Film Show 045: Shu Lea Cheang

An interview with the Taiwanese American director about growing up in Taiwan, the sound design of Fresh Kill (1994), and rooming with Ang Lee.

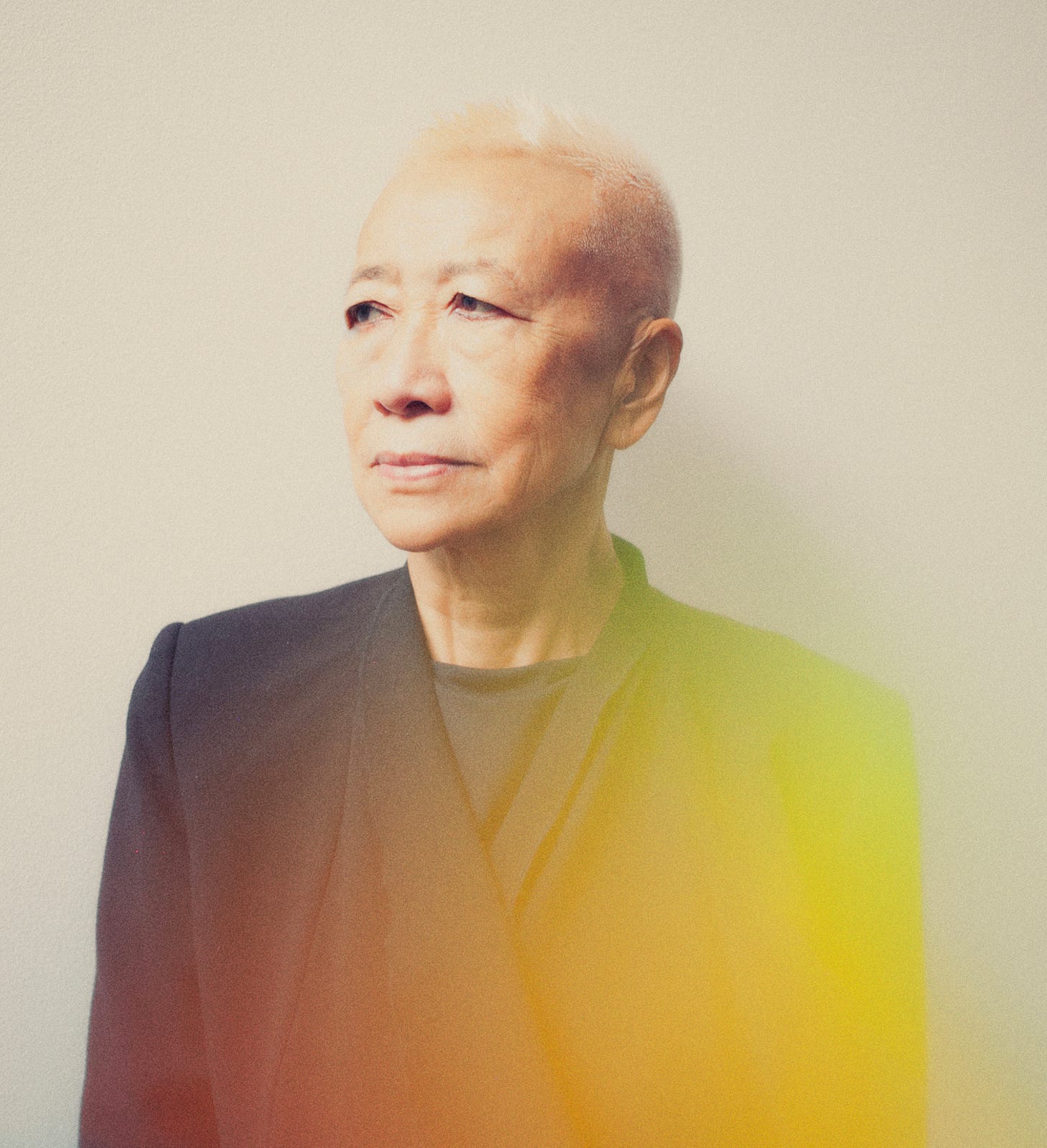

Shu Lea Cheang

Shu Lea Cheang (b. 1954) is a Taiwanese American artist and filmmaker who has spent her career creating works that grapple with media corporatization, racial and sexual politics, the internet, and more. After moving to New York in the late 1970s, Cheang became involved with various arts groups and, notably, played a key role in the important low-budget public access television program Paper Tiger TV. It was during this time that she gained hands-on experience with editing and creating works that involved different communities of people. Her monumental queer sci-fi debut, 1994’s Fresh Kill, has a newly restored 35mm print that she is currently touring around the US. Dates can be found below the interview. Joshua Minsoo Kim spoke with Cheang on Sunday, September 15th via Zoom to discuss her early video work, Tent City, and her lack of pessimism.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: How’s your day been?

Shu Lea Cheang: I just got to Pittsburgh and checked into this hotel, just in time for this interview! (laughter).

I wanted to start off by asking about your childhood in Taiwan. What comes to mind when you reflect on that?

I was born in the South of Taiwan and our place was quite close to the sea. Tainan is one of the more ancient cities, and it’s actually become quite popular—it supposedly has the best food in Taiwan now. When I was growing up, we always had relatives who went fishing and gave us fish, lobster, and shrimp. So in a way, my childhood had a lot of fish (laughter). And Fresh Kill (1994) is about fish.

And you have Sex Fish (1993) too!

Yeah! Sex Fish came in the middle of editing Fresh Kill.

Were there specific things you experienced in Taiwan that made you recognize that you wanted to be in the arts?

Not particularly. I didn’t set out to be an artist at all. By high school, I got really into cinema and that was during the time of martial law. Of course there were no films being shown, and I remember the only way I could see them was when, during high school, I went to the French Consulate or the Goethe-Institut and they’d show French avant-garde or German new wave films. I was really into Godard, so films like Breathless (1960), but I was also really into Fassbinder. At this time in Taiwan, there weren’t any particular filmmakers or a film industry, really, so my first contact with film was European cinema. There were Hollywood films shown too but I was never taken by them.

