Film Show 21: ThousandSuns Cinema, Indigenous Edition (2023)

Reviews of 14 films from Media City Film Festival's 2023 edition of ThousandSuns Cinema, which focused on works by Indigenous filmmakers

Co-presented with COUSIN, a collective supporting Indigenous artists expanding the film medium, this year’s monumental ThousandSuns Cinema program shed light on Indigenous filmmakers. In a month with Sundance, Slamdance, IFFR, and more, the 60+ works shown in this Media City Film Festival online program were consistently, unassailably essential. Every work I saw, including those I had previously seen, felt vital in this context, depicting Indigenous film as rich, distinct, and boundless. I reviewed 14 highlights below. While these films were made available from January 9-30, they are still accessible from other sources and the relevant links are provided. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

My Name is Kahentiiosta (Alanis Obomsawin, 1995)

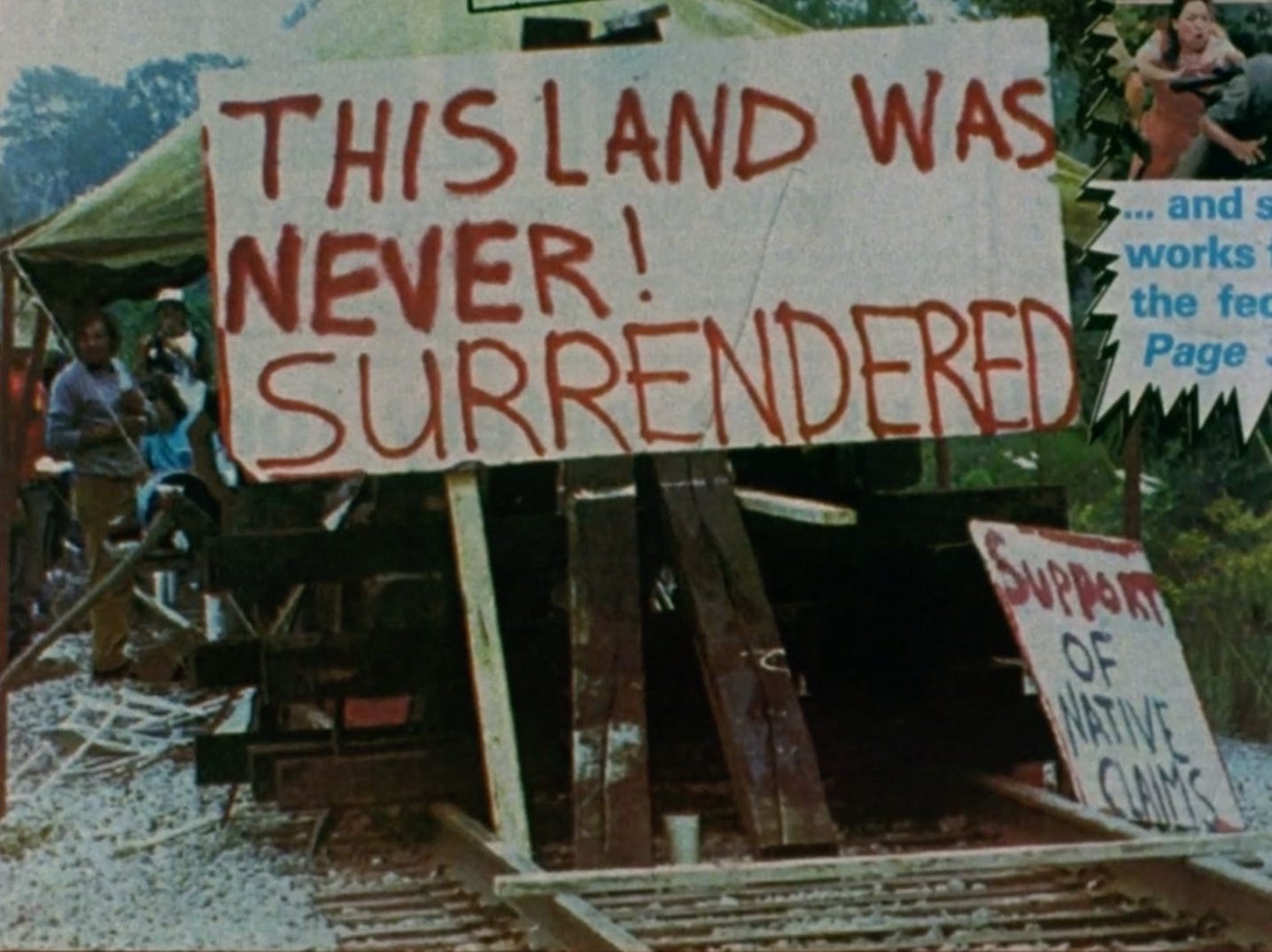

Alanis Obomsawin’s tremendous short film My Name is Kahentiiosta begins with the titular woman stating basic facts: “My name is Kahentiiosta. I was born in Kahnawake in my grandmother’s house. I was raised with five brothers and three sisters. I have two children.” This isn’t just a way to position this film as something inherently personal, which it is, but to make evident that what she and others fought for during the 1990 Kanesatake Resistance was the preservation of identity—for herself, for generations before, and for generations after. While covering the same event as the Abenaki director’s other landmark film, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, My Name is Kahentiiosta benefits greatly from zooming in on one specific woman. The result is a deeply emotive work that paints resistance as an inherently collective effort, both in the participation of specific actions and in the education of a people’s exploitation.

My Name is Kahentiiosta begins with historical context, sharing how the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1956 led to Mohawk families being forced to relocate, losing access to their natural waters in the process. Then there was the Canadian Pacific Railway, which changed the environment dramatically. You can read about their development online, and see how people describe them with such awe, with gratitude for how they helped make trade and transport more convenient. But at what cost? After it was ruled that the Pines would be destroyed to expand a golf course to 18 holes, those in the Mohawk Nation participated in a 78-day standoff. The photos and testimonies and footage that Obomsawin employ will leave anyone infuriated by the use of militarized power for such an exploitative act.

