Tone Glow 008: Annea Lockwood

An interview with composer Annea Lockwood + album downloads and our writers panel on Irreversible Entanglements's 'Who Sent You?'

Annea Lockwood

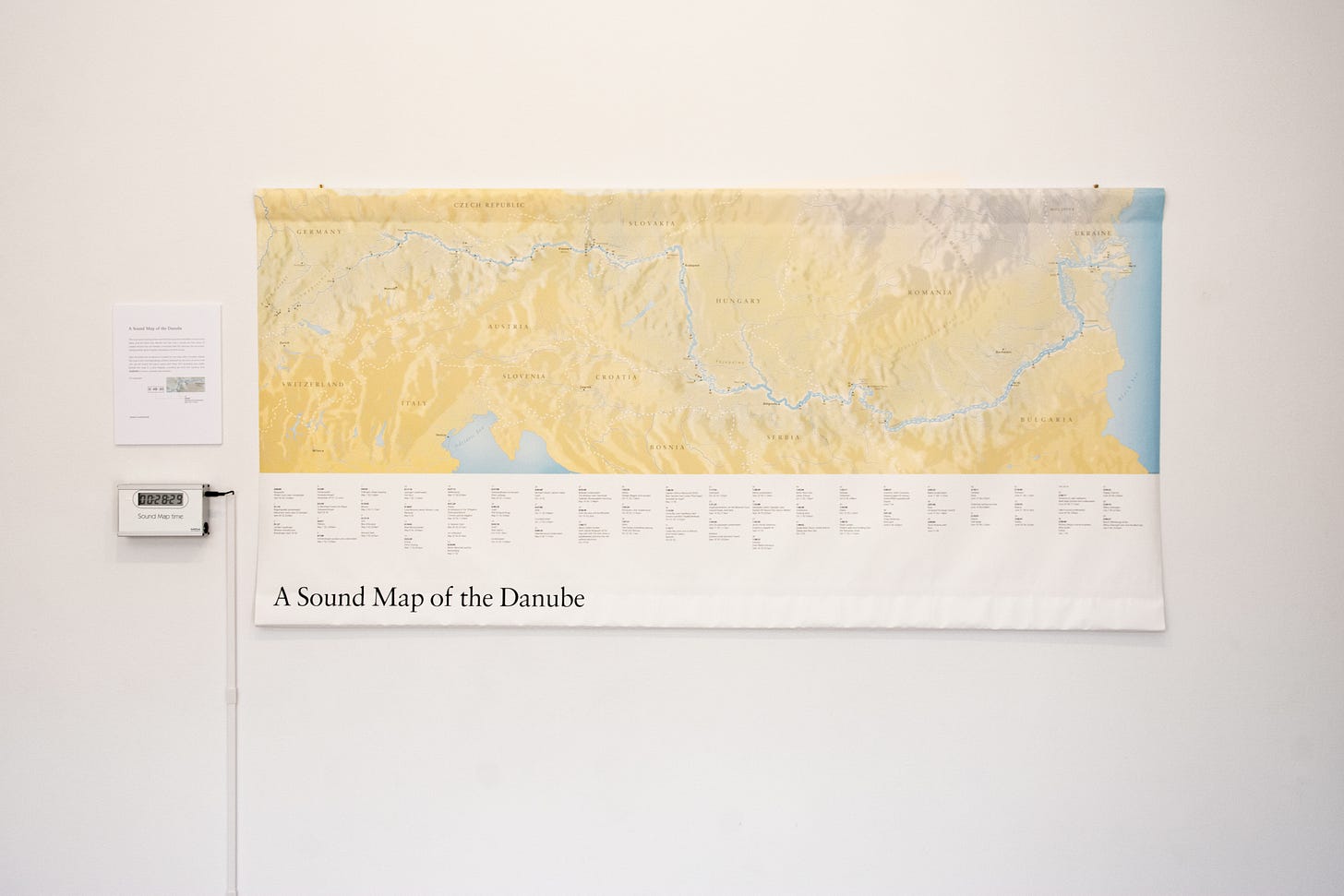

Annea Lockwood is a New Zealand-born, US-based composer and musician who has been creating sound art and sound maps for decades. Her work was performed at Chicago’s annual Frequency Festival in February, and an installation for her Sound Map of the Danube was set up in Chicago’s Experimental Sound Studio. Prior to her visit, I talked with Lockwood on the phone about her childhood, her music, Ruth Anderson, and more. All photos were taken by Julia Dratel unless otherwise noted.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: In Chicago you’ll be setting up an installation for the Sound Map of the Danube. That’s always been a very meaningful album for me—can you talk to me about your plans for the installation?

Annea Lockwood: Oh sure! It’s a 5.1 setup. When I completed the sound map in 2005, a 5.1 setup seemed to be a fairly common and possible setup for galleries and museums, in Europe especially. It seemed practical, and I like multichannel works. Speakers are arranged in a circle—there’s no relation to the normal 5.1 arrangement—so the various sites and sounds circle around the listener over time. It’s a lovely arrangement to work with. On a wall is a very big map of the river—it’s a big river (laughter)—it’s 3 feet high and 6 feet long and printed on archival canvas so that it looks and feels like a map.

