Film Show 043: Antoinetta Angelidi

An interview with the Greek filmmaker in light of receiving Prismatic Ground's Ground Glass Award. She talks about her childhood, her approach to sound, and the inspirations behind her unique films.

Antoinetta Angelidi

Antoinetta Angelidi (b. 1950) is a pioneering avant-garde filmmaker who was born in Athens, Greece. From an early age, Angelidi was interested in the arts, spending much of her free time drawing and painting. When she was older, she had a dream that led her to pursuing architecture as a way to connect the medium with the wider universe. Another dream, however, encouraged a transition to filmmaking. Her debut feature film, Idées fixes / Dies irae (aka Variations on the Same Theme), was released in 1977 while she was a political refugee in Paris. Inspired by Lettrism and avant-garde filmmakers like Michael Snow, the film would reveal her ongoing interest in the relationships between language, image, and sound.

In 1980, she shot 121280 Ritual, which features intimate footage of herself on the day before giving birth to her second child. She was interested in leaving documentation as she believed she would die during childbirth. This experience, along with others in her past, would inform the surreal, emotive, and feminist masterworks that she released in following decades: Topos (1985), The Hours: A Square Film (1995), and Thief or Reality (2001). The latter film marked the first collaboration that Angelidi had with her daughter, Rea Walldén. Walldén would film a documentary about Angelidi in 2023 titled Obsessive Hours at the Topos of Reality which, among other things, would see Angelidi talking about her experiences with blindness.

Prismatic Ground, an avant-garde film festival in New York City, is honoring Angelidi with the Ground Glass Award for her exceptional contributions to filmmaking. A retrospective of all her works is taking place throughout May 11th and May 12th, 2024 at Anthology Film Archives. More information about the films, the award, and purchasing tickets can be found here.

Joshua Minsoo Kim spoke with Angelidi on May 4th, 2024 for five hours via Zoom. Walldén served as the interpreter and contributed to the interview as well. Below, find a conversation between all three of us about Angelidi’s childhood, the political organizations she was a member of, the inspiration that she took from various painters and illuminated manuscripts, her interest in filming tongues, the process of finishing 121280 Ritual in 2008, and her thoughtful approach to sound and silence. For readability, the interview is separated into multiple parts.

Part One: Childhood and Adolescence

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I wanted to start off by talking about growing up in Athens. What do you remember about your childhood?

Antoinetta Angelidi: I want to start by saying that I lived in Athens until the age of three. Between the ages of three and thirteen, I was outside Athens in different cities— mainly in Thessaloniki and Patras, the other two big cities in Greece. And then I returned to Athens when I was thirteen.

I remember very well my three-year-old self and the house where I lived. So much so that I recently described the exact floor-plan to my aunt Iris, who is the only surviving sister of my father—she is something like 93 now. I have very vivid memories of that time, when I lived in the house of my grandmother Antoinetta. Antoinetta was the mother of my father, and we all lived there together: my father, my mother, the brothers and sisters of my father, and his mother. The earliest memory that I have is that I was always drawing. There is not a moment I remember when I was not drawing. Apart from that, I remember that, despite the fact that the house was full of people, mostly young people, I had a very strong relationship with the furniture. I spoke to the furniture and gave the various pieces of furniture names and had conversations with them.

When adults spoke, I understood what they said mostly by their facial expressions and the intonations of their voice. I wasn’t really understanding the words themselves. This is an experience that reappeared to me, in different forms, on three separate occasions. The first is when I was raped, about which I will speak later. The second is when I was in France as a political refugee and not speaking the language well. And thirdly, I have used this experience creatively when teaching and directing actors and actresses.

As a child, my uncles would put me on the top of bookshelves because I was moving around a lot and annoying them. I would look down from above and my uncles and aunt were drawing—they were students in the engineering school. I had this strange view from above of the heads of the people and their hands moving. It was only their heads and hands, and it was very quiet—only very few sounds were heard. This was an early, very strange view of the world, and I recalled these images later and used them for my filmmaking. Another experience I remember is of being locked in the bathroom when I was punished. It was completely dark, but while I was there, I would draw with toothpaste. All these images came back to me when I was in Paris. I realized that my material should be my personal experiences, and I decided that I would clothe my experiences with distorted images of paintings, I would put the paintings on my experiences like clothing.

What sort of conversations would you have with furniture?

AA: My best friend was the stove. I gave the furniture female names. So, the stove would be something like “Stovey,” the cooker “Cookerina,” and my grandmother’s stick “Stickie.” [Editor’s Note: the “stick” refers to a cane]. They all had names and they were my three best friends. What I remember is that later on, when I was five, the aunt that we talked about before told me that she met Stovey on the bus and talked to her. I replied to her, “Impossible! Stovey never speaks to strangers.” (laughter).

A little later on, they gave me a doll as a present. The doll had a head that was made from some hard material, but the rest was made from cloth. I was feeding her. And one day, worms came out of her mouth. I didn’t really like dolls after that (laughter).

Ah wow, that’s funny.

AA: My family then went to Thessaloniki. It’s where my brother was born and there was a lady taking care of us children.

Like a nanny?

AA: Yes, like a nanny, but she was part of the family. My mother came to Greece in 1927 from “Russia”, as they called it, which was the Soviet Union then and is now Georgia. The nanny was a relative who came to Greece later on. She was a single woman, and extremely religious. She had a distorted—in the bad sense—notion of religion. It caused me many problems because she was very oppressive. And while I was telling the truth, she would always accuse me of telling lies. This created a distance from reality for me. When I was seven, we moved to Patras. The reason why we traveled so much is that my father was working as an engineer in different factories.

What kind of engineer?

AA: Both my parents, my father and my mother, were chemical engineers. My father was working in different factories and my mother was working at the General State Laboratory. This meant that when my father was taking different jobs, my mother could follow him because the State has different laboratories in different cities. I was in Thessaloniki from three to seven, and a family tradition started between me and my father. Apart from drawing, the other joy of my childhood was part of the relationship with my father. He would take me to the factories where he worked, on Sundays. He had this habit of going to them on Sundays because they were completely empty; he liked to plan and see things by himself.

While my father was working, I would walk alone inside these factories. This is a very strong memory of great joy—I adored walking alone in these great, empty places. And this memory, which I carried with me, has been incorporated into my films. This is particularly obvious in Topos (1985), which was filmed in a big factory. What’s important is how I used this big industrial space: I put elements of a house in it, I put furniture in there. There were no walls, it was only the furniture that was taken and planted inside these spaces, and it was this feeling of the familiar and the unfamiliar at the same time—this feeling is important in my work.

You went to Patras later on, right?

AA: We arrived there when I was seven. At the age of ten, the most traumatic moment in my life happened: I was raped by my violin teacher. After that I lost my voice. I didn’t speak at all. But most importantly, I lost my ability to understand. I didn’t understand words—either spoken or written. Prior to this, even if I paid more attention to facial expressions and intonations, I could understand. But after this, voices became like a cloud of indistinct noise. For a period, I was completely cut off from understanding the world.

There was no help from anyone at the time. There weren’t scientists or psychologists or anyone we knew, anyway. There were no experts. I should note that this all remained a secret—I told my parents but they didn’t tell anyone. They simply changed my teacher, and that was all; nothing else was said. My father had this inspiration to use a kind of archaic form of storyboard in order to help me. He would draw pictures for me to understand words. There would be lessons at school and because I couldn’t understand what was being taught, he would draw pictures of the lessons to explain them. And it worked!

