Tone Glow 093: Kode9

An interview with Kode9 + our Writers Panel on Frank Denyers' 'Melodies' and GMEM's 'La Page À Musique, Musique Et Handicap'

Kode9

Steve Goodman, aka Kode9, is a Scottish DJ, producer, label owner and theorist. He started out as a DJ in the ’90s jungle scene while doing a PhD at the infamous CCRU at Warwick University. In the early 2000s, he got involved with the burgeoning post-millennial London garage and dubstep scene. His label Hyperdub became one of the key labels of early dubstep, releasing a whole slew of seminal records. Almost twenty years later, Hyperdub is still going strong and remains squarely focused on putting out fresh, cutting-edge music. Goodman himself remains busy as ever as a DJ and facilitator of various projects between music, art and theory. For this interview, Vincent Jenewein corresponded with Kode9 via email over a three month period, where Goodman opened up about his roots as a jungle DJ, the evolution of UK dance music, getting into theory, running Hyperdub, and his new projects Escapology and Astro-Darien.

Vincent Jenewein: You’ve talked about how getting into jungle around 1993 was what got you hooked on dance music. Do you remember the first jungle record you bought and what impression it left on you? You also started DJing jungle then, right? I guess I’m just curious what it was like, being involved in the scene at such a pivotal moment.

Kode9: I discovered jungle through a DJ Hype tape in around ’92/’93 in which he was scratching hardcore and jungle. I grew up in Glasgow, but at this point I was in Edinburgh. I wasn’t part of a jungle scene there—as far as I’m aware there was no jungle scene in Scotland at that point, just loads of rave, house, techno and happy hardcore. I’d started DJing in Edinburgh around ’91 but was playing a mix of rare groove, hip hop, New York house and the odd bit of hardcore. What got me properly into dance music was taking ecstasy at a psychedelic jazz/rare groove club in Edinburgh called Chocolate City and a hardcore/techno club called Pure. These were both at a place called The Venue, where I also co-ran a club night from around ’92-’94. I also attended a couple of big raves called Rezerection in big warehouses at Ingliston near Edinburgh.

After hearing the Hype tape I started buying early jungle compilation albums which would have 30 or so tracks on them—there were loads of these at this point. I was also picking up tapes of pirate radio stations from London, and listening to One in the Jungle on BBC Radio 1. I don’t think it was until around 1995 when I spent a summer in London and started going to Metalheadz at the Blue Note on a Sunday night, that I experienced a bit of the London scene which I suppose had already mutated to become more drum 'n' bass oriented.

As someone that wasn’t there, I’ve always been amazed by the speed and intensity of mutation in early UK dance music. With almost weekly mutations in sound, Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds have talked about feeling this very strong sense of “future-pressure” at the time, did you experience something similar?

I remember going to Black Market Records in London for the first time and they would batter the tunes at club volume and people would buy them with a wink. The speed and intensity of new tracks coming out—both sonically and in terms of their rate of mutation—was striking and not like anything I’d experienced before. For me, this evolutionary rate persisted through UK garage, grime and dubstep, and then the importance of record shops and pirate radio became totally decentred by the internet.

When did garage enter your musical life? It’s another genre that underwent a strange series of mutations, going from DJs playing pitched-up 4/4 US garage house records to 2-step to dark garage and early grime. At what point in garage’s development did you get the idea for the Hyperdub web magazine? What did you think about the commercial explosion of garage around the turn of the millennium?

I think I started hearing it around 1998, around the time I noticed that most of the drum 'n' bass I’d been buying was sounding pretty similar and I just stopped and started buying the UK garage. The cool thing about UK garage is that it seemed to be able to contain a continuum that stretched from the pop mainstream to underground dubs, holding R&B, dancehall, dubbier and darker jungle flavours all together in one scene for a while. I think ultimately, as with all these scenes, that equilibrium was temporary and unsustainable—economically, socially and sonically—and those separate strands evolved into their own sounds, as when FWD>> definitely and eventually became a hub for the darker side of the music.

Thanks to the likes of Blackdown, there’s hardly a more thoroughly documented (and theorized) scene in recent music history than early dubstep. But do you think there’s anything about that scene and moment in time that most people don’t know?

There was a bit of online discourse and in magazines, probably because it coincided with the blog and online forum explosion when members of the scene were able to document it for themselves. However, there aren’t really any books that have covered that period in any substantive detail. When we started the Hyperdub web blog around 2001, it was to provide a home for writing about some of these offshoots from garage, specifically focusing on the influence of Jamaican music culture on electronic music in London, and featured interviews with the likes of Ms. Dynamite, El-B, Zed Bias, Oris Jay, Groove Chronicles, Horsepower [Productions], Dizzee Rascal, Wiley and more, alongside some essays by the likes of Mark Fisher, Kodwo Eshun and Simon Reynolds.

