Film Show 023: Deborah Stratman

An interview with director Deborah Stratman about her filmography, including 'Last Things', which premiered at Sundance and screens at this year's Berlinale and True/False Film Fest

Deborah Stratman

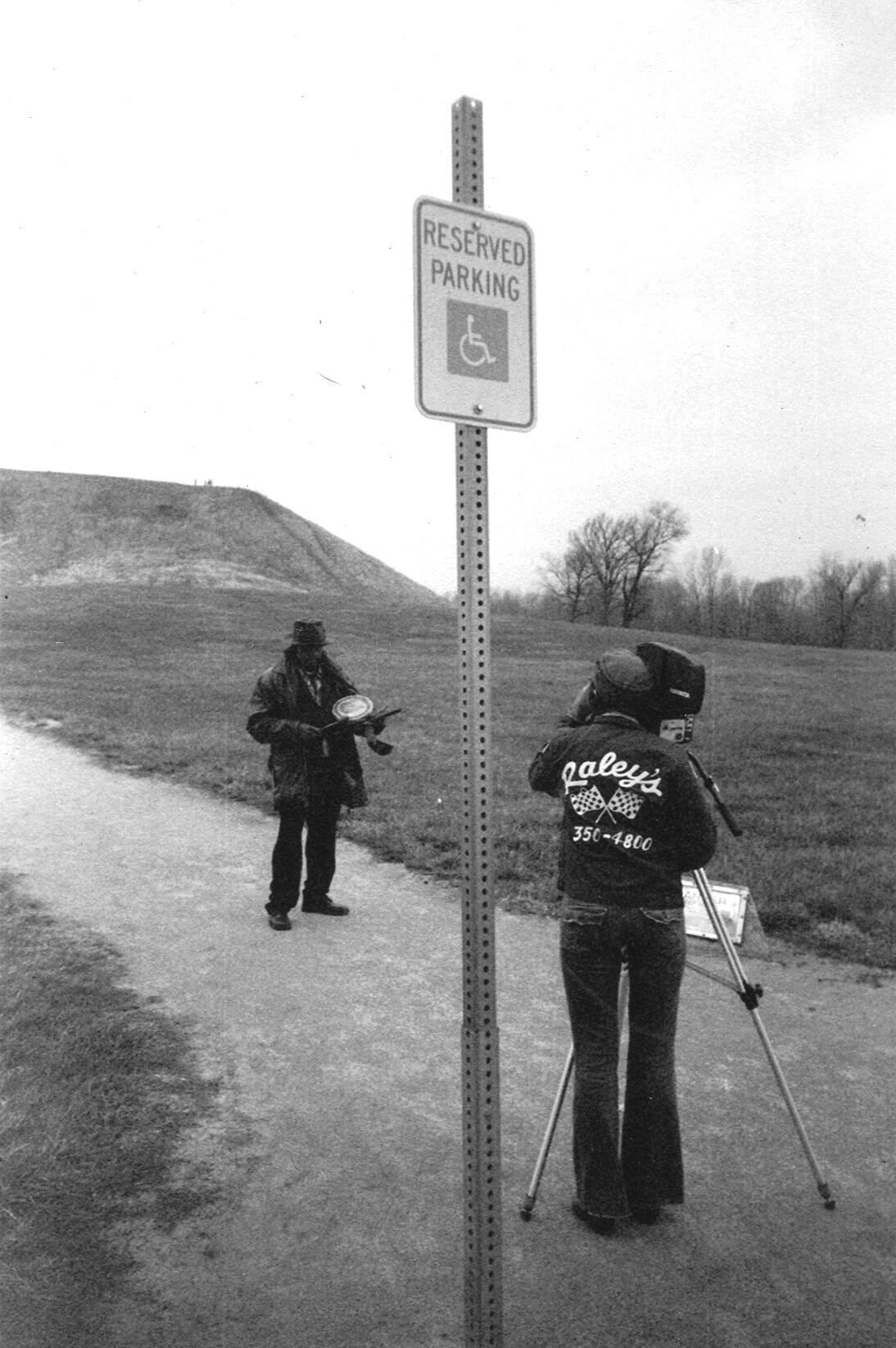

Deborah Stratman (b. 1967) is a Chicago-based artist and filmmaker whose works investigate issues of power, control, and belief, exploring how places, ideas, and society are intertwined. She regards sound as the ultimate multi-tool and time to be supernatural. Recent projects have addressed freedom, surveillance, public speech, sinkholes, levitation, orthoptera, raptors, comets, evolution, extinction, exodus, sisterhood, and faith. Her newest film, Last Things, is an avant-garde essay film concerned with the histories and stories embedded in the geo-biosphere, subtly pointing to the pretension and myopia of human superiority over the natural world. The film premiered at Sundance and is playing at this year’s edition of the Berlinale and True/False Film Festival. Specifically, Last Things is screening as part of Berlinale’s Forum Expanded programming, and is showing this Friday, February 17th at 5:30PM and on Saturday, February 18th at 8PM. Last Things will screen during True/False Film Festival on Thursday, March 2nd at 10:15PM and Saturday, March 4th at 9:30AM.

Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Deborah Stratman on February 7th, 2023 via Zoom to discuss numerous works from throughout her career, the way she approaches sound and structure in her films, music as a form of mainline communication, Barbara Hammer, and more.

