Film Show 022: Miryam Charles

An interview with director Miryam Charles about her debut feature 'Cette Maison' ('This House')

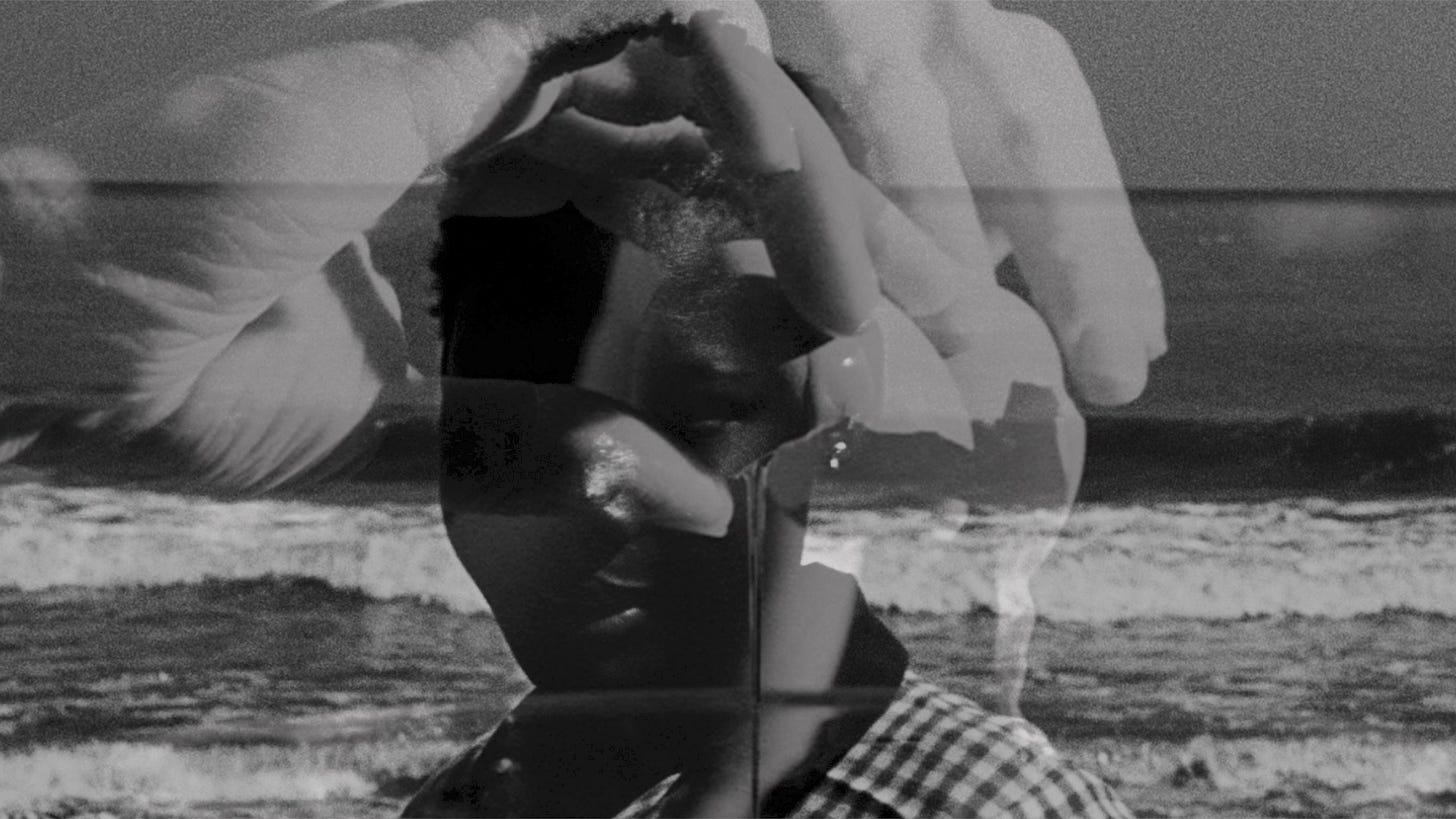

Miryam Charles

Miryam Charles (b. 1984) is a Haitian-Canadian director, producer, and cinematographer living in Montreal. Throughout the past decade she has made several short films that involve themes about identity and place, often related to her family’s migration from Haiti to Canada. Her debut feature, Cette Maison aka This House premiered last year at the Berlinale. The film finds Charles thinking about and celebrating her late cousin, utilizing a circuitous narrative and dreamlike dissolves to convey the amorphous and evolving nature of memories, people, and ideas related to home. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Charles via Zoom on February 18th, 2022 in light of its premiere at the Berlinale to discuss her family, the link between Haitian storytelling and her filmmaking process, and more.

