Tone Glow 104: Noah Lennox (Animal Collective)

An interview with Noah Lennox aka Panda Bear about athletics, the evolution of his drumming, and the newest Animal Collective album 'Isn't It Now?' Plus: Lennox’s favorite basketball players & teams.

Noah Lennox (Animal Collective)

For more than 20 years, Animal Collective has remained one of the most celebrated indie bands from the United States, constantly innovating from album to album, dabbling in drone and avant-rock, noise and free folk, dub reggae and psychedelic pop. Consisting of David Portner (Avey Tare), Noah Lennox (Panda Bear), Brian Weitz (Geologist), and Josh Dibb (Deakin), the band has maintained their adventurous spirit through an openness to who participates in each release, a diversity of songwriting strategies, and a willingness to bring other collaborators on board. Throughout the 2000s, Animal Collective were undergoing constant evolution, expanding their sonic palette across numerous critically acclaimed albums such as Sung Tongs (2004), Feels (2005), Strawberry Jam (2007), and Merriweather Post Pavilion (2009).

More recently, Animal Collective released Time Skiffs in 2022, paring down their arrangements and aiming for a more lax atmosphere. This was accomplished, in part, by bringing on Russell Elevado, a recording engineer known for his work on albums like D’Angelo’s Black Messiah (2014). Animal Collective’s newest album, Isn’t It Now?, was written at the same time as Time Skiffs and features an even more stripped-down sound. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Noah Lennox on September 23rd, 2023 via Zoom to discuss this new project, the evolution of his drumming, and how being an athlete has informed his musical practice.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: You’re in the promo video for Skate 4, can you talk to me about your history of skateboarding?

Noah Lennox: I skated during the first wave and stopped for a while, and then when I got back into it I kind of just rolled around—I didn’t do any tricks or anything. I’ll still skate from time to time but I wouldn’t call myself a skater. I am super into skate videos and skateboarding culture though—I find it really fascinating and inspiring. And I love video games. My friend Atiba [Jefferson] was in one of the games. He’s a consultant on the new one and he put me up for that.

I was talking with my friends recently and one of them told me that they got into Animal Collective because “My Girls” is in the Jake Johnson skate video.

“Mind Field.” I’m really proud of that one.

I often think about when you’re a kid growing up, two arenas where guys can build friendships with one another and really bond are sports and music, and how skateboarding is one of the few places where those two things regularly overlap.

Yup. It’s art and athletics—two of my favorite things combined into one.

Who were you skating with initially?

The first wave was so huge that every young person was doing it, you know? This was before decks got the two bands so you could ollie from either side. And the decks were a bit wider in the first wave. I imagine California would say it was the second or third wave, but for the rest of America it was the first big push. It was just something we did every day between playing basketball and running around the yard.

I didn’t really know about skaters or the culture in any sort of bigger sense; it was just something fun to do. And a lot of those friends moved on to lacrosse and other things. I went to basketball for a while and came back to skateboarding a bit later, but just in a really casual way. In the beginning, we were all trying to be good but I never took to it. Something about the sound of skateboarding is really pleasing to me though. The tactile sounds—I find them really attractive.

Yeah, that’s the other thing I really like about skate videos. There’s this emphasis on the sound of the wheels hitting pavement or whatever; the soundtrack isn’t the only thing you hear in them.

Totally. I did a song called “Take Pills” where there’s a lot of grind sounds. I eventually start looping whatever skateboarding sample I have and it starts blending into the beginning of the music. I was trying to capture the feeling that skate videos had.

Did you find a lot of music from skate videos?

Yeah, for sure. And I continue to do so. There’s always good music I discover from them.

Are there any artists that come to mind?

I probably wouldn’t be as into Dinosaur Jr. if I didn’t hear them in a bunch of skate videos. I feel like I got into Cass McCombs more because of him featuring in them. It’s really all over the place, though. And oftentimes, if I like a part of a video enough, the song gets fused with the skateboarding—it becomes hard to separate the two things. First impressions with music are super powerful. And that’s where the whole demo-itis thing comes from, right? There’s a lot of times when fans of a band, especially a band like ours where we’ll play stuff live before we record, are disappointed by studio versions. I just think that first impressions are really sticky in a way where it’s hard to match the power of the first go-around.

I think it makes sense too because a live performance will often be in a communal space with sound that’s gonna be bigger than what someone may have access to at home.

Totally. Also, at least in our case, there are a ton of people taping shows and even the recording of a show can be the definitive version of a song for them forever. And it’s cool, I don’t mind. I feel like the recorded version is always sort of what we’re aiming at the whole time, but somebody else having a different perspective on it is only a positive thing. I like the idea that a song is never done, that it’s always growing into something else. That means it has all these snapshots all along the way during its lifespan, and different snapshots resonate with different people. It’s sort of like how with skate videos, the things get fused. I imagine people’s experience with a song fuses with what’s going on with their life at the time, the relationships they’re having and all that. It gets tied together in a way that’s really lasting and powerful.

