Film Show 031: Deepa Dhanraj

An interview with Deepa Dhanraj about Yugantar—India's first feminist film collective—and works from throughout her career. Plus: an essay on Yugantar's short films.

Deepa Dhanraj

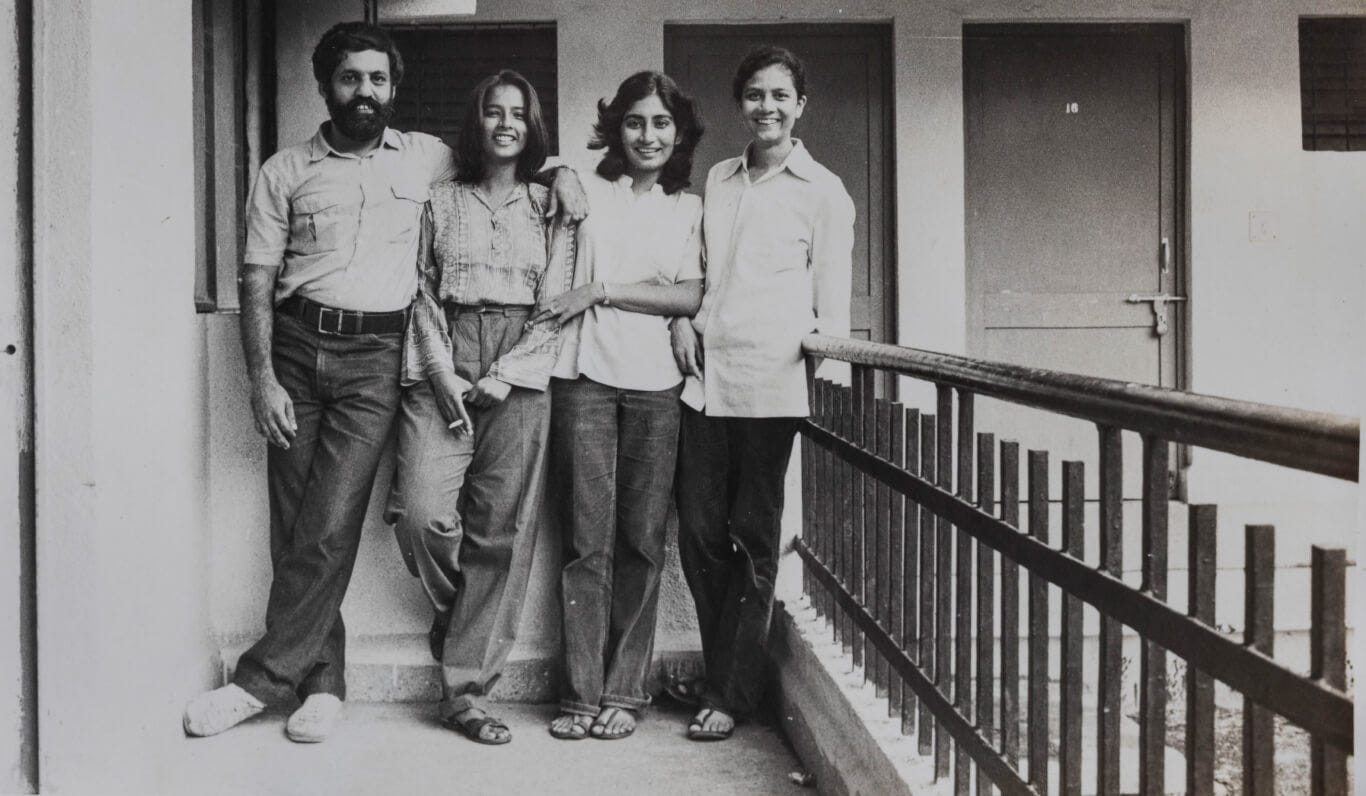

Deepa Dhanraj (b. 1953) is a researcher, writer, and an independent documentary filmmaker based in India. Her documentaries and writing span a period of forty years and engage with questions related to women’s status, political participation, and resistance. Alongside Abha Baiya, Navroze Contractor, and Meera Rao, she co-founded Yugantar—India’s first feminist film collective—in 1980. Together they made four films between 1981-1983: Molkarin (aka Maid Servant), Tambaku Chaakila Oob Aali (aka Tobacco Embers), Idhi Katha Matramena (aka Is This Just a Story?), and Sudesha (aka As Women See It) . All these films, along with others she made since the collective’s amicable dissolution, can be found on the Criterion Channel. The Yugantar films were showcased in this year’s Berlinale, and Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Dhanraj about her life and work on February 23rd, 2023 via Zoom. Below, find their discussion below, which touches on her childhood education, becoming radicalized, the Yugantar collective, and various films from throughout her career. Afterwards, find an essay by Zachary Goldkind about Yugantar’s films.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Can you paint a picture for me of what it was like for you growing up? What memories do you have of your childhood?

Deepa Dhanraj: Well, I grew up in South India. So first in Hyderabad, a city to the south, in the center of the plateau. It’s a very old city. I think my most formative experience is that I went to a school that was founded by the philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. At the time, it was a very experimental kind of education because it believed in enabling students to think critically, to question everything. And he didn’t believe in competition—that children should compete against each other. We didn’t have any exams, which are very stressful for the children in India. There are constant sets of exams and tutorials, and huge amounts of pressure because of the competition to get into a university—you need such astronomical marks to even qualify to get admission. So, it was a very different kind of school. And I think the biggest gift it left me with is my eternal interest in learning—my insatiable curiosity.

And the other gift it left me with is that I have no fear about learning something new. I find people are quite fearful, like… can we actually do this? Whereas I was quite heedless and quite happy. I was not overconfident, but it never occurred to me that there’s something I couldn’t possibly do. I don’t mean like becoming a cardiac surgeon or whatever, but I mean generally in terms of trying to understand things. I was very attracted to social sciences. I think in another life I would have happily been a historian, researcher, or sociologist. I’m very drawn to that—of being with people and just understanding their lives, everything about the context they live in, the way they describe themselves, or where they are situated. I would say that my education was huge, huge. The biggest influence, I think.

Was this in grade school or for your secondary education too?

Until university. If you think of India then—and I’m talking about joining university in 1970—there really weren’t so many jobs in what we call the private sector. So for most middle class families, they would join some form of government service, or civil service. And I think even for my parents, that was the dream—that you finish and then you apply for these competitive exams and you can join government service, which of course I didn’t do (laughs), to their disappointment.

And this was public education. I think of the difference between then and now, and we really studied for almost nothing. It was so inexpensive to go to university—the tuition fees were so minimal. The school I went to was pretty much all middle class kids. We had a couple of students who were there on scholarship, who were from a different kind of class background, but not so many; it was a pretty homogeneous group. Then you go to college, and that’s where I think, as a middle class Indian, you meet students who are from all classes for the first time. There are also students from semi-rural areas, students whose English isn’t very strong, who speak basically many Indian languages, who all come from very conservative families. And I went to a girls’ college, so you’ve got the gamut. It was my first time being really exposed. It was a boarding school—a boarding college—so we were living together as well. I think that was my first experience of trying to understand students who came from very, very different backgrounds, both religion- and class-wise, even caste-wise. It was big. It was an eye opener.

And then the next college I went to in Hyderabad, that university was on fire. There was a very big movement for statehood, and students on that campus were very much part of that struggle. That campus was very political. We had major political parties within the student unions—they were definitely affiliated to political parties, and these groups were very active on campus. The group that was most active was sort of a far left group. They weren’t just working on campus, but also in the state and around issues of land rights, many things like that. But on campus, those debates and those talks… it was a very, very vibrant time.

Coming out of all of this and then leaving university—frankly, I really didn’t know what I wanted to do. I mean, I had studied journalism and I interned at a newspaper and stuff but I was just confused about what fits or what appeals to me, you know? What would I consider interesting work? And it was just about that time when there was a family friend who was considered one of the first very important new wave film directors.

Which filmmaker was it?

