and see clearly. One way is not better than the other, it’s just quite different. Within all this, I was just traveling last weekend in Western Germany and also the Black Forest, which is more southwest. It’s very different. The German cuisine, for example. You can almost laugh about it, like, “What’s that?” It’s so extreme. There’s so much stuff. Each little village has their little restaurant with their own specialty, their own beer. In Sweden, all of that is long gone. It’s all turned into this kind of airport society, this kind of fusion. It’s empty. It’s an Uber society.

When were you born?

1982, so I’m 42.

What things do you miss from the Sweden you knew from growing up there?

Within 40 years, Stockholm changed from being maybe the poorest area into the richest area in all of Sweden. It changed a lot and it’s a little bit sad. You go home, but you feel extremely excluded from that whole way of living. What I like and what I always look for is more of this communal way of daily life, where you go and say hello to the baker. You say hello to the mailman because you know them, you see them a lot, and you even have coffee with them. Today, it’s extremely separated, and I think the screen has a lot to do with it. What I see when I’m there is a kind of distance between people, which Sweden is kind of famous for. People make fun of Swedes as being, “Ah, you have this distance, you don’t really want to argue,” but it wasn’t really true. Now, it’s more of a general truth, I think. It’s a little bit of a zombie feeling (laughter). You talk to people, but you don’t really have the feeling that they heard what you said, and they kind of made a syntax out of it. It’s more of this empty talking. It’s not everybody in Sweden, but where I’m from, the change has been quite extreme.

And the places where you could play, they all disappeared because they’re not profitable enough. I mean, these things happen everywhere, but this pattern is fast, violent, and quite aggressive, and it has its effects on people you meet on the street, or in the audience. In Sweden now, it’s rare to have a conversation with someone after a concert because they go home. I don’t know. That’s what I like with Berlin, because you still have some sense of that here. And also, in the countryside, I feel there’s space for living through these failures and learning through failure, and living through that together with someone.

Interesting to know you were born in 1982. That means you were only in your early 20s when you started Umlaut Records. The first records on there are great and very varied. You had the Corpulent record—you composed songs for that, like “Gryphus Medley.” You had the Jolly-Boat Pirates album, and then you had the album with Per Wålstedt. There’s poetry on that album. When I look at your work, I’m fascinated by how you’re constantly pushing yourself in these different collaborative settings but also how you’re doing different things outside of music. The newest album you have in Oùat, you had drawings for every single track. And then of course you’ve made films throughout your career.

Yes, I agree, it’s quite different. There were a lot of different kinds of things coming out when I look back.

How did you approach collaboration in your 20s, and how do you feel like you’re approaching it now in your 40s? What’s different?

I think it’s quite similar. I’m still very much in the moment when I meet someone. For example, with Gary Thomas and Devin Grey [of Corpulent], I would have never come up with that idea in Sweden. I happened to live with Devin Grey—we shared an apartment—and we played every day. It’s about seeing the possibilities, anticipating the possibilities. It’s a lot about the microseconds when you play. Collaboration [outside of the context of playing live music] is quite similar. It’s slower, but it’s also quite dangerous in the sense that you are really, on a human level, trying to do something together. Making music together, it’s gone and then you can talk about it. You can have the feeling of taking a risk, like driving a car 300 kilometers per hour into a wall—that sort of intensity. With collaboration you have to be more careful, and I think I have been quite fast and quite good at making ideas real, especially in the beginning when the only way for things to move forward was by doing them myself. It was also during a time when things changed politically in Sweden. Before, there was much more of this communal way of living, this support, and then it all disappeared at the turn of the millennium. Before, I had the feeling of, “Someone will take care of this, I will be part of a bigger thing.” But that was not the case, I had to take chances and make something out of them. I did that a lot and I’m still doing that.

Before, it was more about how we could get into a studio and record, or how to make my music on stage, how to create room for music. So all my collaborations, everything that you’ve mentioned, are connected to that. It’s connected to how to make this music available under a roof where people can meet. Like Per Wålstedt, the poet—he’s a farmer in the village where my mother lives, and he writes the poems on his tractor, harvesting potatoes. We were neighbors and we started collaborating. I say yes to things. I mean, it can come back against me, but the first thing I say is, “Yeah, let’s try it!” And sometimes it means, ah okay, it stops after half a year. Maybe it was a bad idea. But I’m still very happy with that initial feeling of, “Yeah, let’s try it.” That energy has helped me find myself in situations where, with [Ahmed] for example, I’m so happy that I can almost start laughing from the situation. “Wow! How did I end up here,” you know? And I’m so happy about not really knowing! It’s more about finding yourself in a shared moment, and it’s so healing. It’s a spiritual experience. I think my collaborations have always begun with that: “Yeah, let’s try, even though it might seem completely crazy.” And then by doing it and learning what will work or not, I have the ability to realize it in an organizational way.

