Film Show 018: Hara Kazuo

An interview with Japanese documentary filmmaker Hara Kazuo about his decades-long career of capturing people who live on the margins of Japanese society

Hara Kazuo

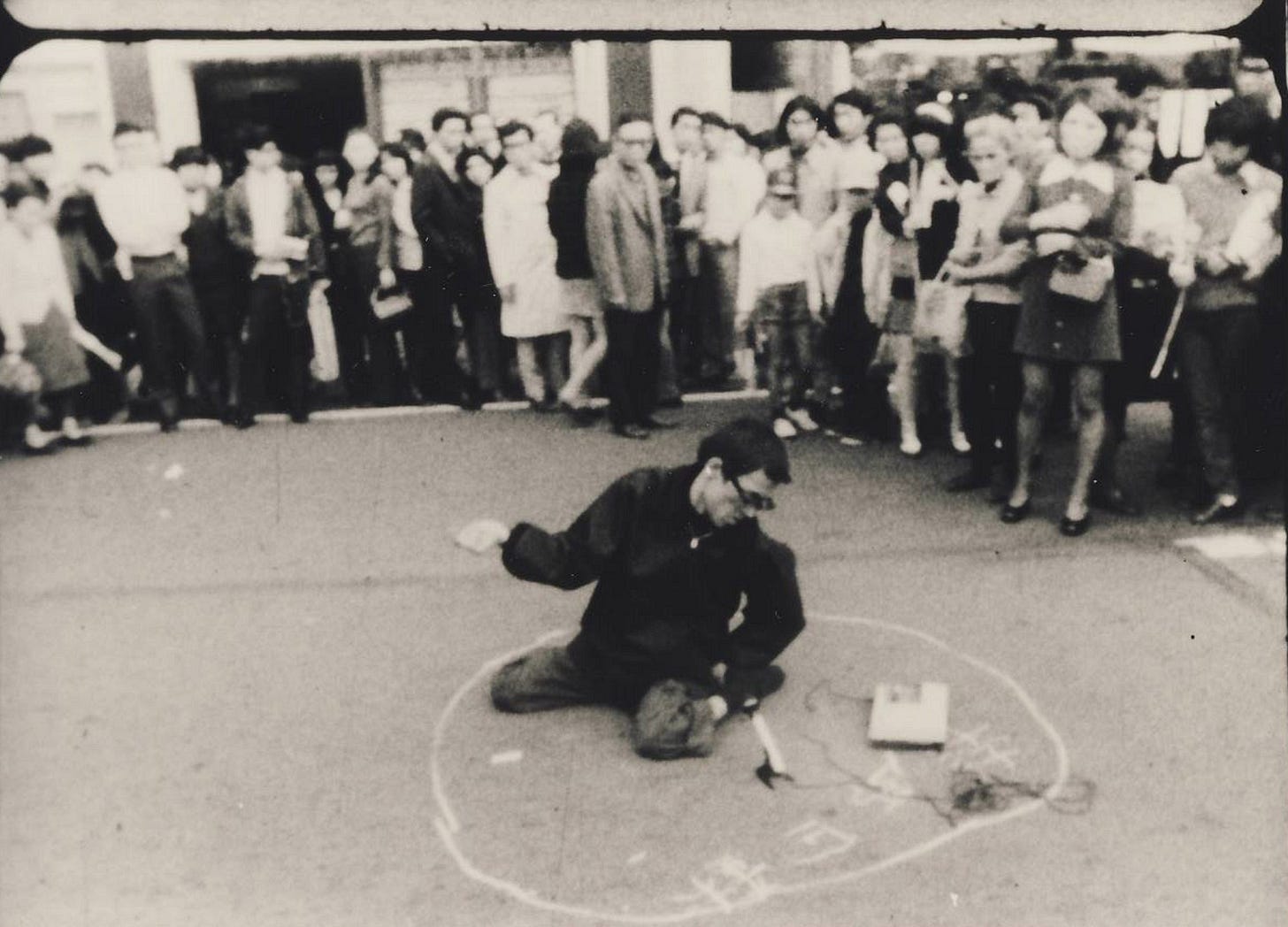

Born in 1945, Hara Kazuo is a Japanese documentary filmmaker who has spent the past 50 years creating confrontational films that question the moral values of Japanese culture, reveal a necessary anger towards the country’s various systems of power, and showcase the extraordinary and resilient people who live on the margins of society. His works fall in a lineage of films from artist-activist documentarians Kamei Fumio, Tsuchimoto Noriaki, and Ogawa Shinsuke. Hara is largely known in the West for his first films, which largely focus on individual people—Goodbye CP (1972), Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974 (1974), Emperor’s Naked Army (1987), and A Dedicated Life (1994). More recent films, such as Sennan Asbestos Disaster (2016) and Minamata Mandala (2020), have a much larger scope, focusing on victims of asbestos and Minamata disease, respectively. Five of Hara’s films can be watched on the Criterion Channel.

Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Hara Kazuo in June, 2021 via Zoom in light of Minamata Mandala’s screening at Sheffield DocFest. The interview took place across two separate days, and is presented below in two parts. Yamanouchi Etsuko assisted with interpretation. All Japanese names in this interview appear with the surname listed first. This interview is available in Japanese; that version will be published shortly.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: How has your day been? What’d you do today?

Hara Kazuo: We were working on my newest film, whose content I’m not allowed to disclose. It’s top secret (laughs). But we met a certain couple and discussed how we’d make the film with them in it.

I’m excited for that, and I understand that you can’t share.

Thank you.

Through your films and your interviews, you ask for the people of Japan—and people in general—to be angry at the injustices we see in the world. What’s the most recent thing you’ve been angry about?

There are lots of things to be angry about… let me pick some out of the many. (pauses to think). I was born in 1945, and that is when Japan lost the war and democracy was introduced into our country. I grew up with that new concept of democracy. The common belief since then has been that democracy has taken root in Japan. I would say that I belong to the generation who values democracy more than any other generation, yet nowadays I often have to wonder if democracy has really—actually—taken root in Japan among Japanese people. When you look at what’s happening in the Japanese political scene, Prime Minister Abe [Shinzo] was replaced by Prime Minister Suga [Yoshihide]. However, it seems like both of them are only acting in order to save their rights, to further their rights and advantages. It’s very, very clear. And yet most of the Japanese voters don’t do anything about it. Rather, the majority of them support the Liberal Democratic Party, which Abe and Suga head. And that really, really angers me.

I know you’ve identified with anarchism before. Do you ever trust people in such high positions of authority?

Not only do I distrust them, I loathe them.

I feel similarly. I wanted to ask—I read your book, Camera Obtrusa, and I know in it you said that your mom was the only person you could directly connect with early in your life. Do you feel like you’re a similar person to your mom? Do you have similar personalities?

Well, setting aside similarities in personality, I would like to talk about how and where we were situated in society. When you look at society, a handful of the powerful are at the very top both in terms of their position of power and economic power. And then there are the middle layers that have gradations with some differences among them. So, apart from the very top layer and the middle layers, at the very bottom there is a group of people who are the weakest and who have the least power. When I think about it, I’ve always belonged to that very bottom layer. That was how I was born, and that’s how my mother lived and gave birth to me, and then raised me, and passed away. So, I always feel I am a part of those people at the very bottom of society.

In that sense, I have very strong bonds with my mother as comrades—as kindred spirits, so to speak. I do not have a father. My mother was a concubine of a man and gave birth to me—a fatherless child, so to speak. And in order to raise me, my mother had to sell her body both within and outside of the marriage system. By that I mean she married two or three times after she gave birth to me just in order to survive, so I ended up having a few stepfathers as a result. That was for her economic survival, and not out of love. I also am aware that she had to sell her body outside of the marriage system, as well. She was somebody who lived at the very bottom layer of society, raised me, and passed away. That gives me a very strong feeling of comradery with her. And this is the feeling I always have in the core of my heart when I make films, and that is how I will keep making films from now on as well.

Can you expand on how you see a link between who your mom was, how she inspired you, and how that comes out in your films?

In a nutshell, I would say my mother has had really, really terrible luck with the series of men in her life. From my perspective as well… I mean as I told you, she was not married to my biological father—she was his lover outside his marriage, a concubine. And that guy was a monk. Because the war was raging at the time, especially when my mother became pregnant with me, my biological father felt that it didn’t look good if a monk had a concubine, so he deserted her.

After that, my mother went back to her hometown where she had an elder sister she was close to. That sister had a different father from my mother which makes it a bit complicated, but anyway the two sisters were very close to each other. When my mother went back, she was nine months pregnant with me, and it was a very serious time towards the end of the war. B-29s were raiding Japan all the time, people had to evacuate to air raid shelters. And I was born in an air raid shelter, actually. My aunt, my mother’s eldest sister, told my mother: “Look, you’re going to raise this child without a man to help you? How can you survive? If we killed this baby right now by pinching his nose and making him stop breathing, nobody would know we killed him. Wouldn’t that make it easier for you?” My mother was somewhat persuaded, but when my aunt was actually trying to kill me my mother screamed “stop!” So, through that miracle, I lived on.

