Tone Glow 126: Writers Panel & Recommendations Corner, 2/19/2024

Our Writers Panel on Murumba Pitch's 'Isidalo' and Rafael Toral's 'Spectral Evolution'. Also: Our Recommendations Corner on Chad VanGaalen's 'Full Moon Bummer'.

Writers Panel

For our Writers Panel, Tone Glow’s writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

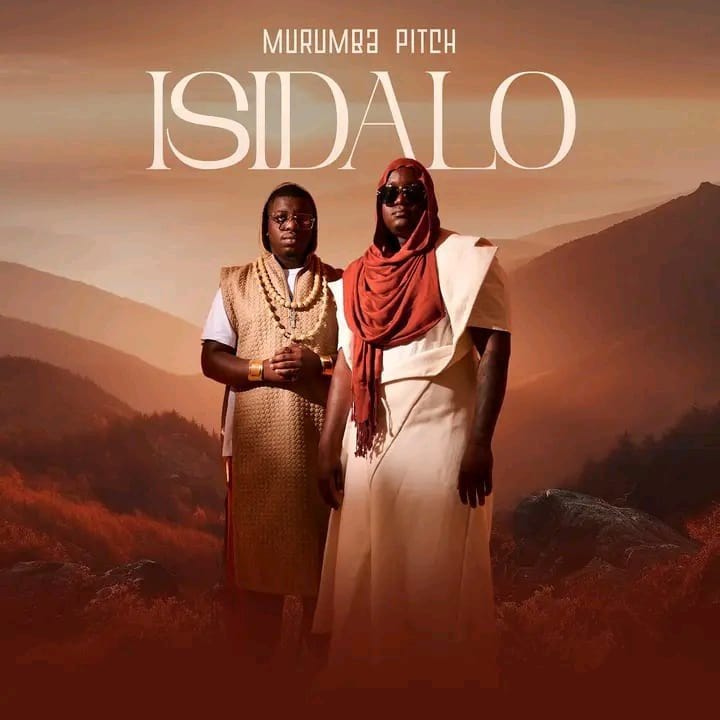

Murumba Pitch - Isidalo (self-released, 2024)

Press Release info: None.

Streaming/Purchase info: The album is available to stream and purchase from various websites here.

Marshall Gu: I can’t help but consider amapiano the anti-gqom. Starting around the same time that gqom was making waves internationally outside of South Africa, amapiano trades out gqom’s piledriving kick-drums for lusher loops, its stripped-down minimalism for richer textures, and slows down the tempo to soften up the beats. I like gqom, but I also can’t imagine listening to 108 minutes of it because the beat is often all there is to it. By contrast, listening to 108 minutes of amapiano turns out to be super easy. It’s a genre of luxury, reminiscent of city pop to me in that regard, making me think of poolside bars, pristine resorts, and the warm glow of an ever-orange sun.

Isidalo functions great as background house-as-ambient or texturally-sensual dance music depending on what level your volume knob is dialed to. A revolving door of collaborators helps distinguish these slippery percussion tones: a saxophone courtesy of Buhle Sax takes early highlight “Jabula” to its dizzying climax; Boohle straddles the line between pop and soul vocals on “Ngi Ready.” Such examples are sonic possibilities that are not available to—or simply not bothered with—in a lot of gqom. I wish some of the drum textures were more interesting, sensual as all of them are: “eWallet” has that strangely titillating extra syncopation that helps it stand out, but most of these other beats often feed into one another, leaving it to the collaborators to help distinguish the songs. Every song is long (only the intro is shorter than 5 minutes) because they have to be: after all, you never want the sun to go down when you’re at the resort pool.

