Film Show 017: Our Favorite Films, January-June, 2022

Our favorite films, new and old, that we watched in the year's first half

Hello friends, welcome to the seventeenth issue of Film Show, the corner of Tone Glow dedicated to Cinema. This one has been a long time delayed, but we appreciate you patiently waiting for more Film Show. We have a lot planned for the upcoming months so please stay tuned for updates. Thanks for reading. —Samuel McLemore

The Fiddlers of James Bay (Bob Rodgers, 1980)

If you’re prone to becoming existentially stressed by how easily entire cultural practices and traditions can disappear in a puff of smoke I don’t recommend getting too deep into regional folk music. I don’t mean the stuff that’s technically dead but generously well documented—like your Delta blues and what have you—but the musical traditions that are held together by a thin roll of twine. I mean the sort of music only being practiced by four aging families in a ten mile radius; the stuff you need to experience through YouTube videos recorded in church auditoriums, because there aren’t albums you can queue up on Spotify. If there are so many types of music in such a critically endangered state, just think of all the others that faded into extinction with not so much as a whisper in memoriam. Horrifying, isn’t it?

Fortunately for me, I derive a bit of strange enjoyment out of that existential horror. I see it as an opportunity to celebrate the people that continue to celebrate themselves. I’m under no illusion that there’s much I can do to stem the raging river of time, but I’m happy to simply pay my respects. Such is the case with the James Bay style of fiddle playing in Northern Québec, which was in a state of emergency even when The Fiddlers of James Bay documentary was made in 1980. The fiddle arrived in James Bay some three centuries ago by way of Scottish traders, and took up root with the Cree indigenous people. With more than 300 years to master the instrument, the fiddlers of James Bay play a style that is both shockingly familiar and radically different to what you can still hear in Scotland.

The filmmakers underscore the similarities by playing recordings from Cree fiddlers to Scottish players, who express shock that they aren’t listening to local musicians. However, the differences become apparent when two James Bay virtuosos are brought to the Orkney Islands—the birthplace of the indigenous style—to play with a Scottish orchestra. The Cree fiddlers are initially incapable of playing along with the Scots, because they tend to play alone and improvise extensively. And while some songs in the Cree rotation are familiar tunes that remain unchanged, they play songs that have been long lost to those distant shores, bringing back songs that haven’t been heard on Orkney soil for a hundred years or more. The fiddlers learn to follow one another as the rehearsals continue, and fundamental lessons are learned on both sides. The Cree musicians learned context for songs that were long only identifiable to them by apocryphal titles, and the Scots realized that their music was probably not always so rigid and beholden to structure.

Today, the James Bay style of fiddling still seems to be hanging on. There are academic studies to read if you’re so inclined, and there’s even, amazingly, a modestly populated Rate Your Music page. Younger Cree musicians like Harry House still carry on the torch, but how much longer can it be expected to last? While the flame still burns, I’m thankful for the opportunity to huddle close and share the warmth while I can. —Shy Thompson

Im Wiener Prater (Friedl Kubelka vom Gröller, 2013)

In a recent interview, the photographer and filmmaker Friedl Kubleka vom Gröller noted that “even if people like the films or they don’t like them, for me making them is the most important part. In many of my works, I seek a reflection of myself.” It’s an admirable (and relatable) position, especially when I think of how vom Gröller’s films are largely portraits of others—family, friends, strangers. She’s stated in the past that a good photographer can reveal more about themselves than who they’re shooting, which is aligned with how she taught photography to her students: “take photography as a pretext to fulfill your unconscious, forbidden wishes.” (Naturally, she once trained as a psychoanalyst.)

Such an approach to art feels like the sort of thing that results in vacuous, surface-level edginess. I consider a lot of Viennese Actionism to fall into this camp, and what appeals to me about films in this lineage has less to do with the actual shock of what’s being seen than how they appear in a filmic medium—the rapid edits of Kurt Kren’s shorts render everything a kaleidoscopic spectacle, while Ed and Irm Sommer’s Maria-Conception-Action: Hermann Nitsch (1969) is mostly evocative for how its blood beautifully glimmers.

Although vom Gröller is Austrian and has a couple films that fall into this lineage, her works have a largely different bent. The overwhelming majority of them are silent, black-and-white, shot on 16mm with a camera mounted on a tripod, and under three minutes. The inherent durational aspect leads to a notably different experience than what one has with her photography: there’s a more pronounced interfacing of person vs. camera, of performance vs. truthful presentation. In a way, watching her films feels like watching these people in real time, or even having the camera faced on us. There’s a disarming simplicity to it all, which is sometimes ruptured in equally simple ways—Lisa (2001), for example, ends with a kiss that feels quiet but momentous. Every gesture or non-gesture feels suffused with rich emotion.

