Tone Glow 030: Our Favorite Non-Canonical Albums, 2000 (Part 1)

For a special issue, Tone Glow's writers highlight their 50 favorite non-canonical albums of the year 2000

Banner by Cassiopeia Sturm

Take a second: What are the most beloved albums of the year 2000? Kid A, Since I Left You, Supreme Clientele… what else comes to mind? When we answer such a question, we’re often reticent to mention albums that were beloved by a small group of people, by those living in countries outside the US or UK, by seemingly no one but ourselves.

While there’s a thrill to collectively reminiscing, there’s always going to be more music that deserves recognition. The reality is this: most publications craft lists based on a tabulation of votes set forth by their writers. When those writers are largely white, live in the US, and are rarely given opportunities to write about albums that are more than a year old, the result is years and years of a canon remaining dishonest, narrow in scope, and defined by those with access—those in power. Consider, for example, the artists of color who have created “canonical” albums and how such status has likely been determined by crossover success to a white audience.

20 years later and 2020 is different from 2000 in many ways, one crucial aspect being the access we now have to music. Throughout the past 24 hours, I looked for music released in 2000 and discovered 1) an Iowan skramz band whose website had more than 10,000 page views by the time the group split, 2) an album I’d never heard from an adored Chicago musician I’ve seen live, and 3) a Tom Zé album that deserves as much love as his ’70s output. As I reflect on these experiences, and as I sit next to a stack of Chickfactor zines that feature artists both remembered and forgotten, I’m reminded of how easily music slips through the cracks.

As such, there’s no way we could’ve approached a list of our favorite albums of 2000 if it weren’t with the specific caveat that our choices were non-canonical. And by forgoing any ranking, the albums we all truly care about can be presented with the chance that you, too, might care about them as much as we do. In other words, all 50 of these albums are a part of a canon, it just happens to be a personal one. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

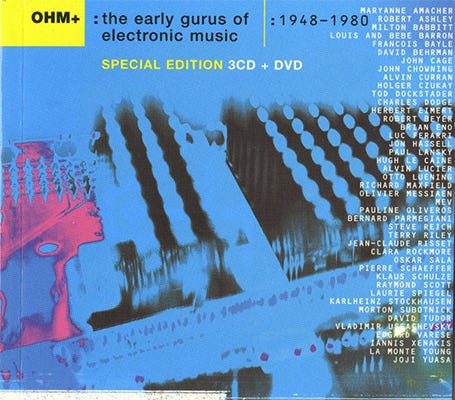

Various Artists - OHM: The Early Gurus Of Electronic Music 1948-1980 (Ellipsis Arts)

Kids these days have it easy. With a keystroke, they have access to all the hottest tunes from Halim El-Dabh to Daphne Oram to Jaap Vink. Here’s what we did back in my day if we wanted to blow our minds with obscure early electronic music: we would ask the less exhausted parental unit to drive us to the local library to flip through jewel cases looking for anything more experimental than Creedence Clearwater Revival. This was the early 2000s. Even if our 56k dial-up could handle LimeWire, fear of retribution from the RIAA was very real.

In this climate, the chances of a young person hearing Pierre Schaeffer or Laurie Spiegel, much less Vladimir Ussachevsky or Francois Bayle, approached zero. Then came the life-saving OHM: The Early Gurus of Electronic Music 1948-1980. There it was, filed under “Various Artists,” with its cover featuring that circuit board pattern and that mysterious equipment and that most appealing word “gurus.” I knew immediately that each of the 42 names listed on that cover signified a world of sound completely alien to me. I had an inkling that once I entered into those worlds these trips to the library, and my relationship with music generally, would change irrevocably. And I was right.

This is really a story about canonization—what music is considered important enough to be made widely available and thus widely known. Canons tend to reproduce themselves, as the widely known becomes more widely available by virtue of name recognition. To break a new name into this cycle is no easy task. The compilers of the set, Jason Gross and Thomas Ziegler, knew this. So they set about carefully curating a list of names that would include the well-established with the less familiar. Gross tells me via email that the pair “listened to a pile of records all day and made notes about them, trying to decide which artists and which tracks to include.” Then they “divided the choices into sections: ‘MUST HAVES - We really can’t do this without...’ and ‘CRUCIAL - We’ll look bad without...’ and ‘IMPORTANT - It would be really good to have…’” These categories spanned the most important geographical regions that fostered the development of electronic music: “WDR in Germany, INA in France, the Sonic Arts Union (which spanned East Coast, West Coast and the Midwest), the New York minimalist group and the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Group.”

This framework allowed Gross and Zeigler to sneak a raft of more obscure artists in, Trojan-horse style, including “Hugh Le Caine, Oskar Sala, Tod Dockstader, Charles Dodge, [and] John Chowning,” and much-needed female representation with “Pauline Oliveros, Maryanne Amacher, Laurie Spiegel, Bebe Barron, [and] Clara Rockmore.” It’s difficult to imagine, but some of these names, now required listening, had little or no work available. Among Gross’s proudest moments was getting La Monte Young’s permission for “Drift Study 31 | 69 12:17:30 – 12:49:58 PM NYC” because “he had so little official music in print at the time because he’s extremely particular about how his work is released.” The comp also gave crucial exposure to Bebe Barron “since she wasn’t given the credit she deserved for the Forbidden Planet soundtrack,” the first all-electronic film score. And the duo was able to expand beyond the standard Euro-American history with Joji Yuasa, “as he was one of the composers who wasn't part of any particular school/group but was still vital and there is [a] fuller story about Japanese electronic music that was waiting to be told.”

The influence of a compilation like this is difficult to quantify, but Gross noticed increased attention to composers like Ferrari, Dockstader, Le Caine, and Xenakis in the period since 2000, along with sections for modern composers popping up in indie record stores. Surely the work of contemporary reissue labels like Paradigm and Light in the Attic is built on the foundation laid by OHM twenty years ago. Perhaps its most important influence, though, is not on the reputations of specific composers but on successive generations of listeners—countless people who would not otherwise have had an opportunity to hear this music and whose lives would likely be drastically different as a result. Whenever I go back to my hometown, I stop in at the local library. The same copy of OHM is still there, but sometimes it’s checked out. I bet it’s blown many more minds since my day. —Matthew Blackwell

Note: I’d like to thank Jason Gross for kindly answering my questions for this piece. His online music magazine, Perfect Sound Forever, is currently in its 25th year. You can read more about the OHM compilation here.

Listen to OHM: Early Gurus of Electronic Music 1948-1980 here and here and here at YouTube.

Various Artists - BGM: 1980-2000 (無印良品)

“MUJI is enough.” That tagline, emblazoned across a video showcasing a bevy of understated MUJI products, really captured my attention on a bored Friday evening; I must have had nothing better to do. Short for Mujirushi Ryōhin—meaning “no brand, quality goods”—MUJI is a bit of a high-concept general store that prides itself on its minimalist philosophy. Focusing on the details of everyday life and meeting the needs of the average consumer, MUJI deals in a wide variety of common products that don’t have the bells and whistles you might expect to find in a Walmart or a Target. From simple furniture to clothes to cleaning supplies to stationery to storage containers, everything is unbranded and designed for simplicity. The goal is simple: everything you need, and nothing you don’t. At the risk of sounding too much like a sales pitch, I have to stress that I’d find this ideology laudable if not for one fundamental problem: MUJI stuff is way too expensive. Scouring their website during a free shipping event, I looked so hard for something that felt like a good deal and couldn’t find anything. Not wanting to come out empty-handed, I bought a soap dispenser, a 2019 calendar planner, and some sticky notes shaped like cats. They ought to change their tagline; “MUJI is too damn much.”

MUJI has been kicking since the ’80s, and they have commissioned original music to play in their stores since the beginning. Listening through this compilation, you get the sense that this is a business with a little bit of pride. The music herein is pleasant, certainly, and perfectly shoppable—but it distinguishes itself by being a bit bold, artistic, and sometimes just downright strange. If you’re a fan of ambient music, you might have even heard some of this already. A YouTube upload that somehow got sucked into the algorithm has been going around since 2017 which features one of Haruomi Hosono’s contributions to the album. It claims to be Hosono’s Hana Ni Mizu cassette, and that’s mostly true: it does include two tracks Hosono created for MUJI that were never used—including a version of “Talking” that slightly differs from the one heard here on BGM—and, inexplicably, the track “Original BGM” that appears on BGM but not on the tape at all. The video contains an image made by the late graphic designer Ikko Tanaka, which has nothing to do with Hosono or MUJI. The video description notes these discrepancies now, after hundreds of commenters pointed them out over the years.