There’s a lot of time between when you first watched these films and then moved to New York. What were you up to in your 20s?

I got into National Taiwan University’s history department, but that wasn’t really what I wanted to do. After graduation, I picked up some freelance work and then I came to America because I wanted to study film.

How’d you end up in the history department?

National Taiwan University is the best university in Taiwan. I knew that I wanted to go into the humanities. I didn’t get into the English department and ended up in history, but it didn’t really matter; the university is really good and it was where I got into many things. There was a lot of music going on—it was a rock 'n' roll period, and there were some young Taiwanese bands playing in cafés. I became friends with them, and I remember one of the members of a band became a huge theater director.

How’d you decide to go to New York then? What inspired you to make that decision?

After university, I knew that if I wanted to study film, I’d have to get out of the country. At the time there was no film department in Taiwan. I came up around the same time as Ang Lee. When I went to New York, I studied at NYU and he was also there—we became very good friends. He had more of a theater background in Taiwan and by the time he went to NYU to study film, his filmmaking was leading him more towards working with Hollywood.

Do you have any specific memories of being at NYU?

There was both Ang Lee and Spike Lee, as well as Jim Jarmusch. We’d hang out together. I was living in the East Village and, at the time, it was very punk—there was all the no wave filmmaking. So I had this influence from them. I actually wasn’t a filmmaking major; I was a film studies major. That was kind of a mistake. But in cinema studies, I got introduced to New American Cinema, and at the time it was very experimental. I was into Stan Brakhage.

What was it like for you to be exposed to all these different scenes? You had experimental films, you had the no wave scene, and I know that you were engaging with the Wooster Group as well.