From then on, my parents and I placed this importance on my drawings. I would draw and draw and draw, and it became very central to my life. When we returned to Athens when I was 13, I could speak and understand again, but it was only something that I found through drawing and painting. I was having this huge explosion of creativity. What I understood in the process of gaining understanding again was that words can become images. And this meant that images could become words. This was something I would carry into my filmmaking.

Can you speak to me about being in Athens and the creative practices you loved?

AA: When I came to Athens, I found that I was able to express myself again in a more complicated, more complex way. I liked to draw very small things, like leaves—small, rotten leaves on the ground—and spiderwebs. These drawings were very detailed. I would also draw my face—the library had a glass door that I used as a mirror. I had this obsession with drawing, and it felt like there was somebody else inside of me when I was drawing. This obsession would continue with images from certain films. The most important film for me was Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1953). I did some of my best ever drawings inspired by that film. Some of those drawings appear in the documentary [2023’s Obsessive Hours at the Topos of Reality], and they appeared in a public exhibition for the first time last year. I had an obsession with Japanese painting and Chinese writing.

All of this happened in a very specific context. This was the early to mid ’60s, right before the dictatorship in 1967. This period has since been called “The Lost Spring,” which is the title of a novel written later by Stratis Tsirkas. To understand the context, after World War II, there was a civil war in Greece from the mid to the end of the ’40s. The decade after the civil war was very oppressive politically, and all my childhood was spent in this. At the beginning of the ’60s, democratization began and there was this explosion of creativity. It was all around, especially in the youth. Young people would go to the cinema to see the kind of films that people today would consider difficult. They would go to see Bergman, Resnais, the Russian avant-garde like Vertov. We had literature, poetry. It was then that Tsirkas wrote his most famous trilogy, Drifting Cities. There were also elements of contemporary music and visual art. It was a very fertile environment, and I was in my adolescence then. I was free. But then in 1967, the military junta came and everything stopped again, completely.

Do you remember what that was like? What memories do you have of that moment?

AA: Before I reply, I should note that my parents were both left-wing. They knew about politics and it was very central to their lives. My mother, in particular, had been in the Resistance [against the German Occupation].

So, what happened the day that the junta began? I was 17, in the second-to-last year of high school. I remember I was preparing for a test and my brother, who is four years younger, left for school earlier. He returned soon after because someone told him to go back home because there was a dictatorship. He comes and tells my parents, “Oh, there is a dictatorship,” and my parents are like, “Come on, go back to school, you can’t get away with this!” (laughter).

My mother said we should turn on the radio just in case. And when they did, there were military songs, because there was a military dictatorship. There was no television at the time, and all the radio stations only had military songs, like marching music. Later on, as a university student, I joined the youth “Rigas Feraios” of the Eurocommunist party; I was active in the counter-dictatorship resistance. I knew what I was doing by then.

What sort of things did you learn from political activism? Can you speak of its importance for you?

AA: The first thing to say is that in being left-wing, there was a feeling of solidarity. What was important to me was solidarity and reading Marx.

A bit of history: the dictatorship was seven years long and was divided into three periods. The beginning was very, very hard. The middle was a little less hard. It was a period where a lot of left-wing intellectuals expressed themselves, though not openly, of course. It was in latent ways. Even from jail or exile, they would write and translate. So, in the middle of the dictatorship, a lot of writing and art happened. And even some echoes from May 1968 came to Greece. And then there was the final part of the dictatorship, which was very harsh. It was in the middle period, after the division of the Communist Party, when I entered to the youth of the Eurocommunist side of the divide, which was called the Greek Communist Party of Interior. The youth of this party, which was almost more active than the party itself, had the name Rigas Feraios Youth. Rigas Feraios was a great intellectual of the Greek Enlightenment who had written some very moving things about freedom.

The point is that all of this was underground. The first leadership of Rigas Feraios was arrested in the first period of the dictatorship. They were given very harsh jail sentences. I was too young at the beginning of the dictatorship. In 1973, basically the last year before the end of the dictatorship, I was in the central bureau of Rigas Feraios, and our general secretary was arrested. I was given a message that I had to flee the country or enter the underground movement, to disappear from my house. I managed to leave the country and go to Paris.

When I was leaving and on the airplane, the police were in my house, and this is the house that we are in now. They were looking under mattresses to find evidence, but I didn’t have material at home, of course.

Amazing.

AA: If I didn’t escape, my children probably wouldn’t be born. If I got arrested, they would have tortured me. Some of the arrested women were sexually tortured and couldn’t have children afterwards.

Part Two: Idée fixe / Dies irae

We can start talking about when you first became interested in filmmaking. Your first film, Idées Fixes / Dies Irae, came out in 1977. When did you first get the idea that you could become a filmmaker? And what were your first experiments with the camera like?

AA: I decided to become a filmmaker when I was still studying architecture. It was in 1972 when I had a dream that looked like a painting by René Magritte. This painting had a very discrete movement. It was this introduction of movement inside a painting. And this was the beginning of my obsession with timing. When I woke up, I knew two things. First, I knew I would make films and would be a filmmaker. The second is what kind of filmmaking I wanted to do. I wanted to start from distorted, deconstructed paintings that would be transformed through the introduction of time. And this time, for me, was also sound. So, time, sound and movement are these things that are introduced into painting, and distort it to create films.

Initially, I would have a photographic camera. It was this Exakta camera (holds up her camera). As a student of architecture, I started photographing and developing film. But the first time I had a cinematographic camera in my hands was the first day at IDHEC, the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques [Editor’s Note: this is now called La Fémis], the film school in Paris. On the first day and at the first lesson, they gave us a 16mm camera and explained to the students how to take it apart and reassemble it.

I want to ask about the decision to move from architecture to film. Are there things that you found lacking in architecture as a medium that you realized you could find in film?

AA: I must note that I also entered architecture because of a dream. In that other dream was a gothic cathedral made of spiderwebs. The way that light passed through this spiderweb cathedral reminded me of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris and its stained-glass windows. It was magnificent and very beautiful. There were some more practical considerations, too. The Athens School of Fine Arts at the time was very conservative.

Unfortunately, I was a university student during the dictatorship. Things were rather oppressive and poor, aesthetically. Most of the interesting university teachers were arrested or had lost their positions because of their political opinions. The only interesting teacher that I had, was the famous Surrealist painter Nikos Engonopoulos. I formed a very close relationship with this professor of painting. What I dreamed of was architecture that would be in relation with the universe. I admired Stonehenge, for example. I felt that architecture should be a kind of opening to the universe, but I couldn’t really find that at the School of Architecture. And then came the dream that would make me turn to film.

Practically, I had not found a way to study film yet. I came to Paris as a political refugee. Initially, I went to Vincennes, the university that appeared after May ’68. I attended lectures in semiotics, psychoanalysis, feminism, and urban design. And what everyone—especially my comrades—advised me to do was a Ph.D. in urban design. It was very fashionable at the time for its political connotations and possibilities. I violently said no to all of that, after I discovered that there was a film school! (laughter).

Were there any benefits in studying architecture that you found useful in creating films?

AA: The important lesson from architecture was composition. I’m going to describe it in two levels. The first was the idea of composing as a whole, of having an understanding and perception of the entire composition. The other idea is that when you compose, you have some trace lines that organize the composition.

Right.