But despite all this, Kahentiiosta’s voice remains calm but firm. “We were all ready to die—we didn’t want to,” she explains. “Might as well go with the land, because it will never be the same.” There is a stark contrast between the Mohawk people and the military officers: the former group is constantly thinking about the future, while the latter is only acting in service of the short term. Indigenous rights are, as always, environmental rights. Kahentiiosta even explains why she brought her children: “I don’t want my children killed, but I want them to see the struggle we’re going through… if the younger ones see what happened, they’ll be stronger.” Amnesia and ignorance, this film suggests, keep one from being emboldened. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch My Name is Kahentiiosta at the NFB website. Find more information about Alanis Obomsawn at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

The Sun Quartet, Part 2: San Juan River (Colectivo Los Ingrávidos, 2017)

Colectivo Los Ingrávidos is a group of Mixtecos who strive to create political, avant-garde films that challenge conventional, mainstream norms. Personally, I’ve found a lot of their works to be a bit too abstract, thrusting images upon the viewer in a way that can be visually stimulating but little else. The Sun Quartet, Part 2: San Juan River is an important exception in their 300+ film oeuvre, documenting a protest in the aftermath of the Iguala mass kidnapping in 2014. The cries of the people take center stage, their emotions bolstered by the cacophonous superimpositions. When we see trees or flowers appear atop marching, their beauty feels like even nature is calling for justice to be served. When the crackling electroacoustic soundtrack accompanies the protesters who count to 43—the number of students who disappeared—it captures both the pain and urgency of the moment. It may not be the most thrilling work from Los Ingrávidos, but San Juan River is one where image and sound and intent clearly merge. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch The Sun Quartet, Part 2: San Juan River at Vimeo. Find more information about Colectivo Los Ingrávidos at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

From Sea to See (Eve-Lauryn Little Shell LaFountain, 2015)

There is a delightful home-movie shabbiness to Lauryn Little Shell LaFountain’s From Sea to See that highlights the bewildering reality of her everyday life. The Ojibwe filmmaker begins by sharing the history of Turtle Island—how tradition tells of people arriving from both the sky and water—as a way to juxtapose this origin story with its people’s subsequent colonization. That idea is more subtly telegraphed when images of a space shuttle (emblazoned with the American flag no less) are juxtaposed with traditional Ojibwe drum songs; with so much land colonized, these folks look to control terrains beyond our earthly home. And then as the camera regularly wobbles and shakes, even rotating upside down, there are cuts that create flashes of light—it feels like waking up and constantly fighting sleep, as if there’s no time to rest or fully appreciate what’s in front of you.