Around that time, the night FWD>> started at the Velvet Rooms, eventually moving to Plastic People. Ammunition Productions—Sarah Lockhart & Neil Jollife, who ran and did distribution for labels like Tempa (Horsepower), Ghost (El-B), Bingo (DJ Zinc)—set up a website called Dubplate.net which I ended up running for them and kind of operated in tandem with the editorial policy of hyperdub.net. Then Ammunition, who also ran FWD>>, joined forces with the pirate radio station Rinse.FM and around 2003 I started hosting the FWD>> show on Tuesday evenings from 7-9pm just before the Roll Deep show. Before that, since around 2001, I’d been doing a radio show called Hyperdub Transmissions on the net radio station Groovetech.

Was there a specific moment that made you want to get away from being labeled as a “dubstep” (both for yourself and the label)? And how do you feel about the state of the genre now?

Apart from occasional b2b’s with Mala, which I always enjoy as a chance to dig out some older tracks from both dubstep and grime, I don’t really keep up with the scene too closely now. I suppose I started drifting around 2008-9 after the smoking ban in clubs in the UK—as weed disappeared, and alcohol and uppers took over, the basslines became more focused on the mid-range and the rhythms had become more fixated on the half-step. I came to this music from the swing and syncopations of UK garage, so I felt that the half-step trudge wasn’t really for me. And then it all blew up in the US, and that amplified the things I was already drifting away from.

Could you say a bit about your time at the infamous CCRU [Cybernetic Culture Research Unit]? And how did you first get into philosophy and theory?

I was at Warwick [University] from around 1996 until 1999. I’d already been a DJ for 5 years, and had an interest in philosophy after coming across existentialism as a teenager, and had been particularly interested in Foucault and Nietzsche as an undergraduate, but hadn’t really seen anything which brought these two worlds together. I read an article in the Guardian about Sadie Plant in the mid-90s and it sounded like she was at the apex of a really interesting conjuncture of rave, technology, and philosophy. At Warwick, coming across the writing of friends such as Mark Fisher and Kodwo Eshun allowed me to begin exploring ways of fusing these different dimensions. I’m still on that mission.

I’m curious about the trajectory of Hyperdub over the years. Were there conscious decisions for the direction the label should go, or is it just down to the producers you are involved with at the time?

I’m not someone who likes to micromanage other people’s music, so I do feel the label has evolved with the learning process of its artists. My job is to keep that all on track and when it feels a bit stale I will look to add to the current roster, and tweak the overall direction of the label. I’m always listening to demos for my DJ sets anyway, but I usually sign music that doesn’t merely fit into my sets, but often is what I want to listen to away from the club.

I get the impression that in the last decade, Hyperdub—and perhaps dance music as a whole—has become less genre-specific. How do you feel about the concept of genre today?

Being in a particular genre does bring with it a sense of collectivity that is quite unique and galvanising, and also fulfils the function of nurturing and incubating music, but there politics come with that. Things are much more fragmented but simultaneously more open now, for sure. Despite all that, I always existed at the periphery of any genres I participated in, so I think that’s just become the norm for many artists now, especially if you’re not making house and techno. There is a certain freedom that comes with being on the edges and interzones, but it doesn’t always result in music that is more vital.

Where do you see yourself as a DJ in 2023? Is there any particular sound or producer that you are excited about playing right now?

In the last few years, I’ve been enjoying exploring the back catalogs of footwork, juke and jungle alongside new music from myself and others making music at that tempo. I’ve come full circle to where I was at in the mid-90s I suppose, with a certain need for speed in my DJ sets. Saying that, I do enjoy playing all-night sets—which I started doing at Plastic People in the mid 2000s and continued every January at our Ø events until just before the pandemic—or doing b2b with friends which take me out of my current musical pre-occupations. To be honest though, it’s hard to say anything as a DJ these days and not sound like a boring cliché repeating platitudes that have been rehearsed 50,000 times.

What was the impetus behind the new Flatlines imprint? What makes the format of the “audio essay” appealing to you? What got you interested in projects that are more narrative-oriented?

I suppose it is a resumption of what I mentioned earlier regarding the CCRU, i.e. pursuing a format which brings together theory, fiction and sound. The audio essay is an interesting method as it is part documentary fiction, part radiophonic drama, part audio book, part experimental music and sound design and so on, but without being any of these. I see it as mutating, for example, what Chris Marker did with essay film and Kodwo Eshun’s notion of sonic fiction but without taking these as restrictive, generic blueprints.

There’s a lot going on in your new Astro-Darien project—Scottish colonialism, video games, alternative histories and speculative futures. Could you give a brief overview of what the project is and how it came to be?

It’s a complicated back story but here is an overview: Provoked by the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, Brexit and the pandemic, Astro-Darien is a 26-minute sonic fiction about the break-up of Britain narrated by synthetic Scottish voices and framed as an eponymous video game. It is the 2nd release on Hyperdub’s sub-label Flatlines, with artwork from my long-time collaborators Lawrence Lek & Optigram. Whereas the first release on the label, Mark Fisher and Justin Barton’s On Vanishing Land, wove an audio essay around a walk along the South East Coast of England, Astro-Darien takes off from a road trip along the North Coast of Scotland.

