Film Show 024: Berlinale 2023, Part One

Our first dispatch from this year's Berlinale, featuring 15 reviews of movies and installations by James Benning, Hong Sang-soo, Mary Helena Clark, Sanaz Sohrabi, Kevin Jerome Everson, and more

The Berlinale continues to be one of the most exciting major film festivals around. In our first dispatch, we tackle new works from longtime favorites (James Benning, Hong Sang-soo), first-time feature-length filmmakers (Wu Lang, Sebastian Mihăilescu), and essay film extraordinaires (Deborah Stratman, Mary Helena Clark). Below, find reviews of 15 different films and exhibitions that screened at the 73rd annual Berlin International Film Festival.

ALLENSWORTH (James Benning, 2022)

James Benning’s latest film, ALLENSWORTH, looks at the town of the same name, which was the first Black-founded governed town in California and is now a state park. Formally, it’s familiar territory for Benning, composed of twelve five-minute shots, each identified with one month of the year, chronologically ordered from January to December.

The majority of the shots are centered around one of the town’s well-preserved buildings, which are shot in a way that echoes the highly directional and contrasting light in Hopper’s architectural paintings. These are some of Benning’s best compositions in years, a reminder of his near-miraculous ability to capture and develop subtle changes through duration. Images are recomposed in real time through the shifting of sunlight through changing cloud cover. The experience of a static shot is altered subtly but profoundly as a noisy train passes through the background, refocusing our attention such that the “silence” of background noise emerges as a complex soundscape in its own right and the dividing line of the horizon gains emphasis from the lingering vision of the train.

This gradual development of deceptively simple materials informs not just sounds and images but the thematic material and overall structure. The film’s first shot is of a tree in an empty field; it could be anywhere. The next several show buildings framed in relative isolation with nothing to identify the place or time beyond architectural style. ALLENSWORTH slowly reveals its own artifice. A building, which in one shot appears alone, reappears in the background of a subsequent shot; it becomes clear that it’s one in a row of buildings, one piece of a bigger place and history. Halfway through the June segment, a Nina Simone song starts playing with no diegetic source.

As with the town itself—which is more significant for its history than for its architecture—the images gain their meaning through context, the extratextual knowledge the audience brings, and the ways the film gradually invokes and plays with that knowledge. A shot of the town’s schoolhouse (not identified as such) with the U.S. flag flown in its yard is followed by an interior shot where a Black girl reads politically-charged Lucille Clifton poems about race in America. In November, an empty barn mostly obscures what can barely be recognized as a modern city in the far background; until now, nothing in the images themselves identified the time as present day.

December concludes the film with the town’s cemetery, where we can see one named grave (Anna Pierson, 1882-1928) and several that are unmarked. The sound of an aircraft passes overhead, explicitly placing us in the present looking backward at a history we can’t fully know and posing open-ended questions about the fate of Black liberation and self-governance, about how history can be recorded in or erased from the meaning of a place. How much has really changed since the Jim Crow era when the town was founded? Is its dream of autonomy any closer to being realized today? —Alex Fields

The Tree (Ana Vaz, 2022)

Split in two halves—like the cracked rock in the opening shot—Ana Vaz’s latest short film communicates between the past and the present, with cities and ghosts, and to the land that holds their histories. As the Brazilian filmmaker interviews her father on the soundtrack, he slips between first- and second-person recollections. He considers the racial divisions of the cities he lived in and discusses his work as a composer, as shots of a city—the city of the past or a new one—are cut at a regular rhythm, detached from the informal audio. A wide shot emphasizes its place within the landscape, Vaz cuts to a shot of the street that loses this perspective, then goes back to the wide shot that now pans across the city and a cemetery, and then offers a close up of a flower.

A further series of panning shots—now along coastlines—repeat as if searching for something missing. These pans are where Vaz most directly invokes the work of Bruce Baillie, the filmmaker this film was commissioned in response to. The steady single movement of All My Life (1966) becomes anxious and lost: the domestic garden replaced with staggered movements, oceans and horizons. As the interview trails off, Vaz’s camera returns to the city, the flower, and then a split occurs.

After a flare out and what appears to be a change in camera, Vaz cuts the interview audio in favor of sync sound. Humans are pushed to the edge of the frame as the camera records a tree on a cliff. Time is expanded and contracted through shots of the greenery, shifting lighting, and weather—30 seconds at a time. Personal histories of Vaz’s family and country are replaced with a geological history of the land. When Vaz cuts to another tree on a different cliff, more precarious than the last, it holds on in the space between the land and ocean. As time erodes the landscape, Vaz shows the tree rooted at the threshold, anchored against the wind, in an image that contains the past and the present. —Douglas Dixon-Barker

Absence (Wu Lang, 2023)

Director Wu Lang’s feature debut Absence is a moving document of a world in flux. In a memorable early scene, a friend tells the film’s central character Han Jiangyu (Lee Kang-Sheng) that the past ten years have brought as much change to their home province of Hainan Island as the industrial revolution did in 100. Massive high rises puncture the skies above the island, rendering the place more or less unrecognizable to Yu, who has spent the previous decade in prison. The film is not didactic about this point, and Yu never says it explicitly, but you can read the confusion and grief on his face, shell-shocked and sullen as he begins to reconnect with the places and people of his past.

