Tone Glow 101: A.R. Kane

An interview with Rudy Tambala of the pioneering dream pop band A.R. Kane about growing up in the East End of London, creating songs from lucid dreams, white supremacy, science fiction, and more

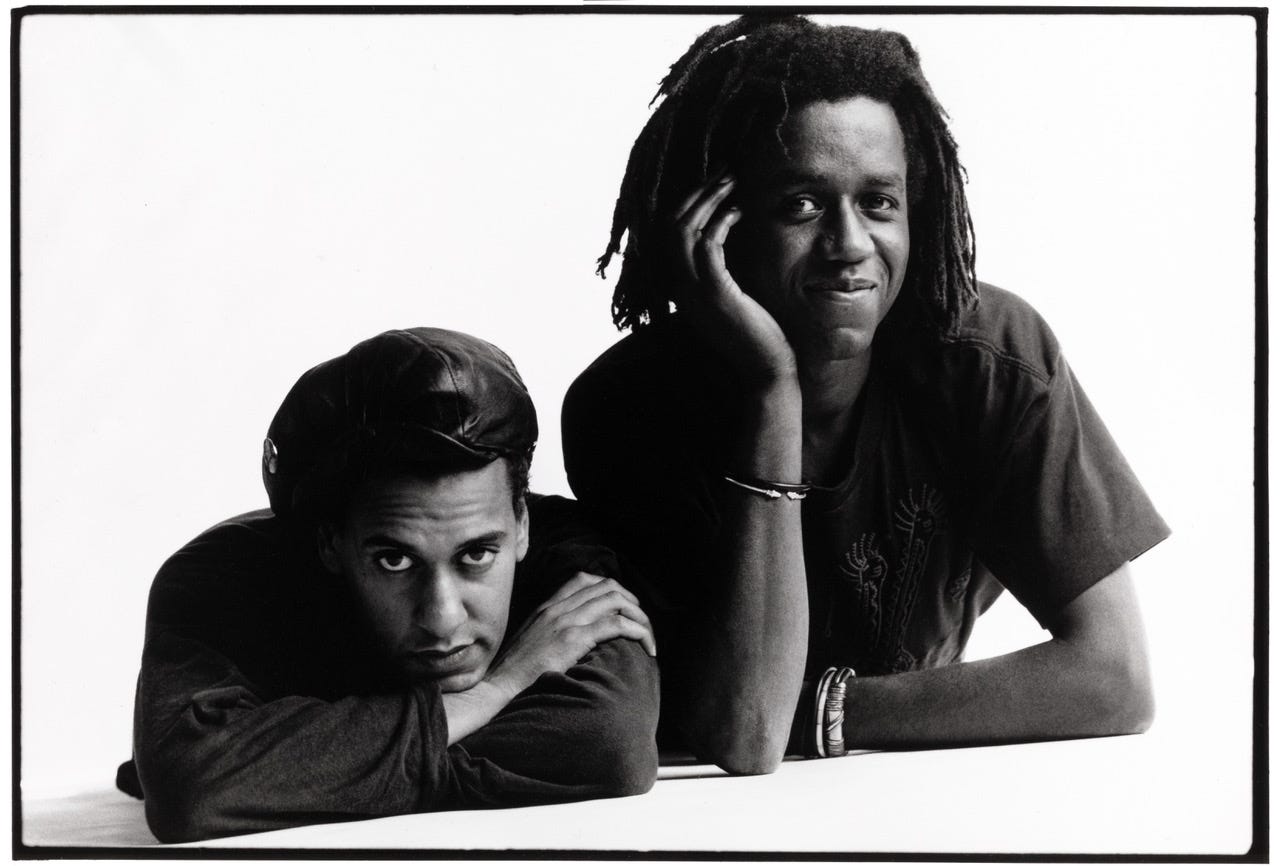

A.R. Kane

A.R. Kane was a British band formed by childhood friends Alex Ayuli and Rudy Tambala. Growing up in the East End of London, the two spent their childhood devouring music—jazz and disco, soul and funk, dub reggae and ska—through family members, local parties, and imported records. The two would form A.R. Kane and release their first 12-inch, When You’re Sad, on One Little Indian in 1986. Soon, they would make their way to 4AD where they collaborated with Colourbox on the 1987 chart-topping single “Pump Up the Volume.” Eventually, the group would land on Rough Trade and release the best music of their career, including the Up Home EP (1988), 69 (1988), and “i” (1989). These three releases are compiled on A.R. Kive, a new remastered box set released by Rocket Girl.

Having coined the phrase “dream pop” to describe their work, A.R. Kane would pull from actual lucid dreams to construct some of the songs they wrote, humming melodies to one another any transforming them into ethereal songs. Their music, more adventurous and visceral than any contemporary band given the same label, has been influential to numerous artists across varying genres. Even so, A.R. Kane remain one of the most undersung bands of their generation, effortlessly sitting alongside the best shoegaze acts of the time while incorporating dub elements, dance music, and post-punk. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Tambala on September 12th, 2023 via Zoom to discuss his upbringing, his older brothers’ influence on his vast interests, the telepathy-like relationship he has with Alex Ayuli, the paint-by-numbers nature of dream pop bands today, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Something that I really enjoy about the early A.R. Kane releases, with songs like “When You’re Sad” and “Butterfly Collector,” is how there’s a desire to capture beauty amidst noise and brashness. I’m curious if you can recall the earliest time when you realized that this was possible.

Rudy Tambala: I wouldn’t have used the word beauty, but I understand what you’re saying. For me it was a dangerous excitement, this joyfulness and glee in that noise aesthetic. I remember being at Alex [Ayuli]’s and he had just got a new amplifier and speaker box, like a Marshall stack. We plugged the 12-string into it, which you’re not really supposed to do, and we bought a little ceramic pick-up to put on it. And we still have it here (grabs guitar and shows it to the camera). This little boy. It’s still got the ceramic pick-up, and we plugged it into the amplifier and obviously there’s a huge wave of feedback that’s completely uncontrollable and of several different frequencies—there’d be wood vibrating and high-pitched squeals and all that. And you’d play a chord through that and you wouldn’t know what would happen to it. You’d get so much refraction and feedback. I remember thinking, wow, this noise thing is really great.