In order to survive economically, my mother got married and had my younger sister. That guy was a miner—a coal miner—but he died in a mining accident. So, by then she was a single mother with two children. She had to marry again in order to survive, but that guy turned out to be a terribly violent guy, and yet they had two children between them, so at one point there were four kids in the house. But because the guy was too violent, too stingy, etc., my mother decided to divorce him, so she had to face the reality of raising four children on her own. She figured it would be impossible, so she had to give up two of them for adoption. There are many sad stories about them which I don’t have time to go into but she ended up raising only two on her own. Because it was so difficult economically, she had to live with a younger guy. But this guy turned out to be a very lazy bum. He and my mother both engaged themselves in labor work, but the guy loved gambling, so my mother’s suffering never ceased. Despite all of that she still had to please him in many ways just to keep him in our lives.

But in the end they separated. They were not married, but they ended up separating. And then she married another younger guy after that, and economically it became a bit stable and we could live more or less alright, without worrying too much about money. This guy was ten years younger than my mother, and he ended up finding a lover or lovers. My mother was of course extremely jealous and hurt. She would talk to me a lot about her jealousy and her hurt feelings. I was in junior high school at that time, my mother would describe to me how my stepfather was dating another woman, including quite raw and detailed sexual descriptions, concrete descriptions. So that, I’m sure, matured me quickly sexually. I didn’t get into any moral or typical, you know, teenager stuff that’s disapproved of by parents at all because I was so appreciative of my mother’s suffering and her endeavors to just keep us fed. I didn’t look down on her or think of my mother negatively. And I didn’t rebel against her, either. I was only grateful to her for her desperate attempts to raise us. So, I knew how dependent she was on me emotionally and I always felt I really wanted to help her and support her, but there was nothing I could do. I was still in junior high school, and the only thing I could do was to be a good listener to my mother about all her hurt feelings. So, that was our mother-child relationship. When I was twenty years old, I moved to Tokyo. I’m sorry, I didn’t answer your question straight on, but let me continue a bit.

[Hara stops to explain more to interpreter Yamanouchi Etsuko]

So, I’ll try and answer your question more clearly now. Because I grew up watching my mother really suffer and trying so hard to raise her kids, when I make judgements in my life, in making films, I always think about how my mother would react in a situation like this, or what kind of agonies she must have had in her heart in a situation like this. That sort of thing. A documentary is made when a camera is thrusted upon the subjects, and we directors try to probe for how the subjects are feeling, what they’re thinking, and bring out all the minute details of the subjects—happiness, pleasure, agony, and hatred. And that is the essence of documentary making, I believe. Therefore, my mother’s way of life, how my mother lived, has become a measuring stick when I face my subjects.

I want to ask you, since you’ve shared all these things about your mom… I’m just wondering, what comes to mind if I ask about your happiest memory of your mom?

When I was a child, my mother was still very young. She was working as a restaurant waitress. And she actually liked some fun things. Around then, there was a very popular game in town, by the name of bingo. I don’t know if you know how it’s played, Joshua.

Yes.

It’s a gambling game, and you could end up making money if you win. She was married to the violent guy I already talked about, whose family name was Hara. That’s why I took on the name Hara Kazuo. Because her life came with some pains, in order to forget about them, she would take me to town and we’d play bingo together. And you have to buy five or six cards, right? She would let me help her by holding some cards or record on the card when you throw the ball. So, I would help her with that and I spent time with her that way. And when I think of that fact, that when I was a child we spent time together like that, just thinking about it makes me so happy. I don’t know what it means, I can’t explain it. But it is like a treasure for me, that memory. And also, the first time I was in a movie theater, was when I was being carried on my mother’s back. She took me into that darkness of a movie theater, and that’s also another precious memory.

Thanks for sharing that. My dad told me that he has memories of his mom taking him on his back to go to movie theaters as well.

I see (laughs).

I want to start talking about your films now. There was [pioneering documentary filmmaker] Ogawa Shinsuke, I know his method of filmmaking involved living with the people that he worked with. And I know you sort of work differently—you don’t feel like that’s something you want to do. I’m wondering, do you feel like there’s something you gain from not being so close to your subjects?

Well, Ogawa Productions certainly lived with the subjects for the Sanrizuka series. And that method, of the production people living together, was carried into their work that followed in Yamagata. However, my generation came after Ogawa’s generation, and I felt our generation had to go beyond what the previous generation had achieved. I thought about how I could go beyond the method Ogawa Productions found and exercises, which was the way they established their relationships with the subjects by living together, spending lots of time together. And the way to do that was not to take the same method.

However, at the beginning when I decided to become a filmmaker, I did consider joining Ogawa Productions, actually. Their office was in Shinjuku, in Tokyo. And I remember visiting them at their office, and I met some of the production members. I told them I wanted to become a filmmaker. I’m not sure if I said to these members if I wanted to join Ogawa Productions or not. However, I remember thinking, “Actually, I shouldn’t join this production team” after talking to them. And that made me decide to walk down a different path. Looking back, I’m glad that I did not join Ogawa Productions.

