Film Show 028: First Look 2023, Part One

Reviews of 13 films from Museum of the Moving Image's First Look festival, including works by Ewelina Rosinska, Emily Chao, Alassane Diago, Gerard Ortín, Sophy Romvari, and Kurt Walker

First Look is Museum of the Moving Image’s annual showcase for “adventurous new cinema.” The programs have historically shed light on some of the most exciting new voices in film, and this year proved the same with featuring works by folks who deserve to be heralded as major voices in the avant-garde and beyond. This year, the festival ran from March 15th to 19th, and films are also again throughout this weekend. Below, find reviews of 13 different films that screened at the 2023 edition of MoMI’s First Look.

Earth in the Mouth / Ashes by Name is Man (Ewelina Rosinska, 2020 / 2023)

Earth in the Mouth (2020) and Ashes by Name is Man (2023) are diary films which transcend the autobiographical nature of the form. Ewelina Rosińska’s films, both receiving their North American premiere this month, are built from elements which individually have an intimate and observational character: the interactions of friends and family, church services, travel, a gravestone sharing the artist’s last name. But Rosińska arranges her material more in the manner of musical forms than of narrative, crafting rich but ambiguous layers of meaning from their harmonies and dissonances. She invites the audience to engage with that meaning actively and critically rather than to share in a lived history.

