Tone Glow 163: Shovel Dance Collective

An interview with the British folk music collective about navigating the histories of labor through music, reaching towards the sublime, and their new album 'The Shovel Dance'

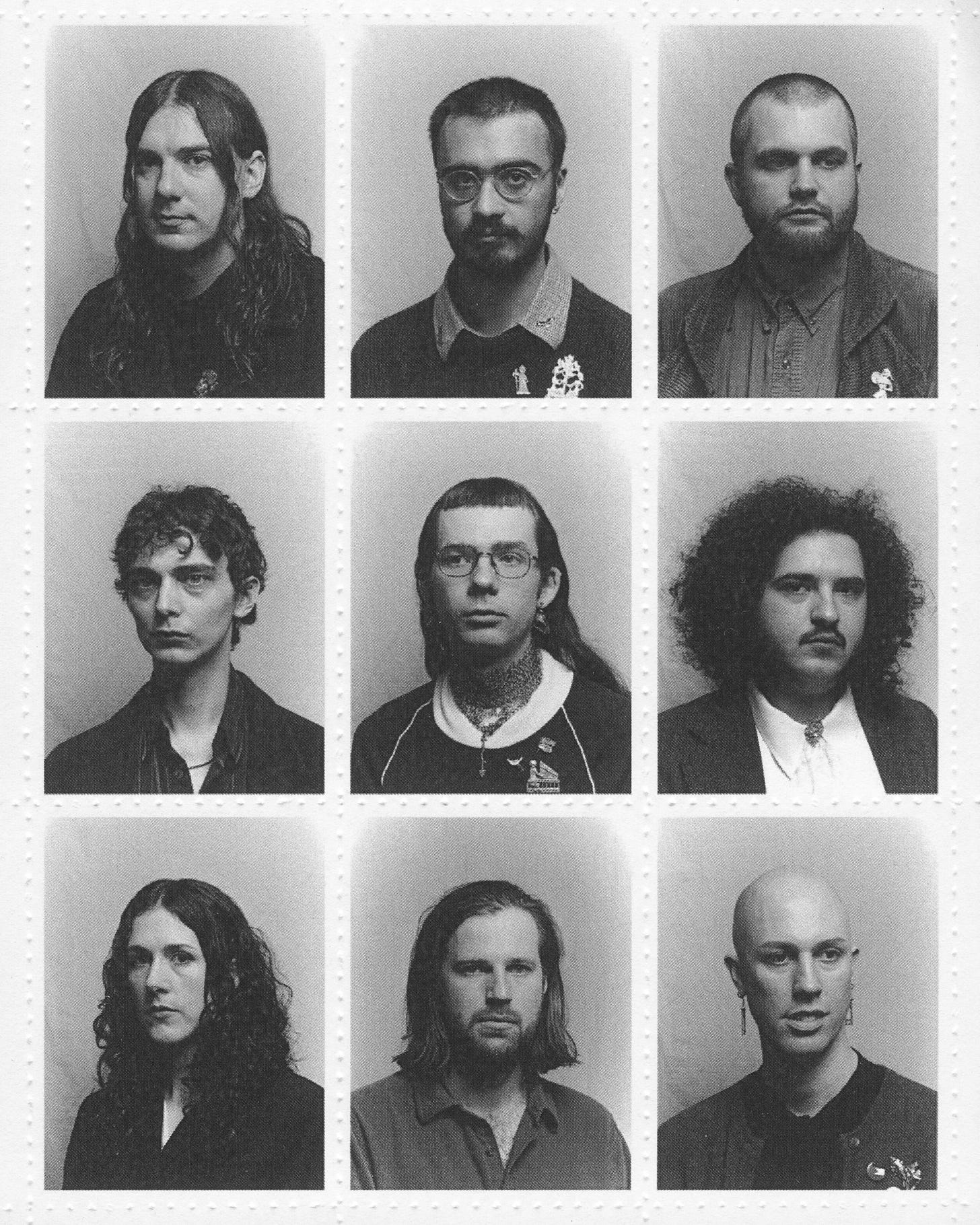

Shovel Dance Collective

Shovel Dance Collective is a folk-music nonet from the United Kingdom. In their work, they take traditional English folk music and push it into the future, tangling up centuries in the process. On The Water Is the Shovel of the Shore, the group’s 2022 LP, they put together something of a collage of traditional work songs, shanties, and field recordings. Alongside their more straightforward work, they have released Offcuts and Oddities and Offcuts and Oddities Vol. 2, two collections of sketches, rough drafts, and misshapen recordings taken from the cutting room floor. The Collective will release their latest LP, The Shovel Dance, on October 11th. It sees the group, as ever, treating folk music as a living, gnarled, and inherently political thing, as a product of communal joys and sorrows, and as something inextricably related to accrued histories. Michael McKinney spoke with four members of the group—Mataio Austin Dean, Jacken Elswyth, Daniel S. Evans, and Nick Granata—on September 4th, 2024 via Zoom to discuss their relationships to the histories of folk music and labor, singing along to Bruce Springsteen, reaching towards the sublime, and more.