Great care is paid to Yu’s smallness amid the seismic shifts his world has undergone and his distance from the people he interacts with. When he walks down city streets, he’s swallowed in the frame by the bustle of the world and the scale of the architecture around him. It provokes a sense of alienation, a profound loneliness, even as he’s surrounded by people who care about him. Early into Yu’s re-acclimation, there’s a heroic shot of a towering skyline—but it’s a subtle trick, as a slow pan reveals the image to be a piece of artwork being carried through an office. Progress, the playful moment suggests, is not always as it seems.

The film’s rhythm is slow and deliberate, with the most intense emotions Yu is experiencing left to bubble under the surface, which only magnifies this sense of loss. In an interview included with the film’s press kit, Wu explains that while Absence isn’t based on any particular circumstance, the feelings that Yu experiences are based in reality. Since the early ’90s, he explains, Hainan Island has undergone an intense period of development and urbanization, which has changed the character of the place and its people. “Faced with the illusion of the new world, people cut off their roots in their homeland and head out for the new world,” he says.

Absence is full of characters who embody this idea in different ways. There’s Kai (Ren Ke), an upwardly striving friend of Yu, who’s entangled in various businesses (some legitimate and some seemingly otherwise) and is eager to take whatever advantages and luxuries the circumstances might offer him. There’s also Su Hong (Li Meng), an erstwhile lover who Yu is desperate to reconnect with as she battles real estate bureaucracy to provide stability and comfort for her daughter.

Still, in their own plodding way, everyone trudges forward, attempting to build a life amid the feelings of detachment and disconnect. Yu and his new family take refuge in the half-finished skeleton of a skyscraper, left fallow as a result of a real estate bubble. What he builds there doesn’t look comfortable, but it’s a refuge from the world outside; it’s a small place where he can truly begin again. The burdens of the world still lurk outside, but peace, placidity, and true interpersonal connection still seem possible.

Wu has said he made Absence as a way of remembering this period of rapid growth on Hainan Island—the ache that it causes and the way it disrupted people's ways of living. These feelings, he says, “will disappear in the process of change.” But even if the film is intended as a document of these difficult times, its spirit ends up feeling optimistic. It makes a case for resilience and perseverance—not along an intended or expected path, but in finding your own, and making space for the people you care about along the way. —Colin Joyce

If You Don’t Watch the Way You Move (Kevin Jerome Everson, 2023)

Kevin Jerome Everson unfurls documentary time in a Warholian manner in his latest short film, If You Don’t Watch the Way You Move. Its title is derived from a line in “Shiesty,” a song by rap group BmE. Three men—rappers Derek “Dripp” Whitfeld Jr. and Taymond “ChoSkii” Hughes, along with producer Jermaine “Country Blakk” Brown—are in a Columbus, Mississippi studio recording the track. As the men leave the booth to revel in the playback, Everson’s camera follows them in an unbroken take, zooming out from claustrophobic close-ups to a wide shot. Due to the low light, heavy grain and visual noise permeate the image. As they listen, the visual composition oddly favors their legs and shoes. The music drops out and we hear silence for 4 minutes and 33 seconds—a reference to the John Cage composition. The remaining sound is of cicadas; one could think the sound was coming from an open porch door on a summer night just beyond our field of vision. The studio setting deems it unlikely, however, as a smoke alarm intermittently beeps its low battery signal. (It’s heard before and after—but not during—the silent passage.) Because their sonic existence seems to have been temporarily silenced, it’s unclear if the men in the frame are also sitting in silence, but their posture suggests as much: a rare moment of meditative contemplation as a key part of the process. When “Shiesty” drops back in, they share a moment of muted jubilation, a recognition of the change they have undergone by simply existing in time. —Maximilien Luc Proctor

Forms of Forgetting (Burak Çevik, 2023)

Not yet 30, Burak Çevik has already covered a wide formal range: two narrative features, a pair of found-footage experiments, and one of cinema’s stranger recent instances of collaboration, A Woman Escapes, made with Sofia Bohdanowicz and Blake Williams. It turns out that much of the footage he contributed to the latter film was drawn from the same material which comprises Forms of Forgetting, which, at 70 minutes, has the feeling of a long short. This is very much in the vein of what’s become a new standard style for festival fare: slow moving but without the extreme longueurs of “slow cinema,” with a general aversion to overt rhythm or montage in the edit, in which reliably handsome widescreen compositions are placed one after another, held long enough for the weight of time’s passing to register as a sign of serious art without running the risk of losing the audience. (Topology of Memory, in contrast, with its crawling, endless pans of lo-fi surveillance footage, felt like both a genuine provocation of attention and something new rhythmically; I don’t know that I ever need to experience it again, but four years on, I think of it often.)

Though much of the content of these shots likewise feels familiar—industrial work at a shipyard and construction site, a landscape strewn with ruins—there are moments of real surprise, as when a scene built largely from extreme close-ups on the skin of an elephant is enlivened by freeze frames, or when a delight of physical comedy emerges from a straining tugboat’s efforts to drag a heavily laden barge. The ending—an abrupt left turn interpolating a classic of avant-garde cinema—is both undeniably bold and, in its way, thematically resonant, though it marks such a jagged shift in tone that I find it impossible to reconcile it with the film as a whole.

