Tone Glow 119: Writers Panel & Recommendations Corner, 1/22/2024

Our Writers Panel on Astrid Sonne's 'Great Doubt' and Takashi Masubuchi + Ayami Suzuki + Tomo's 'Suikyō'. Also: Our Recommendations Corner on the greatest sandwich in Chicago

Writers Panel

For our Writers Panel, Tone Glow’s writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Astrid Sonne - Great Doubt (Escho, 2024)

Press Release info: Great Doubt is the third full length LP by Danish composer Astrid Sonne. Throughout her acclaimed discography, Astrid Sonne has been carefully crafting different moods through electronic and acoustic instrumental endeavours. On “Great Doubt” this skill is refined, now with the distinct addition of the composer's own vocal in front. The tone of each track is unmistakably Sonne’s, structured around contrasts through an impeccable sense of timing. Lyrics on the album are sparse, merely highlighting different scenes or emotional states of being, leaving the music to fill in the blanks. Yet they also form a pattern of ambiguity, consolidated through the album title, searching for answers through looking at how and what you are asking, questions for the world, questions of love.

Purchase info: Great Doubt can be purchased at the Escho website and at Bandcamp.

Maxie Younger: Astrid Sonne’s pivot from formless modular scribbles to cartoon-pop melodrama threads a tricky needle with plenty of humor and panache. “Light and heavy” is an interesting choice of opener, providing almost no context for anything that follows it besides a silly, brassy closing horn note with all the grace of a keyboard preset: here, the new Sonne aesthetic invades the old. Great Doubt lives in this blaring register henceforth, a precisely rendered theater of the obvious—skeletal MIDI loops that wail in Comic Sans, blown-out drum breaks, string harmonics sawed rough until they crack apart. The minimalist pomp of “Do you wanna” reads like a satire of pop music in the blunt Denniz Pop/Max Martin vein, reveling in loose assemblages of words that fit around melodies like hand-me-down coats. When Sonne drolly intones “Do you wanna have a baby?” over dissonant piano intervals, it’s a mirror-universe refraction of the broad, incorporeal character strokes of an “All That She Wants” or “The Sign,” mashing studied camp and genuine introspection into uncanny stream-of-consciousness prose.

The album’s instrumentals reflect that same spontaneity. “Boost” scrolls languidly through different drum breaks like it’s previewing samples in a DAW browser; “Staying here”’s chintzy synthetic woodwind lead is washed away by icy, sliding pads that linger maddeningly between chords. This is music that knows it’s music—songs performing the concept of being a song, cutting jarringly between ideas as though reading from a distant teleprompter. It’s a surprising, engrossing, and innately likable stylistic shift for Sonne, one that leaves me greedy to hear what she might create next.

[8]

Marshall Gu: On Great Doubt, Danish musician Astrid Sonne incorporates her own vocals and drum machines, making her half-digitized, half-chamber compositions edge closer to pop music. I just wish it actually popped? The songs feel uncertain about this new territory, one foot staying firmly on the beach where the water never breaches. “Do you wanna” starts with monolithic drum machines creating an addicting pulse, but as soon as Sonne sings the first line, it’s clear the song hits its climax, and it just hangs around for another few minutes afterwards, unsure of what direction to go. Songs like “Almost” and “Staying here” deploy different textures—viola and then flute—but as neither are fleshed out, they feel like glorified interludes. “Say you love me” plods with that reverb-heavy drum sound into its too-short coda; these are exercises in minimalism in less than three minutes. Her voice has a natural sweetness to it, but it’s applied sparingly, making all of this feel like a bedroom pop detour compared to her more thoughtfully-textured work where she isn’t singing.

[5]

Vanessa Ague: A good one liner shouldn’t be too obvious, nor should it be too abstract (where’s Goldilocks when you need her?) Astrid Sonne tries to strike that balance on Great Doubt, but the porridge is too cold. Her words leave little to the imagination—“I’m not going anywhere / staying here with you” she coos in a feathery voice, for example, like a text message you might send a lover too late at night. Similarly, her instrumentals ring hollow; a touch of piano here, a whispering electronic there. But when she picks up her viola, its medieval resonance fills out her words with the touch of anguish that comes with falling in love. “Where words fail, music speaks,” I saw on a motivational poster once. Maybe Sonne is onto something.