Michael McKinney: Thank you all for making the time. How are y’all doing today?

Nick Granata: Good. Tired. (laughs). I had a quite folky evening last night with Dan[iel S. Evans] and some goblins (laughs)—some real-life goblins. I had the policy of pretending that I wasn’t going to go to work today, which I was regretting when I woke up this morning. But it was very nice: lots of singing.

Jacken Elswyth: I ended up not going to that because I knew that I had work; I failed to make that policy. It looked really good from what I saw—I liked the Instagram stories.

Nick Granata: It was a nice sort of medieval-tavern evening.

I’d love to hear about it if you’re comfortable sharing.

Nick Granata: Yeah, I mean, it’s exactly that. There’s this band: Goblin Band. They’re great—they’re another folk band on the scene in London. They really inhabit it in their whole life. They dress the folk way (laughs). I’d say I do a little bit as well, but not [to that extent]—they look great. It was one of their birthdays last night—Rowan [Gatherer]’s birthday. We aged the pub with our presence (laughs). It’s like going into a time machine.

Daniel S. Evans: Me and Seth [Randall-Goddard] spent a part of it not participating in the singing, but looking at the bar staff who were growing more and more tired of what was actually occurring (laughs).

Nick Granata: Oh, really! There’s kind of a “no music” policy at Sam Smith’s, but I think we barged through (laughs).

Daniel S. Evans: It’s a particularly liberal Sam Smith’s, I would say. For context: Sam Smith’s is a chain of pubs in Britain that basically only serve Sam Smith’s beer. They have a very strict no phones, no laptop, no playing music, and sometimes no dog policy. But this one happens to be run by ex-art students, so it’s a slightly more liberal rendition on the Sam Smith’s formula. But it’s very cheap—that’s very important (laughs).

I’m envious. That sounds like a riot. I generally like to start interviews by rolling the clock back as far as I can go. I’m curious: on an individual level, or perhaps as a group, what is some of the first art you remember really connecting with?

Daniel S. Evans: I can try my best. “First art I ever connected with”—whoa. That’s, like, the best interview question I think I’ve ever got.

I appreciate it.

Daniel S. Evans: I got asked this question not that long ago, and my answer was: when I was like nine or ten my granddad had loads of CDs, but he didn’t really listen to them anymore, so my parents just took them all. A lot of them were classical music CDs. You know Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana,” the really epic one? I listened to that and I was so obsessed with it. It was in the old Excalibur film and, basically, that was the moment where I was like, “Oh my God. Music can be so amazing.”

Apparently, my parents were really worried that I was going to be a massive boring classical-music nerd because the first thing I got into was that, and I was listening to it all the time. Then I discovered Iron Maiden maybe three years later, and that was probably more of a revelation for me: the Iron Maiden moment. That started a whole chain: it was Iron Maiden, then increasingly extreme metal, and then I pared myself back to Radiohead. That was the journey: from Iron Maiden all the way through to black metal, and then I was 16, I was like, “I’m gonna go full classic ‘what 16 year olds listen to’ and listen to Kid A and stuff.”

Jacken Elswyth: I think mine was going to be a CD as well. I feel like the first CD that I remember feeling ownership over—I don’t know whether it actually was mine, but I definitely thought of it as mine—was The Best of the Pogues, which is a quite appropriately folk-ish answer as well. That’s probably when I was about seven or eight. I remember putting that on and dancing around the living room a lot.

Nick Granata: I was doing the washing up just yesterday, and you know that Victorian song—(singing) “My bonnie lies over the ocean?” (laughs). That got into my head whilst I was doing the washing up, and this probably isn’t the moment that I would want to say (laughs), but when I was singing that to myself I was remembering that we had a Victorian day at school. We dressed up like Victorian children, and we’d go to this really old house and pretend we were Victorians for the day. We learned loads of old songs.

I was just thinking about how into that I got and how beautiful that melody is (laughs). I thought maybe that was a pivotal moment. I wore my granddad’s flat cap for that. I didn’t take it off for, like, months (laughs). I was inhabiting that music and history. I was thinking, “Maybe that’s why I like folk music so much: because of that moment.”

Maybe the cooler answer would be: my brother trained me to like music (laughs). We’d sit and he’d show me stuff—Radiohead, again—and we’d listen deeply. He’d ask me loads of questions about it, and he always really listened and made me think that what I said was interesting. It was a while into that before I started listening for myself.

So he taught you a language of deep listening, basically.

Nick Granata: Yeah, I think so. He was always so enthusiastic, and he really wanted to know what I thought. He’d speak so passionately to me: “Did you hear that?!” And he’d say how it made him feel. He’s very honest, and he made me feel comfortable speaking about how much I enjoy music.

I was in the pub yesterday. They had a jukebox and I was thinking about this thing when you go through the effort, when you’re with people, to put something on and you’re all listening to it, and it’s finite, and how fucking amazing that is (laughs). And they put on The Boss (laughs). It was perfect. They’re singing along, I’m singing along. It’s the same when you do spontaneous karaoke: you’re like, “Music is so great!” It’s not just washing over you. A lot of the time it kind of is: I’m researching or letting something wash over me. These moments where you really deeply enjoy it—that’s what I’m always reaching for from my youth (laughs).

