Tone Glow 068: L'Rain

An interview with L'Rain + our writers panel on Lucia Nimcová & Sholto Dobie's DILO', Remko Scha's 'Guitar Mural 1', and Backxwash's 'I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES'

L’Rain

L’Rain is the performance name of lifelong New Yorker and musical polymath Taja Cheek. The genre-agnostic project, named in both honor and spirit after her late mother Lorraine, emerged in 2017 with an eponymous debut album that blended meditations on loss and heartfelt songcraft with free jazz and sound collage. Her forthcoming sophomore album and first for Mexican Summer, Fatigue, pushes this kaleidoscopic palette further out to explore, in her words, “the enormity of how to change.” Alongside her musical pursuits, Cheek is also a curatorial assistant at MoMA PS1, where she has organized the ongoing Warm Up series and Sunday Sessions. She has also collaborated with artists Naama Tsabar, Kevin Beasley, and Justin Allen.

Nick Zanca caught up with Taja outside MoMA PS1 the week before Fatigue’s release. They discuss change, community, collaboration, illegibility, improvisation, field recording, grief, and growing up in her native Brooklyn.

Nick Zanca: It’s been a minute—how are you?

L’Rain: I’m… good? Tired! I guess this is where this all begins and ends—fatigue! (laughter).

I am honestly right there with you. I was racking my brain while preparing to speak to you trying to remember the last time we saw each other in person.

That’s a great question...

If I recall correctly, it was after your performance with Kevin Beasley at the Whitney Museum, which actually feels like a lifetime ago.

Wow… that was several lifetimes ago (laughter).

I mean, there may have been a Warm Up or two between then and now, but my memory fails me and time is a construct.

Exactly (laughs).

I remember that collaboration being very loud and cathartic. The two of you took the sounds of a running cotton gin motor from Alabama he installed and then soundproofed and amplified in the space, and you both performed a duo set off that material in the adjacent room. What do you remember about that performance and preparing for it?

We spent a lot of time in the studio just improvising. He called them rehearsals, and they felt like rehearsals, but really we were improvising—just kind of figuring out what tools we were going to bring, how we respond to one another, length considerations and things like that. We had a lot of rehearsals leading up to it, but nothing that we did resembled anything we did in any of those rehearsals (laughs)—but it definitely felt born out of that process. It was deeply meditative, which is such an overused phrase, but it felt like that to me. We would enter the studio, talk a lot, and get to this zone where neither of us remembered agreeing to start playing, but it would just happen. And then we would sort of wake up two hours later and have a recording, listen to it at a later point, and make another date to rehearse again.

Such is free improv (laughter). It’s not often that I’ve seen you working within that idiom. Was it out of your comfort zone?

For sure. I feel like music in general is out of my comfort zone, and that’s why I do it—but improv is definitely out of my comfort zone. I come from a strictly non-improv background playing classical music, which obviously also has a history of improvisation within it, but not for me.

That’s interesting, because you’ve been adjacent to those spaces in your musical history, but you’ve never really explored it on your own—at least in the time that I’ve known you.

It’s true, I haven’t. It’s a definite complex I have. I play with all of these people who are jazz heads—they play jazz, they study jazz and improvisation and it’s such a core part of what they do, and that’s just not my experience. I have a lot of complexes about being a non-jazz girl in a jazz world (laughs).

Is that something you’re trying to explore more of in the future? When the band plays live, I feel like there are sections that read as structured improv.

There definitely are. I mean, if I’m being more generous about my practice and the ways that I make music, it is very improv-based in a way, but it feels different because it’s so private. A lot of things that I write are first takes or first tries at writing, and it sticks—or I find that the most compelling melodies I write emerge that way, usually? So I guess to revise what I just said, it is a part of me, but it feels separate from improvisation in a public sense. Very, very separate.

Let’s go back even further in time and talk about growing up here in New York. You spent your childhood in Brooklyn between Crown Heights and Fort Greene. What was growing up in those two neighborhoods like?

It’s always so hard to answer that—I feel like I’m only just starting to understand it now. That’s my only frame of reference, and now that I’m hanging out with people that aren’t from here, I’m just now starting to understand that. I think about my experience with New York as being the same as being from any small town in a lot of ways, where my block is my world or my neighborhood is what I know—New York is what I know, in that case. I haven’t travelled tons. I feel like a lot of New Yorkers are kind of in that same boat. You have to really go the extra mile to get outside of that universe.

I understand your grandfather ran a jazz club—where was that?

That’s a good question—I know that it was close to where I live now. My dad has trouble remembering the exact location because so much has changed in the neighborhood, his frame of reference was very different. But it was in Crown Heights, maybe like five or ten minutes away from where I live. Pretty wild!

It is wild. Did anyone notable play on that stage?

I’ve heard—the person that comes to mind immediately is Sarah Vaughan, she apparently sang there for a week.

Woah.

Yeah, there’s a whole history of jazz in central Brooklyn that I don’t know, but there are a lot of old heads that have held onto that knowledge. I’m very interested in that, but I haven’t explored tons. I need the right kick in the butt to learn more. It was called The Continental, by the way. I think it was around in the sixties, maybe?

Going from one venue to another, what are some of the earliest memories you have of performance spaces or cultural institutions in the city?

I really started coming into my musical sensibilities in high school, as most people do. I didn’t have a fake ID, so all-ages venues were really crucial for me to be able to see music. There was also a lot more free music available to all New Yorkers. There were a lot of festivals that would happen around the city and literally all you had to do was just show up—those were really formative moments for me. I remember going to Coney Island—I think it was called the Siren Festival? And then there were the McCarren Park pool parties…

Damn, so you were basically around for the peak of Brooklyn DIY.

I was very much around (laughs). It was a wild time. Or the shows at the pier… there was so much free music. I really miss that because I don’t know what else I would have done as a kid. I wouldn’t have seen any music!

Other than the lack of free shows now, what else has changed about the city’s live music landscape?

That’s a good question, I have to think about that one honestly. (pauses). It’s the freeness, but there was also such an interconnected culture of DIY spaces that was also a really important part of my life and the way I was able to access music and culture. That doesn’t really exist now in the same ways. It probably exists in different ways and I’m just too old to know (laughs). But it doesn’t exist in the same ways it did when I was a kid.

Who knows what Gen Z is up to…

Yeah, I really don’t know—maybe they don’t even go outside, but I don’t know (laughter).

It seems more and more likely, but I don’t want to discriminate.

Me neither. I don’t want to be the old phobie that’s like “I hate Gen Z!” I don’t. I just genuinely don’t know if they go outside (laughter).

It’s a whole different echelon. Is there any place from any point in your life where you would go to in the city when you need to think or decompress, or perhaps more appropriately, in the midst of fatigue?