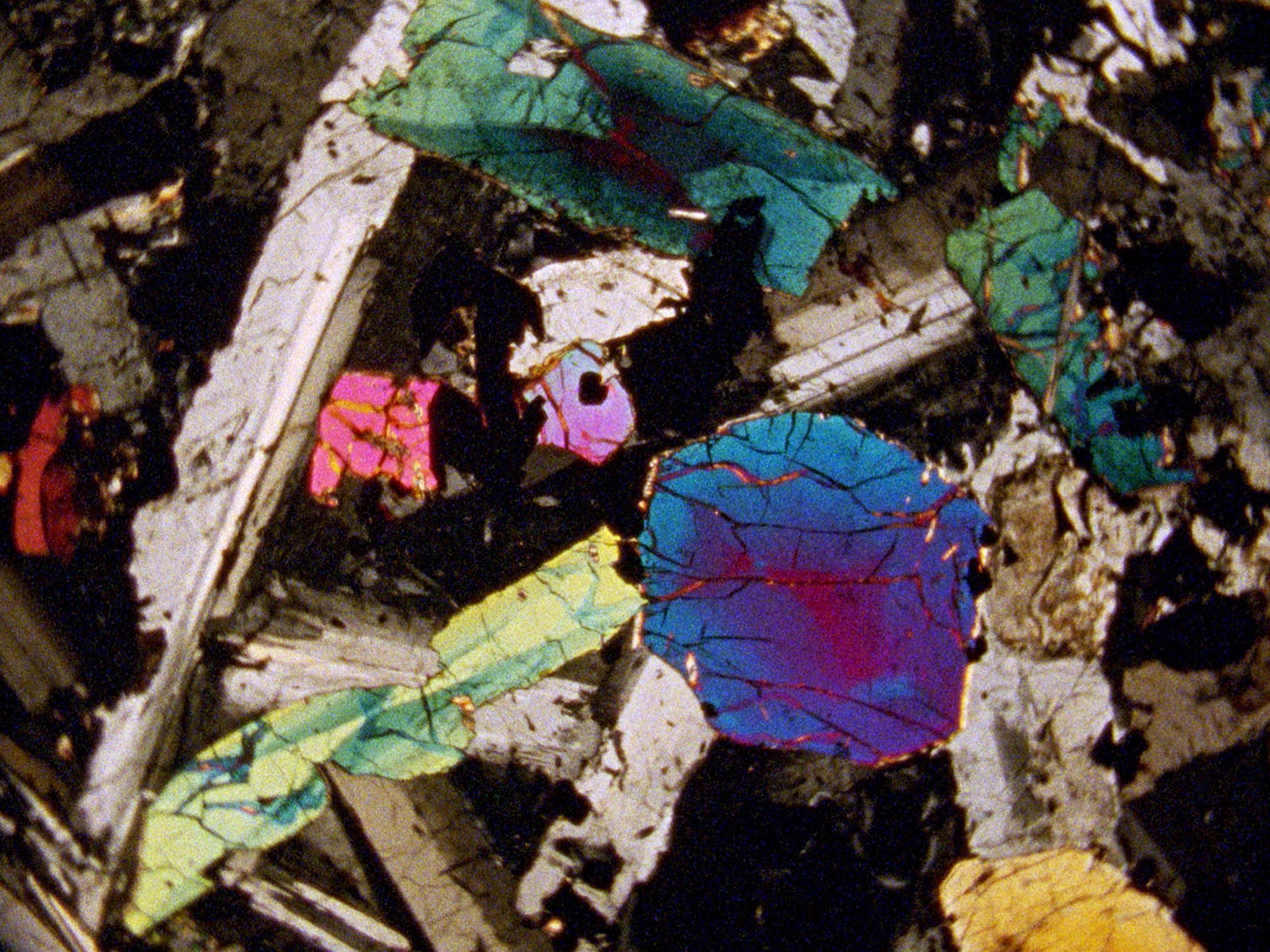

Joshua Minsoo Kim: I love how chondrules are mentioned in your new film Last Things (2023). They’re such a beautiful symbol for what a lot of your films are about—this notion of histories being etched into our landscapes and surroundings. Everything we interact with is shaped by—and tells stories of—various peoples and their histories, and I’m curious when you first started approaching life with this sort of mindset.

Deborah Stratman: I don’t know that I could say when I started being curious about… everything (laughter). But it’s been a long time. It infuriates people sometimes because I don’t stop asking questions. As a younger person, the sciences satisfied that in me, but at some point—probably from one too many attempts at a calculus class—I was like, hey, there must be some other way to satisfy this probing. And this feeling is curiosity nudged by wonderment. I mean… the world is freaking amazing. The more you ask questions of it the more it spews out crazy stuff.

Up through early college, I had been more science tracked—very physics tracked. I loved astronomy and particles and the hugeness of stuff. But these days I’m more interested in the sciences that hold history, like geology and biology. I pursued that physics track until calculus made things go haywire, and then I entered the arts and that was a revelation. It was like, oh, I can just ask everything I want to ask, through the process of making. I’m always making because I don’t know. Art seemed to have many more registers to ask in.

I never fully pursued the sciences because I started getting panicked about a few things. For one, just looking at what job options would be available down the line if I got into astrophysics or chemistry. At the time, it seemed like all the opportunities were under the umbrella of military or corporate big money. There are plenty of ways, no doubt, to be in the sciences without that being the funding structure, but it freaked me out as a young college student. I was like, okay (makes tire screeching sound) right turn. The observation part of the sciences I loved, but the proofs and formulaic way that you need to ask questions so that it can be peer reviewed and accepted felt like too much of a straightjacket. I totally get why that makes sense for the hard sciences, but it felt stifling to me.

So I can’t say when the curiosity thing started, but when I first learned about chondrules, it blew my mind. That we have these globs that fall to the earth and are older than the solar system, which as Marcia [Bjørnerud] says, are basically pieces of the sun… amazing.

That’s what is amazing, too—these things exist and you can just be oblivious to them for the rest of your life.

Yes! And if you just scratch the surface you find something that colors how you think about the world.

