Film Show 026: Berlinale 2023, Part Two

Our second dispatch from this year's Berlinale, featuring 22 reviews of movies and installations by Claire Simon, Christian Petzold, Eduardo Williams, Lois Patiño, João Canijo, Safi Faye, and more

In our second and final dispatch from this year’s Berlinale, we look to some of the most critically acclaimed works from the festival (Claire Simon’s Our Body, Angela Schanelec’s Music), award winners (João Canijo’s Bad Living, Lois Patiño’s Samsara), hidden gems (Selma Doborac’s De Facto, Volker Koepp’s Leaving and Staying), and archival gems (Safi Faye’s I, Your Mother; Yvonne Rainer’s The Man Who Envied Women). Below, find reviews of 22 different films and installations that screened at the 73rd annual Berlin International Film Festival.

Our Body (Claire Simon, 2023)

Claire Simon’s latest documentary feature, Our Body, explores the intersections between healthcare as a technical practice and the intimacy of our embodied lives. It observes a series of patients in the obstetrics and gynecology wing of a French hospital as doctors guide them through their conditions and treatments. The camera places the audience in the room alongside them, imitating the perspective of someone standing a few feet away. The first patient is a 15-year-old seeking an abortion—her family has deeply misinformed her about the risks of the procedure. We met others, too: young trans men navigating medical transition and their opportunities for biological reproduction, couples having difficulties achieving pregnancy or who are in the birthing process, and older patients experiencing menopause or struggling with breast cancer. These cases cumulatively trace a cycle of life from puberty through death, and in each case, staff members help to demystify the functions of anatomy, surgery, and laboratory procedures such that both the patients and audience arrive at a more careful awareness of the joys and difficulties of “our” body.

The film profoundly underlines the importance of this understanding. A new mother is reduced to tears recounting the pain and anxiety she felt during a difficult birth. In detailing the process with a midwife, she is allowed to understand what was abnormal about her experience, eventually coming to terms with it. Just to be seen and validated in her experience is overwhelming. Moments like these swell into a moving account of the messy, painful, even violent experiences of the body, which are often inseparable from the ones we consider most loving and intimate. The harsh physical trauma of a C-section—startling to see so bluntly on camera—is immediately followed by a parent holding a child for the first time.

The level of attention and guidance these people receive is hard to fathom from an American context, where capitalist medical care is so obstructed and alienating that many people can rarely access care at all. For trans people in particular, a competent baseline of understanding and acceptance is often a fantasy in institutions that rarely even accept our genders and pronouns, let alone understand the reproductive complications of trans bodies. That the doctors here not only welcome their trans patients but display an expert understanding of how hormone replacement therapy interacts with reproduction and menopause could be taken as a utopian endorsement of socialized healthcare, but Simon wisely focuses on the experiences of the hospital’s patients and makes no direct political statements.

Our Body does briefly step outside the hospital near its end, showing people protest abuses of power and forced consent in gynecological care. Little context is given, and in one way the scene serves as an awkward asterisk about questions otherwise unaddressed, but it also echoes and underscores the film’s central idea: quality care can be immeasurably meaningful, but failure to provide it can be equally traumatic. Simon explores these themes from behind the camera through most of the film, but also learns it firsthand when, in the middle of its making, becomes a patient herself. Diagnosed with breast cancer, Simon pauses to gather her bearings before coming to a conclusion: “If this had happened before I began filming the hospital, I’d have been much more upset. When you understand and see others, it’s different.” Poetically, Simon’s own experience emphasizes her film’s lesson: technical knowledge is invaluable for emotionally processing our experiences. —Alex Fields

A Very Long Gif (Eduardo Williams, 2022)

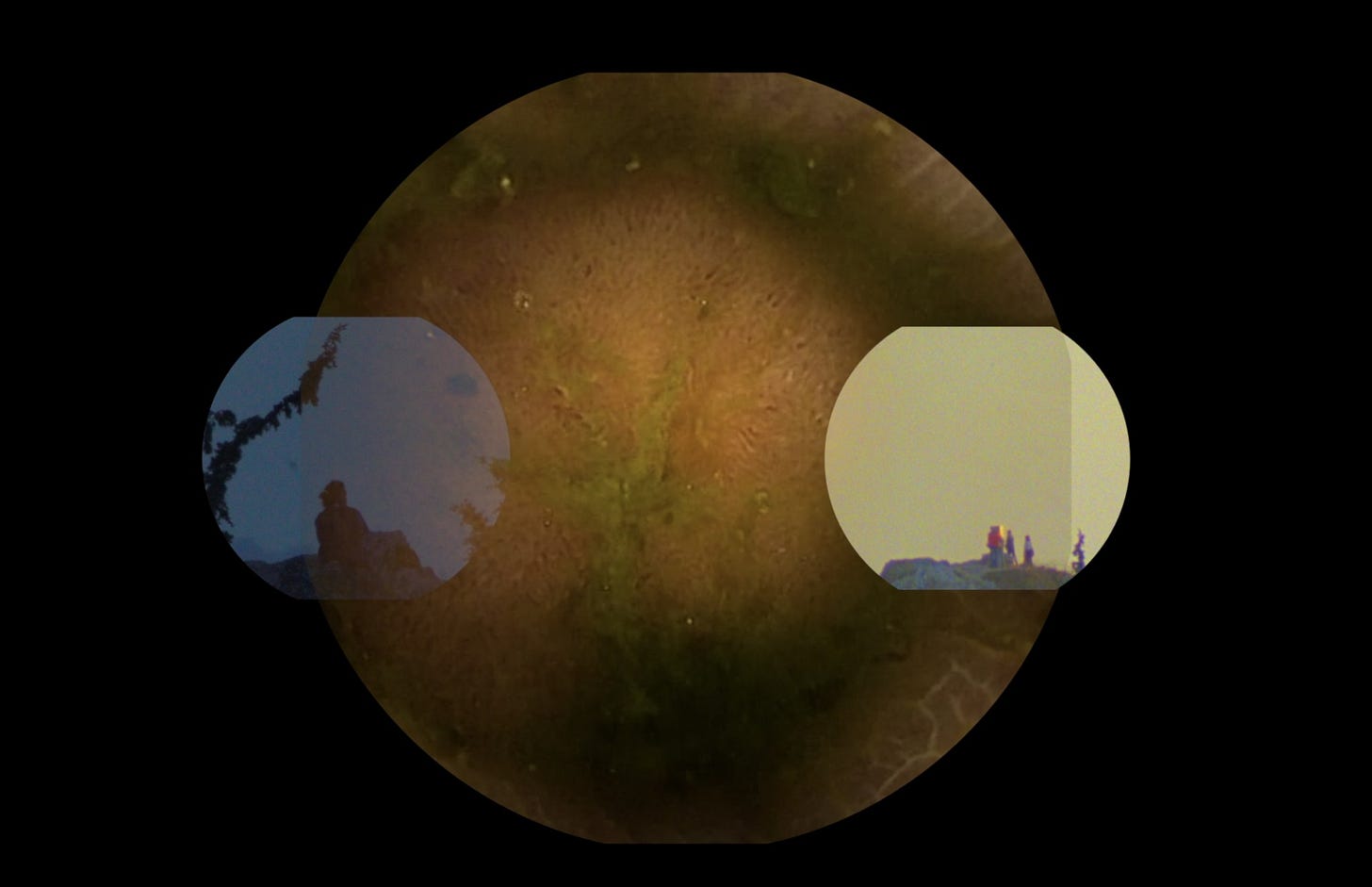

For an artist to describe their work as a .gif is to distinguish it from a film or an installation. While Eduardo Williams’ A Very Long Gif was presented at the Berlinale in the latter context, this specific label forces one to consider the bitmap image format and the way it operates. They’re not high quality, they don’t have any sound, and they usually last a few seconds. It’s immediately clear that A Very Long Gif isn’t really a .gif: it’s a three-channel piece featuring audio. Its central image is sourced from a capsule endoscopy camera—a pill-shaped device used to view one’s digestive tract. Williams is seen swallowing it, but the remainder of the 75-minute piece is focused on the beguiling images that arrive from its trek through his stomach and intestines.

