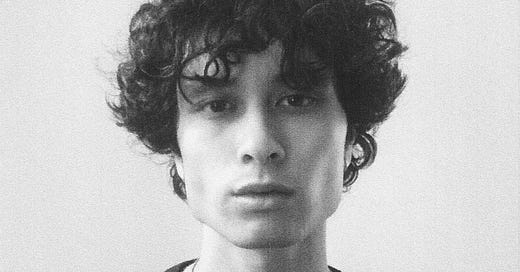

Film Show 048: Julian Castronovo

An interview with the Chinese-American filmmaker about his film 'Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued', which was the highlight of this year's IFFR

Julian Castronovo (b. 1998) is a Chinese-American filmmaker who was born in Miami and is currently based in Los Angeles. His debut feature, Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued (2025), premiered at this year’s edition of the International Film Festival Rotterdam. It was also the highlight of the entire festival, delivering a microbudget detective story that grappled with the slipperiness of authorship and identity. Described by Castronovo as an “inverse autofiction,” the work sees the director in the lead role as he learns of an art forger named Fawn Ma. Through miniatures, slideshow presentations, and laptop-camera footage, he invites the audience into a rabbit hole that constantly brings into question the fictitious nature of its proceedings. Its ingenuity and humor mark it as the first great Gen Z feature film made by a Gen Z filmmaker. Those in New York can watch Debut later this month as part of the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight. Joshua Minsoo Kim spoke with Castronovo on February 15th, 2025 via Zoom to discuss Yoko Ono, his debut’s $900 budget, and how to apply the logic of literary modernism to cinema.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I know you grew up in Wisconsin, were you also born there?

Julian Castronovo: I was born in Miami and lived there for a few years and then moved to Wisconsin when I was 5 or 6. I say I’m from Wisconsin.

What was it like? Do you feel like there’s anything notable about growing up there?

The most interesting thing about it was how uninteresting it was. It was a vision of American childhood that’s become almost obsolete. I went to this high school that had this football and cheerleader dynamic, which I was slightly removed from—I always had this “I hate this town!” attitude. I went to Brown for undergrad and I remember being ashamed of being from this Midwestern town, but I’ve grown to be proud of it.

What was the reason for this initial shame?

You get there and meet these people who seemingly know much more about the world.

I like the importance of the word “seemingly” there.

Yeah (laughter). When I was 19 or 20, I drove from a friend’s house in Chattanooga, Tennessee back to my hometown in a day. It was 11 hours or so, and there was construction on the freeway so I had to go on this small state highway that was a dirt road for a long time. I drove the length of Illinois and went through town after town that looked exactly like mine—like, here’s the gas station, here’s the high school. And then when I got to my hometown, it felt like a nice experience. All these towns felt the same and one of them was mine.

Do you mind talking about your experiences at Brown? What things were helpful and what things were stifling, and how did that affect your practice? I know you studied Modern Culture and Media.

I don’t know how much of it was the institution in particular or being 18 to 22 and becoming a person (laughter). But that program completely shaped my practice in a really fundamental way. I had important mentors, and in a way it was kind of crazy. I was 19 or 20 and I walked into my first film class, as a freshman or sophomore, and it was RaMell Ross teaching. He became an important source in shaping my thinking. This was before Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018) had come out, before Nickel Boys (2024). I never sought out these people who helped me in these profound ways, but just kind of wandered into contact with them—I was lucky. There was RaMell, there was my teacher Jennifer Montgomery who was really important in shaping my work, and then in graduate school, Juan Pablo González was really helpful and generous.

Can you pinpoint specific things they said or did that was instrumental to your practice?

In a way, all of them taught me to be suspicious of images. They taught me how to think about form.

Your first film was your thesis film, Hannah’s Video (2020). I appreciate that there’s this aspect of performance that feels like a throughline into Noise (2022) and also Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued (2025). What were you trying to explore there?

I think there is a throughline. To me, the throughline is an interest in a ritualized performance, or in posing. I think I’m interested in this quality of fiction filmmaking where even filming something fictional has a non-fictional aspect. As in, a fictional image is a non-fictional document of the performance.