Were you born and raised in Chicago? I don’t actually know.

I was born in Washington D.C.—center of gov in the summer of love: 1967. My pop at the time was working for the U.S. government in patent law and then he left and moved to Chicagoland when I was around one and a half. I’ve been more or less based here since. I mean, it’s been porous; I’ve left a lot but it’s been my root for a long time.

You explained how you were into the sciences, and then eventually went into the arts. How did you land on making films? How did you decide that it would be the specific medium with which you would sate your curiosity?

I was exposed to film before I ever decided it’d be a good idea to do it as a career. Our family had a Super 8 camera. It was more my father’s—he used it most. When people came over, he’d project the Super 8 and show the slides, and that’d be the home entertainment. I definitely used that in high school, and like everyone else who was editing Super 8 back then, I was using those horrible tiny presstapes and trying to put a film together on my bedroom shag carpeting. I loved doing it but it never occurred to me to pursue film as a life path.

After I had my, well, let’s call it the Great Calculus Rift (laughter), I took time off from college to drift a bit and when I went back, I went to art school. I was doing what people do—taking a smorgasbord of classes, and one of them was a film class. I knew right away that it scratched a lot of itches. It took care of the optics-time-physics thing because of the nature of the medium. It was like, this is great—I can be a sculptor! Film’s just this balloon filled with time and that’s what I’m sculpting.

I didn’t learn on video. I could have… but it was all ¾-inch back then and a big pain in the ass to edit—very linear. Film felt comparatively nonlinear and fast, and I liked its mechanical nature. I was learning on the Bolex, which is such a wonderful tool if you’re into tools—you can take it apart and have some sense of how it works, unlike most today.

Also, working in film was a way to work with sound, and I was and am a sound junkie. I was into music and audio of every kind. I love radio, shortwave, ham radio—the whole electro-magnetosphere, really. Being able to work with sound is essential. It seemed like film had it all.

I watched On the Various Nature of Things (1995) last night when you sent it. The thing that was crazy to me was that I felt there was so much of your identity as a filmmaker already there at that age, and you were in your late 20s then.

I haven’t watched that in a while but you’re probably right.

You have the episodic structure, which reminded me of The Illinois Parables (2016). You have this one part where you have a light bulb swinging and that’s accompanied by the sound of this door hinge—I love that match.

Right! And it loses sync. So you have that expectation of some kind of relationship in this universe but then… (makes cartoonish swoosh sound) rug pulled out.

You have these images of fishmonger, too, and then a dead snake covered in bugs. And that’s something I really appreciate about your work—you are never allowing the audience to be content with, let’s say, a “vibe.” You want them to struggle to understand what’s happening; you’re instructing them, giving them the pieces, and asking them to put them together. Not only are you using your works as a way to explore different topics yourself, you are asking the audience to do the same when viewing. That invitation is always there, and while other films can be open-ended, I feel like they’re not often as warm in extending their hand in that way.

That’s a generous way to describe it. I want my films to be like someone cracking open a door for you so you can be like… ooh, what’s in there! And it might be really messed up, or it might be hilarious. You don’t know—and you don’t know because I don’t know. And that’s the problem and the solution. I wouldn’t make these films if I knew. It’s like building a bridge while you’re running on it.

I love that as a filmgoer. I like to be in confident hands, but I appreciate when a filmmaker has space for me to be lost in, or to drift out of for a little bit and come back. There’s nothing deadlier to me than a pedantic, “we’re gonna teach you a lesson about this political truth” film. Or any kind of truth, really, as if you could speak of truth in the singular. I totally get that a lot of people have no interest in puzzling when they go to the cinema—they just want to be strapped in the rollercoaster and go along for the ride, trusting the machine will take you there, and not have to think about where the track is going, let alone assembling it.

When you brought up the episodic structure of The Illinois Parables and On the Various Nature of Things, I thought of those… do you remember those little sliding puzzle games, where you had sixteen squares but one was missing? In those films, I have concrete episodes or statements, but the order is flexible in the way you make meaning from them, or the way you remember them. It’s not that I could’ve put them in any order, but I don’t think the films have a causal, typically “narrative” way of experiencing time. They’re more like a field of events.

You mentioned that you love filmmakers who leave space for you to be lost in. Something I noticed at the end of On the Various Nature of Things is that you thank a few filmmakers, including Thom Anderson, James Benning, and Betzy Bromberg. Were these people you were in contact with?

Oh yeah. I was in grad school when I made that and they were all my teachers—talk about an OG pantheon of instructors. It was very formative. I was also a projectionist for many years and that was honestly the biggest teacher—seeing so many films a week. That was huge.

I just realized I’ve gone from things that are “variously natured” to “last” things. That seems so depressing (laughter). But Last Things has secret first things on the inside.

It is really serendipitous that it ended up being that way, not that this is your last film, though it is in this exact moment.

Right, right. There are still things, whether they’re various or last.

As a projectionist, obviously you watch a ton of films, but do you think there was anything important about being in that role?

Phenomenologically, it’s such a meta place to sit. I was a changeover 35mm projectionist, and sometimes I showed video or 16mm, but most of the time it was changeover. So you watch the films, but you watch them in funny chunks because you always have to take the reel off and do the changeover at the 20 minute mark. So you miss three to five minutes every 20 minutes. You still hear it, though. But definitely, being in that space where you’re hovering above the cinema, in this dark booth, the way the film reflects on the glass… it’s very particular, furtive, and sensual I would say.

I’m sure this consciousness of the machine behind the scenes has leached into my filmmaking—in the way you can be really absorbed in a cinematic moment and then the next moment you’re pulled out into the wings and thinking about the whole infrastructure that’s making this operation go forward. I’m sure being a projectionist influenced that tendency towards perspective-shifting.