Despite the dearth of information around this music and the context that has changed with time as the uploader and commenters add and remove what they believe to be facts, over a million people found such a beauty in this music made as a backdrop to plop your butt onto uncomfortable mattresses and put your hands all over terry cloth towels; they listened without even caring what it is or what it was made for. This compilation is filled to the brim with notable composers and session musicians, most of them recording under one-off names they never used again. For my money (which isn’t a lot, even though I save a lot of it not shopping at MUJI), they succeed in their mission statement with this release far more than they do with their products. Unconcerned with using big names to pull you in, BGM 1980-2000 gives you everything you need, and none of what you don’t. No branding—just good music. —Shy Thompson

Listen to BGM: 1980-2000 at YouTube.

Panchiko - D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L (self-released)

It’s hard to get more “non-canonically” obscured from fair appraisal than an EP limited to a pressing of 30 copies, condemned to used-rubbish bins and the tender mercies of A&R representatives, made by a band whose moniker is a misspelling of the name for a type of Japanese slot machine, with cover art lifted from an obscure shojo manga about the romantic misadventures of a boy who crossdresses as a girl, titled after a genre most music listeners in the year 2000 had probably never even heard of. It’s a shame; Panchiko’s D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L is four tracks of as adventurous and sincere an example of bouncily Kinks-influenced British indie as there could be, a clear sibling to the same heedless multigeneric abandon that animated the Boo Radleys’s Ichabod and I a decade prior.

The shoegazey effects, trip-hop record scratches, and spacey samples that swirl and sway behind catchy hooks and reverb-heavy falsetto croons on the title track’s romantic ode to a genre it couldn’t sound less like butt up with shameless bravado against the crunchy, rollicking Parklife-inspired basslines and squelching synths anchoring “Stabilisers for Big Boys.” Even superficially-named “Laputa” jangles and yearns with the best of them; only EP closer “The Eyes of Ibad” outstays its welcome, committing to an awkward mash of a laddish aping of Oasis and the lysergic meander of post-Spiritualized ambient pop. It deserves to do more than molder in the back of some record store in Nottingham, or some record executive’s file cabinet, written off as an example of a style years past its expiration date, but for 16 years it did just that. Panchiko never went anywhere as a band after D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L’s release and left no digital footprint behind; effectively, to the world outside of their friends and family in Nottingham, they had never existed at all.

The journey Panchiko took from nonexistent entity in the discourse to cult sensation is a testament to the inspiring resurrective powers and terrifyingly invasive surveillance powers of the internet and a story about the ways time literally changes our experience of the music we love, a context that only intensifies its relevance to any list of “non-canonical” albums of 2000. An anonymous user on the cesspool of the internet known as 4chan posted a picture of the album as they purchased it in 2016, and uploaded a ripped .rar of its contents to Mega.nz shortly after, the songs contained within heavily decayed into even fuzzier noise by disc rot. The songs, already drenched in reverb and effects as they were, now sounded like transmissions from outer space, mysterious and weird; and like all things weird they created a compulsion in all who heard them to want to know more about them.

This obsessive fixation led to one explorer in the musical hinterlands calling every single person with the same first name as the band’s lead singer in Nottingham they found listed in the phone directory, and surprisingly instead of running for the hills and changing his identity this gesture actually charmed the lead singer once he’d been located, which put them in touch with the “engineer” for the record, who’d—conveniently for this story—gone on to a career in mixing and remastering. Now, 20 years later, the album can be heard in its original format. Just imagine how many other albums like it have never gotten that lucky. —Tara Wrist

Purchase D>E>A>T>H>M>E>T>A>L at Bandcamp.

The Pillows & Shinkichi Mitsumune - FLCL Original Soundtrack 1: Addict (Starchild)

The Pillows were the first rock band I was obsessed with, and it was exclusively due to FLCL. FLCL was an anime that first appeared in the United States during the Summer of 2003, and 13-year-old me, watching without my parents’ approval, felt like its characters, themes, and story channeled my fear of an absurd universe that sought to remove agency from anyone under eighteen. The Pillows brought together melancholy, high-octane energy, and hooks that spoke to my adolescent heart. Now, as a 30-year-old who’s listened to a not insubstantial amount of records, it’s obvious that the Pillows were working off many ’90s britpop and alt-rock icons—standout track “One Life” sounds a whole lot like Oasis, as do other songs. And yet, the hooks still skewer me.

Singer Sawao Yamanaka’s vocals are simple and pure, matching the songwriting and performance of his band, and his custom-made English phrasings detail emotion without letting pesky syntax get in the way. On my favorite song from the soundtrack, the anthemic “Little Busters,” Yamanaka-san muses “With the kids sing out the future / Maybe, kids don’t need the masters / Just waiting for the little Busters.” In FLCL, the song plays in moments of victory—when main character Naota-kun feels his frustration and hopelessness ebb.

Addict is predominantly Pillows songs, but it does include some of Shinkichi Mitsumune’s lively score for the anime, much of which stands in stark contrast, whether it’s the pristine, string-plucked ballad “Rever’s Edge,” the piano-based jazz fusion on “Pain,” or the swinging jazzhop of “Selfish-b.” These are fun inclusions, and vary the pacing of the collection, but they’re not as immediate and driving as the Pillows’s work.

Unfortunately, Addict only features the Pillows’ songs as they appear in FLCL, which means some are just instrumental versions, as is the case with “Come Down” and “Carnival.” In some circumstances, it cuts off some time—the nearly-four minute “Last Dinosaur” is only 26 seconds long on this soundtrack—but I was a middle schooler with limited internet experience and buying imported anime soundtrack CDs from Mitsuwa Marketplace was all I could get. Still, some Pillows on CD whenever I wanted was better than only hearing the Pillows Monday through Friday at 11PM CST in August 2003. —Jordan Reyes

Listen to “Little Busters” at YouTube.

The Bran Flakes - I Don't Have a Friend (Lomo)

Remembering 2000 as a younger millennial from the U.S. is to remember the commercials of the time, a breeding ground for hungry ad agencies looking to target the audiences of the relatively new kids’ stations like Cartoon Network and Nickelodeon. These story-lined commercials with obnoxious close-ups, fish eye lens and technicolor palettes took over two 3-minute ad breaks every half-hour to sell gak or the yo-yo ball.

The aesthetic line connecting many of these commercials is best understood through the hundreds of hours-long montages of early 2000s on YouTube with millions of views. Some of my earliest memories are of being advertised to while watching early morning cartoons, and some of the corporate jingles still bounce around my head like the lyrics to Top 40 hits.

Enter: The Bran Flakes, a goofy musical duo that specializes in heavy-use sampling, like The Books, with more humor and less pretentiousness, and The Avalanches with less R&B influence. In 2000, the group released I Don’t Have a Friend, an album featuring a cover of a blue, cartoon character with starry eyes. Pair it with the group’s name—a poke at the huge cereal brand—and cut-up, memetic sound sources and you’ve got a breeding ground for commercial nostalgia-bait.

Twenty years after its release, I Don’t Have a Friend is a time capsule of those commercials. The samples of classic tracks and TV-theme songs blaze by and any beats underneath are so bombastic that they can conjure up a smile. Just as each advertisement for novelty stickers, cartoon merch, or wonka bars flash by, trying to grab the max amount of attention in a short 30-second time frame, the songs on I Don’t have a Friend strive for the same effect. Months after I heard the record for the first time (and hadn’t listened since), I still remembered the words to the old-Hollywood chorus of “Mutual Admiration and Love,” the Keith Hamshere sample that plays over the “Funky Drummer” loop, and the twinkling glockenspiel pattern on “Everybody Pay Attention Now.” I Don’t Have a Friend is sickeningly sweet and easily digestible.

The innocent joy of each track is also underscored by a sense of unease. In some cases the feeling is upfront, like on “Smith Corona 10-Day Typing Course,” with its PSA spoken word section urging the kids to type “Fuck You” on their keyboard. Other times, the darker side of a jingle is right in the title, as with “I Am a Groupie,” the title track and, perhaps the most stomach-churning, “Turn the Channel, It’s Another Commercial.”

So, to remember the year 2000 as a young millennial from the U.S. is to remember an adolescence of being advertised too much via sickeningly neon clips. It’s remembering that so much of my early memory space is taken up by commercials that were more catchy than the shows. There’s even a strange pride to it for some. “Only ’90s Kids” videos on the internet are loaded with this very specific style of advertisement. It had an impact on many of us, and maybe it even subconsciously strengthened much of the generation’s distrust of capitalism decades later. The Bran Flakes jumped in at the right time with the right message, but this duo that encapsulated a medium designed to be remembered was forgotten. —Sam Tornow

Listen to I Don’t Have a Friend at YouTube.