In the context of Williams’ filmography, A Very Long Gif has the same exploratory spirit felt in The Human Surge’s handheld camera movements and circuitous structure. While there’s a similarly murky atmosphere, it’s shocking to views the various folds of a small intestine, or to see green and brown liquids arise, or to witness the beautiful yellows of foamy bubbles. As bile and digestive enzymes fill the center frame, unpredictable pulses feel like they’re operating in the tradition of the avant-garde. I thought of the rapid motions that occur in Teo Hernández’s films, and how here, the rhythms are just as impactful in their ability to jolt and transport you to a new location. That A Very Long Gif’s images are beholden to internal organs points to our body’s creative potential. There’s an indeterminacy here in both rhythm and place—a spirit of experimentation is literally inside of us.

Flanking the central image are two small circular frames depicting specific parts of a city. It’s lovingly captured with a telephoto lens and the contrast is obvious: Williams is aiming to reveal specific details of everyday life in two dramatically different fashions, and he occasionally toys with their presentation to show how they connect. Sometimes only one of these smaller images appear, overlaid on top of the central one. Sometimes they find the camera rapidly panning as bubbles throb in the center frame. Sometimes they appear in the shape of waxing and waning moons. Notably, .gifs do not have a way to fast forward or rewind—you must patiently sit through them. In spending time with A Very Long Gif, it becomes exceedingly clear that we’re experiencing the actual passage of time, noticing all the life that exists around and within us.

I anticipated Gif would end with Williams defecating into a toilet, the camera released into a porcelain bowl. I was pleasantly surprised, then, that he instead cuts to a single image of the sea. Without any of the smaller frames, Williams collapses the two visuals into a hypnotic swell of waters, visually linking the city and our bowels. It’s a fun and funny maneuver, which feels appropriate given this was part of an exhibition paying tribute to the late filmmaker Bruce Baillie. Are the flowers we occasionally see reminiscent of All My Life (1966)? Are the transformative superimpositions meant to resemble Castro Street (1966)? Is he just taking us along for a ride in the fashion of Commute (1995)? Whatever the case, there’s a unified sense of layering as meaning-making, and of turning the hidden into something visible. The film’s crucial third element of sound makes that clear. We hear normal chatter and someone covering Akon’s “Beautiful,” but also vibrant field recordings that deepen the images onscreen. There’s always more happening, Williams suggests, if you dig beyond the surface. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Afire (Christian Petzold, 2023)

Straying from the historical and mythological themes of his past films, Christian Petzold’s Afire details a weekend work trip that slowly looms into a literal and metaphorical catastrophe. The German director is as masterfully in control of his direction and writing as before, but leans into a tragicomic tone befitting our protagonist, the successful writer Leon (Thomas Schubert). He and Felix (Langston Uibel) are on their way to the latter’s vacation home in the woods to work on their respective projects—Leon is nearing a deadline for his second novel’s manuscript, while Felix is preparing a portfolio for an art school application. It’s noted that there are forest fires 30ish kilometers away from the house, laying ground to the film’s uneasy atmosphere.

Upon their arrival, Petzold introduces members of the ensemble cast through peculiar situations, each person fleshing out Leon’s complex interior world. Nadja (Paula Beer) awakens the two men after she’s heard having sex in the room next door; she’s here unexpectedly, and via Felix’s mother. Leon is enamored by her beauty, and he inspects her belongings, fumbles through conversations, and gets inexplicably defensive. The lifeguard Devid (Enno Trebs) is assumed to be her boyfriend, but this turns out to be a subtle misdirection. We see him leave Nadja’s room in the middle of the night, and he’s invited to dinner by Felix the following day—they eventually fall for one another. Petzold uses these initial encounters to impart what Leon sees and hears but doesn’t wholly grasp, and such partial understanding becomes a sly, recurring motif.

Leon’s narcissism is the source of whirlwinding emotions across Afire. Throughout the trip, he repeatedly mentions that he needs to work, but never actually does. Instead, he spends his time walking around, napping, and belittling others. Though he’s regularly dampening the mood, Nadja counters his snobby attitude and general unpleasantness with a happy-go-lucky spirit. Everything shifts, however, when it’s revealed that she’s working on her PhD in literary writing. Leon is dumbfounded and quickly changes his perception of her. There’s a similar oscillation in tone in Afire—between drama and comedy—that offers insight into his reckoning with his insecurities.

After Leon completes his manuscript, which is amusingly titled Club Sandwich, his publisher Helmut (Matthias Brandt) arrives only to deem it a failure. Leon’s life starts to spiral out of control, and so too does a nearby fire. It soon destroys the entire forest before burning out, doubling as a symbol for Leon’s fading desire for Nadja. After she confronts him about this, the film ends in typical Petzold fashion: while transformed by the events that have transpired, the two are in a standstill, caught at the intersection of love and loss. —Michael Granados

Bad Living / Living Bad (João Canijo, 2023)

This year, João Canijo was invited to the Berlinale with two films—Bad Living (Mal Viver) and Living Bad (Viver Mal); the former playing in Competition, the latter in Encounters—both set in the world of a small family-run, high-end hotel. Bad Living throws us right into the drama. The hotel is managed by the matriarch Sara (Rita Blanco) with the assistance of her two daughters, Raquel (Cleia Almeida) and Piedade (Anabel Moreira), as well as the chef Ângela (Vera Barreto). Due to missing profits, Sara plans to sell the hotel with little consideration for where this would leave Piedade, who is dependent on the routine and role she has constructed for herself within the cosmos of the hotel. This interpersonal tension grows even more after Sara brings in Salomé (Madalena Almeida), Piedade’s estranged daughter, whose father has recently passed away after a long illness.

Starring many of Canijo’s long-time collaborators, Bad Living mostly revolves around Salomé and Piedade’s relationship, each one expressing their feelings with an unguarded directness. “Everything is so difficult, isn’t it?” Piedade confides in her daughter. “For you it is,” Salomé cooly contextualizes. Piedade is at once described as “neurotic”, “depressed,” and “bi-polar,” and Moreira plays her with a detached austerity which hides her wide-eyed anxiousness. The relationships in Bad Living / Living Bad spread and reverberate through the family tree, and each one is intimate in its portrayal but epic in scope, built on a series of betrayals, misgivings and bereavements. The daughters tend to lose themselves in these interpersonal histories, while the mothers flip through them with a decisive emotional pragmatism.

The hotel is realized as an intersection between private and public space. The overlapping dialogue during the dinner scenes switches between personal conversations and Piedade and Raquel’s introductions of the wine list. The couch in the lounge, which in Living Bad becomes a place of quiet but definitive confrontations between the guests, is the only place Salomé and Piedade allow themselves to come together. There’s a tense scene between them—captured in a wonderfully patient long take—where the daughter is cuddled into the mother’s lap. It’s absent of any easy reconciliation—the mother spends the time playing along to Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?—but it’s nevertheless hopeful.

Visually, Canijo and DP Leonor Teles intentionally distance us from the drama, playing it out in master shots and compositions that communicate the depths of these relationships through several layers of reflective glass, mirrors and calibrated blocking. Canijo has revealed in interviews that he used to visit the hotel himself as a child, which gives the surroundings an added layer of familiarity. Yet for me, the cinematography never pushes beyond a tactful, festival-ready aesthetic which is easy to appreciate and pleasurable to watch, but flattens the actual drama into easy emotional accentuations of non-communication and spatial isolation. Disruption has never felt this smooth before.

Living Bad applies the same visual strategies but is helped along by its anthology format. Here, Canijo loosely adapts three Strindberg plays, which focus on the relationships of the guests in the hotel, each one being disrupted by variations of the mother figure. Canijo is good in writing stock narrative dynamics, whose flatness the compositions here can actually fill out with some depth. While all of these stories have a definite shape, none of them are necessarily resolved nor do they need to be. There is something about working within the very strict confines of genre, one in which each character is assigned a single role and trajectory, that just clicks when put into a formally dense structure as here. —Florian Weigl

Aufenthaltserlaubnis (Antonio Skármeta, 1978) / I, Your Mother (Safi Faye, 1980)

The third program in the Berlinale Forum’s Fiktionsbescheinigung series brought together two films dealing with immigration to and from West Berlin in the late 1970s and early 1980s—a time rife with the highs of reunion, the frustrations of separation, and the ridiculous toils of bureaucracy. The first, Aufenthaltserlaubnis (roughly: Residence Permit), is an effervescent short of about twelve minutes, containing all the unbridled, multicultural optimism of Paul Simon’s “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes.”