With your next film, From Hetty to Nancy (1997), you have these letters that are spoken aloud. There’s this one part in the film where text is scrolling and it’s about fox species. Obviously it’s a totally different experience to read something and hear something. The former is an inherently more active process. I suppose you could choose to ignore the text, but I feel like if you’re sitting in a theater and see any onscreen, you’re probably gonna read it. Whereas with sound, you can more readily zone out and not carefully listen. How do you determine what appears as written text versus what is spoken aloud? And also, how do you determine the language of anything that is spoken? With Last Things, you have words that are spoken in English and French, and there’s so many factors there—the different personalities inherent to each language, the necessity of subtitles and the way that impacts an audience’s experience. How do you approach all these elements when crafting your films?

Well, it’s definitely erratic, the way I approach it. First and foremost, the language strategy may on some level be a response to what work came previously. After a film that is heavily text-based, whether that’s read or heard, I swing the other way and do something with no language or something where we are not so subjected to it. In the case of From Hetty to Nancy, it’s very thick. Maybe there’s not more language in it than my other films, but it’s quite insistent.

The text came from journals and letters, but they’re fake letters from “Hetty” to Nancy, cataloging time spent traveling around Iceland with “Masie” and some schoolgirls... where Hetty and Masie were stand-ins for Louis MacNeice and [W. H.] Auden. That intrigue of the letter, the intrigue of scientific journaling, the intrigue of memoir, of the different ways that histories are written—the epistolary form was something I was very invested in, but it burned me out by the time that film was done. That’s not to say that I would’ve made it a different way; the way that language interjects itself is part of that film’s DNA.

The non-English passages in Last Things are read by Valérie Massadian. My idea was to have every text be read in the language it was written. But that failed because Val didn’t want to read in Portuguese, though she can speak it. So the [Clarice] Lispector had to be switched to English and my rule got immediately broken. I’d wanted texts to be expressed in the language they were written because translation is so fraught. Translations can be incredible, but they’re a different body, and I wanted the original body. But yes, mixing languages adds layers, especially with the subtitles. They can be a real distraction when you don’t want to read something.

Oh man, I love Val. I met her when I was in Marseilles for the film fest there a couple years ago and I’ve been wanting to connect with her again. We had such a great conversation.

She’s amazing, and she’s such a great filmmaker—one of my favorites. The first time I heard her recordings, I told her I got La Jetée (1962) goosebumps. Her delivery is so good, she’s amazing.

I want to make films that are indigenous to the language of film. I love using the written word and I love sentences and I love reading, but I don’t want cinema to be beholden to those structures. Film has its own structure! I want to say something cinematically that would be impossible to translate into a sentence. That’s the goal.

Oh yeah I’m in firm agreement with you. I hate when documentaries, for example, are so straightforward, rote, or didactic. It’s like, why wouldn’t I just read an article about this? Or the Wikipedia page? Why wouldn’t I just go to the library and read some books about the topic? There are so many times when I feel like I’ve wasted my time with a documentary because the images are secondary.

And sometimes the ideas are great! Like, I’m so behind everything with this film, except for the film (laughter). Why is cinema the language you’re choosing to speak in? It doesn’t make sense—it feels like a cop out. It pisses me off, actually. And someone like Val, and so many other filmmakers I love, they don’t cop out; they take a risk and invent their own language. That’s what I want to see.

Something I think about with your work is that your films can exist as standalone pieces, and you may have something like your Paranormal Trilogy, but a lot of them are building on each other or are engaging in a sort of dialogue. To give a simple example, you have The BLVD (1999), and then you have these different methods of exploring Chicago in Shrimp Chicken Fish (2010) and The Illinois Parables. I was wondering how often you’re thinking about previous works you’ve made, feeling like you need to explore something deeper in a new film. How often are you thinking about rectifying or expanding upon ideas you’ve explored?

You can’t avoid it on some level. The old films infect the new ones, whether I want them to or not. Sometimes I’m dissatisfied with a film, it annoyed me, or I took a stab at something and it failed. So then I return to the theme from a different angle. With the film Energy Country (2003), I mean it’s not a horrible film, but its harangue got to me. And that’s what O’er the Land (2009) came out of, this desire for a more open form—less of a scold, you know? There’s still a heavy criticality, but one that’s more generous. Sometimes you just gotta get pissed off—I don’t regret making Energy Country because I probably wouldn’t have made O’er the Land if I hadn’t—but I was frustrated enough with it that it provoked me to take a more oblique angle on militarism, capitalism, patriotism, on how we define freedom through ownership in this country.

The Illinois Parables was a cousin to O’er the Land, but in a different way. O’er the Land did the work I’d wanted it to, but early on I was thinking about religious freedom as being one of the freedoms it considered. Until I realized, oh my god, a film about freedom is about as unwieldy as you can get already. To combine it with religious freedom was like, just drop your hands and walk away (laughter). Religious freedom isn’t the core of what the Parables are about, but that unaddressed question was an engine that pushed me towards it.

Sometimes I try something in a small form and then want to see it in a large one. Or vice versa: I’ll have something in a large form and then want to sketch it out in miniature. I’m someone who loves the cut, the edit in every sense of the edit: everything your camera is turned away from, what you edit out of the world, what you hear and don’t see, where your frame is. I lean heavy on the work of the cut, so when I made Hacked Circuit (2014), which is a single-shot film, I was nervous about how to access dimensional meaning-making. So I made… what the hell is that film called, with the levitating—

Immortal, Suspended (2013)?

Yes, thank you. It was sort of a trial run—learning what a tracking shot could do. What are ways to gear shift without a cut?

I was wondering if that was some sort of practice or springboard for Hacked Circuit.