Tabla Beat Science - Tala Matrix (Palm Pictures / Axiom)

The music press’s inability to grapple with what is variously called “fusion,” “world beat,” “global beat,” even “global beat fusion” (the confusion of terms itself says enough) will go down as one of its greatest critical failures. It doesn’t matter if the review is on Mor lam rap or Birmingham reggae or Anatolian folk-techno, the reader can always expect to be treated to platitudes about the multicultural society, essential voices and spaces, the future of music, and so on. That last one in particular deserves some scrutiny, as the recent past is littered with future-of-music anointees whose time, somehow, never arrived.

Remember the Asian Underground? Another future that never came to pass—a collective-cum-genre of British South Asians pairing folk music with drum and bass and other of-the-minute dancefloor trends. They got a lot of ink in the press; they had a great human interest angle: multiculturalism, a new Britain, no borders, the end of history, and all that. Björk associate Talvin Singh even cinched a Mercury Prize win in 1999, but his name, along with all of his warmly reviewed contemporaries, was quickly swept into the margins of history once liberals got tired of golf-clapping. Their names now scarcely come up in discussions of either the time period or as an influence in contemporary music; guess they weren’t such an essential voice after all.

Tabla Beat Science—a supergroup of fusion artists loosely managed by jack-of-all-trades producer Bill Laswell—falls under the Asian Underground umbrella, thanks to the participation of two of its brightest stars, Karsh Kale and the aforementioned Singh. And the album is an important dialogue between the two, their immediate predecessors and influences (percussionists Zakir Hussain and Trilok Gurtu), and most importantly, Bill Laswell. You see, Tala Matrix, their debut album, might look like a borderline offensive dorm tapestry and sound like an exercise in patchouli kitsch… were you expecting a but? Yeah, the album leans right into stereotypes, and distinctly white American ones besides (I wasn’t kidding when I said Laswell was important). But that’s okay, even desirable, because Tala Matrix is a commentary on its own genre, and more importantly, a reflection on a hundred years of fusion history, if not hundreds of years of colonial history. As its target audience would probably say, it goes deep, man.

Here’s what we get wrong about fusion: it’s not about the future. Or the Now, or progress, or whatever euphemism is papering over the same cliché. Fusion is all about the past: what led to a tabla sounding this good over a club beat? No, music is not the universal language, certain semiotic associations have to be forged before something like “Secret Channel” or “Don’t Worry.com” can be understood as a commentary of the frenetic breakbeats of jungle by way of the tabla’s famous laggi flourishes. The album is full of musical similes like this—sarangis and synth pads, just to pick another low-hanging one—but let’s not pretend we are witnessing a fusion. The real fusion happened almost fifty years earlier, the first time a synth (well, a clavioline) touched a tabla in “Man Dole Mera Tan Dole.” The tabla tainted, hybridized, grew up together with the synthesizer in India… and the West was no slouch either in the hybridity department, ‘cause guess where the whole idea for a synth drone came from! Tala Matrix is careful and intelligent with its connection-drawing; it is telling a story about how centuries of reciprocated orientalism and occidentalism produced something quite similar… and this is what the Asian Underground was all about! So can we start clapping for them again, please? —Adesh Thapliyal

Purchase Tala Matrix at Bandcamp.

Lemon Jelly - Lemonjelly.ky (XL)

When my dad first gave me an iPod in middle school and officially kicked off my musical development, he included four bands on there which, in many ways, shaped my tastes for the rest of my life: Pink Floyd, The Flaming Lips, They Might Be Giants, and Lemon Jelly. The first three are widely beloved bands with indisputable followings; Lemon Jelly, on the other hand, has largely been forgotten by the annals of music history. A peculiar byproduct of early-’00s electronica forged in the fires of The Three E.P.’s and Moon Safari, the duo of Fred Deakin and Nick Franglen released three E.P.’s of their own in the late ’90s, eventually compiling them into a debut release on XL—the technicolor wallpaper music of Lemonjelly.ky.

Lemon Jelly’s radiant, shimmering electronica summons memories of early rainbow iPod Nano ads, their music polished with an almost alarming degree of commercial cleanliness. The tracks on Lemonjelly.ky have a certain aura of Trippiness™ to them, their colorful loops unspooling into a fractal pattern of silly, sampled British voices and feel-good refrains. The opening song revolves entirely around a woman curiously asking “What do you do in the bath?” while hypnotically-phasing vocal samples rise and fall, sucking one into a trance as kaleidoscopic as it is kooky. Again, this was some of the first electronic music I had ever heard, and in some ways its optimistic take on trip-hop would set me up for all my later explorations in looped dance music and psychedelia. Listening to it 20 years later, it’s impossible for me to separate the music from the nostalgia, but it’s also hard for me not to hear Lemon Jelly’s easygoing grooves in the relaxed sounds of 24/7 lo-fi beats to study/relax to (especially on jazzy tracks like “A Tune for Jack”).

Lemonjelly.ky remains unique in the way it captures a certain eclectic innocence that very well may have completely vanished from the world after 9/11. I still don’t think I’ve ever heard a song quite like “His Majesty King Raam,” which compresses the wintry melancholy of classic Danny Elfman scores into one whimsical loop, or the mind-bwahhing space jazz of “Page One,” whose subject matter is something that has still terrified me well into adulthood. Even “Homage to Patagonia,” which summons memories of so many forgotten Thievery Corporation knockoffs, tastefully unfurls its elongated funk over a slow-burning 10 minutes, eventually snapping into place for a delightful, cymbal-crashing finale. Listening back to the album now, there’s a simplicity to it that I can’t help but feel is missing from so many modern strains of electronic music, a willingness to simply find a happy place and hang out there for as long as it takes. The fact that this musical attitude feels so foreign now is reason enough to dip a toe back into Lemon Jelly’s bath. —Sam Goldner

Listen to “His Majesty King Raam” at YouTube.

Desi (Деси) - Angelic Woman (Ангелска Жена) (Ара Аудио-Видео)

As an American with just one Bulgarian parent, I would describe my understanding of Bulgaria as tenuous at best. The little fragments of Bulgarian culture that I experienced growing up were mostly watered-down by my mom, who thought that assimilating to American “culture” would benefit me most. My mother’s family still lives in her hometown of Burgas, and over the past few years, I’ve been there twice. My trips have been motivated mostly by a somewhat flimsy idea that I would absorb my family’s history and culture by being in their country.

The first time I went, my cousin Irina told me that since I wore Adidas sneakers, I was definitely Bulgarian. I wasn’t very convinced. My baba (grandma) always gets me the English menu when we go to restaurants. When I got christened in a little, ancient Orthodox church in the countryside, my reading comprehension was too poor to properly recite my prayers. The priest, a family friend that I’d never met before, slathered my head in oil anyway. Somehow, I was saved.

I know about chalga—Bulgarian folk-pop with Middle Eastern influences—the same way I know everything else Bulgarian: in a secondhand way. My Bulgarian godmother played Roma musician Azis at a family dinner once, to my mom’s mild delight and baba’s dismay. I think my baba fucking hates chalga and thinks it’s trashy. A lot of Bulgarians hate chalga because a lot of Bulgarians are racist, but some people just don’t like it. I like it when it sounds good, but I don’t like when people act like it’s the only type of music that exists in Bulgaria.

Anyway, Angelska Zhena (Angelic Woman) by fallen Bulgarian pop star Desi (it is possible that she is an alternate universe or pre-levelled up form of cultural icon Desi Slava) is a very solid introduction to chalga and the template that Bulgarian record executives follow in hopes of making women into stars. Desi looks cool as hell on the album packaging with her thigh high boots, slick, post-90s curls, and leather jacket. She sings about fashion, being beautiful, and being sad. There are some tasty little dance beats on “Angelska Zhena,” “Zvezdna Pesen,” and “Moda,” and Desi has a pretty, slightly raw-sounding voice that she colors with folk vocal runs. There’s also quite a few instances of gaida playing, which is the best instrument ever.

It’s really weird to be disconnected from your family’s culture. Is it my culture too? Не знам, но обичам кюфтенцата която Billa продава. Харесвате ли тези? —Ashley Bardhan

Listen to Angelic Woman at YouTube.

Juana Molina - Segundo (Bla Bla Discos)

Music begets closeness begets comfort: we move toward speakers and stick earbuds like cotton wool in our ears. I reach to the voice that tells me simple tales: about a dog, about an old woman, about someone’s (anyone’s) mother. Juana Molina’s sophomore effort is not her most flashy, nor her most sophisticated, but it may very well be her most enveloping; soft blankets woven from faintly bleeping sine waves, an acoustic guitar that caresses the microphone with each patient strum, a warm, silken voice that rarely raises beyond a pleasant murmur. Molina treads through textures and moods as though moving through tall grass, her hands lingering at the tip of each blade.

