Tone Glow 022: Shirley Collins

An interview with folk legend Shirley Collins + album downloads and our writers panel on Asher Gamedze's 'Dialectic Soul' and Reizen's 'Works, 2020'

Shirley Collins

Shirley Collins is a folk singer from Sussex, UK. In the 1960s and ’70s, she and her sister Dolly—along with groups like Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span—reinvigorated British folk music by staging the ageless songs in modern and elaborate arrangements. Collins is one of folk music’s most enduring voices, and after a period of over 30 years where she did not record or sing publicly, she released the album Lodestar in 2016. Her follow up, Heart’s Ease, is out July 24th. Jonathan Williger called Collins on July 1st to discuss life during quarantine, her new album, how she’s feeling more comfortable with herself, Boris Johnson, and more. Photos by Enda Bowe unless otherwise noted.

Jonathan Williger: How are you doing?

Shirley Collins: Alright, still locked down of course—because of the virus—but I don’t know. I’m sort of fine, really, and there’s plenty going on. So it’s good, how are you?

I’m doing okay. Do you live with anyone right now?

No, I live alone, but I’ve lived alone for a great many years, so I’m sort of used to it. So I’m okay, you know?

What have you been doing to keep yourself occupied?

Well, I’ve got a garden at the back of my cottage, so I do a bit of gardening. I’m finding I’m doing lots of reading—sort of consuming books in piles, really, more than I’m listening to music, which is funny, and a bit odd. I walk up and down my little street and garden, and that’s about it.

What have you read? Do you find yourself gravitating towards novels or nonfiction?

I love Anne Tyler—I read all her books over and over. I’ve been reading the Pat Barker book, the Regeneration trilogy. And I read an English writer called Kate Atkinson. People just put books through the letterbox and I read them. And I re-read whatever I can pick up. But it’s good, I'm sort of enjoying that, because I love reading anyway. I’m busy at the moment, too.

Do you feel like you’ve been able to keep a sense of community? It seems like people are dropping by to give you books… have you been able to keep in touch with a lot of people?

There’s a good feeling in the streets because there’s lots of families with little children, and they’re playing outside most of the time. And the trouble with this lockdown thing is that you can only really see your friends. I’ve seen my musicians as well. Ian Kearey, who does all the arranging, he lives close by and he comes and visits once a week and we sit and talk about things.

Yeah, it is interesting that acquaintances have become somewhat of a thing of the past.

True! Not that it’s their fault, you know. I don’t blame anyone. You know, as people keep away, they sort of drop away as well.

Yeah, I think that’s true. What music have you been listening to? At least personally, I’ve gravitated towards certain music that I have loved for a long time. I find that certain music, at least for me, has been harder to engage with than other types, and I’m wondering if you have felt the same way.

Well, I listen to a lot of early music, which I love. I like Italian Renaissance music, the music of Monteverdi and the music of Thomas Tallis. I’ve always loved the sound of that because when it’s somber it’s wonderfully somber, and when it’s merry then it’s very happy music, very lively. I’ve been listening recently to a group, an Irish group—I don’t know if you’ve heard of them—called Lankum. They have a singer called Radie Peat who has just got the most incredible voice. She reminds me of one of the old Irish Tinker women that Alan Lomax recorded in the 1950s. She’s got that same deep, powerful voice that she just throws at you. It’s really remarkable.

Have you been able to see them live?

Yes, I have. They were on locally last year, and I wish I’d gone up to say hello to them but I didn’t. Because there were so many people there, and you always feel a bit reluctant to sort of wander up and say “Hello, I’m Shirley Collins.” (laughter).

What was the last music you saw before the lockdown happened?

Well, it was Lankum and Radie Peat.

Oh okay, it was.

That was the last one I went to, that was last November I think. You know, then the lockdown started when, a few months ago? So that was the very last concert I went to. Oh no! I went to see Richard Thompson, when he was over here of course.

How was that?

Fantastic. Absolutely wonderful. I mean, he’s a great guitarist, great songwriter, and he’s a great singer. You know, everything’s just wonderful about him. So that was a real pleasure to see him. And then, it was the Irish group. So that, I'm afraid, has been it. (laughs). Sounds pathetic, but I don’t go out much.

Is there a concert hall near you in Sussex?

There is, there’s one in Brighton. The Dome, in Brighton, is the big one. But we’re only about an hour and a half from London by train as well, so I could always get up to big concerts. But the truth is, Jonathan, I just don’t like going to big cities anymore at all. So I tend just to… if there’s something on locally I can go to. And I do go to the local folk club, which is just at the end of my street. So if there’s a singer there I particularly want to hear, I can just wander along there. But otherwise I don’t go out to big gigs. I don’t enjoy them, I don’t enjoy being in crowds.

Is it something about the intimacy of the small gig or is just the antipathy towards crowds that keeps you away?

I think it’s the antipathy towards the crowds. And also just the bother of having to get there by train, cause I don’t drive and the train system is so absolutely awful in this part of the country now that at the end of a concert you get back to the big station waiting for your train, and they’re often canceled or they’ve changed platforms and you just miss it. I just don’t want to put myself through that, so I’m very happy at home, I just am.

Folk music is a method of telling stories, and you’re such a natural storyteller. I wanted to know: What were your favorite stories to be told as a child, or to read as a young person, and how may they have influenced you and how you approach music making?

Oddly enough my sister and I weren’t read to much. We sort of had a strange childhood anyway because I was just four years old when the war broke out. My sister and I—and this is the start of my love of folk song, I think—we used to have to go to sleep in an air raid shelter which was just a sort of a big steel table that you had in your house. It had mesh sides, and you just crawled in on a mattress and went to sleep. Well, Granny and Granddad used to sing to my sister and me all the nights of bombing raids and things. I didn’t know then that the songs were folk songs, but I later learned that they were. It was the comfort, the security of them singing to us that paved the way really. It just put these songs in my head as something that were such a benefit really, and benevolent.

Reading at night—we used to prefer to do that ourselves. Dolly and me, we were avid readers as well. We read all the kids’ books and any comics that we could get hold of. We weren’t allowed to read in bed at night, so we’d take our torch with us and when mum had gone downstairs we’d just shine the torch on our books and start reading again. You know, what every kid does really, being disobedient (laughs). You couldn’t stop us reading.

Do you remember what you were reading at the time?

Oh, yes. You probably don’t know Enid Blyton or Malcolm Saville or Richmal Crompton—she wrote just brilliant books, books about this very naughty schoolboy that was so funny and still are. They’re beautifully written. Enid Blyton wrote adventure stories for kids, The Famous Five, The Secret Seven. They had schoolgirls who went to boarding school and had midnight feasts. It sounded so exciting. Then there was a particular book I loved called Shadow the Sheepdog, which is self-explanatory. We’d go down to the library every Saturday and make sure we got our books and, as I say, just read. I still do, I still love it.

Thinking about these songs that you heard as a kid, it seems like you’re still recording a lot of them. How much are those memories a part of your decision to sing songs versus the content of the songs themselves? How important is the context of the song in your life or in larger culture—who has sung it before—as you’re putting together your own repertoire?

Well, it’s all of those, really. Because I’ve been lucky enough to work for Alan Lomax and I was able to listen to—when I was in my early 20s—the field recordings that he made when he worked in the British Isles with Peter Kennedy, an English collector. I had access to all those tapes.

But I first started out looking at books because I didn’t know how to find any other songs. When I was 18 I moved to London for a bit because I wanted to go to the library at the headquarters of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. I would just pore through books and look at the words, and if I liked the words I’d copy them out, and copy the tune out as well on manuscript paper, and take them home back to Hastings for Dolly to play on the piano. If I liked the tune as well I’d learn the song.

Looking and listening to such a variety of songs, and so many ballads—which as you know go back centuries—some of them just have echoes of stories, and I find that really fascinating. I love that that echo, that part of the song, has been so important for so long that they still sang it and carried it forward. I just find it really thrilling. It also contains the history of ordinary people.

They aren’t protest songs as such, and yet within many of them you know what people were thinking about, like having your sweetheart snatched away from you to fight Napoleon. That happened so many times along the coasts of England. Men were just really literally stolen from the land, grabbed, and sent into the Navy. There’s quite a few songs about that. But the songs that go back even further you know—did you hear my last album at all? Lodestar? The first one I made for Domino 2-3 years ago?

Yeah!

That had a couple of ballads on it, one that went back to the 16th century when there was an earthquake in England, and old St. Paul’s cathedral was toppled by it.

I’m pulling out my copy right now—yeah, “Awake, Awake.”