It’s difficult to single out a single work in vom Gröller’s filmography as it’s truly greater than the sum of its parts, but Im Wiener Prater is a legitimate marvel. For one, it’s a far more meaningful work of (ostensible) Actionism than the biggest male artists in the field (and is also far removed from the work of VALIE EXPORT). It begins with a pan of a snow-laden forest as a woman walks around. The camera is shaky and often beside/behind a tree to convey a sense of voyeurism. Soon, we see the woman with her ass bare as she squats to take a piss. At one point, it flows directly onto the camera itself, the barrage of fluid creating lovely, abstract images. It’s surprisingly tender, like we’re being led into this personal, private moment. A lot of Actionism, in its public performance, is the opposite, and never upholds or invites sensitivity. When Actionism co-founder Adolf Frohner stated, “I accept reality, which is still beautiful and true even when it is ugly,” it was really him saying that he didn’t care about beauty without extremity. Hermann Nitsch, even, was mostly drawn to the intensity of tragic plays and the like. The subversion and triumph of vom Gröller’s Im Wiener Prater is that it mines beauty from an “ugly” act that’s small, solitary, and banal. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Mad God (Phil Tippett, 2021)

After thirty years of work, Phil Tippett (the VFX legend responsible for some of the most iconic practical effects in movies such as the original Star Wars trilogy, Jurassic Park, Robocop, and Starship Troopers) has redefined the medium of stop-motion animation. His masterpiece Mad God may be the most technically jaw-dropping work of stop-motion animation ever put to film—and the most disturbing. Over the course of half an hour of painstakingly rendered and unbelievably complex animation, Tippett drags the viewer through a dialogue-free and sparsely plotted descent into a Hellish underworld. Like a travelogue from your worst nightmares, each new scene presents a new and terrifying vision of the grimy hellscape—from an endless and dehumanizing factory-city to a WWI battlefield so cratered that it resembles the surface of the Moon, to a sinister alchemist’s lair, every macabre environment is lovingly rendered and populated with bizarre creatures of all sorts. With no distracting dialogue and a haunting, sparse soundtrack punctuating the film’s most shocking imagery, the viewer is free to let their eye wander over a truly unbelievable feat of technical mastery.

Its storyline is simple enough to feel allegorical, yet complex enough to sustain hours of analysis. The film asks difficult questions about the role of humanity in relation to the epic scale of time and space, the nature of war, industrialization, and labor, and the meaning of creation and religious belief. It’s a lot to convey without a single word of dialogue, but Tippett trusts the audience to follow him on this journey. Especially in the context of the film’s real-world backstory as an extended labor of love, one of the strongest thematic throughlines is the portrayal of the creative process as a grueling struggle towards an end goal just as profane and debased as it is virtuous. The viewer is forced to ask whether, in his depiction of creation as a selfish and often violent process, Tippett is implicating himself and his thirty years of work on Mad God; while the real-world subtext never takes over the film, it does provide a fascinating lens of analysis. Those willing to make the descent into Mad God’s never-ending hellscape will find themselves rewarded with a technically incredible and thematically rich masterpiece. —Chloe Liebenthal

Memoria (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, 2021)

I'm only here to talk about one thing—that sound. It will demolish you on theater-grade speakers. It incontrovertibly is; despite its interruption of and intrusions upon the main character's life and world, it asserts its materiality with such violence that, in due course, it renders all else a dream. The question it asks starts as "what is it?" and ends as "what else is there?" Like any good mystery, Memoria inverts the alien and the familiar with every step it takes. It's certainly not a mystery movie, but it takes the attention to detail and earnest scrutiny that one often approaches a mystery with and reorients them towards possibilities rather than answers. While I've yet to sort out how much this film resonates with me on a personal level, I can't deny that it feels remarkably in tune with the art I've come to cherish lately: art that attends to the act of listening, visualization, perception, etc. and its plasticity, its sensory core—not what something means, but what it does, what it makes me do. I should probably just meditate, but it's nice to be reminded, every so often, that I'm my body as well as my mind. —Jinhyung Kim

Friends and Strangers (James Vaughan, 2022)

“The work of hands is trustworthy. Words…” “Words are not.” Sometimes when I work in words, I become suspicious of myself. There has to be a lie somewhere in there. A springcoiled expression, a self-destructing core, the cursed remainder of whatever procrustean measures criticism so casually undertakes. Twin tyrants, domineering self-doubt and passionless self-sabotage—everyone is just too polite to pull the thread. It seems that reality, authenticity, haecceity gainstrive beneath a ceaseless barrage of words and representations, mutant shadow things. For now, it holds. The real is a redoubt. A home made of words is a thing hollow and hollowing forever. But this sentiment, this faith in the hardness of things, is ultimately words too.