The Chilean director, Antonio Skarmeta, achieved fame in his lifetime primarily as a novelist, and his 1985 novel Ardiente Paciencia was adapted by Michael Radford in the critically acclaimed Il Postino (1994). As that novel concerns the 1973 coup d’etat which installed Augusto Pinochet in Skarmeta’s home country, Aufenthaltserlaubnis celebrates the other dictatorships of the world coming to an end during that same decade. The execution can at first appear naive, if nonetheless infectious: the film opens with a children’s trio performing “Heart and Soul”; later, Greeks teach an international group the syrtaki alongside a chorus of kazoos. In short order, refugees from Idi Amin’s Uganda, Salazar’s Portugal, Ioannidis’ Greece, and Franco’s Spain lampoon enormous caricatures of their recently fallen dictators, and wildly celebrate their long-awaited returns from exile in Berlin. But as Skarmeta’s narration reminds us, Pinochet continued to reign in 1978—the Spanish and Portuguese had to wait forty years for their day of return. With this difficult truth amended to the record, Aufenthaltserlaubnis’ drunken optimism appears less a celebration and more a survival tactic, vital and heartfelt all the same.

Man Sa Yay (I, Your Mother), formed the 59 minutes of the program’s back half. Directed by the late Safi Faye, this film adheres closer to convention than some of her other documentary work. Still, Faye’s matter-of-fact sensibility pulls from an eclectic set of experiences for the African immigrant community living in West Berlin in 1980, striking us from unexpected angles. As indicated by the title, the film is largely structured around epistolary correspondences addressed from her mother and family to Moussa, a young Senegalese man studying at the Technische Universität in Berlin. Patterns emerge in these letters, like the comical grocery lists of European goods they request to be sent to Senegal (“I will trace you a picture of my feet, so you know what size I am,” Moussa’s sister writes him), or the perpetually downplayed but never unmentioned fact that Moussa is dearly, dearly missed.

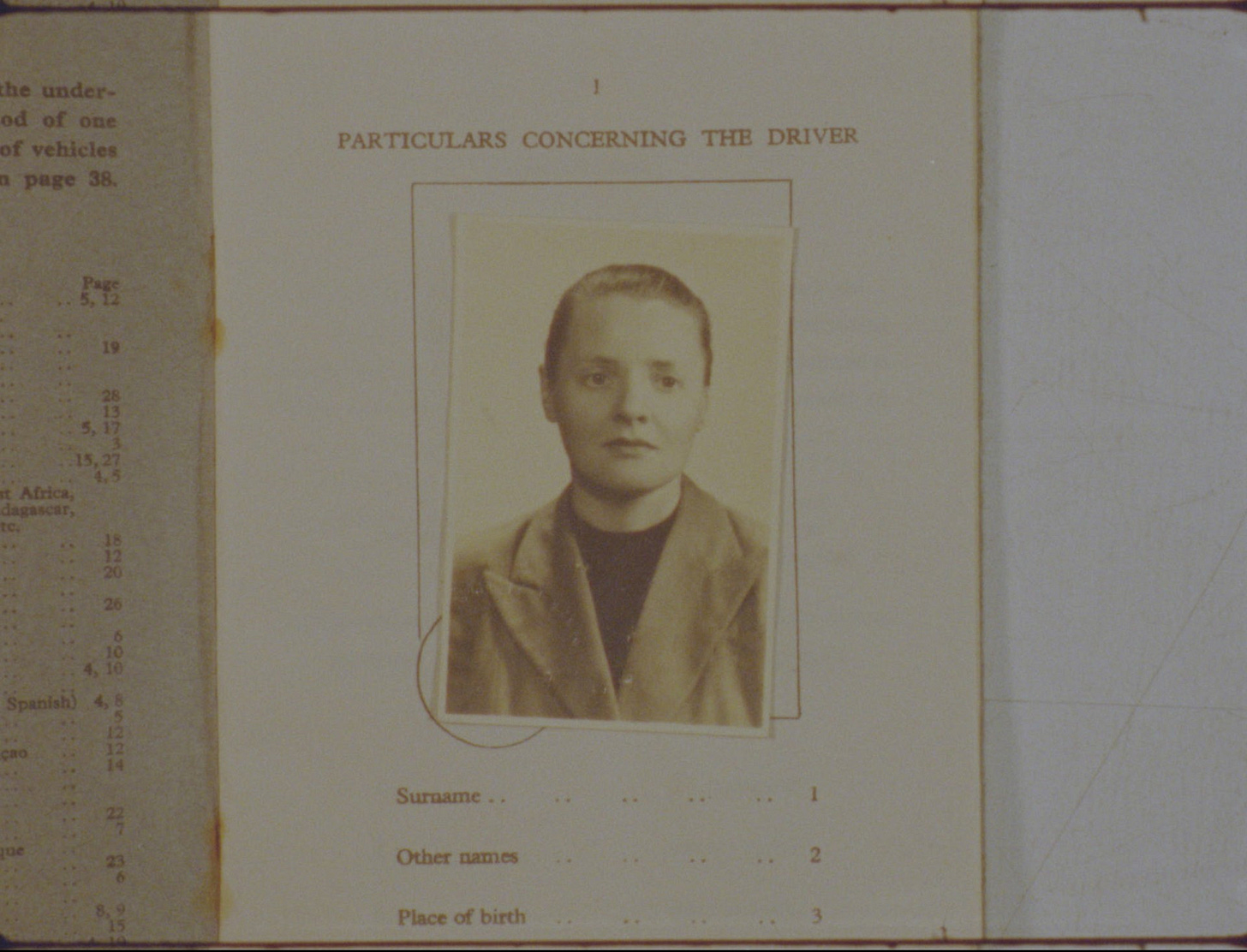

Faye explores other facets of the lives of West Africans in Berlin, observing the sidewalk sale of sculptures and handmade tchotchkes to Germans for pitiful sums, or sitting in with a group of Moussa’s friends grabbing coffee on a patio, laughing and commiserating about the various aggressions and microaggressions that fill their days. In its groundedness, Faye’s film offers a flipside to the flights of fancy indulged by Skarmeta’s, but the films are united in their weary understanding of displacement as a long-haul experience, expressed through the trudge of bureaucratic imagery that has become a daily fact of life for these immigrants: P.O. boxes, scheduled meetings with officials, postage and passport stamps. There are three things that appear permanent in these films: displacement, bureaucracy, and the hope for reunion, which is perpetually out of reach until it isn’t. —Dylan Adamson

Cidade Rabat (Susana Nobre, 2023)

Cidade Rabat observes Helena (Raquel Castro) through the quiet moments of her life: waking up with her lover, driving her daughter to see her father, and visiting a doctor after finding a lump on her butt. It seems as though Helena has been an observer of her own life for a long time. The images captured of her daily routines are overwhelmed by stillness and an underlying sense of dread. At the age of 40, she’s avoided making too many decisions or major changes, and now that they’re piling up after the death of her mother, there is a lot to confront. What should she do with her mother’s house and all her belongings? How can she continue to deal with the cold administrative tasks her job entails? How can she connect with her community in a meaningful way? She’s desperate to break free from her former ways.

With Cidade Rabat, director Susana Nobre has articulated the feeling I get when I picture my life as I age. Though it is not exclusive to women, there is a sense of fear that we’ll one day (if we haven’t already) become stuck—in motherhood, in an unrewarding job, in the same place we’ve always been. Thankfully, Nobre seems to have overcome this malaise herself, and writes Helena as a woman who knows the life she is entitled to; she’s ready, finally, to fight for it. The film comes close to exploring political ideas, specifically related to labor and the mixed-raced Reboleira neighborhood in Lisbon where the film is set (a place where Nobre has worked in the past), but there’s not much beyond a general sense of inequality. Still, I’m left feeling gratitude for this gentle story: it’s peaceful, encouraging, and honest. —Becca Rieckmann

Calls from Moscow (Luis Alejandro Yero, 2023)

It takes a while—because this is a film about “takes a while”—but minutes before ending, the word waiting enters Luise Alejandro Yero’s Calls From Moscow (Llamadas desde Moscú). It’s a relief to remember the word’s existence, realizing that it’s this honeyed, frozen sensation. It saturates the Cuban filmmaker’s debut feature, which occupies the curious space between fiction and nonfiction, or rather, being known and being watched. When the subject looks into the distance—just past the camera—to say, “Are you recording me?” I don’t think fiction or nonfiction are useful words anymore.

