KMRU

KMRU (aka Joseph Kamaru) is an ambient musician from Nairobi, Kenya. He recently released two albums, Peel on Editions Mego and Opaquer on Dagoretti, and has performed at CTM Festival, GAMMA Festival, and Nyege Nyege Festival throughout the past few years. Joshua Minsoo Kim and KMRU talked on the phone via WhatsApp on August 13th, 2020 to discuss his music, field recording, the electronic music scene in Kenya, and his grandfather—a famous musician whom KMRU was named after.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello?

KMRU: Hello! Hi!

Is this Joseph?

Yes, this is Joseph.

How are you?

I’m good, how are you?

It’s early in the morning but I can’t complain. I love waking up early.

Where are you based?

I’m around Chicago. It’s 7:30AM, which isn’t super early, but it’s earlier than I’ve been waking up recently.

Ah, over here it’s 3:30PM.

How has your day been?

It’s been calm, I just finished making a mix I was supposed to make. I was working on it yesterday night too. It’s been a really calm day.

Even talking with you right now and hearing your voice, you sound like a very calm person. Would you say that’s true?

(laughs). Yeah, I’m a very introverted person. I’m… calm (laughs).

Do you feel like being introverted or quiet helps you as an artist?

For me, it’s about being in a space where I’m able to understand myself more. With my music and what I’m doing, being introverted helps me when I’m listening, when I’m outside and appreciating everything fully.

What’s something you’ve come to understand about yourself recently?

I never used to go out much before the pandemic, but now that I’m forced to stay inside my home, I’ve come to learn that I’m more comfortable in this space and environment where I’m not with so many people, when I’m just with family and a few friends. I’m so much more productive this way. I’m not doing much outside my home—I stay home working on my projects, finishing stuff that I need to do.

What are you most proud of that you’ve been able to get done this year?

Earlier this year, in February, I had so much going on. I had my application for my master’s and had deadlines for different projects so I decided to make a schedule—it was a really intense month. I was going to travel later in February so I needed to finish my application before I left, and being able to accomplish all I did, including going to Montreal and preparing a project for that, was a really big accomplishment for me.

I remember that I didn’t leave the house for like 36 days because I needed to work on all I needed to do. I was really grateful because I got into my master’s, the Montreal project went well, and I did other projects I was working on too. When I’m working on something, I usually don’t want to disappoint everyone so it was super hectic but I managed to hack it.

That’s a lot you got done. Are you starting the master’s program soon?

Yeah, I start in October. I applied for a master’s in sound studies at Universität der Künste Berlin. I got my decision this week!

Wow, congratulations! That’s super exciting. You said you were in Montreal and I know that your album on Editions Mego, Peel, was inspired by your time there. What was it like being there—was this at the [Mutek Montreal] AI lab? Had you ever visited Montreal before?

Yeah this was for the AI lab. I hadn’t visited Montreal before but the people who were facilitating the Mutek lab were people I had been in contact with, like Peter Kirn and Natalia Fuchs, who runs the GAMMA festival. I had been a part of the lab since last year. Montreal was super cool and I really liked the vibe of the place, but it was super cold and I wasn’t ready for that (laughter).

The lab was a really great learning experience for me because it was only last year that I was introduced to machine learning. It was really about experimenting and figuring out how the systems worked. It’s been a year of studying and reading and working on different projects using these tools and, for Montreal, I had a proposal idea for an installation project that involved machine learning. I ended up collaborating with artists on the project, we did a showcase but it’s still developing and ongoing.

Who were the artists you were collaborating for this?

Moisés Horta from Mexico, who is based in Berlin—he’s a sound artist. And also Damian T. Dziwis, who is based in Germany.

You were describing Montreal and what it was like to be there—how would you describe Nairobi? Did you grow up and live there your whole life?

Yeah, I was born and raised here. I like how things are super fast compared to other parts of the country. It’s quite slow near the oceanside, and it’s the same thing in Uganda, but in Nairobi you have to be on your toes. I was raised a few kilometers away from the main city and my parents moved out to where we’re staying right now in Rongai, which is super calm.

The shift really influenced much of what I’m doing right now. I was just telling my siblings that if we were still there, I probably wouldn’t be making music. The surroundings here are quite silent, there’s no noise, there are so many trees and birds come and wake me up in the morning at my window. I can be connected and in touch with my environment, which leads me to listening more.