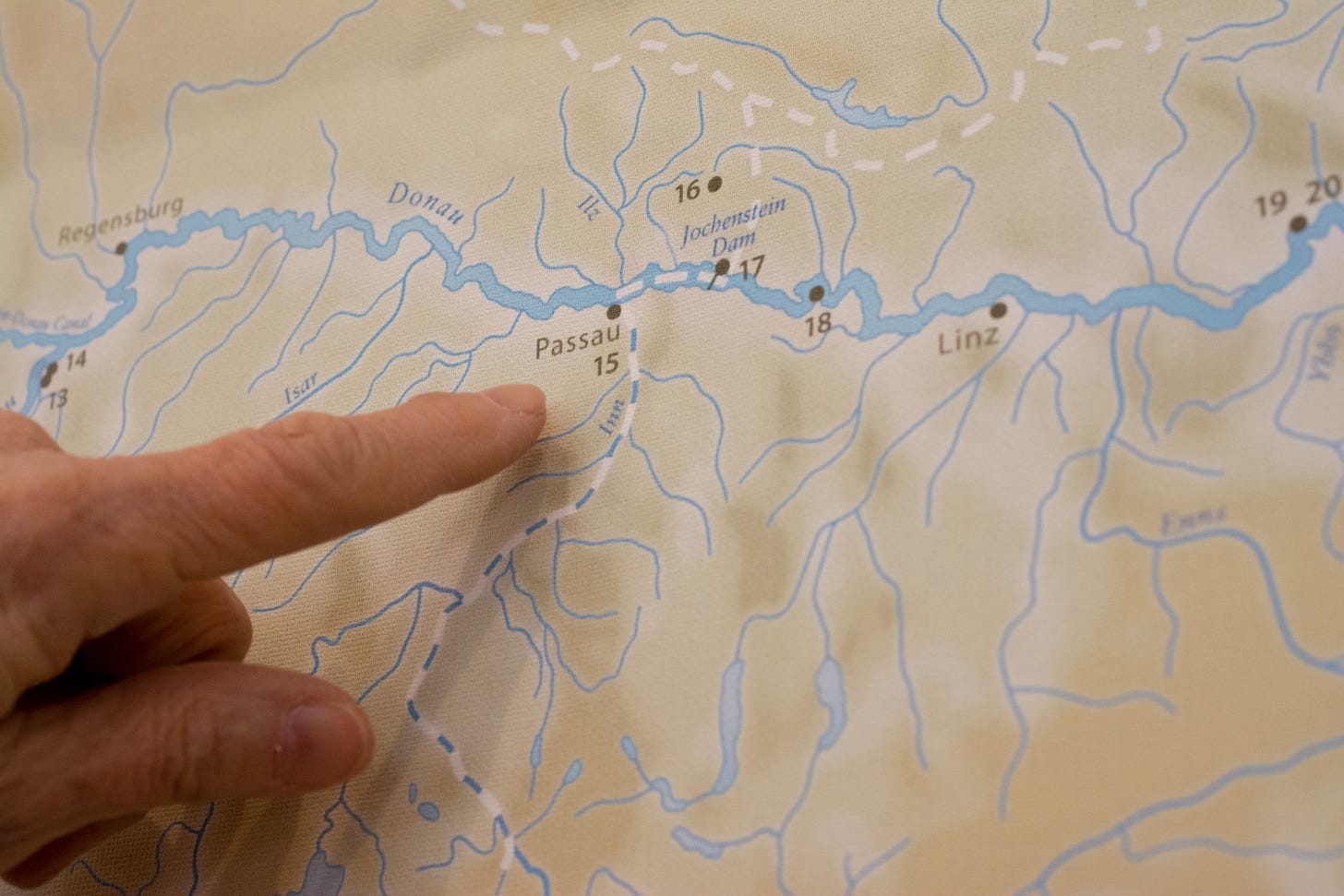

I hired a cartographer and a graphic designer to make it for me which was sort of a thrill because I’ve loved maps all my life. I don’t read them well (laughter) but I love them. It was made by an American cartographer Baker Vail and graphic designer Susan Huyser. They worked together on it beautifully and have also done the Housatonic sound map for me—that was lovely.

It was a very tricky map, we were assembling it from German cyclist road maps and ordinary auto maps for Hungary and Serbia and Croatia, and little local maps I picked up all over the place—it was a real job putting it together. The map hangs on a wall and next to it is a time display that was made for me by Roland Babl of bablTech in Austria. It gets triggered at the beginning of the sound file—there’s a special signal sent to the time display—and it counts up indefinitely. It runs on lithium batteries, it’ll go forever. It’s retriggered once the sound file is looped.

By means of the time display, you can track which part of the river you’re listening to—all sites on the river are indicated numerically going downstream. They’re named, and there are dates and times of day given for each site because people can really respond to that. And rivers do keep changing all the time at any one site. There’s other additional information—I recorded tadpoles at one site in Austria and you would never guess what that sound was so I indicate what it is. You can keep track of where you are, and I set up really comfortable seating because I think the more relaxed the listener’s body is, the longer he or she might spend with the map, and the more the sound is able to flow through the body. I’m always interested in how one’s body responds to sound.

I’ve heard a lot of field recordings, but when I listen to your sound maps they stand out because they’re clearly very powerful works. I do get a physiological response from listening to them. Though, part of that is because growing up—as a teenager—I almost drowned in the Pacific ocean.

Oh my god.

A stranger came and saved me—they put me on their back and swam back to shore. When I hear recordings of large bodies of water I generally don’t have a reaction but there’s a real sense of power when listening to your sound maps and I’ll occasionally think of that experience. I think it’s a testament to how well it’s all recorded.

Can I ask something? When listening to the sound maps and the memories come up, do they have as much of a disturbing impact as usual or is it all mitigated by what you’re hearing—how does that work? Does it make you relaxed to listen to water (laughs)?

It depends! There are points in the Sound Map of the Danube album when I feel the strength of the water and it can be terrifying, but there are points where it’s not, where it’s peaceful. The thing I love about it is the way you weave in the sounds of people talking about the river.

Oh yeah, thank you.

Listening to those people helps me understand what the river means to them and I then consider all my personal associations with water, and it becomes this intermingling of different emotions. I wanted to ask—clearly you enjoy talking with people, can you recall for me a conversation that you had with a stranger that has stuck with you for a long time?

The question is, in a sense, too easily answered by memories of talking with the people along the Danube, especially because I’ve been listening to it again (laughter). I’ve also been looking at the Hudson lately. But one that was particularly poignant for me on the Danube was an elderly fisherman living in Kopačevo, who I think fished near the Kopački Rit—let me pull out the map because I don’t always trust my memory (laughs), I’ll be a moment (looks at map).

The fisherman was Janós Horvát, now where is he… I’m looking at the liner notes. (pause). Kopačevo, that’s right, and a very big, beautiful lake where I recorded a heronry and fish jumping and put his voice with that. He was very poignant because talking with him about what fishing had been like in the backchannels of the river, and how rich it had been—it had been very obvious, and he presented it really clearly, that the fishermen themselves had kept those channels clear. They had been giving back to the river even as they were taking from it. They kept the flow clear, kept the channels clear. Every year they would get together and had huge wooden—I don’t know what you would call them—like the scooping part of a bulldozer. They would drag those on ropes to clear weeds away and deepen the channel a little bit.

Then that area—they call the Auen, it’s the wetlands really, the backwaters—it became a national park. The channels and that particular area of wetlands became protected and the fisherman were kicked out, which was extremely hard for them of course. He was old enough that he couldn’t really start again—he lost his livelihood. What mattered just as much to him was the channels began to grow over and disappear, no one was clearing them. The clarity of reciprocity between the fisherman and the river—which had been an operation—and what had happened when it was dismantled… it was devastating to hear about.

