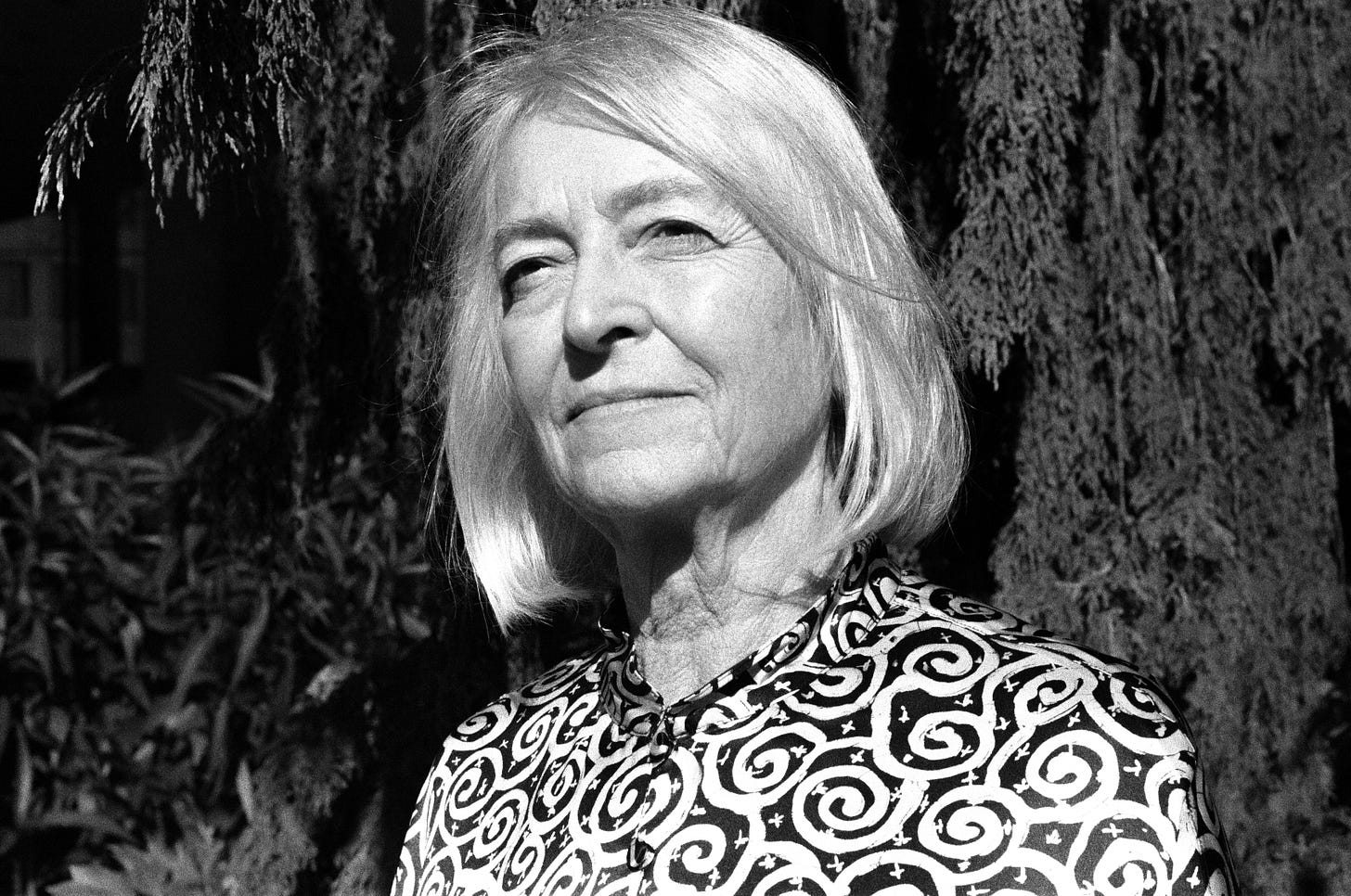

Tone Glow 107: Joan La Barbara

An interview with the American composer and vocalist about laughter, collaborating with her toddler, working on 'Sesame Street' and 'Alien: Resurrection,' and three stories about John Cage

Joan La Barbara

Joan La Barbara (b. 1947) is an American composer who has spent decades exploring the capabilities of the human voice. In utilizing multiphonics, circular singing, glottal clicks, and various methods of extended vocal technique, she has remained one of the most essential and innovative vocalists of the past century. In addition to composing works for chamber ensembles, musical theater, and orchestra, La Barbara has collaborated with dance companies and worked alongside numerous avant-garde composers such as John Cage, Morton Feldman, Philip Glass, Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley, and her husband Morton Subotnick.

Her earliest recorded material appears on Voice is the Original Instrument (1976) and Tapesongs (1977). The former features Voice Piece: One-Note Internal Resonance Investigation (1974), which involves exploring the color spectrum of a single pitch by placing it in as many different resonance areas as possible. The latter features Solo For Voice 45, which was composed by John Cage and determined via chance operations and star maps. In the decades since, she’s released other vital records including As Lightning Comes, in Flashes (1983), Sound Paintings (1991), and ShamanSong (1998). Joshua Minsoo Kim spoke with La Barbara on October 28th, 2022 in Evanston, IL in light of her residency at Northwestern’s Bienen School of Music. The two discussed the adjustments needed to adapt to a changing body, lending her voice to Sesame Street and Alien: Resurrection, John Cage’s “lifetime commitment” to her, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: You were born in Philly, what sort of things do you remember about growing up in the city? What stands out?

Joan La Barbara: Well, it’s a totally different city now than it was then. I mean, I was born in ’47 (laughter) in Jefferson Hospital, downtown. My parents moved to Frankford, which is not necessarily an area you would know, and then they moved out to the suburbs. We lived for a long time in Cheltenham, Elkins Park, and then we moved to Abington. Of course, the Philadelphia Orchestra was there and ever-present in the cultural scene. As a kid, I went to see all the concerts of the Philadelphia Orchestra. I can especially remember Robin Hood Dell, which was wonderful—watching concerts outside and everything.