It definitely was some sort of practice. You know, I grossly misunderstood the size of that painting [The Thatched Hut of Dreaming of an Immortal by T’ang Yin]. I was obsessed with the painting. I read somewhere that it was 26 feet long, so I was like (in an extraordinarily excited tone) 26 feet long! Incredible! I wanted to arrange a film around that painting, and I wanted to be in the backroom of the museum so you don’t really know where you are: is it a morgue or is it some police station or what? It could be any number of institutions. And then you dip into the narrative of the painting, get seduced, and then you leave it again and you’re back in cold institutional archive land.

I got a dolly and a dolly pusher [Matthew Thompson] and when we get down there, they bring out the painting and it’s in this little dinky box… because it’s a scroll! It’s mostly text and the painting is just this one small part of the scroll. So, lesson learned (laughter). What was gonna be a formidable pan of some 26-foot long painting was instead barely a 2-foot long painting.

I love that film because you juxtapose a theoretical physics professor with [magician and illusionist] Criss Angel (laughter). One of my favorite things about that fact is realizing when you have voices—and you have multiple voices in a lot of your films, of course—we as viewers can appreciate them at face value. We don’t know the context of the person speaking unless we’re deeply familiar with their voice already. I like this flattening of identity because the text—the message itself—is what we’re interfacing with.

I totally hear that, and that’s part of it—once the voice is disassociated, it’s gonna seek a body. But what that body is could be anything. It could be a landscape, it could be another person. There’s a big opening for what this voice gets magnetized into, but there’s also so much in a voice that tells you who, or what time frame, or what part of the planet. We get a ton of information from idiom, from the texture of a voice. So while I agree that you may not know which specific person, a voice can tell us a lot about the speaker even if we don’t know the precise body it’s attached to.

Oh yeah, wow. Right. And I love what you’re talking about in terms of the voice being magnetized into different things. It’s like you’re putting the soul of this body into a different entity.

That’s why people fell in love with recorded music, right? You could put a soul—a sound—into a wax cylinder. There was a huge spiritualist revival at the beginning of recorded sound because suddenly the material world had a temporal, speaking side to it. It was crazy for people then. It’s crazy for me now! (laughter). But it definitely was back then—this paradigm shift of previously mute things capable of containing time, containing voice. That the material world could suddenly talk was spooky magic.

Now this is making me think of Musical Insects (2013). One thing I appreciate about how it’s filmed is that your camera is constantly moving between different parts of a page. It kind of feels like I am the bug, mimicking their sudden movements (laughter). But also, the way you juxtapose the different sounds of the bugs and have the jazz music playing—I interpreted that as them being one and the same, and I was thinking about how improvisation is happening in both. It’s like the bugs are an ensemble. And that’s maybe how we should think about reading text in a book, especially with a field guide or something like that. When we decide what pages, and what parts of a page to read, we are constructing our own little ensemble piece.

They’re definitely a jazz set in nature (laughs). I love listening to noise-making insects. That was one of those serendipitous, very quick films. There was a commission asking filmmakers to reflect on a favorite book, and I thought of this one by Bette J. Davis. And there was this piece of music by Fontanelle. I took out the book, took out the camera, and presto.

I was filming while listening to that track [“The Adjacent Possible”], so the way my camera moves, and when I would start or stop were very influenced by the music. There are external cuts in the film but very few; mostly it’s all in-camera. I barely had to do anything—all I did was take out the music in the first half and then put in the bug sounds. Making that film was like going ice skating—the camera was skating on the surface of the page. In two days it was done, while other films take ten years.

Which ones have taken ten years?

It’s never because I’m focused on them the whole time. Certain films need a lot more exposure because I start working on them before I know how to speak the language. The Illinois Parables, from the first thing I shot to the end, was about ten years. Last Things didn’t take ten years—I made that in one and a half or two years—but there’s footage I shot 15 years ago in there. I returned to it as if it were found footage. I like shooting with no intention. Shooting when the world snags me.

I understand that. I don’t do this much anymore but something I used to do literally all the time was take my Zoom recorder and just record everything around me. I loved the fact that pressing record was enough to change my state of mind—I was more attentive to my surroundings—and that was all I needed.

Oh yeah! And hacking it too—playing back those snippets when you’re in public, people are like (mimicking someone looking back in confusion) (laughter).

We talked about your sense of wonderment, and obviously your films have a very sprawling nature, but what sort of things do you do to set limits?

Does it seem like I set limits!? (laughter)

I think about something like Second Sighted (2014), where you only used footage from the Chicago Film Archives, not to say that they don’t have a ton of stuff, but there was some sort of limitation there. And obviously with Vever (For Barbara) (2018) you are using footage from Barbara Hammer. Those are some obvious examples.

I definitely love an assignment, because you have the limits of the assignment. So for a film like Second Sighted or my collaboration with Barbara—not that it was technically an assignment—but from the first second there were edges that were defined by someone else and that’s always helpful. To have conditions I can’t do anything about, that I get to invent within—it’s a relief.

I think sometimes I can be good at setting them for myself, and other times it’s just a matter of time. Like, I gotta be done with this or I’m gonna go nuts. I would’ve kept researching for Last Things… infinitely, perhaps. I didn’t feel bored reading about all that stuff, but I felt done with being… in the middle of the film. So I thought, I gotta put the brakes on this project. Sometimes it’s just about getting antsy.

What about something like the Paranormal Trilogy—How Among the Frozen Words She Found Some Odd Ones (2005), It Will Die Out in the Mind (2007), and The Magician’s House (2007). The first of those is so short, it’s only a few seconds long.

Oh yeah, it’s definitely less than a minute.

Was it a gut feeling in terms of how long the film should be? I bring up these films because they’re all really short.

