Film Show 027: Berlin Critics' Week, 2023

Reviews of 11 films from Berlin Critics' Week, including works by Masao Adachi, Sharon Lockhart, Dominik Graf, Rubén Gámez, Stephen Sayadian, and Dominique Loreau

Each year, the Berlin Critics’ Week runs concurrently with the Berlinale. This film festival, which is smaller and features an array of films that are followed by “debates,” serves as an opportunity to think more critically about film as a medium, its politics, and more. This year it ran from February 15th to 23rd, and there were new features from longtime directors (Masao Adachi, Dominik Graf), works by promising newcomers (Ariadine Zampaulo, Park Sye-young), and repertory screenings from filmmakers of all kinds (Stephen Sayadian, Sharon Lockhart, Raúl Ruiz). Below, find reviews of 11 different films that screened at the 9th Berlin Critics’ Week.

REVOLUTION+1 (Masao Adachi, 2022)

REVOLUTION+1 is a film about predetermination. Every element in Masao Adachi’s latest film is as fixed as the rain that gets superimposed over Tatsuya Kawakami (Soran Tamoto) when he’s lost in his thoughts. Tatsuya is a character based on Tetsuya Yamagami, the man who assassinated Shinzo Abe because of the former president’s ties with the Unification Church, an influential South Korean Christian cult. REVOLUTION+1 is a fictitious retelling of events, and the chain that links them all is short and materialist in nature: Kawakami’s father committed suicide, his mother donated all their money to the Unification Church, thus the family slipped into poverty. Abe has publicly supported the church, and his assassination is a symbolic correction of Tatsuya’s personal suffering. Some connections here, especially pertaining to a reenactment of the Lod Airport attack, double as a comment on both Tatsuya and Adachi’s trajectories. Adachi mentioned in a recent interview that during his research, he found a connection between Yamagami’s father and a member of the Japanese Red Army who carried out the attack. A quote from Kōzō Okamoto, the lone survivor of the attack due to a malfunctioning grenade, becomes Tatsuya’s personal mantra as he also dreams of “becoming a star in the sky.“ (Adachi filmed a fictionalized version of Okamoto’s subsequent imprisonment in 2007’s Prisoner/Terrorist.)

The film doesn’t shy away from romanticizing Tatsuya’s trajectory, yet it repeatedly plays the footage of Abe’s assassination as the violent destination of Tatsuya’s infatuation. The pixelated TV image stands in clear contrast to the kinetic and digital cinematography with which cinematographer Kenji Takama shot most of the film. The images are both too smooth and too oversaturated, lending them a melodramatic effect. Every scene pushes Kawakami further into isolation. The women in the film are either mirrors or distorted reflections of his pain and psyche. On one hand, they quote lyrics by The Blue Hearts as a symbolic approval of his isolation. On the other hand, they offer him a social life, but become irritated when he doesn’t reciprocate. His mother remains the only constant. They reach a tentative agreement that allows them to socialize but the distance between them remains palpable. His brother struggles with lymphoma and shares his rage. One day he snaps, takes a knife and attacks the headquarters of the UC, where he is subdued and put into a cell for further indoctrination. He builds a noose out of his straight-jacket and hangs himself. Later his ghost visits Kawakami to teach him how to properly aim a gun. While violence remains an expression of revolutionary action, Adachi complicates matters by bringing in Tatsuya’s sister. She has fashioned a life for herself and is frustrated that Tatsuya can’t do the same for himself, drifting from job to job with no clear ambitions. After the assassination, the film ends with her delivering a monologue against terrorism as a means to political or revolutionary ends, distancing herself from her brother’s actions.

Adachi’s broader points, however, get lost in the specifics of the case. Yamagami’s success in shifting the conversation around the Unification Church (at least in the short term), is both a vital claim for militant action and too specific an example to function as a blueprint. Across REVOLUTION+1, Tatsuya never fundamentally theorizes his violent impulse or is able to tie his beliefs into a broader and more coherent ideological framework. He’s all practice, and the editing remains relentless in its repetition: as Tatsuya slowly loses grip on his life, training sequence follows after training sequence, and shotgun blast follows after shotgun blast. Adachi, likewise, is less interested in questions of theory than showing the case as a quasi-manual on how to start revolutionary action, the titular +1 in the title an open call for viewer participation. It’s radical filmmaking chasing a more coherent political expression, one in which violence is less a social or emotional reflex than a clearly articulated political choice.

