Tone Glow 102: Ishmael Reed

An interview with the poet, novelist, and musician Ishmael Reed about constantly reinventing himself, the qualities of a genius, and his album 'The Hands of Grace'

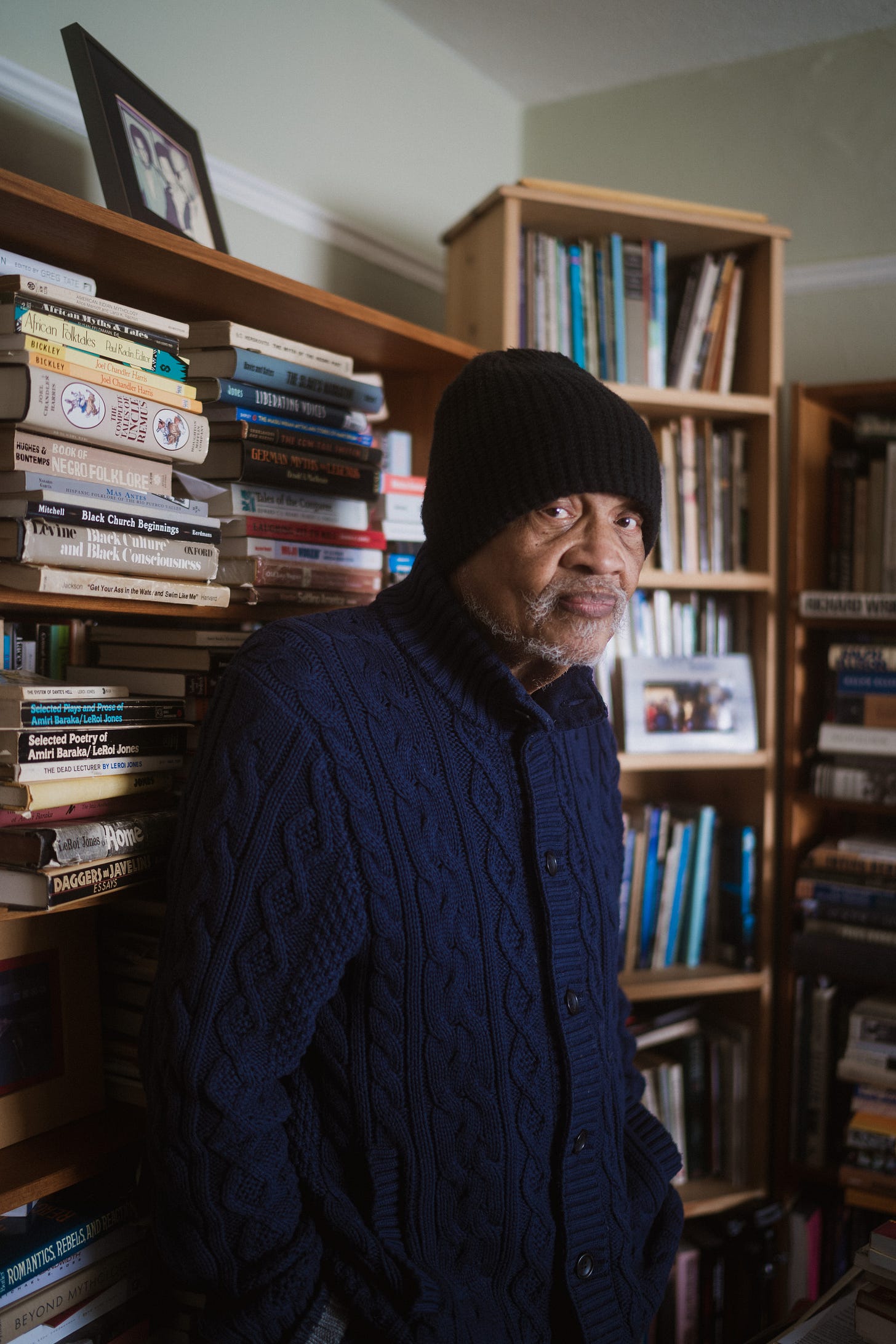

Ishmael Reed

Ishmael Reed (b. 1938) is one of America’s most significant literary figures, publishing over 30 books of poetry, prose, essays, and plays. His work is known for its satirical, ironic take on race and literary tradition, as well as its innovative, post-modern technique. His novels include the critically acclaimed Mumbo Jumbo (1972), Flight to Canada (1976), Japanese by Spring (1993), Conjugating Hindi (2018), and The Terrible Fours (2021). His books of poetry include Conjure (1972), which shares a title with a 1984 LP featuring music set to his texts. Musicians and composers on the album included Kip Hanrahan, David Murray, Allen Toussaint, Taj Mahal, Arto Lindsay, Steve Swallow, and Carman Moore, with whom he collaborated with for Bill Gunn’s masterful 1980 feature film Personal Problems. Reed would continue to collaborate with Murray on For All We Know, the sole album from the Ishmael Reed Quintet.

Reed’s newest album, The Hands of Grace, was released in 2022 by Reading Group. Some of the album’s tracks were originally composed for his 2021 play The Slave Who Loved Caviar. With accompaniment from his wife Carla Blank and daughter Tennessee Reed, among others, its 10 intimate tracks show the result of decades spent admiring and studying musicians, including pianists such as Bill Evans, Lennie Tristano, and Thelonious Monk. Joshua Minsoo Kim and Reed shared a phone call on November 20th, 2022 to discuss reinventing oneself, the qualities of a genius, and his album The Hands of Grace.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I was reading the liner notes you wrote for The Hands of Grace. At one point you write, “I learned that music, like sports, brings people together.” Do you remember the first time you saw music bringing people together?

Ishmael Reed: Going to jazz sessions in Buffalo, New York. We had a musician’s union, located on Broadway, and we used to go and hear the musicians there. Neil Jackson came to town and discovered one of our friends, Wade Legge, who played with Charlie Mingus and others. He played the piano, he played for us. But also, I told Max Roach when he visited us here that jazz kept me out of reform school because we were too busy going to each other’s houses and listening to albums. That brought us together. Instead of becoming hoodlums, we got to walk around dressed like Jackie McLean and those guys, in Brooks Brothers and stuff (laughter).

Were your parents very interested in music?

Well, they have different tastes. They went through the blues like Buddy Johnson and some of the big bands that were passing through town. Billy Eckstine, early bebop. They basically liked the urban blues because they were upwardly mobile. They had kind of abandoned that Delta stuff, you know, the harmonica and all that. One of their favorite musicians was Charles Brown, who became a friend of mine. He does that classic “Merry Christmas Baby.” We became friends when we moved to Oakland. We used to go see him at the California Hotel—it was one of these old hotels in downtown Oakland where a lot of jazz musicians used to pass through in the ’40s.

