Tone Glow 064: Keith Rankin

An interview with Keith Rankin + our writers panel on Fatima Al Qadiri's 'Medieval Femme', Phantom Limb's 'Imaginal Soundtracking 2: The Demon' comp, and DJ Sprinkles's 'Gayest Tits & Greyest Shits'

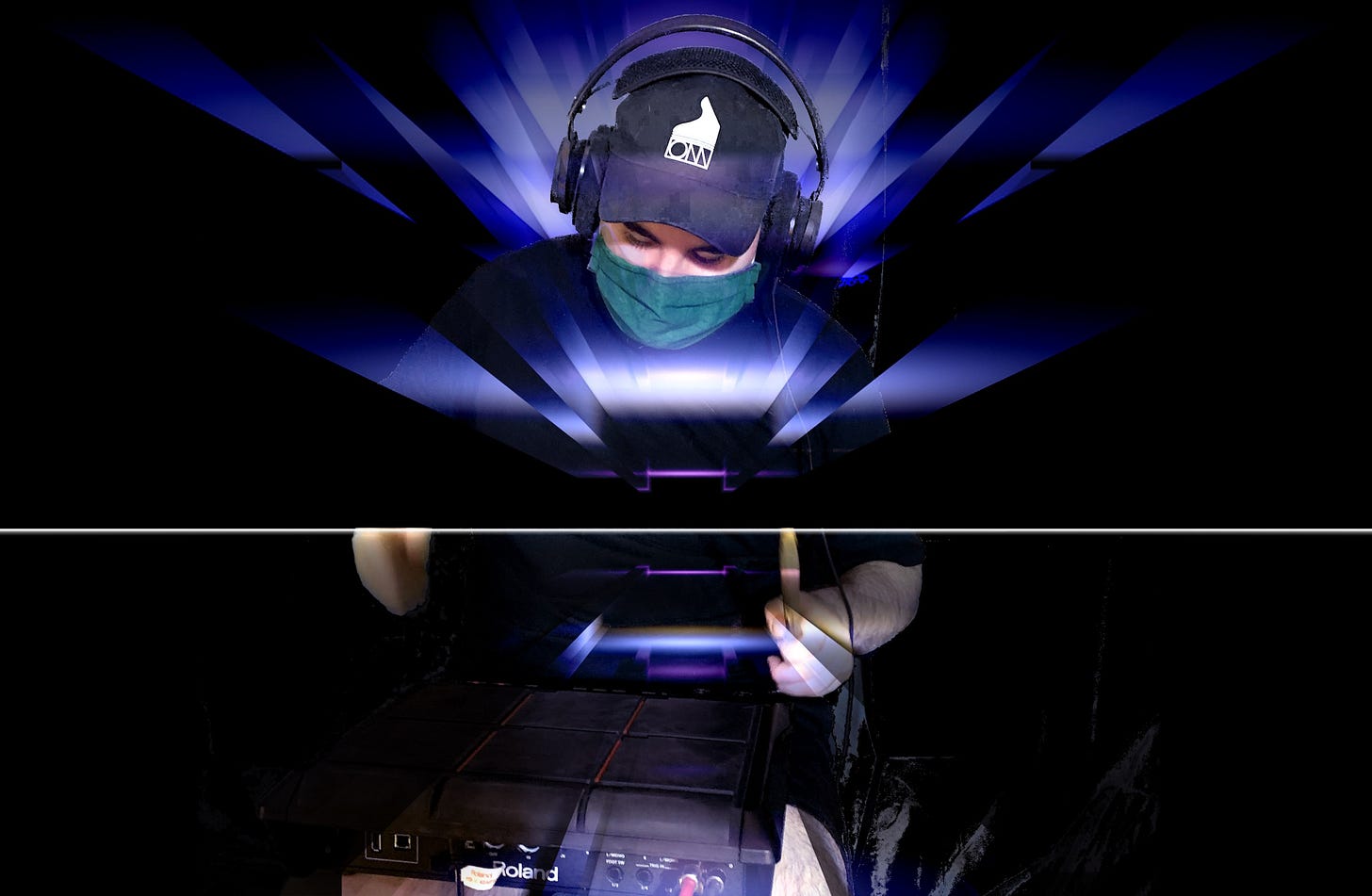

Keith Rankin

Keith Rankin is a musician and visual artist who records under the name Giant Claw. His work has come to be defined by its bricolage of dub, footwork, glitch, plunderphonics, trap, vaporwave, and other electronic musics. He also makes music as one third of Death’s Dynamic Shroud, along with James Webster and Tech Honors. His visual art adorns the covers of the majority of albums on Orange Milk Records, a label he runs with co-founder and musician Seth Graham. His newest album as Giant Claw, Mirror Guide, spotlights a virtual string ensemble and live vocal performances. Jinhyung Kim talked with Keith Rankin on April 7th, 2021 via Zoom to discuss growing up in the Midwest, anime message boards, the late composer Noah Creshevsky, the struggles of making independent art, and more.