You utilize field recordings in some your songs—how often do you find yourself recording your environment?

Initially, I was doing it a lot because I was learning that the environment I was living in had so many sounds I was missing out on. When I bought my recorder—my Zoom—two or three years ago, I realized how much I was missing with the sounds in my house and just outside. I used to quickly make recordings in the field: I’d take my recorder, investigate my surroundings, and find different sounds. It was mostly just to listen, not to use them as compositional tools. Later, I ended up using them, sampling them, breaking them down, and finding ideas that I could come home and mess around with.

I like how you said you initially did it to listen. I have a Zoom too and I used to record a lot, and even just turning it on puts me in a mindset to listen to my surroundings more closely. Can you give me an example of a time when you were recording a space and got a better understanding of it despite it being familiar to you beforehand?

When I was going out before the pandemic, I used to carry my recorder with me. There’s this place where the Uber drops me off and I have to walk 300 meters to my gate, and this could be at 3AM or 4AM when it’s super dark. I would take out my phone or my recorder and just record myself walking—hearing my footsteps while walking down different paths was really interesting for me. I’ve used this in different pieces I’ve written where I just leave the recording. For example, if it’s a four minute recording, I’ll use that as the basis for the composition—I won’t change anything from the recording, I’ll just write a piece for that.

I used to drive away from home outside Nairobi without having a clear destination or thing I was looking for. I would just find a location and record this space I’d never been in and come back home to listen back to everything. I also used to teach classical guitar and I would have listening sessions with my students. One time my student was wearing a leather jacket and he started rubbing the strings on his guitar and it sounded like a train, and I recorded that (laughs).

When did you teach classical guitar?

When I was at Kenyatta University I was playing classical guitar. I did private lessons for students part time during my studies.

Do you play any other instruments?

I used to play bass and very little piano. I also used to sing but I stopped (laughs). It’s been changing because when I went to uni, I thought I was really good at playing guitar. Then I met really good guitarists and said, “Oh, I need to drop this instrument” (laughter).

Oh, no! (laughter).

I picked up the classical guitar because no one in my class was playing it. I started from scratch and it was very restrictive but I really enjoyed it and reading sheet music. Along the way, I used to borrow my dad’s laptop for assignments and that’s when I was introduced to DAWs and, while I continued to play guitar, I was experimenting with FL Studio and Ableton.

What brought you to making ambient and electronic music in general? You mentioned how you stopped playing guitar because you met people who were really good—was this because of that?

For me, I didn’t know that you could make music on a computer. When I got FL Studio, it was just nice that I could record myself playing guitar on the laptop and play it back. I was initially making dance music and experimenting with what I could do.

The shift of being in a new place, being more connected with my surroundings, and getting my recorder—it all really wasn’t intentional, I was just enjoying listening to the field recordings I made and that’s when I discovered all this music. It made me happy to find more adventurous sounds in electronic music, and then I just started making music with no drums.

Do you feel pressure to make sure you stand out, that sounds very different from what’s happening? Or do you just make what you want to make?

There was pressure for me to be really good at what I was doing. In Nairobi, I felt the pressure at first because when I was getting gigs—back then I was DJing and playing techno and house—I also wanted to include the music I was making in my sets. When I did that, people didn’t really get what I was doing so I had that pressure of trying to make people understand and enjoy what I was making. I decided that I would just make this music and see how it would go—I’m happy I made that decision, and if people don’t like it it’s fine, but I like that people in Nairobi know that I’m making this music here.

When I’m playing in Nairobi, there’s usually a tension I have on stage that I don’t get elsewhere. Last year, when I was in St. Petersburg, I was slotted after Anthony Child and I was asking myself… why (laughter). But the response was so good. Coming back to Nairobi and playing the same music, people were still trying to figure out what I was doing but I’m happy because I’ve had good shows also. People have been amazed with my performances.

Can you talk to me about Nairobi’s experimental scene? What’s it like?

The experimental scene or just the general electronic scene?

You can talk about the general electronic scene.

