Tune Glue 018: Alan Palomo (fka Neon Indian)

An interview with the pop musician about drawing from Italo Disco and Boogie and City Pop, Leonard Cohen's humor, and his new album 'World of Hassle'

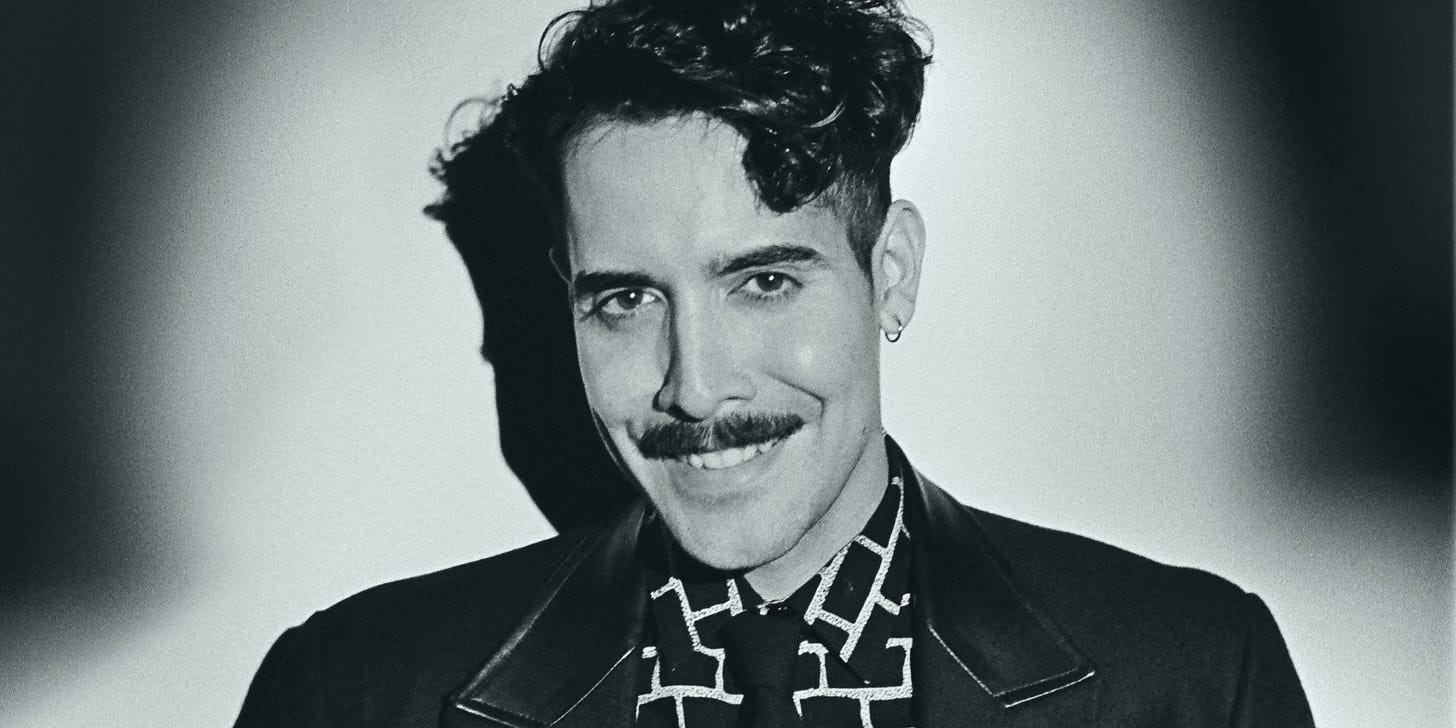

Alan Palomo

Alan Palomo (fka Neon Indian) is a Los Angeles-based musician originally from Denton, Texas. He released Psychic Chasms on Lefse in 2009 to critical acclaim, becoming known as a pioneer of the microgenre known as chillwave. He followed it up with his sophomore album Era Extraña in 2011, and then Vega Intl. Night School in 2015. His forthcoming LP World of Hassle, out September 15th, is the first to be released under his own name. Eli Schoop caught up with the blog-era legend on August 29th, 2023 to discuss his long-awaited return, ’80s Brazilian boogie, Takeshi Kitano, and Leonard Cohen’s zaddy vibes.

