Tone Glow 025: Duma

An interview with Kenyan grindcore duo Duma and an accompanying mix + album downloads and our writers panel on Still House Plants's 'Fast Edit' and Duma's self-titled debut

Duma

Duma is a grindcore duo from Kenya made up of Martin Khanja aka Lord Spike Heart (vocals) and Sam Karuga (production, guitar). While both have been part of the country’s metal scene for years, their upcoming self-titled debut on Nyege Nyege Tapes places their music in both the metal world and the cacophonous electronic music being churned out by labels like SVBKVLT. Joshua Minsoo Kim called Duma via WhatsApp on July 24th to discuss their new album, the Kenyan metal scene, their mentors, and more.

Duma: Martin Khanja (left) and Sam Karuga (right)

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello Hello!

Martin Khanja: Hello it’s Martin here!

Sam Karugu: And I’m Sam!

I’ve been telling a ton of people about the album, it’s great, thanks so much.

Sam Karugu & Martin Khanja: Thanks for listening!

How did you both get into music?

Sam Karugu: For me, I used to go to a lot of shows—metal shows, classical music shows, whatever—just to listen to music. When I got into the metal scene I saw that anyone could do it, you just buy a guitar and start playing. I loved it and it was like, “Yo, this is something I wanna do.” The first instrument I got was a laptop, I had FruityLoops and started messing with it. Then I got some shitty ass guitar and started playing and then from there ended up in a lot of bands.

Martin Khanja: Yeah, for me the first show I ever played was when I was eight years old. My mom took me to a festival in a county in our town. I played that and we killed it. I got into art—drawing and painting—and then I went to school and thought about what I was gonna do. I decided to form a band and started playing vocals. I started researching how to do vocals and how to sing well, but I really liked this hardcore shit. As long as it’s hardcore, you feel like your emotions can explode.

So I was like, yeah, let’s do it. I formed my first band when I was 17 years old and then we made an album after two years or something. I never looked back—I was 17 and I’m 27 now, and I’m still going. I made a band with Sam, I made a band with friends in Kenya—we just love performing and being in the studio and making it happen.

Were there any mentors you had who really helped you grow as musicians?

Martin Khanja: Yeah there were, like one of my best friends, Sam Kiranga—but he died, yeah? He committed suicide. He showed me how to really record metal properly and we used to do it in his house. He used to be in Lust of a Dying Breed, Black Dog Angel, and Koinange Street Avengers. I met him and just started talking, and then we started recording and I really got into it because of the way he showed me how to do it. And that’s all I needed; he just advised me along the way. And then I met Leon Malu from Mortal Soul and started recording with him, and all these other artists and instrumentalists.

There’s a lot of people, and they’re doing all this crazy shit. Some of them were doing videos, some of them were doing art, some of them were doing guitar. I really just wanted to express myself and like, you know, bleed on the microphone—record proper shit that can get to people’s nerves. Subliminal, deep shit.

Sam Karugu: I would say for me that it was my first teacher in primary school when we had music classes. I wish I took these classes seriously. And also Timothy Opiko from Lust of a Dying Breed, the bassist. And also guitarist Josh “Sosuemi” [Shikanda] from Void of Belonging, and also everyone from the scene who showed me that it’s possible, that anyone who has an instrument and has heart and wants to do something—they can do it. Even the fans, everyone’s who’s moshing. And also I would say Nyege Nyege because they gave me a different perspective on what metal and heavy music could be.

Can you talk to me about the Kenyan metal scene? How long has it been around? What’s it like to go to a show?

Sam Karugu: It’s been around since… I would say back during apartheid, in the ’70s, a lot of bands who were making Zamrock—Google it, bands from Zambia and Zimbabwe—they were playing rock but then they couldn’t record, a lot of bands couldn’t record in South Africa. They mostly came to Kenya to record, so a lot of these bands with a rock sound—this was ’70s, ’80s, it even bled out to maybe the ’90s because that’s when apartheid ended.

So the scene in Kenya has been there a long time and for us, we feel like it’s been there but there’s a scene in South Africa, for example, and there’s a scene in North Africa in Tunisia and Egypt. And it’s like people forgot that we exist. But also, going to a gig in Kenya—and I don’t know, I haven’t been to many metal shows around the world—but here there’s good open people, people having fun, bands are playing, there’s a mosh pit. People are really open.

Martin Khanja: The thing in Kenya is that it’s a family, it’s a community, you know? We don’t care about how much money you’re making or what race you come from—the connection we have is really deep. You can just pull up at a show and everyone loves you, and they love you for real. They don’t even want you to change, they accept you the way you are.

And that’s something I really needed when I was making music at the beginning, because I knew that what I was doing wasn’t popular—it was something very fucking weird. And then I met all these people who fucked with it and it was like “yes, bro”—it was an escape for them too. We understand each other. When I walk into a venue it’s family. You see the same faces and, like, people I’ve met in the beginning when they were kids in high school and then in college, and then they come with all their families. It’s still the same, it’s just getting bigger and bigger. That’s something I really like about the Kenyan scene—it’s really tight, it’s like a tribe. Everyone knows everyone, and they love everyone in it. There’s no bullshit.

Sam Karugu: One thing I’ll add is that the Kenyan rock and metal scene is not mainstream. You can play a gig and get like one hundred euros, that’s like ten thousand Kenyan [shillings]. You have to share it with one whole band. We just do this because we have to do it—we love it. If you don’t do it you’re gonna run mad.

Martin Khanja: Yeah you’re gonna run mad.

Sam Karugu: It’s still not mainstream but some of the bands got a bit big. We got a radio station, we got labels working, stuff on TV—it’s there, it exists, it works. There’s a little something going on but it’s not that big, it’s a bit underground.

I like how important playing this music is to you both. How did playing metal and being in this community change your life?

Martin Khanja: Personally, for me, I had this music when I was around 17 years old and my friends were playing it on the radio. I was always trying to find my way in life, I was trying to discover stuff. I found that this music was giving me this expression, I could just be free, I could be myself.

I’ve always experienced this, where I’m walking down the road and I can hear a rhythm in my head or a poem—I write a lot. It was like, “Where can I express it? Where can I release it?” And I found a way to release it through this. Otherwise, I wouldn’t know what to do with my life. I would have no fucking purpose, man. This shit gave me something to live for, because at the end of the day we always have to express ourselves otherwise we’ll just be holding ourselves back, and that shit’s not healthy for the mental states that we have.

I was like, “This works for me” because I suck at a lot of things but I’m at least good at this, you know? This is what I do and I am good at it and it is personal—it’s really good for me, it’s really fucking amazing, man.

Sam Karugu: It gave me an avenue to express myself. I don’t express myself in real life but when I play metal or heavy music, I take what I feel inside and just release it.

What sort of stuff are you talking about in the lyrics, Martin?

Martin Khanja: The topics I talk about are what I go through in real life. Most of them are about, like, existing in life—you find love, you find hate, you find being broke and being rich, all that. I talk about all these things that we go through as human beings: falling in love, having your heart broken, traveling, doing drugs, being broke.

This song “Lionsblood,” we made a video for it, it comes from this understanding from my ethnic background, the Maasai. For you to become a man, you have to go in the bush and kill a lion and then you have to wash yourself in the lion’s blood. That means that you’ve found yourself. I used that, I use all this culture that we come from, the sounds we have on the release—it’s about how we exist in everyday life. We can find so much content just on the street, and it’s just all about that, just being yourself.