I started a group, but in order to start this group, I needed to organize a festival. And to be able to start a festival I had to start an association, an organization, an NGO—there are a lot of surrounding things that come with a project or a group or an idea. So I did a lot of that and now, 20 years later, I take more care about the organizational side of things because it can really take over. The last big thing I did was Au Topsi Pohl, a jazz club in Berlin. I was not alone, but I was initiating the whole thing and it was basically in the basement where I live, so it was connected to my family, connected to my closest living space. We organized 550 concerts in three years. It was fantastic. The best thing with that was we stopped before we got angry at each other—we stopped when it was really working well. I have really good, fond memories of that, but I’m still a bit tired from the organizational responsibilities of doing all that. Even though I still have ideas that I want to realize, I don’t know when they will come. One day they will.

It’s about being able to play in the same place many times. Playing regularly at the same place for the same audience is a very, very old idea. You had your local musicians and you went to hear music. You would just walk down the street and hear it and take part in it and it was not a big deal, and you practiced and participated in that method. So this is a little bit of what I’ve been chasing and trying to find, because I project myself into my fantasies about music, and I can only reach them by playing. I cannot reach them by coming up with new concepts and writing applications and getting money and starting a festival. I tried that but it didn’t work. I can only reach my fantasies by being on stage and failing every day, every night, until something happens—and it’s probably something other than what I was looking for.

Wow, that’s beautiful. I wanted to ask, what made you decide to release a solo album in 2012 with Pickelhaube? What was the decision to eventually do that after years of not having solo records?

At the time, maybe after ten years of being involved in organizing and being a musician, it was like, “Okay, where am I? Let’s see where I’m standing, and let’s bring the focus to me.” When you also collaborate with a lot of people, it’s easy to lose yourself. It’s easy to get lost. Of course, it’s also the only way to find yourself. You need people, but, I think at some point you have to hit the emergency brakes. You say, “Hey, wait. Where am I? Let’s have some time for myself.” I think it was a moment like that. It was also when I moved from Paris to Berlin—a kind of new reshaping of my world. I think it just connected to my situation in life. Starting with a solo album was great, but it was hard work. Maybe it’s similar to the situation I’m finding myself in today. It’s like a 10-year cycle, where now I also feel like, “Hey, okay, brakes brakes brakes. Take it slow.” I’m also thinking about making a solo album, and I’m thinking about what that would be like today.

Is there a reason for why you’re feeling that way? And what are you doing to find yourself?

It’s so sad. It’s been one-and-a-half years since the jazz club stopped and I still feel the weight from it. It’s been a long breathing out. You listen to so much music, you get influenced in so many ways, and you cannot protect yourself from so many things around you. I had to take a step back and see where I was standing. I am getting more focused—focusing on my sound, how to touch the bass. I am back to very basic things. And with the groups that I’m attached to, like [Ahmed] and Oùat, I’m willing to practice on the bass. These are long, where for six hours per day I will focus on one thing and how to do it well.

This has changed throughout the years. When I started, my attention span was different. As a 20-year-old, I didn’t really enjoy practicing alone. I couldn’t really see the reason for doing it. This was because I was in an environment of conservatory ideas and didn’t really like it. In this environment, you’re pushed to be alone in a room and play and practice, and I wanted to share it out as soon as possible. So I’ve always been doing that, and I think that’s how I learned so much—just getting on the stage and not knowing what will happen. Or, people saying, “Ah, we’re going to play this song,” and you don’t know this song, but you have to learn it. It’s quite helpful—it’s like shock therapy (laughter).

In Sweden, before I left Baltimore, I found out about this association called The Free Improvised Music of Sweden. Through that association, I connected with a lot of musicians who had similar ideas. I had started organizing festivals in Sweden before I left for Baltimore. Then, by accident, I landed in Baltimore and the first thing I saw was this big poster for High Zero: Festival for Experimental Music organized by the Red Room Collective in Baltimore, and after a few days I was involved in that whole scene. It was quite easy, strangely enough, to transition. What surprised me was how the conservatory in Baltimore… the connection to jazz was very strong. Their way of learning jazz actually worked. In Sweden, it never really worked for me—someone telling me, “That’s blues,” or, “That’s not the blues, that’s a standard.” But, the way the teachers taught you [in Baltimore]… at least a few teachers, especially Michael Formanek and also Gary Thomas, you had more of a feeling of sharing the moment with someone, and not really this hierarchic thing. The hierarchies are strong, but you don’t have this feeling that you are wrong. It was more like, “Yeah, let’s try things together,” even though technically and experience-wise, they were way, way ahead of me. You had the feeling of being accepted, and that they were also learning, and that was nice in a jazz context. Then, the outside life in Baltimore was very much similar—but more active—to the life I had in Sweden. I don’t know where we were… we were going to talk about the non-music things.

