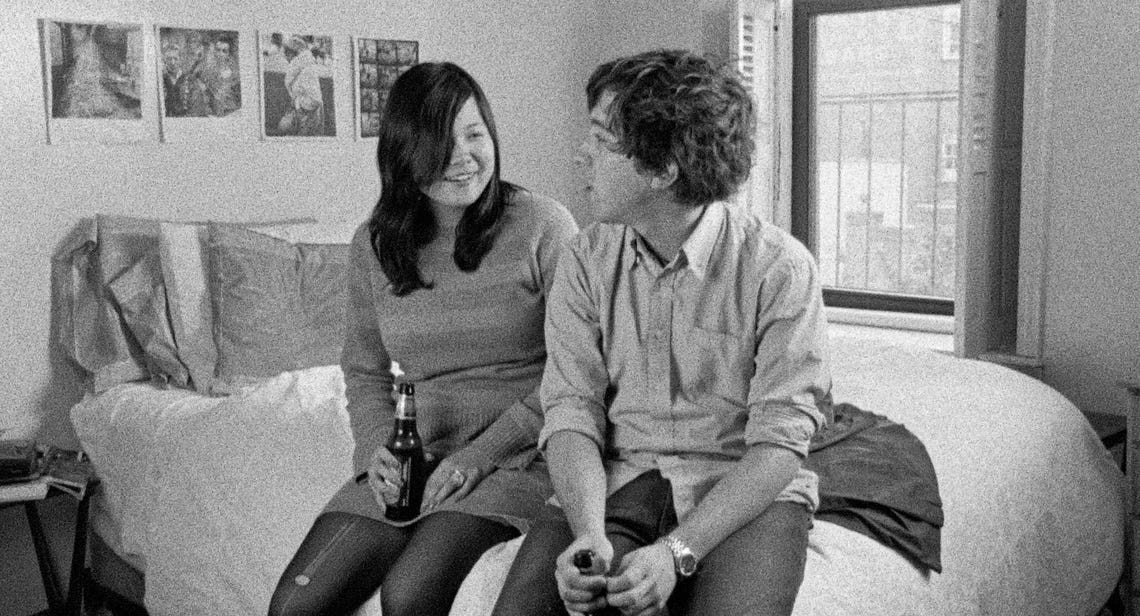

Film Show 032: Andrew Bujalski

An interview with American filmmaker Andrew Bujalski about his filmography, including his new film 'There There' and the 10th anniversary of 'Computer Chess'

Andrew Bujalski

Andrew Bujalski is a Massachusetts-born, Austin-based filmmaker largely credited for starting the so-called mumblecore movement with his debut feature Funny Ha Ha (2002). His early works were viewed as part of an era of low-budget, American indie films heavy on dialogue and centered around life as a young adult. In 2013 he released his fourth feature film Computer Chess, an idiosyncratic comedy about chess software programmers that was shot on Sony AVC-3260 video cameras. The film celebrates its 10th anniversary this year, with screenings taking place via Kino Lorber; notably, it is the centerpiece for a a series at New York’s Metrograph titled “The Color of Black and White,” which is showcasing films from the early 2010s that are in black and white.

Bujalski’s newest film is titled There There (2022) and serves as one of the best films made during the COVID lockdown that also reflect its prickly circumstances: the film, shot on iPhones, was made with microcrews of two to four people, and and with no two actors ever appearing in the same room at the same time. Shot in various countries, There There is another showcase of Bujalski’s knack for dialogue-driven intimacy, and is a reflection of a lifelong commitment to constantly challenging himself. Joshua Minsoo Kim and Bujalski talked via Zoom on August 1st, 2023 to discuss growing up around Boston, his various films, the differences between working for Disney and on his own independent projects, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: How’s your day been so far?

Andrew Bujalski: Pleasant enough, little to report here. How about there?

I just came back from Philly. I’m a high school science teacher for my main gig and we had a conference, and now I’m back in Chicago.

Every educator I know seems to be struggling in the past three years, at least.