But I was really anxious to get away from Philadelphia. I wanted to get my life started someplace else. I went to Syracuse for three years, and then I was anxious to get to New York, so I transferred to NYU. When I got out of NYU, I started doing everything. I did improv and commercials, I sang jazz, I sang rock. I wasn’t very good at rock (laughter). I found my way into the contemporary music scene. At the time, it was a cross-section of contemporary classical and new music, fusion, and jazz. Everybody was working together, trying things out with a lot of free-form improvisation sessions and stuff like that.

Was your family musical at all?

Not really. My grandfather taught me to play piano when I was about three years old. But no, my parents were not really into music. They got me piano lessons, because I think it was the thing to do, but I don’t think they ever thought I would go into music as a profession. They did everything they could to discourage me (laughter).

What sort of things would they do?

Well, that’s not quite true. When I was in high school, I was in a folk music group, and they were very supportive. They would drive us around and drop us off at the coffee houses where we were performing. They were supportive that far, but they really felt that when I went to college I would go into something else in spite of the fact that when I went to Syracuse, I was duly enrolled in the music department, studying voice, and also in the English department. I hadn’t really made up my mind. I was very interested in poetry and creative writing. Once it became clear to them that I really was interested in music as a profession, they were as supportive as they could be. They would come to as many of my concerts as they possibly could, which was very nice.

Tell me about these folk music groups that you were in when you were younger.

It was just a four-girl group called The Calicos. Four people from my high school. We got together and we would play local folk music concerts. But it was just something to do—you know, learn to play guitar and go out and sing folk songs.

It’s interesting to me that you were enrolled in English while studying voice. At the concert on Wednesday, you mentioned James Joyce when introducing “Erin.” How do you feel like your interest in poetry and literature have shaped your understanding of using your voice?

That’s a really interesting question, because I am and have been invited to perform my work at a lot of poetry festivals. I think the poets consider it in the stream of text-sound work. I think about the Italian futurists—parole in libertà—and the Dada movement. Language is actually part of my compositional process. When I start a new piece, I do stream-of-consciousness writing for everything that comes to mind. I try not to censor, I try not to say, “Oh, that’s a silly thing to write.” I’m trying to get into my mind, into my interior dialogue about the subject matter. That’s very much a part of my process. I haven’t used actual words very much in my compositions. Although, that being said, I did do several specific pieces like ShadowSong (1979), which uses words in various languages for ghosts and shadows, and Berliner Träume (1983) which uses words in German and English that refer to my memories of living in West Berlin. But there are certainly pieces where imaginary language is part of it. “Erin” is very much something like that, or a work of mine called Conversations (1988), which is about what language sounds like, not necessarily what language means.

That’s something I’m very interested in. One of the more exciting things about language, for me, is the fact that when I am speaking a different language, I feel like I’m adopting a different personality that’s inherent to it. I’m curious if you often consider that with these different languages.

I like that thought about how, when you’re speaking in another language, you’re actually physically changing. I think that’s very much a part of learning the language. You learn the language not just in your mouth and in your mind, but in your body. That’s very true. When I’m doing these imaginary language pieces, there are often a lot of gestures that I make to get me into the character that I’m portraying. If I’m doing the fisherman, for instance, my body language changes. If I’m doing the little old ladies talking to each other, my body language changes. In these imaginary language pieces, oftentimes, people will come up to me afterwards and say, “Were you speaking Chinese?” “Were you speaking German?” To them, they heard a certain flow of a language—not the syntax, but the melodic contours of a language, which is very much a part of it. When you’re creating dialogue in imaginary languages, you do get into this kind of variation of the flow of your voice.

In the performance on Wednesday, you were moving your body and moving your hands. Do you feel it’s important for the audience to be able to see these actions? Put another way, do you feel there’s something of this visual element lost when your work is recorded?

I don’t think there’s anything lost. I think there’s something gained when you see the work performed live because you get to see me and the physicality of what I put into the work. But the works that were created either for radio, a lot of them in Europe, or the works that I created purposefully for LP or CD, I consider them complete as they are. When I use them in concert as backing tracks, I’m adding another dimension to it. It’s not just the physicality that I’m adding, but I’m adding my composerly direction. I know the works, obviously, and I can present material that is about to happen, and then when the audience hears it happen again, in the backing track, they’re already familiar with it. I can introduce these things and play with them, and sometimes play against them. A lot of times, I work with the acoustic properties of the room. That is a big part of live performance: dealing with my voice in that particular circumstance, and really adjusting the work.

Are you able to speak specifically to the performance on Wednesday at Constellation? Were there specific things about that space, that venue, that atmosphere that caused you to change your performance?

It was nice to have the audience so close. Although I couldn’t really see because of the lighting, I could feel the audience really close to me, which gives me a very different feeling than when I’m in a very large concert hall and the audience is very far away. There’s that sort of intimacy. It’s an almost club-like atmosphere, which is very nice. I thought the sound was very good. The engineer who was dealing with the sound really blended my voice beautifully in with the textures that were part of the pieces that I used for backing tracks. I thought that was really clear. Sometimes the sound engineers will try to push my voice up on top, and I really like to be able to ride it so that I can come down into the texture and then come over it, and really play with it myself. I had great flexibility in that situation.

That’s what I really enjoyed about your set. Your first piece was solo, but in the last piece, it was really splendid because I couldn’t exactly tell when you were vocalizing and when I was hearing the backing track. I’m excited about anytime when I, as a listener, am forced to think about things happening in that way.

That’s good. I really like that. I like being able to get into the track and play with it, and sometimes introduce sounds that are not in the track. It’s not necessarily “confusion,” but I’m interested in the idea that the audience doesn’t quite know what I’m doing live and what is in the pre-recorded material.

There’s this sound poetry manifesto co-edited by Steve McCaffrey, a Canadian sound poet. He talks about the first era of sound poetry being the paleotechnic era, and how that includes children’s songs, nursery rhymes, skipping chants, and all these different cultural things that have specific melodic phrases. Were there things from your childhood that led you to be interested in this sort of experimental vocalizing?