Jinhyung Kim: Hey!

Keith Rankin: Can you hear me?

Yeah, I can hear you!

Hold on one sec, my video’s not working—oh, there we go. How’s it going?

It’s going okay! How’s your day been?

Okay! Just dealing with Photoshop (laughs).

Is that a usual day for you?

Well, it’s been going really slow, I can’t figure out why. But every time I click anything it takes 15 seconds to do the action.

Yeah, must be frustrating.

It’s so frustrating! (laughter).

Well, how’s lockdown been for you? Has your situation been changing at all, or is it just more of the same?

When lockdown first started, I feel like I didn’t… I was getting no work, basically. But it’s picked back up, and honestly, it hasn’t changed too much—my lifestyle was already fairly solitary (laughs). I just like to be at home and work on stuff. I imagine it was way worse for people who got most of their energy from going out and socializing; to suddenly not be able to do that would be way tougher than it was on me.

I get that—I’m also more or less sedentary in my normal life (laughter). Right now where I am, the weather’s warmer, people are going out more, more places are opening, a lot of people I know are getting vaccinated. So it seems like people’s moods are going up!

Where do you live again?

I live in the D.C. area! Before that, I lived in several different places, but the place I lived for the longest was Columbus.

Wait, Columbus?

Ohio, yeah!

That’s where I live! (laughs). When did you move?

I moved to D.C. in 2015. I was in Columbus both as a little kid and for a few years when I was in middle school and high school.

I moved here in—I want to say 2012? So I’ve been here for years, but it still feels like I’m getting used to it; it just takes me so long to get out and about and get a feel for a place. I still feel like I just moved here, even though I’ve been here for ten years or something? (laughs). What did you think of Columbus?

Well, when I was there in middle school and high school—those were formative years for me, so I did make a couple close friends that I still stay in touch with. I was in a suburban area and couldn’t drive, so I don’t know if I really remember the city; it’s more just the people, or my school, or things like that. But I do look back on it fondly.

Yeah, the place doesn’t really matter, especially when you’re that young. I mean, I grew up in Dayton, which is an hour or so away from Columbus. I guess the only impact of the place is where you would go for entertainment and stuff. There weren’t any destinations I was excited to go to, you know? It was all just stuff on the computer—that was the exciting destination.

I read that you grew up in Dayton, and I did want to ask you what that was like.

I mean, it’s just the Midwest. When I was touring, I would play all through the Midwest—it has such a different feel to me. I feel like every region of the United States—and probably the whole world—has these different rules of politeness, and Midwestern rules of politeness are such a part of me that it feels like a comfort zone. But in Dayton, there’s just not a lot. Like you were saying, when you’re young, it’s more about the people you’re around. There weren’t many people that I met who were on the same wavelength as I was, or had a lot of the same interests. So I made a few really good friends, but even now there’s only a few people I personally know really well and who I feel like I can bond with over music and my more intense interests, you know what I mean?

Yeah, I definitely relate. When you were growing up, what got you into music? I’ve read stuff you’ve said about hearing pop on the radio; were there people you knew that showed you stuff? How did music come into your life?

It was definitely radio. I just remember hearing a chord change on the radio and being like, “Oh my god, what is happening? What’s happening to me?” (laughs). “Why is it making me feel like this?” I can still remember that. There are a few moments like that that I just remember pretty well to this day; that was the catalyst for just being obsessed with music.

Do you remember the song? Or is it just the moment you remember?

Um, I do! I think one of the songs was by Green Day—I think it was the song “Basket Case.” I should go look at the chorus of that. I think it was a minor chord or something they played (laughs). I mean, I was really young, it was the early ’90s—it could have been anything! It could have been anything that had a minor chord in it or whatever. It was just the visceral impact of the basics of music, I guess. There are tons of moments like that.

Do you have any siblings?

Yeah, I have an older brother and a younger sister.

I was going to ask whether your parents or siblings had any influence on you, if there’s anything culturally that they introduced to you—or in general, whether they influenced your attitude towards those things.