It’s so diverse because there are so many people making different types of music. There’s a lot of house music, and a lot of techno raves happen here. But it’s hard for people who are trying to do things outside of the normal, or who are doing something adventurous, to find a gig. For myself, I either try to curate a show or try to be involved in a specific project or event that’s focusing on something particular. Generally, it’s house, Afro house, techno, hip hop—this other type of music.

But the experimental scene is growing even though it’s still small. For example, with Nyege Nyege there has been so much growth and people are getting into new sounds. It’s been one of the most motivating factors for me that I can play in the Nyege Nyege festival, and you have artists like Freddy [Njau] (Slikback), Duma, DJ Raph—people who are doing different stuff compared to the normal electronic music sound.

Do you regularly keep in touch with artists from Kenya?

Yeah. Last year, I started a workshop called the Nairobi Ableton User Group and it became a space for people to meet and interact and share ideas. I knew most of the producers locally were making music in their bedrooms and just uploading, but we hadn’t met one another.

Slikback is in Uganda at the moment but we meet when he’s not on tour. And for me, it’s just about seeing everyone grow together—it can be hard trying it all out on your own. It’s more about the community than myself.

What’s something you feel you’ve specifically learned from being a part of this community?

In this user group, I learned that people really want to be together. I feel like producers are really lonely people (laughter). When the workshops were happening, I was super happy just seeing people talking and sharing ideas and it started small but it grew to like 30 people and we’re just learning together. The workshop was monthly and it was something new. I was always learning from people who were coming in and we would build confidence just speaking in front of each other and performing and making music.

It definitely seems like you’re always trying to learn new things. Is there anything you’re working on right now to really learn?

I’ve been learning Max and it’s been more than six months now. It takes up so much of my time and it’s super technical. I can do stuff inside it but I want to be good at it but the learning curve… it’s been really long, which I haven’t been happy about. There’s also the visual side of music. Last year, I was working on my installation and I wanted to have a visual concept for it. I have an artist I’m working with but he’s also busy so I learned how to do stuff myself and that’s been time-consuming too. I just want to learn how to do my own visuals now.

How old are you?

I’m 23.

You’re so young, you have a whole life ahead of you!

Ha, yeah.

So you have a new album coming out tomorrow called Opaquer on Dagoretti. I remember checking out the earliest stuff on your Bandcamp and you had like an ’80s dance track you had made. And then of course you ended up making ambient and electronic music. Opaquer, even compared to Peel and the releases you’ve had before, has a lot of variety. How did you go about approaching the creation of this album? Did you specifically have goals for things to be varied?

Opaquer was actually made last year and was due to be released earlier this year but the whole pandemic pushed it back. Last year, I was really experimenting a lot because it was the first time I traveled to Berlin for CTM and there was so much music I was exposed to. Watching people perform all this music was really intriguing and I was so happy that there was this community. When I went home I started experimenting with stuff I wouldn’t usually do.

At the MusicMakers Hacklab [at CTM], I remember working with a friend of mine—we were working on a piece for our performance—and I let her take charge. I saw her workflow and how she was working with Ableton and how open-minded she was. I was making lots of lots of music and Dagoretti reached out at the last quarter of the year and I put this collection of tracks together for the record.

Is there a particular track on the album you were especially proud of making?

I was happy with how “Lulla” turned out. And “Lost Ones,” which was quite romantic, and also “Dialog Needs.”

I wanted to ask questions about your grandfather, Joseph Kamaru, and your family. I’m assuming your family was pretty musical growing up?

(laughs). Not really.

Just your grandfather?

My brother played piano but he does actuarial science. I only have two siblings, and my younger brother is still in high school. Sometimes he comes and tries to learn the software or guitar. I really tried to encourage him to learn music when he was in school but he decided not to. I’m the only one doing music full-time, but there was also my grandfather.

How close were you with your grandfather growing up? I know you’ve talked about him for Bandcamp Daily. What are some memories you have with your grandfather?

I remember that as a child, I knew he was a musician but I didn’t know that he was a big one because he was family. I just thought he was a regular musician. Way later, when he was in his ’70s, was when we connected. Even when I was younger we used to go to his home—he stayed in Nairobi also. When we went to the countryside we would go together, when we would go to my grandmother’s place he would come for events and family occasions.