This House plays this Friday, February 10th at BAM as part of their Caribbean Film Series. The film will also be screened alongside many of her short films this Sunday, February 12th at Maysles Documentary Center in Harlem. The event is followed by a conversation with Charles. Her films will also be screening at Acropolis Cinema in Los Angeles on Thursday, February 16th. Charles will also partake in “Frequências: Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Cinema & the Black Diaspora,” a symposium held by University of Iowa’s Obermann Center for Advanced Studies. The symposium will take place March 30th to April 1st.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: In another interview you mentioned this text called In Praise of Creoleness. There’s a lot from it I want to touch on, but something I’m thinking about is this idea of oral tradition. In a lot of parts of Western society today, oral tradition is dying and feels less relevant, or is at least less revered. What is the importance of oral tradition to you?

Miryam Charles: I often say the way I make films is the same way that my dad used to tell stories. He never picked up a book, he was just inventing stuff (laughter). It didn’t make a lot of sense but we understood the intention and the emotion. And the way Haitians tell stories, we kind of go back and forth, trying to remember stuff—even with my younger cousins or little sisters, we have a certain way of telling stories. Sometimes they get very confusing, but once you’re used to it the stories make a lot of sense. It’s actually how I construct and deconstruct films while making them.

Do you mind sharing one of the stories your dad told you?

I’ll try to tell one and have it make sense (laughter). I have to remember it in the way he told me it… (pauses). It’s a story of two children who are lost on a road. They’re walking towards a city and are suddenly in a boat, and they’re trying to find their way back home. Then they’re suddenly on the top of a mountain, and we don’t even know how they got out of the boat—my dad never explained it (laughter). They’re at the top of this mountain, bickering, and the story ends with them never actually finding their way back—they just go around exploring the country. It’s about this idea of wanting to go back home and not being able to, which is an idea that resonates a lot with my films.

Do you feel like these stories were told to present a certain message or moral, or was it more about enjoying the act of hearing and sharing stories?

I think it’s a bit of both. I should ask him about it, but I think from a young age he wanted us to understand that at times there is no resolution—you have to accept that. And that’s helped me. Sometimes you just don’t know, and that’s okay.

In what ways has it helped you?

It helped with the making of this film. With working through grief. Sometimes, things happen and you have to move forward. I thought that when making This House, I would feel at peace and that everything would come back to normal, but it didn’t. I’ve had to embrace that.

There’s this other part in In Praise of Creoleness where they talk about how Creoleness is in a state of pre-literature, that the possibilities for what it could be and mean are unknown. And even with This House, at the beginning it talks about how you’re inventing a story and that it’s a way to travel through time and space. What you’re saying is aligned with all that too—how this notion of not having a resolution points to the importance of the process. Do you mind sharing how you initially started working on This House? It’s clear from your short films that you were tackling similar ideas too.

I wasn’t really looking to make a feature film. I love short films and I’m still working on them, and I thought my career as a filmmaker would just involve doing short films. I was at peace with that. But the producer of This House wrote to me and suggested that I try to make a feature. At first I said no, but for a couple of months he would write a message saying, “Think about it.” He was being very nice.

I’m always trying to find courage while making films, and for each of my shorts I was tackling a subject I was afraid of. I thought for the feature that I would embrace a subject that I was most afraid of—the death of my cousin. I never thought that I’d be able to do it, so a part of me was like, okay let’s try this. I was trying to write a love letter to my cousin and my family. At first I think it took me so much time because I wanted to do it the right way—I wanted to honor my cousin and her legacy. So it started with this email from my producer and then five years later we had a film.

Do you mind sharing something about your cousin that paints a portrait of who they were?

She was very curious. She talked all the time (laughter). Sometimes it’d be like, we need a little bit of peace! (laughter). It’s funny because I was like that as a teenager, talking all the time, but I became very quiet and shy. She reminded me of myself when I was younger. She loved books and poetry and was really loving.

You said that you wanted to film this in the “right way.” What would have been the wrong way to film This House?