[6]

H.D. Angel: Playing with front-facing vocals and identity as an ostensibly experimental musician is a good idea; it lets you adopt the pose of an outsider, someone too sui generis to be defined by the singer-songwriter format. Yves Tumor eventually willed themself into a rockstar this way. Inga Copeland and Dean Blunt turned building pop songs inside-out into a complete worldview. Last year, Astrid Sonne’s tourmate ML Buch put out a great record, adjacent to this one but more rooted in rock, with Suntub, and figured out new ways to structure a kind of methodical computer-void psychedelia I thought I’d gotten tired of. Meanwhile, Tirzah and Mica Levi went into DP Beats mode on trip9love…?, which was a fun left turn that kept things from getting too procedural and reinvigorated their usual dynamic.

Astrid Sonne, however, doesn’t grab me—not even in theory. Almost nothing interesting or engaging happens with vocals on Great Doubt. Sonne probably sings 150 words on this album in her listless affect and I can only remember about 10 of them. The album wants to have a sense of humor that sneaks up on you, but the jokes have been told before with more daring sounds. It wants to subvert expectations, but any ideas of its own shrink under the scrutiny it’s asking for. The big trip-hop moments are compelling—especially “Boost,” which locates the right “ambient-ish composer makes beat-oriented music” tension, arriving at a disorienting effect akin to someone like Klein. But these songs still feel less weird than the stuff I’d find randomly pulling ’90s electronic records from my college radio station. None of the composition during the more straightforward passages overwhelms me like some of Sonne's previous work, either.

“Overture” is pretty vibrant though. And it rules that she plays the viola. Violists are cool :)

[5]

James Gui: For the 2020 Busan Biennale, Astrid Sonne made music as a supplement to poetry as a part of Words at an Exhibition. That project was plenty expressive without any recorded voices. But she opts to tell, not show, on a record abound with platitudes like “we will never be the same again” and “you’re so far away” (Kelela is fuming). The effect is obfuscatory instead of enlightening as the music takes a back seat, often manifesting as clunky, underproduced loops. It’s telling that the best moments here are in tracks without any words at all: the lovely flute tones on “Light and heavy,” for instance, or the gentle horn swells on “Overture.” The union of sonic abstraction and poetic articulation can often be fruitful, but this record might not be the best example.

[5]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Astrid Sonne’s work has always captured the strangeness of living. On Human Lines, a track like “Real” began with wobbling synth lines that get interrupted to prevent a seamless loop, and then they land in murkier territory: a slow-rising ambience that feels like being in the bathroom at a club. There’s an uncanniness to this othering of the primary field of sound, where one is placed in a setting that is less so liminal than lonely.

Much of Great Doubt carries this same queasiness, where the excitement that comes with existence feels just out of reach. It is this proximity that Sonne is interested in: What decisions lead to love and joy and the other Grand Emotions of life? Doesn’t it seem a bit too easy to attain them? Should I be thinking about all this so much? “Do you wanna” is at once a humorous, contemplative, and uncertain deliberation about bearing children. At moments, there is a sense of lift found amid the clang of drums and piano, and it is this fleeting sense of clarity that illuminates her uncertainty. Right after, Sonne announces on “Give my all” that she’ll commit to a lover as chords progress in slanted manners, the swooping organ synths underlining her words with a palpable uneasiness.

As the first proper singer-songwriter album from Sonne, Great Doubt makes great use of its instrumental pieces to flesh out her emotions. Out of context, “Boost” can sound like a fun little exercise in contrasting timbres, but it adeptly captures the paralyzing nature of being. On “Everything is unreal,” it is her dispassionate tone that leads to everything feeling stuck (in the “lying in bed for hours because of depression” way), but “Boost” opts for a listlessness through cheeky contrasts. Its changing drum beat is simple but pointed, and feels like staring at your walls and noticing small changes in texture. Last year, I was transfixed by Suntub, the album from Sonne’s friend, tour mate, and collaborator ML Buch. That album was something I liked putting on when I had nothing to do. Great Doubt is the same sort of record, except for when you have this nagging feeling that you should be doing something. When “Say you love me” closes the album, it feels like a hapless request. The glimmers of dub reverb are necessarily unsatisfying; Sonne is left wanting more.