I wasn’t going to go there this quickly, but let’s go for it. You say you’re reaching towards what sounds to me a communal musical approach, where you’re with people, and you are fully in that moment. Is that a fair way to characterize that?

Nick Granata: Yeah.

There’s a part of me that wants to connect that to folk-music tradition: music of a people as compared to music of a person. I’m not certain if that’s me editorializing or not.

Daniel S. Evans: I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently. It’s in my own head so it’s not very well formed, but basically what you say is true. That experience of music as a collective endeavor—whether that be playing or sharing music with people, whether it be recorded or otherwise. It’s a kind of process: “Holy shit! This is amazing!” I don’t do that as much now that I’m older, but I kind of wish I did.

I guess the reason I’ve been thinking about it is because I’ve been thinking a lot about how I think it would be, in some ways, wrong to say that only folk music offers that. The joy of all music is that it offers that experience. The interesting thing about talking about folk music is: you can so often end up talking about it as a kind of history, but it’s such a good vessel for talking about it as a communal experience. It’s a perfect encapsulation of it, you know?

Sometimes when you start talking about someone who wrote [a song], or pop stars, or figures—the artist—it can block the conversation about this communality. But music is the perfect vessel for discussing that kind of momentary collective experience. The pub experience last night—the joy and euphoria of experiencing lots of people singing—is really unrivaled. It’s akin to showing your friends Bruce Springsteen in some ways. But music is so much more on the nose in the way that you can talk about it, you know? It’s easier to wrap it all up somehow.

Jacken Elswyth: Yeah. The thing that all of Shovel Dance [Collective] circles around is whether folk music makes that shared affect—this kind of collective experience—easier to recognize, whether that’s something inherent in the musical form itself, or in the way that you participate in it, or whether it’s something more intangible in our associated meanings with this music. I still don’t know which side of the fence I sit on, but maybe it doesn’t really matter.

At a certain point, it’s: does it become more of an intellectual exercise than an actual felt thing?

Jacken Elswyth: Or whether the felt thing comes from something intellectual, whether that’s conscious or unconscious, or whether it comes from something that’s carried directly in these melodies themselves.

Nick Granata: There’s maybe a cultural understanding of the melodies that could be recognized as nostalgic or instantly effective, I suppose. I’ve had people come up to me after shows like, “It reminded me of things that my granddad would sing to me.” Sometimes, but not often, I get people saying, “I recognize that song.” It’s a recognizing of the melody and the feeling.

I was thinking as well about the effect it has on a listener, especially if you’re a musician—or not even a musician, but someone who would want to sing or play these songs—about what the effect is of telling that person, “When you hear this song, you can also reproduce it, and it will be yours as well as ours.” That switch in your brain makes you listen in a different way. It definitely does [for] me. I remember that happening, and it started a snowball effect because everything becomes quite vivid when you’re listening to it—you want to grab every little bit of it in case you want to sing it again (laughs).

Jacken Elswyth: Nick, I remember you saying that in a bit of stage chat: “This song was gifted to me, and I gift it to you.” I really love that image of continuous re-gifting as essential to what makes “traditional music” traditional. I think if you feel like you’re being gifted a tune or a song, then you engage with it differently in the moment of performance as well as afterwards.

Do you feel any sort of tension between gifting and re-creation? I’m thinking about how, in so much of your music, you take existing forms and you rearrange them or put them in conversation with each other. Is that of a piece with the tradition of sharing this work?

Daniel S. Evans: We never say this, but there’s this characterization from other people of an almost destructive wish. Not overtly, but it’s like, “We’re kind of reconstructing.” I completely see the process as [being] in cooperation with traditional music as a form because, as Nick says, you’re constantly in this process of open discussion with people who have sung the songs or played the melodies before. I think we’ve only as a band been able to articulate this in the past year or two, but the real tension for me is [that] feeling: the collective feeling of spontaneously singing or playing with other people—or just sharing music with each other—is hard, as an affect, to capture as an arrangement or live show that you play all the time as a single entity. Or, indeed, to encapsulate as a recording.

That being said, the obvious way is that you just record the thing happening. And that’s not what we’re doing, so we’re making a very conscious choice there. I guess that’s the intriguing tension: how do you still reach for the same things that make traditional music traditional music, but in slightly different ways? [From that,] you get interesting and emergent tactics that, to me, are fun: “What if this happened to affect this?” It’s speculative; it’s not overtly destructive, or attempting to reconstruct in some kind of “We are the new vanguard of folk music” [sort of way]. It’s entirely concurrent with the processes, but it also makes it anew.

Jacken Elswyth: There’s something astute there: talking about it as tactics. Maybe the contradiction that is being addressed is not in the way that we, as musicians, treat these songs and tunes that we’ve been gifted, but there’s a tension that’s introduced by recording and distribution technology. It changes the method by which this music is gifted.