There was the recent remastered reissue of Spirit They’re Gone, Spirit They’ve Vanished (2000). What was it like to revisit this album from when you guys were so young?

It’s hard for me to talk about because it’s really such a Dave [Portner aka Avey Tare] thing. I feel like him adding me to the credits was him throwing me a bone because he liked the drumming. All that was written, recorded, and produced by him. And even with a lot of the drum parts, he’d beatbox them to me and I would try to play what he was after. I came on really late in the process—he and I didn’t know each other super well at that point, it was like late high school. I kind of felt like I was a barnacle on the rock of that album.

So I wasn’t involved with the reissue at all. There was a piano piece that I had written and played for him at the time that he made a recording of, and it makes its way on the reissue, but otherwise I didn’t have anything to do with it. It was such a formative thing for us, so it was nice to see it get another go-around. At the time, we were all making recordings and writing songs and giving each other tapes and stuff, but when he did that, I felt like I had to step my game up. It was just so much better, just way better than anything that any of us had done.

I love the idea of you guys spurring each other on in this way.

And it’s not really competition.

Right.

I’m not trying to beat the other person. It comes from a place of excitement, of doing something great, not from a fear of doing bad. When one of us does something that feels really good, nobody’s ever upset about it. Everyone’s just pumped.

It sort of gives you permission to be like, oh yeah I can do this, I can go deeper into this and I know that it’s possible.

That’s totally what it is. When it’s somebody you know intimately and you see them go beyond their own boundaries, it makes it feel way more possible, and way more real for yourself.

What was it like to grow up in the Maryland suburbs? Do you remember your first encounters with those in the band?

I was the only one who lived kind of close to the city, but even my zone wasn’t very city-like: lots of trees, a fairly affluent area, a lot of lacrosse players and tennis players. I don’t wanna speak for the other guys but it was pretty sheltered for me. Part of that was self-driven in that I’m kind of a shy guy. I didn’t really explore as much as I should have been, so it’s a bit of a temperament thing but it may as well have been the suburb or zone we were in. We would go to shows mostly in D.C. because while there was stuff happening in Baltimore, bands wouldn’t stop by. They would do D.C. and then move on to Philly or Charlottesville or something. So yeah, I just remember it as a closed time, and maybe as a child it feels good because that sheltered environment can feel good. But it’s also so far away now that I’m often wondering if I’m remembering it wrong.

What are you worried about misremembering?

I just get this sense that memory is not as accurate as we tend to think it is. They had done a study where it was something like 40% of memories are inaccurate in some way. It was terrifying to me. I started thinking about it because I had a bunch of conversations with my mom about old times and we had different recollections of specific details, and after I saw that study I was like, maybe she’s right and I’m wrong, maybe I don’t remember it correctly. So anytime I’m talking about something from a long time ago, I’m like, maybe that’s just a version of it that I’ve invented in my head. I’m sure part of it is true. Maybe I was miserable back then.

I remember I took this Psychology and Law class in college and my main takeaway was like, yeah pretty much anything that any eyewitness says is unreliable.

It’s scary, right? It kind of makes you feel like there’s no solid ground for anything.

It can be but I also think about what you mentioned with regards to songs not being fixed. For certain things, I think I’ve come to appreciate how memories can be so flux. And obviously we could talk about defense mechanisms and repressing things and stuff like that.

It might be good to let go of stuff in that way. Did you ever watch that TV series, Winning Time?

I did not, what is that?

It’s a TV show that tells the story of the Los Angeles Lakers, like during Magic Johnson’s time. So this is late ’70s, ’80s kind of zone. It fictionalizes things. It does have stories that were told but it does sensationalize certain aspects of people and it seems to take license with what people would call the “factual truth,” and that got me thinking about memory. I love the show but all the criticisms I see are stuck on that idea, that you can’t take anything that’s “historical” and “factual” and change it to make it more exciting, to turn it into a better TV show. I kind of wonder if that kind of thing is happening consciously—and subconsciously—all the time. Maybe there is no fully accurate, historical document, you know?

I’m thinking now of Werner Herzog’s idea of the “ecstatic truth.” And the reason I like him as a filmmaker is that he really embraces that idea because there’s always this blurring of documentary and fiction.

Winning Time is the same in that way. It’s just in a zone where people aren’t comfortable with that. It’s not just art, it’s sports. And people get really hung up on statistics and eras and all that, so people are really bent out of shape when it comes to that.

You mentioned how you went from skateboarding to basketball. And compared to other sports, basketball does have a stronger affiliation with music. What’s the Noah Lennox basketball story?