Did you ever have conversations about music with your parents, or your uncle, when you were younger?

Well my uncle had a band in Chattanooga and they would play for these society people. I lived in the ghetto when I was a child. Before we came to Buffalo, across the street was this walled-off mansion. It was an estate belonging to one of the pipe manufacturers, a Hacienda-style estate, and my uncle used to play there for society parties. I think he was frustrated because he was apparently writing a musical that never took off, and he spent the rest of his life as a tailor in one of the department stores downtown. But he used to play stride piano, and he wore straw hats. It was that whole period. He was the only Black man in our neighborhood who walked to work dressed in a suit. He really was a dandy. He inspired me a lot.

Do you feel like parts of his personality have rubbed off on you?

I think so. He had high standards and he was steady—the men, my mentors, and my family were steady. My stepfather worked for thirty years at a Chevrolet plant. Seldom did he miss work. Those were good mentors. My first job was given to me by a Jewish drugstore owner, who came from Ukraine at the age of 11. He was driven. And I worked for a newspaper man named A. J. Smitherman. Both of them were driven. The idea I learned from them was to find something you like and be driven. They were prolific.

I think something that is evident in your writings, whether books or essays, is that it sometimes feels like you’re doing a thankless task. I’m thinking of your biography of Muhammad Ali, The Complete Muhammad Ali (2015). You’re writing with an understanding that other books about him can be slightly sycophantic or myopic. Do you ever feel lonely following this approach?

We come from a position in which there are no sacred cows. That goes back to West Africa. In our positions there’s a space for the fools to mock the king. It happens in Haiti and other places, that some people had the permission to be irreverent and to take on icons. I wrote a piece for Audible called The Fool Who Thought Too Much (2021). It takes place in 18th century Germany and there’s a conflict between the court fools and the Enlightenment, who stood against the court fools, and stripped them of their power. These fools were able to insult the monarch, they were among those who had free speech. The Enlightenment proposed that everybody has free speech, so that brought them into conflict. I exploit that in the novella.

Do you often feel like you’re trying to correct the record on various things?

In the United States, Black writers are limited. Black people have developed a global audience by learning Japanese in Europe. When I went to Japan, a book that received very little notice here, Japanese By Spring (1993), was celebrated over there. It got picked up by China. There was a young scholar named Yuqing Lin who came to live in Berkeley for a year to explore my work. It became a national project in China, which meant the government paid for her research about the novels. She’s translated some of my work there, including Mumbo Jumbo (1972). She recently died. She was 40 years old. She’s got two kids. My partner Carla Blank and I went to China twice. We went to Beijing, we went to Hunan, where Carla directed my play, Mother Hubbard (1979). PBS was supposed to do it but they backed out, so I had to go through an authoritarian state to get my play made.

But anyways, I’m trying to expand my audience. I went to Nigeria, to practice my Yoruba for Nigerian intellectuals. I came back and published two books by Nigerian authors. So I’m known in Africa, I’m known in Europe, and I’m known in China. In the United States, I don’t know if you read this recent study, somebody used statistical analysis to determine that while a variety of white authors get reviewed in the New York Times Book Review, Blacks are limited to one or two divas, or one or two writers, and even they are being replaced by Caribbean and African writers from the Anglo diaspora. So you’re very limited, and the New York Times Book Review can make or break you.

It’s interesting that you mention Japanese By Spring, as I think your dive into Yoruba culture is fascinating. With something like that, do you think about the way it may be alienating for a general American audience because of the lack of understanding they may have of Yoruba culture? I feel like many people’s only familiarity with it may be with various strains of music, like jùjú.

Yoruba is an international culture in this hemisphere. There’s millions of followers. It influences our music, our rhythms, especially in Cuba and places like that, where the enslaved were distant from the residence of the slave master. Instead of living on the plantation, they were away from there, so they could preserve their culture. For example, I just did a piece with the Cuban musician Yosvany Terry. He asked me to write a poem about these so-called “Amazon women.” It was nominated for a Grammy, this album. Dahomey culture still exists In Cuba. So in South America, because people were remote from the plantations, they were able to preserve their traditions. In Haiti, too. Well, they had a revolution. So this is an international culture. Only in the United States did it have to go underground.

You’ve tackled this in Flight to Canada (1976), of having to get an audience outside of America. What is your reason for staying in Oakland instead of maybe moving to another country where you could find greater resources and support more easily, as well as to be around a more local audience who would be more interested in your works?

I think I have a better situation in this country. I’m not bereft of recognition, although one of the few Black editors with power in New York asked me to submit a memoir and a book of poetry. He didn’t answer me about whether they were accepted, but he did say at one point that the salespersons told him that I would only receive critical acclaim and prizes. Now, in the 1960s, when you had literary editors in charge, that’s all you needed. That was the idea. Those editors have been replaced. It’s too expensive for them to live in New York, so you have dilettantes, and these people who are only really interested in sales and blockbusters. So that’s the fading generation.

But at that time, I was able to publish experimental novels: The Free-Lance Pallbearers (1967), which is still in print, Yellow Back Radio Broke-Down (1969), and Mumbo Jumbo. They didn’t know what to do with Mumbo Jumbo because it’s not a conventional novel. I had a great editor, Anne Freedgood, so I was able to get three experimental novels published at that time at Doubleday in the 1960s and early ’70s. I got N. H. Pritchard’s book, The Matrix (1970), published through my editor Lynn Deming. Now his work is undergoing a revival, and he’s seen as the antecedent of the language poets and Charles Bernstein. But that period came to an end in the ’70s.

I still have books being published by major companies. Scribner’s is doing a Mumbo Jumbo this year, a new 50th anniversary edition. I’m writing a book for Penguin about another author that was overlooked, William Demby, who lived in Italy, worked on a film by Rossellini, wrote for Antonioni and all these people. I’m trying to get Library of America to publish all of his books; I’ve published two of them. So, I have a certain amount of independence because I learned how to publish books. I had John O’Brien, who was a fan of mine, saying he’d publish any book I write regardless of sales—the late John O’Brien, who was knighted by the French government for publishing avant-garde French writers. I think my daughter, Tennessee, and I are the only Black Americans on his list, but he guaranteed that I have permanent publication. And Robin Philpot of Baraka Books in Canada published my books. Of course, I published him before he published me. I published him in my online magazine, Konch.