[8]

Vincent Jenewein: Astrid Sonne’s last album Outside Of Your Lifetime was a nice cozy little ambient thing. Great Doubt is decidedly more ambitious, with songwriter-y vocals, various beats and a thick stack of musical references packed within the album’s nine short tracks. Unfortunately, that ambition ends up floundering, as the tracks that do the most here also end up being the worst. Especially the beats are a problem, they don't really work and have a lifeless and slightly cheesy aftertaste that resembles stock DAW loops. The compressed acoustic kit on “Do you wanna” falls flat without punch and impact, while the attempt at a vaguely dub riddim track on “Say you love me” doesn’t really go beyond peppering in a bit of spring reverb over an overall uninspired rhythm section. The vocals do what you’d expect from a record like this but they aren’t especially emotive or captivating. Other stylistic excursions like the organ number “Staying here” also fail to impress, with plastic-y tones, flat vocals, and stale reverb. Great Doubt is far from being offensively bad, but it feels like an underdeveloped record that had the artist spread themselves too thin with a lot of attempts at various ideas, without the necessary level of craft and production required to pull them all off.

[3]

Jinhyung Kim: I have a soft spot for the enigmatic deadpanners of ’10s art pop—Dean Blunt, Lolina, and Tirzah most notably. I couldn't muster hype for the ML Buch LP last year, though; listening to this Astrid Sonne record helped me put a finger on why. Buch, on Suntub, is committed to the sound world her electric guitar noodling generates, and the instrument and her vocals possess a similar smear and sheen. Apart from a couple of more engaging tracks (like opener “Pan over the hill”), the focus is on linear texture over songcraft, and a glass-walled deadpan—no matter how shimmery or sly—is far less compelling to me as a mere textural (rather than a properly structural) affect.

I at first felt a little more drawn in by Sonne on Great Doubt, with its ample negative space and the cute uncanny of its MIDI-shaded sonic palette. But these are semblances of structure and variety moreso than the real deal: the melodic and rhythmic forms that the timbral elements take on feel haphazard and interchangeable, as if so long as the actual sounds were the same, grafting them onto different patterns would hardly change the total effect. I only realized this after listening several times and noticing that there was hardly a line or two from the album that had hooked me, or that I could even clearly recall. Given how bare-bones Sonne’s arrangements are, this is a laxity she can’t really afford—if you’re only marking a fraction of your canvas, you need to be more deliberate. The negative space, then, turns out to be just texture as well, a shortcut to affect and “cool” rather than an emergent or structural quality. Great Doubt is exactly my shit on paper, but it ends up a pale shadow of its spiritual predecessors—as well as of the record it could’ve been.

[4]

Gil Sansón: Although I tend to wince at music that’s fully programmed using MIDI VST instruments, Astrid Sonne makes it work: her musical palette is used sparingly to highlight her voice, and it brings to mind hushed ’80s acts like This Mortal Coil. Still, she approaches her songs with a music vocabulary all her own. There’s a certain angularity to her instrumental lines, where the oversized drums—reminiscent of Peter Hammill’s work—are imbued with a lot of character. Take the staccato organ on “Staying here”: she trusts her instincts well enough to not pile too much on top of a good line. Even more, she refrains from hammering on with her choruses and hooks, with songs ending well before their expiration date. Her music is familiar but jagged: it’s art pop and the smooth sounds of Sade loosely tied together with an evocative album title. And with how short the album itself is, I keep craving more and I press repeat.