Eli Schoop: I was wondering earlier this year “...where did Alan Palomo go?” ’cause I loved Vega Intl. Night School and I was 19 when that came out, and I’m 26 going on 27 now. Why’d you decide this is the time to return?

Alan Palomo: Dude it’s so funny, the first record took like a month to make. That’ll never happen again. Y’know what they say, “you’ve got your whole life to make that first record,” so by the time I sat down I had so much material for it. Then the second took 18 months, and the third took 4 years and then now this one was an 8-year gap so I’m thinking, fuck, is there gonna be a 16-year gap before the next record? I don’t think that’s the case, I was actually working on what I thought would be the fourth Neon Indian album in 2017-2018, and I got a little burnt out on it. There was also a lot of touring mashed up between so I never really got a good chance to sit down and properly get to the bottom of it. I had it in my head that me and my brother were going to do a psychedelic, cumbia, chicha kind of record, and we got a few songs in the bag but it wasn’t enough for a record and there wasn’t enough material all around to really feel like it was time to deliver it.

So, coming back from the tour and having lost the thread, I was like, “Wait, we were working on this four months ago, what I was doing?” And as we were trying to go back, get back to that state of mind, the pandemic started and deadlines suddenly disappeared. I just decided to shelf that record for the time being, like maybe I’ll come back to it when I feel ready to approach the material again. But in the interim, what I did was I bought a piano and taught myself to sight-read, that was my little pandemic project.

When I put the band together for Vega, that was around the time my brother joined. He’s such a Berkelee jazz shredder that I had to get people to speak his language musically, ’cause obviously he’s going to have a lot of opinions about it. I was lucky enough in Denton to have got these players, and that was Max Townsley and Drew Erickson, and suddenly I realized I was the least technically adept person in my band. Obviously they can’t fire me ’cause I write the songs but it just lit a fire under my ass to start upping my chops, and the irony is that when you do music professionally, you write so little because as soon as you make a record, you gotta go on the road, y’know? You never get time back in the lab to develop new skills and tools. I kinda used the time in the pandemic to go back to that and to get into a more formal mindset about it.

When you produce music, you’re in such denial that you’re a musician for so long like, “No no nah, I’m not a musician I’m a producer, an ‘electronic music producer.’” I see a lot of friends who fall into that trap that after a while, you will hit a wall where your hands can’t keep up with your ideas and where you wanna progress musically. You don’t have the vocabulary for it, you don’t have the skillset for it, you don’t have a natural ear for it. My brother would say it all the time, like, “You have a great ear for tension chords,” but I didn’t know what that meant. So suddenly, I started putting a name to all these things that I intuitively would do, and then, being able to actually implement them at will was such a revelation. That’s when World of Hassle came together. I was listening to Bobby Caldwell and a bunch of city pop stuff and you see these lines between disco and the influence of more fusion-y stuff like Steely Dan, and then the Japanese sorta perfected it. You get records like Hiroshi Sato’s Awakening and so many other amazing records from that era, and I felt motivated to flirt with the jazz side of it and intentionally incorporate it into my music.

You put out that Italo Disco mix during the pandemic, you have a song in Spanish and French, and you’re saying you’re introduced to the Japanese side. You’re kinda a connoisseur going for the sophisti-pop route with World of Hassle. There’s so much revivalism where people only take from the mainstream ’80s stuff but I feel you’re doing it all across the globe, was that your intention?

It’s funny ’cause in my head I was like, “Are you finally gonna step into the ’90s? Should we buy a bucket hat and wear a tight tank-top and do electronica?”