AA: I was first introduced to these trace lines—the kinds that organize and analyze compositions—in my lessons on the history of architecture. We were analyzing historical buildings by their axes of symmetry etc. I saw a continuation between what I already knew about painting and this. And then this continued into my study of the moving image. This, along with the fact that the composition is an entirety, a whole. In the school of architecture, we were often given as an exercise to conceive a composition of something big, very fast. Like, make an entire city in an hour, though obviously without details. Or you would make a village, or a temple. This vision of having an entire composition from the beginning and working on that—this is very important in how I perceive my filmmaking.

It is probably appropriate to add here that when I start a film, I enter a kind of time trap. It is this matrix where images are sucked in and taken in by time. So, this initial conception is always there, and during the creation of the film, I want and need to return to this initial conception, which is a kind of condensation of time. While I perceive my films as a whole, the elements inside are deconstructed, divided, disintegrated, dissolved. You have conflicts between characters’ movements and their gazes, between the way they speak and what they say, between different elements of image and sound. There isn’t harmony, but rather a juxtaposition. My compositions keep the elements of heterogeneity strongly apparent.

This makes sense.

AA: This is something that is included in the way I direct actors and actresses. I tell them not to identify their speech with the meaning of their words. I want them to keep a distance between the two. And this comes back to the feeling I had as a child where the style and the words were in conflict.

That’s super interesting to me and it is one of my favorite things about your films. When I first saw your films, I was enamored with how you’re essentially the only filmmaker I’ve seen whose works are so invested in exploring sounds and their meanings and separating the two. This is obviously related to text, too. With Idées Fixes, it’s clear that you’re interested in both sound poetry and concrete poetry. Were there specific musicians or concrete poets that you were interested in when you made this film? I’m thinking of that one image in the film where there’s the woman’s pelvis that has the text overlaid that is shaped like a box.

AA: I can’t write a script in the traditional way, with descriptions of images. This does not work for me—I can’t do it. What I do is collect images and dispersed words. And then I write my scripts as music scores. It is important, both the axis of diachrony and the axis of synchrony, as in music scores. I compose with material from different origins. In the case of Idées Fixes, for example, the words were from my dreams, from poetry, from advertisements, from stories. There is diverse material dispersed and then it is composed as a score. You have diachrony and then you have cuts of synchrony where you add things, you compose things on this axis. What I felt from the beginning was that dialogue, music, and noises were all in unity. These are the three parts of sound, as I learned later on from [film theorist] Christian Metz. It is this concept of heterogeneity, and the three elements of audio heterogeneity are conceived and understood as a continuum in my films. For Idées fixes, I collaborated with Gilbert Artman.

Minimalist?

AA: Minimalist, yes. I want to tell you about the different kinds of sounds we made and used in this film. One of the first things I told him was that I wanted the noises to be created from the repetition of words. There is this poem inspired by Lettrism, but we took this poem and we repeated the recording very fast, in a loop, to create the sound of cicadas. So, in the film, when you hear the cicadas, this is actually the poem played very fast (laughter).

Oh wow.

AA: The poem was created from the same phrase, which is “their men died relatively young.” What I did was substitute the order of the words. I’ll note here that of course, this was a linguistic game, and the different variations remained meaningful. So, the entire poem is different substitutions of the order of the same words. Another interesting part of the sound of the film is the part of the dictionary.

This is when you say “a-brastos, a-brektos, a-bros”?

AA: Yes. The prefix “a” in Greek is somehow similar to “an” in English.

It makes the word its opposite, right? Sort of like “anti-”?

AA: Exactly, exactly. What is interesting is the fact that this “a,” turns words into their opposites or into ellipses, like they are missing. It is equally a game of meaning and a game of sound.

Right.

AA: Gilbert and I played with that. I voiced the actual text, and also the poem we talked about before, that’s my own voice you hear. But we were basically playing music with the dictionary and a lot of metallic things. He had in his yard various metallic things, among which the most impressive was a bathtub (laughter). I would intone words from the dictionary and we would hit the metallic objects, and this created the sound that you hear. So, it’s this music created by the dictionary, voice, and bathtub (laughter). And of course, the written word becomes images. In this film, this idea of heterogeneity is very strong. It’s how when the sound of the written word is no longer present, it is still in some way a sound, and it has become an image.

And then we come to the other part, the visual parts of heterogeneity. (steps away and brings back a book called La Révolution surréaliste). This is a book I did have at the time, it’s an old book (shows a page with the heading “Les Mots et les images,” which features various illustrations of objects with text underneath them). The words and the images. It’s very linguistic. It was my inspiration for these games. The Surrealists were an important inspiration.

I love how there’s this understanding of spoken text for its sonic qualities. And obviously, there’s the text that’s written onscreen and an understanding of it as an image. But I also like how in the film you will intentionally divide the screen as another exploration of this sort of heterogeneity. You have the one image where it is completely black on one half and there is the person with the feathers on the other half. And then you have the one image with the men leaning down and then there’s a diagonal line splitting the image.

AA: Yes, you’re right. I want to say, I had this peculiar feeling of “What is film? What is cinema?”, when I made films, these were not things that I had seen elsewhere.

This first film feels especially playful.

AA: Yes, I think that the concept of playing saves us. Very recently, I read things that retrospectively made me understand this. These are very recent reads, like one or two years ago. I read [Donald] Winnicott and about the importance of playing, and how playing is a way for life to incorporate death, and to deal with death. And I read [Sándor] Ferenczi and how children and adults speak different words, different speeches, different discourses.

I have to ask, what do you feel is distinct about the Greek language? I know the other films you made were in Greek, but this first one had some French. Obviously, when we speak different languages, there’s a different personality we take on. When I speak Korean, I feel like a different person than when I am speaking English, and I’m wondering what speaking Greek means to you.

AA: For Idées Fixes, I chose to make half the film in Greek and half the film in French. I had in mind that the French wouldn’t understand Greek and the Greek wouldn’t understand French. This incomprehension was part of the intentionality of the film. It was a way to make them feel like immigrants, like strangers.

I have a peculiar relationship with language, mainly because of the period when I didn’t speak at all. When I started speaking and writing again in high school, I wrote well, but I wrote strangely, peculiarly. The teacher would read my essay in class, telling the class, “Look, there can be this different kind of writing.” What the teacher meant was that it was a poetic expression. It was not the kind of expression that you would use to pass exams. In class, the teacher would first read excellent essays of the typical, exam-passing style. And then she would say, “Look girls”—it was an all-girl school—“there can be a different kind of writing.” From the moment I started writing again, I could only express myself in language poetically.

What I’ve realized recently, studying my own writing and speech, is that I often skip the in-between links. People do not follow the continuation of my speech. There are missing links in the stream of my speech, but the listener does not necessarily know it. So, it is a constant situation that people do not understand what I am saying.

Interpreter and daughter Rea Walldén: May I add as a comment here, this is why I’m a good interpreter of her words—it’s because I know what is missing (laughter). Early on, I learned this kind of speech. It’s a constantly poetic speech, the structure of which is unexpected (Angelidi and Walldén embrace).

AA: I had a huge difficulty learning any foreign language. It is even difficult to speak Greek. I learned French by speaking with the other students in the film school. If I want to speak French, I have to enter into a universe of words, so that the words appear. Because of my distance to language, and also because of the fact I was very good at mathematics, I was very good at syntax. I understood Ancient Greek texts very well because I would look at them like mathematical constructions. It’s not by chance that in Topos, the voice says “our birthplace is not the place we were born”. It’s not that I belong somewhere else, there is just no initial country, no place of beginning.

When you made Idées Fixes, had you seen any structuralist avant-garde films or Fluxus films?

