Film Show 040: Angela Schanelec

An interview with the German filmmaker about performance, knowing when to show an actor's face, and her new film 'Music'

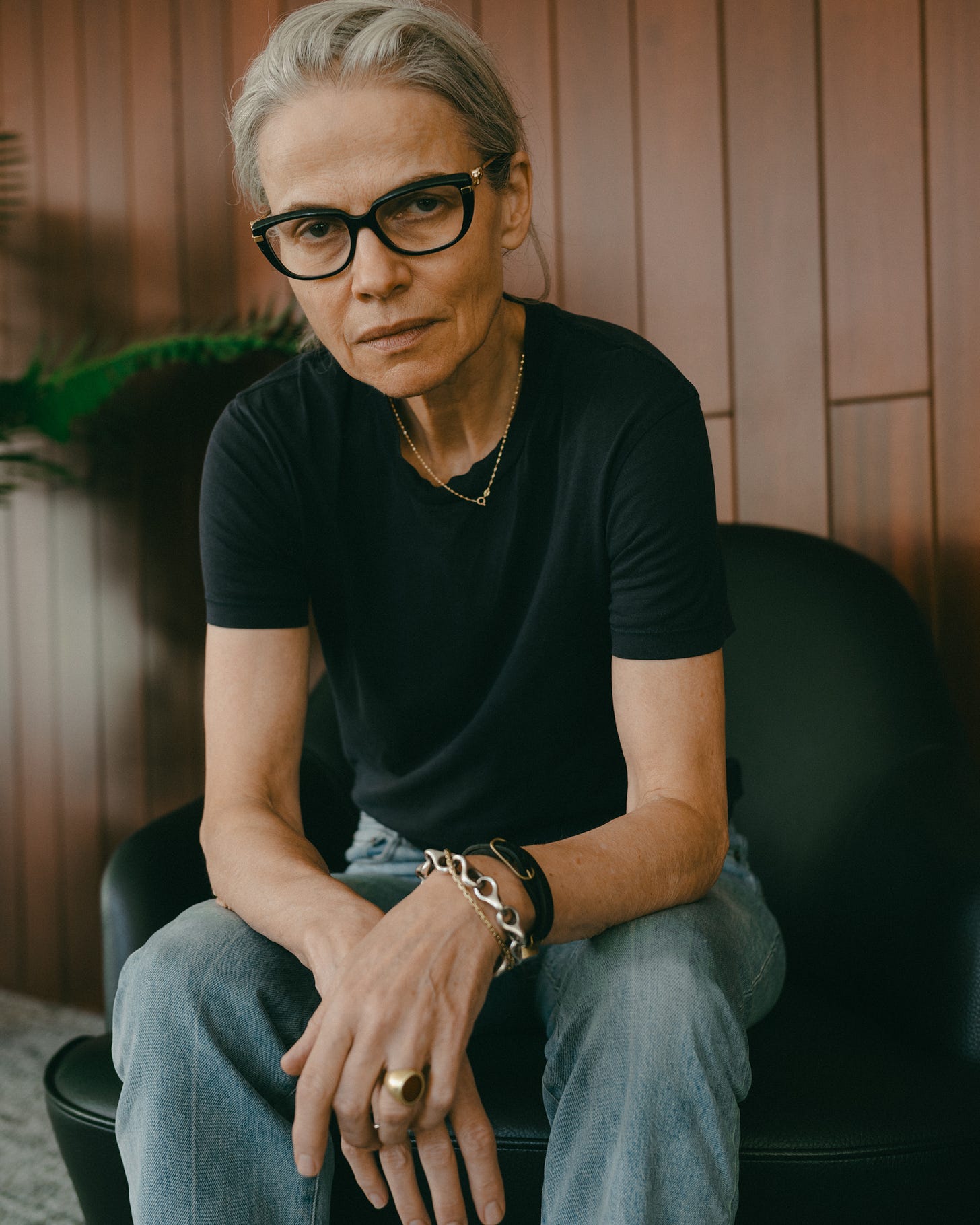

Angela Schanelec

Angela Schanelec (b. 1962) is a filmmaker born in Aalen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Since the early ’90s, she has written, directed, and edited critically acclaimed feature films such as Places in Cities (1998), Passing Summer (2001), Marseille (2004), The Dreamed Path (2016), and I Was at Home, But… (2019). Her latest film, Music (2023), had its premiere on February 21st, 2023, as part of the 73rd Berlin International Film Festival, where it won the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay.

Music is a work of subtraction and permutation—striking figural constructions (prison guards in a choreographic game of ping pong, faces and bodies immobilized by tragedy) and gestures of reduction (narrative ellipses, strenuous conversation). Drawing on the myth of Oedipus, Schanelec approaches her characters as simultaneously singular and archetypal: A myth is historical and local (i.e. Ancient Greece), but endures across space and time due to its moral character and the tropes and types it produces (the Oedipal, the Promethean, etc.). Music is not merely a feature of Schanelec’s film, or one of its characters’ talents, but also a perplexing impulse or desire—a veritable riddle. Where does music come from? In Music, senses and gifts are lost and gained (sight and song), structuring a film whose emblem—Oedipus’ bruised, swollen feet—crystallizes Schanelec’s decades-long devotion to revealing the emotional and societal effects of injury.