(laughs). I would just walk around. I spent a lot of time just walking and discovering things around the city. That was one of my favorite things to do—I would just pick a starting point, and eventually just feel spiritually when the end point was coming. Just kind of see all the things that one could see, all the weird things, and take it as it goes. Block out four or five hours just to walk around.

Was there one route in particular that you remember, or did it vary?

It really varied. There was never a single route that I would take. Once I walked from the area around Columbia University to my family’s place in Fort Greene.

Holy shit (laughter).

It was very far, but it was amazing.

That’s something out of a Sebald novel.

Yeah, it took a while!

Let’s transition to the fatigue that we’re here to talk about (laughter). Upon reading the credits of the new record, I was surprised to read that it was in fact completed prior to 2020?

Yeah, it was—well, sort of (laughs). It was mostly finished. I ended up tweaking some things during quarantine, but the bulk of it was done before then.

Upon the first few listens, the timing of the project seemed impeccable—not only arriving at a point where we’ve reached the end of our proverbial rope, but we’re also starting to reflect backward and ask ourselves the question posed at the start of the record, “What have you done to change?” I’m curious how your perception of the work, and your own personal notions of fatigue by proxy, evolved between wrapping production and the pandemic, global protest, and climate devastation that was to follow.

Yeah… (pauses).

Loaded question!

Extremely loaded question! (laughs). And I feel like this is a non-answer, but it completely changed and it remained exactly the same. So much of the issues that we experienced during the pandemic were rooted in issues that existed before it, right? I think of the record on the same terms. I thought about all of these things, but it manifested in such a different way. Obviously, I can’t think about fatigue without thinking about quarantine and the protests of the past year. It’s not dissimilar from the first record either, where I was thinking about grief and it ended up literalizing itself, but the more nuanced thoughts about grief were what birthed it.

You’ve frequently worked with brief duration. The first record was roughly twenty-five minutes long, this one barely skirts the thirty minute mark, and in the dozens of times I’ve seen you play live, the sets always seem to breeze by while still keeping this sense of fullness and urgency. I wonder how important brevity is to your music.

Yup. My dad calls me stingy (laughs) and maybe that’s a part of it? I guess it’s more interesting to me to see what I can do with a little bit of time. I don’t know if I go into anything with that in mind, or with that as a guiding principle or constraint. But it’s more interesting to me. Sometimes I just go to shows and I’m just like, “This could have ended a while ago. You didn’t actually have more to say, you’re just saying it longer?” (laughter). I guess I’m just really hyper-aware of that, and I’m like, OK, no one needs to be looking at me doing this thing for too long. That doesn’t matter—I just want to create a moment that feels meaningful and people can go on with their lives.

It’s also because I ask a lot of listeners. As an audience member, I’m often bossy, and sometimes a little bit mean, maybe? I don’t mean to be, but maybe I can admit that I am (laughter). I want people to put away their phones and to pay attention and to be present with me, and I don’t know if that can happen for longer than twenty minutes.

I’ve witnessed that persistence in you—it’s a noble pursuit.

I want to talk about the field recordings and found sounds that you stitch between songs. You incorporated these on the last record too, and to me, these moments never seem like interstitial filler as they often appear, say like the prototypical ambient interlude on an indie rock record, or the skits on an old rap album. Instead, they seem to carry the same weight as the music that surrounds it. What were the personal origins of this mode of assemblage?

That’s also a good question, and I’m really glad that you feel that way because I feel that way. I grew up listening to a lot of R&B and hip-hop, so maybe that’s where I first started thinking about that. I was particularly thinking about Brandy and how the interludes on her albums take the form of miniature ambient ideas—it felt very substantial and notable, I’ve been thinking a lot about them lately. Field recordings in general are also a way for me to remember my life. I have a really horrible memory and that form is really immediate. It’s something that I can revisit over and over again if I need to. I’m realizing more and more that L’Rain is a vehicle for me to remember things and document them. It’s secondarily important that I connect with other people, that people respond to it—in other words, it’s not just me being completely self-absorbed, but I also do it for me (laughs).

Didn’t you archive them on SoundCloud at some point?

Not the field recordings, but these weird doodles that I used to make myself create at a specific time in my life. Just little musical ideas. Some of those include audio recordings, but they’re essentially just little fragments of songs.

When are the moments you choose to hit record?

(pauses). I always do it in cabs. If someone decides to talk to me, it gets recorded. I often get a lot of good advice from Uber drivers (laughs) when they want to offer it up for whatever reason. There’s specific people where I know some of their tendencies and I know they’re about to say something, or I want to remember the feeling of being around them. I also do it when I’m walking around—if I’m hearing an interesting sound that a radiator is making or something, I’ll record that. Or if it’s a meaningful moment in my life. I’ll do it regardless of whether or not something interesting is happening.

When making field recordings, do you ever encounter internal questions of morality or voyeurism? I ask because I know I do.

All the time (laughter). All the time. Completely. It will become more of an issue, and I’ll have to keep thinking about it and trying to resolve it. Sometimes that will stop me from recording, sometimes it won’t. The times it doesn’t… I mean, my intentions are always pure, it’s just to remember—but when I can imagine having a conversation with the person and being like, “Yeah, I did this thing,” and I’m actually able to tell them about it, I’m in the clear.

It’s almost become a concrète music cliché to hear someone ask if they’re being recorded. You have much more intention than that.

I hope so (laughter).

One favorite moment of mine on the record happens early on, at the end of “Find It”—we hear a pastor’s performance of Rev. Paul Jones’s “I Won’t Complain.” Something about the way this lo-fi recording coalesces with your studio-recorded harmonies before the whole thing blossoms into that full-band blast with the organ makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. How did that land on the record?

Essentially, I was attending a family friend’s funeral and I remember listening to this pastor and… yeah, his voice and delivery—it was this whole thing for me. I needed to remember how I felt during that moment. I recorded it literally just so I could listen to it, and it quickly became this thing where I listened to it, like, every day. I just kept coming back to it. I kept talking to my producer Andrew [Lappin] about it, and I was like, “I can’t stop thinking about this recording.” It turned into something very organic, but that definitely was not my plan at all. I was so moved by that service, I wanted to be able to revisit it.

For someone whose work has centered around grief, that moment feels like your most direct depiction of it—it’s an outpouring. Every time that part of the record arrives, I have to stop what I’m doing and bask in it.

(laughs). Thank you.

Another track I’ve returned to repeatedly is “Kill Self”. When I first saw that title on the tracklist, I was instantly reminded of that Amiri Baraka line that you’ve often returned to—you once quoted it in an old artist bio. I believe it came from the liner notes he wrote for a live Impulse compilation with Coltrane and Ayler: “New Black Music is this: find the self and kill it.” This is not a direct question, but I’d love for you to riff on your connection to that idea.