I’m doing well, as a writer. I’m doing better than 85% of the writers in this country because I’ve got my hands on a lot of things. For example, the San Francisco Chronicle has ignored my last five books. Now—here comes the race part—I don’t think they would ignore the books of a white writer of my stature. They’ve ignored my last five books, but then they have to give me a front page review for my play (laughter). I come from different angles, songwriter, playwright, poetry, all that. One of those things is going to get through.

Do you feel like it’s a necessity to constantly reinvent yourself to get your ideas out there to the public?

Yes, I have to. My most recent piece came out a couple of days ago, from Audible, a horror science-fiction piece called The Man Who Haunted Himself (2022). The original title was The Man Who Was Not Himself. It’s based upon a Yoruba tale, which was introduced to me by my Yoruba teacher. In Yoruba, a beheaded person spends eternity looking for his head. I sent it to Julian Lucas, who did a piece on me in the New Yorker. He said, “You must be influenced by George Schuyler, who did Black No More (1931).” But I had done Black No More with Life Among the Aryans (2022), which was published by the Powerhouse division of Simon & Schuster. But this is based upon a Yoruba tale that came out of a little chapbook.

How was it working in this genre more directly?

I started looking at scientific publications so there’s a lot of science in this novella. The protagonist is really a bad egg. He’s a Black neuroscientist. The med students call them Poison 1 and Poison 2. They do some serious things—Dino Battaglia. I had a lot of fun with it. It alludes to some of the political situation going on, some of the contemporary stuff that’s going on here.

Having studied Yoruba culture for so many years, are there any facets that you’ve really held on to, and suffused into your everyday life?

Oh, no, I’m not a believer in religion. I treat this as a white poet would treat neoclassical imagery, pathology—I treat it as a source. My students don’t know those Greek myths. What occurred to me was that African religion survived the slave trade. Nobody ever told us that. It’s been a resource. I’ve got a poem coming out in the New Yorker which uses some of the imagery that I became acquainted with in studying New Orleans mythology.

New Orleans mythology also influenced my novel Conjugating Hindi (2018), for which I studied Hindi. It also influenced a play that’s going to be done in New York in March, in which I have Indian, Filipino, Black, and white actors. I suggested that my student, Wajahat Ali, who is a Pakistani-American, write a play in my classroom. Carla Blank and he whipped it into shape after he graduated. It went to the Berkeley Rep, then New York, and then finally, the Kennedy Center. That’s become a classic. So I learned from that association. I think investigating different cultures strengthens your work and opens you up. There might be 100,000 plays, films, or novels about the Black-white racial divide, but as somebody who looks for a different angle, I talked about another race that’s not covered.

You’re a voracious learner. I’m curious if you recall the first time in your life when you recognized that this was something that you really enjoy doing.

There were times of inactivity, sometimes a few years at a time. I really got going when I moved to New York because there was the old challenge thing. Like, tap dancers challenged each other. There was a lot of competition and there were a lot of resources. I associated with people from whom I could learn about the arts. There was painting, the collage. I was influenced by Carla Blank, who showed me there are different cultures that were available in the art scene, and I began to expand on that.

The artistic elite out here [in Oakland] believes that they should take their cues from New York. They don’t see the whole Western civilization, they just haven’t looked around. For example, Joan Didion is probably a great writer, but a Manhattan critic said she was the voice of the West. I mean, she would be considered a settler—a member of a settler family—by Native Americans and Hispanics, because they’re not really acquainted. It’s like they brought their covered wagons out of here and didn’t exit from the Eurocentric culture. If you can go back to the 1600s, you can find Hispanics writing literature. Matter of fact, one of the first was written by a Spaniard who wrote the history of New Mexico in Spanish. When Norton does an anthology, they exclude this literature. I think they believe that every poem that English writers wrote was great because they print these long poems. There’s so much space devoted to these lengthy poems by British writers, from the 18th or 19th century. They really need an editor or something. A lot of them could be reduced to 100 lines, at least, I don’t know.

That’s the old god. They’re Anglophiles. You get the New York Review of Books—and I’m writing for the New York Review of Books! I never thought that would happen (laughter). But you get Francophiles over there, and you get Anglophiles at the Times. I’ve been in dialogue with Pamela Paul, the Times’ book review editor, and her favorite bookstore is in England. Well we’re American, so that doesn’t apply to us. They don’t really know Spanish or Native American culture out here, and that’s why they call Joan Didion the voice of the West in Manhattan. It’s ridiculous. No matter how excellent a writer she was, I think she’d probably object to this guy calling her the voice of the West.

It’s also a product of this desire to exalt people to an impossible status, of celebrity culture.

Right, that’s part of it. I’ve taught James Baldwin. I can tell people know him by performance. They don’t read his books. They might have read The Fire Next Time (1963). They’ll remember the title, but they haven’t read it. I use his books in classes and they don’t follow his career all the way through. He was done with the New York establishment when he wrote that novel, Tell Me How Long That Train’s Been Gone (1968). He bit the hand that fed him. He jumped on Lee Strasberg and the Actors Studio. They hired Mario Puzo to write the hatchet job in the New York Times Book Review, and then they ostracized him and brought in Eldridge Cleaver, who made homophobic remarks about him, and he was out.

As a matter of fact, the late Al Young published a magazine called Quill, and we had an interview with Truman Capote that was done by Cecil Brown. But Cecil Brown said the New Yorker’s treating Baldwin like shit. I helped him get a job at Bowling Green and how does he repay me? On his deathbed he said I called him a cocksucker every time I saw him. It was a big old fat lie. He had to step over Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Chester Himes, all these other people to get to the top. But that’s ridiculous. Nobody at The Village Voice fact-checked these things. These people jump on you and nobody… (laughter). I think part of this is sort of literary reparations. I think that some of these white women who edit books by Alice Walker and her cult, they’re scared to fact check them. Because they get away with lies. That’s the end of my remark about that, because I know what that remark can bring you. These people are playing for keeps.

Do you still frequently feel like you’re walking on eggshells with the literary community?

The literary community doesn’t have the kind of power they used to. We have institutions out here that we built that are equal to theirs. For example, I founded the Before Columbus Foundation in 1976 and it’s still going strong. We have two MacArthur winners, we’ve got a Pulitzer Prize winner, a Booker Prize winner, we’ve got two former United States Poet Laureates on there. Yet The New York Times doesn’t see us as prestigious, which is what they give that other group, the National Book Award, who are always giving awards to people we gave a decade ago. We expanded the idea of the American literary community. We gave five Native Americans awards in Miami, at the American Book Award Ceremony. Five, instead of you know, Louise Erdrich, she’s got to be embarrassed that they gave one to her. I think she’s the only Native American they know (laughter). I saw a Library of Congress Prize where she got up and saluted Saul Bellow. My god, an awful person.