That was written at that time, but it just vanished. It disappeared. Nobody had collected it since it was written, and yet it turns up in 1902 or something up in the northwest of England on the lips of a housewife. You think, well, how did it get there? What journey did that song take to reach that? And the other one on that album, “Cruel Lincoln”—people think it’s a really bloodthirsty song—and so it is. (laughs).

Lincoln himself is justified in his anger because he’s built a house and hasn’t been paid. And so he’s out for revenge. In a song, and in a ballad of course, it’s much more stark you know. Everything is sort of intensified and exaggerated. In a way, it has to be, because it’s contained within those few verses. I just find it so absolutely remarkable the length of time some of these songs have been circulating. It’s just thrilling, you know. And they’ve only been circulating because people wanted to sing them. And the sad thing is now, of course, that people don’t really want to sing them very much. They seem to prefer to write their own, or just listen to pop music.

What you just said struck me, that it seems like there are fewer people who want to take on some of these traditional songs as their own. Do you feel like that is because of the sort of loss of localized communities in favor of ones online? I’ve read people like Chris King saying that that is something that is contributing to the loss of folk songs.

Too global, yes. I think that’s very true, but I also think a lot of people have what I think is a false idea that they’re more creative if they write their own songs. When you hear some of the songs that they write there doesn’t seem to be a great deal of creativity needed. (laughs). Sorry, I’m not really being mean, I’m just… especially when they say “I've written a folk song.” No, you haven’t. You can’t!

These songs just contain everything I need, or want, or love. These songs are just so precious, and so beautiful, and when they’re not beautiful you don’t have to sing them. But I think, in a way, there’s a sort of vanity with people. All they feel is all “me, me, me” nowadays. “Look at what I’m doing, look at this song I’ve written.” They’ve spread it out all over Facebook and what not. And I think “Help! What’s the future with this sort of music?” Whatever it’s gonna be, it’ll be, and I can’t stop anything.

I've used this word before, but in a way it’s archaeology, this music, isn’t it? You dig up something precious from the muddy field, and you see you’ve found a Saxon coin, or something like that. A collector goes out and finds a song from some old chap working on a farm, and it’s an equal treasure to that coin, in my mind.

But one of my favorite songs on the new record is “Locked in Ice,” which is a newer song, right?

Yes, there are always exceptions, Jonathan! (laughs). There are several points about “Locked in Ice.” One is, it was written by my sister’s son, who I’m sorry to say took his own life a few years ago, and that was after Dolly had died. He had made several albums and I’d always loved this song, although he sang it as quite a hard, rocky number. But I thought the story was so fascinating and I loved the tune he’d written. I just couldn’t get the song out of my mind for ages. I tried to sing it for Lodestar but it wasn’t working, and so I just lived with it for another couple of years.

Then I had this image of this little ship just floating hither and yon in the Arctic ice, just being carried away whether she wanted to move or not. So we slowed it right down. I associate myself with that poor little ship being swept away, locked in ice, because that’s how I felt I had been for far too long as a singer. I'd just been kept away from this thing I loved most.

Although it’s a true story, I have to say that because I like things older than newer, I set it 100 years earlier: Instead of it being 1931 I made it 1831. That’s called artistic license (laughs). But I think it’s a wonderful song, just so atmospheric. For Buz to write a song like that is just lovely. I was just grateful that I finally got hold of the way to sing it and not try to make it a sort of bigger thing like Buz had. He just sort of drew it right down to the sorrow, the sadness of this little lost ship.

Do you play music alone? When you were working through this song, was that just you in your house working through it, playing it over and over again, trying to find the tenor of it, or do you work collaboratively?

Sad thing is, Jonathan, I don’t have any instruments left. I was so broke at a point in my life quite a few years ago that I had to sell everything I had. The way I sing songs is mostly in my head. I don’t sing out loud unless I have to. Mostly the stuff just… is silent really. It’s a bit odd singing to yourself. In a way, I think it’s a little bit pathetic for me to do that for some reason. I just find I embarrass myself. I don’t like the sound of my voice if I’m singing, so I have to keep it in my mind instead. I’ve got used to the way my voice is now, quite different from how it used to be. But at one point if I sang out loud indoors, it just knocked me back to the time when I just was too afraid. So I’ve never risked doing it. And it’s a great way to learn the song, just to keep it going.

In your head all the time.

In your head all the time, yeah.

Do you feel that returning to music has been an ongoing process? Do you still feel like you’re in that process right now?

Yes, I suppose so. Except, I don’t know how much more I might improve. But I don’t know, I’ve got another album in mind I want to make next if Domino will let me. I suppose it is an ongoing process, but I’m quite happy with where I am now because I’m surrounded by just the loveliest musicians, like Ian Kearey who writes all the arrangements and plays so many of the instruments. I tend not to think of myself as a subject. I’m sort of back being myself and not an ongoing problem.

You feel more yourself.

I do. I feel quite at ease with myself. I’m quite used to taking criticism. I have been all my life, because people who sing the sort of music that I do, the genuine folk songs, you get quite a bit of stick from people. “Oh, that boring old stuff. What would you want to sing that for?” So I’ve been used to the idea most of my life that I know the value of these songs and the beauty of the songs, but a lot of people don’t. Then when Lodestar came out, somebody said “oh she sounds like...” who’s the singer? “She sounds like Tom Waits.” (laughter). All you can do is laugh. You can’t let that one get to you. Then somebody else said “The bitch can’t sing.” (laughs). We all sat round the room and laughed when we heard that one. You can’t please everybody. And it seems I can’t please many people.

The Tom Waits comparison seems very lazy to me.

You’re quite right, that is lazy. Anyway, as I say, it really doesn’t bother me now. I think now: I’m right, you’re wrong. You people who don’t like it, I don’t care. You can’t try to change yourself to please people. All I want to do is honor those old singers that the songs came from, because they’re the important ones, really.

So much of your music, and folk music in general, is community music. The way you’re talking about these people that surround you now, it sounds like you’re forming a community… is that musical community returning to your regular life a part of you becoming more comfortable with yourself again? Who is your musical community now?

I find this one a bit difficult, you see, because I think they’re not doing it the right way. I think they should go back and listen to field recordings and not try to make their own songs up and pass them off as folk songs. There is a good community here, though. The folk club just at the end of my road, Elephant & Castle pub, they have singers there every week. Some local people who still sing and they have guest artists as well. Then there’s a shape-note singing group as well who do all the Sacred Harp songs. Except of course, they haven’t been able to do it of late. Everything is quieting down and everybody’s isolated. But Sussex has such a tradition of song. It had the most famous of the traditional singing families, the Copper Family, who have lived around these parts for the last 400 years or so. They sing as a family group and they sing all the old folk songs of Sussex in harmony. It’s really beautiful. So we are all influenced by that here. It influenced everything because we all want to sing those lovely rich harmonies that they sing. Sussex is a good spot because it’s still going on here. Or it was until the virus turned up.

I wanted to go back a little bit—you’ve mentioned meeting Almeda Riddle as formative. What were some surprising or powerful moments when you were in America with Alan Lomax? What did you feel when you heard traces of these songs that you knew from growing up in England, evolving as they found their way to America?

In many cases, Jonathan, they weren’t traces. They were complete ballads, but with some slight turns of meaning that I found really fascinating. The tunes were not English tunes or Irish or Scottish tunes, they were just mountain tunes. When you hear one, you know it’s from Kentucky or Virginia, or has an Arkansas Ozark sound. Same goes for the way that they’re sung, in a fairly harsh, shrill voice. I guess that’s because once upon a time the songs had to carry through the mountains if you were isolated. You’d sing out.

Meeting Almeda was a highlight, but meeting Mississippi Fred McDowell was I think the highlight. He was just so wonderful and it was just extraordinary for me as a girl from England, back in 1959, where the furthest I’d been from home was London, 60 miles away. I’d never been further from home than that. And suddenly to go to America and to end up in the South and to end up in the hills of Northern Mississippi, and to see Fred McDowell coming out of the trees and into the clearing carrying his guitar—that’s just going to be absolutely indelible all your life, that image. And then to hear him sing! I was just transported. They were so lovely, they were so friendly. And Annie Mae, his wife, we just got on so well. We were there for about five days in that region. When I think about it, it feels almost unbelievable that it could happen. But it did happen.

When I met Almeda it was the same thing, the sort of truth of her singing, the directness of it. She talked about her life, the hardships she’d endured, the loss of her husband and the loss of the book that she wrote all her ballads down in during a tornado. To hear these stories as someone who lived in peaceful little Sussex—apart from the fact there was a war when we grew up (laughs). We used to get bombed, and we got machine gunned one time. It was just so extraordinarily different, and yet there was a kinship. I really felt sort of right from the start with almost everybody. I guess it might’ve been the music.