I feel like that phrase sums up a lot for me in terms of a foundation of refusal that I feel underpins everything I’m interested in. It’s just so direct (laughs). I love that. I guess there is something about brevity that I’m into. The line is also very visceral in a way that I really appreciate, and also kind of dark in a way that I’m drawn to—but it’s not darkness for darkness’s sake. There’s a larger purpose that’s actually the most optimistic purpose, which is self-determination. All those things are encapsulated in this tiny little phrase—it’s so brilliant to me.

You are an artist also concerned with the illegible. You said that you don’t feel equipped to describe your own sound in the context of genre—one might go as far as saying you evade it completely. I recall you explaining when you were gigging the last record that you approach aesthetic markers with Roland Barthes’s concept of the death of the author in mind. Between that and the Baraka, both are a perfect framing of what you do—any illegibility on your part leads to the birth of the listener.

Yeah, absolutely.

What do you gain from inhabiting liminal spaces outside binary logic, layering disparate emotions?

I think it’s just the safest place for me to be, to feel like I have some autonomy in telling my own story. It’s somehow both that I’m giving it to an audience to figure out whatever they want to figure out with, but I’m also protecting myself from other people being able to easily determine who or what I am. It’s too hard (laughs). So I maintain that. I can keep a sense of nuance, which is really important to me—especially in the music industry of all places.

That certainly tracks. I don’t know how you navigate it the way you do. I wonder, though, if you’re willing to break your own rule and talk about certain influences you might have thought about, musical or interdisciplinary, upon entering the studio this time. I feel like this is a record dripping with production gymnastics across the board, and I’m curious where impulse and impact begins and ends with you.

I don’t know—Andrew and I did have a playlist this time around. I don’t even know that we shared it with [band member] Ben [Chapoteau-Katz], to be honest—and he’s really the glue of this record in a lot of ways.

I’m inclined to agree.

Yeah—we didn’t share this playlist with him, hilariously enough. I guess it was also because we started the process of making this record before I really knew Ben. Anyways, we had a playlist. I’m sure we were listening to things, but that almost feels irrelevant? It was more… “this sounds so woo-woo, oh my god,” but we were more drawn to… feelings? (laughs). Or materials we had around more than anything else, more than like, “this sound is what we’re after” or something that reminds me of this or that artist (laughs). That’s not really answering the question…

…but I get where you’re coming from. In your case, it’s almost a purer way of working—you become more inclined to dodge referential notions.

“Dodge” is a great word for it—it’s less about trying to approximate another sound, it’s more about trying to dodge predictable sounds, if that makes sense. It’s like “OK, we did this thing that we don’t want to sound too R&B, so let’s change it in this way,” or whatever, knowing that all of the things we’re trying to dodge are also influences.

I like this phrase of yours from an old interview: “my relationship to music is a dead marriage.”

Oh god, I was worried this would come back! (laughs).

Can you expand on this a bit? Do you still believe it?

I don’t believe it. I don’t think it was entirely true at the time either! I think what I was trying to get at was a sense of purpose that I can’t imagine not making music—but that it can also be endlessly frustrating and difficult, and I’m always negotiating my relationship to it. But it will also never go anywhere, it’s a deep part of me, the deepest part of me even. I guess a “dead marriage” is my cynical way of getting at all that—but it’s not dead (laughter). I love it. If I didn’t love it, I wouldn’t do it, but I also don’t know what else I would do.

I’m hesitant to ask any MOMA PS1-related questions—I’ve always respected the fact that you try to bifurcate your musical and curatorial practices as much as possible, so I’m going to keep this one broad, albeit loaded.

(laughs). OK, I think I’m ready.

You are someone who has gone to great lengths to foster and cultivate community in all walks of the city’s music scenes, more than anyone I know. Beyond the events you organize at PS1, you also have been a sideperson for countless bands, including mine, and you ran a rehearsal space and basement venue that I won’t mention by name but that one might consider one of Brooklyn experimental music’s best kept secrets. As performances resume this summer, as your band starts to play out again, as collective perceptions of the “scene” have altered from what they once were, what lessons would you say you learned from the community as it faced crisis this past year?

(long pause). I think I’ve learned how to be generous to myself. I felt a lot of guilt about what I wasn’t able to do for myself or for other people. I learned that I probably didn’t need to feel that guilt, that other people were also going through the big things that they were going through. There can be a lot of patience, we can slow down, we can have a lot of generosity towards one another—and sometimes that generosity means saying no, or not being able to do certain things. And that’s a process, but that was an idea that was definitely sparked in a different way during the pandemic.

I’m happy to hear that you’ve made it to this place.

I mean, I’m still making it—it’s a process of making it.

It never ends.

Honestly, these are great questions!

I don’t want to take up too much of your time from here, but it would be remiss not to mention a few of the friends who collaborated with you on this music. I’m thinking we can wrap this up by naming a few of them, and then you can elaborate on what they brought to the table and to you as a human being. Let’s start with your producer, Andrew Lappin.

Andrew… man, I love Andrew (laughs). Almost everything I’ve ever made I’ve worked on with Andrew in terms of recorded music, a lot of it. It felt really good to have such a shorthand with someone in the studio, and also working with someone who deeply understood the process of the first record, which was really just us staring at each other until we were blue in the face watching City Of God on silent (laughter).

That is quite the image.

That was our whole studio vibe. So yeah, we were really able to grow with each other with this second record. It’s just an exciting and beautiful thing.

Jasper Marsalis, also known as Slauson Malone.

Oh, I just love Jasper so much. His music influences me in ways I’m still trying to understand. We have a lot of synergies. I just knew from the second I heard even a tiny bit of his music that I needed to be connected with him in some way. He sequenced the record, and you can hear little bits of him in it, which also makes me really happy, where you’re like, “that’s definitely Jasper!”

You are kindred spirits, for sure.

Yeah, I love the idea of him leaving pieces of himself in the record. He was extremely thoughtful and didn’t want to do too much of that, and I said, “No, it’s okay, you can do that.” Jasper’s amazing.

