Tone Glow 030: Our Favorite Non-Canonical Albums, 2000 (Part 2)

For a special issue, Tone Glow's writers highlight their 50 favorite non-canonical albums of the year 2000

Banner by Cassiopeia Sturm

For this week’s double issue, Joshua Minsoo Kim asked the Tone Glow crew to shed light on non-canonical albums from the year 2000—and they have more than delivered. Collected over these two issues are fifty albums which not only fall well outside the canon, but which question the very meaning of ‘the canon’ from a dizzying variety of angles. Is an album canonical if it’s admired by just a handful of critics, or if it gradually loses its critical and popular appeal? Should every great album be in the canon, or can they stand in opposition to it, and to the institutions which construct and maintain it?

Among the texts here, you’ll find arguments for all of the above, as well as historical studies, wry commentaries, and deeply personal reflections on what the year 2000 was like for those who lived it. Fittingly, these pieces do not converge around any simple or coherent narrative about what the year 2000 was or meant for music. Rather, they demonstrate just how stupefyingly broad, strange, surprising and fascinating the musical landscape can be at any given point in time. Among the releases gathered here are late-career gems from faded art world stars, critically reviled albums which spawned platinum singles, EPs from long-extinct micro-genres, albums which were popular and then weren’t, albums which weren’t popular and then were, one-hit wonders, anime soundtracks, CDr demos, and one video game. Among these fifty releases, there are almost as many perspectives on what it *means* to be canonical, and how that meaning can shift over time. There is also, simply, a lot of fantastic music.

A number of these picks surprised me; a much bigger number, I’d never even heard of. What unites all of them, beyond four numbers on a Discogs page, are the Tone Glow writers’ intelligent, informed, and above all passionate advocations for the music they love. In reading these two issues, I not only discovered a huge variety of new music, but found myself re-evaluating artists and albums I thought I had all figured out. This, perhaps, is the best argument against the very premise of a canon: truly great music writing can not only illuminate the past, but reshape it. —Mark Cutler

Jega - Geometry (Planet Mu)

While any new year is an event that we collectively agree to have special significance, for most of us reading, it’s hard to imagine a moment that felt more charged with possibility than the lead up to the year 2000. Any year’s renewal grants an opportunity for personal reinvention. But the promise of a new millennium seeded a collective sense that a profound and pivotal societal change was not only possible, but inevitable. We nervously anticipated what elements would provide the catalyst for this change, and nowhere was our gaze more centrally fixed than on the rise of digital technology as a looming presence in our lives.

Experimental electronic music was in many ways the perfect vessel to facilitate the expression of this alchemical mix of excitement, anxiety, optimism, and dread. From their earliest inceptions in the late ’80s and ’90s, Detroit techno, electro, and “IDM” had played with ideas of artificial intelligence, Afrofuturism, and alien contact—an expanding set of imagined futures from which we might examine the present. Unsurprisingly, many electronic musicians leapt at the possibilities afforded by the broadened accessibility of desktop PCs and the earliest digital audio workstations in the late ’90s. While the analog world was and remains rich with creative potential, the blank slate of software synthesis felt as profound a technological revolution as the transition from still photography to moving pictures. And as with early cinema, without the baggage of established workflows and production pipelines, the earliest forays into these new technological mediums were, by necessity, exploratory and experimental.

And the sonic landscapes of electronic music’s early digital era were aggressively experimental. Burned and sharpied CDs rotted in the sun and skipped to sculpt the art gallery-ready sound installations of Oval in the ’90s, inspiring entire genres of clicking and cutting devotees. Cornerstone ‘laptop music’ albums from Fennesz, Jim O’Rourke, and others, coalescing around Austrian label Mego, expanded the acoustic possibility-space of early digital music, while also challenging our conceptions of live electronic music performance. Within the thriving ecosystem of future-oriented electronica cultivated by labels like Warp, Skam, Schematic, and Rephlex, the releases of the ’90s were driven by the rough and biting sound of physical hardware. Perhaps no other artists were better situated to fully immerse themselves within the virtual canvas of software synthesis, navigate its uncertain dimensions, and demonstrate how far these tools could extend human creativity.

Manchester’s Dylan Nathan, recording as Jega, is one of the great, unheralded masters of this transition. Tracks like 1996’s “Phlax” rip with the dark energy of afterhours raves and warehouses, steel and concrete. They flex with physicality. But in 2000, the raw DNA of these early releases was fully virtualized to generate the hyperspatial landscapes of Geometry. With opener “Alternating Bit,” nebulous clouds of reverberation give birth to dramatic, detuned melodic lines, opening a gateway into an unexplored terrain of immense gravity and ambition. Tracks like “Syntax Tree” and “Recursion” refract natural harmonics across the frequency space, projecting them through stuttering rhythmic elements to produce a digital tapestry that is both disorienting and viscerally entrancing. On the title track, a sinewy melody winds its way between pads that alternately swell and flutter to heartbreakingly gorgeous effect. The album continues this fusion between the abstracted distillates of dial-up tones and circuit board bitcrush, coalescing to establish the album’s richly designed acoustic palette. Album highlight “Post Mid Arc” patiently builds a network of acrobatic melodic lines that travel through an unstable scaffold of shifting percussive elements, like so many tangled wires coursing through the claustrophobic alleys of Kowloon Walled City. The complex holographic textures of the album power down for closer “Subdivision Surfaces,” which offers a gentle decoupling from Geometry’s intricate interiors, its ambient harmonic figures falling at once as hard as footsteps in snow, and as delicately as the snow itself.

The first decade of the 2000s would see a renaissance in the “IDM” sound, with new artists and labels like City Centre Offices, n5MD, and Neo Ouija further elaborating on the sonic possibilities revealed by Jega and other electronic visionaries of the early millennium. The reverberations of this new sound would make their way into the wider cultural landscape, with Thom Yorke citing Jega specifically as an influence on Radiohead’s electronic makeover with their monumental Kid A. However, with time, the workflows for digital composition streamlined, and the explosive creativity that had emerged out of the millennial transition crystallized into more fixed forms and genre idioms. On a broader culture level too, the seemingly limitless potential for creativity suggested by the earliest incarnations of the internet and home computing fell far short of their initial promise. The unbridled diversity of our imagined virtual futures ultimately converged onto a banal singularity. With time, desktop workstations designed for creativity gave way to the consumption-oriented pocket devices that define 2020’s compulsively logged-on reality. Geometry thus serves not only as an artifact of the exciting transition of electronic music into the 21st century, but also as a prototype of more richly imaginative futures yet to be realized. —Emily Wirthlin

Listen to Geometry at YouTube.

ADULT. - New-Phonies (Clone)

In an era not long before all pop music would become synth-driven, a handful of musicians tried to fuse vocal-focused songwriting, riot grrrl energy, and vintage synths into something original and compelling. They largely failed, and for the most part, what was once called ‘electroclash’ is gone and thankfully forgotten. Only a few of those experiments are worth revisiting, and ADULT. were one of the first and best artists to be associated with the term. In the late ’90s, they put out a string of EPs of concise, stab-wound electro tracks, culminating with 2000’s New-Phonies.

The early ADULT. EPs are almost unrivaled in their flat, sterile minimalism, working almost exclusively with unadorned square and saw waves, and often foregoing traditional percussion in favour of ear-piercing clicks and staccato whines. Over these, Nicola Kuperus recites gothy, over-the-top monologues with an absolutely flat affect. The melodies are simple and hooky, but surprisingly undanceable. None of it should work—and on almost all of their subsequent output, it doesn’t—but on New-Phonies, Kuperus and Adam Lee Miller bend severe, minimal techno and pop songwriting into something wholly unique. “New Object” treats Kuperus’s voice itself like a percussive element, slicing her vocals up until each syllable pierces through the synth melody like a high hat. On “Don’t Talk,” an almost sub-audible bassline writhes back and forth as Kuperus explains that she wants to “just listen to you breathe… sshhhhhhhhhh.” Somehow, in her placid monotone, it becomes one of the more threatening lines I’ve heard on record.

Then there is “Hand to Phone.” Though a slightly remixed version from their Rescusitation CD is probably the duo’s best-known and most-loved track, the song actually makes its first appearance right here. Driven by an irresistible bassline and some of the band’s hookier synthwork, the song would almost be danceable, if it weren’t so chilling. Kuperus doesn’t speak, but sings at a single, unchanging pitch: “I look at you / I look at you cry / binoculars on my eyes…” Like all the best ADULT. songs, the lyrics give us only a few specifics, which nevertheless suggest that a terrible situation is unfolding. The addressee, we gather, is on the phone with a woman, who repeatedly asks “Why can’t I come over?” We don’t find out the reason why, but it’s probably not good for either of them.