[10]

Average: [6.00]

Takashi Masubuchi + Ayami Suzuki + Tomo - Suikyō (An'archives, 2024)

Press Release info: The latest release on An’archives, Suikyō, documents a first-time meeting between three Japanese improvisers: Takashi Masubuchi on guitar and harmonica; Ayami Suzuki on voice and electronics; and Tomo on hurdy-gurdy. Recorded at Permian on the 29th of January, 2023, it’s a stunning, forty-minute long improvisation of rare artistic sympathy. Notably, it was the first time the trio had performed together, though Masubuchi and Suzuki have prior form as a duo; on the evening itself, the trio performance was preceded by solo sets from Suzuki and Tomo, which served as a kind of introduction, of sorts, to the broader aesthetic visions of two of the musicians on Suikyō. Masubuchi, Suzuki and Tomo make for a fascinating trio, not only due to the shared musical sympathy that’s clear from their performance, but also due to their histories, and the way these dovetail on the music you hear on Suikyō.[…] As a first encounter, it’s surprising in both its comfort and its challenge: and as Masubuchi says, the playing together feels just the way it had to be: “instinctive, unintentional, and inevitable.”

Purchase info: Suikyō is currently available at the An’archives Bandcamp page and website. The LP is currently available for purchase at Soundohm. The album is officially out on January 26th, 2024.

Vanessa Ague: A few lonely notes color the first minutes of Suikyō, as if the car is just starting and it’s 10 degrees out. But once the engine heats up, the trio is off for the races. Tomo’s hurdy-gurdy, which is bowed with the fervor of a Bach sonata’s fugue, seamlessly interweaves with Takashi Masubuchi’s sunny guitar strums and Ayami Suzuki’s feathery hums until the whole thing reaches a critical mass of entangled drones fit for a summer drive by the beach. By the time their gleaming melodies have stayed their welcome, the trio veers back into the murky unknown, navigating a mess of haunted plucks and hums on their way to another light at the end of the Holland Tunnel. Their music isn’t the kind of thing I’d put on before swerving into the fast lane, but wherever they’re going next is somewhere I’d like to be.

[8]

Marshall Gu: Takashi Masubuchi creates long improvisations with his acoustic guitar; Ayami Suzuki creates long improvisations with her voice. Together, they create long improvisations with an acoustic guitar and voice. Sure, I’m being reductive. And sure, it leads to pretty snatches, like when Masubuchi’s guitar demonstrates a Delta blues influence during the second half while Suzuki’s voice peaks in and out in harmony. What really separates Suikyō from Featherland, their first recordings together, is the third collaborator, hurdy-gurdy playing Tomo, whose medieval wheel instrument joins the other sounds and somehow blends it into a drone-meets-Celtic jig, recalling Suzuki’s history as someone who got her start playing Celtic music in Tokyo and eventually moved to Ireland for a time. But I’m not getting enough here! The music is too fussy for ambient, the tones themselves aren’t special enough (although I like the harmonica near the end) even if Suzuki’s voice is always a treat, and the climaxes feel altogether too telegraphed despite being likely completely improvised.

[5]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Featherland was one of the great unsung records of 2023, an album whose sparseness and patience placed it in the pantheon of Japanese onkyo-folk alongside Moe Kamura’s albums with Taku Unami. Suikyō should be understood in this context despite its moments of bombast. When Masubuchi plucks his guitar, he does so with an intention to let it resonate, to let you hear how it dissolves into the silence around it—like Cristián Alvear’s Wandelweiser realizations. His guitar figures evolve and flutter, softly but assuredly. And alongside Ayami Suzuki’s own vocalizations and Tomo’s hurdy-gurdy, their presence is solemn and spiritual, like wisps of smoke rising from burned incense. Even the clamor that eventually arises is contained: a meditative space to revel in sound qua sound. I’ve put on Suikyō in early mornings before heading to work. It feels right for these moments when the world is still; it doesn’t ask anything of you but to sit and listen.

[7]

Jude Noel: There’s a surprisingly tight structure to this trio’s improvisation that roughly repeats on either side of 水鏡 (Suikyō). First, each member figuratively paces around the sound field—usually led by Takashi Masubuchi’s gentle fingerpicked shapes—and disclose tiny phrases to determine how much space they take up. Once oriented, Tomo (hurdy-gurdy) and Ayami Suzuki (voice) begin to produce more full-bodied drones that dissipate into each other’s territory, hovering and coalescing behind increasingly melodic guitar parts. Once Masubuchi reaches for the thicker strings to pound out chords, the group spends the second half of their performance gradually dialing up their intensity, letting their streams of consciousness coil and stutter freely.