Yes. In terms of how long a film is, that’s just… the film tells me. Period. I don’t know how else to explain it. I don’t know beforehand. The trilogy you’re bringing up, I didn’t have a trilogy in mind. I just had three separate short ideas and when I had finished the third one, I retrospectively realized that they worked together, but I didn’t know that going in. The consistent theme here is that I don’t know, Joshua (laughter).

That’s the secret to life! I was actually just thinking about this today. There was an article that went up today in the New Yorker about imposter syndrome. I didn’t actually read it yet, but I was thinking about how I maybe do have imposter syndrome, but that I potentially embrace it? Not knowing stuff is beautiful! And I guess I’m speaking about all this as a science teacher.

That’s right! That tripped me out when you emailed me that. Sorry I forgot that at the beginning of our conversation.

No, it’s alright! But like, why would I ever want to feel like I know everything, or that I’m completely competent, or am fully accomplished? The fact that there is always so much more to know and learn is what gets me going every day. That’s the drive for everything I do, really.

Years ago I was run over by a truck and was in a full leg cast for months. It was a Midas muffler truck… and that’s how I paid for In Order Not To Be Here (2002), which is another story. I was doing a lot of reading because I was so sedentary, and I’m usually pretty active, especially back then, which was 20+ years ago. I was reading Kafka’s Aphorisms, and there was this passage about not doing anything, just sitting still, about being quiet and not running forward into the world. Just let it unfurl in front of you and it will be spectacular. That completely shifted my head because I have hard time being static. The accident forced me to realize that sitting still and listening is awesome. You don’t have to ask—the world will splay itself out for you.

You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.

—Franz Kafka, The Zürau Aphorisms (1931)

This accident was around the early 2000s?

It was on the way to get my visa to go to China and shoot Kings of the Sky (2004). So the brakes got put on that project for a few years, and it also took a long time to get around to editing it. I shot it real quick and then stepped away from it for two years. In Order Not to Be Here happened in betwixt, with a broken leg.

I like that film a lot, and I also think it’s in dialogue with Hacked Circuit in a way.

Oh yeah, that’s true.

I was curious how you first got in touch with Kevin Drumm, who did the soundtrack for that. That year was when he released Sheer Hellish Miasma, which is probably his most famous work up until that point.

I didn’t know he was from Chicago. I bought Comedy (2000) at a record store in New York City on a hunch I’d like it. It went way beyond expectations. I reached out at some point because I knew this person’s sounds would be perfect in dialogue with the images. It was only then we realized he lived less than a mile from where I did (laughter). That was an excellent, fortuitous discovery.

What is your relationship to music in general? Obviously film is a medium that encompasses all these things you were interested in, but what is meaningful about music to you when removed from the context of film?

I just love vibration. Sound is everything. It’s the engine to our souls—it’s mainline communication. It barely needs a medium! It just needs molecules to vibrate. With the senses that humans have—the five doors into our house, or however many doors you may have in your house—we’re really set up to appreciate vibration. I love going to hear live music, I love playing music, although I haven’t played for years. I used to be in bands, and I like singing. It’s just such a nice way to be… massaged.

I always tell people that music is my first love because it requires so little of me. It can just exist and I can be so into it. I love that it can be such a passive and active experience, and I love being able to switch between the two.

And it’s so physiological! Even if you’re listening passively, your heart rate is changing because of what you’re listening to—that’s what I mean by mainline. It doesn’t cut corners. Even if you hate a piece of music, that’s still a mainline communication. Noise irritation. Sounds we’re annoyed by become “noise”—even if it is music. Isn’t that the main thing people call 311 about? People have a very low tolerance for sound that rubs them the wrong way, and vice versa—they’re profoundly transported by music that they feel speaks their language. It’s primal and it’s great. Thank you musicians, for putting music in the world.

I think at the end of Energy Country it says that you did the sound for that. Is that just field recordings or are you doing actual “music-making.”

I’m more of a musique concrète music maker. I don’t think I’ve ever played a classical instrument in any of my films, but I always do the sound design. The sound design is where it’s at. I’m very possessive about it, though I’ve worked with Olivia Block a couple of times where she did the design. I’m glad to have had that experience of handing it over to someone else, but it felt bizarre. One time it was a music video so I was generating visuals for a completed piece of music. And in the other we were collaborating at the same time—her sonically and me visually—but most of the time, I’m sound designing, composing in the musique concrète way—arranging music, ambiance, effects, voice… just all the levels. Sound is so much more dimensional than picture. That’s why I love it.

I feel like something I bemoan a lot is how so many experimental filmmakers don’t care about sound. There’s so much it can do to an image.

And to a non-image! Sound makes space. Image doesn’t make space, it represents it.

Are there any films that were particularly challenging in order to get the sound design right?

All of them have their struggles. Some fail because I didn’t have time to figure out the right sound before a deadline. I have a tendency towards operatic, overdone sound. I can overdo the drone, I admit it (laughter). I’m trying to develop a lighter touch.

Let’s talk about a specific film, and I guess a drone (laughter). Let’s talk about Laika (2021), which ends with that noisy ambience. How much are you A/B testing in terms of a sound working?

In the case of Laika, I had the sound first, because that was the music video for Olivia Block. That’s her composition, so that was a bit unusual for me in the sense that the sound was pre-locked. She’d asked me to do a video for one of the other songs on that release, Innocent Passage in the Territorial Sea (2021). I liked all the tracks on the album but the first time I heard Laika, I literally saw the image in my head of a reversed space capsule parachute. So I asked to do that one because I already knew what half the film could be.