ADULT., like most of the artists originally associated with ‘electroclash,’ quickly ventured into other, often more regrettable territory—terrible electropop, warmed-over disco, and the synthy, punky dreck we once called ‘dance rock.’ Yet in the present day, artists like Helena Hauff and Schwefelgelb have become staples in the Berlin techno scene by mining much the same sonic palette as ADULT. did twenty years ago. Whereas most electroclash now sounds hopelessly dated, straining at the limits of what could be accomplished on an iMac G3, ADULT.’s already-ancient synthesizers and phone-booth production make this music feel strangely out-of-time. Kuperus’s lyrics make no topical references, but rather seem to inhabit an ominous world of empty hallways and faceless figures. It’s a world I still enjoy visiting, though I know that I’m not welcome there for long. The lights are out, the door is locked, and the room is slowly filling with smoke. —Mark Cutler

Listen to “Hand to Phone” at YouTube.

*0 - [0,0,0] (Falsch)

When I think about electronic music from the late ’90s and early 2000s, I think of: dance music that feels effortlessly expansive, allowing you to feel comforted and weightless; various developments in electroacoustic improvisation across Europe and America and Japan; glitch and microhouse, onkyo and microsound. Much of it is exciting, pensive, experimental, intimate.

Despite the wealth of musical curiosity that underlines all this music, there’s only one electronic album (and one additional experimental album) from the year 2000 that consistently surprises me for how it makes me laugh: Nosei Sakata’s [0,0,0]. Hearing it for the first time was revelatory: it’s like stripped-down Ryoki Ikeda, its static-like pulses and white-noise drones both easy to follow and incredibly playful. It’s meditative yet goofy, charming yet austere.

Much of this album’s success comes from juxtaposition and tempo. When I hear the digital hiss of “[0,0,1]” intermingled with the sound of something akin to an engine, I feel like I’m constantly awaiting something big. When the track finally leads into the dotted dance of “[0,0,-1],” I burst out laughing: its simple blips and tones are slow enough that it feels like its taking the piss, but the arrangement is stimulating enough to keep me constantly engaged. Add in the way these sounds can physically affect my body—sometimes providing constant shivers—and I’m left with a huge assortment of reactions: I’m at peace, I feel giddy, I stay concentrated, I’m exhausted.

At 24 minutes and only released digitally as 160kbps MP3 files, [0,0,0] has the semblance of something minor. Still, there’s more to dissect if you wish: tracks with negative integers are “danceable,” while those with positive ones aren’t, and there’s a sense some correlation exists between a track like “[-1,0,0]” and “[0,0,-1].” But more than anything, putting on this album reminds me that musical experimentation can and should be fun; it’s just that making others feel that is another skill entirely. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Listen to “[0,0,1]” at YouTube.

The Aquabats! - Myths, Legends, and Other Amazing Adventures, Vol. 2 (Fearless / Horchata)

I won’t pretend there’s anything especially profound about this mid-career collection of rarities by The Aquabats, the whimsical and campy (yet resolutely hetero) spandex-clad ska-punks from Long Beach. I won’t suggest that that lack of profundity is especially deserving of praise or note. And admittedly it’s a stretch to consider this album “overlooked” when it contains two of the cult-favorite band’s most iconic songs “Pizza Day” and “Pool Party” (growing up in Southern California, even by the late aughts, these were two subcultural touchstones, apt for quoting with pre-teen friends).

However, being a collection of rarities, this album highlights The Aquabats’s skill for addressing the minutiae of daily life with not only humor, but a particularly sharp nuance and peculiarity. The band’s two studio albums prior had been primarily concerned with building the comic book world they would inhabit on stage and camera: monsters were tousled and martians were married in the spotlight while sweaters and skateboards sat in darker corners. But B-Sides and compilation contributions aren’t the space for myth building, allowing this 13-song collection to act as a veritable junk drawer in the most charming of ways, a testament in itself to the overlooked and non-canonical.

Occasionally The Aquabats’ appreciation for the banal events in life is juxtaposed by its musical accompaniment to play it for laughs. A raging rap-rock tantrum emerges when the singer has fallen asleep on his arm and, now “totally numb,” feels no pain. There, it takes all the moving and shaking of a Zach de la Rocha or Fred Durst to return feeling to the limb again. “I Fell Asleep on My Arm” is a light comedy, ironic and absurd, but admittedly saying little. Likewise, a pseudo-tango is passionately sung from the perspective of a baker who derides the loneliness of a bread oven but makes it clear with a ferocity: “I am the baker / I bake the cake / make no mistake, I / like to bake.” The humor here is faultless but simple.

On the other hand are the moments when quotidian topics are approached with sincerity and joy. The popularity of “Pizza Day” and “Pool Party” as third wave ska anthems in their own right speaks to this: straight-ahead pop songs which delve into the joys of adolescence with great attention. But even more particular in scope (and more profound for it) is “Dear Spike,” for which the lyrics simply consist of an endearing letter from a mail-order customer. Its winding chorus melody charts a sentiment that’s familiar and warm for many music collectors: “I just want to let you know / how faithful I am to you / I appreciate all the hard work / and kindness you put into / Dear Spike / what a task it must have been / Dear Spike / I’m so glad to know that you didn’t forget me.” There’s a reflection of community joy here in the harmony between the song’s mail-order subject matter and its straight-ahead, tastefully-composed backyard-ska drive.

The memorable and catchy “Worms Make Dirt” is oddly informative, telling of the production of soil and water cycles. It carries a hint of a smirk, but its composition and arrangement are so convincing in their educational-video style, that they portray a measure of real innocent joy. Following this joy, “Hey Luno” and “Danger Woman”—both fantastical with respective themes of a flying horse and a globe-trotting super hero—are deeply celebratory with considerable sentimentality. These songs give credence to The Aquabats as a vehicle for escape, one which truly fights cynicism and fatigue, giving real pause for lost feelings, moments of youthful joy, to run free, unfettered. —Leah B. Levinson

Listen to “Dear Spike” at YouTube.

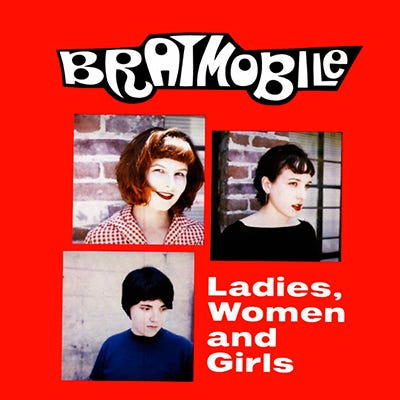

Bratmobile - Ladies, Women and Girls (Lookout!)

Is the riot grrrl dead or is she just sleeping? The ’90s feminist, punk, and often deleteriously white-dominated movement petered off by the early 2000s, but the band Bratmobile persevered, at least for a bit longer. Born in 1991 from the grungy, dirty, girls-to-the-front sound taking over the Pacific Northwest and Washington state, Bratmobile released their most famous album, Pottymouth, over the next three years, only to break up in 1994. Eventually, they got back together, and released their second album Ladies, Women and Girls in 2000.

Ladies, Women and Girls is just as pissed off and energy-driven as the classic Pottymouth, but it comes with the added bonus of its musicians having more experience; it’s more polished and it’s excitingly, infectiously pop-minded. “Well You Wanna Know What” couples a snotty “fuck you” vocal delivery with pretty, subdued harmonies, “Gimme Brains” reminds us that boys drool and are “good for nothing” through a strident, off-kilter but catchy vocal melody, and “Girlfriends Don’t Keep” experiments with making pared-down guitar ballads into something slightly sardonic and impenetrable. On most tracks, the drums are fast and hard, the guitar goes scuzzy and low, and vocals are the musical equivalent of blowing a really big bubblegum bubble and popping it in your boss’s face. It’s absolutely obnoxious and off-key.