[7]

Jude Noel: An early February evening that feels like late spring: I’m waiting on a matcha latte and for the first time in weeks, I feel rooted in the moment. I get that Isidalo’s meant to be party music, but somehow, it’s just the right soundtrack for standing beside the café counter, scoping out an empty space to place my laptop bag. There’s a liminality to Murumba Pitch’s production: Their chord progressions often exude a hint of sadness, exuding steamy, nocturnal atmosphere while leaving the topline melody unresolved. It’s grounding, but not instantly gratifying. Each component of the composition seems to be reaching for a closure or crescendo that just eludes its grasp, but this perpetual yearning is what makes Isidalo so potent. Little piano riffs flutter through the mix; singers drop in and drop verses; saxophonists noodle over the keys for a bit—the tracks serve as microcosms for lowkey kickbacks. There’s no linearity, just a vibe that morphs at an organic pace.

The record really starts to click for me when I get to “Ishisheli.” I love the subtle lift that the log drum provides every few bars and the chromatic percussion that spirals in the backdrop. The mix is gentle and warm, as is Mthunzi’s vocal performance—it’d be kind of cheesy if the sound weren’t so perfect. I can’t help but smile while listening. While it’d be tough to listen to this all the way through very often given its 2-hour runtime, the full experience of just letting Isidalo playwhile running errands or reading a book is nourishing. Lovely, lovely stuff.

[8]

Maxie Younger: Lately, I’ve taken to shuffling through a few songs off Isidalo on my morning commutes. I live in a college town, so traffic is fickle, but the music is a decent salve for the infuriating stop-start scoots down arterial roads I’m subjected to on occasion. Amapiano is a genre I’ve only lightly explored previously—usually accompanied by smiley DJs grooving in front of cityscapes and placid nature scenes—but the word that keeps coming to mind when I dip into this album is “alchemical.” Tracks craft precisely sun-bleached, spacious outcomes from a careful transmutation of evocative sounds: that signature husky, piercing log drum bass, soft kicks buried askew to the mix’s timbral center, loose shaker patterns that lilt forward to a distant vanishing point. It’s all imbued with a certain magic of predictability, of a pleasure center being mined again and again as pieces fall into place in just the way you expect them to; each successive song iterates on that familiarity like an actor delivering the same lines of a play on different nights.

What I’m saying in a roundabout way is that the sound here is pretty thoroughly dialed in, to the point where Isidalo feels more like a greatest hits compilation than a structured album: tracks that all come across as the best and brightest representatives from a cast of hundreds. This can be dull or liberating depending on your point of view. You’ll never wade into a bad or off-model song, but an active, back-to-back listen through all 102 minutes of megawatt glare quickly turns stultifying if it catches you in the wrong mood.

“Umoya” stands out the most to me, exploring the burgeoning 3-step genre with strident kicks that knock forcefully against zig-zagging sawtooth howls. The song’s rhythm forgoes the pliant naturalism that characterizes the rest of the album, earning forward motion through active intervention. The “missing kick” on the last count of every measure that breaks the easy groove of a 4/4 pulse—supplanted by syncopated snare hits—makes all the difference, invoking adrenalized tension as the track holds its breath before exhaling in feverish, propulsive ecstasy. It’s a nod to catalyzing trends that enriches its surroundings, positioning the album’s tracklist as a cluster of linked nodes in an evolving continuum of South African dance music.

[7]

Michael Hong: I’m typically apathetic to amapiano in album format: the songs are so extensive that these projects easily balloon into a daunting runtime, and the vocals are flattened into the floor of the arrangement to sound remote. This distance reminds me of traditional work song, which dictates how I listen, letting it bleed under the day-to-day humdrum. Through a soft background speaker, it’s like an unassuming ambient instrumental and feels designed to be layered with the sound of reality—the rattle and shake settling underneath the drip of a faucet or the whir of a computer fan. It’s easy to see why “Water” is the genre’s biggest pop moment: it’s not just the runtime, but that Tyla makes the song sound so immediate, whether it’s the chorus’ stacked choir, firm and direct, or the wispy melodies that trail through it.