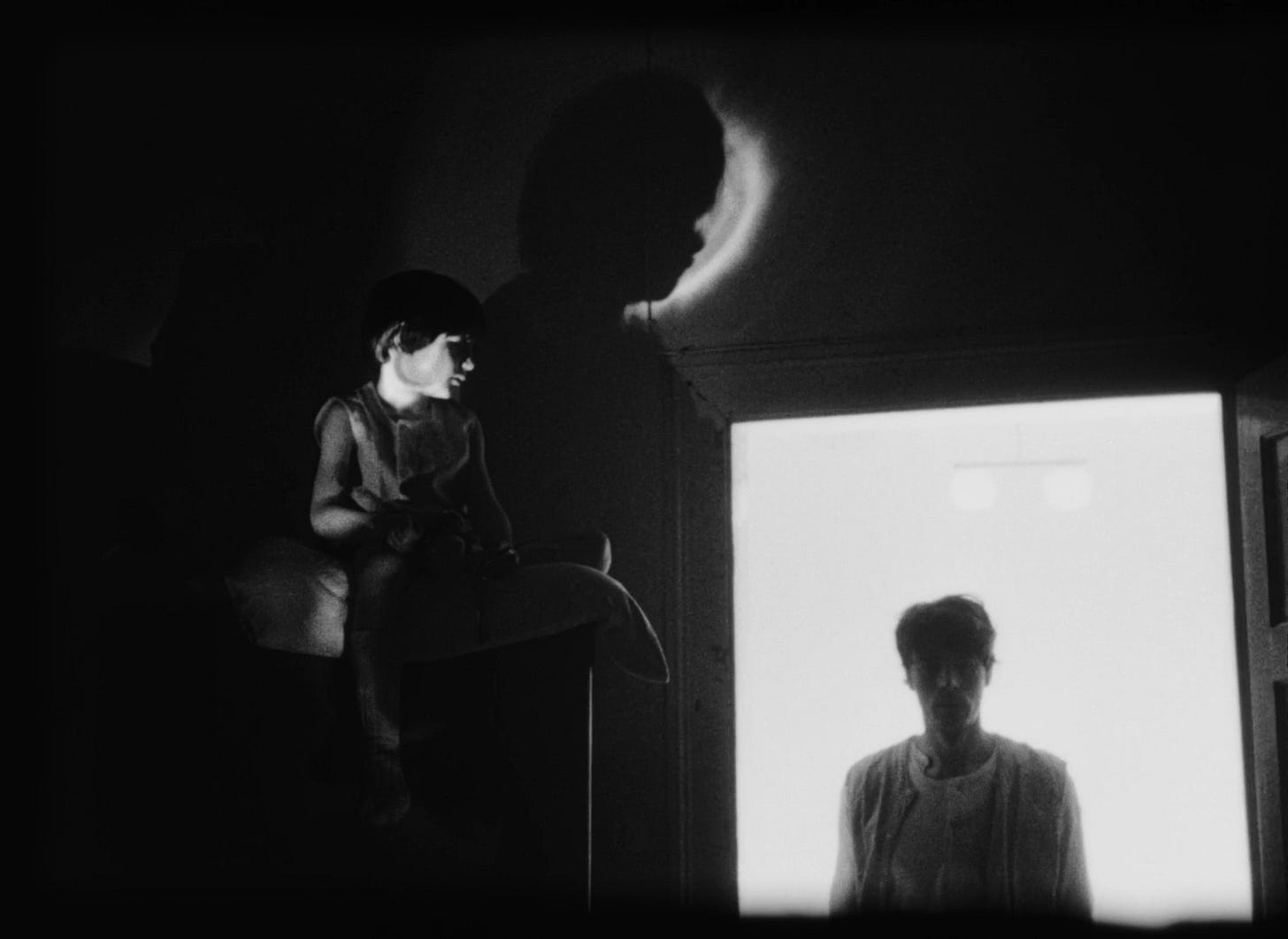

Jason Al-Taan, who shot the cover.

Oh man, Jason is a really incredible, beautiful person in general. I really took a leap of faith with him because I hate having my picture taken. It actually fills me with seriously paralyzing anxiety—it’s one of my biggest anxieties, and it’s really difficult for me. Even having an idea to take a photo of myself, again, it’s parading this vehicle for me to work through all my bullshit. I was really grateful to work with someone who had a real vision for what the cover could be because I really didn’t want it to come from me. He really just took the bull by the horns and was also extremely gentle with me in ways that I really appreciated because I would have just crumbled otherwise.

How did he present the concept of the cover to you?

He basically just mentioned it, exactly as it looks (laughs). He had this vision of this waterfall and wanted it to feel like it was moving even though it was a still image. He had done some research about potential locations and it worked out.

Where was it shot?

I’m forgetting the name of the waterfall, but it was in Pennsylvania. We had to hop a fence and scale down a mountain, and that was actually the last photo on the roll before it was almost pitch-black. Pretty scary.

Last but not least, your saxophonist and synthesist Ben Chapoteau-Katz.

What is there not to say about Ben Katz? Ben keeps me alive! (laughter). He is the glue of the project in so many ways. When we first met, which is a whole story in and of itself, he would call me every single day to talk about the music and ways that he felt like he could play it live, the instrumentation we should be using, what people we should be playing with. He’s always been the glue, and with this record in particular, he was the middle ground between Andrew and I. My collaborations with Andrew work because he is very hi-fi and knows all the techniques and is extremely skilled, and all I have is my intuition—Ben has both. He knows ways to tell me “no” that won’t completely crumble me, and can mediate between my ideas and Andrew’s, which often come from very different places. That meeting in the middle is what makes the record sound the way that it does, and Ben was able to make that happen in a really beautiful way.

As we touched on earlier, he’s kind of the secret star of this thing. I’ve expressed this to him.

It’s true. He always jokes, “I didn’t do anything!” But he did a lot. He’s the secret sauce—or the “special sauce,” rather. That’s the credit that he demanded to have on the record, and it’s true.

Is there anyone else I’m missing you want to sing the praises of?

I mean, everybody on the record really. Jake Sherman, also, who plays organ and other things with keys on the record—I don’t know. It’s a big deal for me to be collaborating on this record with people, because I’m very shy. I wanted to try to collaborate with more people this time around, but it also took a lot for me to try to do that. I was really grateful to be able to assemble a community around my record, which I didn’t do as much the first time around, and I hope can be another theme going forward.

Any parting words in terms of what you want people to hear when they sit with Fatigue?

Not at all! I’m just excited for people to hear it and come to me with whatever they think about it.

It’s happening so soon.

It’s so soon! (laughter). It means a lot to me that you care about the record the way that you do. You know I care a lot about your music.

The feeling is totally mutual. I’ll see you at Elsewhere this summer!

Yes! I can’t wait.

Don’t be a stranger.

You too.

L’Rain’s Fatigue can be purchased at Bandcamp and the Mexican Summer website.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Lucia Nimcová & Sholto Dobie - DILO (Mappa, 2021)

Press Release info: I first discovered khroniky – Ukranian folk songs – in the Highlands of Scotland. I was watching a screening of Bajka, a mesmerising documentary made by the filmmaker Lucia Nimcová and sound artist Sholto Dobie. I knew nothing about these ballads beforehand, but I was fascinated by these odd, beautiful songs, especially the easy way in which they mixed misery and levity, where gentle melodies blend with tales of dark violence. The folk songs describe hardship, murder, torture, death in gulags, heavy drinking, outsmarting men, love affairs. But they’re often very funny too – many of the songs make fun of marriage, and there’s an amazing subcategory of khroniky songs called potka (vagina) songs.