But anyway, we don’t go on the basis of tokenism. As a matter of fact, the Washington Post said the American Book Awards, which is one of our programs, is the American League to the National Book Awards’ National League. I looked, and they have some Black and Hispanics and others up front, but you look at the people who run that place, and you’ve got Ralph Lauren on the Board of Directors of the National Book Award. I’m saying, “What? Ralph Lauren? I thought he made clothes” (laughter). And you’ve got all kinds of inside traders and hedge fund people backing that thing. I don’t philosophize, I think we probably won the culture wars. It took DeSantis a long time to realize it. We won.

You’ve created your own institutions and no longer have to win the favor of these already established ones. I’m curious, what early experiences did you have of the Black people in your life forming their own communities, of not caring about gaining acceptance from white institutions?

Well, I want to say that I am a member of the establishment. I was just admitted to the American Arts and Sciences Council. But we were independent in New York. We had an independent movement in Umbra Magazine, which is where I learned that you could edit anthologies and publish books. I was part of that, on the periphery of the Black Arts Movement. Their mission was doing away with the white aesthetic, down with Faulkner, and all this kind of stuff. We were independent. We published our own books. I learned from them. I learned from A. J. Smitherman, who had his own newspaper. He was the hero of the Tulsa Uprising in 1921 because he and these guys from World War I would go and interrupt lynchings. So instead of it being a massacre, where whites just ran over all these passive Black people, those are part of this armed uprising against lynching. Essentially, like what’s happening over there in Ukraine, they were just outgunned. I worked for him and I didn’t know he was that person because I didn’t know about his reputation. I left Buffalo because he was in hiding. They still were after him, and he had moved to Buffalo to be close to Canada in case he had to leave the country. He was independent.

I had lots of examples of independent people. I think we’re independent, we don’t get corporate grants, we don’t have any inside traders or hedge fund managers like those institutions. Those institutions where all these millionaires can have dinner with a writer or have receptions on yachts. They have people like George Shultz as a guest. You know the whole thing. We’re beginning to put pressure on them, so they’ve got some of our people to promote them. They gave the National Book Award this year to John Keene. I was the first one to publish him in a student anthology. He got an American Book Award five or six years ago.

How do you feel about being a part of the establishment despite there being so many fraudulent people working on the back end?

Well I like the American Arts and Sciences Council. I’ve been scrutinized, but listen, I don’t see anybody like that there. As a matter of fact, I’m learning from them. They have some women, they have Native Americans. I’m learning from being associated with them. But there are people who are worthy of receiving those awards. Except, in a way, they’re still into tokenism.

I can give you a story. They had a thing where they would give funds to two MacArthur winners to set up a public session. I got another guy, a Chicano, a MacArthur recipient at San Francisco. We were going to do a session, but they said, “No, you have to have these people.” They mentioned two of their tokens, who have been tokenized by the New York Times Book Review. That’s not what the guideline says but they’re telling me, “You have to have these two.” So I was wondering about them. That was kind of weird.

You were involved with Personal Problems (1980) but I did want to ask you something that I learned from talking with another filmmaker, Christopher Harris. He has a film named after Reckless Eyeballing (1986).

I didn’t know that.

He told me that film grammar isn’t representative of Black people’s lived experiences in the sense that, with continuity editing, there’s a certain faith that’s established. For the viewer, everything you see is true. He said that while this may be true for white people, who will feel like they’re always in the right place at the right time, Blackness is about always being in the wrong place at the wrong time. His whole goal with his filmmaking was to think about ways to disrupt these established ideas regarding film so that it more readily captures the phenomenological experience of being Black in America. I say this because I’m curious if you’re interested in capturing a sense of this disruption.

The depiction of Black people by the media—that includes Hollywood and the networks—is one-sided. Black filmmakers and novelists supplement a wider range of the Black experience. We’re framed by others. I don’t know who marketed this idea, but there’s a series now, I guess that was influenced by the Moynihan Report, about the missing Black father. At the time of the report, I think there were probably more Celtic women on welfare—[Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s] tribe—than Black people. But the media’s easy on white crime and white social pathology.

The latest one is [the television series] Let the Right One In (2022), that vampire thing. This is really extreme. Here we go. The Black guy sells some kind of exotic drug. His wife is a detective. The white lead becomes the caretaker of his family and he’s cooking for the Black woman and everything. The only problem is that he’s killed the Black father to get blood for his vampire child. I said, “That’s taking things too far” (laughter). Who writes this stuff? Of course, I had my ups and downs with David Simon, with The Wire, which I thought was terrible. Even the actors complained about it. All the stereotypes. Here’s something that’s probably going to be interesting to say, the Nazi magazine about Jewish males, which I’ve studied, edited by Julius Streicher, Der Stürmer, shows Jewish men as pimps. David Simon always has these things—The Deuce and some other things— where Black guys are pimps. But no Black guy was ever as successful at being a pimp as Epstein. They busted Prince Andrew because he was the poorest one on the list, I guess. But 999 pedophiles. Bill Gates was up there so much that his wife divorced him. Elon Musk was up there, and Clinton.

So anyway, we see David Simon recycling some of these things. He’s not the only one. I challenged Simon—he was on the radio out here with some Black kid who’s touring with. Sort of like Frank Buck, Bring ’Em Back Alive (1930), Buffalo Bill with the Indians, he was touring with his kid to back his thing called The Corner, one of the early pieces he did. I called him and I said, “You’re exploiting this kid. You’re going around the country with this kid.” He went to the Jewish weekly, and said I started yelling at him on the radio. So I went to the Jewish Weekly and they printed my letter. I said, “Why don’t you do something different? Why don’t you do a series about a member of a white family in the suburbs, bringing guns to our neighborhoods?” He didn’t take up the challenge, but I was able to do it. So that’s will power. My latest piece, for Audible, The Man Who Haunted Himself is about a white family in the suburbs, bringing guns into Oakland. We were able to answer back.

One of the goals that we have is to present the other side. You didn’t have to do that when you had a strong Black press. But the Black press crumbled when I was a kid. I used to go around with Smitherman and distribute the Chicago Defender and a number of Black newspapers, but they went out of business when the mainstream press moved their best talent. They were so subversive during World War II that J. Edgar Hoover wanted to charge them with sedition. They always provided an alternative to the kind of stuff we get in the official media, which just spews a lot of propaganda 24 hours a day about Black people. Of course, in the West, they do Hispanic gangs too, so we get a night off (laughter).

