Tone Glow 066: Alan Licht

An interview with Alan Licht + our writers panel on Black Midi's 'Cavalcade', Erika de Casier's 'Sensational', and Loraine James's 'Reflection'

Alan Licht

Alan Licht is a writer, musician, and curator based in New York City. He is equally known for his guitar work in the underground rock bands Run On and Love Child and in the experimental groups the Blue Humans and Text of Light. He has released eight solo guitar albums and more than a dozen duo and trio records of improvised music.

I first met Alan Licht after a show in Montreal in 2017, and he agreed to an interview. We met again around a year later, this time at a show at Wonders of Nature in Brooklyn, New York. We did an extended interview after that show, talking about playing with Arthur Lee, Jandek, and the Boredoms, along with many other moments in his career. That interview is finally seeing the light of day thanks to Tone Glow. In advance of its publication I caught up with Alan on May 11, 2021, and talked about some of his current works.

Mike Lumsden: Hi Alan, nice to see you again. I guess the last time we saw each other was in May 2018 in Brooklyn, after you played at Wonders of Nature with Rob Noyes.

Alan Licht: Yeah, I think that was almost exactly three years ago, give or take a week. Rob’s latest record on VDSQ, Arc Minutes, is great. He was already great when I did that show with him and he keeps getting better and better.

During the pandemic you’ve started sharing some archival releases on Bandcamp. I’d like to talk about three of your current or upcoming releases: At the Top of the Stairs, a duo album with Loren Connors at Union Pool (upcoming on Family Vineyard this summer), a solo cassette on Room40 (A Symphony Strikes the Moment You Arrive), and a covers collection on Bandcamp (Three Chords and a Sword). The show with Loren was recorded a few months after our 2018 interview.

That was recorded in November 2018 at Union Pool. Steve Gunn was doing a residency there and asked me and Loren to open. It was the first time anyone had asked us to play in around eight years. It was a little weird to play together after that long a gap, but the audience was watching with rapt attention and seemed really focused on it. We had a good recording of the show and Loren was really keen to have it released.

It took a little convincing for me to get behind it, but when I compared it to some of the recent solo recordings he’s been doing it was really different, even though Loren dominates a bit he’s not doing what he would do on his own, so for that reason I thought it was valid to release. Unlike older shows where I would try to reharmonize what he was doing, that was hard for me to do this time because Loren’s playing has gotten more atonal. It’s like an alien landscape, where you’re trying to take it all in and navigate it at the same time. And I feel like it’s coming from this emotional place that’s hard to put a finger on. It’s not happy, sad, angry, or something simplistic, but maybe it has something to do with the two of us playing together again after such a long time.

The cassette on Room40 has two live recordings, one for shortwave radio and one for guitar, as well as a long interview with Lawrence English.

The shortwave piece was performed in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2009 on a bill with a short-lived trio that Chris Brokaw, Doug McCombs, and Elliott Dicks had, and Major Stars. I’m not sure why I didn’t play guitar. I had a shortwave radio that belonged to my partner Angela Jaeger. This long power ballad came on about three quarters of the way through, and that was just a complete fluke—a peak moment that couldn’t have been better. Keith Fullerton Whitman had recorded it, and I’d wanted to release it for some time.

Lawrence asked me to do a drone cassette. I wasn’t working on any pieces that fit that description, but I’d been going through my archive and finding lots of older recordings. I got into Bandcamp a year ago, at the start of the pandemic. It’s the best internet platform I’ve ever worked with and it’s given me a new way of trying to get these unreleased recordings out there. One-off gigs at Tonic, or a grouping of people that just happened the one time… I realized I had thirty years of unreleased live recordings that were sitting here doing nothing, and it gave me a forum to put them out. So as I was putting stuff on Bandcamp I remembered the show at PA’s and the other piece, which accompanied a piece by the video artist Birgit Rathsmann. I’ve known Lawrence for a long time. When I toured New Zealand with Oren Ambarchi and Tetuzi Akiyama, the first show was in Auckland. Lawrence opened the show and the Dead C headlined.

Three Chords and a Sword, an album of covers released only as a download on Bandcamp, is a kind of personal history, both as a dive into your archive and through the selection of songs and artists for the new recordings.

The Suicide cover (“Rocket USA”) was from an old cassette made on Will Baum’s 4-track. I recorded it one morning in 1988 when I was waiting for the rest of Love Child to show up to my parent’s basement in New Jersey to record our demos.

When I heard the Pere Ubu and Fred Neil covers played on chord organ, I wondered if they came from the same recording as your cover of Captain Beefheart’s “Well” heard on “The Old Victrola” from your solo album Plays Well.

Yeah, those recordings were all from the same show at Cooler in 1996. That was one entire show where I played the chord organ and sang. I also did a medley of “Nightime” by Big Star and “Doesn’t Anyone Love the Dark,” one of my songs that we did in Run On, which almost made it onto this release.

Three of the tracks were recorded on acoustic guitar at home. I was surprised to hear your American Primitive-style take on Van Halen’s “Jump,” though I know you’re a big fan of Eddie.

I thought of it when Eddie passed away last year. I saw an amazing, virtuosic arrangement of the song for acoustic guitar by Mike Dawes, who did it in memoriam of him. I wanted to try something more in the John Fahey guitar soli school. You know, I can’t replicate all the crazy synth lines, which Dawes did, and I wanted to focus on the song’s drone aspect.

“Tom Violence” is in G minor tuning. The midsection in the original is a noise breakdown, which you couldn’t really replicate on an acoustic guitar. Initially I was trying to do a fake flamenco thing, which didn’t really work. Then I remembered Derek Bailey’s Ballads CD, where he starts off playing jazz standards and then spins off into free improv. I started to do an arrangement where I was doing a lot of Derek extended techniques, pinging the strings behind the nut and so on and so forth, but I pulled back from that a little bit and thought more about Robbie Basho. Like you said, the whole album is a personal history, but this track is also, to me, a history of alternate tunings and techniques, from Robbie Basho and Derek Bailey to Sonic Youth, trying to show that lineage which is definitely there.

As far as “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie,” I know the Dylan original from The Bootleg Series. It’s a long poem he only read aloud once, at a concert at Town Hall in 1964, and it always knocked me out. Of course, there’s a zillion Dylan covers out there, but this is one nobody’s ever covered! I liked the idea of doing a covers record but having one track be spoken word. It was recorded at a live show at Tonic, on a bill with the Anomoanon. I also did “Karen Revisited” by Sonic Youth at that show, and “Texas Serenade” by the Gun Club. That’s another example of one of those shows I did where covers were a big part of it, making up maybe half the set. But until now, there’s been hardly any public documentation of this aspect of my live performances.

Thanks, Alan! And thanks again for doing the 2018 interview in the first place, which I’m glad is finally being published [Editor’s Note: The following is the 2018 interview].

I found this Love Child feature in a Vassar College newspaper issue from 1990.

This was in Rebecca [Odes]’s apartment. She had an off-campus apartment where those photos were taken, on Collegeview Avenue. Just barely off-campus. It’s funny, I go back to Poughkeepsie once in a while to rent a car, since it’s cheaper to rent a car up there. I take the train up. So I pass through Poughkeepsie now and then, and it has not changed at all in thirty years. It’s kind of strange, it looks exactly the same. It’s been a while since I’ve been on campus, maybe ten years. When I majored in film, the whole department was in the basement of the chemistry building, but now there’s a whole center for film.

When was the first time the band went to New York?

The first New York show was in October 1989 next door to CBGB—CB’s Record Canteen I think it was called, which was later CBGB 313. Gerard Cosloy was doing a series, Club Noid—I don’t remember if it was monthly or weekly or what—and he asked us to come down and play that. I think I have a flyer for the show somewhere. The other bands were Buffalo Tom and the Go Team, which was Calvin Johnson, Tobi Vail, and Bill Karren, also played at Vassar, which ended up being their last-ever show. We played CB’s proper for the first time in February 1990, which was right when the first single came out.

[Before the single] we recorded a demo, which is what the single is taken from. We didn’t really release it, but we would sell it to people if they sent us five bucks. I sent it to the guy at the fanzine Black to Comm, and he reviewed it for Forced Exposure, much to my surprise.

Did Love Child do a Peel session?

