Tone Glow 138: Pat Thomas

The second in a series of five interviews with jazz quartet [Ahmed]. Pianist Pat Thomas talks about the failures of modernity, Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk, white supremacy, jungle, and qigong.

All week, Tone Glow is hosting five different interviews in celebration of [Ahmed]’s two new albums, Giant Beauty and Wood Blues. The series will feature individual interviews with all four members and conclude with a group interview. The other interviews can be found here: Joel Grip, Seymour Wright, Antonin Gerbal, [Ahmed].

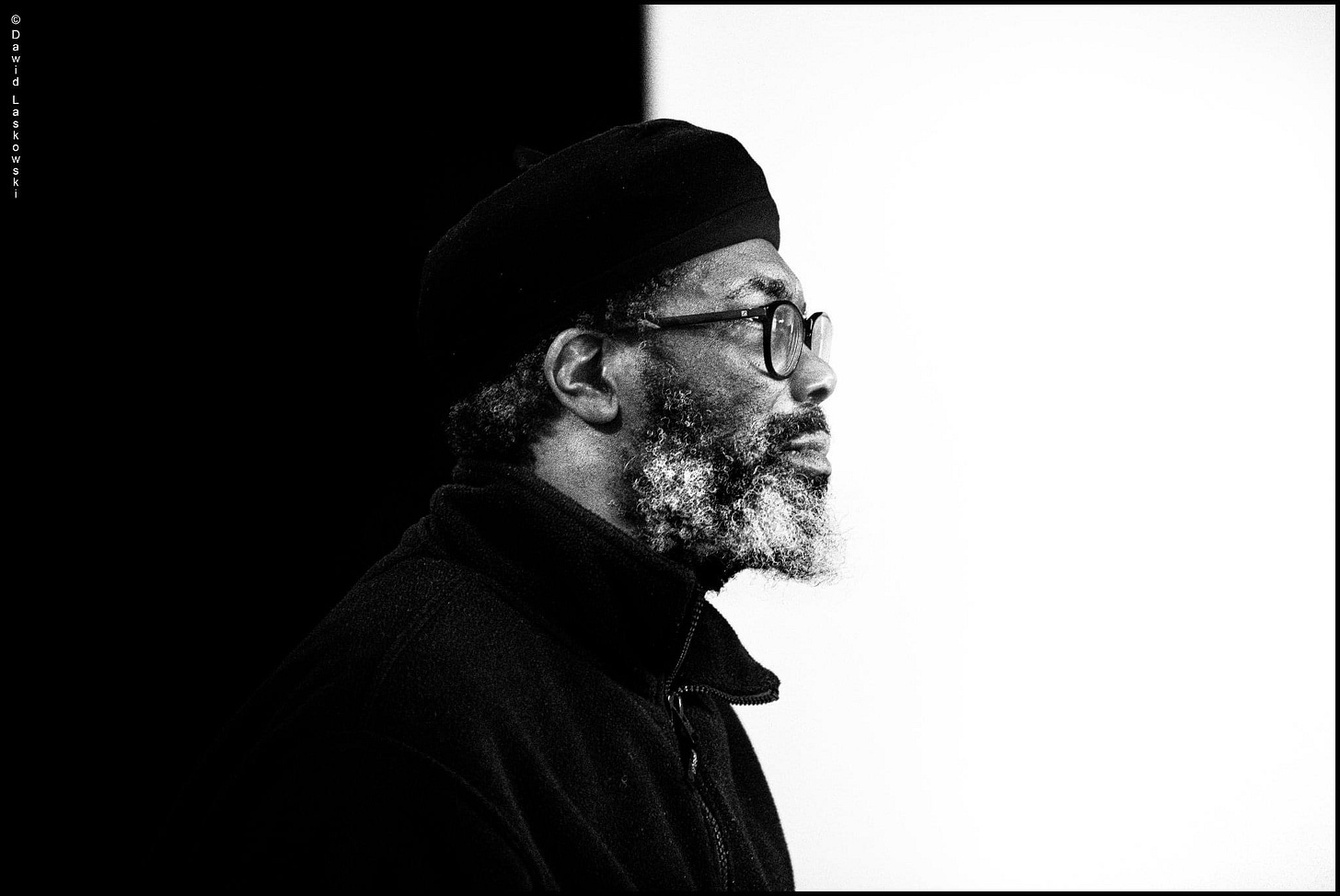

Pat Thomas

Pat Thomas (b. 1960) is a UK-based pianist who has always been interested in approaching music from a variety of different vantage points. He began studying classical piano from eight years old and started playing jazz when he was 16. His first group, M4, was a quartet that included his two brothers. As teenagers, they aimed to merge four different styles of music: funk, reggae, soul, and free improvisation. His work has since proliferated, and includes collaborations with Lol Coxhill, Derek Bailey, and Steve Noble. In 1997, he released New Jazz Jungle: Remembering, an electroacoustic album that saw him considering ways to expand the form of jungle. He has played in multiple groups, including [Ahmed], [ISM], About Group, HISS, Circuit, and Valid Tractor. His new solo album, WAZIFAH volume 3, was recently released by scatterArchive.

