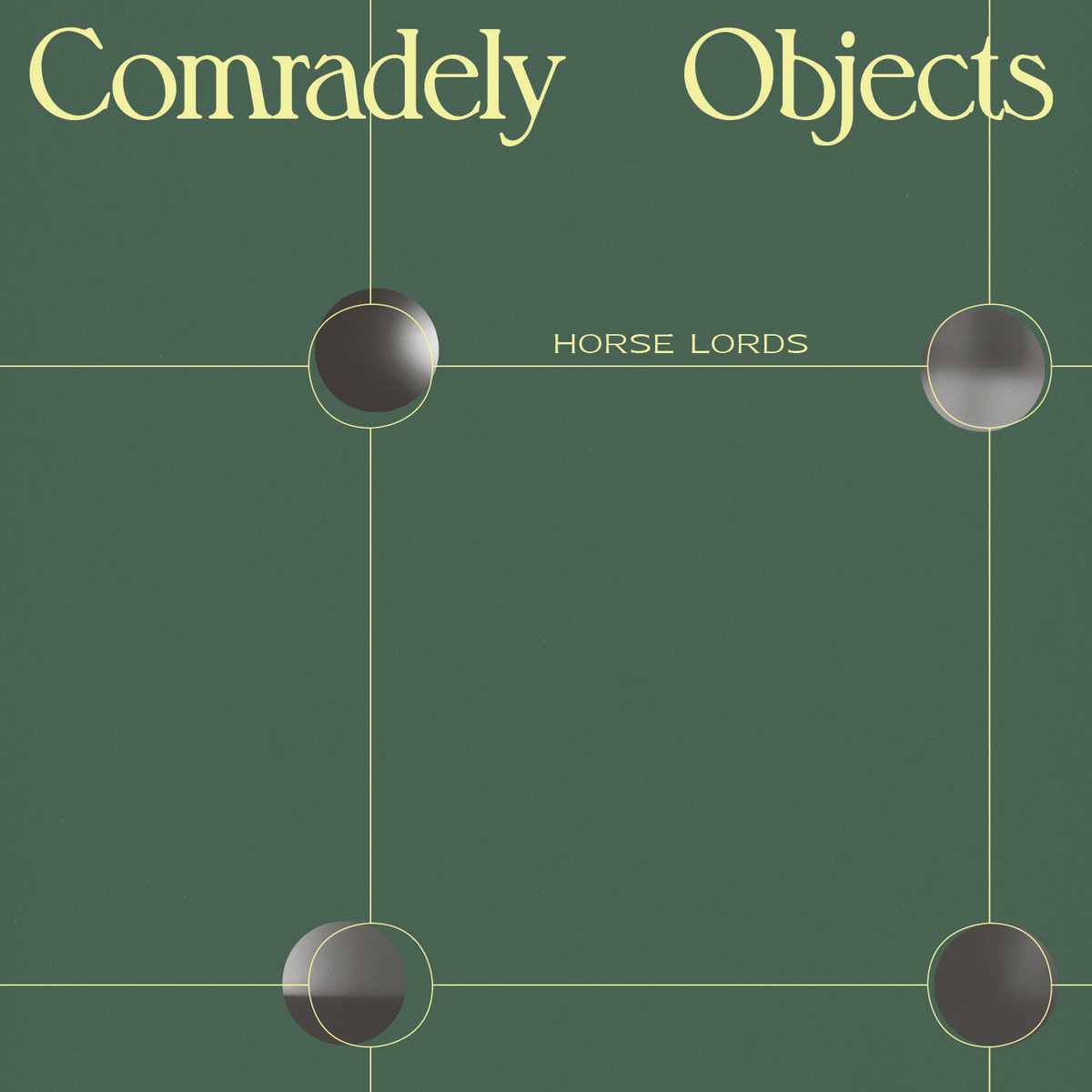

Tone Glow 087: Horse Lords

An interview with Horse Lords + our Writers Panel on Horse Lords' 'Comradely Objects' and elite gymnastics' 'snow flakes 2022'

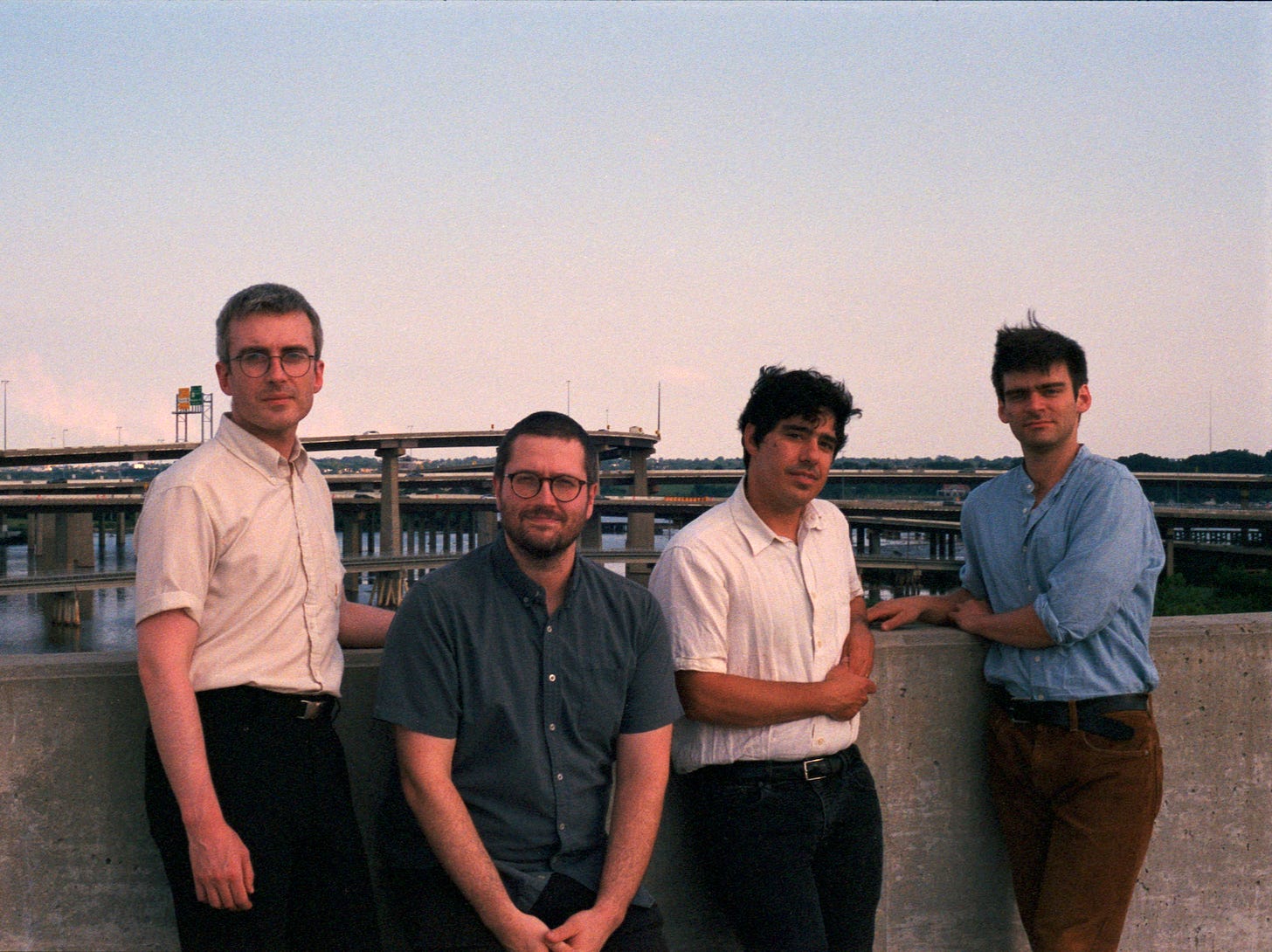

Horse Lords

Horse Lords is an experimental rock band that formed in Baltimore in 2010. Comprising Andrew Bernstein (saxophone), Max Eilbacher (bass/electronics), Owen Gardner (guitar), and Sam Haberman (drums), the ensemble makes pulsating music that employs ideas such as serialist and minimalist composition, just intonation, polyrhythmic patterning, and free jazz and improvisation. Their latest album, Comradely Objects, continues to explore the genre- and style-blending sound they’ve codified over the past decade and is out November 4 on RVNG Intl. Vanessa Ague spoke with Bernstein, Eilbacher, and Gardner over Zoom on October 17 about their shared language, what they’ve learned over the years of music and friendship, and why Horse Lords is always a part of their musical and personal life.