Friends and Strangers is not shy. From its first moments, it wants to tell you what it is really about. It hands you the hermeneutic. Beneath the opening credits, we see the visual world of the 18th century colonizer to Australia: views of Port Jackson, illustrations of local flora and fauna, the Governor’s house with Union Jack a-flapping, and lastly The Taking of Colbee and Benalon. This, of course, adds a certain charge to the proceedings. Historical weight inflects even the most mundane shot-shit. When a stranger says something to you, it means something. And the meanings multiply and stratify and interpenetrate. A weak Manicheanism emerges.

Miles informs us that this is a horror movie, and we should believe him. When he tells Ray, the hangdog doryphore we follow for most of the film, “Your memory's like a big mansion with all these different doors, and when you lock off whole sections, that's when things start to get real freaky,” we know he is not just talking about Ray’s catastrophic break-up (Sophie, who else?). As we arrive at the real mansion, David asks Ray, “Where’s it going for you, though?” and suddenly we have Ray’s ersatz videography career—a fiction so thin and faltering that he occasionally forgets to perform it—standing in for the future of mainstream Australian politics. Is that taking it too far? It seems there is thread, locked in tension, running from this moment deep into history, fine vibration and subtle shudders marking evidence of some contact down there. We were warned: “If you don’t deal with fucked up things properly, that when things become haunted.”

A world is dying here. It is a world of critter business and bean cognition and the many, multiform attempts to transcend them both. David’s mansion is sham construction. The glittering palace is a middenmound. Nothing but friable plaster yet still dozens of paintings hang securely. This whole place should be condemned, torn down, if anything lasting is to occupy the space. Caprice and contradiction rule, but as long as they never slow the house of cards may stand through another squall. Some Scelsi intrudes from a neighbor’s hi-fi and reconfigures the place as a giallo abattoir. The thread might snap at any moment.

Ray is one of the inheritors of this world and its senescent, suicidal putterings, steering the sum of us towards further catastrophe. The film cannot bring itself to blame for any of this. How could it? He is hapless and adrift, caught as much in the swirl of things as everyone else. His great sin, notwithstanding his petulance and pedantry, is velleity. When he and Alice go camping at the start of the film, they meet a caravaner touring the country with his young daughter. He is an emblem of an older world, a world that died so the one we now float about in could live:

I think Sydney was a much more interesting place then. […] Just more, sort of intellectually curious. There was a lot of discussion around the evolution of the culture in Australia at the time and people were willing to discuss things and talk. The doors were always open. You could walk in and meet people, complete strangers, and have conversations. About art, music, philosophy.

The world we got in exchange seems certainly lesser. Stirrings, where they occur, are distal, elsewhere. At the core, what we get, is a superior mirage, castoff heat-haze from the fracedinous corpse of the dead father. Is this unfair? The departed Australia of the caravaner’s youth benefits of colonization as much as the rest of it.

There are, of course, older and still living elders, but they will make no appearance in Friends and Strangers. There is a glimpse—a bronze plaque situated well below the fountainlike monument of Arthur Phillip. Other than that, and two brief mentions, there is not a trace of Indigenous Australia. In one of those mentions our campers learn of a nearby trail: “There's plenty of Aborigine doodles up there, you know, that you can have a squiz at. But it's getting late in the afternoon now.” Even through his tedious, circular chat, there’s an edge of portent.

In contrast to his erstwhile camping buddy Alice, a regulator overseeing tax law infringement done by corporations, Ray does nothing to either resist or enforce the mechanisms at work, the regulated flow of power across peoples and places. He is aloft, mote-like, on the billows of the world, the grand circulation of words and things. Though he lacks the sleepwalker’s conviction, he advances by her method—consciousness something of a burden in the wake of words. He is almost entirely without desire. At the end of the film he tries to resist what seems to be a life foresentenced to failure, a totally unpitiable mediocrity. Needless to say, that too fails.

“Would you agree with the statement that videography is the art of illusion?” Normally, it is not too much fun, thinking about a film that begs you to allegorize. After all, what is there to think about? There is an answer key, likely within reach. Friends and Strangers anticipates this and responds with wooliness, dead-ends, gags, and accidental philosophic discourse. From the excruciation of the in-tent conversation of Ray and Alice to the hostile architecture of David’s mansion, the sensibility is that of an EXEK record by way of Kalman & Horn. “Is that a trick question?” “Is that a trick answer?”