So, as you know, Ogawa Shinsuke is one of the giant documentary filmmakers of Japan. Therefore, he was not somebody you could ignore, but we had to think of some ways to go beyond him and his works. Ogawa Productions really focused on groups in making their films. In terms of themes, also. And I thought about what kind of perspectives or themes I should choose to go beyond their works. My conclusion was to focus on individuals and really dig in deep about their individual way of being. And that’s how I made Goodbye CP as well as Extreme Private Eros. With Goodbye CP, of course, I did not live with them, but we had repeated discussions as to what kind of film we wanted to make. And not just the theme, but how to make a film. As for Extreme Private Eros, I would say that it was a pioneering work in terms of stealth documentary. I would like to think I spread that way of making documentary films through that work. So, it wasn’t just the theme of the film, but how to make the documentary was another agenda. And that was the antithesis that I came up with to Ogawa Productions’ works.

Thanks for sharing that. I did not know you were initially considered being a part of Ogawa Productions, that’s very interesting.

(laughs)

Earlier you said that you loathe people in power. I’m wondering, how do you reconcile that with the idea that you, when you’re behind the camera, are the person in power?

Well, I know there is that way of thinking, that the people behind the camera have the power. But I’m not sure if I agree with that one hundred percent, at all. I can see what they mean by that. However, in reality, that is not the relationship I necessarily have with the subjects. Because sometimes, the subjects could, from their very egoistic reasons or motivations, say “I’m gonna quit. I’m not going to appear in your film. Let’s stop this.” That happens and that really throws us into a panic, right? Because we’ve already taken out a loan, we’ve been shooting so much, we just cannot stop making this film any longer. So, at a time like that, we end up having to be somewhat subservient and flatter the subjects enough to persuade the subjects to stay on the project. So, at a time like that, I definitely do not feel we have the power.

When I put a camera in front of someone, I really do not feel as if I have power. Because, during the shooting, the cameraperson is constantly making choices as to how to shoot, what angles, what moments, etc. And then, after that, we edit the footage to turn it into a film, as you know. While I can see how some people would call the filmmaker as someone with power, as I shoot or as I edit, I’ve hardly felt I’ve had the power. Because, when I look at the footage that I’ve shot in the editing room, I get constantly asked by the footage itself: “Why did you shoot this?” “Why are you editing it this way?” “Why are you connecting these images this way?”

Again, I am being questioned rather than enjoying the power as you described. And once the film is completed and once it’s screened, then this time we get basically judged by the audience. The audience has the freedom in interpreting what they see in whatever way they feel like interpreting or understanding—which is the merit of documentaries, I would say. There’s nothing negative about it, that freedom that the audience has. And that is the essence of any kind of expression, right? Once you put something out there, it can be interpreted in whatever way the receiving end can choose. So again, I feel like I'm being tried and judged in a trial of some sort. So, I’ve hardly felt like I’m in the position of power. Do you understand?

Yes, I understand, that makes sense. I’m a really big fan of Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974 and I feel like a lot of the film makes sense after you talked about your experiences—the experiences your mom had. I know you find the film to be embarrassing. In a recent interview you said you haven’t really watched it recently. I’m wondering, in making that film, what do you feel like you learned most about yourself?

This may sound somewhat banal, but sometimes I jokingly say my life was determined by that. It sounds like a parody of a TV program or something, to speak like this, but anyway I feel like my life has been determined by my various encounters with women. In a positive way, I really feel strongly that my life has been steered by all these women I came across in my life. And the first turning point of my life was my meeting with the protagonist of Extreme Private Eros, Takeda Miyuki.

And by having a relationship with her, I could clearly see the direction I should go in my life. She definitely played that role, of showing me that. And after that, I’ve been making films with a partner, Kobayashi Sachiko. When I first met her, she was this woman who loved films, who came from a rural area. I used to think she may not know much or something like that, but it soon became very clear that she had a much more visceral sense, or more sense about films and filmmaking than I do. So, I’ve been learning from her, humbly. That’s another example of how my life has been led by a woman in my life. And other meetings with women have always had a very positive impact on steering my life. So, when I think about that, I go back to my mother, because she was the first woman I met in my life, right? And of course, she has had such an impact, as I told you, on my life.

Interpreter Yamanouchi Etsuko: So Josh, after that I couldn’t help saying to director Hara, “Oh, you’re such a feminist.” and he said, “Rather than being a feminist, I suffer from a mother complex.” (laughter).

I want to ask, I haven’t seen anyone ask this question before, but I know you were a cinematographer for Matsui Yoshihiko’s Pig-Chicken Suicide. Can you talk to me about making that film, and working with Matsui specifically? What was it like?