Joshua Minsoo Kim spoke with Thomas on February 22nd, 2024 via Zoom to discuss how qigong and being Muslim are related, the genius of Duke Ellington and Thelonious Monk, how his life changed after having a stroke, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: You’ve said in the past that Duke Ellington is the musician and composer you admire most. I love your performances of his music, especially those on Plays the Duke (2022). Do you remember when you first heard his music and how you felt?

Pat Thomas: Probably like most people, the first time I heard him was on TV. They used to do jazz programs in Britain. And it might have been Cabin in the Sky (1943). I just remember this beautiful sound—it could’ve been “Mood Indigo.” I was really impressed with just the sound of it. You suddenly realize that Duke Ellington was the only one who could’ve influenced Stravinsky (laughter). Those tone colors you hear in Stravinsky—I think Duke was doing it first! Just the range of his color palette is so different from anyone else you come across. And the Ebony Concerto, you certainly hear a lot of Duke in that. My father had one of the early Duke Ellington records, and that really blew me away. And then when I heard Black, Brown and Beige, I was a fan forever! (laughter).

You heard him early on, you saw him on television, and now you’re in your 60s performing his music. What do you feel like you’ve learned in listening to, studying, and playing his music?

I only started to approach playing Duke’s music later. I was asked by Cafe OTO if I would want to do some solo piano, and Monk and Duke were my first choices. I played a bit of Duke in groups—on the trio album, BleySchool (2019), we play “In a Sentimental Mood.” So it was only in my late 50s that I started to seriously look at his music, but he’s always been one of the greats. I use this phrase—structural integrity—and I feel that all his compositions have this structural integrity that allows them to be malleable. They’re recognizable. If you want to tear them apart, you’ve still got to work with that material. And that’s the sign of a great composer: we’ve heard so many different ways of playing Duke, and it’s still recognizably him. That’s special to me.

Let’s talk about a specific song. You’ve played “Prelude to a Kiss,” and there are many renditions of that piece, including versions with vocalists like Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. How are you approaching a song like that when playing it live? How are you making sure that you are there in the song while still honoring Duke?

I suppose my method would’ve been assuming I’m playing, say, Elliott Carter. Like, how would Elliott Carter or someone like Schoenberg approach Duke’s music? And that’s how I got to how I decided to play it. Like, not so much Lachenmann, but Carter or Schoenberg. I approach it as if I’m playing contemporary new music. I mean, it is “new music,” but I’m approaching it from a classical new music perspective, and with my understanding of jazz as well. There are people like Howard Riley, and he’s done a great record of Duke [1993’s Beyond Category] and I thought, Duke’s music requires you to think outside of the box.

It’s interesting to hear you mention other artists in your response. Do you feel like you hear yourself in your music at all? How much of yourself do you even want to be in the music? Does that matter?

I believe that I’m always part of a lineage, whether I like it or not. So I have these two streams, the classical stream and the jazz stream. And I’m also interested in reggae, like Lee Perry. I want that confluence, I want to know how to combine all these different sounds to make my own. That’s how I approach music. Looking at Duke, I might think about his Latin Suite (1972), and then to get to my approach, I may think of the rumba in terms of dub style. Like, I may think of how King Tubby might do that, and then combine it with Stockhausen. I want to dip into all those streams at the same time.

You mentioned your father earlier. Do you mind talking about your parents?

My parents were very very perceptive. They didn’t tell me this until later in life, maybe in my 50s, but they had a bet on what I was going to be (laughter). I had just seen Liberace on the TV and I didn’t really know who he was, but I was mesmerized by what he was playing. This thing he was in front of—this huge white piano and candelabra. When you’re a kid, you just start moving your fingers around anyway, and my mom said, “Oh, I think he wants to play the piano.” My dad, who was probably being rational, was praying that I’d be a doctor (laughter). My mum was right and she won the bet. When she asked if I wanted to play piano, I thought all of them would look like Liberace’s (laughter).

We were very fortunate because we were very Caribbean—my family is from Antigua—and my parents were very cosmopolitan in their tastes. If you were in a certain position by the stairs, you could hear Funkadelic and Derek Bailey playing at the same time. I grew up in that sort of environment, so it’s natural for me to combine these different elements.