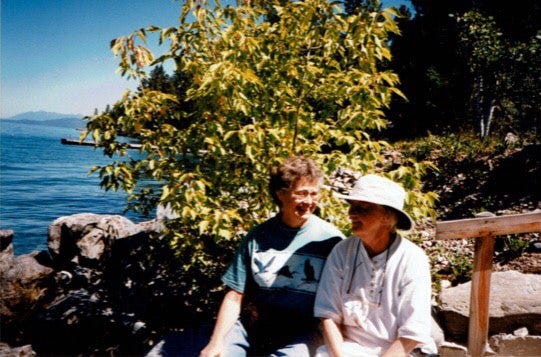

I can see myself and Ruth Anderson, who traveled with me—I can see her sitting at his table drinking something like Sprite (laughs). Or an orange drink, very sweet. And I had my mic and a little tripod stand on the table and he was just talking with us, getting more and more relaxed. He was a lovely person, very gentle. There were other poignant stories as I went along the river but that was particularly so.

You grew up in Christchurch—

New Zealand, that’s right.

What’s your earliest memory of spending time in the water, or being around water?

Oh, how powerful rivers are. My father was a lawyer but also, even more, a climber and ski mountaineer. And before meeting my mother he had bought a little cabin up in the Southern Alps along with friends who were setting up a ski resort. So of course as kids we spent summers and winter holidays up there—we had ski school—and we went climbing with my father. And from very early on, one of the things he would talk to us about was the power of the rivers, which are wild as they flow out of the mountains of course—they’re very strong. He talked about how you could never trust a river that looked serene. As you’re starting to cross one, rainfall further up would unleash a whole flood that would rush downstream very fast.

So he impressed us with that, with the strength of the rivers. Or at least I understood it ultimately as that they’re phenomena beyond our control, which I like a lot (laughs). I really like that. And then the little hut was by one of the rivers—the Bealey—and my brother and I would often go to sleep at night hearing kiwis calling across the river, which was a rare occurrence even back then in the ‘50s. And we didn’t often hear them but I was listening to the river in the process of trying to hear through it to the bush. I grew up listening closely to rivers and with a huge respect and interest in them.

My other impression of water is of the Pacific. How strong the riptides are. We would go swimming when my father quit work for the day and in the summer we would just drive down to the ocean near Christchurch and it was freezing. It was never not freezing. Was it freezing where you were as a kid?

(laughs). Yes, yes it was.

(sighs). Yea the Atlantic doesn’t seem nearly as cold, or at least around the areas I’ve encountered. But the Pacific (sighs) love that ocean, though.

You said that you’re drawn to how these bodies of water are beyond our control. How do you try to convey that when capturing the sounds you do?

I honestly don’t think I can answer that—I can’t use words to answer it. What I’m listening for when I sit down and start listening to a particular spot is how the river’s energy comes through. It can be that the whole river is clearly energized—moving fast and full of sound. Or it can just be that it comes up against rocks and circumnavigates them and creates these wonderful gurgles. I’m listening for the river’s energy—with the Danube, consciously, and with the Hudson without realizing it. I was recording not because it was commissioned, it was just something I wanted to do and Ruth said, “We can afford it, do it!” (laughs).

Anyway, it was something I wanted to do because I wanted to know what a river is and I don’t think I got at that with the Hudson. And I thought I could make better recordings than I made with the Hudson, and tackle it differently. With both I involved people but by the time I came to do the Danube, it became clear to me that humans are part of the riparian environment. And that the river creates that whole riparian environment, including the lives of the humans who depend on it and live near it. We ultimately have no more control of the river than the frogs or anything else which lives around the trees and plants. We’re just part of this ecology. I wanted the voices to be within the water sounds—not separate.

With the Hudson I had the voices at a separate station and you could choose to listen to them or not and that no longer seemed right—why should they be separate, you know? And besides, I keep trying to assert, as I get older, that we are not separate from these phenomena. We are beyond entangled, we are interdependent with them. I keep trying to find more and more ways of presenting that idea to people—presenting that reality—not an idea to my mind, it’s a reality.

In the interviews I’ve seen where you talk about Ruth, it’s evident that she inspired you a lot. Can you name one or two things that she helped you learn, be it in your compositional approach or about yourself as a person.

Oh! (laughs). Something that comes to mind immediately is how she had something she lived by which she applied to both of us: “We can do anything!” And it was so empowering and, sure enough, we went and built a house ourselves. I mean—we did! She was right! But now that she’s gone—she died near the end of November—I’m realizing more and more strongly (and this was something I had known but had not quite seen so clearly) is how much we mutually supported one another’s work. She would encourage me in every possible way. I doubt myself frequently and she would always counter that—she wasn’t having any! (laughs).

She stopped composing when she got chronic fatigue in the mid-’80s—it interfered with her ability to compose, I mean she got it really badly. She stopped composing with sound, but she didn’t stop making things. I would continually tell her, “You’re a composer!” And she would say, “No, not anymore.” And I would say “Once a composer, always a composer!” Which is true, of course (laughs). We gave each other a lot of support.

Something very beautiful is beginning to happen. It’s similar to what I’m doing in Chicago. In Austria, at the beginning of April, in Graz. We were putting together a concert program which includes some electroacoustic pieces and Gerhard Eckel, the composer who’s organizing it, asked if we’d like to include a piece by Ruth and I jumped at it! He had one already chosen and I was so pleased. And then I mentioned this to the SEAMUS organization in Charlottesville, which is having their annual conference in the middle of March, and they decided to program three of her pieces to be played back in a listening room. And finally I’m doing something in Berlin in July, and the woman organizing that festival also asked if I’d like to include a piece of Ruth’s. That’s really nice, I like it. I think Peter Margasak [curator of Frequency Festival] would have gone for it too but we were all set with the Chicago program long ago.

She also has her first solo album coming out at the end of the month. It’s on Arc Light, which is a UK label run by Jennifer Allan. Five of her pieces, two of which have never been released before—it’s thrilling. Her music is coming into people’s awareness again.

Can you share what you like about Ruth Anderson’s work?

Some of it is extremely funny (laughter). Have you heard any of it?

Yes I have.

Which ones have you heard?

I’ve heard “Dump” and “State of the Union Message.”