Yes. It was recorded, although from one reference book I saw, it looks like it was never actually broadcast. It was at the very end of our European tour with Codeine which meant it would have been close to Christmas, 1992. But I have a cassette of the recording. There was one otherwise unreleased song, one Moondog song from the 7-inch which became more of an extended jam live, “Asking for It,” which was only on the first 7-inch, and “Slow Me Down.” It was fun and we had a good experience, it was a 48-track studio, probably the biggest studio I’ve ever worked in. Codeine did a session too but they had different engineers working for them. One of them was some guy that had been in Mott the Hoople, who was kind of a drunk, I think, so they were a little less enchanted by their session. Maybe theirs was actually broadcast, or maybe both our sessions ended up slipping between the cracks, who knows.

You mentioned fanzines. I’m sort of a generation removed from this, but I know people are working on collecting and recirculating them. I was wondering about a few fanzines you were connected to, like Crank Automotive by Marc Masters.

He interviewed me for that. I think he’d done an interview with Rudolph Grey before that, who I’d also interviewed, for Black to Comm.

He ended up putting out your album Plays Well later, which is one of my favourites.

The whole fanzine thing—Conflict and Forced Exposure were the ones I liked the best. There were lots of other ones too. Tom Scharpling [who put out the Calvin Johnson Has Ruined Rock for an Entire Generation 7-inch] did a fanzine, 18 Wheeler. A lot of them were pretty snarky, though that term didn’t exist back then. At that time in your life music has a lot to do with forming your identity, or at least you think it does. So it’s partly about the music, and partly about what you think the music represents, and whether or not you want to be aligned with that. It’s not really music journalism as such. It was a very personal take on what was going on. Record reviews, but also live reviews depending on where you were located. These people were going to shows all the time, so if you were in a remote location it was a window on that. It was interesting when, starting with Forced Exposure, some of the faniznes started covering more experimental music, right when my interest was starting to go in that direction.

It seems like within a pretty short period of time, you went from playing in Love Child to playing with a lot of other musicians. You and Loren Connors started playing together in 1993. I read an interview in Popwatch where you talk about some of the live things you’d done in the early nineties, for example playing in King Kong.

Yeah, one show at Maxwell’s. Ken Katkin, who put out the King Kong single as well as the Love Child single and signed us to Homestead, was the one who made a lot of these connections. He was friends with Tim [Harris] and Tara [Key] from Antietam, who were the big Louisville expats up here. And he was friends with David Grubbs. So then he got to know the people in Slint—the lineup of the first King Kong single is actually the same as the original lineup of Slint.

I played with Arthur Lee of Love at that time too. That was through Lyle Hysen from Das Damen, who produced the second Love Child record. At first, Das Damen backed Arthur. The bass player couldn’t do one show in Philadelphia and I filled in on bass. Then the guitar player decided he didn’t want to do it, so I moved to guitar. There were two very short east coast tours.

What was it like playing with Arthur Lee?

When I played bass there was no rehearsal, I just drove down for soundcheck. I think I missed one note at soundcheck. Arthur stopped and turned to Lyle and said, “Does he know the songs?” I said, “I know them,” and didn’t make another mistake. There was one rehearsal in Hoboken with Arthur before the first tour. He left his manager sitting in the car but took all his luggage in with him, because he didn’t trust his manager. He went on this whole monologue for what seemed like thirty minutes. He started off by confusing David Letterman with Medgar Evers, and then asked me to light a joint for him, but it was tied off at both ends. I wish I could go back in time and hear his whole spiel again because it was so off the wall. We were just standing there with our jaws dropped. You always heard he was pretty far-out there and this was proof it wasn’t just mythology or mystique, it was true. We finally got down to business, rehearsed, and went out and played.

We played Maxwell’s a couple of times, and somewhere in Asbury Park called the Fast Lane, which had been a bowling alley first. We played Boston a couple of times, at the Middle East. On the first tour we played at the 9:30 Club in D.C. Lyle’s brother lived in DC. He was videotaping the show and Arthur didn’t like that sort of thing. He would go out into the crowd and confiscate people’s recorders. We saw him go into the crowd and we heard, “No, wait, I’m Lyle’s brother!” and he came back with the recorder. It was off mic, but I heard him say, “They can do it to Nixon, but they can’t do it to me.”

We played D.C. another time at the Black Cat, and all the guys from Fugazi, Ian Svenonius, everybody in that scene was there. For years afterwards, to those guys, I was “the guy that played with Arthur Lee.” Ian MacKaye had come to see Love Child and heckled us. It was a last-minute thing at D.C. Space where we were substituting for a band that dropped off the bill. We got there and there was no sign we were playing, every poster had the other band and not us. I asked the audience if they knew we were playing. Everyone said no except Ian who said, “Stop bellyaching” (laughter). But then at the Arthur Lee thing he was really complimentary.

We played songs from the first three albums, which I was the most familiar with, a couple songs from Four Sail and a couple later ones. Lyle actually sent me a recording of one of the Maxwell’s shows recently and I was surprised at how short it is. It’s only a half hour and we played “7 and 7 Is” twice in the beginning! Either he couldn’t hear himself in the monitor the first time, or his voice wasn’t in the PA. He said, “Let’s do it again.”

I heard that you played with the Styrenes around the same time.

They were on Homestead too. Again it was Ken Katkin who signed them, so he got us together. I knew about them from Black to Comm. And actually Fred Lonberg-Holm, who moved to Chicago and became much better known as a free jazz cellist, was also playing with the Styrenes at those gigs. I met him then and did a couple of other gigs with Fred as a duo, and once as a quartet with Tom Surgal and Lin Culbertson, who play now as White Out. Tom was the guy who played drums in Blue Humans—those shows are what make up the Max Factory album that came out on Ecstatic Yod. Fred worked with Paul Marotta of the Styrenes at the record label New World back then. Paul’s son was playing drums.

Was Anton Fier in the band at that point?

He was long gone, never in the band after they left Cleveland. But I got to know Anton after that because he mixed the Gerry Miles record I did with Connie Burg which came out on Atavistic. And a few years after that he worked the door at Tonic. That’s when I got to know him the best. The last show I played at Tonic, as one the final nights of the club, was a trio with Anton and Smokey Hormel.

I’ve read a little about that record Gerry Miles. Did you keep playing with Connie Burg after that record?

Not really. We used to just meet every week and they had access to this church in Chelsea, and that’s where the organ was. We’d just go and improvise stuff. It was with Melissa Weaver, a friend of Connie’s who lived across the street from her, which was just a block away from the church. Interestingly enough, last year there I saw a concert, a Maryanne Amacher piece for two pianos, and it was held in the same church. I hadn’t been inside the church in twenty years. It was interesting to go there and see this concert in a space where I’d played but never seen any music performed. I didn’t see the organ there anymore. Maybe they got rid of it, it wasn’t built into the structure—it was a small organ right on the pulpit. [Editor’s Note: The Amacher concert has since been released on CD via Blank Forms, and is titled Petra.]

You also played on Tara Key’s solo record, Bourbon County.

Yes, just on one track. I have a vague recollection of Antietam doing a cover of Love Child’s “Know It’s Alright” that I played on, maybe part of the same recording session for Tara’s record at Wharton Tiers’s studio. Ken Katkin would get us on bills with Antietam. I’d seen the Babylon Dance Band [Tim and Tara’s pre-Antietam band] reunion show at Maxwell’s with Ken. They played Vassar with Antietam and Love Child. The Babylon Dance Band were awesome, one of the best bands ever.

You opened for the Boredoms at Maxwell’s in ‘93 or ‘94?

I think I played some of the Sink the Aging Process stuff for that, “Bettie Page,” and the guitar cable buzz thing that’s on the Calvin Johnson single. I also saw them at Roseland, opening for Sonic Youth.

I’ve seen some footage from that tour. It’s crazy to watch them on stage in that era.

They were amazing. I should watch that since I don’t have a really clear memory. I remember seeing them at CBGB in 1999 or 2000. Even that was a pretty incredible show.

You later played drums with the Boredoms at 77 Boa Drum. How did you come to be part of that?