Vanessa Ague: Hi everyone!

Andrew Bernstein: Hello Vanessa!

Oh my gosh, wait, you have a Bang on a Can LOUD Weekend shirt on?

Andrew Bernstein: I do.

I have that shirt, we could have matched.

Andrew Bernstein: Oh well, next time.

Next time! Well, thank you all for being here.

Max Eilbacher: Of course, thanks for having us.

So, I just wanted to start out by asking how did you all meet each other?

Andrew Bernstein: Owen and I went to college together, and a not-very-large college in suburban Baltimore, Goucher College. Towards the end of our time at Goucher, we started getting involved in the music community of Baltimore and Max is a few years younger than us and grew up there. [We] met Max through music and started playing music together around then.

Max Eilbacher: Just more DIY concerts, playing shows together, playing improv together, and we had other groups together before there was Horse Lords.

Owen Gardner: We met Sam the same way a couple years after that.

Andrew Bernstein: Sam, the drummer, the fourth Horse Lord.

What did you love about playing together in those early days?

Owen Gardner: I was coming out of a pretty conservative musical environment, so it was very refreshing to play with people who were also interested in a variety of experimental musics, and not necessarily playing songs—blending improvising with experimental compositional strategies and playing with tuning, being open. Andrew and I workshopped just intonation together. It was exciting to play with people who were open to trying things out

Max Eilbacher: I guess for me it was an age thing, ’cause they were people who were closest to my age. It was like, these are peers, and it was interesting to play in a situation with people who hadn’t been playing improv for years, or had a very refined style or sense of practice; [it was] meeting people who were still formative and wanted to explore different things and were open to different methods of working.

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, likewise. “Fans” is the wrong word, but I really liked Owen’s playing and Max’s playing—seeing them play in other contexts with other bands. Even Owen and I, in college together… making new friends and playing music, I feel, were going hand in hand at that point. It’s exciting being young and making new friends.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, and sharing a common language and [speaking] it together.

Owen Gardner: And Bernie was actually a fan before he was a Horse Lord.

Really?

Owen Gardner: I think it was two shows before Bernie joined the band.

Andrew Bernstein: It’s true. The three of us, with other people, had a band together. That band dissolved, and then Owen and Max with Sam started this new band. And so I didn’t see the first Horse Lords show, I saw the second one and then was a part of the third one.

Nice. So that must have been really exciting, to get to join!

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, yeah, I insinuated myself into the mix.

Max Eilbacher: It was also so natural. I think one day it was like, “I think Bernie’s gonna play.” And it was like, “Oh yeah, of course.”

Owen Gardner: Yeah, he recognized everything we had been doing.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah.

Owen Gardner: It was all part of stuff we had already been working through. I see it as, to some extent, an extension of what we had been doing in this earlier band.

You mentioned you all have this common language that brings you together. How would you define that?

Max Eilbacher: I guess it started out with the want to experiment, like experimental music and coming from that background. But then, especially for how Horse Lords exists, how to situate what we wanna do. What we decided to do was very different from what we had done in previous groups and from how other groups and acts operated within our scene and community, of being like, “Yes, we’re gonna do a rock band.” It was very novel. But because we all had experience with each other beforehand making more experimental music, I feel like the language is in there somewhere.

Owen Gardner: Yeah. I mean, Bernie and I have the shared language of just intonation, which is something closer to a natural language. I mean, it isn’t, but it’s more of a coded, specific, defined thing that you have to learn. We both have that. But I think in a larger sense, there’s a combination of a willingness to experiment in a free way, or playful way, but also a willingness to submit to various strict practice-based music.

Andrew Bernstein: I think that the shared language is almost like an ethos that we’re willing to trust each other, and maybe this is because even when we started the band we had known each other for a few years. We trusted each other enough to give each other ideas and to work for a long time to play something that was very difficult for us. I think we were okay musicians when we started, some maybe better than others, but being willing to try and improve… there were no slackers. And it was fun, especially coming from a noise scene, which is how I would generally characterize the community we were part of. It felt fun and a little bit different.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, thinking of practice and reflecting on it now, it’s very much that idea of “we’re gonna practice for a while before actually doing anything.” And it’s very different.

Owen Gardner: That was very unusual.

Andrew Bernstein: I think a lot of the time, especially in the early days, people were very impressed that we could stop together. So the bar was low.

I mean, I’m still impressed y’all can stop together, honestly.

Owen Gardner: We can’t always!

That leads me to a question I had for you, which is: How do your rehearsals work?

Owen Gardner: I guess it depends on the goal. Lately, they’ve had to be a lot more directed, like we’re either preparing for something, or a couple years ago we were writing this record. In the past, it was quite loose. Like maybe somebody had an idea, they would bring that in and we would workshop that. This was more… I actually couldn’t tell you how it was different, but it was more deliberate.

Andrew Bernstein: Well, in the past we had someone who would bring an idea, we would workshop it, and then we’d play it at a show next week, like a half-finished version of a piece, and see what works and then finish music that way. And we wrote this record during the pandemic, so there was no prospect of workshopping through live performance. So, some of the pieces we just didn’t finish until we recorded them half-finished, or maybe closer to three-quarters finished, and then figured out what the rest of the last 25% was in post-production.

Max Eilbacher: I’d say now rehearsals are very different than what they were. Before, we used to practice 2-4 days a week, and then now, ’cause we’re all in different places, we get together a few days before tour and run things.

Owen Gardner: Generally it’s a lot of drilling now.

Max Eilbacher: Which we did in the past, but it’s a different type. It was drilling to learn. Even for this record, there’s a certain type of running the same section over and over and over again. Whereas now, when we get together, it’s some of that, but we’re in a rehearsal room and there’s a set goal, where before we used to practice in Andrew’s basement for years. So, it’s very much the rehearsal space. You might rehearse for a tour, but then also split it up with workshopping something new or running a part.

Andrew Bernstein: And then we’d come upstairs and hang out with my wife and eat dinner and then play more. But yeah, recently in the last year or so, we had somebody fill in on drums for the last couple tours just ’cause Sam hadn’t been able to come over from the US. So, a lot of the rehearsals were getting them up to speed and figuring out how it feels with somebody else, how somebody else plays these parts. And Sam is coming over for this upcoming tour, which is in a couple weeks.

That’s exciting!