I sang in church and I sang in school presentations. I don’t think I was experimenting as much. But I know in raising my son, when he was very young he was always singing. He would make up sound scores to what he was playing. I did a piece with him when he was about five months old called “Loose Tongues.” He didn’t sleep much during the night (laughter). One early morning, I put pillows out on the floor, suspended a microphone from the ceiling, and I just recorded a lot of his babbling, his baby talk. Then I went back and I interspersed this sort of motherese, sometimes imitating his sounds, sometimes initiating sounds, even though I already had his voice recorded. But I was playing with it. I had taken these sections of what he sang, what he created, and made them into modules and played with that. Although I’m sure he doesn’t remember doing that, as I don’t remember doing it, I am sure all children do this. They just make up language. It’s part of learning language—they try out sounds and if they get approval for certain sounds, they think, “Okay, better remember that one.” When they actually get to language, they begin actually trying out words, using them in context to see how particular words fit in, and whether they get the approval that they’re hoping for.

I’m curious if you ever thought about your own practice in relation to your children’s development of language.

Yeah, when my son was about three years old, he was at a concert that I was giving in Santa Fe. My husband was on one side of him, and the director I was working with on the other, and I came out with these sounds and then he came out with these sounds, and they were (look of disbelief) (laughter). To him, it was just our language. That’s more for me and Jacob, but you do hear children trying out sounds all the time, and kids are very flexible with their voices. Unfortunately, we civilize that away, as the kids grow up. We’re more supportive of the actual language than the imaginary language, which is too bad. But a lot of the sounds that I make will be like (makes a creaking noise), and people say, “Well, that’s the creaky door sound, I remember that.” In a way, I’ve gone back to exploring the instrument the way we do when we’re children, which is really fun.

How was the process for you of learning to use your voice in this way? What sort of things did you do to challenge yourself to expand what you could do with your voice?

It takes me back to the questions about language. When I was exploring the voice, I’d be working with poets and writers and reacting vocally to some of the things that they were reading. When Armand Schwerner, the poet, was reading from Milarepa, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, this sound came out of me that people have likened to Tibetan monk chanting. But what I was doing wasn’t like what they do, because they’re actually praying. They’re singing very low tones and because of what they’re singing and the vowel combinations, they’re getting overtones. I do an overtone technique, which is not like that, but with a multiphonic. I was recording a lot as I was experimenting, so I could go back and listen to what I had done and try to figure out some technique to replicate what I had improvised.

I’m thinking of your work with Kenneth Goldsmith, 73 Poems (1993), and the way in which the words in that composition have semantic meaning, but sometimes blur to the point where I’m appreciating it as more of a sonic experience. How important is it to you that people can attach these sounds to meaning? I’m thinking of the door sound you just mentioned. Do you try to avoid having 1:1 matches with your sounds?

I don’t consciously try to avoid it. They’re going to accept and experience the sounds based on their own experience, their own cultural experience, their own sonic awareness of things. I don’t necessarily shy away from certain sounds. In a real-time composition, like the first one on the program the other night, which is basically improvising while dealing with certain sonic gestures that are part of that piece that I play with, I’m just directing the sound to areas that are interesting to me at that particular point in time. I can’t really control what people are going to reflect on, or reference. When I started doing my solo concerts I was working with John Cage, and at a certain point he said, “Don’t worry if people laugh. It’s just that they’re not used to hearing these kinds of sounds in a concert situation. Just keep doing your work.” He was so very supportive of what I was doing.

I feel like laughter is actually sort of a wonderful experience. It’s a surprise, in this kind of setting. It’s rare that people are listening to music for the express purpose of laughing.

Yeah. There is something very wonderful about laughter. It’s joyous. I recall, as I was working on a project with Judy Chicago a number of years ago, called Prologue to The Book of Knowing … (and) of Overthrowing (1989), we were investigating creation myths from various cultures. We got into a Japanese story about laughter. There was a Goddess who got upset about something and went into a cave and took laughter and sunshine with her. There was a way of trying to bring her out again, to give laughter and sunshine back to the world. Being amused by what I do is fine, but laughing at it is a different kind of thing for sure. But the enjoyment of the sound—certainly I like that.

Are there any extremely negative responses you’ve had to your performances that still stick in your mind?

Not really. There was that early discomfort, if people would giggle when I made certain kinds of sounds. I had to get over that to focus on what I was doing, and pull their attention and focus into the fact that I was purposefully doing certain sounds. I wanted them to hear those sounds in perhaps a different way than they might have associations with. There was a lot of really purposeful focus on my part in the work that I was doing, and trying to bring the audience along with me into that kind of focus

Things you’ve done in your career sometimes feel like bringing a Trojan Horse of experimental music to the masses (laughter). Your voice has been in Sesame Street, Alien: Resurrection (1997), and Arrival (2016). How do you feel about your work being presented for a general audience in this way?

There’s a lot of answers to this question (laughter). With the Sesame Street thing, the object of having a human voice introducing the hand-signing alphabet to children who could hear was to bring them into this wonderful adventure, and to engage them with songs that were playful. There are multiple layers of recording. I would pronounce the letter, and then do playful treatments of each of the letters. I wanted to use the fluidity of the way the animation was morphing from one to another, with both the voice and with some of the electronic treatment that I was doing. It was very purposefully trying to engage the children in that.

I also did another film called Date with an Angel (1987). I was an angel voice (laughter). In that film, I replaced Emmanuelle Béart’s voice for the whole film. She was supposed to be this angel, this otherworldly creature who falls to earth. The sound designer told her that he wanted her to make an otherworldly sound, and all she could think to do was squeak. When they test-marketed the film, when she would open her mouth and squeak, the audience fell on the floor laughing. When they contacted me they said, “You’ve got to come and help us. We need this otherworldly voice.” In that particular case we recorded three different treatments of the whole film. One was more musical, one was quasi language, and one was more otherworldly—beastly. The sound designer could play with all of that. I think he mixed some eagles and other sounds into the mix too.