Right, and I think that’s something that’s even more explicit in Noise because it’s centered around an audition process. What interests you about this tip-toeing between fiction and non-fiction?

There is a lot to be said about what some people might call “post-fictionality.” I’m interested in this slipperiness because of my own shortcomings as a writer and director. I think if I was a better, more imaginative person, I could just think of a fictional thing and make it. In response to what I have felt to be limitations, I have found it to be an interesting strategy to confront those things in the work rather than try to work around them.

What does it mean to be “more imaginative”? Why is that the phrase you’re using there?

Maybe it’s a bit of self-loathing. Let me take a step backwards. I work on this boundary between artifice and reality, and this is a very simple answer, but I make work about that because it’s what I’m interested in. If other people are much more interested in interpersonal relationships, they make films about those subtleties. I guess I made a film about the things I have the most to say about. It’s a kind of stupid answer, but it’s the truth.

With this slipperiness that you’re interested in, are you at all invested in Twitch streams or what people are doing on TikTok or IG reels? I’m thinking about the ways in which people perform in front of their phone camera—or their computer with Twitch—and how that’s something that people are interfacing with more regularly today. And these people are presenting “themselves” to an audience, too, which is sometimes live. Do you care about any of this and the parasociality of it all?

I don’t think that social media should be viewed as some drastic break in what it means to be a person, what it means to be performative. In many ways it’s a continuation of what has always been the case, and I’m more interested in this aspect of “what has always been the case.” To me, “pretending to be the person you want to be” is a very similar activity to “being” the person you want to be.

I think about this all the time. I think there’s something very incredible when you realize that if there’s someone you want to be, you can just be that person. It sort of collapses this notion of aspiration versus reality. This feels like self-help talk in a way, but there’s an interesting thing that happens when you understand that you can just be the person you want to be, even if you feel like it’s not an “authentic” version of yourself initially. And I mean, I guess musicians and actors talk about this but it’s also just something you can practice in your “normal life.”

The vernacular phrase to express that is just “fake it till you make it.” But I think this logic of pretending and being—that type of metaphysical game—was the point of origin for Debut. I thought that by inventing a certain type of fiction, becoming a filmmaker and making a film would be a self-generating endeavor.

Can you explain why it’s self-generated?

I’m gonna express this in a roundabout way, in literary terms. There’s all this talk these days about the notion of “autofiction” for young American writers. To me, I saw this film as an “inverse autofiction,” and by “inverse” I mean rather than taking my life and distilling it down to a fiction by the process of changing little things, I could invent a fiction that would require reality to form around it. The film generates real evidence of its story, and it’s a film built around evidence. For example, in the film, Julian Castronovo goes to Prague. Because that had to happen for the film, it had to happen in real life. The fiction demanded that Julian Castronovo go to Prague, and then all these real things that testify to that were created.

So you didn’t plan to go to Prague before thinking about the film?

Yes, correct. So because the fiction demanded it, now there’s this real evidence. Here’s this Scandinavian Airlines ticket that has my name on it. My footprint is really in the mud in some Czech field. The fiction generates real evidence.

Something I always recommend to people is to live in a way where you’re forcing yourself into positions that are surprising, that you wouldn’t be in otherwise. And it’s interesting when it doesn’t feel like you’re the one making that decision, exactly. It feels somewhat external.

That’s why I made the film in the way I did. I felt that making a film otherwise would be impossible—there had to be some semi-external force, which is to say the film itself forcing me to make a film.

Why is that something you wanted versus having the entire idea for a film in the first place and making that?

I felt that I was incapable of advocating for myself in a way that would make it possible. I think making a film in this typical, linear idea of film production—where I have my idea, I write it out, I get all these people together and some money to make it—requires a confidence in one’s own ideas that I simply don’t possess. It was an ironic thing, in a way—an ironic response to certain trendy things that young filmmakers are asked or tasked with these days. “Why are you the right person to make this film?” is always what grant applications will say. So I think I wanted to take that logic to the most extreme: How could I make a film where I’m the only person who could make it?