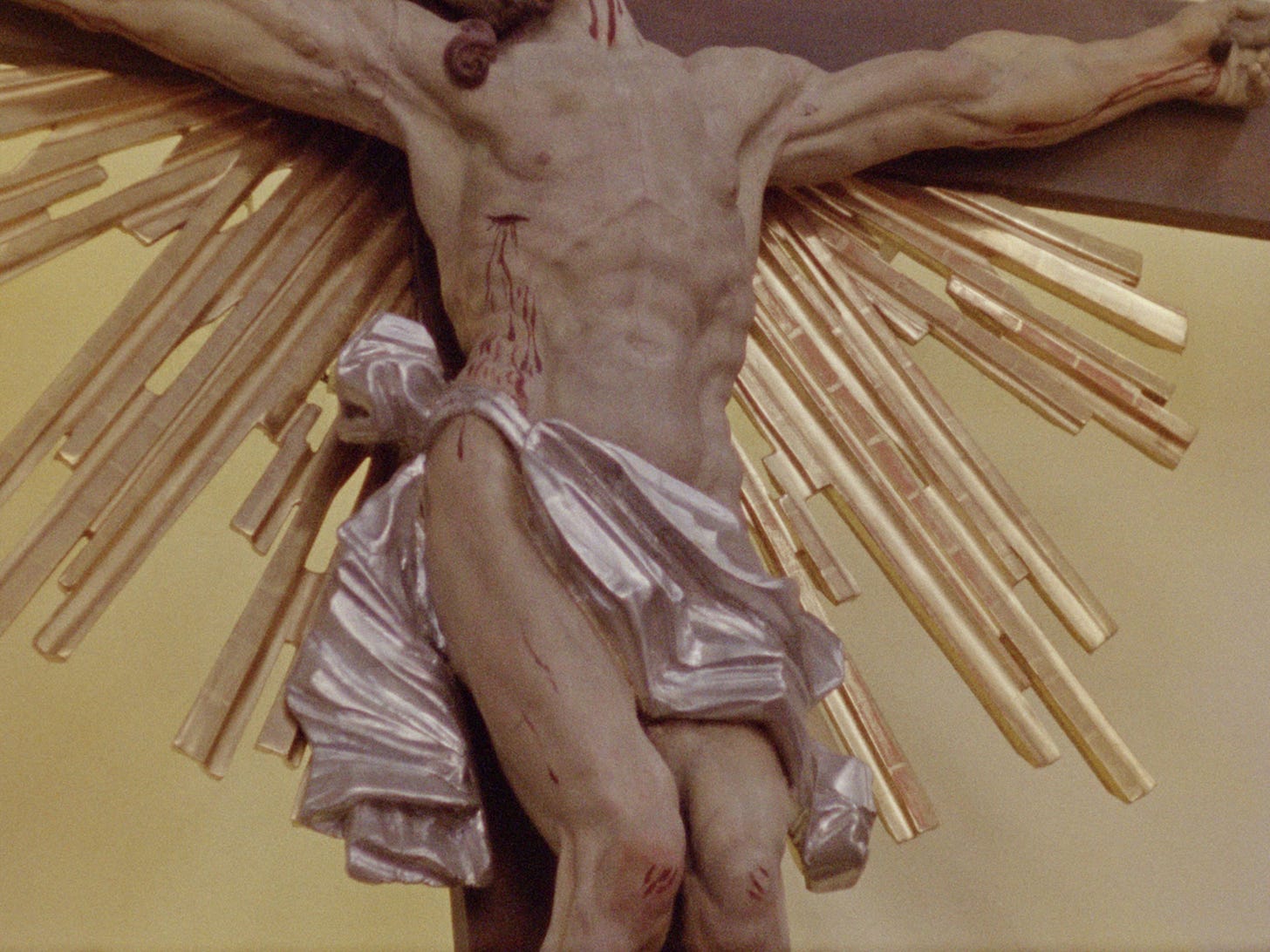

The films are musical in more than just the metaphorical sense. Sound is key to their confident rhythm and formal cohesion. A piece of audio will last through a number of cuts, tying a sequence together and shaping its inflection. In Earth in the Mouth, sound and image have a contrapuntal relationship which is largely syncopated but allows for added emphasis when they sync up. Frequent changes in the source and character of the sound create a soundscape on equal footing with the photography. Sometimes the music is diegetic, as when a choral piece begins and a few shots later the film cuts to the choir singing it, but other times the sound is independent from the images, or even sharply contrasts it, as when a synthy new-wave song plays while the camera shows an organist playing for a church service. In one stunning sequence, the film goes completely silent while a rock band is shown rehearsing.

If Earth in the Mouth is something like an intricate baroque suite, Ashes by Name is Man is closer to a mass: solemn and contemplative. Its rhythms are much slower, its editing less circumspect, and while it employs several pieces of sacred music, its sound relies more on natural soundscapes than on a score. Despite these differences, the two films are of a piece in their search for the symbolic threads connecting spiritual life, personal relationships, politics, and the land. Ashes connects Catholic iconography with the Polish landscape, the artist’s grandparents with the ceremonies and architecture of the church; Earth contains multiple sequences that cut between the root systems of trees or collections of seashells and the singing of church choirs or the raising of a flag, and switches deftly between these sequences and scenes of friends and family enjoying casual moments at home or on the lakefront. Both films use visual motifs of fruit, birds, books, and cemeteries to represent cycles of life and culture as connected to the land.

Rosińska’s films eschew clarity of detail in favor of more universal ideas, but in a certain way it feels as though we get to know the artist better for it. We don’t learn about the facts of her life and relationships in the way we would in a Jonas Mekas-style diary film, but instead see the aesthetic and intellectual concerns that preoccupy her mind and structure her practice. Toward the end of Earth in the Mouth, we’re shown a page of a critical theory book with an underlined passage that reads, “Autonomy is an ideal which capitalist society itself brings forth but which cannot be realized under it. The autonomy of the individual is a necessary illusion of the capitalist mode of production…” This passage resonates with Rosińska’s approach in these films: to understand other people, we must understand the physical and social landscape which produced them and continues to reproduce them. —Alex Fields

Light Signal (Emily Chao, 2022)

Emily Chao’s Light Signal opens with a visualized excerpt of the US Coast Guard’s Light List. The Bay Area filmmaker reads descriptions of different rhythms of light—“fixed,” “occulting,” and “isophase”—followed by a visual representation in black-and-white 16mm film leader. Chao then cuts to a landscape: a lighthouse on the California coastline. As the film focuses on the lighthouse and its mechanics, we attempt to make a connection to the earlier glossary, but none of the descriptions match. With a return to the framework of the black-and-white leader, Chao confirms that we lacked the language for the rhythm that the lighthouse would produce. As the demonstration continues, the white frames are replaced with images of a prison interior.