His name was Pattabhirama Reddy, and he’d made a film called Samskara (1970), which was based on a novel written by a very important writer called U. R. Ananthamurthy. And that novel is very subversive because it challenges the whole notion of caste. It was politically, I would say, very radical for its time. He had made that film and they called it the new wave of filmmaking. Most directors who made so-called arthouse cinema or non-mainstream cinema had very little money. There was very little funding. There was a government corporation that was called the Film Finance Operation in those days, now it’s called the National Film Development Corporation. So you could get a loan, but the loan was not really a big amount.

He was making a second film and basically just needed people to do work. And he said, “I can’t give you a salary or anything, but you get room and board.” And it just seemed like, okay, why not? When you’re young, you just feel like, okay, let’s try this. Who knows? It may be exciting. And that’s how I became an assistant to feature film directors. It’s not the best way to learn filmmaking, I have to admit. It is efficient in a sense that you have to do so many jobs. You’re basically handling sets, you’re handling props, you’re handling costumes, and then continuity writing, and now and then you’re locating—not extras, that’s a horrible word—but people to fill a street or casting of that kind. And so it’s just a spin, doing all this kind of stuff.

Anyhow, I worked with two feature film directors in Karnataka, the state that I live in. And then I think the biggest event that shaped my thinking, my political understanding, was what we call the Emergency. And that was very important for my whole generation and for me personally because there was this director whom I had worked with—who was also a very close family friend, this much loved mentor—and his wife was arrested during the Emergency. She was put into almost solitary confinement. It was a very traumatic time because all civil liberties were suspended. The entire opposition was in prison and there was complete censorship. Campuses were terrible—there were lots of student disappearances going on, extrajudicial killings were going on. All this news was filtering in and there was no question of habeas corpus or bail or anything. We didn’t even know where people were. They’d get picked up at night, and you literally had to go to court every day to get lists of who was presented by the police. Those lists had to be circulated because families didn’t know who had been picked up and which prison or which police station they were in.

I think the Emergency, for many of us of that generation, was really something that radicalized us. An entire generation. Though I had gone to Osmania University at the most political time, I used to observe things more as an observer; I didn’t get involve, it just seemed very intimidating. But I think the Emergency got all of us involved with the things that were happening. The powers of the state—the impunity and the powers of the state—it was so in your face that you could not ignore it. So there was a kind of political baptism from that point on. I mean, you’ve seen the Yugantar films, and many of them have an interrogation of this aspect, whether it’s population control or something else.

And the thing is that before the Emergency, the number of women who were involved in all kinds of politics—whether the rising price movement or all kinds of things—there were women everywhere. And post-Emergency, I think for a lot of women, they were coming out of left trade unions, they were coming out of Gandhian groups. There was this idea that what we call The Women’s Question—issues that are related particularly to women, political questions—were not being taken seriously in many of these traditional political groups. When women started coming out, that was the time, really, when I sort of officially joined the women’s movement. That was a very vibrant, very exciting time. I mean, there was so much happening. There was poetry, there were plays. Nobody was making films with that kind of intention, though, except us. But writing—there was so much writing. There was art. So much was happening. Of course, there were things like filing cases against custodial deaths or custodial rape. Even looking at the whole question of bringing perpetrators who, like in one case, were actually policemen to justice.

Hearing you talk about the school that was founded by Jiddu Krishnamurti is very exciting to me because I’m actually a high school science teacher. A school that is so uninterested in having students compete with each other is a dream, because that’s such a detrimental structure to have the students learn in. When you reflect back on that time, prior to college, do you feel like there are any moments that are emblematic of how that environment really inspired you to have that insatiable curiosity?

Well, what used to happen is that every year, [Krishnamurti] would travel abroad a lot. And I think he also lived in Ojai, California. But he would come to India for three months in the winter, every year. He would spend two or two and a half months in school. And, of course, you know how irreverent kids are—we would call it his traveling circus (laughter). So every year there would be these amazing people who would travel with him and they would also stay, and they were given chances to do things with students if they wished. I can’t even imagine something like this happening today. We had, for example, Raja Rao, this incredible writer. He wrote in English, also.

He turned up and, in the late ’60s, there was this whole performance phenomenon called Happenings, and he decided to do one in school with us, and he chose this hilltop. And we were told the whole point of a Happening is that it’s spontaneous and you can do what you like. And being brats, of course, we would disappear (laughter). We’d go to the hill and we’d say, “Oh, we’re here, we’re here.” And then we’d just vanish, you know, it would be like water in the desert. And how would he ever find anybody? We did that a couple of times and then, of course, we had to draw the line. But the idea that we were exposed to this kind of performance art!

I remember there was Maynard Ferguson—this jazz trumpeter turned up with his whole family. And that was extraordinary, that music. And then there was a Vietnam deserter who was African American; he gave the school a Joan Baez album. I’m just giving you a gamut of the kind of people. For those three months, I think for two or three hours a day, regular classes were suspended so we could attend his talks. We could interact with these people. If you think about it now, that students from the age of 8 to 17 had to all sit in on all these kinds of events to participate or be in the audience, I mean, it’s inconceivable to me that it could happen today.

I think the most memorable thing for me, also, was our library. We had a fantastic library. Various people would donate their entire collections, adult collections. It was extraordinary. And then this love for literature, for poetry. There were poetry workshops, there were writing workshops. We had to do the state curriculum, whatever the state curriculum was, because we did have one exam at the end, which we had to do or we wouldn’t get admission into university. But when I think of the general pedagogy, it was very different. And the thing is that you weren’t marked—it was really felt that we needed a fearless classroom. Students should be free to speak. And we were very cheeky. There was a wall newspaper, I remember, and we put it up and we could put things in it which were even critical of the administration, and then of course, they had to be cleaned up (laughter).

Every time Jiddu Krishnamurti visited, they would do a proper two and a half hour dance ballet, which was actually quite beautiful and extraordinary. And we had a very excellent classical music teacher as well, in Carnatic music. So it was a very high-standard department—nothing was dumbed down for kids. And because these dancers had to perform so much and they had really long rehearsals—two, three hours a day—they were given extra eggs. So there was this mention about how unfair it was that some people got extra eggs and that there was so much bias and favoritism to these dancers. Just kids, you know (laughter). But the atmosphere was that you were encouraged. You were really encouraged to be thoughtful, to have your own views. And if you look [Krishnamurti] up, you get a sense that his whole philosophy was really dependent on questioning everything, relying on experience. And I think because the teachers were also followers of his philosophy, it percolated down to the students.

It does seem unthinkable that all of this stuff could happen in a school today, yeah. I do want to ask, you went to the girls’ college. Do you think it was significant for you that this was specifically a girls’ college? Do you think that that had a significant impact on you?

Well, I would strongly advise it, actually, because I think it reduces the stress of being in a co-ed institution. I’m not saying that it necessarily has to be stressful, but there is a way in which it does cause certain… (pauses). Imagine, I joined college when I was 16 and I left when I was 19. We had a three year Bachelor of Arts in those days. At that age, when you’re dealing with so much and you’re figuring out who you are and your emotions—everything—I think it’s very comforting that you don’t have this extra thing of figuring out boys as well. You know what I mean? As far as social sciences go, it’s okay. But I think if you’re trying to do science or math and you’re in a co-ed place, I think it would be very stressful for women.

In what sense?

Because of the way you always have to measure up. I’m talking about in the ’70s, in one of our best engineering institutes, which is called the Indian Institute of Technology. What was the percentage of women who actually joined? Very, very low. Because in any case, girls who did science or math, it was thought that this was really not a place where you should be. So I think for women students who were taking those courses, I think it must have been a very secure place to do well because you didn’t have this extra bias. I think it was really fine, except the library sucked (laughter). I mean, it was just so pathetic I couldn’t believe it. But otherwise, I would say it’s a very safe and secure place to come of age.

ou mentioned how after this girls’ college, you went to this other university and with the Emergency happening, you were radicalized. But I’m wondering, do you think there were any seeds planted for you at this university, that got you to be more politically aware?

