Film Show 015: Media City Film Festival, 2022

Reviews of 15 films from the 25th edition of the Media City Film Festival

Media City Film Festival is one of the greatest contemporary festivals because they’ve remained highly committed to showcasing avant-garde works from filmmakers around the world. For their 25th anniversary edition, MCFF held free, public screenings online between February 8th and March 1st. Of the 70+ films available, I found myself enraptured by more than half, and below you'll find reviews of 15 I consider highlights. Some are old, some I’d already seen, and some were premieres. All, however, are worth checking out. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

The Newest Olds (Pablo Mazzolo, 2022)

Pablo Mazzolo’s The Newest Olds is a film of evolving juxtapositions. At first there’s a shot of the Detroit skyline at night, its dim lights suddenly giving way to flickering superimpositions of the same image at varying stages of the day. The impression is of watching any space momentarily brighten from a lightning strike, but the shifting blues and greens that seep into the sky bring everything into a more beguiling territory. The non-diegetic sound—recordings of Black people talking, police radios, and sirens—seems to animate Detroit itself. The constant, spectral vibrations of these buildings can only signal uneasiness.

Mazzolo then moves to beautiful close-ups of water. He uses this passage to indicate our move towards Windsor, Ontario, the neighboring city from across the Detroit River. When people start talking, the contrasts between these bordering areas becomes instantly clear. There’s an obvious difference in race gathered from bits of chatter, but there’s a specific focus on a low oscillating tone, too. We see rippling water—something that draws our attention to sound and its effects on landscapes—and then hear a news report of birds dying (it’s not uncommon for birds to suddenly die from specific noises). For these locals, this is the sound that signals death, and not of themselves, either.

In the film’s final act, Mazzolo ties everything together: we’re back in Detroit and hear a protest, chants of “Hands up, don’t shoot” filling our ears. He focuses on skyscrapers, and uses more dramatic superimpositions to show a city turbulently shaking. So many experimental films that focus on buildings, from Andy Warhol’s Empire to Ernie Gehr’s Side/Walk/Shuttle to Guy Fihman & Claudine Eizykman’s Maine Montparnasse, focus on the camera as a tool for capturing transformations in—or of—a city. While optical printing effects are obviously in play on The Newest Olds, they’re pointing towards something external to the filmmaker/the medium leading to change. And as we hear people clamor for justice, they want a reversal; their own sounds can indicate death, one of the current iteration of Detroit. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Happy Valley (Simon Liu, 2020)

While any highly populated area is conducive to change, there’s a lovely queasiness to the editing, soundtrack, and camera movements in Happy Valley that present Hong Kong as a place in constant flux: sounds are often fractured and looping, everything’s spiraling around or flickering, and there’s this lovely ambiguity upon which Simon Liu lets his images hang. Among the many elusive objects he focuses on: crushed bricks, colorful umbrellas, and something floating in the air he only captures via its shadow. The occasional horror-film atmospherics and mangled pop songs suffuse everything with an unsettling ambiguity, but they’re offset by shots in daylight where the message is more direct: Happy Valley—the titular residential area—is filled with traffic and everyone wants to “Exit Congestion,” as one road sign reads.

There’s this sense that everything’s going to burst at the seams, of something new needing to arise, and that’s bolstered by the initial shots of fire where the spirit of protest looms large. When we see a crowd of people standing underneath a massive whale replica at a mall, this sense of impeding doom is countered by a massive aquarium filled with real fish—they swim around in massive number, and it’s mesmerizing how monumental they feel compared to the towering creature we’d seen earlier. Later, Liu rests his camera on a statue of Sir Thomas Jackson, a chief manager of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation during British colonial rule, before pointing his camera at a hole in the ground filled with bricks of varying sizes. Every locale has constituent parts that make it what it is, that hold everything up—will we stay in this bleary hypnagogic haze forever, or tear down and start anew? —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Merapi (Malena Szlam, 2021)