With Alien: Resurrection, again, they had recorded an actor, but he went too much in the monster direction. It just sounded like Godzilla. When they brought me in, I got to work with the director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. He told me, “We have a problem here. Yes, we know it’s a monster. But the monster is the clone of Ripley.” Actually, it’s a clone of Ripley’s clone (laughter). It’s part human and part alien queen. We have this combination, but the problem is, Ripley is going to actually take the saliva from the monster’s tongue and throw it against the window of the spaceship, and it burns a hole in the window and the monster is sucked out. So Ripley is committing infanticide. Ripley is killing her baby. He said, “The blend that we need is some human sounds but not so human that the audience reacts negatively against Ripley.” That was what I was dealing with, in trying to create this.

In all the work that I do with visuals, in Alien and the angel film, when I’m looking at the creature or the character, or the shape of the alien newborn’s face—this incredible thing in the back of its head that I imagined was a resonating thing, and the fact that it had this enormously long tongue, but didn’t really have lips—it led me to limit the kinds of sounds that I made for that creature. With the death scene, which is the big famous one, they had chopped it up into segments, feeling that it would be easier for me to record this in short five-second segments. I said, “No, no, no, I want to record that death scene in one straight tape, because that’s what’s happening to the creature at that time.” I just did it, inhaled and exhaled. That became the base track of that particular scene. I’m intrigued by the idea of creating voices for other characters. It’s as challenging—different but challenging—as creating a piece of music, but with a different end result in mind.

That must be interesting to be commissioned for a specific purpose, versus your own work which I assume is more open-ended and exploratory.

Absolutely. When I start a new piece, I mentioned that I do stream-of-consciousness writing, but I also draw. Not anything specific, but I try to draw energies. I just sort of let my mind wander using these gestures on paper, so that I can go back and try again, to see what I’m thinking about in developing the piece. I know a lot of composers will deal with architecture and structure. That’s part of what I get to eventually, but in the beginning of a piece, sometimes I’ll just sonically improvise and choose certain sounds that I want to place in the sonic terrain that I’m working with.

Is this drawing and wandering more of a passive process, or are you still very concentrated?

It’s not passive, it’s really purposeful. I know something about the piece, and I’m trying to let my mind wander into visual territory, into gestural territory, because that’s what I do with my voice. I also think that freeing your body to make physical gestures or to draw gives you more of a sense of how your subconscious is either ordering the sounds or wishing a flow to occur in some way.

I love thinking about and working through any work of art through other mediums. I’m a music critic but one of my favorite things is trying to understand an album in as many ways as possible, so I always try to play it in as many different contexts as possible. And in the last eight years, I’ve gotten really into fragrances. I love trying to find a specific perfume that pairs well with an album to help shape my understanding of both the perfume and the album.

That’s fascinating.

There’s something about incorporating more of your senses that forces a different understanding. The way people consume music can be very narrow. There’s always an infinite number of things one can take from a piece of art, and I always want to be expanding there.

I am very influenced by visual art. Sometimes I’ll stay a long time with a painting. Lots of times, I’ll look at the brushstrokes, the way the painter applied the paint, if the painter continually applied additional paint to get a kind of thickness or was very conscious of how the brush was moving the paint onto the canvas, and certain kinds of over-painting and then pulling away material that is exposed from previous layers. That kind of looking at painting is very much a part of what I think about when I’m doing sound.

You have one piece entitled ROTHKO (1986). Were there specific paintings of his you were considering for that?

That’s very much about the Rothko Chapel. It’s not about all Rothko paintings, although I did study a lot about how his work changed over the years. He mixed a lot of materials into the paint and created his own paint. I don’t know if you’ve seen those paintings in the Rothko Chapel, but you have to see them in person because they’re nothing like a photograph. From the color, from the texture, there’s almost nothing that a photograph can get except for the basics. The Rothko Chapel in Houston is an octagonal structure. Rothko created 14 canvases. He referred to the 14 Stations of the Cross even though he was Jewish. The paintings are different. As you sit in the Rothko Chapel—which is nondenominational, very purposefully—you sit there and just look at the paintings, you begin to see the painting sort of flow in a way. That’s what I was trying to capture. I was also trying to capture aspects of what’s referred to in Rothko as monochromatic. They are not ever single colors, they’re always multiples of a color. The ones in the Rothko Chapel are very dark. They’ve been called purple but they’re not purple. They’re more eggplant, if you will, but very dark. But there are many, many layers of paint. I think what’s happening with the eyes when you look at them is you begin to feel the layers of paint and color that go into making up those canvases.

How did that translate into you making that piece?

I recorded multiple layers of voice doing reinforced harmonics and multiphonics and, on the same pitch, bowed piano. Gaylord Mowrey, the pianist that I worked with for that piece, was really a bowed piano expert. As you’re pulling the bow against the string, depending on the pressure that you use, you either get the pure pitch of the string that you’re bowing or you get more metallic sounds, and also the overtones. That combination of the multiple voices and the multiple bowed pianos was my way of translating the darkness, the multiple layers of Rothko in these paintings. When I did it live with the backing track, in the Rothko Chapel, I had created eight separate mixes. There was a speaker in front of each of the eight sides. Sometimes the speaker was in front of multiple paintings, sometimes a single painting, but there were eight speakers, so eight separate mixes, and depending on where you were sitting you would get a different mix. So it wasn’t a single mix, but multiple mixes, which again reflected that experience in the chapel. When I froze it into something on the recording, I remixed it again, to try to give aspects of that sonic journey that one could take.

You said earlier that a photograph can’t capture the experience of seeing a painting in person. I’m curious, with having to remix that piece, it’s not going to capture that experience…

…in the space. What I tried to do, which I do with all my sound paintings, is to try to play with the stereo horizon, with foreground and background, and with focusing the listener to a specific aspect of what’s happening at any particular point in time. It’s constantly in motion, as far as the mix is concerned. I’m sort of drawing you in as a listener, and then directing you to listen to a particular thing at a particular point in time.