It means it’s often gifted in this depersonalized way, outside of direct communication. I don’t want to state that too strongly because impersonal communication of this stuff has always occurred, with broadsides or whatever, but that’s significantly intensified. When you can just go to Spotify and stream us, finding a tactic to recreate the sense of being in a room with someone singing this song to you may heighten its affective impact. Maybe it’s a way of navigating that tension rather than introducing a new tension.

Daniel S. Evans: I feel like there’s honesty in the tactic. When you get a recording of folk music that’s crackly or otherwise very obviously mediated through place and recording technology, or you get recordings of people playing that are kind of janky or wonky or, in some way, reflect some of the aesthetics that maybe we know from other musics we listen to, it would be dishonest to listen to it and imagine what we perceive as the unmediated and perfect [thing] that happened. What I think we’re actually doing is we’re going, “Well, this is how we’re receiving it,” and we’re looking at every single bit of how we’re receiving it. Not just this imagined form: as if all folk music that we receive is in this personal vernacular transmissive process. Which, obviously, isn’t the case for us now. But that’s actually a very productive process in itself.

You’re making me think of the Offcuts and Oddities releases. Might those be one way of complicating the recording as the medium?

Daniel S. Evans: I feel Offcuts and Oddities are the most high-concept stuff we’ve ever done, even [in] its jankiness (laughs).

Jacken Elswyth: Maybe the only real concept in the Offcuts and Oddities thing is openness to fragmentary accidents: allowing stuff that was captured without much thought. So it does recreate this immediacy of field recording or whatever.

Nick Granata: I was just thinking about how you respect material, and this is something that I think about a lot. I guess there’s a lot of talk about how you do that (laughs). I’m thinking about all the ways that folk songs come to us, and those mistakes that Jacken was just talking about being one part of that creation. With Offcuts and Oddities, I guess that’s putting a spotlight on the mistakes, the forgetting of words, the changing it up as you go, as a kind of happy accident.

That’s one aspect, and then there’s actual agency. That’s a really important thing about respecting material: You have to respect that there’s been many hands on these songs, and innovation. It’s this tension between innovation and tradition, I suppose: The fight between those two things is what makes it. [We’re] trying to embrace all of the little things that go into making a folk song, mistakes and all.

Daniel S. Evans: It’s almost a rejection, also: there’s never a full stop on an arrangement or a version of a piece of folk music, I feel. We always said the second Offcuts and Oddities is just showing the working. Our live shows and, increasingly, the recorded life of the band, I feel, has become so preoccupied with our collective interest in attempting to produce big, sublime textures: deeply emotional waves of stuff. The Offcuts and Oddities thing not only provides a place to put all the things we do to build up those arrangements and experiments, but also to acknowledge the history of field recording and the mediation of recording technologies in the way we imagine folk music. But, also, there’s freaky sounds that we quite like from folk music, you know?

I always remember—who was the guy who did “The Fox Chase?” Eddie Fury? The first time I put that on the chat everyone was like, “Holy shit, it sounds like Evan Parker! What the fuck?” But it’s trad! I feel like that excitement at the potential of those two things coming together, but without having to come up with these crazy big arrangements, is really exciting.

You’ve mentioned two sides of a coin here: showing your sketchbook on one and the stuff that’s preoccupied with big builds on the other. You also said “sublime,” which makes me think of ancient religious art. I’m not sure if that’s what you’re trying to gesture towards or not, but talking about music that tries to really. I’m curious as to where that interest comes from.

Daniel S. Evans: I realized Mataio [Austin Dean] just joined, and in some ways, it’s kind of perfect timing for that.

Mataio Austin Dean: Hello. I realize I must be a disembodied voice, but it’s very difficult to dial on to this call because you have to type the number very, very quickly, but it’s very, very long. If you don’t do it quick enough, they just say: “Goodbye!” But, yes, hello.

Daniel S. Evans: We were just talking about the sublime and the nature of the band, which, I was like, “That feels like perfect Mataio territory, somehow.”

Mataio Austin Dean: What was the first word you said?

Daniel S. Evans: “Sublime.”

Mataio Austin Dean: Ah, the sublime. Yes. It’s funny: I just had Robin [a friend of Mataio’s] here, and I was talking about the landscape that one feels like one enters when singing some of these songs: a landscape peopled by all these dead people. It often sounds cheesy, but I feel entering this kind of vortex created by the song is a real thing for me. I remember Gwenna [Harman, a member of Goblin Band] saying “the phantasmagorical other.” There’s lots of different others there could be. It’s a kind of sublime, I suppose, being faced by this large edifice of the past and generations no longer with us: the large sublime edifice of the dead. We often talk about intertemporal [and] intergenerational communing through song, which feels like an interesting way to think about the sublime.

Also, I was just talking to Robin about when I first came across “The Shepherd of the Downs.” For me it was this big moment because this is a song about a landscape that I love and know. I was like, “What? I didn’t know there was music from here.” That was also a sublime interrelation with the landscape. Ever since then, I’ve sung those kinds of songs of the downs. I’ve got feelings about that which I suppose you could link to the sublime.

Jacken Elswyth: That’s a great answer. That’s the kind of thing that I would have reached for but would have managed less poetically. If we reject borders in tradition, it’s important to widen the scope of what you’re reaching for. So you’re not just reaching for the parochial and the local, you’re connecting through specific histories to something much more general: a totality. To me, that would be an element of the sublime that we reach for. It has to be as wide open as possible.