I remember in Kentucky, one old mountain lady at one of the meetings, she was listening to me speak and she said, “So where are you from, young lady?” I said, “Well, I’m from England.” She said, “What, England over the water?” It was just so amazing to her, as well, that I’d come all that way. Of course, her own ancestors had come all that way 200 or 300 years earlier. I just loved these people, and I loved their music. There were some very terrifying moments as well of course, and they were mostly from white religious zealots. They were scary. But it’s extraordinary to feel a kinship with people that live that far away. I’m just so lucky to have had that experience, because it can’t happen again now. Nobody else is going to be able to experience that, really, because recorded music has come so far with radio and television. It’s all sort of shunted all this music aside. There must be pockets of it still where people still sing the stuff, and some youngsters come through who want to sing it as well. I really lived a privileged life over there, I must say.

Had you already recorded False True Lovers and Sweet England by the time you went over on that trip?

Yes, I had. It was all recorded by Alan [Lomax] and Peter Kennedy. I’d been living with Alan for 2 or 3 years, and then he decided to go home to the states without me. I was heartbroken, actually. I think he did these two albums as a sort of apologetic gesture, you know, to say, “Sorry Shirley. This is what I can do for you, though.” In many ways when I listen to them, I wish I hadn’t recorded them that young, because I was still singing some of the songs I’d learned at school. I was building a repertoire, but I hadn’t built anything near as good of one as I would have wanted to. But it’s a start and you have to start somewhere. There were one or two songs on it that I thought were quite sweet anyway, and one of great granny’s songs, “The Bonny Cuckoo,” is very cuckoo-like.

Are there any other folk music traditions that you would want to engage with or learn songs from that you haven’t? Or traditions from elsewhere in the world that you’d like to approach but you feel like you can’t?

The one that I do love and find really thrilling is the music of Brittany, the Briton music. The instruments they use are wonderful, like bombards, which are great trumpets that just have this wonderful shrill sound. They play bagpipes as well. I just like the sort of modes of their music, the way it sounds. It’s just got an edge to it and a distance to it that I like. It seems to take me back a long way. I listen to Alan’s recordings, his Spanish and Italian ones, and there’s some incredible music there, but I don’t go out of my way to listen to it now. I just feel right now as if I’ve drawn in a bit. I like Hungarian music and Bulgarian singing, the way they push the notes against each other. That’s really very grand music. I feel a bit ashamed of this really, but I don’t go out of my way to listen to anything new at the moment. Isn’t that awful?

I don’t think there’s any shame in that. This is sort of what I was getting at a bit earlier too, if you’re in your home by yourself it makes sense that you want to go to something that’s familiar or comfortable.

Yes. I have to be very vain here and say I do listen to Heart’s Ease quite a bit (laughs). Because I like the songs! It’s not vanity I don’t think, it’s just that I think they’re such lovely songs and I want to hear them. In a way, it reminds me who I am, you know? It reminds me that I’m still Shirley Collins and I’m still going. At my age—I’m going to be 85 in 3 days time—you stop and think, as you will find when you get near to 85, Jonathan. You don’t know what’s going to come, you don’t know what’s happening. I had lost sense of myself all those 30-odd years when I wasn’t singing, and I just like the fact that I’m really back being me now. It’s good that I’ve managed to get back to singing because that’s where my heart is, really.

Shirley Collins in the late ‘50s. Photographer unknown; from the Peter Kennedy Collection.

I was reading through the liner notes to The Sweet Primroses this morning, and one of the things that you wrote in it says, “Wherever I go in Britain, history seems to press through the train windows, and the songs I love help best to celebrate it.” I’ve been struck by a sense of real pride in British history and British traditions in your music and it all feels very beautiful, but it also seems like in contemporary times, that feeling has been twisted by politicians in upsetting ways. I wanted to see what you thought of that.

It’s dreadful. The family I grew up with in Sussex, they were all working-class people. Granddad was a gardener, my dad was a milk roundsman from the farm. They all loved England, they loved just being in the countryside. They loved some of the old songs as well. So that was sort of imbued in me right from the start, and we were out in the countryside all the time during the war, just to get away from town and the bombs. I’ve walked all my life out in the countryside, and I always despised people on trains who just sit and read and don’t look out the window. Especially if they’re going through some part of the country that’s really lovely. When I was singing in my 30s, yes, I did look out of windows all the time, and yes, I did love the countryside.

Now, I’m almost ashamed to be English. How can you believe in democracy when you’ve got Trump and we’ve got Boris Johnson, and we’re leaving Europe? It’s such dreadful, dreadful times. I just feel—not deeply ashamed, because it’s not my fault—but I just don’t know how we've arrived at this pitch. And I don’t understand how English people can just want to up and leave Europe. We’re all part of Europe. It’s such a tragedy. I don’t know, people just seem to like Boris Johnson because he’s a character. He sounds like somebody out of Dickens, but one of the fools. I’m sure I love the part of England I still live in, because the countryside here is wonderfully unspoiled—it’s all protected national parks and you can’t build on it. I don’t really like modern people very much. It’s so noisy, and they shriek and they yell. That’s possibly because I’m old, but I didn’t ever shriek or yell when I was a kid or young person. Sorry—am I boring you?

No, this is fascinating, I love this!

When I was a young woman and I was speaking to somebody, you’d say “my friend and I.” But nowadays, people put “me” first, you know. They put themselves first. And then their friend second. There doesn’t seem to be much courtesy around these days. I think there’s not enough for people to really fill their souls with now.

Modern life is not as nice as the life I grew up in, even though it was tough (laughs). In the war, my sister and I were machine gunned once in Hastings. We used to watch the planes coming up from the English Channel, and you always knew if it was a German plane ’cause it was dark gray and had a black cross under the wings. We were pushing our little cousin down the road in her pushchair one day, and we saw this plane come up, and said, “one of theirs.” We just threw the pushchair and threw ourselves under a hedge, and just watched as this plane machine gunned right up the road in front of us, you know, kicking up the gravel. It was extraordinary. I never forgot that one.

It still seems like you’re thinking about the future though—I’m reading the track notes for the new record, and for “Crowlink” you basically say, I’m stepping out of the past and into the future. It sounds like you don’t feel optimistic. I thought that maybe you would feel optimistic about something, but it seems like it might be the opposite.

I suppose I feel optimistic, because there’s people who think the same way I do. The thing is, there’s still these songs I haven’t yet recorded that I think I’ve got to. Before it’s too late. It’s not that it’s going to be all electronics, like “Crowlink” is. That was suggested to me by my son, who went out walking along the cliffs with Matthew Shaw one day, and they just sat at Crowlink, which is the name of one of the big cliffs there on the South Downs. And they recorded the sea and the skylarks and the seagulls, and brought it back, and Matthew had written a sort of slight score underneath it, and Ossian had added some hurdy-gurdy underneath it. I was completely fascinated by it. The piece just sort of really summed up being at that cliff edge, and so it was lovely. I said, “Why don’t you put it on the album?” and he said, “Yes, let’s.” And then it sort of leads into the next album. But it will be back to the tradition, of course. Can’t let that go.

When I read your autobiography, you said that you didn’t like jazz when Ashley Hutchings played it for you. I have to ask what about it you dislike, if you’re okay with that.

Well it just makes me fidget. I just feel so fidgety. I don’t like the way people look when they’re listening to jazz. I don’t like the way people look when they’re playing jazz. I don’t like the sound of it. I don’t like the tunelessness and the tonelessness, I can’t hear it. It just doesn’t make any impression on me at all, except to irritate me. And they wear silly hats. I know I wrote that in the book, because it’s true, I just don’t like it. I like boogie-woogie, I like Jimmy Yancey, and I love the blues, but then they go and spoil it by playing jazz (laughs). Nobody’s perfect.

I can’t help it, you know? I’m sure a lot of people feel the same way about folk music, maybe it drives them nuts as well.

I’m so glad that you’re making music right now and I’m very excited to see what happens next. I hope that you’re able to perform some of these songs again at some point for people.

We’ve got one booking lined up, but it’s August next year. I mean, can you imagine? That’s the first thing we’ve got coming up. It’s a long, long time to not play with your lovely musicians. But we’re all in the same boat, so it has to be. Anyway, it will all be good.

If we’re all in the same boat, I wish you and all of us smooth sailing going forward.

Oh, that’s lovely. Thank you very much Jonathan. Lovely talking to you, you've asked me some fascinating questions.

This has been an honor, I really appreciate it so much.

Oh no, it doesn’t have to be an honor. Hopefully it’s just been an interesting conversation.

