Film Show 019: James Benning

An interview with filmmaker James Benning about growing up in Milwaukee, his organizing experiences, and various films from throughout his career

James Benning

James Benning (b. 1942) is an American filmmaker who has spent the past five decades capturing American landscapes and realities. With over 80 films across five decades, Benning has remained fiercely independent, committed to making works that find their roots in the conceptual and structural films of the American avant-garde. In the 1970s he collaborated with Bette Gordon on four films, the most notable of which is The United States of America (1975), a road trip film that provides a snapshot of the country through pop songs, news radio clips, and scenic views through a car windshield. He would apply specific formal rules and toy with sound-image relationships on films such as 11 x 14 (1977) and One Way Boogie Woogie (1977), providing an entry point into understanding America via beguiling half-narratives, humor, and sharp editing. “I want [my audience] to have to work a little when they watch a film,” he said in a 1978 interview with Wide Angle.

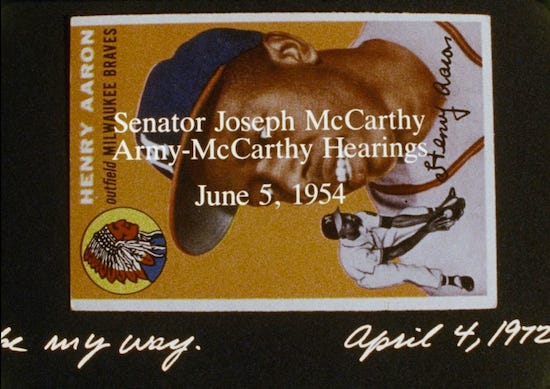

Benning’s films would become increasingly sprawling and ambitious. American Dreams: Lost and Found (1984) presents Hank Aaron baseball cards alongside various bits of contemporary pop culture and news as scrolling onscreen text reveals entries from the diary of Arthur Bremer, a man who attempted to assassinate presidential candidate George Wallace. Murderers would be explored on Landscape Suicide (1986) and Used Innocence (1989), the latter of which features correspondence between Benning and Bambi, a convicted murderer who would eventually escape from prison. Such deep involvement with the creation of films would continue on North on Evers (1991), a work that involved an extensive cross-country road trip on his motorcycle and is partially focused on the assassinated civil rights activist Medgar Evers. While Benning’s early 20s were spent organizing, his move into a career in film would find his political beliefs suffusing his works without being didactic, simplistic, or cavalier.

The 1990s would also find Benning making works that focused on the American Southwest. Especially noteworthy is Deseret (1995), which juxtaposes shots of Utah with news stories from The New York Times dating between 1851 and 1994. (“Deseret” refers to the name of a provisional state proposed by Mormon settlers that was never eventually accepted by the US Government.) Formalist meditations on landscapes and place would continue in his California Trilogy—El Valley Centro (1999), Los (2000), and Sogobi (2001)—and even further on 13 Lakes (2004) and Ten Skies (2004). The latter is the subject of a phenomenal book by Erika Balsom, published by Fireflies Press.

Benning’s move to digital filmmaking would officially arrive with Ruhr (2009). In an interview with Scott MacDonald, Benning explained that this change occurred due to “labs’ and programmers’ lack of concern for quality control and good projection.” Still, this new era finds the filmmaker in an especially prolific mode. He created “remakes” of John Cassavetes’ Faces and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider at the turn of the decade. While not a fan of either work, Benning found both films to be interesting opportunities to explore transformation. Such interest has existed throughout his career; in the aforementioned 1978 interview, Benning talked of an interest in “evolution,” but one that was “not in the image itself, but in our way of looking at it.”

Such transformations of time, films, and space are present in two recent works, The United States of America (2022) and TEN YEARS LATER (2022). The former is, in some ways, a revisiting of ideas from the 1975 film of the same name, but is largely concerned with confronting the viewer with any illusory comprehension of America. The latter finds Benning revisiting a location in the Sierra Nevada where he shot his film Nightfall (2012). Benning currently has an exhibit in Milwaukee, his city of birth, which features his work BNSF (2013) alongside a film from Sharon Lockhart, a director that Benning has been inspired by and in conversation with for many years. The exhibit runs until January 1st. The two have also released a book that was designed by Martin Beck titled Over Time. Despite having the same title as the Milwaukee exhibition, it is not a catalogue for the show, and more so functions as a visual dialogue between both artists with some additional text. Benning’s The United States of America (2022) is also screening twice during the Viennale. Benning will be doing a post-film Q&A for at least one of the screenings.

Joshua Minsoo Kim spoke with James Benning at his friend’s home in Chicago on August 11th, 2022. The two discussed his childhood, his organizing experiences, his pedagogical strategies as a professor, and various films from throughout his career.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Before we get into your films, I wanted to talk about your upbringing. You were born in the 1940s and grew up in Milwaukee, so this was when Allis Chalmers was the big company there. What sort of memories do you have of growing up? What was your father like?