Other times, I’ll have a sense of a general tone or mood. In the case of The Illinois Parables, I knew I could use more pieces of traditional music because the film is so static. It could sustain more melody, which to me is like a protagonist. There aren’t many protagonists in front of the camera, so there was more room for melodic protagonists. Other times, like with Vever—with Barbara Hammer—I knew about her footage but I never saw it until after we had the two phone conversations you end up hearing on the soundtrack. I had a hunch that the conversation would be an anchor for how to structure the film, but I didn’t know for sure. And because I hadn’t seen the footage I really didn’t know. In the case of Hacked Circuit, there’s Walter Murch’s sound from The Conversation (1974) and David Shire’s music. That’s a predetermined element. But we also had 16 live mics, so I was able to sculpt a new terrain through the mixing.

Sound and image are always in dialogue. Sometimes only one is real chatty, sometimes they’re in the same room actually talking about the same thing. But a lot of times I like giving them space to talk about pretty different things because if we’re already getting one channel of information visually, why repeat it sonically? I use the sound channel for other content. I know for some viewers the gap between sound and image—especially when it gets really big—can be annoying. But I love it.

It was either Walter Murch or Michel Chion who related audio-visual dimensionality to the gap between our eyes. The sound-image gap is fascinating because it’s malleable, unlike the gap between eyes which is fixed around 60mm. The sound-image gap can slide from nothing—where you hear precisely what you’re seeing—to infinitely far apart. The eye gap provides the difference from which our brain produces dimensionality, so the gap between what we hear and what we see has the capacity to produce exponentially more dimension because it’s infinitely variable. That interval has compelled me for years.

I realized while you were talking that I actually own the Olivia Block album.

Oh you do! That’s so funny. That swelling, oceanic crescendo that you hear at the end of Laika—on her album it cuts to an almost Suicide-esque propulsive, electronic track (makes intense beating sound). It’s an amazing cut. It gave me the idea in the film to cut to silence. It’s different than what she’s doing, but it’s in homage to the work of that album track cut.

Now I wanna ask about Last Things, because Olivia Block is on there as well, along with Matchess.

Matchess was a new discovery for me, I’m really digging her stuff.

And then you have Thomas Ankersmit and Mary Lattimore, too. I don’t know if you remember this, but at a screening of Optimism (2018) at the Chicago International Film Festival, I asked how you knew Mary.

Ooohhh! I totally didn’t make the connection that it was you!

You couldn’t have! In my mind I was just like, oh wow why is she being thanked? And now she’s in this new film!

That was actually during the same time! When I was cutting Optimism at Headlands, she and Lenka Clayton came to look at a rough cut and gave me some feedback. But then she also helped when I needed people to carry those tetrahedron mirrors you see in Last Things.

Do you feel like you learn when collaborating with musicians in a way that you wouldn't from just talking to filmmakers?

Part of the reason what’s called “documentary” appeals to me is that the range of people you can put yourself in proximity to is so diverse. I like being able to glean from people who do something real different from me. And for musicians that’s also the case, but maybe it’s been a longer love—I’ve loved producing and listening to music since I was little. There’s a lot of music in the family. I was lucky to grow up in a house where playing music wasn’t an alien thing.

Did you play anything growing up?

I played clarinet, piano, accordion, electric bass. I was in bands playing bass. Some friends and I are starting a choir right now because I miss music but don’t have the commitment that being in a band requires. But singing, you just show up and sing. For our first song we’re gonna cover Moondog’s “Enough About Human Rights.”

That’ll be fun!

We’ll see where it goes. We’re actually having our first meeting tomorrow which is why it’s on my mind.

How many people are in the choir?

We don’t know! (laughter). It’s just whoever shows up. I think there are probably a group of 10 who want to do it and maybe six who will be there. It would be nice if it was more like 20. If you feel like singing you should come by!

Earlier you were talking about the importance of making films that take advantage of the medium. Something I thought about while you said that was how in FF (2010), your flicker film, you pair your flickers with this dance. I thought that was so fun. There might be a purist who sees that film and feels it strays too far from something that’s just pure flickers, but I love how you merge those two because it feels like they’re dancing together—they’re partners!

That’s a nice way to put it. I hadn’t really thought about it that way but I like how the vortex of the dancing bodies’ works together with the flicker. Actually, that film is the third example of me not doing my own sound design. Melissa Dubbin and Aaron Davidson created a soundtrack, what they called a “future film,” then approached artists to generate the visuals. The footage I used was outtakes from Walking is Dancing (2010), a very quickly made doc that I shot in Malawi. It was a commission. It’s problematic but I’m glad I had the experience of shooting there.

There is one film I wanted to talk about because it feels like an anomaly. That’s Untied (2001). In your description for it, it seems like the film was a way for you to process trauma.

I think that’s true in terms of catalyst, if not in terms of structure. A psychic purge definitely catalyzed the film. Though a film like Energy Country falls into that category too, of using a film to do some kind of psychic work. O’er the Land did that too, and so did In Order Not to Be Here. A lot of times these films are processing psycho-social realities that are disturbing to me. Untied was just more intimate than most.

And you’re using the sound in that film to help accelerate that psychic process. It acts as lubricant I guess (laughter). In Untied you have the phone off-hook tone and the vinyl loop.

Right, the vinyl stuck in the groove. There are a lot of “stuck” sounds. It’s all about the habits that we get into, where we don’t even know how stuck we are. And when you’re unstuck it’s like, oh my god, there’s no road! It’s a freedom.

And then it ends with ice skating!

It’s actually driving on the Salt Flats. When flats are dry, you can go wherever you want.

How does film help you process these different things in your life versus other avenues?

It turns the anxiety into a thing. I can put it outside of myself. I still have to deal with it but it makes it feel less intimidating. It’s not that everything I make is, like, I could either go to the psychiatrist or I could make a film. But if I wasn’t making, I would be crazy. It feels like having extra limbs. Making is how I navigate the world.

