Tone Glow 118: Writers Panel & Recommendations Corner, 1/8/2024

Our Writers Panel on Li Daiguo's 'Book of Prayers' and Tropa do Bruxo's 'Baile do Bruxo (DELUXE)'. Also: Our Recommendations Corner on a pro cycling kit, the Multi-Tap zine, Leonard Cohen, and more.

An Update to Tone Glow

Tone Glow is bringing back its writer panel, a once-regular feature of the publication that involves multiple writers reviewing the same album. In the past, these often appeared after interviews. Anyone who has been reading Tone Glow has probably noticed that our interviews are typically very long (the most recent one with Black Eyes, for example, was 13000 words). As a result, it felt unfair to our writers and the artists interviewed to have these two things appear in the same post. Moving forward, we will keep these separate, but are also adding in our Recommendations Corner. This will offer our writers the opportunity to write about anything they want, be it an older album or song, a concert, a film, a book, whatever. For this first edition, we have two albums for our Writers Panel and recommendations on a pro cycling kit, a peculiar zine, a Leonard Cohen bootleg, and more.

Writers Panel

For our Writers Panel, Tone Glow’s writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Li Daiguo - Book of Prayers (Pollux, 2023)

Press Release info: None.

Purchase/Streaming info: Book of Prayers can be heard at various streaming services. Book of Prayers is currently not available to purchase.

Gil Sansón: I’m happy to encounter an album with no press release by an artist previously unknown to me, as it allows me to take on the music without preconceptions of any sort (apart from the name, which inevitably suggests certain cultural traits). Said traits are offset early on: indeed, some of the instruments do give away the roots of the music, but others are unfamiliar in this context—a good thing. The titles imply an earnest take on music and its therapeutic aspects; we’re in new-age territory, albeit not of a Western flavor. There’s a significant difference between the syncretic hodgepodge of Western new age and the simple purpose of this music; each track is a prayer for a specific unrest of the soul.

I find it difficult to turn down my cynic filter and listen to music at face value, but there’s a not very new-age quality to many of the prayers, probably because they’re dealing with difficult subjects (unsurprisingly, tracks like “prayer of submission to the inevitability of death” resonate more strongly as the music reflects the darkness of the topic), and because these uncomfortable topics call for a mix of soothing and uncomfortable sounds to sublimate them. It’s hard to explain, but this music sounds both timeless and ferociously contemporary. Some of the instrumental displays remind me of the concept of duende, the essential notion in flamenco music (“prayer to help resistance to addiction” requires a sort of exorcism of the soul by overt instrumental expressivity in a folk like manner, and “prayer for those lost in dementia” is full of compassion and tenderness as well as gravitas). Book of Prayers asks hard questions with an open heart.

[8]

Maxie Younger: Book of Prayers is a tough album to comment on. While it’s charming and occasionally quite beautiful, it also has something of a perfunctory air: music that would occur whether or not I were present to observe it, nests of buzzing overtones and loping grooves that wallow calmly in the gulfs between seconds, minutes, hours. That easygoing spirit belies the album’s reverent track titles, a checklist of meditations and prayers that swing from winking cheer (“prayer for the cute and fragile”) to stark, almost parodical severity (“prayer of submission to the inevitability of death”).

The contrast in moods doesn’t seem to match the breezy music at first glance, but a darkness does encroach in shades as Li Daiguo allows his compositions to wander: “prayer to remember something forgotten” burrows deep in mystery and solitude, morphing its clocklike pulse into a plaintive smear of airy percussion and moody cello drones. I found the cello playing, generally, to be a highlight here—its pushy, glitchy shrieks on “meditation in praise of all quantum possibilities,” especially—but that may only be because I play the instrument myself and enjoyed tracking its presence. Indeed, Daiguo’s perennial fascination with cross-cultural instrumentation ensures that each featured voice has a totally distinct identity from its peers, its timbre projecting brashly from within the mix. Beauty, then, is found through the essential contradiction of Daiguo’s work: how such unique and disjointed flavors can coalesce into an inarguable, natural whole.

[6]

Frank Falisi: I’m not sure if you can hear the name of a song in a song itself. Sure, when that name comes from a moment in the lyrics, you can hear a voice say the name, the title. This phenomenon still feels different from “hearing the name,” from hearing the recognition the artist has given the sound. Maybe when a musician sings the name—when they usher us to recognize this bright-gold portion of their text—they invite an echo, a response, an attentive attenuation. But if the song is wordless? What then? To press play on Book of Prayers, Li Daiguo’s speculative seepage of genre-melt and folk devotion, is to risk missing the titles it gives itself; how often do we chart the changes when we listen, however we listen?

I’ve lived with Book of Prayers for a week or more, hearing the changes from my holey computer speakers, no notion of what Daiguo calls the songs. I just hear the songs calling their own collects, now a kind of classical despair, now a weep of a string thing. And am I anxious over my memory? The way I want things long gone or longing to live? What a fine reduction of mine, to turn to songs like people turn to prayer. Unless the prayer speculates and agitates—unless it unsettles the air—I think it is different from ‘song.’ Call it a different name. Recognize it different. The finger needs to hit a specific point on the neck to make a specific sound. But then I shrink the tabs on my computer screen. I read the titles, all prayers. They recognize where I put my feelings, where Daiguo sings a sound you and I and he recognize. I think we collaborate on a song’s name, with the song and the sounder. Prayer towards a clarified vision. Songs naming history and memory. To and for and on.