James Benning: When I was very young, my father had a painting business with his brother, but he was also a self-taught architect and building designer. After they were doing house painting, he started to draw plans to build small houses. He didn’t have any degree—he went to Boys Tech High School in Milwaukee and he learned on his own. He could do almost anything, and I was always amazed by him. A very early memory was that during World War II, he worked at the Falk Corporation. He wasn’t drafted into the war, but he was drafted into the war industry and started to make landing gears for B-29 bombers. He worked at home and he liked to fish and hunt, and my brother liked to fish and hunt too. I’d go along a few times but I wasn’t into that world at all.

So he was an older brother?

Yeah, just two years older.

What did your mother do?

She stayed at home and helped my father if he needed any typing. She was a typical 1940s/1950s housewife. She was a really sweet, kind, caring woman; my brother and I were really lucky to have her as a mother. Both my parents gave us a lot of freedom. In the ’50s you could just leave your house all day long and go anywhere. We’d play in the Industrial Valley along the rivers and do really dangerous stuff that nobody knew about.

What was the most dangerous stuff you two got into?

It was just foolish stuff. Drowning out gophers in the water, or catching gophers and then letting them go on the streetcar (laughter). Just stupid stuff.

Do you feel similar to your parents in any way? As in, do you feel like you’ve inherited bits of their personalities or values?

They were quite conservative. I’d like to have a lot of their values as to how caring they were and things like that, but not really. I think I was much different. My brother pretty much adapted to their lifestyle but I think I was outside of that a bit. They unfortunately never knew who I was—my father died when I was 30, and I had just started to make films at that point. I had been doing neighborhood organizing in Missouri before that and it was somewhat dangerous and they really did not want to know how dangerous things were and what we were doing; there wasn’t much communication.

What was your role in organizing? What did you do?

Well, first I worked a little bit in Colorado. There was a group called Tent City that would set up tents and befriend migrants and work in the fields for a while to get to know them. They’d offer their children a place to learn how to read and write and I taught a little bit of arithmetic to those kids for a while. We also helped with, if they’d get arrested for having a tail light out, that they shouldn’t be fined $500. That was very politicizing because local judges were very against the migrants and you could see that there was no concern for the poor. I was very politicized from all that organizing.

Later I worked in Springfield, Missouri in a very poor ghetto which was interesting because it was poor whites and Blacks living together, getting along quite well. But there were all the problems of poverty—and a lot of alcoholism. We started a dropout school and also started a commodities food program. It wasn’t just me; it was a bunch of people over a 13-county area that ended up feeding like 150,000 people with commodity foods. That was quite satisfying.

It’s interesting how you mention that there were Black and white people living in the same area. I think I recall an interview where you mentioned that the neighborhood you grew up in was more segregated.

Yeah, it was a poor white working-class community and the Black ghetto kept growing closer to us. There was extreme prejudice. The poor whites hated the poor Blacks and the Black people, in return, did the same. There was no analysis of poverty, and all of the theories came true—the property values dropped, and it got ugly. My mother was the last white person to live in that neighborhood, and it was very dangerous at the end for her to be the only white person. But in the beginning, when the first Black people moved in, there was a Black family that lived next door to my mother—my father had died by then—and I came to visit her and she whispered that there were Black people next door saying, “But he shovels my snow and helps me cut the grass, they’re really kind people.” And then she added something: “They can’t help they’re Black.” They didn’t think of themselves as prejudiced; she was understanding on a one-to-one basis that this was a wonderful man, but she still had this prejudice that was prevalent in the neighborhood. She was my age now in the late ’70s. I felt it was too late for a conversation to make any sense.

When I was younger, I joined some of the marches led by Father James Groppi, who was a white Jesuit priest who had his parish in the Black community. He was a leader of Black youth and he invited poor whites to join in because he saw this problem as something that we shared. A few people from my neighborhood were curious and I went down there. That was probably the first time I had been politicized by the inadequacies of the systems and how they kept people poor. I grew up in a great place to be confronted with these things at an early enough age that I took it very seriously. At the age of about 25 I quit doing organizing; that was consuming my life and I had no idea who I was. I taught high school math for a while—for a year—in a small rural community in Missouri. And so I learned about poor whites in the Ozarks and the rich German farmers, and here we have the same problem between white groups, between [poor] whites and whites with some affluence.

What do you mean that you had no idea who you were?

It was consuming my life. It was very rewarding because I was learning a lot but I was really frustrated because a lot of what we did would peter out. It would be a band-aid for a while and then I saw that the real problems needed to be addressed by people with real power and they weren’t interested in that. And it was getting dangerous and I just wanted to relax and see who I was and what I wanted to do. I still feel guilty about that situation.

In terms of leaving it?

Yeah. When I began to make films I thought, well, I’m not gonna make political films because if I wanted to do politics I should go back to that grassroots level and see what would happen. Slowly, those years of experience of being involved kept getting back into my head, so now there’s always politics in my film. Hopefully not in a dogmatic way where I tell you how to think, but I do ask you to think. I think my films are maybe overly subtle at times, but maybe not always.