Following the U.S. premiere of Music at the 61st New York Film Festival, Hicham Awad sat down with the filmmaker at Lincoln Center on October 5th, 2023 to talk about speech and communication, images of faces, and filming music.

Hicham Awad: Music—singing, especially—plays an important role in your new film, Music. How did this come about? How does music figure in relation to myth, in this film?

Angela Schanelec: When I was thinking about the myth and why I wanted to start writing this narrative of Oedipus, it came to the point where Oedipus [“Jon,” in the film] realized what he did [killing Laius, his father, or “Lucien” in the film] and asks himself, “What have I done?” It was always clear to me that he would not blind himself. I just could not imagine that. I could not imagine wanting to see it. I also couldn’t imagine telling this without showing it. Then I thought that he might cry, and that singing comes out of this cry or scream he lets out. His voice, with time—it’s a long, loud cry—transforms into music. This is where the music comes from. When I started writing the scene, I thought, okay, this could now be a chance to really work with music—that this scream might tell us where music comes from. How is it possible that we can sing? Singing comes out of this scream.

That’s beautiful. We also don’t see his face when he screams, as his friend embraces him.

Yes. If I imagine someone is emitting this strong cry, then this has an impact on the distance, because I wish to keep a distance from him. I do not want to look at him from a close distance, while he’s in pain. This also has an impact on light. Is it better to set this scene at dawn so that there is almost no light? It's all connected.

This makes me think of something that found so striking in the film, these two scenes of death scenes and how you film them. The first is the scene we just talked about, in Greece. In the first one, there is a sequence of images that shows us the effects the killing has on the group. We see the stunned faces of the men—before we see the deceased. In the second scene, in Germany, you film this car accident with this lateral tracking shot.

I mean, first of all, I never feel the need to show something. In the first scene, after he pushes him, you only see his shoulder and his neck. He’s breathing heavily and time almost stands still. But time cannot stand still. So, I decided not to move the camera, but to keep it still. A situation like this killing will change your life. And maybe you can convey this through an awareness of time in that moment, how deeply you feel time, the time that almost does not continue. This was what I thought I could film. And then I’m very free to decide if and when I want to show the character’s face. This is something I can imagine, already when I’m writing the script. Theoretically, I can change the scene in the editing, but in that case—in most cases, actually—it was very specific and precise from the start. The second scene, towards the end of the film, it’s very different. The death is the result of a car accident in Postdamer Platz in Berlin. It’s not intentional.

The different approach to filming has to do with the person who is looking at the accident, who is not the person who did it. I move with this person; I move with the feet because I didn’t want it to show the face, at that moment. The face was not interesting to me. When we see the woman crying, a few seconds later, after she sees the body, that is a different moment. She had some time to understand what happened, and the narrative shifts.

It’s no longer the moment of the death, but another temporality.

Yes.

Since you mentioned that movement on the feet, I was looking back at some of your previous films, such as The Dream Path (2016) and I Was at Home, But… (2019). There are recurring images of feet in your films. In Music, there are all these beautiful shots of Oedipus’ bruised feet, from infancy to adulthood. Feet are further away from the face than hands are. They are expressive in different ways, too. There is also this relationship with the ground and the earth.

Yes. There are a lot of aspects of that. One is that the hand and the feet cannot lie. When I work with an actor, he would maybe try to read the situation and think about what he would express with his face. If I show his hands or his feet, it is more like an animal. We see just a part of the body. That has been difficult for some actors because they feel reduced—as if I am cutting them. In a way, you can describe it like that, but the images of a hand or hands, for me, can tell what I want to say. If you see the face, then a hand or a whole figure, you can see that the hands are important. If you don’t see that, you will always be looking at the face.

In your work, faces have different kinds and degrees of expressivity and lack of expressivity. In Music, you linger over the faces of figures who appear only briefly in the film, like the bodyguards or the prisoners. As a viewer, you get this feeling that they come from somewhere, that they have experienced something, even though we don’t know what it is.

Yeah… yeah (laughs). These figures who are watching something without moving… they cannot move because of what they see. It makes them stop. And in that moment when they are stopped, you can see a lot. Yeah, you can see a lot. You see all the lines, you see everything.

Yes. This duration of the face, not just its image.

Yes, it’s very interesting. Yes, the breath continues, and the mouth doesn’t move anymore. It’s open and does not move, or it’s closed, and when you see it, you become aware of the person.

You once said that when we think of a person, we always think of a person in a space—that we don’t imagine a person’s face in a vacuum. There’s this tension in Music because there’s something universal or abstract about mythology. We no longer refer explicitly to the time and place of the Greeks. The moral character or lesson of a myth can be thought of as cross-geographical and cross-historical. So there is this lack of place, in a way, when we think of something as Oedipal. In film, however, you must place the myth again, somewhere, to make it local. When you started working on this film, what was the first image that came to mind? How did you first see Oedipus as a living, contemporary figure?