Determined that these rich, nuanced, unique songs shouldn’t be forgotten, she decided to record them. Over two years, Lucia, joined by experimental musician Sholto Dobie, visited Rusyn villages high in the Carpathian mountains to rediscover the songs and make the documentary. It was at the beginning of war breaking out in Ukraine in 2014.

Purchase DILO at Bandcamp.

Gil Sansón: Folk music, more often than not, has a difficult relationship with institutions—there tend to be preconceived notions of music that leads to something getting sanitized. In any case, the availability of recording technology has enabled a generation of artists who are as interested in song as they are in the work of composers like Luc Ferrari, who blur the distinction between life and art in their work. DILO is an attempt not so much to exhaustively document the songs of an ethnic minority in Ukraine but rather to reconnect with songs that are imprinted as magical memories from childhood, like the songs you hear your grandma singing.

The production of this album straddles the line between aural documentation, one in which emotional resonances seems to be the foundation, and the creative editing that takes matters into concrète musique and sound-art territories (the third track, “Sing for myself,” brings to mind Ferrari’s Presque Rien), but there’s a clear sobriety of intent in the album that ensures that the focus remains on the songs and the voices of the people singing them. There’s no attempt to embellish the sound, no polishing; the artists know and trust the power of the originals and wisely choose not to include any extraneous element apart from the material recorded at the source, vocal, instrumental or otherwise (you get plenty of rain, sound of machinery, folks going on about their businesses, chatting).

These songs are played by locals in the same way folk music is often played, as part of everyday life, right in the middle of farming occupations, cooking, cleaning. The music is as integral a part of the environment as the trees and the local fauna. The inclusion of spoken interludes among the songs fills in the images we imagine as listeners, and they serve as reminders of how music and speech are closely related in folk music. A folk song would often need no more than a cappella singing to convey its essential characteristics, and here we hear them sung by Nimcová, by local folk, sometimes with a hurdy-gurdy to provide a backing drone. Part of the pleasure here is trying to figure out the meaning of the spoken word passages—they sound like the type of stories you hear from your grandparents, the treasure trove that comes with a long life of memories.

[8]

Evan Welsh: As someone who is almost always listening to music, it can admittedly sometimes feel like a barrier from the space I’m in. Obviously, it’s nice to isolate oneself from the subway or bus or screaming neighbors and get lost in a song or an album, but it can come at the cost of presence.

Field recording projects like this are most successful to me when they serve as a reminder to focus on my surroundings beyond a simple acknowledgement of them. DILO was most impactful for me when I would play it while walking through various neighborhoods—the ambient sounds of these isolated villages in the Carpathian mountains soundtracked and bled into the metropolitan landscape much more naturally than I would’ve ever expected. My atmosphere, the work and music and conversation that encompassed me, while drastically different than the one Nimcovà and Dobie document, felt like a continuation of their ethnographic work. Even when the album was over and I took out my earbuds, it felt as though it had never actually ended. There is, of course, specificity in these noises and folk songs, to the geography and to the people, but It also reminds that these distinct sounds are present everywhere, if you take enough time to listen.

[8]

Mark Cutler: Less an album than a kind of fiction, set in a rumbling, rattling landscape, where it is always raining. The actual folk music largely takes a backseat to a series of surround-sound field recordings intended to convey—even without the album’s extensive collage of photographs, notes and excerpts—the social and sonic climate in which these songs would be sung. Generally, I don’t go in for music that comes with a lot of homework. In this case, however, I’m going to skip rehashing the album’s genesis and structure, and urge you instead just to scroll back up to the Bandcamp link and read about it yourself. Then, listen.

[9]

Maxie Younger: DILO does little over the course of 40 minutes to justify its existence in concert with the extant works of Lucia Nimcová and Sholto Dobie: as an exploration of khroniky, it pales in comparison to Bajka, their 2017 film, which puts faces to the lilting, bawdy and frequently haunting folksong that the two artists have devoted themselves to for seven years. Staged and slightly precious as those shots can be, they do a far superior job of placing this tradition in an immediate, visceral context with its community; by comparison, DILO devotes a frustrating amount of its runtime to elements removed from its supposed focus, wading blearily through staid, layered field recordings for minutes at a time before settling into the meat of the album. When these passages of verse do finally arrive in the mix, they’re entrancing, almost in the same way that generative art or modular synthesis can be: each singer is propelled by the live-wire, mercurial magic of improvisation, pivoting from subject to subject on a dime, lingering on small details, caressing each phrase. The wonder of these aural moments begs for better visual accompaniment than the paltry liner notes, though, and DILO just isn’t rewarding as an ethnography when compared to its predecessors. In a vacuum, it has all the potential in the world to be engrossing; but, in context, it suffers.

[3]

Samuel McLemore: A lot of talk about ethnography is thrown around in the liner notes here, about how authentic and true this album is to the rural folk who are its subject, and how accurately their songs were able to be captured. One might then be surprised at how long it takes after you press play on DILO to hear what could be reasonably called a “folk song” as much of the total runtime is given over to field recordings of cows in a pasture or clinking pans in a kitchen instead of instruments being played and voices raised in harmony. But consider what Sam Hinton wrote in his classic The Singer of Folk Songs and His Conscience:

folk music is not so much a body of art as it is a process, an attitude, and a way of life; its distinguishing features lie not within the songs themselves, but in the relations of those songs to a folk culture.

It’s in this light that Lucia Nimcová and Sholto Dobie’s efforts to make a more holistically complete form of ethnographic album fall into place. If “folk music” is not a type of composition, but instead a description of the kind of relationship between a song and its place and time, then how could the more typical kind of album made from ethnographic field recordings, which restrict themselves to only presenting the music, not be missing half the picture?

In addition to the more academic concerns I’ve just outlined, obvious attention has been placed towards perfecting the aesthetic qualities of these recordings and matching them together into a coherent musical montage, a full mental map of the Carpathian village it was recorded in. When considered as sound art or folk music (it is both) DILO stands as a high watermark for this year, and when thought of as an attempt to fill in the other half of a missing picture my admiration for it only grows.

[9]

Matthew LaBarbera: There is a quote, typically attributed to Amadou Hampâté Bâ, that goes something like this: “When an elder dies, a library burns to the ground.” In the ripening of my days, I realize more and more the atrabilious truth of the statement. There is a real potency to a long life. It constitutes a pattern of experience that can exist nowhere else but in the heart and mind of a person, and therein lies its vulnerability to oblivion. Presence dissolves into absence. We eventually lose the ability to speak of what this lack once was, left only to contend with, however partially, the tears. We inherit these lacunae. In ways perceptible and not, these silences speak to us in languages we can hardly understand and of places we can hardly remember. In full recognition of this, dolefulness becomes the historian’s proper mood.