That’s what I really like about your films. They force you as a viewer to connect the dots, and because you’re not actually directly explaining stuff, sometimes I’m inclined to think about my own experiences and relate them to what I’m seeing.

My hope is always that if I have an audience of 30 people, they see 30 different films. I ask the audience to participate with the film and you can only participate through your own self, through your own beliefs.

I remember reading that with 11 x 14 (1977), when that was first screening at New Directors/New Films, it showed twice. The first time, people left the screening early, and then the second time you had to explain to people that this was a non-traditional film and fewer people left.

I vaguely remember that. What I remember most, though, is that when it premiered in Germany, I had a huge audience and about two-thirds of the crowd left. And then the third that remained had stayed for the discussion and that was quite wonderful. When the film was restored a few years back—like 40-some years later—I showed it at the same theater and it was packed and nobody left. I thought, well, my audience caught up with what I was doing (laughter). It was a really great discussion that time too.

Why do you think people nowadays are less likely to leave?

I’ve shown my films so much in Berlin that they know my work. They know what they have to give to get from it. In the early days, Warhol had been doing longform films like Empire (1965) but they weren’t really being shown to large audiences.

Do you think something’s lost with viewers not being surprised by what they’re going to see? Audiences now know what to expect.

Well, there are still people who don’t know, but a bigger majority know what I do and come to see if I’m doing the same thing again (laughter) or if I’m adding to it. It’s interesting because to have the experience of watching a film and actually giving to it, and working hard for an hour and a half, and then not being sure what it is yet, and then maybe a week later still thinking about—that’s a pretty wonderful experience. And that is lost because they know they’re gonna have to work hard, so it makes it easier for them to watch because there’s a loss of confrontation.

Do you remember the first films that had that effect on you?

I’m thinking of the first time I saw [Michael Snow’s] Wavelength (1967). I somewhat realized that there was this quasi-narrative of someone dying in the room but that it wasn’t the story at all—the story was the film stock, the colored filters, space, and the hiding of the narrative, which disappears and is kind of destroyed by the elements of the film. But I didn’t get that right away. It was like, “How do I watch this?” And maybe some early [Hollis] Frampton films too. Those were the two filmmakers who inspired me the most because their films were so conceptual and they made really decent images too; I could look at them on two different levels.

Obviously your early collaborative work with Bette Gordon was more on that conceptual side. How did you first meet her?

She was a student at Northwestern—I think she was a fourth-year undergraduate. I had just been teaching math and I lost my job. I got fired because I was doing organizing against the war in a small junior college in Upstate New York. The head of the school was the head of the local John Birch Society, so he hated me immediately and fired me. At that time, I had been making some films with an 8mm Bolex and I bought a 16mm Bolex when I was teaching. After I got fired I thought, I can’t get another job, this guy’s gonna give me such a bad recommendation, so I thought I’d go back to school.

I went to [the University of Wisconsin] and there was a man, Jim Heddle, who was teaching in the film department there. He was the only person teaching production. He had studied at London Film School but I don’t think he ever finished, and he didn’t have a PhD, so he actually left before I finished my degree. He kind of inspired me. I just took one class to see what I wanted to do and he said, “I want to hire you as my teaching assistant.” So I was like, alright, I got a job again (laughter).

It was curious for me because there was no MFA in film; the film department was in the speech department—David Bordwell came on the year after I was there, so I was actually his teaching assistant for a while. It was mainly a theory/history department, and they didn’t have an MFA so I petitioned to do a double MFA between film and art and I made a really rigorous curriculum to follow. It took me three and a half years to do both MFAs and then the film school kept their MFA program, so I literally started it. And then Jim Heddle was fired and they hired another person from Iowa. A friend of David Bordwell’s, Joe Anderson, came to teach production and was doing research on how the eye looks at images, but he knew nothing about film production, so I ended up teaching the film production classes as a graduate assistant. Although his name was on it, he didn’t even come. I think at one point I was my own student (laughter). So I studied film but was kind of self-taught since I was teaching the courses I was supposed to be learning from. But I learned a lot from David Bordwell, too, but maybe more about enjoying films than making them.

What sort of things did he say?

The course I was a TA for was Introduction to Film and it was open to the whole university—it was a large survey course. He was very pragmatic in defining what films are, breaking them up into different categories, and studying the mise en scène and the plot and all these things. I never thought of films in those terms and I found that way of thinking quite conservative, but it was still helpful for me because it filled a big hole in my education.

With your experiences as a teacher, both with math and as a TA in these courses, do you feel like there are pedagogical tools that you employed that made their way into your approach to filmmaking?

Oh that’s a hard question. I’m sure there are but I don’t know if I can make a list. The way I teach now is I really don’t know what I’m gonna do when I go in. We start with something and I try to demonstrate a creative process about how one idea can grow and lead to another. My classes are best when I don’t really have a plan and we start with a few ideas, people say things, and then I say, well you’re taking us in this direction, maybe we should go there. It kind of demonstrates a creative way of thinking, and that can be applied to almost anything. When I think about all these film schools and art schools producing filmmakers and artists with no real place for them… if we’ve done our job right, we’ve taught them how to think creatively and that can be applied to any field. That’s what I’m more interested in—that model of thinking and how to keep it moving. In my classes, I try to demonstrate that and do it through their own ideas of how they’re thinking about something, how something that could be real oddball might be the real direction to go. And then something opens up, or maybe something closes down and it turns out to be nonsense (laughter).