How important is it for you to make sure that your pieces are doing this sort of guiding?

It’s very important. What disturbs me greatly is that when we mix, we mix on beautiful speakers (laughter). So many people now are listening on earbuds, which do not in any way, shape, or form give you the whole range of experience. You’re missing out. It’s a snapshot of the experience of listening to it on beautiful speakers, which is the way it was really intended.

Have you been discouraged by the way technology has, in pursuit of convenience, prevented people from experiencing art in meaningful ways?

Yes, and I’m most disturbed when I have a student who mixes his sound with his computer speakers. I said, “You are not experiencing the sound. I encourage you to book a room at the school that has speakers and, better still, book a room in the recording studios in the school. You’re in school—take advantage of what you’ve got there!” (laughter). I told him, “You really have to experience the range of sounds and you’re missing it!” Also, what disturbs me is automation in mixing. It’s so easy now to set up something to happen and flow. But you’re missing, as a composer, the joy of actually shaping the sound and working with the mix and intentionally moving things from place to place rather than to let the machine or the algorithm do it.

Have you ever had to push back on specific things that existed at a live performance, or in your own practice, in terms of this automation, of not having control?

I mean, the problem is what I said. Once you release something, whether it’s on CD or vinyl or whatever, you lose control over how anybody experiences it. The best I can do is, when I’m in live performance, to make sure that the engineer that I’m working with understands what I want everyone to experience. I walk around and listen to how the sound exists in that particular space and encourage tweaking the sound in such a way that particular overtones will come out. They all love to roll off the bass (laughter). There’s something voluptuous about the bass, and as long as you don’t hit a tone where the room just expands and gives you feedback, it’s really important to play the sound in the room, to play to that sonic atmosphere. That is part of what the experience of live music is all about. Every hall is different.

Do you recall your first introduction to experimental music? Were there specific things related to sound that interested you?

I can remember when I was at Syracuse and I began to hear contemporary music. I really hadn’t heard much of it in high school. I was really intrigued with electronic sounds. I did get to experiment with a Moog synthesizer that had been purchased by the music department, but I really got interested in exploring and writing my reactions to various pieces that I was hearing. Luciano Berio certainly—the work with Cathy Berberian comes to mind—but I also remember listening to Milton Nascimento and being fascinated by the ways that other cultures were using the vocal instrument to explore. In other cultures, there’s so many, many, many, many different examples of how much the voice can do. I was intrigued by that as well.

Milton just had his final US tour, I was really sad he didn’t come to Chicago.

Where did he go?

I think it was just New York, Boston, and then a couple shows in California.

I’m so glad he’s still working. That’s fabulous.

As Americans, we sometimes perceive music from other cultures as experimental just because it’s foreign to us. Were you ever inspired by the use of voice in another culture for your own work?

Very much so. I did a lot of work with an Asian American dance company, Nai-Ni Chen Dance Company. They started out using my pre-existing music and creating choreography for that. Then they commissioned a piece and I said, “Well, I would really like to work with some Chinese instruments.” They took me to some rehearsals of The Chinese Music Ensemble of New York where I got to hear different instruments. There were certain instruments I was interested in, and there were certain players that they felt would be more amenable to working with a composer and not doing their traditional music. I worked with dizi, which are bamboo flutes, and erhu, which are silk-stringed instruments, yangqin, which is like a hammered dulcimer, and then a lot of percussion instruments that, in Chinese culture, are specifically used in opera and are not ever brought together. I said, “Well, I love that cymbal that goes (mimics the sound of small bending gongs used in Peking operas).” What I did was work with those instruments and mold them into one of my pieces, which was a combination of graphic notation and Western notation. I looked at the kinds of notation that they use, which was not at all useful to me or to them, because a lot of Chinese music is just unison but in different octaves. But they were very willing to try this, which was great.

I don’t necessarily work a lot with that kind of thing. I did study a little North Indian vocal music when I was teaching at CalArts, because I was curious. I learned Balinese monkey chant, because I was curious. Not that I was going to ever perform that, but just to understand what it felt like. Monkey chant is certainly very physical. North Indian vocal music is very specific. You learn different syllables that occur. But thinking back to Milton Nascimento, the first time that I heard Bill Withers, I think it was the song “Ain’t No Sunshine,” when he goes into this, “I know, I know, I know, I know, I know,” and he gets into the multiphonic, I thought, “Oh, my God, here it is.” I love his voice. There’s a warmth, there’s total honesty and exposure about his singing. I was just so delighted to hear that multiphonic sound come out in that. I love listening to people’s music, whatever it is. Certainly, I’m influenced, I’m turned on by different different kinds of uses, not just of the voice but of other instruments as well.

Are there other inspirations for your music that people might not be aware of or expect?

I talk a lot about influence from visual art. That’s very strong for me. But there’s also a work that I did in ’82 for a chamber ensemble called The Solar Wind (1982) that came from a paragraph description of the solar wind that I happened to see in a newspaper. It was describing the particles that flow from the Sun to the Earth. When there are explosions on the surface of the Sun, it accelerates those particles and it affects the magnetic field of Earth. That was the inspiration for this voice and chamber ensemble piece.

I’ve traveled a lot doing concert work. One time, in a sea coast town called Vlissingen, it was wintertime and the beach was so totally deserted. These jetties were jutting out into the sea and it looked very peaceful, but from time to time these huge oil tankers would come by very close to shore because there must have been a very deep channel there. I did a piece, Vlissingen Harbor (1982), for which I translated the experience of this peaceful, deserted beach in the wintertime, being drawn into the sea, looking at the jetties, and then these oil tankers coming along. I’ve done a lot of translating experiences over the years. And I’ve translated from paintings. Berliner Träume is my translation of my experience living in West Berlin, various things like that.

Did you like West Berlin?