Well, I’ll share one specific experience with you. Director Matsui asked me to take a certain shot and to do that, you definitely needed a telephoto lens. However, he said “Well, you have to give me a close-up of that,” which would've been impossible, right? And when he gave me that conflicting request, I felt, “Does he really know how to make a film?” Of course, that didn’t make me look down on him or respect him any less at all, but it gave me a big challenge. That’s one memory I have.

Thanks for sharing that.

Was it difficult to understand? (laughs).

No, it makes sense. You’ve talked about how your earlier films focused on a specific person going against societal norms and then your newer films are about regular people. You have stated that you consider yourself a weak person and that these people that you film have helped you gain more courage, be more confident, and help you grow. I’m wondering, however, with these newer films where people are mostly suffering and are regular people, do you feel like you’ve grown as a person from seeing them, from filming them, too?

Yes, in the earlier films that I made, I’ve always chosen people with a very strong energy that was just flowing out of them. At that time I was thinking, “This world is full of poor and suffering people at the bottom of society” and in order to change this you have to have a huge change, and you have to live in such a way that can bring about that major change. You have to go against the power. You have to polish your ability to resist the power. I used to think people who were just living their own little lives were no good, and I didn’t want to live like that. In my twenties, I used to think my big agenda was to train myself to be strong so that I could be a part of that change. My method at that time was by shooting such strong people with a strong energy and a strong personality. That’s how I carried on until I filmed The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On as well as A Dedicated Life. But when I made A Dedicated Life, it was around then when the Japanese emperor’s era changed from Shōwa to Heisei, right?

Since then, I just couldn’t find anyone like Mr. Okuzaki, who is the protagonist of The Emperor's Naked Army Marches On, with that kind of incredible energy. And I spent the next ten years wondering why I couldn’t find anyone like Okuzaki. Why is it that I don’t see anybody like that? And then, after ten years of thinking about it, I realized the answer was because the times had changed. We are in an era where there’s no space for a strong personality like that in today’s society. We are living under a social system that has made it much less free for such people to live. As a result, there is hardly anyone who can live like Okuzaki did. So, at that time, I felt so down and depressed thinking my filmmaking was over.

But, it was around then when I was invited to make the following film, Sennan Asbestos Disaster. Because I was feeling so desperate, I said, “Okay, I’ll do it” without even looking into the background of the theme. So, I went to Sennan to meet these people and they were as ordinary as they come. And I thought, “Oh shoot, why did I take this on? These people are so ordinary.” But I’d already started to shoot, so I couldn’t stop this project. But I kept thinking to myself, “could this possibly be turned into a film?” because these people, the subjects, kept having meetings with their legal counsels. As you know, the film depicts the court case process, right? So, it was so frustrating to watch them talking endlessly with these lawyers. I kept thinking to myself, “If Okuzaki was here, he would be doing something, he would be taking some kind of action.” So, during the whole shooting period, I was inflicted with this anxiety thinking, “Could this be turned into a film?” And then, during the editing too, I kept worrying about it. “Could this really be a film? Do we have enough to make it a film?” And then, after the film was finally finished, I was still full of anxiety thinking, “Is this really interesting? Is it worth watching?”

The first time it was shown to an audience was at Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival, in their competition category. After the screening, 30 or 40 people came and found me in the lobby and congratulated me and said “it was so good” or “it was so interesting.” So, that was when I finally realized that the film was on a high enough level to be called “interesting.” It finally gave me some confidence. So, making that film, Sennan Asbestos Disaster, showed me how to make an interesting film by shooting ordinary or regular people. And Minamata Mandala was being shot at the same time, so the root is the same. In Sennan, the regular people who never formally dreamt about going against the power were thrusted into this struggle. And they repeatedly ask the power to listen to their stories, but they were never afforded that opportunity. So they had to keep fighting in the court cases, and they won their victory at the Supreme Court, finally. So, it is a story of their growth.

Before I started shooting Minamata, director Tsuchimoto [Noriaki] had already made lots of films, as you know, about Minamata. When Tsuchimoto was shooting, the Minamata disease movement had strong energy. The patients as well, they were very, very sick, but they had so much energy and charismatic power as people, and they were taking the leadership. So, in Tsuchimoto’s Minamata series, you feel and get lots of energy and vigor from it. However, when I started to shoot Minamata, that movement had lost its propelling force because of the lack of a fundamental solution offered by the government. People in general even started to think that the Minamata disease was now over or they settled.