That’s good. I think having that looser structure is important because students can take an active role in the learning process.

It’s interesting now because 60 or 70% of the students are from Asia. Because my school is so expensive, a lot of them have the affluence to come to the US and study. They have rather good education in China but I’ve found that the education has been really formalized, so they aren’t used to thinking and developing something like this. They’re usually getting stuff and learning from that; they’re not used to being confused. This may sound almost racist to think of a culture being defined that way but I find that’s true; at first they can be very frustrated with me, but when they get it, they get it. They realize that their education taught them something and that they can go beyond what they were taught. That’s what I’m trying to get at—how do you get beyond what you memorize? And with the facts that already exist, what can you add to that?

That rings true for the experiences I’ve had. I’m Korean and I always think about the piano lessons I had throughout my childhood. They were so rigid, and my teacher—who was also Korean—was only really interested in having me learn a specific piece, mastering it, and then moving on to the next one. There was basically no theory taught for whatever reason, and definitely nothing related to improvisation or personal expression or any conversation beyond what something should sound like.

All the fundamentals are really important—I don’t want to belittle that. But fundamentals can also confine you in a way where you’ll need a door opened up to get you past them.

The method of creative thinking that you mentioned is something that defines your entire career. With every film, you end up seeing a trace of it in a later one. Even with Michigan Avenue (1974), there’s a scene in 11 x 14 with the lesbian couple on the bed that seems like it came from that. And then that film led to One Way Boogie Woogie (1977), and so on. What’s interesting to me is that you use some footage in 11 x 14 that shows up in One Way Boogie Woogie, and you’ve done that across other films too. Is that something you had to wrestle with? This idea of reusing footage may seem like a bad move for a lot of artists, like you’re being lazy or something.

I’d started really early—I made 8½ x 11 (1974) and then 11 x 14 came out of that. When I finish something, it’s not exactly finished; it makes me think about new things. Why start something completely different? Why not take a little bit of what I had before and grow from that? And then as I got further into my career I started to see how things had changed in 27 years, so why not go back and revisit what I did 27 years ago? And then it becomes about time and change and what causes those changes. I don’t give solutions but I have those questions, and that’s part of the way the world exists; we get older and things change.

You’re gonna be back in Milwaukee soon because of the exhibition with Sharon Lockhart. You grew up in Milwaukee and have been there throughout your life several times. Obviously it’s changed, but what changes about Milwaukee stand out to you?

Well it’s vastly different—it’s almost completely disconnected—but some things haven’t changed. There are still a lot of poor people in Milwaukee and a lot of the industry that supported the lower-middle class or middle class people—those jobs are gone. Those people even moved away and became part of the lower class. As it happens, with capitalism the money rises to the top and at some point the pyramid’s going to explode. We can’t have a few people having all the money—t’s a monopoly, and the game ends, then. But with the pandemic and environmental problems, it’s more of a global problem than just what’s happening in Milwaukee.

I have a friend who I went to high school with, who I played baseball with, and he just phoned me. He wants to make a film in Milwaukee and I’m gonna meet with him next week, but I won’t be able to do the film he wants to do. He wants to look at what’s changed from when we were there in the ’50s and ’60s. It sounds like a great film but he wants to do interviews and I don’t have the time; it’s a very ambitious project. He wrote a treatment and sent it to me and it was quite extensive what he’s talking about, especially about race and the working class. I think it’ll be a great film.

You’ve reused footage or have remade films—you had Easy Rider (2012) and Faces (2011), and then you have your new film TEN YEARS LATER (2022) which is a sequel to Nightfall (2012). And then with Two Cabins (2010) you rebuilt these actual cabins by Henry Thoreau and Ted Kaczynski. How important is accuracy to you in all these processes?

Well, it’s impossible to recreate something exactly. I’m interested in the change that happens when you create something, but I’m also interested in what I learn about the thing I’m copying from through the process of copying it. For example, if I’m doing a painting by Bill Traylor, who was born a slave and started painting at the age of 79—he was a giant of a man with big very fingers and doing things that were very delicate. By seeing how difficult it is for myself to do that, I start to get a better feel for what the work is, how it was produced, and what that person may have gone through to make it. The interesting thing is when I started making Traylor drawings, I didn’t put it on the page in the same way he did—I wouldn’t have the same negative space around the image, and it wouldn’t have the power that his works had. I speculated that he knew how to put an image on the page and he liked to use materials that had flaws in it—a rip or a bend—and then he’d draw around that so he’d actually collaborate with the flawed material. I thought that was really smart.