At three points, Chao introduces text into Light Signal. With this poetic language, which is projected one line at a time on roughly hand-processed film, she unsettles the clarity of the scenes on either side of each interjection. Sourced from the 19th century keeper’s logs of Emily Fish, Chao’s fragmented selections create an uncanny space between objective analysis and gothic dread. After a Benning-esque “utopian vision” of an Indigenous cabin in the Sue-meg State Park, she provides the definition from the Light List that was previously missing: “flashing.” For all the ways in which she obfuscates images and ideas, there is still a simplicity and immediacy to the capturing of light on film that cuts through.

In the most accomplished and elaborate film of her career so far, Chao effortlessly wields the disconnect between language, image, and structure. Each of the individual parts—the structural light list, the landscape images, the poetic intertitles—stand alone as common modes of 16mm avant-garde filmmaking (Frampton, Hutton, Gatten), but at a little over 11 minutes, Chao uses them all cumulatively in a complex consideration of the land on which she is working. —Douglas Dixon-Barker

Growing Up Absurd (Ben Balcom & Julie Niemi, 2023)

Ben Balcom and Jule Niemi’s Growing Up Absurd traces the formation and dissolution of Tolstoy College, an “anarchist educational community active at the University at Buffalo between 1969 and 1985.” The movie opens with the aforementioned quote, given to the viewer through what appears to be a scribbled-on and scanned, off-center pink document. These title cards appear frequently through Growing Up Absurd, lending the film a sense of being an archivist’s work. Notably, the heavy saturation and choice to shoot the film on 16mm causes the experience to feel like excavating a lost memory. That Balcom and Niemi don’t show any individuals throughout the film evokes the sense of a certain presence having eroded with time.

Growing Up Absurd moves between four different interviews with ex-faculty members as they discuss their memories of Tolstoy College and its radical approach to education. Underneath these interviews we’re shown images of the University at Buffalo today: broken window blinds, smudged chalkboards, vacant and dirty classrooms. It’s tempting to read this as purely cynical, since the film makes clear Tolstoy College was defunded due to internal politics at the University. But Growing Up Absurd’s visual aesthetic makes it difficult to interpret the recorded footage as “modern.” The resulting film feels instead as if it’s permanently in stasis, frozen at the end point of Tolstoy College’s long battle against defunding. Through this framing, Tolstoy College isn’t permanently closed as it is in real life, but instead laid dormant, waiting to be woken up.

Towards the end of Growing Up Absurd, we’re shown a view of classrooms from afar, all illuminated in the dark by lights—it’s as if students are inside. Shortly after, the film cuts to a rebellious graffiti tag that reads “reconstitute the university so it means some-thing & benefits the people.” This is rendered on the same pink background that Growing Up Absurd uses for its scanned title cards, presenting this statement as another basic historical truth. At one point in Growing Up Absurd, Balcom and Niemi show photographs of the college’s faculty and alumni alongside out-of-focus footage of the campus. These images and ideas relay a clear message: Tolstoy College was the product of extensive collaboration—it and other communities can exist independent of any physical buildings, and be recreated at any time. —Jai Singh Bains

Rodeo (Lola Quivoron, 2022)

The bike is freedom and the bike is love. It brings us to work (the good and the bad kind.) It’s easy, a nightmare, a slide—it machinates our understanding of how the world runs, of how it might and should run. There’s a whole cinema of associations to the motorbike in motion, a network of overlapping romances and crashes that emerge in Lola Quivoron’s Coup de Coeur prize-winner Rodeo. Julia (Julie Ledru)—or maybe her name really is Unknown, as she’s called frequently—is a drifter whose main gig is lifting expensive motorbikes from well-off men. She answers their classifieds, gussies and smiles just enough to get on the bike they’re selling, and peels off, throwing middle-finger skids behind her. She falls in with a bike gang (the first of the film’s surrogate family units) that uses and shelters her in equal measure. One of their members, Abra (Dave Nsaman Okebwan), extends her a modicum of kindness and is summarily and narratively sentenced to a horrific collision. His violent absence and ghostly presence (the first of the film’s speculatively spectral moments) haunts Julie and informs the film’s deeply-felt sense of just-submerged longing. How do you turn driving away to driving towards something?