The latter really makes me laugh. And she was a very funny person, and very playful. And there are pieces which are sonic meditations in a way—”Points” and “I Come Out of Your Sleep.” “Points” is a sine tone piece. Pure sine tones, which are the devil to manage (laughter). Especially in analog, you know? Everything has to be so clean.

What I love about both of those pieces besides the fact they’re so acoustically rich—they’re great to listen to—is that they slow all the body rhythms I’m aware of. They slow me down to a state in which I’m just at peace. She intended that with them. She talks about unity with oneself so that you no longer have that little voice on your shoulder—you can let it go. She talks about the body being totally relaxed, totally open—she was very interested in sound and healing. We, with two other people, experimented with that for quite a while. And those two pieces just make me feel so at peace and so part of everything when I listen to them.

“I Come Out of Your Sleep” is actually a quad piece. She’s whispering the vowel sounds—she extracted the vowel sounds from a poem by Louise Bogan, an American poet, and it’s a haunting poem actually. She extracted the vowel sounds and whispered them. Being a flutist—(through laughter) she could use her voice. She whispered them and created a four-channel canon from them, and each one takes an entire breath to produce. Each vowel or combination of vowels takes a whole, slow breath—she had great breath control. It moves slowly and it becomes fuller and fuller, it’s just beautiful as it circles around the four speakers. How those pieces make me feel is one of the things I love about them, and I love her ideas.

The last piece she worked on she called, I think, “Furnishing the Yard” or “Furnishing the Garden”—I’m never quite sure. Probably “Yard” because she was a Westerner (laughter). On the day in which the garbage people would pick up your discarded furniture and so on, we would pick up discarded chairs and she would set them out in the garden at all sorts of angles and in all sorts of places just to fall apart, for the weather to work on, for the snow to work on, for the animals to work on—she would just leave them there. One of them is an old-fashioned chair for a kid who is about two, going on three—it’s about the right height for that. And she placed it partway up the trunk of a tulip tree in our backyard and it just sits there and the tree is putting out little branches which coil around it in the summer. Squirrels land on it (laughter). And everything just sits there, it’s a lovely piece with everything falling apart, disintegrating slowly.

Thanks for sharing all that, that was really nice.

Oh, you’re welcome.

Also in Chicago, you have a piece that you wrote with Nate Wooley that he’s performing called “Becoming Air.” What’s that piece about?

Ah, happy to talk about that. We did a rehearsal of it yesterday at ISSUE Project Room and it went beautifully. I came home on a cloud (sighs). Nate asked me for a piece for solo trumpet for his project that involved deepening the solo trumpet repertoire. It had never occurred to me to write for solo trumpet. I’d written a duo ages ago for trumpet and trombone but not solo trumpet. The idea seemed like a real challenge to me, not something I would have thought of, but I knew what an interesting composer and performer he is. So I went over to his place, which is pretty much how I start working with musicians on most commissions. We sat down and drank some tea and I asked him—he having sent me CDs in the interim and me having read his writings—I asked him what sounds he was exploring at the moment.

We discovered that we both are fascinated by the moment at which a sound you’re generating takes on properties you didn’t expect. My way of looking at it is that the sound takes over, it flips control. It’s not that you are no longer able to make it, it’s that you are no longer shaping the sound—it’s off in its own direction. I got into that with The Glass Concert and Nate’s always been into it. We had really good common ground.

I took Nate’s sounds and then I went off to Montana for the summer and began to figure out a progression from one type of sound to the next general type to the next and so on. I took it back to him and that was the underlying structure. It was a broad structure but I was pretty specific about which sounds of his that he’d given me that I was most interested in. Then we started working on it and he would take a sound and push it further and further and we came up with “Becoming Air.”

The tam-tam is there because I wanted to create a larger acoustic space around the trumpet. And I love tam-tams anyway (laughter). It seems to crop up in a lot of my pieces. But I felt as if I could create an acoustic shell of sound around the trumpet. We resisted ending with breath sounds for obvious reasons, we weren’t gonna do that (laughter).

He premiered it at ISSUE Project Room for a series of performances for newly commissioned trumpet works. That place has amazing acoustics so we were playing off the acoustics too. But it keeps growing, we keep refining it, he keeps finding new things, they find their way into it. The rehearsal yesterday was beautiful, it just flows. I was knocked out. He uses a thin piece of aluminum that he holds against the bell of the instrument and he just bought and cut a new piece. It was able to distinctively do things that the piece he had been using for a while couldn’t do. And we get wrapped up in that sort of thing; that new piece of aluminum makes the most amazing buzzing sounds, just gorgeous. That’s how that piece is—it continues to grow, we continue to do things. I love working that way.

Clearly you’ve traveled to a lot of places. Are there any particular cities that you’re most fond of, or would like to go back to? Do you mind sharing any of those and the memories you have associated with them?

I love San Francisco, and I love working there. I did a short residency at The Lab a couple years ago of which William Winant and Fred Frith did Jitterbug which was an astonishing performance (laughs). You can imagine, with those two. I’ve always loved the city, I like being by the Pacific. It reminds me of home and I have a number of friends there. Maggi Payne has been lending me one of her terrific hydrophones for years.

Two of my great memories of San Francisco are not of performances at all. They’re of Laetitia Sonami, Brenda Hutchinson, Maggi and myself all having dinner together. The first time we did this was about five or six years ago. And we had the best time! And we all know each other’s music well and love it so there’s a lot to build on. We loved it and we said we should do it again, so when I was at The Lab, we did it again!

This time we met at Laetitia’s house and—oh I love this—one of us, I’m not quite sure which, maybe it was Maggi, thought it would be a good idea if we recorded our conversation. So we sort of debated that a little and Maggi brought gear with her and set up and got everything just the way it needed to be. And Brenda said, “You can’t monitor it.” And for Maggi, the concept of recording without monitoring was unimaginable, but she didn’t! And we recorded our conversation so we could hear it back again—we sent the files around and we all have them. We mutually decided that this was not for broadcast and that it was a private event, it’s a private file. That’s one of my fondest memories of San Francisco.

But I first went there years and years ago. I think I was first in San Francisco in 1972 and I think that was when Charles Amirkhanian decided that Pauline Oliveros and I, who had been communicating for a long time by then but had never physically met, should physically meet. So he had us both on one of his shows on KPFA-FM and that was amazing. It’s archived now and online somewhere or other. I’ve been going back and forth to San Francisco for a number of years now with such pleasure.

What about that interaction with Pauline was amazing for you?