While researching Merapi, the most active volcano in Indonesia, I stumbled upon paintings by the artist Raden Saleh. There are two in particular from 1865—Merapi, Eruption by Day and Merapi, Eruption by Night—that provide similar but contrasting views of the mountain. In the former, plumes of smoke trail behind molten rock, the whole scene turning into a dull grey-brown. The latter is more terrifying: the moon is bright but feels negligible compared to the lava spewing out, which casts red light upon trees and rocks. This is typically how one would go about depicting a massive and important geographical landmark: by centering it. A film like Arthur & Corinne Cantrill’s The Second Journey (To Uluru) spends its runtime presenting the titular sandstone formation as the true monolithic structure it is, which in turn makes it feel even more mysterious. Malena Szlam’s Merapi operates differently: Szlam resists focusing too much on the mountain; she knows that doing so would too easily reduce it to a tourist attraction.

Szlam starts Merapi by enmeshing us in tree branches. In this small, unknown space, smoke fills the sky—a reminder of the deadly aftermath of volcanic eruptions. These images are quickly cut between black screens. In beginning her film this way, she prevents us from settling into the environment or feeling like we can “get” what Merapi’s all about. The lack of sound throughout the film also makes this a purely visual encounter, preventing any ambient noises of nature from letting viewers feel too relaxed. When she eventually shows us Merapi, there’s this almost preternatural green defining the foregrounding flora, and it blends with the sky’s soft cyan as if the whole image is a soft-hued mist. What follows is a playful series of images that constantly disrupt: with each shot the slope of the landscape shifts, as does the location of the sun—something that diverts our attention away from the mountain at the center of the frame. I can imagine a viewer growing restless: “Enough! Let’s see the mountain! Stop distracting us!” Her response is to employ a slick R-L pan.

Merapi continues in this manner for the remainder of its runtime. Though there are moments that rest on the volcano itself, this is never a film about directly perceiving its subject. Superimpositions constantly appear, and these overlapping images are as evocative of Merapi’s sacredness as the massive clouds that cloak it. As a study of light and clouds and color, Merapi is lovely, but Szlam also knows that focusing on these facets highlights Merapi itself. I think about Mbah Maridjan, the juru kunci (spiritual guardian) of Merapi until his death in 2010. He chose to die when the volcano was erupting, and his ash-covered body was found in a position of prayer. “Please go down,” he reportedly told his son. “But it will be cowardly if I do so. It is my time to go.” Several people live on the mountain’s slopes despite the obvious dangers, as doing so makes them feel like they’re a part of Merapi itself, involved in a relationship that connects them more deeply with their spiritual beliefs and the surrounding environment. Compared to Raden Saleh’s paintings, Szlam’s film helps us feel the impact of the volcano on its surroundings without ever showing eruptions or humans. We feel its power even when the mountain is obfuscated, or when we avert our gaze: Its mystical images are miraculous. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Glimpses from a Visit to Orkney in Summer 1995 (Ute Aurand, 2020)

Ute Aurand’s films are diaristic in a surprisingly rare manner: they depict life as something defined and understood through others. Her works are never solipsistic or about film qua film; they’re odes to the relationships and people who’ve made her life as beautiful as it is, and any jump cuts or shaky camera movements are a means of making such vivacity palpable. This social dimension makes her films light-hearted, sensitive, and immensely affecting even across short runtimes. Am Meer (1995), for example, is mostly just shots of a beach. We hear director Utako Koguchi singing and playing piano on the audio track and that’s enough to suffuse the images with sentimental feeling.

Aurand’s Glimpses from a Visit to Orkney in Summer 1995 clocks in at a lean four minutes and is another one of her masterworks. It was commissioned by writer and curator Sarah Neely as part of her “Margaret Tait 100” project. While we do see Tait’s face for a brief moment, this is a decidedly more poetic venture, using full-screen bursts of color alongside more typical shots of the titular archipelago to evoke major emotions. No sound is present because it isn’t needed. I was reminded of A Field Guide to Roadside Wildflowers At Full Speed, a tongue-in-cheek e-book meant to aid wildflower enthusiasts who don’t have the time to spend hours identifying flora. The author provides images and descriptions of butterfly milkweeds and Canada goldenrods as one would see them from a car driving at high speeds. These smeared photos are a delight, not just in their amusingly blurred colors, but in their representation of our innate desire to feel beauty in a time when we’re increasingly busy.