Segundo bleeds sincerity, despondency, solitude, despair; its subjects and narrators live unexamined lives, think unexamined thoughts. Some of Molina’s characters express horror at how they fade into the margins, and others accept it; indeed, most of us must come to terms with this at some level: how all we are, all we have been, and all we will be is so easily washed away. Waves lap at the shoreline, carrying away hundreds upon thousands of individual grains of sand; do any of us think of where things go when we cannot see them?

There are hundreds of rooms in this house, but any one of them can be your home. Take the box, wrapped in tissue paper, and carry it to the water’s edge; watch how its shell melts and pulls away in the loose current of the stream. —Maxie Younger

Listen to “El Perro” at YouTube.

Annette Peacock - An Acrobat’s Heart (ECM)

“Where does music go when it’s not playing? –she asked herself. And disarmed she would answer: May they make a harp out of my nerves when I die.” – Clarice Lispector

In the brief behind-the-scenes documentary that accompanied the release of the stunning song cycle An Acrobat’s Heart, we watch a French-braided, leather-clad Annette Peacock giddily twirl and step-ball-change between takes around the wooden live room of Rainbow Studios in Oslo. This space is one of few where Manfred Eicher had produced hundreds of subtle, stormy subversions of time-space since founding the ECM label in 1969. Although the apparent camaraderie captured between artist and producer has the energy of a decades-long creative partnership, this set for string quartet, piano and voice that Eicher commissioned was somehow their first (to date, only) direct rodeo together. When interviewed, she succinctly self-identifies as a “source for other people” and any listener well-acquainted with her chameleonic corpus will know this claim to be a criminal understatement. One could argue that the style of loose, open balladry she developed in her compositions for Paul Bley formed the prototype of what we know as the signature “ECM sound”; David Bowie had a troubled history of persistently (unsuccessfully) begging her to collaborate before blatantly plagiarizing her harmonies years later; even Busta Rhymes once spat aggressive bars over a sample of her ascending Rhodes.

Peacock’s smoky and vulnerable vocal is in peak form throughout this hour bedded by Norway’s Cikada String Quartet, an ensemble whose core repertoire consists of major works by Xenakis and Nono; once the synthetic artifice that made her run of ironic records sparkle and gleam is stripped, what remains is a refreshingly organic space of sheets bereft of false curtains. Her lyrical phrasing and sparse string-spelling share the same breath, drawing out an effortless drift between elegant lieder and fake book-ready torch song. The same strain of lovelorn, diaristic gravity first found in the piano-and-voice vignettes on the quiet half of Patty Waters’ Sings is omnipresent here; this time around, the voice belongs an older and wiser woman, prone to languorous reflection over rapturous residence: “take the sum of your own tears / multiple by unknown years / you’ve been so brave, unafraid / underneath you bear the wounded child.” Between these silences lies a Feldmanesque unpredictability: there’s no telling where these harmonies will lead on first listen, but this mode of discretion is hardly uninviting—it’s intimacy personified. Of all the highlights of a discography this disparate and fruitful, An Acrobat’s Heart has always been the one I happen to return to; if her sonic project all along was to soundtrack “a world that’s destroying itself,” I couldn’t think of a calmer culmination. —Nick Zanca

Peter Garland - The Days Run Away (Tzadik)

Minimalism is a categorization that feels inherently burdened by its contradictions. Early minimalist artists despised being called minimalists because their art wasn’t small, it uncovered beauty in compact ideas. Minimalist composers equally hated the term. And yet the minimalist musical genre has reigned supreme, becoming somewhat of a catchall phrase for tonality that encompasses the characteristic strict repetitions of the 1960s as well as much of today’s more sweeping, lyrical work. And then there’s the trendy minimalist interior design movement, marked by stark green plants against white walls, spotless countertops, and precisely placed monochrome furniture. It touts the “less is more” ideology, yet somehow still encourages the late capitalist ethos of consumerism.

Peter Garland’s The Days Run Away is an album that embodies what you might imagine minimalism to be in its most basic sense. Every moment is carefully crafted to uncover the deepest sensitivities within the simplest melodies; it's content to hang in the present, eschewing forward motion for quiet contemplation. “Bright Angel,” the first track on the record, slowly unfolds from simple, high-pitched repetition into darker, more urgent harmonies. Stillness caresses every pang of the piano; melody feels like a spontaneous thought more so than a prescribed action. Garland cites composers like Harry Partch and John Cage as influences, and here, the throughlines are evident.

Pianist Aki Takahashi illuminates the gentle radiance of Garland’s compositions. Her playing is crisp and understated, highlighting the natural resonance of the compositions themselves. Poignancy blooms from soft but powerful repetition and rich but uncomplicated harmonic progression. One of the most compelling tracks on the album, “A Song,” brings these elements to the center stage. The piece begins with the emphatic repetition of one chord, and steadily unfurls. But even as the melodies begin to include more motion, tranquility remains at the core, and intimacy grows from its ardent, straightforward presentation. Pauses adorn the space between melodic shifts, showing that the moments of silence mean just as much as periods of intervallic repetition.

The joy of this music comes from its subtle blend of delicacy with what feels impromptu. It transports you to a tender spring afternoon, where the flowers are beginning to bloom and the sun’s warmth has just returned. It’s mesmerizing in its purposeful lack of intricacy and its incredibly personal sentiment. Garland’s music isn’t as high-profile as some of his minimalist peers, but his music on The Days Run Away reveals to us the sparkling possibility of the austere. —Vanessa Ague

Listen to “A Song” at YouTube.

Elevator - A Taste of Complete Perspective (Teenage USA)

As the ’90s grunge boom came to a close, Eastern Canadian underground rock hero Rick White and his bandmates in Elevator (previously playing together as Eric’s Trip) split up with their longtime label, Sub Pop. According to the detailed recollections on White’s Bandcamp page for the outtakes collection accompanying A Taste of Complete Perspective, the trio had “come upon a nice connection for super clean liquid LSD, and this started a new level of exploration that would vividly colour 1999.”

Set up with a studio in the basement of their New Brunswick home and “enough money from a recent publishing deal to pay the rent for another year or so,” they began recording this high water mark of hallucinogenic lo-fi dream-punk. Field recordings of chirping birds, clanging church bells, and sloshing sound effects weave throughout the album like a spiritual sequel to Bill Holt’s Dreamies. The songs themselves are further psyched out with backmasked guitars, eerie layered vocals, and crossfades that seem to occur with an unconscious logic. It can be heard as a predecessor to the musique concrète elements of Gastr del Sol’s Camoufleur, albeit with a ragged, homespun quality like folk art sold at a church bazaar.

The lyrics of opener “Driftwood” prepare you for the the kind of trip you’re about to embark upon: “We are only little babies crawling around in the sand / Questions melt away, we are only of the land / I am lying in woods seeping in the morning earth / I am energy and death opening my second birth.” Rick White’s riffs have a stoner-rock swirl that occasionally tastes metallic, while Tara White’s bass roars, and Mark Gaudet’s massive tom fills tumble down the mountain. The album’s heavy passages are balanced out with sparse, quiet songs played on synths, drum machines, and acoustic guitars. Vocally alternating between a detached coolness and agonized cries, it becomes clear why White’s first band was named after a song from Daydream Nation. The combination of blown-out distortion and fragile emotion also points to the future influence this music would have on Phil Elverum.

A Taste of Complete Perspective may not be the most melodically straightforward entry point into the world of Rick White (try Love Tara by Eric’s Trip or the first album by Elevator to Hell). Yet as a glimpse into his musical sketchbook, few albums feel this freed from commercial constraints. —Jesse Locke

Listen to “A Taste of the Great Beyond” at YouTube.

Coil - Queens of the Circulating Library (Eskaton)

As the Western world realized it had survived Y2K and would have to reckon with what 21st Century life might be like, queer sonic magicians Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson and John Balance were up to their elbows in releases. For Coil, 1998-2005 was a period of fertility comparable to Bowie in the ’70s, Prince in the ’80s, and Kate Bush in the time between them: the lysergic ooze of Time Machines; the four solstice and equinox EPs, unearthly in their awestruck beauty; the instant classics Musick to Play in the Dark Vol. 1 and its dubby second sister, which connected dots between Robert Ashley and Autechre; four live albums of magisterial breadth, twinkling and terrifying, well worth the fifteen years Coil spent in preparation; and the autumnal farewell of The Ape of Naples, ablaze with marimba and camp, which came into the world a year after Balance’s death and five before Christopherson followed him out.