It’s too inviting and too funny for anything so straightforwardly self-serious, but it’s there. Is videography the art of illusion? Can the illusion communicate in excess—above, below, around, beside—of its text? The world imaged in Friends and Strangers is perhaps not as cut and dry as I have made it seem, the symbols and indices not so eagerly announcing themselves. If things seem warped, uneven, or omitted in my accounting, maybe they are. But this is the suspicion of words. Take a look for yourself. The whole armature is spun of threads. Dauntless and erect, the tallest poppies daring to be culled, these threads want to be pulled, for in the unraveling it is revealed that the image is the tapestry, the stem the soil, and the nation its unreckoned violence. —Matt LaBarbera

Double Team (Tsui Hark, 1997)

This is one of the most optimistic films I’ve ever seen—every moment is full of potential and possibility, tension and motion, clarity and disintegration; nothing remains static. What’s incredible is that this is actually the opposite of totally unstructured, illogical, free-associative “play”; the world of Double Team is most certainly “our” world, one (mostly!) bounded by certain laws like, say, gravity. In a sense, Double Team is a gigantic, kinetic physics experiment that reveals the underlying structure of the world by pitting its various constituent parts against each other—foot against pavement, bullet against glass, lung against water, scalpel against flesh, a collision of many distinct materials in time and space—in the process highlighting the sprawling proliferation of technologies produced by the increasingly complex social and technical division of labor under capitalism, one that, in Tsui’s specific vision, takes the form of an endless cavalcade of gadgets, buttons, trinkets, screens, scopes, sonograms and digital spyglasses that mediate the human experience. This extends to the form of the film itself, which is driven by rapid cutting, zooming, panning, slow-mo time-stretching, splicing between figure-eight binocular vision to the cold blip of satellite imagery.

Much of the film is driven by a quest for ubiquitous “access codes”—“where are the access codes?!”—indicating a Deus Ex level of sheer, abstract paranoia regarding “the powers that be” without ever really caring to sit down and explain who they are, what they want, or why it could possibly take at least a dozen fight scenes involving tigers, toe-knives, and carnivals gone horribly wrong to get closer to the truth, whatever it may be. While that may lead to the tempting conclusion that this is a film without meaning, or one that highlights the “meaninglessness” of “contemporary life,” I want to strongly caution against that; I think there is an objective truth to be found at the end of Tsui’s warped tunnel. The fact that the film co-stars Dennis Rodman and revolves around the US spying on North Korea, and that in 2017 Rodman became a de facto US ambassador to North Korea under the auspices of “a ‘mission’ funded by PotCoin.com, a company that peddles cryptocurrency for buying and selling marijuana,” is Double Team’s final victory—a confirmation of the truth contained within. —Sunik Kim

The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974)

Starring Gene Hackman as a paranoid, awkward audio surveillance expert who’s been hired to listen in on a conversation between a young couple strolling through the park, the film makes a powerful impression through masterful sound editing and a terrific performance by Hackman.

Of course, in a film about the way sounds can betray and ensnare us, the incredibly complex audio is the true star. The titular conversation is replayed over and over again, and the scenes where Hackman’s protagonist manipulates a meaningless hum of background noise to reveal the mysterious dialogue lurking underneath uses the repetition of the slowly-evolving audio to masterful effect. Just as interesting as the conversation itself is the use of sound throughout the film as a whole- constantly punctuated by background noise and the clatter of emotional outbursts, and cleverly disrupted by audio distortions that conflate the viewer’s perspective with that of the characters listening to imperfect recordings. In the midst of the chaos, the protagonist’s only solace is his hobby of playing saxophone along with his jazz collection, attempting to recapture some delight in a world where all sounds have been tainted by corruption. Coppola, in showing a man forced to confront how his use of modern technology to steal others’ privacy has eroded the very foundations of his morality, both sympathizes with and indicts the technology our modern world has forced us to live with. —Chloe Liebenthal