Firstly, I think when you have this kind of middle class life—my father was in the Indian Air Force so we moved a lot, and then wherever you stay will be Air Force compounds and they’re already little gated enclaves—I think coming here was like an explosion. You suddenly meet students whose families, whose parents are—and I’m saying this in the best way—literally daily wage laborers. You meet students whose English is very, very minimal, and who have come from backgrounds that are, as I said, right from daily wage laborers to working class, lower middle class. There were, of course, middle class students as well. It was such a large university and my college was small. So suddenly you’re exposed to these students, their sort of realities, and you become really super conscious of your privilege and what’s available to you as a middle class Indian. There are your social networks, which you can deploy to even get ahead within the job situation and with other academic opportunities. All this was very, very clear.

But I think the main thing for me was just watching the student activists on campus. They were, frankly, just dazzling. Firstly, their concerns were not just about student concerns like customer fees or dorm fees or what you were paying in the dining room or even what we call reservation, which is like affirmative action—how many of those seats were being filled by students of marginal groups. Those are all very valid issues that political groups take up on any campus, even today. But these people were really talking about politics outside campus. One of the biggest things was land rights. And another was what we call bonded labor—slavery, indentured slavery. Children are handed over to landlords in lieu of a debt, and their labor is supposed to compensate, and they’re in brutal conditions. They would talk about things like that. They were talking about caste discrimination. And there was a very active, extraordinary group called the Progressive Organization of Women, and it was actually the first student feminist group ever to be formed in India. If you go to our website, you can see their manifesto along with the manifesto of this website.

So here were these women also talking about patriarchy, talking about the conditions that oppressed women, talking about interrogating family structures. It was a very special group of students and there were multiple kinds of these factions on campus. It was very, very exciting. Some of them are still my friends, very good friends. And one of the things I want to do is oral histories of some of the women who were part of the politics at that time and who have stayed in political life as well, or who have stepped down.

I feel like so often people forget that a lot of people’s lives are built from seeing other people live very politically charged lives. It’s nice hearing that you feel you are standing on the shoulders of giants, so to speak, from what you saw at this university. You mentioned how you worked with Pattabhirama Reddy. I’m curious, are there specific things that he taught you, either directly or indirectly? Are there things about who he was or the way he directed that stood out? Was there something about his personality that had an impact on you?

In general, I would say that he was the most extraordinarily nonjudgmental person. You can imagine, at that time, for an older man to be so accepting, so nonjudgmental… he had an extraordinary education himself because he went to Shantiniketan, which was started by Rabindranath Tagore. He was a poet and a mathematician. And he married—it was extraordinary at the time—he had an interfaith marriage with a Christian woman. He was an extraordinary modern Telugu poet. But more than anything, I would say that he had a very nonjudgmental nature, and he invited everybody, especially young people, just to be the best that they could be. He supported them in that way. I’m going to be 70 this year, and when I think of him and when I first met him—I must have been 20, 21—and the kind of time and patience he had for all of us… for an older person to have that extraordinary generosity, to really support and nurture young people, this was extraordinary. Even when I think of myself now, I’m always there for young people if they want something, but he was something else.

It was this and their house. I have to tell you, it was not just him. His wife, Snehalata Reddy, was a theater person, and they started this extraordinary group called the Madras Players, which was very well known. They did a lot of plays and moved to Bangalore from Madras. But she was also an extraordinary person. And also their house was… how shall I put it? It was like a salon. At any given time you would find writers, you would find poets, theater people, artists. You just had to sit in a corner, and as a young person I did that a lot and just sort of bathed in that atmosphere. It was the most extraordinary education because of the kind of debates we had. Sometimes people would stomp off, there would be these bitter conversations, but the thing with Pattabhi and Sneha was that they held the space, they held that space for anybody to be who they were. They were entitled to their opinions. It was very formative for me because at 21 or 22, everything you know when you come out of university is really from books. You haven’t really been exposed to people who are actual practitioners in any field, whether they’re authors or poets or theater people or artists. My life would have been very different if I hadn’t met them or been part of that.

You mentioned that there was a director’s wife who was arrested during the Emergency, was that Snehalata Reddy?

It was Pattabhi’s wife, Snehalata, yeah. It was very tragic because she was asthmatic and it was very difficult for her in prison. She must have had at least two heart attacks, which the prison doctors didn’t reveal. Every month they would ask for parole, that she be released on bail, which was routine, but they refused even on health grounds. I think with the last heart attack they got nervous because they didn’t want her to die in prison, so they released her on bail. And ten days after leaving—two weeks, maximum—she had a massive heart attack and died. She had this prison diary that she wrote and that document actually became… in today’s words we would call it viral, but we didn’t have the internet. When she was released that was also when the Emergency was lifted and they declared elections. Her diary became a document that was widely circulated as evidence of the Emergency’s abuses—and there were many. I’m telling you all this because it was very personal for us. We’d go on prison visits to see her.

Obviously there’s Samskara, but then there are other films in the early-mid 1970s from India that I’m curious if you watched and were influenced by. There is Maya Darpan (1972) by Kumar Shahani, or A Historical Sketch of Indian Women (1975) by Mani Kaul.

Did you know that my husband, Navroze Contractor, shot Mani Kaul’s Duvidha (1973)? He was the camera operator.

Oh, I didn’t know that, wow. Were you close to Mani at all?

Not me, but my husband was, because he was also in the Film Institute when Mani and Kumar were there. So he knew him well, and that generation. But the thing is like, yeah, of course we know these films. Apart from that there was also a very, very vibrant film society movement in India. And we had an extraordinary director called P. K. Nair who was head of the National Film Archives. He collected an extraordinary number of films from all over the world, and he was very willing to loan them to film societies for screenings. So the film society movement was where you really got to see international cinema. And because of our political affiliation—India was non-aligned but also definitely tilting towards the Soviet Bloc—a lot of the films came from Eastern Europe, like Czechoslovakia, Poland, Russia, Bulgaria. So if you were an avid film society member, you did get to see a lot of amazing international work, and all on celluloid. You can imagine, they were 35mm prints that were screened. You had to go to a theater to watch it.

Do you feel like any films that you watched were particularly impactful, or was it just more generally seeing that this is an art form that had all these possibilities?

I don’t remember anything as being impactful, per se. Films were around. I think Ritwik Ghatak, for example, and of course there was Satyajit Ray. I wouldn’t say they were influential in any way. The thing is that I never went to Pune, I never studied in the Film Institute. So for me, I watched films and took them in, but not really as a film student, not in that sense. And I think Ritwik Ghatak was there too. I don’t know if you’ve heard of John Abraham, he was also there then. He was also very influential in Kerala. So there were certain directors or technicians who came out of the first or second batches of the Pune Film Institute. A lot of younger filmmakers followed that stream, those aesthetics. Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, John Abraham… these films were aesthetically very new, formally very new, quite extraordinary. I don’t think today we even have anybody that wants to take these risks, cinematically, to formally go out on a limb the way they did. Really extraordinary stuff.

But personally, for me, I don’t think these are really my influences at all. It seemed like they belonged to a different context, a different philosophy. You had to be literate in film to understand what they were doing, and I never had that literacy. They were coming out of a very different formal education in their films. Kumar Shahani would go on about Bresson and how it influenced his work. When we started, Yugantar was such an audacious experiment. Because except for Navroze, who had a proper film background, I had worked with three different directors, but I had no experience in documentary. It was very hard to watch documentaries in India except for in these foreign embassies. The National Film Board of Canada would give films to schools. I remember at one point somebody asked, “Why are these Canadians obsessed with salmon?” (laughter). All the films had this salmon, they were sleeping and going back home to a farm or wherever it is. I’m not being funny, but you know what I mean? I think that there are some films which are made to be sent out to schools. So where would you watch creative documentary or where would you get an education in documentary cinema? It really wasn’t there.