And then there’s just what happens when you translate something. You absolutely change it completely even though it may look similar. I’m not interested in making a forgery, I’m interested in the translation, and that’s really apparent in Faces or Easy Rider. They’re nothing like the original films, but the translations of them suggest they came from them. For the remake of [Dennis Hopper’s] Easy Rider, I looked at all the backgrounds and didn’t look at the people really; it’s interesting to look at these places.

I thought Faces was interesting because it came out around the same time as your portrait films, like Twenty Cigarettes (2011) and After Warhol (2011). There’s always something great about being confronted with a face for that long, and with Faces there are these film stills and you get a sense of the materiality. And then you have TELEMUNDO (2019) where we see your face and Sofía Brito’s face, and you’re both watching something else too. Each of these films provide a new avenue to think about what faces can signal and mean with the tiniest of movements and suggestions.

Faces isn’t just stills—it’s clips that have been slowed down. For that film I made a time analysis of the [Cassavetes] film. Gena Rowlands was in it 30% while the two other actors were in it 45%. I thought, I have to find a face from each of those actors. I’d look for a close-up of a face and it might be 10 seconds long of it turning—it might just be staring forward so it may look like a still—and then I’d slow it down so that they’d have the same screen time. All the scenes are the same exact length and the actors have the same amount of screen time. Sometimes the actors are on the screen at the same time so I had to do some manipulation for how long they were in the scene. I like the idea of literally making the film about faces because I didn’t think the original film was about faces at all—it’s just about a bunch of really ugly people (laughter).

Can you talk about TEN YEARS LATER? Where was it originally shot?

It was shot up in the Sierra Nevada, about 10 miles up from where I had the Two Cabins project. I filmed that 10 years ago and the original was about 1 hour and 40 minutes long. We had this huge fire; we’ve been having huge fires because the pine bark beetles have been killing all the trees and there were always dead trees—there was always fuel. There was a lightning strike and it burned at least 70 miles long and 10 miles across. It burned right to my little town, actually. We thought we were gonna lose the whole town but the fire department started backfires, which helped. And so it burned through really heavily where I shot Nightfall. I thought, well I have to do daybreak now. The camera’s in the exact same location but it looks like a completely different space.

I like how you have Nightfall in the first half of TEN YEARS LATER, and then the second half is this new footage. Were there any changes you didn’t expect while refilming in this location?

The experience was totally different. When I shot it the first time, I went up in the light, I set up the camera, and I waited for an appropriate time to start the camera. It was really quiet. I actually had a huge confrontation with a huge rattlesnake—this rattlesnake watched me for a long time and when it finally got dark, I got in my truck because I couldn’t see it anymore. That was kind of a fun experience—it was playful! I wasn’t worried about him because they don’t attack unless you give them a hard time.

When I went back [for TEN YEARS LATER], I went during the day to find the exact spot. I took my camera, I made the frame, and I marked the ground where the tripod should go. I went away and I came the next day in the dark to set up. I couldn’t see what the frame would be because it was dark, so I just turned the camera on. I’m not afraid to be out in the wilderness but it was very creepy to be in total darkness, and the soundscape was totally different—it was much spookier filming it. Animals were starting to come back; there were some birds. [This section of the film] starts in the dark so I don’t know how soon you realize that this is completely burned, and maybe there should be some indication that it’s the same place.

I don’t think that’s necessary as the title indicates that.

Yeah.

Are you the sort of person who likes to simply enjoy listening to the sounds around you? Like even here right now?

Oh yeah, of course. I helped make a film with Martin Beck a few years ago about this music that was played by David Mancuso. He died a few years back but he held these big parties that were by invitation only in Lower Manhattan during the 1980s. On June 2nd, 1984 he held the last party there because of a number of things that happened—AIDS was in high swing at that point, vinyl records were going to digital, and property values in SoHo were so expensive that he had to leave. He moved to Brooklyn after that. This last show he did was 13 hours long and my friend Martin Beck did this research to find the playlist. He bought all the records and the same sound equipment and we filmed those records, so it’s a 13-hour film.

I learned that David Mancuso wrote this beautiful thing about when he was a child. He was really attuned to the sound changing at morning and at night, and could feel this change of soundscape that would happen and disappear. So when he played records and did these 13-hour parties, he would ease into what they were doing, and then it’d get high energy and the crowd would give him vibes that he would respond to, and then later he’d calm and slow things down. This whole pattern, this 13-hour “Last Night,” was based on what he experienced from listening to things in nature. I thought that was absolutely brilliant.

Do you have any early memories of intently listening to nature yourself?

No, I was just lucky that when I was young I spent a lot of time outside because we could go wherever we wanted to. I also had an uncle who would take my brother and I and his son on hikes in the middle of nowhere. I think in TELEMUNDO I tell a story about when I was young and felt both hot and cold at the same time, and that memory of having a cool wind and a hot sun—I think about the first time I felt that whenever I feel it again. I didn’t realize how brilliant that observation was, but I had it. I didn’t note it down as being important but in retrospect I could see that it was, just having these experiences that made you understand what sound is, what image is, what light is.