Glimpses has a similar understanding and embrace of ephemerality. It begins with a quick succession of close-ups, the radiant colors of varying flowers filling the screen. The camera occasionally pushes up to their petals—like a POV shot of someone trying to smell them—and it’s in this moment when the camera crashes into them that we understand where these colors presumably originate. What Aurand does is extract the beauty of the flora (and at one point, a horse), and magnifies their greens and yellows and blues into pure, evocative emotion. It’s hard not think of Tait’s A Portrait of Ga (1952), her own four-minute film about someone she admires—her mother. The Scottish poet and filmmaker presents quotidian footage that ends up feeling extraordinary, not because it’s unusual or of such exceptionally beauty, but because it documents the particulars of a person’s being—the way one’s hair hangs, how one walks across a field, the care with which one opens a candy wrapper. Consider Glimpses an attempt to do the same but in a more roundabout manner: Aurand takes these simple images and in their abstraction captures specifics about this time and place.

In 1997, Tait wrote the following:

The contradictory or paradoxical thing is that in a Documentary the real things depicted are liable to lose their reality by being photographed and presented in that ‘documentary’ way, and there’s no poetry in that. In poetry, something else happens. Hard to say what it is. Presence, let’s say, soul or spirit, an empathy with whatever it is that’s dwelt upon, felling for it, to the point of identification.

Glimpses, in its atypical documentary mode, manages to bear that ineffable “soul,” one that’s less identifiable through words than feelings. As an homage to Tait, it couldn’t be better. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Não são favas, são feijocas (Tânia Dinis, 2015)

I’m always surprised by my mother when she tells me that her life isn’t interesting. I ask for stories of her immigration experience, of her childhood, of anything, and she’ll be reticent to share unless she feels it’s really worth doing so. I get it: why linger on the past, especially if moments were difficult and confusing, when we can focus on the now? Sometimes there needs to be a reason for her to release something from the private corners of her mind—maybe a new incident that reminds her of something from decades past. Such thoughts were running through my mind while watching Tânia Dinis’s Não são favas, são feijocas, a film that’s a transparent excuse to bring two people closer—in this case, the Portuguese actress/filmmaker and her grandmother.

Não são favas, são feijocas features little more than ten minutes of Dinis’s grandmother tending to her garden and animals. At the film’s start, she exclaims that watching this footage will be a “bloody waste of time,” but nevertheless sticks through it if only because it’s something to keep herself occupied. There’s sorrow when she sees her “sad way of walking” and how she looks like she’s “150 years old”; her oldness can’t escape her eyes anymore. But just as obvious is how she’s content with her current way of living. “We look so ridiculous,” she says before quickly affirming herself. “I don’t care what people think, I just want to do things my way.”

There’s humor, too, like when she shows off her burn marks and states that “those are a cook’s medals.” Dinis and her grandmother regularly laugh throughout the film, and as their commentary serves as the sole audio for these images—ones that were shot more than 18 months prior—there’s a excitement and joy in how these two can simply be with each other. In its tenderness I’m reminded of Naomi Kawase’s Katatsumori, another documentary about a director’s grandmother. This is a little more meaty though; it’s not just a loving tribute or the product of one’s desire to preserve memories, but a way to connect. In granting her grandmother a more participatory role—one that could’ve only likely come through home videos—Dinis finds a way to use her art as a conduit for intimate bonding. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

The North Sea (1973-1974) (Chris Kennedy, 2021)

Much credit needs to be given to Toronto-based filmmaker Chris Kennedy for having the most confounding film at Media City this year. I watched The North Sea (1973-1974) multiple times and wasn’t ever sure what to make of it. Kennedy’s formalism, though, is always a delight, serving as a means to regularly shift viewer expectations, be it with the mesmerizing grids that define Brimstone Line or the single-cartridge limitation of his Super 8 works. This time around he draws inspiration from Marcel Broodthaers’s A Voyage on the North Sea (1974), incorporating its book-like structure (images are separated by intertitles stating “Page 1,” “Page 2,” etc.), Cooper Black typeface, and focus on texture. Even more, there’s specific interest in Rosalind Krauss’s ideas surrounding the film and the medium in general.