In the aforementioned interview, Adachi remains hesitant and eager to protect himself against legal liability: “Basically, I feel nobody should be using violence for political purposes. But I don’t deny violence as an option. There are times when violence against the enemy is necessary. Still, there is never one correct answer, even within the same political situation.” The more I sit with these words, the more they make me question the possibility of building an artistic career around military ideals. After Adachi made a film as clear and linear in its goal and images as Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War (1971), all other works could only exist in its orbit. Maybe it’s on critics to better navigate his works and allow for slippage as long as the slippage serves revolutionary goals. —Florian Weigl

Maputo Nakuzandza (Ariadine Zampaulo, 2022)

Ariadine Zampaulo’s Maputo Nakuzandza explores the lives of Mozambicans in the titular city, taking the format of a 24-hour multi-tiered narrative and turning it into a freewheeling portrait of contemporary Southern African postcolonial life. Zampaulo’s deft and light direction allows the characters and city to tell their own stories, enabling viewers to fill in the gaps: there’s a man running through the streets alone, a woman who catches her lover cheating. While Maputo Nakuzandza approaches the sweeping grandeur of a poetic city symphony, it finds connective tissue in the story of a bride who disappears from her wedding. Reports on her sighting recur throughout the film via radio—she’s first thought kidnapped before we begin seeing her. In one vivid scene, a procession of people silently walk past her as she’s sitting on a bench lost in thought. These radio reports appear alongside poems spoken by young Mozambican writers like Hirondina Joshua, and they foreground Maputo’s cosmopolitan diversity and history as a seat of Portuguese colonial power.

Portraiture is central to Maputo Nakuzandza, and Zampaulo’s most effective narrative framing involves a dreadlocked man who floats from the beach to a market, then to a cafe and a courtyard. He is laidback—unbound by time and obligation—and endlessly charming to everyone he encounters. There’s a scene in which this flâneur walks through a courtyard as two people discuss the Mozambican emperor Ngungunyane, and we hear of his rebellion against the Portuguese and his subsequent exile. This relationship between the city’s history and the emotional heft of modern life in urban Africa animates the film at large; the care with which Zampaulo approaches how this is all staged is a testament to his love for Maputo. —Ryan Waller

The Secret Formula (Rubén Gámez, 1965)

Rubén Gámez made a series of short films in the 1960s and ’70s that sought alternative modes of exploring Mexican culture and politics, free from the commercial cinematic language and imperialist politics imported from Hollywood. These works varied stylistically, from the quasi-documentary form of Whispers to the hilariously inventive restaging of the Mexican revolution in Magueyes, where a battle occurs between dueling agave armies. But in his most important work, The Secret Formula, Gámez adopts a witty surrealist approach in the vein of silent classics like Entr’acte or L’Âge d’Or.

The political charge of the film is clear from its first images: an IV drip tube plugged into a Coca-Cola bottle cuts to a long take of a car driving in wild circles through the Zócalo (Mexico City’s central square bordering both the Metropolitan Cathedral and the National Palace), suggesting a religious and political culture on capitalist life support. This juxtaposition is typical of his approach throughout The Secret Formula. Gámez intercuts lovers kissing with scenes of cow slaughter, transforms corpses into living women, and sets a man eating a sausage against a driving Stravinsky concerto. A string of sausages go on a murderous rampage, assaulting livestock and businessmen alike. The images are simultaneously comedic and disquieting.

Particular sequences and symbols may be ambiguous, but it’s clear where The Secret Formula’s sympathies and antagonisms lie. The Church is a recurring target: a group of priests at a playground watch young girls on a merry-go-round, and then are bitten to death by boys on nearby monkey bars. Gámez, who learned his craft working in advertising, litters his film with capitalist iconography like flashing silhouettes of Coca-Cola bottles, and ends it with a scrolling list of companies including Campbell Soup and Volkswagen.

