Tone Glow 179: Doseone

An interview with rapper Doseone about Alan Moore, cats, and his new album 'All Portrait, No Chorus'

Doseone

To say Doseone needs no introduction ignores the facts of his current circumstance, namely that a new generation of underground rap fans is hearing his music for the first time. So, here’s a primer doubling as an introduction to a 9,000-word interview. Listening to Doseone is like hearing a children’s cartoon voice actor battle the grim reaper, or a musical theater professional channel both. To be clear, he’s neither a voice actor nor a theater professional, but his battle raps are beyond reproach and often in conversation with death. He’s been putting out wildly idiosyncratic, many-voiced music for the better part of 28 years. He’s been in numerous groups, including Deep Puddle Dynamics, Themselves, cLOUDDEAD, Subtle, 13 & God, Nevermen, Crook & Flail, A7PHA, Greenthink, and Go Dark. He co-founded Anticon. He survived two devastating tour accidents. He now soundtracks video games. And his newest album, All Portrait, No Chorus, produced by Steel Tipped Dove, is out on Backwoodz Studioz. Samuel Diamond spoke with Doseone on January 30th, 2025 about the art of the verse, the end of the world, and the best moments of his life, featuring British writer and warlock Alan Moore.

Samuel Diamond: On “Inner Animal,” you start if off by rapping, “Put the needle to the groove, I get fucked and I’m forced to fix it up / My style varies like a virus in flux.” You’ve rapped, sang, and spoken in so many different styles, and many of them are present on this album. Taking off from that line, I’m curious to hear how your writing and styling influence one another. Which comes first—the words or the style—or is that a chicken-or-egg question?

Doseone: It’s definitely layered how they eventually manifest. I heard that beat, and it was like I’d just heard [“Protect Ya Neck”]. That was literally that style. This song has that line to thank for all that mess. When I rap, I’m always impersonating every rapper. So, that’s my Inspectah Deck impersonation, with no disrespect—an homage, hearing my voice the way I remember Deck’s voice feels when it comes in on that verse. That’s how my voice found that pocket.

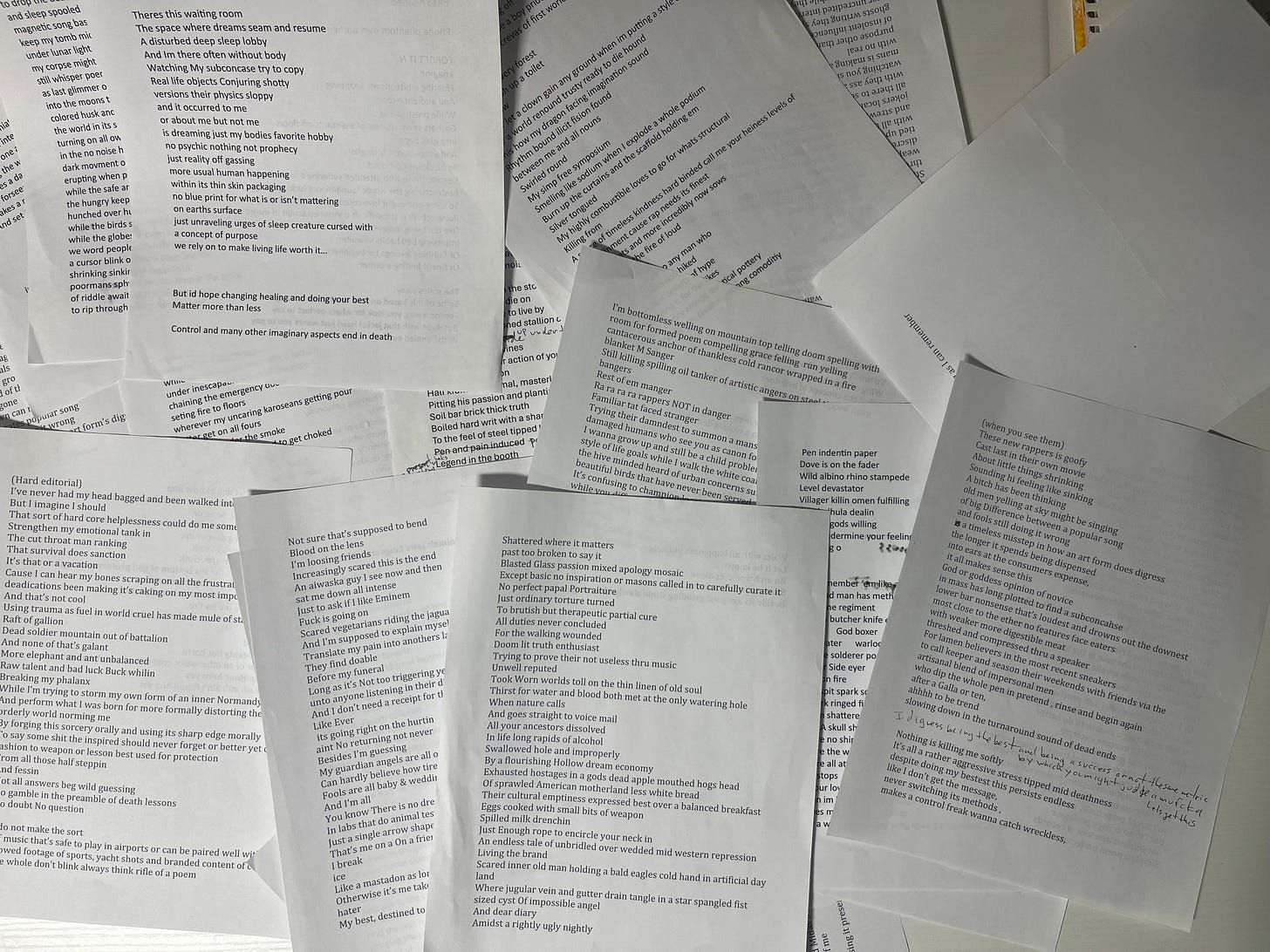

I would not say I always hear my tone when I start writing. I sort of hear the length of the couplets, how much I’m going to get in a bar. I write on paper always. I realized the phone was killing my vibe, because I’m trying to hold onto where these words are going and then just for a second, I have to be like, “not barrel, bonnet.” Seeing that [autocorrect] is going to put this wrong word down makes me back off this thing I was sniffing like a hunting dog.