I did. I love Berlin (laughter). The big Berlin. When I was living there, it was West Berlin so it was considerably smaller. I lived right in what was at that time the center, near the ZOB station, and very near the Gedächtniskirche, which was a bombed-out church that they left as a ruin. Gedächtniskirche means “remembering.” There was a festival called the Meta Music Festival. Walter Bachauer, the head of RIAS at that time, founded this festival that would mix world music and contemporary music. In every concert, there was some aspect of world music and some aspect of contemporary music. That was when I first encountered the Inuit throat singers. He brought in musicians from India and Africa and that cultural mix was really fascinating. He got the audience to experience both world music from all over and also contemporary music that they probably had not heard before.

At the end of the war, West Berlin was an island. There was the French sector, the American sector, the British sector, and the Russian sector. But people were leaving Berlin because it was a stressful place to live. It was becoming a city of all people. To get the young people to stay, they gave them all sorts of advantages. University was free. I want to say the Ford Foundation, but I’m not sure, but it was an American foundation that invested in Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD), which is the German academic exchange program. The Künstlerprogramm is the artists’ program. They brought artists to the city of West Berlin and gave us apartments, gave us a very generous stipend, and all the support for anything you wanted to do, within reason. All the visual artists wanted a show in the National Gallery (laughter), which was not always possible.

I got to do a lot of recording at Rias with wonderful recording engineers. ShadowSong and Klee Alee (1979) were recordings that were done there. I did a text sound festival, where we presented the parole in libertà by the Italian Futurists, the German Swiss Dada pieces, and more contemporary tech sound pieces. That was very important to me because I was able to explore alternative art and music history. I discovered that it’s not just what we think of as Western classical music, if you expand your thinking. I was also able to create pieces that were done in galleries, sound pieces, and concerts, things like that. The support for the arts was really extraordinary. At that time, I found out that the amount of money from the government to the City of West Berlin for the arts was five times that of the National Endowment. Just imagine (laughter).

That’s incredible. It’s clear you’re very curious, but also able to funnel this wide scope of experience into your own work. How do you feel like these experiences, making this music and composing with your voice, has changed your relationship with your body in general?

I think when I was starting, there was a lot of curiosity involved. When I began actually creating compositions, I had to believe in myself very strongly to put this music out there and to call it music. A lot of people wanted to call it just pure experimentation, but I was really adamant that it was music. For what I was doing, experimenting was part of the process, but what I was doing with that experimenting was creating pieces of music. I wanted people to empathize with the difficulty of creating some of these sounds and the difficulty of that whole process, but then to experience the result as music and to go with me on my journey. That’s what I was really working on and focusing on.

Do you feel like experimenting more and more with your voice throughout the decades has shaped the way you interact with the daily world, with people?

I think over the years I have become more confident in expressing my ideas and exploring, in taking advantage of the position that I have to make political statements. For instance, A Murmuration for Chibok (2016). When I got the commission for that work, Francisco Nũnez said, “We don’t want you to do an ordinary choral piece. We want you to do what you do with the voice.” So I said, “That’s fine. Then I have to come and do workshops with the kids.” He was delighted with that. Then he also told me that they are prepared to deal with difficult subject matter. He told me that part of what we’re doing is exploring life and having very difficult conversations. And so the commission came in 2015. The girls were kidnapped from Chibok in April 2014, and the whole world was engaged in trying to get these girls rescued. Michelle Obama, you know, “Bring Back Our Girls.” But a year later, there was not so much in the papers. It was my choice to try to keep this horrific event in the consciousness in whatever way I could. Over the years I have done some political pieces, using the advantage that I have of putting something out into the world and making a statement.

You mentioned Cage earlier, and I’m sure your husband Morton [Subotnick] has supported and encouraged you. What people in your life do you feel have really emboldened you and your practice?

I think of all of the composers that I worked with, I brought something to the experience, and I always wanted to help the composers that I worked with to realize the ideas that they had. With Alvin Lucier, Robert Ashley, David Behrman, and certainly with John Cage and Morton Subotnick, each of the composers had a particular aspect of what I was able to do that they were interested in. We would develop pieces together or I would help them realize their ideas. Similarly with Mort, he wrote a piece really early on called “Last Dream of the Beast.” He wanted to write an opera based on the Elephant Man but by the time he was ready to do it, there had already been the play and the movie. He felt that it had been done. But he incorporated some of those ideas into this piece that we did for the Los Angeles Olympics Arts Festival in 1984.

The Beast Woman became a character in that particular piece. It was called The Double Life of Amphibians. It still used this idea that he had of the Beast Man who had this elephantiasis, where the skull keeps growing. He had this image of the Beast Man imagining this Beast Woman, who was blind and armless, so she couldn’t see him or even touch him to feel how ugly he was. There’s this idea that if someone falls asleep and dies in a dream, then the dream becomes infinite. With the Elephant Man, his head had to be supported when he would lie down, or his neck would break from the weight. The idea was for the Elephant Man to imagine this beautiful Beast Woman and then purposefully fall asleep and die in the dream world, where the Beast Woman would be endlessly in his dreams. That was part of the piece.

I’ve always been fascinated working with different composers and I always learn something and I think they learn something from me. I bring something to that experience. For instance, I once wrote to Morty Feldman and asked him to write me a piece for voice and orchestra, something along the lines of The Viola in my Life (1970). He wrote back and said, “Well, do you have an orchestra who’s ready to play this? Because it’s a lot of work.” (laughter). He told me he had this other idea. About a year later, he sent me Three Voices (1982) using what was my vocal range at that time, and he didn’t have a metronome working on it. When I began to work with it I found the fastest moving figure, worked on that figure, got it up to a speed that I felt comfortable with, and then based the whole piece on that. With the exception of the words that come in midway, there’s no indication of what vowels to use. My contribution was to create this kind of blend that I thought I would be able to carry on for the length of the piece. I was recording it at CalArts but I had never gotten through the whole piece. I called him up and I said, “How long do you think this piece is going to be? I want to program it.” He said, “Hmmmm, 45.” But when I was recording the piece, I called him up again and said “Morty, it’s gonna be much longer, it’s more like 90.” And he said, “Yeah, I always thought it was gonna be 90.” (laughter).