Eldis and Juan Carlos and Daryl and Dariel (the names of the actors, the names of the characters) live in Moscow. They live there for now, having left their home, Cuba. The four men never share the frame together, instead finding camaraderie portaling out of Moscow’s winter through smartphone screens and the sounds inside headphones. These acts are a coping mechanism, sure: when the bleakness outside lines up with the bleakness inside, a call is somehow the only thing that helps. Pettily, perfectly, musically, absurdly—we transmit each other, even at our most alienated.

The calls are all they are, sometimes. A war begins. Work stalls. Eyes begin to look tired. Eyes look, tired. They make movies. They phone family, boyfriends, the filmmaker Luis. They watch each other on TikTok and recreate poses, lip sync, and shake it. The same couch holds different bodies but not at the same time. Maybe a red coat does too. This is, I think, all one day. It’s at least the feeling of one day.

Maybe waiting is an inherently experimental period: to stand in a hallway, to learn a new language haphazardly, to say you’ll return home, to put something off or to have to talk to someone putting something off—all these things require a body to feel time differently. Calls From Moscow experiments with the way we wait on the image. And for all its melancholy, there is some kind of resonance to maintaining, even in this stretched-too-thin way. While we wait, bored or bleary, we send text messages and bombed-out looks into the world. We make 65-minute films about waiting around. All of these gestures are dispatches. And if there is a beloved (even a frustrating beloved) on the other end, there is some kind of life after love, after life, after. —Frank Falisi

About Thirty (Martín Shanly, 2023)

“March 2020. Possibly the worst day of my life.” About Thirty opens with our narrator, Arturo (played by director Martín Shanly), uttering these words as he flips open a journal to a page filled with scribbles and drawings. We then see him light a cigarette on the side of a street, and the camera zooms out to reveal his surroundings as he paces back and forth—he takes three puffs. As the camera begins to focus on a wedding that’s about to begin, he disappears into the background as guests shuffle into the venue. After the ceremony, About Thirty jumps between April 2017 and March 2020—the month COVID-19 was declared a pandemic. These time-skips are unceremonious and paced effectively, serving a multitude of purposes: they deepen Arturo’s reflection of a friendship gone stale, they introduce additional contexts to build layers to the people he knows, and they feel like flipping through the aforementioned diary.

Shanly’s portrayal of Arturo is striking, and is largely complementary to Shanly’s direction. The scenes from the wedding reception are a particular standout, as they depict Arturo’s emotional state with great care. When he arrives at the wedding reception, he’s nowhere to be found on the guest list, and he deftly conveys polite exasperation at such disbelief. In a moment of adrenaline, though, he breaks into the building through a window, wading through the event both nonchalantly and triumphantly. Such joys are quickly dampened, however, when he later spots his ex-boyfriend. It’s here that we understand that there’s no reprieve from having to confront your emotions, and in an inebriated state, Arturo confesses that he still has feelings for this former lover before being gently rejected. These highs and lows are palpable.

Watching About Thirty back-to-back with Shanly’s earlier work, About Twelve, I couldn’t help but fixate on how both of the film’s protagonists are struggling to belong, their loneliness only magnified by the fact that they’re surrounded by others. The final sequence of About Thirty focuses on Arturo living alone during April 2020, shopping for groceries and working as an English tutor from home. The last shot contrasts nicely with the film’s opening shot: Arturo takes a drag of a cigarette on his balcony as the camera patiently zooms out to reveal that he occupies just a tiny corner within a much larger residential building, which is in turn shoulder-to-shoulder with other dense dwellings. The slow pullback gives us a moment to assess how we’re doing in our own personal lives while allowing us to revel in the quietude of Arturo’s life, now absent of the bustling menagerie of social interactions that took up so much emotional space pre-pandemic. —Tiffany Kwak

The Klezmer Project (Leandro Koch & Paloma Schachmann, 2023)

The Klezmer Project is, on its face, the story of a lie. Leandro, a “mediocre cameraman” (played by co-director Leandro Koch) spends his days shooting wedding videos amongst the Argentine Jewish diaspora. At a gig, he meets Paloma (co-director Paloma Schachmann), the clarinetist of a klezmer band performing traditional music at the ceremony and reception, as is custom for Jewish weddings around the world. Hoping to impress Paloma, Leandro falsely claims that he is making a documentary on klezmer music. Paloma asks to see his footage for her doctoral research and, in the process of hiding his lie, Leandro makes a documentary on the subject, which very well may be the movie you’re watching.

Arthouse has long-mined this territory: the blurry boundary between the personal subject and the objective lens, family and history, contrivance and realism. Where The Klezmer Project stands out is how skillfully Koch and Schachmann braid these old themes into an exciting movie via their camerawork and editing. Borrowing liberally from documentary style and composition, it can often be hard to tell just what kind of scene you’re watching, whether a given character is acting or simply being interviewed, and whether the narrative devices the writer-directors engage in are framing the story or actively influencing its events. Is the apocryphal tale of Yankel the Gravedigger the true frame of the story, or is it only Paloma’s understanding of her and Leandro’s romance?

If you don’t know much about klezmer, then you’re not much different from Leandro at the start of the film. (And the fictional Leandro’s fictional Austrian financiers would argue that you’re no more enlightened by the end of it.) The Klezmer Project takes on a comedic bent as Leandro travels to Vienna and acquires a producer for his fake movie, and he becomes increasingly aggrieved as Leandro hijacks the production to chase Paloma across the Caucasus. Along the way, they find no Jews, only their absence and the memory of klezmer played by gentile folk musicians. It’s in this place, somewhere between Romania and Moldova, where the movie executes its greatest feat, interpretable only when you realize that the Yiddish root of the term “klezmer” makes no reference to any rhythm or melody, but instead conflates the player and his instrument: an immanent creative act mirrored by the film itself. —b/bm

Between Revolutions (Vlad Petri, 2023)

Vlad Petri’s Between Revolutions concerns Zahra and Maria, two unseen women, who correspond by voiceover in an epistolary narrative. One is from Romania, and the other is an Iranian exchange student there. With little more than voices recorded over montage, Vlad Petri imagines the unique cross-cultural circumstances of such a friendship, one whose optimism and intimacy were too sweet to last. With watchful eyes trained on the Secret Police, each narrator laments the secondary status they experience as women, from which their brief time together in Romania was a merciful reprieve. Throughout, there are hints of underlying sapphism, but this too is left cryptic, another private longing in the secret histories of women.

We are told that Zahra returns to Iran in 1978, just before her own revolution, leaving the girls to discuss changing circumstances in their home countries. Zahra tells Maria of her work writing manifestos with her father, trying to write as simply and clearly as possible. Her efforts are mirrored in montage, where Iranian crowds can be heard chanting, “Workers, peasants, and the oppressed will be united to exterminate exploitation.” Despite clear sympathies, there is no unified demand being made by the left. Every radical slogan seems to arrive bearing its opposite: at one point a banner can be glimpsed displaying the words “Not Communism Nor Capitalism Just Islam—” (the rest is illegible from a distance). Another reads, “Down with USA, USSR — Down with Israel,” in the totalizing manner of someone sick of it all and seeking something new.

For all the radical energy, we are reminded that mass mobilizations contain all elements, that a revolution is as much an internal struggle for power as it is a rebellion against established forces above it. Imam Khomeini, icon for inchoate hopes and contradictory desires, emerges as the figure around whom everyone rallies in this unsettled moment. But his potency as a symbol for change becomes harnessed to both progressive and reactionary ends. One shot follows a group of women denouncing the conservatives, followed by a male crowd railing against women who don’t wear the hijab. Petri himself isn’t undecided, as he shows a feminist consciousness of women’s status in pre-Revolution Iran; a late textual citation of Forugh Farrokhzad is one of his subtler expressions of sympathy. Imperialism may be the unifying enemy, as is the Shah who symbolizes it, but the form of what will take their place remains contested.

Dreams of a better future curdle into parody when symbols of freedom pop up in Maria’s post-Communist Romania: the US flag, American-made jeeps, Pepsi handed out to the joyous masses. Petri’s sequencing highlights the irony without overplaying it, as these images are, after all, documents of real events. The elegiac tone here is reminiscent of Chris Marker and Alexander Sokurov in its retrospective analysis of a failed present. But there are also times when Between Revolutions most resembles The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu (2010), a three-hour film compiled by Andrei Ujicā from over 1000 hours of archival footage. Ujicā’s work feels like a glimpse into Ceausescu’s psyche the moment before death, a remembrance as he would see fit to construct it: revolutionary hero, noble statesman, beloved leader of great nation. Between Revolutions draws on documentary images of Romania to construct its own historical fiction, but from pointedly different angles. It is the ground-level document to Ujicā’s top-down diary of decay, subjectivity and artistic process returned to the people betrayed by Ceascescu.