That’s so good. That’s something that comes up a lot in the conversations I have with artists. They’re having to get these grants and in writing these applications, they put themselves and their art into a box, and of course a lot of it is related to identity politics, which can be stifling in the way you want other people to approach your art.

I think American independent filmmaking is—and has been—very invested in authenticity and identity. I was much more interested in the opposite things. That is to say that I was much more interested in artifice and the way identity itself is this deeply performative endeavor in the first place. I set out to work in a way that was opposed to that, and maybe aligned with it at a certain point. My sensibility is that artifice is much more compelling than authenticity.

I appreciate that you don’t see this dichotomy between artifice and authenticity, that they’re always intertwined in ways we may not fully recognize. This makes me think of the different artists that you’re inspired by and reference in the film: Yoko Ono, Sebald, John Ashbery, Pynchon. These are all heavyweight names, of course. Were these artists specifically chosen because they tackle similar ideas, or did you mention them because they felt right for the story that was unfolding?

Their influence pops up in different ways. I’ll start with the literary modernists. I was interested in applying the logic of literary modernism to cinema and how images create meaning. For the most part, cinematic images create meaning through a dialectic, as any film major will tell you after their freshman seminar (laughter). Here’s one image, here’s another, and in conversation they’re creating meaning. The logic of literary modernism is that representing the world is impossible, but you can approach it by creating long lists of things. The theoretical term for that would be parataxis.

You read Joyce, and all these giants of literary modernism, and they have a similar rhythm. Short little words with lots of “and”s and stuff. “Eileen had hands that were long and white and thin.” And they’re very obsessed with little objects all the time. Sebald is a huge influence for me, and his obsession with little objects is, I think, taken from [Gustave] Flaubert. I felt that this obsession with little objects resonated with the kind of forensic examination I was doing. I wanted to create a film that was trying to do “here’s an object, here’s an object”—this sequential, little object logic of little things, as opposed to a dialectical logic, which I eventually abandoned. The images function as an inventory instead of some other type of representational apparatus. That was my attempt at formal innovation.

I think for the artists… I didn’t have a good reason for wanting to be like Yoko Ono aside from the fact that I like her work. I think it had to be performance artwork, because it was part of the central question about authorship and performance. “What does it mean to make an artwork and say it belongs to someone else?” The question I was interested in was, “What is a forgery of a performance artwork? Is there such a thing?” I think I just wanted to make artworks like that, and knew that I couldn’t make them, but I could make them if I had this other mechanism of attributing it to someone else. The thing I’m interested in is a question of what it means to be moved by art, to find art good or bad, and the bearing of authorship upon that judgement.

In terms of the identity of the author and how that impacts your understanding of the work?

Yeah. I think I have an equivocal understanding of that where I’m not on one side or the other. What’s the phrase? “Severing the art from the artist”?

Is there any clarity you came out of all this with? Or did you have more questions?

Oftentimes, after I screen this film and I’m there in the room, people are often unsure if the artwork of this artist, Fawn Ma, is real. I think they like it better when there’s certainty.

Certainty about the fact that Fawn Ma is a real person or isn’t?

Either way. They don’t like not knowing. I think people feel affirmed or comforted when I have to reveal that I’ve made them all.

What sort of things did people ask at screenings?

I think at both screenings, someone straight-up asked, “How much was real and how much was fake?” which I really liked. Those questions prompted me to realize that way more of it was real than I thought was real. I said, “It’s a fiction that Julian Castronovo went to Prague,” but at the same time it’s not a fiction because I did do that. I think for the most part, people “get” it—I don‘t think it’s a super difficult film. This is actually one of the things that I thought hardest about when I was beginning to make it: I wanted so badly for it to work on a purely narrative level. That was the most important thing to me. In my own thinking, that type of thing comes last, but these tropes of detective stories really made it easy. Detective stories have such a clear logic provided by clues where one leads to another, and it becomes very easy to follow. I also tried to make my voiceover, my narration, super repetitive and explicit about how this thing led to this other thing. I think you can only begin to get away with the more interesting things when one has already made a coherent story.

How so?