[8]

kicking unhelpful substance watching it fade from me left to the bitter unknown what’s becoming tenderly i thought to make a substance to tackle what comes next it’s good so once i have a weapon a number between one and infinity i’ll be learning every lessen the distance between one and two like if love is an affliction god must be suffering each day i try my best to help him out

[7]

Marshall Gu: Li Daiguo does not want to be pigeonholed. He plays instruments that are both Western and Eastern to mirror his own life. Born in Oklahoma and now based out of China, he merges acoustic instruments with electronic ones, and plucks out traditional folk melodies and sets them to non-traditional rhythms. His music has a freedom of spirit, often shifting in unexpected ways from song to song (for example here, “prayer of submission to the inevitability of death” is pure cavernous noise while “prayer to help resistance to addiction” is a strangely twitchy rhythmic dance), and sometimes even within the same composition. “all purpose healing prayer”—whose title reads like a cleric’s ability from some RPG—starts like Steve Reich’s Drumming, brings in dark, droning strings, and then ends up in IDM territory as the focal point changes from rhythm to the strange, electronic noise. And yet, I’m not drawn into these songs, and despite their names being titled different meditations and prayers, I’m not hearing any deep spirituality in any of them. (Given that he’s once called one of his drone albums “death metal,” I wonder if he’s being cheeky with these names.) But because he doesn’t want to stay still, the drone on Book of Prayers isn’t given enough time to envelop listeners (a “prayer to instill patience” might have helped there) while folk melodies will cycle out just as my ears perk up.

[6]

Jinhyung Kim: It’s 2024—East meets West has never been more boring. I don’t really use “instrumental music” to tag anything because the term is so nondescript, but Book of Prayers is itself nondescript enough to warrant the label. These aren’t songs; they’re the barest of grids for a blend of generic signifiers (*cough* “Chinese traditional instrumentation”) to float atop of. This video of Li presenting himself simply couldn’t be more on the nose with its title, description, and content (“New World Music”?? insane cringe). His album needs no press release because the music is a walking press release for itself. Woah, did you know you could put these timbres next to each other? is not a premise that can, on its own, sustain my interest for any length of time, let alone a whole fucking album.

I think a comparison with something like Okkyung Lee's Yeo-Neun—with respect to doing a classical-adjacent, East 'n' West thing that isn’t appallingly mediocre—can help to illustrate: Yeo-Neun’s compositions are far more spare and deliberate; most have an actual structure or processuality that generates some kind of arc or momentum. This sense of space and movement is what’s critically lacking in Book of Prayers. Its canvas is filled up with evenly calculated proportions of timbral variety, all of which ultimately produce the same, static form.

[0]

Average: [5.83]

Tropa do Bruxo - Baile do Bruxo (DELUXE) (self-released, 2023)

Press Release info: None.

Purchase/Streaming info: Baile do Bruxo (DELUXE) can be heard at various streaming services. Note that there is no overlap in tracks between the original release and the deluxe version. As of this writing, the deluxe version is not available on Apple Music and can only be purchased at Amazon Music.

Jude Noel: Baile do Bruxo’s most immediate draw is its distorted, speaker-destroying percussion, hammering at the extreme ends of the human ear’s audible frequency range, but Tropa do Bruxo’s mastery over the mids is what makes the collective’s new compilation so arresting from front to back. Living up to their name, which translates to Wizard’s Troop, the crew’s producers arrange beats as if they’re conducting choir practice for an apocalyptic ritual, layering familiar vocal samples, cyborgian rapping and stock chants that interact in unsettling yet alluring ways.

“CAMISA DA SELEÇÃO” (“NATIONAL TEAM SHIRT”) features the best bricolage of voices: Produced by SMU, who seems to rank just below Ronaldinho in the crew’s hierarchy, the track opens with a breathy groan, which demarcates the quarter-notes of each bar, providing a consistent canvas on which to splatter glossolaliatic vocal rounds and booming DJ drops, which vie for attention as 808s shake the earth’s core. Trying to pay attention to Yuri Redicopa and MC LCKaiique as they trade verses feels like trying to hold a conversation in a crowd—you’re not going to understand much as you’re picking up bits and pieces of adjacent chatter. I’m also quite partial to opener “TUM BÁ TUM,” which sounds deceptively simple. The sample of Eminem x Rihanna’s “The Monster” would be groan-inducing if it weren’t woven into the mix so well. SMU and Vitin do PC constantly modulate the appropriated hook’s pitch and duration as the track rides out, bouncing it off of a wordless chop that sounds excerpted from an “epic” mid-aughts blockbuster trailer. It’s pure ethereal kitsch, recalling Clams Casino’s penchant for Imogen Heap samples, though opting for a less reverb-y mix that keeps the energy raw.