Yeah, when COVID started that was a whole thing. It felt like each year from 2020 onward was a completely new year, so it was tough. It was fun seeing your new film, There There (2022), because there’s a scene with the messy parent-teacher conference. And there’s the scene afterwards with the lawyer and they’re talking about these videos that kids are uploading. It reminded me of the initial rumblings about TikTok. I remember seeing videos and posts where people were saying things like, “Watch out, a lot of pedophiles are perusing this app.” Your child is a teenager now, right? Have your experiences with raising children in this new era impacted the way you approached anything in this film at all?

Yeah I’ve got a teenager and a younger one as well. You know, I have some awareness of what’s going on, but I’m fairly luddite—I tend to be the last to adopt new things. I think the only prescient decision I made in the 21st century is to not be on social media. I don’t have Facebook, Twitter, any of that, but I do have kids, and as far as I know they’re off social media for now. But it’s in the air—I talk with other parents and we’re acutely aware of worst case scenarios, certainly. That doesn’t mean we’re always wise about how to defend against them or prevent them. I think that stuff in the film came from my own parental paranoia and headline skimming rather than any specific experiences. And certainly as far as that parent-teacher conference, I’ve never been on either side of that, but I’ve certainly sat in some rooms and let my imagination wander (laughter).

Are you happy you’ve never been on social media?

I’ve never regretted it. That’s not to say I never looked at that stuff. Like when my movies come out, I may search Twitter to see what people are saying, but now that Elon Musk has driven it into the ground, there’s a part of me that’s like, great, now I can just not search it anymore. It’s not that I’m completely cut off from these things, but I don’t have an account and I’m not on there every day, and that’s fine. I don’t feel like I’ve missed much.

I wanted to ask about your childhood. I knew you grew up in the suburbs of Massachusetts. If you were to describe to me what it was like to grow up in that space, what comes to mind? Anything you think fondly of?

I think fondly of most of it. My parents were divorced and we moved around a fair bit. I wasn’t like a military kid or anything but I did have that experience of being the new kid. I’m very lucky to have some friends that I go back to second grade with, but all those people go back to kindergarten with others, so I still kind of feel like the new guy there. I look back and I think broadly about what it is to raise kids in what used to be a fairly secure, middle-class suburban environment. You’re protecting your kids and you’re offering them some kind of promise of stability, and that’s a nice way to grow up. Then you get older and you learn more about what you were being protected from, and I’m sure I’m shaped by that. Though I’m sure I would’ve been a cautious person no matter where I’d been raised. But this was the suburbs of Boston, so we had access to culture and a lot of the people living in these suburbs are smart and interesting. I met a number of people who I’m still friends with today and that’s amazing.

Did you go to Boston often?

By the time I was my son’s age, like when I’m hitting junior high, we were taking the T into town into Harvard Square to go to the cool record stores, comic book stores, and movie theaters. It was a treat to have access to that.

Were there any local figures at these stores or theaters who were instrumental in shaping you into a person who was hugely invested in the arts?

Good question. I don’t know if I was aware of any influential figures, but as a kid I was just living my life in movie theaters. And that goes back to when I was five years old—I don’t remember a time before I was movie-obsessed. Sometimes people say, “It’s great you always knew what you wanted to do,” and it is great, but it’s quite a limitation to have never considered anything else (laughter). In a way, you’re a science teacher—that’s fantastic. That means you know about two different things, and that’s one more than I know about (laughter). I admire and envy that—people who’ve had broader lives. But yeah, so much of my life’s education, for better or worse, was sitting in movie theaters. In Boston we had the big multiplexes in the suburbs. We had the West Newton Cinema and they would have some European or arty stuff. And then as I got older and was riding the subway, I’d go to the Brattle Theatre and the Harvard Film Archive and the Coolidge Corner Theatre and these were fantastic places to get an education.

Was going to these theaters a largely solitary event? Or did you go with friends and family often?

Certainly the older I got the more solitary it got (laughter). It’s because I could go by myself more, but as a kid I’m asking my parents to drag me out there and I’m going out with friends. Eventually I’m single-minded enough to go on my own trips.

Were your parents huge into movies?

We had a Betamax and then a VHS, so I spent a lot of time at the video store as well. Now that I have kids, I look back and it’s kind of amazing how permissive my parents were. I don’t know if that’s purely generational, and I’ve had this conversation with a lot of parents my age, but I can’t believe what our parents let us watch. Me wearing out my tape of Conan the Barbarian (1982) at the age of six… I don’t know if that’s the right movie for a six year old, but I loved it (laughter).