Both halves of the record sound best when the trio lets it rip, especially two-thirds of the way through “Part 1,” when Tomo’s hurdy-gurdy assumes a harsh, buzzing timbre and flickers like a telegraph signal as Suzuki’s sighs begin to waver. It’s as if he’s transmitting a coded message meant to transcend the performance, each pause imbued with urgency. “Part 2” is prettier than its predecessor and opens with more traditional harmonic interplay between Masubuchi and Suzuki, though Tomo provides much-needed tension by peppering in tiny hiccups and burps on his instrument. Once again, though, the track is much more compelling as it nears conclusion—particularly when a harmonica enters the mix and shreds through multiple sustained drones. I’d have appreciated more surprise throughout the record, forcing the band to adapt to disruption on the fly. The moments of unbridled chaos are great fun, but there’s a lot of waiting around to get to them—especially when you can see them coming.

[5]

Jinhyung Kim: An’archives has been doing a lot of great work over the past decade to make some of the strongest voices (past and present) out of Japan’s free rock underground heard: Kyosuke Terada, Shizuo Uchida, Takahashi Ikuro are some names that recur under a variety of collective monikers, and the past couple of years alone saw stellar records by Ki, HUH, Archeus, and Chi To Shizuku—the pinnacle for me being two archival releases by psych/noise rock legends Shizuka. Suikyō is notable in that alongside hurdy-gurdy player (and Archeus member) TOMO are vocalist/sound artist Ayami Suzuki and guitarist Takashi Masubuchi, who I associate with the more staid, onkyo-ish + reductionist side of Japanese improv—their past collaborators include Leo Okagawa, Taku Sugimoto, and each other. The hurdy-gurdy has a rather dominating presence, though, so there’s not much room for that type of subtlety here; it’s an anchor instrument through and through. Even long before it cranks up to full gear, the other instruments consequently make more or less conventional contributions to a steadily dilating, consonant swirl of sound. Which is fine! I’ll take a sea of drone that I can put on in the background and lose myself in any day. But it’s disappointing that Suikyō lacks both the noisier, more jagged edge of other music in the An’archives catalog as well as the defiant restraint of something from the Ftarri-sphere—the middle of the road ought to have been a lot more interesting than this.

[3]

Gil Sansón: There is an approach to free improvisation that fosters and evokes the ecstatic experience. Musicians in this mode have a common, preordained goal, and on Suikyō—which is one long track, split in two parts—one loses himself in images of desert landscapes and journeys of self-discovery. The music never gets too wild; it seems intent on keeping a certain vibration as it drones with acoustic guitar filigrees and wordless vocalizations. There’s some indulgence here, but the solos flow smoothly and it carries a beatific mood throughout. The music manifests what it sets out to do, and once it says all it needs to, it extinguishes its fire.

[7]

Average: [5.83]

Recommendations Corner

For our Recommendations Corner, Tone Glow’s writers have the chance to write about anything they want that’s caught their interest.