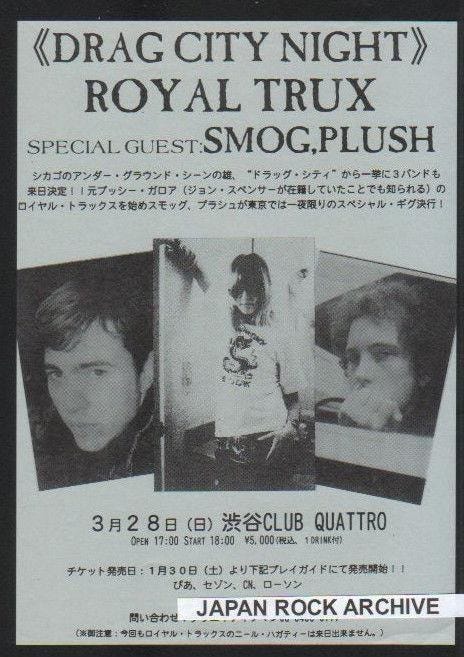

It was through Hisham Bharoocha, who had been in Black Dice at one point, and in Lightning Bolt really early on. I knew him more through Tonic where he’d play solo sometimes as Soft Circle. The other connection there was his brother, Hashim. He worked for this company in Tokyo that organized the Drag City package tour I was on, playing in Royal Trux and Plush. So I met Hashim through that and Hisham through Tonic, although he mentioned that Hashim was his brother when we first met. Basically, the Boredoms put him in charge of getting seventy-seven drummers, so he was asking a lot of people if they wanted to play.

I’d played drums in Love Child, but didn’t realize I was going to be playing a full kit for the Boredoms show. I said yes figuring it would be some kind of free-for-all where I could just tap on a tambourine. Well, it became clear I’d have to play a real drum kit, and I hadn’t owned a drum kit in fifteen years. I showed up that morning and there were fifty drummers all warming up at the same time. I remember saying to David Grubbs and Chris Brokaw, “Well, I’ve successfully re-mastered the three beats I knew when I was playing drums in Love Child.” The person playing on my right was Sadie Laska. She’s in that band I.U.D. with Lizzi Bougatsos from Gang Gang Dance. You would kind of copy what the person next to you was doing, everyone would slowly join in on the beat, then Yoshimi would change the beat and it would spiral out. It was amazing but it was also tiring. The concert was about 70 minutes, I think it was the longest I’d ever sat behind a drum kit for a concert.

What was that show like as a listener as well as a performer?

I was surprised at how good it sounded. Outdoors, sound tends to echo or otherwise get lost, and part of what made it work, I think, was the park being situated between the two bridges, these two borders that closed in the sound. I remember seeing Glenn Branca’s piece for one hundred guitars at the World Trade Center in 2000, and the drums were bouncing all over the place.

77 Boa Drum reminded me a little of when I played Rhys Chatham’s “Guitar Trio.” Everybody was looking for Rhys for clues as to when to add a note, because you start off playing the low E string, then you add the 5th, 4th string, the full chord, and then you start over again. It’s all about overtones. Even last night [at Wonders of Nature] when I was moving up and down the neck, that’s kind of a Rhys thing to do, to generate different overtones on different parts of the fretboard.

I saw a reference to a show early 2000s billed as Alan Licht & the Prix with Chris Brokaw and Doug McCombs.

And Elliot Dicks, who’s a sound engineer. Those guys had a band for a while, a trio. I think they were playing Tonic. I had some songs and asked them to be my backup band.

Was that material ever recorded?

I have recordings of those concerts in my own archive but they were never released.

You played other times with Doug McCombs.

I’m on one Brokeback record. I just overdubbed an e-bow part on one track. And I played two live shows with Brokeback, in New York and Boston, with a cool lineup: Chad Taylor playing drums, Brokaw, and James McNew playing bass at the New York show and Noel Kupersmith playing bass at the Boston show. I met Doug in the Love Child era, because Eleventh Dream Day’s manager was also Love Child’s lawyer. Doug was really good friends with Rick Brown and Sue Garner so I got to know him better in the Run On days. Run On toured with Tortoise, recorded with McEntire when his studio was still in Tortoise’s loft, and then stayed in Tortoise’s loft when we recorded our second album with Casey Rice, who was their live engineer. There was a lot of contact with those guys back then.

I knew Chris Brokaw from when he was in Codeine, because Love Child and Codeine played together quite a bit. Chris was out of the band by the time the two bands toured Europe together in 1992. He was playing in Come at that point. I still stay in touch with Chris. The show I played before the Montreal show you saw in 2017 was me, Chris, and Bill Nace all doing solo sets in Northampton, Massachusetts.

You mentioned some Chicago musicians. When you and Loren made Hoffman Estates, did you already know some of the Chicago people who played on that record?

It was mostly through Jim O’Rourke. I knew Rick Rizzo, from Eleventh Dream Day, and had met Kevin Drumm before, through Jim, but most of those people I was meeting for the first time at that session. A lot of them I’d at least heard of. Rob Mazurek was a little more affiliated with Tortoise, with Isotope 217, but the rest were more from the Chicago free jazz scene.

I was wondering about that time in your life. I thought about Hoffman Estates as a fulcrum, with Run On and Love Child coming before, and new directions in experimental music after.

In a way that record followed the Blue Humans, it sort of was doing that idea with a much bigger ensemble. It was also different from the duo stuff with Loren. There are tracks on the record that are more free jazz-oriented, and there I was the featured guitarist. I don’t think Loren even played on those. Then, there are some where the two of us are playing together. Those were thinking more about electric Miles Davis as a reference point.

Jim was on a hot streak as a producer then, and his own records were turning heads. Drag City was a great label. I’d actually met Dan Koretzky just as he was starting Drag City at a New Year’s party 1989/1990 with friends from Vassar, one of whom had gone to high school with Dan and Rian Murphy. Dan had done a fanzine called Travelin’ Fist, pre-Drag City, and the Black to Comm guy had sent me a copy. When I met him, I was like, “Hey, are you the guy that did Travelin’ Fist?” I’m probably the first and last person that’s said that upon meeting him.

But that record sort of gave me a second lease on life after Run On broke up, which had been a big disappointment. I really didn’t want to do another indie rock band at that point, and Hoffman Estates was such a positive experience that it really emboldened me to keep making music.

ML: I saw a reference to a show for Hoffman Estates at Tonic. How did that come together?

AL: Yeah, it was one gig. It was Ken Vandermark, Rob Mazurek, Chad Taylor on drums, Joshua Abrams on bass, Jim, me, and Loren. I think Ken, Josh, and Rob were in town for another show. That was a really good gig. I wish there was a recording, it would be fun to hear.

I love Rob Mazurek’s playing on the record, from the first note he hits.

I love Rob’s playing too, and we got along really well. When we toured Japan—I was playing with Papa M and he was in Jim O’Rourke’s band—I got to know him well, and ended up playing in his band Mandarin Movie, which made one record.

Was the Japan tour Royal Trux, Papa M, and Jim O’Rourke?

No, there were two different tours. Royal Trux, Plush, and Bill Callahan solo was the first one, in 1999. The other was 2000, the double bill of Papa M and Jim O’Rourke’s band. It’s funny, just this week on Instagram David Pajo posted a picture of Aerial M playing this Drag City New Year’s Eve concert and he was trying to remember when it was. I thought it had to be 1998 going into 1999 because that was when he first asked me if I’d be interested in touring. We were all hanging out the next day when he asked if I’d be interested in playing together. It was November 1999 that I went on tour in the US with Papa M. Part of that was opening for Stereolab, which was wonderful, I loved their music and they were great people.

They had come to Chicago to record Dots and Loops with John McEntire.

And Stereolab put out one Tortoise 12-inch [“Gamera” b/w ”Cliff Dweller Society”] on their label, Duophonic, which was one of my favourite Tortoise recordings back then. Maybe they liked Slint, too, but they definitely loved Dave Pajo. Dave had played bass in Stereolab at one point, touring, so he had a real connection.

I didn’t know you’d played with David Pajo often, though I’ve heard you on Papa M’s “Turn Turn Turn.”

That’s actually kind of a mellow version. We did it at someone’s house in Seattle, a guy from Rex. We set up in his living room and recorded that on a day off on tour. It’s cut off because I think he literally ran out of tape after sixteen minutes. We were kind of building up, though at sixteen minutes long, I think we were being pretty leisurely about it to begin with. There are one or two full concerts from the 1999 tour on YouTube.

Back to touring with Royal Trux.

I was stepping in for Neil Hagerty. He wouldn’t go to Japan because he wouldn’t fly. Drag City worked it out so Plush and Royal Trux shared personnel. In Plush, I was playing bass, and in Royal Trux, I was playing guitar. Rian Murphy played drums in Plush and then he was co-singing with Jennifer Herrema in Royal Trux. And Mike Jorgenson, who’s in Wilco now, was playing “fake Mellotron” in Plush—keyboards also, but mainly fake Mellotron—and bass in Royal Trux. Mike was a young guy in Chicago at that point. He and his best friend had just moved there from South Jersey, and his friend was working in the shipping department at Drag City, so that was his “in” to get on the tour.