How about a pleasure?

Alright, thank you. I’ll accept it (laughter).

Have a good rest of your evening!

You too Jonathan, thanks so much! Bye bye.

Heart’s Ease is out July 24th on Domino. You can pre-order the album on the Domino website.

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Melvin Van Peebles - Brer Soul (A&M, 1968)

Three years before the release of his 1971 landmark feature Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song—a controversial yet wildly popular film that went on to lay the groundwork for the blaxploitation film genre—, Melvin Van Peebles made his 1968 musical debut Brer Soul. This album is fiercely original in its specific combination of spoken word, jazz (reminiscent of Mingus, Sun Ra, and Ornette Coleman), and soul (indebted to James Brown). Each track is a rickety vignette employing Van Peebles’s melodious and atonal sprechtstimme to bring characters to life.

Throughout the album we are placed in the shoes of a conversational partner, enduring distinct monologues voiced by Van Peebles. This approach to spoken word feels markedly different from that of Gil Scott-Heron, for instance, whose text is often in non-narrative poetic verse. Van Peebles develops themes indirectly as these vibrant conversations play out, making oblique gestures towards race issues and class issues such as addiction and imprisonment. On “Mirror, Mirror, on the Wall,” Van Peebles exploits direct address, slowly revealing that the narrator is not speaking to a separate character (as embodied by us, the listener), but instead, his own reflection. While we are put in the shoes of this reflection (“Mirror, mirror, on the wall / You ever seen a bigger fool than me?”), our sympathy is tested as intermittent knocking on the restroom door meets an escalating response: “Dammit man, this toilet don’t belong just to you / You keep on knockin’ I’ll show you what knockin’ can do.” I’m reminded here of an early scene in Good Time, in which the film’s main characters wash off red dye from a dye pack in a Domino’s Pizza restroom. Often in Safdie films, as in each track on this album, the audience is in the company of a difficult character whose thought patterns directly inform the work’s structure.

Many characters throughout Brer Soul are fixated on a need or desire. This creates thought loops that are particularly fit for the structural interplay of musical themes. “The Dozens” highlights this facet, portraying a person forced to beg for money to feed an addiction. As his monologue progresses, the musical accompaniment traces emotional highs and lows: a walking tuba underlies recurring moments of confidence and determination while limp glissandos from the sax and guitar punctuate moments of defeat as the narrator falls back on his refrain: “I see, I see.”

Van Peebles’s enduring sense of humor brings light to the album’s loose structures and otherwise tragic figures. If there’s a reason why Van Peebles’s work sits under-recognized and lesser-excavated today, it’s the utter resistance of respectability within his work. By the time he had released Brer Soul—an unconventional work by any means—the Chicago-born artist had served in the U.S. Air Force, had become a successful writer in France (publishing four novels in French), and had directed several short films and a feature. From there he continued to climb distinct professional ladders, writing an award-winning Broadway musical and accomplishing a several year stint as an options trader in the Stock Exchange that verged on a longform performance piece.

Nonetheless, his work has intentionally toyed with or otherwise disregarded the racial discomfort of white audiences, rarely focused on gaining sympathy or respect. Van Peebles’s level of concern over what a white audience might think is well-illustrated by the title of his unpublished essay, “How to Eat Your Watermelon in White Company (and Enjoy It).” This tendency towards provocation sets him out as a forefather to figures like Kanye West and Pope.L (the self-proclaimed “Friendliest Black Artist in America”), artists who use entertainment to court repressed images of Blackness so that they may challenge and confront them. —Leah B. Levinson

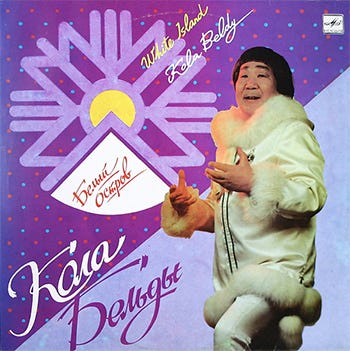

Kola Beldy - White Island (Melodiya, 1989)

Nikolay Ivanovich “Kola” Beldy had a remarkable life. Born in 1929 in a small village about 200 miles from Khabarovsk—one of the two historical administrative centers of Russia’s easternmost subcontinental regions—Beldy belonged to the Nanai people, the Shamanistic Tungusic tribe with a mysterious history. For the last hundred years or so, there’s been an ongoing debate concerning exactly who the Nanai are, where they came from and how they relate to the other indigenous peoples who at some point called the banks of the Amur their home. Now scattered between Russia and China, the Nanai are actually going through a renaissance, as there are about 20,000 of them living right now, as opposed to the 5,000 who lived in the USSR at the time of Beldy’s birth. The Nanai happened to live in the area heavily used as a building grounds for numerous Gulag camps, which only meant that the Stalinist forces at work had less use for them than it was possibly imaginable. However, the USSR’s actions towards the Nanai could hardly be described as “genocidal.” The Nanai were, strictly speaking, left to their own devices in the land that was both familiar to them and changing to something they had no prior knowledge of, in the society both unwelcoming to them and completely unconcerned of their well-being.

Already Russified for at least a hundred years, the Nanai still managed to salvage some of their traditions and used them as basic principles for their own organisation and survival. When Beldy’s father died just as his son turned three, his mother remarried. According to Nanai wisdom, becoming a wife again means that her child has no way of seeing her anymore. Beldy was placed in a Soviet-administered orphanage which, like any orphanage in the USSR at the time, was at least partly run according to the theories of the famous revolutionary educator Anton Makarenko. Makarenko promoted “self-deciding child collectives” as the only means of development and education. Needless to say, the way such theories were promoted by educators who were not closely familiar with the way Makarenko himself practiced them was extremely damaging and cruel. Add to this the overall misery and squadliness of the Far East at the time, and it’s no wonder young Kola suffered from such an awful case of stutter that it practically prevented him from talking in complete sentences.

Without much opportunities in life, he ran away from the orphanage as soon as the Great Patriotic War began. Illegally deducting his date of birth to be considered old enough to serve, Beldy found his place as a cabin boy on a cruiser and got a fully fledged experience of the violent hellish frenzy that was the Pacific theater of World War II. Remarkably, not only he survived, but managed to earn a respectable number of military awards and learned to sing and dance in the official ensemble of the Soviet Pacific Fleet.

Though initially after the War he settled on dead-end jobs in the Navy, it was Beldy’s artistry that eventually propelled him to the heights unreachable for the rest of Nanai. In 1957 he travelled to Moscow, hoping to impress anyone with his musical talents at the 6th World Festival of Youth and Students. Not only did he succeed, but the young singer impressed the most important people in the Soviet culture at that time: Sergey Mikhalkov (author of the lyrics to the Russian national anthem and the father of Andrei Konchalovsky and Nikita Mikhalkov, two of the country’s most celebrated filmmakers) and Yekaterina Furtseva, the future minister of culture during the Khruschev era). Mikhalkov and Furtseva both gained a sense of Beldy’s potential utility to the Soviet estrada, the official pop music continuum of the USSR, and so, the star was born.

Kola Beldy’s video to “I’ll Take You to the Tundra,” his 1972 smash hit that remains ingrained in the memory of anyone born in the USSR, attests to the qualities Furtseva and Mikhalkov saw in the young Nanai war veteran with a heavy stutter. His appearance and his unusual voice, very much on the fence between the traditionally accepted men’s baritone and tenor, made for a great representation of indigeous Far North peoples in the world of estrada. At that time it meant that Beldy was an ambassador of the Kola Peninsula, the Taiga, the Far East, the Chukchi Peninsula, Kamchatka and the native people in the world of officially accepted Soviet culture. It didn’t matter that the Nanai had nothing in common with, say, Sámi people, including the skin color; Beldy was the avatar of anyone who lived in the lands of ice, snow, deer and violent winters.

Beldy, however, had an uncommon (among the estrada stars) taste in “unofficial,” underground Soviet culture. For instance, his live performances were famously way more jazzy than was usually allowed, and so it seemed like a practical choice for Sergey Kuryokhin, the poster boy of the ’80s Soviet underground, to include in the performances of Kuryokhin’s own Pop-Mekanika, the free improv-cum-free theater ensemble of traveling musicians, actors and singers. Beldy obliged, yet Kuryokhin probably had no way of knowing that the Nanai superstar was working at the same time on his own avant-garde project.