When my cousin died, I became very obsessed with true crime documentaries and series, both good and bad. I could talk a lot about them (laughs). A part of me wanted to understand how somebody could murder someone—it didn’t make sense to me. You hear about these things in the news but maybe because it was with someone close to me, my mind couldn’t grasp that fact. So I became obsessed with true crime, trying to understand why people murdered others.

A lot of the time, these [programs] focus on the murderers and their background story and not really on the people who actually died. The wrong way to have filmed This House would have been to focus on the person who killed my cousin and not on her. I also did not want to put too much emphasis on the murder. I wanted to talk about what she meant to me, the fact that she was loved—these positive aspects about her. Even though she died, it’s possible to be hopeful about someone even if they’re not there anymore.

When I watched your shorts, a lot of them are about murder or death but none of your works actually show that happening onscreen. Instead, you’re showing letters and landscapes and we’re hearing people talk. What have you learned from making your short films that you feel like was necessary for you to make This House?

I think I learned that it’s possible to film an event without showing it. I was a bit afraid with This House that it wouldn’t be enough. I felt like it worked with my short films because of the runtime—they’re very short, like five to nine minutes. For that period of time, the spectator is okay with the fact that we’re not seeing it. I was scared when I began writing this feature that it would’ve been more difficult, and I had a lot of conversations with the producer about that. I decided to stay true to myself and it is also very close to the way I am as a person. I don’t like confrontation, and it would’ve been a bit false for me to have done it in a different way.

In making the film, how much were you talking with your family about what you would be depicting? Did they play a role in its creation?

They played a role in the beginning, when I told them that I was going to make a movie about my cousin’s death. But at the same time, they saw my short films so they knew that it was going to be experimental and poetic (laughter). They were very happy about it in a way because when my cousin died, and maybe because she died such a violent death, we sort of stopped talking about it. It was to protect ourselves. And now that I’ve finished the film, we’re starting to talk about her again—her mannerisms, the jokes she used to make. It took us 12 or 13 years to do that. I’m very happy that this film brought her back to us, and in a positive light.

How do you feel like not talking about her impacted you and your family?

I think it was normal. Nobody felt weird about it. I started feeling weird about it when I started to make this movie. It was just easier for us to not talk about it and pretend that it didn’t happen, even though it’s weird to say that out loud. We just got on with our lives. I also come from a family with a very religious background, so everybody just hoped that we would see her in heaven someday.

Do you consider yourself a religious person?

In a way I am because I took all the positive values of being brought up in a Christian household. Even if I was rebellious as a teenager, saying “I’m not going to church anymore!”, all those positive things are still inside of me. And there are a lot of religious songs in the film.

How do you decide on what songs to use in your films?

It’s determined early on, though it was different for This House because there were a lot of fiction scenes. Usually what I do is record any narration and songs and then I edit the sound. I’m always starting a movie or project with sound in mind. When I write fiction, the actors always find it weird because I put so many sound notes about what we hear but it’s really important. Music is really central to me.

There’s a moment of silence in the film after we hear what happens to the cousin. And in your short film Towards the Colonies (2016), there’s a point when it’s completely silent as well. Does silence play a big role in your life?

I’m very sensitive to sound. I’m mainly on my own, very quiet at home. Even when I go out with friends, after a certain amount of time I get very dizzy—there’s too much noise so I have to leave (laughs). I love silence, silence is everything. It puts me at ease, it helps me think.

One other big aspect of your work is this idea of language, and there’s this one part from In Praise of Creoleness that I want to read:

Our primary richness, we the Creole writers, is to be able to speak several languages: Creole, French, English, Portuguese, Spanish, etc. Now we must accept this perpetual bilingualism and abandon the old attitude we had toward it. Out of this compost, we must grow our speech. Out of these languages, we must build our own language.

Do you mind speaking about this multilingual reality? Do you find it meaningful?

I think it helps me a lot but it also creates a lot of internal conflict. My parents are from Haiti and they speak Haitian Creole. They also speak French, which they learned in school. They moved to Canada in the mid-70s, and when I was younger my parents wanted us to speak good French—even better French than what was spoken in Quebec, because they have a Québécois accent. My parents wanted us to have a French accent from France! (laughter). Which makes no sense!