So, I wanted to find out what was happening with the people involved in the movement, and how they were living, if they’d also more or less given up on the success of the movement—I had all of these questions in my mind. And I felt I had to persuade that as a theme. And that is what I hope is different about my Minamata Mandala film from other films that have depicted the Minamata disease issue. And usually, in a social movement, you are working towards the happiness of the public, right? But, in this reality, in Minamata Mandala, there are some people who are doing it for their own personal happiness or their family’s happiness. And I’m not showing them to criticize them at all, I am showing them because the lack of interest on the part of the government to settle this issue, fundamentally, brought on this situation and pushed such people into that kind of corner. And that’s a very, very difficult corner to be in, and I really wanted to depict it. And that’s what makes Minamata Mandala different from Sennan Asbestos Disaster, as well. So, that kind of dilemma I just talked about regarding the present situation of Minamata is the common dilemma shared and lived by the people at the bottom of the society from which I come myself. And that’s what I wanted to depict, and that’s what I felt I had to depict. And these two recent films gave me an opportunity for that.

[End of Part 1 of the interview]

With A Dedicated Life and The Many Faces of Chika, the former had many aspects of fiction and the latter was an explicitly fictional film—I’m curious, has your time spent making films this way impacted the way you make your more recent documentary films?

First of all, I want to talk about The Many Faces of Chika. You know, when you make documentary films there are certain rhythms or feelings you go by when you create scenes or the sites of filming and I felt I wanted to sever all of that when I was making Many Faces of Chika, and I thought I did, but in reality I don’t think I did. I brought all of those rhythms and feelings from documentary filmmaking into fiction. Therefore I think it was a failure in that sense. There are certain ways to create filming sites when you are shooting a fictional film and there are a different set of such when you are making documentary films. Many argue that fictional films and documentary films are one and the same, in their essence, and I basically support that way of thinking. However, having said that, there are certainly some differences between the two and I thought I consciously switched from documentary mode to fictional mode, but I didn’t. I failed at switching between them. So to answer the question, “Has how I made The Many Faces of Chika impacted how I made my documentary films?” I would say no, because I love fictional films. These are what I watch in my daily life. I just devour them. So rather than saying that making The Many Faces of Chika had an impact on me, I would say that all these fictional films that I watch constantly in my life have been my real influence in my filmmaking.

Now I’m wondering what are some of the most important fiction films that have had an impact or influence on you?

I would like to list out three favorite directors, and you may think there isn’t much relation among them, but they are Stanley Kubrick, Sam Peckinpah, and Kurosawa Akira (laughter).

I’m very interested in what you said about how documentary and fiction films are one and the same and how you are taking influence from fiction films for your documentaries, that’s a very interesting thing to hear. I’m wondering: Did you feel that The Many Faces of Chika was a failure shortly after its release and is that why you haven’t made a fiction film since then?

Well, I actually do not regard The Many Faces of Chika as a failure. I talked about one aspect that I did not succeed in. I brought in the moods and feelings of a documentary film into the fictional space, that’s all. And that is something I regret.

The Many Faces of Chika is actually about my private and public partner Kobayashi. I’ve worked with her for decades and she is my partner in private life as well. So it’s a film with female protagonists, but it’s about the woman I live with and yet I, a man, ended up directing it. So it has that element to it. Because I lived with her for so many years as her partner, I felt that I should just stick faithfully to the scenario she wrote, but I also felt that this would be a film about how men view women. That was my stance. However, she felt strongly that the film was also about how women view men, and that was what she pushed for in the scenario. So I felt, okay, if that’s what the scenario is then we’ll work with it. There was that dilemma. In the end I felt that we should have focused more on how men look at women. After that I felt, “We didn’t get it this time but we’ll get it with the next film.” The reason I haven’t made another fictional film isn’t because I see The Many Faces of Chika as a failure, but because I’ve been too busy making documentaries since. So many things keep coming up in front of me and I haven’t had a chance since.

This came to mind since you mentioned your partner, but I realized that the last time we spoke it was actually your birthday, and I forgot to say happy birthday. I also know that it is your partner's birthday later this month and I’m wondering if you two have anything planned?

(laughs). Thank you very much for your congratulations. Well, to be honest in my mind there’s nothing wonderful about getting one year older so I do not welcome my birthdays, in fact I just feel like I’m that much closer to death, and there are so many other films I want to make before I leave this world. Therefore it’s a torment for me to have a birthday. However when others congratulate me I feel grateful for that. As for my partner, I have no plans to celebrate her birthday either.

This is interesting because I wanted to ask if you were afraid of death. When I watch your films, I feel that a lot of the characters, especially those who are very powerful, have a way of living where they seem to be very fearless. I’m wondering if working on these films has changed the way you look at death at all?

Well, my generation in Japan, who had to survive after the Second World War, did not have the luxury of feeling like “I want to die” or “I’m going to die soon” or anything like that. All we could think about was how to survive. We were so busy trying to survive we never thought about death, really. That’s something I talk about with my partner often, that we’ve never thought about dying or killing ourselves. I lost my son to suicide. Of course that was very shocking to me and I couldn’t understand why he thought of killing himself. I had to think a lot about it. When I think about it, most of the people I choose to film tend to have a philosophy that they would do their very best to survive and live their lives fully.