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, I’m looking forward to playing with him again and we’re going to be getting some of the new material ready for live performance. Whereas in the last year, or really only on the last tour, did we play one of the pieces. So, I’m looking forward to more generative and creative rehearsals, both figuring out how we’re gonna do these pieces live, ’cause like I said, we haven’t really played any of it live.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah it’s interesting you say that because looking back now, the past year or so of rehearsals has been very much looking at material we’ve all been playing—for sometimes over 10 years together—and then learning to adapt it to someone new and have these super small or large things you change to someone’s playing style, someone’s energy. So, practicing has been learning how to adapt and decoding what is muscle memory and what is an actual dynamic part.

Andrew Bernstein: I think sometimes it’s been helpful formalizing some of the things that we just developed over years and hundreds of concerts. Like yeah, this is how we do it, we proudly do it the same number of times, but we’ve never counted it. Everybody just feels it and knows “this is the time,” but then somebody new comes in that doesn’t have the history.

Owen Gardner: It forced us to solve some problems, too. There’s just bits where we didn’t really bother to completely solidify some section, but we’ve been playing it enough that we can just fudge it together. But also, a new person can’t do that, or they don’t want to, like, they want it to be a finished piece of music. So that’s been helpful, too, learning more about our music by having to explain it to other people.

And maybe even to journalists, too.

Owen Gardner: Maybe.

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, but you’re not asking, so like, “How many times do you play this?” That would be a fun interview, but I don’t think that’s this interview.

Max Eilbacher: Like where’s the hi-hat shimmer in the second half?

I’d be like, “I need a score right now” and have it open and just go page by page. So, you guys have been touching on this intuition that you have together. How have you developed that over time with each other?

Owen Gardner: I mean, we have spent a lot of time practicing. We’ve been playing together for 12 years this year. And, we started when we were pretty young, so to some extent I think our brains have developed together.

Andrew Bernstein: And even outside of the band we spend a lot of time together ’cause we’re close friends—lots of time immersed in the same world, immersed in the same music, and many conversations about music. So, as far as this shared language we were talking about, I think some of it just develops over that time, talking about ideas and then wanting to respond or pursue similar aims.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah that’s interesting—an intuition, because it’s so intuitive I don’t even think about it as an intuition. I personally don’t play with any other groups in a context that requires this musicality and musicianship. So it’s like, this is one of those languages that has led to disappear or something—a very arcane [language] not spoken by many. So, when we are together it’s very sharp and it can’t be, for me, placed anywhere else. I can’t apply this musicianship to other groups, so when I’m practicing, rehearsing, or playing, it’s very much focused to this and only Horse Lords and not a larger picture of a musical language. I’m not trying to communicate in the same way with other people. So when I have time with these three people, it’s very much hyper-focused and we all have a common goal. We’re all in it for the same reasons, too, which I think is really important. At least from what I can tell, we all have the same end goals and desires and we wanna derive the same joys out of what we do together. I think that’s really important to keeping that language sharp and vocal.

How do you think playing together and being in Horse Lords has made each of you a better musician?

Andrew Bernstein: Like I was saying in the early days, this committing to practice and not just like, “I’m gonna go home and I’m gonna run scales,” but wanting to learn, especially with rhythmic things, trying to do rhythmic hocketing parts or learning to feel certain polyrhythms so that we could play them as a band. I feel like it has given me a reason to practice and play with other great musicians—I don’t wanna fall behind or something. But that’s not really the right attitude, like “oh you better keep up.” No one’s getting on me about practicing, I don’t think ever, and it’s not that competitive spirit, but it makes me want to practice, to show them new cool things that I can do.

Max Eilbacher: And also in the way we work within sound. I think we can all do certain things in our solo practice, but what works well in Horse Lords is we’re taking ideas that we’re interested in for our solo practices, and what we’re interested in about composition, and we’re making it work as a whole. We’re making it a four piece to something that maybe only MIDI sequencing or a computer music patch can do. So, being sharp enough to do that is the only way you get these ideas across to communicate this language. Practicing has become part of that. I don’t come from a musical background, so just being around people who could break things down in layman’s terms and were patient enough to count things through and not just feeling like, “Oh, that’s a world of musicality I want nothing to do with.” That, and embracing both radical ideas and understanding you need a shared lexicon of musicality to express something. That’s really important, to be exposed to that at an early age and not just be bored by the conservatory or just totally throw it out the window.

Owen Gardner: It helped me a lot. As Andrew was saying earlier—and it’s still true to a great extent—we were writing parts that were really at the edge of our abilities and, in some cases early on, beyond our abilities. And we’ve tried to keep that up. I mean, many of the songs on the current record are still very hard for me to play, and some of the old songs are still hard for me to play. But I’m much better. I can do things now that I definitely thought were basically impossible nearly 10 years ago. So, committing to constantly trying to expand both what I can do physically, but also psychologically, or cognitively, or perceptually, and exploring the limits of what is possible for us, and what’s comprehensible in these thresholds, I think are interesting areas to explore. In every case, hearing somebody who can barely do what they’re doing manage to do it is cool. And then also hearing something that barely makes sense but somehow does, or maybe it doesn’t, but feels like it does, or something appears to be something it isn’t.

Andrew Bernstein: I think there’s a tension. There’s this tension you have of being on the edge, and I think that blends an excitement for myself and also for the listener.

Owen Gardner: Yeah. And the music all contains an instability. Most of the pieces are written in such a way that you can’t just zone out and play it and think about something else. You really have to be engaged with what’s happening. So I feel like that keeps it interesting and maintains this tension, ’cause there’s always a moment in a song where none of us can be 100% sure that we’re going to land this, even if we have done it 100% of the time.

Max Eilbacher: I really like the idea of the limit. The idea of the limit is that it moves, and in doing this together, we move it as a group. I think for me, when I get to the limit, I can zone out at parts. And then I realize that the limit has moved, and the limit is self-imposed, and that playing and practicing improves that.

What does it feel like when you play live?

Owen Gardner: It can be very exciting. I feel like I can get into a flow state or something. Definitely early on we were very interested in altered states of consciousness, trance, and things like this, not so much drugs, and trying to explore these ways to cement this in ourselves and in the audience. We’re trying to build a relationship where there is some psychological feedback. I feel, for my own part, I need to be engaged with the music in a certain way to convey that energetically to an audience. So, sometimes I find it actually very frustrating when I feel like I am just playing a song, or like I can’t hear myself, or can’t hear something I need to hear. Then it feels more like just playing a regular gig or something. But then, there are many times where I feel more like what somebody meditating maybe does. I definitely feel like I do not feel like I do in the rest of my life. I don’t know if you guys know what I’m talking about.

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah exactly, I don’t have a lot to add in that regard ’cause you hit it on the head. Sometimes it just feels like going through the motions, and I don’t know what it is when the sound is just right and the vibe is just right and we play just right and maybe my reed is just in the right spot, there’s so many variables. But when it hits, it really hits.

Max Eilbacher: On this last tour, someone approached me and they were like, “You look so bored onstage, do you just hate doing this?” And it was really shocking and off-putting ’cause it’s like, “No, actually, I love doing this, and I’m in my zone.”

Owen Gardner: In another world.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah. But, it really got me thinking more about, not the musicality, but presentation and what it means to present something and play live. And if the sound isn’t speaking to counter this person’s perspective of me being bored and hating life onstage at this concert, I don’t know what that person was grasping for other than the sonics. Like, really, you get to ask me that? Maybe I’m projecting.

Wow, that’s fascinating. That’s the last thing I would have thought somebody would say to you after a show.