They didn’t speak Creole to us when we were kids. They started when we were teenagers. I speak Haitian Creole with a French accent, which for me is kind of sad (laughs). Each time I go to Haiti I feel very ashamed because everybody will know that I’m not from there. Haiti was also colonized by the French so it’s a bit weird in that way. Each time I make a film, I’m questioning myself about which original language to use. For This House I was a bit conflicted because I knew that most of it would be in French, but at the last moment I decided to do all the narration I do in the film in Creole, even if I don’t speak it perfectly.

At first, I thought I’d ask a friend—Schelby [Jean-Baptiste], who is in the film—to help me with the Creole because hers is better than mine. But then I decided to let it be. The Creole in the film exists as the language of the children of immigrants—immigrants who decided not to speak it to their children early in their lives. For me, it has a bit of nostalgia because it’s not perfect. I saw the film last week, and as I was listening to it, I was like, I made so many mistakes (laughter). Like, oh my god! When my mom sees it she’s gonna… (laughter). I could have corrected it but I decided to let it be the way I speak the language. In a way it’s a homage to the language because I tried to speak it the best that I could, and the result is what we have in the film.

Was it hard for you to come to that decision, with being okay with this imperfection?

No, because I recorded the narration last minute. Because I’m not an actor, I felt like the emotions were true, and if I corrected the text I would have rehearsed it and it would’ve felt different. The intentions and emotions are true, even if there are some mistakes.

Why did you decide to make the narration in Creole? As in, why wasn’t it in reverse: Why weren’t the actors speaking in Creole and have the narration in French?

Not all the actors knew Creole, and I didn’t want them to learn it, even though I know they are actors and that actors can do anything. It’s important for me that most of the film was in French because it’s a beautiful language, and it’s close to my heart. It’s also the language I speak most of the time. It also creates a disconnect.

What does the Creole language mean to you?

It means the future. I know that may not make a lot of sense, but when I was younger my main goal was to grow up and go back to live in Haiti. Now the situation is very complicated in the country so I don’t know if it’s a possible dream, but I’m not giving up on it. Creole means everything. It’s the language of my mother. Even though my parents decided not to talk to us in Creole when we were born, my sister is doing the opposite: she just had a kid and now she’s speaking to her in Creole to be sure she will learn the language properly. It provides that connection to Haiti, which is beautiful and powerful.

There’s this one scene in the film where there’s talk of a handsome, young man. And it’s said that this should be spoken in Creole and not in French.

When I was younger, I didn’t speak in French and my aunts would answer to us in Creole. My grandma also used to do that: she spoke French but would never answer you in it—you would have a conversation with her in French but she would answer you in Creole. That scene was an homage to my aunties and my grandma.

Do you feel like Canada is home to you?

I would say yes because most of my family is here, but when I’m in Haiti, that also feels like home. I think I decided a couple years ago that, because I was obsessed with going back home and finding my place in the world, your home could be in multiple places. In fact, home is just where you are.

What specific things define one’s home then? Is it just family?

I think it has to come from within yourself. When I was younger I really thought it was gonna come from society, or someone external from myself accepting me into their group as a citizen or something, but it has to come from within. And really it has to be love—a place where there is love is a good place to call home.

Given what you’ve said earlier regarding your feelings about Haiti and its colonization by the French, are there any things you do to ensure your work is “decolonized”? And what does that mean to you?

That’s a big question. I don’t know if I can make sure that it happens, because the moment you finish something, it’s out of your hands—people can decide whether you did a good job or not. But I think a lot of it is in the intention. My intention is to stay true to myself. Earlier I said that I don’t like confrontation, but there’s a lot of anger and resentment I feel about the effects of colonization, even here in Canada. I think it’s there in my films but usually in a soft way. I understood from a young age that if you confront people directly, they won’t listen to you. But if you do it with a subtler approach, they tend to listen more carefully.

Do you mind sharing an example of how you’ve shown this in one of your shorts?

In Three Atlas (2018) when I talk about vampirism. And there’s someone who is accused of murdering her boss and drinking his blood. It’s a subtext in the film; she never talks about how she was abused in that house and such, but I knew that when I was writing the screenplay, I was writing about that. And I thought that if I went around the topic, it would be better. Sometimes I feel like it’s not the best approach, but as I said, it’s close to who I am. I really wish I could confront people directly sometimes, but I like to take a step back, observe what’s happening, and try to find a way to talk about a subject or situation.

Now that’s making me think of This House and the scene with the dead body with the white sheet, and how that dissolves into the shape of the island—there’s some sort of longing for home, and a place to belong. It made me think about the death of the body and the death of the home, simultaneously, or a returning to home. Were there any challenges while making This House that made you think creatively to find solutions?