Daniel S. Evans: Sometimes, the inheritance of folk music feels so vast and ginormous in scale. When we’re self-describing as sublime in the colloquial sense, that’s like saying, “We’re really great,” but it’s specifically meant in that romantic sense of something feeling so vast that the only way you can deal with it is to evoke its vastness. But that process of evoking its vastness can be very—it’s these hand movements that you won’t be able to capture. Just—ugh! You know? (clenches and shakes fists) (laughs).

I’m curious about that intergenerational conversation. What I hear in your material is a deliberate scrambling of centuries, rather than a straightforward “Here’s something from this time period; now here’s something from this; now here’s something from this.” You make a jigsaw puzzle out of it. Does that track? Where does that come from in your work?

Nick Granata: I think it tracks, yeah. I was thinking about churches (laughs). One great thing about a lot of churches in the UK is you’ll have an enormous wall in the back, and Victorian stained glass if you’re lucky, and all these quite modern things. Maybe that’s a good analogy, maybe I’m reaching. I feel like when I first got into folk music I was looking up: “What’s the oldest folk song ever?” Maybe to begin with, the appeal is this antiquity thing, or something coming to you as a whole. But then you realize it is like the church and it’s so much more complicated than that. A lot of the joy is in that complication, and the different ways the different stories that a song has gone through. Sometimes you’re looking for a song that’s fallen out of fashion, and some would say there’s no point then because the people decided, “No.” But we have our concerns; occasionally, we’ll find a song that fell out of fashion which concerns some people for whom the theme was important.

Mataio Austin Dean: I like the analogy of the church. The idea of the people choosing is interesting as well because something that we’re doing is we’re making our own judgments about that. We’ve been having discussions in the discussion group that Jacken runs about the history of all these processes. When we say “The people chose,” sometimes they were maybe made or encouraged to choose by social forces. We were talking at one point about how imperial culture—imperial kitsch—replaced the focus on culture in England in a way they didn’t in Scotland. There’s all these historical and political processes that we’re trying to intervene with in some way, or comment on as anti-imperialists.

That question made me think about soup. I’m always interested in time as soup, and mixing things together: intertemporality as a rejection of bourgeois historiography, and history, and linear time. That’s that whole thing—what is it? “No jails, no cops, no linear fucking time?” I’m into all that and the writing that’s been done around that. But it’s complicated because, obviously, capitalism has a history. It’s important to acknowledge that history and look at what’s changed and what can develop.

We also have a commitment to specificity as well as mixing things up. We do also make a point of being particular about the facts and pointing out time periods where that’s relevant. I’m thinking of “Old Captain Avery.” It’s important that there’s a 17th-century vibe rather than an 18th-century vibe when we’re talking about that; that song comes out of the early colonial time in the 17th century, where capitalist empires are being built [and] capitalism is really developing. There are specificities. Even in the little blurbs that we do—something coming from a march or a jig—these specificities are important, as well as this intertemporal scrambling. I hope we get the balance right.

Daniel S. Evans: I think it’s one of the most productive tensions of the band—this tension between this jigsaw or this soup, of time that we’re producing. It’s a rejection of a linear temporal silver arrow. It’s kind of funny how specific folk songs can be. Even though we think of them as being very general, and as the music of a swath of people, they can actually be incredibly specific in their discussions. That is also a tension, and it’s a tension that produces a lot of the effect of folk music: they exist in both the general and particular at the same time.

In a previous conversation the group ran, a member of Shovel Dance Collective mentioned your relationship to folk music as a kind of preservationism: of holding onto histories before their practitioners pass away. Did I read this relationship correctly? If so, what are you trying to preserve? Why these histories?

Nick Granata: It’s interesting. I used to say this isn’t an archaeological project. I used to kind of think—and I kind of still do—that the job of preserving these things has been done. But it’s a thing that requires renewal, always (laughs). Indulge me—to quote Walter Benjamin (laughs), I was reading his theses on history. I’m not sure if I fully grasped it (laughs), but my understanding was that a rigid and dogmatic view of the archive, or of the dead, will eventually end up serving a ruling class. The other thing that rings true is: the work isn’t quite done, but the method of preservation comes into it. To preserve a folk song, the folk methodology means that you can’t put it in your pocket or put it on a shelf. It’s a living thing. The enactment of folk music is how you preserve it; the folk method isn’t static. To “folk,” you must change.

Jacken Elswyth: Maybe it’s less a kind of direct preservation and more a drawing forward of particular things that we, within our current conjecture, find useful or hopeful within these fragments of prior experience.

Daniel S. Evans: It’s the ultimate assumption of this deep capitalistic thinking about history: that you can dredge it out, and then it dies as this kind of object that you’ve modified. “This is folk music now; we’ve made history. We’ve understood the material culture that we have.”