The first band I played in was with my brothers called M4. We had a bass player friend called James, and that was our version of funk, reggae, and soul with a bit of free improvisation on top. My parents are very liberal in the sense that when people were complaining, they’d say, “Well, at least they’re in the house and not on the streets!”

The band was called M4?

Yeah, because the motorway to London was M4. And we were thinking about it as “Music 4” because we were thinking about the four different types of music we were combining.

How old were you when you were in this band?

At the beginning, I probably would’ve been about 17 and my brothers would’ve been 15 and 14. We were the perfect house rehearsal group—we didn’t do a gig for about 20 years (laughter). We were tighter than tight, I tell you. It was only because one of my mentors, Michael, asked me what I had been doing. I showed some M4 tapes and he said we had to play, and I was like, “Really?” We just used to practice incessantly. It was a family thing, and we didn’t really think about playing live.

What did your brothers play?

My brother Evan was the guitarist and he still plays—he’s a top teacher in Oxford. My other brother used to play the drums but then quit to become a world champion at kickboxing. And after that, he became a top test driver for BMW and just retired. We’ve got a hyper family, we’re all achievers. I’m the one who got the crazy, you know, “try to be an artist” thing (laughter). My other brothers were a bit more sensible. I should be doing a gig with Evan later this year in a group called The Locals. That was the legacy of M4—we would do jazz-funk versions of Anthony Braxton.

Right, you had the album on Discus. What’s it like to play with your siblings?

I remember Ornette Coleman said that him and Don Cherry never counted. That was the vibe we had. We never really counted because of that sibling connection, and it was only when I started playing with other people that they’d be looking at me to count them in and I’d think, “What are they looking at me for?” (laughter). I’d play with other people and they’d be like, we’re gonna do this cue to stop. And I’d be like… cue? (laughter). I was so used to playing automatically with my brothers, it was like our biological clocks were in sync. It took a while to adjust to play with other people.

And it’s funny because the goal is to get to a point with people where you can just stop playing without having a cue. I love that you started in the opposite direction, by beginning with this instinctual experience.

When you start to play with certain groups, you’ve got a group mind sense and you know when to stop. And that’s important in any improvising setting.

I remember talking with George Lewis and he said that something that robots or AI would not be able to do is perform music and know when to stop.

That’s my whole thing about AI. I tell people that we have nothing to worry about. They don’t know when to start, they don’t know when to stop. The reason we haven’t got driverless cars is that there may be kids who just jump out in front of them, and I’ve seen so many bus drivers whose reaction times are incredible. Those kinds of things can’t be done with probabilities. These are good tools, but we have to remember that AI stands for artificial intelligence. It’s not real intelligence. Someone may teach a parrot to keep saying E = mc2, but it won’t know what it’s talking about. Some might think, wow, that parrot is a genius, but it’s not. AI is just oversold. I did a piece in ’89—this was during the early days of computers—and it was for computer and voice and trumpet. I had modules and had them do these random events and at the end, people may have thought it ended on its own, but I just switched it off (laughter).

You’ve said in your piece for The Wire about dub that it was “the first experimental electroacoustic music [you] heard.” Do you mind sharing about those initial experiences?

In my community, everyone went to the soundsystem—at least when you were allowed to go to them. I think I was around 14 or 15. We’d have close-knit families so my parents knew that there was this one place that everyone was going to, so if there was a problem, they would know where to find you. There weren’t that many places, especially in Oxford, where the blues were gonna be. I did the usual thing where I heard something on the radio and I would get up early on a Saturday morning to get the dubplate first.

The problem with so-called “Black music” is that because of the hierarchy, no matter what we do, it’s always considered “popular music.” There’s no conception that the music could be popular and art at the same time. The things that King Tubby and Lee Perry were doing were incredibly complex—they should be taught whenever someone is learning about electronic music. You’ve got to include those people. You think about the stuff that Bernie Worrell was doing on the synthesizer in P-Funk and it was really out there. It was Sun Ra level. And of course Sun Ra himself had the totality of everything. “Nuclear War”? You can’t get funkier than that, and it’s still out there.

You have to acknowledge that white supremacy exists, that Western classical music is seen as the be-all and end-all. And your music is judged on how close it is to that model. I mentioned how I was in a musically eclectic family. And in Antigua, it’s a small island, but believe it or not I could hear during the daytime, Art Tatum, Sonny Rollins, Stravinsky, zouk, calypso. You know what I mean? I can say that in the little village that my family is from, Swetes, nobody thought it was unusual to sit on the porch and listen to classical music.