Our differences are not our main problem, our main problems are our views and perceptions of them. Your difference and my difference are the strength that we share together. When we combine them, we are all strong. We can have all these ways of expressing ourselves—people can go to church, people can go to school, people can invent stuff, people can run businesses. And that’s it: if you’re really good at something that you really love, go with it and inspire people to do what they love. That’s good for all of us as human beings.

Even in this song called “Corners in Nihil,” it’s about when you’re in these dark places in your life and then the light shows up and you have a better understanding of the darkness. That’s how I see it. This is not a fake—we’re alive, all of us are alive, let’s celebrate it. But the only way we can do that is by having this truth in ourselves and sharing it with each other. And then we’ll see the truth in all of us at the end.

I wanted to ask about the video, actually. You guys have this red drink which looks like Gatorade or something.

Sam Karugu & Martin Khanja: (laughing).

What was it like shooting the video?

Sam Karugu: The video is just a bunch of guys coming to a party and drinking the lion’s blood because, for the Maasai in Kenya, when they go through the initiation they drink lion’s blood. But also, as a joke, people in Kenya call alcohol—

Martin Khanja: Tears of the lion.

Sam Karugu: Yeah, tears of the lion. So the idea was that guys would come to the party and drink the tears of the lion and think they’re drinking just normal booze and then, because they can’t handle becoming a man—

Martin Khanja: Yeah, it will, like, purify yourself and show you if you’re real or not. If you can survive then you belong. In the video you see the swimming pool, but it’s not just a swimming pool—it symbolizes the depth of our roots. And it’s not just the Maasai, it’s all human beings. If you survive you have the lion’s blood in you.

I also really like the cover art for the album. Can you talk about how that happened?

Martin Khanja: Our booking agent, Lola, can tell you.

Lola: Hi!

Sorry, who is this?

Lola: Hi, I’m Lola. I’m working as the booking agent for Nyege Nyege.

I love the album art, it’s one of my favorites of the year!

Lola: Me too! I love that picture. I can’t believe I took it!

Can you talk to me about it? Where was it. Did you know the person?

Lola: Yeah it was here in Kampala, in Bunga. It was the closest market near where we live and I happened to hear someone buying some meat. Actually, a friend of ours saw her the other day in the same market and recognized the fabric and it was like, “Oh, that’s her!” And that’s… it. (laughter).

It’s a great photo, thanks so much.

Sam Karugu: And for us we love it because the sound that we have is African, it’s metal, it’s all guts on the table. That’s how we say it: it’s all guts on the table. There’s meat there and every time we play it’s there, it’s inside you. It’s meat, it’s all guts on the fucking table (laughter).

Martin Khanja: People in this culture call it the Akashic records where we all share this subconscious mind that’s bigger than the human mind. Everyone can tap into it and brings things into the physical from it, from inside. For the album artwork, it symbolized that. You can take the meat and make burgers and roast meat—nyama choma—and wings and all that, but for real, it symbolizes the inner man expressing the outside, trying to engineer from our thoughts and feelings and desires and then making them a physical reality in our lives. It’s about going inside and bringing it out—putting our guts on the table. There’s no hiding. That’s the thing: you come to Duma you come to the fucking butchery (laughter).

I love it.

Sam Karugu: The cover is also dark as fuck. (laughter). The woman’s buying meat and the clothes look like the meat. She’s gonna eat the meat but it’s like she’s gonna eat herself.

Martin Khanja: There’s no hiding, man!

I love this idea about putting your guts on the table. With this music you’re really giving it your all, it means a lot to you guys. Do you feel like you making this music has helped you express yourself more in real life, outside of music?

Sam Karugu: Yeah, yeah, of course. In Kenya you just go to work, you come back, and you have to stand your ground and do your thing.

Martin Khanja: Can you imagine all these ideas that are unknown, that are not born yet—they’re just stuck in your mind and your spirit and you want them to come out and share them with the world, but the environment you live in does not encourage you to be yourself. The only way we can survive is if people express themselves in a positive way. Holding all these things inside, you will run mad. When you share these ideas, other people see them and you learn even more. It’s like waking up all these people and creating lives that weren’t existing, it’s making a good world for the future.

Sam Karugu: And that’s not just with this record, it’s metal in general and making music and doing something. You have to go all out and do what you want to do. I think the world is ending with corona and—I don’t even know what’s going on anymore—you just have to do what you want to do, just be yourself and express. With life, it’s good to express what you want to say, and I think for most people in the world that we live in now, it’s become—even now with social media—you can express yourself. It’s high time man. You have to put all your guts on the table.

So the world’s ending—what are some goals that you two really have right now that you want to make sure you really do?

Sam Karugu: I wanna at least go back on tour and spread our music all over the world. I just wanna make more music and become a better person. I wanna finish all that I have to do, become a better producer, become a better musician.

Martin Khanja: I need to be the best version of myself so that I can leave a trail of inspiration for anyone who finds this shit. I want it to inspire them to be better than they already are. You can always be better. We do the shows, we shoot the videos, but we’re putting subliminal messages in every song and the ones who are really awake can see them—we want to inspire them to be the truest version of themselves so we can all benefit as mankind. We just have to be the best version of ourselves. That’s it, that’s it, that’s it. At the end of the day, it’s like what the fuck are we doing? We just have to do our best in every moment that we can.

In the next year, I want to inspire a lot of people. When people come to see us on our shows, when they hear our music, when they see our interviews, when they watch our videos, I want to leave something in their hearts that will make them better at the end of the fucking day. Just make them better, better, better, better—no matter where they are.

You said there are subliminal messages, which I’m assuming are about being your best self. Can you tell me one song on the album where you have a specific message that you really hope gets out there to people?

Martin Khanja: This song called “Angels and Abysses,” yeah?

Yeah.

Martin Khanja: There’s that still small voice in your mind that tells you, “Bro, you fucked up, you need to go home.” The song is about that whisper in your spirit that will lead you to the truth. Realize that every day, there’s another form of you with you.

I have a master’s in psychology and I realized that our conscious mind is just the tip of the iceberg. Our habits, our behaviors, our view of the world come from a different place. If you can fine tune that, through the conscious mind, you can experience the best life that you envision you can. Even if you don’t get to your vision, at least you’ll come close to it, and that’s better than being where you are already.

Sam Karugu: My favorite song is “Pembe 666,” where it’s basically Revelations 5:6, in Swahili though. It’s this verse from the Bible and it’s John saying that he has found the lamb and the lamb is holding the seven seals and he has to open them to free the world. And then he finds that the lamb is slaughtered. And it’s just sort of funny with religion, looking for answers and you just find that the lamb is slaughtered.

Martin Khanja: There’s no answers, man.

Sam Karugu: It’s all in Swahili. I like this one.

You were talking about being an influential band, but who are the most influential bands for you in your own life?

Sam Karugu: Well, all the bands in Kenya that are still doing this shit. First of all, LYT [Last Year’s Tragedy]. Second of all, Throbbing Gristle. Genesis P-Orridge, rest in peace. And then Black Flag, Minor Threat, there’s so many bands.

Martin Khanja: I’ll start with my friend called Harvey Herr, he changed my life by believing in me. Even my family was stepping in and saying it was bullshit but he was like “Yo, bro we have a studio let’s start something.” He’s a very huge influence in my life for how he supported me in all this weird shit. We wouldn’t be here without him. The way he made me believe in myself and give a fuck about the music while everybody was telling me I couldn’t do it. He told me to just record shit and perform and to breathe life into it. That’s very special to me because most of the people I was with before were really skeptical about what I was doing. I cannot do things their way but Harvey Herr told me to do things my way.