The documentary fiction spirals between the role of the catastrophic Darien Scheme in the late 17th century in the founding of the UK, when Scotland failed to colonise part of present-day Panama, and the contemporary disintegration of the union. The scheme almost bankrupted an already impoverished Scotland and led to it having to enter into union with England. So the story moves simultaneously forward and back in time, with the present at the apex of the spiral, sweeps up both the inception and speculative demise of the union. The story extrapolates from the race to become the UK’s first vertical satellite launch station currently playing out between Sutherland Space Port and the Shetland Space Centre. So independence is framed as an exercise of escapology, a jailbreak and exodus to an orbital space habitat, with all the risks and dangers that entails.

The loose plot follows a game designer from a fictional games company called Trancestar North who, in attempting to lift the dark spell cast by Darien, models a counter-future by ingesting cosmism, the history of racial capitalism and the demise of Empire into T-Divine, the geopolitics simulator of the game engine. She follows the Brexit algorithm as it runs to its logical conclusion.

The project was Initially conceived as an audio essay for diffusion on François Bayle’s 50-speaker Acousmonium for INA-GRM at La Maison de la Radio in Paris in March 2020, but subsequently postponed by the pandemic. In June 2021 it became a three-screen installation at Corsica Studios in South London and it wasn’t until October 2021 that the Paris event happened. With 50 speakers it made it possible to diffuse the voices and sound design around the auditorium. Most of the speakers were spread out in front across the stereo field, but some also surrounded the audience. This playback happened in complete darkness.

I was very intrigued by the title of your new album, Escapology. How did you come up with that title?

My use of the concept of “escapology” appears first in relation to the Astro-Darien project—it’s a quote from Benedict Singleton’s essay Maximum Jailbreak about the future of humanity, and about the origins of ideas of space exploration in Cosmism. In it he makes a distinction between escapology and escapism, between something strategised and sustainable on the one hand and short-lived and doomed to failure on the other. So I think he is continuing the pejorative sense of “escapism.” I’m transplanting all that stuff into a fiction about the break up of—and escape from—the UK, so it takes on even more complicated resonances than what he intended. I suppose you could also transpose it into thinking about dance music also.

Kode9’s music can be found at Bandcamp and the Hyperdub website. Kode9 is also touring this spring. Find his tour dates here.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Frank Denyer - Melodies (Another Timbre, 2023)

Press Release info: A unique double album, featuring the first recording of Frank Denyer's extraordinary Melodies series from the mid-1970s. The project arose from Frank’s ethnomusicological studies of the time, which had forced him to question the most fundamental elements of music. He had to ask himself “what is a melody?” and “what is a note?” His typically eccentric response was to write a series of 25 pieces, starting with single-note melodies, then melodies with two, three or four notes, gradually becoming more complex until the last piece, which contains 14- and 15-note melodies.

Purchase Melodies at Bandcamp.

Dominic Coles: When a musical material is heard and explored on its own terms, something incendiary happens to the generic boundaries that initially defined and categorized that music. It’s something akin to an explosion, or maybe more like a dissolution: the bounds of genre seem to wipe away giving us auditory traces of a logic and form that is native to the sounds themselves. These are glimpses, perhaps, of the material’s underlying topography—in our audition we can in fact touch our materials. In these moments it seems trite and unmusical to speak about genre or style (the only thing most critics are capable of hearing!).

Frank Denyer’s Melodies is deeply attuned to the possibility of this explosion—aware of a music hidden behind the surface appeal of genre. It is one that emerges out of the material’s own movement and not from our desire for how the material should sound and present itself in time/space. In Melodies, however, this explosion does not take place.

Our materials are the products of social and historical forces that determine them—an outside that shapes, sculpts, and inhabits their topography. There is no material without the outside: these social forces are imbricated with the sounds themselves. As an ethnomusicologist, Denyer would hopefully be hyper-focused on the relationship between history, context, and sound production. His commitment, however unconscious, to Western art-music notions of experimentation, abstraction, and reduction (don’t these pieces sound uncannily like Morton Feldman? Don’t the scores seem too similar to alternative notation strategies devised in the (post-)Cagean moment?) drives a wedge between the material and the outside, obscuring the relation between the sounds and the contexts that produced them.

What I think he is aiming for is a kind of universalized experimental and experiential form of music making—perhaps something akin to Amacher’s notion of a renewed popular music.[1] A music which is a popular music because it emerges from the shared capacities for audition that exist deep within our bodies and cognition. This is an admirable pursuit! That kind of composing does not come easily though: it requires an absolute focus on the sound, a pursuit of the sound that entirely dissolves our desire and expectations for how the material should be—that follows them wherever they may lead, even if we don’t like the end result. In Melodies, what we are in fact hearing is Denyer’s desire for the explosion but not the explosion itself.[2] In spite of this, these pieces exhibit a focus and sumptuousness that is, at times, electrifying—a testament to the skill and dexterity of Denyer’s compositional hand. If only this were enough.