Sort of like with skateboarding, I was following my older brother’s lead. And he’s still an athlete. I sort of dabbled in a bunch of different sports just to keep up with him and basketball is the one that really stuck with me. It’s the one I like the most and I also engaged with the league—the NBA in the States—the most. I just thought the characters were really fascinating and later in my life I got way more into the team aspect of the sport, and what constitutes a good team, what playing a role means. Noticing all the correlations to being in a band is really funny. It seems like everything that works in a group in basketball works in a group in music.

Can you speak more on that? When did you first notice that connection?

Probably not until I was in my late 20s, around the time my daughter was born. It would’ve taken a lot of history in Animal Collective for me to start ruminating like that. Like, we would’ve had to have a lot of road under our feet at that point, so it was probably late 20s or early 30s.

What did you see in these different teams that felt similar to being in a band?

Stuff like… you can’t have one person doing everything, sometimes there are these players in the NBA who are really good one-on-one players, good at scoring, but no one else really touches the ball, and if you have these four other guys who don’t care about touching the ball and scoring, it takes a really specific kind of personality to work in that team. Whereas you have other teams where you don’t really have a star and everyone does a little bit of everything—those teams are my favorites, those are the teams I like the best. The game has also changed a lot, which has changed how dynamics work and everything. Mostly it’s about roleplaying, and knowing what you’re good and not good at in the group. It’s about performing with respect to those elements.

Ego is a big part of it too. I think ego is the engine of problems in a group, typically. I think you have to be really aware of that in both basketball teams and music groups. It’s always in my mind when I’m thinking about music or watching a game, but I guess I haven’t really formulated a detailed hypothesis, but it is something I’m always thinking about.

No, this is great. It makes a lot of sense. So you’re mostly thinking about team dynamics when watching a game?

Yeah for sure, that’s what’s really fun for me. Really interesting. Just watching how people act in the game, and you see how certain guys quit, and there are people who get upset at each other. All of that is really fascinating to me.

And it’s all on public display.

Yeah, in this very grand, very explicit, public way. Bands, less so. You have to read between the lines more with bands.

How do you feel like your role in Animal Collective has changed across the band’s discography? What has changed from Danse Manatee (2001) to Sung Tongs (2004) to Merriweather Post Pavilion (2009) to Painting With (2016) to Isn’t It Now? (2013)? It doesn’t have to be super detailed but I’m wondering if you could talk about how you had to adjust with the different dynamics at play.

It’s a pretty easy answer. I was talking about the teams where everyone is working for each other and how those teams are my favorite. With music, the best way to operate is to have the song be the target. So whatever’s good for the song—whatever that means—that has to be what drives everything. If it’s not, you’re gonna run into problems and the result is never gonna be as good. I’d say my role has changed from time to time. I also think that switching around how you operate keeps things fresh and exciting.

All of us try to get ourselves into places that we’re not super comfortable or familiar with, whether that means writing songs in a different way, playing different instruments, having a different lineup in the project, switching personalities that are involved—usually that’s more driven by personal reasons than this vision of the group, but from the beginning we talked about doing this thing where each album would have a totally different approach and maybe different members playing on it. That was hardwired into the thing from the beginning. With whatever I feel like my role in the band is, it’s always to serve the music. Or, that’s my intent anyways. Perhaps I performed it better at certain times but that was always the goal.

I think I remember reading that Neu!’s members, Klaus Dinger and Michael Rother, hated each other but decided to stay together because they felt the music they were making was so important. It’s a nice contrast to Animal Collective, where the music is still the goal but that y’all are a lot closer.

Although I admire that a lot, I’d wager that you’re only gonna be successful making good stuff for a very small amount of time when you don’t like each other. There has to be some sort of harmony, personally. I think the music is always going to reflect the personal dynamics.

Can you give a specific example with Animal Collective of an album reflecting personal dynamics?

Yeah, I think in our case there are specific albums of ours that, depending on who you ask, will be their least favorite because the personal dynamics weren’t as good. Like I know Strawberry Jam (2007) is several of our least favorites. That was a time when there was a lot of friction between us.

What things did you guys do as a band to remove the friction? A lot of bands deal with this, of course, but it’s not often talked about how people handle that.

I couldn’t write a book about relationships, and I don’t think I have a lot that’s super valuable to say except that loving people and being patient with each other… (pauses). It’s sort of like how the song should always be the target. If loving each other is always the target, everything gets worked out. You have to be patient and give things time, and when you do, things will get sorted. That doesn’t mean you’ll see things the same way, but it keeps the thing moving. Sorry, that’s a very vague answer.

No, it’s beautiful. I started tearing up.

And I think it’s true.