How old were you when this happened?

I think 20? We weren’t teenagers. That was a moment I remember quite clearly, of thinking, wow, this is powerful. I guess you could call it beautiful but I wasn’t quite thinking of it in those terms.

Why do you think you wouldn’t have used that word?

It wasn’t in my lexicon (laughter). It wasn’t a term I used, really. When I think about other music I like, which has that discordant and chaotic element—this overload—I can see that there is a certain beauty in it, like if I listen to Sun Ra. A couple years ago I was doing some gardening and I put on some headphones and I had Sun Ra playing, immersing myself in that. What happens is that after a couple hours, if you try listening to anything else, it seems so facile and pointless and fake, just so artificial, so constrained. Whereas with Sun Ra’s music, there’s a freedom. And that’s where the beauty is. It’s like looking at an impressionistic painting. Like, I love the way that [Georges] Seurat did those points of light and had that lovely feeling of a summer’s day by the river, and then you look at Lavender Mist by Jackson Pollock and you get a whole new order of beauty and symmetry, which is so far beyond. Not that one precludes the beauty of the other, but it’s a different type of experience, isn’t it?

Do you feel like freedom is an important facet of art, for it to really speak to you?

It’s interesting because you can use the artificial as a tool as well. If you listen to our music, we could jump from “Sulliday,” which is very free, and then to something like “Crazy Blue,” which is quite structured like a pop song. You can play around with any form. I guess the thing we were doing is what I said: One doesn’t preclude the other, they all have their place. It’s not a question of judgment; it’s not a moral judgment, it’s an aesthetic sensibility, like, oh that’s where this fits, that’s how these things can interact.

Before we get more into the music—

We’ve gone straight into the deep end, haven’t we? (laughter). Fuck the small talk! (laughter).

I wanted to ask about your upbringing. I know that your dad was from Malawi and your mother was English. Was there a lot of Malawian music growing up? Were you listening to kwela?

None. My dad didn’t really have a musical ear. He didn’t bring a lot of his culture with him. He embodied his culture, but he wasn’t teaching us Swahili on a daily basis, or Chichewa. There were little bits and pieces, usually when he was angry and swearing at us (laughter). He was the embodiment of a certain type of Africanness.

Did you have siblings?

Yes, I had three older brothers and a younger sister.

Can you paint a picture for me of what it was like to grow up in your household?

It was fucking crazy. There’s seven of us in all with my mum and my dad. A real culture clash in the East End of London. There weren’t a lot of immigrant families. The ones that were there were poor Irish, poor Cockney, and there was the Windrush. That was a ship that sailed from the West Indies to Britain, which really was to bring nurses into the NHS because they were understaffed. And people were brought over to run buses and trains—menial tasks. A lot of Jamaicans, Dominicans, Bajans, and so on—that was the Black community. We were part of the Black community, but we were different because my dad was not from the Windrush, he was from Africa, which was quite rare at the time. My mum being European—we were mixed race—made us even extra rare because that just wasn’t happening so much those days. Obviously it’s much more common now.

So, we were quirks in a quirky environment (laughter). But it was great. We were all talented in our own ways and were quite respected in the community and neighborhood. It was a solid neighborhood we grew up in—good community feeling—but it had its trials and tribulations as all neighborhoods do. There were racist elements but they were few and far between. And there was the whole thing of growing up at the bottom of the ladder, the bottom of the working classes. My dad, being African—and a lot of Africans and Asians who traveled—were very aspirational for their families. This is quite different from the West Indians who traveled. I think that’s from 400 years of slavery, and that’s gonna have an effect on a culture. I think the next generation and the generation after that would become more aspirational. The first generation weren’t as much, whereas my dad would be like, (imitating his father’s voice) “You must study Rudy!” Studying was the gateway to everything, and if you didn’t study you got beaten.

You mentioned that you had a good community, do any memories stand out that exemplify that?

We’ve just come to the end of the summer holidays here, and I’m living in Cambridge where there are these lovely terraced houses on the street. But you never see anybody, really. People leave their houses, they come back, and close the door. When we grew up, everyone was on their front doorstep, mums were chatting, and if it was lunchtime during the summer holidays, you just went in any house to have lunch. It was like a village, and like a village, the elders took care of the youngest and everyone else worked, that kind of thing. People were open, and no one had much, so no one was stealing from each other. It was quite happy.

Weeks were quite intense because there was school and home and dinner and study, but weekends were crazy (laughter). We had friends over, we always had music playing. I remember seeing Boyz n the Hood (1991) and there’s one scene where the kids are running around the streets and Dr. Buzzard & The Savannah Band’s “Sunshower” playing in the background—that was our life. We had all this soul music imported from America, all this disco, jazz, jazz-funk. My mom would be playing pop music, reggae, ska, classical. Our life was very musical. Everyone in my family, apart from my dad, absolutely loved music, though my dad would sing when he was happy (laughter). He would sing songs from movies he’d seen. My mom loved classical music and pop music, and she loved to party.

My oldest brother Kelvin was the first one to go into a musical movement before ska and reggae. This was in the 1960s. And later on as we grew, the American soul scene hit London, so people were into soul—not Motown, but like Philly sound. And then there was jazz-funk and jazz and disco. It was always this current of Black American culture in our family. We listened to Richard Pryor for the comedy, we listened to Stevie Wonder for the soul.

This is really interesting. You mentioned that your family was the quirk in this quirky community. With all this art being imported, of being immersed in Black American culture, did you often think about your identity and how it differed from the people around you?

All kids are the same, they just get on, even though the parents may not. When you get to about 12, you start to notice the differences. And I think what a lot of immigrant families notice is that they’re not accepted, and so you look for an identity. A lot of West Indian kids would have looked to Jamaican or West Indian roots, and would have gotten into reggae. Though we were exposed to the reggae scene, what we identified with was Black American culture. And that was through my oldest brother, he’d buy Ebony magazine, Blues & Soul magazine, and come back with American-import soul records that we religiously listened to.