Things tend to drag on cuts where the troop isn’t slicing and dicing their source material, however. The “Tom’s Diner” interpolation on “SAFADA” is too obvious to leave in its undefaced state, and even Bibi Babydoll’s dynamic delivery isn’t enough to make it interesting. Same goes for “PEDE MAIS,” which is built around an uber-vibey synth loop that sounds like it was snatched from Metro Boomin’s cutting-room floor. Fortunately, focusing on the rumble of those deep-fried bass drums makes it easy to forgive a few generic touches.

[7]

Maxie Younger: I’ve been somewhat unplugged from the growing viral fascination with Brazilian funk—aside from an occasional click on one of billdifferen’s Twitter posts about it—but this album is an engrossing snapshot of the skeletal, piercing extremes that define the funk BH subgenre. Tropa du Bruxo and SMU’s regular deployment of acapella tracks from bygone Top 40 hits is a distinct counterpoint to the blunt, jokey edits of artists like dj interior semiotics; when Suzanne Vega’s eternal “Tom’s Diner” melody echoes softly over the beat of “SAFADA,” it’s a haunting ornamentation rather than a cheeky, glaring reference. There’s plenty of room for nuance here, even amongst the cartoonishly blown-out percussion: it’s in the specific length of reverb tails, in the fading frequencies that clash in the gaping rests between sounds, in how one bassline can mediate a variety of moods and guest artists across different tracks (the run from “NA VIBE” to “PEDE MAIS,” which, while somewhat mind-numbing in context, reads almost like a modern take on a theme and variations). Though my engagement with this music can’t extend much beyond genre tourism at this stage of understanding, Baile do Bruxo is still a powerful release that highlights a unique niche within the sprawling, labyrinthine ecosystem of Brazilian funk.

[7]

Vincent Jenewein: On a purely formal level, this stuff makes use of common current-day pop and hip-hop tropes—but it sounds all wrong! I do not know what exactly compels these producers and engineers to go out of their way to disregard decades of established mixing practices, but it makes for some of the strangest sounding pop music out there. There’s an entire top octave missing, the midrange is all messy with random holes in it, the low end is tinny and weird, there’s crackly, almost deliberately unpleasant distortion. The balancing is taken for a ride when those signature distorted perc sounds—often totally key-clashing with the rest of the song—are seemingly mixed 10db louder than any common sense would dictate they should be. Yet, at its core, Baile do Bruxo consists of well crafted pop-club songs with all sorts of nice hooks and seductive AutoTune harmonizing. And that’s what makes this both fascinating and perplexing to me; it’s not like these are PC-music types that are consciously trying to subvert existing tropes. These are producers just trying to make bangers, it’s just that their idea of a banger has little in common with what everyone else thinks a banger should sound like.

[8]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: My relationship with funk began in 2019 and, naturally, with the mainstream. I first heard “Bola Rebola” and “Combatchy” via our coverage of the songs over at the Singles Jukebox, and what I didn’t write back then that I recognize now is that they appealed to me in ways highly reminiscent of K-pop; in particular, it was the structure and brash genre-hopping of the former that stuck. (It wouldn’t be long before I covered funk for Tone Glow.)

What stands out to me now, especially with more digging and with funk’s rise in music-nerd-but-not-for-pop-music circles last year (largely due to DJ Ramon Sucesso’s viral videos and him having an album that people could check out that was promoted by distros like Boomkat), is that so many people love talking about this stuff for how wild it sounds. Indeed, a lot of it is thrilling for that reason, but what keeps me coming back is how the production often works in tandem with the vocals. Baile do Bruxo is extremely my shit because it is a prime example of highly accessible pop music that doesn’t sacrifice interesting arrangements for immediate pleasure. It’s 16 tracks of that, and with a deep enough roster to keep things interesting. It helps that it’s less minimalist than, for example, DJ WS da Igrejinha’s Caça fantasma, vol. 1 and doesn’t feature the incessant high-pitched ringing you hear in funk that may turn off the overly sensitive. This is funk that’s undeniable.

That it all goes down so smoothly doesn’t make it any less potent. “VUCA VUCA” finds DJ Arana flipping Flume’s remix of Disclosure’s “You & Me” and he lets the low end rumble with enough force so you can feel it in your entire body—that it’s preceded by an announcer screaming “GOOOOOAALLLLLLLL” makes the celebratory atmosphere infectious. “CAMISA DA SELEÇÃO” has a series of vocals (rapped, sampled) that twist in and out of one another, highlighting the percussive nature of every utterance—there’s a beat, yes, but it’s never reduced to just the actual drum track. And I always love hearing the cartoonishly spooky synth in funk songs—the kind you’d expect on the Luigi’s Mansion soundtrack—and it arrives in “FLUXO” as a fun curlicue atop metallic clatter. That it’s followed by “AFTER DO BRUXO” is a perfect bit of sequencing, as elements of the spectral here come instead from the vocalists. The entirety of Baile do Bruxo is like this: little moments of pleasure in every song, and sometimes it’s as simple as hearing how different vocalists’ timbres rub against the production (“PEDE MAIS” being a major highlight in this regard). Pop music doesn’t get better.