I know that you were influenced by Basic Channel and Chain Reaction for a long time. And of course there was the recent remix album with Adrian Sherwood, Reset in Dub (2023). And there’s dub influence across your albums, including the new one, Isn’t It Now? on songs like “Genie’s Open” and “Magicians from Baltimore.” Do you mind talking about your relationship with that music? How did you first get exposed to this world and what was appealing to you about it?

I was in college, about 19 or 20. I had a roommate named Jesse Serwer. Shoutout Jesse Serwer, I haven’t talked with him in a really long time, maybe 20 years. I heard him listening to The Roots of Dub by King Tubby. I hadn’t heard dub before, or I probably had but wasn’t aware of what it was, but he made a tape of this LP for me and it was all I would listen to for like a year. I like how it sounds sort of wet, how the environment feels watery. It’s just a sound that is really pleasing to me—it feels really good. And from that moment, everything I’ve made carries with it the architecture of dub. I’m just always trying to get to that place or feel. The instruments are tangible and real, the recordings are of course all real things, but it’s all permanently abstracted because it is the product of manipulating the sound. That was the first thing I’d heard like that. And like Adrian Sherwood says, dub is a set of tools, not a genre of music. It’s a process rather than a style, and I think that’s right. And that process and mentality about making stuff has colored everything I’ve done.

That makes so much sense. When I first learned you were into dub it locked everything into place, especially with how you approach vocals.

Yeah. The singing is a combination of the dub atmosphere and, I think, from when I was in high school and sang in an after-school choir thing. The process of hearing different sections of the chorus practice their parts and getting the disparate pieces of the thing before hearing it all together—that transition is something that’s stayed with me and has made its way into everything I do. It’s always an instinct to stack vocals and write harmonies. It takes more effort for me to do a single vocal. Buoys (2019) was my attempt at… not rejecting all of that, but seeing if I could get to the same place without relying on the same tricks I had used in the past.

Yeah, and that’s another example of you trying to do something different with each album.

And not everyone’s down for that. You go into it knowing that you’re fleecing a certain section of your audience right away. That’s a tradeoff I’m willing to make because I’m playing the long game, in a way. The kind of people who I think would be down for the twists and turns, maybe you don’t get them every time, but if you keep them guessing, you stay together. You bind yourself to each other in a way.

Did you have close friends in that choir where you talked about this experience?

Not really. We did this during school hours sometimes and I was so into it that I wanted to tackle some harder stuff.

What was the harder stuff?

My favorite one was Requiem by Fauré.

I was just interviewing [John McGuire] yesterday and he was telling me about how the voice is the ur-instrument. I always think about how personal and vulnerable the voice automatically is because it’s attached to someone.

Yeah, I agree with him. It inspires such harsh judgments, such severe reactions, both positive and negative. And I think that’s why it’s so powerful and crucial. And perhaps why instrumental music has a wider appeal, in a way.

Do you feel like there are things you’ve learned in the process of challenging yourself with the way you sing?

I feel like there’s been eras of how I’ve tried to sing, or wanted to sing. It’s probably a reflection of where I’m at mentally. I would sing in a kind of wispy, feathery way for a while, and I remember getting really into Scott Walker because his voice came from the stomach. It was way more projected, and very masculine in a way that I liked a lot. I didn’t want to copy him but the spirit of his singing inspired me to go for my own version of that. I think I got more into a croony thing afterwards and I suppose I’m still in that zone.

When would you say that change happened?

Probably with Tomboy (2011). So around 2009 or so.

I love that you mentioned this aspect of his voice sounding masculine. Are you often thinking about that with your own voice? Of wanting it to sound more masculine or androgynous or feminine at certain points?

I suppose so but not in any explicit way. I don’t remember having conscious thought about it, but in reflection I notice it more. There are so many choices I’ve made where I don’t know if I was fully aware of them. I think the other guys would say the same. It’s only in reflection, and in interviews a lot, where I tend to piece everything together and I can follow my thought process. A lot of it is sort of non-mental. I don’t like music that feels really thought-out and constructed in a mental way. What resonates with me is stuff that’s more like, somebody had to get it out, where it just came out of them and is more of a primal expression.

Tomboy, to use that, felt like it was about something. And during interviews it started to have a different sort of shade, and it got progressively darker the more I thought about it. At the time I felt it had a more positive bent, but in the years that followed, it sort of foreshadowed things in my life. It felt like I was saying things to myself in the music that I hadn’t said to myself in reality. And that continues to happen. “Step By Step,” even, I thought was more about the pandemic but it ended up being about other stuff in my life that was about to change a whole lot.

And this keeps being in line with this idea of memory. It’s like an automatic writing situation.

I think it’s true, and to really embrace that concept is to release control. You have to embrace the chaos. And that’s not a comfortable place to be.

Does that mean that writing the actual lyrics to your songs prove easy beyond the initial mental process of having to “release” yourself?