In my university years I got more into his music because I was getting a music degree. He was one of the subjects in some units. This led to my lecturers really knowing me and people would always ask, “Where’s Kamaru?” (laughter). It was so bad because if I missed a class everyone would know (laughter). When I was in uni I used to go to his place and learn more about playing guitar from one of his bandmates, Lenny, and we were jamming together.

We had ensemble performances in my university where we were studying different music and cultures and instruments. For my final year I did one of my grandfather’s songs but using Ableton and electronic music and traditional Kikuyu music. It really impressed my professors and lecturers. I had to teach my classmates the lyrics and provide context for the whole performance. I was happy about the outcome.

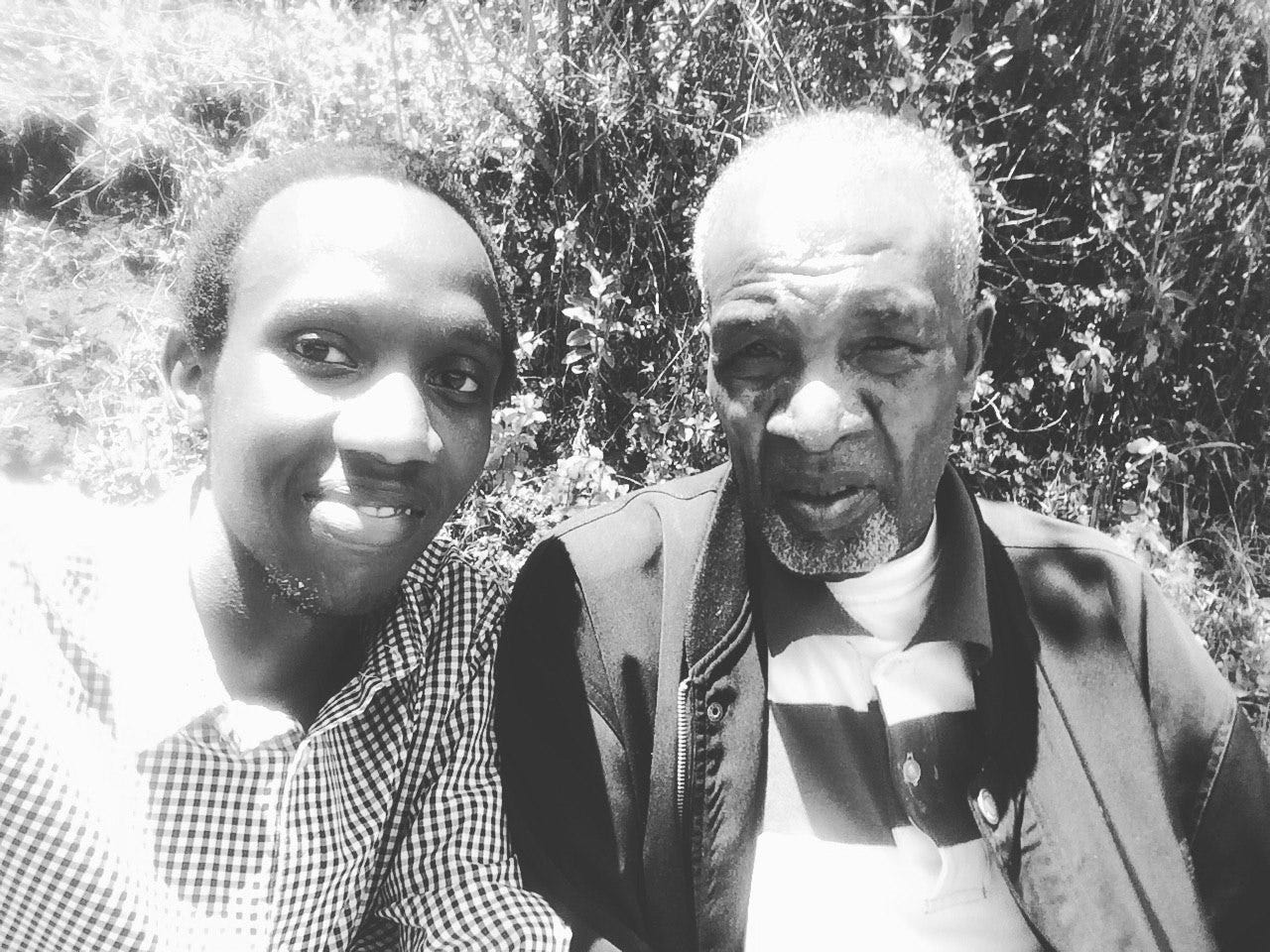

In the later years, my grandfather used to come a lot to my mom’s home—my mom is his daughter—and we just chatted about life and music because I was the only grandchild who was doing music full-time. Coincidentally, I was given his name as my first name. We were actually supposed to be working on music together. He had written a song for me that he wanted me to sing, and we were gonna perform it together. And I also wanted to work with him in the studio.

