Tone Glow 069: Terre Thaemlitz

An interview with Terre Thaemlitz + our writers panel on new albums from Dean Blunt, David Toop + Ryuichi Sakamoto, Jack Callahan & Asha Sheshadri, and Mark Vernon

Terre Thaemlitz

Terre Thaemlitz is a Japan-based producer, DJ, and cultural critic whose multimedia projects have involved numerous aliases—including DJ Sprinkles, Terre’s Neu Wuss Fusion, G.R.R.L., and Kami-Sakunobe House Explosion K-S.H.E—and various styles of music, from sound collage to deep house to drone. Her work combines a critical look at identity politics—including gender, sexuality, class, linguistics, ethnicity and race—with an ongoing analysis of the socio-economics of commercial media production. He is the founder and owner of Comatonse Recordings, which has recently released a career-spanning compilation of her work under the DJ Sprinkles moniker called Gayest Tits & Greyest Shits: 1998-2017, 12-Inches & One-Offs. Resident Advisor has a new documentary about Thaemlitz. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Thaemlitz on May 11th, 2021 to discuss his time in art school, the current Pride movement, her thoughts on community and visibility, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: You mentioned in our email exchange that you disliked or regretted the fact that you did a Red Bull Music Academy interview. Why?

Terre Thaemlitz: Every now and then you just get involved with something where people represent it one way and then the reality is that it’s something completely different. When they approached me to do a talk for Red Bull Music Academy and then do a DJ set, they were like—and of course all this was super corporately-fabricated—“Oh, it’s all about the music, man.” This sort of vibe. They were very quick, they were very organized. Before they sent the contracts, they were already booking flights and stuff. And then after everything was already in motion, they sent these contracts and they were crazy. It was like they were written by lawyers who had no idea about how music publishing works. [They were] the classic contracts that have the two words. I’ll never sign anything that contains the two words “perpetuity” and “universe.” You know, “We claim the rights in perpetuity throughout the universe.” It’s like, oh god, have a little modesty at least, limit it to the Earth.

But the contract was also saying, for the DJ set, that I as the DJ am granting Red Bull the right to use all tracks. Like if you’re a DJ you’re playing other people’s tracks, you don’t control the rights to those tracks. So it’s an impossible thing they were demanding in the contract anyway. And then they were also demanding the rights to use the music for anything that would be played in my talks. So if you notice in my talk, the two things to notice are that I’m not holding a can of Red Bull (laughter) and also that I don’t let them play any of my music because the contract said they would then have the rights to use the music. And it was written in a weird way that could be twisted and misused so that they could use that music for anything.

I also insisted on no recordings and no archiving. And then what I didn’t realize, too, is that the lecture wasn’t just going to live there on the Red Bull RBMA website. It was actually then going to be on YouTube and I have a lot of problems with YouTube.

The thing that freaked me out though is that when I got the contract, that was the first time I went to the RBMA archives. The way it was sold to me was like, “It’s just about the lecture, it’s just about the DJ gig.” It wasn’t, it was about amassing a huge archive that [Red Bull] controlled “in perpetuity throughout the universe.” And there were already like 450 lectures or something on there. And I thought, “How many of these people actually just signed that contract without thinking?” And then the other thing that also pisses me off is, how many people actually got them to rewrite it in a decent way? And then if [Red Bull] was willing to rewrite it in a decent way, why wouldn’t they just send a decent ethical contract to begin with?

That’s why this industry is such an unpleasant thing to deal with and why people retreat into their dreams of doing what they love, because the reality is that it’s just a totally fucking corrupt business.

I didn’t even start doing music writing for actual publications until a couple of years ago. And then it only took me less than a year to realize, okay, I don’t even want to be a part of this wider industry to the extent that I thought I did.

I just consider it damage control, You know, like I’m just minimizing the troubles that are gonna come my way by staying small.

I watched that Resident Advisor documentary, that was fun. There’s a part where you say how you don’t like being around “creatives,” you dislike concerts, you dislike the industry. It’s nice hearing that. For one, because I also dislike concerts, I think they’re antithetical to why I care about music in the first place.

I mean, my biggest nightmare, I always say, would be seeing Kraftwerk live. Why would you ever want to do that? It’s all about the records.

I think one of the most exciting things about art is the courting process. Really getting to know all the nooks and crannies of a record. And then really being able to dig in deeper, whether it’s understanding the historical context, the musical lineages, and then having it be associated with a specific period of your life and the places you live. When you’re in a concert setting, it’s sort of like, oh, now I have to share this experience with other people who have a completely different experience than I have with this band.

It’s like the difference between a straight person’s relationship to a Whitney Houston song and a drag queen’s relationship to it. You know what I mean?

That makes sense. Do you not consider yourself an artist then?

I consider myself a cultural critic, I guess if I had to label it. When I do audio work or video I refer to myself as a producer, not in a capitalist, funding sense of “produced by,” but in the constructivist sense of production over creation. I see what I do as an act of cultural criticism, music criticism, and media criticism while operating from within. So I’m much more aligned with criticism, which I think there’s a tremendous absence of. I’ve never identified as an artist or a musician. I’ve actually been very clear about my opposition to those constructs. I’m critical of them because of their relationship to very specific notions of creation and creativity, authenticity, and originality under patriarchy that have specific power relationships, not only to gender, but also to race, class, religion—all these things that the themes of my work tend to be critical investigations of.

There’s this supremacy of the written word—people appreciate word or text as the method in which criticism or any sort of thinking is often done. The things you release have extra-musical stuff with them. Do you feel like it is always going to be necessary to have, you know, this extra-musical stuff, in addition to the music or the videos that you make?

Even if it’s a CD with text and graphics, I would consider that a multimedia project because it includes visuals, texts, and audio. I try to do things in a way where the text is not simply explaining or narrating the audio, or vice versa, but that there are layers that play off each other and fill in gaps where the other ones have openings. I’m trying to create some kind of reflective discomfort rather than some kind of elation. A project like Deproduction would be the peak of that, because it deals so much with sexual traumas and incest and things like that—I think that it’s okay to be upset and it’s okay to have a negative experience in public, those can be helpful to understanding oneself and the social dynamics you’re in. But clearly the video and text and audio in that are all in antagonism with each other, even though they could also be seen by some as very literally illustrating each other. But for me they’re not illustrating each other at all; they’re all quite separate. And you try to figure out how to go through this disconnection.

Was there ever a negative experience you had involving art that made you recognize the productivity or importance of having such an experience?

When I was 18, I kind of fled the American Midwest to go to New York to study at Cooper Union. It has a good reputation, but it’s actually an incredibly modernist, conservative program. It was a typical art school where you spend your first year going through this teleological, progressive narrative of Western art history, starting with the realism of the Renaissance and then starting to get more textural and abstract with pointillism and then cubism, and somewhere in there there’s constructivism, but that has to do with weird Marxist materialist stuff so that’s just like a little blip and then quickly we get into expressionism.

I was really into the kinds of art criticisms that were going on at the turn of the 1900s. Things that were written by George Grosz, like The Art Scab or Art is in Danger, those and the constructivist manifestos. They all had very precise analyses of the problems of galleries and museums and art institutions that were emerging under modernity. Those same critiques still applied to 1980s New York, where I was studying. There were still the same exclusions: it was really difficult to get anything shown if you weren’t just a white male. And it had to all conform to the language of white male creativity in relation to the gallery space.

I was interested in constructivism and then that made me interested in minimalism. For example, Frank Stella. The idea behind minimalism—basically, this idea of a canvas or a board with flat paint on it—the gesture, the metaphor behind minimalism for people who’ve never gotten it was that it’s trying to shatter, get away from, and deny the types of illusion that representational art is usually about. The ideal is for a viewer to be brutally confronted with solid matter, devoid of illusion. And that is a gesture that, in relation to a kind of Marxist historical materialism, is about trying to have a more immediate relationship to the construction of histories and to the processes through which illusions and ideological productions occur.