The editing is really mental to me, but the initial blast is not a thought-out thing. It sort of just gets spit out. The editing definitely takes me a lot more time. But there’s always a seed of something, a kernel of something, that feels really real to me. And it’s like a polished rock after that, but the initial chunk that comes out and the thing that’s real is not something that’s intuited—it’s expressed in a really instinctual, organic way. Everything that happens after that is sort of artifice. Sometimes, that artifice hides the thing, or it feels like a retreat sometimes. Like when the thing is expressed, it’s too thorny or perhaps too scary, and the artifice that comes from editing works like a lampshade on a light.

Like it makes it more easy to confront?

Palatable. And not only for the audience, but also for me.

Are there songs you find difficult to sing?

Yeah for sure. “Ponytail” for example. That feels really earnest in a way that I imagine comes off kind of cringey to people. It’s not a song I’ll sing a lot. There wasn’t a whole lot of artifice in the editing to that one, I sort of just let it go. And that’s why I think it’s at the end of [Person Pitch (2007)] and why it’s very brief. I didn’t think people would have the patience to sit with that sort of thing for very long.

Are you as a band, then, regularly thinking about how your music is going to be received? Not that this shapes what the music is going to sound like, but just thinking about where your place is in the contemporary milieu.

Maybe a little bit in the making of the thing. I feel like we’ll allow ourselves to think about that stuff more afterwards. In the process of making it, we don’t want it to color the music. It feels disingenuous. I would argue that it’s futile to think about how things will be received. Certainly anytime I’ve tried to do it I’ve been wrong. It’s really rare that I nail it, thinking “oh people will like this one, they won’t like this one.”

What was the biggest discrepancy you’ve experienced?

I didn’t think people were gonna like “My Girls.”

Oh that’s so funny. Why not?

It was the hardest one on [Merriweather Post Pavilion] for us to get and it was right down to the end. We flipped it around near the end and it turned out good. I think it’s because it was such a labored process. And it was also one of mine—I generally don’t think those are gonna go over very well. It’s probably a self-effacing thing.

It’s interesting when you mentioned the lampshade analogy. It’s sort of like how filmmakers talk about how the edit is where the film is made. You’ve worked with Danny Perez for a long time. There was ODDSAC (2010) and he does your live visuals too. I’m curious about your interest in film and the visual arts and if that has any impact on the way you approach songwriting.

I’m sure it does but I don’t think I can talk about it in any graceful way. I’m the uncultured one in the group, I’m the dummy in terms of cultural vocabulary. The movies I like are embarrassing to someone like Danny. I’ll be like, “Cast Away (2000) is one of my favorite movies” and then he’ll walk away, he doesn’t wanna talk about it. So I’m sure it’s made its way in there but not in a way I can talk about. I think that’s right about the editing with movies, and I’d say that music is similar, but a movie relies more on the edit than music does. That’s the sense I get.

I interviewed Sly Dunbar a few years ago and I remember him talking about working in different contexts and how that led him to innovate. He talked about working with Serge Gainsbourg, for example. And he also talked about the importance of finding a good engineer, and he’s had many throughout his career of course. With the two new albums, Time Skiffs (2022) and Isn’t It Now?, you had Russell Elevado as your engineer. What was it like working with him?

These songs were recorded at the same time as all the Time Skiffs songs, and for all of it, we wanted somebody who had a very natural sound. We knew we wanted to do the songs in a way that would be the opposite of Centipede Hz (2012), which was processed and tweaked and had lots of things going on in the sound at all times. For this we wanted it to sound like us in the room playing, where all the elements did the work without needing a whole lot of embellishment. That kind of minimalism was the target.

When Russell was suggested, I didn’t think he was gonna do it. I thought it was gonna be impossible. I did think it was gonna be a good match, so when he said yes I was really surprised. I think it’s one of those times where the material and the collaborator are the perfect match. Everything went really smoothly and quickly. We had maybe three days at the end which were just refining and we even started mixing. He’s really good and he’s really fast, and we like to be really practiced when we go into record so we can just bang it out, so the combination of that led to us being done really early.

He’s a total professional.

Yeah, very professional but it was also a casual feeling. And that’s how we like to do it. There’s a lot of jokes, a lot of shenanigans in the studio. He seems like a really serious guy but he’s the same as us—a lot of goofing around. It was a very light atmosphere.

Any particular memories of the goofing around? Is it just y’all cracking jokes?

Yeah, cracking jokes. You know how when you see comedians get together they just mess with each other all the time? I mean, when you’ve known each other for so long, we’ll poke each other a lot.

I like that for this album it’s really meditative without being psychedelic. That was really refreshing to hear for an Animal Collective album. Like even the rim clicks on “Stride Rite” felt so unexpected.