I write, and then I sit with the beat and try to be really loose, like I don’t know who wrote this great rap for me, but I’m going to do my best with it. I pick it up again, listen to the beat, try to find something unique and sometimes I choose a pocket or a tone for my style that is very much opposite the content. What if I did this calm thing fast? What if I did this dark thing calmly?

The last step is I go into the studio. What I was doing isn’t always a hot egg. The drummer in Subtle used to say very politely, “That’s stock for you.” I think of that constantly. I take a break, have a smoke, come back, listen and I’m like, mm a little stock for me. I can do this again. It’s just a verse. Not being beholden to any one take—that’s something people don’t get when they hear a record like this. I do these verses 40 times, but I’m going for something that feels natural and first time. All the breath control has to get down. I have to figure out how the hard parts become fluid, so it doesn’t feel thought of—it feels walked into. That happens on every song. That sounds like a bunch of bullshit, but it all happens really fast.

I mean, you’ve been doing this for decades now.

Yeah, and the thing I’ve learned about creativity is if you’re grumpy and it’s the day you pay taxes, that is not the day to write this amazing poem or deliver this crazy rap. Sometimes a horrible day can go into the booth, into the pen. But for me, there’s basically this time. I think about my cat a lot. I have no control over this animal, so when it comes and sits on me, we are cool for a while and then we’re not.

We’re going to get back to that.

There’s this thing about creativity where I can tell when it’s behind me, pushing my pen. Then there’s a time where I can hear a dope beat, but however I’m feeling, I’m just not ready yet. That identity is beyond me.

“Put the needle to the groove, I get fucked” is hilarious, but I wouldn’t say the song is. What was your mix of emotions on that one?

The best part on that song is, “Burning eternally everywhere like blood burgundy / Bursting veins during surgery, move with worker bee urgency.” This whole record, I plant my back foot in the art of the verse. None of this was intentional, but it felt right to keep doing this to these beats. Fuck a hook. Every song has a little pullback in the very middle where I say something a little slower. On “Inner Animal,” it’s when I drop out of the Deck style, and I’m doing, “The person you been starts to feel real phantom limb.” Then it’s pocket, just manifest. I’ve been getting into these fugue states with rap writing. I’ve been using this language my whole life, and I’m not bored. Everything is exciting, difficult to execute.

You know when someone is whacking a tennis ball constantly by themselves? You get into that and start impressing yourself when you’re writing. You can never pause and be cocky about it. Like I was saying about autocorrect, there’s this teetering edge where it might get even better if I keep it cool, keep channeling and letting this new idea happen.

“Inner Animal” is I’m just having fun being a rapper. I love to write like this. That’s why this record dips into the problem with mainstream rap and then back into my thoughts and feelings or death or love or dreams. I’m getting loose. I’m a cypher rat. I had to grow up and have trauma, but the happiest I am is not after a big show on tour or seeing my name in lights or reading an article. It’s making rap, my versions of stuff, hearing a beat and then applying my voice to it. So, that’s all I do now. It’s just about doing what I love, and what’s the next song? That’s what people want. They don’t want to see me on a boat, drinking rum and coke in a bikini.

Another funny line: On “Went Off,” you said, “This ayahuasca guy I see now and then sat me down all intense just to ask if I like Eminem.” I’m not going to ask about the Eminem battle, but I’m curious how improvisation factors into your writing. Do you ever find your writing to be like edited freestyles, or do you make a cognizant effort to separate the two?

You know how Jay-Z will be like, “I don’t even write. I just go in the booth?” Now, that’s ridiculous, but for me, when you’re the luckiest, there’s getting in the zone and every once in a while, I just hear a line. I’ve got to write that down and work out of there. Generally, it is the beginning. I’ll hear the first idea.

That [line] is a true story. It’s happened multiple times. Some ayahuasca guy will be like, “I think Tupac is better than Biggie.” They reduce me to some CD booklet of rap only. And their version of a hard-won opinion—don’t waste my expertise on that. “Hey, I got a serious hip-hop question for you. Is the fifth or seventh Busta record better?” None of those! What are you doing!?

What’s your mindset stepping into a cypher versus sitting down to write?

Both forms are testing your mettle, just in completely different ways. I have to compose and rap on the spot, outdo myself, keep myself entertained, not do anything I’ve prepared, really be spontaneous and in the moment. When you sit down to write, it’s the same M.O. You just slow cook. The quality control I can do better, but when I’m writing I try to allow myself the spontaneity and originality that freestyling demands. I do that when I record as well. Certain lines get stiff. I’ll throw the whole thing out and say something I think up on the spot.

If you’re listening to someone freestyling on a song, it’s great, you’re giving them credit for making it all up on the spot, but when you listen to the same artist’s really well-done work of progressed verse, that shit will take you on a journey. It’s a different set of organs, but they’re both important. Sometimes I’ll hear new rappers, and I can just tell it’s not the keeper take. They just did one take and their boy was like, “That’s perfect.” You can also hear that freestyling has left the zeitgeist. Sometimes I hear in rappers that the only 20 times they’ve been on the mic is their 20 songs. They are not rapping on the street. It’s a 10,000 hours thing. I can hear it in everybody. What’s that show on Netflix?

I can’t remember off the top of my head but I ran through both seasons. It was fun. [Editor’s Note: The show is Rhythm + Flow].