AA: Underground films came to Paris for the first time in 1976. It was a collection of films under the title “Une histoire du cinéma,” which was curated by [Peter] Kubelka. Our teacher at the film school, Noël Burch, told us “Go! Go and watch the films!” I went and watched everything that was screened. I was really moved by Michael Snow, and in particular, La Région centrale. So, this was an inspiration for me.

What about that film was inspirational for you?

AA: What inspired me was the mathematical logic of this film. The camera moved from the sky to the earth, did an entire circle and then there was a “clack!” The sound, the “clack!” And the camera would change by one degree and this sound was very important. The camera was recreating the space of a ball, of a sphere. And the time was real—you saw the night come. And there was a continuous sound in the background. This repeated movement from the sky to the earth and then the clacking sound, it had a mathematical logic which spoke to me.

Beautiful. I really love Michael Snow’s films for his use of sound. Obviously, I like how he uses his camera and everything too, but you’re one of the only people in my life who, in talking about his films, are specifically talking about the sound. It’s exciting for me to meet someone who is also excited by that (laughter). Is there anything else you want to say about your debut film?

AA: In La Région centrale, we can find this questioning on the notion of time. The initial shot of Idées Fixes incorporates the notion of the time that passes. It is a very structured image, a long static shot; and it allows the time to pass, it allows the intrusion of accidentality, of randomness. You have the change of the light, you have the movement of the leaves, and you have some cats that cross the street and cross it back, creating huge events. It’s a document of reality.

I love the opening of that film because it primes you as a viewer to get into this mode where you are more attentive. The camera is fixed and you are noticing the time pass. It becomes an instructive moment for the viewer.

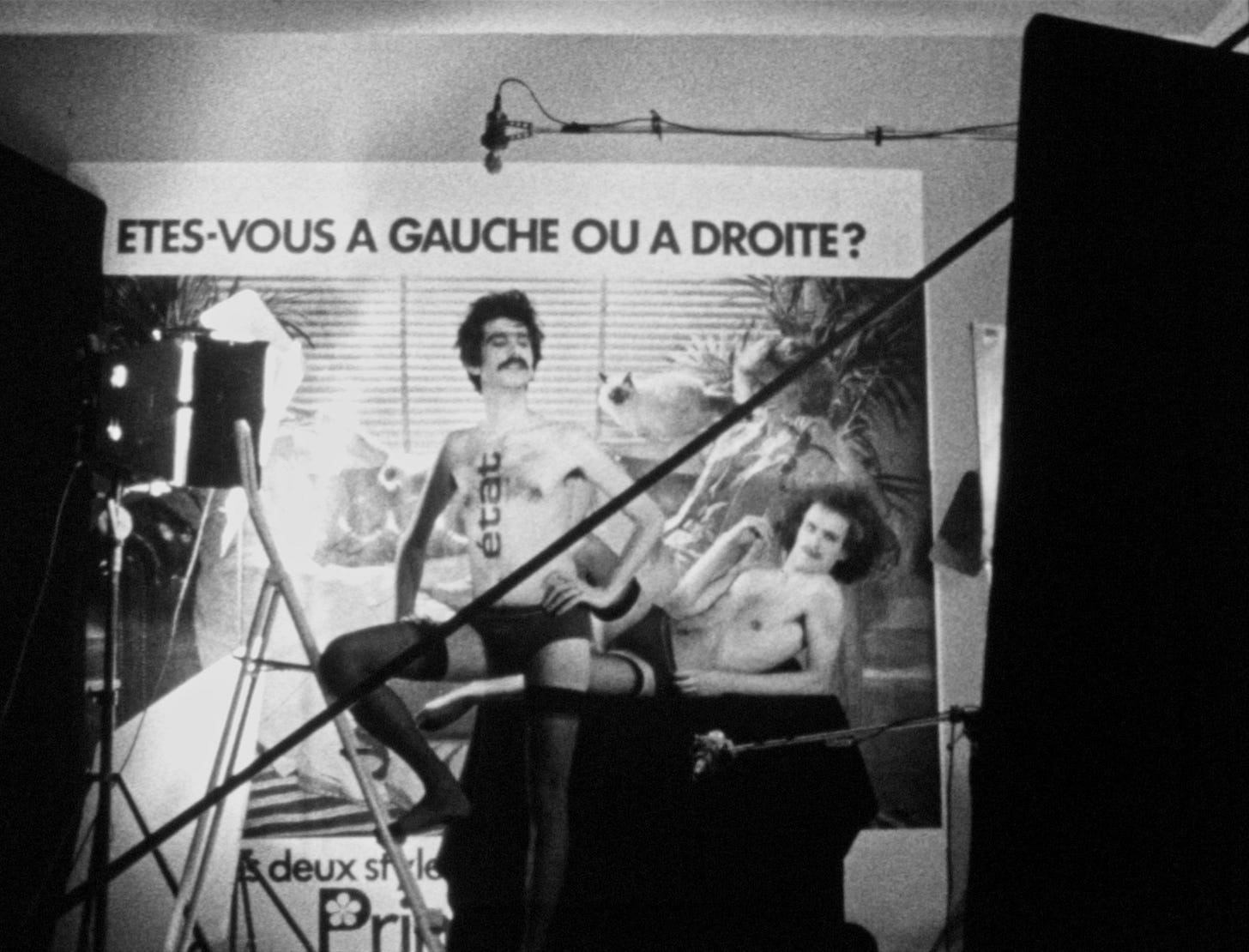

AA: I’m very moved that you say that and that you felt it and understood it. Not many people do. You actually came to understand that this was my intention. The idea was to give the opportunity to the spectators to contemplate. It is a mode of contemplation on the image. This mode is in complete contrast to the other long shot in the film. The film basically starts with a very long shot, and then it has another one in the middle which, unlike the first one, is not contemplative at all. It’s also static, but it is very noisy and very confusing. If the first shot was a reference to Surrealism, the second was a reference to Hyperrealism. It was a game with history of art, as you understand. This second shot, I intended it to be oppressive. If the first one is contemplative, the second one is oppressive.

Part Three: 121280 Ritual

I want to talk about your next film, 121280 Ritual. I know that it wasn’t finished until 2008, but it was filmed in 1980. What you just said about Surrealism and Hyperrealism and the playfulness of juxtapositions, it reminds me of the text at the end of Ritual: “To die giving birth is like being born dying.” You’re always interested in the cyclical and circular. I wanted to ask, what was your intention with initially filming Ritual in 1980? It’s a very diaristic film, obviously.

AA: This was my second pregnancy. The first was my daughter, this was my son. I knew nothing about pregnancies when I was first pregnant; I just went into it without knowing anything. In the meantime, between the two pregnancies, I had heard a lot of stories. All these stories created a worry. While being pregnant was always a great pleasure and joy, giving birth is a different thing. And with the second pregnancy, I had a feeling that I might die while giving birth. I wanted to leave an image of this pregnant body. I didn’t have doubts that the child would live, because I trusted science, but I thought it probable that I would die. Both births happened with a C-section: the first out of necessity; the second was planned. The first time, when I woke up from the C-section, it was a pleasant thing. They had placed my daughter by me and I saw her eyes looking at me. But the second time, when I woke up from the anesthesia, I had this feeling of being buried.

Oh wow.

AA: You must understand that this film was shot the day before I entered the hospital to do the C-section. The whole feeling was a kind of saying goodbye, and of leaving an image of myself

I’m wondering if you had seen these two films prior to making this film: Stan Brakhage’s Window Water Baby Moving (1959) and then I’m wondering about Hollis Frampton’s Lemon (1969).