You could go to film festivals. I still remember a film festival I attended in Delhi, and there was Barbara Coppola’s Harlan County, U.S.A. (1976). I was just shocked that it could be a film. When the film started, the hall was 80% full, and when it ended, there were three people there—I was one of them. I was just so shocked and taken with this idea that she stayed with that movement, that she recorded it the way she did. And it’s narratively very engaging. It was the first time I was watching something that’s cinema verité, that’s also political, that’s edited in a way that also holds your attention in the sense of a narrative. And it’s also complex in terms of everything that happens around a movement and strategizing and all of that stuff. So I think definitely, for me, documentary fascinated me from the beginning. It’s just something about real people, their situation, and their voices.

In the first Yugantar film, Molkarin (aka Maid Servant) (1981), what I really appreciated is that so much of the film is just simply watching these women talk in a group, and how productive and lively that can be. We’re just watching them talk, and later we see the actual seven demands listed. They would seem radical even for today. This was the first film that you had made together. How did you initially approach this? Were there specific ideas you had? Was there debate?

So Navroze was the only one who actually had film experience. Then there was Abha Bhaiya, and Abha was an activist, and she went on to start two of the best known feminist organizations, which are still very active today, Saheli and Jagori. And Meera Rao was a writer. I’d come out of this assistant director thing. The thing is, for Abha and me, we were both part of the women’s movement. The idea that this very first domestic workers union had started out of a spontaneous strike led by women was so exciting. I remember both Abha and I were thinking that women’s labor is invisible—it’s not documented anywhere, nor is it written about. All women’s movements, of women’s struggles to even form a union, these things are completely invisible. So I think for us, after meeting them, one of the first things was just to look at them: look at how strong they are, look at the brilliance of their thinking! They can completely theorize from where they’re located about the situation, about the fact that it’s their labor that frees up middle class women to have a career. These are very political ideas about the reproductive labor of women. Even the question of, how would you put a wage on it? Because women’s work has no value to begin with. How do you monetize it or create value?

Our approach was to work very collaboratively with women. That is a long process. It’s not a simple thing because you have to declare your intention, there has to be trust, they have to feel it’s something important that they want to be part of. It has to have meaning for them. And then how do you work out what’s going to be in the film? All the Yugantar films were, I use the word co-authored. Because it was like our collective meeting their collective, you know? The film is getting made in a process that’s us working together. So many of the things in the film, they wanted. For example, the idea of dramatic reenactments, which you see in both Molkarin and Tambaku Chaakila Oob Aali (aka Tobacco Embers) (1982). The women said, “No, no, it’s very important to tell the story of our union, these things cannot be ignored. These were pivotal moments. These were turning points.” And I said, “How would we stage them?” And they said, “You leave it to us, we’ll stage it.”

For us, the bottom line was really this process. It’s not just that you have feminist content or you have feminist analysis. It’s really about what the process was between them and us that led to this. And a lot of it was really in these free-flowing conversations where they were sharing what was happening. I found that so powerful. I’ve said this before that in those days, the image of a working woman speaking didn’t exist on film. It was very pioneering. If it existed, there were very few examples of it. The suppressed voice became very important. I’ve often been asked, “Why didn’t you write an article? Why make a film?” And I always say that it’s because you have to see and hear them. There’s something about the physicality, the vibrancy—the vigor of the faces, the way they speak—that can only be done on film. In text, it would be so anemic. It would be there, but we wouldn’t get the full view of what it meant.

These were the main things that guided us. We had to work together on what the narrative would be, and we had to create a space where you could see the doing of the politics, where it’s not just the act, but the strategizing too. And if you look at Tambaku, we went one step further because in the end of that film, I have this very long sequence which is basically three takes. They’re all yelling over each other. It doesn’t have a neat, tidy coherency showing the decisions they have reached, but I wanted to show that that’s how they do politics. That’s what their meetings are like. It’s noisy, it’s messy, it’s incoherent. They’ll get there at some point, but you have to get a sense of the process.

There’s one quote in Tambaku where someone says, “If a woman is afraid, another woman should give her courage.” The films are constantly reinforcing this notion that this struggle can only happen through active encouragement, through work that’s done as a group. This is not a solo effort, and change is not going to be handed to us. I appreciate that you show the entirety of this process, and how it can be messy but that, ultimately, the goal is to work together, to embolden each other. And you’re right: the image is just so important to capturing everything. If it was just text, it wouldn’t be the same. I’m curious, then with Tambaku, what sort of things do you feel like you collectively learned from Molkarin that you wanted to do with this next film? Were there specific things that you felt worked or didn’t work?

We got a lot of confidence that this approach of two collectives working together could work. I think because, with the first one, it was very tentative. One big takeaway was that we could continue with this process. The second takeaway was that we had to spend a lot of time with them before filming; we actually lived there for two months and didn’t film a thing. They would come back from the factory or at night when they finished all their chores, and they would come by to where we were staying. There were these free-flowing conversations and I’d take notes. A lot of the narration in the film is really things they have said verbatim, which I made note of. When we were ready to do a narration, I read out things to them and I said, “You know, this is the kind of stuff you need, and this is what you said, and how do you think we should write it?” That really helped.

The challenge with Tambaku was that no factory owner would let us in. It was in a small town, and you’re identified because you’re walking with them and sitting with them. They knew very well that we were friends with the union people. Finally, one woman persuaded her factory owner. He thought, okay, I’ll give you two hours—what could you do in two hours? So for two hours we were shooting like crazy. But before we went in I told her, “You have to tell us what to shoot.” It was the first time we were seeing the factory, we had heard about it from them, but we hadn’t actually seen the place. I mean, you go in, what are you supposed to film? They were literally directing that sequence. “Okay, now you shoot the beating of the tobacco. This is a machine. Now you shoot us sleeping on the tobacco heaps as we do after lunch. Now you do X, now you do Y.” It was extraordinary, that whole thing was being directed by them because we were clueless.

That’s amazing, I hadn’t considered that. I love that they were such active participants in the making of the film.

We learned that from the first film and we expanded it in the second one. Totally. That’s what they wanted the story to be. The whole beginning of the film came from them. When she’s putting this roti and this flour and she’s wrapping it up and stuff. That’s something that, in the earlier conversation with that same line, she said, “A dog can sit in one place and eat, even that is not available to us.” I remembered that line, so I asked her, “You remember you said this, right?” And from that came this idea of how to shoot the beginning of their day. They’re running and they have to eat while they’re running, because if they don’t get there by eight, the gate closes. So many of the sequences came out of things they said. We asked, how can we give that feeling? Even that night sequence, where they’re walking with lanterns because it’s so late and they have these incredibly long shifts, all of this stuff came from those conversations and saying, “How do we film it?”

And the strike, that big strike with 800 or 900 women. They were so keen that this had to be in the film. I said, “How on earth are we going to do that? How do you recreate a strike with 900 women?” And they said, “No, leave it to us, we’ll do it.” They mobilized the women. And I thought, what about food? You can’t expect women to stay here one day, one night. We didn’t have that kind of money. I was very worried. What are we going to eat? How can we do this? You can’t ask women to come and have no food. No. In India, for us, it’s very important—you have to feed people. And they said, “No, no, you leave that to us as well.” (laughter). And the solution, the brilliance of the solution, and the solidarity of that…. they went to each house and they said, “You give two rotis.” That’s it. Every home can spare two rotis—it’s not too much of a burden. So that’s how they collected the food, which they then distributed. At night, they did the cooking of the rice. I just felt that sequence was so important to them. And then organizing the fire engine for water. All that was done by them because it was a story that they had told us, because that strike is what actually broke the back of the owners. That’s when they realized, okay, we have to surrender. So for them in their union story, if you didn’t have those visuals, it didn’t make sense at all.

What was the response when you screened the film for them?