As the two revolutions devolve into disappointment, Maria starts losing touch with Zahra and, correspondingly, the optimism they once shared, now lost to time. A documentary post-script makes tangible what was only implied at the beginning: we’re shown work-study permits of Iranian women admitted entry into the Socialist Republic of Romania, and Petri notes that these fictional correspondences were based on letters held by the Secret Police. This final montage of faces indicates there are many other stories still untold; the last document, of a woman named Zahra, hints at even deeper truths than its disclaimer of semi-fiction had suggested. —M.S. Leo

Dearest Fiona (Fiona Tan, 2023)

More than its cousin artforms, film is inextricably linked to technology. Or rather, film is bound to changes in technology, to updates in not only what is desirable, but possible. These changes are most palpable when we consider how young film is, how novel and volatile its history feels—to watch movies from the past and to anticipate movies from the future is to be at the mercy of memory. And so maybe this medium is the closest we’ve come to making memories with our hands and hearts.

Fiona Tan’s Dearest Fiona follows two memory trails. Neither is of the current year, though both are always present in the filmmaker’s field of view. I wonder about all the memories around a film—some things sit right outside what we see “right now.” Dearest Fiona is maybe about these circumambient bodies, about how in focusing our gaze on the stuff around a life, we realize that they too are lives. The film’s images are a collection of silent, documentary archival material shot in the Netherlands pre-1920. Farmers cut reeds, process them, press and weave them into baskets. Fisherman fish, laborers pour rocks into waterways. The workers are watched by well-dressed men with soft hands. Sometimes someone looks directly at the camera, unable to look away. What was it like to look at a camera in 1909? Was it like looking at the future? To work, at least—and to force a life into living while people and cameras watch you do it—looks much the same as it feels now. By collecting so much disparate footage of labor, Dearest Fiona gestures towards the obvious cruelty of life under capitalism while keeping space open for the in-between stuff—the fugitive smiles and the color-tinted flowers. It does not purport to rescue these long-since-memoried people, but it does resuscitate them, and let their phantom gestures move in the imperfect tempo of living instead of the perfect rigidity of archival entries.

This latter effect is achieved by welcoming this footage into family dialogue. “Dearest Fiona” is how most letters from the filmmaker’s father begin. They span between 1989 and 1990, and two continents; the father is a geologist working for the state government in Victoria, Australia while Fiona is studying in Amsterdam. And so, while Dearest Fiona shows documentary footage of the Dutch 1920s, the letters are read aloud by the Scottish actor Ian Henderson. Sometimes the silent footage unfolds in silence, sometimes with a nearly ambient foley: a bird cheeps, footsteps crinkle, water plinks. There are moments of occasional cohesion—a letter ends with the clatter of rubbish in a dumpster, the father speaks “bird” and the video image produces an array of them—but there mostly exists an un-tension between word and image. It’s not that these things aren’t connected, it’s just that speaking these connections aloud—saying what things mean—never quite gets at how they feel. The colonial reach of Dutch capitalism, the stripping of spices from the Tan family’s home country, Indonesia, the way a daughter misses a father and the color tinting of flowers long since decayed—everything touches everything, everything is simply itself. Dearest Fiona is at once a dare to connect the dots of history and an insistence that memory only functions when it allows itself to un-know things.

“Ambience” as a term has become nearly nothinged, a terminal stand-in for things that warrant more nuanced description. But if there is an ambient thing, I suspect it has to do with the capacity of life—that is, of image and sound and the life between the two—to utter (somehow). Dearest Fiona, named for the most sincere and loving kind of utterance, constructs this kind of ambience and forsakes the banal literalism threatening so much of expression in 2023. It does not tell you to read it, only to witness. It’s a small, perfect proof that for all its technical achievements, film remains at heart a twinned thing, at once a document of the way we were and a correspondence. —Frank Falisi

That Day, on the River (Lei Lei, 2023)

Lei Lei's career has followed a clear trajectory that begins with the exuberant joys of youth to a serious investigation of his family and country’s past. When he began making films in the late 2000s, his animated shorts were always colorful and charming. He’d use ballpoint pens and computer animation, incorporate playful sound effects and collaborate with a rapper, but then his 2013 film Recycled—made with the French photo collector Thomas Sauvin—marked a tremendous shift. He pulled from an archive of more than 500,000 35mm negatives and arranged images with an experimentalist’s flair, incorporating hand-painted film and a noisy soundtrack. The result was an overwhelming sense that there were unknowable histories around us. That project served as a springboard, and Lei Lei now excavates people and places through film, as seen in his major works Breathless Animals (2019), A Bright Summer Diary (2020), and Silver Bird and Rainbow Fish (2022).

As with those works, That Day, on the River is indebted to his parents. Here, Lei Lei takes an interview he conducted with his father and sets the audio to footage culled from old newsreels and Xie Jin’s Woman Basketball Player No. 5 (1957). He repeatedly allows space for us to listen closely, and as his father reminisces about his childhood, the images are regularly choppy, continually stutter, or remain still. (The music, which is usually field recordings or vinyl-skipping loops, have a similar charm.) Having the footage edited in this manner creates distance, reminding viewers of how far in the past this all really feels, but also how much life can be instilled through the recollections of a single man.

That beautiful paradox is mirrored by the father’s stories: they’re largely about how much of a failure he is, but there’s a notable contentment throughout—he’s still very happy with his life. When he shares that he was called a “pale-skinned nerd” as a kid, it’s less about him lamenting the insults so much as being grateful for being able to look back on this time at all. He talks about the death of a classmate, we hear an amusing story about his callousness, and the film ends with him saying, “I’m not good at anything.” He takes it back, though, explaining one thing he can do: draw comics. That Day, on the River looks unrecognizable to that of Lei Lei’s earliest work, but hearing his father mention this artistic proclivity collapses everything into one: father and son, present and past, the unknown and known. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

The Burdened (Amr Gamal, 2023)

“Whether it’s one day or nine months, a child is always a gift.” These words are spoken by a doctor early on in The Burdened, and they’re delivered to Isra’a (Abeer Mohammed), a young mother of three who has fallen pregnant and is desperate to get an abortion. Her equally desperate husband, Ahmed (Khaled Hamdan), drives a bus and refuses to return to middle-class work for the “private channels” which have replaced his former job at a public television station and news network. Their desperation is witnessed by Muna (Samah Alamrani), a religiously devout gynecologist who has rebuffed their request once before.

The weight of displacement is here; a viewer unfamiliar with Yemen’s history will miss an overwhelming amount of the past as prologue. That Aden has been a focal point of unrest for the last thirty years—almost the entirety of Isra’a’s and Ahmed’s lives—is unspoken. For an American audience, the difficulties that Ahmed and Isra’a experience as they seek an abortion by any means necessary will seem like a dire warning about the future of a post-Roe United States. This, however, would be a surface reading that ignores the United States’ own complicity in propping up religious governments in Yemen and the Middle East at large.

Moreover, while The Burdened has an explosive political problem at its core, the film has an extrapolitical goal. In an interview posted to the Berlinale’s YouTube channel, director Amr Gamal states he made The Burdened to preserve places. The settings include different locations from the past 100 years of Yemeni history, from the country’s time as a British colony to its current place as the temporary capital of a Yemeni secession. There is a sense here that Gamal is still figuring out how to tell a story in images. Oftentimes, his preservationist eye lingers too long on street corners and devotes too little to a natural script. Writing in the previous Tone Glow dispatch from Berlinale, Philip Coldiron pointed out a sensibility that’s become common in festival cinema, “in which reliably handsome widescreen compositions are placed one after another, held long enough for the weight of time’s passing to register as s sign of serious art.” The Burdened owes much of its cinematography to this ethnographic lens. Where Gamal excels is in the framing of interiors: the camera holds static in many shops—stuffed to the brim with wares—that Ahmed and Isra’a frequent with their dwindling funds. There’s a feeling of abundance in these spaces that contrasts with the power outages and the lines for water, but the message remains unclear. To what end do these images serve, other than to simply say, “We were here, we were alive, and this is what surrounded us?” Perhaps, in a place like Aden, that’s enough for now. —b/bm

Music (Angela Schanelec, 2023)

Throughout her career, Angela Schanelec has leaned into a rigorous mode of filmmaking that demands the viewer’s attention. Her films contain ellipses, patient long takes, abrupt temporal jumps, minimal dialogue, the same actors being used across decades, and actors’ movements and actions dictating narratives. With Music, she brings Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex tragedy to the modern day, the film’s tension resting in the story’s self-fulfilling prophecy.