My parents weren’t movie buffs but they were extremely supportive and they wanted to encourage this interest in me, and they were patient enough. And seeing a movie… I guess it’s an easy enough thing to do with a kid (laughter). They suffered through lots of movies with me.

Are there any specific films you saw that made you realize that you should get into filmmaking?

I never made the decision, I just slipped into it. It was just an obsession. There wasn’t a turning point where I was like, oh this is a career; it was just what I was breathing for so many years.

Something you mentioned is that your parents were divorced and that you were moving around a lot. Was this just different places in Massachusetts or did you cross state lines?

We lived in Massachusetts until I was two, then Northern Virginia until I was six, and then back to Massachusetts, and then there was a year in Florida in high school. There were work things and my mom got remarried, so there were always reasons for my parents to be moving. When I got married, my wife had this remarkable continuity in her family. They had just sold the house they had lived in for 50 years, so it was kind of amazing to experience that—to see someone who could go back to their childhood home. For me, my childhood home from five childhood homes ago (chuckles) is gone.

I know you went to Harvard for the film program and worked with Chantal Akerman. Were there any prevailing lessons or ideas that she wanted you or her students to latch onto?

I had her as a thesis advisor, not as a classroom teacher, so I learned an incredible amount from her but it was certainly not technical things. It had more to do with what it meant for a kid from the American suburbs to encounter someone who is the most committed artist I had ever met. She gave everything to her work, and that’s not to say that her work was the sum of who she was—she was a deep and complicated person, and she was also very funny. And that might just be my own filter but that’s always what I either took from her or projected onto her, that to be as serious as she was, you have to be funny. And to be funny, you have to be serious. These things are joined in my mind.

Is there anything she said or did that was particularly funny?

She had a comical affect. I’ve seen her quoted in interviews that she walked like Charlie Chaplin, which is true. I have a memory of her sitting in a hallway and I think she had been playing with a friend’s daughter who put nail polish on her fingernails. Chantal never wore nail polish so she was trying to figure out how to get it off. She had gone to CVS and got some nail polish remover and she was just sticking her fingers directly into the bottle and I was like, “I’m a 20-year-old dude who knows nothing about makeup but I’m pretty sure that’s wrong.” (laughter). There was just a lot about her that was hilarious.

You noted that she’s a serious artist. Is that something you aspire to be—a serious artist?

I would like to mean what I say. I would like to not half-ass it. I aspire to make a real commitment, otherwise it’s not worth doing. It’s a lot of work, and I’m not a workaholic (laughter). I’d rather do something easy and get a paycheck, but that’s not the life I’ve chosen. I’ve chosen to do something weird and difficult, and I make it difficult for myself. I torment myself with these things, and there’s no point in doing that if I don’t mean it.

I love this idea of you making it difficult for yourself.

Always.

Is that out of a desire to challenge yourself?

This is a whole therapy session (laughter). Why do I torment myself? In part I guess it comes from a lifetime of being a movie fan. I think the highest aspiration I have is to give to somebody else what my favorite movies—the best movies, the best art—have given me. These are the things that make your life bigger and truer. I don’t know if I’ve ever succeeded at that but that’s what I’m pointing towards. And that’s not something you come by easily—you don’t get there by just giving the market what it wants. The market is very strong and assertive and it will get what it wants, and I don’t know that it needs me to give to it. A lot of people serve the market, so you go another direction and it’s painful and difficult and it may not produce the effect you want, but it’s the thing I keep telling myself I need to do, at least until the day I wake up and say I’m done. But I’m not quite there yet.

I want to ask, then, about the Lady and the Tramp (2019) live-action remake. You were a co-writer for that. What was it like being in this entirely different role, in this different system?

I’ve been lucky over the years to occasionally have these things fall into my lap. Lady and the Tramp is the only Hollywood gig I ever had that went to fruition—I have other things that never got made that I was happy to get paid for and work on. It’s a different mindset. What I have the most trouble with, really, is what’s in the middle of those. What I know how to do fairly naturally—though not without pain and struggle—is follow my own obsessions and enthusiasms as a north star, and I also know how to be an employee and say, okay Disney, tell me what you want and I’ll do my best to deliver that. I think most careers, though, happen in this middle space where you’re really trying to give everything you’ve got to something but also handing over all the veto power to a corporation. That is something I’ve never figured out how to do, but when I’m a contributor to a team, I’m happy to do it. I had a great experience with Disney, I felt respected by all the people I was working with, I was well treated, and I was paid. It was a very fun project, but of course it was a very different mindset.