If you read an early interview of Frank Stella talking about his paintings, you see it’s just a canvas with stripes on it, but he’s talking about some interesting things that relate to social materialism and trying to get away from the deception of illusion, which is always in favor of the ideological production of the bourgeoisie. Those sorts of interviews were important to me. But at the same time, at the end of my second year—it was a four-year program—I had a critique session. I had been doing minimalist work and the rest of the students were all doing expressionist work. And they were very hostile to the idea of anybody my age—anybody so young—jumping to minimalism because, again, with that art-school way of teaching history, you have to start with realism and you have to then grow through the stages and styles, like “Rothko, didn’t get to that kind of level of abstraction until he was in his fifties, how arrogant of you to be doing it at your age…”. This sort of absurd stuff that made people, like… they’d key my paintings and vandalize my work and my studio space. It was really hostile. And imagine, I’m 19 years old dealing with this.

And so there was this critique session at the end of my second year. I had presented some minimalist panels. It was a disaster response. Nobody fucking got it. And in the end there was this one painter—her work was like the worst kind of emotive, expressionist, figural bullshit-horrible-nightmare painting that you could imagine happening at an art school in New York in 1987. But I really have to thank her because she said to me, “I get what you’re saying about minimalists and stuff, but in the end, like you’re still making a painting. I don’t get, what’s the difference between your painting and mine?” And I was like, “You’re right!” And I never painted again (laughter).

I managed to get through the end of the program by finding professors who would allow me to submit t-shirts and placards that were being made for direct action groups—activist work that I had been involved in separate from the art stuff. I was not in any way intending to sell that work as art—to socially sell it as art. It was just to fulfill my academic obligations to generate studio work and complete the program. Like, silk screening posters for a demonstration and finding a professor who was cool enough to be like, okay, so that qualifies, you’re not going to get kicked out of school cause you’re not painting.

Why did you stay in art school despite having many qualms with it?

Well, because I came from an upper lower-class background. It was a big deal to go to college. It was very indoctrinated in me, y’know the whole thing, “If you don’t have a diploma,” blah, blah, blah. So in the end I graduated from art school. I wasn’t able to find any work. The only work I could get was as a secretary because I could type fast. And typing was a course that I took in high school, not even in college. So yeah, it’s all bullshit.

I also got lucky because I had applied to different graduate schools, like the History of Consciousness program at University of California, Santa Cruz or things like that. And I have to say the best thing that ever happened to me was that I wasn’t accepted at a single graduate program that I applied for. It saved me so much debt. It saved me so much psychological enslavement to academia that would have just totally made it impossible for me to do the types of work that I do now, as a person in my fifties. It would have totally shut down the entire trajectory of everything I’ve done.

So, that’s basically where I was in terms of the arts. Everybody in the arts reads this history and knows these critiques, what the constructivists and people like George Grosz were talking about, they know the critiques of Warhol and pop art and the whole thing about Warhol being anti-authenticity. And yet the Warhol foundation will sue you if you print one of his copies of a Coca-Cola logo? I mean, it makes absolutely no sense, right? The art industry just keeps going, business as usual, despite everybody knowing all these critiques about creativity and stuff being bullshit and I thought, well fuck that. But you know, culturally speaking, music is even worse. Because in the world of music, those critiques of authenticity and authorship and originality haven’t even made it to the public sphere. And even people in the visual arts who completely understand from a critical perspective the notion of originality and authenticity being bullshit, they still believe in the authenticity of the blues musician or things like this. So basically what I’ve been doing in my work in the audio field is just performing the failures of those critiques that didn’t take hold in the arts and just repeating those failures in the music industry, knowing that the critiques of authenticity, of authorship, of originality will just fall on deaf ears.

Do you feel like you’ve been successful in doing that? And I guess that brings into question, what do you feel like success means in this context?

I’ll take the word success to not be about a kind of capitalist success, but “have I conveyed those critiques in ways that actually made sense to people?” And of course, these critiques and analyses are not gonna make sense to most people and most people don’t need them to make sense. The things I do are basically minor discussions that are not meant for populist success in that sense. The success would be about having some kind of use value on a minor cultural level. That to me would be something that I guess you could frame as success. Although success is not a word I would ever use personally because it’s too optimistic, and it’s also too aligned with certain ideologies, this particular way of finding use value or any kind of value grounded in financial and cathartic values. I’m critical of both of those.

It’s kind of like in the same way that, as a non-essentialist trans and queer person, you know, I have the same kind of problems with the younger, LGBTQRSTUVWTFLMFAO world today where it’s like, cancel culture and everybody feels like the solution to being shit on in this world is to shit on everybody else and exert the same types of totalitarian authority on other people. At the same time, it’s like the only way that you can be publicly accepted is if you’re either on a transition trajectory, or at least using hormones. There’s no large scale critical rejection of the medical industries, it’s mind blowing.

Mainstream LGBT ideologies are all pride-based, and they are all about power sharing. I’m more interested in divestments of power. Even within LGBT sites, the types of discourse that I’m interested in and trying to generate are still for a minor audience. That is literally the queer factor of it, that it is anti-populist. I’m not concerned with that kind of universal appeal. The metaphor I’ve often used is mathematics. Pop, mainstream cultures, even in subcultures, are kind of algebra-level. But a lot of times we need to have more precise conversations that are trigonometry- or calculus-level, and so forth. If it means that I’m going to use calculus, knowing that a lot of people might not get it at that moment, but that they might get it some other day or something, that’s okay. I’d rather put the effort into content that I feel has more critical use value than the populist algebra-level stuff, you know?

Do you feel there’s a reason for why the younger generation of LGBT people have this restrictive view of how you “have to be” and “express yourself”?

This is the byproduct of decades of cultural transformations moving away from, when I grew up, issues of homophobia and transphobia, and into issues of heteronormativity. Dominant culture figured out that it doesn’t need you to not be gay or to not be trans, it just needs you to be heteronormative. So today if you are trans-identified, and your ambition is to transition into one of the two gender binaries, or you want to be non-binary, but still advocate for this idea of “queer family values,” and “employment is great,” and “having kids is amazing,” and military service—as long as you’re heteronormative in your values and work ethics and social systems like that, the dominant culture figured out, hey, there’s no fucking problem!

Identity politics is how these things get sold on the dominant level and also how they become extracted from social-material frameworks, and become something essentialist that’s about self-fulfillment and individual identity. Culture then creates this world in which we’re ideologically fed this idea that “It’s not a choice.” We have no self-agency in terms of our queerness and sexuality and gender, and the choices that we make are all about manifesting our lack of choice. It’s all about being “born this way,” like Lady Gaga with her anthem and all this shit. Those people are not my allies because I’m interested in the ways we might have forms of agency and social mobility. I’m really not interested in identity, I’m interested in practice. And I’m concerned with minimizing cultural violence. I’m not concerned with maximizing visibility and pleasure. And that is a different agenda than the Pride-based movement. So, it’s a deep antagonism.

The Western model for civil rights has always been an equation in which visibility equals power in terms that are understandable and not offensive to the mainstream. Accordingly, the closet or practices of withholding or keeping minor become taboo, because basically the Pride movement says that all shame is bad. We have to be “out, loud, and proud,” maximum volume. And this initial premise is really wrong. I’ve been based in Japan for 20 years and Japan has a very long history, going back hundreds of years, of trans visibility. The Western goal is that if we create an atmosphere of trans visibility and queer visibility, it will eliminate or reduce violence, and it will make more understanding, blah, blah, blah. Take Japan for example, where you have hundreds of years of trans visibility basically around MTF visibility (not FTM), yet it’s still one of the most conservative, sexist, homophobic, transphobic places around.