You don’t have to share this if you don’t feel comfortable, but do you feel like you’ve been able to reckon with or understand the death of your son in the years since it’s happened?

The cause of death is very clear in my mind. Both my partner and I love films. We’ve always made films. We have two children, the boy who passed away and his elder sister. Since these two were born, and even when they were very small, only in elementary school or junior high, we would leave them and go to other parts of Japan to work on our films. We would tell them, “Mom and dad have to go away to do our film work so you guys be good and stay home.” So I did not focus enough on my children. I told you yesterday that I never knew my biological father, and never considered any of the men my mother dated to be a father. To me they were all just “my mother’s men.” I never learned what role a father is supposed to play and thus never played that role with my children. That has stayed with me all this time and that is how I pushed my boy to suicide.

Let me tell you something more specific. In my life, up until I lost my son, I’ve never really had the concrete image of what a father is or is supposed to be, for the reasons I’ve already shared with you. During my youth, what impacted me most strongly was the ethos and philosophy shared by the participants of the Zenkyōtō student youth movement. Their philosophy was: when you are with the socially weak or the minority members of society, you do not calm down or ease whatever you have, you apply yourself fully in dealing with anybody, even with the weakest people in society. You have to share all your strength and all your might and squarely face that person head on. That is what we are supposed to do. That was the philosophy of the student movement era and it impacted me very strongly. I wound up applying that thought to my children. And in reality that was a rather bookish attitude, just a thought really instead of something practical. Of course when I was happy with my children I would show that to them fully and embrace them tightly, but when I was angry I would also show that fully. But in reality children need to be protected by their parents, have to be nurtured in a way, a way in which I was lacking because I had never experienced a true father and did not know how that role was meant to be played. So, one day when my son skipped a Kendo practice that he was supposed to go to I got very angry and hit him. He left our place crying and went to a building, which he jumped off of and died. It seems like he was trying to be rebellious against me, and I recognize now that there was something in me that deserved to be rebelled against.

I just want to say thank you for sharing that and being vulnerable. I’m sorry that happened and I hope you and your partner don’t feel too much guilt.

That’s okay. That sense of guilt will have to be carried by me for the rest of my life. I should bear that. Twice in the past I have thought, “I should make a film about this,” about my son’s suicide, and both times when we were about to start shooting, something happened to stop it. However, I feel someday I must do it, and I will keep thinking about making that film. So far though, different new things keep cropping up in front of my eyes and I haven’t been able to, but I will keep harboring that desire.

What year did your son pass away and what years did you try making the film?

It was in 1989, and I cannot remember when I tried making the films.

This is all actually very relevant to how I felt when watching Minamata Mandala. There’s a sense that even if there’s justice, that their lives will not change. In the third part of the movie I remember someone even saying something similar, that winning doesn’t change anything because it doesn’t improve their illness. Something beautiful about the film is, like you mentioned, that these people are constantly striving for recognition and justice, even if it won’t matter. Something else I’m interested in: In the second part of the film we are introduced to Ikoma Hideo, who has infantile Minamata disease. We have an extended portion of the film where we hear him talking about his love life and honeymoon and how grateful he is to have had that, which reminded me of Sayonara CP and the love scenes there, and of course Extreme Private Eros. Why is it important for you to show this side of the people you film?

This is related to the cause of my son’s suicide. As I told you before, I was born in a shelter during the war, and could have been killed by suffocation, but my mother came to my rescue and I survived. So for someone like myself being alive has value in itself, it is wonderful just to be alive. So let’s talk about Sakamoto Shinobu, another fetal patient of Minamoto disease. Because of the mercury poisoning, she was born like that, and she has become a symbol of the victims of the disease. And though she was born with the stigma of the disease carved into her body, she cannot flatly deny her life just because of her disease. We all have a desire to validate our own lives, right? That is the basis of human existence. We want to feel, “It’s good that I lived this life.” That’s our instinct, right? To validate our lives. Although she cannot fulfill her fantasy and dream, in reality she still fancies all these young men who come from outside the community, all these young journalists and TV reporters, who are young and cool looking. She falls in love with them, and yet she cannot marry them, or have children, or anything like that. But she has the freedom to desire that, at least. And without that she cannot live. And so, because we all need to validate ourselves, and because she has this incredible burden, she has this enormous desire to live her life to the fullest, not in the next life but right now, no matter how cruel it is. She would like to feel that she’s glad she lived this life. And in a way that would be like a paradise or mandala—the affirmation. I wanted to show both sides of this picture.