It was always clear to me that I had to begin with his birth, and that it should take place in Greece. It was also clear that it should be in the mountains. Finding this landscape was very important to understand where I would or could go. We started looking for this landscape before the film was financed, even. We to travel to Greece at different times of the year to understand what landscape would be right. And this cannot be invented, this can only be found. You have an idea, for sure, but it’s not only about fulfilling an idea, because that is not possible. You must travel and look for something, for this possibility. Afterward, you start relating the locations to each other. Then it comes together.

What you said also made me think of the films of Ingmar Bergman, like The Silence (1963). He films faces in an abstraction, without space. I mean, his films are connected to theater. So, his relationship to acting and to the possibilities of what a face can express are very, very different than mine. For him, it is possible to see a face and the expression of a face in front of a white background. This kind of image does not figure in the way I think about film. Space is very important to me. Recently, I’ve been thinking about including spaces without people and what that means for the rhythm of a film about characters. But then to have a space without people, it’s in Music as well.

The opening shot of the mountain. As with I Was at Home, But…, the first few minutes of Music has no dialogue.

There is not a lot of speech. In the first version of the script, there was a bit more, but later I thought it was unnecessary. This is very connected to the narrative of this film because there are moments when it’s really about talking and communication, or about trying to communicate.

I think of your films as having, and working on, this relation to Europe. The Dreamed Path (2016) opens in Greece, on the eve of the country’s integration into the European Union in the early 1980s. The second part of the film takes place in Germany. This is the case in Music as well.

For The Dreamed Path, it was very personal. You have these two people who are not Greek but are in Greece. They are young. They’re making music. It’s very, very simple. It’s connected to my youth. The first long journey I made, when I was 18 or 19, was to Greece. This was in the late ’70s, the beginning of the ’80s, when almost everyone in Europe was traveling to Greece (laughs). The second part in The Dreamed Path takes place in Germany because I’m German. The second part of Music should have been shot in the UK, but I had to change it to Germany for funding reasons. What’s definitely true, though, now that I’ve been in New York for a couple of days, is that I’m very aware that I am very European. The life here is not clear for me. I just do not know it, and I would not be able to move here. I can maybe move to France, but here I’m asking myself so many things about the people around me when I’m looking around. I just don’t know it.

I was reading this interview with Douglas Sirk, where he is asked about his relation to melodrama. He goes on to make a distinction between what he calls the “folklore of American drama” and the meaning of the word “melodrama”: music + drama—a meaning, which he argues, has been lost. In addition to calling his earlier, German films melodramas, he calls the ending of Richard III melodramatic, but also Aeschylus’ Oresteia a melodrama. I don’t know if you would call Music a melodrama, but there’s a way it wrestles with this synthesis or coexistence of music and drama. Music is kind of an enigmatic object, in this film.

Somehow, even if I can see and explain to myself the structure of music, of harmony, of how a sound is created with an instrument, I still ask myself, “What can be done with this?” For example, I was not at all familiar with Wagner. But for the first time, a year ago, I listened closely to the Ring cycle, and I understood what you are now talking about. What I’m saying is clear. It’s nothing new but, still, the question of what you do with music when you have the opportunity, is an immense question. I think this is one of the reasons why I gave the film its title. Music is not merely a part of the film; it is a way of working—of working with music. For example, I find it very difficult to find a way to film the moments when someone is singing. Now in the film, it’s very simple, but I do not know if this is the solution. Maybe. I mean, now in this film, I did it like that, but it’s somehow not solved for me (laughs). I do not know how to explain it. In the scene in the prison, it was easier. But then, in the concert, it was not clear to me. I have a way of finding the distance, the angle, and the framing. I am very used to determining this. But with the concert, I was somehow lost. Actually, this is the first time I talk about this.

I found the scenes in the recording studio and the concert space very moving. They’re very different too.

But I found it strange how reduced I felt in finding these frames. It was difficult.

This makes me think of the reduction of space that you identified in Bergman’s films. What’s particular about studio recordings is that most of the time there’s a very costly and elaborate effort to erase or flatten space.

Yes, this is true. Concerning the stage, I have filmed stages and actors on stages before, their faces and movements. But filming music on stage, filming someone singing, was unclear.

The difficulty lies in filming music itself, not the stage.

It’s completely difficult, definitely different. It’s so strange because there are thousands of images of people singing on stage, but I think they’re not really satisfying. I don’t know what is. What do you tell through the way one sings? Sure, you can say, “Okay, I love to see someone singing and the way they’re doing it.” But what appears often adds nothing.

Maybe that’s why we latch onto the face, as an answer or anchor. But that’s limiting, too.

I also find it very annoying when I see the facial expression and hands of someone playing piano. I’m very disturbed by it. It’s a question of performing, I think, and what I do with actors in my film is not about performance. There it is.

Angela Schanelec’s Music is distributed in the US by Cinema Guild. A theatrical release is planned for to arrive within the next few months.

Thank you for reading the 40th issue of Film Show. There it is.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.