I could see that.

It could be a vibe. Some people might criticize that I’m still influenced by stuff in the ’80s, but to me, once I think I’ve discovered one facet of it or one piece of what pop culture was doing in a part of the world, it opens up this pathway to another place. It’s less about the decade and more about the approach to music, the equipment, and I do think that boogie and funk really went to these strange new places in that decade. So you can progress musically and still be drawing more information from that well. I think that, yeah, Italo Disco was always my thing, even on the first record I was sampling stuff like La Bionda, and as that progressed that sort of evolved into a greater appreciation for disco. And as the years went on from that, y’know, France had their own take on disco, Brazil big-time had their own take, and on boogie in particular.

So you start kind of expanding your love for music, I think that’s kinda my thing. I think like a lot of people during the pandemic, I was trying to buy happiness on Discogs and going down these rabbit holes and one of them was Brazilian boogie. I got really into this producer Lincoln Olivetti who was kinda like the “hit doctor” in his time, sort of like the Brazilian Moroder and they would go to him when they needed a hit. He would produce records for Tim Maia, Rosana, Rita Lee from Os Mutantes, and that Marcos Valle record that everybody loves, that you hear at every brunch. I love those kinds of dorky stories of the guy behind all those records and there's a reason why all the records he blessed with that production had a specific style.

I could just keep doing circles around that, it’s not necessarily about chasing a trend of like, “Well we did the ’80s so let’s do the ’90s,” and then obviously the ’90s have their expiration date on it and we’re starting to explore the 2000s, like, indie sleaze aesthetics. So it’s been interesting to do my first cycle of it. I was in denial that it would ever happen. Like, I’m 35, obviously I got an early start, I was 20 when I did that first record. But there is that inevitability to it rather than chasing editorial trends. I kinda like that with streaming, editorial is slowly kinda dying and we’re just in this soup of “you like what you like” and you don’t have to sound like anything in particular, y’know?

Yeah, despite you going from chillwave to all the way now, over almost 15 years at this point, you have every single vantage point. Like you’re slightly older but in between Gen X and the Zoomers coming in now. I think you have a better pop ear than everyone who listens to ’80s and ’90s pop and tries to make something “retro.”

Totally, that’s the thing. I think there’s so many gems that you can learn from and I think a long time ago my buddy told me about the “10% rule” with genre where there’s the top, the crème de la crème, the stuff that gets noticed and canonized, and then by the time you’re in that outer ring it fizzles out, it’s total garbage examples of that kind of music. And Italo’s got plenty of that, there’s so much bad Italo. So it’s humbling to be like, regardless of what your interests are, there’s always gonna be good and bad examples of it. Just ’cause you write a certain style of music doesn’t automatically give it the label of “good,” and that’s just a subjective thing anyway.

But maybe it was just the spirit I started with music with the chillwave label on it, that a lot of it was this internet kind of pearl-diving, and I think because that integrated itself with how I made music in the beginning when I was still sampling stuff, eventually, the samples are gone but the diving’s still there. You’re still hunting for stuff that’s influencing you, and in that way, I mean “postmodern” is such a loaded word, like Tarantino makes movies about making movies and he doesn’t mind breaking out of the form and having a voiceover that lets you know you’re watching a movie. When I started making music I was really influenced by the Avalanches and Madlib, these kinds of collage records, but I think that element and influence is still there even if I’m not necessarily chopping up samples. I’m still going through my record collection for little gems to drop from it, things to take inspiration from, because, hey, if you’re gonna steal, steal obscure and steal from a lot.