For better or worse, when I’m doing my own stuff, the only thing I can point towards is the spark—the idea that brought me there. Whereas when you work for people, they give you notes and some of the notes will be more interesting than others, some will be more inspiring than others, and some will make no sense at all. But you do your job to respond to those and try to make the most valuable thing you can out of those. Then five other writers work on it and it becomes whatever it becomes; I don’t kid myself that I’m an auteur in that realm.

Are you able to discuss these other projects that didn’t pan out with Hollywood?

It’s been all kinds of things. I’ve adapted a novel, I sold a romantic comedy pitch with a buddy years ago, I’ve written a couple of TV pilots, and some other things that aren’t springing to mind. I don’t spend a lot of time in LA hustling—I spend almost no time in LA hustling (laughter). These have all been things that have fallen into my lap, and I’ve been very lucky—you never know if there’ll be another one. I’ve had indie things, too, that I wanted to get done that never got made for whatever reason.

I’m thinking now about Greta Gerwig and how you two acted together in Hannah Takes the Stairs (2007). And of course she has Barbie (2023) now and I’m wondering if you’d ever want to do something on that scale.

Yeah, sure, but I don’t think you get to do that kind of stuff unless you’re really hustling for it. And for better or worse, that’s not where my energy’s been.

Let’s go all the way back to your debut, Funny Ha Ha (2002). When I first saw that film, I was reminded of so many ’90s American independent films that I loved, a lot of which I admire for their dialogue—Whit Stillman, Hal Hartley, Richard Linklater. We can go back further of course, but when making that film, did you see yourself as a natural continuation of these directors who were getting buzz in the ’90s?

I don’t know about the buzz but that’s what the indie scene was when I was in college, when I was absorbing a lot of this stuff. That’s kind of the perverse irony of the so-called “mumblecore” thing, which people have pinned Funny Ha Ha as the beginning of a movement. Not only is it hard for me to see this movement, but it didn’t feel like the beginning of anything to me. I always felt like a very, very late straggler, like I was making the last film of 1999.

Did you feel more kinship with these directors than your younger contemporaries?

The people I got to work with and befriend, we were having some similar experiences at the time, and of course you feel personal kinship with your peers. This isn’t necessarily something I recommend, but I think I always projected myself onto older people (laughs). It’s useful when you’re a precocious teenager but gets scary when you’re middle age and all that’s left is decay and death.

Have you been feeling that a lot now? Is death frequently on your mind?

Probably more than it should be. It’s probably a good time for me to now relate to the youth. I do have kids, and that helps, but I don’t want to live entirely in the 20th century, as much as I like it there. And that’s practical as much as anything—if I’m gonna continue to make things, I have to stay connected. I’ve come to believe that the audience is your final collaborator with any work of art, especially a movie.

Can you speak to that more?

It’s mysterious because I don’t get to sit down and plan it with them. I try to watch a movie at least once with an audience. These days I tend not to go back time and again, but I do not feel like a movie is not done unless it’s received in that context. And that’s where the movie is made, in a way; it’s not a work of art unless someone’s taken it on and made something of it in their own mind. That to me is the healthiest way to think about it. Certainly in Hollywood and certain circles, within good reason, some people think of the audience as the boss. And when the boss says “jump” you say, “how high?” But with the kind of movies I make, it’s not terribly useful to think that way. When I go to see a movie, I don’t want to be a boss, I want to be interacting with it. And I try to build things for an audience so they can bring their own experience and creativity to it.

Have you ever been surprised by a response to one of your films?

I never have a clue what the audience is gonna do. And I’ve been doing this long enough that I see things shift and change. Maybe a movie that was received some way 20 years ago has gone through phases of how people seem to respond to it. I can’t track that too closely, but I truly never know what’s gonna happen until I put it on a screen and it gets a reaction.

Have your kids seen your films?

Not in their entirety, and I’m in no hurry for them to do that.

I want to ask about Computer Chess (2013), which is celebrating its 10th anniversary. Have you seen it recently?