And then there’s Kurt Cobain, XXXTentacion, Travis Scott, Mitch Lucker from Suicide Silence, Bob Marley, and DJ Scotch Egg—he’s a god. These are the higher humans on the planet, the elite.

Sam Karugu: If we’re gonna talk about the people who inspired us, I have to say Arlen [Dilsizian] and Derek [Debru] and what they’re doing here with Nyege Nyege, it’s good. And Lola here, and everyone. DJ Scotch Egg, Gabber Modus Operandi, all these people I met this year. I can’t even name names, it could be a whole book. It’s like everyone who’s been with me, including my music teacher from fucking primary school.

Martin Khanja: And my mom! Don’t forget my mom.

Sam Karugu: My mother!

Are you close with your moms?

Sam Karugu: Yes, but she doesn’t even know what I’m doing now. She thinks I’m doing music videos, she doesn’t know I’m doing music.

Martin Khanja: My mom thinks I’m doing gospel music because she has a church, bro. (laughter).

Sam Karugu: Yeah, you know in Kenya it’s very haram when they find out you’re doing [starts doing screaming vocals]. (laughter).

Martin Khanja: I’m not supposed to work in an office from 9 to 5. I can do that, I did it before, I was running a whole company and all that shit. My mom said I had to do ministry and evangelism. I’m still doing it, in this weird way, and that’s real shit. It’s inspiring, and all these people in this close circle keep telling us to keep sharing it with the world.

Do you see your band as doing evangelism then?

Martin Khanja: I see my band as ministry, we minister to people when we give them positive energy. When you come to our shows, you find a better way to overcome your fucking problems and the obstacles you have. It changes your perspective, it’s there to build you up and give you strength. And that’s fucking evangelism, man. We’re not trying to convert them, we just wanna make them remember.

Sam Karugu: Yeah, like Khanja said, it’s not evangelism. In metal, it’s not like 80,000 people are walking into a show and worshipping Iron Maiden or something (laughter). People are there to listen to Iron Maiden and they’re gonna go home and do their own shit. No one’s worshipping. And that’s the best thing about metal. It’s just you that’s there and you’re doing what you like. No one worships a band, it’s sad if you do, actually. Don’t worship Duma. Don’t do it man. (laughter).

Photo by Kachna Baraniewicz

How do you guys make songs, what does that look like? Like do you start with the production, Sam, and then Martin adds vocals over it?

Sam Karugu: We used to play in bands. Let’s say there are five guys. Normally, one guy gets an idea, and then the guitarist comes up with a riff and then the drummer comes up with something. But now it’s just the two of us—we have a laptop, and we have a guitar, and we have vocals. So I come with an idea and then we work on it, or Khanja has one.

The funny thing is that in metal, most people don’t respect a computer. They think it’s not pure. But I realized that with a computer, we can have a whole band with it. We come up with a synthline or drums or guitar and then we distill it until we finish it.

Martin Khanja: We develop the music from our daily lives, we put ourselves in different situations where there’s a lot of psychological and existential bullshit. We put them in songs because everyone in the world is going through the same fucking bullshit. We have concepts first.

For example, we have a concept we made for a song on the second album called “Sentience.” It’s about rats. Let’s say you have this mansion and it’s nice but there’s these fucking rats and they’re evolving and running around the fucking mansion. That’s the fucking song. After the concept we come up with a soundtrack—we find the best moods for the concept. And then the concept and the mood comes into play and we take all these influences from the songs we like and try to make the mood in this song happen.

For me, every song in Duma is like a score for a movie. Every fucking song, we went through it. Even this song called “Uganda with Sam,” it came from when we were walking and had just played a show, and Sam was puking on the road. I’m taking Sam home and say, “Fuck! I’m in Uganda with Sam!” That’s the song! (laughs).

Sam Karugu: We just get influences, we just live life and experience stuff and express it. We go into the studio, remember how we lived it—it’s already in our heads—and that’s it. That’s basically how most metal is made. With new pop or EDM, some producers come out of nowhere with a beat, some guy comes and starts singing over it, and then they release it. For metal that makes no sense—you have to live it with the band and make the whole song together.

Martin Khanja: True, true.

You guys mentioned a second album. What’s going on with that?

Sam Karugu: We’re still working on the album. We have a collaboration with Gabber Modus Operandi, Sense Fracture, and Elvin Brandhi. And also we have an album coming out, but it’s gonna be more metal than the last one. This one was metal but a bit more out there. There’s more guitar, more noise, more breakdowns, more pig squealing.

Martin Khanja: More fucking distorted bass, man. You know, death metal has been done. Metalcore, deathcore, avant-garde, symphonic, doom. We use all these influences from all these different genres and create a hybrid form of expression. That’s what’s up. People who are born in 2040 or 2050 will need something to fuck with, and we’ve gotta move forward: evolve metal, evolve trap, evolve electronic music, evolve African music, evolve all this music to make a hybrid genre. That’s our goal: we want to make a new genre. We’re gonna make a new fucking genre, bro.

Sam Karugu: When I say guitar, in Duma we play guitar but you can’t hear it because it’s fucked up—it’s botched-up guitar with a lot of effects. So the idea is that you can’t keep releasing the same shit over and over again. As Khanja would say, three albums deep it’ll be a new genre. We can’t do Duma again for the next album. We can, but it’s gotta be Duma 2.0.

Do you have anything else you wanna talk about?

Sam Karugu: We wanted to ask you about Tone Glow.

Yeah, that’s my newsletter. I felt like a lot of publications weren’t doing things that I wanted to do, or weren’t covering things I wanted to cover, so I started my own thing.

Sam Karugu: Yeah! That’s what we did too. We started our own metal zine in Kenya, it’s called Heavy and the Beast.

Martin Khanja: Same thing with Duma. We wanted something that wasn’t already there so we put it out ourselves. The sound we wanted to be out there in the world wasn’t there. That’s what Marilyn Manson did. He wanted to make music that wasn’t already out there—he’s one of my biggest influences actually. He’s a god, man.

I feel that. Tone Glow is a thing that exists because I wanted something that wasn’t already existing.

Martin Khanja: You’re a lord man. A lordship.

Sam Karugu: Yeah that’s what we say.

Martin Khanja: We call everyone lords. We’re doing the lord’s work. It’s evangelism—it’s the lord’s work.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. Mixes will always be available for streaming and download.

All genres of heavy, dark, loud experimental music unite.

—Duma

The tracklist for Duma’s mix is as follows (with the country of the artist listed between parentheses):

Metal Preyers - Snake Sacrifice (Uganda)

Tzusing - Boiler Room Shanghai DJ Set, second song (China)

Irony Destroyed - Najisikia Kuua Tena (Kenya)

Seven Orbits (feat. TSVI) - Submechanophobia (China)

Death - Infernal Death (America)

Death - Zombie Ritual (America)

Hyph11e - Unknown Number 未知 (M.E.S.H. Remix) (China)

Knut Vandekerkhove - Fog 2 the Floor (France)

Duma - Sin Nature (Kenya)

GG Allin & Antiseen - I Hate People (America)

Dead Skin Remedy - Soul in Ink (Demo) (Kenya)

Download: FLAC | MP3

Stream: YouTube

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Joe McPhee - Graphics (Hat Hut, 1978)

Graphics is a key early album in Joe McPhee’s extensive career that showcases him at the height of his considerable skill and compositional ambition. It’s a double LP documenting two solo concerts that took place on consecutive nights in Paris during June of 1977 wherein McPhee took the opportunity to virtuosically spread himself out over 80 unaccompanied minutes on soprano and tenor saxophones, trumpet, pocket cornet, and conch shell.