Whatever my frustrations, the core of Forms—a pair of shots spanning its fifth to twenty-third minutes—would make a remarkable work on its own. The first shows a tight frame on a hole cut in ice, hands occasionally appearing to reposition the fishing net which sits inside it, bobbing just on the verge of being lost for good. As an image of how memory works—a tangled web amidst a shimmering surface, always on the edge of the abyss—it avoids any preciousness through the simple, careful, unfussy nature of this practical action. The second shot sees the man and woman whose conversational voiceover covers the film, seated on the wooden steps of a small theater. Onscreen they chat, snacking and smoking, about their memories of a breakup some time ago, while on the soundtrack they respond to the footage of this conversation, itself now a documentary of their history, with voices and memories oscillating and creating feedback in the ongoing present of the finished film. (Watching this with subtitles—their commentary runs across the top of the frame, with their dialogue on the bottom—has the effect of making the scene considerably more legible than I imagine it would be for a Turkish speaker.) The mundane details of their history matter less than the casual music of their conversations, a harmony of bemusement and annoyance, warmth and distance, which does strike me as something like the sound of how difficult it is to forget what you’ve truly known. —Phil Coldiron

Here (Bas Devos, 2023)

Here is Bas Devos’ gentlest film. While the Belgian director has always had a masterful control of the long take—using it to flesh out moods and ideas without succumbing to an anemic austerity—it has never felt more at home than on this straightforward tale of soup, friendship, and the interconnectedness of all life. We meet Stefan (Stefan Gota), a Romanian construction worker in Brussels, who is readying himself to depart for home. He’s on the floor of his kitchen, emptying his fridge and collecting ingredients for a soup he later gives to others. In having him on the ground, there’s an intimacy to the scene, but also a connection being made to the earth beneath him and those he’ll feed. Later, when we see him put his soup on the kitchen counter, there’s a sudden match cut of an onion being pulled from the ground. In its simple, inviting maneuvers, Here asks one to consider the way we are beholden to—and connected by —the natural world.

It could all feel so precious if it weren’t for how striking Devos’ images are. He guides us into different spaces—a forest, a restaurant, a garden—with humility. Specifically, he strives for an active, attentive viewing process, analogous to the work of a bryologist. The shots of moss are literal opportunities to experience such moments, as are those of cells viewed through a microscope. The relationships between people are lovingly presented too. Stefan meets a restaurant worker named ShuXiu (Liyo Gong), and she along with other characters feel almost NPC-esque in the way they seem to just sort of exist. The resulting feeling is of Here being dreamlike and out of time, with every person acting as a reminder of the beauty inherent to each interaction. “Could you just talk a bit? Please? I just want to listen to your voice,” Stefan says at one point.

Such poetics are most impactful when transmitted through visuals. Devos spends ample time resting on a specific locale to see its subtle transformation. In one passage, a plane flies overhead and we see how it causes light to delicately shift across a forest. In a remarkable sequence near the film’s end, lamp posts gradually brighten a dark area, the subtlety of the moment matched by its emotional impact. By this point, Devos has tastefully stitched together minor events that point to the richness of existence. When he overlays images of a train and a person lying on bed, we understand that stasis and energy are both here. When a woman tells Stefan that his unidentified seeds are likely oats, and explains that “they can float far, carried by the wind,” he is pointing to how life is always itinerant, at least in spirit. And when the credits appear with every name appearing at once—as if on display on a giant poster—Devos wants his audience to know that even this work is a collective effort. Here is a film of simple, emotional gestures, and it succeeds because Devos makes patience seductive. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Scenes of Extraction (Sanaz Sohrabi, 2023)