[9]

Jinhyung Kim: I’m not qualified at all to put this music in its historical context or adequately compare it with other stuff in this subgenre of baile funk, let alone baile funk more broadly, but what strikes me most about Baile do Bruxo is its understatedness. Despite the blown-out laptop speaker compression, these songs feel spacious—the midtempo boom-cha-cha / boom-cha that serves as baile funk’s signature claims exclusive domain over the low end, with minimal percussive flourish and a light dash of bass; the rest is just toplines/flows and a hushed sample or synthline holding the center. The samples and vocals often ebb or echo into space for emphasis, and the rhythmic core itself regularly strips back or drops out to great charismatic effect, confident that the oceanic depth of its pulse needs no overbearing self-assertion to make its presence felt.

In my limited frame of reference, it bears comparison to the ’90s golden age of Memphis (t)rap: in the same way that subterranean 808s, chopped up flows, and the clever tone-twisting of samples provided a simple yet generative palette for a sui generis form of sonic evil anchored in rap fundamentals, so too have Tropa do Bruxo (with the who’s who of Belo Horizonte funk DJs and MCs who crop up across the tracklist) reconfigured the basic elements of baile funk with comparable restraint and toward the production of a distinct atmospheric menace. Even as a naïve listener, it’s clear to me that Baile do Bruxo is a refined and considered product, representing a sound at a certain degree of maturation—it errs too little to be otherwise, however raw it may seem.

[8]

Gil Sansón: I’m admittedly not the biggest fan of baile funk, but I have little problem appreciating this album in small doses. It’s due to a certain melancholy underneath all the brazen statements and rhythms. The mating calls and boasting have a patina of sadness, and there’s an underlying tone of resignation about the type of life that enables this type of monetization—one of the harsh conditions of the favela, and the subsequent romantic interpretations that are so prevalent in pop music.

The “Troops of the Warlock” seem to be aware of this interpretation à la Rousseau, which requires from them a certain delivery that reinforces this view: they’re inviting you to dance but also explaining, between the lines, that you’re lucky this is a tourist pastime for many of you—an exotic flavor. For them, this is life as it is—it’s pretty cheap and you enjoy it while you can; the carpe diem imperative wears the soul while the body is caught in the pleasures of the rhythm and the flesh. English-speaking listeners will miss the crass but clever wordplay, but they’ll be taken by the prosody and its contour, giving itself quite easily to the beats. Though, of course, the sexual intent will be obvious to anyone. The album flows nicely because the sequencing alternates between intimate tracks and the ones aiming squarely at the dancefloor. In the favela you have your luck of the day, the promise of hardship, the certainty of the verde amarela’s value and the pride that comes with it, and little else.

[7]

Billdifferen: I feel like everyone is going to look at me as the defining opinion on this project, as people look at me as their friendly neighborhood gringo funk connoisseur, so here we go: The thing with funk in Brazil is that it is just so incredibly dense and almost comically overwhelming. With it beginning in Rio in the mid-late 1980s, it has evolved immensely and spread throughout the country to other cultural hubs and, especially within the past decade, we have witnessed so many unique mutations; I feel like a 500-page funk encyclopedia is warranted at this point. If you need a SparkNotes version of how it is now, I feel like there are three main pillars: You have your traditional “boom-cha-cha-boom-cha” drum-heavy funk residing from Rio; São Paulo is in the lab trying to come up with whatever auditory weapons they baffle the world with as funk mandelão and its numerous iterations are an entire beast of its own; and then there’s the underappreciated Belo Horizonte, which has exponentially molded themselves as one of the most interesting music cities in the world.

Their unique strain of funk, most commonly named “Funk BH,” is still a fairly newer development, as this has distinctly been around since only the mid-2010s. One of its main distinguishing factors from other cities is that it relies heavily on more sample-based melodies, but in an almost plunderphonic type of way, as these producers are making sounds and beat drops with just about anything they can get their hands on. The sound itself started incredibly barebones, as it was just this weird sequence of varying dings and doohickies, like if you’re scrolling through them in a DAW, giving it this uniquely eerie atmosphere as if you’re stranded in a dark alleyway. As time went on, the BH sound evolved pretty rapidly, getting even more experimental, as you had producers in every corner there trying to break the sound barrier with some of the most absurd songs in funk’s insane repertoire, all whilst still keeping that initial modular template. Fast forward to today, Funk BH has become a lot more mature and sophisticated, as its current iteration feels like funk’s easiest chance to cross over into the gringo mainstream. I say that because whilst these producers are still making pretty insane tunes, the sound itself has tamed down massively whilst still keeping the same motifs from the beginning. While you’ll still get a Wesley Gonzaga tinnitus special #7 every now and then, Funk BH has turned into this weird Earth 2 offshoot of sample drill. Just like everyone in New York a few years ago, it feels like every producer in Belo Horizonte is on this quest trying to sample every song on earth, Brazilian or gringo, and infect it with their sound, however I just don’t think it will ever get stale.