Well, the first time we screened it, we screened a rough cut. I wanted them to approve the rough cut before we finalized it. We had to go to a theater, and there were like 300 women there. We had to screen it many times because the first time they were very excited, just recognizing themselves on screen (laughter). And the whole thing of, “Oh, that’s me! That’s you! Why are you talking like that? You look so weird.” So at first they weren’t watching the film at all, it was just this response to it. We had to show it like three or four times and then say, “Now watch it and tell us, does it work or not?” It’s only when I got their consent and approval that the cut was okay. And then finally I brought the finished film to show, and it was this extraordinary experience. Because where can you show it to 3000, 4000 women? We did it on the highway.

Oh, my god (laughter).

Yeah. We stopped the traffic on the highway. I must say, these truck drivers were very cooperative. We said, “come watch the film also.” And we had to steal power from somewhere and set up a screen. And women sat all around the screen: behind, in front, on the sides. And again, we had to show it three or four times. But I think more than anything, apart from the screening for them, I think what really made them very proud and what really mattered is that we were distributing the film. The film was traveling to places where there were women workers like themselves. We would always inform them, we’ve screened it here, we’ve screened it there, and these were the kind of responses. I think that was the most motivating thing, that their being part of the process had led to something.

That’s so wonderful to hear. It’s also just one of those things like, could that even happen today? Having a screening on the highway is just an incredible image.

I think India has so many community documentary programs. It’s really taken off. And the interesting thing is it’s being made now by community people themselves. And I think this is a huge shift from what we were doing then and what’s happening now. So there are many projects where you have, I think they call it community media now, but where you have people from those communities who are making and screening work. So that tradition is alive and well. And now you can make it on your phone. In those days, the technology was so difficult because we were doing it on 16mm film. It was very different.

So Yugantar made two more films. There was Idhi Katha Matramena (aka Is This Just a Story?) (1983), and that one is presented as fiction. There’s one part in the film where the girl is with the older woman, Rama, and she’s saying, “I used to get so much courage from watching you.” Something I think about a lot is how we can get so inspired just from seeing others live their lives. Rama was just filing for a divorce, it’s not like she was doing that for other people. But just through living fearlessly, she was able to inspire. I’m curious if there are people who stand out as inspirations to you just from the way they live their lives. And, at the same time, if you’ve heard anyone say that about yourself.

Well, I don’t think I’ve inspired anybody (laughs), but I think a lot of people have inspired me. There are women who’ve led extraordinary lives, publicly and privately in a very conservative patriarchal society like India, and with the kinds of barriers they have broken… in every sense they have been very inspiring. A lot of them are good friends and from my generation. But apart from them, with every film I’ve made, the women I’ve filmed are so inspiring. Just the way they live their lives with all the challenges that they face. I have a sort of aversion to telling victim stories. Or maybe it’s not that I have an aversion to it, but that I’m a hopeless optimist. It’s not that these stories don’t exist—of course they exist. Horrible exploitation and abuse, all these things are there and they will be part of the film. But I always like to turn to the way in which women rise, either above it or through it. It’s not that these are positive stories, it’s not that. It could be something in their attitude to what they’re facing, or it could be how they think. It could be many things. It always has to be something where they are coping and are providing us with an absolutely against-the-grain view of what’s going on. It is an ambition of mine to learn something that’s against the grain, that challenges all your assumptions about a community. I’m going to send you a link, if you have time, for a film I made on a group of Muslim women in South India who have their own court.

Oh, is it Invoking Justice (2011)?

Yeah. Have you seen it?

Yeah, I was actually going to ask about that.

So you see what I mean with that film? Though they’re dealing with the most terrible cases that are brought to them, look at how they handle things. Look at how they think about what’s happening. Their courage, their brilliance. For me, that is very, very important. In Idhi Katha Matramena, the story is this radical idea of female friendship. She attempts suicide and recovers. But then the question becomes, can you imagine a life lived in female friendship? So in that, there are two individuals. But this idea of a support system… is that possible? I think that’s something that started then and has stayed in a lot of my work. When you look at women doing politics together, you see it. You see that collective energy and you see that there is a scaffolding there that’s holding them up. You see it in Something Like a War (1991), in Sudesha (aka As Women See It) (1983), and in Invoking Justice. It’s there.

What, to you, makes female friendship radical?

In those days it was a radical idea. There is such a division, where anything that happens in the family is private. Whether it’s violence or abuse, this is not something that should be revealed outside—it’s shameful to reveal this, it’s breaking a social value. So the conversation between them is already very radical because she’s choosing to talk about what happens inside the family to somebody who’s not in order to get support and to be understood, and for her to feel that there is another way of living. I’m not suggesting she should get a divorce or walk out or who knows. But the fact is, her thinking has changed. She’s refusing to be someone who would be subjugated and take abuse. It’s not a very direct film, but it has a lot in it, which I hope people get.

I think it’s beautiful. This notion of how important it is to share with others, and how that sharing just can be like a dam breaking. I wanted to bring up Invoking Justice because in the last Yugantar film, Sudesha (1983), there’s this one part where they’re talking in a group and the women ask, “Why join a women’s group? What good is it to us?” And they talk about how men are always against it. It is a lifelong struggle to educate people, to get others involved, to constantly push back against patriarchy and all these systems that exploit and harm people. We see all this, and then there’s something beautiful about watching Invoking Justice, because there’s one part where the men are afraid that these women will just keep going at this continuously. What instills fear is that their fighting never ends. That’s what it takes—it’s constant. I’m curious how you feel after having made these films and being politically involved for decades. What has that been like in terms of perseverance? People get burnt out, people get tired, they sort of feel like it’s hopeless. What sort of things have you learned to combat that?

I don’t know. I’ve never really thought about it like that because there are certain themes I’m engaged with anyway. I don’t have to film them, but they’re occupying me emotionally, intellectually, and politically. I don’t know about being burnt out, but with any project it has to be something I can live for two or three years, something that I’m engaged with thematically and politically. Really, the litmus test for me is, can I do something with this, which will then interrogate it in a way where I learn something new that I never suspected? Does a project have the potential to do that? If I look at Something Like a War, that definitely was one of them. Have you seen that one?

Yeah. I like when you insert the animation—the stock footage of the tomato in a jar.

You know, that tomato ad won Best Advertisement of the Year (laughter). But to me, that tells you what the elite, middle and upper class Indians think. They think that the poor are responsible for their own poverty by breeding irresponsibly. Why would they give that a prize? I mean, it is a disgusting ad. Firstly, how can you think of women’s uteruses as tomatoes? How can you think of people as them? It’s just so disgusting. That’s what I mean. That film was shocking because, at the time, population control and the family planning program was a sacred cow. Nobody could challenge it.

I entered it in this film festival in 1991, and that’s a really funny story because the main prize was, I think, 250,000 rupees. There was a special prize for the best film on family planning, which was 500,000 rupees. All this money. And Mani Kaul told me, “Deepa, this is a sure shot. You’re going to get this.” I said, “Why?” He said, “Because there’s no other film in the category, they have to give it to you! There’s no other film!” And I started laughing. I said, “You’ve got another thing coming if you think this film is going to win anything.” I knew that it was going to create furor. And would you believe it? They withdrew the prize. And from the stage, the presenter was some big government person, he talked about how dangerous it was that these anti-national films were being made. He was saying, “The poor have to control their fertility because development is being held back” and blah, blah, blah. You can imagine.

There was also The Legacy of Malthus (1994), which is really about how persistent [Thomas Robert Malthus’] thinking is and what an apologist he is for the Industrial Revolution in Britain. It’s such a dangerous ideology, to not to look at the structure of poverty and to declare people as surplus. This is basically Matthews’s false hypothesis, which leads to the false solution, which is that you have to get rid of the poor. I think every film has to have that for me: To think, okay, so can this be an intervention in debates in the country? I don’t feel burnt out yet, but it’s getting harder. I think it’s getting harder to do political work now.

Your film We Have Not Come Here to Die (2018)—

You watched it?!

I also saw that, yeah.

How did you watch all these?

They were online somewhere so I ended up watching them.

Wow, okay.

So it’s funny that you mentioned Samskara and then we were talking about caste discrimination. I’m curious now, thinking back to when you first saw Samskara in 1970, and then you made We Have Not Come Here To Die literally 50 years later, what changes do you think you have seen when you reflect on Samskara and then having made this film?