So the forms that those visibilities take on a mainstream level are always in service of the dominant power. And that’s clearly the case with Pride LGBT movements in the West. It’s all about creating a kind of queer heteronormativity that goes along with globalization. I think the whole queer underground fascination with tribalism is all about nationalism and, like, an absolute bail on democratic practice. You end up with the equivalent of the American “vote red or vote blue” and there’s nothing else, and there’s no functional Left, and everything’s a ruse and sell-out.

I know in general you’re not an optimistic person…

Yeah (laughs).

But I’m wondering, do you feel like there are things that can be done to prevent people from being swept up in this? The allure of specific identities that people take on and then just being okay with serving the dominant culture, with serving heteronormativity? Are there ways for people to break out of that, to think more critically?

On a mass scale, I would say no. But that’s, again, not my interest or agenda. From a nihilistic and very realistic point of view, history shows the answer is no. But it’s kind of like this quote that Mark Fell and I used from the UK labor organizer Tony Benn in one of our house tracks, where he says something to the effect of, “Each generation has to face the same fights over and over, there’s no final victory, but no final defeat.” And I think that notion of perpetual struggle, a kind of non-teleological world outlook, is helpful.

Teleology is the idea that everything’s on a progressive narrative scale, like humanity’s getting better, that sort of myth. We’re not on a teleological path of things getting better. We’re in a kind of constant state of chaos and violence. And so it’s not about ever being able to eradicate violence, but simply the question of how do you reduce violence? How do you minimize the effects of violence? That kind of outlook requires a different type of strategizing than the kind of optimist-driven, idealist-driven things that are basically trying to mobilize people around impossibilities at the expense of losing sight of real material conditions.

Of course, people tend to get engaged in the things that actually have the most immediate relevance to their lives. Most didn’t grow up being fag-bashed every day. They didn’t have to deal with it. So they were not forced to develop strategies for survival in relation to that stuff. It's like, if you grew up in an abusive home, you have different ways and different needs and different things about you than people who grew up in a less abusive home. If you grew up with violence outside the home, you have a different experience than people who grew up with less violence outside the home. So all of us are first and foremost creating these interests and tools to cope with things based on what our experiences have been. We’re either trying to hide them, or we’re trying to go head first into them. The result is usually either essentialism and identity, or a kind of non-essentialist, materialist, nihilistic grappling with hopelessness. And so you can understand why the promise of fulfillment through identity politics is alluring to the majority of people, because, fuck it, you only live once. There’s nothing else and might as well make the best of it. But that’s just a kind of laziness that perpetuates violence, I think. It turns a blind eye to the ways in which one’s own lifestyle stands on the heads of others, no matter what we’re doing. There’s no getting away from it.

I think about how nowadays we see just so few communities. There’s such a dearth of real strong communities such that people don’t even know what a community—a helpful one—actually looks like.

The surrogate for that is the ideological production of this idea of the “LGBT community,” the way in which it’s referred to constantly as a community when, in fact, so many of us are living in isolation, social or physical.

Have you ever felt part of a real strong community?

No, I haven’t. But that doesn’t prohibit one from being involved in social activities and social organizing. This is also one of the flaws of Pride-based movements—trying to sell the idea that we have to be a community to share solidarity. It’s like selling family. Fuck family! Seriously, fuck family. It’s one of the most disastrous, hierarchal, nightmare-feudalistic vestiges around—fuck family! And it’s like, if people are constantly selling this idea of community as a foundation to getting along, that’s why it’s all so fucking empty, because we aren’t given any tools or ways to think about how to interact with each other under the reality that we don’t really get along so well. And why does that need to paralyze our capacity for kindness and cooperation?

I think that community quickly becomes cultic. We can see it being cultic even on the pop, mainstream level of American politics. The marketing of community in relation to the marketing of identities is something that I think we need to be critical of. In all honesty, I haven’t had any experience in my life of communal fulfillment. At the same time, I was very involved in activist work and community-based organizing when I was younger. It all kind of fell apart for me in the early ’90s when, in the U.S., there was a political co-opting of the language of Leftist activism and ACT-UP and groups like that, which led to the centering of identities. Essentialist identity politics really became crystallized. You had the majority of these independent, direct-action groups being transformed into CBOs, or Community-Based Organizations. CBOs tended to receive federal or city funding, things like this. They were suddenly accountable to the very bureaucracies that they were established to critique. It’s like talking about philosophy while being an academic in a university. You’re trapped in that system then. And you’re obligated to tweak what you do and what you say to meet the needs of the very people you’re trying to dismantle.

There are ways to work with people that we don’t get along with. And that actually came up as a question at one of my performances of Soulnessless, a project that’s very open in being against religions and this sort of thing. At the end, there was a guy who asked a question—actually people thought he was a plant in the audience because he was so performative—it was a Muslim guy who was saying like, “Hey, you said you hate all religion, including mine. You even said, “Fuck religion.” And then he said a kind of cleansing word to purify himself after he said this swear word. And he’s like, “How do you expect me to respect you, if you’re telling me that you don’t respect me?” And I was like, I’m not concerned with respect. Respect is about power and it’s about holding people up. I’m interested in divestments of power and our ability to still have a conversation and be civil without that. A person doesn't have to pretend to respect me, just to say something the opposite when they leave the room. And it shouldn’t matter if we respect each other or not. That doesn't have to be the terms of qualification for whether we can interact with kindness.

Think about how tradition also plays into all of this. In the West, so many people, when they think about how to reject and how to critically respond to the problems of dominant Western culture, they retreat into a fantasy of non-Western tribal whatever. It’s this weird kind of orientalist reinvestment into traditionalism. I think it's more useful to be anti-traditionalist. I feel like we suffer from a lack of an anti-traditionalist movement right now, because for most people it’s all about respect. It’s all about respect. And respect is oftentimes entwined with very orientalist, colonialist fantasies of what the non-Western Other is. As if like tribal life is not incredibly confining, defined, limited, and restricted in terms of what roles people can play. All human society is a nightmare. All human societies need resistance.

I wanted to ask about your time in Japan, comparing the country now versus when you first arrived 20 years ago. What have you seen take place in the culture—are there things that you have noticed in your time there?

Japan, like most Western countries and first world countries, has become increasingly conservative over the last two decades. I’ve talked about this several other places before, but I think the biggest arc I’ve seen here was, around 2003, there was a burgeoning gender-free movement—gender-free education and these sorts of things. At the time it was prime minister [Junichiro] Koizumi and education minister [Shinzo] Abe. Abe later became the prime minister that we were under for 15 years or more, but Abe was the education minister who was ordered to basically shut down the gender-free movement. And he did it by eliminating Japanese feminist texts from public libraries, making sure that the public school systems didn’t allow any gender-free publications or texts. This of course also came with nationalist identity tendencies, because the concept of feminism and the concept of reducing gender bias is always seen as a threat to mainstream culture, because quite literally, it is. Gender bias is the foundation of patriarchies and patriarchy is the foundation of most every culture I can think of out there. Gender bias creates incredible suffering for everybody, not just women, not just queer folk, but also for men who have to perform very specific cultural roles. And it’s all a nightmare.

So they went through this process of eliminating that movement and re-investing in a kind of conservative, nationalist narrative—in family values and that sort of shit. As a result, things like the sexual landscape became incredibly conservative. The sex scene in Japan today, compared to 20 years ago, is radically conservative. Then, as a result of the hyper-aging society, the real concern that politicians have about that is a kind of financial one—how do you pay for the social pensions of all these seniors if there’s not enough income tax coming in? If you’re a non-xenophobic state, one of those solutions would be to allow more foreigners in who would be ready to pay taxes right away, to generate that revenue. But instead there was a kind of horrible quote by the former health minister where he said, “Women are like birthing machines, and we need to speed up the assembly line.”

It became about, “Oh yeah, the reason why Japan is fucked up is because we’ve lost our family values! We’re not having enough kids! You know, too much gender equality!” This has been the kind of cultural destruction that I’ve witnessed over the last 20 years. And it’s become a much more boring place in that regard, but at the same time it’s very on par with changes that have happened in the West, too.