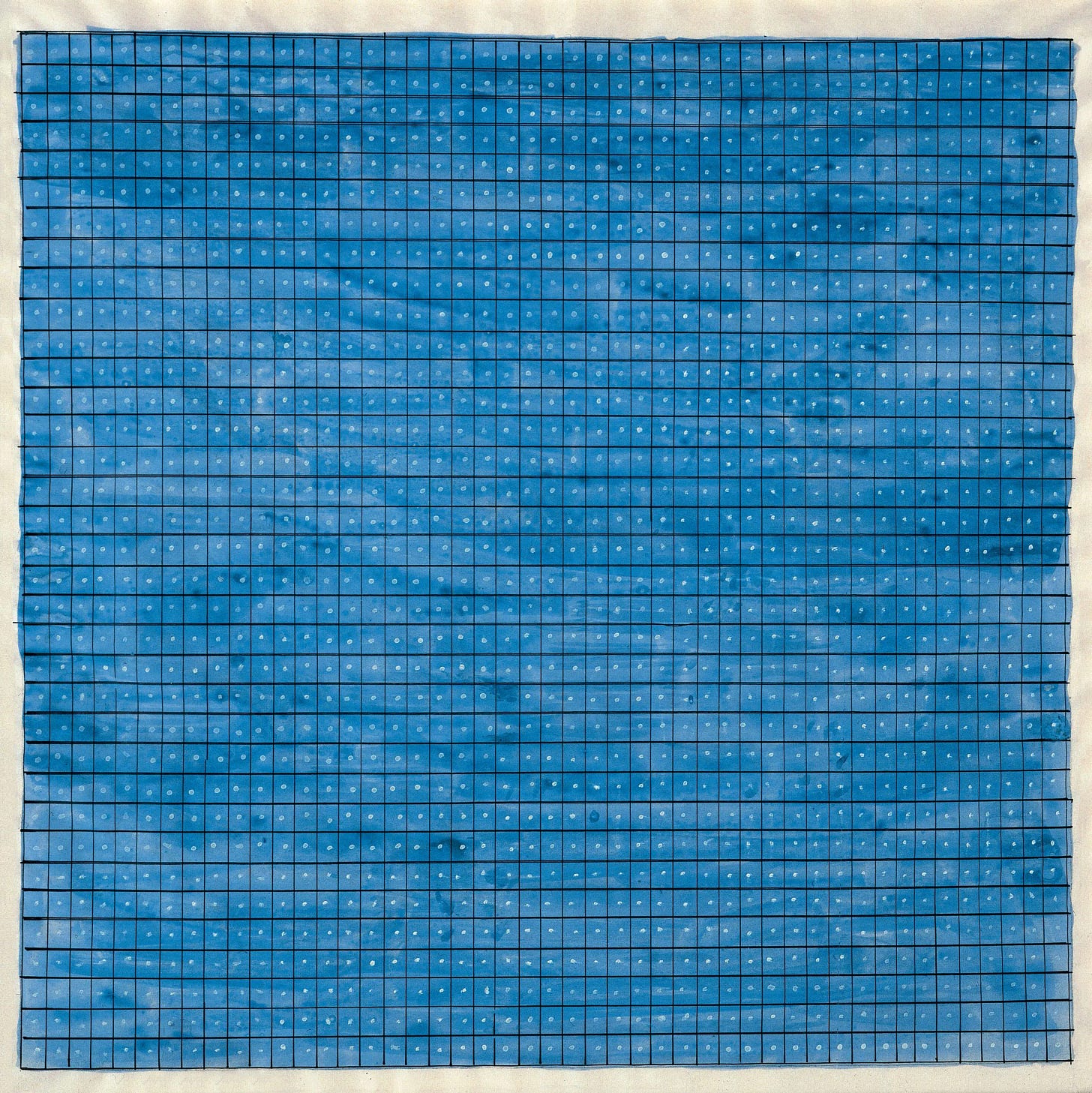

Agnes Martin’s Summer (1964)

What’s in a grid? Agnes Martin spent a life painting lines, grids and dots. It is no surprise that she eventually turned to spirituality, because the grid is irrefutable. Try as you will, paint a hundred, or a thousand, or a million, the lines are lines and the cells are cells and the whole thing is a grid. Isn’t that matter of factness the most techno thing ever? A grid is a grid is a grid. There is no “beyond” of its rote repetition, just like there is no “beyond” to the 1-2-3-4 of the kick drum. But in surrendering to this roteness of the grid, one does not tumble towards mechanistic death, but gains vital life. Just look at this painting, how wonderful and alive and luminescent the blues are; the sense of aquatic life they transmit, the blooming riffs of darker shadows that are hinting at great depths below. And the little white dots in each cell, each a little lighthouse, all together quietly lightning up this little world of grid and blue. And the lines, each vibrating and resonating with its own unique hand-drawn personality. A line is a line, but one line is not like the other. It’s all there, from the first second you look, but you can look at it for however long you want. It’s not inviting or repelling, it’s just there. And this there-ness is a beautiful thing, because it really is just there, like a line or a grid or a cell. —Vincent Jenewein