Owen Gardner: It’s true, I feel like you’re the most engaged in an obvious way, usually.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, I was pretty shocked. I thought they were messing with me, but it was a serious question. But, I agree though. I reach a state where I can visit places in thought patterns and memories or ways of thinking that I can only reach through doing this with Horse Lords. For me, I’ll reach a place where I’m having a thought, or it’s similar to meditation, but only when I’m there I can be like, “Oh yeah, I’m at this place, I only come here when I’m playing live with Horse Lords and this is a place I visit often.”

Owen Gardner: Yeah, and the music is also constructed in such a way that you’re part of an organism. No part is sufficient on its own, so you’re always depending on everyone else. So there is an egolessness built into the structure of the music.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, I think that’s important to think about in terms of how we differ from a practice of math rock or something. Because it’s not someone nailing a hot lick and then transitioning into something else. Things overlap and are patterned and mosaiced in a way where I like to think we avoid the phallic-ness of math rock.

Owen Gardner: Yeah.

Yeah, that’s a really, really interesting point. ’Cause I hear that a lot when I’m listening to your music, and I think that’s what draws us to it—that it does have this organic flow.

Max Eilbacher: Mmhmm.

So for each of you, what was your musical experience before you joined Horse Lords, or before you all met?

Andrew Bernstein: Well, I grew up playing the clarinet as a child in a school concert band. And then, at a certain point, I wanted to play music with friends, I wanted to play punk rock music. I started playing the guitar and played music with friends, and in retrospect, fell into a somewhat free-thinking group of friends—musically free thinking—and would improvise a lot and be playing songs. We’d just jam a lot in high school. And then, at a certain point, I became less interested in playing the guitar. I still play some just for fun at home, but I then got into more experimental music by way of heavy music, being into hardcore and grindcore and getting into noise music through that and free jazz from there. And then I started incorporating the clarinet back into music I was making. And then, a friend had a saxophone that he didn’t play anymore, and it was like, “Well, clarinet and saxophone are close enough, and saxophone is louder.” (laughs).

Max Eilbacher: ’Cause you were playing this in a metal band or in a grindcore band?

Andrew Bernstein: No. Well, a little bit of clarinet. There was always humor in some of these bands, and so the clarinet was used for comic effect. But mostly in college, and before I played saxophone in Teeth Mountain, I played some clarinet. And via playing music with friends, we would practice at my house, so people left drums, and I picked up the drums and other instruments that way. Then I studied electronic music in college and connected with Owen. It was actually a chance meeting in the electronic music studio at our college that brought me into the fold of this previous band Teeth Mountain. And the rest is history, getting deeper into contemporary music and experimental music. That’s my life story.

Owen Gardner: My dad is a musician and he exclusively plays old-time and bluegrass music, and I guess maybe some country-Western stuff. So, I grew up with a lot of music around, but mostly that. Although, he had a very expansive record collection. He and John Fahey were friends when they were teenagers and they grew up together, and he had a similar, very expansive idea of what a person ought to be and what music ought to be and the variety of music a person ought to be taking in. At home, he had weird jazz records and classical, all sorts of stuff. He introduced me to Beefheart and Frank Zappa, which were very important to me when I was younger. I played some with him—square dances and stuff were my earliest performances.

Where I grew up, there was not much weird music happening, but I played in a rock band—maybe an indie rock band—and was privately interested in more experimental stuff and international music. That was just a private interest, pretty much, until I went to college. I was also in more of a rock band there, but then eventually met Andrew and some other people, started Teeth Mountain, and then shortly thereafter got involved with the free improv scene in Baltimore and the more general experimental music scene.

And in college, I also got increasingly interested in studying music. I got interested in serial composition—not so much the music but the rigor and the completeness—that was very intriguing to me. And, of course, early minimalism. That’s how I started pursuing or attaining music in a more serious way, or in a serious way at all. After college, I basically just continued working on these things. In Baltimore, you didn’t need to work a whole lot, so I was mainly focused on developing these ideas and working with Horse Lords and with other groups, other people, and figuring out ways to reconcile that with the music I grew up with, which has been a constant, interesting challenge.

Yeah, they seem part of all sorts of different traditions.

Owen Gardner: Yeah, I think the throughline is just that I listen to them all. I think there are also some other connections, less obvious connections, that I can draw. Even if they’re just personal, they always lead somewhere.

What are those connections for you?

Owen Gardner: It would be hard to talk about, both ’cause I think it’s things that I’ve continued having as a private musical life to some extent—so there are a lot of things I haven’t really articulated much—and other things I could articulate but maybe would be boring answers. Broadly speaking, I’m interested in these harmonically rich timbres, microtonality, disorienting rhythmic or timbral effects, or things like this that very much show up in Horse Lords, which I think are shared across these disciplines. That’s probably the most succinct answer I could give.

Yeah, that totally makes sense to me.

Max Eilbacher: And for me, same thing, I grew up playing in bands, playing in punk bands, playing guitar. But then being in Baltimore, you have easy access to improv and noise, so from a young age I was going to a lot of far-out stuff and so I’ve always been interested in that. I think as time goes on I realize I’m less interested in music and more interested in sound. So where does that fit into the practice? I think it’s a slow realization that music is a subset of sound.

What do you think the difference between music and sound is?

Max Eilbacher: I’d say, from my very personal experience, it’s presentation. Like, Horse Lords next month, we’re presenting music. But in a club in a few weeks, through a few speakers, I’m presenting some sound. And I could argue either/or, but for me, the shared collectiveness of it and the shared experience of having this family of 12 years—we work with sound but we present it in the context of music, we put out records, and we call it rock music, we call it experimental music, where I may only be interested in music because it is a way to share sound.

Andrew Bernstein: I mean, that’s the Cageian idea, right? Putting the frame around it, the act of listening is what makes it music. And I guess he called all sound music through that frame, but letting it be sound—it’s another strategy. I think we all share this interest in and fascination with sound and explore it through Horse Lords and our solo musics a lot. And just intonation is part and parcel of that, in working through sound and a tuning system that honors the material of sound.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, I really like the idea of sounding material. The materiality of sound to me is very important. I think that’s why, again a shared vision of timbre—we can approach material from an idea of sculpting or from an idea of writing tone rows. They’re the same thing, just different inroads.

Totally. I’m curious for each of you, what do you think just intonation gives you that might be different than a different tuning system?

Owen Gardner: Although it’s very inflexible, it’s also very adaptable in other ways because it’s both descriptive and… what’s the counter?

Andrew Bernstein: Prescriptive?

Owen Gardner: Yeah, I guess. It’s its own language. So, it’s just a different way of doing pitch space. And one that’s more broadly applicable than equal temperament, which has pretty much stuck with music, whereas just intonation is implicated in recognizing the words I’m saying, but also then that can be elaborated to something that’s recognizably musical, that could be transcribed for a trumpet or something. Not only can it articulate the continuity between sound and music, but it can be applied to a lot of different kinds of music more appropriately and with better fidelity than with equal temperament.

I’m very interested in a lot of traditional music, and a lot of that is not particularly well-served by equal temperament. I feel like I can get closer to, not the truth, but just to a more accurate representation. I would need to qualify that over the course of an hour to get a more accurate answer, but I’m satisfied with the short version. It does a lot, and that it’s continuous to timbre, and that it has implications for rhythm, too, and that it’s something that can be abstracted into just numbers. So, it can be anything. This is what I was saying about serialism—that curiosity led me to just intonation, also a much more suitable language for that kind of composition because it’s much more flexible. So, the results are more comprehensible and more appealing, and more direct. There’s a physical unity between pitch and rhythm, whereas it’s just number games with serialism.