In contrast, scenes of peasants are shot much more solemnly, and contain the film’s only texts. Written by the screenwriter Juan Rolfo, these words poetically embody the collective voice of the people. Groups of people stare straight into the camera before many are shown lying dead on the ground. Gámez finds some levity—in one humorous shot, the camera repeatedly pans away from a peasant who shuffles back and forth, attempting to stay in frame—but on the whole these segments express despair, and criticize the lack of voice given to the disenfranchised in mainstream Mexican cinema, and they encapsulate Gámez’s project of developing a radical aesthetic alternative. In that sense, The Secret Formula parallels its more propagandistic contemporaries in Latin American Third Cinema, but in contrast to what Solanas and Getino called the “cinema of revolution,” it offers a bleak diagnosis without a prescription for change. —Alex Fields

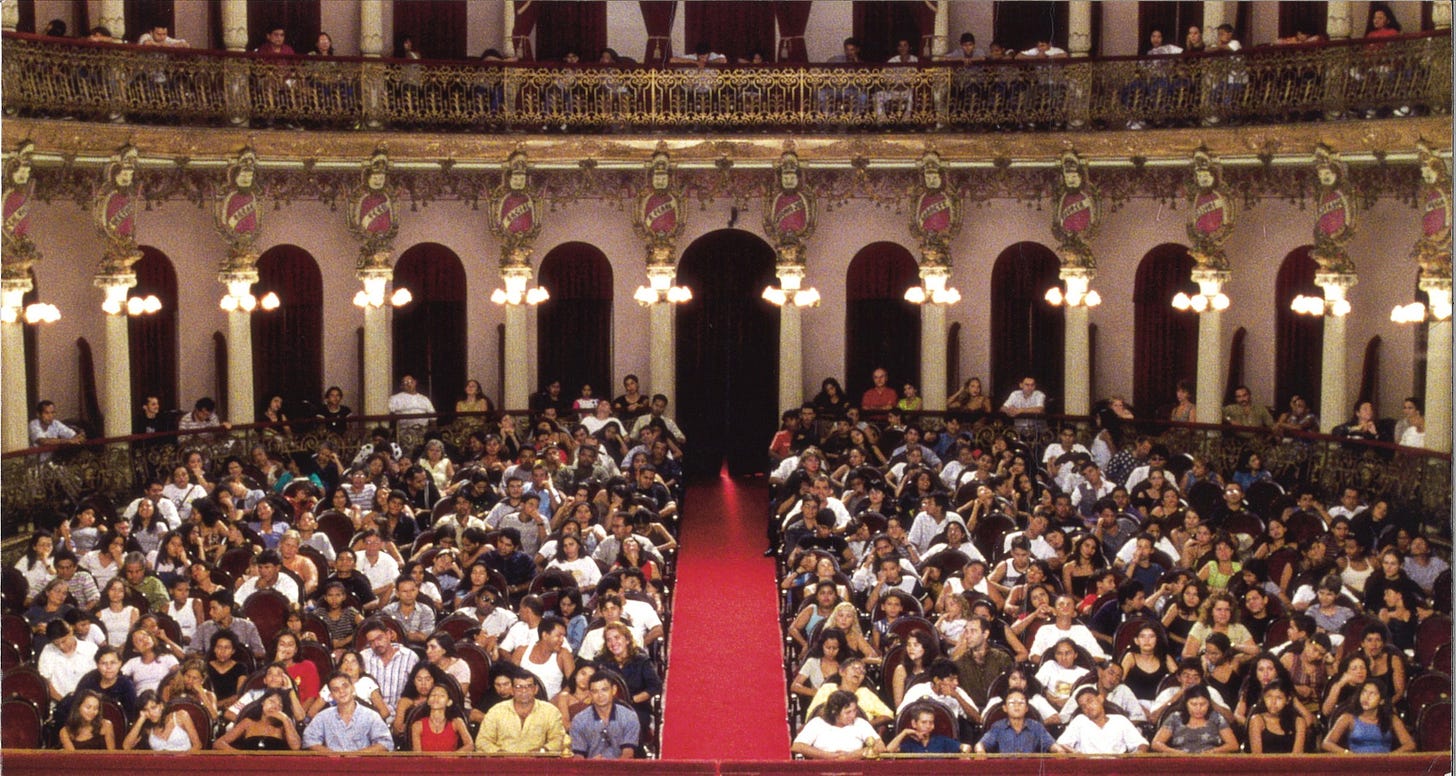

Teatro Amazonas (Sharon Lockhart, 1999)

The Teatro Amazonas is an opera house located in the Amazon rainforest. Built in the late 19th century, this building is the product of exploitation—both of the Indigenous population and their land—and was meant to appease the rubber barons who got rich from greedily extracting resources. (Things haven’t changed, either—it took 121 years before an Indigenous person actually performed on this stage in 2017.) Director Sharon Lockhart approached this sophomore feature with an understanding of this history, and depicts people from various districts of the Amazonas state. The result is an even more minimalist successor to her debut feature Goshogaoka (1998). Instead of the choreographed movements that blurred the line between play and practice, documentary and fiction, Teatro Amazonas revels in the collective randomness of an audience.