“We can not return to the water, we cannot return to the sky,” we hear. This is the current reality we must build on, and LaFountain acknowledges the difficulty in doing so: “The urge to document becomes stronger than the will to experience the moment… we feel the need to document our differences—our heritage, our lineage, the perspectives of our ancestors” Not only has settler colonialism done all it can to erase Indigenous past, it has made securing Indigenous future only possible through living in a removed and distant present. That this was shot on Ektachrome—a Kodak color reversal film that was discontinued in 2013—befits the seeming impossibility of documenting history, and the looming sense of expiration in one’s quest to do so. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch From See to Sea at Vimeo. Find more information about Eve-Lauryn Little Shell LaFountain at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

The Violence of a Civilization without Secrets (New Red Order, 2018)

The Violence of a Civilization without Secrets is the most compelling film from New Red Order, a “public secret society” that includes primary contributors Adam Khalil (Ojibwe), Zack Khalil (Ojibwe), and Jackson Polys (Tlingit). It begins with a story of Thomas Jefferson and how he became “America’s first archeologist” in 1784 when taking human remains from an American Indian burial ground. That fact is immediately connected to the history of museums and the donation of remains to their facilities—a lot of it is rooted in white supremacist ideologies regarding Indigenous inferiority. For any viewer who considers such thinking to be strictly in the past, the directors bring up a more recent case: the “Kennewick Man,” whose skeleton was found in 1996. His 9000-year-old body was thought by some to be of European ancestry, stoking ideas that white Europeans weren’t colonizers after all. The archival footage—news clips and a speech that receives applaud—is quietly horrifying.

New Red Order aren’t simply compiling old ephemera, though. Subtle but effective is the use of digital images overlaid with text. These passages provide information to guide our understanding of the event, but are also poignant in clarifying biases through an engagement of material through different senses. At one point, after hearing an Indigenous person share a story in court, we learn via text that oral histories were not considered legitimate evidence; presenting such information in a non-aural manner makes the point all the more cutting. One also considers the gross dichotomy here: a well-informed Indigenous person sharing information in a private setting, only to be ignored vs. the white folks communicating dumb racist ideas to the masses without reproach.

The film’s only contemporary footage involves people with slime-like masks entering a museum. At one point there’s a whisper: “A memory is not a container for information, but a perpetually emerging process.” There is a reminder in seeing these display cases with Indigenous history that our understanding and ideas of it are always growing. (That Eliane Radigue’s “Kyema” is the soundtrack for The Violence of a Civilization is also apt, as it deals with the “existential continuity of the being.”) As DNA testing in 2014 confirmed that the “Kennewick Man” was indeed not European, he was eventually reburied in 2017. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch The Violence of a Civilization without Secrets at Vimeo. Find more information about New Red Order at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Natsik Hunting (Mosha Michael, 1975)

Mosha Michael’s 1975 short film Natsik Hunting was the first Inuit-directed film produced by the National Film Board, and its seven minutes are a loving showcase of the traditional Inuit practice of seal hunting. Compared to Michael’s The Hunters (1977), Natsik Hunting stands out for eschewing narration, revealing how much is derived from this specific task through the power of its images. Anyone who reads about seal hunting can understand its importance to Inuit livelihood—they use as much of the animal as possible, be it for sustenance or clothing—but nothing quite cements that reality as seeing pools of glistening blood in glorious Super 8. It is profound to witness the team cut open the animal’s body to reveal all its viscera; in that moment, I was struck by their care and the significance of this act, and the literal life that this blood supports outside of its own body. It is a reminder of the interconnectedness of all life—a truth that most films with guts or slaughter or death never even approach.

The soundtrack, a folk song played on guitar by Etulu Etidloie, can feel jarring in its jaunty spirit, but that was something I had to question myself about—why do I want a film depicting a traditional practice to be devoid of such emotion? To only be a “pure” depiction? And how many “ethnographic films” have I seen that, in being directed by white people, are determined to be resolutely clinical in their documentation? As Natsik Hunting closes with a sunset, I remember that there is something missing in a lot of those other films: an overflowing joy that can accompany such everyday work. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch Natsik Hunting at the NFB website. Find more information about Mosha Michael at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Travelling (Anastasia Lapsui & Merkku Lehmuskallio, 2007)