My friend Elizabeth said that riot grrrl wasn’t about finesse or technique, it’s about vibes. Ladies, Women and Girls knows its vibe. The vibe is dancing poorly in a basement, drinking a shitty beer out of a flimsy, shitty plastic cup and sticking it in the beams of the basement ceiling when you’re done drinking it. You go to the mini-fridge to get another beer while your clothes develop wet patches, sticking to your sweaty skin. One of the straps on your spaghetti strap tank top is falling off your shoulder, but you don’t care, you just keep swinging your clumsy body to the music as you head towards the fridge. The vibe is imagining yourself slowly licking a firecracker popsicle in front of your 7th grade math teacher. He always looked at you weird.

The vibe is the lyrics in “You’re Fired,” which at one point say, “You’re scared of girls just taking things / In their hands and making things / All for themselves and not for you / Yeah we’re aggressive, but so are you.” Riot grrrl isn’t sweeping America the way it once was, but the societal ills that motivated its creation are alive and well—the violence of sexism and the very diverse, nuanced fears that all women experience at one point or another in their lives. Sometimes you get tired of bleeding and you just want to rock. The riot grrrl lives forever in you. —Ashley Bardhan

Listen to Ladies, Women and Girls at YouTube.

Saturday Looks Good To Me - Saturday Looks Good To Me (Hereforeveralways)

I love it when a pop album can make you feel pleasant and dejected in the same breath: a pill of disenchantment coated in sugar. The self-titled debut from Saturday Looks Good To Me, masterminded by the prolific Michigander songwriter and fellow music-journo, Fred Thomas, goes down incredibly easy as the sounds of nearby Motown introduces SLGTM as something old and new.

The heavy influences of ’60s pop initially softens the emotion of crisis, but then you remember the ’60s was no dreamier than 2000, regardless of how bright the horns sound and how playfully the basslines skip along the tracks. Then the heavy fuzz of tape distortion reveals the underlying existential anxiety that permeates the entire record. You’re bopping your head along with the beat, and then a lyric will make its way to your ear: “I find myself amazed at how long things can stay in the same unpleasant state,” or, “Running away from a consumer-age nightmare of capitalism-based warfare into air more breathable.”

This aural representation of American rot resonates loudly on songs like “Everyday,” where the first of the above lyrics can be found, and “I Can’t Think About Tomorrow,” which veers into sound-collage, the vocals ekeing their way above poppy instrumentation that loses its structure and clarity as the volume grows. It’s disintegration presented through stasis; these are summery, escapist pop songs that serve as a reminder of how slowly things change, if it all. 20 years on, it feels like the disheartening messages sunken beneath the vibrant pop and lo-fi hisses are as relevant as ever. There’s a timelessness to Saturday Looks Good To Me—sonically for the better, thematically for the worse. —Evan Welsh

Listen to “Everyday” at YouTube.

William Parker & The Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra - Mayor Of Punkville (AUM Fidelity)

Jazz music, what Fred Ho might call “African-American vanguard music,” or just “The Music,” is an act of protest. It is a rebellion against every wrong perpetuated by capitalism and imperialism. To create this music is to fight for a better future. The Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra was a revolutionary group led by the great William Parker that made music that is all of the above and more. The structure of the orchestra itself seems like a direct response to the rigid hierarchical nature of established “art music,” which often takes more cues from capitalism than it would like to admit. The seventeen members are split into seven stations: trombones, trumpets, baritone sax/tuba, soprano/tenor sax, alto sax, drums, and bass. William Parker leads with a rough score, closer to the graphic scores of Braxton than standard notational scores, which drives the pieces forward with a shared initiative. Unlike a traditional orchestra, however, each station is encouraged to improvise, or “self conduct,” with the one rule being “the moment always supercedes the preset compositional idea”: a structure of unstructure.

The unique setting of The Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra leads to innumerable moments of improvisational brilliance that simply wouldn’t be possible in a traditional setting, jazz or otherwise. Sections are free to do as they please while every other section is working on the main ideas of the piece, adding their own distinct voices to the music to build something no one person could ever hope to compose. The music is often a chaotic mess of multiple leading voices talking to each other but that chaos always comes from a shared idea and always leads back to it. On tracks such as “Interlude #7 (Huey’s Blues)” this is more laid back and it’s easy to forget there are 11 different people on the piece.

The smaller mood pieces are overall brilliant and help to make a 140 minute album much more manageable, though it’s during “Oglala Eclipse” or the sprawling 30-minute epic title track “The Mayor of Punkville” that the true genius of The Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra shows itself. The mainline composition is simple and built off of a single melodic phrase repeated over the 30-minute runtime which gives ample room for improvisation. Over the course of this piece this phrase is tossed around, distorted, and at times completely covered up by a chaotic mess of free jazz-like noise, but every moment is dedicated to the piece and its progression.

Like Fred Ho, William Parker repudiates the label of Jazz, instead using the phrase “universal music” to describe the music of The Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra. Regardless of what you would like to call the sounds on these two discs, they are revolutionary in every sense of the word and mirror the ideal world we are striving towards: everyone working together to build something meaningful, with enough room for our individual voices to shine, using our own eccentricities as a strength to create something special. Twenty years ago, William Parker and the Little Huey Creative Music Orchestra got together and made something beautiful. Now is the time for us to follow suit. —Alex Mayle

Purchase Mayor of Punkville at Bandcamp.

Various Artists - Psychological Operations In Guerrilla Warfare (Rice and Beans)

In 1984, the Associated Press confirmed the existence of Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare, a CIA instruction manual for the Contras, a right-wing Nicaraguan rebel group. The manual offered tips on terrorism, from assassinations and torture to PSYOP violence; in 1986, the International Court of Justice found that, through the manual, the US had encouraged human rights violations.

The Miami duo Steven Castro and Rick Garrido took the manual’s name for a debut compilation of artists on Rice and Beans, a sublabel of their broader Beta Bodega Coalition label. R&B and BBC were notable not only as an early American hub for the kind of adventurous electronic music more often produced in Sheffield and Frankfurt, but for signing artists of color.

Psychological is political in content—news accounts of Contras’ violence form a hidden track, “Transmito 001” by La Mano Fria & VB, chopped and cut across winces of white noise—but also in form. El Brujo Oscuro’s “Macumba” is an occult gem in which bleeps glint within uncertain hazes; it’s as hypnotic as Throbbing Gristle or Voices from the Lake, but free of the former’s fascist rubbernecking and the latter’s numb escapism. It’s trance as resistance. Romulo Del Castillo appears as Patcha Kutek and Takeshi Muto, offering two sets of crunch-and-chimes as elegant as any of the hundreds of people then working through their Tri Repetae obsessions. Yet “Earwig” proves the bass ballast of such tracks is rooted in digital dub, and “Liquiano” lets glitches shimmer like marimbas. Techno began as Black protest music; electronica (or whatever this next movement was) made things complicated by injecting a rhythmic and textural dexterity that was sold by white labels like Warp as “artificial” but was actually Latinx and diasporic. Some twenty years on, R&B and BBC should be remembered as short-lived but crucial counters; moreover, they were instigators. Each copy of the compilation came in a plastic bag with silk-screened artwork and a grain of rice and single bean. For them, this was DIY sustenance. —Jesse Dorris

Purchase Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare here and here at Bandcamp.

Alexander Brandon / Michiel van den Bos / Dan Gardopée / Bryan Rudge - Deus Ex: Game of the Year Edition (Eidos Interactive)

You feel alone yet wanting to advance to the truth, you feel desolation and sorrounded by unknown forces yet you know your goals, is the music that starts it all, the music the more you hear if you replay the game, also the one that is soft enough to not be distracting yet haunting enough to keep you on the edge of what's to come. That’s my feel of the Liberty Island music :P

—Nachovyx (YouTube)

At the end of the game—(prior to which trillionaire Bob Page, leader of the Majestic 12, weaponizes a deadly virus (the “Gray Death”) that ravages the planet; corporation VersaLife, the manufacturer of the only vaccine, “Ambrosia,” available only to the global elite, is revealed to have manufactured the virus too; the people rebel, forming the National Secessionist Forces (NSF), who hijack shipments of “Ambrosia” and wage guerrilla war against the UN’s counter-terrorism task force, UNATCO; and you play as JC, a UNATCO agent who defects to the NSF)—a renegade hacker from Hong Kong named Tracer Tong, your trusted guide and advisor throughout, asks you to destroy the entire global communications and nanotechnology apparatus, housed at Area 51, so that no one can use it for evil: by doing so, you would usher in a new Dark Age.

TONG

They dug their own grave, JC. We're going to eliminate global communications altogether...