I’ve watched the film many, many times and the vision of the film that I wanted to make—even though I’m really proud of how it turned out—is different from what it is. At first it was supposed to be a documentary. I was going to visit several family members’ houses and I would’ve had my actress come with me and interact with a lot of them. But then COVID happened and nobody was comfortable with a film crew coming in, which I totally understand. When shooting began, there was no vaccine yet and it was really crazy.

I decided to write more fiction scenes based on memories and conversations I previously had with my family members. I was also supposed to go back to Haiti, with my actors, to shoot some scenes. But the insurance company said, “no way.” And I didn’t want to put my actress in a weird situation. I went to Saint Lucia and Dominica to shoot some exterior scenes that would remind myself and the public of Haiti. And I think the fact that I wasn’t able to go back to Haiti to shoot my first feature added to this feeling of sadness and nostalgia related to going back home.

I think most people don’t know Haiti and won’t know the difference. I showed a couple of Haitian friends and immediately, from the first shots, they were like, “This is not Haiti.” (laughter). I did what I could with the circumstances. It’s very interesting that the two characters go back and don’t recognize anything. They look at the maps and don’t know what’s going on.

That relates to another theme that runs through your films, this idea of trauma and the way it affects memory.

Even if I went to therapy and talked about everything with a therapist, I feel like there still wouldn’t be a complete resolution. And sometimes you have to accept that there won’t be one. I thought a lot while editing This House. Initially I thought, I’m going to be editing this for years, because I kept reconstructing and deconstructing. I received an email from an editor who had seen my short films and wanted to meet. We went for a walk in the park and after an hour I was like, “Are you busy?” I was desperate (laughter). I was running around in circles trying to edit the movie. We edited the film together and that’s how I got to finish it. With trauma, and I guess this depends on who you are, you can become quite obsessive on details when trying to make sense of something that may never make sense. And now I’m embracing the obsessiveness and the fact that there’s no resolution.

Did you have a specific goal for what you wanted this film to convey to audiences, or was this more for yourself and your family?

I know this will sound naïve and cheesy, but I don’t care: I wanted to share the fact that love is all that we have. We have to keep it close to our hearts, even in tragedy. I know that the film is not for everybody—it’s a bit weird (laughs)—but if while watching it you get a sense that love is everything, I’ll be at peace.

How do you reconcile this idea of your films not having completely clear narratives—which aligns with you not being confrontational in some ways—with you wanting to get a message across? How does that play out when making films?

That’s the thing: I only hope that it will come across. I don’t want to impose. As humans we try to find peace in structure and try to make sense of everything, but for me nothing about life makes sense. It’s all a little weird (laughs). But, there are a few things that make sense to me, and one of those is love. It’s okay if people don’t get that from the film, but I’m hoping they’ll at least have felt an experience. I want people to make up their mind about what something means.

Most people find peace in structure, like you said, but do you feel like you find peace when there isn’t one?

I would say that, yes. And I really try to be more of a conventional filmmaker and storyteller but I can’t—I can’t escape my brain. I would love it, I love conventional fictions, I love Hollywood blockbusters, but that’s not who I am.

There’s one question I wanted to ask you that I always ask people: Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

I love the fact that I’m weird, and that I love silence. I often say that I don’t have the temperament to be a filmmaker because I’m very quiet and on my own. When I went to Berlin, I presented the film and did a Q&A. Since I’m very quiet and shy, I was in a total state of panic during it (laughter). I wanted to die beforehand. And then I had to watch the film with the public and it felt so long (laughter). People told me the Q&A was good, but from my point of view I was just dying. Aside from all that, no one saw me. I don’t do PR. I was taking notes, observing life and people. In that way, maybe I’m weird. And my love of silence is just who I am. I would spend days, if I could, in total silence.

Miryam Charles’ This House plays this Friday, February 10th at BAM as part of their Caribbean Film Series. The film will also be screened alongside many of her short films this Sunday, February 12th at Maysles Documentary Center in Harlem. The event is followed by a conversation with Charles. Charles will also partake in “Frequências: Contemporary Afro-Brazilian Cinema & the Black Diaspora,” a symposium held by University of Iowa’s Obermann Center for Advanced Studies. The symposium will take place March 30th to April 1st.

Thank you for reading the 22nd issue of Film Show. Spend some time in silence today.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.