Isidalo falls in line with the sunny easiness of amapiano—throw on any track and you’ll find something earthy, capacious, and muted. Mellowed-out vocals that sink into the arrangement, the sweet clatter of its flat percussion, and some metropolitan instrumentation that color within it, like dainty horns, pastel synths and quelled strings. The best moments of Isidalo cut through the sheen, to remind me that it isn’t meant to simply be environmental noise: guitar licks on “Basazolimala” are like liquid gold; a charming saxophone melody streams through “Jabula.” The female vocals on “Forever Yena” provide a much-needed counter to the duo’s low-end, lifting the rest of the arrangement so you can better view its dimensions: here, the drums plunk like beads of water in the hazy ambience as the voices demand a deeper connection. It’s the closest the duo comes to feeling immediate, like the heavy sweat under a starry sky. The same descriptors that have been used for amapiano remain applicable: pretty, peaceful, sweeping, spacious, etc. None of those words mean captivating—despite offering twenty-five percent more on “Follow Me,” with a quasi-rapped cadence and injecting a jolt of energy into their drums, this tension resembles the storm warning rather than the storm, but the calamity never materializes. While the duo can easily capture your attention with a stunning motif, Isidalo’s scale is so expansive that it’s just as easy for it to stray back into another ambient layer underneath the dull clicks of a keyboard.

[6]

Vincent Jenewein: One of the first South African deep house records I remember crossing over in a big way was Culoe De Song’s “Bright Forest,” released on Innervisions in 2009. Fifteen years later, it’s interesting to track the development of that sound into the genre that has become known as amapiano. To be clear, like most amapiano, Isidalo is not a house record. It’s straight pop. But it’s pop that is clearly coming from a lineage of deep house. Many of the hallmarks found in tracks like “Bright Forest” remain: the swirling acoustic percussion, the bright, reverb-drenched instruments and lush strings, the slow tempos and extended song lengths, the tidy production and spacious arrangements, the overall vibe of gentle jazzy melodrama.

In its transition to full-on pop, gone almost entirely however are the kick drums—so central to any kind of house—with the low-end instead driven by that ubiquitous LogDrum sound. Like in all pop, front and center are the vocals—layers and layers of reverb-drenched, AutoTuned and harmonized vocals, clearly influenced by the production of the American pop-trap sound of the 2010s. But comparatively, the performances here are gentler and more careful across the board, whistling and hushing, rather than crooning or screaming. The results are consistently delightful, for example on “Jabula” or “Ngawe,” songs that are just chock-full of that irresistible glutamate that is pop at its best.

I think the best word to describe the overall fee here is “lounge-y,” feeling like something you’d hear in the background of a beachfront restaurant on a summer evening. I find that interesting, because it’s just so antithetical to the more recent trajectory of mainstream American pop, so enamored with sonic pressure and violence, straining at the limit, demanding attention, any attention at all. Isidalo never yells at you. “Follow Me” is the most aggressive it ever gets, and it’s still rather lush, inviting and suggestive rather than making any kind of demand. Taking a wider perspective, perhaps this divergence is a testament to a difference in cultural unconsciousness.

In its form, this almost two-hour long record is clearly a product of the global Spotify era, more of a bundle of stuff than an album in the traditional post-war sense. After a while, like with that background beachfront playlist, all the songs on Isidalo start to blend together, a fact not helped by the uniformly slick and digital-sounding production that seems stuck in the late 2000s laptop-gloss of “Bright Forest.” So on one hand, I think this could’ve been a more memorable sounding record with more grit and hair, but on the other hand, the categorical lack of anything like that is also one of the most unique things about this record insofar as it is pop music. On a closing note, the dance music head in me also cannot help but wonder about—and mourn—the loss of the kick drum here. Is all music just ultimately destined to be swallowed up by the infinite, amorphous beast that is global pop?

[7]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Over the past half-decade, amapiano has spread throughout Africa and the rest of the world in countless ways, but the amapiano that is made by and for South Africans—the kind that has little concern for crossover appeal—still remains committed to the longform jam. It sits somewhere between pop music and dance music. Of course, these two styles can coexist, but their utility is often different, and can be understood through amapiano’s most notable features (at least on the softer side of the genre’s spectrum): long runtimes, extended passages without vocals, little care for urgency, albums that frequently run two or three hours long.