I went to Chicago for a week to rehearse and we would have back-to-back rehearsals every day. The Plush songs are pretty complex and I never really learned them all properly. Drag City gave me one fairly murky live tape in advance where you couldn’t really make out the bass lines, and it was largely the material from the More You Becomes You album, which is all solo piano and vocals, so there are no bass parts on the record. I had to guess what to play. Liam [Hayes, of Plush] was reasonably helpful. We learned something like ninety minutes of material even though we were only supposed to play sixty minute sets. We did two covers which were pretty fun. One was “Atlantis” by Donovan. The other was “Witchi-Tai-To” by Jim Pepper, based on the Harpers Bizarre version, which was great, it fit in so well with Liam’s songs. I wish we had recorded that. It was just a lot of material to try to get under my fingers in a short period of time.

Royal Trux was the opposite. The songs were all really simple and I learned the entire set in the first twenty minutes the first day of rehearsals. The rest of the time was spent practicing set dynamics, as specified, quite expertly, by Jennifer. I didn’t know what to expect from her, since she and Neil were such a team, but she had a very clear idea of how the shows should be paced and what the interaction onstage should be like. She was also a very down-to-earth person.

There was a show I saw a reference to which I was curious about—a Nick Drake birthday show in 1999 with Bridget St John and Robert Forster?

I played solo. That was organized by Gail O’Hara of Chickfactor magazine. She would do these shows at this downstairs club called Fez once in a while. For the Nick Drake thing I think I covered “River Man,” playing through one of those Line 6 delay pedals with this setting that eliminated the cutoff, so everything would kind of fade in. It was fun to do.

There was another tribute show called Blue Monday, where the theme was “blue” and you had to cover a song with blue in the title. For that one I was with Eszter Balint, we did a slow version of “Blue Moon of Kentucky.”

Last night we talked a little about the Jandek show in Glasgow, released as Glasgow Sunday 2005. You and Loren Connors both played with him, but not all together at that show. Then you and Loren also recorded a duo album around the same time in Glasgow.

At the same festival, it would have been the day before the unannounced set with Jandek. But it’s not an album, it’s just an excerpt from our set at the festival that Loren put on his album The Hymn of the North Star. Jandek had played in New York and Loren was playing in the band, and Loren and I opened the New York show. He really liked our duo. That New York show was set up by the organizer of the Glasgow festival, Barry Esson. Jandek did his own show at the festival too, a trio with Richard Youngs and Alex Neilson. Our show together was on the Sunday afternoon. First, it was Loren playing guitar and Jandek reciting this story, not singing it. He said it was a science fiction story, and that the instrumental set he played after, with me and Heather Leigh, was supposed to represent the nightmare the protagonist in the story was having. He played drums for our half of the set. He had worked out this one beat he was going to play over and over again, and his only instruction to me and Heather was, “Play aggressive.” I played Blue Humans-style and Heather did her thing on pedal steel, and vocalizing too. She hit the ground running and I was expecting it to build up a little first. It was exciting.

At that festival, we met David Dove, who was there with Pauline Oliveros. He was based in Houston, was putting on concerts, and invited us down. We played in this Quaker meeting house that James Turrell had done a sky space for. Very cool. Jandek took Loren to see the Rothko Chapel. Loren’s a huge Rothko fan and had never been. I didn’t go because I’d already visited the chapel on that tour that the Pacific Ocean did with Bill Callahan a couple of years earlier. When the tour hit Houston, we were getting a ride to the place we were staying after the gig. I said that I’d love to see Rothko Chapel while we’re in Houston, and our host said, it’s literally across the street from the house, so I walked over the next morning. Loren and I played our set and Jandek, unannounced, sat in for the encore, playing bass.

Did you see Jandek again after that?

I organized another show for him in NY in the latter days of Tonic, at the Abrams Art Centre, where we were presenting bigger shows. I got Pete Nolan from Magik Markers to play drums and Tim Foljahn from Two Dollar Guitar to play bass. I haven’t had much contact with him since. It’s funny how I have some sort of connection to so much of the music they’re playing in this café.

I know—the Modern Lovers, Television, Stereolab…

Yeah, Television, because I played with Tom Verlaine and Billy Ficca. Modern Lovers, I played with Ernie Brooks [for Guitar Trio], and actually I played with Ernie and Billy with Gary Lucas once, at Tonic. Stereolab, we would actually go up and jam with them on “Super-Electric” at the end of the shows when I toured with Papa M.

Lee Ranaldo is one of your longest-running collaborators. Was Text of Light the first thing you did together? How did you meet?

I don’t have a clear memory of when I met him. The first gig I ever did in New York was playing with Rudolph as part of Thurston Moore’s Rock and Roll Circus at the Knitting Factory, and Lee was at that gig. The drummer was David Linton, who was Lee’s friend and onetime bandmate [in the Flucts] in their college days. In the Blue Humans I got to know Thurston better, because he produced the records and put them out, and would play with us onstage sometimes, if he was in town. And Love Child played a WFMU benefit with Sonic Youth and Dim Stars, so I got to know them all that way. When they were doing the Sonic Death fanzine in the early ’90s they were doing something on Charlemagne Palestine, because Lee had done digital transfers for the first CD reissue of Charlemagne’s Four Manifestations of Six Elements album. I mentioned to Lee that I’d interviewed him, and that’s how it got printed in their fanzine. And actually around then I went to see Lee play with William Hooker, at the Knitting Factory, and when I was saying hi afterwards he said, “Hey, that guy Jim O’Rourke is here, do you want to meet him?” That was how I met Jim, backstage at that gig.

The Sonic Youth folks would do one-off shows at the Cooler. I was on one improv gig with Lee, William Hooker, and DJ Spooky. I think that was the first show Lee and I played together. This is also funny, because last night [at Wonders of Nature] the turntablist Maria Chavez asked me about doing a performance series where she plays with people, but she has to only play records by the person. I said, that only happened to me one time, because DJ Spooky had played my first solo guitar record, Sink the Aging Process, at that show. There was another show where Lee was reading poetry and people were doing round-robin improv behind it, sort of musical chairs. So I’d done a couple things like that with him.

Text of Light happened because William Hooker sent me an email asking to play Tonic with me and Lee, and on the same day Ulrich Krieger also sent an email asking the same thing. I was like, alright, let’s all play together. Lee agreed, asked Christian Marclay to join in, and also had the idea of playing in front of a Stan Brakhage film. I’d seen a few Brakhage films and suggested Text of Light, which I’d seen in college. It’s all reflections of light off an ashtray, which I related to overtones, that sort of thing. Tonic still had a 16mm film projector and I’d already done a film series there with Will Oldham. We tried to stress that we weren’t making a “soundtrack,” that it was a mixed media project. It was neat how it would sometimes link up arbitrarily with the film. Some people told us that it was a great kind of alternative experience to just watching the film silently, and that if you were going to put some music together with it then this was the way to go. And some people thought it was sacrilege, and didn’t like it, but that’s the way it goes.

Christian Marclay was part of Text of Light. Were you aware of his art before working together?

I was very aware of it, and had been for quite a while. I bought Record Without a Cover when I was a teenager, in 1985 or something like that, and saw one of his exhibitions at Paula Cooper Gallery a couple of years later, I was a big fan. Actually, one time I played that record when I had a radio show at Vassar. I took just the first three or four minutes of it, a recording of pops and clicks from vinyl which you might hear at the beginning of a record. And I kept playing it for about fifteen minutes, just moving the needle back to the beginning after a couple of minutes, so it was continuous pops and clicks. I guess the music director of the station was driving back to campus, thought it was dead air, and freaked out. Finally, I came on and announced that it was Christian Marclay. She was relieved. I thought it was funny back then, but it probably wasn’t all that funny. I got to know Christian when I started working at Tonic. He curated a series at Tonic of Swiss improvisers, and Lee and I did a trio with Stephan Wittwer, who I’d seen live previously and was totally amazing. He did some great albums on FMP with Radu Malfatti.

There was a festival you played in Ystad, Sweden in 2002 that sounded really interesting, with Marclay, Peter Brötzmann, Kevin Drumm...