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, I second all of that. Just intonation is more true to sound, I think, in the sense that it’s working with the overtone series that is present in periodic sound and all sound. There’s a physical dimension there that I haven’t been able to access through equal temperament, at least. And, just intonation is so wide a field. It means a lot of different things. It’s not one scale, necessarily. So, there’s a lot of people that are interested in arbitrary divisions of the octave. You have quarter tones, or you have ten tones to the octave, and maybe there’s advantages there in some ways, but it doesn’t have that unity between timbre and rhythm and pitch that really interests me.

Max Eilbacher: I didn’t even know the idea of what just intonation was until year one of Horse Lords. I always hated the idea of playing electronic music instruments with a keyboard, so it’s great to be like, you could escape the similar paradox, but here’s a bass that does that. So, it wasn’t until playing with Owen and Andrew more in-depth that I began to understand the systems and what we’re doing, why it’s important, why it’s good.

Owen Gardner: Right, because it breaks you out of conventional music grammar.

Andrew Bernstein: And something you said in an earlier conversation, Max, that I liked is that, especially in experimental music, in noise, and electronics, there’s a lot of focus on timbre, but just intonation appealed to me partially because it allowed for exploration of pitch and harmony in a way that felt like it had forward momentum, in a way, that working with equal temperament didn’t.

Owen Gardner: It’s true, I think that because of equal temperament, these traditional musical parameters are seen as dead ends, but they really don’t have to be. We focus on this tiny area of just intonation, which, theoretically, there's a limitless number of things you can do. Literally, it’s limitless.

Andrew Bernstein: I feel like it’s gotten me more interested in melody in a way that I wasn’t at all before getting deep into just intonation.

It’s amazing how a concept like just intonation can hold so much inside of it and just open up an entire world.

Owen Gardner: Totally. And I mean for many people, it’s like a religion. I don’t think any of us are particularly attached to the more metaphysical territory, but I think some people really feel that they’ve received the keys to unlocking the mysteries of the universe.

Max Eilbacher: A few ratios doctors don’t want you to know about… (laughter).

So we’ve talked about this a little bit, but I wanted to ask you all what have you learned from each other by playing with each other?

Max Eilbacher: Well, yeah, I wouldn’t know anything about music. I would know absolutely nothing about any musical grammar without playing Horse Lords.

I’m sure you’ve learned quite a bit!

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, a fair amount could always be improved. And when I go to my own solo practice, that’s greatly inflected by what I learn in Horse Lords. The exchange of ideas, of course, but even just the practicality of what I need to research or read on, or rabbit holes to follow now.

Andrew Bernstein: Owen introduced me to just intonation, microtonal music, in college, so I owe that debt to him. And, I feel like I’m still learning things all the time. I mean, Max sends me a supercollider patch just to share some sounds he’s working on, and we have that back and forth working on code together. And then, likewise, with Owen, some of Owen’s notation has inspired my own ideas and willingness to even try and write music down on paper. And with Sam, having Sam to write drum beats for—he has taught me about the rhythmic mind, like how one could play these things. Sometimes we’ll just give him something that we just wrote on paper, sequenced in the computer, like, “I don’t know if this is like something that makes sense for a human to play.” And sometimes it doesn’t make sense.

Max Eilbacher: But, sometimes, you gotta adjust it to make it just funky enough…

Andrew Bernstein: Exactly, yeah.

Owen Gardner: He’s good, I mean, he’s very disciplined, as you can hear. There have been many times where he’s started out saying, “I can’t play that,” and then we’re just like, “How about you just play it?” (laughter).

Max Eilbacher: How about we stand around here for a few hours every night with you? (laughs).

Owen Gardner: Yeah, we do a lot of this. There were things we couldn’t do at the beginning of rehearsal but we can at the end. I feel like I’ve learned a lot about discipline in this way. And like Andrew was saying, I’ve learned a lot, ’cause Sam actually plays his instrument in a more meaningful way than any of us do, or at least at the beginning that was true. So yeah, I’ve learned more about the same thing—how the drums work and orchestration. I’ve learned a lot about cooperation and trust and these things that one certainly isn’t called upon to do in their solo practice and that I was maybe not mature, or mentally healthy, or assertive enough, to work through in other past groups. I’ve learned just more about my own ideas by hearing them reflected in the playing of others. Hearing what doesn’t work, and what does, and how these things work with four people. I already said cooperation, but learning cooperation in a more concrete way.

Max Eilbacher: I think to amend that—sustainability too.

Owen Gardner: Yeah, for sure. We’ve kept it up for quite a while, and it’s not been a very rocky road, for the most part. But we’ve also been called upon to learn interpersonal skills to make that continue.

What do you think keeps drawing you all back to the Horse Lords project?

Max Eilbacher: For me, it’s never a question of drawing back, it’s just always constant. Even if we don’t play for months, I’m never thinking about it like, “Oh, it’s quiet.” It’s never something you have to come back to. It’s just always at the fore. It always has momentum.

Owen Gardner: There’s never really been a lull, even when we’re not releasing stuff, we’ve never really slowed down that much.

Max Eilbacher: Even if we’re not rehearsing or writing, we’re still exchanging kernels of ideas or still talking to each other. So, it’s never like, “Oh, time to fire up the ol’ Horse Lords again,” you know?

Andrew Bernstein: I think it’s been helpful that from the very start, it was kind of popular, even just in our little circle of friends. We played one of our early shows, and one of our friends who had a record label was like, “That was great, I wanna put out a record.” So, we’ve always gotten positive feedback, which, it’s nice when people give you compliments. It isn’t enough to sustain it certainly by itself, but it doesn’t hurt. And, now, there’s people who ask us to play, so it’s not like we have to go out beating down doors. We’d probably still want to do it, but it would probably be harder to do it, but now we can make enough money playing that we can fly Sam over to play this tour.

Owen Gardner: And we didn’t have to beg anybody to book these shows.

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, we didn’t have to beg anybody to book us. So, just the practical considerations—we don’t have to work quite as hard to keep that momentum going as we did at one point. But even when we did have to work harder to keep it going, when no one was asking us to play… Something I wanted to add to my concise life story is a band that the three of us played in, and Owen wasn’t in the band by this point, but Dan Deacon brought us on tour. I, with some of my other bandmates and Future Islands, were opening for Dan Deacon and playing in his large ensemble. This was like 2009/2010. And, I think this was one of my first professional touring experiences.

Some of these early tours gave us the bug a little bit, just how much fun it can be to travel and play music and how fulfilling it can be to share music with people in that way. And then when Horse Lords started, it was never a question—it was obvious, at least in my mind, that we should go on tour. And so we started just booking tours. And those years, it was a lot of work, but it was a lot of fun. I’d do a lot of the booking, and I would love sending out so many emails, and then you’d get emails back. I’m just sitting at home in my kitchen sending emails, and then a few months later, the band is on tour, and it’s just the immediacy of all that and also the community aspect of it, ’cause along with Owen and with Max I got involved in the community in Baltimore. I was hosting a lot of concerts, so I was meeting a lot of people that way. Being part of the local community in Baltimore, and then also the more expansive East Coast underground and American underground, was really important to me over the last decade.

How has it been leaving the US?

Max Eilbacher: Great.

Owen Gardner: Pretty good.

Max Eilbacher: Really amazing.

Owen Gardner: I mean, it was a weird time to leave, of course, but it made a lot of things easier in a way. Like, in the US nothing is happening, the world is stopped, so I might as well just restart.

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, we all moved over around summer of 2021, and so everybody had just been vaccinated, so we were able to see some of our friends before we left, but there were no events happening. And personally, I’m not in Berlin, so I feel like my experience of moving to Europe is still overwhelmingly positive, but I miss some of the community I was talking about.