I wanted to move into talking about your history with music. I know that you played violin in high school, and you had a teacher, Mr. Bartholomew. Do you mind sharing about your experiences playing violin and trombone in high school?

I really enjoyed it. When I was a kid in grammar school, I was doing very well at the first lesson. I remember the music teacher running out of the auditorium calling for my mother. I studied with him for a while until I became bored. He wanted me to become a member of the Buffalo Symphony. In high school, I organized a string quartet with a music teacher and we did very well. I remember performing “Death and the Maiden” by Schubert at the girls high school, and my E string broke so I improvised on the A string (laughter). Then I played trombone in high school. I had the wrong idea of what improvisation was all about. I had succumbed to the racist idea that you didn’t have to practice, that you just got up there on stage and all of a sudden, inspiration just comes. Nobody had told me about scales and all that stuff. I just had to give up the trombone. The slide trombone kicked my ass, man. That’s why I admire people like Frank Rosolino, J. J. Johnson. That’s a difficult instrument. I’m not talking about Bobby Brookmeyer and the valve trombone.

You mentioned in the liner notes that you were playing with “Brother” Jack McDuff’s band, and that you were just really embarrassed about the whole incident not going well. Do you feel like embarrassment in general is a healthy thing?

Well, I’m getting more clicks on Facebook than he’s getting (laughter). I played Tadd Dameron’s “If You Could See Me Now” on Facebook and I got 7000 hits, something like that. So I’m getting more hits. I don’t see that as revenge. I’m just saying that as a setback. It was Kip Hanrahan who revived my interest. I published a book called Conjure (1972), which had blues and stuff in it, and had brought in all these musicians. But then I traveled with the band and—I’m not trying to slight Kip—but it was obvious to me that the music was more important than the lyrics.

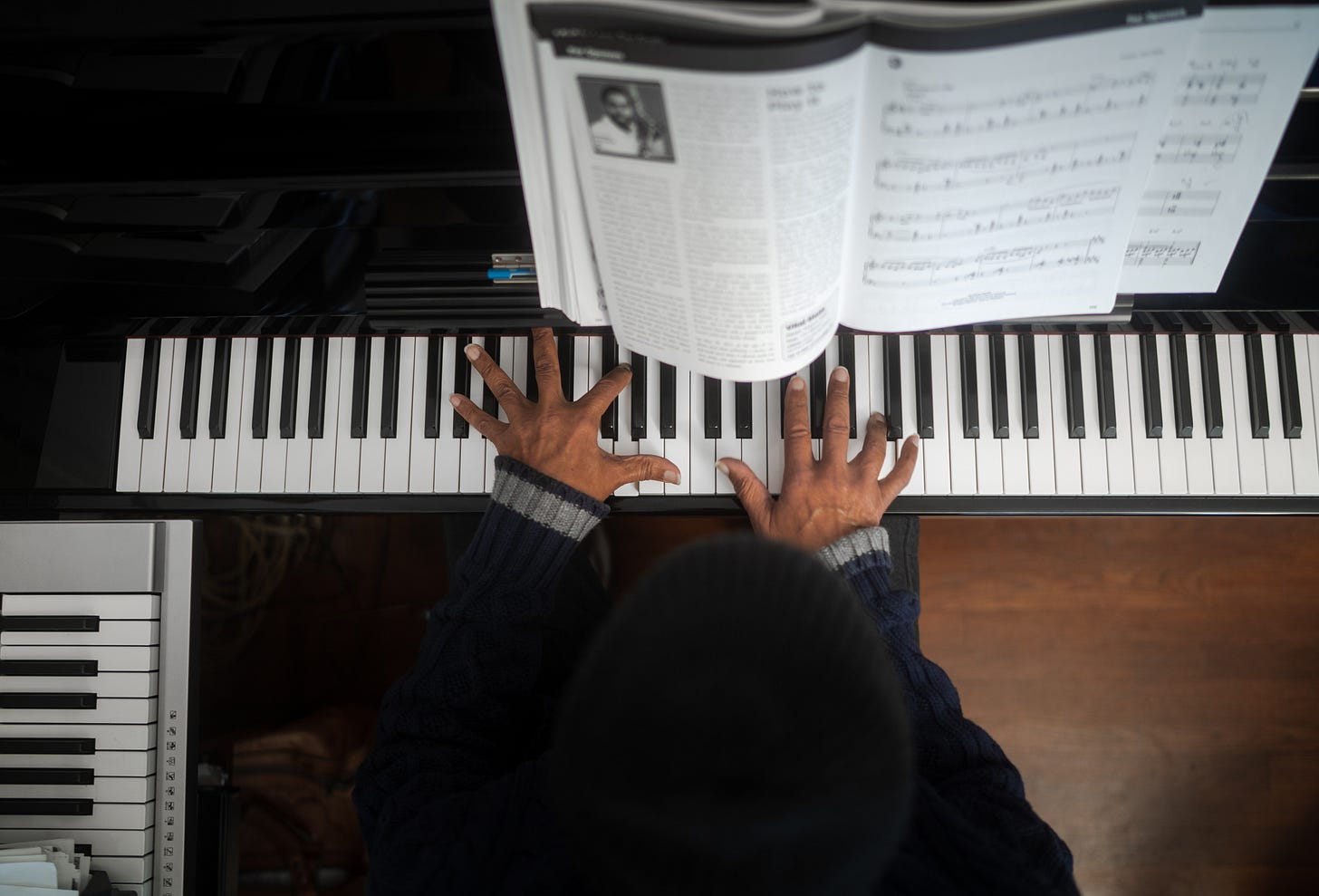

I started studying jazz piano when I was 60, under Susan Muscarella at the jazz school in Berkeley. I was there for a few years, then I studied with Mary Watkins, a great jazz pianist who would come to my house. What I do now is stuff that I’m interested in learning. I pay for the transcripts of people like Stanley Cowell, Lennie Tristano, Bill Evans, Monk, Bud Powell, and some others. I order the sheet music and just look at the way they handle different things like chord inversions and different stuff. I sit down on the piano and I say “Damn, I haven’t heard stuff like this before.” So I started recording this stuff.