In Schanelec’s retelling, Oedipus is Jon (Aliocha Schneider), and his parents are Lucian (Theodore Vrachas) and Iro (Agathe Bonitzer). She depicts Jon from his birth to adulthood, but does so through temporal displacement. At first we see him as an abandoned baby with bruised feet, found inside a stone hut by his new step-parents, Elias (Argyris Xafis) and Merope (Marissa Triantafyllidou). While Schanelec doesn’t neatly transpose the story, nor make it easy to follow, that are subtle clues in continuity. In the following scene, a group of four teenagers drive to the sea and we can assume that Jon is the last person to step out of the vehicle—the man’s feet are bandaged. He has a confrontation with a stranger that leads to this person’s head cracking: a moment that reveals the inescapability of fate.

This leads to Jon meeting with Iro in prison, the two connecting through stirring long gazes. She introduces him to a number of composers—Vivaldi, Handel, Bach, Purcell—which lead him to sing, and eventually heal. A new life begins after his release, as symbolized through the washing of hands; at one point, Iro and Jon bring their hands together. Now living with Jon’s step-parents, the couple have a daughter named Phoebe (Ninel Skrzypczyk). But when Iro discovers the incestual reality of her relationship with Jon, she commits suicide. Then another time lapse occurs: Jon and Phoebe now live in Berlin, and the former is a singer. After an event triggers memories of his past, he frees himself from a tragic ending and takes a new positive tack, singing and dancing with his daughter and friends.

Music invites patients to wade through its labyrinthine structure and remain attentive. In doing so, we become transfixed by Schanelec’s dreamy storytelling. With pensive cinematography, the film offers room to appreciate the beauty of landscapes and bodies, of music and atmosphere. At points, she draws links between characters through specific objects. Jon and his father, for example, are bound through the latter’s thick square-frame glasses and Jon’s eventual vision loss. It is music, however, that proves the most impactful force. When it appears, Jon appears absolved if not liberated: it is in these moments, in a way that contrast to the film’s source material, when he feels in control of his own destiny. —Michael Granados

Horse Opera (Moyra Davey, 2022)

Horse Opera is Moyra Davey’s latest experiment in the collaging of biographies, continuing her juxtapositions of the foreign and personal that began with Les Goddesses (2011). The film is most evocative at its start, when we first experience the beauty of its dry, mundane narration placed atop digitally sharpened nature footage. We learn of a young woman clubbing in New York, and in layering these stories with images from Davey’s own rural isolation, the compounding effect of specific vocal articulations and sharp visual fidelity is overwhelming.

For a while, Horse Opera remains enjoyable in this way: we watch animals blurred by chromatic aberration, we listen to the specifics of a clubber’s life, and we’re placed in a liminal space created by these disparate biographies. A connection, however unlikely, is formed. But over the course of its 72-minute runtime, the density of these parallel lives start to cannibalize each other. One reason for this is the speech’s staccato rhythm—it begins to grate, causing whole segments to blur into indistinguishable passages of overwrought observations and literary quotations. The film departs from its previous simple joys and becomes inert.

The footage follows suit, especially as metatextual elements are drawn in. Davey films herself recording the voiceover, pacing back and forth through tight framing. This establishment of a diegetic connection is a mistake, diluting the mystery that once gave the film life. Even more, as the two narratives are brought together, the film is revealed to be a COVID diary. In dragging the audio and visual components into a master narrative, Davey strips the film of any explorations of time and space it once had. And this reveal, even three years on from the pandemic’s surge, already feels exhausting. —Joe Worpole

Notes from Eremocene (Viera Čákanyová, 2023)

I might propose an alternative title to Notes From Eremocene, Slovakian filmmaker Viera Čákanyová’s feature-length speculative documentary about life in the wreckage of the digital present: Old Media Yells At The Cloud. The original title is a reference to the “age of loneliness” predicted by American biologist E.O. Wilson. Wilson foretold of an era after the mass extinction of most other forms of non-human life; from a series of voice-over dialogues between an affectless once-human avatar and a chipper AI, we gather that Notes from Eremocene takes place in such a future.

These disembodied voices survey digitally-corrupted present-day film footage and spectral machine-vision models, seeking to chart the coordinates of the impending cataclysm. The human voice contemplates the condition of the “botomori,” a figure who rejects the alienation between humans and nature enforced by the “G-DAO,” or Global Decentralised Autonomous Organization, that administers life in the future Eremocene. A specter of techno-optimism at its most insidious, the G-DAO is personified by the voice of crypto pioneer Ralph Merkel, whose inane diatribes on automated democracy are juxtaposed with images of laser-imaged forests (and, regrettably, Burning Man festivities.)

These techno-dystopian themes and post-photographic techniques, while certainly common in contemporary essay films, seem to be at odds with Čákanyová’s original color 16mm footage, which largely hearkens to an earlier age of diary films and artist’s cinema: beaches and woodlands, misty flora, family visits, distanced observations of public gatherings and protests. That such quotidian subjects should be the stuff of dour prognostications about the end of the world says much about the film’s conflicting impulses towards digital soothsaying and analogue commemoration. (Tellingly, the film’s press notes define a botomori as one who “registers their [life story] on analogue film.”)

On the one hand, the film’s schematic oppositions between technocracy and nature, digital visuality and analog materiality, and social isolation and collective action are about as subtle as the word clouds that periodically appear to remind us that images of protesters clashing with police at extraction sites are, in fact, about energy, capitalism, and climate change. On the other hand, by degrading the often beautiful film material with obtrusive datamoshing effects and the sounds of canned glitch, Eremocene suggests a willingness to rethink hazy analog film fetishism in the harsh light of the digital—or, less charitably, a move to retrofit a retrograde form of personal experimental filmmaking for something more fashionably analytical.

The truth is somewhere murkier. Beginning in a compressed storm of swirling pixels, proceeding through those sequences of boldly literalist word clouds, and ending somewhere in the cosmic soup of an astronomy simulator, Notes from Eremocene is a determinedly nebulous film, equally fixated on the color “dye clouds” of film grain and the data clouds that absorb our social lives, identities, and economy like black holes. In A Prehistory of the Cloud, English scholar and data engineer Tung-Hui Hui argues that “analyzing the cloud requires standing at a middle distance from it, mindful of but not wholly immersed in either its virtuality or its materiality.” Undoubtedly, the film’s finest moments are those when the integration of digital effects with 16mm film footage achieves an uncanny, confounding, and even moving hybridity.

Yet, while Notes from Eremocene indisputably drifts between the virtual and the material, the analysis it offers is less mindful than brain-fogged, tracing tenuous and elusive connections between its subjects. Even at their best, essay films often swerve between epiphany and apophany—between the genuine revelation of meaning and the human tendency to perceive patterns in random phenomena like clouds and the convolutions of digital noise. In Notes from Eremocene, Čákanyová spends a good deal of time staring at the cloud through her Bolex viewfinder, but I’m not sure I’m seeing what she’s seeing. —Michael Metzger

De Facto (Selma Doborac, 2023)

Berlinale attendees walked out of Selma Doborac’s De Facto eight minutes into the film, and would continue to do so throughout its 130-minute runtime.The director’s second feature-length project after 2016’s Those Shocking Shaking Days consists of a seemingly endless recitation of wartime atrocities, sourced from the testimonies of the perpetrators of the Holocaust—My Lai, and Abu Ghraib, among others—all delivered by actors in an effective deadpan. Doborac employs fewer than ten shots throughout the film that depict one of the film’s two actors (Christoph Bach and Cornelius Obanya). “Actor 1” and “Actor 2,” as the film credits them, read lines from a wide variety of documents that range from perpetrator statements and witness testimonies to philosophical tracts, and It’s inferred that they’re speaking to each other. In horrifying detail, Actor 1 uses the first person to recite the atrocities “he” committed and witnessed. The other actor responds in the second person, speaking from verdict statements and, at times, from an undefined perspective which seems to offer moral absolution.