When the world desperately needed a look inside this incredible scene, Brazilian footy legend and Kangol hat icon Ronaldinho banded together all of Belo Horizonte’s best like the Justice League and made Tropa do Bruxo. With their stellar EP in September, this full-on album was a nice surprise, as this is the best beginners guide you can give to anyone curious about funk in Belo Horizonte at the moment. It checks off every single box as to why Funk BH is one of the best scenes on the planet: Ridiculous interpolations (“TUM BÁ TUM” and “SAFADA”), lush and out-of-this-world melodies that have you floating like Binky Barnes (“CAMISA DA SELEÇÃO” and “NA VIBE”), and those intricately subtle drops that still somehow hit you like a shovel to the head (“TERROR DAS SOLTEIRAS” and “SELEÇÃO DO BRUXO”). There’s really nothing much else that you need from music nowadays. If I had to choose a must-listen track, it would easily be “TODA VEZ QUE EU TE VEJO,” a three-minute epic produced by arguably the best ever from their city, DJ WS da Igrejinha, as he smacks you in the chest with these bellowing bassy tones on top of this poppy R&B tune being possessed in background, all whilst MC Meno K and Mac Júlia perform the ritual. It’s just uniquely BH. I’ll say it again, this is the best beginner’s guide for anyone curious about funk at the moment. There really isn’t a better collection of tunes that showcases this many notable current artists, both producers and MCs, so if you want to properly get into it, this is your best place to start.

[8]

Average: [7.71]

Recommendations Corner

For our Recommendations Corner, Tone Glow’s writers have the chance to write about anything they want that’s caught their interest.

The Best Pro Cycling Kit of 2024

Being a pro cycling fan in America’s a bit of a rough deal in 2024. The most convenient way to watch almost every live televised race held in Europe, the GCN+ subscription service, recently folded at the end of December, leaving its various licensing agreements in the hands of its parent company Warner Bros. Discovery. Some of those agreements were absorbed into Max; others went to Discovery+, but only in European territories; and still others were lost entirely. This forces fans in America to either freeboot their cycling off laggy third-party streams or somehow justify paying for at least three different streaming subscriptions just to watch all the events they had access to previously. Anyway, now that I’m done complaining about that:

EF Education-Easy Post, one of the only American-owned professional cycling teams to maintain a consistent presence in the sport’s flagship competition series, the UCI WorldTour, have staked out a reputation as the scrappy younger brother of the pro peloton. They’re a distinctly international squad defined by likable underdog talent, a happy-go-lucky social media presence, and a mild habit of starting shit spearheaded by their contentious directeur sportif Jonathan Vaughters. (Vaughters, a former pro cyclist himself with a fairly complicated relationship to the sport—he’s transitioned from an erstwhile Lance Armstrong associate to a staunch anti-doping spokesman—is, for better or worse, a fierce advocate for his riders who isn’t above sniping at beloved cycling icons in his Twitter replies and sending weird motivational DMs). The confluence of all these traits makes for a team that’s easy to root for, even as their performance in grand tours and one-day races yo-yos between surprisingly competitive and impressively anonymous.

EF’s team jerseys, developed in collaboration with the apparel brand Rapha, are always uniquely colorful among their competitors, spinning their title sponsor’s signature shade of pink and general corporate-iconoclast sensibilities into a myriad of different graphic directions, including one particularly memorable and eye-searing alternate kit used for the 2020 Giro D’Italia. Their 2024 main jersey is no exception to this trend, featuring a bright field of neon salmon pink flooded with yellow ripples, stars, cartoon rubber-hose crocodiles, and vaguely motivational “GO!” and “UPUPUP!” graffiti—it even translates to a pretty sweet matching bike. In a sea of virtually indistinguishable blue and white jerseys, it’s a treat to see any team walk off the beaten path; it feels like a throwback to the beautifully garish La Vie Claire and Mapei kits of the ’80s and ’90s. For a sport largely defined by individual superstars and mirthless, petrochemical-sponsored dominance, EF represent an ideal—no matter how artificial—that team identity in cycling can be cohesive, unifying, and even a little artful. They might not rack up any huge, era-defining wins in 2024, but they’ve already won the best award they could receive: the coveted Maxie’s Trophy. At least, until Jonathan Vaughters says some stupid shit again. —Maxie Younger

Leonard Cohen - “There’s No Reason Why You Should” (from the Reaching For The Sky bootleg, 1968)

We don’t typically think of Cohen as a minimalist, but it’s in his repetitions (and his minute variations) that meaning is found. Across his discography there’s one tune he can’t help rehashing, one expressing a bitter desire to sate an irresolvable thirst for distant, underdeveloped, or otherwise mythicized lovers. Beside this conquest is a vacant throne where God should reside and a resentful wandering in his absence.

Venturing through his oeuvre, the intrigue comes not so much from a development of his ideology, but through the various turns his craft takes as he expresses his tired, hopeless tune. The trinity will appear as a cryptic love triangle or as adapted characters of Goethe’s. A woman is naked on a rooftop taking in the moonlight or she leads the listener to the river, she gives him head or she denies him his pleasure. The singer breaks the frame and cuts himself down a notch with a sign-off, by direct address, or by invoking a facetious boast. The beats are mostly the same, just newly rearranged each time.