I think I was 14 before I realized that Bruce Lee was not actually Black (laughter). I thought he was one of us. He would go out and beat up all the bad guys! And then you got Richard Pryor making fun out of the word “n*gger,” and then you’ve got all of the soul music and the soul scene. You’d go out clubbing and it’d be multiracial and cool. You find your tribes, don’t you? You find an identity of your own. By the time we were 14 or 15, we knew that East London, white, working-class culture was not our culture. It rejected us, it didn’t treat us on the same level. There was this inherent racism—it’s this island mentality, and Britain very much has that. It’s white supremacy… what more can I say? It’s been around for a long time.

The thing that stands out to me about your music is that there is this willingness to pull from so many different styles. There’s a boldness to not care about the genre rules that may have implicitly, ostensibly established. I like that you’re putting all these different things together.

I don’t know why everyone isn’t doing that, it seems like the most obvious thing (laughter). It’s called fusion. And like I’ve been describing, my and Alex’s influences—and my family’s influences—were from different cultures. And we were absorbing it all. Not everybody does… I think the West Indian community, which was probably the closest to ours, could be very conservative, usually quite Christian. Simon Reynolds, you know him, he had this concept of the “upper working class” and I think he put us into that category. A lot of the creativity in music in particular, this aspiration, comes from people with this gritty background. The Beatles, for instance, and David Bowie. Not that I’m putting myself on that level, but I get where Reynolds is coming from. Cocteau Twins and the Jesus and Mary Chain, they come from very raw, working class backgrounds but they’re quite cerebral and smart. That is one area I will put us—we’re quite smart, we were clever motherfuckers (laughter).

There is a word, I can never remember what it is, where there’s a random set of events but then there’s a nonrandom selection of those events. Like Darwinism, in a sense. There are mutations everywhere but the mutations that survive are right for the time. With us, if you take “Baby Milk Snatcher,” which is one of our most famous songs… we did a gig last Monday and before we were rehearsing it, I was watching a movie and there was a song by the Beat called “Mirror in the Bathroom.” I just started playing and thought, “it’s the same chords,” and we just mashed it up. (starts singing “Mirror in the Bathroom” and then “Baby Milk Snatcher”). I was talking with my sister Maggie, who has been in A.R. Kane since 1986, and as soon as I started singing—and she knew the lyrics as well because we grew up listening to 2-tone music—she started singing it naturally too. I like that thing of bringing in the influences and being like, “oh that works,” and not just that, but “that sounds really good.” We had a whole range of influences, and I usually say that the one we didn’t pick from was country and western (laughs) and it’s true! We didn’t have any country music in our background, but we had everything else.

You were talking about being part of this aspirational working class. I know that you and Alex worked at the advertising company Saatchi & Saatchi. Can you talk about how you managed to do this while also making music?

Alex had a full-time job. We both went to college—he went to an art college to do advertising and marketing, and I went to university to do biochemistry. He got into the advertising world because he’s really good with words. He became a copywriter immediately; he didn’t even finish his courses, he just went straight into one of the ad agencies. I went on and graduated and went into research for a year, which I hated. I was out of university at the age of 21 and I was looking for what I wanted to do next. I was a bit of a polymath, so I was doing computer programming and photography, I was trying to write books, I was doing music. I was doing anything that interested me and I wanted to see what would stick first. It was when Alex and I started doing music that, very quickly, music became the first thing that stuck. It could’ve gone in any direction.

I was carrying a lot of what we were doing. I was dealing with the record label and sorting our rehearsals. He’d come home from work or on the weekends he’d turn up and do his parts. That’s what enabled us. I think if we both had been full time, we wouldn’t have been able to do it. I also think if Alex hadn’t had a full-time job, he wouldn’t have been able to dedicate himself to the music as well. That supported him in it.

Yeah, it can be important to have that peace of mind through a reliable source of income. It’s also just nice having structure in your life.

I have a full-time job, I’m a consultant, and I should be working right now but fuck it, eh? (laughter). And when I am out of contract, I don’t do much music, but when I’m in contract, I do much more.

That’s always how it works! I’m a high school science teacher—I teach biology and chemistry.

Oh wow! That’s really cool. So you know the Krebs cycle (laughter).

It’s funny because when I’m working during the school year, I’m able to do all this other stuff I want to do, but during the summer it’s hard for me to do anything, really.

Yeah. I landed a contract at the beginning of the year and in that time, we’ve done live work, I’ve done loads of new recordings, and we’ve done this box set—and that’s our legacy! I’ve done all this while working on a really hard job. Are you in California?

No, I’m in Chicago.

The company I work with is based in California, so I get up and start working, and then about 3 or 4 in the afternoon they all wake up and I start working with them. But the weekends are mine.

I know there’s a story of you and Alex having watched Cocteau Twins on TV. Do you mind talking about what that experience was like? What do you remember about that?

I already knew their music—I had known it for about a year. I had known This Mortal Coil and 4AD because of the artwork and the whole vibe, this whole magical and esoteric label. I knew Dead Can Dance. But it was “Song to the Siren” that I really knew. I had never seen them, though. And I had never seen anything like it. It must’ve been “Pink Orange Red,” these beautiful colors on the screen, this hypnotic music, and just the static appearance of them. And it wasn’t them leafing around.

The ’80s were a brash time. [Marshall] McLuhan said that you’re either some combination of hot or cold and lo-fi or hi-fi. Everything was hot and hi-fi, but Cocteau Twins were cool and hi-fi. They were very withdrawn, and it drew you right in. I spoke about this impression before, the way they looked, the fact there was no drummer there. It was a piece of technology—it was a reel-to-reel—and I just thought that was genius. We didn’t have a reel-to-reel, so when we started playing live, we used cassette for the drums, and then we went to reel-to-reel later, and then we got drum machines. I think it hit on many different levels. Very cerebral, the aesthetic, the emotional intensity of the music, the beauty of it. It was one of those moments.

When the When You’re Sad EP came out in 1986, I know that there was press calling you the “Black Jesus & Mary Chain” shortly after.

That was one review, and as much as everyone said it was lazy journalism—we probably said that at the time—one of the things was that we didn’t want to be categorized, and we were being told we were a Black version of something else. There’s an absolute parallel between “When You’re Sad” and “Some Candy Talking.” It’s got the same chord progression, it’s got a lot of similarities. Whether that’s a coincidence, I will never tell (laughter).