[5]

[1] “I want to make a music that becomes popular - that makes people say ‘unheard of’ because it develops too sensitive areas. A music which awakens you to the ENERGY.”

[2] For an example of a synthesis between material and outside hear Marina Rosenfeld, Warrior Queen, and Okkyung Lee’s P.A. / Hard Love and Jana Rush’s “Suicidal Ideation - Aural Hallucinations Mix.”

Marshall Gu: Melodies plays like a highly technical exercise, like witnessing Frank Denyer slowly plot out melody under the tightest constraints—a single note to start!—and building from there. “Melody: Now with two notes! And now with three!” That the notes themselves are played on different instruments is welcome, as are Denyer’s trademark unconventional instruments: stones are tapped irregularly on the second song, and later songs feature instruments I’ve never heard of (e.g. “membrane”). After these 25 pieces, I feel no closer to answering the question that drove these explorations in the first place (“What is a melody?”). Or, most damningly, at no point did I think, “Ah! Melody.”

[5]

Sunik Kim: The sustained, microscopic intensity of the one- and two-note pieces gives way, somewhat paradoxically, to a clouded sonic anonymity in the later multi-note territory. Rather than being a process of augmentation as intended, this numerical progression actually strips away, bit-by-bit, the foundation of the underpinning concept. As the vocalizations—literal and instrumental—gain more complexity and structure, they slowly reveal themselves to be attempts at a kind of abstract, universal language: an extraction and reduction of common elements from disparate concrete sources with their own historical and musical trajectories. Through this dynamic, the work increasingly exudes a familiar, if often well-meaning, naïveté: that of the composer who only knows the material of music and only knows to comprehend, process, and attempt to change the world through that medium.

The fundamental flaw in Denyer’s concept is that questions of history and society are mapped onto free-floating questions of the sensory and perceptual experience of music as such. A false parallel is made between an implied process of historical development and the self-development of a “novel self-sustaining musical language.” The originating question of the actual societies from which these “restrictive forms” emerged becomes its abstract opposite: “When is a change of pitch perceived as a new note, and under what circumstances might it appear as just a variant of the same one?” Here, the consequences of the above naïveté become clear. When the language of music is applied to history rather than the reverse, we all too easily end up in a “color-blind” world of notes and sounds. Denyer:

When I started off as a composer, I was very annoyed that journalists would often ask, “How do you think of your music in the context of British music?” I didn’t want my music ever to sound particularly British, or even African or Indian or Japanese or other things I’ve been interested in. I don’t think that way. If these things have gotten deeply into me, without my thinking about it, they’ll come out in some way, no doubt. I’m not conscious of it, and don’t want to be conscious of it, really. Some of these things are kind of contradictory—but that, I think, is the complexity of where we are.

“There are power structures that have been to people’s disadvantage, and some of them we belong to, and we must be conscious of that—of course we must be! But that doesn’t mean that we’ve got to separate ourselves into these little boxes. [emphasis mine]

What Denyer misses is that there is a world of possibility between remaining separated into predetermined “little boxes” and submerging difference altogether in a false universalism. Rather than using abstraction to return to the originating point and enliven it, the project only circles on the surface level where it began, obscuring rather than surfacing the potential truth within.

[5]

Eli Schoop: The press release for Frank Denyer’s Melodies is a treatise on what a melody is and how to interrogate our conceptions of one, stemming from the composer’s ethnomusicological studies from the mid-1970s in India, Kenya, and Japan. The two discs span experiments in 1- to 14-note melodies, categorized by instrument and length. Everything about the collection screams academic meticulousness, a scientific exploration of what music can be. Denyer seems thoughtful and altogether willing to think without inhibition and preconception, which is always important. What I gleaned from these pieces is that Melodies should’ve stayed an essay. 97 fucking minutes of awful, grating sound tests. Jesus Christ. I guess Denyer got an emotional reaction out of me, which can be an artistic accomplishment in itself. Nevertheless:

[0]

Jinhyung Kim: The structure of Melodies immediately brought to mind György Ligeti’s Musica ricercata: a set of eleven piano pieces where the number of pitch classes used in each piece climbs, one-by-one, from two to twelve. Melodies begins with a few one-note tunes, then a few two-note ones, then all the way to fourteen and fifteen. It doesn’t have the same sense of strict progression as Musica ricercata, given the looseness of what counts as a “note”—ornaments, while liberally deployed, don’t seem to count, and it’s ambiguous whether certain unpitched percussions count either; there are also interludes that break up the pattern. Despite this, one registers an unfolding that occurs over time: the gentle eddy of the first piece’s bamboo flute melody lingers as a memory as one hears the four-note melody for viola—still moving in circles, but looser and lither, tracing concentric arcs around that memory.