Dead center in all this throbs 2000’s Queens of the Circulating Library, a single 49-minute track first released as a sperm-emblazoned CD-R sold at Coil’s Time Machines Royal Festival Hall Cornucopia festival. (A second edition was mail-orderable in a pink clam shell; the version Coil performed at the festival, abbreviated and trembling with prophesy, later appeared on Live One.) The only Coil track not to feature Christopherson, “Queens” features longtime Coil companion Thighpaulsandra in synthesis with Balance. The pair emit a drone forthright in its loveliness; it gently orbits, sometimes glinting and flaring, or gurgling or erupting into unalarming sirens. Above this, Thighpaulsaundra’s mother, the opera singer Dorothy Lewis, talks in Balance’s words of trees and their progeny:

You cut down the trees to make paper disease…

Return the book of knowledge

Return the Marble Index

File under ‘paradox’

The forest is a college, each tree a university.

Balance wrote the words as a tribute to, as the liner notes has it, “mothers everywhere,” nodding not just to Lewis but Nico and Kate Bush (earlier, Lewis warns “It’s in the trees / it’s coming!”) It’s of a piece with Coil’s millennial rejection of their earlier Solar / Masculine energy in favor of a more Lunar / Feminine mood—the moment they became mothers to a generation or two of queers in deep need of elders. Amniotic, not ambient. A fertile repose in natural wonder. “Words, words, words,” Lewis finishes. “You may as well listen to the birds.” —Jesse Dorris

Listen to Queens of the Circulating Library at YouTube.

Francisco López - Untitled #104 (Alien8)

Metal is founded on rhythm—free rhythm in a sense, but still bounded, more influenced by prog with its sudden tempo shifts and dodges than free jazz. Lopez commits the ultimate sin on Untitled #104, layering and stacking multiple metal rhythms to the point where the cut disappears, replaced by a veiled blast beat behemoth that unfurls and expands ad infinitum. Clarity, exactitude, precision, and technique give way to disorientation, instinct, a pummeling.

Oddly enough, in a sense Lopez’s inversion is actually the abstract promise of metal in general—raw, unbounded power—unleashed and made manifest. But the end result is a void: Untitled #104 lacks the propulsive, headbanging energy of the best metal, and in its attempt to overpower only creates a thick muck of what often amounts to white noise punctuated by thin kicks and crashes. There is no momentum, there is no movement; this is not Ascension. I’m making it sound pretty bad. Pitchfork gave this a 0.0 back in the day, and I don’t blame anyone for agreeing. This is undeniably pretentious bullshit, and also falls into the tempting trap of ‘elevating’ a form that’s perceived to be ‘low’ (metal, with its garish artwork, lyrics, vocals...) into something a Wire critic can unashamedly rave about (a review from Aquarius Records called it “the academic / art world colonization of metal”).

So why is it worth writing about twenty years later? Mostly because, even if Lopez’s project fails to move me most of the time (I’ve barely made it through two full listens), I can’t deny its unique, artefact-al pull—the proto-Yeezus no artwork-CD-ROM artwork definitely helps—and its, yes, thought-provoking quality. With Untitled #104, Lopez successfully ‘denatures’ an utterly singular and distinctive sound (over)loaded with connotations—the metal riff—reducing it to a homogeneous slab of sonic putty. From this perspective, the possibilities are truly endless. —Sunik Kim

Listen to Untitled #104 at YouTube.

Asterisk* - Dogma I: Death of a Dromologist (31G)

This is an album that’s been a favorite of mine for nearly half of a decade now, but this is somehow my first time writing about it. I suppose I’ve always subconsciously avoided it because I’ve been able to hone my visceral reactions to more abstract music into intelligible verbal descriptions, but the same is not always true for hardcore and grind, especially the releases I love the most. And Dogma I: Death of a Dromologist is the one I love the most. More than The Inalienable Dreamless, more than From Soil Laced with Lyme, more than even Farewell All Joy.

“Dromologist” isn’t a word you hear very often. The concept of “dromology” was coined by French theorist Paul Virilio, drawn from the “Ancient Greek noun for race or racetrack” (dromos), and is used in his studies of the role of speed in human existence and development in an abstract, philosophical way, apparently closely associated with postmodernism. It’s all well over my head, and it’s not really possible to approach it from the angle of the band’s lyrics either unless you own the actual LP, since they’re almost entirely unintelligible on their own (more on that later). So the only thing we really know for sure is that the first installment of Asterisk*’s Dogma series, posthumously collected on a 2002 CD on Three One G, is a sort of study of speed in the concrete, musical sense—the guitars are dirtied yet every note is delivered with a robotic clarity, various instrumental parts are pasted in and ripped away with a mercilessly experimental sensibility, blast beat frenzies tear by so fast they blur into abrasive, hypnotic drones. It’s a terrifyingly scientific approach to grindcore, and only makes the onslaught of expertly sequenced bite-sized tracks more violent.

“Dromology” begins with a rather fucked-up sounding drum machine grinding out a hypnotic beat, and there’s immediately a sense that something much more vicious is about to happen—and it does, the flesh-stripping metallic whirlwind of blown-out inhuman shrieks, dizzying yet firmly rhythmic drum cacophony, and dissonant, agile, almost twangy guitar riffs ripping into the void. After that, things don’t really let up apart from the brief, instrumental “*” and later with the unexpectedly sublime piano outro that concludes “The Spatio-Temporal Aspect,” but luckily you don’t really want them to. It’s an exhausting, animalistic sprint to the finish, breaking for unbearable tension before memorable, body-wracking breakdown sections in “Red” and “Bible”; fragmenting into jarring blasts of squalling noise on “Stasis Is Death”; injecting a burst of brutal brevity with the four-second “Hello Vargas.” Reading along with the lyrics sheet only adds another dimension of horrifying ferocity, sometimes directed outward in an abstract sense but mainly taking the form of vitriolic self-hatred, anger, misery: “I just amplified myself to the floor. Squeezed out dripping like jelly. That pink fucking jelly. I am no longer the one to be. To trust. To listen to as you hammer yourself to the wall with nails of fucking lies. End here, end now. You ended me. I end here” (“Eat Me”).

In just over sixteen minutes, an enigmatic Swedish trio condenses absolutely everything I love about this music into a single, singular powerhouse of an LP. It’s one of those albums I can’t even listen to in the background while doing something else; it’s way too all-consuming to resist the urge to air-drum or headbang. This record truly changed my life. Granted, I’m not sure whether it was for the better or the worse yet, but at least I get to jam this shit. —Jack Davidson

Listen to “Dromology” at YouTube.

CiM - Reference (deFocus)

Reference is the only album released by Simon Walley operating as CiM under the small, Warp-like label first known as Focus, then deFocus before it became defunct. Reference is generous, a collection of 22 beats whose techno beats and turquoise-sky synth melodies position it as the follow-up to Boards of Canada’s Music Has the Right of Children that their follow-up Geogaddi was decidedly not. Case-in-point: “Numerique”’s bass recalls “Kaini Industries.”

Despite the number of tracks, Reference is relatively short, barely clocking over an hour because all but seven of them are under three minutes. Crucially, the short ones feel just as full as the long ones. The beatless “Warm Data” is only two-and-a-half minutes but over the duration of the song, Walley patiently introduces more layers: a higher-pitched keyboard that adds a new melody, snapping the song’s ambient drift into focus; then later, sustained keyboards that brings the song back into its lull and gentle end. It’s the album’s own “Z Twig,” and it does exactly what the title promises: digital warmth.

Elsewhere, “Geosat Fill” is short but makes room for perky drum-rolls, an eager bass-line, and skippy keyboards; “Is Empty”’s synths reach for the clouds; and “Emulator Fill” contrasts sustained keyboards with a squiggly, uncontainable bass line. And though the drum programming is often late-’90s techno, Walley experiments with darker-textured drums that sound like they’re coming from out of water on “External Adjustment,” the shortest song here. All that being said, “Swap File”—the album’s longest song, clocking in at nearly six minutes—is the highlight: bass and keyboards being clipped off give the song an uneasy feeling before a loud drum shifts everything into focus, eventually leading into a pretty synth melody.

In the past few weeks, I’ve seen an IDM meme circulating around, depicting seniors arguing about which IDM act is best. Funny! But it also highlights a problem with discourse about the genre, which is how it’s always the same five or six artists: Aphex Twin, Autechre, Boards of Canada, Squarepusher, Venetian Snares. Dig deeper and you’ll might get so lucky with a few of Richard James’s various aliases, but don’t assume that’s all there is to it—there’s so much more to discover. —Marshall Gu

Listen to Reference at YouTube.