I love rap shit! My favorite thing on that is now every kid, before they rap, they mean the word “listen,” but they say the word “look.” Instead of “yo” at the top of the track, they’re all like, “look.”

But yeah, I think they’re both really important and everyone benefits from doing both. When I would teach kids, I would always let them know you want something you can own [and] develop an identity around that’s creative. You can still be merciless on the mic, but it’s positive for you. It’s better than your fucking government name. There’s a whole aspect to living in shitty neighborhoods. Rap is one of the only ways to access that, that nobody judges you. When I transitioned from fighting all the time—I still wrote graffiti across the gap; that’s where my rap name came from—I was getting let out of the immediate violence because I was cooking this thing. It was almost like an urban athlete: “Don’t shoot Darryl! He’s the quarterback!” I found a space through still being aggressive, being myself but being creative. I was still in the places where I grew up, but I was like, this is so much healthier. So when I get to work with kids, that’s a big thing to give them, and freestyling gives you that. You don’t need to have money. You don’t need to record yourself. If you freestyle on the street tomorrow, you’re a rapper. You might suck for a while, but nonetheless, you’re more of a rapper then than if you do one song.

Changing directions completely, I’m a big fan of Alan Moore. He’s inspired me more than any other writer. So, I want to talk about Unearthing, which you soundtracked. Could you speak about what it was like to work on something by Alan Moore and what his writing means to you? Did you ever get a chance to meet him after the project was completed?

I’ve got some good stories. No one asks about this. Tom Brown at Lex—who’s a great guy, put out all the Subtle stuff as well as Fog—got in touch with Mitch Jenkins, who was working with Alan Moore on various things. Through [Jenkins], [Brown] got the chance to do something with Unearthing and asked me if I wanted to do it. I grew up on Watchmen. I immediately was like, yes! He was like, “You should do it with [Andrew] Broder.” Broder didn’t read graphic novels as a kid. He just said yes because I was so excited. That’s how that all begins.

But when I was a kid, I lived with my mom who was pretty abusive, and I would see my dad every other weekend. He lived in Manhattan, and I lived in Jersey. We would go to Forbidden Planet. I would get a G.I. Joe comic, and he would get Watchmen and Elric and Dreadstar. I would read his adult comics after and then I stopped getting the shitty corporate comics. I started reading the same shit he was. It was one of my first influences, one of the first things I thought about and drew. I went on to be inspired by The Invisibles and Preacher and other great works. Right now, Monstress is really great. I fucking love Alan—huge inspiration.

We work pretty remote. He reads the whole book on tape, and we start scoring it in sections and bringing back melodies throughout. So, first I had to read it all, which was really fun, and be like, oh, this is more Stephen Moore stuff, and I would pull those sections and be like, “Steve theme.” I made a blueprint. Then Broder and I made all the music. Then we went and performed it with him.

Kevin Spacey, before he got canceled, while he was still a sex offender, bought a tube station in London and did some plays in there. We performed there. I am sitting there, haven’t met Alan yet, and I’m doing something on my MPC. Jel is there also playing MPC, and Broder’s on piano, guitar, and other things. I’m sitting there and I just hear, “Are you sorted?” So, I start looking up, and I just keep looking up. The motherfucker is basketball tall. And I’m like, holy shit, it’s him! Beard! Wizard rings! Staff! And I go, what? And he goes, “Are you sorted, mate?” And I go, (sheepishly) “I don’t think so? And he puts his hand out and drops a crocodile eye of hash on my MPC. And he goes, “You are now.” Then he walks past me! And that was it! I was like, what the fuck, dude! I can’t believe I met the coolest dude ever, and he gave me drugs and did a weird ’40s joke I didn’t understand. That was amazing. We start hanging out that night.

This was the other really cool thing. Selfishly, I gave him [The Ought Almanac of Amassed Fact], which is all the longform writing from the Subtle trilogy and universe, about Our Hero Yes. I only did like 100 of them. It’s a book that only a few people have, and it’s the whole point of this thing, so I saved a few, and I was like, I gotta give this to Alan Moore. It’s got my best writing. So, I give it to him, and I’m like, hey man, you can leave it at the hotel, I just—you’re my hero. You have an influence on me. I want to show you I write good because of you. So anyway, we do the rehearsal. The next morning, he comes in and leans over to me—same kind of thing, just walks right up to my station—and he goes, “I really liked ‘death fetching dogs.’” He fucking read it. I was like, aw, dude, this is amazing!

Also, for that performance, I flew my dad out, because [Moore’s writing] was this huge thing. It got me through my childhood. It was literally the only good thing for a really hard period. So I brought my dad and we just smoked a thousand joints with Alan Moore and all his weird, goth, comic-god-tier contributor UK friends, all these awesome trans women. It was the fucking best night ever. We’re all just giggling. Alan Moore told stories the whole night. He held court, and we were all there for it. It was great. Coolest dude. We got to do some films with him. I went to Northampton where he’s from. Best moments of my life. I’m really grateful to Broder for saying yes, because it couldn’t have happened without him, but he was definitely not as in awe as I was.

Yeah, he’s “it” for me, and not just the comic books. I love all that stuff. Of course, that’s how I got into him, but his novels now—

Yeah, the best thing about thing about Alan Moore: He does not have a computer or a phone. I have to email his neighbor, and he prints it out and walks it over to him like a fucking town crier.

Have you maintained correspondence?

No, I fell out on the film because working with the middleman was pretty wack. We weren’t getting to work with Alan. I would see him when we celebrate finished work, but it wasn’t totally satisfying in that regard. I had just started doing all these video games, and they were taking off, so I had a better creative exchange with that, It’s harder work for games, different work. You’re still being creative, but the relationship to direction is preferable. Anyway, it was amazing.

That’s awesome. I’m super jealous. Jel called your performance on All Portrait, No Chorus (2025), “The Dose that all rap heads back then wanted to hear.” The Dose that made this rap head a fan to begin with was on Crowns Down (2009) and The Free Houdini (2009). What is it about Dove’s beats now and Jel’s beats then that bring out this kind of fire in you?