There’s a really great book called Steal Like an Artist and y’know, there’s nothing new under the sun. I mean, there’s new personalities, and I find that music is becoming more and more personality-driven, and that obviously has a lot to do with social media, but I think as far as creativity and where ideas for songs come from, like, creativity doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Everything’s always standing on the shoulders of something else so rather than taking from one thing, take from 5 or 6 things and put them all in the same song. By the time you’re done it’ll be unrecognizable to any of those individual things. That’s always been my thing but you’ve gotta be a crate digger to do that, you gotta be looking for stuff, y’know?

Yeah that’s what’s so impressive about younger kids that started on all these Discords and from Twitter and stuff ’cause they really take from disparate places and make something new, and they’re all insane on Ableton or FruityLoops or whatever they use—

(laughs).

Like you’re 17 bro! But I think it’s cool they’re coming up as you did, as they work backwards, and then, as they’re coming up, are like, “Oh I’m gonna make rock now,” or something more straightforwardly influenced by shoegaze or Deftones or something like that. It’ll be exciting to see where that goes.

I think that’s the parallel man, like Ableton was the great equalizer, at least when I started using it back in the day. To me, chillwave… there was a certain inevitability you’d have where people who, on the one hand, were listening to indie sleaze or bloghouse from that time and were curious about getting into electronic music, but then eventually wanting to merge it with their love of stuff with the other side of indie—John Maus, Ariel Pink, all this lo-fi stuff, Panda Bear. In my case there was J Dilla and Madlib and stuff like that.

Suddenly you didn’t have to buy an MPC, you could just crack a copy of Ableton and start dropping mp3s that you pulled from a YouTube channel. It made it easy, but, if you had an ear for music, you could start manipulating stuff, messing with it, learning as you go. But then you get to that point where if you wanna sound like the thing you’re sampling you have to pick up an instrument and learn. It’s that reverse engineering that’s happening now—it happened to me! It’s just the natural progression of wanting to learn more about the thing you’re doing. In the beginning, some people had this kind of attitude going into it. “Well, I don’t wanna learn more ’cause I don’t wanna ‘taint the gifts’” and that is a romantic way to look at it, but you will exhaust the possibilities of that after a while. And it’s like: “Sorry bro, you tested positive for musician, it’s time to pick up an instrument and practice!”

It’s terminal, it’s fatal, unfortunately.

Yeah, yeah.

Vega Intl. is almost like a Michael Mann movie to me, like dark, noir pop. Whereas this record is more like a comedy and I can hear Paddy McAloon, early Talk Talk. Not just ’cause there are lyrics but you definitely have those chops. I think it’s definitely your funniest record and I was wondering if you had that mindset going in?

Y’know I learned something on Vega where, if something is missing in a song, the thing that’s missing is myself. I’ll try to make something that feels serious or wants to be taken seriously, but with Vega I was like, “Dude if you’re not having fun making it just go back to school and do something else.” ’Cause the second record is the only record I’ve ever made “under the gun” and I didn’t like that experience. I got what I wanted out of it, but there’s always gonna be 20% of that record that I hear at a restaurant and am like, “Dude if that mix sounded weird 10 years ago when I delivered it, lo and behold, it still sounds fuckin weird!” So I try not to do that anymore and really only deliver it when it feels right and it feels correct.

But with this one in particular I think during the pandemic you kind of just threw your hands up–like my friends and I have a text chat and a pretty demented sense of humor, but we realized it was a coping mechanism for just how messed up the world is slowly becoming. That element is always there. I take the process of making music seriously but not the product. And one big thing that was on my mind was that for some reason I’d missed–I mean I’d listened to Leonard Cohen in college but I’d never heard his later ’80s stuff–I just ran across I’m Your Man. That whole album and just him in the black suit, total Jewish zaddy vibes, grown-ass man. And he’s discovered his sense of humor or at least finally showcasing it. Everyone’s like “dude since when are you funny?” and he’s like “I’ve always been funny, I just never put it in my music.” That was so liberating. The lyrics are so smart but they’re also so ham-and-cheese and really lean into the self-parody aspect of it.