We always try to save money because nobody’s gonna put my stuff on Broadway. For example, we did The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda (2019), which was a big hit. They’re stocking that thing all over the world. Miranda must be really tired of us. When they review their play in China, they mention my play. But anyway, we try to save money, so I had my daughter Tennessee, read for the reading. That saved us about $600-700. With the Warhol play—oh my god, the Warhol Foundation threatened to sue us and stuff. Matter of fact, that’s the reason that they’re not doing it in New York again. They were going to do it in New York again, but there was such a protest from some of the people exploiting him, and a hatchet job in the Art Newspaper that goes out all over the world, that they decided not to produce it.

But anyway, we did The Slave Who Loved Caviar (2021) about the exploitation of Basquiat by the downtown art scene. Instead of hiring a composer, I said, “I’m going to put some of this stuff in there.” I had some music in there. I saw that with Carman [Moore], who did the music for Personal Problems. We spent $40,000 on that thing, and New York Magazine rated it recently as the 40th best film about New York. We beat out The French Connection (1971) and all those people. So I said maybe I’ll send my stuff to Derek [Baron]. They said, “Well, you need twenty minutes more.” I got Carla Blank, my spouse, and Roger Glenn. And my daughter Tennessee is on there. These are original tunes.

For the LP Conjure (1984), you mentioned that people see the words as less than the music. That’s interesting because I feel like in most of the world, things aren’t taken seriously unless they’re written down. There’s something more valued in the written word, with less value ascribed to the oral tradition. But that goes to the wayside when there’s music involved. What do you think is the reason for that?

There’s a book about how writers in Tin Pan Alley were influenced by modern poetry, with William Carlos Williams using ordinary language in poetry. I look at Gershwin and some of the other writers. Nobody knows the lyrics of “Love For Sale,” they remember the tune. I’m doing “I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You.” I love the song. I got that on my piano. I never even paid attention to the lyrics. I think lyrics have to be really, like, starters. At least for the standards. I see these hip hop people, everybody in the audience knows those rhymes. But I think that’s different for the standards. Most people think about the music. Matter of fact, you can play the music alone, and nobody knows the lyrics. So I really felt intimidated. I don’t want to mention this person’s name, but one of the singers got a first class flight on coach on the tour where they were doing my music. I said, “Maybe I should be on the other side of the song.” Because that’s where there seems to be all the attention (laughter).

Kip, David Murray, Cassandra Wilson. Macy Gray would never have sung my stuff had it not been for David Murray. Same thing with Kip. Bobby Womack, and all these great singers, Allen Toussaint, all these great composers, that’s because of Kip. Sometimes my stuff gets drowned out in the recordings. I kept telling the drummers to calm down. And oh no, it’s the Cubans, “We love to play drums.” So when I did my first album, For All We Know (2007), I’m not sure if you’ve heard that one.

Yeah, with David Murray.

Yeah, there were no drums.

Right. So that was intentional, because you didn’t want to be drowned out?

That’s right (laughter).

Do you mind sharing any stories about David Murray?

The guy is just a worldly person. We went to Japan, he knows people there. We went to Europe. David Murray’s probably more famous in Europe and Japan than here. I remember an incident where we were on the train in Germany, going to Hamberg or somewhere, and the guy with the train tickets got to the station late and he was running after the train. So we didn’t have tickets. And David Murray got on the phone and started talking in German to the next station (laughter). That’s a while ago.

Dave is a great guy. He’s a genius. I met him a long time ago, in the early ’70s. He’s a friend of Stanley Crouch. When I took my first lesson at the jazz school, I said, “I can be a jazz critic, look at Stanley Crouch” (laughter). And Francis Davis, who used to write for the Voice, was a real white chauvinist. You know, white musicians, most of them—except for Stan Kenton or something like that—don’t have any problems with race. But the critics are really chauvinist. He will suddenly write, “White is the new Black.” In other words, white jazz musicians. Nobody thinks that way. I was on the radio and I said that jazz criticism is a new form of white collar crime. These critics say, “You have to come down here and defend that!” I don’t have to defend anything. It becomes a big racket. All the stuff that goes along with jazz, all the appendages and institutions around jazz. This guy’s teaching John Coltrane and he didn’t recognize the last part of “A Love Supreme” as a folk spiritual. “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” That’s why I put that scale piece in there. A lot of people don’t know the origins of our songs. I think jazz is the most difficult of the artistic disciplines. You get up there and it’s like playing chess, and you only have a fraction of a second to make a move. So I think it’s easier, probably, to write about it than play it.

Did you ever consider being a jazz critic?

I use it in my poetry. I incorporate what I think about jazz, and it’s made my poetry stronger. I wrote a poem about Billy Strayhorn, and I said his real love and light was the D-flat minor scale. I couldn’t have written that without my studies.

What sort of things are you taking from other mediums that show up in the songs you write?

For example, I wrote a poem, “Red Summer, 2015” after Red Summer 1919, with all the police killings. We got a gospel singer to sing that. Then they asked me to write a song for Cassandra Wilson and I went back to the Greek myth. I think that’s probably the first time the Greek myth has been incorporated into the blues. That’s how I work. Or some catastrophe will happen. I wrote “Earthquake Blues” and Little Jimmy Scott sang it in Hamburg.

Working in different media, you never get writer’s block. I’m going back and forth with projects right now. I’m writing a book about William Demby for Penguin. I’ve got a piece coming out in the New York Review of Books about the history of the Black Arts Movement. And I’ve got a piece that’s going to be an anthology edited by Margaret Atwood, about the virus. I just go back and forth between all that. And I’m writing poetry and looking at writing some more music.

But you never seem to get exhausted, from all that you do.

I think some members of the younger generation probably wish that I was in a home for assisted living (laughter). This kid in the San Francisco Chronicle, reviewing my play, kept bringing up my age. I’m 84, he kept bringing it up. I never see that happening with younger people. They never say, “Oh, this person’s 35.” But it seems, in this society, they’d like for you to go away, in contrast to other societies like in Yoruba culture. I was in Ghana at a conference and the grand old man of Nigerian letters got up and put down one of my books. I got up and challenged him. He came toward me and said, “We’re gonna talk about the culture of our elders in Africa.” We became friends. I published one of his short stories. Then there was the young woman, Toyin Adewale, who Carla Blank edited in this anthology, 25 New Nigerian Poets (2000), and Short Stories by 16 Nigerian Women (2003). I told her she should call me Ishmael. She told me, “We don’t call our elders by their first names.” It’s interesting.

Elderly people are treated differently in different societies. But over here, the idea is to get rid of them, which I think probably accounts for disorder in American society, because the old people know the stories. They carry the stories. We gave an award to Nora Marks Dauenhauer, who’s a Native American from Alaska. She’s gotten three awards from us because we have Native Americans on our Board of Directors. She’s revered in Tlingit society in Alaska because she knows the stories handed down for generations. People in my generation know the stories. There’s no continuity without handing them down.