So it’s like, I know that in my environment, in England—especially where I live now, in Cambridge—if I walk into a pub, and someone asks, “Can you describe the guy who walked in?” someone would say, “He’s a Black guy.” And that’s the first thing. And that’s got associations, it puts you in a certain class, there are certain perceptions and prejudices—not all bad, but mostly. So to hear this, it’s like… here we go again. We’ve broken the mold completely—we’ve got guitars, leather jackets, dreadlocks, and we don’t look like anybody else and we don’t sound like anybody else, and we’re being put into a category. So it was annoying for us, and we refused to talk about race, really, because that was so cliché in the ’80s. We didn’t want to be put into any category; we wanted the music to speak for itself. And we were genuine about that. As people tried to pin us down, we went in another direction. Not that we were totally reactionary, but naturally we kept on shifting. We were shapeshifters.

Yeah I know what you mean. It’s upsetting when you’re in a white-dominated space, people see you and immediately pigeonhole you. I see this in my own life, where I sort of want to surprise others, though I mainly want to surprise myself.

Yeah, there's freedom in that and that’s something that Alex and I achieved. I started school at the age of 11, and the intake of the first year was 200 children, I think. At the age of 18, when I went to university, only 2 of us went. And that’s just 1% of the population of that school year. It’s a really low percentage, and I carved something out. The other guy was really smart, I was just good at exams (laughter). Alex, the same thing. He was the only Black copywriter in advertising, and he was a kid as well. I was graduating as a biochemist, Alex is a successful copywriter at the age of 23 and making like £80,000 a year and driving a Lotus. We got dreadlocks, and no one had that back in the day aside from Rastas. And we dressed like punks.

So we were carving out this completely new space for ourselves, creating our own culture, and that’s one of the key things. It’s not just music, it’s culture—it changes the world around you. I wouldn’t have said that boastfully at the time, but just in doing this archive box set and really recounting things, we were a cultural phenomenon. We opened people’s minds to a different way of looking at the world, and that’s what you want to do. We showed people our point of view and that things could be different. I think other creative types latched onto that, and that it helped them.

Have Black people come up to you or Alex specifically to talk about how much you impacted them?

Yeah, it happens frequently. We had this young band come and play, they were our support band. They’re from London. They’re all Black guys and one Asian girl on the bass. They got dreadlocks and leather jackets and it was like, they’re like a baby version of what we looked like. And in East London, at the time, there were these other bands popping up with dreadlocks and leather jackets and loud guitars, and I think that’s really quite interesting. Just recently, Simon Scott—the drummer from Slowdive—he just did a list of 10 favorite albums and he mentioned us. He lives close to me so we’ve been out for coffee a few times, and he’s mentioned how much A.R. Kane influenced Slowdive and was a massive influence on their sound, especially “Souvlaki Space Station.” So we were influential. We didn’t sell huge numbers like My Bloody Valentine, but people who listened to us wanted to make music as well. We influenced bands, mostly.

You’re saying all this and I’m thinking about all the bullshit you guys had to deal with as a band. I’m thinking about everything that came up with going from One Little Indian to 4AD. There was that whole kerfuffle.

That hasn’t even ended, trust me. One Little Indian are still claiming that they own all of our material from day one, even though we only made one record with them. There were two things that were told about us: 1) we were really impatient, and 2) that we were difficult. We knew what someone meant when they said we were difficult. That meant we were uppity n*ggers. That’s what it meant, that’s what it always meant. Ivo told me, “You need to be grateful.” When we had the number one record with “Pump Up the Volume,” we instigated. He told us we should give all of our royalties to Colourbox because they’d been around longer than us. And I told him, “I don’t think that’s very fair.” And he said, “This is the way it’s gonna be. You take what I offer you and you need to be grateful for it, or you don’t get anything.” And I said “fuck off,” put the phone down, and got a lawyer. I know when people are treating you like that, where it comes from. It’s that [white] supremacy thing again, and no one was gonna “put us in our place.”

I’m glad you guys were firm on that.

And we ended up on Rough Trade eventually.

Right.

And that was home. They nurtured us, and they gave us a lot of leeway. If your bull is difficult to manage, give it a larger field so it can run wild. And they gave us a larger field.

I know that you had a kinship with [producer and Cocteau Twins member] Robin Guthrie, and would make fun of the preciousness of 4AD.

I think that was with Robin and Liz [Fraser], not so much Simon [Raymonde]—he was an Englishman while Robin and Liz are Scots, and the Scottish have been oppressed by the English forever, so there’s not a good relationship between the English and the Scottish on the whole. They were very working class like us. I think they were very charmed by 4AD in the beginning, and that a label was even interested in them in the first place. They very quickly saw through it, and loaned us their cynicism. They told us what was going on and we saw it quickly as well. We were streetwise enough to be able to see through that shit, but I think they had to learn the hard way—they were manipulated, in a way. And they were the success of 4AD. 4AD the label is amazing, don’t get me wrong, but you take Cocteau Twins out of the picture and the whole thing collapses. There’s not a lot left. Incidentally, we were the next big success for 4AD because we brought in millions and millions of pounds, which we were resented for—thoroughly resented for. We were out of our place, and Cocteau Twins were out of their place.

I know that Colourbox didn’t want to have “Anitina (The First Time I See She Dance)” on the B-side. Which is crazy because that song feels really ahead of its time too, and it’s aged so well.

The remix of “Anitina” is the one that really kills it. I listened to it yesterday—it’s a go-to when I’m high. It’s got so much of what was going to come. The dub bassline, the indie-dance crossover. Last week when we had the concert, Sean [Johnston] was the DJ and he started a club night with Andrew Weatherall called A Love From Outer Space. He was just telling me how much that song and “Anitina” completely changed their approach to music, and they’re world-class DJs. He told me, “A large part of what I’ve been doing for the last 13 years has been because of what you did.” I’m not making this up. I was like, “And you’re a total fucking hero.”