Would you live somewhere else? Are you content with living in Japan right now?

Yeah I’m here for good. I mean, I don’t have other visa options and it was a fluke that I was able to get here, but the reason why I live here is basically personal safety. I moved here when I was 32 and I was still being called a faggot every time I left my house in the U.S. Here in Japan, of course, there’s people who who dislike others, but that bias is usually displayed through silence and by icing you out and ignoring you. If you’re raised in Japan and you’ve internalized that silence as oppressive and painful, that’s how it feels, in the same way that growing up in the U.S., where people feel entitled to spit and throw punches and say shit—whatever they’re feeling—affects me. But for me, this silence is golden. I’m capable of surviving here with a healthier mental outlook than I did in the U.S. That for me is the main thing. But I have no fetishistic, romantic attachment to Japan in any orientalist sense or anything like that, you know. But I appreciate the fact that it’s very safe. And it seems that’s what happens when you take away narcotics and guns. People actually kind of treat each other nice. Who’d know?

Are you anti-gun then?

I’m a pacifist. Which is even less popular than being an atheist.

What would be your response to people in America, those who are coming from minority groups, who would say that they would be better off arming themselves for protection?

I understand the sentiment. I do think that there are times when people need to defend themselves. And I understand this notion of self-defense, but I would say, how many incidents of gun violence have you heard about that were related to successful self-defense, versus how many were related to failed attempts at self-defense? Having a gun is not going to increase your survival rates. If anything it’s going to make it worse. Statistically speaking.

For me, I came to pacifism in the same way I got led to my understandings of queerness and transgenderism—it’s not because of some internal manifestation of who I really am, it’s more the grotesqueness of those who enacted violence against me which made it impossible for me to socially align myself with what it is to be a heterosexual, gender-reconciled, white male, pro-army, pro-family, pro-money, pro-racist, pro-religion… I can’t do any of it. They broke me, as a kid. That’s how I came into my anti-essentialism in terms of identities, from the violence and abuse that was being put on me. It didn’t even fucking matter how I identified, nobody fucking cared. They forced their identifications on me. The punches came anyway. So, like that. And then I just understood that, okay, I didn’t want to replicate that violence. So I’m a pacifist.

But I think it also has to do with philosophical ideas I was indoctrinated into as a child. My middle name is Martin, after Martin Luther King, Jr. He was assassinated a couple months before I was born and my parents named me that. I grew up listening to records of King’s speeches, and I just absorbed the message that, you know, violence hurts and there are other means of resistance that can grant cultural momentum. It goes back to that Tony Benn quote about how there’s no final victory, no final defeat. So I don’t see an urgency to embrace violence to bring about “the revolution” that will end violence. The violence never ends. So I’d personally rather withhold from participating in it as long as possible. I know there are people with similar views to mine that are forced to pick up arms, and I feel for them.

In talking about divestments of power, a lot of people do suggest some sort of bloody revolution. How do you feel a divestment of power can occur given your pacifism?

Well, not in a revolutionary sense. I am focused on the minor level and not on the populist level of agendas aimed at transforming society on the major. It’s just not going to happen. Even if you get rid of guns, there’s other violence out there, and it’s never going to end. And by and large it is going to be perpetuated in alignment with dominant ideology. I’ve made a choice not to participate in that when possible, in terms of trying to be as careful as I can about what types of violence I enact on others. Holding a weapon that could kill people? It’s not my thing.

Given your general distaste for media, do you mind sharing the last piece of media that you feel like you did enjoy, and what stood out about that for you?

Maybe it was this Australian film, The Nightingale. But again, I can only like a film so much… I wish I could fix the ending of that movie, actually. Both of the main characters should have died, not just one. You have to be kind of young to really get into a film or get into a piece of media. I think like, for my generation, I was really into Tongues Untied and Full Metal Jacket. Full Metal Jacket just blew my mind. Or Blue Velvet, the only David Lynch film that actually has a plottable structure and cultural critique for me. Those sorts of films. My Life As A Dog was another one that was a big, big, big film for me. 1984 with the Eurythmics soundtrack. And, of course, Black Lizard, the film that there was a clip of in the Resident Advisor documentary. You can tell it’s mostly all ’80s films, but that’s also when I was at what’s called the age of indoctrination. I was fucking 18 years old.

What ideology were you indoctrinated with that you feel was the most difficult to unlatch from your brain?

No matter how long I live in Japan, I’m still very American in my thinking, and I recognize that, and I don’t stress about it, but I am aware of it. I appreciate that my experiences in Japan have allowed me to step back from and unpack certain dynamics of American ideology. I think the main one was unpacking the myth that visibility equals power, because that was such a doctrine of the era of activism that I was a part of. The ACT-UP slogan was “Silence = Death.” It was that in your face; “You have to speak out.” And at the same time, I’ve lived a life of closets just to enable myself to negotiate social settings and also for self-defense. There’s been a real need for secrecy and withholding and to be closeted at times. Being on the one hand constantly out and on the other hand being constantly closeted, that is a simultaneity that I very actively worked on without having one exclude the other. And I think coming to Japan and having the myth of visibility dispelled for me was just huge. That allowed me to put my own practices of the closet into a different light where I didn’t have to carry the weight of Western liberal guilt about being closeted and about what closets mean. How we can use that history and not just have to throw it away because being Prideful is in vogue. Queer Pride for me is like a lesson unlearned because Pride is certainly the biggest weapon of the people who’ve enacted violence against us.

Thanks for sharing that. I think that’s something people don’t even realize is a standpoint you can have.

We’re conditioned to feel that things that feel good are good, and that’s absolutely not the case. By coincidence that might happen at some points in time, but the idea of equating things that make you feel good with things that are not violent is a mistake. It’s better to assume everything is violent and start from there. Everything is somehow enacting a form of violence on some level, consciously or not, deliberately or not. You start from there, rather than starting from like, “You go girl, feel Pride!” That just derails so much kindness, I would say.

What do you have in your life, or do you engage with in your life, that is a source of joy?

The answer every time is orgasm. Sex. That’s another reason why, for me personally, I’ve never taken paths of transitioning. I know that the technology and treatments have changed since the generation I grew up in, but I’ve just known too many trans people who’ve had their sexualities destroyed by transitioning therapies, and it’s a subscription lifestyle that I can’t do.

I never drank, I never did drugs. For me, it wasn’t a moralistic thing against it. It was more feeling so out of control of the circumstances in my life that I didn’t want one more thing between me and reality. I get how a lack of control is exactly why most people turn to those things, but it’s like, I can’t even deal with that extra step of detachment. And that led to me experiencing club life and culture and trans nightlife completely sober. That also kind of led me to different insights on how to approach life as a non-essentialist transgender person on a budget.

Seeing a community, a group of people who are so plagued by poverty, being enslaved to life long subscription-based medical lifestyles is a tremendous tragedy. Especially in the U.S. where there’s just no healthcare. A lot of the teens that are growing up now, when they’re experiencing their gender crises, they’re being given hormones and hormone inhibitors and things like that, rather than being given access to feminism and things that would help them understand like, “Hey, yeah, it makes complete sense that you’re miserable under patriarchy, given the limited gender options available and what they mean and what they symbolize and how they affect your life and status. It makes absolute sense that you’re in pain. On the social level, before even worrying about your body, it makes complete sense.” And to help give them language that explains how to socially cope with that in ways that don’t cultivate financial and chemical dependencies on incredibly biased and corrupt industries. That, for me as a trans person, is really the tragedy of 2020 trans life.

When you look at the statistics of people, teens, who turn to the hormone stuff, I read that in the UK something like 70% of them or more were raised female. If you’re seeing that the overwhelming majority of people experiencing gender crises under patriarchy are aligned with the feminine, then, from a sociological viewpoint that’s all the more proof that what we’re dealing with is a feminist crisis, a gender crisis that for most is rooted in the social, rooted in the material. This is information that the dominant systems shut down, like literally in Japan by the federal government having removed certain feminist texts from libraries. So I understand why we’re culturally where we’re at, but it’s also incredibly sad and hard to talk about this stuff when most people are rallied around naturalizing identities.