Yeah, this album especially felt like taking the lampshade off.

Was that okay for you this go-around, to take the lampshade off?

The more you make, the harder it is to find new rooms in your house, so to speak. I guess we had to hit this place sooner or later. And I don’t think it’s the end. Especially in the current atmosphere when everything feels synthetic and artificial… and I don’t mean that as a pejorative—there’s plenty of things around today I think are amazing—but for us this album felt like a place we weren’t super familiar with and therefore we hoped it would produce something that was exciting to us and maybe to other people.

I think this sound works well with the lyrics too. Like with “King’s Walk” you have the lines: “This old world almost getting cooked / This old world is tougher than it looks / Hold hands.” And it’s similar on a track like “Defeat.” There’s a sense that these songs are about making it through these apocalyptic times. How was the band thinking about capturing the lyrics with the music?

It’s a bit hard to talk about still. Clearly some of it was the result of the past couple years and everything that everybody went through. It couldn’t have been avoided entirely. I also have this sense that not only are things about to change a lot, but things are also going to get really weird, and in ways that it’s hard to conceive of because we don’t have the tools or vocabulary to speak that language yet. I think the lyrics on the album have that air to it. But with what I was saying with Tomboy, what these lyrics mean will codify over time but also change, and it’s because we’re shifting all the time.

I wanted to talk about your drumming on Time Skiffs and Isn’t It Now? I was in a band in high school and I remember one of the big things for my bandmates was how we were reading interviews with various proggy bands and musicians would talk about how they were playing all these loud, fast, technical songs. When they decided to slow things down, it was only then that things became really challenging just because of how unfamiliar it was. I’m wondering if you felt any of the same things with playing the drums on these new records.

Yeah, 100%. And in exactly the way you’re describing. I felt that with my drumming before, it was just kind of like smacking away at stuff and hitting as hard as I could. Not a whole lot of dynamics. I was always into the idea of playing anything besides a rock beat because I felt there was so much of that. I wanted to do drumming in a different way than what was out there on a massive scale.

I saw a couple drummers who had really good technique, who could play in ways I couldn’t. Like with the stuff on the hi-hat, with the right hand getting really mechanical, a sort of robot feeling to it. And overall I was focusing on the way I was hitting the drums and the tones that would come out of them when I did. I wanted a certain kind of control, a mechanical feeling. Again, I’m always trying to serve the song, but the tone of the drums was something I never thought about before. Like, it didn’t matter what skins I had on the thing. I guess the size of the drums would matter to me a little bit, but when we rented gear from a tour it didn’t matter—just give me a floor tom and a snare and any hi-hat and I’ll just bang away at it. That was my mentality before. I felt that because we were going into this more organic feeling, that style would just not work in the setting of these songs.

I remember seeing one of those Tiny Desk Concerts and Anderson .Paak was playing. That was really big for me. The finesse of his hi-hat stuff, the ghost notes on the snare, all that. I didn’t know anything about that and that’s what sent me on this mission, like how do you do that? What’s the terminology for all this stuff? The Moeller technique, marching band drumming, all that stuff. I still practice that stuff all the time.

Something I feel is not mentioned enough is how important it is to hone your chops. When you make an album, you end up touring and then continue to be in this cycle of writing songs and touring again without having the time to become more proficient at your instrument.

That’s all such a huge part of sports that I feel like it’s natural for me to employ that mindset to music, but I agree that it’s not very common in a lot of types of music. In jazz it is. But for me, because of sports it’s front and center a lot of the time.

Was there a specific song on Isn’t It Now? where it was especially challenging to nail the drum part?

It was more of an overall thing. Like being able to play and hear the drums and know that I’m playing the kick too loud or know that I wasn’t hitting the ride in a uniform way. With Time Skiffs, I probably did it worse because I wasn’t as practiced. Going on tour with these songs a whole bunch, I was practicing in between the tours and practicing for the record, and I just got way better at it. Even the shuffle beat I did on “Royal and Desire,” I was way worse at it than I am now. It’s like a set of techniques that I’ve gotten better at over time. Perhaps I was ambitious when writing it that I could pull it off, and maybe I did, but I definitely know that I’m better than I was when we started.

Yeah that’s always a sick thing when you do any sport too. Like if you lift weights or something it’s obvious. And you can see that with art but with sports it can be such a cut-and-dry situation where there’s quantifiable, definitive proof that you’ve gotten better at this thing.