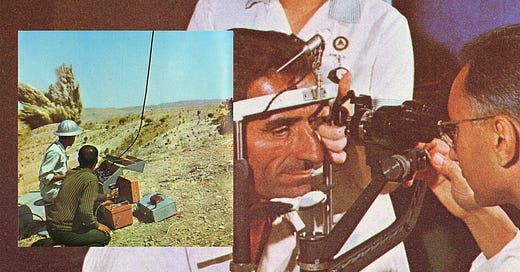

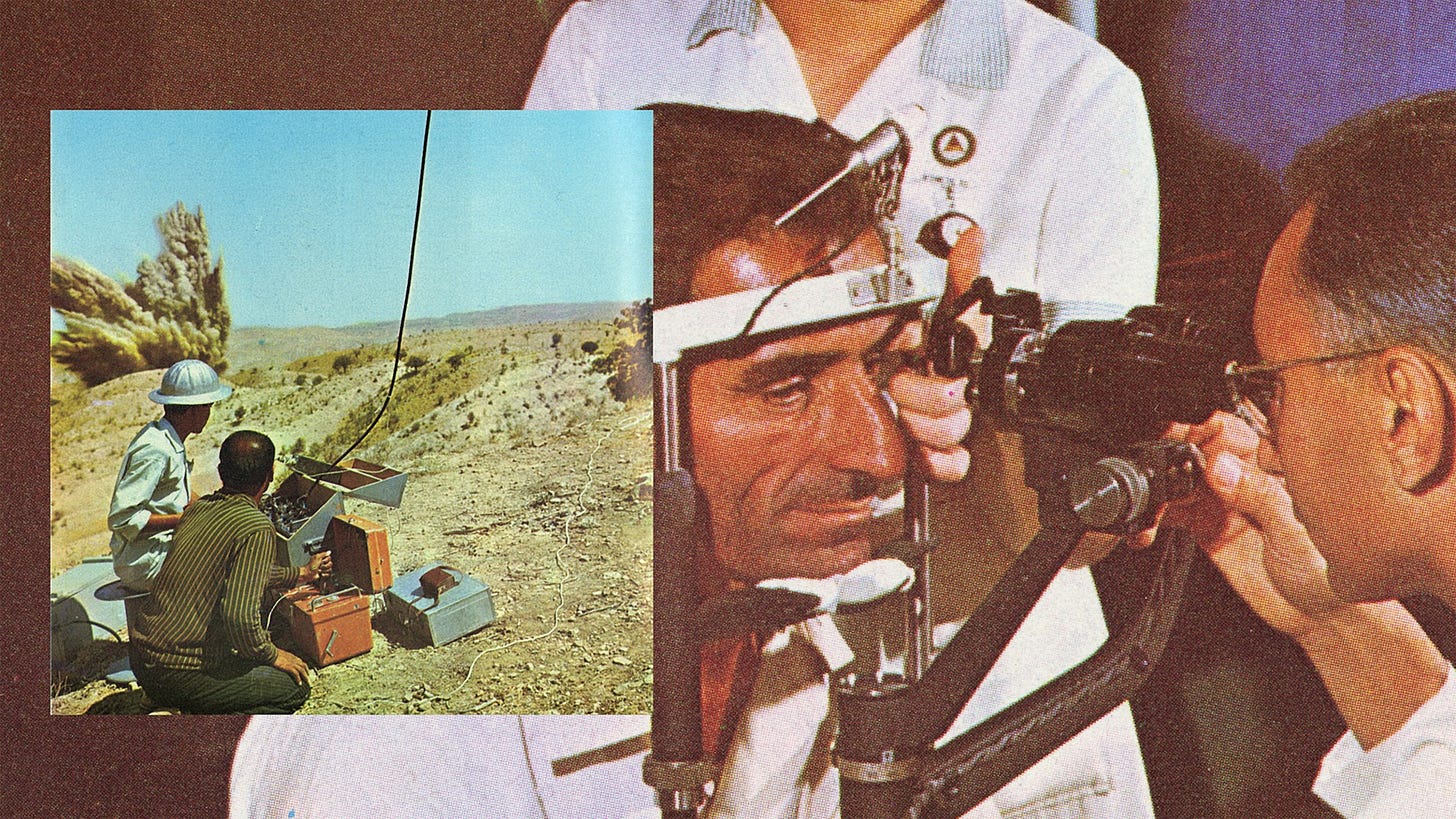

Sanaz Sohrabi describes herself, tellingly, as a “researcher of visual culture and an artist-filmmaker,” signaling the primacy of archival inquiry and intervention in her work. Scenes of Extraction, like its 2020 predecessor One Image, Two Acts, adopts the essay film form to examine the photographic and cinematic archives of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC, now British Petroleum), whose campaign of extraction defined the first half of 20th-century Iranian industry and national politics. Both films argue that the camera was a key instrument in the British exploitation of Iran’s landscape and people. One Image, Two Acts positioned cinema as both an instrument of imperial power and a site of anti-colonial resistance through strategies of spatialization, slicing BP archival photographs into billowing sculptures and classic Iranian New Wave films into split-screen commentaries. To suit Scenes of Extraction’s narrower focus on ethnographic and geological surveys, Sohrabi scales back her repertoire of collage effects and source materials, with digital manipulations supplanting the previous film’s more tactile interventions.

From its digressive critique of technical images to its soberly poetic analysis delivered (in Farsi) on the soundtrack, Scenes of Extraction plays to the strengths of the Farockian essay-film tradition, particularly in negotiating ethical anxieties around images as instruments of exploitation. Does creatively using the visible evidence of conquest amount to collusion with it? The petroleum industry used images to at once document and destroy worlds; similarly, Scenes must resurrect and reproduce violent artifacts in order to subvert them. Sohrabi’s nested frames and 3D-rendered topographies echo the visual and geological surveys of the AIOC: as oil engineers used the cataclysmic practice of “reflection seismology” to sound out potentially oil-rich terrain by measuring the repercussions of controlled explosions, so Sohrabi fragments and abstracts archival images to expose the corrosive logics of extraction at their core.

The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company circulated racialized portraits of “native types” in both photography and film propaganda, scenes which formed the background for the machinery of the extractive project. “Those inhabiting the shadow economy of extraction in the background,” Sohrabi observes, “were also coded through racial difference and dispossessed of the wealth generated by the same machinery of oil.” Sohrabi’s superimpositions disrupt the lure of the ethnographic gaze by fusing these deceptively pastoral scenes of “non-modern Others” with topologies and diagrams. Her strategies of layering and juxtaposition invert these planes of information, drawing out traces of everyday Iranian life and culture deposited in the shadows of oil archives.