I think I would find a film of pure formal experimentation to be unwatchable if it was not grounded in narrative, especially one of this length. You could make a very short film of image experiments, but to make an experimental film of this length, there has to be something familiar as a spine.

Are there specific films that you were looking at that allowed for confidence in knowing that your film could work?

One of the things that I’m most proud of is that I didn’t know it was going to work (laughter). The entire time, I was so anxious about it. Then I read this quote by John Cage that was so comforting to me. He was talking about music, but he said, “Something is only experimental when you don’t know what’s gonna happen. If you know what’s gonna happen, it’s not an experiment.” I was making this whole film, and I didn’t know if it was going to be coherent at all, so much so that when I was almost done making the film, I shot another short film because I thought it was going to be so incoherent. I thought I was going to graduate from film school having nothing to my name (laughter). At the same time, I’m very proud of the fact that I worked in a way that was sincerely in this spirit of experimentation, where I didn’t know if my ideas would work.

That’s awesome, and there’s a real satisfaction to it when it’s done. It feels like something that’s bigger than yourself. Did it feel like you were part of some larger thing?

I don’t know if I see myself as doing a greater service to art (laughter). I think the broader thing for me was inventing a vision of a filmmaking practice that I could bring with me into the future. I wanted it to resemble a studio practice where you can wake up every day and work on stuff with your hands, which is why I wanted to do this object-oriented approach, because I was forging a lot of this evidence to be semi-antiquated, giving it effects of age. And I just wanted to make a film in a way where I felt like an artist.

What are your qualifications for feeling like an artist?

Waking up and working on art every day. In the methodology of filmmaking, one does not feel like an artist all the time. When you write a screenplay, you haven’t made a film, you’ve only made a screenplay. And then maybe several miracles happen and you get to shoot for 10 or 15 days. What I wanted to do was wake up and make things, and make images, every day for months and months. I almost built the film around that desire to work on it in relative solitude, just in my apartment.

Something I wanted to address is the $900 budget that’s mentioned in the descriptions for the film. Are you able to break down what those $900 were?

Really, the only significant expense I had was that I paid my voice actor, my narrator. At CalArts we can get $1000 reimbursed, which is nothing to make a film. I was saving my receipts (laughter). And then the rest of it was from making miniatures and documents.

This $900 figure calls into question what you even consider part of the budget. You went to Prague—was the ticket counted in that?

The $900 is a bit of a convenient figure. It’s under $1000, which is a cool little fact that I get to say. It was an imprecise method of counting. Like, if my room is my studio and the location that I’m filming in, should my rent be included in the budget?

This is all interwoven with the other things that we’ve talked about. It’s this impossibility of precision and accuracy.

The film itself is also very forgiving of imprecision, inaccuracy (laughter).

Is there anything we didn’t talk about today that you want to mention, or anything that you always wanted to be asked in an interview?

That’s a good question. I don’t think so—this was a good interview. I think we hit all the stuff that I wanted to cover. The thing is, I think it’s a fairly dense film, and since it’s my first film, all of my ideas went into it, everything I’ve ever been interested in. So there’s lots to say about it, but I think it works nicely as a standalone document that in some ways is better without me tracing every detail. It’s nice to have it stand without explanation.

People always talk about how a debut film or album will be something you’ve prepped for your entire life, and how one’s second work is then a tricky thing to navigate. Like, “What am I going to explore now?” Have there been any struggles with the next feature you’re working on?

I don’t feel I’ve exhausted my resources. If anything, I feel invigorated by what aspects of Debut felt exciting to people, and I’m thinking about how I might work with those on a slightly bigger scale or in a slightly different mode.

I end all my interviews with the same question: Can you share one thing you love about yourself?

My film is full of things I love and hate about myself (laughter). One thing I love about myself is my memory. I have a very good memory, but I can’t recall a particular time it came in handy.

Julian Castronovo’s Debut, or, Objects of the Field of Debris as Currently Catalogued premiered at IFFR. More information about the film can be found at Castronovo’s website. Debut is also playing as part of the Museum of Modern Art’s Doc Fortnight—information for the screenings can be found here.

Thank you for reading the 48th issue of Film Show. Make it till you fake it.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.