A problem, JC. Rioting in Manhattan has been so bad that the city’s fallen under martial law. At this hour the troops will shoot on sight, and I'm showing several guards and a robot near the hotel. Keep your head down.

Ah-ha. A trellis. You could climb onto the roof and avoid the security. Never depend upon weapons and high-tech when there is a simpler solution at hand.

A bone-dry drill crash cymbal ushers in a rolling MIDI symphony, cut and crossed by static jungle rhythms and the plastic boring of digital saxophones and stilted pizzicatos—wind as filtered, transmitted white noise crystallizes into encrypted fog which fills the 4am chillout room of the only club in New York still open under martial law—in Hong Kong, a plucked electric guitar preset performs a stirring rendition of an Oriental melody passed down from dead generations, past iterations of the Asian Hacker in the Asian Hacker City, simultaneously the cold, brilliant vanguard of technological revolution and the threat of a prehistoric, undifferentiated, ‘primitive’ mode of being:

TONG

A dark age, an age of city-states, craftsmen, government on a scale comprehensible to its citizens...

You can get anything you want for two credits on the black market in Asia.

Languishing Spy Movie breakbeats and acid squelches melt into scraping clangs and splintered brass fanfares—punctured by a SAVING—as you pick the lock to the main terminal, gain access to the central security system, and turn the fortress's turrets against its own mechanized guardians:

TONG

See how easily our technologies turn on us? The more power you think you have, the more quickly it slips from your hands.

—a peak rave piano riff locks into repetition as you make the decision to plunge the world into a new Dark Age—

Or not.

“30 Dx Club Mix” kicks up the BPM, carries you into the future—one of your own making. It's tempting to call all of this ^ a Precursor, a Predictor, a Prophecy (in the plot—need I elaborate? in the music—we can hear everything from Chief Keef's most blown-out RPG beats to many well-worn strands of 21st century club music)—but that would be an oversimplification. Deus Ex is just a distillation of what was already there in 2000—the looming ‘threat’ of ‘terror’ and its terroristic counterpart, ‘counter-terrorism’; the contradictory fear and awe of ‘technology’; deadly diseases with no cure; and the quickly vanishing motifs of club music's most revolutionary heyday, by 2000 largely hardened and ossified into robotic, juggernaut parodies of their searching, spiritual predecessors. Jungle → drum ‘n’ bass. Following this latter trajectory, the main composers (Alexander Brandon, Michiel van den Bos) released a ‘remixed’ and updated version of the OST in June 2020 for the game's 20th anniversary. But any attempt to bring this music 'to life' only deadens it—the flatness of the original, limited to 1.5MB per song, was its strength, its unique quality. This is like "Faneto" backed by a live orchestra: maybe a treat for a fan, but a loss of everything that makes it what it is. Remix aside, the original is certainly uneven and overlong, as most soundtracks are—but the combined, overpowering effect of the whole package is too forceful to be denied. Caught in the dizzying mystique of its universe, it’s sometimes tempting—and fun!—to falsify history and believe that Deus Ex really did predict it all…

TONG

The sewer leads straight to the water. You can reach the ship this way if you don’t mind swimming.

Listen to Deus Ex: Game of the Year Edition at YouTube.

The Pancakes - Les bonbons sont bons (Rewind)

The 1997 Asian Financial Crisis came at the worst time for Hong Kong. When the Handover occurred on the first of July, some anxious natives reassured themselves that the economic and cultural significance of the city would protect against assimilation into its new administrator, the PRC. On the very next day, the government of Thailand devalued its own currency, setting off a financial shockwave that put the brakes on the East Asian Miracle, and, at the end of October, caused Hong Kong’s stock market bottom out at 40% from its peak value. On the cultural front, the hard times knocked Hong Kong’s prized Cantonese language music industry flat on its back — by 2001, the legendary record label Capital Artists, former home of Anita Mui and Leslie Cheung, had seized to record new music. The wave of downsizing and closures would tumble Cantopop from the Sinosphere’s most beloved genre to a regional player in the shadow of its Mandarin-language counterpart. The city’s sense of identity was badly shaken.

It was in the middle of all this that Dejay Choi’s cutesy toy pop resonated with an unexpectedly large audience. Despite dropping to no fanfare, her first album under the moniker The Pancakes, les bonsbons sont bons, sold ten thousand copies, an eye-popping number for the city’s underground indie scene. In the coming decade, her work would only increase in stature, as local bands like my little airport, 22 Cats, and The Marshmallow Kisses tilled the same twee emotional ground that she first cleared.

A collection of Dada lyrics set to deliberately garish production seems like the antithesis of a crossover smash, but les bonsbons captured a particular national mood, which also manifested itself as ephemerality among the city’s conceptual artists and kidult culture among its consumers. The album’s achievement is how it hits upon the appropriate musical register to delve into Hong Kong’s turn-of-the-millennium psyche. les bonsbons dedicates its entire 18 minute runtime to sustaining one emotion, cute, and in the process develops all of that aesthetic’s complexity. The emotion’s complicity in power relations (cute things are subordinate), market forces (cute things want to be possessed), and even repressed aggression (cute things are pathetic) allows it to ring with meaning far beyond what one might expect: the europhilic notes (the French title, the English lyrics, the all-Swedish song “tre pepparkaksgubbar”) touch upon Hong Kong’s lost colonial status, the evocation of children’s music reflects the economic vulnerability of the city’s youngest generation, the dissonance between pitchy vocals and canned synths reflect a certain emptiness at the heart of Asia’s financial capital. Much like how the emotional economy operates, les bonsbons’ critque works in the borderland between feeling and meaning, but the album does occasionally stop its babbling and give the game away, like in “stupid star,” which sneers at a man “Driving an expensive car / … / Disguised in designer clothes.” In the lurch of a global financial meltdown, Deejay Choi harnessed the power of small feelings to capture the moment in all of its dimensions. Artists looking to tackle our current economic clusterfuck, take note. —Adesh Thapliyal

Listen to Les bonbons sont bons at YouTube.

m-flo - Planet Shining (Rhythm Zone)

m-flo prove to be incredibly prescient on their debut album, Planet Shining, as they prepare for the arrival of a fresh new decade in J-pop. The members of the hip-hop trio themselves are creative egos who each represent a different booming scene. Rapper Verbal lays down East Coast backpacker-isms — a big stylistic base for the then-rising wave of commercial rap in Japan — and singer Lisa joins the class of artists such as Crystal Kay and Hikaru Utada, who would catch Japanese R&B up to speed later in the early ’00s. The two vocalists are held together by producer Taku, who imports international dance rhythms of hip-hop, drum ‘n’ bass and 2-step to build a new kind of swing for J-pop.

As these adjacent lanes all intersect, Planet Shining resembles more a stylistic collision than a clean fusion. While m-flo together define their base aesthetics of hip-hop, dance and R&B, the trio don’t completely sand away the lines bordering the different genres. This, however, only make the creative process more visible as they adapt to new ideas. At its best moments, they seem to write the future in real time: Lisa’s effortless glide over the drum ‘n’ bass beat of “Ten Below Blazing” paves the way for R&B singers such as BoA and Kumi Koda, showing how to ride more intricate dance rhythms. Even if other experiments end up sounding rather dated now, such as the Roots-meets-Aaliyah R&B of “Chronopsychology,” it still remains a bold, novel exercise that expands their palette. Above all, the album boasts a musical adventurousness that also taps into the general attitude of J-pop overall during the turn of the century, and in proposing several new combinations on Planet Shining, m-flo built a foundation for new pop music to come. —Ryo Miyauchi

Listen to “Planet Shining” at YouTube.

Lil Wayne - Lights Out (Cash Money)

Looking back at the legacy of Dwayne Carter Jr., most critics omit his second and third albums from the Weezy canon. For the most part, they’re right to do so. Neither of the records match the pure energy and enthusiasm that shone through on his debut, released when he was just 17, or on his earlier contributions to Hot Boys tracks. On those first releases, he was a phenom, a scrappy 14-year-old from Hollygrove fighting to earn his place in a group of older kids. His verse on “Back That Azz Up,” the lead single from Juvenile’s massively successful 400 Degreez, introduced his prematurely raspy voice to the world outside Louisiana, and his first solo album, The Block Is Hot, was his coming out party as a fully-formed, multi-tooled rapper, an agile lyricist with a dirty mind and a knack for unusual wordplay.