At about 15 minute intervals, the film cuts to black with the ambient sounds of wind and birds dropping out too. After a few seconds of reprieve, the torrent resumes with a different shot of the opposing actor. At first, these punctuations structured the pattern of walkouts throughout the film—each time the film was revealed to be taking a breath rather than radically changing, another cohort would depart. Doborac’s approach could seem playful were it not so deadly serious. The subject matter won’t change, of course, nor will the actors suddenly stand or begin to walk around, and the only thing that does shift is the camera’s perspective. The two actors begin slightly off-center in a medium close-up, then are shown framed in symmetry between pillars. After one breath, we see the camera retreat to hold their entire bodies in frame. Very late in the film, Doborac shoots Actor 2 from below, with his head framed against the sky for the final setting of the sun—he delivers his final words almost completely backlit. In these moments, he seems to be fully washed of individuality and granted some aspect of the eternal; he becomes, in some sense, part of the landscape.

Doborac doesn’t quite rotate around the two speakers, but she adamantly forces us to continually rearticulate our perspective toward them. This counteracts the numbness that might protect us from receiving each of the described horrors as such, but it also gets at her greater project, so slowly revealed. “Everyone has access to morality,” Actor 2 recites to Actor 1 in the film’s closing minutes. De Facto posits this not as an opinion, but as a fact for us to negotiate.

As this arc gains clarity, the subtle changes in the film begin to more greatly impress. If the walkouts were initially responses to the lack of change manifesting on screen, they were later a reaction against the consequences of its abundance. When De Facto closes with an establishing shot of a white neoclassical building—one in which we infer the actors have been speaking inside—I nearly jumped out of my seat: a cacophonous krautrock jam breaks out, soundtracking the final several minutes. The harsh disjunct carved in these moments cannot be overstated, as they scar the tissue on which we might have reconciled ourselves with the film’s necessarily irreconcilable position. It reminds us of the chasm between what we can and must remember. —Dylan Adamson

Being in a Place: A Portrait of Margaret Tait (Luke Fowler, 2022)

A central tension: landscape and scenery. Against the image of a wide, dramatic sky, clouds humming golden at their edges, above a field of greens and ochres set to the bass note of a worn stone wall, Margaret Tait avers her preference for the former. The distinction is not elaborated in language, though it’s clear enough in context: landscape contains traces of the lives lived within it, while scenery is inert, transportable, an abstracted sense of place. Poetry is one of the names for the mechanics of this containing, and so Tait is a natural subject for Luke Fowler. If portraiture can be understood as the scenery of figures, abstracting its subjects into signs of themselves, Fowler, following Tait, is after a mode of picturing, direct and richly situated, which remains to be named.

In keeping with her sensibility, Fowler places Tait in the negative space around the images, a recurring voice amongst the chorus comprising the soundtrack, but also a ghostly presence gently shaping attention, guiding the eye toward what matters most in the fields, roads, rooms, and faces of Orkney, the Scottish archipelago where she lived and worked for much of her life. Fowler’s baroque rhythms, largely derived from the work of Robert Beavers, are not Tait’s; she was an artist, like Stevie Smith or Katherine Bradford, capable of arriving at deep, complex wells of emotion through the simplest gestures, naive in the most sophisticated fashion. Still, Fowler finds a point of convergence with her sensibility, which he invites us to consider through an analogy with the pibroch—quite directly, as we at one point hear a description of the casual, rigorous variations on a theme typical of this traditional bagpipe music. (In addition to her filmmaking and poetry, Tait, according to an offhand comment by Fowler after a recent screening in New York, wrote at least one piece in this style.)

The resulting film, based on the plans for an hour-long work called Heartlandscape, thus accommodates rushes and outtakes as yet absent from the official Tait archives beside Fowler’s own footage shot along the scenario’s heart-shaped itinerary, playing variations on her theme. In what’s become his signature visual—the typed or written document shown too quickly to be read in full—we see both official memoranda (condescending interest and rejection via the BBC) and copious notes in Tait’s often inscrutable cursive. This sense of the personal, the internal, is balanced with the social through the faces of Orkney’s current residents, their range of expression, from accommodation to bemusement to pride, refusing to cohere into any general articulation of the local relationship to self image. —Phil Coldiron

Leaving and Staying (Volker Koepp, 2023)

In Leaving and Staying, Volker Koepp delivers a three-hour documentary on the renowned German literary writer Uwe Johnson, exploring setting as a place of history and growth. He begins on the shores of Mecklenburga, a small town in Northeast Germany that’s close to the Baltic Sea and an unofficial home of Johnson’s. Johnson was a nomadic person—not necessarily by choice, but by his disapproval of the East Germany political agenda—and documented his regular travels, which in turn inspired his writings. Some of them appear in a book featuring stories and accounts of the Baltic Sea during the 20th century. Koepp was motivated by these texts to travel the roads and locations of the late author’s life, meeting with his readers, acquaintances, and contemporaries.

Koepp travels to provincial towns and the countryside to better understand his impact. The people are unexpectedly varied: There’s a female author who counts him as an influence, the pastor who confirmed him, and a couple who introduced the writer to his wife Elizabeth, among others. Leaving and Staying is essentially a road movie without the car, focusing instead on the landscapes and locations that Johnson and Koepp both admire. These places are doubled with meaning given the history of the USSR’s invasions; we see the beauty of these spaces, hearing conversations about residents joyfully swimming, and then learn of the wars that took place in the same locales.

Still, the film is primarily animated by personal interviews and one-of-a-kind accounts of Johnson. Young and old both gush about him, speaking to his subversive writing style or the structurally audacious form of his tetralogy, Anniversaries: From a Year in the Life of Gesine Cresspahl. Koepp’s interviews go deep because the interviewees know that he is just as knowledgeable and enthusiastic about Johnson as they are, allowing room for vulnerability. They share about the 1950s, and how Johnson was censored but nevertheless kept hope during these oppressive times. Despite its three-hour runtime, Leaving and Staying moves swiftly due to these engaging conversations, and we understand that Johnson’s writings—which detail different perspectives from various locations—revealed worlds outside of our own. —Michael Granados

Samsara (Lois Patiño, 2023)

Lois Patiño’s latest film, Samsara, is a daring attempt to transcend the representational limits of the medium and take its audience on a spiritual journey. It begins by following a group of mostly teenaged Buddhist monks in Laos as they attend classes and make time for recreation. A boy, who doesn’t appear to be a monk but hangs with the group, takes them to visit his dying grandmother. When she passes, she’s reborn as a goat in a coastal village in Zanzibar, relocating the remainder of the film and introducing new human characters. These discrete parts are connected both temporally and thematically by a shorter middle section. It’s here that Samsara finds its most radical formal exercise. It takes the form of expanded cinema, requesting the audience’s participation to produce a new sort of cinematic experience that represents the passage from one life to another.

This experiment continues Patiño’s longstanding project of representing transitional states of being and liminal spaces. His previous feature, Red Moon Tide, drew from Galician mythology about witches and the procession of souma—it depicted spectral figures frozen between life and death in the aftermath of a shipwreck. In Fajr, bodies slowly faded away into an abstracted nocturnal desert. Night Without Distance experimented with color-reversal film shown in negative to tell the story of smugglers crossing the Galicia-Portugal border at night. There is a clear line through this work which carries formal ideas through a variety of narrative contexts, one which continues with Samsara, especially in its recitation of lines from The Tibetan Book of the Dead. We hear about seeing people you recognize without being able to talk to them: “Your body is a ghost and you visit familiar places as if in a dream.”

Strangely, while a part of Samsara pushes the formal experiments to their most formally radical extreme to date, the rest of the film is Patiño’s most stylistically atypical. Notably, its cinematic language resembles Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s to the point of derivation. This borrowing points to a tension implicit in the whole project: a white European filmmaker makes a film in Laos, purportedly about Buddhist ideas, borrowing the style of an auteur that Western cinephiles closely associate with this region of the world. How does Patiño’s artistic project relate to the realities of these filmed communities? His engagement with Buddhism and other religions feels cursory, limited to quotations from TheTibetan Book of the Dead and an exploration of equivalence among living (and dying) things: a tree that watches passing humans, humans and crabs harvesting seaweed side by side, a couple of Maasai people who describe a tradition of leaving their dead in the forest for other animals to eat, a dying woman who wants to be reborn as an animal and claims people only look down on this notion because they know they mistreat animals. These aren’t shallow ideas, but they’re shallow as representations of complex and diverse religious traditions. Patiño isn’t exploring details of religious ideas or practices, he’s simply relating extracted texts and traditions to his existing interests.