Like most amapiano albums, Isidalo feels like a DJ mix, and my favorite part about listening to this is that I’m often not entirely sure when a new song has started. The way everything bleeds together is the appeal, with the smallest details standing out in the process. By the time “Isisheli” comes on, it’s the subtle, flickering synth that hits me hardest; in contrast, “Balansa” has these constant pulses that force greater attention to the repetition of the log drum loop. At every moment, there is a magnification of these spare elements, but this is also the sort of music that is easy to luxuriate in. The vocalists make it easy. Boohle, one of my favorite singers in amapiano, sounds both forceful and elegant across “Ngi Ready.” Everyone on “Ngawe” finds a different way to make their vocal melodies sound fluid. The harmonies on 3-step highlight “Umoya” make the grandiosity feel congenial. It’s a constant embarrassment of riches, but it’s never flashy.

[6]

Frank Falisi: I like to think of house music as an actual container for us, an abode of us and all our sounds. We dwell here. This construct is where we reside for a while. A house is not containment, or at least it shouldn’t be; the sounds inside it change as we move in and out, as we bring new people into it. And keeping in mind the potential slippery reduction this simile of domiciles inspires, house music can be such a weigh and way station. We welcome and shift, pitch and assign new names to the air. To live in house music is to hear the wiggled air all the time. Four-on-the-floor over and over, protrude and sink away, repeat repeat repeat.

Repetition is the sound of the air we share. It’s in this respiration that mutations emerge. Amapiano is such an evolution. The sound existed before the name did. The name means—or seeks to mean—“the pianos” in IsiZulu, in IsiXhosa. It’s a reference to amapiano’s constancy and percussiveness, the hitting of a named thing (piano, log drum, saxophone) to reveal sound hanging around our bodies. The thrill that accompanies uncovery goes a long way to describing amapiano’s unique pulling at our bodies. We’re drawn into the sound and the house, where we meet each other. It’s in Tyla’s “Water” and Kabza De Small’s “Sponono,” the lilt of desire, the want of leaning into. It leads to Isidalo.

Murumba Pitch is a house, like amapiano, like a sound. Composed of Emmanuel Mathye and Khathutshelo Innocent Mangolo (Maeywon), the group centers on meeting and re-meeting, often over the course of long tracks and rising, falling sounds. Life is very long. Longing takes a while. It’s sweet and lulling, like “Inhlitiyo.” Sometimes it sounds like the backbeat doesn’t change. And then it spikes up like “Basazolimala,” protrusions of sweet-heat guitar and coo-vocals over a beat with just a little more oomph on the ‘AND.’ It’s the word for how the parts fit, ‘and.’ It’s how “Follow Me” rides a tumbling percussion, builds into itself amid an album that sometimes feels like one long session in a house, one long meeting. We don’t always have a distinct name for the sounds. Sometimes I don’t know where one song ends and another starts. And with deference again granted for the slippery pull of figurative language: sometimes I don’t know where one of us ends and the other one starts. If we repeat and then repeat, we may find such distinctions less vital than ever.

[7]

H.D. Angel: Kabza De Small’s “Isoka” entered my rotation in 2022 and hasn’t left it since. It features two of my favorite amapiano vocalists, Nkosazana Daughter and Murumba Pitch’s Maeywon, in an undeniable man/woman duet. They both have that ineffable sense of character that all the classic deep house singers do, where it feels like they were born for their genre, destined to channel lightning-in-a-bottle feelings on seven-minute club records. As their voices curl around the ebb and flow of the panoramic percussion, Kabza doles out intrigue carefully. There’s a tentativeness to the log drums that come in between the verses, like they’re waiting for a crowd to wrest control of the song’s meaning; each piano chord feels like it could mark either the start or end of a relationship. It’s a song that’s both delicate and rugged, depending on how the light hits it, and it captures everything I love about amapiano.

As a monolingual North Carolinian college student below the legal drinking age with an excess of screen time, I’m about as peripheral to this genre as a person could be. But for me, part of the joy of this music is how sophisticated it is, regardless of my vantage point or knowledge level. Like the best dance music scenes, every inventive new tweak on the genre’s core themes and rhythms suggests a lively creative dialogue just below the surface. Like the best pop music, all of the choices “work,” nothing stays too balanced-out for too long, and the songs have an immediacy that never distracts from their depth, history or relevance. It’s not music that just wows you with the shock of novelty, or surprises you with an explosive timbre or two—it introduces you to a whole new way of making amazing songs. If you have ears, you can lose yourself in it.