From the titles he chose for each track, to the array of instruments showcased, it’s clear that McPhee conceived of Graphics as an extended, allusive act of veneration towards his heroes in jazz. Not content to simply imitate the stylistic quirks of his inspirations, McPhee uses their tools and voices to craft full and thematic narratives, as if attempting to contrast the full breadth of jazz history against itself. Note how his soprano saxophone travels from Sidney Bechet’s swinging blues to Steve Lacy’s angular modernism on “Vieux Carré/Straight,” or how he seamlessly swaps from instrument to instrument on “Legendary Heroes.” That this complex thematic background never intrudes on the music is a testament to how thoroughly inventive McPhee is on a moment-to-moment basis, equally comfortable with richly melodic material as he is with texturally exploring the limits of his horns. It also points to how well his thematic ideas incorporate themselves into the expressive and emotional core of his music.

Viewed in hindsight, we can see that Graphics is the kind of album that is only possible when an ambitious artist is given free rein by a sympathetic and supportive audience. When one thinks of avant-garde jazz solo performances, one does not normally picture the kind of rapturous and earnest applause that erupts as soon as almost every track on Graphics ends. They love it! We should all be so lucky as to find our audience as Joe McPhee did. —Samuel McLemore

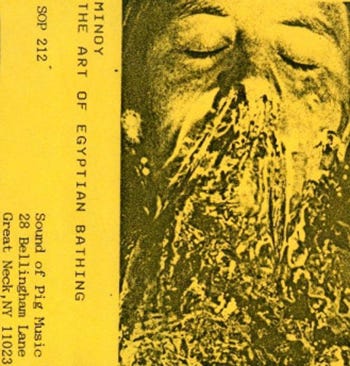

Minóy - The Art of Egyptian Bathing (Sound of Pig / Minóy Cassetteworks, 1986)

By his biographer’s account, Stanley Keith Bowsza died twice. He first went under during one of the electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) sessions that his parents put him through as a teenager in a misguided attempt to “cure” his homosexuality; upon resuscitation, he refused to resume treatment. Bowsza legally died of a heart attack in 2010 at home in Torrance, California, having left behind over 100 tapes of dense and demanding noise music; this prolific body of work was the purgative means through which he faced the consequential neuropathic pain and paranoia that loomed over his adult life. Adopting an overheard misnomer of his favorite surrealist as a pseudonym, the sound artist known as Minóy churned out labyrinthine longform compositions during manic stretches of sleep-deprived nights—these are phantasmagorical works deeply immersed in the illegible, brash as a Bosch triptych, tailor-made for darkroom playback.

Most of his discography has been uploaded to a Bandcamp facilitated by a former collaborator, sourced from the masters that his partner of over thirty years had saved. That said, I’d offer the three pieces that make up this chaotic C60 absent from the archive as a quintessential introduction to Bowsza’s versatility as an industrial improviser. The curtain rises on the side-length title track to an inescapable orgy of consumer keyboard auto-accompaniment and arpeggios, cliches in exotica superimposed to the point of seasickness; the resulting harmonic effect evokes Stravinsky’s adoration of the earth refracted to infinity. When the layers finally fade toward the end, the listener bears witness to a cilia-punishing drone. The aptly-titled “Secret Ceremony” shapes a shamanic fog out of piercing flutes, plucked idiophones and delay sweeps before tonality finally unveils its face for the shimmering closer “Timestep,” perhaps the most understated minimal synth track to come out of this generation of home-recorded hellscapes.

I hesitate to label this work as “outsider art”—being queer and neuroatypical myself, I have always found the term to dehumanize, to build barriers against potential empathy, to summon a split in the powerful bond between who creates and who consumes—as if to guarantee to the rare willing listener that one will never understand. There is often an exploitative risk in retrospective listening and reissue culture to lead with biographical trauma that can often render renewed interest in what one makes cruel; were I introducing any other artist I admire with demons in their details, I would avoid talking about their work this way. Nevertheless, there are the rare cases when an artist’s tragic history provides full context for concentration—with Bowsza’s oeuvre, the damage done is the first facet heard and held on to. —Nick Zanca

Brutal Truth - Extreme Conditions Demand Extreme Responses (Earache, 1992)

Napalm Death’s genre-defining 1987 debut Scum famously charts a lineup change for the group between its two sides. For many grindcore fans, the album’s A-side is largely forgettable, consisting largely of anarcho-punk reminiscent of a heavier Discharge or S.O.B., while the album’s B-side lays the chaotic template for what would become grindcore, a genre typically defined by left-leaning anti-capitalist politics, noisey and/or dense guitar and bass textures, alternation between dramatically different song sections, and rapid-fire blastbeats on drums. Although this template is fairly straightforward, the genre has come to accommodate a fairly broad swath of music including the dense riffing of bands like Extreme Noise Terror and Terrorizer, the tinny electronic arrangements of Agoraphobic Nosebleed and The Locust, and the irony-poisoned shock theater of Anal Cunt.

In retrospect of these many outgrowths, Brutal Truth is almost traditionalist in their adherence to the tenets of the genre, even going so far as to excavate, unify, and expand upon the disjunct elements present in early Napalm Death (namely Scum and From Enslavement to Obliteration). Across this 1992 debut, Brutal Truth visit not only grind tropes, but elements of thrash, heavy metal, while reincorporating much of the genre’s latent anarcho-punk influence. This is instantly apparent via the cover art’s use of collage and the text-border surrounding its perimeter (both visual elements heavily established by Crass). This is expounded upon sonically with the use of sampling and signal processing as well as socially conscious lyrics (the album opener “Birth of Ignorance” is explicitly anti-racist while the title of “Anti-Homophobe” speaks for itself).

All that said, if I were to direct someone unfamiliar with the genre to a good starting point, I think Extreme Conditions Demand Extreme Responses would be it. More tightly composed and performed than many of its predecessors, it illuminates the elements that make early grindcore so worthwhile while providing an interesting case for where the genre could lead. Likewise, it’s production (handled by Colin Richardson who already had albums by Napalm Death, Carcass, Mayhem, Bolt Thrower and dozen others under his belt) holds up fairly well today, crystal clear with a necessary thickness and cohesion between instruments.

A-side tracks “Ill-Neglect” and “Regression Progression” are early inklings of the band at their most unleashed, but much like that Napalm Death debut, this album eases into the height of its grind at the midway point. Following “Time”—which is likely the most musically progressive tracks I’ve heard on a grindcore album, clocking in at 5:58 and including riff development and a conceptually inspired fade-out—, is a blazing sequence of tracks beginning with the stunning “Walking Corpse” and ending five songs later with “Anti-Homophobe.” While textures would become denser, atmospheres darker, riffs more complex, and sonic explorations more thorough on 1994’s Need To Control,this release from two years prior is an exciting exercise in style and form, brilliant in its successes and idiosyncratic for its musical missteps.

Brutal Truth was born out of bassist Danny Lilker’s instinct to follow his experimental ear beyond work with influential and wildly successful thrash and crossover thrash bands Anthrax, Nuclear Assault, and Stormtroopers of Death. The latter is perhaps best known for their debut album Speak English or Die (1985), a work imperative to the development of crossover thrash which sardonically yet vapidly evokes racist, misogynistic, and xenophobic tropes for shock value. This is in stark contrast to outspoken lyrics found on Extreme Conditions…. For instance, one could compare S.O.D.’s toxic “Kill Yourself” to Brutal Truth’s life affirming and existentialist “Walking Corpse,” which asks instead:

“Are you satisfied with the way that you exist?