Samsara is, however, more successful as an observational document of the communities it depicts. The camera is as objective and curious as it can be, absorbed in the rhythms of both human and animal life. It also sees how capitalist modernity intrudes upon these webs of life. Some instances are gentle and amusing, as when a monk interrupts the tranquility of forest sounds and flowing water to show his friends a rap song on his smartphone. Others demonstrate the insidious results of commodification. Living things like fish that sustain communities are reduced to fistfuls of cash for exchange, and women are paid next to nothing for their work harvesting seaweed to make soap for hotels and tourists. “Everything is for sale here,” as one character says.

Samsara is aesthetically remarkable, and filled with classically excellent photography. A couple of long shots—of monks scattered about a waterfall, of shadowy figures strolling along a beach in crepuscular light—rework visual ideas from early films in the Distance-Landscape and Duration-Landscape series. Certain moments approach the rapturous spiritual experience the film aims for, as when the diaphanous fabrics of a dreaming monk’s bed are overlaid with beautiful, multicolored mosaic tiles, or when a uniformly blue exterior shot provides a small window into the vivid colors inside a temple. As the film’s transitional segment concludes, the audience is “reborn” into a bedchamber washed in ripples of glowing amber and scarlet. Despite overall mixed results, these dazzling highlights take Patiño’s work in promising new directions. —Alex Fields

The Man Who Envied Women (Yvonne Rainer, 1985)

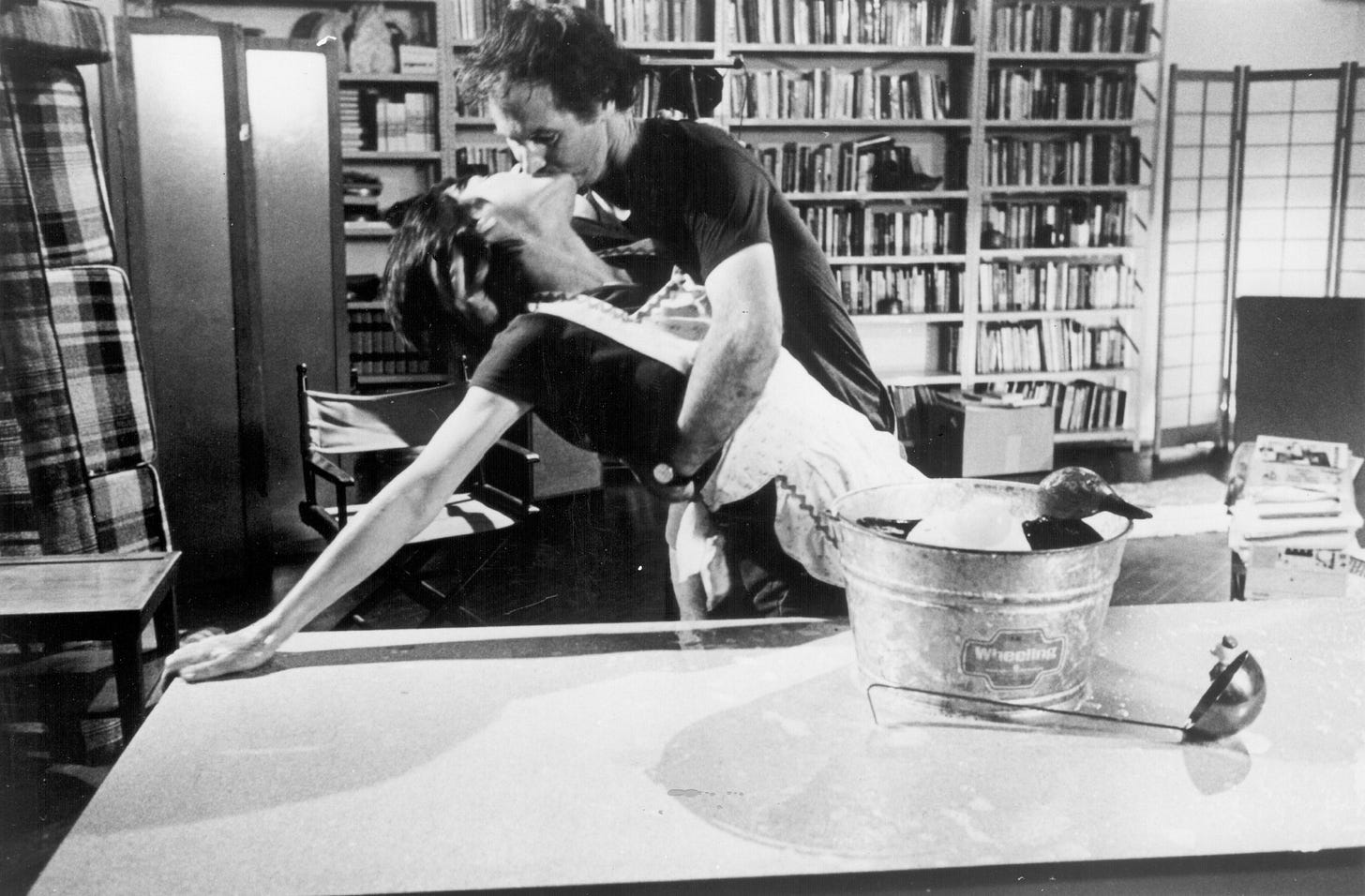

As its Freud-evoking title might suggest, The Man Who Envied Women begins with a linguistics professor named Jack Deller addressing an unseen shrink. He quotes extensively from Raymond Chandler’s personal letters and from academic theory by the likes of Foucault. He tries to explain, despite being a feminist ally, why he has left his wife for a younger woman. These scenes appear to take place on a soundstage, with films playing behind Deller and an audience watching from the position of the camera. That space is at once shared and distinct—it appears to take place on the same set as Deller’s therapy, but he is aware of neither the viewers nor the films. The first scene that plays is the infamous eyeball slice of Un Chien Andalou, which, with the film noirs that follow and the subject of the film, can be understood as a prompt to think about the spectacle of violence against (and the violence of the spectacle of) women.

On the surface, The Man Who Envies Women is a comic takedown of the hypocrisy of a certain type of overeducated, theory-obsessed man. Much of the film follows Deller, played by two different actors (William Raymond and Larry Loomin), and Rainer makes her opinion of this subject known quite early. During an impossibly verbose lecture, the camera tours the room, privileging the body language of students struggling to stay focused as ambient noise overwhelms Deller’s words. The women of the film are represented more abstractly: Choreographer Trisha Brown provides introspective narration of an unseen woman, while Rainer herself narrates documentary scenes of artists testifying before New York politicians about being displaced by increasing rent and other effects of gentrification. The film also makes room to discuss the El Salvador Civil War, often with analyses of how articles and advertisements in a New York Times Magazine issue offer unwitting commentary.

Taken as a whole, these subjects represent what we might describe as three kinds of imperialism—the conquering of the woman and her image; the gentrification of artists’ living space by developers; and, most literally, the United States’ propagation of human rights abuses in a foreign nation. but Rainer is only partially interested in tying these threads together. By taking us on detours through political issues and structuring her film according to three voices—the seen, verbose man (played by two different actors), the unseen woman, and her own—Rainer is frustrating the viewer’s (frequently subconscious) attempts to identify with any one voice or thread in particular. This refusal of conventional methods of spectatorship make for an unlikely echo of Rainer’s earlier artistic career as a choreographer strongly associated with minimalist art. As her famous “No Manifesto” might have declared, The Man Who Envied Women brings us into a space of “no representation.”

Rainer’s psychoanalytically inclined methods of frustrating representation are in accordance with the prevailing feminist film theory of the time. She depicts women not as the subject of the narrative image, at the whims of the camera and the cut, but as the unseen voice, the meaning-maker that determines how we see the images in front of us. Even this voiceover, however, refuses the concept of mastery; it is frequently contradictory and refuses to drive us toward climax or resolution. Instead, the film creates, through its form, a space for the address and contemplation of the viewer. In an era where psychoanalysis has lost most of its cultural currency and questions of representation are routinely morphed into simplistic, content-first configurations, its inclusion in a 2023 festival serves as a welcome reminder that formal choices are themselves political. —Forrest Cardamenis

Thank you for reading the 26th issue of Film Show. See you at next year’s Berlinale.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.