It was all in there. It’s almost like under the surface… Alex being in sound systems and being with his older brother Chris who made speaker boxes and circuit boards and shit, and there was me going clubbing with my brother when I was really young. I’m the same height as I am right now, but I was a stick, and could get into 18+ or 21+ clubs even though I was 13. So there was the soul background, the jazz background, the jazz-funk, reggae, ska—all of that dance stuff. When I went into uni, and I think it was similar with Alex, we were exposed to this white middle-class music. There was Public Image Ltd., Joy Division, Cocteau Twins, all of this kind of stuff. Suddenly, we were getting this indie sensibility while having this Black music background.

You can hear it to a small extent on “When You’re Sad,” but “Anitina”... the very next recording we did after “When You’re Sad” was “Anitina.” We did it on a 4-track in Alex’s bedroom and took it into the studio, dumped it onto a multitrack, and had Colourbox put some big drums on it. “Anitina” was a massive thing for Primal Scream, Andrew Weatherall, this kind of stuff. It brought a completely different sensibility to independent music.

Hearing you mention all this is really exciting because I’m also thinking about your influences and how that plays out in your songs. I hear a song like “Suicide Kiss” off 69 (1988) and the drum beat on that reminds me of The Flowers of Romance (1981) from Public Image Ltd.

We were big fans of PiL. One of Alex’s prized possessions was Metal Box (1979) in a metal box. I had the self-titled album with “Annalisa” on it. They were probably a precedent for us because with Jah Wobble and the big bass, it was kind of like a rock-y dub bass.. We also listened to a lot of John Peel and we’d pick out a lot of things from that. So there was Public Image Ltd and New Age Steppers, and Adrian Sherwood stuff. There was all this stuff going on with the Slits, and as kids we loved the Police. Anything with reggae in it, like the Clash. The reggae thing carried through, and with Public Image Ltd, Keith Levene’s mad guitar… there’s one song on “i” (1989) called “Insect Love” where I’m trying to play like Keith Levene, like really fast thrashy punk with a dub bassline. We did that one live. He died recently and I was really sad because I was in contact with the guy who was working with him; we were talking about doing a project together but he got really ill. So yeah, Public Image Ltd was a huge influence.

The first song I learned to properly play on guitar was when Alex gave me his acoustic guitar and taught me [Sex Pistols’] “Pretty Vacant.” (hums the guitar melody). That translated it into (hums a different guitar melody) which is on “When You’re Sad.” So, two main influences on our first single: “Pretty Vacant,” and the other one was “Atmosphere” by Joy Division. Those two kind of melded and then you get (hums bassline) to get that. Aat the end of it I was playing guitar and I was thinking of “Heroes” by David Bowie. You just have to pour in the stuff that you love and it creates a more complex tapestry of influences.

I’m interested to hear you talk more about the dub reggae influences. Before you made the Up Home EP (1988), you two had already known Adrian Sherwood, right?

Yeah. The guy who discovered us and introduced us to One Little Indian was Ray Shulman, and he’s the multi-instrumentalist genius from Gentle Giant. He became a producer and was working with One Little Indian, which he regretted for the rest of his life I think, because they’re not good people to work with… as with many hippie punk types, they’re selfish bastards and vain (laughter). When he was working at One Little Indian, there was a crossover with Lee “Scratch” Perry and African Head Charge, and Adrian was mixing them.

When we started working at One Little Indian, we got introduced to him, and he lived right up the road to us—it was like a 15-minute walk. We used to go up to his yard on the weekend and he would play music to us and we’d just hang out. When it came around to doing the M|A|R|R|S record, we went to Ivo and said that Adrian could produce this. And he could get the Sugarhill Gang’s rhythm section to come and play. He could produce this, and we could have a massive dance record. Ivo said “No, I want you to work with Colourbox.” That is one of those points in history… I’m sure there’s an alternate reality where we have a massive hit with Sugarhill Gang and Adrian Sherwood (laughter).

What about dub spoke to you and Alex that you wanted to incorporate it? You have songs like “Baby Milk Snatcher” and “Catch My Drift” that are obviously inspired by it.

When I was about 14, we went to what they used to call “blues.” If you watch [Steve McQueen’s] Lovers Rock (2020), you’ll see the essence of these sound system parties in the ’70s and ’80s. There would be these wardrobe-size speaker boxes. There were these 18-inch speakers, and 18-inch speakers can kill you (laughter). You get to the door and it’d be 50 pence to get in, you go in, and get some food. I didn’t smoke weed then because I was too young, and it wasn’t really a thing in those days, but all the dreads were smoking weed and you were packed solid in these living rooms. You’d get high, and dub would be playing and it was a visceral experience. Your body would be moving with the bassline and the dub echoes would be going out there. It was like being in a science-fiction movie, a grungy one, like Blade Runner (1982). On top of that, Alex’s brother had a sound system and used to shift boxes for them on the weekends when they had parties.

There were a couple youth clubs we’d go to in the East End of London and they would play that disco and soul music in the first part of the evening, but when it got late—as in like 10PM, because you’re like 12 years old and that’s late—they’d play reggae and dub. We all grew up with that reggae culture. Everyone would draw pictures of Rastas smoking spliffs on their exercise books at school and stuff like that. It was that culture—the red, gold, and green. And then Bob Marley came along and made it acceptable for so many other people. I didn't buy reggae or dub records—it was all soul in my house—but Alex’s brother used to get a lot of stuff and he’d get a dubplate flown in from Jamaica and that was a prized thing.

So the dub sound was always there, and I think that later on, dub music came back with Misty in Roots and other bands. It never really went away. When we first started making music, the first thing we bought was an Echo—a digital delay because we wanted that guitar sound like Cocteau Twins. And then we bought tape echoes—a Roland Space Echo and a WEM Copicat. We put everything through it—vocals, guitars, drums—and made those lovely sounds we remembered from being kids (mimics reverberating dub sounds). It wasn’t like, let’s put a little bit of echo on there, it was, let’s immerse everything. In retrospect, people would say we were creating these artificial spaces, which was true. No one told us that you were supposed to sound like a rock band. People go into a studio and try to make their band sound like a rock band; we were just trying to make artificial spaces that sounded good, that sounded dreamy. That was the whole dream pop thing. These were Dalí-esque soundscapes.