What I most appreciate about The North Sea, though, is how it quietly draws so much out of its barebones material. Kennedy shows us still frames of men at a pool, and their bodies, swimwear, and a patio umbrella radiate this lovely orange-brown. The images occasionally repeat, as does the “Page 5” intertitle (something that also occurs in the Broodthaers film), leading to this unceasing sense of intrigue around what we’re seeing. Is there a body in the water? Why does it disappear later on? Why is Kennedy highlighting empty chairs, or the wall next to someone’s face? There’s a murder mystery spirit to all this footage, and every photograph—especially with their limited time onscreen—keeps me both anxious and diligent in examining every pixel for evidence. A third of the way into The North Sea, eventual flickering leads to seeing the actual film reel—something that reinforces our position as an observer—and it reminds me that this is filmmaking at its most pure: seeing images, making connections, and enjoying the beauty in every single frame. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

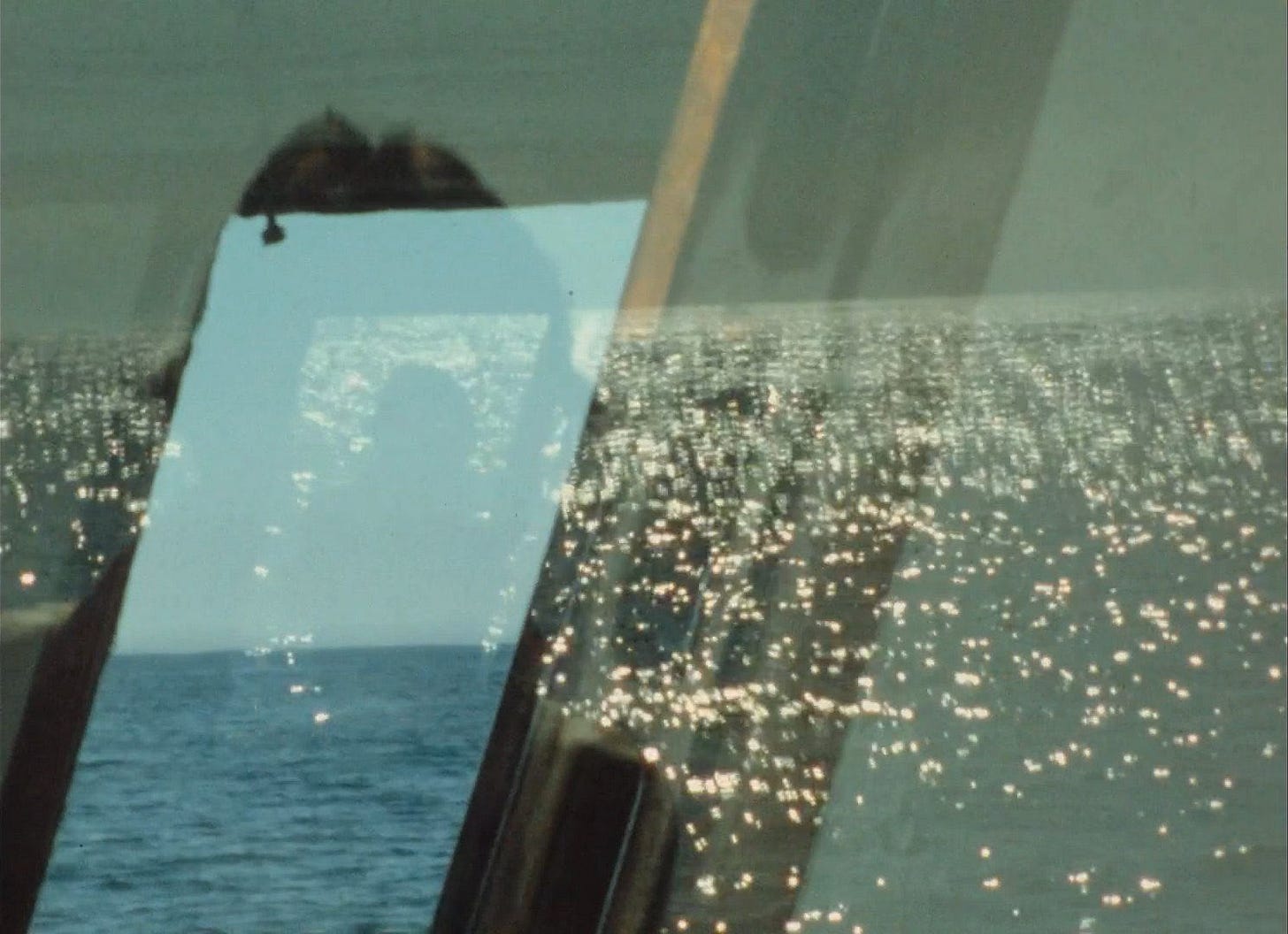

Whale Watch (1) (Joseph Bernard, 1981)

Compared to most of Bernard’s films, this 10-minute short has this tremendous feeling of expanse. It’s not that his other works don’t feel monumental, but that any awe that they provoke is usually reflexive, pointing to the artist behind the Super 8 camera and what he’s doing to make everything cohere. With Whale Watch (1), however, I’m allotted more time to feel the vastness of the ocean or relish in the beauty of the titular humpback—it feels less like an experiment than a tribute to something greater than himself. In his other water-centric films from 1981, there’s a large emphasis on abstraction as its own beauty: Intrigues (II) captures the playfulness and immensity of being submerged under water, while Semblance: Frampton Brakhage Relation is all about rapid movements and light creating kaleidoscopic images. Whale Watch (1) always lets its more avant-garde moments feed into the overarching mood. When rushes of water alternate with shots of a boat, there’s an underlying sense of anticipation and adventure. When dots of light reflect off water and fill the frame, they bolster the humpback whale’s own non-manmade majesty when it arrives, its body surrounded by resplendent, glorious yellows. Brakhage is the usual point of reference for a Bernard film, but the main work that kept coming to mind here was Teo Hernández’s Midi (1985), a similarly vibrant film that 1) never feels like a perfunctory assemblage of vacation footage, and 2) allows you to feel the magic of the space by forcing you into a constantly resetting mode of observation. Every superimposition and cut is a reminder to stay alert, and Bernard never lets you take these sights for granted. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Sodom (Luther Price, 1989)

Film has a way of disembodying human flesh and transforming it into pure abstraction. I imagine the first taste many people have of this phenomenon is through hardcore pornography, with extreme close-ups of thrusting genitalia and unavoidably awkward camera angles rendering the explicitly sexual into something alien. The first time one experiences this is a shock, and I felt a similar one when watching Sodom, the 1989 short film from the late Luther Price. Living up to its title, Sodom is a phantasmagoric collage of men fucking without any care for niceties. It’s a full-on orgy, gaping orifices aplenty, and everything glimmering with a striking red. He doesn’t want the decorum of Willard Maas’s Geography of the Body (1943) or the pop song-filled joy of Barbara Rubin’s Christmas on Earth (1964)—hell, this isn’t even in the same category as works from gay experimentalist forebears like Jack Smith or Kenneth Anger. Price goes all-in to live up to his title to deliver Biblical-levels of blasphemy, at least as larger society would deem it—indeed, even gay film festivals rejected the film at the time.