Because our communications had been so open-hearted—we shared a lot—it was just amazing to see the expressions on her face, to hear her voice and her intonations shifting, things she responded to, things that I responded to. It was deeply enlivening to just be in the same space communicating with each other so strongly. It was great. And then she became an influence on my life (laughter). It was Pauline who suggested to Ruth that Ruth hire me—Pauline knew I wanted to come over here and be working. Ruth needed a substitute to teach in her electronic music studio at Hunter [College] while she took a sabbatical. She wanted someone who would not be incompatible with the way she was running it so Pauline suggested me and that got me over to the States.

Years afterward, in the early 2000s, Pauline and Ione married in Canada. They said, “You should think about it.” (laughter). So in 2005, Ruth and I drove up from where we were in Montana, about three hours north above the Canadian border and we got married in Cranbrook. I used to tell Pauline that she changed my life and she would never take responsibility for it.

You stated how you kept in contact with Pauline and it had been quite a while until you had actually seen her face to face. Was this something that was true of you and other musicians you kept in contact with?

Not so much so because when I was living in London, where I was for a long time, I was interested in the American new music scene anyway and American musicians—the Sonic Arts Union people, Charlotte Moorman and Nam June Paik, David Rosenboom and a whole bunch of other people—would keep coming through London and doing performances and I would get to meet them. Pauline was really the one person who stands out to me who I didn’t get to meet before I came over here, or at least when I came on that ‘72 visit—I moved here in ‘73.

I’d been lucky to have met so many American new music people while I had been in London, and when I came over here there was such a vibrant community in and around New York. It was so welcoming and generous. All of a sudden there were all sorts of invitations to make new work and present at this gallery and at this loft and so on. It was amazing and wonderful, the generosity of that scene is still really impressive and beautiful. There was a community here and I became part of it, little by little.

Do you still feel like that community exists today?

(laughs). Oh yeah, absolutely.

Obviously you make new work still, but what does a typical day look like for you?

Two cups of coffee and the New York Times (laughter). Scare the squirrels away from the bird food for a while (laughter). I’m laughing but that’s really what this morning started like. And now at the moment I’m working on three talks—for Chicago and Graz and Charlottesville—which I’m trying to keep straight, one from another. I’m also organizing sound clips. That’s not an untypical day. Sometimes I go straight from the New York Times to email, sometimes I put email off for a few hours and then tackle it. If I’m working on a piece down in the studio then I’ll get up, have breakfast, I would have chatted with Ruth, sorted out the day, and then worked for four or five hours straight. But that would be as much as my brain would do. I’d come upstairs and do officework—emails and arrangements and organizational stuff.

I used to work all night. The last few years I had been quitting work at five o’clock so that Ruth and I had from then on to be together, to do things together. She was losing vision so I would read her the paper. Make dinner, relax—things like that.

Annea Lockwood and Ruth Anderson approximately four years ago at their home in Flathead Lake, Montana. Photo courtesy of Lockwood.

What are some things that you and Ruth would do to relax?

Just sitting together with not-particularly-consequential conversation coming and going. Something which really was nice was reading together, either aloud or alone together. Or listening to music of course. Or just sitting out on the deck. In Montana it’s so easy, we would just walk out onto our deck and the house we built is 14 feet away from a lakeshore so it’s right there. It’s near Glacier Park. We would just go out on our deck and see the light changing on the lake and it’s constantly shifting, and the lake’s surface is constantly changing. It’s a big lake so weather systems would move across the lake and we’d watch them come and go and come and go. We’d track the bird life—just be in that environment, you know?

I’ll conclude with a final question: What do you want for listeners to take from your work? And has what you wanted listeners to take away from your work changed throughout the years?

I think it has changed, but it’s not so much that it’s changed as it has broadened. Or that I’ve been able to focus more and express verbally what I was aiming for. When I look back to “Tiger Balm” from 1970, it’s very clear to me—and I knew it already from working on programs for the BBC—how interested I was, and how important it was becoming for me, to learn and take into account how people’s bodies respond to sound. That, in addition to my childhood, made me interested in the rivers.

I got more and more interested in traditions in which the sounds and the environment of rivers are healing. I perked up and started recording rivers and that led me into seeing and sensing how rivers create their environments and how we are intertwined with rivers, and then I get to where I am now. Where the sound and the phenomena around us—if we’re able to let those sounds flow through our bodies—they become conduits of connection through which one feels a part of that phenomena, deeply integrated with it. We can recognize how deeply integrated we are with everything that’s around us. And with that, conservation flows and it’s all just one unfolding train of thought, really, and it just got clearer as I got older. Is that making sense?

Oh yes that makes total sense. I forgot that I wanted to ask this: do you have any book recommendations?

Oooh—Donna Haraway. Liz Phillips, a very good friend with whom I’m working at the moment, she and her husband Earl Howard put a book of Donna Haraway’s into my hand and I started reading it a year ago. It rang all sorts of bells and enlightened me in all sorts of ways. Staying with the Trouble is the title. That became a real influence, and I just started reading Enlivenment: Toward a Poetics for the Anthropocene by Andreas Weber. Plus a few thrillers here and there. Plus I picked up a book on the Rhine by somebody called Ben Coates. It’s a traveling-down-the-Rhine book, and I’m always curious how people experience those sorts of journeys, of course.

Annea Lockwood’s Tiger Balm / Amazonia Dreaming / Immersion is out now on Black Truffle. Ruth Anderson’s Here is out now on Arc Light Editions.

Download Corner

Every issue, Tone Glow provides download links to older, obscure albums that we believe deserve highlighting. Each download will be accompanied by a brief description of the album. Artists and labels can contact Tone Glow if you would like to see download links removed.

Ruth Anderson / Annea Lockwood – Dump / State Of The Union Message / Tiger Balm (Opus One, 1982?)

Ruth Anderson’s two pieces here are a real delight. “Dump” (1970) is a kaleidoscopic electronic swirl of pop-sampling sound collage. There’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “What the World Needs Now Is Love” and “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” among others. The piece was projected from speakers hanging from trees, soundtracking an event titled “Dump Works” wherein people could walk around a garden filled with various, discarded objects Anderson found in the East Hampton dump. There’s a real sense of dirt and grime to the squiggling electronics, which naturally paints the songs in a different, slightly grim light. You can imagine how fun it’d be to have been at the event (the liner notes state that the garden, among other things, had a pile of bones).