Lights Out was released in December 2000, three months after Carter’s 18th birthday, was largely seen as a letdown, an unorganized album full of unimaginative bars, underdeveloped tracks and unfunny skits. A legal adult now, he was no longer subject to special treatment, and critics took Lights Out as a sign that he lacked the maturity of his fellow Hot Boys, especially Juvenile, who was seven years Wayne's senior and had just released what remains his magnum opus. It’s true that, in an era when rap albums were expected to tell stories, Lights Out has few compelling narratives to latch onto, other than the rags-to-riches Bildungsroman built into every track. But while Lights Out is far from Lil Wayne’s best album, it shouldn’t be completely overlooked. If you sift through the undeniably bad tracks, there are some undeniably good ones. There’s “Everything,” a plainspoken but powerful tribute to his recently deceased step father; “Grown Man,” on which he deals with his newly official adulthood, a concept he finds ironic, since he’s been supporting his family since he started puberty; and “Shine,” a bright, bouncy Hot Boys posse cut that’s as purely fun as anything in Carter's catalog. There’s also consistently great, golden-era Mannie Fresh production, culminating on “Lil’ One,” for which he lays out a smooth R&B sample indebted to the beats of Andreao “Fanatic” Heard and containing the DNA for Pharrell’s mid-aughts mega-hits.

If nothing else, Lights Out and its follow-up, 500 Degreez, should be seen as crucial stepping stones from the unbridled eagerness of Tha Block Is Hot to the cold-blooded cockiness of Tha Carter, the album that cemented Wayne as New Orleans’ prodigal son. 2000 was a year of growing pains for Carter, a time before the superstardom and egomania that aggrandized his larger-than-life second act, and the label disputes, codeine addiction and out-of-touch political statements that have marred his third. Lights Out is the product of a kid on the verge of a meteoric rise, a generational talent who hadn’t yet forgotten where he came from. —Raphael Helfand

Listen to “Lil’ One” at YouTube.

Hanayo - Gift (Beat)

Even C.C.C.C. have seen more of a critical renaissance than Hanayo among those of us who consider ourselves an audience for “extremity” in music, which is a strange oversight to me, as the ways in which her work intertwines notions of commodification, the engagement of the body both as a vehicle for voice and a body in itself as a central obsession of her artistic project, and her reverent warping and decaying of traditional musical forms through the lens of overclocked contemporary electronic soundscapes, feels very momentous and ever-present.

Gift, being explicitly premised on communal collaboration across all its tracks, with each track showcasing the strengths of its chosen collaborator in concert with Hanayo’s ever-malleable and -mercurial voice, feels deeply illustrative of just how wide-reaching Hanayo’s shadow over the field of electronic noise remains, even as it’s been forgotten; the credits feature names as disparate as Terre Thaemlitz and Rocko Schamoni, as well as longtime friends like Merzbow, rubbing cheery shoulders with each other in joyful screeching. Her omnivorous willingness to work together to make something compelling with whoever has an interesting enough idea to contribute makes for an album that feels like a dense thicket of thornbushes aglow from the inside with buoyant light; dense sheets of monotonous screeching feedback beneath squirrel-pitched caterwauling slot comfortably aside tempo-swapping pieces of chopped-up avant-pop that sounds not unlike a marching band being recorded as it drowns underwater and Hanayo mumbles what may or may not be some sort of prelingual lullaby to the damned participants.

Gift bursts with as many tantalizing, horrifying possible permutations of itself as it has participants, a testament to the creative force behind it. Those of us who cling fondly to our memories of discovering the Björks, Deerhoofs, Fiery Furnaces, and even SOPHIEs of the world would do well to bend our ears to hear what Hanayo was willing to speak into being, here and elsewhere. —Tara Wrist

Listen to Gift at YouTube.

Peter Brötzmann Chicago Tentet - Stone/Water (Okka Disk)

The opening of the 21st century proved to be a very ambitious year for German saxophonist and composer Peter Brötzmann, who was on the heels of releasing three back-to-back albums with Die Like a Dog quartet (with Toshinori Kondo, William Parker, Hamid Drake), and countless smaller collaborative trios. On this particular encounter, he revived his supergroup once more for two recordings in 2000, Two Lightboxes and Stone/Water. Stone/Water was recorded live at the 16th Festival de Musique de Actuelle Victoriaville in Victoriaville, Quebec, Canada on May 23, 1999, which included a tentet of master improvisers from all around the world.

Remarkable in comparison to his seminal debut release, Machine Gun, Stone/Water graphs out an absolute tour-de-force in virtuosity, performed by free improvisers in the top of their class. Dynamic and punctual, delicate and absurd, one never loses sight that this is a Peter Brötzmann project: the set immediately erupts into absolute chaos, an opening synonymous of a man who has witnessed the turmoils and devastation of two world wars. Complex and engulfing, the horn section screams in a cacophony of entanglement before settling back and providing space for the two double bassists to deliver the first of their two soliloquies. Ken Vandermark allures the audience as the two drummers provide a palette of distinction and continuity; Toshinori Kondo’s solo on trumpet and electronics is intimate, constructive, and balanced, as the reoccurring barrage of explosive ensemble hits provided contrasting accompaniment. It’s a standout performance of lulls, shock, and amazement.

Stone/Water was produced by John Corbett and Peter Brötzmann, and the magnitude of their collective fingerprints on this production is without question: the audibility is pristine, the arrangements are guild to fervor, and the clarity through chaos is impeccable. It’s an amazing snapshot of the sheer determination by the then-57 year old master of free improvisation. —Jamison Williams

Purchase Stone/Water at Bandcamp.

Wadada Leo Smith - Reflectativity (Tzadik)

In the year 2000, Wadada Leo Smith released two albums for John Zorn’s Tzadik label: Reflectativity, the work of a trio with pianist Anthony Davis and bassist Malachi Favors, and Golden Quartet, which expands the same line-up to include Jack DeJohnette. I’d rank DeJohnette, best-known for shrapnel-cymbal work on the Miles Davis fusion albums (he’s basically worked with everyone, their spouses and their children, quite literally), as one of my favourite jazz drummers, so it’s not lightly that I say that he is not missed on Reflectativity. With no groove ‘tethering’ these three musicians, their improvisations seem ‘freer’, and on the title track, Anthony Davis’s playing takes up an extremely percussive quality to make up for the lack of drummer.

Reflectativity revisits the album of the same name by Wadada Leo Smith released in his early years, which also featured Anthony Davis on piano (Favors is the new link here, replacing original bassist Wes Brown). This explains the dynamic between Davis and Smith, especially on closer “Hanabishi,” where it sounds like they’re having a friendly conversation as Smith wavers his notes as quickly as Davis flutters with his. The album expands the original’s two long cuts with “Hanabishi” and a short piece titled “Blue Flag”; stacked against these longer compositions, “Blue Flag” might seem superfluous, but it has an interesting cascade of plucked notes from Favors and the very Debussy-like climb of chords near its end from Anthony Davis.

Despite being known for his difficult, sometimes incredibly minimalistic compositions, Wadada Leo Smith has always been a classicist at heart. To wit, three of these songs are tributes to heroes, sidemen, friends, and the same goes for Golden Quartet as well; the title track is subtitled '“a memorial for Duke Ellington” while “Blue Flag” is “for Anthony Davis.” In an interview, Leo has said, “The artist I most dream about, other than Duke Ellington, is Miles Davis,” which might raise an eyebrow, but I hear Miles Davis plenty in Wadada Leo Smith’s playing: the effortless cool, the incredibly striking tones, and plenty of melody in his pocket, whenever he decides to go for one. —Marshall Gu

Reynols - Blank Tapes (Trente Oiseaux)

I think it would be difficult for a dedicated fan of experimental music to somehow be unaware of Reynols. Originally dubbed the “Burt Reynols Ensamble”—which reveals their true namesake, and was also perhaps the first public instance of member Anla (Alan) Courtis’s penchant for subtle misspellings—the Buenos Aires trio redefined what “experimental” could and should mean. From infamous, confrontational releases like the 10.000 Chickens’ Symphony 7” and modest experiments such as Computer Music to collaborations with Pauline Oliveros and Dan Warburton, Reynols consistently demonstrated that gimmicks and gags are not things that should be avoided at all costs, instead making their compelling case for not just not taking art too seriously, but abandoning the idea of “seriousness” altogether. Their distinct modus operandi is not an identifiable, consistent style, but instead purely takes the form of their literally-anything-goes approach.