Owen Gardner: It’s pretty different from our lives. Bernie really lives in Europe in a more meaningful way than we do, ’cause you live in an adorable Medieval old town. Which I really am jealous of.

Andrew Bernstein: My parents said it looks like Disneyland. I was like, “No, no. Disneyland looks like—”

Owen Gardner: Even older than Disneyland (laughter).

Andrew Bernstein: Yeah, even older.

Owen Gardner: Whereas Berlin might as well be an American city.

Max Eilbacher: Not that much.

Owen Gardner: It doesn’t feel like an American city but nothing is old. That’s all I mean.

People always say to me that Berlin is like if downtown New York was still cool, and I’m like, “Okay, maybe?”

Owen Gardner: I understand what they’re saying, for sure. But it’s also, I mean part of what’s exciting to me is it really does have its own flavor and its own history.

Max Eilbacher: Mmhmm.

Owen Gardner: It’s also had its own instances of culture and, obviously, huge upheavals and history, that I mostly don’t really know much about. So, it’s been really cool to just explore a new place. And, in many crucial ways, it doesn’t feel like an American city—many things that I really find quite depressing about the US, they’re not here. It’s just a lot of public space, a lot of public life. It’s really nice to be around, it’s a human-scale city. Really active. I think the cultural life is maybe where the analogy with New York comes from.

Probably. Do you have anything you’d like to add, Max?

Max Eilbacher: No, I agree with Owen. It’s what I liked about Baltimore in my mid-late 20s but on a much more sustainable level. I mean in terms of cultural stuff.

That’s great. Congrats on making the move!

Owen Gardner: Thank you!

Yeah, it’s big!

Owen Gardner: How’s New York?

I mean, “It’s back,” that’s what they say. It’s interesting because I think New York has gone through a lot of change during the pandemic, there’s even a new mayor who has a lot of different policies, there’s the constant waves of COVID—because it’s such a dense city, whenever one person gets COVID, everybody gets it. So, still dealing with that, but it’s been nice having more people feel like they can play here again, venues popping up. I mean, I saw Andrew at Shift.

Andrew Bernstein: It was nice to meet you briefly there.

Yeah it was! It was great because I was scared a place like Shift would never exist again in New York and it’s been nice to see some smaller venues come back and be able to put on shows. But, I don’t know, it’s gone through a lot of change and I don’t know how it’ll end up. Every day is an adventure, a little bit. You never know what’ll happen.

Owen Gardner: Right, and Berlin also does suffer from some of the same problems as New York, where one does have to worry about the future. It’s also changing very rapidly in a totally unsustainable way.

Yeah, it’s afflicting every city everywhere.

Owen Gardner: Definitely.

Max Eilbacher: Yeah, you can’t escape it right now.

So, my last question is: What are you all looking forward to?

Owen Gardner: We got some funding to do a project with Arnold Dreyblatt, who’s a composer we’ve admired for a long time. He’s also admired us for a long time. He lives in Berlin, so I don’t even know who originally proposed it, but we’ve been talking about working together a while. And that…

Max Eilbacher: Will happen. We got an email today about presenting it live, and we don’t know what it is, sometime in the future.

That’s so exciting.

Owen Gardner: It’s just an idea right now, but it’s an idea that we have made a commitment to see through.

Andrew Bernstein: And what, two weeks from tomorrow, we start rehearsing for this tour?

Owen Gardner: That’s true, I’m looking forward to going on tour.

Andrew Bernstein: I’m looking forward to that. That’s the most immediate anticipation.

It’ll be really exciting to try to play all this material live.

Andrew Bernstein: Yes.

Owen Gardner: Exciting, among other things (laughter).

Horse Lords’ Comradely Objects is out November 4th on RVNG Intl. Horse Lords’ tour dates can be viewed at their website.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Horse Lords - Comradely Objects (RVNG Intl., 2022)

Press Release info: Horse Lords return with Comradely Objects, an alloy of erudite influences and approaches given frenetic gravity in pursuit of a united musical and political vision. The band’s fifth album doesn’t document a new utopia, so much as limn a thrilling portrait of revolution underway.

Comradely Objects adheres to the essential instrumental sound documented on the previous four albums and four mixtapes by the quartet of Andrew Bernstein (saxophone, percussion, electronics), Max Eilbacher (bass, electronics), Owen Gardner (guitar, electronics), and Sam Haberman (drums). But the album refocuses that sound, pulling the disparate strands of the band’s restless musical purview tightly around propulsive, rhythmic grids. Comradely Objects ripples, drones, chugs, and soars with a new abandon and steely control.

Purchase Comradely Objects at RVNG Intl.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: When composer and critic Kyle Gann wrote about the 1990s post-minimalism movement “totalism” in 1997, he described it with a series of contrasts: sensuous but complex, visceral but sophisticated, containing both the immediacy of minimalism’s spectacle and the rewarding depth of serialism’s meticulous compositional strategies. Reducing music to such simple qualities reveals an important reality: all sounds we encounter are beholden to the emotions and ideas we readily attribute to them.

This is why I find Horse Lords, who are very clearly in this lineage of avant-garde music, primarily interesting. Their music marches forward in grid-like patterns, forever careful to telegraph the austerity of their enterprise. This stuffiness is essential, as it forces interesting considerations for the way particular sonics and rhythms—and our concomitant reactions to them—can overlap or be separated by a very thin line. A track like “Zero Degree Machine,” for example, is too academic to be math rock—a genre that’s at its best when taking the piss, really—and what I really hear is traces of Bikutsi and Turkish psych rock. Then there’s the multifaceted drone on “Law of Movement,” which is accompanied by instrumentation that moves in and out of different modes—one could consider it a hypnotic raga at one point and a motorik-based jam at another.

As I often feel about experimental music from white Americans who look to the rhythmic structures of non-American musics, Comradely Objects revels in its relative soullessness. This isn’t a value judgment, but a case for the thrill in seeing such a clear exchange of musical ideas. This occurs with all art, of course, but a record that has this notion at the fore is rare and deeply pleasurable. The title, which the band derived from Christina Kiaer’s Imagine No Possessions (2005), refers to the Russian constructivists’ desire for utilitarian objects that promoted egalitarian ideals. Links between this and Horse Lords’ music feel tenuous, but I do think there’s something to be said for a specific passage in the book, which relays scholar Nikolay Punin’s interest in the spiral as a form of movement from past to socialist future. The following excerpt from a 1920 essay could double as a review of Horse Lords’ new record, and grants a new lens to view their muscular, methodical, and mesmerizing music:

The form wants to overcome material and the force of gravity; the force of resistance is great and massive; flexing its muscles, the form searches for the way out along the most resilient and dynamic lines that the world knows—spirals. They are full of movement, striving, speed and they are as taut as creative will and an arm-muscle strained with holding a hammer.

[6]

Gil Sansón: There's a studiousness to Horse Lords that rubs me the wrong way. They’re the sort of “let’s come out with a set of influences—the right set of influences—and write a repertory” artists who used to work at indie record stores and look at you derisively when you asked if they had the new X or Y. I personally dig many of these influences: the krautrock and the Discipline-era King Crimson, the salutes to Harry Partch, the African polyrhythms, and so on. On paper it’s all legit, and maybe that’s my problem—everything sounds calculated. Perhaps it’s me who has a problem with how self-conscious rock music has become, with so much historical weight attached to each drum beat, fill, and power chord—this language has been completely codified. Should I complain when music sounds fine and the listening experience is memorable? Probably not. I should be grateful; bands finding progressive ways to rock out are needed. I just wish they weren’t as meticulous and snobbish as Horse Lords. Comradely Objects is still a lot of fun to listen to, so my ambivalence ends up subsiding, at least while the music is playing.