Which, come to think of what Beldy himself said about it, didn’t really sound too avant-garde at first. The concept behind «Белый остров» (Beliy ostrov), the album he eventually released in 1989, formed during the beginning of Perestroika. When Beldy got full creative control of his own music from the state-run Melodiya label and decided to finally record the number of traditional songs that he collected during his journeys to the Far North, he was set on translating them into Russian to reach a bigger audience and sought the help of journalist Leonid Kushnarenko, who worked with Beldy in tandem. Though reportedly, as Beldy’s widow Olga Aleksandrovna claimed she was told by Kushnarenko’s wife Yulia Gorzhalzan, they spent a huge amount of time trying to get it right; it’s actually very debatable that Beliy ostrov’s translations bear any resemblance to what was presumably collected. For starters, none of them knew the languages of all the peoples Beldy claimed to collect songs from, and they never sought the knowledge of the actual speakers. And, as was beautifully demonstrated by Yoiking with the Winged Ones, the album of the Sámi yoiks recorded by the Sámi historian Ánde Somby, at least the Sámi songs, a number of which are included on Beliy ostrov, have no lyrics at all except short repetitive phrases.

Does it matter when you consider Beliy ostrov? Without a doubt, the reported scope of work on collecting the songs themselves demands a complete ethical understanding of the task, which Beldy clearly lacked. On the other hand, there were no other people of the Far North who had the status Beldy had and the recording powers he obtained, so there’s no chance we could’ve heard this album without him anyway. And the most important thing is that a) it rocks, b) it’s actually a very poetic representation of the lives of the Far North peoples, imagined or not.

The music was composed and produced by Aleksandr Lavrov, the former pupil of Rodion Shchedrin who clearly didn’t have a taste for the traditional his more famous teacher always peculiarly demonstrated in his works every chance he got. It verges between the ’80s industrial and more mainstream forms of synth pop, though always staying in its own lane. The big drum sound, the beautiful melodies played on the cheap Soviet keyboards and the heavy use of various traditional percussion and mouth organs create a pallet that could be immediately associated with the Far North by anyone who had spent time there. As I myself have grown up in Murmansk, the largest city above the Polar circle in the world, I can definitely attest to it. Lavrov and Beldy seemed to hope to be doing something close to the soundtracks of the ’70s and ’80s Soviet TV documentaries about the Far North. The unmistakable shiver that keys usually break into music, the heavy echo on Beldy’s impossibly large voice and the slow beats that facet the melodies—all of this could convincingly be features in any state-approved doc.

But the way these (and other) characteristics of sound were used by Lavrov and Beldy—in conjunction with Lavrov’s own compositional techniques—turned the whole record into some of the most frightening and cold music recorded in the USSR, despite its sometimes cheerful and celebratory triumphant lyrics. The first track, «Хозяин леса» (Hozayin lesa, “The Master of the Forest”), dissolves halfway truth into an extended mouth organ and percussion duet that’s 100% emblematic of the strange turns this music takes, aiming to arrive at some forgotten and unmistakable horrid, dark, strange memory. Even when the music gets downright beautiful, as it does on «Рыбачка» (Rybachka, “The Fisherwoman”), it never once stops reminding you of the dangers of life in the Far North, where the climate is merciless and everyday life was traditionally centered around hunting. As Kola sings the ode to his imaginary son who’s already hunting with him in the woods, as he tells us the story of the bear and the deer, as he proclaims that “a Russian, a Ukrainian and a Georgian” could all be “united together with the qualities of the song,” his voice disappears into the landscape of alien sounds that seem broken beyond repair: the brooding noise of ambience, the startling shock of drums. In many ways, this is a perfect aural representation of the way the Nanani, the Chukchas or the Khanty had lived for centuries. But it also works as a story of their century-long repression and extinction, the story of the pain and the memories which are the only things left when someone takes your story, your tradition, your life away from you. —Oleg Sobolev

hoon - unfinished#1 (code, 2000)

To say that unfinished#1 by hoon is an overlooked entry in Ryuichi Sakamoto’s discography would be an understatement, because it doesn’t even appear in any of his online discographies. Nor is it officially credited to him, but rather to “ESU” + Yoshihiro Hanno, although some sources hint to hoon being a collaboration between Sakamoto and Hanno.

The album was bundled with the first issue (out of four) of the magazine unfinished, edited and published by code, an artist collective active from 1999-2005 consisting of Shigeo Goto (editorial director and interviewer), Hideki Nakajima (art director), Ryuichi Sakamoto (musician and composer) and Norika Sora (creative director). The magazine consists of interviews with several figures, ranging from musicians, both Japanese and international like Brian Eno, HIROMIX, Mika Vainio and Ilpo Väisänen of Pan Sonic and Haruomi Hosono to Japanese astronaut Mamoru Mohri and the 14th Dalai Lama.

Only on the last page of the magazine is the included mysterious CD (which is almost entirely white, save for a small beige dot) is acknowledged. On that page, one finds a tracklisting paired with Hanno’s notes about the production. He talks about the process which involved electronic communication, since him and Sakamoto were thousands of miles apart physically, except when creating the final mix. Hanno describes his musical ideas for the project as being “created by stepping on beautiful stained glass, and arranged in lines.”

The first track on the album, “eclipse,” sets the tone for the rest of the album. It begins with a fragile sounding piano with increasingly intense clicks-and-cuts work, presumably from Hanno since Sakamoto didn’t release anything nearly as aligned with the Mille Plateaux / Raster-Noton glitch aesthetic yet in his career. While Hanno’s electronic cut-ups might be intense, like on “cube,” which uses a scrambled voice synthesizer to an effect of uncanniness, there’s also moments free from the radical sonic freedom of computer music around the turn of the century. For example, the uninterrupted piano and strings on “sea” wouldn't be out of place on 1996. And, while the technology used to make “play” is certainly more advanced than the primitive sampler Sakamoto pushed to its limits on Esperanto, it isn’t too far off in terms of structure. Still, the album is the start of Sakamoto’s relationship with digital audio aesthetics, and doesn’t deserve the complete obscurity.

Even if you would dig through Sakamoto’s discography thoroughly, you would probably miss this release. It shouldn't be that way, because these 43 minutes are accessible even for casual fans. Even though it was mostly created through seemingly tedious correspondence, Hanno and Sakamoto’s synergy is still remarkable. —Rose

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

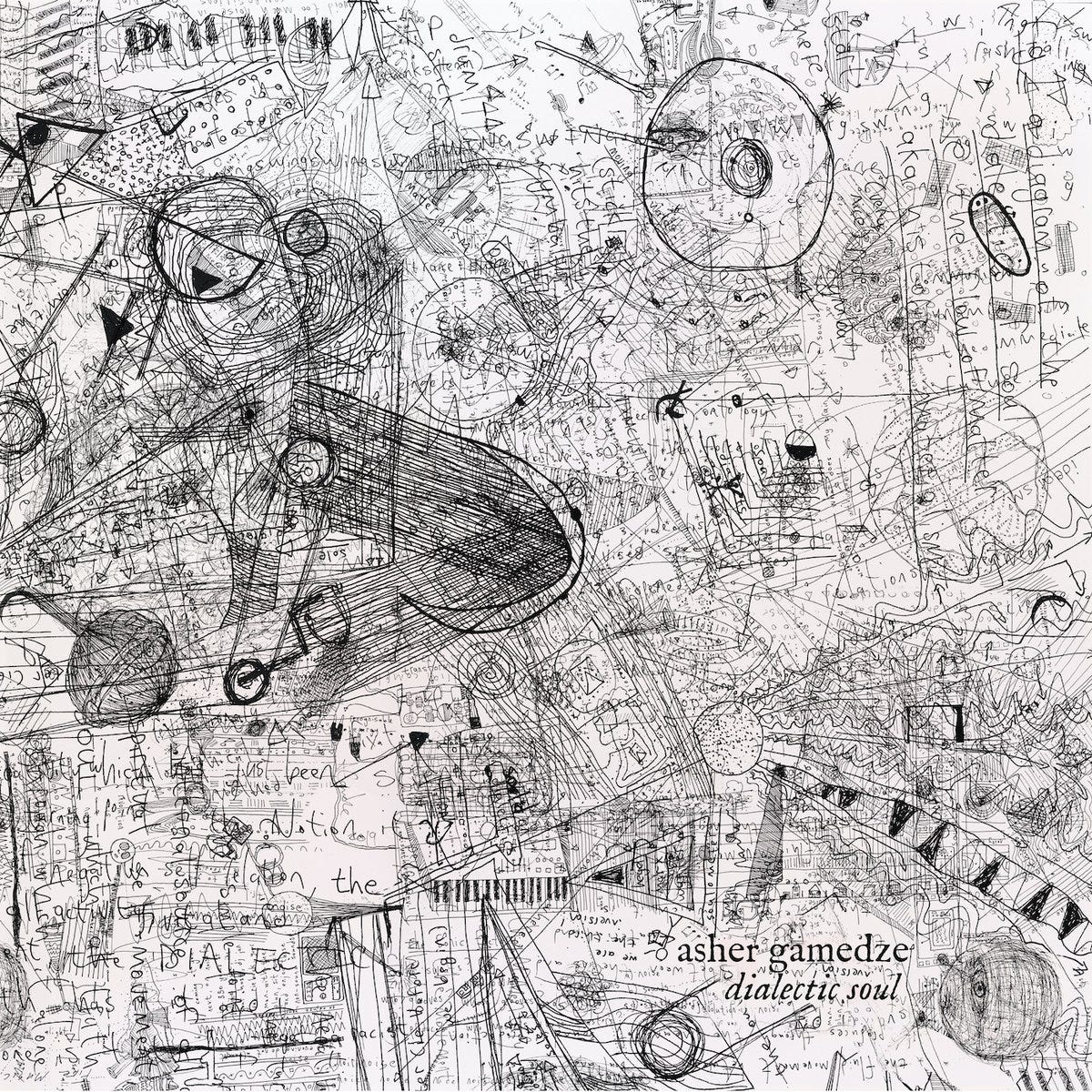

Asher Gamedze - Dialectic Soul (On the Corner, 2020)