Over the years I’ve been accused online of being a misogynistic transphobe because I spoke about the cultural differences between someone who transitions from male to female under patriarchy versus female to male under patriarchy, and how there are different relationships to power when trying to enter a position of power versus exiting one, and what is more easily culturally forgiven, what is more forgivable to the mainstream, and what must remain more invisible. FTM culture is almost always invisible because it’s symbolically inseparable from an acquisition of “male” power. It represents a potential acquisition of power, and in the mainstream, the dominant classes don’t want to share power. So that has to remain invisible. Conversely, an MTF stepping-out or kind of forfeiting a relationship to male power is culturally somehow more forgivable. Oddly enough, it was mostly people from lesbian camps calling me out as transphobic against transwomen simply by identifying a cultural difference around what it is to actively arrive at a feminine gender identity versus someone who has accepted one’s alignment with womanhood since birth, and this sort of thing. Like, even that distinction is twisted into denying transwomen status as women. It’s just always been very difficult to publicly talk about these things, especially from a non-essentialist standpoint. And today’s cancel culture has made it harder.

Is there anything that you wanted to talk about or that you’ve always wanted to be asked in an interview that you haven’t been before?

I mean that would be me doing too much labor on your behalf. So I’ll pass on that.

(laughs). What do you mean?

(laughs). Is that you asking me to do your job for you? It’s my attempt at a joke. Never mind (laughter).

No, it’s good. My fatal flaw is I take literally everything seriously. Even when I recognize something’s a joke, I’ll still respond in earnest. And then my friends are always like, “It’s a joke, respond to it like it’s a joke!”

I have to say, that brings up another thing that’s really weird about living in Japan—it’s really fucked up my humor. I’ve always been a very sarcastic person and sarcasm just does not fly in Japan because everything is taken with a kind of surface sincerity. I feel like I’ve really lost my sense of humor by living in Japan (laughter). I do consider my projects to be dark comedies. You know, Soulnessless and Deproduction, too.

Obviously these are, on the one hand, kind of intense, but on the other hand, so ludicrous that it’s like dark comedy. But yeah, in daily life, my delivery is so bad. It didn’t surprise me at all that I said something that was attempting to be funny and just got absolutely no reaction.

I’ll take some blame there. I have a question that I ask everyone I interview—

Please let it be, “Where do you get your ideas?”

Is that what people ask you?

Yeah, I mean, that’s just like the worst question to ever ask anybody. Yeah, go ahead.

So my question is, do you mind sharing something you love about yourself?

Uhhhhhh, well, why do you ask that question?

To see what the response is.

What kind of responses interest you more?

I think the responses that interest me are the ones—I guess this is selfish of me—that I feel make sense of my understanding of who the person is, or which align with, you know, what has been discussed throughout the interview.

So if they happen to say something that kind of goes along with what you think about that person’s character, then that kind of validates your assessment?

That’s definitely a part of it. The other thing is I think it’s something that people are never really asked, so it usually throws people off guard.

It’s the kind of question that for me, throws me back to like a Catholic religious retreat when I was 13, or something that might come up in an AA meeting or, you know, like something that comes into play in queer therapy sessions. Identifying the thing you love about yourself and, if you can’t self-love, how can you love others blah, blah…

In interviews, when someone gives responses, there’s always this underlying notion that the interview will be read by someone who’s not in the room, that it’s public. And I’ve found that, when asking this question, people free themselves from that a little bit and respond in a manner specific to themselves, looking at themselves and not thinking about the reader looking at the artist.

For a person like me, it does the opposite. I’m instantly aware that this becomes a kind of performance of self-love in the public sphere. I’m not asked to do that much, although I am asked to do it in other ways, through performance. Like the inherent presumed pleasure of the DJ during a DJ set. I’ve had people be really angry that I’m not smiling when I’m DJing, weird shit like that. I find it all problematic. I think this has been more constructive talking with you about the question, and has been more interesting for me, than trying to answer the question.

No, that’s good. This is perhaps the perfect sort of response that could have happened.

You knew it wouldn’t go well asking Terre how she loves herself, that’s just not going to go well.

I guess we should end by talking about how you have a new release out.

Actually I do. You threw me for a second because it’s actually a compilation of old material. So I was like, “Wait, fuck, do I?” There’s DJ Sprinkles, Gayest Tits and Greyest Shits: 1998 to 2017.

Was it an interesting process, picking specific songs and putting them in this new context on this compilation versus their original release?

Well it literally contains every DJ Sprinkles release outside of Midtown 120 Blues. Of course this is solo releases excluding the remixes, but every EP and one-off track and self-remix that I’ve done of my Terre Thaemlitz projects is included on these two discs. So the selection process was really more about, “Can I fit everything on two discs?” There is one slight omission, which is the long vocal version of “Useless Movement” from The Laurence Rassel Show that just couldn’t fit on the disc. And so I ended up just including the radio edit and the instrumental dub.

I have another compilation coming up that I’m going to do. It’ll just be a single disc, but it will assemble all the things that I’ve released under Terre’s Neu Wuss Fusion. So that’ll also hopefully come out this year. And a re-issue of Fagjazz.

Is your reason for having these compilations just so people can have a one-stop shop for these things?

Yeah. You know, because of my ongoing problems with online digital distribution, which is not an aversion to the technology, it’s an aversion to the cultural practices of the distributors themselves. The problems that I’ve had with them distributing my works without permission led me to the unfortunate position, in the early 2000s, of not being able to work with any of the major online distributors. So I’ve just been focusing on physical, offline digital media. I’m still using digital formats, but in a physical form. And I think CDs are a really underrated format. We really need a proper CD resurgence, with people having proper CD players with good digital to analog converters and stuff. And it’s a great format. It just blows vinyl away and that’s such an unpopular view. But CD is great compared to vinyl in terms of spectral ranges, stereo field, bass. Everything that people claim they get out of dance 12-inches, you get more out of a CD for sure.

Well, we’ll call it at that. Thank you so much. I appreciate you taking the time out to do this.

Ending on the unpopular note that CDs are the best format ever.

Information about Terre Thaemlitz’s recordings, as well as her various writings, can be found on the Comatonse Recordings website. Select out-of-stock releases are available at his Bandcamp page. Gayest Tits & Greyest Shits: 1998-2017, 12-Inches & One-Offs can be purchased at Comatonse and Boomkat. Resident Advisor’s documentary about Thaemlitz can be viewed at YouTube.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share thoughts on albums and assign them a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Dean Blunt - Black Metal 2 (Rough Trade, 2021)

Press Release info: Dean Blunt returns with Black Metal 2 via Rough Trade Records.

Purchase Black Metal 2 at Bandcamp and the Rough Trade website.

Jesse Locke: Maybe seven years is the perfect time for a sequel. When Dean Blunt announced Black Metal 2, with its Chronic 2001 inspired cover art, its arrival felt like a welcome surprise from a long-lost friend as opposed to a blatant act of nostalgia. This is a follow-up in the same way as Twin Peaks: The Return, borrowing themes and familiar elements from the original while using them to create something refreshingly new.

At 24 minutes, Black Metal 2 is half the length of Black Metal, never reaching the depths of the original’s deepest sinkholes, “X” and “Forever.” In 2021, Blunt favours brief runtimes, but doesn’t need to crack the four-minute mark to conjure moods that linger long after. After countless collaborations, he and his frequent vocal partner Joanne Robertson sound as natural together as Kim and Thurston or Nancy and Lee. Their voices merge fluidly on “NIL BY MOUTH” as Blunt’s depressive proclamations (“Daddy’s broke / What a joke / Future’s bleak”) are countered by Robertson’s longing desires to be held in a loved one’s embrace. Her most haunting moment occurs unexpectedly in the back half of “SKETAMINE” after Blunt shares sparse details of a violent encounter. As strings swell, she delivers a gorgeously unsettling invitation: “Stay up with me / Maybe you’ll find / A halo in the river.”