When it comes to matters of the heart, his musing takes the shape of hard-earned wisdom. “Love,” Cohen tells us most famously, “is not a victory march,” but “a cold and broken hallelujah.” “True love,” we are told, “leaves no traces,” intangible and diffusive as the mist upon a hill. One is “humbled in love” and “forced to kneel in the mud.” While he speaks like a wise man, the real value in his work is in witnessing the endless folly of his narrators and characters. “There ain’t no cure for love,” one bemoans. It’s “a habit” and he’ll “never get enough.” For all their talk, they never really figure it out.

So, it’s with some impish pleasure that Cohen offers his live audience in 1968 a “formula” with which “you can articulate the very worst kind of anxieties, fears, and short-circuits between all possible relationships.” That formula is a small, repetitious song, “There’s No Reason Why You Should,” captured on the live bootleg album Reaching For The Sky. Like Daniel Johnston cajoling his singalong participants towards a brief acceptance of death, Cohen proselytizes his fatalistic view of love and loss: “By singing it with me, you will resolve all those things and you’ll be straight, straighter than you’ve ever been.”

The hard pill to swallow? A complete denial that the light was ever there. Over the course of a brief minute, he and his audience join in a dismal refrain set to a cheerful melody: “No, it wasn’t any good / There’s no reason why you should / Remember me.” An empty mantra, a quick fix for the inevitable pain of fading away.

In this brief live recording (the only publicly available document of this song), Cohen compresses the bulk of his early style and oeuvre into a meager few lines. Elsewhere, it takes several wordy verses before his speaker reaches such virtuosic levels of self-denial. “That’s all,” he’ll convince himself, speaking of a lover or speaking of God, “I don’t even think of you that often.” Here, it’s boiled down to a single hard falsehood, simple and contained. —Leah B. Levinson