[7]

Alex Mayle: Every person I know who’s even slightly into modern experimental rock raves about Horse Lords, and they live up to the hype on Comradely Objects. Consisting of motorik beats droned out with free-jazz freakouts, this is the Boston band at the top of their game. Sam Haberman’s drumming is the obvious highlight, bearing a strong gravitational pull that brings everyone together. At varying points on the album he’s in a black hole pair with a different band member, the two dancing with each other to create waves of hypnotic drone rock. The most impressive part of Comradely Objects, however, is how short each piece is. “Rundling” is barely longer than three minutes but by its saxophone takes over, I feel like I’ve been in a trance for twice the length. The resultant feeling is time being stretched to accommodate the near constant movement in every song. I think my brain physically has to take more time to process everything they’re doing—it’s an incredible feeling.

[8]

Sunik Kim: As demonstrated by Comradely Objects, there is a fundamental contradiction between the metronomic freeway-tick of krautrock and the spiraling start-stop of mathier guitar approaches that can only be resolved via the soupy middle ground of a kind of post-minimalism. The latter approach is often delivered with a wink: it’s well aware of the inherent, visceral pleasure in tipping over the first domino or studying the inner workings of a watch, and the minimalistic meshing and unfolding of intertwined melodic gestures moves with that same often irresistible logic. Unfortunately, there is a very familiar, almost saccharine, scent to this approach, like a popular cheat code made obsolete by a patch (in this case, the progress of musical history). No matter how “elevated” or underground-ed the context, this kind of extremely legible phasing and interlocking approach is, more than many others, hard to re-envision or push forward in a truly radical way. To that end, the sound and feeling of this album reminded me, bizarrely and unexpectedly, of early 2010s indie/art-pop in its tentative exploration of clever polyrhythms, etc.

As for the broader compositional ingredients like just intonation and hocketing—I respect their inclusion, but they don’t feel wholly integrated into the being of the music itself, remaining sprinklings rather than foundation; “Plain Hunt On Four” is likely one of the most tedious tracks on here, and it is also the most technically complex, requiring several months of rehearsal. More than anything, especially with the directly revolutionary framing in mind, Comradely Objects feels incredibly safe—neatly caught between an ostensibly off-putting concert-hall “seriousness” and a fuck-it basement show approach, with the end result that it remains tepid and tentative rather than committed all the way in one direction or the other, with all of the risks, flaws and benefits implied.

[4]

Vincent Jenewein: In the previous issue, I complained about the unfocused, grab-bag nature of much contemporary improvisatory experimental music. Luckily, Comradely Objects manages to avoid such pitfalls. Despite its free-improv leanings it comes with a strong sense of cohesion. The Horse Lords appear to have taken a page out of The Necks’ book of mixing loose-ish structures with tight rhythms and continuous motifs. Despite radiating with manic jam energy, it commits to the teleology of the groove, maintaining a tracky, locked-in-the-groove feel somewhat reminiscent of Ricardo Villalobos’ extended, polyrhythmic brand of minimal house. The songs here are given enough room to adventure and develop in unexpected directions, while also being fortified with enough structural consistency to hold together a multitude of scales, rhythms and timbres. Channeled through the records’ machinery, the players’ ensemble of geeky scales and polyrhythms becomes just plain fun, a radiating psychedelic picture made up of gorgeous timbres and snake-charming grooves. No one ever said that being a comrade would be easy, but discipline sure can make for a good time.

[8]

[N/A]

Average: [6.25]

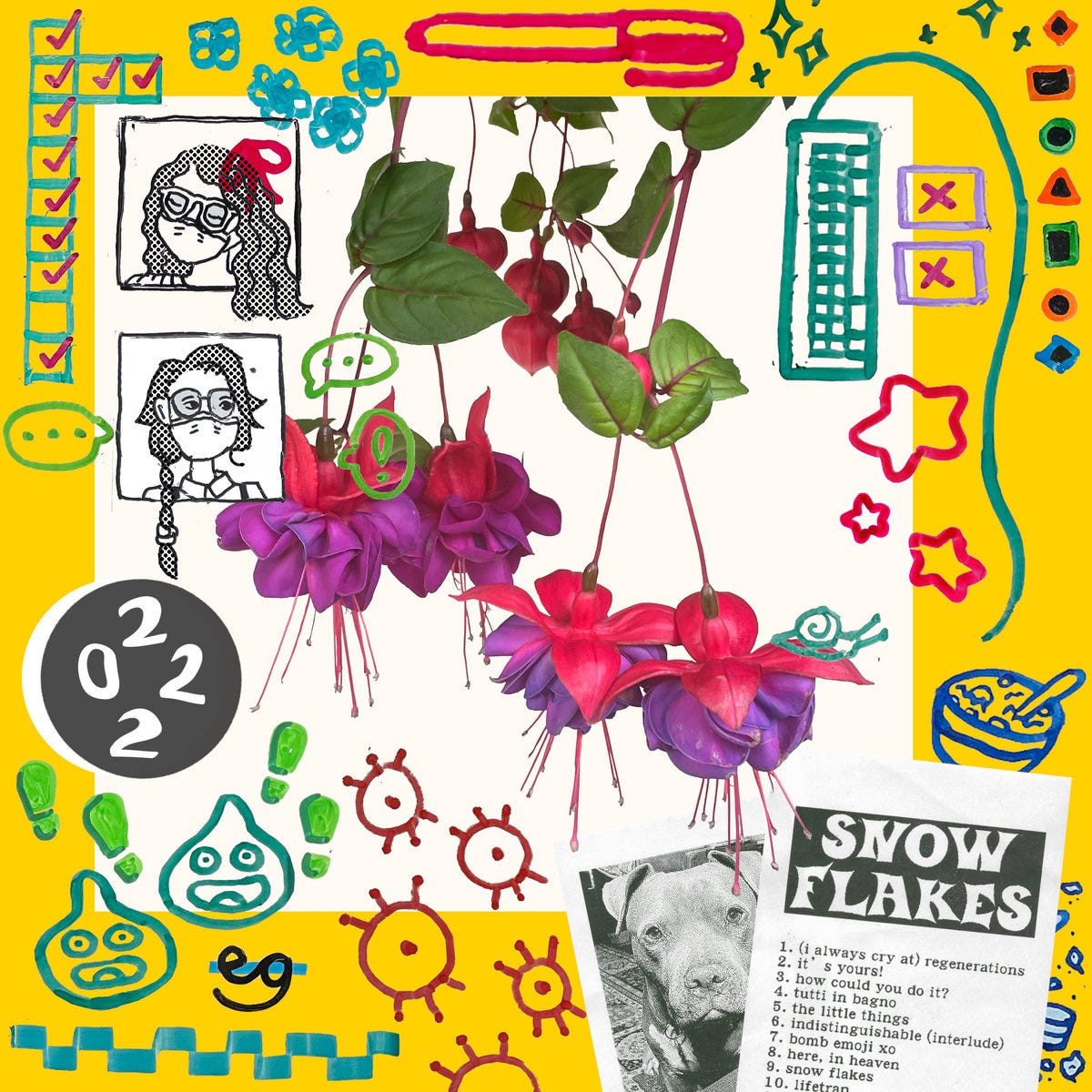

elite gymnastics - snow flakes 2022 (self-released, 2022)

Press Release info: the first album by elite gymnastics. created by jaime brooks and viri char with help from conrad tao and chloe hotline during 2020-2022.