If I was to do the ’80s sophisti-pop, male frontman rock cliché, “I’m quitting my band and making a jazz record!”–if I was to do it, I also had to make fun of it. So that was kinda where that came from, but also with Neon Indian, you hear the production, they’re very textural records–I kept asking myself, “Well they know you can do that, what have they not heard you do yet?” And I realized it was really putting your vocals in the front and center, not hiding behind any reverb or distortion. I know the real fans will go on Genius, they’ll buy the record, they’ll look at the lyrics. But a lot of the time, nobody really understands what I’m saying on those records. This one it’s like “dude let’s just throw it on the forefront,” especially in the era of lyric videos. Don’t hide behind it, if that’s gonna be you up front, what do you have to say? And the answer nine times out of 1ten is jokes, that’s just how I communicate with my friends. So that was just something where, if it was going to be more of an Alan Palomo record, and be more personal in that regard, the humor had to be there by design. And the Leonard Cohen realization allowed me to do that.

That’s sick, that’s not someone I would’ve thought had that sardonic wit to poke fun at himself. With the name change, does it feel more liberating not going under an alias?

I think of it this way: when your band’s been around for more than a decade, it’s not that people haven’t heard of you, it’s that they’ve decided whether they’re gonna subscribe to the narrative or not, so you got the fans that you got, right? Once you get to that place, you can definitely shrink but it’s a lot harder to grow. And after three albums I kinda got the feeling, “Well, you completed a trilogy, do you really need to go back and keep doing it? If you’re gonna do it, do something different.” In part, as I got more into directing, focusing more on film whether it be composing or doing features, it just made sense to bring it all in-house. There’s no moniker anymore; it’s just the guy. I still love a good concept album and still love electronics and all that will shine through, but it felt too fun a gamble not to try.

The only thing that’s making it more complicated now, in the era of the algorithm, is that the shit is hard work. Right now, putting out an album is like putting a chip on a craps table that’s run by robots, gambling with your record, and the songs that you thought might be the single aren’t the single. It’s just this shadowy, deliberately nebulous system. We don’t get direct answers about how it works or why it works, and that level of surrender is really scary, but I dunno, I was happy, I felt like I accomplished what I wanted to do when I mastered the record. If fans connect with it, if they don’t, if the algorithm connects with it, if it doesn’t, it’s no skin off my back. The only place it wields influence is trying to make a living from this. So that’s the only thing where I’m like, I hope this pops off! (laughs). ’Cause I’m trying to move back to New York and the rent’s even higher!

Oh yeah, I get it.

But otherwise, there’s this really great line in this Rudyard Kipling poem called “If” and it’s like “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same,” and that’s really the way I try to look at anything that happens with what I do.

Big time.

It makes sense, I mean one of the videos is thriller-film themed, but I didn’t know you were focusing more on the film aspect. It makes sense, you have that pop element but also that Tangerine Dream, Moroder-type experience too.

That’s always been in the backdrop ’cause, the irony is I started making music in college as a reaction to the fact they wouldn’t let me rent a camera until my third year. I went to a film program, and a high school tech teacher let my brother and I borrow cameras and learn how to use Final Cut and we were just making short films with our friends, and then suddenly you’re brought into academia. The way they would whittle people down who wanted to be in the television, radio, and film program was to give you all this prerequisite shit that had nothing to do with what you’re trying to get into, to see if you can tolerate it. And if you can tolerate two years of that, then they’ll start letting you take film classes. I just said fuck that. I was living in a band house with a bunch of musicians and I had already started messing around with Reason and FruityLoops in high school, so I just started a band. I started Ghosthustler, my first one. I think I was resistant to pursue music past Vega ’cause I was trying to pivot into film. I did a short [2018’s 86’d] and scored a bunch of stuff, that was fun. I took any opportunity to learn about the process, whether it be actually getting to direct something or being one of the many people in post, just there to make sure the film lands.