I love Stockhausen and Schoenberg and the whole Second Viennese School, but we have to remember that at the same time, the concert hall is a strange concept. You have to go somewhere to hear music. In most other cultures, you hear music all the time! It’s part of your everyday life. You’re restricted to what time you can play in the concert hall. And because of that, a lot of traditional music, like Indian classical music, is already compromised, because that can go on all day.

With King Tubby, I remember that I always wanted to know what he had done with a song. It could be Gregory Isaacs or Dennis Brown or whoever, and you’d love the song, but you’d want to know what he or Lee Perry had done. It was an experimental tradition that was built in.

Do you consider what you’re doing when interpreting jazz standards to be similar?

Like with versioning? When I heard Monk, it straightaway appealed to me. There’s definitely a Caribbean vibe, and I found out he lived in the Caribbean area of New York. He was surrounded by calypso. People forget that what originally influenced hip-hop was the soundsystem, the toaster. And you grow up with things and absorb them and later on, it’s there. When I was younger and heard the AACM and the Art Ensemble of Chicago, to hear them incorporate all these different things at the same time had a profound influence on me.

I’m thinking about your early albums with Lol Coxhill, Halim (1993) and One Night in Glasgow (1995). You already had this interest in incorporating electronics into your practice. You have, for example, an amen break in the song “Tremble,” there’s a hip-hop beat in “Updown Sidney,” there’s another breakbeat in “Shake Well.” What spurred you both on to work with samples and such?

Lol was a great mentor and a great musician. He was someone who had this great, really eclectic tradition. He played with Hendrix, The Damned, Derek Bailey. He didn’t really have any barriers. When he asked me to do a duo with him, it was a great honor, and there was no problem because he expected me to be able to incorporate all this stuff. That’s the good thing about growing up in that time in the improvisation scene: there were people who were opening things up. It’s not that they were playing pop music, but it wasn’t seen as a sin to play a melody (laughter).

The first generation tore the house down, they broke barriers—it was a lot like Schoenberg. It was a very deliberate system to avoid anything recognizable, and with free improvisation, we have to remember that this is a post-war generation. They were coming from the experiences of the Second World War. Nobody wanted to hear “All the Things You Are” again, you know what I mean? Things changed throughout the ’80s and ’90s, and now everyone is more open to new things. But when you’re creating a whole new system to distinguish it from the old, you’re building these bricks.

Just to clarify, your parents were from Antigua and then moved to England?

Yes, they were invited to England after the war, so it was probably in the late ’50s when they were trying to basically rebuild the empire. I remember my mum telling me that they would say how the streets were paved with gold and that they should go to the mother country. There was this huge shock when they got there. “The streets were definitely not paved with gold, they were actually pretty smelly.” (laughter). And they were definitely not welcome.

I don’t think the government told the people in England that there’d be a bunch of people from the islands coming here. What I really appreciate from my parents is that I think they protected us from the very vicious sort of racism that they dealt with. We grew up in a really lovely environment. And to be honest with you, I didn’t realize I was a minority until I started going to the other side of the Magdalen Bridge (laughter). We used to go to a Black Sunday school and used to have house parties and we were always around our community. It was a reality check when I realized, oh, not everybody is Black in Oxford. And sometimes people think I’m the only Black person in Oxford—they don’t think there’s a Black community there. Crazy.

A lot of the smaller island people went to the Midlands, so Oxford, Leicester, and Derby. And the reason was because of the car industry—anybody could work there. In the ’70s, my dad’s job until he retired was there. He was there for maybe 40 years. My brother was a test driver and started out on the floor, but he was there for maybe 40 years too. And that would’ve been normal for most people because it was more stable. A lot of people from the islands would’ve been bricklayers or carpenters but they realized that if they wanted a stable income, the easiest way was to work in one of these factories.

You mentioned these house parties, do you have any good memories of them?

The best one that’s still in my head is when they really dropped the bass. This is a house, and the walls are rumbling. And you’re like, yeah, I know I’m in a house party because the walls are trembling. It wasn’t like we were in a hall. I remember thinking, if this continues, there might not be a house left (laughter). Everybody was crushed against the walls, it was pitch black—it was fantastic.

Are you interested in your audiences feeling this sort of physicality when hearing your music?

Because I’ve been brought up in that environment, I think I am. And I think that music should be touching people’s hearts, so not just physically. Your whole thing should be trying to uplift people. I’m not talking about entertainment. I’m hoping that if people come to my gig, they feel better, at least temporarily.

I just saw a study that said that dancing had the greatest benefit for people with depression, and it was more beneficial than meds and therapy and other exercises.