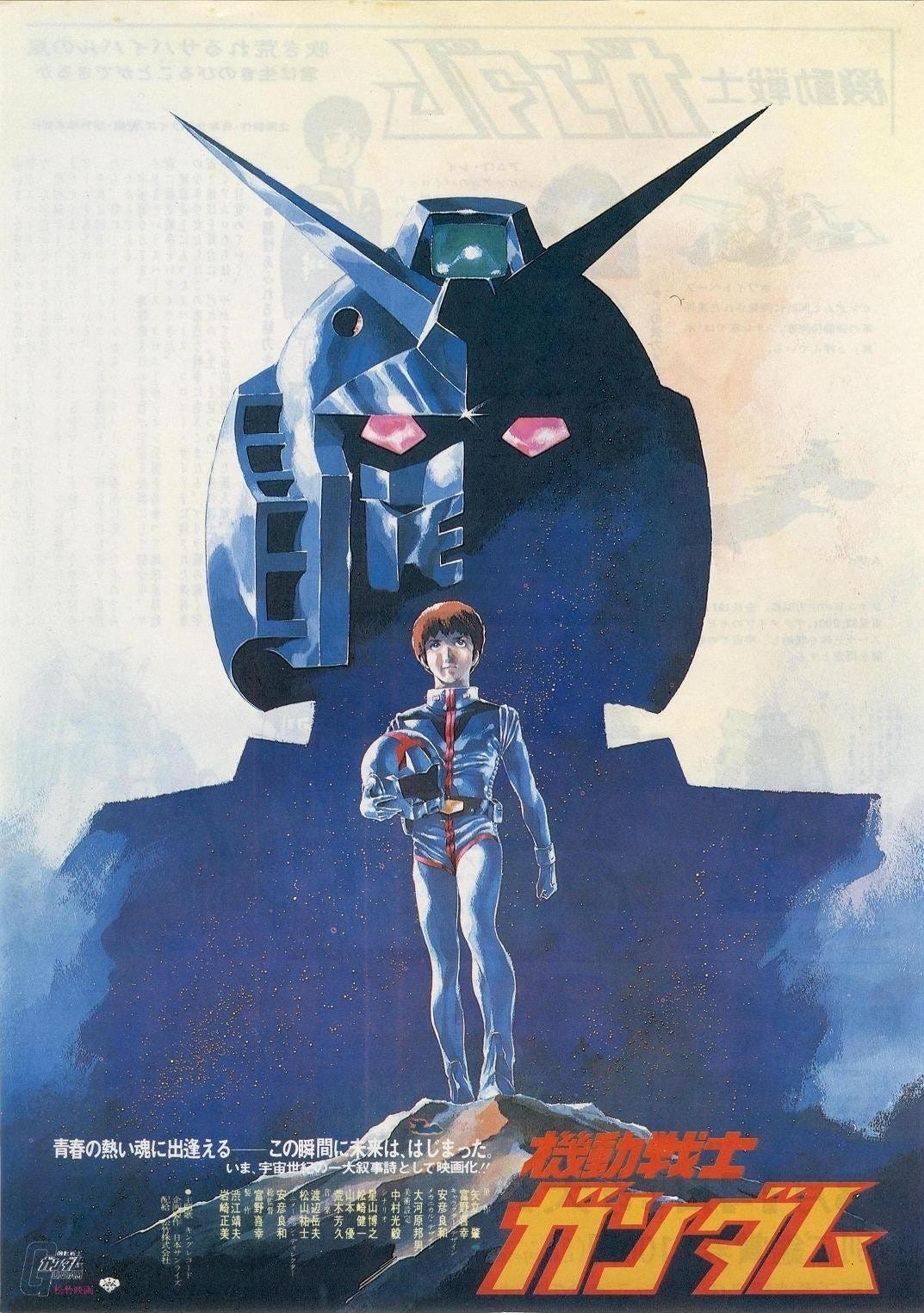

Mobile Suit Gundam trilogy (Yoshiyuki Tomino, 1981-1982)

This trilogy was very much a pending assignment for me. I used to play with the toys of the franchise as a child, but somehow only got around to watching the original trilogy of films this past month, at age 51. I've been a casual fan of anime since childhood and it has been interesting, from a purely aesthetic point of view, to witness the changes in the art through the years. In that sense, the remastering of the HD re-releases almost offers the ability to see how the trick is done, so to speak, as the fidelity of the image has become so clear that we can now spot imperfections in the acetate, or the characteristic look of airbrush painting on illustration board and so on. Also, throughout the trilogy we can see marked improvements in the animation of the characters and the coloring process, almost like a school trip to the animation studios where the magic was created. In any case, what makes this trilogy so satisfying to watch is the story line.

They may be tropes we are all familiar with: technological progress marred by an inability to solve our problems in ways other than war; the ongoing struggle between an imperfect democracy and an idealistic totalitarian–but throughout the trilogy we get a strong sense of resignation, with the narrator acting as a Greek chorus in a classic tragedy, with a strong emphasis on what make humans inherently unique and valuable. We feel each character as fully believably human and feel their loss as they perish in action, watching with stoic admiration.

In the middle of this bloody war between human colonies in space we witness the emergence of a new type of human that are both more human than the old type and more aware of the instinctual connection between all life. Offering the key to eradicate war as a means to settle differences; these "Newtypes" are both far better at combat than regular humans and much more empathic, willing to understand each other and more sensitive to the loss of human life.

After all this time of being familiar with the Gundam as a paradigm of the combat robot that played such a large role in my childhood fantasies, watching the trilogy as a somewhat reluctant adult male has me realize that the mobile suits have never been what matters in the series; what has made Gundam endure has been the stories of the people who are manning them and the promise the Newtypes hold: that evolution will finally offer us a glimmer of hope in the face in eliminating war before the increased killing capabilities offered by technology eradicate us all. —Gil Sansón

Cinécité (Djouhra Abouda & Alain Bonnamy, 1974)

There's an incredible collage of music in Djouhra Abouda & Alain Bonnamy’s Cinécité, and it works far better than in their 1972 film Algérie couleurs because the images match its sporadic construction. It begins with Albert Ayler's “Spirits Rejoice” as time-lapsed shots of the Arc de Triomphe appear both plainly and in varying hand-painted colors. Given that the song riffs on the French national anthem (“La Marseillaise”), it provides a lovely taste for the reimaginings that define the remainder of the film.