Price’s grimy footage cycles between more avant-garde passages and those that show clearer images of penetration, and it all churns until there’s relief found in strings of cum. These shots linger as if to provide necessary repose from the film’s catastrophic editing, but such stark-white globs also ground the film back in reality—consider it experimental film’s best depiction of “post nut clarity”—which only brings up a whole slew of emotions given the underlying atmosphere of rejection and otherness. Any facial expressions we see are ambiguous, easily read as sexual ecstasy or unimaginable pain: This is sex as transcendent and transgressive, life-giving and apocalyptic, heaven and hell. Price uses a Gregorian chant for the soundtrack—“Salve Festa Dies”—and then reverses it, recalling the outrage of conservatives regarding songs’ backmasked messages. In a less committed work, such audio would be too obvious, but the images are so enveloping that it can only prove affecting. Price leaves no room for anyone to consider this a “pretty” film because he has no desire to kowtow to mainstream sensibility, and that feels like the only real way to approach a film about gay sex. It’s immense and severe and like little else: it’s a stone-cold masterpiece. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

2020 (Friedl vom Gröller Kubelka, 2021)

Friedl vom Gröller Kubelka’s movies are lovely and lovingly brief, interested in presenting life at its most poetically simple. This is most startlingly obvious in the works that link her to Viennese Actionism: Im Wiener Prater (2013) focuses on a woman urinating in the snow, while Boston Steamer (2009) films someone shitting from the vantage of a toilet bowl. Compared to something like Kurt Kren’s 16/67: September 20th—an unforgettable film that rhythmically cuts footage of someone eating, drinking, pissing, and shitting—vom Gröller Kubelka aims for a more direct this-is-literally-what-our-bodies-do approach. The fact Im Wiener Prater is legitimately beautiful when a stream of piss falls on the camera speaks so much to her sensitivity—it never feels sexual or subversive, just tender and humane.

In 2013, vom Gröller Kubelka released a work titled Warum es sich zu leben lohnt (translation: Why life is worth living). In two-and-a-half-minutes, she films a woman at a dental office as various tools are plunged into her mouth. At the end, the patient waves her hand at the camera to signal she wants vom Gröller Kubelka to stop filming. The title, of course, is ironic, but it feels revitalized in her 2021 short film 2020. Once again we’re at a dental office, and terrors arise when seeing the overhead light or a mouth pulled open by the dentist. More important, though, is the numerous close-ups of teeth. Some are perfect, some have gaps, some are from canines, some are prosthetic. Regardless of what we see, though, the message is clear: one’s smile defines so much of who you are, and the pandemic has forced our identities to be partially lost through mask-wearing. The dental office—often only a site of horror in the overwhelming majority of films—becomes a more sacred space in 2020: it’s one of few public locations where people have to be unmasked. We end the film on a dental impression of vom Gröller Kubelka’s own teeth. She’s not one to turn the camera on herself, so she finds this playful workaround. It’s not strange or unsettling or anything negative: it’s just herself, her body, her personality. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Sea Series 23 (John Price, 2022)

Canadian filmmaker John Price has been working on his Sea Series project for the past 14 years. He was initially inspired by the Seascapes photographs by Hiroshi Sugimoto, an influence you can see at the beginning of Sea Series 23: Wide shots of the Atlantic Ocean are so grand that the sky, water, and sand become their own monolithic bands of grey. The waves flow at an irresistibly slow rate here, and the other defining qualities of this shot—flickering lights along the frame’s edges, quiet field recordings of waves and birds—make this a hypnotic moment of oneness with the world. That feeling is more deeply felt as the film progresses, using gentle dissolves to show clearer silhouettes of humans. Every image becomes a moment to see how small we are compared to the clouds that adorn the sky, or the waves that move elegantly in the background, and as colors start to appear, Price eventually lands on a more intimate setting: his children playing in sand. As one child is buried in it, we see how Price and his kids are essentially doing the same thing: letting the world overtake them, and finding bliss in the process. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

ON WATER (Kayla Anderson, 2020)