Think about it: In most cultures, it’s all integrated anyway. It was what I was saying about the concert hall concept earlier. You can’t move that much in that space. You start nodding your head too much and people will notice, they may think there’s something wrong with you. But if you watch reggae, if you see Dennis Brown, someone may think there’s something wrong with you if you’re not moving your head (laughter). I remember growing up in the ’70s, most of us felt that going to the blues felt like a cleansing, like we could deal with the week. There’s something liberating about music, and I’m not surprised that movement and dancing are central. I remember I went to a classical concert and someone coughed and people were like, “How dare they cough!” I mean, that’s just human. Really? Coughing? Now imagine tapping your feet. When I’m there I feel like I have to sit there like a ghost.

Did you frequently go back to the Caribbean when you were younger?

I was a classic English boy pretending he was Caribbean. And bless my parents, they would say, “You’re not from the Caribbean. You have a Caribbean background.” It was only when my parents moved back to Antigua that I went with them and I fell in love right away. I’ll tell you why: it was the first time I actually felt free. When I went to a shop in Antigua, nobody was watching me. When I go into a shop in England, my spidey-sense is turned on and there might be a security guard next to me, stuff like that. I realize, now, that it’s why my dad didn’t like to go shopping in England. He’d always say to my mum, “Give me a ring when you’re ready.” He hated shopping. And it’s because when you’re a Black male, that’s what you deal with. When we went to Antigua with my parents, my dad would say, “Oh, when are we going shopping?” And I realized why. That’s also when I fell in love with this idea that you could go into this community and just be you.

How old were you when you visited?

I would have been 46. Because it hasn’t been so ruined from modern industrialization, you could see the stars. You could see the moon! It was incredible, and it made me realize that we’re missing so much. When I came back to London, it took a while to adjust. Everyone’s always running! Even if there’s another tube coming in a minute, everyone’s running as if it’s the last tube on Earth (laughter). It changed for me as I got older, post-stroke. I just wait. The pace is now slower, and I have more time to reflect. I wake up to the sound of the crickets in the morning.

It’s interesting how a hallmark of modernity is this distancing of ourselves from nature.

The problem with modernity is this lack of respect for tradition. What we call modernity is… like, are the ’70s still “modernity”? Is progress for the sake of progress good? Is it not a problem? It’s like we’re denying what’s come before us. One of the things that really helped me when I had the stroke was discovering qigong—that’s like a 5000-year-old tradition. Within 10 minutes of doing one qigong movement, I started to realize, it looks like I will be able to play the piano again. And I wasn’t quite sure when I was using Western medicine. I mean, you take things in a balanced way, but the problem with modernity is that this idea of “newness” cuts us off from tradition.

People say things like, “I don’t know how people survived without a mobile phone.” Hello??? (laughter). We survived without them! And most of the time we don’t need them! We get into a view that we feel like we do need them. The first thing I used to do when I woke up was check my email. And when the email was down, there was paranoia! “Oh my god, I’ve probably lost 25 gigs today.” And of course there’s nothing there (laughter). There’s so much awful architecture associated with modernity. You go to Antigua and you may have these tiny shacks, but they’re surrounded by fields! I remember the first time I went there, the cars had to wait while the goats crossed the road. You know what I mean? And this is the sickness of modernity, that it’s cutting people off from traditions all over the world. People don’t recognize all this beauty that is there. You can’t even appreciate the sunset or sunrise, people only understood its beauty when COVID happened (laughter). At the time, people around me were saying things like, “What’s that sound?” And it was the birds singing! (laughter).

The thing with modernity is this thinking that we have surpassed all previous generations. We’re “more scientific.” And when I think about being in a band with my brothers, that wasn’t a scientific thing, it was this connection—it was spiritual in some sense. And the best improvised music surprises people; nobody says a word and everyone knows when to start. One of the problems with modernity is the lack of metaphysics. There’s something else there. Most people don’t reflect on what they’re doing. It’s only when they get ill that they might start thinking, “What the hell am I doing with my life?”

You mentioned having a stroke and that qigong helped. Do you mind talking more about that?

It was heavy because I had been looking after my mum. I remember I had a headache that day, and I realize now that it was brought on by the fact that they wanted to give my mum some new medication. And you know, the minorities are always the guinea pigs with these new medications. I was trying to check what it was and what the side effects were, and I wanted to get some helpers since I was also gigging. It’s all about time management, and as you get older, things take longer. I remember I went to bed thinking there was going to be a confrontation, that I was going to have to talk with these people, and this was the same day I had the stroke. I think it had been building up. I knew something was wrong because I was always a fit person. It was only when I went to the hospital and saw the MRI scan that I knew it was really serious.