Two things happen. Sometimes, anyone gets in their own way. Sometimes, you start working on beats that don’t allow for fire like that. But on All Portrait, No Chorus, I’m relentlessly rapping on every kind of beat because that’s what I’m accessing right now.

Honestly, Ka is a huge inspiration for me. You know how I was saying earlier, oh that’s stock for me? I listen to billy woods and Elucid, and it makes you want to hit the heavy bag. I don’t hit the heavy bag, but I know that feeling. The compulsion is to go harder in your version of paint. I’m grateful I still got the juice to do that, let alone execute, just the fact that I am still enamored with that and addicted to pushing myself. You do your best, and if you have a good relationship with your creativity, you go back to your work that you outdid yourself on and you’re like, there’s room to grow. I’ll be damned! The willingness to get back into that exchange with yourself is something I’m really happy about, because I wanted to be a career artist—someone who went their whole life making it work. [That’s] the best thing I can think of in this shitty world. It has all the qualities I like in the world but affects no one negatively.

On “Oversleeping,” which is on both Crowns Down and Free Houdini, you gave out your address to would-be opponents. Do you have any stories of rappers, known or unknown, showing up on your doorstep as a result?

I felt like people kept taking shots. I was just letting them know where I’m at. You can stop by. You can get the ZIP code. Come to town, man. I’ll serve you out of my stoop. However, the only person that ever used that was a weird squatter girl with a rollup bag. My bell rings. I’m in the middle of doing something. I open the door like, “Hello?” And she’s like, “Hi, I got your address off—” and right away I started finishing her sentence in my head. Motherfucker, she’s here from the rap song. She was very nice, but she was like, “I was wondering if I could have a place to stay.” I was like, I have to go, bye, and slowly shut the door. I tried to be as polite as possible about getting called out not in the way I wanted.

You were like, “This was for battle rap.”

She came for kindness, like “Will you do me a service?” I felt weird, but it was not my intent, so lesson learned. Funny how the world works.

What can you tell me about Lionesque aka Lioness who appeared on a track on those projects as well as one on Hemispheres (1998)? The only other credits I could find for her were a few Illogic tracks and another appearance with you on a Greenthink project.

And I think she did a song with J. Rawls or at least some rough ones. When I was in Cinci, before I met Atmosphere or Sole, I was rolling with Dibbs. The other guys I hung out with, who I met before Dibbs, were the Five Deez, Fat Jon. We all got down because we were hip-hop heads and Cincinnati didn’t have a good record store. If you had Dr. Octagon, nobody had heard it. So, we were sharing music, making music. There wasn’t really a lot of studio access. I met J. Rawls. We would record on his 4-track. All my first music existed because of him with his AR-410 and 4-track. And then my roommate—we were friends first in the dorm—was Liya, Lioness. She just really loved rap and was from Cleveland, getting exposed to new music. Cleveland just liked Bone [Thugs-N-Harmony], Blacc Monks, MC Eiht, CMW, Too Short.

Blacc Monks are pretty good.

All of it’s pretty good. It’s a different bag and then they come and hear Latyrx in my house. Underground music was hard to get back then. Key Kool and Rhettmatic: Whatever I had was interesting. It was what I was addicted to and trying to get more of, so I made a lot of friends and we would just listen to rap, smoke weed and write raps. There were all these other rappers that weren’t in the Five Deez, and we all chilled on campus, rapped at the Black frat parties—one of the only places where there was avenue for us. And Liya just started rapping. She kicked one verse that she was working on. I remember it was me and this dude Digby, maybe, and we both looked at each other like, you need to keep doing this.

We did [“Spitfire”] together, it was great and I loved working with female artists. Now we have a lot of really authentic voices that aren’t just faux masculine, but there wasn’t a lot back then. You kind of had to rap like you had a dick, and now you have people bringing their version of femininity to the boy’s club that rap is. She doesn’t do a ton of music, because life and work.

I thought it was cool that you reconnected years later on “Long Time Coming.”

It was meant to be. [Jel and I] sat there like, who’s our past? Right away, we both were like, oh shit. I had to use Facebook to holler. She was so excited and it felt great to connect the dots.

I’m doing some music with Illogic now, which is great too. He’s so nasty, hasn’t lost a sparkle. That’s the thing. There’s no rulebook for rap. We’re only 50 years in, a few generations of contributors. There’s all kinds of great things about the young man’s game aspect, but you don’t have to get worse as you exist longer.

Yeah, you mentioned Ka.

You’re not an NFL quarterback. You don’t need knees. You can push your mind, live your life, heal from your trauma or not, and you can manifest and work on your craft forever. I’m grateful for it. I see it. Everyone on Backwoodz is not 20. The jig is up.

Your first projects—Untitled (1997) and Subtitled (1997)—were also done with one producer, J. Rawls. Is there something about that format that appeals to you?

I don’t believe in god. I was blessed, though, to have J. Rawls in my life, and we did all that music together because no one else made beats. Fat Jon made beats. I tried to get a few. We weren’t professionals yet. Someone would leave their beat machine at their aunt’s for three weeks, so you didn’t have the cables. This guy made you a beat. You had a tape of it. But you could never get it down and rap over it. There was this whole “becoming of it” part that was difficult. So, working with J. was this gift of necessity. We evolved quickly together. Like I was saying about recording, I can tell when someone’s only done 10 songs of rapping because when I went to first [record], I was like, this is my voice? It took me a very long time to find that my voice is many. That even took 20 years, but 10 at least to master my weird voice, be myself, and rap well all at the same time.