Kayla Anderson is a Detroit-based artist who released an EP on Jack White’s Third Man Records in 2018. It was with her band Serration Pulse, who are essentially a synthwave band with an electro-industrial edge—neither foul nor catchy enough to work as pop or something satisfyingly subversive. With her short film ON WATER, Anderson delivers a more potent slab of brooding mystique. She essentially films herself atop what looks like aluminum foil—material that works beautifully in reflecting light and instilling these two minutes with subtle queasiness. Just as important is the soundtrack, which is nothing more than a non-diegetic rush of wind and/or waves, adding necessary distance so that her images feel more alien. Naturally, the less we see of her the better, as shots of her hands and feet transform her body into something less personified. Still, there’s a thrill in seeing more: in one of the most striking shots, water spills out of her mouth, and her face becomes contorted in the ensuing reflection. ON WATER doesn’t always work—some of the digital edits are unnecessary—but it’s got enough amateurish charm for me to root for it. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Partial Differential Equation (Kevin Jerome Everson, 2020)

With more than 200 films to his name, Kevin Jerome Everson has made it extraordinarily difficult for anyone to watch his entire filmography, and it’ll only become harder as he continues to work prolifically. Being a completionist is thus out of the question, and this fact mirrors what his entire project is doing: In documenting everyday Black Americans, he’s proving that they’re not a monolith, and that one couldn’t possibly capture Black Americans in their entirety because it’s an impossible, never-ending task. With all the depictions of labor that characterize his films, Partial Differential Equation stands out for being one in which there exists a clear division and link between what’s unspoken (the mental processes of solving a math problem) and what’s seen (the numbers, symbols, and words written in chalk).

With 16mm film, Everson follows mathematician Tariah Gatlin as she solves this partial differential equation step by step. What’s crucial is that we never zoom out to see the full problem when this 9-minute short ends. I’m reminded of so many films that depict a Genius or Scientist solving something, and it’s the sheer volume of numbers—and the amount of space that’s filled up on a chalkboard—that stands-in for their brilliance. Everson doesn’t want to reduce Gatlin to such silly representations; he wants to make it clear that this is a legitimate feat that requires work. His close-ups are slightly awkward because Gatlin’s head is often covering a third of the screen, and when he moves his camera from one line to the next, he does so slowly, lagging behind as if to keep everything obfuscated from the viewer. It becomes a lovely meditative watch—one that’s less about figuring out what’s happening than simply witnessing the action play out, and becoming mesmerized by every little stroke. The audio track is also inconsistent with the visuals; we hear writing even when Gatlin isn’t using her chalk, pointing further to the ongoing unspoken labor at hand. There’s also, of course, the fact that partial differential equations have several real-world applications related to the labor depicted in Everson’s other films. As always, a new Everson work—as isolated in its portraiture it may seem—reminds us that everything’s interconnected. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Now Pretend (L.Franklin Gilliam, 1992)

There are two major ideas animating L.Franklin Gilliam’s Now Pretend that are constantly folding into each other. One is the notion that non-Black people refuse to understand what it’s like to be Black in America, especially via Black people. Gilliam uses John Howard Griffin’s Black Like Me—a 1961 book that follows the white author as he experiences life “as” a Black man in the South (he chemically dyed his skin to appear as such)—to prove their point. The book sold over five million copies and became a way for many non-Black people to understand the realities of racism. When we hear a white man and Black woman recite the same passage, their overlapping voices are a reminder of who’s often ignored and who’s often embraced. It’s hard to shake off how depressing this all is given how contemporaneous Black authors were writing about their experiences too. Still, much of the film’s grainy footage focuses on Black people in quotidian settings—a reminder that their lives can’t and shouldn’t be defined by tragedies or pain.