Mataio Austin Dean: I like this idea—I think you said “drawing it forward.” It’s like a cart that you have to constantly be pulling forwards, or just in a direction. Because it needs, as you say, this renewal. I’m also now thinking about [Walter] Benjamin because Nick mentioned him. I think he’s the best writer who manages to talk very abstractly about things, but his process of writing encapsulates the thing he’s talking about. It’s in motion always; he does what he says through his academic text. I can’t actually describe how he does it—it’s a very strange thing that he does. That process is also how you should approach folk music as a material culture. You need to be drawing it through the doing of the thing. That might not necessarily always make it fully clearer, but it is making it more of whatever the “now” is.

Jacken Elswyth: “I have nothing to say; only things to show.” (laughs). From The Arcades Project.

Mataio Austin Dean: I haven’t gotten to that bit. I was gonna say that with The Arcades Project, he’s doing what he’s saying, which is so rare and special, and one of the things I love about him. The Arcades Project has whole sections that repeat themselves, but just slightly differently. It’s truly non-linear in the way that it’s compiled, and you can feel the sense of it being a folder with all these things interleaved through it: repeating themselves, coming in and out.

There’s also the Benjaminian thing about a flash: about history coming up as a flash, as [a] fragmentary thing. I find that a helpful way of thinking about folk songs as well as a historical methodology. What’s that Benjamin quote you just gave, Jacken? Was he talking about folk songs?

Jacken Elswyth: No, no. He’s just describing his method.

Nick Granata: We’re really outing ourselves as the Benjaminian folk band (laughter).

Mataio Austin Dean: I’m well up for that label.

When you as a collective are approaching your songbook, how much of that is about taking something and saying, “What do we want to do to this?” and how much of it is about submitting yourself to the histories?

Daniel S. Evans: Do you mean in the production of the arrangement of the music?

Yeah. We spoke a bit about this before, about this music being tethered to its own histories, but I’m curious about going deeper on that.

Daniel S. Evans: It’s always difficult to talk about. The simple way to answer it is through negation. We’re not overtly saying, “This is about this thing, so we’ve got to make it sound like this thing.” This is the interesting way in which words or narratives, if we’re talking specifically about songs, interact with the music as a set of musical material. If it’s a song, that’s basically all you’ve got: a rhythm and the melody. That has a micro-narrative that is trying to inform the macro-narrative—the whole story. But, to me, you can never understand that as soon as the melody is put in front of you. It has to happen to me many, many times. I have to understand it many, many times in order to understand how it moves.

I feel like we’re always doing that together; it’s often a very long process of understanding this micro-relationship between melody and narrative, and how you can use those two things and build on them to accentuate the feeling. It’s really hard to talk about—I feel like I’m actually saying nothing.

I understand that to a certain extent. I’ve worked in improvised music, and articulating those moments is really challenging.

Nick Granata: I’m trying to think of what actually happens when we’re in rehearsal. I guess we do talk a lot—there’s a mixture of playing and talking. We’re not necessarily talking about narrative; most of the time, it is about arrangement. But I think we enjoy each other very much as well, and we trust each other. We try to play with each other a lot. I guess that relates to our structure because everyone has a say, which is great and tiring and amazing.

Jacken Elswyth: [Shovel Dance Collective member] Fidelma [Hanrahan] wrote up a bit of this process for another interview recently, and I thought she described it really nicely. As an individual, you can’t be too precious about this or that. There’s little groups of us that practice—whoever’s free on whichever day—and then you come back a couple of weeks later and discover that the whole thing shifted one way or the other. It’s one of those things that I think of as Ouija-board action. We collectively end up where we end up without anybody giving too strong of a push this way or that way.

Mataio Austin Dean: It just feels like it happens. It always feels amazingly organic and effortlessly communal. I think that’s just how we work. I suppose it’s taken us a while to get to this point where things can be done in this intuitive way. We all know each other so well, and we all know what’s going on and how it works, so it just sort of happens. But maybe it took a while to get to that place. I don’t really think of it like that; I kind of feel like it was always like that. Maybe it wasn’t, but it definitely is now.

Daniel S. Evans: You referenced improvised music. It’s a reference for lots of us, and lots of us do free improv together, but that as a process is very interesting because it’s not like you’re arranging by numbers and saying, “This is the song, it goes to the IV here, and then the V here, and then we go minor here.” When you’re improvising with someone or with a group of people, it’s this process of putting something out there and someone joining or pushing back, and never being precious enough to not change what you’re doing in real time. It’s this constant process of negotiation that is happening without talking about it. The joy of free improv, specifically, is that almost anything goes.

The Shovel Dance method, increasingly, is: although sometimes people might say, “That’s a crazy idea,” I think we’re often quite willing to pull out anything musically because we have quite a big toolbox of what we could do to accentuate a texture or a sound. That applies to all of us. It is often this process: “What if we did this thing?” It’s just trying out everything and negotiating it. But as Mataio says, it has an intuitiveness. When we all think it’s good, we can tell. It just slots into place; the negotiation just works. It’s a really long version of what you do when you’re improvising, kind of. We have a wide understanding of what could happen in that space, which I think is part of what makes us.

How do you set parameters for your own work? If you say it’s such a wide possibility space, is it you come into it saying, “We really want to play with field recordings” or “We want to focus on tunes that are thematically related to this idea?” What does the funneling look like in your work, if it exists?