Throughout your filmography, I like how you sometimes try to capture a specific time period. In your two United States of America films, you repeatedly use the Minnie Riperton song “Lovin’ You.” And in the new one, you reference the places that are in Johnny Cash’s “From Sea to Shining Sea.” Do you spend a lot of time listening to music? Do you spend a lot of time thinking about how they’ll be used in your films?

I still listen to music a lot, especially in the car, but I used to do it a lot more. I think I stopped once record stores started going out of business. I loved looking through vinyl. Even when cassette tapes and CDs came out, I enjoyed looking through those, but once it all went online, well now I have a friend who can steal me any music I want, and I’ll get a package of new stuff. I don’t listen to music as much as I used to, but I still listen to a lot of older things—jazz and singer-songwriters.

Do you feel like any of your experiences listening to music influenced your work? You mentioned Snow and Frampton for filmmakers, but were there any musicians?

Well, I was really affected by early Dylan. And once I learned about him, I went to the more authentic sources like Lead Belly. And then I listened to all the stuff that was popular—Joni Mitchell and such. A lot of jazz too.

I wanted to talk about American Dreams (Lost and Found) (1974). That same year you had an installation, Pascal’s Lemma (1974). Something that always fascinated me about the former is that you had this scrolling text, which also appears in some form on Pascal’s Lemma, and it would appear again in North on Evers (1991). What really excited me when I first watched American Dreams was that I felt so overwhelmed by all the stuff I had to keep track of. Compared to your other works, I felt like I couldn’t take in everything that was on the screen. What was the thinking behind having this scrolling text in your films?

Well it started with American Dreams and that started with my daughter liking baseball. I played a lot of baseball and we went to a few baseball card conventions together. She was collecting baseball memorabilia, and she still goes to spring trainings to get autographs. I bought a few Henry Aaron [aka Hank Aaron] cards because he was my hero when I was younger, and then I got obsessed like she did and I wanted to get every Henry Aaron card made during his career. I took about four years to buy all of those. And then I thought, oh I’ll make a film with them. I filmed the fronts and backs of the cards and each one would represent a year. Then I thought I’d use a political speech for the front of the cards and a popular song that was in the Top 10 for the back of the cards. I had that together and I thought, oh it’s just too cute, it needs some kind of counterpoint.

I don’t know what came into my mind, but I thought I would write a diary for Arthur Bremer, who was from Milwaukee and shot [presidential candidate] George Wallace. I knew his whole story, so I went to the library to do more research on him so I could write a diary, and the first thing I found was his diary, which was actually published. I was like, well this was easy (laughter). I didn’t have to write a diary! I was dumbfounded. I was kind of looking forward to making up a diary. Then I wrote it out and it took about a month to animate it through the bottom of the frame—1/16th of an inch at a time. I built a really funky animation stand to do that. That’s all shot on the same animation stand where I’d shoot the cards, and then I’d rewind the film and animate the text through it. And I did one roll for each year, so I had 25 rolls—they weren’t all quite 100 feet each—and then I spliced them together.

Is there a reason you had scrolling text instead of just words onscreen as a big block of text?

There’s something about scrolling text that has an urgency, like on a TV set when it comes to warn you about a tornado. I thought it had a particular meaning. I sent it to a friend of mine to watch and he wrote back saying, “That text is amazing! It’s like it was being squeezed out of a toothpaste [tube].” I thought that was such a great image (laughter).

How did you decide to do an installation on a computer for Pascal’s Lemma? How did that come about?

I visited a friend—I was a visiting artist at Vanderbilt and a friend was teaching there and he did really wacky artwork. This was in the early ’80s and he had a computer and a young daughter. She wrote a program where you answered questions like, “What’s your favorite color?” Depending on how you answered, it would ask a different kind of question. I thought that was cool. When I did math I learned [programming language] Fortran, and I wrote my master’s thesis using it. I thought, I’m gonna buy a computer. So I bought one and the first thing I did was Pascal’s Lemma. To do a narrative story on the computer that was somewhat about the computer and technology—and at that time the Soviet Union and the US were kind of zero and one—it was just playful. All of it was with equations, so all the drawings were made with equations. It took me nine months to write the program and it’s just in BASIC, a simple language.

Were you really interested in Pascal’s life? There was of course this huge math phase and then he became an extremely spiritual person.

He was quite brilliant and I liked that he almost discovered calculus—he was within one step of it. And he worked with hydraulic stuff and invented the syringe. But then he got all wacky with the religious stuff.

Did you have a religious upbringing at all?

None. My father didn’t talk about it but I had the feeling he thought it was a scam. My mother wanted to go to church so we went a few times around Easter, but I’ve been in a church service maybe three times in my life, and for a few weddings. I got married in a church.

You mentioned the rattlesnake story earlier. What’s the most dangerous situation you’ve been in as a result of making your films?