The dream pop thing is interesting. I’m 31 right now, for context. When I grew up and was listening to what is now considered dream pop and then went back to hearing your music, the thing that fascinated me was how the descriptor “dream pop” became so one-dimensional, like it got diluted. When I listen to A.R. Kane, it sounds like it encompasses the full scope of what dreams can be. Dreams can be terrifying, they can leave you confused and anxious, they can be joyful, and I love that I can feel so many different things from your music.

Dreams were very important for both of us. My mum grew up in a culture that was quite superstitious. A lot of astrology and occult thinking. Black magic. She would love to watch horror movies and we’d watch them with her. Quatermass and the Pit (1967) was my all-time favorite. We had this superstitious, creepy, occult thing going on. And in my dad’s culture, there’s very little separation between dream-reality and reality-reality; dreams are real. There are these shapeshifters that come into your dreams and steal away your soul. This is all stuff we grew up with, and it’s the same with Alex who has a Nigerian background.

We always used to think it was such a waste of eight hours of your day if you didn’t make something of dreaming. So something I got quite into was astral projection. And whether or not it’s just you tricking yourself, lucid dreaming is a real thing. We used to both experiment with that and talk about our experiences with that. We were also really into science fiction… telepathy and this stuff. And even down to our name: “Kane” is from the mark of Cain, from Hermann Hesse’s Demian (1919) about evolving humanity. When you grow up in the East End of London in the 1970s, you wanna believe in evolution, I’m telling you. You don’t wanna believe that this is the end game (laughter).

The dream thing worked real well for us. And when you do things over and over again, it does start to penetrate your dreams. Even just this morning, I had to send a box to Alex and I didn’t have his address. I woke up at 6, saw his email where he had his latest address, and then I fell asleep and immediately dreamt about him. It’s like, was that coincidence? Is it a telepathic connection? Was it “dream pop” happening? On top of that, in the dream he’s playing guitar and my older brother Paul was playing a big bass sitar, an instrument I’ve never seen before. And I could even hear the bass (mimics the sound of the bass sitar).

That’s what used to happen to us! And by pure coincidence, this morning I had a “dream pop dream.” What we would do is try to write them down, try to capture the atmosphere. That feeling of fear or immense beauty and euphoria, we wanted to capture that. The second song we recorded was “Haunting” and that was about a dream of being with an ex-girlfriend who I hadn’t really gotten over yet, me holding her hand and being in love again. And then a bit like in those science-fiction movies where the building starts crumbling away, you begin to realize that this is a dream and you don’t want to wake up. That feeling of instant nostalgia, of layers and layers of it. So creating this song “Haunting,” there were these simple lyrics: “You seem so far away / Last night I dreamt that I held your sweet hand.” That’s literal, but the sound and the emotion and the experience… there’s layers of feedback and arpeggios and unresolved chords—that’s dream pop for me.

This is so fascinating. Did you and Alex ever tell each other, “Oh let’s go to sleep right now so we can write a song about whatever we dream about”?

I don’t remember having conversations that way, but I definitely had that intention. I had a technique. I had this little mirror and on the other side of it was a flower fairy, you know the kind in children’s books. The technique I used was to find one object and look at it very intensely for 10 minutes until you fall asleep. When you’re really tired, just put it down. And in your dream, when that object appears—which it will—it’ll remind you to wake up. And not actually wake up, but wake up within your dream so you could lucid dream. That would trigger a lucid dream. Of course, the first thing you wanna do when you lucid dream is fly and pretend you’re Superman. But there’s a dark side to it, and I’m not gonna get into that (laughter).

Is there a song you two felt was the most successful in capturing what you dreamed about?

I think “Haunting,” which is a very raw song. It was very naïvely done, like “let’s try to capture that feeling.” But we didn’t know what dream pop was then because we hadn’t… invented it yet. That sounds so bad to say (laughter). One morning, Alex says, “I just had this dream and there was this music.” I told him to hum it for me, and because he would be on his way to work, he would sing this melody to me and be like, “that first part is a brass section and the second part is the string section.” And that was “Snow Joke.” He hummed it for me and I transposed it into instruments. We didn’t always work like that but that’s how we could work.

There’s a song on New Clear Child called “Surf Motel.” And that’s more like a John Carpenter movie, really. Or Stephen King or something. Alex had to run some errands in San Francisco and he parked outside this place called Surf Motel. I was just sitting in his car and it was a very dream-like reality. It was a bright, sunny day but there was mist in the air as you sometimes get in San Francisco. I saw this woman pacing up and down, and she was scantily clad—she was a hooker, I would say. A car came zooming along—a big Ford Mustang—and she jumped in front of it and slammed her hands on the bonnet. It screeched to a halt, and I saw her hair fall forward. It was a scene. The guy reversed, got out, and they went into a room together. Then the rain starts pouring. I was watching it like I was in a dream, and when she comes out she’s full of sunshine and light and happiness, and then he drives off. That was a literal… a waking dream, like from a John Carpenter movie. You don’t know what happened in the room—probably sex and drugs—but what I saw was this dark, dark scene transforming into this scene of sunlight. The rain ended. I wrote down my impressionistic view, as if I was writing down a dream, because it was so surreal to me.

I love that because it goes back to what you were talking about with your parents, about this blurring of dreams and reality.

There is a danger, though. Our minds are quite fragile, but if you’re feeling robust you can deal with being on the edge. I used to work for Ministry of Sound and one time, someone was describing what it was about and said it was an escape from the moment because life is so humdrum and dreary. I don’t see it that way. I see music not as an escape but an intensification of the moment. It’s when you can experience more depth and meaning. Like, how many drops of water are on a single blade of grass, reflecting the world around them, and we’re not aware of any of that? And they’re all magical. There is this idea of, how much can our mind handle of reality?

I’m curious about the science fiction aspect. How does it affect your music and life? Obviously there’s a lot we could talk about with Afrofuturism—do you see A.R. Kane in this lineage at all?

It’s funny because someone wrote a review of us this week and they say we’re science fictionists–that’s a term I just made up (laughter). They write about us from the perspective of being really into science fiction. Somebody interviewed me and we talked a lot about science fiction, and I really adore it and have from a really early age. My oldest brother Kelvin, he used to collect clothes, shoes, records, comics, and books. He’s a collector, like an OCD-level collector. He would bring home these science-fiction books but he wouldn’t give them to us. Instead, he would sit there when he finished and recite them, character by character, plotline by plotline. Not word for word, but it was enthralling for us—he was a storyteller.