Bernhard Günter - Brown, Blue, Brown on Blue (For Mark Rothko) (Trente Oiseaux)

Bernhard Günter’s Trente Tiseaux label is a key landmark in experimental music throughout the late ’90s and early ’00s. During this time, Günter went from crazy pioneer to established master, and this record marks a bit of a watershed, slowly replacing texture for harmony and achieving subtle emotional undercurrents in what was previously a highly abstract world of sound. While still very quiet, this aesthetic shift was huge, and after this release he went on to pursue a new world in which harmony was as important as time and texture.

On Brown, Blue, Brown on Blue (For Mark Rothko), he was still in full-fledged mode, uncompromising in his vision and clarity of purpose. It could be said that by the time this record came out, he had said all that he had to say. I felt this was a legit avenue of exploration that felt natural given his previous output, a piece of music that was a bit somber but very rewarding nonetheless, and I went along with this new direction for a while until his emphasis on the cellotar (as the name implies, a mixture between a guitar and a cello) rendered his music too monochromatic for my taste. Günter is one artist who is prime for reevaluation, and a reminder that the music labelled as microsound wasn’t invented by Steve Roden; there are links between the Wandelweiser sound and the electroacoustic milieu that are important enough to highlight. —Gil Sansón

Shiina Ringo - Shōso Strip (Toshiba EMI / Virgin)

The lyric that echoes the loudest throughout Shiina Ringo’s Shōso Strip is from her shrieking chorus of “Tsumi To Batsu”: “Don’t love this disturbing scream.” Despite her wishes, fans couldn’t help but flock to her voice and the follow-up to her platinum-certified debut; the album ended up number one for three weeks on the Oricon, beating pop giants of the time like Morning Musume and SPEED. The rock music in her sophomore record couldn’t be more opposite than the idol pop of the latter groups. Her voice trembled more abrasive as it laid bare a series of pained emotions, and the guitars roared just as raw. If she was trying to destroy this prevailing reputation of herself as a tortured artist, the darker music of Shōso Strip only deepened the myth.

Shōso Strip’s elaborate production choices—from noisy guitar feedback and garbled mic static—set up an aura of more complex musicality, but they also signal an effort to distract from her vulnerable feelings exposed on the lyric sheet. Shiina voices deep insecurities and messy desire, the knotted intensity of both expressed so fittingly through her sharp, piercing vocals. While she favors more obtuse language for her lyrics, perhaps to further obscure her thoughts, it’s the simple pop lines that really sink its teeth. “Call me by my name / Touch my body / This is all I need / Acknowledge me,” she sings in “Tsumi To Batsu,” right after she warns about her disturbing screams. The music is perpetually in a state of push and pull, Shiina resisting against outsiders as much as she’s seeking their validation. But the more she fortifies her wall, the more she draws people in. —Ryo Miyauchi

Listen to “Honnō” at YouTube.

Akino Arai - Furu Platinum (Victor Entertainment)

Working with Hisaaki Hogari (½ of Karak), who had previously heavily contributed to her previous album Sora no Niwa, Akino Arai continues in the same eclectic style on Furu Platinum. The album contains everything from upbeat electronic pop to new age-y soundscapes, and Arai wrote all of the songs here except for the lyrics to “Rêve,” which is sung in French. Arai’s soft vocals and the underlying ethereal atmosphere helps tie things together despite the sprawling styles and production choices. In an unusual move by the record label, the album was released without any singles.

It also starts out in an unusual way; a poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, read in Russian by a male voice. “Sputnik,” the first track, is a sad song that references the fate of Laika, the dog who was sent to space by the Soviet space program, as a metaphor for loneliness and isolation. The production on many of the songs is heavily processed, and this is a good example of that. The tingly background percussion looping throughout the track, a very controlled shoegaze-y guitar wailing in the distance over the rhythm guitar. A steady drum beat only appears at the climax of the song, four minutes in.

The range, both in mood and production, is outstanding. The soft new age track “Ai no Ondo” (愛の温度, lit. “Temperature of Love”) lulls you into a subaquatic dream. Four minutes later, you’re treated to a sudden shift to the most upbeat track on the album, “Rêve” (lit. “Dream”). Even the decision to have a 123 BPM house beat driving the track is sporadic; Arai described it as coincidence, a studio engineer unfamiliar with the rest of the album played it for her and she found a perfect fit for her song.

When describing the album, Arai expressed her vision for the album as being “purifying,” and listed a diverse set of abstract influences, everything from “transparent and glittering objects” to “old movies.” As vague and incorporeal as those descriptions are, they still resonate with me. Arai’s songwriting feels personal, distant and dreamlike at the same time, and maybe “purifying” is the best way to put it. —Rose

Listen to “Ai no Ondo” at YouTube.

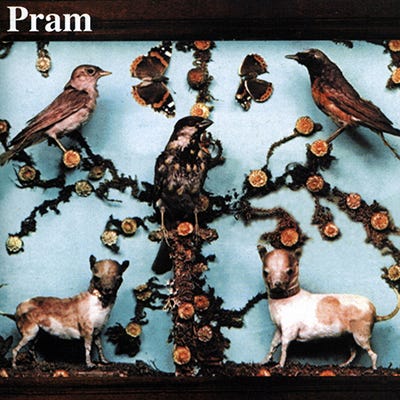

Pram - The Museum of Imaginary Animals (Domino)

The first house I lived in growing up had a pendulum clock hanging in the entranceway. Its glass casing was angled in such a way that, every morning, light from our front door and windows passed through it and the refracted beams would leave a rainbow on the wood floor and adjacent wall. When I was a child it felt to me like a sign, an indication of a good day. Looking back now, it’s hard not to feel bad for a kid who so wholesomely believed in such an innocent morning ritual as a cosmic mark of hope, knowing at some point reality would come to dissuade from that level of wonder. Like many nursery rhymes or folktales, such not-so-whimsical—and often dark—origins and messages unveil themselves as you age.

The Museum of Imaginary Animals is full of soundscapes featuring an eccentric collection of toy box sounds and bubbly psychedelic instrumentation. They take you away into an atmosphere of make-believe and wistfulness that’s radiant and fragile, and the fragility of the world both imaginary and real are reflected in its surreal lyrics. The antique eeriness and the juvenile playfulness are balanced perfectly; you float through each effervescent track with a slight unease, knowing any moment is the moment everything could sour. I can’t help but think of my naïve former self looking at artificial rainbows, spending the day playing in a world outside my own, wondering when the clock’s glass broke and left me like everyone else in this world of knowing better. —Evan Welsh

Purchase Museum of Imaginary Animals at Bandcamp.

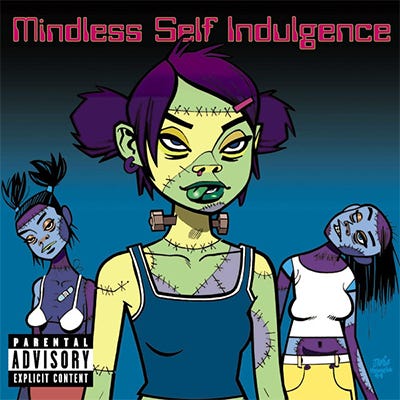

Mindless Self Indulgence - Frankenstein Girls Will Seem Strangely Sexy (Elektra)

To talk about Mindless Self Indulgence in 2020, we must first talk about TikTok. “Faggot” has become a meme on the platform, prompting eager zoomers to put on their best Harley Quinn and Danganronpa cosplays and discover a band that was tailor-made for them more than 20 years ago. Jimmy Urine even made a reaction video to the explosion of MSI videos, voicing pleasure in his loud Warped Tour accent about how furries and nu-scene kids enjoy his music. This is the logical endgame for the band, the youth of today rehabilitating the absurd subculture that was discarded years ago, Invader Zim and neon makeup and all. Frankenstein Girls Seem Strangely Sexy is the climax of this cringe epicenter, Urine called it “Industrial Jungle Pussy Punk,” a truly apt descriptor if there ever was one.

If this is all off-putting to you, it’s understandable. Mindless Self Indulgence is edgy middle school shit, filled with lyrics about jacking off midgets and Urine’s laughable AAVE interspersed on almost every song. It’s this juvenilia that the album cannot live without, though. Beats bounce off the walls, mostly programmed by Urine himself, who deftly makes electrorave breakbeats intertwine with his voice perfectly. It’s a tight balancing act that’s handled impressively considering how unserious the band is. The slick production may be indebted to the hundreds of thousands of dollars Elektra threw at the band, which in hindsight sounds remarkably stupid, but is also a testament to MSI’s electrifying presence.