In a way, Fresh Kill is about that whole era—it wraps up my ’80s in New York. At the time, the East Village was really wasted. It was a rough time—there were all these empty lots. I ended up living on Bowery, which was the most famous street for homeless people. There was a Salvation Army there, and there were a lot of drunks there. And now Bowery has a 5-five star hotel (laughter). That’s how much New York has changed.

Did you feel out of place at all as an Asian woman in New York? Or did you feel welcome as one in the arts scene?

It was very clear that you would be experiencing racism. As an Asian woman, I was being exoticized, and this was a major factor in my installation, Those Fluttering Objects of Desire (1992). I tried to reverse this male gaze.

Right, Rea Tajiri is in that, for example.

Yes, she was in it as well as many other women. So yes, you feel racism and have these encounters for sure. I was involved with Paper Tiger TV and Deep Dish TV at the time. I also went into an editing place and worked as an editor. I started as an apprentice to be a film editor, and I was in the field for about 10 years. I was also taking up a lot of odd jobs in independent filmmaking—sound recording, doing boom.

I did want to ask about your work with Paper Tiger TV and Deep Dish TV. They started in the 1980s and were doing a lot of important independent work. What sort of things left an impact in having worked with those groups?

Paper Tiger TV was a weekly show, and it was on a volunteer basis so we kind of just got together at a studio in Manhattan and did all this stuff about media criticism. I was able to produce some of the shows too. For example, I produced a piece that was critiquing the Year of the Dragon (1985). I didn’t say that I produced it at the time because we were a collective, but it was my concept and I invited Renee Tajima to make a comment.

So it was all about being able to work on ideas together. I was a key member; I was on pretty much every show. I was also working with the camera switcher in the studio, and I was also editing. With Paper Tiger TV, there’d be one person who’d say something like, “I want to do a critique on the New York Times,” and then you’d come together around that. We produced these TV shows for basically nothing. We listed the costs and how much money we spent on buying paper or whatever. It was also a show where I was able to meet a lot of interesting, important scholars.

Earlier you said that it was a mistake to be majoring in cinema studies, but to me it seems like it lines up with your work in Paper Tiger TV. Why do you consider it a mistake?

Oh, it’s because I actually meant to apply for the filmmaking department (laughter). Ang Lee, Spike Lee, and Jim Jarmusch were all in the filmmaking department, and I was in cinema studies but I decided it was okay. I was still friends with all these guys. When Ang Lee was making his thesis film, I became his assistant director. We also shared an apartment together, so we were really close.

After I did cinema studies, which only took two years, I got a job at a commercial editing studio—I don’t even remember the name. At the time, commercials were done on 35mm so I learned how to edit on that. Of course we also used 16mm and Super 8 film at the time. I worked as an assistant editor for a year in this company and then I became freelance. That was a time when we were going from analog to digital editing. When I made Fresh Kill, it was shot on 35mm but I actually edited it on Avid, which was one of the first digital editing suites.

Do you have any stories about sharing an apartment with Ang Lee?

I did a wedding for him! You know his movie The Wedding Banquet (1993)? That actually came from a true story. We shared this loft in Chelsea. His parents were coming and he felt that he had to get married. He had this girlfriend at the time, and he thought, what’s the best way to entertain my parents? A wedding! (laughter). I actually organized the whole wedding at the loft, and he always appreciates that I did that. At the time we were poor, we didn’t have much money, but we were subletting these huge lots in Chelsea so we were able to do this huge party.

Did you organize parties in general while in New York?

Not so much parties, but a lot of my work was very collaborative, so I always organized a bunch of people together. Those Fluttering Objects of Desire had like 20 people, and there were a lot for Color Schemes (1989), which had 12 performers. We always had meetings at my place and I’d usually have to cook to feed people. That became the way I worked—bringing people together and eating together in a very affordable way.

Did you have a specific dish that you’d make?