Every single day just like the one before.

Don’t you feel the need to express the way you feel?

Wake your sleeping brain, there's so much more.”

The stances taken on Extreme Conditions Demand Extreme Responses are not nothing, especially considering the anti-political or outright toxic nature of the thrash scene Lilker came from. That said, it’s worth noting that Lilker never fully left behind his association with S.O.B. and their past work, a point I bring up not to indict him, but to show the depth of uninterrogated dissonance between shock culture in metal scenes and the professed intentions and beliefs of those involved. Much of metal in the U.S. has operated upon a fairly conservative model ever since its inconceivably massive successes with thrash. Because it largely lacks a foundation in a DIY ethos and a sense of community accountability, there seems to be a free market faith that fan-interest will determine metal’s victors. This allows Lilker to have continued reunion tours with Stormtroopers of Death (whose shock-rock approach has been a reputable part of their legacy) while more outspoken and experimental works like those of Brutal Truth sit almost silently as half-explored artifacts without expectation for these works to represent a larger political praxis. —Leah B. Levinson

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Still House Plants - Fast Edit (Blank Forms / Bison, 2020)

Press Release info: Fast Edit is the second LP by Still House Plants, a Glasgow and South London-based three-piece collective made up of Finlay Clark, David Kennedy, and Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach.

As artists who started to write music together during their 2nd year at The Glasgow School of Art, Still House Plants emerged from the eclectic scene surrounding Glasgow’s Green Door Studio and soon found a home at London’s Cafe OTO, where they undertook a six-month residency in 2018.

Factor in a semester spent living with an emo band in Chicago and the intimate aggregation of the trio’s sound heterodoxy—an astonishing cohabitation of fractured R&B, wistful sensitivity, and harmolodic guitar—begins to show its strands. With punk autonomy, Still House Plants navigate a similarly divergent approach to ostensibly kindred artists Linda & Sonny Sharrock or James “Blood” Ulmer, but instead cite the cut-up affect of UK garage as the impetus for their sparse treatment of chords and words as samples; stuttered, fragmented, and permuted by living drums, guitar, and Hickie-Kallenach’s unmistakable husky voice.

Written aided by mobile phones, dictaphones, laptop recordings of rehearsals, conversations, and live shows, Fast Edit is a collage of different fidelities and aural spaces, a palimpsest most tenderly exhibited on album centerpiece “Shy Song”. Things sit on top of each other, fall over one another, or click into place, with hearts on sleeves and spirits in motion.

Purchase Fast Edit at Bandcamp via Blank Forms (US) or Bison (UK).

Jesse Locke: Still House Plants make lean-forward music of the most captivating degree. Like any group playing with knotty time signatures, jerky tempo shifts, and broken rhythms, it’s impossible to tune in to their songs passively. There’s something simultaneously detached and tightly connected in the way the three members’ parts interlock, criss-crossing over each to make strange new structures, familiar but just off enough to feel like you’ve stepped inside your house and found the furniture rearranged.

Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach has a voice that immediately hits your ears in an unexpected fashion like Dean Blunt or Mica Levi, colliding with the brambly guitars and clattering drums in a way that recalls Kevin Shea and Mary Halvorson’s People. Yet while that duo maintained a playfully present spirit of zaniness, Still House Plants sound distant, melancholy, staring into space. They coalesce in emotionally resonant moments like the gentle “Shy Song” or the pleading refrains of “Do,” where Hickie-Kallenbach repeats the phrases “my love” and “I do.” Fast Edit’s overall feeling of heatstroke daze is compacted with the album’s patchwork of recording sources, sewing together various fidelities and cut-up experiments like they’re learning tricks from Swell Maps. It’s a fascinating experience to spend time with this trio, listening intently while remaining completely unsure if you’ve figured them out.

[8]

Nick Zanca: “If our life lacks brimstone, i.e. a constant magic, it is because we choose to observe our acts and lose ourselves in considerations of their imagined forms instead of being impelled by their force.” Artaud unveiled this delirious truth—the first of many—one page into the preface of a text I treasure and I have often contemplated it through the act of listening since I first read it. I have long felt that our problem areas emerge from a schism between how we process our thoughts and how our lives truly are; that sound is most sorcerous when it rides this cathartic divide. No wonder that when this rift reaches our ears, we struggle to give said force a name. These are the ties that bind the trios I revere together: until about the fourth or fifth listen, Albert Ayler’s most lionized love cry renders Sunny Murray and Gary Peacock’s subtle responses indistinguishable; in just under two hours, This Heat stirred chaos and collage into a discographical inner scream of varying fidelities; the floodgates opened the moment Talk Talk invited space and subtlety into the room. Should this unnamable realm of transcendental style constitute a corpus or canon, I would then nominate Still House Plants and Fast Edit as its newest entry.

To call the work of these art students from Glasgow a “deconstruction” would be somewhat of a slight—a listener must strip all preconceptions of how voice, guitar and drums conventionally combine in pursuit of a sparse strategy. The careful collision central to the Still House Plants sound appears first in David Kennedy’s primordial percussion: rhythmic settings where the hypothetical gives way to hypnosis. Finlay Clark’s calculated chordal gestures waver between flux and fixity like a seasoned butoh dancer, assimilating the foundations of six-string improvisation bereft of the intervention of influence. Enter Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach just shy of center stage—her vicious vocal performance provides a sense of urgency and a confidence uncommon to this palette, possessing the kind of precision and control otherwise occupied in spiritual spaces. Much of the joy that emerges from listening to these three do their dirt begins with an inability in making out who is doing the driving; more often than not, the cryptic texts end up taking the wheel, drifting through hazy regions of hedonism, affection and emotional reserve. It’s been a long time—a decade at least—since group energy has reached this level of gravitational pull from performance alone; once the curveballs of layered voice memos, rehearsal recordings and background banter are thrown, we end up with a product that practically bounces off the walls of the stereo field for its entire runtime.

That this record arrives in our world in a period of extended isolation serves as a warm reminder of the pure palpable power of collective creativity; it evokes a true longing to return to a version of the world where we can all comfortably thrive in each other. Until then, we have our headphones and we have the chance to let that love linger in our ears. How lucky we are to hear this coterie collide.

[10]

Samuel McLemore: What Still House Plants remind me of most is classic jazz. Not in the sense that their music has much in common with the genre from a stylistic point of view, but in the sense that the clear expression of each player’s personality—through their unique sonic identity—is key to what makes them work so well. Though it would be laughable to claim that “personal expression” is a unique aspect of anyone’s music, rare is the band today that strives for this kind of melding of personalities, much less letting that become the guiding force behind their musical identity. The ‘average’ band consists of either a single leader giving voice to an unspoken collective or a competing collection of egos striving to express themselves on top of each other.

In Still House Plants, however, we have a pleasing equilibrium: they sound exactly like three distinct personalities speaking together. Another way to describe this is that there is never any doubt as to which element in the final mix is coming from which member of the band. Part of this is due to the disarming simplicity of their music: though there are occasional peccadilloes of found sound or production malarkey, 99% of the album is just a voice, drums, and a guitar. This reliance on a simple musical vocabulary and minimalist song structures forces us to focus more intensely on the subtleties of their approach. Still House Plants let their music stay out of the way in order for us to see them more clearly.