There’s little regard to genre on Frankenstein Girls, with MSI instead crafting their own little universe, but their pop instincts always shine throughout. “Planet of the Apes” and “I Hate Jimmy Page” are anthemic in a totally twisted way, while “Bitches” is an AMV classic, getting adolescents to giggle with glee at how silly the song is. Elsewhere, “Clarissa” and “Cocaine and Toupees”’s electropunk could easily start a mosh pit as well as it could slot into a ghettotech DJ set. They never wear their influences on their sleeve, but there’s nods to DJ Assault, Atari Teenage Riot, Ministry, and Wu-Tang Clan, among others. It’s a cornucopia of digital beatmaking and showmanship, the turntable being unleashed amidst an eager backing band.

I think Mindless Self Indulgence is one of those bands that are essentially critic-proof. They created their own niche and happily play in it with no interest in third parties. It’s by this metric that Frankenstein Girls excels without parallel. One of the most unselfconscious records I’ve ever heard, it dares you to accept it on its own terms and relinquish any inhibitions. You must set aside any ego and cynicism, indulging the most base, primal impulses in order to truly embrace Mindless Self Indulgence. The scene kids were right about this one. —Eli Schoop

Listen to “I Hate Jimmy Page” at YouTube.

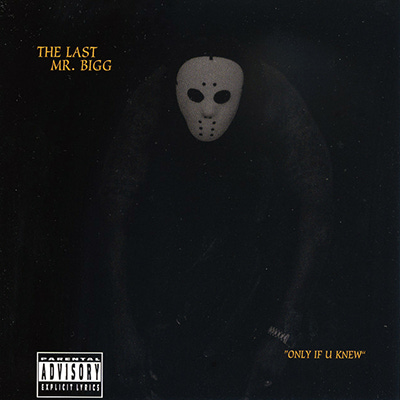

The Last Mr. Bigg - Only If U Knew (Warlock)

I got to make a plan cause them laws is on my ass

I just got a bird and I gotta sell it fast

They know about the down payments on my third house

They know about the diamond in my lil’ sister mouth

They know about the Benz and the black Pathfinder

They know about the vacation trip I took to China

They know about the ho I was fucking named Cathy

If we look through the proper historical lens we can clearly see how gangster rap was a major innovation in the history of American crime fiction: the lone antihero caught between opposing forces, relying only on his cunning to survive; the portrait of life on the fringes of society; the lovingly explained, true-to-life details of criminal enterprise; the unerring machismo; the reliance on prurient subject matter and lurid cover art to market to middle-class, mostly white consumers. All of these stylistic trademarks can be traced in some form or another to hardboiled crime fiction, but, crucially, gangster rap tweaked the formula by explicitly foregrounding racial politics and aesthetics into its narratives, tightly embedding race into the very format of the genre in a way crime fiction never had before. These elements all add up to making gangster rap one of the most uniquely American of art forms, sometimes requiring the unpacking of layers and layers of history and regional context to understand even simple punchlines.

I ain’t got no motherfucking friends

I don’t know no king and I don’t own no motherfucking pen

But just like any art form the number of rappers whose work can stand up to this sustained level of critical scrutiny are few and far between. If any rappers deserve this level of literary respect, Donald Pears aka The Last Mr. Bigg must be counted among them. Though a regional star in his time, Pears never received nor courted the kind of recognition his talent deserved, and when he passed away in 2015 he was best remembered for collaborating on a few songs with Three 6 Mafia. What he should be remembered for is producing some of the most distinctive and well-written records to ever be designated gangster rap.

Your folks all in church telling all kinds of lies

“Oooh I had a good baby who didn’t deserve to die”

Only If U Knew, his first album, wound up being the most focused in his short career.* It follows the near-mythical Mr. Bigg through years of his criminal career, each song not only continuing an oblique narrative but also giving us a new angle on the character: he’s a cunning and cruel crime lord, a devoted father, a proud Black southerner; he’s an inveterate misogynist, a neurotic mess, a desperate hustler. The model of a classic antihero, he passionately contradicts himself at every turn. And since this is an album that is both by and about The Last Mr. Bigg, we hear these stories all straight from his mouth.

Lent my mama $20,000 for my babies and the bill money

I’m in the attic smoking weed cause I think this shit is still funny

Make ’em kill me or turn myself in, shit

I’m facing life in the goddamned pen

The beats on Only If U Knew are rarely more complex than a bassline, a drum pattern, and a short, looping sample, but this simplicity is key. Not only is it insistently catchy, it grants Pears’s voice ample room to stretch out; he favors lengthy songs, lengthy verses, and few guest stars, all of which allow his personality to ring out to maximum effect. And Pears is definitely the star of the show here.

I had to leave my daughter, I had to leave my son

I’m 3000 miles sick, lost, and all alone

I wanna call my momma but I know they tapped the phone

I’m paranoid in the closet smoking weed and taking pills

I’m thinking about all the shit I did

My eyes water up, sometimes I even cry

I’m writing me letters asking myself why?

There’s much more that could be said here that I have barely touched on—how funny Pears is, how devoted he is to his family, how cleverly and bitterly he comments on the violent racism of the police state—but this is already far too long of a blurb. So allow me simply to say RIP Diamond Eye: one of the best rappers who ever played the game. —Samuel McLemore

*Pears was shot in the head twice and left for dead in a robbery shortly after the release of his excellent second album, The Mask is Off. Though he survived, and even continued to write and perform music until just before his death, he never released a proper follow up to his first two albums.

Listen to “Trial Time” at YouTube.

Ayuo - Izutsu (Tzadik)

By the time he turned 20, Ayuo Takahashi had played synthesizer with Ryuichi Sakamoto, studied composition with Joji Yuasa, and played guitar in the legendary noise rock band Fushitsusha. Having accomplished all this, Ayuo turned in yet another direction, spending much of the ’80s and ’90s developing his own fusion of pop melodies and extravagant, orchestral instrumentation, and incorporating both Japanese and Western instruments. The result encapsulated all of his diverse interests, simultaneously: a single track might feature both electric guitar and biwa, opera singers and choirs, pipe organ, marimbas, ryūtekis, harps, and synthesizers—all drenched, of course, in plenty of flange and reverb.

Then, Ayuo’s focus turned again. Izutsu is more subdued than most of his ’90s output, generally paring back the instrumentation to a more traditional Japanese ensemble—and one electric guitar. Still, from the first moments of “Taiyo,” one feels that same, total lavishness, like sinking down to your neck in a bubble bath. Multitracked vocals lap against themselves, as the plucked instrumentation coils around and around itself without really developing: it’s just twelve minutes of bliss. There are two more, shorter tracks before the main event—a total rescoring of the classic nōh drama, Izutsu.

Izutsu, the play, is a drama with two characters and a single prop: a well-cradle (the wooden frame surrounding the mouth of a well) to which some reeds of flowering pampas grass are tied. Though this minimal setup has sufficed largely unchanged for six hundred years, some stagings strip it back even further, replacing the well-cradle with a single green stalk of grass. The traditional scoring of the drama is, like all nōh plays, austere in the extreme, constrained by rigid formal rules which dictate every word, sound and movement. Nevertheless, it is a masterpiece of concision—heartbreaking, philosophical, with some dated and some surprisingly modern themes. Ayuo reimagines the score with lilting, minor-key melodies and wispy drones which emphasize the mysterious, mournful sense of the text, and which would be unthinkable in a traditional nōh staging. Likewise, in a total reversal of the nōh tradition of having all-male singers, players and actors, Ayuo has given all the vocal and instrumental parts to a cast of immensely talented women.

In the play, a monk stops at the Ariwara temple, where he meets a beautiful woman who has brought an offering. She tells him a story about Ariwara and his wife, Izutsu. The two had been friends since childhood, marking their growing heights against the well-cradle. Though they grew to maturity, fell in love and married, Ariwara eventually began an affair, assuming his wife would also take a lover during his absent nights. One stormy night, Ariwara doubles back to sneak a glance at his wife’s lover, only to see her alone, worrying for her husband’s safety in the bad weather. Ariwara immediately loses interest in any affairs, and the two spend the rest of their lives in loving joy.

The woman eventually reveals to the monk that she is Izutsu, the spirit of the woman who was so faithful to Ariwara, that she still attends to his temple, uncounted centuries later. She laments:

the song of pines / alone is heard / while gale winds blow / all ways changing / life goes on / and lived in dream

The spirit of Izutsu has watched over the centuries as—though his name is preserved by the Ariwara temple—her husband’s memory fades into obscurity. It has been the fate of many great people (hitherto, mostly men) to eventually become nothing but the name on a building. Streets and cities, too, bear the names of people who were once loved and hated, who had bad days and back pain. Some, if they are lucky, may be the subjects of obscure biographies, themselves decades or centuries out of print. In my work, I have come across many such biographies from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—of small-town politicians, academics, journalists and activists. People who surely changed lives, but whose own lives are now forgotten.