When I got to the age of 11, he gave me Arthur C. Clarke’s Islands in the Sky (1952). It took me quite a while to read it because I wasn’t really a book reader, but a little while later he gave me John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids (1955). And that was it. From that moment onwards, I just read and read and read. What me and Alex would do was go to the massive local bookshop and steal books. We’d grab a science fiction book, steal it, and then go to school the next day and while everyone else was buggin’, we were reading. And when I finished, and he finished, we’d swap. We’d read a book in a day, or in two days. So what happened for Alex and I was that our reading age accelerated. And it’s because in order to read a science-fiction book, you need a dictionary, or some science manuals. There were so many theories about time travel, time paradoxes, quantum realities, all this stuff. There was all this hard science, and that’s why I studied science.

My kids bought me a box of 100 postcards of science-fiction novels for my birthday. And this is my favorite one (brings out a postcard). It’s Quatermass and the Pit. I remember watching it from a very young age. It mixed the occult with various sciences together. And that combination has been run through in a lot of movies ever since, even with Spielberg’s Poltergeist (1982), with it coming out of the TV set. It was ahead of its time.

Science fiction played a large part in the development of our minds. I don’t think that the dream of what science fiction promised came to fruition outside of the dark side where, yes, we are destroying the planet (laughter). I guess AI is a bit scary. Well, AI is usually pretty crap (laughter). I don’t really have much else to say about science fiction, but I still read it, though not as prolifically as I used to. I don’t like fantasy—when it crosses over into fantasy, it loses me. It needs to be grounded in things that I can test. I want to see what the hypothesis is. Is their thinking solid and strong? I like hard science fiction.

You mentioned “Snow Joke” earlier, and I think this more so applies to “A Love From Outer Space,” but when I hear those songs, they sort of sound like an analogue to the Latin freestyle that was happening in the US. Were you aware of that at all?

I don’t know the genre. Who is a proponent of that?

Exposé was the big girl group. There’s Lisa Lisa & Cult Jam.

I do remember Lisa Lisa. But no, it wasn’t an influence.

That’s cool, though, because there’s this convergent evolution of sorts. I always felt the beat and synth melodies sounded similar.

It has a big ’80s sound, doesn’t it? It’s really nice because we finish our sets with that now. We just go insane with it. When we played it last year, I just got into a fixed groove on it with these African drums on the outro. My sister just started saying “a love from outer space” over and over and didn’t stop. It started to turn into a chant. I pitched it differently this year. I brought in a friend who’s a clarinetist and we did that extended outro and turned it into a Sun Ra chant. It was absolutely wild.

I wanted to ask about your sister. I know she was in A.R. Kane but what’s it been like working with her in that, and then in Sufi and Jübl. What’s it like to be in that sort of creative partnership? I always find it interesting when artists work with family members.

It’s natural for us. Me, Alex, Maggie, my other brothers, his brothers and sisters—we played together, it was just something we did, whether that’s putting down sweaters to mark out goal posts in the park, or playing Monopoly, or whatever. We just always played together, and music was just another version of play. They say you “play music” and there’s a certain truth in that, that it is a form of play, of discovery.

It has its ups and down, as working with family always does. There’s always a family dynamic, isn’t there? When you’re the youngest child and you’re a girl and have four older brothers, there’s gonna be a dynamic there—the princess thing (laughter). And that hasn’t gone away, it’s still there. But yeah, we have a good relationship. I tend to be a bit overbearing at times—I know exactly what I want, and it can be a bit much. But there’s trust there as well, like I’m doing this because I’ve got something in mind and you trust that you will like it when we get there. It’s been interesting. Maggie was there in our very first live performances, first video, first recordings—she’s been there all the way through, really. She’s a hidden member.

I do know there were other people beyond you and Alex in A.R. Kane on those records.

Yeah, but the core was me and Alex. It was our chemistry and our writing. It’s the fact that we had been together since eight years of age, sitting next to each other at school every year. We created our own little world—the books that we read, the interests we had. They weren’t the same as anybody else’s, so we were our own little island and had our own way of speaking. It was near telepathy when we started making music because we knew each other that well. Telepathy isn’t just thought transfer—it’s empathy and trust and love, whereby you can actually go out there together, like in a marriage, almost.

Is there a reason why Alex doesn’t participate in any of the A.R. Kane interviews anymore?

New Clear Child (1994) was a very frustrating record to make. Alex had moved to America, I was still living in London, and I had to go to America, which was disruptive for me. It was a difficult time for him and me and our spouses and it really had to work the next time around—it had to be better. But it got worse. We were supposed to make the next album for David Byrne’s label, and Alex had written what he wanted to do but I couldn’t buy into it. So I was the one who stopped us from working together at that point. I said, “No, I’ve got more freedom than that.” It wasn’t working for me, so I just went back and made the Sufi album with my sister to exorcise that. Alex made music too, under the name Alex! for a year or two, and then he stopped making music. He’s never said why.

In 2015, when I said I was gonna go live again, I asked him if he wanted to join and he said no. He gave me his blessing but said no. In 2016, he said no. In 2017, I said I was gonna do more recordings and he said, “No you’re not.” (laughter). And that’s why I went with Jübl instead of A.R. Kane. So he’s never mentioned why, and I don’t really need to know to be honest—that was a lifetime ago.

I did want to ask about the one Inrain 7-inch you had with Alison Shaw from Cranes.

Ah that’s interesting because we’ve been talking recently about re-releasing it. We recorded another seven tracks together and we’ve been looking at those again, thinking about releasing them with the old tracks.

When did you record the new tracks?

Almost 10 years ago. The first ones were recorded in the ’90s and the others were recorded in 2012 or something like that. Alison hasn’t been very well recently but she started to do live work again, rehearsing again. We’ve been in touch so we’ll see. That was an interesting project.

How did it come about?