Yeah, so much of society focuses on younger artists. When you read interviews with them, it’s funny because… how could these people possibly have anything to say when they haven’t even lived their life yet?

You know, I like Wynton Marsalis. I think he’s done a good job. But I remember when Wynton Marsalis received an award, Miles Davis and Dizzy were sitting in the audience (laughter). Dizzy and Miles—those were the elder statesmen who invented the kind of jazz that he performs at the Lincoln Center!

Earlier, you mentioned how you studied these different pianists. Were there any in particular that you felt like were so challenging or so far removed from how you approached playing that, as a result, you had to create your own style?

Well, I looked at a variety of styles. I mixed them up on that CD. I’m still studying three or four artists that I look at every day.

Who are you studying right now?

I’ll look at Monk every day, Bud Powell, and Bill Evans. What a genius. His improvisations, the way he organizes melodies, and the sort of chord choices he makes, as far as I’m concerned, he’s a genius.

The big thing about Bill Evans for me is he’s able to make his playing sound like you know him as a friend. I don’t know how he’s able to accomplish that.

We’re talking about a virtuoso. Kenny Dorham is another one who comes up with interesting harmonies. Some of the great pianists actually are so great with the melody that when they get down to improvisation, it’s sort of predictable and trite.

You mentioned when you were a child that you had this misguided notion about what improvisation entails. How has your relationship with improvisation evolved across the decades?

I know my limitations. I didn’t play Bach for thousands of hours like Bud Powell or some of the others who started out early. Randy Weston makes a piano sound like an orchestra. I knew him up to his death. I think I play improvisation from the heart, from what I can hear. I try to invent my own ideas, invent my own standards, just by breaking up chords. For example, The Hands of Grace (2022), I think that’s a different sound. I don’t know whether it’s unique, but I hadn’t heard that sound before.

It’s really arresting. It feels very comforting in its simplicity, but it’s not simple in the way most people approach simplicity. On the title track you have this clicking and thumping…

Right. And with “Elegy for Lucille Clifton,” the kind of reaction I get for that is “hauntingly beautiful.” That’s my composition. I just wanted to encapsulate her suffering and her beauty. I talked to Grace Wales Bonner, a fashion designer. That was a big boost for my playing, when she invited me to England and I played at her fashion show. The funny thing is that Carla Blank recorded a song I wrote called “The Wardrobe Master of Paradise.” What I had in mind was fashion designing for the avenging angels in the Book of Revelations. I was never in Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar, but now, for the last three years because of her fashion show I’ve been in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Gentlemen’s Quarterly, Town and Country (laughter). Really, God is a trickster.

Not everything on the album was initially intended for The Slave Who Loved Caviar. You made new songs. I am very interested in the people mentioned. There’s Basquiat, Lucille Clifton, Steve Cannon, and then there’s also a song for Carla. How do you approach writing a song with these people in mind?

Lucille Clifton was a housewife in Buffalo until I introduced her poems to Langston Hughes. Now she’s dead, but she became very famous. She won the National Book Award, she was Poet Laureate of Maryland. Now her house is a national landmark. I’m in touch with her daughter, Sydney. That song just came from what I knew about Lucille. She had a big heart. She was really just a great, beautiful person. It was a tribute.

I wrote the song for Carla for the anniversary. I don’t know if she liked it (laughter). But that was heartfelt. Carla’s a very beautiful person and a genius. She’s been multiple things—choreographer, director. She likes challenges. She went to Ramallah and directed a play. The cast was composed of Palestinians and Syrians, speaking in Arabic. She collaborated with Robert Wilson and a number of well known people. She surprised me by being honored by the Los Angeles Press Club for an essay she wrote about Aimee Semple McPherson, the evangelist. I don’t know whether you know her history. She brought show business techniques to evangelism. It was like a star in Los Angeles. She created a lot of stunts. She still has followers even though she’s dead. She fed a million people during the Depression. And she’s still like a movie star. She died here in Oakland. She came here for a crusade, and died in a hotel downtown. She was a fabulous person.

The reason that Carla wrote that was because there were two TV series last year that were based on Amy Semple McPherson. She interviewed some of the actors. So it was nominated for a prize by the Los Angeles Press Club. Now here’s somebody who’s a director, a choreographer, a dramaturg. She does all these things. She wrote a book called Storming the Old Boys’ Citadel (2014) about two women architects at the turn of the century. So she’s done a lot of different things. I think we both have been into a lot of different things.

Steve Cannon was my partner for many years. He was one of the first people I met in New York. He developed a whole cult called A Gathering of the Tribes. They had a gallery and published a magazine. He was very well known. They called him the “Emperor of the Lower East Side” in the New York Times. We used to sit around his apartment. They did a biennial at the Whitney, and they had a duplication of his apartment—his living room—in the exhibit (laughter). I thought, “There’s that old funky couch we used to sit on.” And they were passing it for fancy (laughter). I wrote that song for him, “Steve Cannon Blues.”

What does it mean to you for someone to be a genius?

I think of Da Vinci, a renaissance person who was able to succeed in many different fields, not just one. It’s not one-dimensional. I do cartoons too. I illustrated one of my novels, and the publisher said my cartoons weren’t good enough. So I went to cartoon school at 70. My cartoons are published in the Chronicle. That’s what’s happening more and more. People don’t want to go to work anymore. I don’t know if you’ve noticed that. People aren’t really looking for jobs anymore. They have more time. If you look at some of the stuff I see on Facebook by ordinary people, dancing and all that, talent is really common. I think people will be able to fulfill their creativity. My idea is that people aren’t going to work anymore because there’s too many seasons of Downton Abbey (laughter). The suit that you wear to church every Sunday? You can wear it every day.

Don’t you feel like people aren’t going to work now because they also feel very exhausted by the pandemic, the exhaustive nature of working under capitalism, all these other things?

Yeah, I think that’s happening. I used to work these 9-to-5 jobs, spending all my time looking at the clock. I wanted to go home. Millions of people live out their lives that way. One thing that social media has done, Instagram and all that stuff, is that they show people there’s talent. People organize these dance steps in public and office buildings and places. I think that’s going to revolutionize the way we look at art. It’s not just the elite, talent is widespread.

Do you consider yourself a genius?

No.

Why?

When they gave me the MacArthur Genius Grant, all my relatives and people I know started calling themselves geniuses. So I guess I set the bar pretty low (laughter). I don’t think I’m a genius because I’ve met geniuses. Malcolm X is a genius. He’d read more books than I’ve read, when I met him.