After the album’s midpoint, however, this overall movement is difficult to distinguish, having dissolved into a general context of timbral subtleties rather than any structural teleology. Luckily, the former is Denyer’s home turf—the solo and duo pieces spotlight the expressive lexica of voice and strings with remarkably delicate clarity, the way a jeweler might turn their work over and over under a magnifying glass; the pieces for larger ensembles trace thin yet seamless lines from instrument to instrument in a masterful practice of klangfarbenmelodie. I’m also partial to the pieces that center bass, tuba, and other low instruments, out of which Denyer manages to draw resonances that are as exquisite as they are tectonic.

Of course, all this is independent of whatever diffuse order the album’s organizational scheme may provide. Melodies is caught between this edifice and the uncompromising devotion to timbral arrangement characteristic of Denyer as a composer; I can’t help but feel that commitment to one or the other would’ve led to a whole greater than the sum of its parts—not just a somewhat overextended collection of beautiful passages.

[5]

Gil Sansón: Impervious to trends and following a singular path, Frank Denyer has been mining a few key principles for decades, as part (and apart, to some degree) of the English experimental music scene alongside composers like John White, Laurence Crane, and James Saunders. This is music that follows Feldman’s dictum of “do not push sounds around,” with each sound having plenty of room to be itself; it’s an aesthetic proposition where a flute and an axe on a stump are on an even standing and status. This music appears to be about the inherent drama of sound—that which is there before we put our intention and own cultural baggage to its reception. Since the ritual is downplayed, the sounds feel like they’re expressing themselves. Still, they bear traits from Asian cultures—via wooden and bamboo flutes—without offering commentary or striving for authenticity; it’s more like an acknowledgement of the kinship that’s possible as a result of unlearning of Western cultural trappings.

A more or less obvious model for Melodies would be Cage, but also the English tradition that starts with Cardew and the Scratch Orchestra. There’s an embrace of the small, unambitious sounds—the kind that could be music but somehow want to retain their ambiguity—gives Denyer’s music much of its charm. It’s intimate and open, pointing towards the possibilities afforded by centering on one-pitch melodies played in a klangfarbenmelodie style and with microtonal inflections, though it never feels as “look ma, no hands” as so much microtonal music does. It sounds, and feels, like a group of people making timeless music with the few objects and instruments available to them.

[9]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I have really fond memories of “Two Voices with Axe” from Frank Denyer’s 2015 album Whispers. I would listen to that track on repeat, constantly moved by the sheer shock I would feel whenever hearing the axe striking wood. After listening to the rest of his work, both solo and in the Barton Workshop, I remember largely understanding that his records provided a very specific purpose for me: that of understanding music as the product of specific materials, and how readily my body reacts to them. The way Denyer approached minimalism contained facets of what I had already expected from such pieces—silence as a compositional tool, an appreciation for sound at its basest level—but there was something especially affecting about how dry they felt, like they didn’t care about the “quality” of the actual sounds being produced.

Let me explain this through various tracks across Melodies. The album’s underlying conceit is that of specific melodies constructed from a certain number of notes. This, to me, is already a surrendering of the music to a specific formalism that is unconcerned with how it sounds (as in, if it sounds “pretty” or “good” or “interesting”). I am immediately approaching the music with a different mindset. When I listen to “one-note melody (bamboo flute),” I am simply reflecting on the way air moves through this instrument made of grass, and the entire timbral range it contains because of it. When I hear “one-note melody (French horn & stones),” I am reminded of how much I hate that damned brass instrument for no real reason, but I also marvel at how the stones are “played” at a rhythm that resembles the sound produced when texting on an iPhone. The following track, “one-note melody (flute & membrane),” is extremely obnoxious and sounds like a fly buzzing in my ear. I love that I have all these thoughts and reactions because they point to how temperamental our interactions with sound are. As much as I’d like to think I’m a smart person who exercises critical thinking, I am still beholden to my body’s reactions to specific pitches and timbres and rhythms. How lovely to be reminded of my smallness.

As Melodies progresses, the number of notes in each melody increases. There is, of course, a threshold that is crossed as the pieces become more complex where I start to approach the works in a more traditional fashion. Understanding how that plays out is a delight, but the combination of instruments is maybe the most exciting part of the album. I cannot stop laughing when hearing “two-note melody (double bass, drum & guiro)”; the sustained notes from the double bass and rumbling drum are nothing out of the ordinary, but the guiro is such an unexpected addition, and each tiny tap conjures up a massive reaction. The percussion on the first interlude plays a similar role too, which is impressive given how this could easily sound like a typical free improv track if the framing were different. This is Melodies in a nutshell: a series of tracks that asks you to consider the associations you have with sound, sounds, and combinations of sounds.