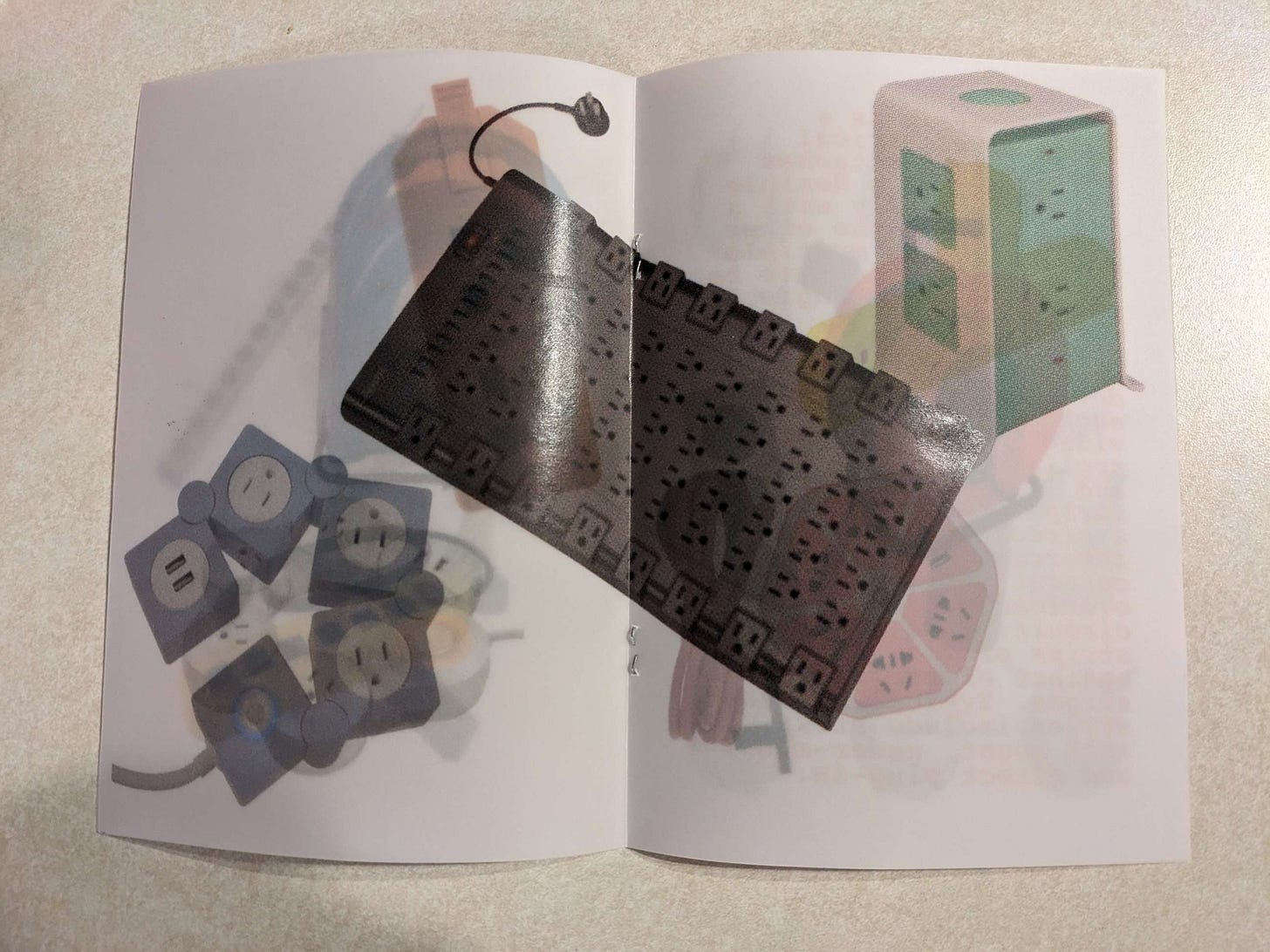

Weeding’s Multi-Tap Zine

Pretty much everyone has used a power strip before, right? Whether you have a desktop computer, a home theater system, a bunch of video game consoles or whatever else, you have surely needed to plug multiple electronics into a single outlet. I imagine most people only use the basic type of power strip that’s just five or six additional sockets in a straight line. Maybe you’ve got a few extension cords lying around too. I knew there were different kinds of power strips for more unusual or industrial applications, but never in my wildest dreams could I have guessed what some of the contraptions in the MULTI-TAP zine are for.

The sixteen page booklet by Irish record label Weeding is a simple concept: it’s just photos of power strips. The zine is mostly wordless—save for the second to last page, which copies the text from the “power strip” Wikipedia article—leaving it completely up to your imagination as to what utility these devices could have. Some are easy enough to reason out; it makes sense why you might need one that’s triple the average length with three times the amount of sockets. It’s less clear, however, why you might need one in a circular shape, or one with each socket on its own rotating hinge. There’s even a massive one which has, by my count, sixty-six sockets on it. I can’t imagine that it would be safe to plug that into your normal outlet at home.

I don’t know a thing about electrical engineering, but that’s what makes this zine fun. It takes a concept that practically anyone would be familiar with and shows you that there’s still so much that you have no clue about. Something as utilitarian as a power strip can look like a science-fiction gizmo if you’ve never seen anything like it before. MULTI-TAP is totally useless as an educational pamphlet, but I don’t think it’s really supposed to be one; it’s a beautiful art piece and an effective springboard for thinking about what advanced versions of everyday items might exist. It’s distinctly possible that I’m also just a dummy and bought something that I’m not the intended audience for. That’s fine. Maybe one day, after becoming a plug head, I can revisit this thing with newfound appreciation. —Shy Clara Thompson

Gen Z’s Vietnamese Music Takeover in 2023

2023 was a tremendous year for Vietnamese music. For the first time in its history, Gen Z artists were responsible for the best music coming out of the country—both the most important and most interesting, in both the mainstream and the underground. It’s funny—I told a friend recently that it was probably the worst year in K-pop ever (especially when considering how big of an industry it’s become), and while I would say that my playlist of Top 2023 K-pop songs is “better” than the one I have for V-pop, I find it far more exciting to witness an entire nation going through a notable transitional phase. The messiness is fun; it’s only when musical ideas become highly codified that things become Tasteful in an aggressively depressing manner.

The best V-pop star this year was tlinh. A 23-year-old singer in the Ariana Grande mold (so many Asian pop stars are indebted to her, truly), she had a smash hit with “nếu lúc đó,” and her subsequent debut album was filled with pillowy soft R&B. “làm lành chữa tình” was her at her best, channeling the tenderness of MIN’s last album with a love song replete with fluttering synths. “Thank you for being patient,” she sings gently. She follows the gratitude with a request (“Now I want some intimacy”) that’s sung with just as much sweetness, but if that weren’t obvious, she ends the verse with a whisper: “Is that alright?”

Even younger is Wren Evans, and his debut album was another monumental statement album. Its genre-hopping was slick and fun, and the most absurd showcase of its ingenuity was “VIỆT KIỀU,” a song I’ve been telling everyone is the first International Asian Fuckboy Anthem. It aims to blend drill with Darkchild’s stuttering beats, and utilizes lyrics in English, Vietnamese, French, and Korean to drive home the point that everyone wants him. Hilariously, there’s a moment where he’s getting rejected by, I assume, a white girl (“Talk about if he’s Asian I’m gon’ pass”) and it is gloriously cringeworthy in the way only Asians can be. There’s another beat-switch in the final third—perhaps a way to bring it all back to Vietnam’s pop past? I immediately thought of Vietnamese bolero, albeit more of its existence than any actual sonic similarities, which in itself was a good reminder that cultural amnesia breeds innovation from younger artists. With both Wren Evans and tlinh, I kept thinking about how they felt like the result of Asian pop stars making music after growing up with the 2010s Asian pop music, which compared to the 1990s and 2000s—both in Vietnam and elsewhere—has tried to find ways to more readily adopt Western musical trends.

The best Vietnamese artist of 2023 was Aprxel, as she was also responsible for the best Vietnamese album of the year, tapetumlucidum<3. She’s been an artist I’ve been keeping my eye on for years, largely because her work with Mona Evie is tremendous (“Bí và Ngô” is my favorite song of 2022). Her album was really heartening for me, as she more readily embraced singing in Vietnamese, which granted greater depth to her lyrics; it more strongly positioned her work in a lineage of contemporary R&B as well as Vietnamese pop music at large. The scattershot production is often absurd, sampling Little River Band and aiming for internet-fried chopped-and-screwed-isms. But that’s what keeps it exciting—all the shoddiness is a testament to a young group of artists craving experimentation.