There are shots of Marilyn Monroe as “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” and “Incurably Romantic” play, cut alongside bits of Farid al-Atrash's “Ya Habibi Tal Gheyabak” (“My love, you have been away too long”)—a track which features dozens of variations on how that titular line is rhythmically and emotionally sung. It’s a song all about prismatic capacities, which translates to the movie itself. When we witness flickering shots of French streets, or watch as the camera faces skywards and the buildings and clouds grant a sense of grandiosity, there's a love for the infinitude of this locale.

We also see: Fred Astaire in A Damsel in Distress performing “I Can’t Be Bothered Now,” nude female body parts, and more evocative images that look like France as viewed through a tin kaleidoscope. The soundtrack includes Billie Holiday’s “Lover Man (Oh, Where Can You Be?),” Albert Ayler's “Bells,” Archie Shepp’s “The Magic of Ju-Ju,” and most notably, Luciano Berio’s musique concrète masterpiece “Visage.” This mesh of pop with the avant-garde, of clarity with abstraction, makes for a spectacle that points to a love for the interconnectedness of all things, of how every city is an amalgamation of the peoples and their cultures, and how electrifying that reality really is. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Careless Crime (Shahram Mokri, 2020)

Shahram Mokri is a director with a singular vision. Complex long takes, magical-realist storylines where time folds in on itself, and cutting portrayals of modern-day Iranian society and culture: his filmmaking style was already solidified in earlier works Fish + Cat and Invasion, and with Careless Crime, Mokri stretches this distinctive style to new limits. It’s an experimental epic that cuts across time and through layers of reality (I think) to tell the convoluted tale of the many lives affected by a group of men who seek to commit arson and replicate the infamous attack at the Cinema Rex, which helped trigger the 1979 Iranian Revolution. Densely-plotted, Careless Crime, switches modes easily from a quirky comedy charting the relationships of people drawn together by a love of the cinema, to the psychological horror faced by a group of people who find themselves literally trapped by the aftershocks of their cultural past, to a surreal fable analyzing how Iranian history resonates today. —Chloe Liebenthal

Possessor (Brandon Cronenberg, 2020)

It's a bit of a curse being the progeny of a famed artist and work in the same field, isn't? You kind of get halfway there right away by virtue of the merits of your parent and at the same time are bound to be judged in their shadow. Brandon Cronenberg seemingly wants to acknowledge this from the start so the viewer can get on with it and simply judge the film on its merits. The Cronenberg surname carries a whole lot of expectations of misanthropy and body horror and Brandon chooses to claim this inheritance by attempting to up the ante a bit, maybe because of the most recent work by his father, which deals with more realistic types of violence (David appears to have taken the gauntlet, in fact, with his most recent film, so maybe he was impressed with his son enough to "show him how it's done"). Possessor gloats in brutality and body harm and combines cinema verité type of filming with contrasting scenes that are much more artfully rendered, in an interesting way: the more considered and artistic shots are given to the processes, both physical and mental, of body hacking at the core of the film, while the more haphazard ones are reserved for the actual violence.

As a sci-fi/horror film it works beautifully, delving in the alienation and potential disruption of identity as the main character jumps in and out of the bodies and minds she hacks in order to do her work as a paid assassin, with each new job taking a sizable toll on her psyche and perception of herself as a body and as a mind with clear boundaries. It's rather impossible to feel empathy for any of the subjects as the camera doesn't seem to relate to any of them, and the interest lies in the now increasingly real nature of mind and body hacking that actual enterprises like Neuralink are making real and the many ways in which this technology will be weaponized and turned against others, either with consent by the manufacturers or by way of mercenary hackers. It's a subject matter that deserves to be treated in the very pessimistic and cold way the film approaches it. —Gil Sansón

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, 2001)

It’s only recently that I’ve started watching movies in earnest in my free time; I think I’ve finally found the patience that tended to elude me before. A.I. Artificial Intelligence is a film that’s lingered at the border of my mind for years—blame it on a snippet I caught on YouTube where Haley Joel Osment’s face droops like a stroke victim’s after he’s goaded into eating spinach—but my first watch of it in full happened this February. A.I. is many things: a fractured retelling of Pinocchio, a candy-coated nightmare, a famously drawn-out and bizarre collaboration between the near-diametrically opposed sensibilities of Steven Spielberg and Stanley Kubrick; it is extraordinarily good at raising questions it is either unprepared or unmoved to address. The robot David (played by Osment) is chief among these questions, captured in a performance at turns terrifying and sympathetic: there is a wondrous fear underpinning the brash, childish authenticity of his actions. He is an undying toy created to project a specific and possessive vision of love at creatures whom he will inevitably outlive. This horror is compounded by one even crueler: the object of his affection, his “mother” Monica, quickly grows tired of his eccentricities and discards him.