Anyway, I love one-producer [projects]. That’s why I love Buck [65]. He makes his own beats, he raps on them; one guy, total mood. Most people have to [adjust] five knobs. Buck has one knob and it’s him [cranked all the way up]. That’s something I’ve always envied. Gang Starr, Rakim & Eric B.: Those are my first heroes. I’m not a formulaic guy, but that aspect is endearing. And with Dove, no two beats sounded the same. So, my work was cut out for me and totally enjoyable. Literally, the richest I ever feel is when I have 10 beats from someone.

Another one-rapper, one-producer album of yours is Less is Orchestra (2018) with Alias. It’s been five-plus years since that came out. What do you think about your writing and your performance on that when you look back on it?

That’s my best record for a million reasons, the most important record because it was the last thing Bren and I did together before he passed. We hadn’t played it for anyone. We made it really fast, just like All Portrait. I was at the height of whatever I have, my talents, not getting in my way, being wild and well written, unpredictable—all the things I value. I was in the zone and channeling. I would do a little bit of shrooms then write to the beat, and I would write the whole thing in a sitting. The next day, I would record it. I did one or two a week but not pushing myself. It was very concerted.

Ritualistic almost.

There’s an aspect of that record where it’s my best work as a writer because one line on song two becomes the chorus on song six, and it’s a really woven work. It’s super authentic because it’s about [being] middle-class or less and dying at work. Bren and I were both working corporate jobs to save ourselves from debt and life sucking. We outdid ourselves, were so happy, and felt like we had made the best thing. Tragedy happens. I can’t listen to that record. I cry like a baby to this day. I know how good it is. Its influence is in me.

The good part of the story is when I got back to All Portrait, No Chorus, because Dove was so generous and talented, that space opened up for me again, and I wrote a song in a single sitting. Sometimes I would write two in a day. I had one—I think it was “Wasteland Embrace” or “Ta-Da”—that I pulled over the car [to write] wherever the fuck I was. That’s the name of the game for me now. I just try to be a vessel, face the music, and then create the art and that’s it. We do some videos, but I put everything I have into the art. The thing that’s changing for me now is I was always really hard on myself. It was hip-hop meets football meets street: don’t be a bitch, double this, do more. And then something in me was like, I don’t gotta get kicked to move. You’ve always all-caps’d me to everything I stepped up to, this inner voice. I was like, let’s drop the caps—indoor voice. Be cool. Know when I’m in the zone and when I’m not. I’m still outdoing myself but just trying to be a little kinder to me. I’m a lot more grateful because after losing Bren and Anticon, I didn’t know if I was going to get it all back again.

All Portrait, No Chorus is a product of being really inspired by ShrapKnel—Nobody Planning to Leave (2024) with Controller 7, the Decay record (2023), all the other Backwoodz stuff I had been hearing, other music I’d been listening to, and then it comes back, and I’m in the light in my own creativity. The cat behind me, whatever it is, it’s in good space. I don’t abuse it. I take breaks between records, write little things down, but I leave it all for the moment. Like you were saying, over time I allowed improvising to be at least part of the process. I’m gonna wait and come up with it on the spot. I don’t want my songs to collect like dust. I want them to strike in as lightning, and you can hear it in the music. At least, I can.

On the topic of collecting dust, Less is Orchestra joins the ranks of a bunch of out-of-print Doseone albums, including Hemispheres and Ha (2005). All of your music has personal meaning to you and to your fans, so what goes into that decision of whether or not to repress a project?

One thing is childish. You’ll be 20 and still buying shoes with room like your feet still grow. You don’t really grab the handlebars of age and understanding. With all the physical stuff, there’s this bullshit ideal that you decrease the value of the original pressing by repressing it. It’s not real. It’s still the second print. You can still make too many. You still have to understand your demand. You can make it nice. But there’s also this voice in my head that doesn’t want to play myself. How much of my past do I celebrate as I’m trying to be on planet now, outdo myself, and make cooler art now than ever? How do you do it perfectly? I wouldn’t say I have the best balance.

With Handsmade, I want to do a Themselves tape box set because none of the Them records have been on tape. Hemispheres is a no-brainer, but I can’t listen to Hemispheres. There’s some moments, but that’s right on the line of me learning my writing and rapping and experimenting in both aspects as well as being a natural and getting better. They were still warping to a solid.

Do you ever listen to Untitled, the stuff before Hemispheres?

No! That’s even worse. I don’t have to hide under a blanket, but there’s some moments where I’m like, Jesus, what is going on?

To you! But to a fan…

It’s two different things. Sometimes, I say something where I’m not sure why I thought that should be a pronounced lyric. Other times, there’s a rigidity to the rhyming and being a lyrical miracle that is burdening the guy who wants to style or be more one with the music. When you listen to stuff like “Epinephrine Pen” on the new record, there’s all these different places on the beat I can drive a nail into the board, and I’m being my version of liquid, pocket to pocket. That’s letting go, writing something interesting that I feel confident letting go about. That’s where things eventually got. But when it started, there’s stuff where I’m doing a bit of all those things not as expertly.

Did Skeleton Repellant (2007) and Slow Death (1998) get repressed?

They were always [out] on CD. When I did Ha, it sold really well because CDs were still selling. With Hemispheres, I used to pay my rent selling CDs to U.S. distributors. They would sell them wholesale to U.K. distributors, and I would sell a few 50 boxes a month, so I would make like $500 and could live off that. Then, once Napster happened, it was literally $30 in a six-month period. We’re smart people. We’re in the Bay. You knew it was coming, but it was like some cartoon where you go to the watering hole and it’s dried to a drop. So, [for] Skeleton Repellant, I pressed the normal amount of what I sold on Ha and then the CD apocalypse happened, and I have thousands. The funny thing is with Hemispheres, I had extra of those too for a while. Everyone I knew, for their birthday, I would give them 10 Hemispheres.

The first album of yours I ever bought on vinyl was The No Music of AIFFs (2003), which I found in the electronic music section at Barely Brothers in Saint Paul, Minnesota. This was 2019.