Despite the racial and class conscious comradery of the motorbike collective—the gang is a reaction to living alienated from any kind of nuclear mainstream dream—sequences of its male members mirror the hyper-masculine excitements of another petro-gender vision, Julia Ducournau’s Titane (2021). As in Titane, a woman at the center of a volatile community here seems to be the only one who knows that desire can be both predatory and joyous. But Quivoron’s film is less interested in Ducournau’s speculative instigations of gender, and for that reason it may exist in less danger of collapsing its possibilities. During a fireside rave soundtracked by XXXTentacion’s “Look at Me!”, Julie/Unknown loses her body and guard in a close-up sequence that mirrors the way Quivoron shoots her when she’s riding her motorbike. The motorbike is a body, and vice versa; the freedom to move about freely in desire and in actual, not manufactured, workday communion is all there is. Rodeo is by turns anxious about the possibility of forging connections in a world that alienates us, and romantic about the certainty that holding someone’s waist is exactly the kind of path worth driving down. And is the film’s enigmatic ending sad, a fire turning to ember? I am not sure. But it is a ghost story. —Frank Falisi

The River is Not a Border (Alassane Diago, 2022)

Alassane Diago’s third feature The River is Not a Border interrogates the long shadow of national trauma surrounding Senegal and Mauritania with patience and empathy. Diago centers the film on the Black Mauritanians who were victims of mass displacement during the Senegal-Mauritania border war of 1989-1991, gathering his family members on the banks of the Senegal River to attest to what they saw and did. As past terrors resurface in discussions, Diago’s unadorned directorial style captures his relatives’ faces as they mourn, talk, and listen. Diago records everything faithfully: there is indignant yelling about bringing the truth of Mauritania’s cruelty to its Black population, and a moment where a woman is reduced to tears during silent prayer—she looks past the river to her homeland on the other side.

Despair weighs heavily on the speakers, but Diago juxtaposes grief with declarations on the importance of truth. The fraught history between the ethnic groups inhabiting the neighboring regions is uncovered through the open dialogue that he encourages, and through his tight framing, we see the different sides of his family come to terms with the brutality of the border war. Eventually, they pledge to get rid of their preconceived notions of the past. Diago’s workmanlike style foregrounds the conversations between his relatives, and he refuses to distract the viewer with any flashy editing tricks. Much like his encouragement for these people to speak candidly in their confronting of unspeakable horrors, Diago asks the viewer to hear their stories without any extraneous imagery or detail. —Ryan Waller

Agrilogistics (Gerard Ortín, 2022)

The opening sequence of Agrilogistics shows an agricultural industry automated to the point that human involvement is limited to oiling machines and checking their work for minor errors. Symmetrically framed robotic arms sort bulbs and leaves in a ballet agricole reminiscent of silent-era experimental modernist works like Steiner’s Mechanical Principles. AI-driven carts inspect and pack tomatoes which are shipped off in crates, and we begin to wonder if there are humans left to purchase and consume them or if we’re witnessing a desolate future world where machines go through mechanical motions purely to execute their programming.

At its halfway point, the film switches from this diurnal dystopia to the purple haze of a greenhouse. Industrial precision gives way to nocturnal fantasy. A llama cautiously leads a group of animals into this strange and artificial world in what seems to be a jailbreak. Can they reestablish a livable harmony in this manufactured environment?