AL: I played with Brötzmann and Mats Gustafsson as a trio. Brötzmann had brought a huge contrabass saxophone. Usually it would be too heavy to take on tour but I think he drove it to Ystad for the festival. I did a short solo with the guitar cable buzz, like the Calvin Johnson 7-inch, and Brötzmann liked that—“That was a good guitar solo.” When I played with him and Mats I thought I would take it easy on the volume since they were playing unamplified, but once they started I had to run back to the amp and turn up since they were so loud, I couldn’t hear myself. Christian was at that festival too. I played what later became YMCA at this other venue a little outside of town. It was a fun week. Yoshimi was there and had a group improvisation worked out that I participated in, kind of a precursor to 77 Boa Drum, in hindsight.

I know you booked a film series at Tonic. Did you also book shows?

Yeah, I booked shows there regularly, from 2000 until it closed in 2007. I took over for Chris Corsano. Melissa, one of the owners, was doing the majority of it at first, then Chris did it 50/50 with her, and that’s what I did, though maybe it ended up with me doing 70/30.

Were there any shows you booked for Tonic that were out of the ordinary?

One show with Corsano stands out. It was Chris solo and Sean Meehan solo. Chris’s set was great, and then Sean had a drum set on stage and was putting masking tape on the drum heads and the hardware, writing something on it, and then walked offstage and out of the club entirely. People walked onstage and had a look at what he had done. He turned up ten or fifteen minutes later. It was this very high concept set. Chris is an incredible drummer, especially solo, as is Sean, but it was sort of perfect that Sean didn’t even try to do solo percussion, just this conceptual performance, that was genius, really.

Finally, I wanted to know how you got involved with the HBO series Vinyl.

That was through Lee. He and Don Fleming got this gig doing some musical direction for the show. Randall Poster was the music supervisor. They weren’t just licensing music, they also wanted to make new recordings for the on-screen actors to be miming to. It started off being some recordings for what were supposed to be the demos that the fictional band in Vinyl, the Nasty Bits, were going to be making. They used these songs by Jack Ruby, kind of a proto-No Wave band that didn’t put out records, but someone uncovered the tapes and released them on a couple of labels a few years ago. I had always heard about Jack Ruby from Rudolph Grey, he said they were incredible, one of the best bands from then that nobody ever heard. They put together a band to play these Jack Ruby songs which was me, Lee, Don, Steve Shelley on drums, and James McNew on bass. They also needed us to re-record this other song by James Jagger’s real-life band. That made up the initial session at the Sonic Youth studio in Hoboken for the pilot. About a year later, they found out the pilot had been picked up and were going to start filming the rest of the series, so we were in to keep making these recordings that were meant to be a fictional band playing.

There was another session which was supposed to be for a scene where the Velvet Underground was playing, part of a flashback where the main character, played by Bobby Canavale, is going to see the Velvet Underground in 1966. For that session it was me, Don and Lee, Tony Shanahan, who plays with Patti Smith, on bass, Sim Cain playing drums, and Julian Casablancas was the vocalist. We were doing “Venus in Furs” and “Run Run Run.” This was at Electric Ladyland studio. I did the solos in “Run Run Run,” and when you see the actual show, the Bobby Canavale character is having sex with a woman in the bathroom during my guitar solo. When I saw that, I thought, this is what I was put on earth to do (laughter).

The rest of it was doing different songs that Jimmy Jagger’s band in the show were supposed to be playing. “All Day and All of the Night,” covers like that. Another was a really obscure song by the Punks, some early ’70s band out of Michigan I’d never heard of before. They also had us come on set as consultants a couple times. I coached one actor miming a guitar solo that Matt Sweeney had played on another song for the show. Matt and I are homies—I didn’t know him in high school but the bass player in my band also played bass in a band with guys from his high school, and I would hear about Matt and other guys playing in different bands in that school. I’m sure Matt and I were both at some of the same local Jersey gigs back then, Anyway, it was fun to be a part of all of that. I’m even in one scene in the show, I’m an extra at a party in Alice Cooper’s hotel room.

Sal Maida was playing bass for some of the Vinyl sessions. He had played in the band Milk ‘n’ Cookies in the original CBGB era, but he was also in Roxy Music and Sparks at one point, because he lived in England in the early seventies. I remembered his name because I thought there was some connection to Rudolph Grey and after some checking I realized it was because Sal had played in Von LMO’s first band, Funeral of Art, which Rudolph did lyrics for. When we were first in the studio together, I think Don brought up the Von LMO connection, and I said, “Yeah, Funeral of Art,” and Sal did like a triple-take and said, “Oh my god, how did you know the name of that band?” Again, another weird connection to something I’d done twenty years beforehand.

Alan Licht’s music can be heard at Bandcamp. Licht’s new book, Common Tones: Selected Interviews with Artists and Musicians 1995–2020, can be purchased at Blank Forms.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Black Midi - Cavalcade (Routh Trade, 2021)

Press Release info: No second album syndrome and no sophomore slump for Britain’s most exciting and challenging young rock band. Black Midi’s follow up to Schlagenheim is a dynamic, hellacious, inventive success. Cavalcade, their second studio album for Rough Trade, scales beautiful new heights, reaching ever upwards from an already lofty base of early achievements.

Geordie Greep, the band’s mercurial guitarist and primary singer explains the fundamentals of Cavalcade: “A big thing on this album is the emphasis on third person stories, and theatrical ones at that.” Cameron Picton, the inventive bassist and occasional singer agrees: “When you’re listening to the album you can almost imagine all the characters form a sort of cavalcade. Each tells their story one by one and as each track ends they overtake you, replaced by the next in line.” Morgan Simpson, the powerhouse drummer advises: “Enjoy it, live with it, spend some time living in it.” When pressed to choose one word to describe the album, Geordie elects for “drama” adding: “The emphasis when we were making and sequencing Cavalcade was to make music that was as dramatic and as exciting as possible. The flow has the feel of a story, which is rewarding to listen to.”

Purchase Cavalcade at Bandcamp and the Rough Trade website.

Nick Zanca: From the first, Black Midi has burst at the seams with youthful art-student ambition, fueled by a fiery eagerness to impress. Their collective chops cannot be denied—many arrangements here evoke Rock-in-Opposition antics at their most rambunctious, and this record is a showpiece for drummer Morgan Simpson in particular, a star performer of athletic stamina who easily could have cut his teeth with electric Miles in another life. But what this music ultimately suffers from is a noticeable lack of organization and a short attention span. Like a gen-Z Mars Volta, all elements emerge at once from the first five seconds of opening cut “John L”, guns blazing—the moment a listener is permitted to dissect the details of its hyperactive, Hieronymus Bosch-like maximalism, the ecosystem shifts gears into new and frustratingly extrinsic ground (a seasoned producer’s nightmare, to be sure).

For followers of their flighty footsteps, I imagine Cavalcade’s sound will probably appear as a maturation, an attempt to move past the relentless repetition of their earlier work. Efforts to shake off old gimmicks and expand horizons are nakedly apparent—I hear Geordie Greep trying to evade his signature sprechgesang brogue in favor of unsubtle smoky balladry. With that transvaluation comes a harmonic upgrade prone to the occasional deeply-pleasing chord change; I just wish these moments of fleeting beauty shown through songcraft weren’t squandered by the smugness of certain curatorial choices (any ode to a silent film star will elicit eyerolls from me—unless, of course, you happen to be Paddy McAloon). Had I heard this record as a teenager, it would have rewired my brain; its strain of shock and awe would have been subject to endless headphone monomania. Perhaps my decelerated present pace of listening is to blame, but these days I am far less impressed by this realm of grandiosity. Be that as it may, I have no doubt that the desired “wow” factor could quickly manifest itself to mastery if only they cast the impulse to world-build aside, and instead approached their palette with more patience, one note at a time.

[4]

Gil Sansón: Black Midi’s debut album was a snapshot of a band that had just discovered their power, relying heavily on improvisation and instant communication between musicians. What happened in the meantime is that they became famous, went on tour, and grew tired of the approach that initially put them in the spotlight. Their sophomore album Cavalcade finds them getting deeper into the genre references they’ve explored before—noise rock and math rock in particular—but in a more deliberate, composed way. Opener “John L,” for example, sounds more like the King Crimson of Lizard than the typical Amphetamine Reptile noise-rock act. Right after, we’re thrown into the Scott 4 universe with “Marlene Dietrich,” a not-so-subtle hint that the band is aiming for songwriting as opposed to their previous impromptu jams. The jagged edges for which the band is known reappear on “Chondromalacia Patella,” this time in arrangements that head into straight-up prog-rock territories. And elsewhere, they sound like they’re trying to be Faith No More in their aim to push weirdness into the mainstream; they make sure the prickly and soft bits are in perfect proportion.