[6]

Adesh Thapliyal: Denyer’s Melodies was born out of a certain moment of post-60s cultural exchange, when the Western avant-garde turned towards folk music, “Oriental” music, or other Indigenous traditional music to express the revolutionary political and aesthetic impulses of that young and rebellious generation. Denyer composed Melodies while conducting ethnomusicological research in West Asia and India, where his encounter with foreign musical cultures made him curious about the “archaic origins” of music itself. Melodies is an ambitious expression of Denyer’s struggle with that origin, composed to “enable the listener to experience the birth of melody... within the course of a single work.”

There’s a little bit of hippie naïveté to the history that Denyer sketches in his 25-part composition, which begins with minimalist one-note bamboo flute and gradually adds new instrumentation and pitches, until we end with a performance by full string quartet. For one, though the simple bamboo (or bone) flute is one of the oldest known instruments, found as early as the Aurignacian culture in Paleolithic Europe, even early examples of the instrument demonstrate the ability to express multiple pitches—which jibes awkwardly with Denyer's positioning of the flute as the pre-melodic Ur-instrument of his phylogenetic tree. The Oriental framework of the composition also strikes me as awkward. The primitivist half of the album, which includes such exotic instruments as a santur and a sneh, a Denyer-created instrument with a Sanskrit-derived name that resembles an erhu, eventually gives way to a more complex, multi-pitch back half with these foreign instruments now absent from the melody (some, such as the guiro, are still present in the percussion).

I’m not interested in dismissing Denyer’s work as problematic. Western exploration of non-European music in that moment of post-colonial revolution was doomed to be blinkered at first, though laying the groundwork for better things going forward (like, for example, Denyer’s later work with shakuhachi player Yoshikazu Iwamoto). But, nevertheless, there’s a part of me that can’t bring myself to care much about this Melodies; not when, say, Bengali composer Salil Chowdhury’s exploration of Western harmony in the context of classical Indian music remains unheralded and unknown to Western scholarship, to give just one example. My point is that art music that goes in the “reverse direction,” so-to-speak, is bizarrely absent from our histories of the long ’60s, despite the fact that the independence struggles in the Global South shaped, if not dominated, the intellectual and aesthetic conversations of the era—a conversation well-represented in Denyer’s work. In that context, this new recording of Melodies feels like a minor addition to an already crowded field, and an unnecessary prelude for a composer who went on to greater things.

[3]

Average: [4.75]