There are samples or interpolations woven throughout the album, such as the mournful strums from Fela Kuti’s “C.B.B. (Confusion Break Bone)” in the back half of “ZaZa,” but nothing as obviously spotter-baiting as the use of Big Star and The Pastels on the original Black Metal. Instead, many of these songs sound like they were played live in studio by the small group of credited performers that includes Mica Levi and co-producer Giles Kwakeulati King-Ashong. Midway through the menacing “SEMTEX”, Blunt slyly turns to the camera like Arno Frisch in Funny Games and breaks the fourth wall: “Here we are, back on the guitar.” Black Metal 2 returns to the narcoleptic jangle-pop sound of its predecessor, but these songs are beefed up with bona fide drum kit playing, like the laid back breakbeats of “DASH SNOW” or towel-on-snare ticktack of “NIL BY MOUTH.”

Ultimately, Blunt could have called this album anything, but the time feels ripe for him to revisit one of his most beloved eras. In the early 2010s, when Hype Williams parted ways and he re-emerged with solo LPs like Black Metal, Stone Island, and The Redeemer, it felt like the start of a compelling new chapter. Of course, Blunt has continued to confound expectations with an ongoing list of aliases that sound nothing like his most popular projects. 2018’s Soul on Fire EP offered a brief return to his unadorned approach, twisting up g-funk guitars and Gang of Four lyrics, and now Black Metal 2 marks a proper continuation. His words remain cryptic, revealing only brief glimpses into acts of violence on the streets of Hackney, but the music is remarkably tuneful and accessible. It’s not a grand statement, but it doesn’t need to be. At this point in his career, any release from Blunt simply adds to the breadth of one of contemporary music’s most fascinating bodies of work.

[8]

Nick Zanca: After nearly a decade of roaches, loosies, and half-baked collaborations, here we are, back on the guitar. Do not let the sequel stamp or the sitcom-length runtime fool you—to my ears, this is easily the most focused and dialed body of solo work he’s put out since The Redeemer. I am somehow reminded of the duality of lyrical naivety and cavernous arrangements that mark The Blue Nile’s Hats, a production ecosystem in which both platitudes and pensiveness coalesce to embody nocturnal intermediate states. For an artist with a record of evasion and obfuscation, the emotional potence here is surprisingly new and notable; the manner in which his signature deadpan flow lurks above the spaghetti-western harmonica and Mellotron on “SKETAMINE” is gooseflesh, plenty proof of the strength of his curatorial prowess as a producer. If he’s finally proven himself capable of cohesion of this kind on his own terms, I couldn’t fathom how compelling his work would be behind the boards in the context of a major-label project for a veteran pop artist in pursuit of the nitty-gritty. I honestly cannot get enough.

[8]

Sunik Kim: This album is a grower, but in a very specific and unusual sense. The more I breeze through its refreshingly short runtime, the more I appreciate and recognize the airtight hooks, brilliant turns of phrase, and understated production flourishes, and the faster each playthrough goes. But even after reaching this intimate familiarity with the music, I feel not one inch closer to the core of it—a total lack of a personal bond that this kind of intensive listening usually yields. If anything, the music feels utterly impervious to this kind of traditional subjective relationship, resistant to being made a typical object of consumption. The end result is that the music simply disperses itself as it plays, billowing around the room, real, tangible, but impossible to gather, collect, package. If it stays on repeat for hours, it’s more a result of inertia, even apathy; the pause button acts like an escape hatch, when the music merges a bit too seamlessly into the fabric of daily life, and the two, for a moment, become one.

[6]

Vincent Jenewein: I’m going to be honest. I’ve never understood Dean Blunt, even though he’s been an immensely hyped artist for about as long as I’ve been into underground music. I’m just writing this in case I’m not the only one out there who feels like they’re missing out on something. It’s not even that his music strikes me as immediately bad, it’s just that I appear to be cognitively and emotionally unable to “get”' what exactly the appeal is supposed to be here. I do remember that record with the hoverboard and fake pirate radio MC. That was a funny cover and a good gimmick. But was that really all it took to catapult it to the top of end-of-the-year lists? I'm trying to understand.

Listening to this, his main thing still seems to be that he half-sing and half-mumbles—badly and out of tune—over lo-fi-ish beats. The beats are decent, but not really memorable enough to stand by themselves. I think the bad singing is deliberate? Is that the appeal—the bedroom authenticity? Maybe it’s the lyrics? I’ve never been a very lyric-focused listener, so I don’t feel fully qualified to judge those, although they strike me as deliberately off-the-cuff, too. Does that synergize with the bad singing? I think he also rarely talks to the press? Is that a key part of the puzzle, the enigmatic nature of it all?

Unfortunately for me, Blunt’s newest entry—unsurprisingly—sticks to his shtick and doesn't appear to deem it necessary to explain these kinds of questions to confused listeners like me. Of course, he doesn’t need to. Plenty of people like him the way he is. Perhaps, in this day and age, where judgements about popular music are frequently broken down into reductive categories like “stanning” and “hating,” there's something valuable about an artist that leaves detractors not “hating,” but positively perplexed.

[4]

Maxie Younger: As my first reunion with the Dean Blunt extended universe in years, Black Metal 2 couldn’t have been more disappointing: not because it’s bad, but because it’s just fine. The production has undergone some sanitization between installments, progressing from the Blue Iverson school of thought; chrome-polished beats and warm, jangly guitars chatter softly beneath Blunt’s world-weary groans and the silken croon of Joanne Robertson. The glossy sheen of it all is tough for me to process: even the most nakedly beautiful tracks (“DASH SNOW,” “SKETAMINE,” “NIL BY MOUTH,” “the rot”) sound overcooked, risk-averse, almost algorithmic in nature—something to be slotted between King Krule and Mac DeMarco on a habit-generated playlist.

It’s possible that I could be overreacting out of some misguided sense of betrayal: indeed, among fans, the common sentiment seems to be that this is a grower at worst. On the first Black Metal, there was an exciting sense that Blunt was living completely inside his persona, creating as an extension of his own shadowy mythos; he devoted huge chunks of screentime to his odder, more off-putting impulses (the momentum-killing double whammy of “Forever” and “X”; the shrieking buzzes of “Country”) and relished in the grime, rippling edges and disparate genres that bled together like abyssal watercolors. Black Metal 2 sits apart from that persona, deconstructing and reexamining its pieces; it almost feels like an outsider’s attempt to create the kind of “never-before-heard” fake-bootleg sequel that occasionally rises to become a minor obsession in various musichead circles. It passes over me like a light breeze: enough to rustle my hair, but not much else.

[5]

Mark Cutler: Inscrutable as always. Is this meant to serve as a career retrospective or sampler? (and how much did Rough Trade pay to put a black square on a white rectangle on billboards around LA and London?) Every track, every synth and software instrument, references some prior Dean Blunt project. What’s missing for me are the unrepeatable experiments that made Blunt’s best albums so exciting. It’s not as patchy as some of the recent rap-focused projects that have unceremoniously appeared as MediaFire links on the World Music twitter, but it doesn’t really reach the absurd, abrasive heights of his classics, either. This is finally Dean Blunt as well-oiled machine, able to churn out reliable tunes that are distinctly, predictably his. It’s a breezy twenty minutes, but not worthy of its predecessor’s title in either ambition or achievement. Which, now that I think of it, I might go put that one on instead.