2000’s Blank Tapes is another infamous release from the band, probably because of its apparent conceptual obstinance. Its entire duration is solely sourced from actual blank tapes (didn’t see that one coming, I know), a premise that’s inherently prickly since it pokes at the notoriously adamant conception of “actual music” that has been so deeply ingrained in so many individuals. Many negative reactions I’ve seen focus not on the actual material of the album, but instead its general identity, arguing that the sound of tapes with nothing on them could never be something worth observing. What a tragedy to submit to such closed-mindedness—for Blank Tapes is most definitely deserving of any attention one is able to give it. Make it past the deceptively minimal opening track, which appears to consist of complete silence unless you crank the volume and discover the hidden but unmistakable hiss of empty tape, and you find yourself submerged in a fascinating and immersive environment of soft fuzz beds, microscopic air currents, purposefully amplified emptiness.

As someone who has found themselves experimenting with the sonic properties of blank cassettes on his own, and who has observed the same predilection in countless other musicians, Blank Tapes was probably an inevitability for Reynols, a group that already began to plunder the deepest depths of unusualness and unintentional musicality before producing it. The six untitled tracks bear none of the colorful brashness that many associate with the band, instead following the lead of the minimal cover design into subtle, considered compositions with just enough intrigue and perceived intention to keep things consistently interesting without abandoning the mysterious, stubbornly apathetic ennui of soundless magnetic tape. Compared to the first track, the second and third are much louder, more dynamic, and more thoroughly engrossing, but it’s actually the subdued fourth piece that might be my favorite, due to its combination of both purposeful amplification and emphasis on absence. This only makes the entry of the fifth composition more startling; it’s easily the loudest and most conventionally noisy of the six, somehow sounding more deliberately crafted than many of the most impressive examples of wall noise.

By now it’s probably clear how Reynols was able to make Blank Tapes work as an album of music; there isn’t some special, unholy set of expertise they had to tap into to coax musicality from such unmusical sources, they’re simply just talented, intelligent musicians and artists. Once again, an ostensible gimmick is entirely assimilated to form a fully-realized style that remains distinctly Reynols-esque—however, in my opinion, this is the absolute best thing they ever made. —Jack Davidson

Listen to Blank Tapes at YouTube.

Nicola Conte - Jet Sounds (Schema)

In the year 2000, Nicola Conte’s Jet Sounds was cheesy and overplayed, a watered-down late entry into the lounge revival that was explored in much more interesting ways by Stereolab, the Pizzicato Five, and Pink Martini. Its lead single “Bossa Per Due” was everywhere, including car commercials and, later, underwear commercials. The album’s mixture of smooth jazz, bossa nova, samba, and easy listening telegraphed an aspirational cosmopolitanism that had nothing to do with the average person’s life—which made it perfect for commodity fetishism but eminently hateable to people like me.

Alright but so in hindsight I was wrong. Click play and find out why. It just simply goes. You can’t stop it. Each song is pitch-perfect, as if designed in a lab to excite the pleasure centers of the brain. What used to be overplayed is now nostalgic. What used to read as watered-down registers now as unabashedly—and effectively—poppy. What used to be cheesy is still cheesy, but now that’s a good thing. The album’s culture-hopping cosmopolitanism, formerly the domain of yuppies, now recalls a pre-9/11 era when you could jump on an international flight with little bother. It is called Jet Sounds, after all. From my vantage point (not having left town since January, not having left the apartment since last week) it sounds almost utopian.

Of course the album wouldn’t have worked for so many people twenty years ago, and it wouldn’t be working so well for me now, if Conte wasn’t extremely good at his job. He combined traditional styles with modern production tricks to make the whole sound timeless, and then added earworm melodies via his not-so-secret weapons: beautiful vocals from Gabriella Schiavone, Manuela Ravaglioli, Paola Arnesano and Stefania Di Pierro. The whole thing is perfectly mixed and mastered, with not a shaker or a tabla out of place. It’s not original music, per se. Listen to “Forma 2000” or “The In Samba” and there’s an uncanny feeling that you’ve heard the same melodies somewhere before in another context. But that’s not really the point. The point is the joy in playing these styles very, very well—undeniably well—and showing the audience how much fun it can be to dip one’s toes into samba or bossa nova or mambo. In 2000 I used to scoff and call it “tourist music.” But oh to be a tourist in 2020. —Matthew Blackwell

Listen to Jet Sounds at YouTube.

Plus-Tech Squeeze Box - Fakevox (Vroom Sound)

Hailing from Tokyo, Plus-Tech Squeeze Box sound like the musical equivalent of a zany Japanese game show. They’re unmistakably the product of fevered imaginations—there’s no end to their ideas, no concept too minuscule to be included on Fakevox—and it’s no wonder that that their music has been used for such disparate intellectual properties, from Pucca to Powerade to the Spongebob Squarepants Movie. You can’t contain such unrestrained minds to genre limitations and instrumental rigidity; it’s Shinjuku style at its absolute best.

Plus-Tech Squeeze Box have a dedicated relationship with sampling. Even with Junko Kamada’s whimsical vocals and joie de vivre, you can’t help but notice the sheer mayhem pouring out of every weird organ riff or radio static pore. The intro track alone samples a Colgate-Palmolive commercial, the Howdy Doody theme, and Lena Horne. Plunderphonics might never be this fun again. And then there’s “Test Room”. You get the sense that Tomonori Hayashibe and Takeshi Wakiya tried to cram every sound they’ve ever heard or ever will hear onto this song. It’s no wonder the track doesn’t have a WhoSampled page.

Their big secret, though, is that they’re actually a power-pop band. Not of the Cheap Trick / The Cars variety, but still catchy and melodious to fit the framework. Listen to the buoyant pacing of “Early Riser”, an auditory carnival, and marvel at how much joy Plus-Tech is able to wring from 2 minutes and 47 seconds of music. Or gaze into the anime title sequence majesty of “Rocket Coaster,” and feel the contentedness wash over your eardrums. It’s a pleasant contrast to their other releases, where they go full-throttle freneticism constantly. This pop sensibility in tandem with their wildest impulses makes Fakevox diverse and full of quaint moments.

In an era of post-pharmaceutical remedies and a deluge of therapeutic options, Fakevox exists as a natural solution to serotonin depletion and continuous anxiety. It’s a contagious record, pumping the listener full of joy and daring them to not be swept up by the sheer enthusiasm that surrounds every track. It’s the musical equivalent of that Matsuoka Shuzo “Never Give Up!!!” meme, acting as a positivity injection in the most dire of times. Life got you down? Plus-Tech Squeeze Box unflinchingly, unwaveringly, will get you back up, no questions asked. —Eli Schoop

Listen to Fakevox at YouTube.

Cymbals - That's Entertainment (Invitation)

2000 was a great year for the short-lived band Cymbals. While just active for seven years, the third wave Shibuya-kei group put out a plentiful number of great albums, and this year saw the release of both That’s Entertainment and Mr.Noone Special. While both albums are good, I see myself coming back to That’s Entertainment more often.

Self-described as “a cute and quirky band, but punk,” Cymbals’s style is a fast and energetic pastiche of everything upbeat and pop. Asako Toki (who later became successful as a solo artist) delivers her vocals with an effortless and carefree quality to them, even the explosive chorus on “What A Shiny Day” feels as breezy in spirit as the faint whispering on “Rain Song.” Even the three skits titled "So You Want To Be A ROCK'N'ROLL STAR" with goofy scripted street interviews asking about the band in English are genuinely funny in their absurdity.

The mood of That’s Entertainment is easily summarized by Toki’s unwavering lyrics on “So What?”—“I know I go everyday as I like it, as I feel it; I know I go everyday as I like it, at my own pace.” It doesn't feel like a major label debut, it's just as blithe like the best independent pop music. —Rose

Listen to “Rain Song” at YouTube.

The Aislers Set - The Last Match (Slumberland)

Indie pop doesn’t have rockstars, but for a certain generation of indie pop fans who came of musical age in the late ’90s, San Francisco quartet Aislers Set may as well be the Beatles and their 2000 release The Last Match is their whatever Beatles record is your unproblematic favorite. Though indie pop was a transatlantic love affair, only Aislers Set managed to tie up both the American and British iterations of the genre in a way that didn’t feel derivative of either: the sunny melodicism and heartfelt sincerity borrowed from the Sarah Records crowd and the blaring, blown-out atmospherics from the punky Americans who nonetheless shed tiny tears over the Orchids. Nowhere did Aislers Set do so more effortlessly than on The Last Match, a perfect pop record with its fingers in every decade’s flaming pie.