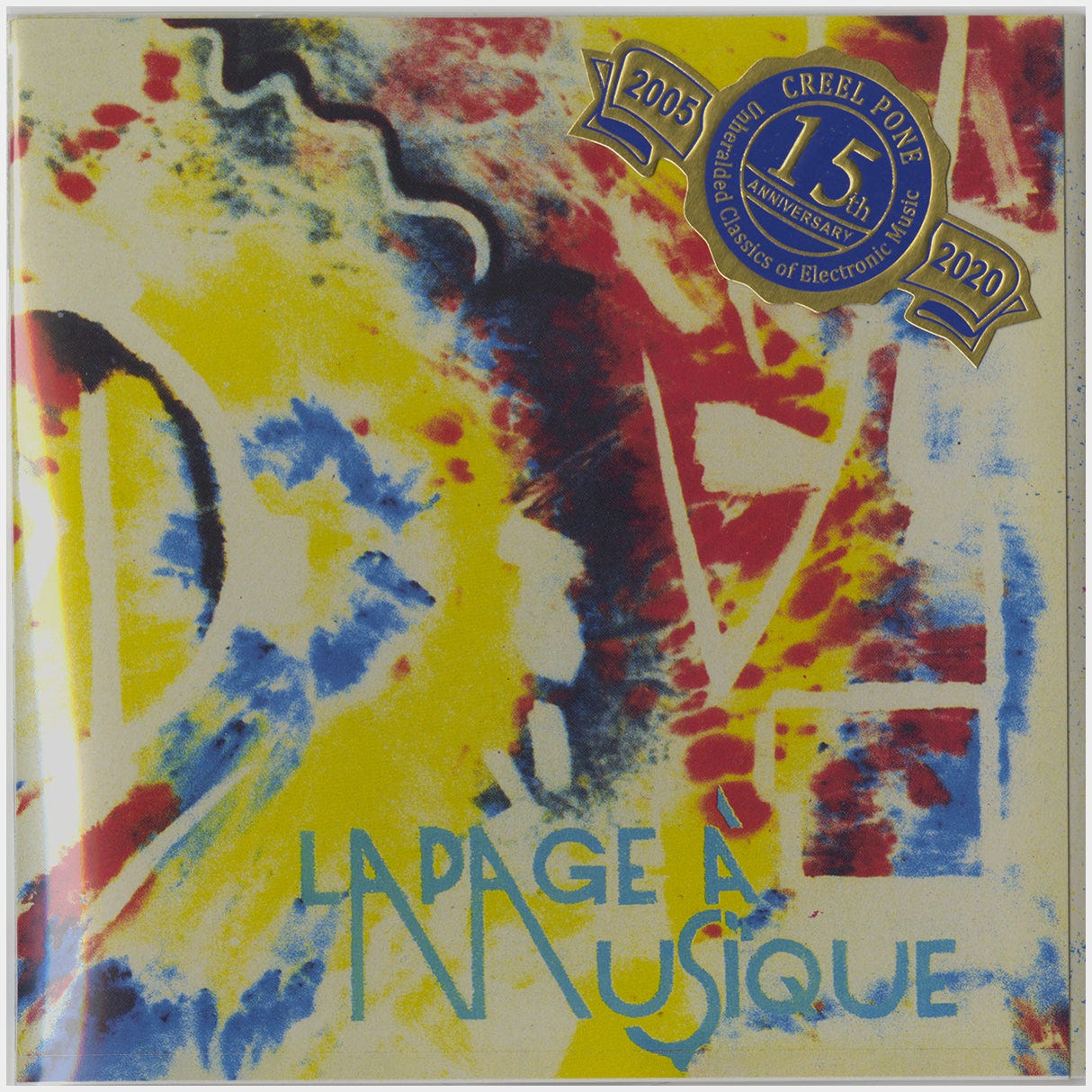

Groupe de musique expérimentale de Marseille (GMEM) - La page à musique (Creel Pone, 2023 reissue)

Press Release info: Inaugurating the C.P. “Shorts” sub-series (featuring newly discovered titles that are less than 30m total, at a premium) here is a replica edition of an undated (although I’m guessing from the equipment & personnel credits this was recorded in the early 80s) “Private” gatefold issued by the Groupe de musique expérimentale de Marseille (aka the GMEM; now the gmem-CNCM-marseille) covering the group’s work with Provence-area handicapped youth musicians.

Much in the spirit of Basil Kirchin’s Worlds Within Worlds 3 & 4 the deft, often invisible touch of the group’s in-house composers Jacques Diennet, Lucien Bertolina, Martine Olivares, & Patrick Portella serves to only enhance and highlight just how great the discovery & joy of music can be. The two extended vocal-drone pieces that make up the A-Side wouldn’t be out of place of any number of contemporary albums, and the chopped & screwed Casionics that (impossibly, largely) make up the B-Side certainly have much en ligne w/ the fantastic Glenn Williams title (CP 208 CD) in their raw, unbridled application of free forms & structures around the possibilities of the Tape-Studio.

Purchase La Page À Musique at the Creel Pone website. (Note that the website is currently down until March 5th; what is currently linked is the archived page. The link will be updated once it returns.)

Gil Sansón: La page à musique comes from a time when “experimental music” wasn’t self-conscious—when it wasn’t a style recreated with vintage equipment—and its soundmaking was like a child discovering echo and reverb in a cave. Here, the Groupe de musique expérimentale de Marseille is joined by a group of kids and teenagers (I’m reminded of a much more recent piece that taps the adolescent experience in Marina Rosenfeld’s Teenage Lontano). The heavy use of analog delay dates the music, but it isn’t jarring or distracting; rather, there’s an earnest motivation behind the music. This isn’t mandatory listening, but it is always interesting to revisit these time capsules; each epoch has a spirit and unearthing objects like this lets us appreciate it, unmediated by corporate coding. In all its flawed glory, La page à musique captures an adventurous attitude that would today sound calculated and cynical, and while this reissue isn’t likely to put the GMEM in the same league as MEV or the Spontaneous Music Ensemble, there’s a joy in the act of making music that shines here.

[7]

Vincent Jenewein: This little historical oddity brings together naive synthesizer medleys, amateur acoustic improvisation and electroacoustic weirdness. It’s less of an album in the proper sense and more a document of what happens when people get together and just make some noise without adhering to any preconceived notions of what they should be doing. My favorite passages here are ones where it’s clearly just people having fun with a tape echo, spontaneously feeding it with whatever they come up with, and hearing it echo back their little nonsense drenched in trails of feedback. A simple, timeless joy.

[7]

Eli Schoop: In such a dense and heady genre as musique concrète, a dash of humor is always appreciated. GMEM treasure the idea that experimental music can readily include fucking around in between the intellectual pursuits of deciphering Casio presets and their multiplicities. “Improvisation 1” and “Improvisation 2” split their time examining how you can warp the human voice into alien qualities a la Fourth World Magazine, enveloping the listener in holy chants. The album’s centerpiece “Ou on fait un truc génial” changes the pace, moving into drone and free jazz.

By “Electro-musique casio, pt. 2 and 3,” disparate Katamari sound effects are whizzing around constantly. It’s imperative that their music is self-contained, as if it spontaneously appeared one day and had to be captured by curious anthropologists. But it’s clearly not random or accidental that GMEM’s spirit is infected by whimsy. They spend their economically, frontloading the first half with concepts aplenty and letting the latter half wind down as if to say, “Thank you for coming.”