[7]

Mark Cutler: I know that Samuel McLemore, at least, and probably others have observed that this is far closer to jazz than it is to rock, or even to free-rock acts like Jandek or Fushitsusha. Actually, the first comparison that came to mind was Amirtha Kidambi’s work both with Mary Halvorson and with her own Elder Ones ensemble. This is no doubt partly because vocalist Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach, like Kidambi, plays her own vocal chords like a trumpet, but I think it goes deeper. Structurally, rock music tends to cleave lopsidedly into vocals-vs.-instrumentals, so that one member of the band commands the same focus as (or more focus than) their two or three bandmates combined. Here, there is a total balance between elements, so that every player, in almost every song, takes a turn being the ‘voice’ of the group. Fast Edit in this sense represents a refinement even from their previous album Long Play, which, while also great, featured more solo tracks, as well as detours on piano and violin. This time, the group narrow their scope to three elements and the possible combinations thereof. And boy do they find some good ones.

[9]

Jack Davidson: Still House Plants are one of those once-in-a-lifetime bands that remind you why music is such an amazing and fulfilling pastime. There are very few records that have grabbed me so forcefully as Long Play, the UK trio’s quite appropriately titled debut full-length, which was released by Bison in 2018. The combination of drummer David Kennedy’s fluid yet always slightly structured cascades, guitarist Finlay Clark’s artful angularity, and vocalist Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach’s impossibly full voice is nothing short of entrancing throughout all of their work... but I don’t think they have ever sounded better than they do on Fast Edit.

Rather than presenting a sprawling collage of sorts, as Long Play did with its hodgepodge of studio and live tracks with differing instrumental setups, Fast Edit almost exclusively hones in on the possibilities of the voice/guitar/drum set formula, with experiments in audio fidelity changes providing some wonderful diversity. Kennedy and Clark’s uncanny ability to avoid any consistency in tempo or meter, while somehow still weaving together enough of a “song” with which people can sway along, is more impressive than any display of conventional musical technicality I’ve witnessed, and this unusual interplay is on full display throughout Fast Edit as the band gravitates toward material more influenced by genres like slowcore and primitive post-rock. I would already count both “Shy Song” and “Curb” among the greatest songs I’ve ever heard; the former swells from an intimate, lo-fi room recording into an off-kilter, Codeine-esque crystalline plod, while “Curb” showcases some of Hickie-Kallenbach’s best vocal work, contributing both an affecting, melodic hook with “what is this and what are you to me?” as well as instrumental clout of its own near the end, when the guitar and drums are reduced to sporadic hits amidst a pregnant silence that renders her words with even more emotional weight.

Fast Edit is a much more focused and consistent outing than its predecessor, but it only gains from this newly constricted lens, softly hooking its memorable repetitions and refrains into your brain until they are stuck there permanently, causing you to desire nothing except more, more, more of the sublime sounds of Still House Plants. I’ve been in such a state for nearly a year now, and I wouldn’t trade it for the world.

[9]

Sam Goldner: Before I say anything else about Fast Edit, I feel like I need to clarify that emo has never done much for me. Even in my adolescence, neither the popular nor independent sides of the genre ever spoke to me the way it did for so many of my peers, and I’ve really only returned to it for the occasional karaoke ammo. I’ve appreciated the genre’s recent revival in terms of its historical subversiveness, but on a personal level I have zero of the nostalgia that most of my generation does about this music (frankly, I’ve always found it annoying).

This feels important to point out because Still House Plants absolutely feels like a deconstruction of the genre, something which not everybody in the Tone Glow cabal agrees on, but which definitely comes through to my ears. When I think of emo, I think of bedroom boredom, I think of cheap amps magnifying even cheaper guitars, and I think of young people wailing at the top of their lungs about the painful normalness of everything. All of these are present in the music of Still House Plants, albeit at a slant, shot through decades of atonal punk music from The Red Krayola to Harry Pussy. It’s here where my lack of investment in emo will likely shine through, because without that affection for the style (as well as its cousins such as slowcore), Still House Plants don’t seem to me like they’re pushing any of these styles forward in a way that wasn’t already covered in the ’90s.

The trio does have chemistry, and I appreciate the way Fast Edit teaches the listener its logic; off-kilter drums spiral endlessly, raw guitars start and stop on the same chords over and over again, as if trying to shake themselves loose of some doomed mundanity. Unfortunately, it all just gets too repetitive for me. I wish Still House Plants used their loose, free-associative sense of rhythm to go more places, rather than continually hanging in the same herky-jerky zone for the entire album. It’s not quite soft or aggressive, just agitated—a feeling which, unfortunately, is contagious.

[5]

Sunik Kim: Everything in me wanted to love this album. I was rooting for it from the start—the press copy’s promise of a fractured, free jazz and emo-influenced R&B with the cut and sample approach of UK garage (?!) sounded like so much of what is great about music. But the end result is, against all my wishes, underwhelming. This is doubly disappointing because in the few moments where Fast Edit actually comes close to what it promises on paper, I hear how good this band could be: Hickie-Kallenach’s voice is a force; the open, shimmering cymbal and hi-hat production is a delight. But something critical is missing. Fast Edit only formally merges all these disparate musical strands, leaving behind the respective cores, essences, of why those strands work the way they do individually. The result is an empty shell—a beautifully constructed one, admittedly—that, in its perfectly thought-out concept, feels cold rather than authentic, a forced intimacy (via the roomy production, brief interludes, field recordings...) rather than a genuine one.

The best emo offers two critical things to hold onto: energy, through tempo, the tightness of the band, screaming vocals; and melody, through solid pop songwriting and instantly recognizable and distinctive chords that are built for direct emotional impact. Also, it’s corny as hell and the vocals are often terrible, but that’s actually part of the charm, part of why this music is worth listening to. Fast Edit is, without trying to make this a personal jab, ‘art school emo’; it’s emo made palatable by divorcing it from its silliest aspects, only selecting things more acceptable to a... certain audience. In ditching the typical straightforward propulsion of an emo band, instead choosing to fragment its rhythms, Still House Plants fully throws the energy aspect out the window. This is disappointing because it didn’t have to: bands like The Raincoats and U.S. Maple prove that energy can still thrive in fragmentation rather than cohesion. But Still House Plants opt for a mostly rigid, math-rock approach to its fragmentation, looping short guitar phrases ad infinitum (at its worst, like on “Do,” this literally sounds like an ambulance siren), except, critically, minus math rock’s caffeinated tempo and tension. The end result is slow, soupy, neither here nor there, dissatisfying.

The same critique could be applied regarding the free jazz influence; the rhythms here are, at their most chaotic, simply ‘off-kilter’—I don’t get the sense that Still House Plants are aiming for an Olatunji Concert-esque freakout. That’s fine; but, again, what’s missing on Fast Edit is a kind of vitality or energy, a sense of movement and compulsion, an inner logic, that you can hear in the best free jazz, that makes free jazz so much more than people in a room together playing notes 'at random.’

If energy isn’t what they’re going for, so be it; but that has to be counterbalanced by something—and in this corner, I would expect that to be melody, some kind of pop sensibility, a direct appeal to the emotions. But, once again, the ‘jazz’ influence steps in, turning what could be such moving chords into more emotionally distant, abstract ones, endless ‘harmonic’ riffs that preclude a real emotional engagement with the music.