There’s a lot of them. I used to always be trespassing and shooting without permission. I’d shoot fast and get out of there, and I always felt uncomfortable. I did a shot here in Chicago for PLACE (2020) and the shot in Chicago is of Joseph Yoakum’s storefront. It’s in South Chicago, in an all-Black neighborhood near where Farrakhan has his temple. A friend, we did this trip during the pandemic and he helped drive. We were in this alley and a car came through the frame and it was missing its front right wheel and the rim was digging into the asphalt, shooting sparks. It was going about 30 miles per hour and the airbags were deployed and hanging out the windows and there was a car in front of it going fast, so I don’t know if it was chasing that car, but there was also a car behind it that was chasing it.

There was an elderly Black man who walked in the frame and he was completely shocked to see two white guys in the alley with a camera, and he just kept going and didn’t say anything. And then we heard about 20 gunshots about a block from us. I was doing 10-minute shots and I got out of there after, but it turned out that my camera’s on-off switch was malfunctioning. I only got three minutes of that shot so I had to stretch it to 10 minutes. It didn’t have the car in it, but I wasn’t gonna use that anyway because it was so dramatic. We were really scared there, but I think it was more our own paranoia than any real danger.

I always appreciated how much you involved yourself in the process of making your films. Of course Used Innocence (1989) is the big one with you having your own letters for Bambi [aka Laurie Bembenek]. How’d you decide to insert yourself into a film like that?

I actually had a whole stack of many more letters than what’s in the film. I was making the film and I met with someone who used to work with [filmmaker] Barbara Kopple. I can’t remember her name. But I was showing her the film and I happened to have the letters and I asked if she wanted to see them. She said, “These are so amazing, you should put them in the film.” And I thought she was right because it was so pathetic that she was in jail for murder when I was the pathetic one. I’ve only shown the film like three times and I haven’t shown it since. There’s somebody that’s mentioned in the film that doesn’t want it to be seen. Occasionally it gets put online and I’m a little worried about this person.

I’m sorry about that. Do any of your other films have that situation?

No, not really.

And then of course you got really involved in North on Evers. I remember reading that Medgar Evers’ death was a radicalizing moment for you. Do you remember the sort of things you were feeling when you heard the news?

This was around the time I was visiting Groppi and really seeing first-hand what the differences and similarities were between white and Black poverty. The racism on top of it makes it so much more difficult.

Is there a specific thing from having made North on Evers that resonated with you?

I made a motorcycle trip, but I didn’t have a camera with me, and then the next year I decided—because I had written a long letter to a friend in Paris about it—that it was such a good narrative. So I thought I’d redo the trip and shoot portraits of people and landscapes and do the same kind of scrolling text. Even though I knew how much of a hassle it was, I wanted to do it again. So the film came out of having such an amazing experience, and also because I wanted to ride again (laughter). I was addicted to riding a motorcycle.

Do you still ride?

I just sold my bike in the spring to make room for the show I have in my house in Alberta. It was taking up a lot of room in the studio space. I hadn’t ridden it for 10 years and I thought it was time to get rid of it—it needed a lot of work to get it to run again.

Around the time North on Evers came out, you mentioned in interviews that you make films for two reasons. The first was to take you to places you’d want to spend time in and get to know, and the second was to understand your own life better. Is that still true?

It’s always a search. I mean, this was a literal search with a bike.

What sort of things do you feel like you’ve learned about yourself more recently, like in the past 10 years?

I learned that my knees don’t work as well (laughter). My body starts to give out and it’s frustrating to not be able to do everything. I understand that youth is wasted on the young at this point (laughter).

Are there specific things you’ve wanted to do but couldn’t because of your body’s limitations?

What I worry about most is my own maintenance. Painting my house, that sort of stuff. I enjoy doing that. I grew up in a house where we didn’t hire anyone else, we did all that kind of work. I have that in my blood. I enjoy fixing something when it’s broken. Right now I have a plugged bathroom sink and I started to take the pipes out and of course, one of the plastic things immediately broke. I replaced that but I haven’t fixed the plug (laughter). I don’t enjoy it until it’s finished and I have the water running.

Do you feel the same about making films? Are you most satisfied when it’s done or do you enjoy the process of making it just as much?

I like the whole process but I like editing a lot. The hard thing is to travel and show things. Even though I meet a lot of interesting people and it’s fun, it’s the hardest part. And now I make so many films that I don’t even show most of the films. USA has shown a lot but all these shorter films haven’t.

Recently you also made glory (2018), the film made out of the security cam footage. Did that screen anywhere?

That was installed at the Berlin Film Festival. That was never shown as a film, and I don’t know if I would.

I feel like that’s one of your most blunt films regarding your thoughts on America.

It’s an interesting film because it was from some cam out on some station in the middle of the ocean, like 30 miles from the shore. It was being broadcast as some traffic cam. I searched it because I was interested in the hurricane that was approaching and what the ocean was looking like. Thousands of other people searched for it too, and then it became a thing that the flag was ripping. A lot of people wrote in, “You can’t show the flag being destroyed!” So there’s a point in the film where the camera zooms to the side, and once that happened, more people wrote in, “You have to keep the flag to show how strong it is!” (laughter). So after a half hour they zoom back and this was being dictated by a live audience—they got the shot to pan over and back. That’s the best part of that film but nobody actually knows that. We tried to buy the flag. I wanted it for the installation. We were gonna see if we could buy it so we wrote them and they said they were gonna auction it off to raise money for hurricane victims, which I thought was good. We were gonna go up to $5000 or something but it went up to $8000 so I didn’t get it. I bought a flag and aged it and made one that looked exactly like it (laughter). I didn’t put it in the installation though because I made it after it was shown.