I’m actually quite versatile. Right now I live in Paris and I also do these kinds of parties, and it ultimately depends on the ingredients. I had a friend named Lawrence Chua and at the time he was working at BOMB magazine. He did an interview with me. He came to me at the time as a punkish boy (laughter), but he loved to cook, and at my little loft in Bowery I had a good kitchen. Since he was working at BOMB, he’d meet so many artists and scholars and I’d let him organize things—we’d have ten people over and he’d cook in my kitchen. He’d cook so much.

I wanted to talk about Color Schemes. You’re framing the laundromat as a place for community. I’m wondering what memories you have of these spaces and what actually inspired you to make that work.

I don’t take home management seriously. I’m pretty bad with keeping the house clean, so every time I needed to do laundry, I needed to do three loads. I was also pretty bad at it. I never thought about separating the color clothes from the whites. It was a mess! The white shirts would always become pink—it would always happen! It took a long time for me to separate the two. And every time I did the laundry, I’d have three washing machines and just look at them turning around. Color Schemes is about this idea of the melting pot in America. If you go with this washing machine [framework], you see this separation of the whites from the colors, and how you can actually throw all the color clothes together. Color Schemes was also an installation.

In the ’80s, Hollywood was doing casting sessions and they would sometimes ask for “non-traditional casting.” And what that meant was that they wanted people of color. They would go out of their way to cast specific people in these roles. I was really annoyed by this phrase, “non-traditional casting.” I was working with La MaMa and other theaters in downtown Manhattan then, and Color Schemes came from wanting to work with some of the performers, and to consider how racial minorities would be lumped together.

At the time, I wasn’t setting out to be an artist, but I had this idea of putting a monitor in the washing machine and using a coin to have it turn around. Color Schemes was actually conceived as a three-channel installation with a monitor inside of the washing machine. I was lucky. Right from the beginning I got a New York State Council on the Arts grant, which meant I could work on the piece. I bought three used washing machines and put them in my apartment (laughter). They stayed with me for five years. Later I got discovered by the curator from the Whitney, John Hanhardt. He saw this and was bold enough to say, “You will have a solo show at the Whitney Museum. You’ll have a big room.” So I designed the room with all these different elements, and my first artist show with Color Schemes was in 1990. I remember that this was the year after Yoko Ono had her show there.

Do you have any thoughts on Yoko Ono?

I think she’s quite amazing. Her work with the Fluxus movement especially, and I like that she navigated being a celebrity while also being a part of that movement.

Those Fluttering Objects of Desire came a couple years after, and that involved more people. What sort of things did you learn from Color Schemes that informed your work on Fluttering Objects?

After Color Schemes, I was invited to do some shows at Exit Art on Broadway. I got a grant and decided to do Fluttering Objects. I was feeling repressed as a woman. I was always being objectified, but I didn’t feel like I could counter this situation without bringing more women together to do this piece. And that’s what happened with this. I designed a way to do this with a Polaroid camera and a Betacam. And I wanted the woman to hold the camera and to shoot it. I designed a way to do all this for cheap, and I guess today this is what we would call selfies (laughter).

Why did you decide to have it look like coin-operated porno booths?

I was working in Times Square then, and on 1600 Broadway was this building with film companies, so I was working there a lot. On Times Square, you’d walk around and see porno theaters and porno booths, and since Color Schemes was already using coin operation, I decided to do it the same way for Fluttering Objects.

I see a throughline between all your work with Paper Tiger TV and then these works, and then with Fresh Kill (1994). A lot of the things you care about are embedded in Fresh Kill—did you have everything laid out for how it would look and feel or did anything change throughout the course of making it?