“SUM (State Of The Union Message)” (1974) is another collage work, this time featuring bits from commercials that are sequenced one after another, their juxtapositions often proving humorous. The different musical components and excerpts of people talking grant the piece both a liveliness and a bit of anxiety: one gets the sense that the piece is never going to stop: oh the tyranny of advertising. For whatever reason, “SUM” is an early plunderphonics touchstone that’s not mentioned nearly enough.

“Tiger Balm” people likely know, especially given the recent Black Truffle reissue. It’s defined by the mesmerizing sound of purring (the animal belonging to Carolee Schneemann) as a means of getting into a meditative state, coupled with a plethora of other sounds—gamelan-like bells, heart beats, mouth harps, a woman moaning. There’s a narrative formed in the sequential coupling of sounds: that of the unity between human and nature and music. There’s these rhythmic patterns that appear in every sound source, implying the sort of interconnectedness one can find when listening closely. Really, though, it’s a testament to Lockwood’s compositional prowess: the arrangement is the glue that holds everything together, and it brings you into Lockwood’s own perception of the world and what music can do. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Note: there’s a heavy amount of surface noise on all tracks, but especially “Tiger Balm.” My apologies; I have no time to clean LPs and declick right now.

Ruth Anderson’s Here is out now on Arc Light Editions.

Maggi Payne - The Extended Flute (Composers Recordings Inc., 1999)

A lot to love on these eight tracks, one of which is the diversity in the compositions, of which Maggi Payne’s are especially delightful. “Hum” is a hypnotic vortex of extended techniques on the flute. At first it sounds like you’re in a wind tunnel, but discernible notes soon appear—the tones so sharp and crisp—vacillating between flutters and piercing drones. The end of the track has the sound of her blowing, leading into a massive recording of an ocean and winds. Hearing these sounds overlap makes one consider the power of nature, and how music should have the same effect on the listener (in other words, one should treat music as being capable of a similar feat). “Aeolian Confluence” drives that idea right into the listener’s skull through sheer force of volume. It’s relentless, and frankly terrifying.

Otherwise, it’s the Behrman collaborations that are particularly special. The mixing of electronics with flute allows for an intertwining and compounding peculiarity; the sounds from both Payne’s flute and Behrman’s electronics are curious on their own, but their merging makes for something almost sci-fi in atmosphere. Elsewhere, “Flaptics” contains Payne’s breaths and quasi-vocalizing finding a spirited and cheery match in Mark Trayle’s whirring electronics. There’s 75 minutes of flute-centric music here, but Payne never let’s you feel like she’s out of ideas. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Nate Wooley – Trumpet/Amplifier (Smeraldina-Rima, 2010)

Playful extended technique business: “Trumpet A” is all squirming and fettered blows, flatulence-like in both its sonics and humor. (Don’t worry, it’s still serious stuff, duh). There’s squeaks and squeals, all spurting out at unexpected moments. It’s minimal enough that the negative space can be appreciated for how it allows Wooley’s playing to feel both alien and intimate. Charming moments abound: in the second half, Wooley sounds like 1) he’s firing laser beams, 2) gusts of wind are blowing, and 3) a cartoon character is nosediving off a cliff. “Trumpet B” is more clamorous, slightly more dense. You feel the power of the trumpet there, the force of Wooley’s breath. “Amplifier” is the most hardcore, with noisy feedback and high-pitched tones and Wooley’s trumpet in full “yea we’re here to fuck up some shit” mode. That track is 20 minutes of fiery improvisation, albeit with a sensibly contained, bottled-up energy that’s sustained throughout. There’s drama and drones and a need for some Dramamine (if you surrender yourself to the music, that is). If you let it consume you it’s a lot more fun. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Download links: FLAC | MP3