For the first performances, and for several years when I performed it, it was the 90-minute version. That was the only version that he heard me perform. When he died, I wanted to make a lasting recording of it. I contacted Foster Reed at New Albion and told him I wanted to record this. He said, “How long is it?” I said, “It’s 90 minutes.” He said, “Well, where do you want to break it?” I didn’t know what he meant. You could only fit about 67 minutes on a CD at that point in time. I said, “No, I don’t want to break it. I want to learn to sing it faster.” I went back to that fastest moving figure, and just kept increasing the speed until I got it to a point where I thought I could withstand it. It came in about 47 minutes. So, who knows? Maybe he always imagined it being sung faster. But it’s equally good with this sort of slow snowstorm happening, the stillness of the snowstorm. It also works at this faster tempo, where the snow inside the glass globe is whirling around. It works both ways. I performed it for about 25 years, and finally, my voice got older. For several years, I moved some of the voices into the pre-recorded track so that I could keep performing it. But, for example, all the high As were in the recorded track (laughter). Eventually I had to turn down. My voice has obviously gotten deeper, maybe richer, but it is certainly not the kind of voice that he had initially written Three Voices for. But thank god, there are a lot of people now who’ve taken it up and do their own versions of it, which is great.

How do you feel about having experienced your voice changing over the years?

I’ve always had whatever the voice was that I had. When I was younger, obviously there was this whole upper terrain that I could play around with. As my body has changed, and my vocal cords have thickened, they’re not as flexible. You need much more flexible vocal folds to get those high pitches. I’ve adjusted to the voice that I have, and I create pieces now for the voice that I have. Like the other night, for example, “Erin” has a lot of material that I actually can’t sing anymore. I don’t have those high fluttery sounds, but I can introduce similar kinds of material that add another layer into that. It’s just dealing with the instrument that you’ve got.

Do you have any favorite memories with John Cage?

Oh, yes, lots of them. The one that comes to mind—well there’s two of them, or maybe three of them—I first met Cage when I was on tour with Steve Reich back in ’72 or ’73. We were traveling around Europe, Cage was concertizing with David Tudor, and we got to Berlin at the same time. There was a harpsichord performance in the Berlin Philharmonic Hall. In the lobby, there were various kinds of harpsichords and electric keyboards, there was an orchestra playing in one room, there were slide projections on the wall of the moon landing. Some of the keyboard players were standing around and talking, not playing. For instance, Cornelius Cardew was spouting off his political things (laughter).

It was so chaotic, so cacophonous, and it just upset me deeply. I knew what Cage looked like, I sought him out, and I marched up to him and said, “With all the chaos in the world, why do you make even more?” He was surrounded by his devotees, who gasped. I thought, “Well, I’m not going to be able to get an answer or talk to him.” There were thousands of people, and I went back. But he found me, amongst these thousands of people, and he tapped me on the shoulder. I turned around, and it was John, smiling beatifically. He said, “Perhaps when you go back out into the world, it won’t seem so chaotic anymore.” It didn’t change my mind about the piece at the time, but I was greatly impressed that he would find me in that melee and try to give me an answer.

Over the years, as I’ve worked with him, I found that that was part of who he was. People would come up to him in all sorts of circumstances to ask him questions, and he would always try to give a response. If it was something about one of his pieces, he’d say, “Do you have the score?” And he would always look and see if he had written enough information in the instructions so that a person should have been able to answer the question for themselves. If it wasn’t there, he would write it into their score.

A number of years after that, when I had started composing my own music, I saw him at a concert at Phill Niblock’s loft on Centre Street. I scribbled where I was going to be giving these concerts on a piece of paper and I walked up to him. I said, “I’m about to be doing some concerts of my music and I would like you to be there.” I handed him this piece of paper and he said, “Well, I certainly will try.” And he did show up at my performance of Voice Piece: One-Note Internal Resonance Investigation (1974). I remember it as a space that I think was on Lower Greene Street called Environ, but it could have been called something else. I was singing this very rigorous piece. I was focusing and concentrating so much that I had the sensation that I was leaving my body through the top of my head. I thought to myself, “John Cage is out there in the audience”—I could see him— “You’ve got to pull yourself together, get yourself back in this body and finish this.” (laughter). And after the performance, John came up to me and said, “That was just so marvelous. Would you like to work with me?” I said “sure” and he handed me the score to Solo For Voice 45 from Songbooks (1970), which is eighteen pages of aggregates and lots of decisions that you have to make. I don’t know if you know the Songbooks.

I’ve listened. I don’t know the scores.

It requires a lot of work, a lot of decision making. It’s the five lines but with floating clefs—a treble or an alto clef— and numbers above this five-line staff. Say there were 10 pitches on the five-line staff and you have a seven and a three, the first number referred to the number of pitches to be put in the top clef, whatever it may be, and the second number in the lower clef. Let’s say the top clef was the alto clef, and there was a seven, and then the bottom clef was the treble clef and there was a three. That would mean seven pitches in the alto clef and three in the treble clef, and then you make up a vocalese, and learn to sing it as fast as possible. Eighteen pages of this. It took me six months to do all the work that was required and to learn to sing it. I called him up and I said, “Okay John, I’m ready for you. Come hear me do this.” I was living in a loft on Upper Greene Street at that time—127 Greene Street—and he came over to my loft and I sang it for him. He said, “It’s very beautiful, it’s marvelous, but it’s not as fast as possible.” (laughter).

It literally took my breath away. Six months of work. I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I need it like birdsong, like calligraphic gestures. (La Barbara sings part of the piece). That’s ten pitches. He really meant it. I had to make the vocalese, figure out the shape of the vocalese, and then create it with my voice but in this calligraphic gestural sound. You’re not nailing each one of the pitches, but you’re getting the shape of all of this. He had been hired to do the La Rochelle Festival in France on July, 1976. The French were celebrating the American bicentennial. Why not? They got Cage to do this. He brought me to sing Solo for Voice 45. He brought Grete Sultan to do one piece, he brought two pianists to do Winter Music (1957), and then there was an orchestra to do Atlas Eclipticalis (1961).