[6]

[8]

Eli Schoop: Music critics have this tendency to explain and analyze everything. It seems like a reflex wherein the artform is inherently oblique and resistant to criticism, compared to the dense worlds of movie and literature crit. Thus we invent meaning, not always unwarranted or inaccurate, but it’s a byproduct of the circuitous emotional resonance that music gives us. In the case of Dean Blunt, he has pushed every critical impulse to the edge, rendering it meaningless. Not in a musical sense, because he can be pointedly simple, but historiographically. At the end of the line, we become useless, as the cognition fires and neurons take over.

Black Metal 2 is the quintessential sequel. It is shorter and more compact than Black Metal, acting as a distillation of the previous release. Gone are dissonance, explicit interludes, the cracks so intermittently placed throughout. In its place are the languished chords of “SKETAMINE”, the Ramones interpolation of “NIL BY MOUTH,” and a continuation of modern classical pop so lovingly crafted. This is the smoothest that Dean has ever sounded. Thus, more questions are raised, and Dean has won again. The confusion is the point, Dean Blunt is both an indie rock artist and not an indie rock artist. You shouldn’t have read this.

[8]

Average: [6.63]

Ryuichi Sakamoto + David Toop - Garden of Shadows and Light (33-33, 2021)

Press Release info: Garden of Shadows and Light is the first collaboration between Ryuichi Sakamoto and David Toop, presenting the entirety of a concert performed in London in August 2018. With their collective musical experience encompassing collaborative work with figures as diverse as Evan Parker, Alva Noto, Arto Lindsay, and Christian Fennesz, in contexts ranging from pop session work to film scores to sound installation, no one could be sure how Sakamoto and Toop would approach their first concert together as a duo. From the opening moments, in which Sakamoto’s delicate inside-piano work is paired with distant scrapes and moans from Toop’s prepared lap steel guitar, it became immediately clear that a subtle, at times hushed, form of free improvisation is being practiced here, one in which space, pause, and silence often take on heightened importance.

The album’s title takes inspiration from the aesthetics of Japanese gardening. The spatial metaphor this suggests is apt, as listeners can imagine themselves wandering through a subtly changing environment, chancing on beautiful details and admiring them before moving on. We are led through a series of discrete moments, each uniquely shaded, whether by highly amplified small percussive sounds, austere electronic tones, or the mournful tones of Toop’s bass recorder. The course of the music follows a non-teleological drift, in which Sakamoto and Toop seem less concerned with establishing an overarching structure than in allowing each moment the space it needs to develop and breathe.

Purchase Garden of Shadows and Light at Bandcamp.

Vanessa Ague: Garden of Shadows and Light conjures imagery of my sunset walks in the forest, when the hum of cicadas overtakes the buzz of the neighbor's lawn mower or the crackle of the grill. I imagine the smell of fresh cut grass, or the earthy scent that permeates after a summer rain, as I wade through the ever-evolving music. David Toop and Ryuichi Sakamoto found inspiration in nature when improvising this music, too, imagining Japanese gardening as they played, branching from delicate flute melodies to bursting electric guitar as the sounds of a gentle forest sing underneath.

These sensory details tie Garden of Shadows and Light together. Sparseness and magnitude exist hand-in-hand throughout the improvisation; this is patient music, focusing on intricate, soft sound to create serene imagery. And when Toop and Sakamoto trade distant scrapes for bellowing electric guitars, the music is at its most compelling—an eruption of untamed sound built from all the minute details they established before. As I listen, I’m reminded of the riches that come when I “stop and smell the roses.” Garden of Shadows and Light is a meticulous journey through the imaginary, showing us all the power that’s tied to the tiniest moments, if we stop to notice.

[7]

Maxie Younger: Garden of Shadows and Light is the ultimate set-it-and-forget-it track, opening with a casual interplay of decaying percussive strikes, screeches and squeals that gradually morphs into something wholly unique and eerie at its halfway mark: bleached ambient pads that form monoliths of light in the mist, an aurora in shades of blue, lilac, teal, alabaster—when I first heard it, I had to stop what I was doing (scooping myself a bowl of ice cream, if you must know) just to bask in its glow. I would almost feel bad for spoiling that moment here if it hadn’t maintained its gripping, tense beauty with each and every subsequent listen: I think the anticipation that now precedes its arrival has actually made it more meaningful of an experience. Is the album worth it for that one scintillating passage, even though it devolves back to the quiet, sometimes abrasive transaction of drones and pointy sounds across an open plane thereafter? Well, I say yes: but, of course, your results may vary.

[6]

Vincent Jenewein: Kind of dull. That was the first thought that came to my mind while listening to this. With the names involved, it ain't bad music, obviously, but our proverbial gardeners Toop and Sakamoto sound like they’re taking themselves just a bit too seriously. They spend their time mostly exclusively channeling sounds from the standard catalogue of “serious experimental music”—slow, droning, dark, metallic, dissonant and minimalist. It gets old, quickly; I think this kind of style works much better when delivered in smaller chunks, with some intermittent dashes of color.

There are a few bits here that could potentially break the performance out of its depressive rut. For example, around thirty-eight minutes, there’s some fun wallowing distortion and chunky tape delay feedback. But these small moments aren’t taken far enough to elevate the overall composition. The artists also don’t sound particularly at ease with each other, only very carefully testing each other’s sonic boundaries. The press release speaks of “free improvisation,” but that can also serve as a codeword for “we were just riffing around, hoping that something would stick,” and “non-teleological drift” is also fancy-speak for “we didn't really know where we should be going with this.”

Over the years, I’ve heard plenty of these austere, improvised experimental live performances in person and have always been left with the impression that neither me nor the rest of the audience has been particularly sonically satisfied. And while sonic satisfaction isn't perhaps the point of this kind of music, I’m still convinced that even the most experimental of musics can not do without a good sliver of perverse, gleeful surplus-enjoyment. I'm sticking with either of these artists’ studio material, where they seem to be more willing to hand out some of that ornamental bliss, even if just in bite-sized portions.

[3]

Gil Sansón: A good ten minutes elapse and I’m thinking this could’ve easily been made in the early ’70s. It’s closer in spirit to the music of Helmut Lachenmann, Michael von Biel, or La Monte Young immediately post-Fluxus than the closer-in-time-and-geography of AMM or Spontaneous Music Ensemble. The piano is explored in the usual way for this style of music, and a full piano chord only makes its first appearance a third into the piece. It doesn’t change the proceedings significantly. Other sounds, even a ghostly chorus, appear haphazardly, often with analog delays that give the music a vintage flavor. As opposed to someone like, say, Keith Rowe or Keiji Haino, Toop doesn’t have a signature sound, at least not instrumentally. His strength lies in his ability to place sounds from varied sources and cultures into a flow that rarely has a clear structure. The aim is often for free association. Sakamoto, for the most part, is unrecognizable here—one assumes he’s in charge of the inner parts of the piano and elements like the aforementioned chorus. My main quip with Garden is that I don’t get the feeling that Sakamoto or Toop are experimenting. They’re playing safe with sounds they’re more than familiar with, and artists of their stature and status can afford to risk falling flat on their faces. It’s not a bad recording nor an unpleasant listen, but it holds no surprise.

[5]

Mark Cutler: The garden is a perennially (no pun intended) apt metaphor for a certain kind of gentle, unassuming album, typically one on which individual tracks drift pleasantly by, without really building up or yanking your attention towards any one melody or sound. This is not such an album. Rather, for much of the duration, Sakamoto and Toop produce all manner of shrill and percussive sounds, which cut through otherwise vast and stark silences. The evocation isn’t placid beds of posies and hanging maidenhairs, so much as wiry weeds clawing their way up from a dusty, rocky wasteland. Slowly, though, melodic elements do emerge and fill the soundscape, and the piano parts in particular are as nice as you’d expect from a titan like Sakamoto. It’s a good and well-balanced slice of live performance, sure to satisfy fans of either of these prolific and adventurous artists.