We did a little anniversary screening here in Austin with some of the cast and crew who were able to come out for it. It’s kookier than I remember.

It feels like such an important work in your filmography. It felt out of left field and it seems like, because it was made, it helped you explore even more ideas and modes. Of course your earliest work was shot on 16mm, and then for this one you used old Sony AVC-3260 video cameras, and then you went to digital and then used iPhones for There There.

It was a huge risk—a huge leap off a cliff. There was no reason to believe that it would work, so to have had the great fortune we did, for it to be largely well received and for people to be kind to it… it was probably too emboldening. Maybe it meant I could never turn back from being a self-serving lunatic (laughter). To get away with that, you always hold this idea in the back of your head, that it’s possible. There There was an equally insane thing to do but not nearly as well received, but we shall see. It’s exciting to take these chances, and especially because you can’t do it without dozens of collaborators, so to get that kind of energy with you, behind you, around you, is really thrilling and fulfilling.

You mentioned that you were maybe too emboldened, but you also really appreciate collaboration. How do you ensure that, as a director, you’re creating a collaborative space, that you’re not imposing too much, that too much of your ego isn’t there? How do you invite other people in?

Well, I’ve got a wife and kids so I’ve got plenty of checks on my ego. As a director, I feel like the job is director—not dictator. I am there to hold an image in my mind, to have people bounce their work off of that, but I’m acutely aware at all times that the director is the one person on set who doesn’t have a… talent (laughter). Everyone else is doing something, and doing it very well. They’re fulfilling their role. And frankly, the better things are going, the less that I have to do and I’m standing by the craft services table eating peanuts. I think of my job, truly, as taking other people’s energies and directing it. I just arrange things—let’s add a little more of that, a little less of this. I don’t do the work; I just direct it. And it’s a pleasure to work that way.

My wife [Karen Olsson] is a novelist and she has to sit there and face down the blank page and herself every single day. And there’s nothing that ends up in that book that she didn’t write and agonize over. That’s a level of intensity I admire but can’t imagine doing myself. I feel very fortunate that I can get the thing to a certain point and then get a bunch of super talented, wise people to get that thing going. And if we do it right, it should end up better than what I thought it was gonna be.

Do you mind talking about the actors for Computer Chess? They really nailed the particular mannerisms of the time. Did you prepare them in any way?

I wish I could say that we all disappeared into some method cave, but I guess my philosophy on period pieces—and I’ve only ever made one—is that you can’t rebuild the past. First of all, we couldn’t afford it. Second of all, that’s not what the movie’s about. It’s not about making a movie from 1980, but it is about building that tunnel between then and now. You kind of just look for something that resonates, that gets you there. There’s that movie where Christopher Reeve time travels by locking himself in a hotel room with a bunch of stuff from the era.

Somewhere in Time (1980).

Right. And that’s what we do. We just try to lock ourselves up with a bunch of stuff and try to put away all the stuff that ruins the illusion. Once you turn on these cameras, which few people have touched since that era, it goes a long way towards making it feel like that. My cast in that movie was largely non-professionals, and real computer people. I didn’t need to train them on how to be nerds—they knew! And they had memories of these periods as well. We’re also talking about a time when most of us were kids, so we were around-ish.

Do you often think about how the technology you’re using to shoot your film, be it 16mm or Sony cameras or an iPhone, affect the intimacy presented in your films?

Absolutely. It all goes together, and that’s part of the challenge right now. Cinema—or maybe “content,” as it is morphing into now—is always on these shifting axes of technology and culture and economics. None of those things ever stand still, especially in the past 20 years, and I think about it and worry about it all the time. There are stories that maybe made sense to me on 16mm—and when I could exhibit on film, which I can’t really anymore—that I would feel like I’d have to do differently now. Even in a digital world where I can simulate 16mm, it’s not the same for me, and that’s the part where you have to keep part of your head in the present. If I shut it out and only work like it’s 1999, I’m probably not going to get anywhere interesting.

Do you remember any specific things you were thinking about when making the shift to digital when making Results (2015)?