Izutsu longs not for the memory, but for the man, her husband. She reveals the true reason her spirit returns again and again to the temple—not because the temple bears his name, but because it bears his body:

in name alone lasts: Ariwara Temple, his trace, grows old / Ariwara Temple, his trace, grows old / and the pine grown / from the mound's weeds… / His grave it is

Ayuo’s score is at its most spare here, consisting sometimes only of a plucked melody on koto. Voices emerge as out of fog. Though my Japanese has long since dwindled beyond the point of comprehending what is sung, the singers bring a nuance which allows anyone to follow the general plot of the text. Over the twelve tracks, they shift from the icy reserve appropriate to a strange and unknown figure, to a more melodic and forlorn register as Izutsu gradually discloses more and more layers of her love and sorrow.

This album is unlike anything else in Ayuo’s discography. Though he rescored another nōh drama, Aoi no Ue, on a very good 2005 album, it does not match Izutsu’s simultaneous clarity of focus and breadth of vision. With this album, Ayuo takes one masterpiece and crafts another, bringing a classic of Japanese drama vividly back to life. —Mark Cutler

Listen to Izutsu at YouTube.

Diane Cluck - Diane Cluck (self-released)

Few songwriters accomplish intimacy with as much patience and subtlety as Diana Cluck at the start of her debut. Over a spacious, rollicking piano (miked with warmth and a woody room tone), Cluck incants a portrait of her lover, “Someone’s ink and needles / Have written skin riddles / On his body bare before me except for these sketches.” On this early release, Cluck’s songwriting is skillful and fiery, unabashed and sincere. Here, Cluck, so adept with language and at channeling her interior emotions, draws attention to her lover’s shuttered nature. His tattoos, “Signal and semaphore / For things he won’t talk about,” providing a sole entryway as Cluck traces them, bridging the rupture that sits between them. Across the album, Cluck shows herself to be particularly in tune and empathetic to the world around her (an empathy that extends, on “Ambulance,” to an ambulance passenger considering the anger of those behind them in a traffic jam as they breathe their last breath).

Likewise, Cluck buries meaning in “Psu Vs. Louisiana Tech (67 to 7, 9/9/00),” which takes form as a birthday voicemail. The song keenly reflects the way conversations dance in a stifled and distanced relationship: “I talked to Barbara tonight on the phone / She told me Penn State has finally won / so I guess they don’t stink as bad as you said / and your birthday wish came true for you today, dad / Happy birthday, dad / happy birthday, dad.” As listeners, we will not find the source of emotional brunt yet we are sure to sense the vulnerability and tenderness within.

The songs here are sunbathed and sticky, humid, dense. Figures lay about, lethargic, dreary, and wet, always conscious though briefly negligent of the world just outside their window. “Monte Carlo”—a barebones, three-chord, hazy epic—describes its namesake ward as a particular sort of liminal space, a realm of excess and tire, exhaust and sweat. It opens with an image that wouldn’t be out of place in an Agnes Varda film, lingering on “the three lonely things poking up from the water/ …her nipples and her nose as she floats on her back.” As Varda has a penchant for pointing outside of her protagonist’s plot-lines, so too does Cluck. “Monte Carlo” brilliantly oscillates between social scenarios about town, geographic landscapes, and intimate domestic scenarios, the singer blowing on her lover’s sunburn blisters in bed to cool them down, concluding this moment of intimacy with an acute metonymy: “that’s the sun in Monte Carlo.” The song is lugubrious in a cosmic sense, inhabiting a land with pleasure and dread.

In another’s hands, such a setting might nosedive towards a purely romantic fantasy ballad, but a horror upsets the singer as she describes a place where acts have “no consequence at all / like the action in dreams.” Meanwhile, she and her lover toy with a lighthouse beam sending ships off course and crashing in the middle of the night (an act of terror that receives equal attention as the scene described in the song’s closing couplet: “Two more nights in Monte Carlo, and her burn will be a tan / She can’t sleep, she just said so, so I turn up the fan”).

The production across Diane Cluck is alternately charming and vibrant in its psychoacoustic distortion and textured pastiche of elements. On “4 Score Lightnings,” for instance, the rapid-fire piano that serves as the song’s base is recorded in a washy style, rounded-off and warbling, while Cluck strikes above, weaving through the atmosphere heavily effected by chorus, painting ions in the ether, and animating the effect of lightening so, “blinding, frightening,” that electrifies perception allowing for something like “x-ray view.” When an accordion enters crisply it inhabits a completely different sonic space than both the vocals and piano, introducing a third sonic plane that is incongruous but vivid, the effect gives depth to her minimal arrangements.

With “Touch Deprivation,” Cluck anticipates the hyperattentive, stylized, tweet-speak poetry of her Alt-Lit successors, as her speaker brushes another on the subway and allows all-too-candidly, “Do you know you are the first person to touch me in a while / and sometimes I like the feeling of accidental touch.” But while her anti-folk peers (and Alt-Lit co-predecessors) Regina Spektor, Kimya Dawson, and Jeffrey Lewis shone brightest when their lyrics took the form of a stream of transcribed thought (glazed with the patina of familiarity and conversational tics, tracing an internal monologue and stretching the limits of the confessional song in the process), Cluck’s lyrics are distinctively stylized as a realist novelist might be, and her incorporation of symbols is acrobatic and strange, belying meaning but speaking through images themselves. —Leah B. Levinson

Purchase Diane Cluck at Bandcamp.

Mary Timony - Mountains (Matador)

After spending the ’90s styling herself a mad-as-hell superball with a taste for twisted guitar tones as the frontwoman for alt-rock band Helium, Mary Timony grew oddly quiet on her first solo LP, Mountains. The record opens with “Dungeon Dance,” a song made up of a simple melody pounded out on unadorned piano over which Timony entreats the estranged object of her affection to join her in a danse macabre “under the midnight sky.” She points out two stars and calls them by name: “One is sadness, one is misery.” And so it goes on Mountains, a record of unyielding sadness communicated via the delicate language of fairy tales and stripped back instrumentation that’s almost supplicant in its vulnerability. It was such a tonal left-turn for Timony that it’s hardly any wonder why Mountains was greeted with so little fanfare upon its release and why it remains unheralded even now that she’s returned to the public consciousness with the success of Ex Hex. It’s just so sad and weird.

While Helium often indulged in proggish whimsy, especially in their later years, they were always a rock band first and foremost, and so could suit any number of critical pre-conceptions despite wonky chord changes and lyrics about apple trees and dragons. Though similarly proggy and voluble, the bare-faced strangeness of Mountains had no real peers in its time and still doesn’t. That said, one can’t help but feel that modern audiences teethed on the orchestrated filigree of Joanna Newsom might be more receptive to Mountains than critics were at the time of its release, when they reduced Timony’s articulations of pain wrapped in fantastical metaphors to images of her warbling prettily beneath a weeping willow tree.

What a shame, for Mountains is a masterpiece of fearless internal excavation, an illuminated book of sorrows so deeply personal it feels almost intrusive to listen except that it’s so honest about its longing to be understood. Despite the record’s heavy use of tarot card symbolism—poison moons and darkening waves and ringing bells and trees that call to no one—Mountains is not a puzzle box without a key. The imagery may be fanciful, but it's also straightforward in ways it delineates every shade of heartbreak. With patient listening its melancholy truths unfurl like the flower of perpetual bloom that Timony sings of on the beautiful “Valley of 1,000 Perfumes,” a song that balances brutal expressions of self-hatred (“Why can’t you see that the best part of me / Is a rock in a hole after the third world war?”) with bleak expressions of futile love (“Don’t you know how much you mean to me / It makes me want to kill myself peacefully”), her voice floating clear as a bell over spidery guitar lines that glint like shattered stained glass.

Perhaps there is no escaping the shadows that fall so relentlessly across this lonely musical dreamworld, ringed as it is by “the mountains of misery” of the title, but there is a sense of grace in the bravery it takes to try—and by the end of the journey, Timony finds herself once again looking at the stars twinkling in a sky “the color of the robin’s egg.” In retrospect it seems obvious why such mournful, unidealized sentiments would need to be communicated via such potent, poetic imagery paired with such fragmented and hallucinatory music—anything less would’ve been too painful to bear. —Mariana Timony

(And in case you were wondering: a) yes, I know, b) no, we are not and c) the answer to your question is here.)

Listen to Mountains at YouTube.

Still from Ritual (Hideaki Anno, 2000)

Thank you for reading the thirtieth issue of Tone Glow. Write about music that doesn’t get written about, love music that doesn’t get loved enough.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.