At moments, the film relaxes its aggressively-collaged aesthetic, opening up space for documentary footage depicting vanished forms of craft, labor, and sociality. By adding naturalistic sound to these otherwise unmodified shots, Sohrabi exceeds her role as researcher, pointing beyond the analytical towards a more integrative, even restorative project. Might these images, despite the compromised context of their production, still contain residues of lived experience that deserve to be recovered? In these moments, Sohrabi reclaims both these images and these techniques, challenging the BP archive’s right “to constitute and memorialize the historical event of extraction.”

We can glimpse something deeply melancholy about the film’s project in these briefly transportive sequences. Scenes of Extraction is largely a testimony to the ruination made visible in the archive. As a researcher, Sohrabi has a responsibility to bear witness and to reveal, which she accomplishes with impressive skill and resourcefulness. But the film also throbs with the tremors of a restorative imagination, foreshadowing radical alternatives to the visual culture of oil—and, perhaps, to the anxiously analytical strategies of the essay film. —Michael Metzger

Last Things (Deborah Stratman, 2023)

In Last Things, Deborah Stratman explores the times inhabited by rocks and the modes of temporal perception we need to apprehend them—not as a past event, but a present unfolding destined to outlast us all. The film’s narrative arc is bound together by storytellers whose work has sought to study, recognize, or conjure the agentic power of non-organic matter. Passages drawn from J.-H. Rosny’s sci-fi novels narrate humans confronted with a non-organic and mineral other, both in the prehistoric past and a far future of imminent human extinction. While these encounters still linger on the edges of human chronology, the temporal markers invoked by geologist Marcia Bjornerud exit our timeline completely. Over mesmerizing footage of chondrules that appear at once microscopic and galactic, she reminds us that we currently co-exist with matter that pre-dates the sun. To Bjornerud, matter is storied: it holds memories we can enter if we just know where and how to look.

How to develop this kind of literacy—what Bjornerud calls a polytemporal worldview—is Last Things’ central question. Rather than striving for narrative cohesion, Stratman works in an affective register of suspension and temporal dislocation. Fact and fiction become blurred through alternating narrations, as well as the contrasting use of mineral imagery at its most familiar and most alien: quotidian scenes of hikers on a rocky trail blend with dream-like footage of delicate single-celled organisms. The latter float gently across the screen, having yet to fossilize into rocky sediment. Combining this footage with sonic textures that evoke a sense of time outside space, Stratman unsettles the idiomatic permanence often attributed to the mineral form, creating space for the timescales across which rocks change and evolve to register instead.

In this sense, Last Things may be thought of as what historian Gabrielle Hecht calls an interscalar vehicle: “a mode of analysis allowing scholars and subjects to move simultaneously through deep time and human time, through geological space and political space.” Adopting a polytemporal worldview requires not just recognizing a plurality of times, but also acknowledging the force field between them. Midway through the film, Bjornerud’s account of the mineral source of all life is juxtaposed to a sequence of evolutionary charts. They are the trees of life as imagined by prominent 19th century biologists, but they lack roots in the mineral kingdom, a reminder that those granted the scientific legitimacy to classify and periodize have always had the power to determine what or who is “other.”

In tracing a multiplicity of evolutionary paths, Stratman ponders the variegated nature of extinction: as threat, tragedy, inevitability, and cyclical repetition. Through lingering shots of petroglyphs, man-made stone structures and archaeological sites, the film turns to the generative and destructive uses of rock carving: from inscription and inhabitation to relentless extraction. Acknowledging the present state of emergency without surrendering to it, Stratman shows that the act of paying closer attention to mineral life can also be a search for less extractive ways of relating to it. Human and mineral bodies come together one last time in a closing scene of capoeira street dancers. The camera focuses less on the dancers themselves than on the movement of their palms pressing into the tiled sidewalk. What is our brief dance on earth if not a pas de deux? —Miriam Matthiessen

Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you (Walid Raad, 2022)

Comrade leader, comrade leader, how nice to see you is a two-channel video installation by Walid Raad, presented as part of the Forum Expanded Exhibition. Occupying the far wall of silent green Kulturequarter’s subterranean gallery space, the work is first encountered from a distance, two side-by-side floor-to-ceiling waterfalls, resembling a ghostly apparition of Olafur Eliasson’s installations.

Viewed properly, however, a set of small cut-out figures emerge, lined up carefully on the ground before the installation wall. Illuminated by the frothing projected water, these figures, not more than 30 cm tall, are miniature representations of political leaders. The falls are Lebanon’s “Fickle Falls” and at one point were named after the politicians whose miniature Raad has placed in front of them. As the wall text goes on to explain:

To honor their backers, many militias decided to name some particularity beautiful Lebanese waterfalls after the leaders of the countries backing them. And when the alliances shifted, they simply decided to rename the waterfall again, and again, and again.

The work is silent but it’s room in silent green is not, filled most prominently by the low rumbling of Eduardo Williams’ A Very Long Gif found on the adjacent wall. This inadvertent soundtrack doesn’t necessarily disrupt Raad’s work, however, occasionally heightening the immersion as A Very Long Gif’s ambient sonic evidence of human activity can easily be mistaken for the distant sound of crashing water.