Though it certainly shambles along in the genre’s unstudied manner, The Last Match has an air of crafted sophistication that contributes to its durability when so many indie pop records of its era haven’t languished exactly, but haven’t really increased in stature either. By contrast, The Last Match sounds timeless—as apt to be a lost ’60s Brill building classic as it is some forgotten ’80s jangle underground gem or even some weird ’90s indie garage project thing made by people who got tired of screaming about sexism or whatever in their more “serious” bands. Yet there’s nothing unserious about The Last Match.

Sonically a very happy record, with a plethora of playfully holiday-ish sounds (handclaps! sleigh bells! Farfisa!) and lyrical turns-of-phrase that trail into “ba ba ba’s” and “la la la’s,” The Last Match is thematically rather dark, just as much as concerned with the toll taken by separation and anxiety as is with the joys of riding public transit in pre-tech dystopia hell world San Francisco. You should really listen to the whole thing, but if you’re a tourist in this place, try “The Red Door,” a song that makes a game of listing all the good things in life that still can’t replace the best thing in life (you), and wait for the moment mid-way through when the song cracks open and organ line skips, the drums pound by a heartbeat, and the guitar feeds back with a squeal that hurts so good. —Mariana Timony

Listen to “The Red Door” at YouTube.

Vladislav Delay - Entain (Mille Plateaux)

“Like our bodies and like our desires, the machines we have devised are possessed of a heart which is slowly reduced to embers.” —W.G. Sebald

I sit in the green room of a club that doesn’t exist anymore in Kamppi, the neighborhood of Helsinki that I have since been told is the heart of Finland’s music scene. The year is 2013. Less than forty-eight hours before, I handed in the last of my finals at the art school in Chicago that I would never return to. I boarded a plane flying out of O’Hare to a layover in Schiphol before arriving here in a daze to an overcast Nordic sky in the afternoon and getting picked up by a taciturn taxi driver. I would join a tour of six boys barely out of college toting MacBooks and MIDI gear, hopelessly engaged in absurd attempts at careers in the frighteningly fast internet microcosm of sample-sourced, bass-heavy beat music known to most of its consumers as chillwave. Seated to my left is a current contributor to this newsletter and a dear friend to this day whose name and moniker will remain an open secret, helping themself to rider snacks; across from us is our headliner and the youngest of our crew, a sixteen-year-old from central Florida named Marcel. Marcel’s laptop is broken. He scrambles in a sweat to repair it two hours to his set time. He nudges the local promoter to ask for a screwdriver, who returns several minutes later with a glass of orange juice and vodka. After this misunderstanding leads to scattered laughter, he accepts an offer to load his hard drive onto a laptop borrowed from a white guy in a zebra mask who still bangs on floor toms in blissful oblivion and anonymity.

That summer, I was only three or four years younger than Sasu Ripatti was at the time he assembled Entain in the same city. Much like the slow ascent of its soundscapes, the memories I still have of the three months after that first night in Finland were an endless stretch of cumulus clouds; a sleeplessly thick fog of hedonism, hostel stays and train travel with the occasional burst of vivid clarity. Before coming to writing, I sent a text to our secret friend in pursuit of what could be remembered—they too had trouble stirring up the details. In flashes, I recall inflated industry egos, bad remixes of vintage video game ephemera, arguments with TSA agents, warehouse subwoofers that set off car alarms, boys I made out with in dive bar bathroom stalls. The train ride at dawn overlooking the Scottish Highlands with Laughing Stock in my headphones is still vivid; so is the cacerolazo protest we walked through in Istanbul during the apex of the actions in Gezi Park in lieu of a cancelled show. Try as I might to hold onto the vague montage of memories that remain, chasing after them often renders itself impossible as knowing exactly where upon the waveform Vladislav Delay’s signature fleeting bursts of bass will land. The feeling hasn’t left after marveling in this masterful suite for a handful of years; both microbes of memory and music sparkle and disappear like fireflies evading jars.

Intended or not, Entain will always embody the score of an abstract travelogue to me—to date, it’s one of a handful of albums that I’ve kept downloaded to my phone at the ready for pensive airplane mode listening. With records in this vein that only offer mechanical austerity at first glance, long before its vistas are unveiled through repeat listens, critics will often employ the lexicon of cold—despite the ostensible snowy setting, I only hear blistering heat. From the minor 9th-chord drone that opens “Kohde” onward, you can sense the glitch getting warmer and the temperature of remembrance rise; what follows is an unguided tour through four troubled textural expeditions, the kind where one depersonalizes, hallucinates, learns how to be alone. Perhaps the pervasive influence of dub most prevalent on “Notke” is to blame, but genre distinctions aside, there’s a ceaseless persistence in these pulses and delay sweeps at their boiling points; the sort of heady, hypnotic properties found in addictive postmodern prose without paragraphs—if ever the sudden urge to place the bookmark at any given page mid-sentence appears, you will struggle to pull yourself away.

“I have no clear memory of it,” Ripatti stated when talking through the production process of the discographies of his plural pseudonyms with a publication and arriving here.“There was lots of freewheeling in the studio–a period of power producing, where I wrote lots of music and didn’t do anything else.”Performance and production took a similar precedence for me during this time—though it reached a point of tunnel vision that pushed aside all other aspects of my life outside sound. When leaning into the textures of Entain now, I am only reminded of the slow dance that surrounds a deprived sense of self; the semblance in somnambulism is striking. Through all seventy-five minutes of clicks, cuts and sighs, one can almost hear the hardware becoming fed up with the human and nearly giving up the ghost. When our friendships fail and we reluctantly settle into solitude, we can only linger and wait for the irregular cadence of our machines to blossom out and die.

I spent the last night of the tour by myself at a one-off in Mexico City playing to less than twenty people. Halfway through my set, my laptop froze and wouldn’t turn back on. I left the next day for New York with half the guarantee and an angry email from a booking agent in my inbox. From then on, I knew that loneliness at this volume, despite all its perks and parties, was not where I wanted the music I made to go; it was high time to move forward and let life in. Since then, I have fully surrendered to the sweep and the glitch—whenever I revel in solitude now, I call records like Entain my closest friends. —Nick Zanca

Purchase Entain at Bandcamp.

Yoko Kanno - Napple Tale 妖精図鑑 & Napple Tale 怪獣図鑑 (Marvelous Entertainment)

I spent a majority of my time alone when I was young. My mother spent a lot of time working to support me, since she was taking care of me on her own. The neighbor kid was a couple of years older than me and thought I was annoying, so he rarely ever wanted to play with me. My little sister wouldn’t come into the picture until my early teens, and her presence gave me some severe first-born syndrome; the jealousy caused me to isolate even more. I would spend a lot of time making up more pleasant and less lonely scenarios in my head, and they were usually inspired by video games. I had notebooks full of roleplay I’d written where I inserted myself into my own homebrew of the worlds of The Legend of Zelda or NiGHTS into Dreams, and those were comfortable places to inhabit when I didn’t know how to deal with the frustration of what was around me. I made the unfortunate mistake of leaving one of those notebooks under my desk at the end of a class, and when I went to get it after the next period ended I found that the kid sitting at my desk was reading through my Fire Emblem short story. I was deathly embarrassed, but that somehow didn’t deter me from continuing to write.

Whenever I had some sort of emotional crisis, I would express that in my writing instead of vocalizing it; that was much easier. When I first started to realize that the winter months were contributing to my depression, I took out those frustrations in fiction by making my hero endure the frigid misery of a cold, icy part of Hyrule. I sometimes got fancy and drew monsters in the margins that represented my feelings: cute little fairies as a stand-in for things that made me feel nice, twisted eyeball monsters for when I was feeling edgy, and a funny looking dragon that was supposed to be an analogue for anger. The creature adorning Napple Tale Illustrated Guide to Monsters looked shockingly similar to my attempt at drawing a cool angry dragon, and is the reason I even gave these albums a look.

Illustrated Guide to Monsters and Illustrated Guide to Fairies, a pair of albums released in 2000, are two halves of the soundtrack to the game Napple Tale, released in the same year. I knew of the music long before I knew a thing about the game, as I’m sure is the case for most. Scored by the venerable Yoko Kanno—a composer known for giving an unmistakable sonic identity to Cowboy Bebop, Macross Plus, Wolf’s Rain, and far too many other things to list—the music became a part of my life and a frequent soundtrack to writing when I needed a shot of optimism and starry-eyed wonder. The game looked wonderful, but I had given up hope of ever playing it. It was a Japanese Dreamcast exclusive, and learning the language wasn’t something I considered a possibility at the time. Its obscurity and story of a mostly female team of developers creating an unabashedly feminine video game experience was enticing, but I was resigned to appreciating it from a distance.