There was a fair amount of fear and anxiety. I’ve been extremely fortunate to now make seven films with Matthias Grunsky, my DP. There’s a lot of trust there, a lot of common language. He knows my visual aesthetic more than I know it myself, certainly. There were conversations we had in terms of lenses but essentially, that was a movie that was supposed to look glossy and new, like you were hanging out in Whole Foods. That was the aesthetic. That wasn’t a language I knew well or was comfortable with but it was the language of the movie.

I’m really struck by the aesthetic of it being like you’re in Whole Foods. Did you have a specific vision or feeling you were trying to capture for Support the Girls (2018)?

It was a little grungier, obviously. But it’s a movie with neon beer signs and there was a lot we could play with there. It moves differently, there’s more handheld in it, and there’s a ton of choreography in it. This is more on my side of directing than something purely visual, but just the way that script was built—there were very few conventional scenes. Lisa (Regina Hall) starts to deal with one crisis and then another crisis makes her turn around and go somewhere else; we almost never sit still in that thing, and that impacts how you design every shot.

It’s funny the way it relates to There There, because in that film we have these different scenes, and we see how it keeps moving from one pair of people to the next. But because nobody in the film is in the same shot at the same time, there’s a disjunction amid the continuity that isn’t quite like anything I’ve felt from a film before.

It was a huge, bananas technical effort. There’s this particular disjunction at the heart of it—technically and story-wise—so I knew I was making something that there wasn’t any reference for. I couldn’t look at another movie that had done this. I ran tests, and I was able to see how it felt for five minutes, but the only way to know how it felt for 94 was to make the movie. There’s a constant learning curve. This is true of all my movies but was true in a more extreme fashion on this one—it lives and dies on performance. We’re gonna have something visually interesting because it’s weird, but we’re not gonna move the camera, we’re not gonna distract you, this is only gonna work if you find your way into these people and this weird feeling—or not having this weird feeling—of what’s going on between the people. Do you feel them being thousands of miles away or not?

Perversely, for being like the smallest thing I’ve ever done, it was a huge production. We were shooting in many locations in multiple countries, and over the course of many, many months, we had over 80 hours of footage, which is the most I’ve ever had by a fair bit. That’s not 80 hours of alternate angles and alternate scenes, it’s just 80 hours of us drilling the same material and trying to look for what we can in it. I needed as many options as I could for editing it.

How was the editing process?

Excruciating. Because we were shooting over the course of six months, I was starting to edit the material during that, but I couldn’t know the shape of the movie until I had it all. And at this point, as with many painful experiences, I’ve blanked it out in memory (laughter). There was some number of months where I was banging my head against it.

I wanted to ask about the musical interludes in There There by Jon Natchez. I’m curious how you came about that decision and how you know Jon specifically.

That was in the script. As I was figuring out how this thing would work, and pretty early on, I thought that if I’m gonna have a movie where two people can never be in the same shot and all I can do is shot/reverse shot, I need some space, some place to breathe and absorb. I love music in movies—I love music not in movies too—and it’s always a pleasure to work with. As I was thinking about interstitials, I was thinking of a musician who could do all kinds of stuff, throw curveballs, but also in their own way be a sort of character. They never speak a line of dialogue and never interact with the other characters but are their own narrator who is on his own funny musical journey that resonates with everything else.

What I had written was someone playing a half-dozen instruments, and Jon was the first person I thought of. I’ve known him since high school, and he’s an extraordinarily talented guy. He’s made a career out of being a utility musician—he can play anything so he’ll show up for a bunch of bands. And currently he’s a member of The War on Drugs, so I’m very lucky he had time to do this. It was incredible fun to work with him to craft those pieces. I’m very upset with the gods for not granting me musical talent in my lifetime, and the closest I can get is working with a guy like Jon and communicating with him about what I want to get out of these pieces, and let him go away and build magical stuff.

Magical is a good word. I like how the interstitials stitched these scenes together, but also how they were reminders to have you believe that these people were actually in the room together. That’s the main thing I took away from your film. It reminds me of this Richard Linklater quote… I think someone asked him about mumblecore, or maybe just about his dialogue being improvised. I remember him getting upset and saying that none of his dialogue is improvised because when you feel that fiction films are “real,” it’s actually because the script has been carefully crafted. When watching There There, I was thinking about your first three films especially, and how all film is artifice and how this artifice is used to create these real, intimate stories; your new films leans into the artifice more explicitly and it felt really apt with the memories I have of connecting with others during lockdown.