The effect of Comrades is striking and playful, the visual irony of these world historical figures brought small and submerged by torrents of water immediately apparent. The work is unambiguous concerning who is in control, that far from these individuals having some sort of authority over the waterfall that bore their name, it is the forces of nature that ultimately decide where and how history is remembered. —Angus Macdonald

Exhibition (Mary Helena Clark, 2022)

Departing both literally and in spirit from the Étant donnés, Mary Helena Clark’s first outright comedy is a droll parody of the current vogue for the essayistic, for the curatorial as its own artistic practice. Voiced in deep, precise deadpan by the writer Audrey Wollen (herself a fine comedian of the Tumblr and early Instagram era), Exhibition wanders lightly, tipsily—like any fun night at an opening—through a series of sketches, each concerned with the various partitions that order life and art: walls, windows, doors, canvases. While Clark’s always been a great scavenger of images, here the found becomes dominant, and if the results are somewhat less visually compelling than usual, the introduction of her writing—an odd prose swerving between history, ekphrasis, citation, and speculation—elevates the whole to her usual high standard.

We open on a fuzzy circle, black on white, which smoothly separates into a pair, popping in and out of place, the ambience of mechanical clicking and humming AC drawing out the sense of ophthalmological examination: “It’s difficult to describe. A wooden door, its cavity framed in brick. Rough hewn, splintered planks. Without hinges or a latch, it appears unopenable. It appears to have two peepholes.” Then, as the camera pans up a newspaper photo of a woman, low heels and an A-line skirt, before the door which attaches the viewer to Duchamp’s final work, “The old joke comes to mind. ‘Whatever you do, don’t sleep with my daughter,’ says the farmer, who has graciously invited you to stay the night.” Two minutes into the film’s 18, its tone and logic are set.

From here, Clark proceeds through disparate subjects, moving with the associational logic prescribed by her found form, steadily pulling the rug. A Swedish outsider artist, Eija-Riita Berlinermaur, fills her home with miniatures and, as her surname suggests, marries the Berlin Wall. Hilary Swank, playing the American suffragette Alice Paul, is force-fed in a bootleg copy of a forgotten HBO miniseries. A late-19th century painting by Ilya Repin, showing the return of a revolutionary from exile, is subjected to mock-pedagogical examination. Heavily masked images accompany an academic text on the mechanics of attention. Another suffragette, the British Mary Richardson, casually takes an axe to the Rokeby Venus, a metronome tapping as the scene is narrated atop the image of a hand sketching the painting’s central figure, which gives way to a tightly cropped vertical composition of clouds drifting in a soft blue sky before arriving at archival documents relating to the event. “Then came an erotic thought: what if you had no inside?” With this, the closing movement commences, a survey of Klein bottles, intricate, hermetic, and useless glass objects, one of which, to the horror of its maker, proves an elegant candle holder, closing the Duchampian circle.

On their surface, the connections arranged by these passages are plain enough in the current manner of the essay film, accumulating into, as Clark’s artist note puts it, “a meditation on the assertion and refusal of subjecthood.” Were it only this, played straight, it would be one of the better instances of what’s, by now, something of a generic type. But her sensibility isn’t one of adding up, it’s one of dispersal, of spinning off. The groom, for example, is here stripped bare by its bachelors. Or, midway through, a line of psychoanalytic feminism which bears an at least oblique relation to the facts of Wollen’s family history: “A gap is only a problem if it needs to be filled.” I prefer the copy of the note on the film’s Vimeo preview, where “mediation” slips in for “meditation,” clarifying its capacity to conjure meaning from someplace between-beyond sight and sound, its diagnosis of the limits of certainty within current art, the depth of its humor. —Phil Coldiron

Home Invasion (Graeme Arnfield, 2023)

Graeme Arnfield’s Home Invasion is an unfortunate reminder that essay films are at their most compelling when utilizing the full breadth of both mediums’ possibilities, and not when simply transposing an essay into film. Arnfield’s film has evocative moments—it filters music through a Ring camera’s hyper-compressed microphone, it revels in the mutated colors derived from the camera’s sensor, and embraces the materiality of the paranoid bourgeois—but its clumsy tone and conflicted structure hamper attempts at capturing the vast history of class warfare embedded in domestic surveillance systems.

Arnfield constrains each image to the voyeuristic frame of a peephole, playfully adopting the materiality and form of its subject. But his curation of wonderfully candid found footage and archival imagery is often marred by superimposed text that simply mirrors their meaning, resulting in redundancy and clutter. The text’s tone is admittedly fun: it channels the taglines of horror movies (“her home had become her nightmare”) to produce heightened melodrama. But even that becomes strained as Arnfield attempts to cover history, film theory, and political consciousness all at once. When focusing on home invasion movies, the pulpy tone—which had previously given the film a tongue-in-cheek flair—now inhibits the film’s ability to convey information. The communication is poor, especially in one passage that links cross-cutting and the bourgeois’ obsession with upholding the sanctity of interior spaces. This film theory is spoon-fed in quippy fragments spaced apart in the edit, stunted and awkward in their delivery. In fact, the film’s most impactful depiction of resistance is wordless: a kid spitting on the Ring camera, refracting the neighborhood as the spew trickles down.