With their new album Isidalo, a 17-song grab bag that runs the gamut of sounds percolating through this side of South African pop at the moment, producer-singer duo Murumba Pitch want to make sure you do. The bulk of the album is loungey, sumptuous and leans towards R&B, fitting the vocal abilities of Maeywon and other stars like Nkosazana Daughter and Daliwonga. Shakes and Les, who made one of my favorite amapiano records of the new year with “Funk 55,” bring their wavy energy to the co-production of four songs here; “Basazolimala” is my fave. This is primarily a vocal showcase, though—some of the tracks aren’t even really amapiano, shifting into something more like Afrobeats to highlight the pop bona fides of all the personnel. Murumba Pitch are familiar with crossover experiments (2022’s “Deep Kinda Loving” is basically a Craig David song) but here they’ve found a formula that preserves the structure of amapiano without some of its formal identifiers. “Forever Yena” is transcendent, a total universe-pleaser bolstered by some cool, bubbly percussion that simmers and undulates with amapiano’s pace and breadth until all the combined voices overwhelm you.

Pretty much every track here has at least one notable sound that keeps me interested, like the distant radar pulse of “eWallet.” But Isidalo mostly stays in a chill and soulful mode; few of the tracks dabble in the kind of brooding, clattering spectacle, with heavier drums, rapping, and evil laughs, that typifies the other end of the genre. The exceptions are “Follow Me” and the wonderfully weird “Umoya.” The rigid rhythmic grid of that song feels like it’s in conversation with the rising 3-step subgenre, which totally reorients everything Murumba Pitch are doing and makes the song’s slow build feel especially tense. In between the pounding log drums, and about three different layers of escalating vocal chant samples, they sneak in some menacing bass slides… and somehow, regardless of what emotional tenor you think the song’s in, they always bring it back to center those anthemic vocals… and add in some slick saxophone runs, too, just to keep things breezy. It shouldn’t work, but it does. It always works.

[7]

Average: [6.88]

Rafael Toral - Spectral Evolution (Moikai, 2024)

Press Release info: Threading together twelve distinct episodes into a flowing whole, Spectral Evolution alternates moments of airy instrumental interplay with dense sonic mass, breaking up the pieces based on chord changes with ambient “Spaces.” At points reduced to almost a whisper, at other moments Toral’s electronics wail, squelch, and squeak like David Tudor’s live-electronic rainforest. Similarly, his use of the guitar encompasses an enormous dynamic and textural range, from chiming chords to expansive drones, from crystal clarity to fuzzy grit: on the beautiful “Your Goodbye,” his filtered, distorted soloing recalls Loren Connors in its emotive depth and wandering melodic sensibility. The product of three years of experimentation and recording, and synthesizing the insights of more than thirty years of musical research, "Spectral Evolution" is the quintessential album of guitar music from Rafael Toral.

Purchase info: Spectral Evolution can be purchased at the Drag City website and at Bandcamp.

Gil Sansón: After carving out a space for himself with his guitar drone work during the ’90s, Rafael Toral moved away from plucking guitar strings into knob twisting and feedback circuits, hinting at a phase of private investigations. Spectral Evolution is a synthesis of different threads into a single vision. It’s an expansive long-form piece that often sounds like elongated jazz chord progressions with feedback circuitry on top. It’s glassy and shiny, ebullient and bubbly, sounding at times like harmoniums and at others like the unsteady pitch of ocarinas and whistling. We’re even treated to unprocessed guitar plucking at times, revealing that Toral isn’t interested in exploiting a single idea but is intent on consolidating all of his previous ideas into a cohesive whole. The raucousness of his custom-made electronics offers a respite from the more beatific, organ-like sounds, and thus ensure things never get too soft or pretty; this element often behaves according to the overtone series and thus leaves the door open for melodic counterpoint, as well as suggesting non-Western instruments. A feeling of transcendence is evident. At times I long for a guitar freak-out to offset the greenhouse beauty, but this is my problem and not Toral’s; you can tell this is exactly what he wants.