An accounting of what was lost—what we are currently, before our eyes, losing—is the least that can be done. There is no going back, but we can try to arm ourselves with the capacity to remember. Cycles small and large calendared into a lost future. Try to imagine the sounds of geese, cows, dogs, and flies; the old motorcycle engine driving a pump; the houses staggered in the mud; the chiming of bells and voices; the handiwork of the carpenter; the fruit trees and scenes of life playing out beneath them; the hardships endured and abuses suffered; the resistances waged; the shape of the land as it pulls away from the village and towards the world at large.

We should have no truck with any romantic fetishization of ruins or notion of noble extinction. Empathy here is an extension of our aversion to loss, the melancholic countenancing of what it really means for a strand to be severed. We can make space for revenants to resurface so that they might sing through the silences.

It becomes difficult to continue here because I am not even sure if I can get to where I want to go. For in this instance, on the topic of Lucia Nimcová & Sholto Dobie’s DILO, nothing of it belongs to me, but I still, in instinct and intellect, feel moved as if by some heliotropism, a tendril whispering out through empty space. I am caught at an aporia, a chasm whose void is perhaps more meaningful than even the far side it prevents me from reaching. In music, this effect is one well described by Henry Flynt: “The best of the musical languages which embody the tradition of experience of autochthonous communities are uniquely valuable for their specificity of sentiment and passion, their holistic engagement, their expression of extra-ordinary and elevated human possibilities. They transmit something which I am not willing to ignore.”

So, what is this thing in DILO that I am not willing to ignore? I don’t know. Even that remains occluded. I find a bit of a clue in Svetlana Boym and her discussion of the two primary tendencies of nostalgia, restorative and reflective. She writes, “If restorative nostalgia ends up restructuring emblems and rituals of home and homeland in an attempt to conquer and spatialize time, reflective nostalgia cherishes shattered fragments of memory and temporalizes space. Restorative nostalgia takes itself dead seriously. Reflective nostalgia, on the other hand, can be ironic and humorous. It reveals that longing and critical thinking are not opposed to one another, as affective memories do not absolve one from compassion, judgement, or critical reflection.” Reflective nostalgia understands the nature of legacy, and its optimism rests in the conviction that it can, in some way, resuscitate what was actually there and actually good.

I am reminded of an excellent release from a few years ago. It too is the synthesis of a journey to the realm of folk, documenting the regional music of Polesie instead of Carpathian Ruthenia. Likewise, it is a duo effort that does not seek to reinstall some static vision of a people and their place, but, to borrow from Boym, practice a poethics. Oj borom, borom forms something of a chiral pair with DILO, an incredible alignment of intent and effect that cannot be reduced to mere equivalence. There is a soaring quality to the performances of Bikont and Wójciński, an attempt to scrape the roof of the world driven by spirit of Polesian song. At the opposite, yet totally complementary, end of the spectrum we have the surreal veridicality of Nimcová and Dobie’s approach to.

I am reluctant to say too much more because, ultimately, the entire point of work such as this is to speak for itself, to let the voices within have the authority here. Sensitivity and patience were the means by which DILO was constructed, and they are useful companions for listeners as well. As a document, it is beautiful, but as an ethic it is all the more necessary. It is worth it. I hope it inspires its listeners to seek out voices that sing old songs and speak of old places. Lives lived have a value beyond number, and we would do well to not merely recognize that fact but to live it out fully for ourselves. From the liner notes:

Perhaps it’s that you can’t go back in time.

but you can return to the scenes of love of a crime,

of happiness, and of fateful decision.

the places are what remain.

or what you can possess, and in the end, what possess you.

[8]

Average: [7.50]

Remko Scha - Guitar Mural 1 featuring The Machines (Taal Beeld Geluid, 1982; Black Truffle, 2021 Reissue)

Press Release info: Guitar Mural 1 documents an installation of Scha’s mechanical guitar ensemble The Machines held at a Groningen gallery space in 1982. Five electric guitars hang from the wall, their strings sounded by rotating rubber strings and a sabre saw controlled by a mechanical apparatus, as well as four ropes criss-crossing the five instruments on the wall. Once the mechanism was set up, Scha’s only intervention was to vary the speed at which it operated. Where Machine Guitars presents short excerpts clearly distinguished by rhythmic and timbral variation, here we are confronted with four enormous side-long slabs of percussive string attack and the resulting clouds of harmonics.

Variation is minimal across the duration of each side, making for a sculptural listening experience, as if we are patiently examining each facet of a static object. But significant variety exists between the four sides, each of which shows off a different facet of what The Machines were capable of. The first two excerpts feature open strings sounded at rapid tempos, dissolving the percussive attack into a continuous stream of sound reminiscent of Charlemagne Palestine’s ‘strumming’ technique. On the third side, the strings are partly muted and the tempo slightly lowered, resulting in layers of relentlessly chugging rhythm somewhere between an ensemble of hand drums and an early Velvet Underground bootleg. On the fourth side, havoc breaks loose in percussive waves of asynchronous repetition that bring Scha’s sound world close to that of another pioneer experiment in musical mechanisation, the Solar Music of Joe Jones.

Purchase Guitar Mural 1 at Bandcamp, Forced Exposure, and Kompakt.

Mark Cutler: Remko Scha’s Machine Guitars came out in 1982, and soon became a classic of installation music. Guitar Mural 1 was issued the same year, as one of just two cassettes on Felix Hess’s short-lived Taal Beeld Geluid label, and has remained largely unknown and unavailable ever since. Machine Guitars takes the listener through six relatively simple setups involving at most two guitars, with each recording lasting about three to five minutes. By contrast, Guitar Mural 1 features five guitars in a rather elaborate array, and the recordings are consequently permitted to stretch out past the fifteen-minute mark.

I presume the title refers to the physical arrangement of the guitars across one wall of a gallery, but it remains apt to the experience of listening to these recordings in the year 2021. Each track feels like one of those vast, expressionist canvases, so large that it must be unstretched and its frame collapsed to fit through the door. The music is layered with highly repetitive elements that evolve slowly or not at all, as well as more chaotic elements which twist, bend, and sputter out. There is time to let one’s attention wander “higher” or “lower” through the mix, to focus in on one specific string or sound, or to zone out entirely.

As an album, Guitar Mural 1 is sequenced from densest to sparsest, giving the vague impression that Scha’s machine is breaking down, or playing itself to death. However, as the maelstrom thins out, actual melodic elements become easier to discern. The final track features a bass string that vacillates periodically between a C and a D♯ throughout its sixteen minutes, causing the mind to begin picking out accidental chords and even fragments of melody. I could almost believe the music were being played not by motors and strings, but by the no-waviest, New Zealandest noise rock band of all time.