In a highlight from the film’s opening section, the Ring doorbell is systematically tested against domestic subjects such as dogs and thieves. It eventually transitions into a non-chronological, overwhelming narrative about the history of the doorbell. It’s fascinating: we witness a text-led reconstruction of the doorbell’s invention as a result of working class resistance, as well as the capitalist subsumption of the original camera doorbell’s nuanced purpose. And in using reverberating field recordings and a warped sans-serif typeface, Arnfield suffuses these historical vignettes with a perverse mundanity. Still, Home Invasion is only intermittently enjoyable; its repetitive audio-visual signature can try to bind these scattered pieces, but the assemblage is ultimately confused. The vignettes themselves are edited with a poetic license: every story begins with the protagonist “[waking] up from a nightmare,” and these ideas are funneled through the lived experience of a single individual. The film also attempts to construct these histories into a semi-structuralist finale in which the non-chronological chapters are left as loose associations. This tension between micro and macro narratives only dilutes Arnfield’s efforts. —Joe Worpole

Fantastic Machine (Axel Danielson & Maximilien Van Aertryck, 2023)

Fantastic Machine is an essay film about the history and function of moving images, how they construct and manipulate meaning, and their influence on our vision and experience of the world. It begins with a brief history of the development of film as a medium, covering familiar territory from Daguerre to Muybridge to Méliès and discussing both its historical use and how the technology functioned. The staged “filming” of the 1902 coronation of Edward VII by Georges Méliès bridges this early history with the film’s real concern: the power of images to manipulate meaning and outright deceive.

This idea is developed through a few stops in the world of photojournalism and news media, but the ultimate destination, which takes up the film’s entire second half, is contemporary digital media culture. Here the filmmakers find that we just can’t look away. A variety of forms of performance and reaction are marshaled to demonstrate the banality of online media culture: ISIS videos, a long clip of a livestreamer repeatedly getting into trouble because his followers call people they see in his stream (and they eventually call the police), and a young woman who becomes famous for videos where she makes sex noises while eating (and then makes millions cashing in on OnlyFans). We’re just chimps clicking on whatever shows up in our feed, the film literally suggests.

This is a superficial argument you could hear in passing from anyone remotely familiar with social media. The film makes little effort to put its array of evidence into a meaningful context or develop an analysis deeper than just pointing at examples. It doesn’t take digital media seriously as art as it did earlier instances of the history of photography, and it doesn’t consider the complex uses and effects of digital media for political organizing, for marginalized communities who find self-expression through social media, or any number of other possible angles. What begins as an argument about the constructed and contextual meaning of images, and could’ve been a simplified but usable 21st century update on Ways of Seeing, ends up as a passé gloss on the narcissism of internet culture. Whatever serious problems arise from that culture, this film essay is far too simple and reductive to contribute anything toward understanding them, let alone a solution. —Alex Fields

Mammalia (Sebastian Mihăilescu, 2023)

Mammalia’s anthropological title contains a genuine exploratory impulse. In Sebastian Mihăilescu’s conception, the human body is not somewhere gender is located, but somewhere it happens. He escapes aesthetic determinism through playfulness, adorning bodies sexed as male in signifiers of womanhood—flowing wigs, willowy dresses, artificial pregnancies—while his female characters enact an agency only lightly troubled by voyeurs, who more often are force-femmed into passivity. The plot appears to follow a cuckold’s quest for conquest before ending in absurdist parody: denied dominance, Mammalia’s central figure becomes an expectant “mother” in a play-acted baby shower, a parental rite of passage for somebody who wouldn’t otherwise have one.

Through this queered perspective, Mammalia never quite resembles anything else you’ve seen. The more it confounds expectation, the truer its experiments come to feel. A story in the middle, about a deep-voiced, long-haired person weathering social disapproval, digs into feelings too troublingly real for fiction. These moments of deeper gendered anguish are infrequent, but they provide a welcome corrective to what could be read as white masculinist style. Too often, horror-adjacent cinema maintains a vice grip on its imparted meanings, ambiguity over-determined to the point of self-defeat. Hermetic social systems in collapse are an easy target for aspiring art films, especially of the European persuasion; making gender itself the subject of study has a more personal feel to it than glib jokes about the general state of straight society.

On the surface, Mammalia reads as a long-take Eurohorror—Lanthimosian but with the useful distinction of bolder colors and better compositions. Mihăilescu’s oppressive images say plenty, but the music adds aural intrigue to mostly static frames, with vague promises of violence hinted in droning synthwork. A scene near the climax finds Mammalia’s gender-defiant collective gathered by a lake, echolalia and swirling ambience punctuated by drumbeat. The A24 approach would be to emphasize cult-like behavior with viscera, but here the sprays of blood come almost as an afterthought. It reads not as a failure to honor genre so much as a way of avoiding conventions that come too easily, in keeping with Mihăilescu’s suspicion toward the “naturalness” of gender and how it is expressed.