Interpreter Yamanouchi Etsuko: To me, that was the most heartbreaking depiction of what has been robbed from the victims. You can’t even fall in love, you can’t even dream about having that guy being interested in you. That’s a basic element of human happiness.

Hara Kazuo: Yes, I agree with you.

I loved watching the introductory scene with the Minister of the Environment, where you use a split screen. It made me think of The Emperor’s Naked Army, because when we see the confrontations in that film we see both participants on screen. Here you see them both head on. It felt like a culmination of your entire career, of trying to depict this power struggle. This situation where we see it so plainly, and can see so clearly the differences in their facial expressions was remarkable. To turn that into a question: How have you found it most effective in depicting these power differences in your films?

Drama, or conflict—in any drama there is conflict right? Humans are creatures who live in relationships of all sorts with others, we receive stimuli from others and give it back in return. We exchange stimulation, right? And in that exchange comes the energy for living, right? In creating fictional or documentary films they have this classical method of cutbacks, showing the conflict that A and B have with each other. In Minamata Mandala, we had two cameras so we could do what we did—showing two opposing sides on the same screen. My method is: When filming conflicts you have to show both sides, A and B, at the same time.

How much footage overall did you shoot for Minamata Mandala? I know it’s a long film, but I’m wondering how much more footage you shot?

I’m not sure if this is accurate but people told me one thousand hours (laughter).

Oh my goodness. How did you decide the length the film has now? What was the process of culling that footage down to six hours? Did you want it to be longer?

Out of the total footage I first made an eight or nine-hour long cut that just flowed as one film. Then we would watch it from the top to the end, pick out some parts that could be omitted, judge if some scenes were essential or not, and cut from there. We made a seven-hour cut, and then brought it down to six hours. When we got to six hours I felt we no longer needed to cut any more.

Do you consider this to be your best film?

Well, although I’ve been called a director for some time, directors always have room for growth. As you make films you grow as a director, but also as a person. I feel like I have grown enough now, as a person, to make Minamata Mandala.

In what ways do you feel like you’ve grown as a person?

(laughs). That’s difficult. Until now, I’ve always felt I really, really had to offer a clear-cut explanation for a film so that the audience could have no mistake in understanding the issue. I felt I had to give them impactful scenes and a detailed explanation until it became too much. Now I feel like as long as you offer some basic important information, the rest you can edit quite a bit. As long as you have some essential information in it you can just trust the audience, and leave it out for them to realize for themselves. Now that I trust the audience a little more, I feel liberated in my filmmaking.

Just a few more short questions and we’ll be done. I’m curious: When was the last time you saw Miyuki from Extreme Private Eros?

More than ten years ago was the last time I saw her. However Miyuki and my partner, Kobayashi, are in touch with each other on the telephone.

Wow, really?

Yes. So I hear about her indirectly sometimes.

Wow, I am very happy to hear about that. Another question I had, and maybe this is just someone with the same name, but you’re in the credits for Shin Godzilla by Hideaki Anno. Are you in that film?

Yes, I’m in it.

How did that happen?

I’ve struggled behind the camera all my life. At one point I felt, “It must be easier in front of the camera,” so I wanted to act. Director Anno came to some of my workshops and contacted me with some questions he had about film. I responded and we got to know each other. So I told him, “I want to act. Give me a good role!” and he remembered and brought me on.

That’s great. Did you like acting?

Yes, although I actually screwed up on set. I only had one short line, but they had to do 36 takes to get it right. I thought it was only about a dozen at the time, but it was actually 36 takes they had to do because I couldn’t deliver my line (laughter).

Thank you for sharing that. Is there anything that you wanted to say in an interview that you’ve never had the chance to say?

I have a mountain of things to say, but that would take another two hours, so I’ll leave it to your best judgment.

I have one final question for you, and it’s a question I ask every person I interview at the end of all my interviews. The question is: Can you share one thing you love about yourself?

In my filmmaking career I’ve never thought of a film as merchandise at all. Rather, I belong to a generation that is constantly questioning how we should live, how best we should live in the present era—or it could not be a generational thing necessarily, and maybe I’m just that type of person. I’ve always searched for how to best live through my filmmaking, and I think I’ve really pursued that and stuck to it. I am happy that I have this method of expression—documentary films—and I feel that if that was my destiny then I have lived honestly by following my destiny. And I feel mostly like you must be tired now (laughter).

Thank you so much for your time.

Of course, thank you very much.

Five of Hara Kazuo’s films—Goodbye CP (1972), Extreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974 (1974), The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On (1987), A Dedicated Life (1994), and Sennan Asbestos Disaster (2016)—can be watched on the Criterion Channel.

Thank you for reading the 18th issue of Film Show. Let’s all try to live honestly by following our destiny.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.