Purchase link: Bandcamp

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

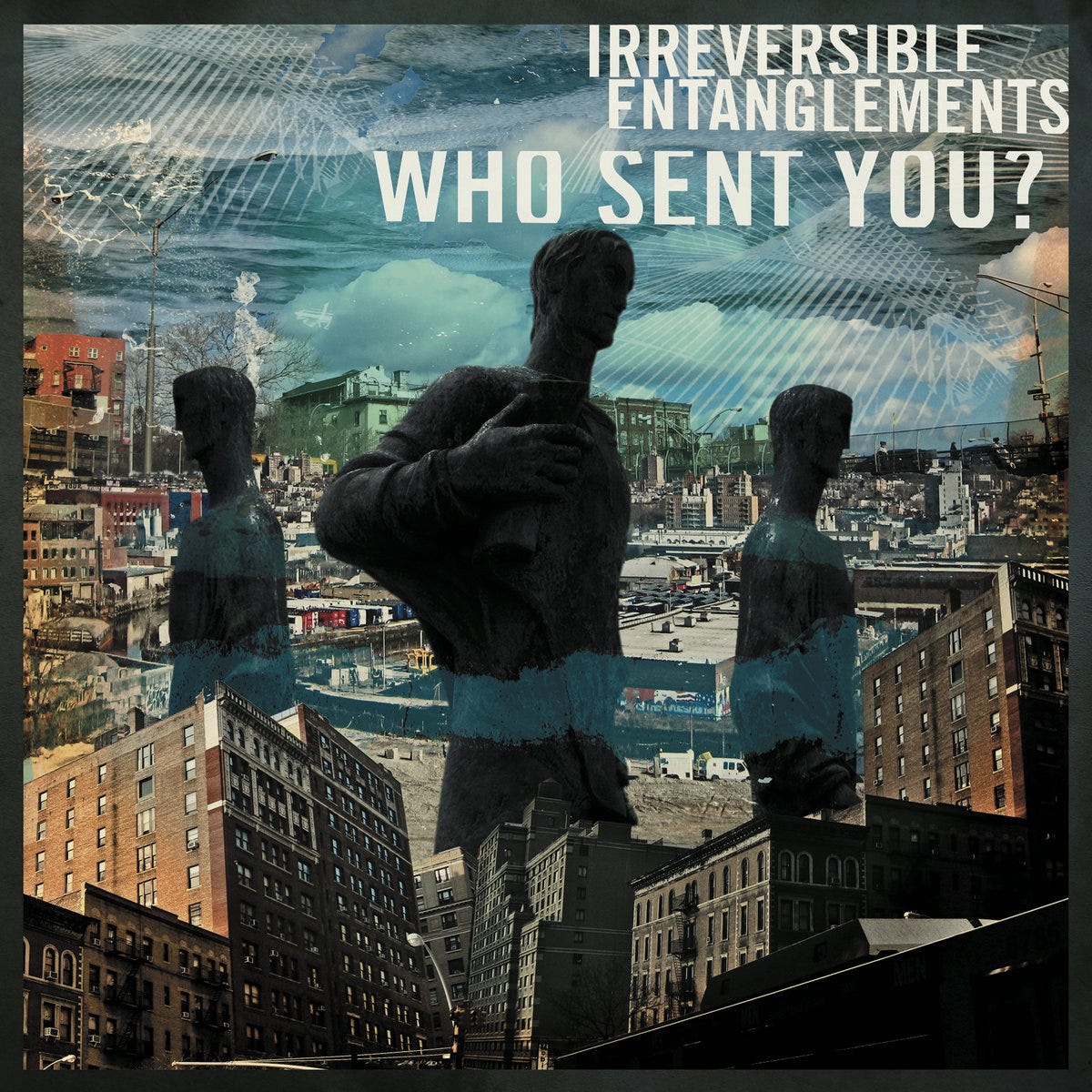

Irreversible Entanglements - Who Sent You? (International Anthem/Don Giovanni, 2020)

Press Release info: Who Sent You? is the punk-rocking of jazz and the mystification of the avant-garde, a sci-fi sound from that out-soul-fire jazz quintet Irreversible Entanglements. Who Sent You? they asked and tried to lock us in their distress chambers, and yet here it is: an album that functions as a heat-sealed care package for the modern Afrofuturist’s pre-flight machinations. This record weaves kinetic soul fusion, dreamy yet harrowing spectral poetry, and intricate force-field-tight rhythms into wild, warmth-giving tapestries that comfort and conceal, confront and coerce all at once, with the dark matter of the deep, black all-consuming universe as its thread.

Where the band’s self-titled debut was all explosive noisy anthems and glorious cosmic bluster, Who Sent You? is a focused and patient ritual. Irreversible Entanglements take their time in between these grooves, stalking the war-torn streets of the Deep South and post-Columbian apocalypses—taking their time to add our DNA to the centrifuge, to dream up an alchemical amalgamation that sounds truly euphoric, drenched in the epic star-flung fallout of a nova only they can conjure. More than the sum of its parts—Luke Stewart’s war-like basslines, Keir Neuringer’s haunting saxophone, Aquiles Navarro’s cyberpunk brass, the unwieldy storm of Tcheser Holmes’ drums, and the oracular phyletic incantations of Camae Ayewa—Who Sent You? is an entire holistic jam of “infinite possibilities coming back around,” a sprawling meditation for afro-cosmonauts, a reminder of the forms and traumas of the past, and the shape and vision of Afrotopian sounds to come.

You can purchase Who Sent You? on Bandcamp or on the Don Giovanni website.

Samuel McLemore: Much modern jazz can feel like it’s playing a game of Pierre Menard—every musician trying as strenuously as possible to sound like they’re recording an album from 60 years ago rather than right now. Jazz as a genre and as a cultural force faltered in the leap from the 1960s to the 1970s, and those who try to keep the flames alive run the risk of paradoxically choking out innovation. But, on the other hand, who said the music had to change so much? Jazz musicians of the 1960s made their music in the context of a decade of turmoil of every type imaginable: War all over the globe; endless struggle for the recognition of basic civil rights for all; MLK and Malcom X assassinated while Nixon is elected; every possible grouping and subgrouping of humanity at the other’s throats; in politics a booming but chaotic progressive movement grows and collapses while conservative and liberal factions grapple over political power, with the conservatives winning handily.

What has changed in the years since that would cause musicians to react differently? The sort of traditionalist approach to free jazz that Irreversible Entanglements operates in runs the risk of being accused of hypocrisy by philistines, but it mostly serves to illustrate the fundamental durability of jazz as an art form and style. Jazz has always thrived in times of political strife, as a locus for—and celebration of—Black artistic activity, and in times like these what could we need more than that?

[6]

Jeff Brown: Who Sent You? features a timeless sound, with instrumentation and a sociopolitical theme that can be traced back to artists such as Albert Ayler, Sun Ra and Pharoah Sanders. There’s five free-jazz excursions driven by upright bass, saxophone and trumpet that leave room for Camae Ayewa’s spoken word. She is blunt and direct whether asking questions of authority on the track “Who Sent You – Ritual” or holding a mirror to religion on “Blues Ideology” with a repeated theme of “The Pope must be drunk.” Not mere backup players, the ensemble lays down on “No Más”: dueling horn melodies, wild drum fills, and bass with walking lines holding it all together. The overall feel is a live sound that doesn’t appear overproduced with effects or microphone techniques. The freer tempo and the dynamics—hard drums hits and loud horns—accentuate a nervous tension that echos the poetry of neighborhoods dealing with aggressive police presence throughout the decades. Music as energetic as this, coupled with such powerful words which inspire the listener to speak truth to power (as was the case with the aforementioned artists), will always be relevant.

[8]

Raphael Helfand: For Afrofuturists, Irreversible Entanglements are surprisingly rooted in modern Planet Earth. They are a quintet, not an Arkestra. They use no electronic instrumentation. Their sound is deceptively conventional upon first listen. Even their lyrics, penned and performed by Carmae Ayewa (Moor Mother), speak of issues happening in America right now—not underwater, outer space or in the next millennium.

“Who Sent You,” the album’s eponymous centerpiece, alternates between hypnotic grooves—built on Luke Stewart’s double bass and Tcheser Holmes’s drumming, augmented by Keir Neuringer’s Dolphy-esque sax and Aquiles Navarro’s thoughtful, lightly-affected trumpet—and full-band freak-outs a la Sun Ra, though Irreversible Entanglements’s sonic orgies feel much more contained. Ayewa speaks directly to a police officer. “What are you doing in my home, in my neighborhood? Who sent you?” she asks, her voice growing gradually louder and more fraught as the 14-minute track elapses. “You must be here to make sure our kids get home from school safe,” she reasons, with the chilling knowledge that the cop is there for something much more insidious.

As the band slips in and out of standard time signatures, between control and chaos, their universe expands and contracts, blurring and sliding suddenly into focus. Their sound may not be revolutionary on the surface, but once you let yourself fall into the world they’ve created, there is no turning back. Irreversible Entanglements make subtle protest music: Their call to action is not direct, nor is it astral. It exists in the here and now, an undaunted document of Black experience—a time capsule, perhaps, for generations to come.