[7]

Vanessa Ague: I’m listening to Spectral Evolution seated next to a window, watching the sun fall in and out of view as dense clouds glide across the sky. I find it surprisingly fitting for the experience of listening to this music, which is in a constant state of back-and-forth between trilling dissonances and blossoming sweetness. In the best kind of durational listening, catharsis comes from experiencing moments of decay, a burst of delight born from the rubble. Spectral Evolution feels like a constant exploration of that idea, basking in the convergence and divergence of every chord and every note. But by the end, the beauty is there to stay—tumbling out of gleaming melodies that swirl above soft electronics, sliding through the atmosphere as easily as those clouds up above.

[8]

Jesse Locke: This album initially reminded me of Eric Chenaux, another tone-worshiping guitarist who punctuates dense drones with squelching, birdlike chirps. Yet unlike Chenaux, whose songs typically include softly uttered vocals and traditional structures, Toral stretches these sounds into unrecognizable shapes. Reading more about his process put a smile on my face when I discovered why certain passages sounded familiar: “Changes” (9:48-12:35) shifts the chords from Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm” at a glacial pace, while “Take the Train” (14:38-19:02) is a slow-motion ride on Ellington and Strayhorn’s “Take the ‘A’ Train.” Fans of Tuluum Shimmering, the Dick Slessig Combo, or label boss Jim O’Rourke’s “Fast Car” will tell you this abstracted ambient approach is nothing new, but in the hands of a space-music master like Toral, jazz standards have never sounded this cosmic.

[9]

H.D. Angel: Rafael Toral makes ambient music with the clarity of a soundtrack and the brain-jogging feel of solving a crossword. Spectral Evolution is populated with so many distinct modular birdcalls that it seems hard not to think about the album cover. Then the bodies of the songs, driven by intuitive jazz-chord swells, tease out whatever worlds and systems you’ve constructed around the birds in your head. (I was so preoccupied with the nature thing that the opening guitar passages felt rustic, evoking some rural country place—then I totally abandoned that image once the big synths kicked into gear.) So much ambient music functions as accompaniment to whatever you were already doing; this is invigorating enough, and obvious enough, to make you do, or realize, something else. Even staring at the ceiling becomes an interactive experience, full of motifs and directions. Although it’s not exactly a zeitgeisty album, I think that sense of motivation is really effective right now. In a world of palliative, vibes-based art allergic to the task of imagination, Spectral Evolution demands your attention, but is still generous enough to ask for your input, with all the sensory uptake of a good biology-class doodling session. (Can music be “eye-catching”?)

[7]

[8]

Leah B. Levinson: Lately I’ve taken to describing certain works—movies, books, albums, etc.—as propulsive. Having given it some time and some thought and some practice, I’d like to define the term.

1) A propulsive work must exist in time. This allows it the possibility of 2) moving forward. If it passes those qualifications, it must 3) have the quality of revealing itself. Revealing itself is, in fact, the chief formal concern of the propulsive work. It 4) sets its own rhythm and 5) defines itself at every turn, while 6) seemingly knowing for itself what it is at its very start. And 7) it moves with an undeniable momentum, whether the rhythm of that movement is “slow” or “fast” in comparison to other works. Lastly, it must be 8) imbued with, and must inspire within others, The Spirit.

A short list of some I’d consider propulsive works: Querelle (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1982); Little Girl Blue (1959) by Nina Simone; Certain Women (Kelly Reichardt, 2016); Beautiful Losers (1966) by Leonard Cohen; Ten Skies (James Benning, 2004); Quarantine (2012) by Laurel Halo; Tongues Untied (Marlon Riggs, 1989); None So Vile (1996) by Cryptopsy; Frisk (1991) by Dennis Cooper; 20th Century Piano Genius (1986) by Art Tatum; Our Aesthetic Categories (2012) by Sianne Ngai, Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969); Moses Und Aron (Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, 1973); Nowhere (Gregg Araki, 1997); and Spectral Evolution (2024) by Rafael Toral.