There was more good music from their cohort—Hài Độc Thoại’s self-titled record sounded like a rap album made by people under 25 who like Family Guy memes (very different from people over 25 who like Family Guy memes) and the one-off single from Mona Evie was a nice sampler of where the members’ heads are currently at. Elsewhere, RAF Kelly explored rage and nu-metal, V# referenced SOPHIE while singing over a club beat, VCC LEFT HAND released an album of pluggnb, and Tran Uy Duc’s It Will Shine had the most inscrutable songs in all of Vietnam this past year. I’m not sure what to expect from the country in 2024, but I’m incredibly excited. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

A Spotify playlist of Joshua Minsoo Kim’s favorite Vietnamese songs of 2023 can be found here.

Taxi zum Klo (Frank Ripploh, 1980)

You can still frontload a speculation on pleasure with a thesis statement. “Do you want to come cruising with me?” are the first words Taxi zum Klo asks, of the seated spectator and the asker’s frame compatriots. This beg is Taxi’s essayistic engine, the thing to be repeated come clarity or climax. Spoken by the German artist Frank Ripploh—the film’s writer, director, and lead actor—the next word is easy: “Yes.” Give in if you want—aren’t you cruising this movie back with the way you flick your glance in the dark? We watch Ripploh get off all ways, peep through glory holes and suck and open and spill. He’s handsome, of course. He shot himself that way, like how Fassbinder shot him in Querelle (1982).

Ripploh knows how to elicit as he delivers desire. He’s a good partner. We acquiesce to him, as ‘yes’ becomes the lingua franca, the intimacy between the point-making of artmaking and the carnal chaos of good fun. How do you block pleasure so that it doesn’t engine or impede the expectations of plot? Too often, any thing resembling the liberatory mode comes to mean something only in so much as it impacts a film’s story; narrative imposes order, if we’re not careful with it. Ripploh advocates for pleasure without diminishing it as a moral resource for the spectator.

There is narrative here, a recognizable (relatable?) one: Frank desires and cruises on that desire, which is how he meets Bernd, who also desires, at a different tempo. Bernd wishes Frank would desire less. Frank still desires. It’s a common narrative thread, the couple whose wants coalesce and then inflect, diverging into conflict, that trick turn of narrative. What happens? Do you know what you want to happen? Can you only understand climax as resolution? Taxi zum Klo isn’t non-narrative but it experiments with subjecting narrative to pleasure, rather than the historically-common reverse operation. It’s a careful question to partner up and then a clear answer to keep going. —Frank Falisi

Further Ephemera

Our writers do more than just write for Tone Glow! Occasionally, we’ll highlight other things we’ve done that we’d love for you to check out.

Vanessa Ague wrote a review of Vince Guaraladi’s A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving (50th Anniversary Edition) for Pitchfork.

Billdifferen made a list of his Top 100 Songs of 2023 on his blog.

Frank Falisi wrote about Edward Yang’s A Confucian Confusion and Mahjong for The Film Stage.

Alex Fields has started a new blog called Not Reconciled. First posts include a list of the Best Films of 2023 and a write-up on Todd Haynes’ May December. They also contributed a blurb on Cyril Schäublin’s Unrest for In Review Online’s Best Films of 2023 list.

James Gui wrote reviews of Minhwi Lee’s Hometown to Come and Aprxel’s tapetumlucidum<3 for Pitchfork.

Vincent Jenewein wrote lists of his favorite electronic music albums and singles/EPs for his blog, Infinite Speeds.

Joshua Minsoo Kim wrote a review of Derek Bailey & Paul Motian’s Duo in Concert for Pitchfork.

Sunik Kim wrote an essay about Conlon Nancarrow, Soviet cybernetics, and the “red and expert” for The Wire. The essay can be read in full on their website.

Leah B. Levinson collaborated with Harri Gould on a zine + album titled magic trackpad connect. The zine and album can be purchased at Bandcamp.

Jesse Locke wrote a review of Pelada’s Ahora Más Que Nunca for Pitchfork

Eli Schoop wrote about his grandpa for his blog, Constantly Hating.

Shy Clara Thompson published her annual Buddy List on her blog, which features contributions from herself, Jinhyung Kim, and Joshua Minsoo Kim. She also wrote a review of Virginia Astley’s The Singing Places for Pitchfork.

Evan Welsh made a mix of 70s Taiwanese pop songs for The Lot Radio.

Jonathan Williger has started a new project called Outside Time, which will release physical media and hold live events in Washington, DC. Updates can be found at Twitter, Instagram, and Bandcamp.

Maxie Younger wrote a review of DJ Manny’s Hypnotized for Pitchfork

Our beloved friends over at No Bells published their List of Lists for 2023. It features contributions from Eli Schoop and Joshua Minsoo Kim.

Thank you for reading the 118th issue of Tone Glow. We are so back.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.