With my cat Purple on the cover.

You were in great company in the electronic section because I also found Nephilim Modulation Systems’ Woe to Thee O Land Whose King is a Child (2003) there. Later I also found Subtle’s For Hero: For Fool (2006) there. As someone who’s worked in Amoeba Records, how do you categorize your music collection at home?

My shit is so on the spectrum. I guess it’s sort of organized by genre because all the ambient and morning records are in one place.

When you say morning, what do you mean?

Like Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians, The Sea and Cake’s The Fawn (1997), Music for Airports (1978), all the good first Eno—peaceful morning shit. That’s all in a zone. Sam Prekop was the singer in The Sea and Cake. He’s been making ambient electronic music, and it’s probably my favorite music of the last three years. It’s not like, hey, you guys want to party? But my god, you put it on in the morning and it’s just like, ahh, it’s going to be alright. Then I have a huge harder, harsher noise drone section. Then I have all the artists I worship spread out in their own section.

Regardless of genre?

Yeah, Microphones/Mount Eerie/Phil Elverum/Mirah [have a] whole zone. The Weilheim Collective—The Notwist, B. Fleischmann, Lali Puna, Ms. John Soda, Tied & Tickled—that’s a whole zone. Then there’s a friends section that is all the Anticon records, my one copy of all the weird shit I’ve been on. I don’t really listen much to myself in the house. When I’m making stuff, constantly.

Then the majority of my collection is rap. I have all the original Fondle ’Em records, all my original [Mystik] Journeymen, [Freestyle] Fellowship vinyl, all the SoleSides. I have an era of rap where I bought the most—the first Swollen Members 12”, the Erule – Synopsis 12”, Ras Kass – Won’t Catch Me Runnin 12”. All the gems I coveted as a kid that I only had on a hissy tape, I made sure when I had video game money, I was getting that, like Volume 10’s first record on vinyl. I never saw that in a store. It’s a shitty pressing, but I was like I’m getting that tomorrow. Still collecting, filling out that. And then everything that I grew up on: Showbiz & AG, Lord Finesse, Gang Starr. Organized [Konfusion] I fucking loved. Da Artifacts’ first record [was a] game-changer for me. SlaughtaHouse (1993)—I have a lot of Masta Ace. I’m a big fan.

I listen to a lot of music in the house, but I make music all day for games, so for my own sanity, part of my day is birds, the hum of the heater, not making decisions about music. It’s healthier for me. Nobody can do anything all the time.

I find myself more and more listening to music on Saturday morning. The work week is over. I’ll throw on a record, sit down, and drink my coffee.

I love The Meters in the morning, James Brown, E.S.G. sometimes, a lot of electronic stuff too, Board of Canada. The first thing I did when I finally got a house and had room was set up a room that revolves around the turntable and tape deck. I can play all the music I’ve been collecting. I can be like, oh, look the second Lynch Mob record on tape! Let’s listen. Same thing with my old video game consoles. When I moved, I realized I’m just a bunch of collections: keyboards, tapes. It kind of made me sick, like what am I, some kind of rat?

That’s life. It’s the little things that make you happy.

The objects I deem collectible, and that’s all I’ve become!

There’s nothing wrong with that.

No, I think that’s humanity.

You opened “Restaurant Not” with “My songs are not a restaurant / Sit down, be nice, get what you want.” When you fell in love with rap, which artists challenged you as a listener in the way you’re talking about, and what was it about their music you found challenging?

Well, Myka [9] and Fellowship, of course—all of [Project] Blowed. Over the years, every time I heard them, not just the first time but new works, it’s just, woah, I got to go to school! The same way woods makes me want to go to the gym with pen, those guys made me want to go to the gym of rap calisthenics. Saafir also rocked my world. Saafir and Myka are just doing every style. Chaos is their style, being unpredictable, outdoing themselves. It felt like they didn’t want to get bored. That’s a very lackluster way to describe how talented we all are, but you can tell they’re like, “I want to evolve every verse, I want to have all these ranges,” whether it’s content or rap style, melodic shit, chops. So, hearing Saafir, I was like, he’s not even on beat and none of that rhymed and it sounded nasty. I was insulted and inspired.

Pharoah Monch—when I first hear him on Stress: The Extinction Agenda (1994), that was formative because there’s a pre-[Organized Konfusion] era where we thought Das EFX was really good. You forget how much preschool information was on the record. When I played that in the car, my girlfriend wasn’t being tacky, but she was like, “Was this for kids?” They saying buckle my shoe and hibbidy hoo. The whole thing is Looney Tunes infusion, also Fu-Schnickens after that.

GZA was huge for me. I started trying to be smart because of GZA. I’m his fault. There was just something to that pen game. He was one of the first guys to say something intelligent to offend you to make you step back to appreciate it. De La Soul was also always doing it, but it wasn’t weaponized. With GZA, it was really offensive, and I don’t mean vulgar, but on the offense with well-crafted swords, things with a point that he thought about. It was pivotal, a huge inspiration for me. All the Wu-Tang [were too], but Liquid Swords (1995) made me start writing raps. I was freestyling crazily and battling, but nobody wrote because it wasn’t respectable to [kick writtens], and we didn’t have anyone to record so what was I going to do with a bunch of written stuff? But I heard that record and super scientifical madness started to ensue.

A lot of people did a lot for me but didn’t do a lot of music, like Erule. I remember hearing that on tape and listening to it a thousand times. I listened to KMD. I studied Black Bastards (2000). It wasn’t released, but we had a 70th generation tape. I liked Cypress Hill. That production was something I got into. I remember being a young kid with an EPMD tape, like, how did they get the little men in the tape? I didn’t understand there was a beat. At one point, it occurred to me this is production. Then I hear a sample. So, how is this music getting into that? No one showed me anything. That Cypress Hill record was one of the first records where I was like, “Why do I like this so much? It’s the beats!” I needed something to wake me up. All I was thinking about was rapping. Then I started to appreciate the Bomb Squad and the first three Public Enemy records immediately because it clicked. I started hearing sample quality and chops. I didn’t know how it was done, but I started to get it.