A loosely sketched ontological conflict between “orga” (people) and “mecha” (robots) rears its head on several occasions, manifesting in modes of uncanny-valley revulsion: at the drolly camp “Flesh Fair” that opens the movie’s disjointed second act, cartoonish rednecks jeer at broken and degrading machines, decrying them as an act against God; prostitute-bot Gigolo Joe (played by Jude Law) reassures a whimpering human client that he’ll satisfy her so thoroughly she’ll never want to return to organic sex. Joe, the film’s most magnetic character (literally), spells it out in blunt Jurassic Park fashion: humans made robots “too smart, too quick, and too many.” The streets, swamps and junkyards of A.I.’s dystopic future are littered with half- and quarter-consciousnesses: beings granted an inner life dedicated to base and menial tasks. Even David, perhaps the most complete and Turing-proof of all the mecha we see on screen, is shunted into a role that demands he pursue, unendingly, a goal he quickly loses all means of reaching. Casual sadism—something that director Spielberg’s warm, humanistic framing does its best to obscure—is the animating force of A.I. The late William Hurt plays David’s creator, Professor Hobby; he smiles in delight when David’s hopeless quest to win back his mother’s affection leads him to Hobby’s office in a flooded New York City. Grabbing David’s shoulders, he beams: “Do you have any idea what a success story you’ve become?” —Maxie Younger

Cathedral (Ronald Chase, 1971)

If Luther Price’s avant-porno masterpiece Sodom merged the sexual and spiritual in a pointed display of riotous “depravity,” then Ronald Chase’s Cathedral is its antithesis: a tender portrait of gay intimacy that aims for religious transcendence. Chase’s decision to not show any explicit penetration could’ve rendered this unnecessarily conservative or as banal softcore, but his pacing of images is crucial. The curvature of pelvic bones, the softness of light on skin, the nestling of bodies—they all appear in close-up, with dissolves allowing the film to feel otherworldly in its intimacy. Slowly, these abstracted views of body parts broaden in scope, with entire bodies cuddling. The goal is pure feeling, and it’s largely accomplished from reducing every torso and limb and face to something elemental: texture, color, a site for hands to caress. This is aided by the soundtrack—soft, minimal synth droning—whose sustained notes capture sex as an experience outside of time. And to close it all out, Chase superimposes shots of stained glass over these men as the music revs up: a build-up to an ecstatic climax. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

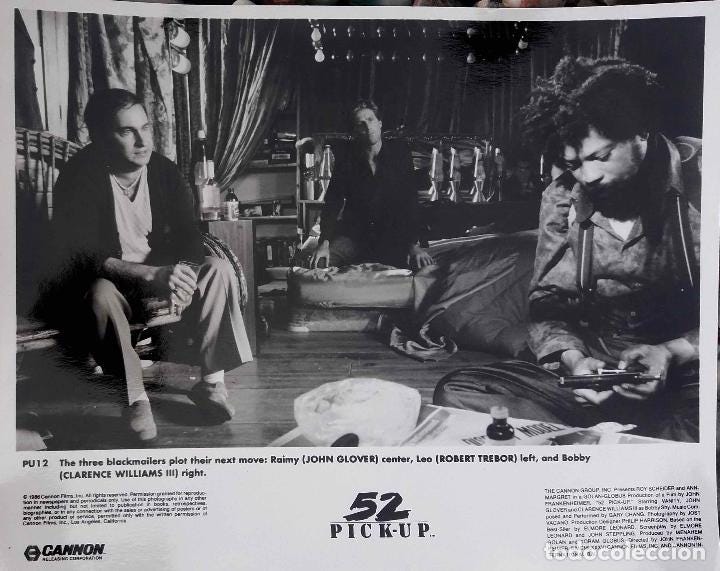

52 Pick-Up (John Frankenheimer, 1986)

One of my greatest pleasures over the past few years has been relaxing on the couch with my partner Reagan, watching movies on the free streaming site Tubi. Perusing its selection of low-budget action flicks, trashy horrors, erotic thrillers, and other direct-to-VHS detritus feels remarkably similar to memories of wandering around video stores when I was a kid, staring at row upon row of tantalizing covers and imagining the thrills contained within. I wasn’t allowed to rent most of the movies I wanted to see back then, but now we can watch all of them in a neverending marathon that could easily last the rest of our lives.

Most of the crap you find on Tubi deserves to be relegated to discount DVD bins and free streaming sites, but there are diamonds in the rough like 52 Pick-Up. Directed by thriller giant John Frankenheimer and based on a novel by Elmore Leonard, it starts out like a classic neo-noir potboiler before spilling over into something else entirely. The basic plot involves a blackmail against construction magnate Harry Mitchell (Roy Scheider) and his wife Barbara (the amazing Ann-Margret), who is running for city council. A trio of goons present Harry with a videotape of him and his mistress. He can’t go to the police, so he takes matters into his own hands, and things go sideways from there.