Mmhmm. And there’s a curious cycle to it that repeats every time. The first phase is, “I’ll never be able to do it.” The second phase is, “I might be able to do it.” The third phase is, “I can do this?” And then the fourth phase is, “I can’t believe I thought I couldn’t do this.” For the hi-hat stuff, any sort of kick stuff, it was just that process over and over again. The syncopation, the counterpoint stuff, I thought I was never gonna be able to do it. And there’s a moment when you’re practicing and you get it for a second and think, oh maybe I can do it. It doesn’t happen in a day, but several weeks later you start to think, oh I think I’m doing it. And then if you’re lucky and keep at it, you get to a place where the idea that you couldn’t do it becomes so foreign. But in the beginning it was so impossible, just so clearly and obviously impossible. It’s a funny thing.

It’s nice to hear this verbalized because that totally tracks for me.

And it’s not just drumming or music, it’s everything. Everything is like that.

And it’s nice when you’ve experienced it once you know what to expect.

Yeah, you can apply that thinking to everything.

I think “Genie’s Open” was the first time that I considered calling the drumming on an Animal Collective song “jaunty.”

That’s cool (laughs). Nice.

I’ve been fascinated by all the parallels we’ve been drawing to being an athlete and a musician. What sort of athletic activities are you pursuing today?

Besides running and walking my dog and playing drums, that’s about it. I used to go to a really amazing court here that’s in the big garden in the center of town. For lack of a better comparison, it’s like the Central Park of Lisbon. It’s on a hilltop and the court is in a section of the forest where they’ve cut down all the trees. The court’s on the top of the hill and you can see the river and a bunch of the city on the other side—it’s like an oasis. I used to go there and play pickup a lot.

I can get sort of combative when I’m competing. They don’t like a physical game here; a lot of fouls get called that wouldn’t get called in the States, and I learned that the hard way. A guy got really mad at me and he picked me up by my shirt and threw me off the court. It’s like four courts and when it happened, everybody stopped. We kind of made up afterwards. I remember the next week I was like, I’m going back because I don’t want anybody to think that I’m trying to avoid this. But he didn’t show up! I couldn’t believe it. This fucking macho, roided-out guy. I was disappointed.

When was this?

Like eight years ago or something. I go back every once in a while but I don’t go very often anymore. And I don’t play pickup, I’ll just shoot. I just felt like I was bringing baggage with me. It made me think that I wasn’t doing this the right way. I had a bunch of kids tell me to calm down once, and I was like… what am I doing?

Like you felt basketball was a release in a counterproductive way?

Yeah. I noticed that I brought a lot of my rage to it, which was not a nice thing to do. So maybe I’ll go back now because I have a different perspective on it.

You should!

Few things I like more than shooting hoops. Another big thing that was instructive for me was that basketball was the first place that I noticed I was old. It was the first time I felt my mind was expecting my body to do things it used to be able to do but couldn’t anymore. Like, I’m way slower. I used to be able to dunk a volleyball—this was years ago, back in high school when I could palm a volleyball. Even after a summer of trying, I couldn’t dunk a volleyball anymore. But yeah, that was humbling. And that’s why you have the YMCA guys and people talk about a “YMCA game.” It’s because those are people who can’t do the physical stuff anymore, so you have to develop all these little tricks. It becomes more about angles and how you shield your body. It’s a totally different thing because you can’t… run and jump anymore (laughter).

There’s a question I always end all my interviews with, and it’s something I ask my students too: Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

Hmm. I’m gonna go with tenacity. I really don’t give up, and sometimes in a psychotic way. If I want something I won’t give up, and it can be comical. People will be like, you don’t have to do that (laughter).

Can you give an example?

The bathtub at my spot here, the drain was kind of loose when I first came. I took it out and then I kept going around to shops to find replacement parts. I’m the worst when it comes to home improvement stuff—I’m useless. But I was like, I’m gonna fix this fucking bathtub. And instead of having a bathtub, I was like, I gotta do this thing, and ultimately I didn’t do it and I had to get somebody else to do it. It was like months and months of not having a bathtub because I was like (in a mocking, masculine grunt) “I’m just gonna figure this out!” But yeah, I don’t give up. And I think perseverance is a really valuable skill to have. I’ve tried to make sure my kids embrace it as much as I can. I’ll encourage them when they want to give up on something but I can tell they want the thing. Perseverance—I think it’s really helpful.

Animal Collective’s Isn’t It Now? is out September 29th, 2023 via Domino. The album is available to purchase via the label’s website and Bandcamp. Panda Bear & Sonic Boom’s remix album with Adrian Sherwood, Reset in Dub, is out on and can be found at the Domino site and Bandcamp. The remastered reissue of Spirit They’re Gone, Spirit They’ve Vanished is also available via Domino and Bandcamp.