Jacken Elswyth: If it exists, I think it’s by that same long negotiation. It’s very often unspoken; things get arranged or dropped. Sometimes that’s by collective decision—we decide it doesn’t work, and somebody states that. Sometimes nobody states it at all—things just don’t get returned to.

Nick Granata: With The Water Is the Shovel of the Shore, that was major funneling (laughs). But it’s quite an easy funneling because we already had quite a lot of material that was concerned with the water. It relates a bit to: what are the limits? It’s certainly something you can be criticized about in this world: where do you draw from? I feel like my current position (laughs) is—well, I think it’s a complicated thing, but there’s a mixture of, do I understand it? Can I sing it? Do I understand it in a deep way? That’s quite vague, but there’s various interpretations of what that is. As a folk band, I’d say we’re pretty unfunneled in that sense—we play a wide range of things from different places about different topics. I think they are ultimately funneled by our shared experience, and you’ve got to stay true to that.

To zoom out: I’m curious about your relationship with labor, whether that’s about jobs and ways of living, or about labor as an organized movement. I think about how much of your work is, lyrically, about work. I’m curious as to how that fits into “now,” whatever that means.

Mataio Austin Dean: That’s a big one. That’s a big one.

Nick Granata: I was recently doing some work for my master’s degree that was quite concerned with this and with work songs. It links a little bit to what we were talking about earlier, this specific linking. We play a song called “Jowl, Jowl and Listen.” That’s full of jargon about mining. Personally, I’m about as far from mining (laughs)—I’m an art technician. Creating this link, the struggle is very different, but not for everyone in the world. People are still dying at work in this country and everywhere. Their struggle is our struggle, and that’s certainly one part of it. With the way labor is organized now, you can see it quite clearly. Especially in sea songs, you can see quite clearly how this has happened (laughs).

This is the thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot for a couple of years: the relationship between song and time. Songs are used for work during work, and they can make time go quicker, but they’re also a tool to keep you working in time. It’s a tool of efficiency. This kind of dialectic between the liberatory and—I don’t know, controlling? Before the people who did a lot of these jobs were replaced by machines, this was a technology of labor. This was machine time.

Jacken Elswyth: I remember when we were writing the essay that accompanies the Water album. We had this long conversation about shanties and about the point that Nick was just making—the way that songs are a technology of discipline, and also a way of looking beyond [and] finding a moment of joy. We don’t tend to play, you know, the folk-song bangers of the trade union movement. For me, the way that Shovel Dance addresses itself to the class struggle is less in making these overt appeals to the history of organized labor, and more to finding value in everydayness. The stuff that we perform addresses itself to struggle, and grief, and loss within the everyday. But [it] also finds those moments of joy, as well. That’s one of the things that’s most powerful about traditional folk in total for me: the way that it holds this spark of excess that’s located very resolutely within everyday experience, but also gestures beyond our own conditions. I guess that’s back to reaching the sublime. But maybe that’s the politics that lie within that reach towards the sublime.

Nick Granata: That’s so well put. It’s beautiful.

Daniel S. Evans: Very well put. When we’re pulling the folk-music cart into the current moment we’re in, there’s a strange position that all these labor songs inhabit. They articulate material conditions of the people in the songs that are obviously horrific a lot of the time: material conditions of work that are horrific and that, in some ways, we connect to because we fucking hate work. Loads of people that I know just fucking hate going to work because it sucks and it’s horrible. We all understand that to be true. It articulates that, but it also simultaneously articulates a very acute solidarity and sense of identity and community around this labor that I also identify as being overtly dangerous and horrible.

That is a very interesting relationship we have now to those songs. We are part of the same struggle, but I think it would be wrong to sing them imagining that you’re indebted into the same kind of unionized [and] single work—like a miner union, for example. Work has become so much more divided and striated now. Relating to that now is very interesting because it is fundamentally the same struggle, but the situation has changed. That jigsawing soup is a very good way of understanding the retention and solidarity in those things. It’s a very interesting way of relating to people who once lived because you can both identify and not identify with it. In that, it’s a very good way of showing how things have changed but also how we must continue the same fight.

Mataio Austin Dean: What you’re saying made me think about the conversation I had with Robin: about what Marx says about this subjectification of labor, human intention, and natural labor. In a lot of what Marx says, there’s this interaction with the history of humanity being a history of labor of different kinds. This idea has been floated and rejected and claimed so many times: folk songs as not just the music of the working class, but as a political tool of the working class. I get that lots of people are ambivalent about it, but I still back it because at a time like now, where labor has become so much more striated and complicated and essentially obfuscated, I think a cultural thing which makes claims on class politics—specifically in relation to a politics of labor rather than superficial things that people can come to attach to class—is important. I think that what Jacken says about the everyday—it was really beautiful because that is a key example of it.