I knew you grew up in Jersey before relocating to Ohio and then California. But it wasn’t until I was preparing for this interview that I realized you came up battling in Philly.

That’s where I went to high school.

What was that like? Did you ever cross paths with Last Emperor or MarQ Spekt or the Lost Children of Babylon.

No. The Dead Pigeons were always around and a couple other crews and individuals. The first two Roots records—fucking huge for me. Black Thought [was] incredibly inspiring. We would sneak in to see the Roots open for the Goats, because nobody really loved the Goats.

I love the Goats!

They had some good songs. “Wrong pot-pot-pot to piss in.” We loved the Roots, and the Goats we liked. But it was vicious. We would battle everybody. You would go to a house party. Ten minutes later, everyone raps. There’s a trash can full of jungle juice, a band in-house. We’re smoking dust. We’re smoking blunts. And everyone and their mother raps, from very bad—you shouldn’t be doing this—to very good. You would see someone rap and have no static because they were of similar caliber. You’d never see them again. In our school, not many people rapped when I started. But the best thing about my era in Philly is you couldn’t go 10 minutes before you met someone who was lying about being in the Roots crew Organix. It was fun, though.

Freestyling and battling allowed me to cruise for something that wasn’t trouble, and it did pull me out of my own worst efforts. I had nothing to look forward to until I rapped. It wasn’t enough just liking rap and collecting it—I had to do it to feel like I wasn’t a waste. It was a big thing, and it all started with liking good rap. I was a fan. I was pretty bad when I started but I learned fast.

I brought up Last Emperor because he was the first underground rapper I heard. From there, I got into Company Flow and Aesop Rock, but it wasn’t until many years later that I realized Mr. Len produced a track on Hemispheres. How did you guys link up?

That was at a rap battle in Columbus he was judging. I was not liking anyone, and then Illogic started rapping. He was dope, but I didn’t know who he was until later. I didn’t hear his name. I was there with Infinite Evol, who was a maniac. He was incarcerated for a bit, but he was one of the only dudes who would roll up and battle everybody with me and could freestyle off top. He was a lot, though. He was a handful as they say in the cypher, but he was a good time, and I had a similar relationship to rapping at the time. We were out there battling whoever wants to get served. I think I served Copywrite, some other people I didn’t know. Then I meet somebody that I knew that was rap adjacent and they’re like, “Hey, this is Mr. Len.” I’m like, “Woah, get the fuck out of here. I love Company Flow.” He was like, “No way. I heard you rap and that was amazing.” And he gave me a copy of Tragedy of War in III Parts (1997), a test pressing. I still have it. He signed it. He was like, “Give me your number.” This was before cell phones. I called him, asked him to do a beat, told him what a big fan I was, and then told them to listen to Latyrx.

I also kicked down the door on Latyrx at a show and was freestyling with them and we exchanged tapes. I sent Lyrics Born my demo. The only guys I wanted to access, I got the weird fortune of meeting in strange ways through Ohio, the middle of nowhere. I was the first person to really reach out to Aesop. Slug gave me his demo and was like, “I think you’ll like this.” I was like, this dude’s amazing. I reached out, we recorded some stuff for him and for me, and I got him a deal with Mush. Of course, everyone got ripped off. Also, I was at the Atoms Family house once, and Mr. Len called me because we were gonna hang on that trip to New York, and he was like, “Where you at?” “I’m at Cryptic’s with Atoms Family.” “Are Vordul and Vast there?” “Vordul’s here.” “Put him on the phone.” It was the first time before Cannibal Ox that those guys spoke.

Woah!

Yeah, so lots of synchronicity being in interesting places at the right time. I met a lot of rappers. A lot of them did not want to get met. I met El-P. It was not the same as when I met Len. [El-P] had rapper energy. You don’t want to meet the other rapper. Rap was not the easiest back then. You were talking about Last Emperor, and I was thinking about when you were underground, getting manufactured, put on, or even recording was some weird miracle. You knew all these people that rapped and made beats, but no one could ever make anything exist. It was all such a challenge that when you did have someone, what did you do with them? You can’t play your shitty town. It was such a different era right before the internet hit. The internet amplified various aspects, but the gatekeeping was insane. Now, you can be on Instagram and have some access to the pipeline. Then, even just trying to understand where the rap pipeline starts, I remember being like, “What am I supposed to do?” Taking headshots, rapping at talent shows—none of that works.

On my commute today, I ran through Untitled and Subtitled. Yesterday, I was playing 13 & God (2005). Then, a friend of mine wanted me to bring up Nevermen because he’s a huge fan of both of those guys. Between those projects, there’s a huge range of sound. I’m curious where you’d place All Portrait, No Chorus along that spectrum.

Dove and I have become close. We hang out. Two peas in a pod, we have so much in common. But going into this, we were just inspired by each other and started cooking right away via satellite. This process, like Less Is Orchestra, [is] very rewarding for me. I’m breaking through. I’m an old dog. I’ve done this a million times. To be like, oh shit, I’m killing it right now—that’s all I give a fuck about. That is not necessarily there to be accessed when I’m in a group of many. It’s a different relationship. There’s listening. There’s being empowered. It makes a completely different music that you don’t control. You just add material—your voice, your writing, your sensibility, how you choose an edit—and everyone does their version of that. Leaning on people and getting inspired by them is priceless and literally changes you forever.

Do the experiences from those group settings change your approach when you come back to work with one producer or on a solo project?

You get a different set of stripes when you do a group work. Working with The Notwist, everything sounds amazing. Then you’ve gotta make a Themselves record that holds up to that, just the two of us? We’re not intimidated, but it changes your reality and raises your bar.