That’s what is exciting about movies. There’s always a tension, and hopefully a resonant tension, between the artifice and the documentary. We’re certainly changing the dynamic of that the more we get into the CGI world; you kind of push back against the natural documentary aspect of all moviemaking, but it’s still gonna be there no matter what. All movies are a portrait of the conditions under which they were made.

Computer Chess is part of a Metrograph program, “The Color of Black and White.” What sort of things do you feel exist and are possible when a film is shot in black and white that are not when a film is in color? You of course have Mutual Appreciation (2005), which is in black and white too.

The thing I thought a lot about when making Mutual Appreciation is that black and white is funnier.

Do you have a theory for that?

Maybe because it’s deadpan? Color has changed so much over the course of movies, and you can always turn on a movie and by color alone you can quickly pinpoint what era it’s from. Black and white has not changed nearly as dramatically, in part because there’s less to change. Even as color purports to be more realistic, or “the truth”, it always seems to be making some sort of statement the way that black and white makes an absurd or comical deadpan statement. I do like it because it’s funny (laughter).

I get what you mean. It feels like there are fewer distractions, as if you’re invited to focus more on the specific dialogue and movements. Were you thinking about this with Computer Chess too, that things could be funnier because you were using these cameras?

You can do anything with those cameras. Part of what was so great about them was that not only was there no color, but the resolution was so weird. If that film had been in high definition, you would have seen everything we got wrong. You would’ve spotted every 2011 detail in there but as is, it’s just fuzzy. I was doing rudimentary effects stuff, and I’m not an effects guy, but you can just put one thing on top of another thing with those images and it looks great because it all just blurs together. There were tons of possibilities with those images. As far as what’s funny and what’s not, you guess at these things but really it’s in the edit when you watch these things and see what lands for you and what doesn’t.

Earlier you mentioned how you didn’t want to be stuck in the 20th century, is that an active decision you make? Like, for your next film are you trying not to fall back on old methods, ways of thinking, or how things can look?

It’s an active struggle—I don’t know if it’s an active decision. That’s one of the big questions of middle age, you have these memories and histories, and they’re valuable, but you know that if you only hold on to things that are dying… it’s no way to live. You have to find some balance. If there’s a chance I might live this long again, I’ve gotta be looking at least halfway forward. And in general, you kind of have no choice but to work on something that’s relevant to the moment, even if it’s only in a very personal way. That doesn’t mean I have to chase every trend—I’ve never been good at that—but I do have to try to stay alive and awake to what’s around me.

Is there anything we didn’t talk about in this interview that you wanted to mention? Anything that sprung to mind during our conversation?

Things that spring into my mind spring right out moments later—it’s all lost (laughter).

There’s a question I always end each interview with, and it’s something I actually ask my students—do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

What do the students say?

The most exciting thing for me about this question is that it doesn’t matter how people respond, including them not giving a response, because it reflects something about the person regardless. Some of them will goof around and say that they love that they’re annoying, some will mention that they love their hair, maybe something about their personality, or something about other people—like that they have good friends in their life. And some refuse to answer, and I love that response too.

I’m close to that latter camp, I think. I’m wildly insecure, and I wouldn’t be doing this if I weren’t. I like my movies, but part of the joy in doing this is that in looking back, I’m looking back on the work of however many dozens of other people I got to bring their magic to it. I’m happy and grateful that I got to do that.

Why do you feel like you wouldn’t be doing what you’re doing if you weren’t insecure?

It seems to be a common thread for a lot of artists. They struggle with these things, and the struggle is the work.

I remember this interview from a decade ago where you mentioned how it made sense that in Funny Ha Ha you’re playing this self-destructive guy. If you were to write another role for yourself, do you think it’d be a similar sort of character?

Good question. Anytime you write something, I think you’re trying to go into new territory, or at least I am—I’m trying to do something that I haven’t quite done before. And yet when it’s all done, you go, “Oh wait, there’s me—it’s just another self-portrait.”

Andrew Bujalski’s Computer Chess plays as part of Metrograph’s The Color of Black and White this weekend (August 11th and 13th). His newest film There There can be rented, purchased, and viewed at various streaming services.

Thank you for reading the 32nd issue of Film Show. Someone please write about why black-and-white movies are funnier.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.