Earlier, I was asked a similar question about these contradictions that you can point to within the superstructure as it comes off the base structure. Or you can look at the contradictions within the base structure. It’s an inherently contradictory dialectical thing, but essentially, the everyday experiences and the communal and intergenerational memories that are held in the songs of these struggles of different kinds—that’s what we try to address in our music. It’s a range of experiences, but it’s there, and it’s united by class power. I think that’s important. Even if it’s not explicitly “the songs of organized labor,” they are the songs of labor.

Even if it’s not a formal songbook, inasmuch as there is one for organized labor, it is still represented in that space.

Jacken Elswyth: Yeah. It’s enacting collective solidarity in that experience. That folk and traditional music experience of participatory music is one of collective solidarity. You don’t have to be singing “Solidarity Forever” to get that feeling, as great as “Solidarity Forever” is.

Were these questions coming into this LP explicitly? Tell me about your mindset coming into it.

Daniel S. Evans: It’s kind of the album by default, I suppose. It’s like, we’ve been a band for five years now. In those five years we’d arranged many different tracks and got the ones that we really liked and we felt encapsulated us. Simultaneously, we’d done Offcuts and Oddities, and that EP, and The Water Is the Shovel of the Shore. I suppose it felt like, you do what bands do: you make a studio album of those tracks.

Jacken Elswyth: I feel like this is talking it down.

Daniel S. Evans: It isn’t talking it down! No, no, no! I think it’s great. I don’t want to go into it, like—

Jacken Elswyth: (slowly, with faux resignation) We had to do it (laughs).

Daniel S. Evans: I don’t want to go into it like—obviously, with The Water Is the Shovel of the Shore, we went in with this thought. I don’t think that’s putting it down because I don’t think an album needs to have… it’s like a photo album. It doesn’t need to have a prior thing before to be a collection of someone’s life up to that point. I think in some ways, that’s the greatest service I can do for the record: it’s an encapsulation of what we see as the most genuine reflection of us, as we have existed in our everyday life as a band thus far. In some ways, it’s not about anything, apart from everything we’ve previously talked about (laughs). But it was a learning process of how we might exist as a band on a record in the slightly more conventional sense, I suppose.

Jacken Elswyth: Yeah. If Offcuts and Oddities is us sharing our working, then this is showing the final product of our core process as a band. Again, Water was kind of tangential to our process because it was constructed with all of us as small groups or individuals rather than [via] full, collective force. So this is a way of attempting to capture that collective at its most polished.

Daniel S. Evans: I guess it’s funny for us because for most bands, you relate to your records like: “These are the songs we did here, and then a few years later, these are the next songs we did.” But because we’ve existed with these other weird field-recording experiment records for so long, it felt like a big moment. We kept saying that people would listen to us on record first, and then they could see us live and be like, “Wow, this is so different.” And vice versa. There’s a simultaneous stream of people who liked the recordings, and maybe we were worried they were disappointed by the live show. Or maybe they loved it as a surprise. And then vice versa. We had these dual existences. Although we see the whole thing and understand how it works together, they were quite distinct for a while. This is a kind of convergence of it all thus far.

This is something I like to ask near the end of my interviews: either individually or collectively, what is something you recently came to learn about yourselves?

Daniel S. Evans: That’s a hard question.

Nick Granata: I’m trying to think collectively because that’d be nice.

Jacken Elswyth: Recently, I’ve come to an appreciation of clarinets and bells (laughter).

Nick Granata: I just remembered something we discovered collectively. On the train the other day—well, actually, Jacken you weren’t there. A few people weren’t there. But I think we can speak to it for everyone. We were trying to think if we could pair any of us off into couples, and we discovered that we don’t think that any of us would work as a couple. It’s a really good sign about where we’re at as a group of friends because we didn’t all necessarily know each other as well when we first started. We’re all past the phase of wanting to fuck each other! (laughs). Now we’re like family. That’s how family works, isn’t it?

Daniel S. Evans: That’s some good advice: if you start a band, and you think you could date one of them, stop right there.

Nick Granata: Yeah. It’s beautiful—I really do see everyone as a little family now, which is a really amazing place to be at, so that’s one thing (laughs).

Mataio Austin Dean: Yeah. That and the clarinets and the bells.

Jacken Elswyth: There’s a mysterious message in the group chat I’ve been meaning to ask the meaning—it kind of relates to this question. The message is: “Do you remember the days when we all thought the lonely goat had a quiet voice? Look at us now.” What did that mean?

Daniel S. Evans: I think what it meant was: We played a gig recently. Alex [McKenzie] went back to our Premier Inn room and was singing—what’s the little goat song?

Nick Granata: (singing “The Lonely Goatherd” from The Sound of Music) Layee odl, layee odl layee-oo...

Daniel S. Evans: Yeah. I think it was a very abstract way of saying, “Look at where we are now, guys.” I actually looked at that message and I felt quite emotional, even though I didn’t know the context of it at the time.

Jacken Elswyth: I had the same feeling.

Daniel S. Evans: That encapsulates the sublime. It didn’t actually make any sense, but I saw it and I was like, “I know exactly what he means.”

The Shovel Dance Collective’s The Shovel Dance can be purchased at the American Dreams Bandcamp page.

Thank you for reading the 163rd issue of Tone Glow. All your group chats should capture that inexplicable sublime.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.