Travelling is one of the major highlights in the entire ThousandSuns program, delivering a feature-length documentary that shows the life of the Nenets—and specifically, director Anastasia Lapsui’s tribe in the northern tundra of Siberia. It patiently follows them in beautiful 35mm footage as they engage in daily activities, be it taking care of toddlers, dancing, or chopping wood. But instead of this being a simple documentation of a people and their practices, we are told traditional stories from Lapsui, her songs and prose guiding an understanding of what’s happening while instilling poeticism into every action. There are few moments when images are painted atop the black-and-white footage, displaying an element of their beliefs that cannot be captured on film. That’s especially meaningful during the film’s final stretch, when we watch burial rites take place, and painted stars cover the entire screen. “To the one who travelled away, the Dipper stars shine on the end of the coffin, pointing the way to the netherworld to beyond the seven layers of permafrost,” we learn. Travelling is thus an encapsulation of the Nenets’ understanding of the entire human lifespan, and the music’s patient and varied instrumentation (bells, field recordings, traditional vocalizing, and more) enhance every shot with a patient, thoughtful grace. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Find more information about Anastasia Lapsui & Merkku Lehmuskallio at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

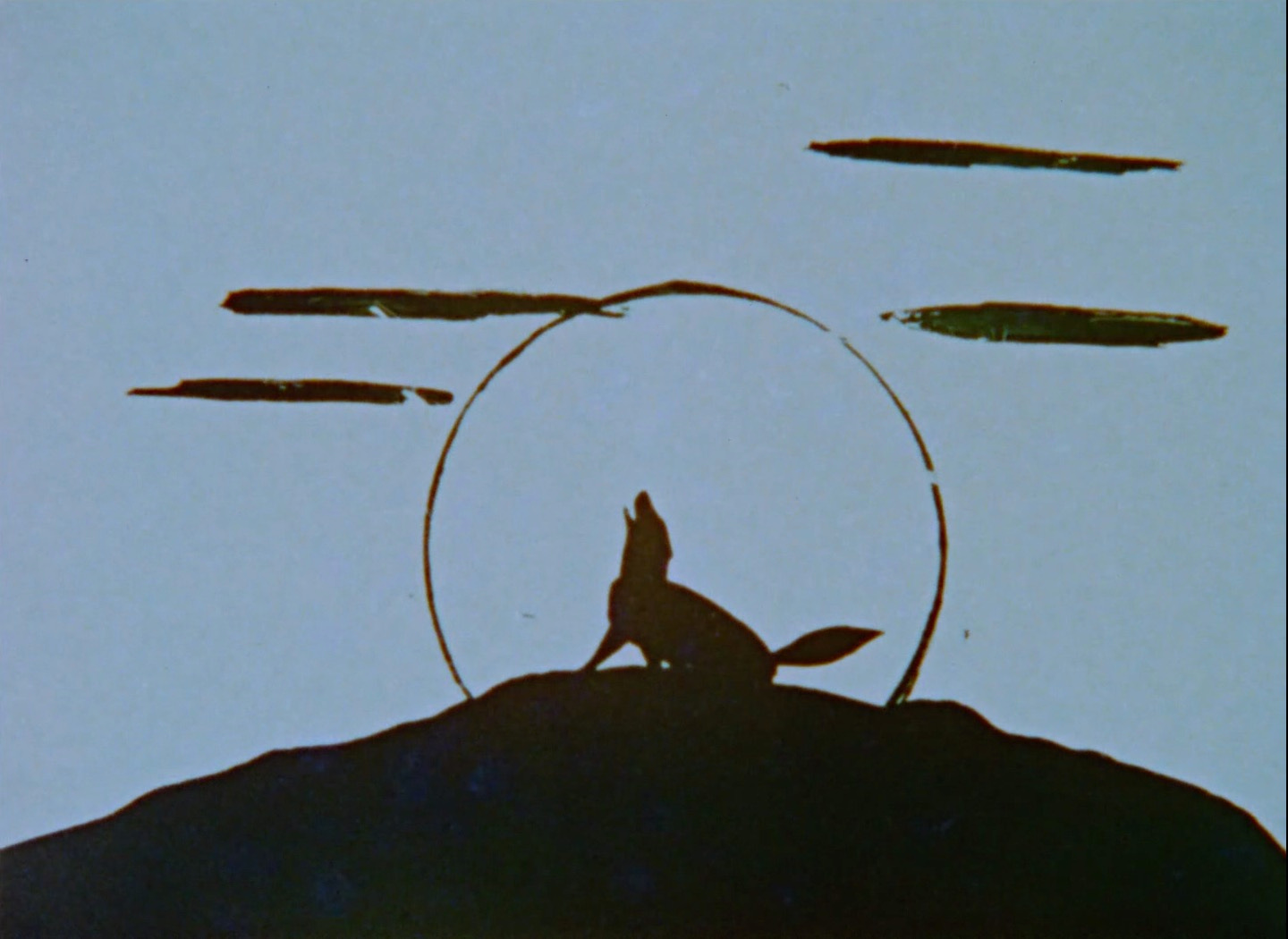

Animation from Cape Dorset (Solomonie Pootoogook, Timmun Alariaq, Mathew Joanasie & Itee Pootoogook Pilaloosie; 1973)