Finally, the UK garage influence manifests, mainly (and maybe not intentionally) in the vocals; they meander, wander, explore different registers. I hear this vocal approach on a lot of classic UK garage tracks as well—but the key difference is that UK garage vocals are backed by a propulsive, weighty, sugary rhythm section, one that drives the music forward. On Fast Edit, meandering vocals over meandering guitars over meandering drums just results in a disjointed mess, with very little to hold onto, physically or emotionally. Fast Edit seems to operate on the popular assumption that ‘looseness,’ messiness, is by default more ‘authentic,’ open and intimate; but, on the contrary, its calculated looseness feels somewhat inauthentic and inaccessible rather than the opposite. The first two minutes of “September” are where I hear the true promise of Still House Plants; the simple, open, looping, decaying chords, fragmented drums and almost-hooky vocals instantly strike to my core—this is something special. But then the song devolves into spidery tedium for five more minutes, a static, distant middle ground that goes nowhere at all.

[4]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Fast Edit is a window into my older self, into a time when opinions about underground music started to crystallize. In these serrated guitar riffs is my disdain for math rock’s sterility (it was always too perfect to be exciting), in these stop-then-hobble drum beats is a reminder of my love for free-improv rock (it was always the ramshackle imperfection that struck me), in the unconcerned howl of these vocals and lurching tempos are my prickly relationship with slowcore (it always reminded me of my own imperfections so perfectly).

In this amalgamation, Still House Plants find a midpoint that allows their music to go beyond what any of these styles of music typically offer. There’s a sensitivity to Finlay Clark’s austere guitar playing—it’s rigid, but there’s a sense they’re deeply focusing, as if trying to unearth some truth through repetition instead of showing off their chops or simply entrancing the listener. There’s a palpable calculation to David Kennedy’s drumming that makes the sloppiness feel like a point of pride—it’s like he’s concentrating hard to encourage himself, to embrace all his idiosyncrasies. I feel elated when hearing Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach’s vocals—her singing is more empowering than just straight-ahead catharsis, every coo and wail an opportunity to use her voice as a tool for loving herself for what she can do.

Fast Edit is a window into my future self, into a time when opinions about who I am start to crystallize. I hear a joy in both self and in community here, in restraint and looseness. There’s no other album this year that’s made me so grateful (it always reminds me of who I was and who I can be—and in a way, who I am is imperfectly perfect).

[10]

Shy Thompson: As a teen with not a lot of confidence and a lot to feel sad about, I had a voracious appetite for music that could help me wallow. I had a lot of go-to albums when I wanted to get lost in a miasma of self-pitying: The Delgados’s Hate, Elliott Smith’s Either/Or, and The Mountain Goats’s Get Lonely were top picks, among a few others. These albums all got the job done to varying degrees, but they posed a problem—they’re all too florid. Abstracting the language of sadness by wrapping it up in beautiful prose made for an emotional experience, but not much of an introspective one; these albums didn’t get me any closer to understanding my feelings, and only perpetuated the cycle of self-abuse. I don’t listen to any of them much anymore. They’re a little too dangerous for me, now that I no longer believe in hurting myself as a way to pass the time.

Things changed once I got acquainted with the slowcore genre. For many, the defining feature of slowcore is that it’s generally sad and that it’s slow. It’s probably great languishing music for some, but for me it was my first taste of therapy. What appeals to me most about slowcore is that it strips away the window dressing and makes everything simple; the tempo shuffles along like someone that doesn’t pick up their feet when they walk, and the lyrical content lacks the abstruse turns of phrase that discouraged me from confronting my sadness in a healthy way. When Codeine cuts into “New Year’s”—a song that was the backdrop to more emotional bloodletting sessions than I could ever hope to remember—with the line “bad to feel the way I am,” I knew exactly what that meant. When Bedhead opened Beheaded’s eponymous title track by saying “I don't know if it’s worth it,” I realized what I wanted out of emotional music: honesty, above all else.

It’s obvious that slowcore is a touchstone for the sound of Still House Plants, but they also bring the same frankness that helped me understand how to work through my teenage angst. Jessica Hickie-Kallenbach’s sentence fragment daggers and near-hoarse bleating delivery feel like the honest truth given aural form. The peculiar, jagged, simple accompaniment doesn’t seem to concern itself with being beautiful, yet it manages to wring out precious drops of beauty through raw vulnerability; I feel their hearts are exposed, and I’m comfortable leaving my own wide open. Though Fast Edit is full of songs that err on the side of hope more than agony and love more than despair, it reaffirms for me the same thing as the depressive slowcore of my teens: don’t lie to me, and I won’t lie to myself.

[9]

Average: [7.89]

Duma - Duma (Nyege Nyege Tapes, 2020)

Press Release info: Martin Khanja (aka Lord Spike Heart) and Sam Karugu emerge from Nairobi's flourishing underground metal scene as former members of the bands Lust of a Dying Breed and Seeds of Datura. Together in 2019 they formed Duma (Darkness in Kikuyu) with Sam abandoning bass for production and guitars and Lord Spike Heart providing extreme vocals to the project.

Recorded at Nyege Nyege Studios in Kampala over three months in mid 2019 their self-titled debut album fuses the frenetic euphoria, unrelenting physicality and rebellious attitude of hardcore punk and trash metal with bone-crunching breakcore and raw, nihilist industrial noise through a claustrophobic vortex of visceral screams.

The savant mix of brutally adrenalized drums, caustic industrial trap, shredding grindcore inspired guitars and abrupt speed changes create a darkly atmospheric menace and is lethal on tracks like the opener “Angels and Abysses”, “Omni” or “Uganda with Sam”.

The gruelling slow techno dirges and monolithic vocals on “Pembe 666” or “Sin Nature” add a pinch of dramatic inevitability bringing a new sense of theatricality and terrifying fate awaiting into the record's progression.

A sinister sonic aggression of feral intensity with disregard for styles, Duma promises to impact the burgeoning African metal scene moving it into totally new, boundary-challenging experimental territories.

You can purchase Duma at Bandcamp.

Jesse Dorris: So, ok: the testeria of screamo is, to me, kind of boring, maybe because vocal chords at 11 sort of have nowhere else to go. Duma vocalist Martin Khanja’s fraying wails are the worst part of their outrageously good debut album, but who cares when elsewhere he’s Diamanda Galas at a L.I.E.S. rave, giggling like Alison Moyet, his timbre steeling into cymbals like Yamantaka Eye. Thrill to the mix on “Pembe 666,” where spoken vocals rest on a pulsating bit of programming moving front and back, with washes settling in the far left and right, the sound of someone bullshitting with intention while jackhammering a wave. You can pick apart the sonic influences, as bare as the flesh hanging on the cover yet as perfectly fabricated as its apparel neighbor. With a point of view this confidently expressed, it’s a fun party game to say, “Fuck, a flute solo… like Goblin?” “Did he really just mutter ‘Funny, funny stuff?’” It’s fun like the party in their “Lionsblood” video, a prelude to polysensory destruction. Let them make Black Is King II.

[8]

Raphael Helfand: The East African metal scene is small and male-dominated, but it feels much less regressive than its American counterpart often can. Nairobi’s Duma is a case study in the sinister sounds coming from Kenya and Uganda right now. Theirs is a bizarre fusion of styles, from grindcore to thrash to glitchy electronica. This profane blend, concocted by the fast-developing production mind of Sam Kurugu, recalls the spasmodic sonic world of Fire-Toolz and, to a lesser extent, the cinematic intensity of Oneohtrix Point Never. On “Omni,” a crescendo of pummeling percussion gives way to a smooth trap beat that transports you from a sweaty, swarming pit to a glimmering dance floor. On lead single “Lionsblood,” the opposite takes place—a ravy uptempo drum machine peppered with acoustic hand drumming distorts into staticky pandemonium as vocalist Martin “Lord Spike Heart” Khanja’s wounded roars echo around the propulsive melee, merging into a miasma of smoke and sulfur. Khanja’s voice is a revelation of its own. His style reminds me of New Orleans doom metal heir apparent Brian Funke’s, a whisper-screamed growl bubbling from a rotted-out stump of a diaphragm. Together, Kurugu and Khanja breathe life into a genre that has long been sick with chauvinism and white supremacy, showing us that metal can still feel urgent and uplifting in 2020.