Sometimes you have to find an outlet.

Right. You have to find your own car to drive. If you don’t, the road can really beat you up.

This goes back to what we talked about with Second Sighted, with different things being magnetized to the images. It’s a similar idea here, and there’s some distancing present when making films to process something.

It’s my nature to burrow, I like to dig in. I’m an obsessive person and I like other people who are obsessive—people who get lost in something they care about. It can be both amazing and a curse.

I watched this movie recently called Marathon (2002) by Amir Naderi. It’s a microbudget fiction feature set in New York and it’s about this woman wanting to solve 77 crossword puzzles in one day. That film has incredible sound design.

That’s a hilarious plot, I like it.

Yeah! And her apartment’s a huge mess because there are newspapers everywhere across her floor. The thing I love about it is that it gets to the heart of people with these obsessions. Like you said, it’s a blessing and a curse—these goals we set for ourselves, the things we set out to do. They’re what keeps us going. Obviously from an outsider’s perspective it can seem like we’re crazy, but that’s why it’s exciting, and that’s why life is so fun. Of course I’m crazy—why would I not be crazy if given the choice?

(laughs). Right. If you’re not crazy then you’re crazy! Normal is the new crazy. Being crazy is the new normal. Or maybe it’s the old normal? It’s always been like that.

Is there anything that you wanted to talk about that we didn’t get to today?

I’ve been wondering about something lately. Having had no outrageous obstacles as a young person, not living in a war zone, not being displaced, or abused or dispossessed—how much of my curiosity is a byproduct of not having to think about what I needed to do to survive as a kid, or whenever. I’ve been feeling real conscious of gliding through my youth. Because most of the world doesn’t, you know?

I have this paper rubbing I made from Hannah Arendt’s grave a few years ago when I was visiting Bard. I remember when I rubbed it, worms started to come out from underneath the headstone. I was like, “Is this happening? I’m not on drugs. It’s like a horror movie! Or something weirder.” That has nothing to do with this interview… or maybe it does! Maybe it has everything to do with vibration and our ancestors. I bring that up because of Last Things, where I’m thinking about death and life, of legacy, of the circumstances you come into and leave the planet with.

Do you think about the legacy that you have or will leave based on your films?

Indirectly, yeah. I think anybody who’s producing things—be it writing or music or whatever—it’s hard not to think about how they might speak on their own once you’re gone. I do think about it but it’s never an engine. I talked with Barbara Hammer a lot about legacy because when we were making Vever, she was very close to death. It was really in the front of her mind—getting her shit in order, the moves she wanted to make towards the end. It was good to talk to someone in that headspace, and so unfearful of it. Or if she was fearful, she was holding hands with that fear and okay with it.

Do you mind sharing anything about Barbara Hammer that can help paint a portrait of who she was? I love her films.

She’s a stubborn, generous genius.

I love it.

We weren’t friends before we did that project. We had known of each other’s work but Vever was a kind of arranged marriage. We went in pretty cold but with a level of trust for one another. I wasn’t gonna say “no” to Barbara Hammer, is what it comes down to (laughter). I was so psyched to get her phone call, to be asked, and was equally intimidated. I was like, how am I ever going to do justice to her as an artist? Thank god Maya Deren came into the picture because once we were three, it helped share the load. But yeah, Barbara Hammer—an inspiration. She was a fiery lady. We were both motorcyclists, but she was way more intrepid. She rode all through Africa and Afghanistan. She was a total badass with her BMW—she went everywhere.

There’s one question I end all my interviews with that I wanted to ask you: Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

(pauses). What do I love about myself… that’s such a hard question! My god, do people have an answer right away?

I will say that I love ending my interviews with this question because it helps sum up everything regardless of what is said or how quickly people respond. I feel like you can learn a lot about someone based on how they answer this question. (pauses). Not to put pressure on whatever you’re going to say (laughter).

I know!

I also ask this question to my students.

I was just gonna say... I love the classroom or any situation where you’re co-producing society. So I like the version of myself that’s in that space. I love my hermit self. And I love my dancing self, my socially-in-the-midst-of-something self. I like being in media res—the self that leans in.

Deborah Stratman’s new film Last Things is playing at this year’s edition of the Berlinale and True/False Film Festival. More information about Stratman can be found at her website.

Carbon Snake Reaction

Deborah Stratman kindly asked that I provide an explanation for how the “carbon snake” reaction works. A video and explanation are provided below.

2 C12H22O11 (sugar) + 2 H2SO4 (sulfuric acid) + O2 (oxygen) → 22 C (carbon) + 2 CO2 + 24 H2O (water) + 2 SO2 (sulfur dioxide)

For this reaction you’ll need granulated sugar aka sucrose (C12H22O11) and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4). I use 18M sulfuric acid as I’ve found weaker concentrations to be significantly less effective. This reaction should take place in a fume hood.

I fill about 1/4 to 1/3 of a beaker with sugar and then pour in sulfuric acid so that the liquid covers it—there should be a small layer of the acid on top of the sugar. Then I use a glass stirring rod to mix the reactants. You’ll see a dehydration reaction take place: Water is released (visible as steam), heat is produced (be careful when touching the beaker!), and you’ll see the color change from white to a caramelized yellow-brown to pitch black (which is the carbon; the hydrogen and oxygen atoms are removed from the sugar). While stirring, you should eventually arrive at a black liquid, and you’ll see this carbon build up into the “snake.” Note that sulfur dioxide (SO2) will also be released, which gives off a pungent, rotten egg-like odor. To dispose of the chemicals, place the beaker + other materials in a bucket with water and baking soda.

Thank you for reading the 23rd issue of Film Show. Let’s hold hands with fear.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.