Animation from Cape Dorset is a collection of 16 short films produced during the first year of an animation workshop at the titular locale, which is now known as Kinngait. Made at the animation studio Sikusilmarmiut (“The people who live near the Sea Ice”), these works are important historical artifacts that showcase a wide range of animation techniques, from pixilation to rotoscoping to sand animation. What stands out is the way these artists used these methods as different vehicles for storytelling. A film using photographs helped put actual people and faces to the stories being shared, while pixilation could instill a work with an otherworldly aura by putting the human body and other objects in impossible positions. The same could be said for the drawings, which are delightfully straightforward, versus the sand animation, which could see animals constantly morphing. The folk music is a highlight too, but the best vignette in Animation from Cape Dorset is one that depicts a boat ride. It uses strobing effects, and the flickering images provide a delightfully avant-garde spin on a simple animation while serving to convey both the energy and severity of the task. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch Animation from Cape Dorset at the NFB website. Find more information about Mosha Michael at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

all-around junior male (Lindsay McIntyre, 2012)

Inuk filmmaker Lindsay McIntyre shoots on 16mm and considers her practice to be a collaboration with the material she handles. That’s evident in all-around junior male, an eight-minute portrait of Nunamiut athlete Sean Uquqtuq as he participates in a traditional Inuit game known as the one-foot high kick. McIntyre makes the most of the medium, with golden hues and various scratches imbuing the work with a sacrosanct atmosphere. Uquqtuq’s face and body are sometimes obfuscated, blending into the landscape as an abstract blip, while at others his face is shown in close-up. Given that the one-foot high kick was sometimes historically used to indicate a successful hunt, this maneuvering between different levels of detail is an apt symbol of the act as 1) a celebration, and 2) a reminder of one’s relationship with their environment. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch all-around junior male at Vimeo. Find more information about Lindsay McIntyre at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Bocamina (Miguel Hilari, 2019)

Miguel Hilari’s newest film, 2022’s Cerro Saturno, finds the Aymara filmmaker drawing comparisons between the Bolivian mountains and the people living there. Shooting in black and white, he flattens people into their silhouettes, their bodies reduced to colors and lines like the spaces he captures: the people and their land, he implies, are inextricable.

This idea has roots in his lovely 2019 short Bocamina. He takes a painting of a city, Miguel Gaspar de Berry’s Descripción del Cerro Rico e Imperial Villa de Potosí (1758), and after zooming in, slowly tilts the camera up so we can get a sense of the mining town’s vast expanse and the mountain’s grandeur. As we move between shots from inside a mine and a school, we’re confronted with static close-ups of these local people; as viewers, we think of the stories their faces hold now and will hold in the future. We also move through a series of different interactions with images: children find their homes in the painting, write down materials that the miners would bring, and share other thoughts about the profession. Young miners then hold portraits and discuss how their people have been exploited, and how money can seemingly come and go. This film, which is constantly revealing the meaning that images have, situates mining in a specific context. With its forced labor of Indigenous people, Potosí is said to be “the first city of capitalism”; these two things are, of course, irrefutably linked. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch Bocamina at CiNEOLA. Find more information about Miguel Hilari at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Ceremonial (Caroline Monnet, 2018)

Algonquin filmmaker Caroline Monnet merges 8mm, 16mm, and digital film into a psychedelic collage in Ceremonial, a three-minute short film depicting a man in the forest. He strikes a drum, sings, chops wood with an axe, and walks backwards down various paths. It’s clear from the film’s title and the man’s garb that there is some sacred ritual taking place, but nothing is explained. The clanging soundtrack—an intense electronic soundscape featuring the aforementioned drum—makes this less of an instructive work than a chance to appreciate the controlled calamity: handheld camera movements, kaleidoscopic images, rapid cuts, and numerous color filters.