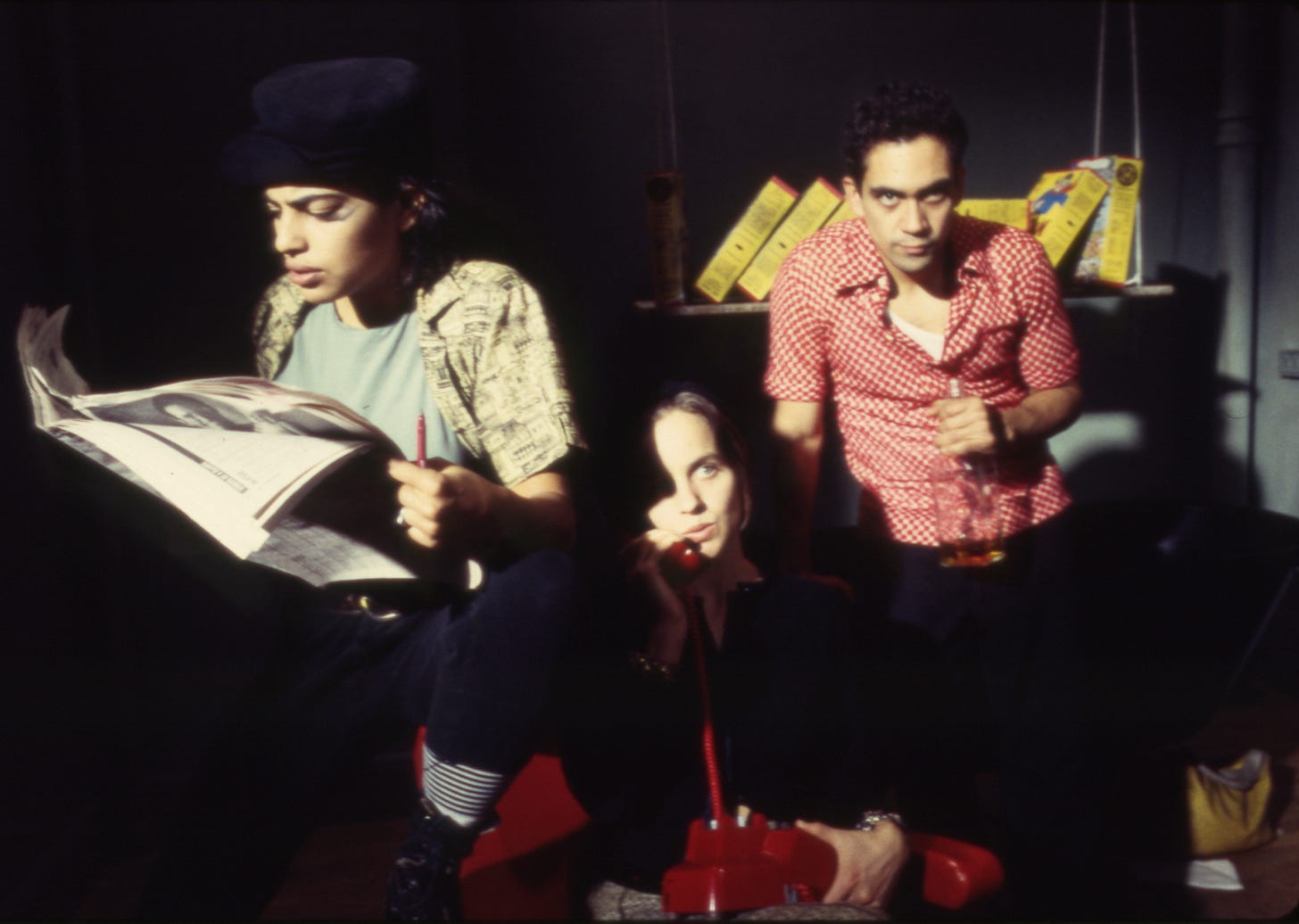

At the beginning of Fresh Kill, you have Tent City, which at the time was at Tompkins Square Park. The whole park had homeless people setting up their tents, and it was probably there for ten years. I think the year I started working on the film, the city actually got rid of Tent City, though I knew from the beginning that I’d want to build a set for this scene. Tent City in the East Village was a staple—it affected me a lot.