There’s a certain skepticism that arises: on one hand, I’m impressed by the vitality of the sound, but on the other I’m underwhelmed by their approach, which feels far too studied. At times, it feels like they’re bravely exploring new areas, but on a track like “Dethroned,” the Scott Walker vocal stylings, convoluted beats, and jangling guitars sound less convincing in combination. Maybe my main complaint is that I can hear them trying when rock should sound like the most natural thing in the world, but it’s hard to complain when you see a band that’s been hyped to ridiculous heights trying so hard not to suck. People will hear this album and play a game of “spot the influences,” but I think the real pleasure here is in witnessing a band with real potential grow in the public’s eye. So let Black Midi have their saxophones and acoustic guitars next to their sonic explosions, and let’s do what people used to do with a band this massive: assume good faith from those involved and let them take you on a journey.

[7]

Sunik Kim: I don’t think I’ve ever heard such a swaggery, bombastic album that feels so utterly humorless and devoid of life. The music feels like a multilayered, painfully self-aware parody whose sole purpose is to haphazardly trigger rockist pleasure-synapses (“they’re doing King Crimson… now they’re doing Beefheart… now they’re doing Zappa…”), a piling-up of infinite chains of references with no distinguishable core, substance or purpose. Every musical tic and quirk at play here only makes this lack of identity more excruciatingly clear: the surrealistic, nonsensical lyrics—and their forced, opera-gone-horribly-wrong delivery—are a bottom-shelf iteration of an approach already decades out of date, while the jerky, stop-start prog-rhythms actually gave me second-hand embarrassment via how hard they tried and how flat they fell.

The sound here also occupies a colorless middle ground between “fully-produced” and “off-the-cuff”—the drums and guitars are thin and tinny, like a quickly-mic’d live session, but there is also a relentless torrent of whizzing studio trickery that rears its flashy head in the forced, predictable “climaxes” that cap off several of these tracks. As a result, the gimmicky shield that “they’re a live band” is no longer able to paper over their fundamental compositional weaknesses; Black Midi are pulling out all the stops here, and the result is worse than I ever could have imagined.

A brief examination of the album artwork might be illuminating here. On first glance, it seems dazzling, chaotic, singular and full of life; but on a closer, lengthier look, the image starts to lose its luster, the different colors melt together—when you mix red, yellow and blue, you get brown—and the whole thing starts to feel so perfectly manicured and calculated that it barely even elicits any reaction at all. The music itself follows the exact same trajectory: it desperately hopes to hide its fatal flaws behind a ragged parade of novelties and curios, but none are able to prevent the inevitable conclusion—that this is soulless, cynical music.

[0]

Mark Cutler: Basically, Cavalcade sounds like if Fiery Furnaces were good. Whereas Schlagenheim’s abrupt tempo and style changes were presented as interesting in themselves, here they serve only as pivot points to cram in more references, more influences, more instruments. There is pummeling math rock, fuzzboxed post-punk and proggy noodling, yes, but also campy balladry, ’80s buttrock riffs, orchestral breakdowns, blues crooning, smooth jazz licks, and probably a glockenspiel somewhere in the middle. It’s rarely unpleasant listening—with the exception of “Diamond Stuff,” which plinks along for the better part of four minutes before giving way to the kind of major key orchestral swells that people lazily describe as “cosmic.” However, it doesn’t feel particularly new or memorable either. All these virtuoso turns, yes—but why? If we’re at the point where even this kind of history-spanning reference-rock has become a genre unto itself, then Cavalcade is one of the stronger entries in that genre. However, it feels a bit too studied to really compel.

[6]

Zhenzhen Yu: Even beyond the trendy Slint influences, a mysterious KEXP session, and extremely quotable lines about moving with purpose, there’s a crystal clear quality still present from the very first few minutes of Cavalcade: Black Midi do not ever play as if someone is watching them. When Greep talks and sings and raves, I believe him. While talk-singing is an integral part of dry, artsy post-punk, its core function hinges on the awareness of an audience; your own passive participation is an expected instrument in the song. “Mother is juicing watermelons on the breakfast stand,” Black Country New Road’s Isaac Wood proclaims, provocative, a theatrical tremble in his voice; “It’ll be okay,” Dry Cleaning’s Florence Shaw assures like a friend, clearly and coolly, “I just need to be weird and hide for a bit.” Even Mark E. Smith once watched, carefully, out of the corner of his eye. But when Geordie Greep sings, it’s as if has his eyes screwed shut: there is a conviction in his voice that is natural and uneasily visceral, exacerbating an already frenziedly Biblical cadence to his words, the invocations of “torn robes” and “bloody glory” and an inescapable “infernal din.”

The same goes for the rest of the band, like on the larger “John L,” “Hogwash and Balderdash,” or “Chondromalacia Patella,” with strings that snap like shrikes and drums that fire off like machine guns. Black Midi moves explicitly parallel to an audience, instead producing something foaming, alien, a thing which displaces self-awareness and leaves behind only the laser-sharp focus of the harshly calculated music itself. And while I was initially put off by the more static nature of a tracklist recorded without total improvisation, a loss of acerbity isn’t necessarily a step back, either. The ten-minute final track, “Ascending Forth”, looks as if it’ll be a “Ducter”-like moment of sprawling prog, but instead sharply veers into a far gentler— but just as complex— train of ballad-like vocals and deliberate jazzy backing. “A receding hum, akin to pink noise / Escapes his cerebral hand that toys,” Greep narrates as the song rises, his own voice ascending passionately, finally infused with that unfamiliar air of theatre—and even now, he still looks away from your gaze.

[7]

Eli Schoop: Last time I reviewed Black Midi, it was for Tiny Mix Tapes, where I compared them to 20 bands simultaneously. It’s one of the tenets of music criticism, X band sounds like Y, giving you context for what the music sounds like. In this sense, Black Midi could be construed as entirely referential, a product of looking backwards rather than forward. On Schlagenheim, this could’ve been leveled at them. Cavalcade, however, shows them making the record only they could make. It brings to mind something I would dream up in my head as a kid—every nook and cranny saturated with riffs, unbuoyed by petty things like structure or cohesion.

One of the coolest things about Cavalcade is its implied camaraderie. The songwriting here comes across as fully democratic, every member getting their shine but never in a selfish way, because it always benefits the song. Consider “Slow”: a twisted showtune thrusting Mahavishnu Orchestra-esque grooves straight at you. It sounds cheeky, but everything’s played serious, and by immensely talented musicians who are ready to showcase how they can contort their instruments into fully-formed medleys.

For the more skeptical listeners, Cavalcade may be more your taste; Geordie Greep simmers down the nasally monotone he’s known for. Nevertheless, Black Midi have out-Black Midi’d themselves. Sticking to any sort of predictable formula was never in the cards, and on Cavalcade, they’ve doubled down on stylistic whiplash, a feverish willingness to commit to ideas, and prog instrumentation that would make Robert Fripp and Bill Bruford blush. The standard of the new wave of English avant-rock has been set.

[8]

Average: [5.33]

Erika de Casier - Sensational (4AD, 2021)

Press Release info: Sensational expands the universe of de Casier’s 2019 self-released debut album Essentials. Where Essentials dealt more with the infatuation stages of love, Sensational has more of an attitude, aiming to dismantle the stereotype of single women looking for love, tackling relationship dramas and the toxicity of dating. It was a chance to rewrite scenarios in ways that empowered her, fantasising about what could’ve been. Sensational was co-produced by de Casier and is a breath of fresh air to anyone with a passion for music in all its genres, as much influenced by Aaliyah and Janet Jackson as house, garage and techno. With hushed, pillow-soft vocals and production that references turn-of-the-millenium sounds, de Casier’s sound surveys the past while looking to the future.

Purchase Sensational at Bandcamp and the 4AD website.

Nick Zanca: In an interview with Ebony Magazine reflecting on the production of Love Deluxe twenty years after its release, Stuart Matthewman credited the shape of Sade’s sound solely to interplay. “We don’t have any rules,” he admitted, “we have a sound that only the four of us make. Part of the sound is not overplaying; it’s sort of minimalistic. There aren’t a bunch of big fancy solos … we like to keep things simple so it resonates.” This attitude is plenty proof that the band’s streamlined sophistication was always a question of chemistry, and that however understated and unchanged from past releases, the impact of the 1992 record’s sound cannot be denied—a similar feng shui of elevated “easy listening” has revealed its smooth interior on several records to follow before we finally ended up here nearly thirty years later.