My mum passed away because I couldn’t look after her. It was a tough time. I personally do not see this world as the be-all and end-all, it is a testing ground. As an artist, you’ve got to find ways to turn things into something positive. That’s the role of the artist. You think of Billie Holiday. She hardly had a picnic of a life and you think about how profound the music she made was—it really touches people.

Do you think that qigong shaped the way you think about the piano?

I was always into movement but I realized that playing the piano was, in some ways, like a qigong exercise because of the concentration and the movement. To think about playing and for it to happen at the same time requires a certain flow. It took me a while to get my chops back, but I think the qigong helped. It helped me realize the capacity to concentrate easier. When you have a stroke, you really have to… I mean, when I first had it, I couldn’t even write my name. I had to be really conscious of what I was doing. It’s one of the great ironies that John Zorn, who I hadn’t seen for years, asked if I would be up for writing something. And I said yes. And that’s when I realized that a stroke ain’t gonna stop me. Even though I can only type with one finger, I’m gonna write something (laughter). It was a blessing in disguise because it made me realize that it’s your willpower that will get you through it. You’ve gotta be positive. And that helped me a lot.

What I love about the qigong exercises is that they’re nothing strenuous. It’s nothing crazy. There are these other exercises and you see them and it’s like, “no way. They’ve been doing qigong for 5000 years. The West still poo-poos the ideas of energy, but if it hadn’t been for that I wouldn’t be here talking with you. The problem with modernity is this refusal to accept the unseen. There shouldn’t be a divide between the spiritual and the material. I wish people knew that you sometimes just need to do these simple movements.

You had the album, New Jazz Jungle: Remembering (1997), and Derek Bailey had the album Guitar, Drums ‘n’ Bass (1996). Did you have conversations with him about drum ‘n’ bass and jungle and performing to this style?

We didn’t have conversations but we all knew that Derek was practicing to this. He would tell us that he was listening to pirate radio and playing to jungle. I was gobsmacked because you know Derek’s hip but you didn’t know he was that hip (laughter). I did my thing later. Our approaches were very different. I was approaching jungle from a compositional standpoint—there are these structures in jungle, and I was thinking about what I could do to extend them. Derek was improvising to it. And he had the album on scatterArchive [2022’s Domestic Jungle]., but the first record happened because the people who were gonna put it out were worried about publishing issues since he was just improvising to the radio. They thought they could get sued!

We know that jungle became more normal, and it’s because the market takes over. It became drum ‘n’ bass. But at the beginning, jungle was experimental music. They were thinking about the possibilities of what could be done, and that’s why I think improvisers were very interested in it. Mike Cooper liked it too. It was a sort of dance music that we could get into—there weren’t regular song structures or choruses. It was great.

Derek would never rest on his laurels. He would always think, “this is going to push me, so I’m gonna practice along to that.” When you listen to his later stuff, there’s more of a jagged rhythmic thing going on, and that’s probably why he liked practicing to that stuff. When you think of all he did on Tzadik, it’s very different than what he did earlier.

Right, that’s what I always admired about him. He always pushed himself.

I did a tour with him and Steve Noble on turntables. Zorn had been out to do the Barbican, and it was going to be Derek’s 70th. And of course, nobody was into anything to do with Derek, so Zorn—bless him—was asked to do the Barbican and he said he would only do it if they booked Derek Bailey. Then of course, the marketing people had heard about the drum ‘n’ bass record and they told Derek, “Oh, we’ve got a DJ you can play with. We think it’d be great if you could play with him when you’re here.” Derek tells them, “Don’t worry, I’ve got my own DJs.” And they thought that was great, but he was talking about me and Steve Noble! (laughter). And they really weren’t happy with it. There are certain things you never forget. They actually put on the poster, “We didn’t book this.”

They actually wrote that?

Yes. And just to emphasize how much they hated us, we didn’t have a dressing room between us. That’s how welcome we were. We were really outcast. I will never forget that. We actually had this record, AND (1997).

I wanted to ask about your solo album on Emanem called Nur (2001). Rest in peace Martin Davidson.

It was so important and that was my first solo piano record. I remember that he said to me, “Is there anything of yours where you’re not playing electronics?” (laughter).

That makes sense for him and the label.

I had just done this thing in Cheltenham, and there was this guy named Chris Trent who recorded it. He’s an expert on Sun Ra’s music. He used to come to these gigs and record everything. I remember there was this guy who recorded Derek’s record in Brixton, his name was Toby Hrycek-Robinson. He actually made it much more listenable. So again, there was this connection. This guy was really interesting because he worked with Stockhausen. He ended up having this wonderful studio [Moat Studio] in Brixton. You know Ballads (2002), that was recorded in Brixton by this engineer. I remember that Martin, bless him, was really so important because nobody was interested into this music. This guy had a job as a computer programmer. These records were a loss leader, to put it mildly (laughter).