So Samskara is a very different kind of film because it’s about exposing the hypocrisy of this Brahmin community in this village. It’s not looking at daily assertions of rights, but it’s a film that exposes the caste hypocrisy of Brahmins. I have done a lot of work on caste. I mean, you’re a high school teacher. I’ve done a lot of work on preparing material for our government schools—what you call public schools is our government schools. I’ve done a lot of work with primary school teachers in the state, and we produced a set of nine films to help the 140,000 teachers, to help them really interrogate why Dalit students, minority students, and tribal students drop out. What is the dropout rate? Why? We’re looking at structural things. We’re also looking in the classroom. What kind of discrimination? Why are they fearful? Why are they so uncomfortable? These spaces are not welcoming.

Then you have to look at the curriculum. You have to look at pedagogy. So we did a whole set: we did nine films and caste was across all of that. And then I did a set of films on teaching history, again for government schools. I can send you a link to one short film from that. Actually, we’re really not teaching history, we were teaching historiography. I worked with children in a remote village for almost three months and we created activities for them to experience what historians do. Everything from how to make an assumption, to how to defend an assumption, to how to test it, how to do oral history, triangulation. I mean, there are so many principles that we taught children without reading and writing, in an oral history kind of context. I’ve been involved with caste since the ’90s in one way or the other, and much of my work has a lot to do with materials for teachers and materials for students.

I think We Have Not Come Here To Die was my first time dealing with higher education, not primary education. And what you see there is really a different Dalit assertion. You’re looking at students who have come in on affirmative action, who have mobilized politically, who are brilliant scholars. Everything they say is just fantastic in that film. So I’m looking at a very different trajectory. When you look at Dalit literacy in our country, it’s not even 80 years old. Would you believe it? It’s 80 to maybe 100 years old, but maybe not even that. I’ll send you a note, if you like, about the many things I’ve done with caste. And I’ll send you this little film, where we use devotional poetry written in the 11th century, and students have to deconstruct text and use it as evidence to understand the kind of political climate and what was happening. It’s a fun film, and you’ll see an approach which is very Socratic. You know, a teacher never corrected a student. They were free to answer anything and go on for as long as they wanted. We were always guided by their curiosity, and we would design the next activity based on that curiosity. Now, what you see in the film is an edited class sequence that other teachers can use as a classroom primer, but we didn’t shoot it that way. We shot it free-flowing, but we edited it like a classroom lesson so it could be easier for other teachers. And actually, these films have been taken up by four different states in the country as training material.

I love hearing this stuff as a teacher because I am always trying to push back against things that the administrators want us to do, which are always so punitive, so conservative, always so restrictive to creativity and curiosity. You made films after Yugantar of course, and Kya Hua Is Shahar Ko? (aka What Has Happened to This City?) (1986) was only a few years after. What was it like to be in Yugantar? What did you, Abha, Meera, Navroze all individually bring? And what was the transition like to go off and make your own films?

Abha, being an activist, brought a lot to it. Plus she had a social work background. She had worked with communities so she brought a lot through her work experience and her understanding. Abha was fantastic in terms of perspective, understanding, and also as an activist. She was very sharp in terms of picking out, politically, what’s exciting and new. The other thing is that she had a lot of connections, she had the most connections with networks, other organizations, political groups, etc. That was huge. I think for me it was… what did I bring to the group… I don’t know (laughter). My own curiosity. I mean, it’s hard to tell. In many ways it was in conversations with Abha, but I would definitely say that I relied on her a lot for understanding. I think Meera in a sense, though she was part of it, she would do more of the administrative stuff rather than come out to the field. But Navroze of course was our film person. We would have been nowhere without him. He’d say, “You have to shoot these next three shots, otherwise you won’t be able to edit the sequence. You just can’t do it.” (laughter). Of course, he has a fantastic eye, he’s a great cinematographer. So the look of the films and the framing is very much him.

When Yugantar dissolved it was very amicable. Abha wanted to become a full time activist and, as I said, she went off to start these two organizations. Meera wanted to be a writer, and she was moving to the US. Navroze and I just decided to make more films. That sense of a group, that camaraderie, of bouncing off ideas, the excitement of new things to do… you miss that. You miss it. But I feel one has to move and find ways to figure out that kind of support you need as you’re working. Abha was very important in Something Like A War. She was very much part of that film as a researcher. She was there at the workshop.

I have to say that personally, I have a couple of friends who are very close. I call them my “wailing wall.” (laughter). I have two or three friends—poor things. As soon as I start something and until it ends, I’ll be badgering them or showing them cuts or talking about stuff. So I think this idea that I need a community, some people I trust, that’s been there throughout. It’s been great to have that.

You call them your “wailing wall”?

Yeah. Because I moan on, you know (laughter). “I don’t know what to do!” “I’m so stuck!” “It’s not happening!” “I can’t think my way through this!” They’re used to it.

How did the exhibition in Berlin go? I know that along with the short films, there were conversations and other things happening.

I think it went well. They got some positive responses. I think it must have gone well, right? I mean, one never knows. Firstly, I’m just shocked because these films are so old. It’s from a different time. I’m just amazed that anybody would come out.

But I’ll tell you, what I get very excited about is that we did a Kannada version, the language of the state that I live in. We did a dub of all the films and we had these fantastic screenings in India. And the way we planned it is that, I was very keen that the younger generation of students should watch it. But we needed a way to compress time—why would they care about something that happened in the ’80s? We didn’t do a typical screening, like a Q&A with filmmakers. What we did was invite members of the domestic workers union here, and the tobacco workers union, and survivors of domestic violence. We invited them to watch the films with the students and respond to the films. What has changed? What has not changed? What is happening today?

Presenting the films to young people today, I think this worked spectacularly because they could immediately bring it into the present, especially in terms of saying what’s not changed, and what they’re dealing with. At that time, the only domestic workers union in the country was in Pune. Now we actually have a National Federation of Domestic Workers Unions in many states. This was just fantastic for me, and we did this in about four universities. This was just before I went to Berlin—so, very recently. And now, in fact, I’ve got a lot of offers, people are requesting the films. They want to stream them with different communities. So they are on the move today. By the way, what did you think about We Have Not Come Here To Die? It’s a very different film for me.

It was unexpected, but I thought it still worked well. There’s just always this political undercurrent, this charge, to your films. It’s funny that you say it’s so different because in a way, it is, but it also makes so much sense in the context of your filmography. I think it has some of your best camerawork.

It’s the only one I did without research, without preparation. I was just so affected by [Rohith Vemula’s] letter. We just landed on campus four days after his death, and he was just there. The whole film was very difficult for me because I was always shooting public events where there are a hundred other cameras. It’s a very different landscape now, because there are a hundred cameras shooting in the same place. I try to make intimate films. I really try to make the audience fall in love with my subjects the way I love them. This film was so hard because all the time you’re running, you’re chasing an event, you’re always outside. I was so diffident about it because, you know, is this going to work? Everybody’s seen all this footage on Facebook before. They’ve seen it on TV. It’s all very familiar. And what are you doing that’s different?

It’s interesting because it still feels different when you watch it in the context of a film. And most people, myself included, are not paying the most attention when on social media. Plus, with a film you’re editing it in a very careful, considered manner. I have to ask, is there anything that we didn’t talk about today that you feel is important to mention?

I think the only thing that I would like to say is that the intention of the Yugantar films was to return them to communities and actually hold screenings. That was as important as making them. These films are really not part of film festivals, and were not part of those typical film events. So now, actually, I am a bit surprised that they get into all these sorts of places so many years later. They’re being “discovered,” or whatever, as archival film documents that speak to a certain time both in history and in cinema. But that was not the original intention. In 1984, the films could not be even screened anymore because they were so damaged—they disappeared. In a lot of typical film circles, film students had never seen them. There were hundreds of screenings of those films in every kind of situation, whether it’s in a community hall, on a street, in a university, in any kind of location. There was this idea with the films that you had to have a loop: they get made, they get shown, and then we learn from that and move on.