All that stuff is invaluable and I’m happy to have had it, but there is the itch to be like, “You’re 35, shit or get off the pot.” If you’re gonna do film, let’s do it, let’s actually try to get that first feature going. Which, my producer and I, we’ve been talking about what that’d look like, a very modest first attempt at it. But these days you gotta be a little of everything. Who knew that Miranda July or Vincent Gallo were kinda this blueprint for how it has to work now, where you wear all the hats. One day you’re promoting a book, one day you put out a record, one day you produced or directed or wrote a film. I think in this “meme-or-die” economy, it can’t hurt to be versatile.

It definitely seems like you’re circling back around to it like, “If it works, it works, if it doesn’t, it doesn’t,” but there’s definitely a stable base, like a lot of the rollout is really snazzy, it has a nice aesthetic sensibility.

Well a big part of it is like, not to quote Paul Thomas Anderson, but like a big part of why he works with the same actors is “it’s like a band, the more you play the better you sound.” And I love working with Robert Beatty, we did the Vega album cover together. He’s the only guy that will entertain my whim of, like, talking for months back and forth about references and sending clippings from zines.

He’s been on a roll, for sure.

Oh dude, he made so much stuff for this record I almost feel bad. How many single covers, two lyric videos with Mickey Miles, it was this huge undertaking. But again, I mean, he’s the GOAT, he’s the dude that gets it, he understands the references and knows what you’re going for. I’m happy to keep working with that dude.

This one seems like the total package, like aesthetic meets music meets visuals. You’ve got everything down pat sensibility-wise.

We worked on the cover art for I think four months? He was doing it in between other projects for the Weeknd and Phoenix and stuff and then came back and was like, alright we have a little time to try and build this ship inside a glass bottle and eventually we got to that finish line. I couldn’t be more stoked on it.

Is there anything you want but haven’t been able to do? Especially live, what would you like to get out of the tour?

There’s great Leonard Cohen concerts from where he’s got like two backup singers in suits and he’s literally just there with a Casio and a sax player, and he played on TV this way. Obviously the sax player’s gonna be essential, there’s no way to tour this record without a sax guy considering how many songs feature a saxophone in them. For certain shows like New York and LA and Austin I’m definitely trying to put together a backup singer situation. For LA we’re doing that with Mother Mary, who’s on Italians Do It Better, and they’re old pals of mine, so we figured it’d be fun to have them on the bill, in addition to playing with me on stage. This time around it’s like double-breasted suits, saxophone, let’s get dressed up it’s a night out.

Like you’re playing the Arsenio Hall Show.

Big time, big time.

It’s a sick look, and it’s something we don’t get much of anymore. That kind of zazz, if you will.

It’s funny you mention the Arsenio Hall Show, I’ve been screenwriting and there’s this really great interview with Alexander O’Neal, who was fired by Prince, on the Arsenio Hall Show, and of course how does he show up? Big shoulder pads, double-breasted suit, skinny tie. And I love the brands of that era: Thierry Mugler, Claude Montana, and the Japanese stuff. Like there’s Issey Miyake but in the ’90s, there’s this dude in particular, have you ever seen Takeshi Kitano films?

Yeah Beat Takeshi is a beast.

Big time, like Boiling Point (1990) and obviously Violent Cop (1989), and throughout the ’90s, Yohji Yamamoto was his stylist, so all the Yakuza dudes are wearing Yamamoto. That and Miyake have been on eBay alert for like the past decade. At my height, the Japanese stuff fits better, you don’t have to do a lot of tailoring. I love that look and I definitely want to bring that to the stagewear.

When you come to Brooklyn I’ll have to show out in like a zoot suit or something crazy.

(laughs). Yes!

Alan Palomo’s World of Hassle is out September 15th on Mom+Pop and is available for pre-order at Bandcamp.

Thank you for reading the eighteenth issue of Tune Glue. Get this man dripped out in Yamamoto stat.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.