Do you have any memories of Malcolm X that you mind sharing?

I think that he was basically a scholar, and he got mixed up with politics. He went to a prison where some philanthropist donated thousands of books and I think he probably read all of them. I’m dealing with prisoners right now. I’ve dealt with prisoners. What’s not mentioned in this discussion of education is that it seems that Black and brown kids have to go to prison to learn how to read and write (laughs).

Because they don’t get it in the school system?

People don’t teach them. I have a book right now by Celes Tisdale who taught at Attica. He was a Black male teacher, and he got good responses from the prisoners. He published their poetry. I went to Attica myself, I’ve gone to prisons. I wrote a book called The Last Days of Louisiana Red (1974) which went from the printer to the remainder shelves within a few weeks (laughter). It got a prestigious prize. I went to Ramsey State Penitentiary in Texas and all the prisoners were reading them. That’s a real comment on public education that Black and brown boys have to go to jail to learn how to read and write. When they do the test scores, they don’t mention that the girls do well. There are more Black women and white women in universities than males.

I’m actually a high school science teacher. Hearing the discussions from white people in my school who want to be well-meaning in addressing race, and then seeing the reality of how it plays out when I’m in their classes, how they treat these Black and brown students, all the racism they don’t even recognize that they’re doling out… it can be alarming.

My new play is about the school board recall in San Francisco. These right wing billionaires got involved in it. They were behind the scenes, dark money. What they want to do is to eliminate the public schools. They’re following the bell curve. They feel that you can’t educate Black and brown boys and so they should be relegated to the service industries, and that trying to educate them is a waste of time. That’s why they’re trying to do these charter schools. It made the front page of the Chronicle because they felt that I was being unfair to the voters who were responsible for the recall. But those people were used. Chinese immigrants were used. They were put up as a prop, dividing us. My opinion was that the curriculum was Anglocentric, and that it not only cheats Blacks and Latinos out of their histories and traditions, but I talked to Pat Goggins of the Irish Cultural Center, and the Irish kids don’t know about the Great Famine. I talked to another Italian American writer, and she said that Italian kids don’t know their histories, because it’s Anglocentric. It conforms with Roger Stone’s idea that privileged white men saved Western civilization. I asked Europeans about Western civilization, and they say “Americans want to treat us as a monolith.” It’s anti-ethnic. It promotes one group over the others—not only Blacks, but white ethnics. That’s why some of the biggest racial brawls and disturbances take place at the centers of learning, universities and hospitals.

One thing I’ve gotten from you in this conversation is that it seems like you enjoy receiving attention. Is that fair to say?

I would be in New York if that were the case. Why would I come to Oakland? (laughter). People say that. I don’t know. I just see things are all screwed up in public dialogue and I challenge them. That’s what this stuff is. I see artists as the unofficial journalists, because the media will leave out a lot and they’re wrong about a lot of stuff. They said that Latinos were drifting towards the Republican Party. Bullshit. Just like they said that Latinos wouldn’t vote for Obama. They voted for him in Illinois and for president. I became so interested in TV that some of my essays on TV are published in scholarly publications about the media. I just see myself as countering a lot of propaganda, because propaganda is harmful.

I didn’t even mean it in terms of your confrontational views, but just more generally speaking.

They said that when I did The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda. I got a lot of angry letters after this woman did a review of the play in the New York Times. I got a lot of angry responses from BroadwayWorld, people read that. It brought attention to myself. But then it turns out that Hamilton did own slaves. The historical site or whatever museum admitted that he owned slaves. We knew that because he left receipts. My god, his grandson said he owned slaves. But they’re still going on with that thing, they’re still pushing that million dollar fraud. I don’t know which one is most cringe-worthy: Donald Trump kissing Michelle Obama on the cheek on Inaugural Day, or Lin-Manuel Miranda posing with a bunch of Black kids (laughter).

Oh god, both of those are bad. I did want to ask about your daughter, Tennessee. She appears on “How High the Moon” where she’s interpolating Frank Sinatra. What do you feel like you’ve learned from your daughter that you wouldn’t have been able to learn on your own?

She pays closer attention to the world than I, in terms of nature. We grew up in the asphalt jungle. But she’s more in tune to what’s happening with the earth and with nature, and she can write about this in detail. For example, she just came back from a writers retreat in the mountains. She wrote about that and just made observations that I would never make about the land and about what was happening around her. She’s got that knack.

How about you and Carla, is there anything about who she is that has made you a better person?

She’s got depth. That’s very rare for an American (laughter). She’s a profound personality.

Has anything happened recently that reminded you of that?

I’m just reminded every day. We work together as a team—she influences me, I influence her. I really tried to persuade her to be on this record, and I kept pestering her until finally she relented to play. I’m glad she is on there. She studied with a Russian violinist. She’s on the first album too. We played her piece on, what was that tune? (Ishmael Reed asks Carla Blank to tell him the name of the song). “When Sunny Gets Blue.” We stood around, all the musicians, and they really loved her performance. She and Robert Wilson collaborated on something called KOOL (2009) that broadcast on PBS and French television. She’s done singular works. She did The Wall Street Journal, which was the first anti-Vietnam protest by an artist in 1965 or 1966, at Judson Church. She’s part of the Judson post-modernist movement.

Was there anything that we didn’t talk about today, that you wanted to talk about?

I wish that people would fact check stuff when they say stuff about me. I know that’s paranoid. But it just seems to be racist (laughter). Because I get fact-checked to death. When I write for these magazines, man, oh god. The New York Times says, “He’s a wild man, you better check him, son.” I get fact-checked to death. I can’t see why some of these other people don’t fact check.

But anyways, I think that John A. Williams said that I was resented because I was so far ahead of everybody. I’m not. Henry Louis Gates Jr. recognized that when he wrote that piece about the signifying monkey. I’m not doing anything new. I’m just coming out of traditions like Yoruba, that people aren’t acquainted with. Critics are not acquainted with it.

There’s a question that I always end all my interviews with, do you mind sharing one thing that you love about yourself?

Persistence.

Why do you love that about yourself?

I think that’s the reason for being alive: to work on a problem until you solve it. I do that in everyday life. I’m very patient. People will give up, but I work until I solve the thing.

Ishmael Reed’s The Hands of Grace is out now on Reading Group.

Thank you for reading the 102nd issue of Tone Glow. Solve the thing.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Wow, great interview, I need to read some Reed!

Wonderful interview with such an important and influential artist. Thank you!