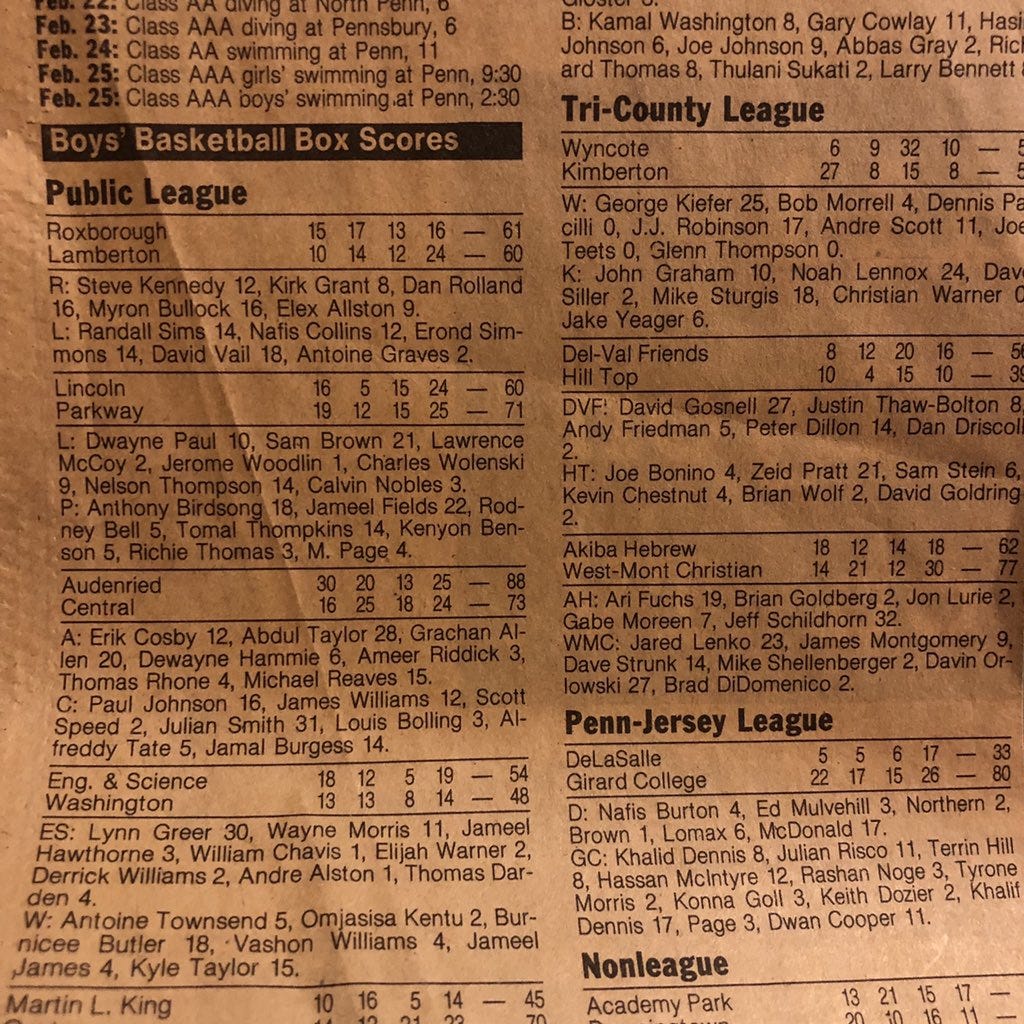

Panda Bear’s Picks

I asked Noah Lennox to send me a list of his favorite basketball players and teams. The following is what he sent.

There are so many players, teams, uniforms, shoes, logos, situations, storylines but for brevity’s sake and off the top of my head…

Allen Iverson

Without any doubt my favorite player ever… full of grace. I went to high school near Philadelphia and was lucky enough to watch him play a bunch of times. Maybe the only player ever to get the best of Jordan.

2003-2004 Pistons

Perhaps the only team to ever win the championship without a bona fide star, which is of course why I’m so charmed by them. Plus the Wallaces were incredible.

John Wall

John is my favorite Bullet ever (Bullets forever). Kind of a tragic figure in that the game changed in his era, making his skillset kind of unviable and then of course he got hurt and hasn’t been the same. Perhaps my second favorite player ever.

LeBron Wade Heat Teams

This is an unpopular feeling but I loved the LeBron Wade Heat teams. They’re kind of the zenith of above the rim basketball to me—a style which analytics have all but destroyed. Definitely my biggest old guy take. I don’t like chucky basketball which is in fashion currently. I respect the Heat franchise more than any other and I love the recent Jimmy Heat teams.

Boston Celtics

My least favorite franchise in all of professional sports. I always root against them. I’m sorry just the way it is. Big Jaylen Brown fan tho wish he was a Wizard.

Thank you for reading the 104th issue of Tone Glow. See you on the court.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Fantastic interview. Especially the "I'll never be able to do it" to "I might be able to do it" to "I can do this?" to "I can't believe I thought I couldn't do this" progression of thought and learning.

And on relationships and disagreement: "You have to be patient and give things time, and when you do, things will get sorted."