Agrilogistics uses these curious contrasts to speak to the tension between the enrapturing beauty of capitalist modernity in its idealized technological form and the monstrous alienation of human and animal life from the natural environment by those same processes. The film ends with a sequence that implicates film itself as a technology, staging the industrial facility as a film set capturing images not for human enjoyment but for the use of AI. The shutter-like sounds of a spinning machine form a lifeless beat and the film ends with another startling contrast as a remix of a Lilly Woods song begins to play over it. “Our world is slowly dying,” she sings, bluntly clarifying any ambiguity about the film’s perspective. —Alex Fields

Gospel Hill (Kevin Jerome Everson & Claudrena N. Harold, 2022)

With well over 100 short and long form films over the last 25 years, Kevin Jerome Everson has created a constellation of vertical-slice documentaries that build a sprawling and ever-surprising portrait of Black American life. Rarely offering commentary, his films are often simple in form, providing a direct view of a single scene before moving on. Since 2014, Everson has had an ongoing collaboration with his University of Virginia colleague Claudrena N. Harold. Their films made together stand out in Everson’s filmography; while generally pulling from less experimental forms of filmmaking, they all orbit around the Black history of the directors’ shared institution. Sugarcoated Arsenic (2014) and We Demand (2016) are filmed reenactments of important historic speeches, Black Bus Stop (2019) is an act of intervention at an iconic meeting ground, and Accidental Athlete (2022) couples Everson’s stunning black-and-white photography with Paulette Jones Morant’s voiceover—she recounts her personal experience as one of the first Black athletes at the university.

Gospel Hill continues with this unifying subject matter, but finds a new mode to work in. After a couple of short silent rushes—focus tests, flare outs—this latest collaboration settles into a scripted shot/reverse shot conversation between two University of Virginia employees. In the following four minutes, the two actors discuss their lives, labor, and the responsibility of providing for a family. The acting is natural and charming, and the film almost comes off as an insight into a different career Everson could have had. His photography is as impressive as ever, with the characters illuminated within the analogue grain of the nightclub. As the credits shout out 1973’s The Mack, we can trace a line from the way Michael Campus explored questions of labor and provision within the Blaxploitation genre to Everson’s work here within the short-form avant-garde. But while there is a clear thread running through these collaborations, they can come off as less confident films in Everson’s filmography; these more vocalized historical contexts struggle to stand above the mainstream forms they are taking, undercutting the natural minor key of his best works. —Douglas Dixon-Barker

Herbaria (Leandro Listorti, 2022)

Since 1750, about 500 species of plants have disappeared; since the early 20th century, roughly 80-90% of all silent films have been lost. Leandro Listorti’s Herbaria connects film and botany through their mutual need for preservation. It is in large part a tribute to the work of plant preservationists and film archivists, and much of its duration is content to observe these professionals at work with minimal narration. These scenes are broken up by digressions which develop how these two fields relate without ever settling on a clear thesis, unfolding as an open-ended meditation with many branches.

One of the most interesting of these is the curious intertwining of the two fields in Argentina’s history. Some of the earliest extant Argentinian films are documents of types of flowers. The gardening school of Buenos Aires is named after Cristóbal Hicken, a prominent botanist; Hicken’s nephew, Pablo, was a film collector and the namesake of the city’s Cinema Museum. Some of the country’s most prominent experimental filmmakers have been interested in botany either as a subject of their films or as a personal hobby, and both Claudio Caldini and Narcisa Hirsch make appearances here. These historical connections exemplify the importance of archives in preserving not just particular materials but a broader sense of time and cultural memory, and Herbaria itself becomes a miniature archive of important national figures and institutions.

Herbaria’s strength is in this modest and surprising reflection. The connection with botany allows for beautiful reflections on film as a living thing, of plants as cultural artifacts arranged to “announce human presence to the world.” Unfortunately, the film stumbles when it touches on broader political and philosophical questions around preservation. It raises the question of whether value is intrinsic or relational, and of who gets to decide what is valuable (without attempting an explicit answer). Much of the film could be understood as an implicit answer, but the dynamics of colonialism, race, and class are almost entirely passed over. Film has been a cultural production primarily of wealthier white people, the very land these plants are harvested from was stolen through colonization, and the institutions which preserve them today continue to be run by and for white professionals. How do we assess the value of preserving something in an archive under these political circumstances relative to the value of the land itself and the ability to access and use it?