As Harry descends into the sleazy backrooms run by his blackmailers – a trio of amateur pornographers played by John Glover, Clarence Williams III, and the fantastic character actor Robert Trebor – 52 Pick Up feels like it’s part of a spiritual trilogy with Hardcore and 8MM, plus an extra serving of gritty pulp and some genuinely shocking violence. The tension comes from a constant seesawing of which desperate maniac has the upper hand, and the final scene inside Harry’s sports car made my jaw drop to the floor. Barbara, Leo, and Grady are all too pure for this world. —Jesse Locke

jeen-yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy (Coodie & Chike, 2022)

What does it mean to actualize yourself?

Is it making your dreams a reality? Is it providing comfort for yourself and those closest to you? Can you ever really define it? What about when so much of your life is dissected, in and out, perpendicular to your artistry and career, that no secrets are left? There’s no real answer, huh? At the heart of jeen-yuhs is a reflection of Kanye; not as he actually was, but as he feared he was. The same fear eternally felt by all those who see themselves as talented: unrecognition.

Coodie himself modeled the film after Hoop Dreams, but unlike that film, which followed the lives of total unknowns William Gates and Arthur Agee, Kanye’s story is almost universally known now. To watch the footage is to know that Kanye will ascend to fame and glory, but there’s always a smidge of fear in his eyes, some self-doubt creeping in. He is still mortal. And so much of jeen-yuhs’ appeal is capturing the history in real-time, in reliving the famous moments just like the Beatles Anthology or The Last Dance. But there exists more of an honesty in this film, the home camera’s amateurism speaking to the level of faith in what Kanye would become. Coodie is a subject as much as Kanye is, both of them united in their unwavering faith that Kanye would make it. For Coodie this was a Nostradamus gambit that ex post facto justified his prior dedication. He positions himself as the viewer’s conduit, an extension of ourselves who are infatuated with Kanye West, just a bystander chronicling the myth that would become legend.

It’s easy to make fun of this type of standom and I do it all the time, but transcendence deserves some sort of reverie, you know? Of course an unhinged nigga from the Chi would make a great documentary!!! What did you expect!!! —Eli Schoop

Answering The Sun (Rainer Kohlberger, 2021) / Declarative Mode (Paul Sharits, 1976)

In a way, I feel my path toward this film was prepared by the recent screening of Rainer Kohlberger’s Answering The Sun at the Prismatic Ground closing night. Kohlberger, like Sharits, is someone who works intimately with process, at the extreme fringes of visible legibility. His films sometimes resemble nothing more than explosions of particles, from which discernible figures or objects only sporadically emerge. Yet this adherence to processual constraints gives his earlier films a certain degree of predictability on the ‘narrative’ level: each film will explore its matter—the internal configurations of its aesthetic territory—in a thorough and engaging way, and then end. This is very typical for experimental cinema in the 10-30 minute range, in a sense perfected by the structuralists, including Sharits. Answering The Sun is not predictable on the narrative level. Several times, it veers radically, at one point becoming, say, an imageless sound-piece, or a contemplative series of swelling and contracting circles. The permutations of the film are not derivable from the outset, and this gives the film its element of genuine drama.

I thought about this frequently while reading Sharits’ handwritten drafts in preparation to show Declarative Mode. In contrast to his earlier, structuralist works, which often proceeded algorithmically, almost circularly, through their content, here Sharits emphasizes over and over the unpredictability of Declarative Mode. Yes, it consists of nothing but frames of pure color, sometimes in rapid succession, intercut with substantial periods of darkness. It is not formally dissimilar to the ‘flicker films’ which had, by 1976, already become a fully-fledged genre—and though there are some bursts of intense, flickering light, the overall focus is not on pure structure or optical effects. There are echoes and repetitions, but not enough for us to anticipate what, in any given moment, will happen next. Sharits himself, in the same notes, compares the film variously to a novel, a soap opera, and even the popular television show Miami Vice.

Both of these films have become important to me in thinking about what can be done with pure color on film. Even at this level of abstraction, we find the necessary grammatical units for the construction of a narrative, for an experience which leads us through several events, or moods, or states of mind. I am no longer afraid of the ‘messiness’ of such filmmaking; I no longer prefer to see films which are hermetically self-contained or self-generating. I think, at one time, I wanted artworks that felt so ‘pure’ in this way, that they seemed wholly alien, devoid of human intervention. Now I do not find that so interesting. I think, lurking behind this impulse, is the demand for novelty, that each work an artist makes will be ‘new’ in some demonstrable way, that it have an original concept or (what amounts to the same) gimmick. Purity, novelty—so many reductions. Enough with all that. —Mark Cutler

Thank you for reading the seventeenth issue of Film Show. Support your local theaters.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.