But he was releasing them and he was very important. They did a great tribute for him but sadly I missed my gig. The coach I was on, for some bizarre reason, went the scenic route and took an extra hour and a half. I was supposed to play with Evan [Parker] in Trance Map+, but by the time I arrived, they were finished. But at least I got there and it was a great turnout. He was really great. He never said, “You gotta do this or do that,” so I did a lot of different things. He had his taste, but if he said he wanted you on a record, that was it.

The last song on Nur, “The Analogy,” was you wanting to honor Thelonious Monk. Do you mind sharing about your relationship with Monk’s music?

When I knew I’d be able to play the piano again after the stroke, my test piece was “Evidence.” That is a very specific piece, and you cannot second guess it. If you don’t know where you are in “Evidence,” you can’t play it. And to know that my fingers were working… I think after I played it, I made an announcement that I could play again (laughter). The thing about Monk is that even though he’s a pioneer of bebop, his style is so pianistic. All these people started imitating Charlie Parker, but Monk was playing in a pianistic style. So even though he was writing these tunes that were part of the bebop canon, his style wasn’t Charlie Parker, he was playing Monk.

If you think about it, Charlie Parker’s model would have been Art Tatum. What he did on the saxophone was revolutionary, nobody thought of doing all that on the saxophone. But Monk was very pianistic, so it was funny when people used to say, “Can Monk even play the piano?” You can’t get more pianistic than Monk! What nonsense. And Duke influenced Monk. Of course, Money Jungle (1963)... how many people can play the piano like that? If I was on a desert island, I would just choose that disc and I could survive… assuming that I have electricity and a record player (laughter).

What has it been like for you to play and be in [Ahmed]? What is new for you to be in this specific group?

We were talking about the group mind. I’ve been playing in a trio with Joel and Antonin called [ISM], so we had a really strong group sense as a rhythm section. And I’ve known Seymour since he was 16—poor guy (laughter). His father, Geoff Wright, was one of the few people who used to book me. He would help organize jazz concerts in Derby. And one of the things that happened, when Seymour went to university, was that his room would be one of the rooms that you’d stay in. His record collection was insane because, you can imagine, Evan Parker and whoever else would leave a record as a present. When we heard that Seymour moved to London, we couldn’t care less what he was learning. He could’ve been learning quantum physics, but we just wanted to know what instrument he was going to play.

What’s really special about the group is that we’re able to combine the jazz tradition and superimpose it with a free improvisation aesthetic. Even though we’re using a composition, the way we approach it is that when we play a piece, when we turn up, we may say, “Oh let’s try ‘Ya Annas’ or ‘African Bossa Nova.’” We won’t do anything until we get there, we’ll go through the piece just to play the tune, and then that’s it. We improvise. The arrangements are spontaneous, and I think that’s special. There are things that people may think are worked out, but it’s all improvised. I think that’s because we’ve got a very strong group sense. I have to say, with those guys we always know when to stop (laughter).

This wasn’t planned. We went to Hong Kong and were supposed to make a record for this label there. We were booked as the party band, which was hilarious and completely insane. But we did lock in. If you see people trying to dance, you will start trying to lock in—it’s just an unconscious thing. And I think that’s when we turned into [Ahmed]. At the time, we were a group still working without material, and we were getting there, but this Hong Kong trip solidified it. It was one of those fortuitous things. The gallery was Empty Gallery, and this recording became Super Majnoon (2019)—it was different from the first record [2017’s New Jazz Imagination]. I remember playing this back and we were like, “What the hell is this?” We got into this real repetitive groove but it was also so abstract. Seymour just locked in.

I remember in Hong Kong, they couldn’t get a grand piano in because it was on the third floor, so they got a really good Yamaha upright. In some ways, that probably helped as well, to get me to be more percussive. Because it was an upright, I wasn’t gonna be doing anything inside [the piano], and so I really had to think about how to make the piano work in this context. And so I started working very percussively and becoming a drummer in a way. Antonin is like two drummers anyway, and the way Joel plays as well… I guess you could say we’re all a bunch of drummers with Seymour on top (laughter).