[9]

Samuel McLemore: This is something of a relic of a past era, when installation art was still fresh and electric guitars still seemed exciting. In its old fashioned nature, Remko Scha manages to resemble the minimalism of La Monte Young in a sideways manner. While their compositions share the quality of being simultaneously deeply boring and thrillingly immersive, they also share a more substantive link: a conception of music as being an eternal and unceasing flow of energy; an endless pool where the form may change, but the flow of energy remains ever constant. Young pulled this idea from ancient Indian musical thought, where this is a sacred law and guiding principle, and since it offered him an escape from the confines of the Western tradition, he has treated it like a treasure. For Remko Scha, however, this eternal energy is machine-made, not holy in any way, but an inhuman device without feeling or spirit. It’s played on, or expressed through, five electric guitars—an instrument naturally capable of an incredibly wide range of tones and textures—and this relentless force is given a million different expressions, all swirling chaotically around each other as if in a kaleidoscope. The end result is that each track is a staggering wall of sound that’s packed with detail in every moment; it never once slackens its momentum, and is recommended to those who want an overwhelming listening experience.

[8]

Vanessa Ague: The focal point of Remko Scha’s Guitar Mural 1 featuring the Machines is the mechanized electric guitar—guitars that are played by inanimate objects instead of human hands. All Scha controls is the speed at which each guitar is played. Something about this idea inherently feels robotic, stilted, clinical, yet the resulting sound remains surprisingly fluid throughout. Each track strikes its own groove of interlocking rhythmic patterns, using repetition as a vehicle for exploring the subtle shifts and changes that naturally occur as these mechanisms play guitar. The mechanized guitar is also the most compelling part of the album, which sounds about the same as any other piece of minimalist music from the 1960s-1980s. At its best, Guitar Mural transcends each of its prickly detail to send us into that glorious, minimalism-induced, drone-induced trance; at its worst, it sounds unremarkable, relying on its concept to carry its run-of-the-mill sound.

[6]

Gil Sansón: A pioneer in the field of sound art installation, Scha focused on electric guitars that play themselves by way of self-made motors, hung on gallery walls in different configurations depending on the venue. This reissue of the original cassette tape does sound like a not-so-distant relative of no wave artists like Glenn Branca or Sonic Youth, with guitars being treated as drums, detuned, with makeshift capo tunings, and so on. The electric guitar installation is nowadays relatively common (artists like Ruben D’Hers developed the concept to highlight the musical aspect of a massive chord played by the combined sound of all guitars) but it’s always pertinent to acknowledge the originators.

To think of this work as pure music is to miss most of the content. With sound art recordings we are faced with an interesting dilemma: what we hear is not the work but the sound of the work. Unless we’re there, in situ, we won’t fully get the experience of the work. The aforementioned commentary about a possible kinship between the NYC noise rock scene of the time should be taken in light of this characteristic of recordings of sound art. At the same time, sound art has depended from gallery editions, so limited edition cassette and LP recordings have become the de facto medium for documentation when it comes to preserve the work for posterity. In that sense, how well does the sound stands on its own, deprived of the visual and spatial aspect of the original? Does it get closer to music or does it retain its character as sonic sculpture? Hard to say and probably depends on the disposition of the listener. For my money, “Track 2” sounds much more like a sonic sculpture than “Track 1,” but rating the tracks as one would with a music record is beside the point here. This is more like a coffee table book of a renaissance painter than a record to play on social occasions and impress your guests. It’s a reminder that what’s common practice today comes in the wake of trailblazers like Scha.

[7]

Vincent Jenewein: Could you call this historical curiosity dating back to 1982 “proto-techno”? Of course, as a piece of European experimental sound art, it emerged out of an entirely different historical context. Yet, it almost seems like, in his artistic research, Remko Scha had accidently discovered some of the core principles of loop-based dance music. The mechanisms playing the guitars act as a sort of “analog” sequencer, outputting overlaying, polymetric patterns and loop structures that weave in and out themselves in a non-metric fashion. As a result, even though the patterns themselves do not change over the course of a track, there’s a continuous ebb and flow to the looped rhythmic and timbral mosaics. At the end of the first track, it sounds like we’ve ended up in a radically different place than we started, even though nothing has fundamentally changed about the composition—an act of a brain that becomes forced to invent virtual modulations and structural changes when confronted with the inherent violence of bare repetition over prolonged stretches of time.

Additionally, through continuous repetition the harmonic imperfections and complex timbres produced by the sequenced instruments are put in the forefront of the composition—another core principle of techno. As such, despite the fact that the instruments playing here are exclusively acoustic, there’s a stiff, dry, mechanized funk to them that reminds me of mid-1990s Downwards records. “Track 4” even goes into classic Robert Hood territory, with a slightly jazzy, off-kilter alien groove and dissonant, rubbery timbres that resemble a Roland SH-101 riff. Whereas Hood was concerned with giving synthesizers a “human” touch through deft quantized sequencing, Remko Scha makes stringed acoustic instruments sound like synthesizers by rigidly sequencing them through his mechanical machines—form determines content, in both cases.

[7]

Nick Zanca: Machine Guitars saw the late linguistics professor sequencing his motor-powered string music into an LP of eight distinct chapters of kinetic hypnosis, interrupted only by hard cuts. This vivisected, song-length presentation often evokes the stark techno architecture of Regis or Gas—a situation less interested in arc or development than variations in relentless repetition in which the rhythmic foci is permitted to ceaselessly shift gears. When transvalued to side-length structure, however, the illusion of narrative dissolves, and the product can be judged for precisely what it is: pure documentation of sonic sculpture. In a similar meditative vein to the droning ocean of Harry Bertoia’s metal rods, or the Les Paul bird baths built by Céleste Boursier-Mougenot, the lack of human intervention only becomes more perceptible and palpable in a longform mode, and the hour breezes by. The key phrase in the title is “featuring The Machines”—once these sabre saws and automatic limbs are given agency, it’s hard not to hear this as the work of an ensemble, however rigid. To borrow from a favorite Joni line: the “band,” as it were, sounds like typewriters.

[7]

Average: [7.33]

Backxwash - I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES (UglyHag, 2021)

Press Release info: In her upcoming album I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES, Backxwash serves harrowing raps over industrial horrorcore beats. This audio-visual landscape of pain and despair features Backxwash as an empress of chaos on a path of self-destruction. Whereas GOD HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH THIS was a study in mercy, I LIE HERE BURIED Backxwash finds solace in being consumed by her malevolent behaviours.

Purchase I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES at Bandcamp.