From the beginning of this half-hour film, we listen as the soundtrack arrives as a monolithic drone. This sound is rather one-dimensional on its surface, but the static frame forces a consideration for its many layers, and how it’s the result of an entire choir. The people singing come from the Choral do Amazonas, and while the piece was composed by Lockhart’s collaborator Becky Allen, specific vowel sounds were chosen based on local language. Near the film’s end, the music fades into coughing and fidgeting, drawing a clear link between art and life; every individual person, and their every individual action, builds the tapestry of the Amazonas state.

It’s interesting to watch this film and think of how it differs from those similar to it. There’s a playfulness to our watching, recalling the artifice and constructed loops of Zbigniew Rybczynski; each person feels like a layer to the film’s constructed whole. There are also films like Herz Frank’s Ten Minutes Older (1978) or Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin (2008), where we watch people watching things. There are close-ups in those works, pointing to the beauty of light shining across faces and the various emotions that arise from what they’re watching. Without anything actually being performed in Teatro Amazonas, Lockhart points to the ethnographic gaze we as viewers have with any such work. A question is posed: what is art and what is life, and why can’t they be one and the same? When Teatro Amazonas concludes with an unexpectedly long credits sequence listing every single person and the district they belong to, Lockhart reminds us that this land, this building, and this film—one in which nothing really happens but is nevertheless suffused with a particular energy—are all the result of the Indigenous people who instill them with life. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

The Film to Come (Raúl Ruiz, 1997)

Raúl Ruiz’s The Film to Come begins with a narrator describing a secret society known as the Philokinetes, a cult that has devoted itself to studying a looping 23-second “fragment of film.” In exposing yourself to it, one can enter a state of hypnosis where “you can see.” But while this is presented as a euphoric state, it feels as if the Philokinetes’ act of “seeing” is a closing off of the mind.

Information throughout The Film to Come is primarily delivered through a narrator—a father in search of his daughter (she disappeared during a screening). He tells us of the Philokinetes’ history and their beliefs, but there’s no reason to trust him: multiple voices deliver this narration, there are only a few scenes with the father himself, and there’s a disjunction between image and sound. At one point, we’re told that screenings take place on the fourth floor of a major metropolitan building, but the room we’re shown is a windowless, underground room with solid brick walls. This space, with clocks depicting different times, points to the impossibility of knowing the truth: the Philokinetes are divorced from a wider context of reality, and when viewing the film, their trance-like state is one of ignorance.

Later, the father discovers two priests who’ve taken a vow of illiteracy. They treat a book that they’re “reading” as film, interpreting letters, words, and sentences as images. As they flick through famous paintings and historical diagrams without much thought, Ruiz interrupts this scene with a cut to a blindfolded man wearing a pair of glasses. In a concerted effort to distill cinema to “the primeval soup of a new life form,” the Philokinetes have forgotten what film is; their faces may glow, but the beauty is fleeting. The father soon “sees” as the priests do, and he slowly accepts his death. The film then ends with a cut to black as the narrator says, “I understood that I too had become a part of the fragment entitled The Film to Come.” Without missing a beat, the credits begin playing, as if the film has bled into the credits and, consequently, our world. In his book Poetics of Cinema, Ruiz warns that “cinema in its industrial form is a predator. It is a machine for copying the visible world.” Such anxiety is far closer than we realize. —Jai Singh Bains

Solmatalua (Rodrigo Ribeiro-Andrade, 2022)

Rodrigo Ribeiro-Andrade’s Solmatalua leans into the rhyming logics of memory. Its songs, archival footage, and digitally rendered environments allow image and sound to freely intersect. In eschewing a traditional cinematic narrative, Ribeiro-Andrade engages with a history of avant-garde Black cinema and video art, connecting his film’s formal concerns and language to the work of artists like Arthur Jafa, Ulysses Jenkins, and the collaborations between Kevin Jerome Everson and Claudrena Harold. The result is a tapestry built from a dense avalanche of Black Brazilian cultural signifiers: a lush, expansive portrait of Brazil today.