[8]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Current data shows that vocal production learning has different layers of complexity and can fall into three different categories. The first involves no actual control over what is uttered: think about the immediate yelp you let out when experiencing sharp, unexpected pain; or the way you scream when someone scares you. The second does involve control and is contextual, but does not lead to the production of anything new. This is like teaching a dog to bark on command; you can reinforce this behavior by initially giving treats, and eventually it’ll just bark whenever you ask. The third is the most complex, and leads to the learning of non-innate vocalizations—we don’t see this phenomenon except in bats, hummingbirds, parrots, songbirds, pinnepads, cetaceans, and humans. This is possible because there is a forebrain pathway that can process auditory feedback in real time; the animal needs to compare what they’re saying with what it is supposed to sound like, leading to a gradual acquisition of, for example, human language. What this means is that the “babbling stage” for any human infant is an important hallmark of true vocal learning.

On Spectral Evolution, Rafael Toral engages in a form of babbling by proxy. The album begins with an electronic instrument producing what sounds like birdsong. For the piece’s first 10 minutes, these sounds dot the droning landscape, arriving as a dawn chorus in cresting waves of synth pads. If the sound of birds often evokes a sense of peace within ambient and new-age music, Toral certainly captures that here, but with a nuanced understanding of the sound’s utility. There is a sense of vitality to these passages because of the way his “birdsong” oscillates between sounding convincing and like an obvious facsimile. He invites a form of listening that makes transparent that he’s in a stance of searching. You can hear that through general associations in sound: the sound of birdsong sometimes turns into flickering static, like you’re trying to dial into a specific ratio station.

Spectral Evolution is in a constant state of flux. Notably, in utilizing a single-track, 47-minute structure, Toral finds a way to interrogate the entire history of his work. Spectral Evolution is considerably different from his initial ambient era, despite the surface-level similarities. His debut album Sound Mind Sound Body has a spaciousness defined by silence and simplicity, and the albums that follow riff on that idea even if just in spirit (there’s definitely more going on in Violence of Discovery and Calm of Acceptance, but it still feels like contemplative mood music). The Space Program records may feature the same instruments that are present here, but he approached jazz in this manner. Consider the way his instruments zip around in a group context across Space Elements Vol. III, or traverse free improv territories in Space Solo 1 (an album that, curiously, finds overlap between free improvisation and the earliest novelty synth experiments). With Spectral Evolution, he aims for something more foundational: he utilizes some of the most famous chord progressions from jazz standards to build an active slab of ambience.

One of the most striking passage of the album is when you hear Toral riff on Duke Ellington & Billy Strayhorn’s “Take the “A” Train.” These are familiar sounds, and the comfort of hearing them is real, but it becomes fully realized when one of Toral’s electronic instruments evokes the sound of a horn; this is jazz that arrives via suggestion, like a wisp of smoke that’s noticeable but soon gone. What results is a music far more “hauntological” than the music of The Caretaker, where associations of the past are conjured through cheap signifiers. This is an album that recognizes the beauty of a past music and wants to honor it, that wants to trace histories as a way to make sense of their own. Toral recognizes his own inability: “I knew I couldn’t make a jazz composition because I didn’t have the compositional skills to do that,” he told me in a recent conversation. And now over four decades into writing music, he still positions himself as a babbler approaching speech; like all good artists, he’s always finding his voice.

[8]

Average: [7.86]

Recommendations Corner

For our Recommendations Corner, Tone Glow’s writers have the chance to write about anything they want that’s caught their interest.

Chad VanGaalen’s Full Moon Bummer (self-released, 2021)

Chad VanGaalen’s music has been with me for a long time. Back in the day—slightly before my day, at least—he was known for busking outside a pizza shop. There were legends about the time he put a piece of human shit in a hot dog bun and turned that in as his final project for art school. Apparently, the shit dog was stolen.