AA: No, I hadn’t seen either.

What was it like to have this film shot in 1980 and to revisit and finish it in 2008? What sort of things do you feel like would’ve only been in the film with decades of reflection? With decades removed from the initial images?

AA: When it was shot, I was still married to [my then-husband]. It was shot without my husband knowing. The people present at the shooting were: a cinematographer, a man; a friend, a woman; and my daughter, as a child. My daughter appears in some shots. It was a kind of hidden, secret shooting. It took place in my flat, but without the knowledge of my husband or the world. When this material was shot, I took it and hid it in the attic, which is not in the flat where the film was shot, but in the flat that I am in now, which was my parents’ flat then. The material was not printed, it was a 16mm negative. It was hidden there, disappearing from the world. A complete secret. No one knew about it except the people that were present during the shooting.

Anyways, I then divorced and after that came the film Topos. This feeling of nearly dying when giving birth was included in Topos. I also introduced some memories of my grandmother, as I explain in the documentary [Obsessive Hours at the Topos of Reality]. In the process of making this fictional film [Topos], there were many variations of the script, in which the feeling or the image of a woman that is at the edge of giving birth and dying appears and reappears. One interesting detail is that one of these versions was named “Passage,” but in Greek of course, “Pérasma.” So, I entered the world of fiction films and I never again played the game of the documentary. The only real documentary that I made was shooting this material, though later on I called it a performance.

In 2005, a big retrospective was organized for me at the Thessaloniki International Film Festival. For this retrospective, I was asked to search in my archives for materials. I put this film in my CV as a non-completed work, and this was when I started to think of this material again. In 2008, I took out the material from the attic; by that time I lived in the house that we’re currently in. I took the negatives to the laboratory and printed them. I digitized them and then we made it with my daughter Rea into a film. And, until the moment I heard Rea’s text, I imagined the film would be silent. What is also important in this text is how it is delivered and intonated. So, it’s not just the text.

Yeah, I’m curious to know about this performance of sound. Both of you are saying these words. How did you decide on how this text would be intonated, how it would be delivered, how it would be presented in the film?

RW: We did not decide it—these things we do not plan, we just do (laughter). We have a strange synchronization between us, the way that we create and work together. It was completely improvised—it’s all done by doing, not by planning in advance.

Part Four: Topos

Let’s talk about Topos. You mentioned earlier how it was shot in a factory and that you had this furniture brought in. I’m wondering if you could talk about location scouting. How did you choose this factory, and were you looking at other factories? Also, where did you get the furniture from?

AA: I looked for factories inside Attica—we didn’t have the money to go for a location outside the Attica area. While I was looking, I was very lucky because the big Athens gas factory, Gazi, had just closed. This was a very important factory in the center of Athens. It closed in 1984, the year before production began on Topos. It was serendipitous.

Entering this space, I had a unique experience. I felt as if the ground was like quicksand—I could not stand straight. I knelt and put my forehead to the ground. I felt it was a sacred place. I had a very strong memory of my childhood experiences in factories, and I had this feeling of sacredness that I never had in any temple. And in this space, I found the overalls of the factory workers. They were hanging, and they still smelled of sweat. There was this smell of human sweat mixed with the smell of the factory. That was a very strong sensation. It was as if there were human bodies hanging. When they ended work, the workers would hang their overalls up in a row close to the shower space. You can see this in the film.

Another element is that the space still had the machines inside. Nowadays, this factory has become gentrified and they have taken out the machines and made it into a cultural center, which is horrible in my opinion. At the time, the machines were there and they were covered with the dust of the factory. These were very strong images and feelings. There was a very strong feeling of Dante, of Inferno. There was even a space that the workers called “The Purgatory.” (laughter). I was inspired to introduce the film with a fragment from Dante.

If you remember, the film begins with a part from Canto I from Inferno. It’s where Dante meets Virgil and Virgil tells him, among other things, that “I will lead you to the place where people live their second death.” I used this fragment in the beginning of the film, and the first words heard in Topos are Dante’s words. It’s important that I chose the words to be heard in the original—in Italian. I liked the sound, and the important thing was the sound. It’s not that the meaning was not important, but it was firstly the sound and then secondly the meaning. Keep in mind that the Greek audience most probably wouldn’t understand Italian. There were no subtitles of the Italian, either. There are still no subtitles. The initial idea was that the Italian was heard like music. Obviously, people would recognize some words, like “Virgilio.” And obviously the reference to Dante would exist. But apart from that, if you knew, you knew. Otherwise, it was the music of the words.

That’s beautiful.

AA: So, there were three factories. The first was the gas factory, the big one. The second was a factory that made glue. They had some bath-shaped things where they had glue. If you remember, in the film, the women paint red a piece of cloth. This was done in the glue factory. The third factory was a beer factory. But there, I didn’t use the machinery or anything else. It was the fact that there were big, empty spaces. We didn’t really have studios in Greece at the time, and I needed space to construct my architectural constructions.

In that factory, the architect who mainly did the sets, Kostas Angelidakis, painted the entire floor with zig-zag patterns. This was inspired by [Giorgio] de Chirico’s The Mysterious Swimmer (holds up a book with a page featuring a monochrome reproduction). The feeling I had from this series of paintings was that a swimmer appeared from a concrete floor, and that the water was concrete, in a way. Kostas made these triangular molds and he painted the whole floor, this entire area, by hand. This, for some reason, brought to mind a memory with my little brother when we were in Patras. It rained and we couldn’t have a picnic outside, so we instead had this picnic inside. We put a blanket inside a room and we brought little things and ate inside. So, this indoor picnic reminds me for some reason of the patterns on the floor.

Wow, this is all beautiful. Was there anything you wanted to mention about the furniture and other props that were brought in?

AA: One of them was a bellows. There was also a green sofa I found in Monastiraki. Monastiraki is the old town in Athens where there are shops with old objects, antiquaries. Not expensive antiquaries—it’s kind of like flea markets. We found this very luxurious—it wasn’t that luxurious—green sofa (laughter). It looks very nice in the film. It has a huge contrast with the factory furnaces because it has curves and is completely different in style and geometry. A lot of the furniture we made ourselves. We made a pavilion, similar to an etching, an image that comes from the Middle Ages—there are the books of hours. And this was a part of the Medieval image of Topos. What also inspired me in Medieval illuminations was the speech of the characters and how they appeared on a kind of ribbon. This was interesting to me for the way that the speech is pronounced and exists as an image.