I like knowing you still did that even though it didn’t get used in the installation.

I’ll maybe show it at some point.

I also like that your filmmaking makes it seem like you’re just having fun.

I have to, otherwise it’s a job.

Which is funny because now I’m thinking of Maggie’s Farm (2020), which was shot at your school [CalArts]. What was their response to the film?

I don’t know if they ever saw it, actually. That film didn’t show much either. It showed in Europe.

At the end of the film you have “The Star-Spangled Banner” play.

Yeah, it’s from a baseball game from Lancaster, the baseball team. They don’t exist anymore; they went broke during the pandemic. There was a person singing and I found a recording of the whole baseball game online and I thought I’d use that.

You often skewer these songs about America in your work.

Yeah, it borders on being corny sometimes but you gotta take that chance (laughter).

Looking back on your films, do you think any of them were too corny or too didactic?

I used to think One Way Boogie Woogie was. When I finished it I thought it was really stupid humor (laughter). And then everyone thought it was really funny, and I thought they must be crazy. And now years later I think it is funny. It’s stupid (laughter).

Your whole career is this constant, circuitous journey from film to film. Are there any you really cherish?

I always like the one I just finish. There are ones that became very popular, like 11 x 14, Landscape Suicide (1986), 13 Lakes (2004), Ten Skies (2004). Now it seems like USA is gonna be popular. I was surprised that people liked it so much. I thought it was kind of a hard film, and it’s kind of long, but the shots are short.

I really like that it’s your biggest prankster film. You con everyone, which is wonderful.

(laughs). It isn’t meant to be that way but it can’t not be that way.

Well it’s of course also you commenting on the illusions people have about America.

It’s impossible to describe America, really.

Were there any shots that were challenging for you in terms of replicating other states?

Not really. I know California and I know the other states well, and I used [Google Street View] a lot to make sure that things would fit. And then I used a number of shots that I’ve used in other films. That was supposed to be a clue for people who know my work. People might be like, “I saw that in Sogobi (2002).”

I’m assuming you rewatched the original United States of America before creating this one?

I don’t know if I did or not. I was just surprised how popular it was when it showed on TV about two years ago. And I only remade this one because of the popularity. People were claiming that [the original] was an avant-garde success in the 1970s but it wasn’t a success at all. It showed in Ann Arbor and a few festivals, but it is much more interesting today than when it was just made because it’s now a time capsule of popular culture in 1975. And we were lucky. Patty Hearst got [kidnapped], there was the Fall of [Saigon]—there were all these news stories.

I wanted to say something—you mentioned Landscape Suicide and we talked Used Innocence. I was wondering, is there a reason for your fascination with murderers?

It didn’t start with a murder, it started with a friend dying. I was there when she died and people could have thought I killed her, so it could’ve appeared as a murder situation that I was involved with. It was a drug overdose. There was no investigation and it got me interested in thinking about life and death. Him and Me (1982) is about that stuff.

Is there anything you wanted to talk about that we didn’t get to?

No. This has been a really good interview—you know my work well.

Thank you. There’s a question I always ask everyone that I wanted to ask you: Do you mind sharing one thing you love about yourself?

I don’t know. That’s a really interesting question because I’m getting to a point in life where I’m thinking about the things I don’t love about myself (laughter). I always heard this statement, “Oh I wish I knew back then what I know now.” For the first time in my life, I understand that. I wouldn’t have done stupid things. But I work hard.

Are you 79 right now?

Yeah.

Do you have specific things you wanna do before you pass?

I should get things in order so things are easier to take care of. I keep putting things off. I need to have things labeled so people know what they should throw away and what is valuable (laughs).

Do you worry about dying?

I want to say no but at this point, it’s not a worry, it’s just gonna happen. I never thought it was gonna happen—it’s only just occurred to me (laughter). And this happened since my body has started to rail out. I need to get a knee replaced. I think when I do that I’ll feel good again.

There’s just one last question I want to ask: Given how much you’ve traveled the United States, are there any specific places you really love?

Right now, it’s right here on this porch. It’s a really lovely home and there are some really lovely friends.

James Benning’s Milwaukee exhibition with Sharon Lockhart continues until January 1st. The two have also released a book that was designed by Martin Beck titled Over Time. Despite having the same title as the Milwaukee exhibition, it is not a catalogue for the show, and more so functions as a visual dialogue between both artists with some additional text. Benning’s The United States of America (2022) is also screening twice during the Viennale. Benning will be doing a post-film Q&A for at least one of the screenings.

Thank you for reading the 19th issue of Film Show. Do some porch sitting today if you can.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.