In Fresh Kill, you see the shadow of Paper Tiger TV as well because of the stuff with public access TV. Public access TV had a motto: “Use it or lose it.” For me, this is a very important concept. As an independent, alternative media maker—and in a larger society where corporations are taking over everything—public access channels were part of a deal with cable companies in each city. We had to say that they should reserve a couple channels for public use, for free. That’s what public access TV is about. You may have like 500 channels on cable and we would ask for two that could be free. There were also a lot of fights to continue using these two channels, so there was a lot of encouragement for artists to use them too. This included people like Richard Serra. He made Television Delivers People (1973).

We had to occupy these channels otherwise the government would take them away. There wasn’t fear about that; it was more like, we have to use this. And more artists started to use it. You had some crazy shows on there too. The technology was very rough but it was an interesting phenomenon.

I wanted to ask about the soundtrack and sound design for Fresh Kill. I appreciate how varied it is, and how much it plays an integral role in maintaining the pace and feel of the film.

I was familiar with sound because I was working as a sound editor at the time. And it’s true. We just had a couple screenings and I was sitting in the cinema and listening. At the time, we did Dolby SR, and it’s great to hear the different stereo sound with all these different layers; I forgot about that. I was pretty involved with the editing process and I wanted these multiple layers. I wanted this environmental ambience. And this for me defines New York. I’ve returned to New York recently and I was amazed by how noisy it was. So you have sounds that will take over everything in this upper layer, but underneath there’s so much nuance happening. And you can take this in social, political, racial terms. This is sound as a representation of the nuances of society.

Can you expand on that? Where do you see a relationship between the sound design and with racial politics or sexual politics?

There’s a radio soundtrack that’s pretty prominent, and then underneath you have this sort of ambient track. I was using the radio soundtrack to tell another layer of the story; it’s not only the dialogue that’s conveying the narrative, the radio and sounds are doing that too. This means that in our society, there isn’t just one voice that should take over everything. You have this mixture of voices, and maybe at one point you’ll have a voice that stands out, but that doesn’t mean you should be eliminating the other voices—they’re still there. This was why it was important for me to compose the sound with all these layers.

We approached Vernon Reid, who was in the band Living Colour at the time. We liked his music and I believe Jessica Hagedorn, the scriptwriter, knew him. He had never composed music for a movie before, so it was kind of funny because he did wall-to-wall music for the film. It’s such intelligent music with different genres. I can’t say that I directed him to use this specific music, but when he came to us with songs, I would accept them. He’s brilliant.

Something I appreciate about your works is its depiction of everyday intimacy and community. You have that in Fingers and Kisses (1995), which shows public displays of affection among Asian lesbians. What to you was meaningful in making that?

So Sex Fish was because I needed something fun to do because I was getting bored while editing Fresh Kill. Sex Bowl (1994) came from an installation I did for the Walker Art Center called Bowling Alley (1995). At the time, I had this museum work, but I didn’t think they’d accept work with sex, and so I made Sex Bowl for fun. That was done with New York lesbians. There was a loft party on Avenue D and we brought a camera and told all the lesbians that we wanted a picture of them. It was done in that way. None of these films were pre-planned, per se, we just did them. These films didn’t use money; friends just volunteered. They’d be like, “Okay, we’d be happy to do a sex scene,” and then we’d go to the bed and film.

After Fresh Kill, I had a residency in Tokyo. There, I was with the dyke community, and they showed Fresh Kill there too. Every day I’d hang out at Ni-Chome, which was the queer café, and it was there that I decided to make Fingers and Kisses. These films couldn’t have been made unless I was with these communities.

I’m thinking about your second film, I.K.U. (2000). I’m curious about your thoughts at the time around the promise of the internet in relation to queer expression and intimacy.