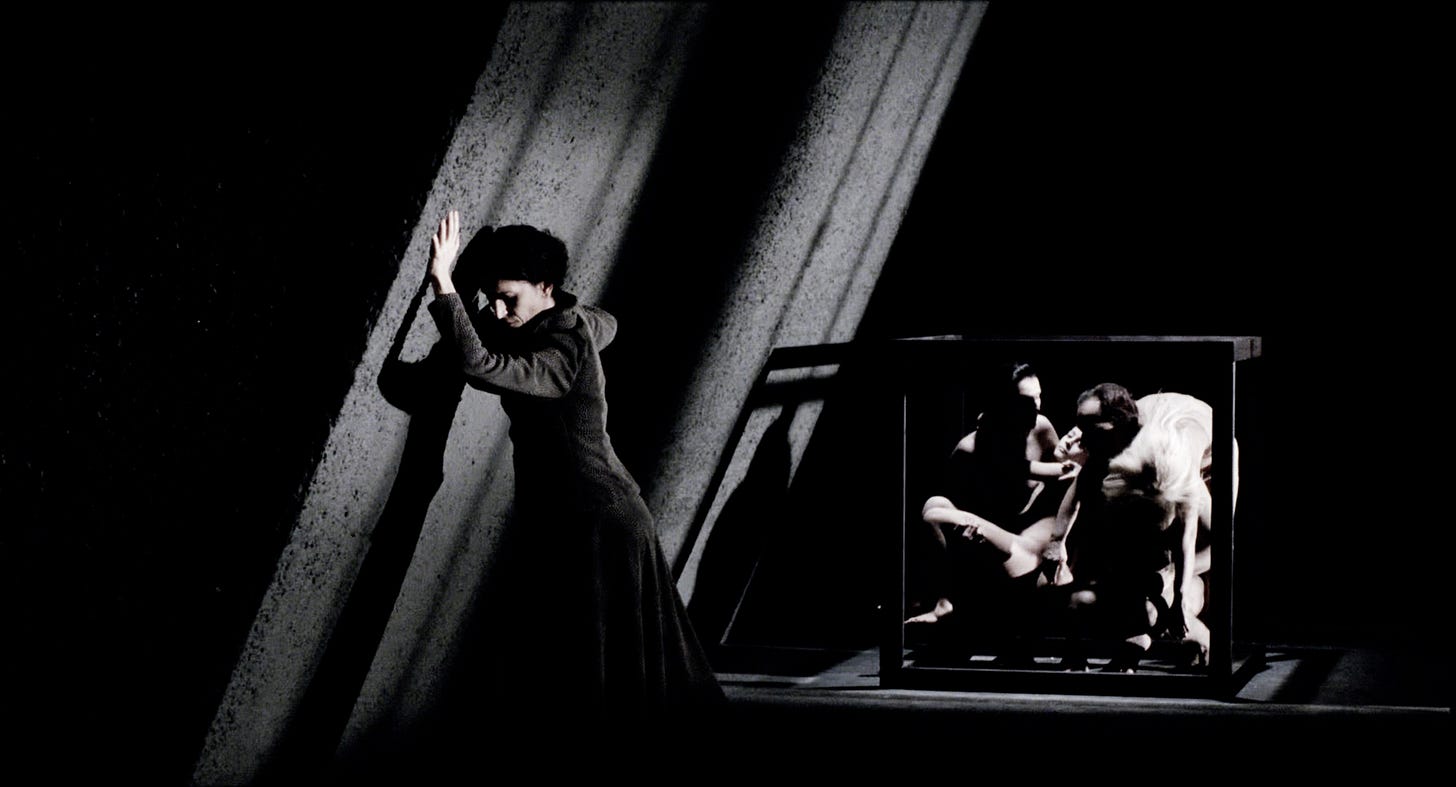

Back to the furniture, I made a lot of the designs myself. We constructed in situ what appeared like an architectural cut. In the film, you can see the garden and you can see inside the room in the same frame. We constructed this section that would cut the space. This came from the early Renaissance, as a lot of paintings from the early Renaissance are like this. The particular reference of this entire scene was The Dream of St. Ursula by [Vittore] Carpaccio. I have kept the image of the angel, who in my film is the lover, who stands outside of the room. It is also the woman inside. And if you remember, in the painting, under the saint’s pillow, there is a white ball that says “IN-FAN-NTIA”, which means “childhood”, and this has been much commented on by critics and theoreticians. This ball appears in Topos a lot. It is one of the elements that are incorporated in the universe of Topos. There is another moment in the film that is connected to the sequence with the lover outside and The Dream of St. Ursula. Towards the end of the film, we have the same costume that was worn by the lover, the angel costume, that is now worn by a woman. This is Martine Viard, who plays the Musician.

Right, yes.

AA: This is a man’s costume, but in the end, it is worn by a woman. What goes on with the ball? It’s very symbolic. The main character, who is played by Jany Gastaldi, we see her at different ages—both as a child and then as a woman. At the end of the film, she wears again, as a woman, the clothes she wore as a child. And the costume of the lover is worn now by the Musician. Jany’s character goes and gives the ball to the Musician; she does not give it to the lover or to the motherly figures. Instead of a lover or a mother, she chooses art. In Carpaccio’s painting, St. Ursula chooses to become a saint instead of marrying. In the same way, in the film, the character chooses to become an artist.

I did want to ask about Martine and composer Georges Aperghis. That’s actually how I found out about this film many years ago. I had heard their album, Récitations (1983), which Martine is also on. I’m curious how you found out about these artists and how you wanted to incorporate them into your work. What sort of conversations did you have with them?

AA: When I was in Paris with Claire Mitsotaki, with whom I wrote the script for Topos, we were preparing for the film and in our friendly circle was Victor Arditti, who is a Greek theatrical director. Through him, we came in the same environment with the French theatrical director Antoine Vitez. Through him, I eventually came into contact with Aperghis and with the actress Jany Gastaldi.

I had a meeting with Aperghis, it must’ve been at the end of 1983 or the beginning of ’84. I brought my scores, which obviously weren’t music scores but audiovisual scores. I showed him my scores and described the way that I worked and how I take images apart and reconstruct them. I spoke about St. Ursula and the first thing he said was, “We should start from silence.” He didn’t want to write new music for the film. Instead, he put me in touch with Martine Viard. We got along with her very well. Aperghis had dedicated to Martine the Récitations, and this dedication involved giving her the right to express them the way she wanted. And I had heard Récitations in advance, but on reel-to-reel tape.

So, me and Martine became close collaborators. She came back to Greece with me. I first used her as an actress before using her as an improvising singer. The shooting was done silently. We did not have sound recording done during the shooting. Topos, when it is silent, it doesn’t have background sound; because today, even “silence” in films is never really silent.

Right, so there was no room tone or anything in your film.

AA: In Topos, there is no such thing. When you have silence, it’s complete silence. This meant that at the time, you could hear the sound of the projector. And this became the sound of silence in Topos—it was part of the sound composition. Aperghis gave the right to Martine and me to use his music scores. In the film we use Récitation 7 and Récitation 12. We used that as a foundation. These were only used in the third part of the film. The rest of the improvisations were completely outside the score, but in the third part of the film the improvisations are based on Aperghis’ score. The process was like this: We projected the film in the space where we did the sound recording. We projected the film silently on the wall and while the film was playing, Martine improvised.

Wow, that’s awesome.

AA: And all the noises in the film are made by her voice. You don’t have objects making sounds, like doors opening, steps, everything. I would give directions and Martine would improvise with the moving image. It was a selective process in terms of which objects would have a sound and which objects wouldn’t. For example, there is a shot where you have two cradles rocking. They have a very strong cracking sound (imitates the sound). This sound is made by Martine, as every other sound is. You can probably hear a resonance from sounds in Récitations, but not necessarily from the 7th or the 12th. She had inspirations from these and rearranged them to match the images.

In the second part of the film, with the crying cloth that is part of the mourning, there is a part that reminds me of Récitation 14. In the third part of the film, there is a clearing of the throat and coughing. This is probably inspired by Récitation 8. So, you see, Martine was taking elements and using them to clothe the film. She makes all of the noises, and there is not a single sound that isn’t made by the human voice. It is important because this voice, Martine’s voice, is the voice of the film. The voice of the body of the film. The film itself—or rather herself—is the woman who gives birth and dies. In the same way that the factory is her body, Martine’s voice is her voice.