Purchase snow flakes 2022 at Bandcamp.

Zhenzhen Yu: Intimacy characterizes default genders and elite gymnastics: Jaime Brooks delivers lyrics like she’s just thinking out loud to a friend (“Hey, I think I really like you… Wait, I think you’re really cool”), the timestamp emblazoned on each album title gives the feeling we’re checking in on her through the years (2013… 2014… 2020), and each indietronica-warm track feels cozy, intimately crafted if not too complex. But there’s something dispiritingly threadbare about snow flakes 2022’s entry into the Brooks canon. Compare two drum ‘n’ bass-driven emoji-themed songs from across the span of three years: the dark, out-of-breath narration of main pop girl 2019’s “heart emoji xo” rings taut and fragile, but the indistinct vocals of 2022’s “bomb emoji xo” fight puzzling hyperpop notes which fight the hook of a half-hearted “girrrrrrrrl…”. snow flakes 2022 drifts and wends and thinks out loud without a point, replacing fragility with thin, pieced-together afterthought.

[4]

Maxie Younger: snow flakes 2022 was probably always going to let me down; there was nowhere else for my relationship with Jaime Brooks’ music to go. main pop girl 2019, one of my favorite ever albums, released at the exact moment in which it could become a foundational text for me; but now, after the onset of COVID, I have a different job, a different life, and far less interest in exploring new variations on Brooks’s trademark breakbeat-soaked euphoria. Even with that in mind, snow flakes’ take on the style feels curiously anodyne and sluggish at its worst (opener “(i always cry at) regenerations,” unfortunately), trudging through globs of wistful, syrupy harmonic fluff with little in the way of compelling hooks or melodies to anchor them to solid ground. It’s not that anything here needs to be grounded, exactly—that same weightlessness has been a consistent virtue on Brooks’s other projects—but there’s a lack of energy to the proceedings that leaves snow flakes spinning its wheels in moments that should be easy, triumphant slam dunks (“regenerations”’s hard right into jittery chaos at its close reads less as a cathartic culmination and more as a last-minute kitchen-sink shrug of frenetic indifference).

The positives: Brooks, alongside new bandmate Viri Char, is as sharp and poetic a lyricist as she’s ever been, tweaking and expanding upon elite gymnastics’s old tracks to weave lush, lived-in tapestries and scenarios overflowing with detail, sentiment, and poignancy. I particularly like a quatrain from “it’s yours!,” updated from “minneapolis belongs to you,” that, honest to god, is an almost exact daydream/nightmare I’ve had about my own death:

cuz when i’m dead they will toast my life/

at my friends’ shitty DJ nights/

no one will hear their speeches clearly/

they’ll all just think it’s someone’s birthday.

Even though that same lyrical specificity leads to a few clangs, it’s the most invigorating aspect of this album, and made my relistens far more enjoyable than they would have been otherwise. This is a project that, if not explicitly for fans, is certainly aimed at scholars: those with the love and inclination to pick through these tracks to find the bits and pieces from Brooks’s earlier works they recontextualize. Endless renewal and self-interpolation has, of course, always been a part of Brooks’s music, but snow flakes 2022 is the first time that it’s started to feel so insular as to be actively alienating. The album functions more as a scrapbook of cherished ideas—good to flip through and reminisce upon—than as a collection of actual songs. Sadly, I’m not quite enough of a devotee to Brooks or to elite gymnastics’s legacy to get much out of that

[5]

Gil Sansón: Expectations are toyed with right from the jump, as the most banal and exquisite pop music tropes are displayed with gusto. It’s clear: this album is the mark of an artist. As snow flakes 2022 progresses, modern pop clichés—insufferably tired as they are—become recontextualized, becoming ingredients in elite gymnastics’ sonic concoction, jumping from pop to drum ‘n’ bass to dreamy indie rock. Occasionally Brooks wields an urgency through bubblegum sounds, like on “bomb emoji xo,” which directly quotes side two of Abbey Road. The album gets more interesting around midway through, as the music becomes more reflective and engaging. The vocal pitch-shifting and harmonized melodies blur gender borders beautifully, and this aspect of the record seems essential even if it feels understated—there’s a certain coyness about it. Overall, the music can be a tad too close to standard modern pop for my liking—even as I know there’s a critical distance and conceptual framework revealing serious artistry—but I still find the music to have content and substance; this is clearly not your run-of-the-mill pop fodder.

[7]

H.D. Angel: As someone too young to have really experienced “the blog era,” I've always been fascinated by it in rearview. There’s a sense of possibility in art and music from the period that feels unique to its historical moment: young people with new access to file sharing and new abilities to organize around their interests invented a million aesthetic tidepools, sampling and re-contextualizing their interests into new genres and affiliations. Tumblr dynamics still ripple through new creative networks online, but those specific tidepools—chillwave, cloud rap, TinyMixTapes-core(?), whatever—feel like relics of specific eras of the internet, their inventiveness settled into cliché. This is what I think about listening to old elite gymnastics songs. When I hear their washed-out sense of scale, wide-eyed samples, and early-’10s indie affect, I’m drawn in by those weird, idiosyncratic choices, by how inspired and ”unaffiliated” they must have felt at the time to fans—and can still feel now, if I meet them on their own terms.

snow flakes 2022, elite gymnastics’ debut album after over a decade of on-and-off activity and lineup changes, sounds more like Jaime Brooks’ recent communal, iterative work as Default Genders than anything released under the EG moniker. But it features multiple reworked songs from the band's early-’10s heyday, inviting comparisons between then and now. The songs fit like old sweaters, given new shape after years of change—and sometimes handed over, like on the Conrad Tao-assisted “omamori piano fantasy” and Chloe Hotline’s “Chloe 4-ever,” to someone with fresh eyes for how they might look and feel. The meticulous, single-minded personality of Brooks’ music has always been in conversation with her rebukes of the music industry and what it does to people, and any skepticism of her ideas—“if you're so smart, then why aren't you rich?”—is only answered with further devotion to craft. On “snow flakes,” as Brooks lists some of her formative musical diet (DJ Sprinkles, Chromatics, Xiu Xiu, etc.) and remembers a difficult time in her life when “sidechain compression sincerely was the most important thing in all of existence,” it’s hard not to think about all the structural obstacles that keep music lovers from building lives around music, making it harder for everyone to enjoy its potential to connect, support and enrich us.

There are so many moments on snow flakes 2022 that glimmer with this kind of lived-in intention. “how could you do it,” a remake of 2011’s “So Close To Paradise,” almost taunts the listener with its exuberant Meat Puppets skronk, as if poking at the boundaries of taste cycles. The beating heart of the music is Jaime Brooks’ voice, a vulnerable AutoTuned quiver that feels young and old all at once. The way she exhales the “when I’m dead” refrain on “it’s yours,” a remake of “Minneapolis Belongs To You,” is hard to locate emotionally: is it hopeful about the future, or resigned? How have those feelings changed since the song was first written years ago? I’m left to sit with these interpretations, turning them over in my head as I revisit different tracks. When I listen retrospectively to music from the era elite gymnastics came up in, I often wonder how my own experience in and around different art scenes, both online and IRL, will look in ten years. Will people cringe at them? Will I cringe at them? Will I regret the choices I made, ideas I bought into, and people I trusted? snow flakes 2022 makes the case that all of these thorny, unanswerable questions are part of growing as a person, and that the music we care about grows with us.

[8]

[6]

Average: [6.00]

Thank you for reading the eighty-seventh issue of Tone Glow. Let’s get into that flow state.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.