More information about Yugantar can be found on their website. A selection of Yugantar and Deepa Dhanraj’s films can be found on the Criterion Channel.

The Yugantar Collective’s Short Films: A Review and Convention

By Zachary Goldkind

What are the different forms through which a political filmmaking can actualize? This question will naturally be followed with manifold answers, often through the conciliation of our bifurcated medium within which is enshrined two poles of representation: content (aka subject, text, or diegesis) and form (aka image, image syntax, or simply syntax [within proper context]). To proffer an image (or form) that might help appraise this conceit, it might be arguably important to discern a spectrum for political filmmaking, which I believe can see each end of the gamut as being defined via Godard’s always pertinent quote, “The problem is not to make political films, but to make films politically.” My assessment of this sentiment positions those films whose content is of a political nature on one side of the spectrum, while then placing those films that are made politically on the other. Therein, on one end exists the immediacy of political representation, whilst on the other occurs a semiotic configuration, where the politic struggles as expression rather than being that which is expressed. Godard seems to connote a qualified substance onto the latter over the former, which, while perhaps reductive towards procedures of interpretation and their capacity for reason, is frankly something I would agree with in general. For cinema, as I perceive it in 2023, through the knowledge and experience I have accumulated in my years, has been so tightly reified as a system of information, such that our only route forward towards a new and necessarily confrontational political filmmaking is through the marriage of pedagogical aims and formal ingenuity, whether such syntactical play be through radical methods of abstraction, attention, or dialectical inquiry.

I want to assure the reader that the following discussion of four distinct, provocative political short works will not be arbitrarily and needlessly assigned position on this spectrum we have outlined above. Instead, I wish to understand this spectrum as a point of debate through which we can perceive the creation of future political works, a tool for both contention and criticality. I extrapolate from Godard’s quote a sine qua non, one which yearns for a reconsidering of both the manners through which and the types of works we make. I’d posit, with this consideration, that Godard suggests, then, an intent of futurity. And futurity, should I attempt to organize its signification, offers spectators either explicit or implicit agitation, seeking response beyond normative inter-passive, spectator-image relations. How that futurity might come about, however, must be dictated by each distinct work, articulated, ideally, in a fashion that not only explicates this desire towards something else, but enunciates that through a formal intervention that troubles any affair with immediacy. In the early 1980s, a film collective in India—founded by filmmaker Deepa Dhanraj, teacher Abha Bhaiya, social-management advocator Meera Rao, and cinematographer Navroze Contractor—sought to incisively puncture interlacing spheres of patriarchal exploitation through a political filmmaking that offered futurity in diverse and increasingly complex manners. Working through the Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Telangana states, as well as just outside of northern India, at the foot of the Himalayas, the collective produced four half-hour short films, each marking a clear evolution in cinematic thought, deftly integrating progressive faculties of representation into successive developments of ideological deployment through an advancing formal consideration.

Molkarin (1981), or Maid Servant, is Yugantar’s first film, a work of majority didactic construction, wherein we gain insight into the dynamics of exploitation as they regard women domestic laborers in Pune, Maharashtra. What the film observes is a reenactment of the processes a part of unionization, communicating systemics, and the sundry of employments through which oppression is enacted. Ranging from tactics of isolationism—so as to, par example, contextualize any individualizing request by an employee as antagonistic and therefore grounds for firing—to the very faculty of calcifying class segregation, wherein domestic workers’ children are expected to supplement their parents labor. What is ensured we bare witness to is this undertaking of socialization, prescribing class position onto laborers and their kin as to inscribe the stagnation of mobility. One of the more egregious exploitations, of many, briefly touched upon is the anecdote of a women forced to find her own replacement, but through familiar manners describable simply as outsourcing. The replacement shan’t make wages, but instead the domestic worker in question is required to compensate this substitute herself. Beautifully accomplished through this display of malpractices is the opportunity taken to represent situations wherein these workers discuss amongst themselves, in a diegesis of the work environment, the dehumanization felt at every turn. This oppressive space is churned into one that can, in fact, be punctured. We are offered this image and this image reverberates through the short film, through a means of actualizing and towards an end of autonomy.

The formal aptitude of Molkarin leaves one, however, yearning for a greater enunciation, which is undoubtedly present yet sparse. A quick montage sees a slew of domestic workers collectively leaving their work, striking in support of another laborer. With each cut, this group of women emerging from the opacity of these houses grows and grows. They gather until the street floods in a wave of their resistance. Provocative, certainly, but the film gets caught in its utility as a testimonial: experiences explicated and ideologies collectively formed and debated towards a unity that proffers support for all domestic workers. The structuring is rather inconsistent and doesn’t leave much room for dialectics, yet what is clear is that the film’s intention seems more bent on cultivating incitement towards the proclamation for futurity. The penultimate scene of the film is a congregation: women answering questions that inquire so as to formulate what the next decisions, demands, and movements must be. A programmatic unity, essentially, must be organized. To conclude the film, a young child actualizes the desires of these women, confronting, in a fiction, her employer. The Pune City Domestic Workers Association ultimately mandated seven points to confront labor exploitation: (I) Wage increases based on work, (II) Two holidays per month, (III) No pay cuts due to absence caused by illness, (IV) Employer’s family leaving for vacation shall not result in pay cuts, (V) One month’s salary as bonus on an annual basis, (VI) Employers cannot behave with discriminatory or humiliating attitudes, and (VII) Workers leave is to be granted on important festivals/holidays without a pay cut. The action to follow would be discerned in films to follow.

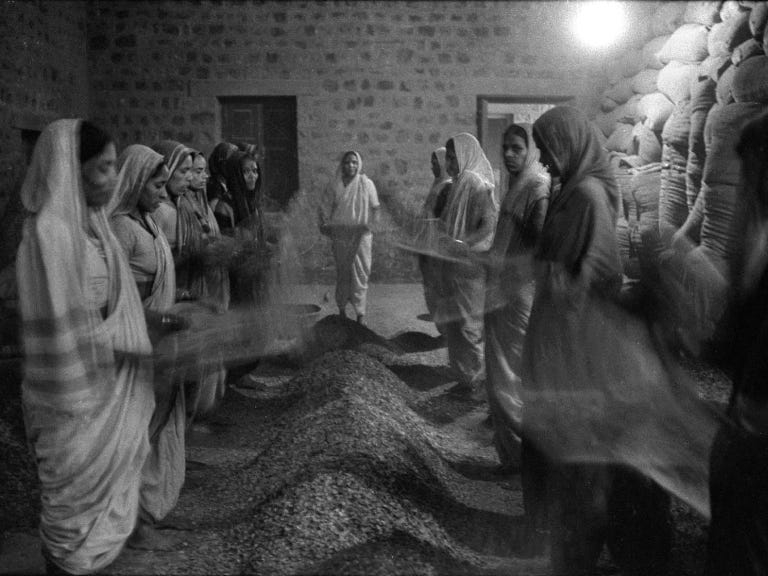

Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali, or Tobacco Embers, is the second work of the collective and most closely aligned with Molkarin as it regards textual objectives and representations. However, there is a more narrativizing construction here, which comes to allow for a troubling of linearity and logics. To put my perspective forward, this is the strongest of the four shorts, deeply specific in its gaze on textures and how the romantics of an image can be usurped alongside the illusion they represent. The film opens on the packing of meals, women in their homes collecting food into mobile receptacles. As these women begin to gather on the street, we see them unpack the food and eat together en route to the tobacco factory in Nipani for the day shift. There is a conscious aestheticism to both this sequence building and the film’s compositional rigor when framing the factory labor. We are opened up to contradiction, to a distanced ogle perceiving a classical allure in the arrangement of the work as seen, which must therein be reconciled with. Voiceover is employed to unveil this beauty, disclosing the rot acting as substrata to the working conditions: anecdotes of sexual violence, the physical and emotional revoking of autonomy, the impossible pay, the absence of time in and of itself. More militant than Molkarin, Tambaku Chaakila Oob Ali offers unabated collectivist sentiment, positioning the film very pointedly within a subjectivity of the organized worker as it breaks through any beautifying projection, galvanizing the zeal and rage seething in its subjects with which to impale that isolationism the managerial class orchestrates. “Long live the union! The union will be victorious!” “If one woman is afraid, another woman should give her courage!” What this short does brilliantly is almost a cartographic exercise, constructing a narrativity that bursts from the oppressive normalizations and then eschews totally those perspectives of the exploiter, observing the material shifts in response to organization. This tobacco factory becomes worker led, where that violent managerial class is suppressed and their administrative powers are given strict limitations amongst their insular bureaucracies, the workers now leading themselves.