[6]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I’m largely drawn to La page à musique for providing a glimpse into a particular scene I was never really privy too. (Michel Redolfi is the most widely known member of GMEM, surely, but he’s not on here.) Notably, this is a unique disc in the institution’s catalogue for being a collaboration with handicapped youth. I never would’ve guessed that were the case, though, if it weren’t for the description, which could lead into a conversation about how experimental music offers space for a creative boundlessness that isn’t guided by able-bodied privileges and expectations. But what really gets me excited about these tracks is that they’re a reminder of experimentation as play, especially in how the voices manifest: they’re a cryptic presence in “Ou on fait un truc génial,” hiding underneath a wavering synth like a creeping specter; they’re jovial in a “let’s just see what happens” sort of manner on “Improvisation 1”; and they elegantly mesh with blippy electronics across “Improvisation 2.” The Casio tracks are a hoot, too, simple and silly in a way that contemporary electronic music needs to channel if I’m ever wanting a laugh.

As a standalone album, it’s great—and at a lean 26 minutes I can’t complain—but I really appreciate how this is just a simple record that is helping me to more fully understand 1) musique concrète from this time, and 2) the musical landscape of Marseille (Patrick Portella, who plays on this disc, has a masterpiece in Le voyage d’hiver, and that album features Brigitte Balian of the Marseille coldwave band Martin Dupont). The rate at which Creel Pone is continuing to release stuff, along with their minimal marketing, makes listening to these CDs feel more like legitimate discovery, not as Albums I Have To Hear Because They’re Important and Groundbreaking. I feel like I’m putting pieces to a puzzle together, and that is a lovely experience to have with any archival work in 2023.

[7]

Shy Clara Thompson: One core facet of experimental music that will always make it fascinating to me is that anything can be music. Sound can be radically recontextualized depending on how you frame it, transforming the rumblings of the everyday into something exciting simply by tuning your ears to a different frequency. As a consequence, an equally important function emerges: anyone can make music. Similar to the way in which a banal racket can be reframed into something extraordinary, your perception of that racket can change depending on the knowledge of who (or what) is responsible for making it. Proficiency and expertise will probably always be valued as long as we continue to fill our lives with music, but there’s something exciting about hearing an achievement from someone less experienced.

The Groupe de musique expérimentale de Marseille (or GMEM) are no exceptions. The French collective of musicians write in the liner notes of this release that they had no expectation of recording music together when they took a group of disabled teenagers under their wing. They simply shared their knowledge of electroacoustic music with the kids and provided them an outlet to express themselves; the rest came together naturally. The guiding hand of seasoned musicians can clearly be felt on the technical side—for example, on the layering of vocals in the two improvisational tracks or the meticulous programming of Casio keyboards—but the more generative aspect of the music has a distinctly amateur feel. Young voices warble and shriek into microphones and tiny hands plunk out precocious melodies on synthesizers.

The resulting recordings—undated, but likely assembled in the early ‘80s, lovingly replicated by Keith Fullerton Whitman’s bootleg label Creel Pone—are a pleasant surprise for everyone involved. The kids probably never expected to be musicians, the GMEM didn’t expect to be mentors, and I didn’t expect to be impressed by music with such fantastical context. The appeal of experimental music rests on one universal truth: everyone loves an underdog story.

[7]

Jinhyung Kim: La page à musique, per the liner notes, was recorded by GMEM in collaboration with Provence-area disabled youth. It’s as tough to parse out who does what in these pieces as it typically is to distinguish various GMEM members’ individual contributions, but I like to imagine the vocals on “Improvisation 1” as the collective antics of kids in a studio—kids who must’ve been as surprised and delighted at the aqueous otherworld that came out the other end as I am when Dall-E Mini spits out something strange and wonderful after digesting whatever keywords I fed it.

This commingling of the alien and the familiar is what grants La page à musique its charm: “Improvisation 2” blurs vocals and synths together in a way where one often seems to resolve into the other; the “Electro-musique casio” pieces that dot side B of the record are playful yet uncanny in their rendering of what sounds like an innocuous tune a child might hammer out on a piano into rudimentary analog synth facsimiles. “Au clair de la lune” captures delayed and pitch-shifted banter, turning phrases like “right on, man!” from joking affectation to something vaguely sinister.

The clearest manifestation of the record’s collective spirit is “Ou on fait un truc génial,” a steady drone that then erupts into a raucous jam session with cascading drums and a belting saxophone before ending abruptly and with laughter. It feels like a relatively transparent window into what’s otherwise a firmly opaque surface; it’s a disparity whose extent suggests a plethora of musical possibility lying in between placid electroacoustica and no-holds-barred improvisation, which the material on La page à musique merely triangulates without filling in. In other words, I wish there was more. I don’t know whether that further territory wasn’t explored, or if it was but simply wasn’t put to tape; I’ll try not to be greedy though—that this early a document of such collaborative experimentation survives at all is a small blessing.

[6]

Average: [6.67]

Thank you for reading the ninety-third issue of Tone Glow. No more escapism (pejorative).

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Fascinating to see the different responses to Frank Denyer's music. I love this model of reviewing!