Sensational—an apt title—seems to sustain the sparse, everything-in-its-right-place ethos of its quiet-storm forebears at the turn of the millennium rather than opting for a total derivative. Wary as one might be of emulation, the lush nuance of Natal Zaks’s studied productions aren’t lost—this nostalgia is still new enough that any spitting-image resemblance to rompler-ready R&B and UKG has been embellished and kept alive rather than resuscitated (let’s get real, it never died); it provides the listener with the inverse effect of, say, a stylist like Kevin Parker’s insistence on a worn-out decades-old psych-production circus act. As a vocalist, de Casier’s downplayed delivery stays true to patient predecessors like Aaliyah and Janet, sinking into the digital bubble-bath rather than making a melismatic splash and outstaying her welcome. Though the palette at play is nothing new, it’s approached with a newfound, four-dimensional tactility that did not exist before under Darkchild’s discretion; what emerges upon boosting the bass can only be described as a pleasure principle most potent.

[7]

Sunik Kim: This is a serious cut above the average golden-age R&B revival project—what really distinguishes de Casier’s music is, unexpectedly, its sense of humor. The tension between her ice-cold delivery and some of her most cutting lines—the run that begins with “Versace this, Versace that” on “All You Talk About” is brilliant—does push this well-worn source material into genuinely new and engaging territory. The key is that the production is almost as funny as de Casier: though it’s clearly a contemporary iteration of the classic R&B beat, its absolute, unwaveringly pillowy limpness deftly straddles the line between slapstick and effortless beauty—the former most evident and hilarious in its shy, hesitant takes on classic FX (bicycle bells, squiggles and bleeps, windchimes, maybe even a siren), the latter in its somber, wandering harp lines, plucked jungle-cello hits and ghostly Jazz Org basslines. The album’s main flaw is bloat—there are a handful of filler tracks, and the interludes only frustrate an otherwise smooth listening experience. But the highs are high, and hooks abound left and right—highlight “Call Me Anytime” is a quiet barnstormer, a simultaneously subdued and hyperspeed pop track that captures that odd mixture of melancholy and euphoria released by the greatest club anthems. De Casier is onto something really compelling here—against all odds, I’m not sure there is any music out there that sounds quite like this.

[7]

Vanessa Ague: On Sensational, Danish singer-songwriter Erika de Casier traces the contours of the tumultuous phases of love in powerful murmurs. She isn’t taking on new topics—unrequited love, mismatched dates, and desire are universal life experiences—but her elastic, shimmering voice proves wholly enveloping. Her vocals remain soft throughout the album, but they’re never subdued: the subtle changes in her vocal delivery, from whispered spoken words to wistful hisses to breathy hums articulate her rapidly shifting emotions. Her glistening breaths lay in a bed of ’90s and ’00s influenced accompaniment, creating a gauzy atmosphere driven by glimmering harps and laid back beats. De Casier’s music on Sensational is a reminder that delicateness isn’t equivalent to powerlessness. Rather, in her understated pulse, she finds an unending strength.

[7]

Maxie Younger: Evening: white plains of sand, white foam of the waves. Salt-spray breezes rustle my hair. The warp and weft of bedroom curtains that dance in the wind: stars framed with billowing gauze, blotted by pale shreds of sunset. Sensational is the call from across the gulf, led by Erika de Casier’s ethereal voice; songs dance on air, shimmering at the horizon, held together through breathy invocation. Opener “Drama” is the clear highlight, but not for lack of trying on the rest of the album’s part: the song is just that good—a creamy confection of tightly wound guitar, thick percussion, and angelic Casio-cheese synthetic strings. Indeed, de Casier runs into a bit of a wall with her aesthetic as the album drags (and drags) on; there are only so many times she can cast the same spell before the magic wears thin. Her signature feathery delivery and narrow vocal range tend to limit her emotional breadth in much the same way as they did on her last album, Essentials. Sensational’s mood stays locked at breezy and contemplative for its whole running time, only finding dimensionality from de Casier’s deep, meticulously curated pool of references: trancey rave-synth stabs on “Someone to Chill With,” quick detours into two-step garage drum patterns on “Busy.” These sweet, subtle touches aren’t quite enough to stop the tracks on the back half from blending together (I tend to lose the plot around “No Butterflies, No Nothing”), but it’s refreshing to hear an artist apply their knowledge so deftly and with such restraint. No, Sensational isn’t quite up to the challenge laid out by its title; but, it’s an enjoyable ride, one on which I’m never wanting for beauty and impeccably crafted atmosphere.

[6]

Adesh Thapliyal: Like Kelela, Erika de Casier comes to alt-R&B from the underground dance world. While the former emerged out of the futuristic Fade to Mind crew, de Casier got her start as part of the Danish retro house collective Regelbau. Given her crate-digging associates, it comes as no surprise that Sensational is full of nostalgia for everything ’90s: post-Sade quiet storm, hip-hop soul, deep house. Also not surprising: intricate production that breathes new life into dated pop motifs, from hushed clave taps (“Polite”) to “No Scrubs” harpsichord riffs (“Busy”) to shimmering chime glissandos (“Secretly”), as that is basically Regelbau’s mission statement.

No matter how sophisticated the production, though, this kind of R&B lives or dies on the drama of its lyrics, and this is where Sensational comes up short. de Casier has penned lines of cryptic beauty in the past (“Part of you’s like Sunday on the highway”), but here opts for a more plainspoken style; the result is melodies that meander and lyrics that remind you of other, better songs (“Drama” [1], “All You Talk About” [2], “Friendly” [3]). Compared to the tight songwriting of her aptly-titled debut album Essentials, Sensational is a step backwards.

[5]

Vincent Jenewein: Sensational is musical fabric softener. I can’t find anything that’s unpleasant about it, but the album’s thirteen tracks pass through the ear so smoothly and effortlessly that it doesn’t really feel like you’ve listened to them after they've played. It’s not that de Casier and her producer-collaborator DJ Central from the Danish Regelbau crew—who have put out some of the best purist house of the past five years—wouldn’t have the chops to produce something more memorable, it’s just that accurately aping toothless ’90s chill-out R&B and 2000s poppy 2-step and then making it even more chill and tidy is a recipe for gratuitous velvetiness.

The warm lo-fi grit and particular vintage Detroit touch that have spiced up most of DJ Central’s solo productions are almost entirely missing in favor of polite, ineffectual ’90s R&B drums, classy and organic guitar licks, and balmy Rhodes chords straight out of a generic lounge playlist. Throughout the record, de Casier’s vocals are delivered in a whispery style that lose their energy, attitude, and capacity for hooks by overvaluing the virtues of closeness and intimacy. To me, the entire record feels like a step back compared to the playful energy and more characterful production of de Casier's Essentials and especially her first single “Drive.” Whereas those projects pointed towards a subtle evolution of their influences, Sensational has only its timely millennial and Gen Z update on R&B lyrics to save it from being a sapless epigone.

[3]

Samuel McLemore: I’m not quite sure what the theorists say, but I pretty firmly believe the core of what makes pop music “pop” is the kind of emotional connection and identification the audience gets to share with the singer. Other than that one qualifier (which is arguably just as much an extramusical factor than one intrinsically musical) there’s no rules: the artist can fill in the blanks as they so choose. Conceptually, at least, Erika de Casier has taken the route of making her pop album a referential game of late-90s R&B aesthetics as much as it is anything else. As a wannabe music historian myself this attitude is straight catnip for me: you can practically peer through the backing tracks here and see the lineage burned into them. Unfortunately the basic “pop” part of the album—the part where the melodies and the production tricks meld with the singer and the lyrics to somehow, mysteriously, enhance the emotional resonance of the songs—is deeply lacking. The hushed mood so clearly cultivated in de Casier’s breathy vocals and Natal Zaks’s production combines with a serious lack of hooks to suck the life out of every song, and eventually the dedication to an older aesthetic styles just comes across like an attempt to cash-in on something that was already proven to be popular decades ago.