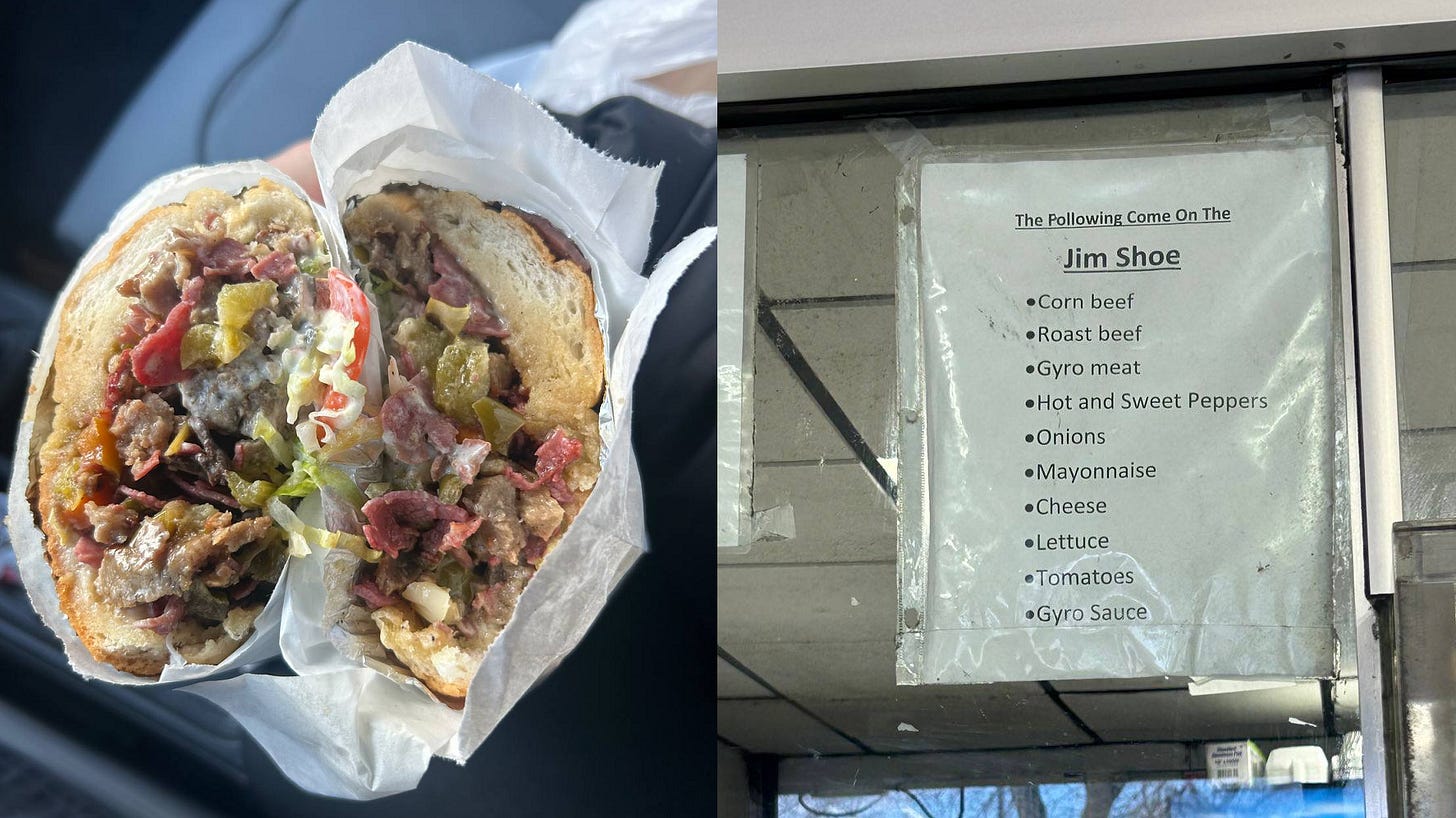

The Jim Shoe from Chicago’s Stony Sub

I attended a puppet theatre show in the South Side of Chicago yesterday, and since I was in the area, I felt compelled to stop by a 24-hour sandwich joint I hadn’t visited in years: Stony Sub. The small building, painted in bright yellow and emblazoned with images of its various offerings, is similar to other establishments in the area: it’s cash only, takeaway only, and has bulletproof plexiglass separating the customer from the staff. There was only one item I wanted to get: the Jim Shoe, a sandwich that is both quintessentially Chicago and largely underdiscussed (it’s because these don’t really exist on the richer and whiter North Side, which most food publications and YouTube videos focus on).