Herbaria mentions the destructive force of climate change in passing, noting that plant archives have had unforeseen value in understanding and perhaps combating climate change, but it doesn’t delve deeply into politically charged questions of human destruction or colonial dispossession. Several sequences raise the metaphorical idea of plants and nature rising up as something monstrous to attack humanity, but they leave the meaning of this vague. Herbaria pushes far enough to broach these fraught issues but then abdicates any responsibility to deal with them; given these issues and the film’s very loose structure, it would have benefited from a clearly delineated range of both subject matter and normative questions. —Alex Fields

Silent Love (Marek Kozakiewicz, 2022)

Family is defined, with a simple search, as “a group of one or more parents and their children living together as a unit.” Despite efforts to limit ideas of family to tradition, this definition leaves room for many interpretations of the system and the expansion thereof. The subjects of Marek Kozakiewicz’s Silent Love, a documentary in the vein of direct cinema, fall well within this broader definition of family. Agnieszka, a Polish woman living in Germany, enters the adoption process when her mother dies; she is to become the legal guardian of her orphaned teenage brother Miłosz. Upon returning to Poland, her relationship with her partner Majka goes long distance, and it is soon clear that the two must hide their partnership; authorities consider homosexuality grounds to declare Agnieszka an unfit parent.

Though too much is left unsaid, the quiet but visible contrast between how Agnieszka and Majka navigate hiding their relationship is well documented. While Agnieszka hides their love out of necessity in the courtroom, more masculine Majka cannot do the same. As the latter’s visits grow more permanent, her presence puts into question whether this secret should be kept from Miłosz. Later in the film, the three are shown as a family unit; it may be unconventional for their location, but it’s natural in their dynamics. This lighter familial intimacy remains softly observational, and the film ends without any real closure on how they’ll exist; it’s not a happily-ever-after by any means.

Rather than indicate governmental homophobia with hard legislative statements, or even the casual linguistic prevalence of derogatory terms, the cultural pressure of traditional gender roles and heteronormativity is captured in Miłosz’s school. A class has him learn to dance the polonaise, a performance with strong traditions of masculine domination and feminine submission. Though he isn’t fully aware of the politics of nationalism, he is slowly indoctrinated into a hyper-conservative school and church community that don’t resemble the life he has at home.

Director Kozakiewicz shoots his debut feature like a narrative film—Silent Love could easily be mistaken for the recent strain of European arthouse drama that mistakes minimalism for artistry. Truth is easily mistaken for fiction, especially when Miłosz is shown at his most vulnerable; this captured innocence borders on ethically questionable territory. He’s young enough not to understand death—asking whether a crematorium is where they make cream—just as much as he is unaware of the heteronormativity weighing on his new family unit. Though the film is released quite a few years after it was shot to protect the family’s privacy while going through the adoption process, it’s still uncomfortable watching this kid not quite know how to grieve. While this is the sort of story that needs to be known, the child’s pressured encounters with Catholic nationalism and inability to process death are touchy subjects. I can give the filmmakers the benefit of the doubt on permission, but the boundaries are too close for comfort. —Sarah Williams

Social Skills (Henry Hills, 2021)

Consider Henry Hills’ Social Skills a spiritual successor to the director’s own SSS (1988). Choreographer David Zambrano is responsible for the kinetic movements in both works, improviser Zeena Parkins contributes to their soundtracks, and Hills employs sharp editing to highlight the frenetic nature of these two vibrant elements. In the older film, Hills featured one to three dancers onscreen at a time, allowing for a palpable link between the jaggedness of the music and each dancer’s individual movements. With Social Skills, which features footage from a 60-day workshop, there can be dozens of people in a single shot, allowing Hills to oscillate between showcasing the dancers’ thalassic movement and highlighting specific members’ actions (his frame morphs into ovals of varying sizes to do the same). The most elegant straddling of this line appears three minutes into the film, when the title card unexpectedly arrives and is immediately followed by a list of every participant; it’s a slick maneuver that contributes to the work’s overarching playfulness, while nodding to the actual people responsible for what we’re witnessing (we see their full names, but there’s so much in this giant block of text that it’s hard to take everything in).