There’s a question I end all my interviews with and I wanted to ask it to you. Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

I think it’s that I’m positive. I’m not gonna lie, I’ve gone through it. The lowest point in my life was when my mum passed away, and I couldn’t even get to the funeral. I remember the day… I cried as much as you could possibly cry. I have no tears left. I’m a very religious person—-I’m Muslim—-and I felt this was the heaviest test I have ever encountered. When Zorn asked me to write, I mean, I wasn’t gonna say no to John. And at the time, I couldn’t even hold a pen. So thank God there was this technology where I could tap these letters. I always think about how bad it is, but I have to be positive. And as an improviser, you really need that. I mean, you don’t make much money either.

Do you mind sharing something about your mother?

Like I said, I wouldn’t be here unless my mum won the bet. She was a really beautiful person. She seemed to know what children needed—-not what they wanted, but what they needed. She was great at nurturing and giving us our potential. We’re all overachievers. We were three Black kids from Oxford. My parents were both positive but my mother would always ingrain in us that we could do whatever. “If you’re gonna be a trapeze artist, make sure you’re the best ever.” It was this whole thing drilled into us by our parents—-you’ve gotta be the best you can, and don’t let circumstances hold you back. My parents weren’t rich and were dealing with racism, and to be this positive—to make sure that their kids weren’t going to feel inferior—that’s what got us through it.

My dad was great also. He had me doing his accounts at eight years old. I was like, “I’m an eight-year-old kid! Why am I doing the banking? I don’t even know what a bank is!” (laughter). But I think he wanted us to know that we were gonna have to get ourselves sorted. My brother Evan was getting bullied at school and my dad did this reverse psychology. He said, “If you come home tomorrow and tell me you’ve been bullied, I’m gonna beat you.” And on that day, Evan turned into a lion! I was very blessed to have my parents. They wanted to prepare us for those tough times.

You mentioned that you’re Muslim, and on the Nur album there’s the track “Mubarak.” I’m wondering how your religious practice impacts your approach to music.

To be honest with you, I wouldn’t have become Muslim if it hadn’t been for the music. I was into a lot of jazz and what happened was that I was checking out all these players like Yusef Lateef. I started reading books about Sufism and there was this book that was very influential to me, The Mysticism of Sound and Music by Hazrat Inayat Khan. It’s one of the few books that even Stockhausen acknowledges may have been an influence. It had this whole concept about sound that really inspired me. It was about how sound isn’t just physical, that there was also this spiritual level as well.

That really has been something that modeled my playing because one of the things about piano, and this is what I love about Monk, is just this idea of sound. He’s instantly recognizable on a piano! And that’s supposed to be impossible! It’s a mechanical instrument, it’s supposed to have this constant sound. But one of the great things about the jazz tradition is that you know a piano player from their sound. It’s not like a saxophone where you can work and have the reed. You never know the piano you’re gonna be on, and yet, Monk always had his sound.

After you get deep into Sufism, you realize there’s this whole tradition. What I liked about the Sufi tradition is that, well, there’s a beautiful verse in the Quran that says there is no compulsion in religion. This means that people have their own way and that you’re not supposed to impose anything. You’re not supposed to say to people, “You have to do this and that.” And that to me was very fresh. You meet these New Age people and they say, “I meditate six hours a day, you should try it.” And I say, “Leave me alone.” (laughter).

In Islam, we don’t have this concept of religion in the way that people in the West do. This is a life transaction, it’s part of your life. And that’s probably why I relate to qigong. It’s this whole way of doing things. And you read about these qigong masters—they lived it and breathed it. That’s what I like about the traditional Sufi, Islamic way. You don’t judge people. You don’t say, “Oh, this guy’s not doing this or that.” And I think that has an effect and helps with the music. Just because I came from a classical background doesn’t mean I think, “Oh I can’t play this.”

Today, there are a lot of good technical piano players, but to me, a good piano player is one who can move me with a couple of notes. We were talking about modernity, and there are pianists who are playing pieces to perfection. People forget that Bach was an improviser. He would be surprised that people are trying to play the right notes all the time. And we know Mozart wasn’t into that—we know that for a fact. And we know Liszt was a great improviser too. People are into this precise way, and it’s not liberating, it’s a straightjacket. There’s this term, deen, which is less like “religion” and more about this complete way of life. That’s what has influenced me. I didn’t think that I couldn’t do qigong because it was from China or whatever. We’re told that whatever is going to be a benefit to you is yours. Just let it happen and see.

Pat Thomas’ new album WAZIFAH volume 3 can be found at Bandcamp. [Ahmed]’s new albums, Giant Beauty and Wood Blues, can be found at Bandcamp. The other interviews in the [Ahmed] series can be found here: Joel Grip, Seymour Wright, Antonin Gerbal, [Ahmed].

Thank you for reading the 138th issue of Tone Glow. Just let it happen.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

I don't know his music, nor I haven't heard of him until now, reading this interview. Thank you for this piece.