Press Release info: This is Jazz at its most spiritual, most progressive and most appealing form. As Asher himself says: “Dialectic Soul is about motion and a refusal to remain static or stay still. It’s the commitment to be continually moving.”

Recorded live over two days at the Sound and Motion Studios in Cape Town with renowned musicians (Thembinkosi Mavimbela (bass), Buddy Wells (tenor sax), Robin Fassie-Kock (trumpet) Nono Nkoane (voc), Dialectic Soul is breathtaking in its musical vitality and expression of soul seeking truth. By incorporating the concept of the Total Art for this project, it fits perfectly within On The Corner's aesthetic of music, art and vision for creative innovation. Label art director Victoria Topping created the sleeve design working with Asher’s drawings and concept.

Asher continues: “My composition “state of emergence” introduces the themes that constitute the album; free drums representing autonomous African motion, the saxophone reflecting deeply and honestly on the violence of colonialism, the teachings of Coltrane, Biko, Makeba, Malcom and others inspired the music's positive manifestations of resistance.”

“Fundamentally, it is about the reclamation of the historical imperative. It is about the dialect of the soul and the spirit while it moves through history. The soul is dialectic. Motion is imperative. We keep moving.”

You can purchase Dialectic Soul at Bandcamp.

Vanessa Ague: From the very first moments of Dialectic Soul, it’s evident that electrifying vigor is the album’s primary force. A constant polyrhythmic pulsation in the drums and bass drive this ever-forward motion, a motion that South African percussionist Asher Gamedze has noted is the underlying inspiration behind the music. The ethos behind the record stems from the reclamation of historical narratives and the need to continuously push forward—and the resulting music encapsulates this idea with incredible precision and expertise.

It’s Gamedze’s debut LP, and it’s a formidable way to enter the scene of recorded jazz. Nods to the genre’s history are apparent in each piece, perhaps most notably a continual harkening back to the transcendence of 1960s spiritual jazz. As I listened to the record, I was struck by its connection to that era of music-making. It’s desirable to compare this style of music to that of John Coltrane, an artist whose influence looms large in the overlapping worlds of avant-garde music and beyond. But Gamedze makes the comparison feel almost tenable: his group’s music pays homage to the early days of spiritual jazz through meticulous inclusion of musical elements like powerful unison, overblowing, complex rhythm, and harmonic tone painting, but launches it into a fresh space for out current time by centering the idea of forward motion built on revolutions past.

While each piece on the album boasts a high level of execution, it’s “Interregnum” and “Eternality,” two back-to-back tracks at the center of the record, that are the most outstanding. “Interregnum” brings together the powerful forces of thumping rhythm and defiant spoken word; “Eternality” begins with dissonance that seeps into a seamless, interlocking unison, with a standout saxophone solo by Buddy Wells that calls to mind the prowess of artists like Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman. These two tracks solidify Dialectic Soul as a mighty force, and bring together the sonic and philosophical elements that Gamedze seeks in its creation. As a whole, the record succeeds in its impeccable weaving together of historical style, the present moment, and the persistence of motion.

[9]

Oleg Sobolev: Gamedze’s album serves as a reminder of the extreme power of repeated listening and curiosity. If I’d rated Dialectic Soul after the first few times I managed to get through it, it’d be a solid 5. I thought the music was too simplistic, too uninteresting, too acknowledging of the Cape Jazz traditions in which it is rooted. In particular, the use of vocalist Nono Nkoane on this recording seemed to be a straight homage to Johnny Dyani’s classics like “Ntiylo, ntiylo” and “Magwaza”. Short version: I was bored. But it all changed after I read Gamedze’s MA thesis in African studies. As I read along, I kept nodding and nodding in approval and became more and more fascinated by the detail and stories about Cape Jazz I’ve never paid any attention to. But it was Gamedze’s devotion and deep understanding of Amílcar Cabral, one of the greatest political philosophers of the 20th century, that won me over.

Strangely enough, this didn’t really influence my time spent with Dialectic Soul, but it did make me pay more attention, which is one of the things Gamedze’s academic work demands from anyone encountering it. The results were immediate: I figured out how truly lonely, desolate and simultaneously powerful this music is. It’s rarely built on the strength of the whole group but instead prefers to shape itself through duets and trios, and in effect the band plays around the triumphant melodies that reach the kind of duality that could be as well implied with the title. It’s soul in the classic Billboard sense of the term, and it’s soul as in the divine, of a powerful mechanism overbearing your own existence that sometimes paints the beautiful but only uses dark colors.

[7]

Nick Zanca: As of late I don’t consume many recent jazz releases. That’s not to say that the idiom no longer holds interest for me—it’s just that from my past few chance encounters, I have more or less perceived that its preeminent contemporaries largely favor reinstating the framework its forefathers developed over attempting to elevate it. With those limitations laid out, Gamedze has clearly punched above his weight here with this debut—these compositions seamlessly bridge the gap between the elegant melodic simplicity of the Cape Town vanguard and the kinetic collective energy of fire music across the Atlantic. From the opening side-length suite, he postures himself as a generous bandleader to this quintet, leaving ample room for each player to linger in the limelight, supplementing their solos with finely-tuned tom flourishes. The spatial properties and crisp precision in production of this two-date session instantly brought to mind Manfred Eicher behind the boards—no doubt that this could have been a beloved ECM release were it tracked forty years ago. Dialectical Soul is not only a warm and welcome new addition to the spiritual jazz canon but a sonic document of resistance to the colonial impulse; proof that, in Fanon’s words, “mastery of a language affords remarkable power.”

[7]

Marshall Gu: The term ‘telepathy’ often comes up when discussing jazz for how some groups are able to cut entire albums in a matter of a few recording sessions with no prior rehearsals together, and that term readily applies to Asher Gamedze’s debut album. With half of the band coming to Cape Town from across Gauteng, across the country, they scarcely had time to practice together, and yet, each of these six songs feel so natural—you’d hardly believe they were recorded in just two days.

As a drummer, Gamedze comes from a rich lineage of both American and African drummers, and the music reflects that. “States of Emergence: Thesis” is the John Coltrane-Rashied Ali sax-drum workout of Interstellar Space carried out by Gamedze and saxophonist Buddy Wells. “Hope in Azania” feels like an unearthed Blue Note would-be standard. “The Speculative Fourth” is Ornette Coleman’s “What Reason Could I Give?” re-envisioned from chaotic future vision to the tumultuous present with vocalist Nono Nkoane as Asha Puthli and bassist Thembinkosi Mavimbela as Charlie Haden. As a bandleader, Asher Gamedze is able to inspire muted yearning from trumpeter Robin Fassie-Kock and patiently unraveling soliloquies from Buddy Wells, and the album’s title is reflected in songs like “State of Emergence: Antithesis” and “Siyabulela,” wherein the band members discuss and explore topical themes of politics and religion, even though hardly any words are being exchanged. Did I mention how good this album is yet? It’s good in a way that I can’t believe it exists.

[8]

Samuel McLemore: I’ve gone on record before to complain about contemporary jazz musicians being stuck in the past, making albums that refuse to take the past 50 years of musical and technological development into account, and sad to say Asher Gamedze’s debut album is no different. Considering the musical landscape we live in now, jazz’s continued insistence on live performances with minimal post-production and editing can make even the best material sound typical. For a genre that so highly valued sonic exploration to be now bound to a limited palette can be frustrating to hear. I also can’t deny that even when it’s old-fashioned, I still just love jazz. It was my first real musical discovery, and it has never been far from my heart since. Part of my criticism stems from my earnest love for the genre, my respect and awe for the radical ambition and intelligence of the legendary jazz artists of the past, and my desire to see what can come next from the artists of the present.