Compared to Mobilize (2015), the other Monnet film in this program, there is a decidedly more unclear narrative taking place here. And that was Monnet’s intent: she wanted to call into question the need for “outsiders” to document and understand Indigenous practices. There is an unceasing debate about documentaries and the need to provide explanations for what’s onscreen, and whether directors should feel okay letting images speak for themselves. What I never really see brought up is: Why do outsiders even have to know this? And why should a film be the beginning and end of your education on a certain people, culture, or custom? I kept thinking about that while rewatching Ceremonial, a film that Monnet lets remain an ambiguity to most people watching, but allows to be something more meaningful to those in the know. It combats a pernicious repercussion of documentaries in general: the notion that viewers actually understand something fully after watching minutes or hours of footage. Don’t kid yourself. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch Ceremonial at Vimeo. Find more information about Caroline Monnet at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Black Rectangle (Rhayne Vermette, 2013)

One of Rhayne Vermette’s most interesting short films is Black Rectangle, a kinetic 90-second collage of “16mm found footage.” Drawing inspiration from Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square, a monochromatic painting that first served as a stage curtain, the Métis filmmaker assembles strips into varying sequences that resemble Venetian blinds. On a strictly experiential level, it’s thrilling to see these strips of color—from lavender to cerulean to a honeyed amber—peak through cracks of a black wall before rupturing into a kaleidoscopic dance. The editing and pacing are precise, and the film’s greatest feat is in grounding its frenetic energy with an array of perceptible motions. We see how smooth its downward movement can feel, or the playfulness of strips overlapping, as if they’re awkwardly hurdling one another, but there’s also pure delight found in the contrasting “tempos” and rhythms of the vertically aligned strips with the horizontal ones. The noisy, granular soundtrack captures all this intensity at a similarly large and microscopic scale.

This ability to overwhelm and invite careful viewing is the link back to the Malevich work, but there’s also something to be said for how the painting’s age has transformed and expanded its meaning over time. After Black Rectangle was created, a racist joke was found to have been inscribed in Black Square, which revealed it was a direct reference to a comic by French artist Alphonse Allais. I had seen Black Rectangle in the past, but seeing it in a program of Indigenous works that partly deal with memory’s ongoing development, the flux state of art itself, impermanence vs permanence, and racism’s dominance in culture, Black Rectangle stands out for evocatively capturing all those ideas in the shortest amount of time. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Watch Black Rectangle at Vimeo. Find more information about Rhayne Vermette at the ThousandSuns Cinema website. Read Joshua Minsoo Kim’s interview with Rhayne Vermette at MUBI Notebook.