There was another man in the restaurant. He was six feet tall and had on a black puffer coat. I wasn’t planning on talking with him—he was stationed near the door and staring intently at his phone—but things changed once I ordered a King Jim Shoe, a larger version of the original sub. “Yeah, that’s been my favorite since I was a kid,” he told me. He was in town for the weekend and said he had to get one. While born and raised here in the South Side, he’s since moved to South Bend with hopes for a better life. “It’s not that much better than Chicago, but it is better.” We talked about places we’ve visited, and how his parents currently live in Florida. Colorado, however, was his next destination. “Waking up and seeing mountains really changes your life,” I said. His eyes lit up: he’d never been there before but heard great things from a friend, and he was ready for a change of pace. “The only nature in Indiana is the deer.”

When your order is ready at the Stony Sub, they ask if you want any sauce or salt with your fries. You also get a C&C soda (I asked for the ginger ale, he got the strawberry). Your bag isn’t as sopping wet as one would expect with an Italian Beef, but it’s still no less of a mess, especially with Jim Shoes from this establishment. They don’t hold back on the fixings—there’s corned beef and roast beef and gyro stuffed to the brim, spilling out as mayo and tzatziki coat everything in a glorious white. The giardiniera elevates each bite, its heat and tang cutting through the richness of the meats. Foods like this—the kind that people joke are the result of throwing everything in your fridge together—can devolve into a monolithic mush: there’s a lot of flavors, sure, but how often does it feel like eating slop, in turn making you feel the same? The Jim Shoe doesn’t have this problem.

After saying bye, we both went to our respective cars, parked next to each other in front of the restaurant. I had my heat blasting given the freezing weather, and turned on some Philly soul. I didn’t mean for this, but the Gamble and Huff productions—all ornate in their arrangements, transforming every space into a heavenly, ecstatic dancefloor—couldn’t have made for a better fit. If you saw me in that car, you would’ve seen how ridiculous the scene was: I was spilling bits of food everywhere, I’d wipe the tzatziki on my lips with the toasted bread, and pulled more napkins out of my glove compartment than I ever have in my life. But it was so obvious to me, with every second of this meal, that the Jim Shoe is the best sandwich you can get in Chicago. Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes was on the speakers, and I was going through some long-time favorites: “The Love I Lost,” “Satisfaction Guaranteed,” “I Miss You.” At one point, I turned around and saw that the other guy’s car was gone. When I finished, I drove off too. There were no mountains in sight—just grey, icy slush all over the roads. For a brief while, despite everything, it felt glorious. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Further Ephemera

Our writers do more than just write for Tone Glow! Occasionally, we’ll highlight other things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

Vanessa Ague wrote reflections on Phill Niblock’s 90th Birthday Winter Solstice for The Road to Sound

Billdifferen made a list of the 100 Best Jersey Club Songs of 2023 for his blog

Daniel Bromfield reviewed Donato Dozzy’s Magda for Pitchfork

Alex Fields wrote about recent experimental films they viewed over at their blog

Sam Goldner reviewed Chuquimamani-Condori’s DJ E (Tone Glow’s 2023 AOTY) for Pitchfork

Colin Joyce reviewed Salamanda’s In Parallel for Pitchfork

Joshua Minsoo Kim is making weekly lists of his favorite K-pop songs

Jesse Locke interviewed Omni for Aquarium Drunkard

Eli Schoop made a list of the Worst Albums of 2023 for No Bells

Shy Thompson made a list of albums and EPs highlighting Japan’s hyperpop scene

Evan Welsh wrote three poems inspired by music for his blog, Let This Be My Epitaph

Jonathan Williger’s new label, Outside Time, has announced its first album: Nate Scheible’s or valleys and

Maxie Younger reviewed Loukeman’s Sd-2 for Pitchfork

Thank you for reading the 119th issue of Tone Glow. Treat yourself to a hoagie.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.