Yeah, I’m curious about that. What drew you to illustration and film? How do you feel like that informs your artistic practice?

It’s maybe the other way around, because when I was a young child I always liked to draw and write, but I kept it like a little secret. I made small drawings and wrote some text, but I never showed that to anyone. Also, for some reason, my parents rented a huge VHS camera for a summer, and I loved to walk around and film things, and I did small animations when I was eight or nine. I think I liked that because… I don’t know what it was, maybe this goes back to the idea of the body. How you can throw your body onto a piece of paper, or how your body can make an image in a film dance in front of your eyes. This visual aspect was there even before I really got into music, but then the music took over. And then, slowly, through making a label, making festivals, and doing that without any money, these things came back naturally and out of necessity. I started making posters, making short videos for promoting the music, and by doing that I always documented a little bit of my own work. It was like this secret diary that got less and less secret; through posters and films, it all of a sudden became public. It became obvious for people that it was part of my work, but it was always there. Some people really helped me—encouraged me—to do it, because in the beginning it was like, “It’s not good enough,” or “I’m a musician,” but no, you can try something and do it until it’s clear that it doesn’t work.

Some people like Mauricio Hernàndez, a Mexican filmmaker—I met him in Paris—helped me learn analog filmmaking. This I like, because it’s more connected to risk-taking. Filming with Super 8 or 16mm, you film something and you cannot erase it. It’s there. You can erase it by buying another 200 meters of film, but it’s gonna cost money. It has limitations, and I think it’s very important today to work in a way where you know there’s a limit, where you have to push and define things for yourself. In the digital field, there’s no end to the memory space—or at least that’s what we think, but that’s not true either. When you don’t have limits, you try to remake a scene 200 times, and it’s a way of looking for perfectionism, developing perfectionist ideas. But you lose that first impulse, that impact, that first panic (laughter).

You also have to be a really good comedian, or actor, which is interesting. It’s an art in itself. I also developed this on the side a little bit, especially through my work with Tristan Honsinger and Sven-Åke Johansson. All these worlds come together. It’s coming from modern ’60s jazz but there’s also a crossover into performance art and visual art and text. Fluxus, playing on the street, street theater—all this stuff comes into the world of performing modern jazz or “new” jazz. For me, it was relieving to see that someone was doing this. This made me start a group called Klub Demboh. We’d meet every Monday in Berlin, and Tristan was part of this. It’s subtitled “Audiovisual Polyphony.” This idea that we are visual musicians. So, what do you do? Do you go right or left? What do you say? You can use your mouth, your eye, your toe, but where is your brain? Is it in your nose or your armpit today? And then you start, and doing that collectively on a regular basis is extremely developing. It’s an open space for experimenting.

Sven-Åke is such a great example of a person who does so many different things and is able to synthesize it into his work all the time. What do you feel like you are doing today as a result of all these different things that you have done? How are you being pushed forward with [Ahmed] or with Oùat? Do you have specific goals with these groups?

Yeah, they are very particular. All groups have their own kind of purpose… if they were the same, I would have a problem (laughter). With [Ahmed], it’s really connected to a radical way of pushing music, and pushing the bass outside of the normal hierarchies of bass, piano, and saxophone. For example, we don’t have a soloist and we are all a part of the rhythm section. At the same time, we are not accompanying some invisible musician—we are all the musician being accompanied. So, we are both the soloist and the rhythm section at the same time. Sometimes I will hear something and think, “Wow, that’s great. Who’s doing that?” And then I realize, oh, I’m doing that (laughter). Or it’s the other way around, where I’m like, “Wow, this is so good,” but I don’t know who it is. I’ll think it’s the saxophonist, but it’s actually the pianist doing it, or the drummer. It comes from this idea of positioning yourself, of making yourself partly a rhythm section—someone pushing the others to move further, and laying the dancefloor for the dancers—while at the same time being the dancer. Much of my research in that group involves looking at Chester Zardis. What did he do? He turned his back to the audience, and slapped the bass sound into the wall and it bounced out. And for myself, how can I adapt that in my music today?