When he passed, I decided to do the reissue project. He really wanted a space where musicians could come and record, but when he passed, the extended family also wanted an archival space where people could interact with his music and read more about him. There were people uploading his music online illegally and I wasn’t happy about that. I tracked people down, mostly on YouTube, and because I had most of his works I did this archival project. Hopefully we can repress his music again on vinyl. And then maybe we can have somewhere in Nairobi where people can come and listen to his music.

A lot of your father’s music was really political and he was friends with the president, Jomo Kenyatta, for a period of time. Do you care about expressing politics in your works at all? Obviously you’re not singing in your music, but I’m wondering if it’s meant to come out in some way.

I’ve been reading about colonialism, and it’s interesting because I’ve been told that my music isn’t Kenyan. I usually write in a specific context, but that’s more so if I’m working with a physical installation. The music that I make, however, isn’t really political, no.

Did he ever talk about politics with you growing up?

When I had a question about a particular track, I did ask him about the context behind it. It’d be written somewhere that a song would be about something specific, but there’s also an inner connection or meaning from him I’d get when he would explain things to me, like with why he would sing about something.

Do you have any examples?

There’s a track, “J.M. Kariuki,” which was actually one of my favorites when I was really small. He was a member of parliament and my grandfather sang his whole story—Kariuki was murdered because so many people in Kenya liked him and Jomo Kenyatta wasn’t happy. The whole song is based on the assassination process—they cut his hand and everything, it was very gruesome. My grandfather wasn’t ever allies again with the president and this song is one that I remember well.

There’s another song, “Ndari Ya Mwarimu,” which in English translates to “Stories of the Teachers” or something. It’s based on teachers in schools who would exploit girls and this song got an award. It was a huge song that almost made the teacher’s union go on strike.

It was interesting how you said that you’ve been told your music isn’t Kenyan. And that’s something that happens a lot, and feels like a clear product of Western cultural imperialism and notions of supremacy, where people don’t consider your music to be truly Kenyan or of any particular country unless it sounds like traditional music. I’ve seen that with a lot of artists from Asian countries. Do you feel like your music is Kenyan, though?

I don’t contextualize it in that way, it’s more about expression. I can’t say it’s Kenyan music but… it’s made by a Kenyan, so it is Kenyan music (laughter). In Kenya there’s a lot of music being borrowed from South Africa and it’s also a debate because there’s no particular sound being made in Kenya that’s just from there. Last month, I was part of a panel discussion and it was about blindfolding the participants and playing music and trying to find where the origin of the music was from. I played my music and people were saying that it wasn’t from Kenya.

Does that hurt you at all when people say that?

It hasn’t happened a lot, and it’s just people’s perspectives and what they think about my music. It doesn’t hurt me at all.

What do you have coming up next in terms of music?

I have a tape release coming out hopefully next month, it’s my last one for the year—I wanted to release three projects on labels this year because I do a lot of self-releases. It’s coming out on Seil Records. That one and Peel were the main projects I was really looking forward to. I’m also looking forward to being in Berlin to study music. And then I have an installation I’m working on for Mutek Japan, and I’d also like to do a reissue of my music on vinyl next year. If you’ve been following my Bandcamp, I removed some tracks I released this year (laughter).

Nice. Is there anything else that you wanted to talk about?

I subscribed to Tone Glow last month and I was reading the interviews.

Ah, thanks so much.

But I don’t have any questions, no.

That’s all good. I’ll try to get this interview up soon. Hope you have a great evening.

Have a good morning (laughter).

Buy Peel at the Editions Mego Bandcamp. Buy Opaquer at the Dagoretti Bandcamp.

KMRU and his grandfather in Murang’a, 2018.

Thank you for reading this midweek issue of Tone Glow. Have a good evening or morning, wherever you are.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.