Around that same time, Chad was on David Letterman’s “Stupid Human Tricks.” He became a brilliant animator, grafting influences from Jim Henson, Philip K. Dick, and Bruce Bickford into his own gloopy psychedelic slop. He was a one-man-band with a warped sense of humor, and he wrote some truly beautiful songs.

Chad produced Women’s self-titled debut and the peerless Public Strain, two of the most mesmerizing, emotionally resonant avant-rock albums to come from anywhere, never mind my hometown. Listening to Cindy Lee makes it even more fascinating to hear Women as a precursor to the fragile, haunted music Pat Flegel has been making in the years since their breakup. Chad helped Alvvays create their sound, with the deft touch of free-improv and pop drumming polymath Chris Dadge. In short: Chad’s music, and the music he’s touched, has been the soundtrack of my life for the past 20 years.

Chad and I are friends now. We send each other texts about skate videos, and whenever I’m in town, I head over for a sesh on his mini-ramp. He made a song with my sister. He works on music with other good pals like Astral Swans, MISZCZYK, and Sunglaciers. Obviously, I can’t be objective about the bazillion amazing things that Chad does, but I will tell you he sneakily self-released an album called Full Moon Bummer on Bandcamp in 2021. A lot of people didn’t seem to be paying much attention after Sub Pop and Flemish Eye put out World’s Most Stressed Out Gardener earlier that year. I didn’t even know about Full Moon Bummer for a while.

Chad’s sweet, weary voice floats through classic-sounding melodies on songs like the laid back campfire strummer “Slow blade,” clanging motorik jam “Endless Hallway,” and hiccuping highlight “What do you know now?” The structures of his verses and choruses are straightforward enough, but there are all kinds of whizzing, popping whatsits in the background, like a tiny army of goobotz marching into the session. There are loose, wordless jams on drizzly synths and drum machines, some kind of plucked zither-like instrument, and a final goodbye with the twinkly, chirping ambient closer. It’s all over the place, like Chad’s best albums are.

“Sing a song” sounds like a slacker rock interpolation of the Edison Twins theme, and I’m not sure if that’s intentional or subconscious, on my (or Chad’s?) part. That TV show is just one of the countless bizarre cultural imports spoon-fed to people in this so-called country, but thankfully CVG’s art and music are just as ubiquitous in my own memory. Even right now, while I’m sitting in a hideously beige, neon-lit food court after a long, hot appointment to renew my driver’s license, I can listen to Chad and imagine something colorful. —Jesse Locke

Further Ephemera

Our writers do more than just write for Tone Glow! Occasionally, we’ll highlight other things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

Vanessa Ague wrote about Kristin Norderval and Friends’ multidisciplinary performance What Comes Back to Us for I Care If You Listen.

Ashley Bardhan wrote a review of Chelsea Wolfe’s She Reaches Out to She Reaches Out to She for Pitchfork.

Frank Falisi interviewed avant-garde filmmaker Deborah Stratman for The Film Stage.

Marshall Gu wrote a review of Can’s Live in Paris 1973 for Stereogum.

James Gui wrote a review of the Request Stop compilation for Bandcamp Daily. He has also transformed his folk music column at the website into Ley Lines, which “will feature artists playfully deconstructing notions of tradition, imagining new connections, and representing marginal voices in folk music from around the world.”

Michael Hong’s latest issue of Mando Gap features reviews of Akini Jing’s VILLAIN, jiafeng’s Early Technologies, and more.

Vincent Jenewein wrote about the ’90s techno producer Marco Carola for his blog, Infinite Speeds

Jesse Locke wrote about Pseudo Laboratories for Bandcamp Daily’s monthly Tape Label Report.

Jude Noel wrote a review of Frances Chang’s Psychedelic Anxiety for Bandcamp Daily. He also wrote about Scavenger Sounds for Bandcamp Daily’s monthly Tape Label Report.

Joshua Minsoo Kim wrote an obituary for Damo Suzuki at Rolling Stone. He is also still making lists of the best K-pop songs each week.

Shy Clara Thompson wrote a guide to Vocaloid releases for Shfl.

Thank you for reading the 126th issue of Tone Glow. Amapiano to the world.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.