He had determined by chance operations that this performance would have a duration of two hours and 40 minutes. It was the orchestra of The Hague in Holland. He had had trouble with this orchestra before. When we arrived, he gave a talk to the orchestra, to all of the musicians, about how what separates us from lower animals is that we as humans have the ability to take on a task and do it to the very best of our abilities. It was a beautiful talk. I thought, “Oh this is gonna be such a wonderful experience.” He had determined the positioning of the members of the orchestra by chance operations, so they were not anywhere near where they would ordinarily be. This was one of the hottest, driest summers in Europe. He had requested that two refrigerators be put in the wings. He said to the orchestra, “If you feel parched, and you have a long silence in your part, you can quietly leave the stage, get something cool to drink, and come back and take your place and continue.” This was just a license for the orchestra. The principal oboe player, according to chance operations, happened to be placed downstage center, right in front of the conductor—Richard Dufallo, who was conducting as a clock. The oboe player walked on stage carrying two bottles of wine, sat his oboe down in a stand, and proceeded to just drink for the two hours and 40 minutes (laughter). And he was offering drinks to members of the orchestra.

I would say 60% of the orchestra behaved very badly, talking to each other. Every once in a while, maybe they pick up an instrument and play something. Atlas Eclipticalis is actually a very difficult and complex piece to put together. I was asked by the conductor of the Manis Orchestra to help explain it to the orchestra. It is very much like what I had to do for Solo for Voice 45, where you choose pitches and then follow a gesture. Anyway, I would say about 30% of The Hague Orchestra tried to do what they were doing. I was very focused, I sang my part, and the two pianists playing Winter Music played their parts. At the end of the performance, Cage was just purple with rage. All of the French journalists, of course, were like bees to honey. They just attacked him with microphones. “Mr. Cage, what do you think?” When he got done with this interview, he came up to me and said, “You were just marvelous. You did your job, you focused, you did your work. I want you to know I’m with you always now.” That was a lifetime commitment.

The last story that I’ll tell you about Cage was when I was doing my John Cage at Summerstage concert. Cage had written a piece for the four of us: myself, William Winant who was a percussionist, Leonard Stein who played piano—and also played percussion on one piece and was Schoenberg’s last assistant—and Cage himself. It was the last performance that Cage participated in as a performer. This was July 23, 1992, I believe. It was a miserable day. It was July but it was pouring rain, and really cold. I called John up and said, “Don’t come up until it stops raining, because I’m not sure we can do this, with bringing the instruments out and everything.” Finally the clouds parted. I called him up and said, “Now we can do it.” We did this concert, it was wonderful. I had asked two video artists to record on video, so we have a video recording of the concert. Four6 was the work he had written for us. He said, “I’m going to do shocking things.” But basically what he did was sing. I don’t think he did anything particularly shocking, but he sang in his own beautiful voice, which I always told him sounded like a kind of drunken monk (laughter). As we were packing up to go away, I saw John and Merce [Cunningham] walking off laughing, talking. That was the last time I ever saw him. He died about two weeks later. A sudden stroke. But that commitment that he made— I never I never felt like I overstepped. Sometimes I would call him and ask him for suggestions or advice or something, and he would give me enough information to answer the question for myself, and to re-pose the question.

That’s beautiful. As an educator, I find that’s the ideal way to answer a question.

Yes. You can lead them, you can make suggestions, but you can’t do it for them. Asking questions is a really good way to get them to use their minds and think about things that are already there in their experience, and to get them to trust their own experiences.

That’s a great way of thinking about people in general. I am specifically tasked with teaching students at the remedial level, and I actually prefer that. It’s usually more joyful and fun.

Yeah. You can make it that way.

I want to teach content, but far more important to me is teaching them that they’re capable of accomplishing things in this science class. They come in thinking they’re dumb, because they’ve been told that. So much of it is just teaching them that they have skills they just don’t recognize.

Absolutely—just revealing the wonders that exist all around us. You may be teaching a specific subject, but I think the idea is to just make us aware of this incredible planet we live on, and the wonders that we’re learning every day, as that James Webb Telescope goes out. We’re having to rethink things that we thought were true.

I don’t have any further questions. Is there anything else you wanted to talk about?

I can’t think of anything at the moment. I’ve done so many interviews over the years. Philip Glass told me a long time ago, “After a while, you’ll just wind up giving the same interview.” I am determined never to give the same interview. I mean, I do have certain stories that I want you to have, but I really do try to reinvestigate the questions, and rethink them and hopefully come up with something that I have not thought of before.

Do you mind sharing one thing that you love about yourself?

My childlike sense of wonder and curiosity. There is a kind of playfulness that I’ve allowed myself to retain over the years. I’m not afraid to experience new things. In 2009, one of the economic downturns happened, and I decided to study acting. I was working with a composer and I looked across the street and I saw HB Studio. I said to him, “What’s HB Studio?” He said “Oh, it’s Herbert Berghof.” After we finished our recording, I walked across the street and signed up for lessons. Acting is sort of part of what I do, but I didn’t have the actual training. I had read books by Stanislavski trying to teach myself, but I had the courage to do that, and I did it for ten years—I did it through 2019. I was going to start teaching a course at HB Studio to actors on expanding their thinking about the human voice, but the COVID shutdown happened. I never have gotten back to that. A lot of what’s going on in their teaching is still being done remotely. They have some in person classes, but a lot of it is remote. I’m teaching more at the New School at this point. Maybe I’ll walk over to HB Studio again at some point. I think that’s the best answer. I love learning.

That’s what makes life exciting. There’s an infinite amount of things to learn. Do you feel like you’ve always been like this?

Yes. I was always very curious, very headstrong. very willful. If I get an idea in my mind, I keep going until I make it happen.

More information about Joan La Barbara’s life and work can be found at her website.

Thank you for reading the 107th issue of Tone Glow. There’s nothing greater than a life full of learning.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.