This almost idealistic portrait forward is then stopped in its tracks, invoking the political discourses of Third Cinema and a particular form of montage that recalls Eisentein’s theories, wherein dialectics are formed not through narrativizing structures and linear organizations of images, but through the stark corroboration of sequences, representation upholding—yet increasingly complicating—the ideology of images prior. Concluding the aforementioned idealism is a union meeting, where discourse, in its problematizing of programmatic unity, is allowed to be witnessed and these difficulties in heterogeneity as expression of a single movement is given the space be reckoned with. No conclusions are drawn. Unlike the empowered futurity of Molkarin, Tambaku Chaakila Ooh Ali’s future is that of requisite contention. We are confronted here, out of necessity to both recognize and give representation to (through ideological inquiry in manners both formal and textual) these compounds of contesting perspective that must make up a revolutionary, union-minded movement.

Shifting their praxis, the Yugantar’s third film is a fiction: the narrative of a young student and housewife named Lalita who’s life and studies are subsumed and sublimated by her husband, his increasing dependency on patriarchal allowances, and his family’s exploits in their utilization of these oppressive systemics. Our protagonist becomes enslaved to a socializing that positions her as maid, as dependent, as destitute. The script devises a melodrama, wherein each ellipsis is a signifier to swollen disenfranchisement. It is crafted of many discussions, in collaboration with feminist activist collective Stree Shakti Sanghatana, wherein a careful curation of an overabundance in individual stories allows for Lalita to exist as improvised analogue to these many lives volunteered as textual basis for the film. What complicates this melodrama and enables the work to enliven itself to a degree rarely seen through short-form fiction filmmaking is the additive layer of aesthetic intervention through the diary film. The transference of voiceover tactics utilized as subterfuge in the prior documentary-minded projects, here enshrines a perspicacity, both sociological and emotional. These voiceovers will cultivate this character—and us spectators, as tied to her logic through various narrative stratagems—towards a need for emancipation, the very question begged and the very futurity sought by means of this work. The film is entitled Idhi Katha Matramena (1983), or Is This Just a Story? Naturally, the title urges us towards active viewership, wherein the semiotics in play become an ethical labyrinth through which we must traverse.

Most exciting in this fictive context is the capacity the collective has to construct a formalist rigor around the narrative, a structure of perception and subjectivity that might more pronounce the psychologically affective means of a character, in contrast to the prior documentaries’ capacities. This assumption of forms manifests wholly in a very bare, intimate survey consuming our protagonist piece by piece. A lack of score underlines the solitary when voiceover is left aside, and the tears that are shed at the sight of a newborn daughter opens space to consider how even her children are churned into objects of appeasement: a son would make her husband proud, a daughter only perceived as an increased burden. This consistent utility and configuration of Kuleshov technique is finally imploded in the final minutes: a long, static shot bares the fatigue and dissociation of Lalita, wrought through these many years so suddenly gone by. Her face is stoic upon immediate glance but, under the weight of this narrative, we know it to be caked in turmoil. And then a free roaming camera is cut to, sauntering through her home and observing all the textures and objects that enclose her: besieged is she by a collection of memories haunting tangible artifacts, upon which her labor has been imprinted. But Yugantar cannot end so cynically, and we reconvene with their plight towards material change as Lalita speaks with a friend. That friendship motivates her to leave and seek agency elsewhere, rejecting the oppression, incepting the need to ask what comes next, and what, particularly, that might look like. These kinds of images are left to those spectators reckoning with the project, existing in the positionality of Lalita’s struggle, finding resonance in her strident rejection of these many years caught in exploitation. Yugantar’s films and mandate, which I find most pronounced through this work—their most renowned and travelling project—is the very function of their community based collaboration and screening process, provoking a community confrontation with these subjects, forcing questions out into open discourse. Idhi Katha Matramena is an instigation, an act of invoking the imagination to seek progression.

Lastly, Yugantar’s fourth and final work is also perhaps their most nebulous. Sudesha (1983) tells the story of its eponymous protagonist, a rural village inhabitant on the foothills of the Himalayas, whose community is placed at great risk as industrial deforestation threatens the ecology that has sustained their livelihood. Both men and boys are forced to migrate through India looking for work, and the women are left to maintain the homestead. These women organize to make up a majority of the Chipko ecological movement, seeking to protect their regional environments against thÿe government-backed razing. Seeking a semblance of agency—which is naturally the thread that links not only each of these four works textually, but also their very production impetus—the community gathers to protest. In contrast to the faculties of the prior shorts, this work seems more attentive to community machinations—as opposed to utilizing an institution as the centrifuge—but siphoned through the perspective of our protagonist. Her voice overs offer peripheral contexts onto the film’s languishing formal attire. Observational documentary filmmaking is the schema this project is built upon, however its relationship to a specific cultural display gives the film an ethnographic tinge, unexpected and not entirely reconciled with through the runtime. We are narrativized through the affairs of Sudesha, yet those extrapolations of individual politic are projected onto the community writ large, culminating in a form that is quite aesthetically discursive. Even Idhi Katha Matramena operates on a distance that, in its fictive intrigues, still manages to remain as intimate to its broader ideological intentions as the first two documentaries are. The discursion present here amplifies a distance that reads more in tune with estrangement, which, to my estimation, is owed to both these observatory, ethnographic sensibilities, alongside this focal role of a historied individual acting as our entryway onto a people in the midst of action. Regardless, there remains the capacity to activate, for Sudesha’s voiceover provides the messiness of contradiction: it inevitably troubles the haphazard, historically colonial gaze, yet simultaneously reaffirms this act of projection onto her surrounding community. This incommensurable facet is ultimately why I’m persistently at arm’s length from this work. Regardless, Yugantar reconvenes with their praxis in a concluding sentiment, one which is certifiably an echo that stems back from Molkarin, as Sudesha herself affirms, “If we’re all here together, why should you be afraid?” A totalizing sentiment and ideological position if there ever was one through these four films.

Yugantar’s work explicates a methodology for political filmmaking, one which confronts the problematizing faculties of cinema as a tool for ideological inquiry and representational affect. Through multilingual formal aptitude, their approach towards a politic of activation can only go so far through the film in and of itself. Their exhibition methods, as touched on briefly above, showcase that a political filmmaking must also organize beyond aesthetic orientation, though that should not diminish the ultimate value that these innately artificial aspects must uphold. The collective’s community based screening, ensuring discourse is part and parcel both within and without the object of the film, is that very activating facet necessary in conditioning one’s relationship to a political film. The formalization of festivals, for example, has neutered the capacity for political engagement in purportedly political filmmaking, and it will be through examples set by films and filmmakers, such as those spoken of in this short essay, where incisive and demanded squaring might be able to take place. A spectrum of film aesthetics must find a sphere wherein debate on utility and function can take place. A political filmmaking, if seen through the eyes of Yugantar, cannot simply stop with the film, but certainly cannot simply stop or start through the act of a single filmmaker, themselves. If there’s one takeaway these shorts and their histories have given me, it’s a push to find those ideological minded filmmakers, similarly crushed by professionalized circuitry and industrialization, with whom we might seek that same futurity these films proffer.

Thank you for reading the 31st issue of Film Show. Keep on fighting, together.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.