[8]

Samuel McLemore: Garden of Shadows and Light is a full concert recording of electroacoustic improvisation (EAI) that manages to be more entertaining and less predictable than what one may expect. The key to this success lies in the varied instrumentation shared by Toop and Sakamoto. The typical EAI performer limits themselves to one instrument or sound source at a time—there are plenty of exceptions, but in the realm of live improv this seems like the norm. This approach makes a lot of sense, not only from a logistical point of view, but because EAI is all about reveling in the kinds of noises you can wring out of a familiar instrument by treating it as an abstract sound machine. Not so here, where a pleasing variety of instruments—a lap steel, a piano, an electric guitar, what sounds like a recorder, and what must have been a host of effects pedals and other objects—are not only used as sound sources, but also played as the traditional instruments they are. This back-and-forth between abstract and lyrical approaches (when was the last time you could describe an EAI album as having moments of “lyrical beauty”?) is masterfully balanced over the course of the performance.

[7]

Marshall Gu: I find this album very hard to listen to without thinking about Ryuichi Sakamoto’s async, his last non-soundtrack solo album. async was released in 2017, his first album after battling throat cancer, and it felt like walking through a garden, stopping to regard every plant and every pot. Ultimately, the album explored a duality to find magic in the seemingly mundane. “Life is a wonder of wonders, and to wonder / I dedicate myself.” Garden of Shadows and Light was recorded in collaboration with David Toop, and not long after the release of async—the two albums share much of the same spirit. Per the title, there’s a duality here: shadows and light. There are obviously man-made sounds, like Toop’s bass recorder, that are set against what could very easily be natural noises: the gentle hiss of rain, sparse percussion tones that feel like footsteps on the elaborate walkway. In this context, the keyboard chimes sound like dew collecting at the tip of leaves, finally dropping into the garden pool. That’s the ‘light’ portion of the album: afternoon sun coming through the greenhouse roof. The ‘shadow’ portion is the final third, wherein Sakamoto switches to electric guitar, the darkness from the drone enveloping everyone and everything. At the start of this year, it was revealed that Sakamoto’s cancer had returned, and with that knowledge it’s hard to take the final stretch of Garden even though it was recorded in 2018. Knowing this, the darkness feels far more intense and overwhelming than most drone that I’ve heard. Whereas async plays like an album by someone ready to live again, Garden feels far more resigned. Both are equally powerful in different measures.

[7]

Average: [6.14]

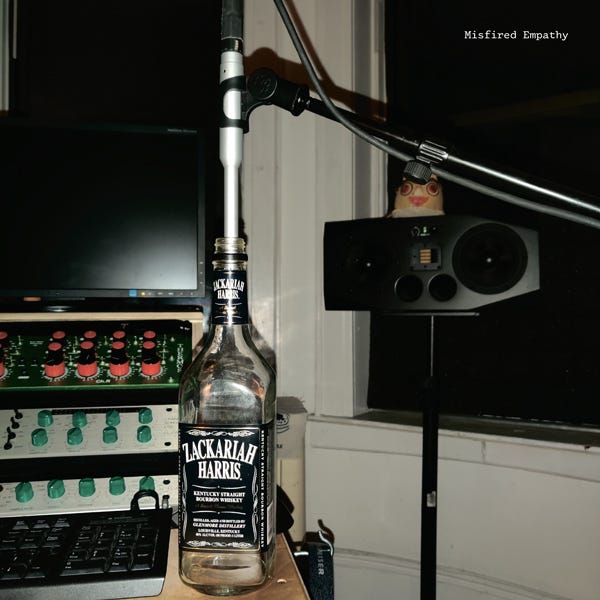

Jack Callahan & Asha Sheshadri - Misfired Empathy (Stellage, 2021)

Press Release info: Jack Callahan & Asha Sheshadri’s 'Misfired Empathy' was recorded and processed in April and May of 2020 in a number of temporarily shuttered venues and the artists’ apartments. This is their first record as a duo.

Purchase Misfired Empathy at the Stellage website.

Sunik Kim: This is a new kind of vocal gymnastics that explodes the matter-of-fact spoken word into sheets of disrupted, warbling sound. The experiment works best at its fastest and nimblest pace; highlight and opener “Self Compassion” deftly shifts registers between obliterated, frequency-shifted masses of barely decipherable utterances and—my favorite sections on here—loping, vocoded phrases that blister and sizzle on the precipice of disintegration. The lengthier pieces, mainly “Estimated Torture,” in actually completing their own sentences and leaning on more subtle spatial processing, drift into more familiar and much less interesting ‘oblique, biting social critique’ territory, tipping the release into the kind of self-aware “performance” during which it would likely happily “talk and text shade.”

[6]

Eli Schoop: Maybe this isn’t the venue. Maybe I should be in Brooklyn, sitting quietly at a talk where this plays, pondering, musing over what it means, until the post-exhibit lecture starts. Maybe the bustling nature of the megacity would provoke a different reaction, stir something in me compared to the tranquil Ohioan peace I am so used to. Should I have listened to Network Glass instead? I lost both League of Legends matches I played while listening to this. It probably would’ve fit better. Maybe it’s because I am not a part of the experimental grant-soliciting industrial complex. Ah well. Can’t say I didn’t try!

[3]

Vincent Jenewein: You could have alternatively titled this “boring field recordings and bad poetry sent through resonant comb filtering: the record.” The artists put the aforementioned source material through what sounds like flangers and spectral resonators. That's pretty much all that happens. The single-minded approach to processing could, by itself, potentially make for a decent, if somewhat narrow, experimental project. As a fan of this type of sound mangling, I do have to say that some of it sounds pretty cool, for example the sharply decaying, hollow metallic timbre on the vocals on “Shipbuilding.”

But the record is dragged down significantly by the fact that the artists appear to have chosen their source material by slavishly following the worst art school 101 tropes. Part of it is taken from field recordings made in venues shuttered during the pandemic. They sound like pretty bog sound art standard field recordings and even the concept itself is an idea so obvious that, in the past year, I think I’ve seen at least three other experimental records employing the exact same gimmick. Over a decade ago, the Berghain / Ostgut Ton camp used it on their Fünf compilation, with rather measured success. The mere fact that COVID happened doesn’t automatically make a mediocre gimmick any better, unless you are following the art school dogma that art always benefits from closely relating to current events. But outside of that bubble, this approach often just comes across as a desperate bid for relevancy by artists that don’t have anything else to say.

Worse, much of the source material here is made up of recordings of various—let’s call them “artistically vague”—ramblings. This has to be the absolute worst trope of these kinds of art-world-adjacent sound-art projects. Open up the dictionary or Wikipedia and ramble-whisper the first entry you come across into the mic or sample a random segment from the day’s news broadcast and boom: instant #political and #art vibes. On “Estimated Torture,” a woman’s voice keeps unethusiastically rambling on about various, seemingly unrelated things. Among those are statistics about how much bottled water Americans drink every year and how many SUVs they drive. Do I spot a reference? I think it’s saying something about the environment! Then it goes back to dictionary definitions and usage-examples of the word “torture.” Is this meant to be a political statement on the legal status of torture? Or just some language games on a random word picked out of the dictionary—who knows! Who cares! I think this might be kinda like the internet! Such vast informational complexity and loss of intersubjective semantic significance. Or something.

I suppose that I, the listener, am supposed to figure the rest out; connect it all together, so the piece can actually “say” something beyond meekly pointing at a bunch of potentially significant things. But I don’t want to. This kind of thing is emblematic of a contemporary art world that has long confused “art is in the eye of the beholder” with “let's lazily and noncommittally hint at a bunch of vague themes and they’ll be forced to make up the rest themselves.” I'm giving one point because at times, the neat FX processing is enough to obscure the actual words being said, but I can’t for the life of me take any more people coercively ramble-whispering vague, pseudo-significant bullshit into my ear. Please. Mediocre, meandering, clichéd art school poetry (is it even supposed to be poetry? Is it “questioning” what poetry even is? Yet more pointless questions—I’d like some answers from projects like this, just for once) doesn’t magically get any better when you turn it into music or sound art.

[1]