[8]

Jesse Locke: Irreversible Entanglements’s 2017 debut was a ferocious blast of contemporary fire music. The quintet led by poet/MC Camae Ayewa (aka Moor Mother) delivered a searing indictment of police brutality and racial violence against black communities set against a riveting instrumental backdrop. After returning with the 23-minute piece “Homeless/Global” late last year, they’re back with their second album from International Anthem and Don Giovanni, still sounding absolutely vital. The group barely stops cooking throughout, outside of a few placid passages of sparse percussion and agogo bells on “Who Sent You – Ritual” that only serve to ratchet up the tension. “No Más” settles into the album’s standout groove, while Ayewa sounds especially pissed off on “Blues Ideology” with an all time great opening lyric: “The pope must be drunk.” Bassist Luke Stewart deserves some special credit here for his frenetic, non-stop playing on the album’s five songs. If you’re a free-jazz fan somehow still sleeping on Irreversible Entanglements, get up with it.

[9]

Sunik Kim: Irreversible Entanglements make “protest music” where the music is primary, but is resolutely grounded in political realities and struggles: the group came together through Books Through Bars (an organization that sends books to incarcerated people in the mid-Atlantic region) and a Musicians Against Police Brutality event held in 2015 in response to the murder of Akai Gurley. In a refreshing 2017 interview, saxophonist Keir Neuringer and bassist Luke Stewart stress the importance of thinking beyond “protest music”—which they argue often (and I agree) leads to didactic “agitprop”—and having political “commitments off stage.” Though on Who Sent You? poet Camae Ayewa (aka Moor Mother) addresses these political realities head on in the vein of much “agitprop” protest music, her language—much like that of forerunner Amiri Baraka—simultaneously abstracts these realities and sharpens them: it’s the difference between Zack de la Rocha yelling, “Motherfuck Uncle Sam,” and Ayewa asking, “Who sent you?”

Where Baraka, on albums like It's Nation Time, strives for the ecstatic—the vocal equivalent of a late-era John Coltrane solo at its peak—Ayewa gives her words more room to breathe, allowing the band to finish her sentences. Though Ornette Coleman’s Science Fiction is the obvious touchstone here—especially its titular spoken piece—I hear more of Coleman’s Crisis, both in its more apparent political leanings (“Song for Ché”) and its muted, thrumming sound. The subtle delay on Aquiles Navarro’s trumpet recalls Miles Davis’s smoked-out late live albums (Dark Magus, Agharta, etc.), though the effect here is sobering rather than hallucinatory. While I often enjoy the freer end of the jazz spectrum for its ability to embody pure but directed energy (versus the aimless, often clownish “noodling for its own sake” that characterizes much European free jazz), and initially felt a little impatient with the slower burn of Who Sent You?, ultimately its utter confidence and deliberation won me over. A few sections, especially the sparser ones with less presence from Stewart and drummer Tcheser Holmes, dragged on a touch too long and temporarily lifted the spell—like the lights coming on before the film is over—but that largely didn’t detract from the power of this collective incantation.

[7]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: “Who sent you?” is the primary question asked, and it’s one that permeates the album. Who brought such terror upon us? Given the quickness with which people have been compliant and content with increased police presence, with martial law—viewing it as necessary in times of a harrowing pandemic—the need for an album that stands in opposition is clearer than ever. These tracks swirl and push back, relentlessly forcing listeners to wrestle with prevailing ideologies. There’s a restlessness to these songs because there can only be restlessness. Our ongoing panic must be met with a response that’s of equal urgency. And Irreversible Entanglements provide that—amidst all the clamor is a knowing purpose and a call to action. Even more than jazz heroes of old, I keep coming back to “How We Gonna Make the Black Nation Rise?” The answer to the titular question is simple: “We gotta agitate, educate and organize!” There’s no better soundtrack to such a process—to these crucial times—than Who Sent You?

[7]

Oskari Tuure: In Northern Europe, where I live, the population demographics have historically been very homogenous. We’re only recently starting to ask ourselves the question of what issues racial minorities face in our society, and it’s not an easy question to tackle, especially for a country that has never seriously stopped to consider what the answer might be. Listening to Who Sent You? reminds me of reading American news about racially motivated violence, or about the many ways institutional racism might manifest: the issues feel distant and something that I figure the United States should have sorted out decades ago–but they haven't, and neither have we.

I’m not necessarily someone who enjoys overtly political art, but the politics of Who Sent You? are so deeply embedded into the work that it transcends the apparent burden of its themes. It’s not just an album with political overtones, it’s a political statement. There’s an undeniable flame of passion that can be found in the performance of all musicians and the words of poet-narrator Moor Mother; she especially sounds like someone who has had enough of waiting for injustices to correct themselves. Her poetry serves as a rallying cry that makes me want to find that same fire inside me: the fire of change, of emancipation, of making people’s lives better.

[7]

Leah B. Levinson: Because I was gazing at Bridget Rileys, I counted repetitions. Because I drove myself away, sightly lines moved slightly. Something to look up to, I couldn’t figure, displaced though even, they were always on and on. Do it enough times and it starts to come clearer. Then, because I was only lonely, I couldn’t wait to hear her—each word, Moor Mother, speaking across the din. She sounds so truly lively, speaking quietly, you know. And it’s because the bass was steady that the drums could be much freer; then, because the earth was moving fast, I knew I was imposing.

Because I worried where we’d be, I looked a little further. I felt the slightest pressure, beneath my second bosom: a pulse, learning, counting over, losing repetitions. Who am I to say how oft the bar starts over? Time can only hold so many moments holding over. Because the weather was a shuffle, I tapped myself away. Because the horse was on its back I knew the setting sun. My power, so little, so joyfully sniffing targets, curious, errant in its moving, emerging from the texture.

Because “[the] effect is that of a shifting, modulated light, shimmering through an organic structure.” (13). And all else is still until you look more closely. How time folds upon itself, enveloping, enclosing, concealing what it holds. How the past is quite forgotten, held and hidden but there, calling, quietly implodes. Because the past is weighted, we’d like to leave it so. I wrote myself twice backwards believing it was so. Nothing new under the sun, I knew it must be so. Because I knew the river ran, I knew it to be so. I chose to step back in. I let the tide grow up, in, around me. If looking to reanimate, then only look no further. If doing is the issue, I’d like to step outside, engaged and forward-pushing, moving this world onward, sustainable in my future, I’d like to go outside.

[8]

Average: [7.50]

Thank you for reading the eighth issue of Tone Glow. We hope you’re staying safe and well during these times.