For Oùat, it is connected to this idea of, what is a song? We use the voice but, how do we write songs today? This morning, we worked on boogie-woogie. We step down into a very particular type of jazz, extract it, bring it to us, consider this idea of the screen and attention span, and see how we can make it today. So, we practice a lot. It’s the opposite of [Ahmed]—with [Ahmed], we never practice. We never had a single day where we said, “Let’s try things out.” No, we only meet on the stage. I mean, the rehearsal is the soundcheck. With Oùat, sometimes—and Simon especially—we work for maybe six hours and then sometimes that’s it. It’s a great feeling of moving forward, and then we play concerts where we never bring this boogie-woogie to the music, but it’s there, it’s kind of built into the bone structure.

With filming, me and Antonin [Gerbal], the drummer of [Ahmed], we’ve been documenting quite a lot of our travels throughout the world as a rhythm section. It’s a quite interesting, not-so-common perspective on music: a bass player and a drummer talking to musicians about their practice. We were in Cape Verde last summer, meeting batuque musicians and talking to them, connecting them to Èliane Radigue’s music of concrete music. It’s almost like a musicologist’s work. I’m a bass player holding a camera, and it opens up natural conversations and attempts at collaboration in music.

I have a group with Antonin called Vaka where we work with Freya Edmondes and Daniel Blumberg. We’re going to play in Hong Kong in a few weeks. Freya, who’s also called Elvin Brahndi—that’s her stage name—her voice, her vocals, her stream-of-poetry mixed with Daniel Blumberg’s edgy guitar… it makes for extremely sweet and sad music. It’s a mixture of extremes. There’s many things, there’s also [ism], the trio with Pat [Thomas] and Antonin. I’m going back to Senegal next week or so to continue my work with the musicians there, which is a new world to me, where I find myself in this position of, “Okay, now I really have to step back and listen and see what can we do.”

Is there anything that we didn’t talk about today that you wanted to talk about?

I’m very happy that it was such an open discussion. Sometimes it’s all, “What is [Ahmed], who is [Ahmed]?” and I think if the theme is [Ahmed], I understand. And now that there are two records coming out, I get it. But by talking about all these other things, I think we understand who Ahmed Abdul-Malik was also. The way he approached his work was like, “Okay, let’s try to add a darbuka to the bebop,” you know, what a crazy idea in 1950! And today, there are other things happening… like in Senegal, that’s how I find myself. How can we do this thing, how can we play the bass with a tama and sing and dance?

Yeah, that’s why I was interested in doing these interviews separately, because all of you guys have been involved in so many things. It felt like the only way to do this justice was to get individual perspectives and then an eventual group perspective.

Yeah, it’s such a great idea. Thank you for that possibility.

The Senegal thing is so interesting. I keep up with some of the music that’s coming out today, a lot of the mbalax, especially. Are you meshing with that whole culture, musically?

Yeah, yeah, completely. Right now, that’s what me and Simon have been talking about doing—we work with music from the Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Mali. Basically the West Coast of Africa. In Senegal, in a little village, there was this man who had 7,000 cassettes of African music—a lot of Senegalese music is on cassette, not on vinyl. It’s incredible, all of the music I’ve managed to hear. There’s this history of the music of the Ivory Coast and Mali, and I try to incorporate that. I play the gimbri, which is from Morocco, which is on the North African side. Much of my technique on the bass comes from the gimbri. The whole idea of finding new techniques for the bass so I can be heard, or so I can make certain sounds, comes from the gimbri. Also, from this experience in Senegal… I will relisten to Mingus and it’s like, “Oh, he’s doing this Ivory Coast kind of groove, adding a five to the four.” I understand the idea of swing so much better now. The way that sound has moved from West African traditions and has gone on to shape jazz… I’ve been practicing and learning and listening to a lot. It’s beautiful, and I’m just starting.

I always end my interviews with the same question and I wanted to ask it to you. Do you mind sharing one thing that you love about yourself?

I can change. I’m good at transforming. I can move on.

I mean, you see it in your own music. Even the fact that you’ve moved countries multiple times—it makes sense. I’ll see you again in a couple weeks when we all get together.

Yeah! I will be back from Senegal then, so I will maybe be a changed person (laughter).

More information about Joel Grip can be found at his website. [Ahmed]’s new albums, Giant Beauty and Wood Blues, can be found at Bandcamp. The other interviews in the [Ahmed] series can be found here: Pat Thomas, Seymour Wright, Antonin Gerbal, [Ahmed].

Thank you for reading the 137th issue of Tone Glow. Let’s all embrace change.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.