[3]

Gil Sansón: I’m old enough to remember when the 4AD label had a distinctive sound made by white artists based in the UK, making music that was deliberately removed from R&B. Much water under the bridge since, but this record, despite being very much in the R&B vein of, say, Aaliyah, still retains the careful and exquisite production style of the label’s classic albums: de Casier’s music is sensual and elegant, showing both vulnerability and strength. It’s a good idea to start the album with “Drama” since its guitar sounds like one you’d expect from a 4AD release—she’s a good fit, and takes them to new ground in an effortless manner. The lyrics refer to the most boring, frustrating, and unpleasant aspects of dating. On “All You Talk About,” she deals with the insecurities of men without rubbing their faces in the mess. Granted, a lot of people like their R&B in their face, but this is a classy product whose understatement works like a charm.

Even when Sensational sounds a bit precious, the down-to-earth lyrics ground the music in reality. “I’m stronger than I look,” she utters in “Insult Me”; the music could say the same. Stylistically speaking, there’s this basic template of modern R&B that’s then updated with subtle outside influences: “Someone to Chill With,” which states this most reasonable of wishes and which so many men have a problem dealing with, has a really sweet Morricone-like intro that ensures the win from the start. The short intermezzo that segues into “Better Than That” (the moment of the album that sounds the most like mainstream R&B) provides warm acknowledgement, the kind you can get from strings in the classical tradition. And the sample from Recuerdos de la Alhambra on “Friendly” is another fine example of showing your cards from the start. In her unassuming lyrics she makes sure not to sell herself short or to compromise, and the music sells it. It’s all done without boasting, but exudes confidence nonetheless. She makes it sound easy, but we know how difficult that is.

[8]

Average: [5.75]

Press Release info: Loraine James comes with her second album for Hyperdub, made in the summer of 2020. Reflection is a turbulent expression of inner-space, laid out in unflinching honesty, that offers gentle empathy and bitter-sweet hope.

2020 was tough for Loraine; unable to tour and build on the success of For You and I, Loraine was prolific in the studio, self releasing, plus releasing the well received stepping-stone Nothing EP, which realised a unique pop sensibility she develops more here. Her 2020 listening habits - Drill and R&B seep through into Reflection too. In contrast to the brash splashes of For You and I and the grimey anger of Nothing, Reflection is pared down and confident, taking the listener through how the year felt as a young Black queer woman and her acolytes in a world that has suddenly stopped moving.

Purchase Reflection at Bandcamp.

Maxie Younger: It’s established early on: “I like the simple stuff, I like the simple things,” Loraine James whisper-croons over blown-out 808s and snares soaked in crisp, astringent reverb. Reflection goes full Hyperdub, pivoting from the anxious IDM glitch-fuzz of For You and I to a simpler, more digestible package (for better or worse) that leans heavily into the aesthetics of drill and weightless grime; gone are the frenetic breaks of “So Scared,” the shrieking grindcore hiss of “London Ting.” The collaboration with Baths, “On the Lake Outside,” feels most emblematic of the change, a bassy, ambient alt-pop jam that soars through its quick falsetto verses and swells of frosty atmospherics like it’s got somewhere to be. Most of Reflection’s songs are content to exist in this manner, establishing floaty, minimalist moods at their onset that persist without evolution. The album’s title track holds the only real compositional surprise, as James’s quiet monologue on the effects of the pandemic on her relationships is suddenly invaded by a pulsing, reedy trap beat that threatens to overwhelm her: “This is Loraine James’ reflection,” she states plainly. It’s a relatable headspace to those of us affected by the collective stressors of 2020—a world of cold silences, churning interludes: outbursts that fade to black, slow thoughts that swim through icy waters. Reflection is meditative, self-aware and self-conscious, bordering on the transcendental; it is as good a response to The Sad Year as anything else. I wonder how foreign it might all seem to us in the future.

[6]

Sunik Kim: James’s music is astonishingly crisp and direct, driven by the straightforward, no-nonsense tension between a hefty, rigid beat pattern and one other musical element of choice: a warped, melting chord sequence, or a pitched-and-chipmunked vocal sample. The sparseness of her sound initially gives it a raw, straight-from-harddrive quality, but her laser-focused ear for sound design adds a distinctly contemporary, ear-tickling element that renders her music singular and recognizable even in its clear indebtedness to familiar club and beat traditions. The first three tracks feel like a perfectly-executed boxing combination, each one dutifully bringing the goods: the screwed vocals in “Built to Last” disarm in their wavering atonality, riding James’s nimble clatter of snares and snaps; “Simple Stuff” cobbles an addictive hook out of the most unassuming spoken material; and highlight “Let’s Go” hammers away under an incandescent cloud of swooping, slurring synth tones. The rest of the album makes for a solid listen, but few tracks reach the heights of that opening run—the remaining tracks are less sure of themselves, meandering and circling, making a journey inward rather than hurtling forward.

[6]

Adesh Thapliyal: James’s debut album, For You and I, announced the arrival of a major new voice in electronic listening music. Its only flaw was how much its voice was indebted to and derivative of ’90s Autechre-core. Her second album, Reflection, finds her exploring deconstructed club, trap, and alt-R&B in search of a voice of her own. Most tracks here feature vocalists, and to accommodate them, James’s sound palette is less extreme than in her debut, and her virtuosic percussion programming toned down to pop-friendly grooves. The romantic, Boards of Canada vibe her first album had has also dissipated, replaced with a steelier, colder sound; in For You and I, the percussion worked with the melody to create a sensuous whole, in Reflection, they bicker and interrupt each other. In this way, Reflection is a transitional record, a WIP grounds for experimentation towards a new sound that doesn’t quite make it. The best here, like “Self Doubt” and “Running Like That,” is just interesting, unique enough to perk your ears, but, ultimately, not scaling the aesthetic highs of something off her debut like “Vowel // Consonant.” Reflections is a cocoon; maybe in James’s next record we’ll see it hatch.

[6]

Mark Cutler: Sonically, nothing here feels super fresh. A lot of the production, down to the skittering synth lines and manipulated, multitracked vocals, calls to mind Xen-era Arca and the glut of melty, hookless “dance” music that came in her wake. This is probably why—with the obvious exception of Baths, who has yet to put his name to a single sufferable track—the tracks with guest vocals tend to work best. James’s style is most interesting when she tries to bend it into a drill or grime instrumental for someone to rap over. By contrast, the instrumental-heavy tracks tend to fall flat. On the extremely-seven-minute “Change,” James spends most of the runtime draping percussive bangs and squeaks around a single, repeating chord which, I’m not kidding, really might be sampled from &&&&&. Perhaps it’s supposed to be a joke that a song called “Change” mostly doesn’t, but it kills whatever momentum James had built up to that point. James is clearly a good producer, and I hope she continues to collaborate with a wide array of vocalists in a wide variety of styles, but Reflection flounders a little too often across its forty-six minute runtime to be a solid start-to-finish listen.

[5]

[8]

Marshall Gu: After falling in love with Burial and then DJ Rashad’s Double Cup, I dutifully went through Hyperdub’s roster to look for anything with the same emotional resonance to fill the void of Burial not doing much of note after Rival Dealer and DJ Rashad’s unfortunate death in 2014. Long story short, I found plenty of good beats but very little that gripped me the way those two artists did. No one else made the atmospheric beats that Burial was interested in, and 15 years after Untrue, I’ve still not heard anything quite like it. And as for DJ Rashad, Double Cup is the rare footwork album that plays like a genuine collection of actual songs.

So when I say that Loraine James’s For You and I was the best album I heard from Hyperdub in years, I mean it. For You And I was two things, both bold. First, it was a collection of love letters to different strands of electronic music: UK bass and grime and glitch and deconstructed club and IDM and footwork and the gamut of genres only seemed limited to the number of songs on the album. But what impressed me more was that it all reflected James’s personal experience as a Black, queer woman. Here she was, this “Dark as Fuck” “Glitch Bitch” who made “Sensual” music “For You and I.” I could not fall in love harder.

Reflection is a continuation of that; it even has a literal sequel to “London Ting // Dark as Fuck” in “Black Ting,” both featuring London rapper Le3 Black. “Insecure Behaviour and Fuckery” and “Self Doubt” both speak to James’s personal experiences with creator’s anxiety (“I know you might not like this one…,” she says on the latter), and when the repeated sample on “Self Doubt” goes “You are in a home / Leaving the club early,” it’s clear that the you in the sentence applies to both me, the listener, and her, the artist. Adding to this is the title track, a song that reflects on the past year and all of its new challenges: “Haven’t seen family or friends…” she quietly muses, the voice panning from channel to channel, pitch shifted around, like we’re offered a glimpse into her loneliness.