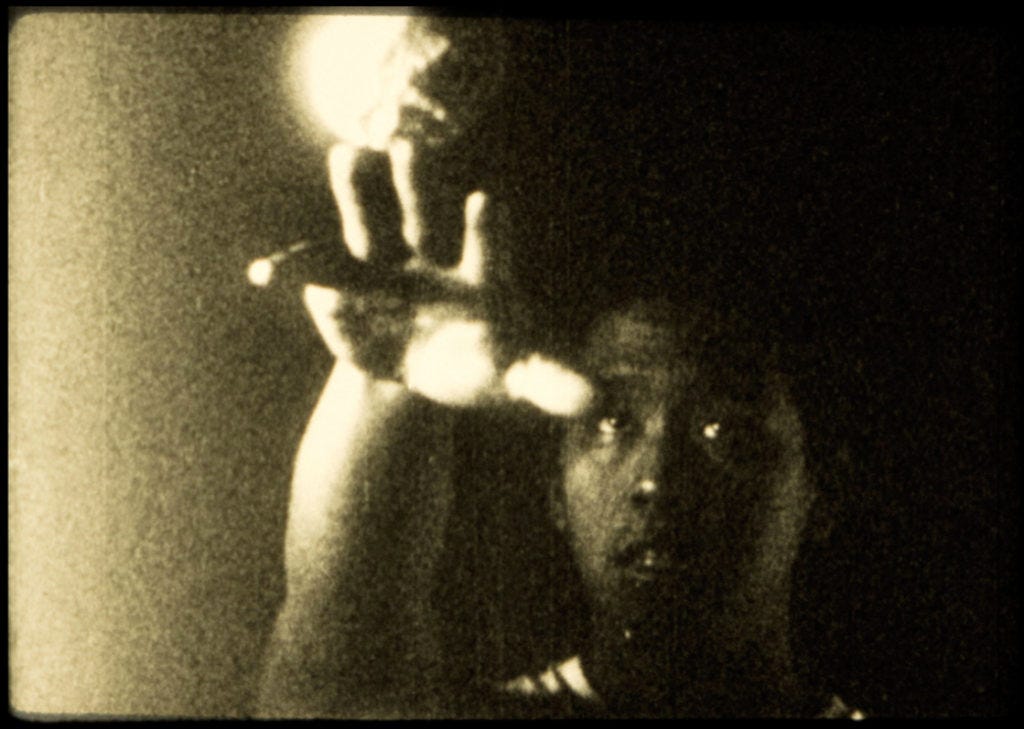

I Want to Know Why (Dana Claxton, 1994)

Dana Claxton’s short video piece I Want to Know Why is soundtracked by “Indian Head,” a song by Russell Wallace, an Indigenous musician who was part of Dreamspeak (“a group of Native Artists during the late ’80s and early ’90s that liked electronica and dance music,” according to his YouTube channel.) His track is, notablg, a generic slab of ambient house. You can listen to its identifiably ’90s production and soak in the equally generic images of Indigenous figures and iconography. But such banalities are a sleight of hand, coaxing the listener with Claxton’s own voice, which start off similar to but not quite like any sort of house vocal. Before long, the Hunkpapa Lakota filmmaker repeats the titular line with ferocity, recounting loved ones who’ve starved and died. As shots of the Statue of Liberty appear, only to get split in two via edits, its inscription’s false promises ring loud and clear—America does not care for its tired and poor. Sometimes the only way to lodge that message into people’s brains is to rupture familiar comforts, be it a house track or a national monument. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

More information about I Want to Know Why can be found at Vtape. Find more information about Dana Claxton at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

✧Ⓑ☠☻Ⓛ♡Ⓞ✇☟Ⓞ☁☽Ⓓ✰ ⓜⓐⓣⓔⓡⓘⓐⓛⓢ✦ (Fox Maxy, 2021)

Fox Maxy (Luiseño/Payómkawichum and Diegueño/Iipay Kumeyaay) is one of the most confounding directors of our time. Seeing their works in the context of different avant-garde film programs has been a delight because their work is far more playful and attuned to a style of film grammar befitting a younger generation raised on the internet. They also use a variety of contemporary music; on Blood Materials, it’s Sade and Azealia Banks and Digable Planets. At one point, a pitch-shifted version of “Take Me Home, Country Roads” is played as shots of an oceanside town has edited images flit about, warping into digital detritus. The queasiness and lack of stability is the point. As images, objects, .gifs, and landscapes are constantly swirling and stretched, the intensity of this sense of displacement and colonized land becomes something both deeply felt and unable to be grasped in its entirety. And yet, there is joy to be found amid the uncertainty and haze, with close-ups of flora or time spent with their “favorite cuzn Toby” being especially moving. Keep looking for beauty—it’s still in there somewhere, despite the mess. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Find more information about Fox Maxy at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Three Thousand (asinnajaq, 2017)

Tanya Tagaq and Celina Kalluk’s singing can be heard in Inuk filmmaker asinnajaq’s Three Thousand. My primary understanding of katajjaq (Inuit throat singing) is how it is traditionally a vocal game among women, and my favorite recordings of such acts bring that reality to the fore by including laughter. Tagaq, its most famous current practitioner, has found ways to fold that vocalizing into a variety of genres, and the cinematic ambience here is befitting a work that meditates on Indigenous past, present, and future. The foley work is exceptional, layered with serene instrumentation and the sound of breath: a constant reminder of the life animating all these images. As we witness industrialization arrive, the music takes a severe tone, and the “romanticism” of any archival footage seems to dissipate into current realities. asinnajaq ensures the montage remains nimbly paced, lingering on faces and landscapes and animals to give an impressionistic sense of an entire people’s history. But animation is also woven in to envision an ideal future, and the music begins to sound idyllic again. Three Thousand begins with voiceover: “It seems inconceivable as I live now but I will die, and there will be a world where I don’t exist.” It’s a striking acknowledgement that reveals that she will never stop wielding her imagination—a tool that is, and always will be, revolutionary.

Watch Three Thousand at the NFB website. Find more information about asinnajaq at the ThousandSuns Cinema website.

Thank you for reading the twenty-first issue of Film Show. Agitate, educate, organize.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.