But when you work alone and get in that great space, like I was just in with Portrait and I’m still in, I’m just raising my bar. It’s not that I don’t need anyone. It’s chocolate and vanilla. It does not replace that growth. It’s a different kind of growth but just as cool. But I’ll be honest. For a very long time, I didn’t know how to make beats. I just rapped. I taught myself how to make music. I’ve always made stuff, but it’s not my first gift. I’ve always needed someone. So, now I’m in a space where even though I’m working with Dove, I have a better relationship to myself. Like I was saying about kindness, wanting to outdo myself in genuine ways by doing more. It’s not a smarts thing. It’s a wilding out thing, and that is the goal.

You touched on your production. We haven’t heard you take on a full project lately aside from video game soundtracks. Are you producing anything outside of that space?

I did G Is for Job (2020) and G Is for Deep (2019) where I was like, OK, I can produce. I produced the Go Dark stuff and then the EPs I made on Handsmade that were physical only. There’s an ambient one and Even with Demons (2023).

I have a very strange duets record with all my favorite rappers: Six songs and each turns into a whole ambient thing so it’s a little adventure. I’m finishing it now. It’s kind of cloud rap but I use the SP and all my synthesizers. It’s very slow cooked, very textured. It’s meant to be about the end of the world. Even before all this shit started spiraling—Trump winning and so on and so forth—I was like, I don’t feel like I’m allowed to talk about how end times-y all this shit is. Again, I don’t believe in god or Jesus, propaganda, conspiracy. We were supposed to have civil rights before I was born. Now we’re missing some that people had in ’67. I refuse to adjust to this reality by bending my morals. My art is the only thing I can leave standing against it. So I made this world and told every rapper this is a safe space to talk about how bad shit is. It’s not a dark, bemoaning, whiny record. Everybody is killing it and being different. But uh—

But it’s about the end of the world.

Yeah, it’s cutting the shit. It’s about the patriarchies, oligarchs, racism. I try not to give this world any more limelight in the things I create, present and muse about. But this record is kowtowing to that in a way that’s still productive, poetic and different. It was like, do I have a song on every record that drags this out again or put it all in one place?

Oh, that’s interesting. The way you’re describing the music sounds cool, too.

I’m trying to do something that’s original production-wise then be a rapper. The reason I don’t do more is it’s a circle of hell for me to make a bunch of beats then suddenly act like I don’t know how they’re made and start rapping and writing to them. They burn me out a bit. When I don’t have to do vocals and I do stuff for games, that’s the finished thing. I add little vox but no lyrics. But when I make a bunch of beats, sometimes getting the beat from someone else is 10 times more engaging—even if what I made is good. It’s a thing. Maybe I’m broken.

Last question: All Portrait, No Chorus is out on Backwoodz, billy woods’ label, and he features on the song “Wasteland Embrace.” One of the things I like about his music and yours is it’s very clear to me that you’re cat people. What do you love about cats and which of those qualities do you like to find in your art?

Man, cats die. It’s always sad. It’s like kids for me. I’m not a breeder, so I’m here for the cats. When my childhood was so fucked up, I rescued a cat from a cat shanty in Jersey and it was the first thing as a young human that I wanted to do. When I did not have examples of love in my life, I experienced love only with animals. Going into therapy, healing from the abuse I had as a kid way later in life, it’s not a joke. Some people grow up seeing love but not receiving it, so you just sort of believe in it like you do ghosts. There’s whole industries and movies about love, but for people who are traumatized young, it’s just another thing that may or may not really exist, like being lucky. When I got to healing, [I realized] I did love. I had the capacity the whole time. It was all just given to animals. So, really, cats are people to me. I don’t adopt too many. I finally had two for the first time. I would always adopt fucked-up cats, so I couldn’t get another, because they were way too traumatized. But now I have two girls that I adopted in Oakland before I moved to Santa Fe. Slow Jam just passed away from renal failure. She was sick for six years.

I’m sorry.

They’re amazing. They’re my little motherfuckers. And Blue’s adorable. She goes outside now. Slow Jam killed everything. She brought snakes in the house. She killed a fucking gopher—while she was in renal failure. She killed birds, mice. I was waiting for her to come back with a child by the throat one day. She loved her daddy, sweet as day, but she’ll fucking kill you out there on the streets.

When you lose a pet, you realize that for whatever’s good about humanity, all the communication, all the intelligence, all the past you’ve lived through clutters the pipeline of feelings and bond. In the absence of words, time spent with an animal is like a focused beam of just bond—never minced, never misunderstood. When you lose a weird uncle you don’t know, you’re like, I don’t know if I felt any lights go out. When you lose an animal that you love, it’s like the sun is no longer in the sky. You feel the absence of that connection. Now I’m of the age where I’m losing friends, so it’s a whole thing. Getting right with loss and death obviously has been my whole quest for many an album as well as many a day.

You touched on this a little in the beginning of our discussion, and I don’t mean this in a joking sense, but are there qualities about cats that you seek as an artist?

I was talking about the cat disposition being a good relationship with creativity. They just gotta know you’re cool. Cats remind me of how I learned street smarts, too. You can’t try too hard. You’ve just got to be, or you get looked at. There’s this whole way of being that doesn’t involve your mind, and cats really have that. It comes off as arrogance, but it also comes off as not being caught up in all this bullshit. Being a neurotic, traumatized, hardworking, creative maniac person, cooling my jets is not first nature for me. There’s this shutting off the mind that I see in cats that I like. But yea, cats are great. I get a lot of love out of that, and for all the reasons I want a cat I do not want a kid in this world. You’re just free. You get all the good, none of the bad. No shade to the world and its kids.

Doseone & Steel Tipped Dove’s new album, All Portrait, No Chorus, is out now. The album can be purchased at Bandcamp and the Backwoodz website.

Thank you for reading the 179th issue of Tone Glow. Cats on top.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.