Turntablist (and filmmaker) Christian Marclay granted the music in SSS a plunderphonics bent, so it’s only appropriate that while he doesn’t appear here, Hills utilizes a collaged musical structure to animate this work. He moves between jazz and disco, and juxtaposes cartoonish sound effects with funk snippets bearing a similarly boisterous attitude. There are easily identifiable songs too, from Eminem’s “Guilty Conscience” and Kanye West’s “See Me Now” to The Flamingos’ “I Only Have Eyes For You” and Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell’s “You’re All I Need To Get By.” The overall effect is that of spontaneity in the everyday, of newness in familiarity. “I would love that we would be able to fully speak through the body, like how we are able to speak with words,” Zambrano once said in an interview. There’s a wide range of musical genres and dance moves we see in these 13 minutes, and the constant edits to both the image and sound point to the wide range of expression our body holds. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

It’s What Each Person Needs (Sophy Romvari, 2022)

A phone rings and a stranger picks up. The two discuss terms, and agree on a social dynamic that fits both of their needs. This transaction of comfort initially gives the impression of a one-sided companionship service; subject Becca Willow Moss treats the call clinically, and her tone differs from later interactions. As the callers change—elderly women seeking someone to talk with, a man who wants to speak as equals, and others who request a song—Sophy Romvari’s It’s What Each Person Needs reveals the mutual nature of these distant social transactions.

At one point, the voice on the other end repeats, “I can’t see your face”—an aging technological error that’s visualized by a minute where Moss remains either out of focus totally, or only her hands are shown. Romvari doesn’t outwardly state what each caller wants. Instead, she uses her camera to juxtapose Moss sitting in silence when she’s supposed to be singing to the voice on the other end, or she will keep her star’s face out of focal range when the caller needs a word of comfort more than the reality of a person there with them. What each person needs differs: one woman needs reminders to stay out of the sun, as if she is a child sighing after her mother; while a man chides Moss at the beginning for what he interprets as a dominating dynamic over the phone.

Moss is never shown in clear focus when not putting on a persona until the film’s meta-closure. She listens in on a conversation asking what the film itself and the lonely calls we’ve already heard mean. This moment lays bare a question that’s been boiling under a lot of Romvari’s work, including her grief study Still Processing (2020): how do you lay claim to the personal motivation within art without that connection becoming selfish? Just as early callers state their needs, we also become aware of what we desire from a film, whether we are the ones experiencing or creating it. —Sarah Williams

I Thought the World of You (Kurt Walker, 2022)

Lewis Baloue is the enigmatic artist behind the best archival releases of the 2010s, L’Amour (1983) and Romantic Times (1985). He was a mystery to all who stumbled upon his work, and even after Light in the Attic reissued these albums and tracked him down, he shared little about his life. Kurt Walker, one of the most incisive filmmakers associated with the independent virtual studio Kinet, has always known how to depict the wide emotional landscape of the internet. One could consider his newest film I Thought the World of You a touching ode to Lewis (which is not his real name), but it is also a work testifying to the rapturous thrills of collective online discovery.

Throughout this 17-minute short film, Walker provides intertitles in the form of forum posts from the Hipinion message board. All of these revolve around Lewis: pseudonymous internet users speculate about his life, while acquaintances comment on the sort of person he was. Both types of posts only contribute to his elusiveness. I remember reading these exact messages, and the excitement that accompanied strangers’ commitment to uncovering who this person was. The joy, of course, came from not actually being able to figure everything out.

Walker’s film captures that endless intrigue through numerous silent shots depicting Lewis, though we never see the face of the actor portraying him. We do see the actual musician’s face, but it comes via photographs that had already circulated of him last decade. Walker understands that there’s no point in revealing more about him, and so he focuses on the mystique of his life and music. The film’s most moving shot finds Zachary Williams looking at a computer screen as scrolling images and text about Lewis are superimposed. The blankness of his face contrasts the vibrancy of what all this information has created. There’s beauty in how distance (spatially, temporally) conjures infinite worlds of meaning and experience: this non-knowing leads to our all-feeling. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Thank you for reading the 28th issue of Film Show. Our second look at First Look is coming soon.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.