So before that, in 1998, I had this piece called Brandon for the Guggenheim. I “uploaded” Brandon Teena to the internet to explore gender, the virtual world, cyberbullying, and rape. After I finished Brandon, I felt that the internet was finished. With Fresh Kill in 1994, I learned about cyberspace and I was really eager to get on it, and there was this big commercial from MCI where they said, “There is no race and gender in cyberspace.” That was the promise of the internet: we would all be equal. Of course that wasn’t true. And in a way I made Brandon as a way to combat this idea. So after Brandon, I felt the internet was done, it was finished. The commercial companies were taking over the internet. The internet is a time bomb—you can’t search anything without being tracked.

Throughout the ’90s, a lot of internet artists like myself were trying to figure out how to make money. There was just no way to sell our work in this way, though at this time, porno sites were probably the only ones that were making huge money. People were finally ready to sign up and use their credit cards to keep watching pornos (laughter). So it was like, shit, these porno empires on the internet are collecting orgasm data, which is what I.K.U. was about. Last year, I also came out with the sequel to it called UKI (2023).

Have you been very pessimistic about the state of the world given everyone is on the internet or on their smartphones all the time? Like, people are being tracked constantly now.

Interestingly, when I did the Fresh Kill premiere at BAM earlier this year, the audience was cheering and shouting and were really in sync with the film. And then after two screenings of this current tour, the sense I’m getting is that people are finally catching up with it and it’s speaking to them. A lot of the post-screening conversations have been about us living in a corporatized world. I always recommend fighting within the system; my film is a way to make that resistance known. A lot of my work deals with living in a surveillance society, and at the same time, I wouldn’t say that I’m pessimistic because I don’t feel like I need to surrender. I always had to find a way out, and I’m still finding a way out today. I’m doing my part in this resistance.

There’s a question I always ask everyone at the end of each interview and I wanted to ask it to you. Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

Aww. These days, I tell people that I’m certifiably insane (laughter).

That’s what you love about yourself?

I have to accept it. I’ve been doing so many crazy projects and I keep doing them. I keep getting myself into trouble, and with this current road trip I feel a bit crazy. Even when I made Fresh Kill, there was a nickname for me on the set: “Maniac.” (laughter). I’m very persistent. Once I’m convinced of an idea, I try to realize it.

Tour Dates

Shu Lea Cheang is currently touring a newly restored 35mm print of Fresh Kill (1994). You can find all the dates below:

Sept 13 - Brattle Theatre (Cambridge, MA)

Sept 14 - Scribe Video Center@Ambler Theater (Ambler, PA)

Sept 15 - Pittsburgh Sound + Image @ Harris Theater (Pittsburgh, PA)

Sept 16 - Wexner Center for the Arts (Columbus, OH)

Sept 18 - Speed Art Museum (Louisville, KY)

Sept 19 - Athens Cine (Athens, GA)

Sept 20 – PATOIS @ The Broad Theatre (New Orleans, LA)

Sept 21 - Austin Film Society (Austin, TX)

Sept 22 - Circle Cinema (Tulsa, OK)

Sept 24 - Ragtag Cinema (Columbia, MO)

Sept 25 - Music Box Theatre (Chicago, IL)

Sept 28 - Marquee Arts (Ann Arbor, MI)

Sept 30 – Stray Cat Film Center (Kansas City, MO)

Oct 02 - Film Streams’ Ruth Sokolof Theatre (Omaha, NE)

Oct 05 - Guild Cinema (Albuquerque, NM)

Oct 06 – Southern Arizona Film Society @ Splinter Collective (Tucson, AZ)

Oct 09 - Grand Illusion Cinema (Seattle, WA)

Oct 10 - Hollywood Theatre (Portland, OR)

Oct 12 - Roxie (San Francisco, CA)

Oct 13 - Mezzanine @ Brain Dead Studios (Los Angeles, CA)

Oct 15 - Pollock Theatre, UC Santa Barbara (Santa Barbara, CA)

Thank you for reading the 45th issue of Film Show. Realize your ideas.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.