I found myself hitching onto the shot of enslaved Africans aboard a ship—Ribeiro-Andrade introduces the image without any way to ascertain what it is. By reflecting and refracting the image along its axes, you’re forced to first reckon with its immensity—and your own immersion—before the camera scrolls up to show bodies stretching in every direction. There’s also a Clementina de Jesús sample heard in the Mbé song “Ponto,” which is juxtaposed with a shot of a Black man on the beach, a Black man rowing in water, and a Black woman at the beach offering praise to the sun. These images bear a striking attention to detail, and I found my heart swelling—they deeply resonated with me, a descendant of Jamaican Maroons.

The film’s center has favela passageways, narrow alleys, and winding staircases set to audio from a march in the name of Zumbi dos Palmares, a slave resistance leader. As the streets of the favela intersect and feed into each other, we hear the protestors proclaim his history, shouting that he is the last king of the Quilombo dos Palmares. This invocation of a Black leader—one who fought against and was ultimately killed by the Portuguese state—grounds these textural memories in a political framework. The revolutionary intent is clear: Ribeiro-Andrade is declaring that Black Brazilian history is indispensable in the creation of a contemporary Brazil. In the face of centuries of erasure, Solmatalua centers the Black Brazilian voice, and does so with a beautiful lyrical impressionism. —Ryan Waller

Melting Ink (Dominik Graf, 2023)

Dominik Graf’s Jeder Schreibt Für Sich Alleine (internationally distributed as Melting Ink) is an adaptation of Anatol Regnier’s book of the same name. Regnier compares the biographies of several writers who stayed in Germany during the Third Reich to understand how they wrote, published, and politically aligned themselves during the time. He writes about these authors both chronologically and simultaneously, a structure that Graf acknowledges cannot be reproduced in the current film industry. Thus, we get a more streamlined version, focusing on one author at a time but pairing them for how they related to the party.

Melting Ink is presented in three different sections and opens with its most well-known subjects: Gottfried Benn and Erich Kästner. Their political alignments are well-trod academic ground and there are few new insights—Benn openly cooperated with the Nazi Party only to be let down by it, while Kästner refused to take a public stance. They set the tone for a debate about art and the structures in which it is produced, a conversation that dominates the rest of the film. Graf’s film gets more interesting when it covers Hans Fallada and Ina Seidel, authors who struck up a working relationship with the Reich. While Fallada exiled himself to the countryside, Seidel took an active role in the Führerkult, but eventually distanced herself from the party, later disowning and reckoning with that period of her life to great public acclaim. During his research, Regnier discovers epistolary evidence of an affair she had with another woman during the Third Reich, complicating established readings.

Graf then tackles Hanns Johst and Will Vesper, authors who actively collaborated with the party for openly opportunistic and ideological reasons. Vesper’s case is further developed into a generational reading. Bernward Vesper, Will’s son, wrote throughout his whole life about his relationship with his father—his essay was posthumously published as Die Reise—and even published one of his books. He also was in a relationship with Red Army Faction founder Gudrun Ensslin before she eventually left him for Andreas Baader, which Regnier uses to draw a risible link between fascism and the leftist extremism of the RAF.

Visually, Melting Ink shows its rushed production. It features staid voiceover while the camera pans over archival footage and PowerPoint-style animated text. Graf soon returns to a familiar strategy of rupturing the boundaries between past and present. Regnier, who leads the film with a centrist’s awe for the cultural institution, visits several locations where he reads letters by authors or correspondences with their critics. Likewise, Graf conjures up the spirit of the authors in misbegotten reenactments, letting them wander in kitschy noir cloaks through a small bookshop, the voiceover asking rhetorical questions and musing about their contemporary relevance. Nothing necessitates these flashbacks, nor do they find a fruitful discursive tension with the narrative. It is important for a director to reach the natural limitations of their style, and there’s value in seeing this film with that in mind, but when Graf dresses up some actor as Himmler and has walk into a field to look wistfully towards the horizon, dirt running through his fingers, I checked out. —Florian Weigl

The Fifth Thoracic Vertebra (Park Sye-young, 2022)

Park Sye-young’s The Fifth Thoracic Vertebra is, at its heart, a creature feature. It focuses on the death that swirls around a fungal growth, and we see the world from its perspective as the old mattress it inhabits is carted around Seoul. The film’s sections are delineated by a ticking timer, informing us of the days remaining until the monster is born, and also how much time has passed since its birth. A less inspired director would approach The Fifth Thoracic Vertebra from a Cronenbergian angle, utilizing dark, brooding music and scenes centered around horrifying dread. But even though this is a film about a creature that brings death, it unfolds as a contemplative work that explores how people relate to one another. At first, this creature is entirely violent, feeding off the despair and ennui of its owners. After the initial couple who owns the mattress breaks up, it becomes abandoned and grows in size, and in a slow and menacing scene, it uses its stinger to kill the couple that inherits it. Later, the creature changes tack when coming into contact with a dying woman. She notices a presence inside the mattress and begins talking to it, writing a letter she asks to be delivered to her loved ones. The scene ends with the creature taking the letter from her unmoving hand.