Mark Cutler: Here we find Backxwash swapping out the bass pads in her production for crunchy thrash-metal and nu-metal guitar riffs, with additional ’90s nods to glitch and chiptune. The music feels conceptually related to hyperpop in its pilfering from the maligned and neglected genres of the music-industry-gone-by, just with the Korn knob turned up to 10. Like the better hyperpop acts, Backxwash manages to connect all these throwbacks without the music itself sounding dated too much of the time.

That said, the shorter tracks are generally more successful for me. Although all the songs have pretty similar production and lyrics, Backxwash does best when the modest tune and tempo changes allow her to pivot slightly in delivery. By contrast, the two five-minute tracks early in the album’s sequencing feel much longer than they should, plodding along in the same key and at the same pace for their entire durations. One can almost skip randomly around them without really noticing.

Nevertheless, there is some very good material here. Feel free to roll your eyes that the sound-art guy likes the sound-art track, but opener “PURPOSE OF PAIN”—consisting of a single spoken-word sample looped and stretched and doubled over itself—really does show that Backxwash has more ideas than the other nine same-y tracks would indicate. I’m interested to see Backxwash continue to define her own, distinct space in the noise-rap scene.

[6]

Marshall Gu: Industrial music has been absorbed in a lot of underground hip-hop to make heavy-hitting bangers for decades now and, as a result, has become a little passé. Backxwash’s music, however, reclaims the dark machines for her own purposes: expressions of her lived experiences as a queer, Black woman. The beats don’t even try to sound like they are man-made (except the lovely African chant sample at the end of “666 IN LUXAXA”). Instead, they constantly pummel while Backxwash’s flow is pure grit and cold steel. There is no bottled rage here; the anger has boiled up over years of oppression—“My mind’s stuck in a torture chamber” is how the first proper song starts, “My only reason for being locked in submission” is how the second proper song follows—and is now spewing from her mouth. She’s ready to fight, yes, but she’s also ready to be loved and forgiven too, an element that’s missing in a lot of her (male) contemporaries who don’t want love or forgiveness. She even says as much on opener “PURPOSE OF PAIN” which at first seems like a neat trick in its non-segue into “WAIL OF THE BANSHEE” but on further review, “The purpose of pain is to get our attention [and] to request care” seems like her mission statement.

[7]

Maxie Younger: I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES (ILHBWMRAMD, for short; in my head, pronounced “ill-hob-wham-ram-dee”) is at once a more complete and less exciting offering from Backxwash than God Has Nothing To Do With This Leave Him Out Of It. Her rapping is slower, more precise, but not as dynamic: the best lines lie buried among roughage, brilliant nuggets, like the stellar opening to “TERROR PACKETS” (“Where was you at / When I had to trap / Just to pay for my hormones, / Selling white kids mid / Claim it’s from Madrid / But this shit really homegrown”). She summons a vast array of contributors and features around her that are cohesive to a fault, but also feel a little underutilized and scattershot in their overall quality. Sad13 sings a gorgeous hook on “SONGS OF SINNERS” that’s one of the highlights of the project; CLIPPING. pen a brassy, blaring guest beat for “BLOOD IN THE WATER,” which, at less than two minutes in length, reads more as a demo or snippet than a fully realized track; Lauren Bousfield ornaments “IN THY HOLY NAME” with anonymous farts of glitching noise.

It’s a credit to Backxwash’s laser-focused vision as an executive producer that none of these contributions ever threaten to derail ILHBWMRAMD’s momentum, but they don’t quite elevate the work, either. The most difficult part of the project for me to sit with is the muted, pillowy mastering, which sits at odds with the sharp energies radiating from each track; it almost sounds like the songs are muffled by gauze or a thin blanket. There’s a palpable sense here, as there was on God Has Nothing To Do With This Leave Him Out Of It, that Backxwash is straining to reach a vision that’s just slightly out of step with her current skill level: it’s that same thrilling ambition that first drew the eye of the Polaris Prize. ILHBWMRAMD isn’t a step back for her, but it’s not a step forward, either; she’s caught on a treadmill.

[6]

Samuel McLemore: Most of the specific aesthetic choices on I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES run counter to my usual taste, with a lot of the album tapping into the lineage of villain rap, Three 6 Mafia, Death Grips, etc. It’s a sound that’s waxed and waned in popularity for decades now, and not one that I think has much creative gas left in its tank. While writing the previous sentence I looked up Backxwash’s first album, God Has Nothing To Do With This Leave Him Out Of It, and learned that it was taken off of most streaming platforms because of sample clearance issues and a little lightbulb went off in my head. I don’t know if Backxwash had any similar problems when producing I LIE HERE BURIED WITH MY RINGS AND MY DRESSES, but a lot of the beats do have the kind of clumsiness to them that you hear when people who are used to creating with samples have to struggle to avoid odious copyright strikes.

The chief strength of this album is in how it inverts the commonplace expectations and narratives of the genre: it is striking how even though the details have changed, the anger and pain of an individual struggling to live in a world that is violent and unjust remains nearly identical to its forebears. Every flaw in pacing or production is now seen in a new, purposeful, light, for how could an album that uses the same sounds to tell a new narrative not have an awkwardness to its effect or a drag to its pace? Any critics that try to label such things a detriment to its overall quality would be simply misguided.

[6]

Gil Sansón: It has taken a while for horrorcore rap to become an established genre, with pioneers like Techno Animal being acknowledged after being misunderstood for decades. I LIE HERE starts deceptively, with an intro that features something akin to the phasing effect of Steve Reich’s It’s Gonna Rain, but it plunges right away into darkness with reckless abandon right after with a sound that mixes the hate of black metal with the slow, doomy beats of drugged lo-fi hip hop.

You’re not supposed to put this on and sit comfortably while checking your emails; this will make you feel alone, scared, and confined. The title track seems to point to a hate crime against a trans person: without examining the lyrics my mind imagines an angry ghost haunting the living with the awful tale of her demise. Sick bass, wraith-like wails, everything distorted to red VU levels—it’s all used to directly attack transphobes, organized religion, macho types in the ghetto. She tackles them all head on, and there’s a very intense presence that’s felt, and no moment for respite; anger, fear, and despair are weaponized and returned back with high interest rate.

Still, there are glimpses of hope in the downright epic “SONGS OF SINNERS,” which has a proper chorus that I wanted to play back right after the song ended. In other tracks you have unsubtle hints at witchery directed against homophobic and racist criminals: “Sometimes the morphine is not enough” she says on “NINE HELLS,” as if the molasses beats and grooves have a self-medicating purpose, and that her anger won’t be contained; she explodes with full force, slugging along with the gloom. I LIE HERE features a voice of righteous anger, an Backxwash is an artist who wants to feel hope, who won’t hide her emotions, who won't accept invisibility. In fact, she’ll make sure you can’t ignore her.

[8]

Average: [6.60]

Thank you for reading the sixty-eighth issue of Tone Glow. Hope you’re the special sauce in someone’s band.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.