While Gamedze and company don’t quite manage to push the sonic envelope and expand the boundaries of what’s possible in jazz, they do manage to do the second best thing: make a good album. Recorded in just two days, Dialectic Soul has a casual feel that makes even the fairly weighty thematic material sound welcoming. Bassist Thembinkosi Mavimbela and tenor saxman Buddy Wells deserve real credit here: the former is the most propulsive player on the record, swinging hard and often without resorting to cliche, while the latter exhibits a real Jackie McLean-esque ability to switch from swinging riffs to freeform improv in the same solo and make it all sound stylistically whole. Trumpeter Fassie-Kock is the noticeable weak link, not so much for any bad playing on his part (because of the way the album plays with traditional forms, you could argue that there isn’t a “bad” moment on the record), but because his playing doesn’t exhibit the passionate drive or depth his bandmates do.

In the end, it’s a good album—no more no less. I imagine those who are more able to brush aside or ignore the meta-criticisms of jazz as a whole I outlined above might even be able to say it’s great.

[6]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I must confess that the opening suite did not move me. I appreciate the attempt at some sort of dialectic—as evidenced by the titles of each movement—and how it reminds me of my experience with other 20-minute Cape Jazz pieces. With Johnny Dyani’s “Lonely Flower in the Village” and Dollar Brand’s “Jabulani-Easter Joy” (African Space Program version), two very different works, I find immense joy in the amount of space that is present. It’s maybe not as apparent at first glance, especially with the latter, but these songs feel immense due to how the players interact: there’s a constant push-and-pull between constant interplay and of the band members all doing their own thing. I get that sense here, but there’s not enough tension derived from this tightrope walk; it produces tedium, not awe. Other tracks are flat-out gorgeous though, with “Siyabulela” and “Hope in Azania” really channeling the beauty of Cape Jazz at its most unashamedly pretty. These go down smoothly; maybe that’s all I really want right now.

[5]

Asher Gamedze and Angel Bat Dawid in Chicago, March 2019. Photo by Julia Dratel.

Sunik Kim: The best free jazz is good because it unapologetically goes to extremes. These extremes, in turn, provoke extreme reactions: Ascension sounds like a horrible, senseless racket to me on some days, and like a blinding message from God on others. That’s the risk of fully committing: you might lose more people than you gain, but for some, the payoff is worth it.

One consequence of the ‘extremity’ of free jazz is that there tends to be a kind of ‘flattening’ of quality: at a certain point, it becomes hard to argue why this 40-minute blown-out screech-fest is better than that one. Ultimately, this reduces the listening experience to one of more-or-less pure intuition: this one just speaks to me, this one doesn’t.

I make this preface because, to the first point, Dialectic Soul fails to fully commit to anything, instead flitting between different approaches—freer-leaning improv blasts, more rhythmically-bound post-bop-ish sections, spoken word, vocal jazz—none of which really take it there in a particularly exciting way.

To the second, and ultimately more damning point, Dialectic Soul lacks a certain quality, spark, energy, that can’t necessarily be put into words. The formula is there, but there are only lulls, pulls, and no crests, pushes. The momentum is middling at best, and the players almost sound bored, like they’re blowing at half their capacity. Ultimately, this is the death knell for freer-leaning jazz: if you can’t instantly sense, feel, absorb the energy emanating from the players, from the recording, then nothing else—not melodic interludes, not vocal additions—will save it.

[4]

Sam Tornow: Dialectic Soul begins with a declaration of a theme on its mammoth introduction track, “State of Emergence Suite.” First we have the drums—pure frenetic energy sweeping around the kit. It’s unhinged free-jazz drumming, lightning-fast, and physically demanding. The rhythms and cymbal play make the listener question how it’s all one person. However, if you start listening closely, you’ll hear the pulse, beating forward and slightly out of time.

Then we have the saxophone: it’s fat, obnoxious, and screaming. It sneaks in and out of the scales, teasing out the dissonance it could unleash at any moment. At times, it sounds a little Coltrane, but Coltrane’s music was a prayer. This isn’t a prayer: It’s a message of hate. And occasionally, you hear Pharaoh Sanders’s signature overblowing—there’s heat coming from the horn.

Dialectic Soul is a record about movement, resistance, and colonialism; the drums are free spirits, and tenor saxophonist Buddy Wells’s playing illustrates the violence of African colonizers. On his Bandcamp page, the drummer elaborates on the comparison: “Fundamentally, it is about the reclamation of the historical imperative. It is about the dialect of the soul & the spirit while it moves through history. The soul is dialectic. Motion is imperative. We keep moving.”

And the record does keep moving. Whereas some free-jazz records mull around the same sounds like meditation, Dialectic Soul moves forward. After“State of Emergence Suite,” the record moves into a slower healing sound on “Siyabulela,” a track based on a popular South African church song. Here, singer Nono Nkoane takes control with her gorgeous, angelic voice—fitting. From there, the quintet drifts between styles with each track, never allowing for one idea to take over for more than a few minutes, fleshing out this theme that in order to grow, we must move.

The back half of the record is a comedown compared to the first few tracks. Gamedze offers up masterful playing and soulful composition, although without the same burn and originality of the early tracks. But Dialectic doesn't stop moving, growing, and fulfilling its thematic goals: It just takes more time to do so during the final 20 minutes.

[7]

Nenet: In a time that still favors the ill-treatment of workers, police brutality, deportation, union-busting, mass incarceration, consumerism, and most of all, white supremacy, this record works as a much-needed battle cry: Dialectic Soul is music for the resistance. To talk about the particulars of its sound—the masterful shifts in tempo, the crying horns, the chasmic pulsing of the bass—without remembering free jazz as a manifestation of Black freedom wouldn’t be entirely truthful. The creative music that makes the album carries a sense of undoing, a going away of old structures. “State of Emergence Suite” comes with a tangible challenge: to listen and learn, each tone working as an open invitation to contemplate the reality we uphold. In “Siyabulela,” the tenor sax and trumpet breathe together seamlessly, offering a sense of reprieve: the voice of Nono Nkoane gliding peacefully throughout eight minutes of pure bliss. The six pieces in Dialectic Soul, long but never redundant, make for a strong listening experience, one that is still very much needed.

[8]

Average: [6.78]

Reizen - Works, 2020 (Senufo Editions, 2020)

Press Release info: Works, 2020 includes two new compositions, Different Speeds for Decay Instruments (for electric piano; the score of this piece adorns the front cover) and Music for Glass, Plastic and Rubber.

You can purchase Works, 2020 at Bandcamp.

Sunik Kim: Why am I still listening to this? If I find myself asking that, usually the music in question is actually good, not bad—with the latter, it usually only takes a few seconds for me to decide something isn’t worth my time. ‘Experimental music’ is a constant balancing act; the best work almost always toes the line between complete parody and unparalleled beauty. Works, 2020, on the surface, leans towards the former—on paper, this is nearly 40 minutes of nondescript, repetitive chimes and clicks, navel-gazing ‘Sound Art,’ the kind of thing you nod politely at in the gallery. Why, then, am I still listening to this? The ultra-minimalism at play here reminds me of what I often belatedly realize is ‘depression music’: sometimes I’ll unknowingly enter months-long spans where I only want to listen to Bernhard Günter. Anything louder, faster, denser, is too intense, too grating, tries too damn hard, irritates; but silence feels like a terrifying void too, so I settle for something just above silence, almost to keep me company. As with Günter, so with Reizen: the gap between knowing, theoretically, that this music is utterly ridiculous, and enjoying it anyway, makes for a singular listening experience. It reminds me that, for all our attempts to categorize, rank, quantify music, it often comes down to something totally unknowable, intangible; it’s good to be kept on your toes.

[6]

Mark Cutler: Fun fact: I listened to the first track with my boyfriend, his housemate, and his housemate’s new love interest (too soon to call her a girlfriend). None of them have any real experience with avant-garde music, so they spent the first five minutes roasting me pretty hard for listening to this. Yet by the sixth or seventh minute, they were engrossed too. “It just changed again, right?” “Okay, that time was definitely different!” This piece has such a simple construction, but there is a brilliance to its gradual evolution which—as I can personally attest—even those completely unfamiliar with minimalist music can appreciate. I think, at one point, the housemate’s lady friend had actual chills.