Yes, that to me was one of the most striking things about the film when I first saw it. There is this woman who gives birth and dies, and there is this notion of her being embodied in many different aspects, across time, and across different people. And then at the same time, Martine’s voice is embodying these different objects, these different people, these different moods. To me, the overarching message in both image and sound is this representation of women having infinite possibilities of representation and being. I’m curious if you could talk to me about just the significance to you of using a human female voice for representing all these different sounds? What was the thinking behind using a human female’s voice as opposed to having diegetic sound or a male voice?

AA: Before answering your question, a clarification. Martine is doing all the sounds of the objects. She does music, all the sounds, all the noises. All the objects are like a big body, as if the entire space is a big body. Now, the voices of the characters are again made by a woman’s voice, but it is a different woman. It is Annita Santorinaiou, who is an actress. Annita’s is also a single voice, a single female voice that passes through all the characters’ bodies. And what Annita did was to position her voice in different places, like in her chest, in order to create different colors of pitch. So, there are harsher, deeper, higher, different kinds of voices. Depending on the character, she would situate her voice in different positions and intonate different voices.

We have in the entire film this weaving of two women’s voices. And to be exact, there are some exceptions. There are some significant moments where other voices are heard. But the majority of the sound universe of the film is created by these two voices. Everything passes through the body—it is strange, familiar, dispersed, multiple. This is a body that may include many people unified as one, but the experience may be of a non-unified self. Most important of all is that everything begins with the body.

You mentioned this notion of silence in the film and how it is a complete silence, that it is not room tone or ambience. I’m curious, what was the reason for that?

AA: I really detested these small sounds that they put over silence. Silence, the beginning of silence, is the silence of the night sky during summer. It’s when you can see the stars. It is also the sound of the universe, and I had this feeling that cinema had the possibility of creating the sound of the universe.

There are different kinds of silences. There is the rich silence of contemplation, but there is also the silence of oppression. I spoke about that in my next film, The Hours: A Square Film (1995). I spoke of silence as a denial of speech, as a silencing of a child by their environment. And then this lack of speech, through art, can be transformed to a meaningful silence, a rich silence, a contemplative silence. A silence that may have a memory of time before birth. Is there anything else you wanted to ask about Topos before moving on to The Hours?

I’m curious about your fascination with filming tongues. This also appears in Idées Fixes. Do you mind speaking about that?

AA: As a child, I was very proud that I could roll my tongue (Angelidi sticks out her tongue, rolls it, and everyone laughs). And then, of course, I connected that with the prohibition of speech. In Idées Fixes, the razor comes against the tongue.

RW: What is initially an organ, becomes a sign of speech. And then comes the razor that cuts the speech. There is also a recollection of the image of the vagina that comes to the same position in the frame. There are multiple juxtapositions and a kind of layering around speech, gender, being prohibited to speak, and the bodily aspect of speech.

AA: The tongue is a piece of flesh, and this piece of flesh—this bodily thing—produces sounds which become language.

RW: Mind you, in Greek, “language” and “tongue” is the same word.

Ah, I didn’t know that.

RW: In English too you say “speak in tongues” and “mother tongue”, but in Greek, the word for “tongue” and for “language” is the same always, so their relationship is more immediate.

AA: I don't know if there is this meaning in the US, but in Greece, sticking out your tongue is a sort of teasing.

Yes, we have that as well.

AA: The expression in Greek is “I’m sticking my tongue out to you.” So, if this film, which itself is a body, is sticking its tongue out to you, it’s making fun of you. There is also this level of playfulness. In Topos, the tongue that appears is mine. So obviously, it’s the tongue of the author, of the filmmaker. And because the film is a big body, it is the tongue of the film! It is interesting because while we see the tongue, we hear a tongue sound (imitates wet tongue sounds) that is made by Martine of course, not me. And when you see the tongue, you think it’s the sound of the tongue, and it actually was the sound of a tongue, though not the one that is onscreen. And then in the next shot, the characters in the film (leans head back) say, “Ah, it’s raining.”

This becomes a strange comment on filmic construction and how you perceive it as the realistically diegetic sound of rain. You see, it is a constant game, a play about construction, and about what is fiction and what is reality.

RW: That image of the razor inside the mouth reappears in Thief or Reality (2001), which was done on purpose, of course. If you remember the shot, or rather the sequence around it in Thief or Reality, it is a man who keeps the razor in his mouth, very aggressively. And the woman comes, kisses him, and takes his razor in her mouth. So there, it is much clearer politically that she takes this dangerous and powerful speech. It is no longer the question of the cut being inflicted to you by the razor, but having the razor as your own speech; there is a difference between being the subject of the razor and the object of cutting. It’s an inter-filmic game, let’s say.

Part Five: The Hours and Thief or Reality

Shall we talk about The Hours?

AA: The most important thing about the sound in The Hours is the choice of the piece of music that is heard close to the scene of the rape. In The Hours, it appears rather elliptically, the childhood rape. The audience didn’t understand that it was an autobiographical reference, at the time. The music is a piece by [Henry] Purcell, Music for a While. When I first heard it, it was sung by Maria Georgarakou, who is a mezzo-soprano, a blind mezzo-soprano. I was greatly moved by the exquisite sound, her voice, and also the words. She sings and plays the character that sings the song in The Hours. She also sings in the fourth film, Thief or Reality.

I had this notion that music, in a single moment, can save you. And there is the tragic irony of the fact that, for me, music didn’t save me—it was the music teacher who destroyed me. So, it is at this significant moment in the film that I put this song. And also exactly after the event, this elliptically presented event, the musical piece is fragmented. It’s cut into little pieces. It’s no longer harmonical, it becomes distorted.

The film is called The Hours: A Square Film because I have a feeling that hours are circular and the “square” contradicts them; but I feel like they can coexist. On one hand, it is about the flowing of time, of something that has curves; and, on the other, there is this strict, austere structure that comes, the mechanism of dreams. It is the flow and the strict structure together.

Because this film is autobiographical in some regard, I’m curious what it was able to do for you. Like, were you able to process or learn specific things as a result of making it? Or was it more so that you had already learned and processed things and made this film as a result?

AA: The film is the final product of a long, unsuccessful psychoanalysis. In this film, the events are as if they’re covered in a membrane, a… film (laughter). They are little cocoons of events and my effort with this film was to break the membrane and get inside these events. Indeed, the film helped me. When it was finished, I felt redeemed. But this is always the case with films: in the end, you understand yourself better. This film helped me to go on, to leave this behind and proceed to a different phase in my life. A new phase, a new collaboration: the collaboration with my daughter. It was around that time that we started having a creative collaboration.

Still, I want to do another film about the same material. For a very long time now, I wanted to make a film, and I actually have given it a title: Hours After or After Hours. I want to revisit this material, but I don’t know what I will do with it. And now I want to speak about Thief or Reality, if you don’t have any other questions about The Hours.

I did want to ask about you wanting to revisit this film. Is this because you feel like things are still not fully explored, or are you simply interested in seeing what happens upon revisiting?

AA: I’ve done two unsuccessful psychoanalyses and I’m in my third now. I believe that I have gone much deeper into this material and that I have made new connections with it. In the meantime, I’ve also had the experience of teaching. So, this all makes me very much a different person. And to that, you can add the recent experiences I have had that I explained in the documentary.

We can start talking about Thief or Reality now.