[8]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I like when sounds amass into a wall I feel trapped inside, like I’m being devoured by the music. That happens here, occasionally, like on the pummeling assault of “Lionsblood” and the psych-industrial stomp of “Sin Nature.” These experiences are balanced out by those where I’m refused a moment of complacency: the electronic trap breakdown of “Omni” gets me dancing, while the glitching electronics of “Uganda with Sam” make me aware of my existence, my being here and listening to an album on my computer’s media player. It’s refreshing to hear a group that comfortably errs into the lo-fi and has full confidence in their sound, a group who knows that abrasion can come from multiple directions—screaming, manipulated percussion, the negative space that fills the air as electronics spiral out. Their brand of metal feels like they’re trying to combat all the noise that’s in this world, head-on. There’s no fear—they have no doubt they’ll win.

[7]

Adesh Thapliyal: A woman, clothed in wax print, transformed by the lens into a living carcass—Duma gets props for shocking in the crowded category of provocative industrial album art. But if you were hoping that Duma would develop any of the complexities alluded to in the photograph, like the Dutch wax print’s entanglement in colonialism, for example, you’d be disappointed. Duma intends to be an olive branch between two thriving underground scenes in Nairobi—metal and club music—and it does its job well enough: tracks like “Omni” and “Uganda with Sam” preserve industrial textures while skillfully mixing in trap, EDM, and footwork. The boppable tunes are the highlights here, because when Duma drifts into headier waters it sinks. The album’s loose ends aren’t woven together: flourishes like the hand drums that begin “Sin Nature” and “Angels and Abysses” or the Arabic-style murki that ends “Lionsblood” point towards a radical project that it shies away from pursuing. The result is a modest achievement that could afford to dream bigger.

[5]

Jack Davidson: I hate to say this, because I really wanted to like this self-titled debut effort based on both its fantastic cover art and ambitious concept, but unfortunately Duma is an exemplary case of how not to effectively execute a fusion of metal and electronic music. The opener, “Angels and Abysses,” has barely any substance to it, sacrificing what may have been a pleasingly punishing assault of percussive mayhem in favor of a sickly, soupy smear of melted rhythms and an atmosphere thinner than a gossamer sheet. Things only get worse upon the introduction of the vocal elements, which manifest in the form of what I can only describe as a parody of the extreme metal modus operandi: the screams and growls have little, if any, emotion or power behind them, only gaining any sort of presence through heavy manipulation and the stark contrast they provide against the minimal instrumentals.

“Lionsblood” marks a transition in my perception of the album from perplexity to outright annoyance; the nearly six-minute track is an infuriatingly aimless drift of unpredictable, high-velocity EBM punches and vocal delivery that just sound lazy. Even more bewildering is its unceremonious ending, which cuts off the proceedings as suddenly and anticlimactically as if an airlock was depressurized. Unlike other works that have attempted a similar stylistic amalgam, Duma gains almost nothing from its messiness—it pales in comparison to something like the disjointed eclecticism of Black Vomit’s Jungle Death or the delirious psychedelia of Yoga’s Skinwalker, both of which heavily draw from disparity, while Duma drowns in it. While I have no doubt that the two members of the project are talented musicians, it just wasn’t in the cards this time; I honestly can’t remember when I last disliked an album this much.

[1]

Sunik Kim: Duma is Autechre’s Untilted in a parallel netherworld, its metallic, armored shell peeled back to reveal a bloody organism with the same drive for pure, breakneck rhythmic joy. “Corners in Nihil”—where Lord Spike Heart’s vocalizations are pushed to the very front of the mix—captures the strongest aspect of Duma’s pummeling appeal: rather than clouding its sound in layers of distortion and murk, it instead lays metal clichés bare, clean, highlighting why exactly this odd, hilarious combination of sounds offers a truly unique form and outlet of human expression inaccessible via other, maybe more digestible or ‘respectable,’ means. I just so happen to be getting into metal for the first time in my life, after years of dismissing it as ‘not for me’; based on my extremely brief experience so far, Duma suffers from the main pitfall of other metal greats—the formula inevitably, almost by design, wears thin and tends to exhaust itself. Duma ultimately loses steam in the same way, devolving into a homogeneous soup of mid-frequency noise washes, cavernous screams and scraping percussion. “Corners in Nihil” and “Uganda with Sam” point towards Duma’s most exciting contribution—a stripped down but propulsive synthetic metal with dry, speaker-rattling percussion, crystal-clear vocals and occasional injections of color via electronics rather than chugging guitars—but the more straightforward industrial-influenced and heavily-FX’d sections fall into an all-too-forgettable tedium.

[6]

Leah B. Levinson: The album art—depicting a robed figure standing parallel to a skinned animal carcass hanging from a meat cleaver; the figure’s robe echoing the brilliant red of the carcass’s muscle and the rich yellow of its fat in a crisp, swirling pattern—incredibly evokes animal slaughter, human corporeality, consumption, an exposé of industry, and regional specificity, all without belaboring any aspect thereof; a perfectly apt introduction for the music within, which blends diverse influences, techniques, and sounds seamlessly into one startling yet exhilarating work.

Use of electronic elements is not particularly new in grindcore, however, the result here is far from the cybergrind that has followed from Agoraphobic Nosebleed or The Locust. Duma rejects the pummeling clarity of a mechanically produced blastbeat by washing out their percussive elements with layers of feedback, billowing noise, and howls. Likewise they refuse the energizing change-on-a-dime element that animates much extreme metal and punk, instead allowing layers to dovetail with each other causing a brilliant, suspended, and disorienting sense of present. The hazy ambiance of these nine tracks aligns them more in my mind with the post-punk trance evocations of Brazil’s Rakta or the blend of house and hardcore that New York’s Limp Wrist has toyed with as of late.

Riffs take a backseat, allowing room for variegated sounds and production techniques: a rapidly ducking synth on “Omni”; a droning, synthesized string harmonic across “Lionsblood”; four-on-the-flour drums and ringing tones on “Sin Nature”; haunted synths on “The Echoes of the Beyond.” Unexpectedly, I find sounds on this record resonating with Elysia Crampton’s recent masterpiece ORCORARA 2010, namely,the low, dry, spoken word on “Pembe 666” and the oscillating polyrhythmic gusts on “Sin Nature.” Both albums sculpt a landscape slowly while subtly moving in unexpected ways. Many tracks here end with a jolting, sudden fade into silence, interrupting the glossy, smoothed-over surface of the tracks themselves, and feeling oddly reminiscent of automatic fades in capitalist platforms (the sponsored Ad on Spotify or the free sample offered on a webstore before purchasing a download).

Duma makes me infinitely excited to dive into the apparently blossoming Nairobi metal scene, a scene which must be excellent considering its capacity to support work as innovative and well-developed as this.

[9]

Average: [6.29]

Still from Kati Kati (Mbithi Masya, 2016)

Thank you for reading the twenty-fifth issue of Tone Glow. Live your life boldly—put all your guts on the table.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Nyege Nyege tapes are all killer no filler.

Thanks for the information , keep doing.