Park has proclaimed to be committed to “personal, independent filmmaking,” and that’s evident from the simple environments across The Fifth Thoracic Vertebra: a bedroom, a hospital room, the interior of a taxi. When the creature finally tears free from the mattress and roams through nature, Park bathes it in sunlight, and finds it floating in a sea of other fungi. The sound of a strained alien closes the film, and we hear it read the letter written by the elderly woman. Though she’s passed, this moment feels like a rupture in the cycle of life that Park has depicted. In the face of death, kindness can connect people. And upon dying, your energy is returned to the earth. —Ryan Waller

Café Flesh (Stephen Sayadian, 1982)

Five years into a nuclear post-apocalypse, almost all of humankind has been rendered sterile. They no longer have access to pleasures of the flesh, and must now pay to watch the libidinous few who enjoy what they cannot. This scopophilic need is serviced by Café Flesh, where Sex Positives have been rounded up to enact fantasies for their insensate audience. Among the café’s bawdy skits, performed in burlesque show vignettes, are such high concepts as: housewife menaced by rat man in costume, while baby-bibbed men look on from their high chairs; office kitsch in the register of Michael Snow’s *Corpus Callosum; prison-yard power struggles (“Desire is in chains!”); and backlot studio horror. These all segue abruptly into scenes of unsimulated sex, soundtracked to Mitchell Froom’s discordant MTV-era pop-rock, and intercut with Sex Negative reaction shots that range from impassive to gazes of incipient lust.

In Café Flesh’s sci-fi framing, we as viewers are assigned the spectatorial position of its Sex Negatives—pleasure-seekers in search of illicit thrills. Hardcore pornography functions as the Sex Positive 1% to mainstream cinema’s 99%, a commodified spectacle available to all, but one whose jouissance is kept just out of reach. The directorial debut of Stephen Sayadian—credited here as “Rinse Dream,” alongside such pseudonymous collaborators as F.X. Pope and Pez D. Spencer—Café Flesh hails from a lost tradition of cult movie notoriety, where frank sexuality and experimental art-making once commingled with surreal promiscuity. While its post-industrial landscape shares some affinities with midnight circuit mainstay Eraserhead (1977), Café Flesh is best seen as a forerunner to Radioactive Dreams (1985), the great second film by recently deceased B-movie maestro Albert Pyun. Sayadian’s deeper-underground sensibility harmonizes with the goofy melancholia of Pyun’s film, where scrap-heap production design stands in for the implied collapse of wider society.

Haunted by nuclear paranoia and a mid-century radicalism outcast to the art world, these works of low-budget ingenuity tell a far grimmer story than the official culture of their time. Parallel developments in pinku eiga would soon give rise to the careers of Satō Hisayasu and Zeze Takahisa; yet despite analogous grasp of social breakdown, Sayadian feels more genuinely interested in his skin-to-skin sequences than the queasy brutality of a film like Splatter: Naked Blood (1996). Pain may lurk somewhere behind the pleasure, but here it manifests as malaise, a pervading ennui without moments of violent release.

Enterprising filmmakers of this time often found a low-overhead freedom to create amidst budget and distribution shortfalls. For Sayadian, whose funding strategy was to sell the sci-fi half of his narrative while withholding its more explicit intent from investors, the promise of copious cumshots served as a bait-and-switch for this work of downbeat speculative fiction. Such a narrative divide could have made for a disjointed film, but Café Flesh synthesizes its competing impulses with rare confidence, shifting between lo-fi dystopia and base commercial intent until neither segment feels distinct from the other. Sex will always sell, but for this brief moment in film history, there was no way of predicting what else might come with it. —M.S. Leo

The Demands of Ordinary Devotion (Eva Giolo, 2022)