I remember the first time we met. I had a studio and she was interested in doing stuff together. I heard a demo and told her to come. We chatted for a couple of hours and we said, yeah let’s make a single together. And then Geoff Travis said he’d be interested in putting it out for the Rough Trade Singles Club. It’s a strange project because it was just a one-off. But we got back together and made some new stuff. And one track I sent was an instrumental and she actually recorded new vocals over it this summer. She sent it to me and I was like, “This is really nice but I don’t remember it.” And she was like, “Yeah, I just did it.” (laughter). So there might be some more stuff coming.

We’re winding down with the interview but I wanted clarification—who are all your older brothers again? What are their names?

My oldest brother is Kelvin, and he’s the collector. My next brother is Ackhim and he was the one who used to take me clubbing. And my next brother down was Paul, and he’s the one who introduced me to science. He’s a physicist and an ubergeek—he got me into computers and science and stuff. So I had all these different influences, which I was very fortunate to have.

Is there anything that you wanted to talk about that we didn’t get around to? Is there a question you’ve always wanted to be asked?

(laughs). Nah, I don’t have any questions. (points out my shirt). Arthur Russell. Is that the musician Arthur Russell?

Oh yeah, this is a shirt that’s based off a concert flier or something. It’s funny—I think of World of Echo and 69 as occupying the same world.

I don’t know it.

Oh, it’s one of the best albums, you’ve gotta check it out.

I will! I heard Maggot Brain for the first time this weekend. It was amazing. I was upstairs and Radio 6 was on, which is like our slightly alternative radio station, and there was this arpeggio playing. When we did our live set, we did the track “The Sun Falls into the Sea.” I brought in this piano arpeggio at the end and my sister sings over that and the clarinetist plays a solo. She sings a Beatles song, “You Never Give Me Your Money.” Long story short, I thought I heard our piano arpeggio playing. I thought that [my wife] Anita maybe had a recording of it. I came downstairs and was like, “Oh shit, this sounds like us! Who is this?” I looked and it’s Funkadelic! Fuck me! (laughter). It’s an insane sounding record. So anyways, World of Echo by Arthur Russell.

Yeah, that’s like the sort of “dream pop” I’m into, where it seems so vast. And it’s really just him and a cello and some effects.

Ah, we had a cello track on 69 called “Dizzy.” I was trying to summon up the experience of dreaming when things go wrong, of the dark side, when you can’t get back into your body. That only happened to me once. I started screaming. I was seeing myself from a distance, trapped in stone and trying to escape but not being able to wake up. The sound I wanted for that was the cello because of this deep hollowness. My friend Billy McGee, who is very much a Mozart freak—I just hummed it to him and he played it. I was gonna ask you a question. So, what’s the difference between A.R. Kane’s dream pop and the dream pop genre today?

I feel like dream pop has been diluted. You just add reverb, make sure it sounds atmospheric, and it always has to sound pretty. But with A.R. Kane, the nightmare facet of dreaming is still there. Like, my 15-year-old student was wearing a Slowdive shirt the other day, and when younger people—my generation included—talk about dream pop, their understanding of it seems to really be about this music sounding pretty.

It’s interesting, isn’t it? And maybe this goes back to the upper working class thing. If you come from a working-class background, your life isn’t all pretty. You’re not cushioned from the blows. Our family was attacked by neighbors and all kinds of horrible things happened to my parents. You grow up with that, and that’s an element of your reality, and you try to express it, to get it out. It’s catharsis. If you grew up in the suburbs where you have a nice school and everything’s fine… where’s the edge? I don’t know where Kurt Cobain got his edge from because I don’t know what his background was—I ought to read about him—but I remember listening to Nirvana thinking, well fuck, this guy’s got some troubled shit going on and I can relate to that.

There was all this surfer punk stuff at one time, like (in a mocking Californian accent) yeah, we’re gonna get on our skateboards and go to the beach, we’re gonna have a groovy time. There’s nothing wrong with it, but the edges are gone. It’s so smooth. Even Slowdive’s latest stuff is more interesting than the older stuff. Simon has this great big modular synth and everything goes through that, and the stuff now is more edgy. My thing is, and you concur, is that the dream pop thing now is… it’s painted by numbers. You get a Fender Jaguar, you get a delay pedal, you get a chorus pedal, you get a reverb pedal, and then bury the vocals in reverb. It’s very studied. If you listen to the Brandenburg Concertos, they’re edgy. But when you think about Baroque music in general, it’s what you play at weddings. That’s what happens.

Picasso said, “I invented this style. It looks kind of ugly, and people come along and make improvements on it, they make it beautiful.” That’s a completely paraphrased quote but it’s that whole idea. You’ve got Guernica—it’s ugly to the eye, it’s shocking. “Sulliday” is ugly and shocking to the everyday dream pop listener, which is why we didn’t get the big audience of that white, indie, middle-class kids. They want something that goes with the spliff that they’re smoking (laughter) or the acid trip they’re having or whatever. When we were listening to music when we were young, when we were getting into psychedelics and stuff, we were listening to Hendrix and the Velvet Underground and the Doors. It was stuff that was dark. It wasn’t all lovely and pretty. It wasn’t the Mamas & the Papas for fuck’s sake. The Mamas & the Papas are the modern dream pop equivalent, aren’t they?

There’s a question I end all my interviews with: Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

That’s a painful question.

Yeah, yeah.

(thinks). This is just a new impression, but when I perform live, I’m very generous with people. I don’t get prima donna. I’m there and anyone can come up to me and give me a hug. That’s one thing I always hated, when artists were distant from their fans and the support. I’m pleased that I’m not distant.

A.R. Kane’s new box set, A.R. Kive, can be purchased at the Rocket Girl website. It can also be purchased at Boomkat (UK) and Darla (US).

Thank you for reading the 101st issue of Tone Glow. See you in your dreams.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Such a wonderful and insightful interview! Thanks Joshua (:

I’m in my mid 50’s. I can remember vividly the effect that MARRS ‘Pump Up the Volume’ had on me (and plenty of other kids at the time) when I first heard it. What is this? where did it come from? how did they do this? where is it taking me? All sorts of questions. Of course I never really found out the answers! Reading the interview with Rudy Tambala provided me with a bit more knowledge of what I was listening to. Great interview. Keep up the good work and keep stimulating my brain!