[8]

Samuel McLemore: In many ways the fundamental basis of the human capacity to listen to and appreciate music lies in our ability to track minute variances in rhythm and pitch when presented with a series of sounds. This ability can be trained to great effect, but is subconsciously triggered every time we hear two sounds in succession with each other. On Works, 2020, composer Reizen takes a similar path to minimalists like Alvin Lucier and Laurence Crane, building compositions by preying on these fundamental human sensory processes instead of more traditionally “musical” means. The effect can be something similar to a classic Magic Eye picture, where the primary structure of the piece can only be sensed from underneath the obvious surface. But unlike the Magic Eye picture, where in a flash a massive sensory overload forms into a single legible picture, here we have almost the opposite: a single note is complicated into an unstable motif which morphs constantly, never giving the listener a chance to rest despite the slow pace and ample amount of silence present in the piece.

The second composition opens the field up quite a bit by playing on a group of “non-musical” objects. Not only is it surprisingly thrilling in an acoustic sense, having a lot in common with the Ftarri school of onkyo-influenced free improv, but it also lays bare the fallacy of labeling certain sounds as being “musical” or “non-musical.” The fact is, while music may be based on natural laws and principles, what makes sound into “music” is solely human beings and their perception of it. While this concept isn’t exactly new ground in the world of modern music, by marrying a style of composition based on the manipulation of basic acoustic principles with the Ftarri approach of combining homemade instruments and indeterminate results, Reizen has managed to bring a new and personal flavor to this corner of the music world.

[8]

Nick Zanca: During a lecture given in Toronto in 1982, Morton Feldman offered this insight: “I’ve been living with the minor second all my life and I finally found a way to handle it.” Indeed, the interval with the tightest proximity in Western music tends to pose a compositional challenge: to rely on it too much will often come off as intemperate but utilize it in the right places of a piece and it will become a harmonic vehicle. Reizen takes half the duration of this first piece to hone in on a symbiosis too subtle between a high note and the flat below it, detaching and realigning ad nauseam before finally arriving at a minuscule tonal expansion twelve minutes in. When the piece briefly escapes its paralysis of range towards its tail, the effect is almost comedic and I question the standstill that surrounds it. Ultimately, the second piece suffers the same durational fatigue as the first; I almost lost interest in its palette of piezos through ping-pong delay before the most satisfying section of this record emerged at its end—the interplay of all three elements at once evokes one of my favorite recorded exercises in percussive hypnosis. I normally have more patience for this realm of reduction than I do for other people but not today.

[4]

Vanessa Ague: Listening to Reizen’s Works, 2020 is an extraordinary exercise in patience. With these two new pieces, he explores rhythmic patterns more so than melody or harmony, experimenting with the uncertainty of changing beats and gradual buildups. The result is music that makes silence as much a part of its execution as sound is.

“Different Speeds for Decay Instruments,” where Reizen’s driving force is the sparse repetition of one beat, embodies this idea of silence being an equal counterpart to sound. At first, the pauses between notes feel like eternity, but gradually, they grow and change, and new pitches become part of the fold. It slips by almost unnoticeably—the uncomplicated nature of the music becomes entrancing. As I listened, I noticed my brain attempting to fill in the blank spaces, or assuming when there’d be another beat. But surrendering to the unpredictability yields more resonance than trying to create sound within the silence.

Reizen’s second work, “Music for Glass, Plastic and Rubber,” explores a similar ethos, but includes a gradually building drone alongside the pitter-patter of repeating rhythm. It’s as if this piece builds upon the first, adding in new elements to provide deeper exploration of the ideas he’s already laid down. Essentially, this is an album about uncovering the beauty within the ultimate simplicity, imploring us to listen deeper. I don’t think it’s the easiest thing I’ve ever asked myself to do when listening to music, but it was one of the more rewarding sonic paths I’ve traveled.

[8]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Reizen’s work has never been this minimal, this sparse. Throughout his career, he’s wavered between field recordings, electroacoustic noodling and ambience, creating a stillness in the listener regardless of the music’s busyness. Here, he presents two tracks that require a stillness to even approach it, to get a sense of everything going on. The ideas that underpin “Different Speeds for Decay Instruments” are the same as those on “Different Speeds No.4” and “Different Speeds,” but the result is wholly different: the latter recordings felt akin to Japanese new age in both the sounds and the “silence” (the surrounding environment). It was cute, it was precious. This piece is more austere, and with it is a demand to approach it as such, to take in every individual note and resonance thoughtfully, and to be struck by them with a gravity that is only concomitant to intense concentration (more than anything, it makes me think of Winds Measure). “Music for Glass, Plastic and Rubber” is even better, an ASMR’d percussive dance that gradually evolves into a queasy hurl (thank the rubber). It has the impression of an at-home lab kit for kids: the elements are simple, but it comes together in a small but astounding spectacle.

[8]

Shy Thompson: As a child, many of the things that my mom did for her own enjoyment didn’t make much sense to me; the most confusing thing was her curio cabinet, filled with all sorts of odds and ends that she collected over the years—fine china, porcelain figures, music boxes, and a lot of crystal angel statues. They were ostensibly toys, as far as I understood, but she didn’t actually play with them. She would occasionally flick a switch that lit up the inside of this prison for dusty antiques and look inside, but she never took anything out; the curio cabinet only opened when something new was going inside. For her 35th birthday I got her a crystal angel that sits atop a color-changing rainbow lit base, and was disappointed that she only ever turned it on once—when she took it out of the box, and then never again once it was sentenced to life in the cabinet. As an adult, I have to confess that I still don’t really get it. I have a pathological aversion to things that are not practically useful, or that take up precious space.

Rather, I suppose I should say I thought I didn’t get it. Having given a lot of thought to why my taste in music developed the way it has, I think my love for quiet music sometimes speaks to a similar need. For many—myself included—music serves a practical need: to dance, to introspect, to relax, or otherwise help you feel however you want to feel. Music like what you hear on Reizen’s Works, 2020 does none of that for me; it’s simply something small, interesting, crystalline. The sounds of the titular objects in “Music for Glass, Plastic and Rubber” don’t make me feel any particular way; feeling has nothing to do with why I like it. Other microsound artists like Rie Nakajima excite me, light up my imagination, and take me on a journey of sound and space; Reizen keeps me right where I am, which is right where I want to be at this particular moment in time—I like these sounds for what they are, not what they suggest to me. I’m perfectly happy to sit still in a quiet room, and make some room for these sounds in my collection. It turns out I’m my mother’s daughter after all.

[9]

Oleg Sobolev: Every summer from the age of 5 until 14 I went to my grandparents, who lived in Tatarstan, and sometimes my parents went along, sometimes not. It was mostly boring, though I made friends everywhere we went: in Kazan; in Zelenodolsk, the other city 50 miles west; in Vasilyevo, the semiurban village most famous for its spa retreat. I dreaded going on short trips anywhere else, because it usually meant that I’d go without my friends, the kids of my own age, and I would be the only child in a company of adults. Still, of course we went. My grandad especially loved going to the lakes of the Mari El Republic, some 200 miles northwest from Kazan. Like Finland or Karelia, two other homelands of Finno-Ugric tribes, Mari El is, among other things, famous for its abundance of lakes. Naturally every summer, tourists from nearby regions descend upon it. My grandad, though, knew the road to one lake that was completely tourist-free. In fact, it was practically free of people, period. It was called Yalchik, and we were the only people around most of the times we went there. It was beautiful, quiet, solemn, its clean tranquil waters came in sharp contrast with the besmirch Volga I was used to in Tatarstan.

Still, I got really bored. I didn’t even try to engage with nature, so much so I wished my friends were there with me or that I was in the city. Every time we went, I took a swim or two, but was always disappointed in the Yalchik’s waters, so still they were. Their playfulness clearly meant Yalchik wasn’t made for swimming, but for long walks around its shores. Which my grandparents, who were already of senior age at the time, couldn’t master, and which they wouldn’t let me take by myself anyway.

Now my grandad is long gone and my grandma is 84 and suffering from progressive dementia, which means that soon enough she won’t be able to recognize me. She already doesn’t remember my name. I really need to go visit her, and I find excuses not to every time I decide to. As the notes of these Reizen’s works echo throughout the room, I remember the numbness of the Yalchik waters, ripples on the water from the thrown pebble, my grandparents looking out of their old Lada Niva, the long walks I never made. Maybe it’s time to go now. Just put everything else to rest, dress up, buy a train ticket and leave the apartment. But not until I finish writing this blurb.

[9]

Average: [7.50]

Still from Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (Karel Reisz, 1960)

Thank you for reading the twenty-second issue of Tone Glow. Drink some water, keep your chin up, and hold fast to hope—we hope you’re well.