Of course, to dye your skin Black doesn’t mean you’re actually Black, so the accompanying message to Black Like Me’s popularity is that white people never really understood the truth. Despite this lack of knowledge, it’s evident that Black identity is still policed and judged. This is expressed via police tape with words that read, “At what point did you realize the politics of your self / difference.” We hear discussions about Black hair and the “checklist” that Black people have to evaluate their Blackness: the way they speak, what they wear, the music they listen to. A woman talks about her parents’ Trinidadian and Jamaican accents, and how deciding to speak either “American English” or “Black English” is something rupturing her sense of self. “Somewhere in the midst of that you have to decide who you really are, which voice is really yours,” she says. Blackness, as a result of white supremacy, is constantly interrogated, and is something that has no obvious, single truth; Blackness, then, is actually indefinable. When the film ends with another passage from Black Like Me—one that has the author reflecting on his perceived Blackness from others even after the experiment—the irony is clear: he, nor the white people he encountered, actually know about Blackness. And with this realization is a more hopeful point that Gilliam suggests: How could they know about Blackness anyway, when everything it could mean and encompass is infinite? —Joshua Minsoo Kim

A casa, a verdadeira e a seguinte, ainda está por fazer (Sílvia das Fadas, 2018)

I’m enamored with the grace that Sílvia das Fadas films the five locales in A casa, a verdadeira e a seguinte, ainda está por fazer (translation: The house, the true one and the one that follows, is yet to be built). She patiently documents each space to let them breathe, letting viewers feel the atmosphere emanating from every color and contour. Each location is one that feels isolated from its surroundings, that pushes back against the prevailing ideologies that govern our world’s downfall, cultural or otherwise. There’s Ferdinand Cheval’s Palais Idéal, a miniature castle that took the French postman 33 years to build, or William Morris’s Red House in Bexleyheath, which found the socialist activist aiming to construct a “world within a world.” “Popular art has no chance of a healthy life, or indeed a life at all,” he once said. It’s in this statement that we find the ambitions of agitators: the things in life worth fighting for are those that go against the grain, that aim for something beyond convention and complacency, that hope to use imagination as a key revolutionary tool. For the soundtrack, das Fadas pairs these locations with the equally ambitious work of musicians like Jacques Bekaert and Gerhart Münch. Their music is never overbearing, instead receding to the background. Don’t mistake them as ancillary, though; she’s merely hoping to be non-disruptive, to add a layer of artistic ingenuity to the proceedings. It’s easy to consider art secondary to so many things in life, but das Fadas reinvigorates us through these pieces that have lived beyond their creators. More than anything, these structures are testaments to art’s indispensable nature, that the inspiration they stir up ripples into all aspects of people’s lives. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Flowers Blooming in Our Throats (Eva Giolo, 2020)

With Media City Film Festival I was given my second opportunity to watch Eva Giolo’s Flowers Blooming in Our Throats. It was exactly one year since my first viewing, and the 12-month interim has made it obvious that this short is one of few memorable COVID films. You can credit that to its impeccable style: Giolo crafts something in the lineage of Robert Beavers’s From the Notebook of…, employing cuts that are as sly as they are sharp, every edit bolstered by an understated audio track that renders every movement expressive, sensual, and part of a bigger whole.

Flowers was made shortly after lockdown began and is a domestic film where Giolo and her friends perform simple tasks or gestures. At times they’re related to food, like peeling a potato or using a rolling pin to flatten dough, while others are more clearly related to play, like when we see a spinning top or two hands in the middle of a red hands game. Faces are wisely avoided to focus on the importance of these motions—any sense of the personal is removed to highlight graphic and audio matches—which then makes this a more universal portrait of lockdown’s peculiarities. The happiness we find in this time is reminiscent of a child’s, as indicated by seeing someone play cat’s cradle, but Flowers more broadly speaks to how hyperaware we become in isolation: every sound is striking, every touch more meaningful, every person we’re holed up with a much larger presence in our lives. Giolo uses a red filter to dramatize previously seen actions, and when they’re repeated, she reminds us of how this newly adapted sensitivity is a source of both joy and pain: nothing is as crucial as holding someone’s body in a time of extended loneliness, but doing so only emphasizes that greater, grimmer reality. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Thank you for reading the fifteenth issue of Film Show. See you at next year’s MCFF.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Film Show is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Film Show will be able to publish issues more frequently.