AA: I want very much to start talking about the differences between the three parts of Thief or Reality. My daughter and I wrote the script together. The different parts are different conceptually but also aesthetically, and I want to present these differences by talking about sound, considering that you seem interested in that.

Yes.

AA: So, I will start by reminding you that the three parts are: fate, randomness, and free will. Though in the film, we gave them the names “The Net,” “Dice,” and “Will.” “The Net” is fate, “Dice” is randomness, and “Will” is free will. Let’s start with the first part. This was silent. There were no spoken words. And the reference was silent films. There is one word heard though, and it is tetelestai. This is a word from the Bible when Christ says that everything is finished. Literally, it means “it is finished.” And obviously, it strongly resonates with people because of its religious context. The silence in the first part is not a silence—it is a buzz, a musical buzz. It’s also electronic, and this is the first film of mine where the sound is electronic. There’s a Greek expression that is very poetic. It’s “to hold on feathers.” The sound in the first part of the film is as if it holds all the moving characters, the actors. It’s as if they don’t really touch the ground. It’s that same feeling—they are held by the sound.

The dramaturgical structure of the film is a triple repetition. The three parts are supposed to be the same day as perceived by different people. Although they are significantly different, even to what is happening, the structure is the same. Every part ends with a kind of procession, let’s say. The procession of the first part is this Medieval self-flagellation. It is this notion of deep and distorted religious faith, which is obviously inspired by my nanny (laughter). The distorted religiousness in my work is always from my nanny. The second procession is the procession of Good Friday. Again, it’s a religious procession, although it has a different significance in the film. The third procession is the procession of the actors. It is inspired by the [Francisco] Goya painting, where there is a doll taken up and down…

Is it The Straw Manikin?

AA: Yes, El pelele, that’s it. I was also more broadly inspired by Goya’s Los caprichos throughout my work. You see, the imagery returns again and again. Going back to sound, the second part has sound: speech and other sounds. The games with speech are very meaningful in this film, as a second collaborator appears who has a different relationship with speech [implying Walldén, who laughs]. In the third part, you hear not only speech, but also the thoughts of people. There is a completely different sound universe when you start hearing this continuum of thoughts.

What I described were elements of sound that were planned in advance that were in relation to the dramaturgy. Moreover, apart from this kind of stuff, again as in previous films, the sounds tend to be meaningful and taken away from naturality. They do not function as illusion of reality, as diegetic sound. I did a lot of work on that with the musician of this film, who was [Thodoris] Abazis. We worked together on single sounds and how they function. One of the most impressive cases of sound is in a shot where one of the main characters falls on the table and throws a lot of objects made from glass. The sound of the glass crashing out of the frame, has a great temporal distance from the point when its fall started inside the frame. This creates a chaotic space, a huge distance. It is one of the most impressive applications of this game, of creating space through sound. And everyone notices that, even the less attentive audience members, because it is unexpected.

What’s the intent for you in creating space? What are you hoping the audience members gain from this space that is created as a result of this disjunction between sound and image?

AA: This technique, as well as others, create a strangeness of space. The concept that we’re trying to arrive at is the uncanny. What is important here is that I always used this combination of the uncanny and defamiliarization. This is not, however, a theorized decision, but rather where I was led by my feelings—I felt that things should be this way. I tried to be as faithful as I could be to myself, and I had this conviction that if I said the most secret thing, it would be universal. It would address humanity. This is how you address the world: by being as faithful as you can to yourself. I found out later, when I described my method both structurally and aesthetically, that there is the connection of the Freudian uncanny with Formalist defamiliarization. I started theorizing this after my films, when I started teaching at the university.

You said the first part of the film was inspired by silent films. That comes through partly in the movement of the characters, which at times becomes very dramatized and becomes a dance. What silent films and filmmakers were you inspired by? And also, can you speak about this element of dance and choreography and how that plays a role in how the actors move in the film?

AA: The references for the first part of Thief or Reality are particularly Vampyr (1932) by [Carl Theodor] Dreyer and Nosferatu (1922) by [F.W.] Murnau. I have been inspired by Dreyer and Murnau more broadly. Faust (1926) has inspired me for different reasons; I had a revelation when studying this film, of how cinema works. Also, Dreyer is very meaningful to me. And particularly, Dies Irae (1943), which is why my first film is Idées Fixes / Dies Irae. [Editor’s Note: Dies Irae is the Latin translation for Day of Wrath]. I consider him to be a proto-feminist.

Regarding the second question, the body has a rhythm. I won’t answer about the movements in this particular film, but about the movement in my films in general. The movement of the body develops through the body in the same way that speech develops through the body. I didn’t have dancing or cinema or theater as a reference for these movements. It was about following the body. In Topos, for example, the body would move like birds of prey, like snakes, like paintings by Balthus—the stretching of the bodies of women and girls in his paintings. So yes, of course it is perceived as choreography, but this was not planned. It was something that came from inside the body.

That reminds me of what you said about the improvisation about the speech for both of you, when making the film, Ritual.

AA: This is the way I teach the actors.

RW: Being her daughter, I have been taught that too. She teaches her actresses and actors about how the voice comes out of the body. She does a lot of rehearsals before her films, where she teaches about the body and about speech articulations.

AA: (Angelidi holds up a book). This is the inspiration for the Sculptress in the film. It is a Medieval illumination. In the film, she sculpts tombs, but the feeling I had when looking at the illumination was that she was making a sculpture of herself. Each of these the main three characters have a moment of delirium. So, the delirium of the Scientist, the mother, if you remember, is in the water. The delirium of the Sculptress, which is a kind of delirium she has on her work, was inspired by the hysteric women of [Jean-Martin] Charcot. I told the actress to move like these arches of hysteria. (holds up the cover of Les Démoniaques dans l’art : Charcot & Richer and opens to a page in the book showing illustrations). So, Charcot took photographs of the hysterics and then compared them, his sketches and photographs, with the history of art. This was the inspiration for the Sculptress’ movements when she’s in a crisis.

You said earlier that with each film, you learn something. What did you feel like you learned with Thief or Reality?

AA: With Thief or Reality, it is easy to give the obvious answer, as it is worded inside the film. “Because we will die, we can live.” In a way, mortality makes us all equals. It’s this idea of solidarity. And of course, there is the motto of the film, which we both feel very strongly about. “What I spent, I had. What I saved, I lost. What I gave, I have.” So basically, it is a motto that is said by a dead man. Whatever you have given to others is what you have in the end.

On that topic, who in your life do you want to mention right now that has given so much to you?

AA: My daughter (the two lovingly hug).

What do you feel like she has given to you?

AA: She’s with me, by me. She understood what I said when others didn’t. I have been through long periods where nobody understood me in my life, with my work, anything.

That’s beautiful, thank you for sharing that. Is there anything else you would like to say about Thief or Reality?

AA: It is a questioning on what reality is. Reality is a concept that was first brought up by my daughter. This was something that I didn’t always understand. In the past, my feeling of reality was a flesh-eating mechanism. And throughout my life, in order to do art, I had to open up space through the very thick air of reality. I never questioned the fact that I was an artist. If I had not been an artist, I would be a madwoman. But the fact that I managed, also, to have two children whom I love and who love me… this is a reality I never imagined.

Antoinetta Angelidi is the recipient of Prismatic Ground’s Ground Glass Award. A retrospective of her films is playing during the festival. Tickets and further information can be found here.

Thank you for reading the 43rd issue of Film Show. Live a reality that you’ve never imagined.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.

What an excellent, illuminating interview with a clearly stunning artist. If only I could see some of her films.