Eva Giolo’s The Demands of Ordinary Devotion treats cinema as a tool for imaginative play. The film begins with a coin toss, and the fact we don’t know which side lands face up is part of the associative magic on display: there is no conclusion we should be looking for with these images, just constant cycles and repetitions that define life’s unexpected beauties. We quickly see a woman pumping breast milk, and its visual and sonic rhythms are followed by hands shaping clay on a potter’s wheel, and then someone spinning a Bolex’s winding crank, and then a pregnant woman rubbing her belly. When a finger then presses a button to let the Bolex run, a shot of a woman with her child makes sense of what came beforehand: Giolo is pointing to the symbolic relationship between different acts of creating and care, and helping us recognize the way all of life is this interconnected web of patterns that demand thoughtful repetition.

What becomes clearer as the film progresses is that the editing isn’t just humorous and delightful (I love the match cut that links a Bolex being zipped up in a bag with a child being embraced by her mother), but is meant to embody the briskness with which we should approach each day. Everything is random after all, Giolo suggests. The people she depicts have some semblance of control—the carpenter’s hands are always touching their materials, the filmmaker is carefully handling their camera, the mother is thoughtfully holding her child—but the physical connections we make are not evidence of mastery, but mere participation. Note that the end result of all these processes—the coin that’s flipped and the film being produced, the pottery that’s made and the child being reared—is ultimately out of our control. “The things of this world / exist, they are / you can’t refuse them,” reads a Lao Tzu quote at the beginning of the film. And that is the beauty of devotion: it requires faith in some inevitability. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Such a Long March (Dominique Loreau, 2022)

Every year, the Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) embarks on a migration across Belgium, at the end of which they will reproduce and die. Whether Dominique Loreau’s documentary Such a Long March is a study in the ethology of these crabs, or that of the humans who interact with them, it’s clear that our place in the ecosystem is not isolated. Rather than be carried along the rivers, the crabs must migrate along paths shared by humans, creating their own world within ours.

We open with only the body of the crab in focus, as if it is superimposed upon the legs that will carry it south. What follows is the quiet war between civilization and history. Articulated legs are torn off by the slice of a wheel, and quiet dread fills the screen as another crab waits in the crosswalk, unseen by bystanders, for that same crushing end. Cars crush carapace; exoskeletons protecting a different great migration win only by size. However, human structures are just as delicate; the film is inspired by a 2016 incident where an onslaught of traveling crabs disabled a nuclear power plant. These challenges of scale—hundreds of Davids versus one corporate-branded concrete Goliath—help to place the crab’s journey in society. So many of Such a Long March’s most striking images are just that: a carefully scaled place within a larger cycle of life.

The metaphor of the crab’s journey is applied parallel to that of human cultural migration, as a Chinese family in Belgium gathers around a meal of steamed crabs. Unlike the passing of tires on the road, this family never consumes without preserving: they create ink paintings that capture the patterns of crab’s bodies. The paintings resemble Japanese fish market gyotaku, sized to the soul of each crab that crosses the table. Only in nature do we see that same acknowledgement of the spiny travelers. Though this particular species is invasive both in Europe and North America, Such a Long March prefers to use language that views the crabs as travelers, and that their success is a natural adaptation.

Various locals (a locksmith, two young girls, the aforementioned family) act as a key to entering the world crawling at our feet. The clearest entry point is the two young girls. They find crabs on the sidewalk, placing them in a bucket to carry them to safety, and research for information about the animals. Their learning process—which involves searching online for how to sex this species of crab (though they’re mostly greeted with restaurant advertisements)—segments the middle of the film with an immersion-breaking influx of didacticism. The crab’s visit to their home is better served by the soft-focus long takes of a lone crab exploring at a dusty, cobweb-laden baseboard, sizing up its environment without narration.

Loreau’s animist approach to filmmaking stylizes the crab’s narrative. The static view of nature makes use of low-angle shots in our synthetic world, and macro images of wild movement give a literal sense of the crab’s perspective (images of rushing water from a drainage pipe combine the two). Lighting is determined by what the crab would see as important, emphasizing ambient light sources in the moon and reflections on water. Rather than use a literal imitation of crab vision, such as a fractalized split screen or multi-camera mimicry of the ommatidium, Loreau’s spiritual viewpoint of the crab’s journey finds more beauty in both the human—and arthropod—place within an ever-changing ecosystem. —Sarah Williams

Thank you for reading the 27th issue of Film Show. See you at next year’s Critics’ Week.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.