Well, until a fan translation dropped from the heavens in October of 2019. The possibility of experiencing this game in a language I can understand turned into an obsession, and I spent a lot of time thinking about it. I watched a ton of Let’s Plays, read as much as I could about it, and scoured the internet for art and promotional material. The story of the protagonist, an ordinary girl named Arsia, reminded me a lot of my video game fanfiction. There was a human element to the narrative that resonated with me. Whisked away to a dream-like world, Arsia’s only way back home is to do helpful things for the citizens of Napple Town and make them happy. The game features a distinct change of seasons that explores the concept of how seasons make the characters of Napple Town feel; their attitudes change as you change the world around them. Despite the European storybook feel and fairytale setting, the characters have complicated insecurities and desires that are hidden beneath the surface. I tried for years to supplement fantasy with emotions that felt real to me, but the game I was trying to create by building on top of established worlds existed all this time, just the slightest bit out of my reach. It’s the video game I always wished I could play, and Napple Town is the place I always dreamed I could live.

I’m not as lonely as I was when I was young. I’ve grown and I’ve learned that it’s okay to get a bit of help working through my feelings and frustrations. I don’t need fantasy to whisk me away from reality, and that’s a relief—not only because it’s a flimsy method to cope with the weight of the world, but because I can simply take a trip to Napple Town and enjoy my time there. A nightmare doesn’t have to be waiting on the other end of a daydream. —Shy Thompson

Listen to Napple Tale 妖精図鑑 at YouTube.

Atoms Family - The Prequel (Centrifugal Phorce)

“I’m from the Atoms fam, and it’s the small things that count / And the atom is a small thing with a large destruction amount.” So begins “Adversity Strikes” by Vast Aire off Atoms Family’s compilation album The Prequel. Atoms Family were a tri-state area supergroup of sorts, started by Vast Aire and Vordul Mega of Cannibal Ox, though it eventually revolved around producer, emcee, and Centrifugal Phorce Records head Cryptic One. At one point, there were over thirty members in Atoms Family before membership pared back to a more manageable roster of eight.

The Prequel is mostly produced by Cryptic—only three of thirteen tracks aren’t—and his arsenal ranges from the string-heavy (“Adversity Strikes”) to the deeply groovy (“Who Am I? [Remix]”), the hard (“Not For Promotional Use”) to the cold (“Cholesterol”). Rap duties are predominantly handled by five emcees: Alaska and Windnbreeze of Def Jux group Hangar 18, Vast Aire and Vordul Mega, and Cryptic One. From Vordul’s drill sergeant flow to Alaska’s verbal backflips to Cryptic’s fluidity, the rapping stays at a high watermark. Interestingly, three of the songs on The Prequel are solo cuts that appear twice, using different backing tracks: Windnbreeze’s disorienting, surreal outing “Nuthin Really Happens,” Alaska’s impressive feat of technique “Who Am I?” and Vast Aire’s boisterous “Adversity Strikes.”

Songs that feature multiple emcees are equally thrilling. “Rhyming for Dummies” is the longest song on the collection at over seven minutes, and it begins with a guns-blazing appearance from Canada rapper Eternia before an elite Cryptic verse: he ends by saying, “Some call it hip hop, but I call it life gear / Survival, vinyl, krylon, a broken dancing and dance mics / and if you have none of the above elements in possession, my suggestion / Stay far away from the Cryptic One’s inventions.” Vast Aire then comes through with the dozens: “Man, please,” he begins, “I evolved from an army that never stood at ease.” There’s another set of verses from each emcee, as the backing track metamorphoses.

Atoms Family only have a few releases to their name, many of which exist solely on the digital plane thanks to Bandcamp, but The Prequel is the only album-length artifact they created as an official release (the CDr titled Atoms Family Archives Vol. 2, which was sold at shows, now sell for hundreds of dollars on Discogs). Cryptic and other members have said they’re not opposed to reuniting the group, and you can occasionally hear Atoms Family members chop it up on the excellent hip hop podcast Call Out Culture, held down by Alaska as well as Philly’s Curly Castro and Zilla Rocca. Cryptic and Geng (another Atoms Family alumnus) have appeared on the podcast, discussing the group’s formation and ethos on the hilarious and profound episode on Vordul Mega, bringing even more of the group’s energy and mission to life. In the meantime, we have this reminder of when they were together, firing on all cylinders, pushing each other to outdo the last verse. —Jordan Reyes

Purchase The Prequel at Bandcamp.

BOaT - Listening Suicidal (WEA)

One of the key bands in Japanese rock at the turn of the millenium, BOaT had two albums of solid, catchy pop-rock under their belt when they signed on with a major label in 1999 and started preparing to make Listening Suicidal that same year. Though considerably strengthened by their strong melodic sense and infectiously charming attitude, there was little in these first two records that would have prepared the average listener for the sheer ambition and range displayed by Listening Suicidal - which stands tall not only as their artistic breakthrough but also as one of the best rock albums of the new millennium.

With major label support they had a bigger studio, more tools to play with, and a superstar producer to help guide them; as a result their ambitions skyrocketed. While their sound had always involved pitting opposites against each other Listening Suicidal was the sound of them trying to sprint in every direction at once. Polystylistic to a fault, each song is crafted with its own unique sound and style. An emotional power ballad leads to a wah-wah soaked pop song so slick it was on a bust-a-move soundtrack, which leads to a Led Zeppelin quoting ten minute long post-rock epic titled GOODBYE MY STRANGE PAIN NO. 28, and so on. It sounds almost like each member of the band was in charge of making a song or two each, or like they didn’t think they would get the chance to make another album again so they crammed as many ideas as possible into this one - it’s an energy that belies the obvious sophistication on display in their playing and writing, in how effortlessly they balance tone and pacing through so many disparate songs.

The gender dynamics of most rock bands simply aren’t worth commenting on, but BOaT (made up of three women and two men) made the constant back and forth between male and female vocalists a major part of their sound and a key part of their appeal. This back and forth is only the most obvious and outermost representation of the spirit of friendship and openness that characterized their output and on Listening Suicidal it sounds like they finally had the resources to expand this open collaboration to their instruments as well as their voices. If the best bands are supposed to be more than just the sum total of their parts then in my mind BOaT is a key example of this in practice. —Samuel McLemore

Listen to Listening Suicidal at YouTube.

Alice Deejay - Who Needs Guitars Anyway? (Violent)

No one can keep a promise. You said 20 years ago you’d never listen to Alice Deejay’s “Better Off Alone.” Friday night, mid-March 2003, windows down, senior year of high school: you’re driving fast to the hundreth remix, still feeling the mash-ups, and promises don’t do shit. You know now that pop music’s become touchless—Who Needs Guitars Anyway?

Alice Deejay were oracles. Their short run from 1998-2002 provides one of the greatest Eurodance SoundCloud tutorials of all time. Let their influence of rhythm and vocals wash over you: find a few beats and release em. Did you write some poetry in middle school? Because a mic plus FruityLoops is all you’ll need.

Bring it back to when your life was the movie Go and you only typed into Napster “(Techno Remix),” going from a 14-hour shift at Blockbuster to the mall to a nap to the dockside warehouse rave. Nowadays you’re searching YouTube for “(Instrumental)” or “(Acapella)” or “Type Beat” to mash-up whatever nonsense you find, blending it all into an hour-long mix you blare off your Citi Bike in an empty Times Square while drunkenly yelling, “TALK TO ME, OO-OO OO-OO OO-Oo, TALK TO ME!!”

Imagine Alice Deejay at the rawest point of their career during the year 2000. They’re on tour in a country that doesn’t exist anymore, at a private performance, and their ritual dance transfixes an audience into a hallucinogenic stupor. It’s 2020, and you can be right there with them—promises were meant to be broken. —C Monster

Listen to Who Needs Guitars Anyway? at YouTube.

Still from The Vertical Ray of the Sun (Tran Anh Hung, 2000)

Thank you for reading the thirtieth issue of Tone Glow. Write about music that doesn’t get love, love music that doesn’t get written about enough.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.