In all this potential energy, there is not much actual kineticism, which can be frustrating when genre payoffs are repeatedly invoked before being denied. Yet Mammalia has the courtesy to leave you guessing what’s next, and the confidence to let you figure out just what it’s saying. Mihăilescu concludes his film with a body not meant to bear children doubled over in apprehension, fear wracking its slender frame. Are we about to witness something impossible in the framework of sexual convention? How far can fiction push the limits of flesh and blood? The final cut to credits feels like a pulled punch, but the suggestion of what could’ve been, performed with just enough conviction by a gender non-conforming cast, lingers in possibility. —M.S. Leo

The Shadowless Tower (Zhang Lu, 2022)

In The Shadowless Tower, the Chinese-Korean filmmaker Zhang Lu sets his sights on familiar terrain: a middle class, middle-aged man in search of his bearings in this world. He looks to the distant past, and early in the film a backpedaling passerby tells our protagonist, “Walk backward, it gives the spirit a lift.” Gu Wentong, portrayed in an exquisite register of malaise by Xin Baiqing, is a divorced food critic and former poet. He discovers that his estranged father has, for years, been keeping in touch with his brother-in-law. In confronting this relationship with his father, who is a lonely man devoid of personal connections, Gu finds his own life cast in an unforgiving light. Much of The Shadowless Tower is spent walking, smoking cigarettes, and engaged in faltering, uncertain conversation. “I didn’t mean that” becomes a refrain for Gu, particularly when speaking to the younger, impulsive female photographer traveling with him (Huang Yao). The script takes great pains to remind us of his never-quite-sexual, never-quite-parental relationship with her, and that it stands in for the other deficits in his life.

Piao Songri’s delicate lensing sometimes arrives at a composition that’s gobsmacking—enough to stir us from the numbness that the drama cannot help but engender. The meandering plot occasionally attains a higher calling of morosity, as when Gu drunkenly performs the 2008 Olympic song, “Beijing Welcomes You,” at a morbid reunion of college friends. Zhang, however, leaves a luxurious amount of room for interpretation. Gu’s relationship with the photographer is emblematic of a pattern that suffuses every interpersonal relationship in the film: we’re never quite certain exactly how these people are related, and on both an ontological and thematic level, we’re forced to interpret them in varying lights; Gu’s tenant initially seems like a relative, his daughter a niece, his friend an ex-wife. In every person, he’s looking for someone else. But while The Shadowless Tower’s circuitous routes consistently intrigue, Zhang’s inquiry exhausts itself before it begins. His loneliness is stated again and again, without ever delving into novel territory. —Dylan Adamson

In Water (Hong Sang-soo, 2023)

In Water is at once the most audacious and unexpectedly personal film that Hong Sang-soo has made in years. The Korean director has never shied away from putting his life on screen, having characters function as stand-ins for himself, but he takes a more experimental tack here by capturing the phenomenological reality of living with poor eyesight. Notably, Hong has had vision problems since working on Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors in 2000, and has neglected to make concerted efforts to prevent further issues. His fatalistic acceptance isn’t sorrowful, though, as he’s had a positive outlook on his circumstances. “I can even sense when a problem will arise,” he told Koreana about his fading vision in 2009. “Because I can sense its onset, I can also control it.”

Hong is constantly revealing different modalities of clarity even when his images aren’t in focus, either by highlighting other senses or stressing the emotional undercurrent of a scene. We follow the actor turned director Sungmo (Shin Seokho) as he aims to make a film alongside two former classmates, one of whom will be the actress (Kim Seungyun) and the other the movie’s cameraman (Ha Seongguk). “I want to find out whether I have any creativity,” Sungmo explains, as a wooden pole divides the screen in two, his body separated from the others. Their relationship dynamics are made plain from the positioning, and their histories are explained in the conversation, but the sound plays a crucial role too. As Sungmo talks about wanting to attain honor via filmmaking, a slew of cars pass by in the background, their unceasing clamor like a Greek chorus taunting his foolhardy aspirations. Later, when the two classmates pass time by talking about Tae Kwon Do—the woman is a third-degree black belt—their flirtatious moment feels all the more sweet because of the obfuscated image; Sungmo is in the frame, but his body’s blurry contours have him readily blend in with the environment, easy to be forgotten.

Hong’s conceit evolves with In Water’s second half. As the actress details a frightening, unknown sound, her explanation becomes a meta opportunity to reflect on how poor vision leads to an attunement to individual noises. There are passages when we hear the diegetic sounds of wind and water, making images of lapping waves feel all the more idyllic. At one point, lo-fi guitar strums soundtrack a shot of mountains and the sea. As a cut suddenly leads to a new, clearer image, it feels like we’ve gone to the optometrist and are A/B testing with a phoropter. The second image isn’t pristine, but it’s enough to reveal the glory of what we’re currently viewing and are still able to imagine. “I’m sure there’s a world we can’t see,” notes Ha’s character in a short conversation about ghosts. The allure of the invisible is potent.

For Hong, filmmaking is a chance to capture the realm of the impossible. When Sungmo walks onto the beach to see a woman cleaning the area, her act of volunteerism becomes the inspiration for his own movie—one he has no script for, and was ready to improvise. When we see an approximation of this scene getting filmed, this shot is more lustrous than the original one we saw beforehand, with a seductive gold-orange now suffusing the environment with an alluring mystique. In Water is about this evocative feedback loop between fact and fiction, of what we can’t see and what we decide to see instead. In the film’s final shot, Sungmo walks into the ocean, eventually disappearing into its impressionistic blues. As he does this, a song that he wrote is playing, and it’s about a man swimming into the sea to avoid the pains of loneliness. We can conjure up poetic beauty, Hong suggests, through and with our deficits. And if we let it consume us, it can become our new reality. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Thank you for reading the 24th issue of Film Show. Shout out to Berlin bears.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.