Well, I was kind of a typical middle child, I guess. When I was in middle school, I got sick with mono, and… long story short, it was just a lot of things. I dropped out of school. And around that time, my sleep schedule got really fucked up, which still happens to this day. So it was just a weird family dynamic. I was closer to my siblings when I was younger, but when I was a teenager, there was quite a lot of distance between us, and we didn’t interact a ton. But the one thing my brother did, he was into sports and stuff—way into basketball—and I think I stole his Jock Jams CD (laughs). And he had a Shaq album, a Shaq rap album.

Oh, seriously?

(laughs). I think it’s been forgotten to time. But Shaq definitely released a rap album. I think I stole those two CDs from him and was into them. So that’s the biggest contribution from my siblings, I think.

I see (laughter). So, how do you first approach making music?

Well, it’s changed over time. More recently, I’ve been starting with a keyboard and improvising with that; for years, I was mostly on a computer. I was just talking about this the other day, but I look at my work from a few years ago—and I hear it in tons of other people’s work—it’s this way of working that feels so removed from the history of composition, where you’re writing with notes and timbre and rhythm and stuff. I mean, those elements are still part of it. But the way that you’re just going into hyper-detail on the computer, with EQ bands and compression and all this engineering and technical stuff. That side is such an integral part of a lot of electronic music now. I was just thinking how amazing it is that if you were to show that to someone even 50, 60 years ago, it would just be totally unrecognizable. Like, “What are you doing? What is this, is this music? You’re making music?”

So yeah, I love that. But I guess that’s all to say that in the last year, I’ve been trying to return to more note-oriented composition. That was a skill I used to have more, and I think I forgot it a little bit. So the album I’m putting out now is me trying to relearn some of that, or build those piano muscles back up.

So learning piano is how you got into composition and developed your understanding of music?

Yeah—my grandma had a piano that she gave to my mom, so when I was growing up there was a piano in the basement. And I would be down there for hours, just playing. When I look back now, the amount of time that I spent playing the piano when I was young is almost incomprehensible. Like, what could I do now for five or six hours of pure pleasure? I don’t know, binge-watch a TV show or something? (laughs).

I’m guessing you couldn’t have done that at that age back then, right?

No—I would have loved to, I think. Well, I did a few. I was way into anime back then, and I would get on these message boards and buy these really shady bootleg VHS tapes from someone. I think they were in Japan? They shipped them over, these shitty VHS tapes with handwritten labels—I think the person was recording from their TV or something. So that was my first exposure to binge-watching. I binge-watched this show Berserk from front to back, and I was in a cold sweat by the end (laughs). I don’t think my brain was ready for that much stimulus, it was just overload. It was incredible, though!

What other stuff did you consume—or consumed you? (laughter).

When I was young like that? I guess a lot of anime, a lot of role-playing games… what else? A lot of music. Were you into anime when you were young?

Not really. I do remember a couple Miyazaki movies my parents had on DVD, but they weren’t a jumping-off point for me; I didn’t grow up with TV anime or anything like that.

When I was really young, I was really into Lord of the Rings. I think I saw one of the animated movies and read The Hobbit. I wanted to draw every single character from The Lord of the Rings, and even The Silmarillion.

Every single one? If you’re counting The Silmarillion, that’s a lot! (laughter).

I actually still have this really thick folder of all these childhood Tolkien drawings. There’s some deep cuts in there—like, the vampire Thuringwethil, and Melkor, and all these obscure Silmarillion characters. It’s pretty amazing to look back on those!

I also was into Lord of the Rings, but for me it was the movies. My parents had the box set with the extended editions of all three, so I remember watching those a lot. I read the books once, but I wasn’t as invested in those.

Yeah, it’s hard. After the movies came out, I tried to read the books again, but the images of the actors had totally replaced my imagination. I could only imagine those actors in the roles at that point, which was kind of a weird sensation. Did you watch the special features, like the making-of documentary?

Oh yeah, I watched those too! I pored over those (laughs).

Those are incredible. I like those more than the actual movies! (laughter).

So this next thing touches on what we’ve been talking about already. You got into anime by being on those message boards and ordering those bootlegs, and you said the internet was a big part of your cultural exposure growing up—what else were you actually doing on the web?

Well, on the message board I was on, we had a role-playing game where everyone had a character—it was all text-based. You’d just make a post from your character’s perspective, and the next person would jump off of that; it’d be a few paragraphs at a time. So that was huge. By the end, we had Bibles’ worth of text. That taught me how to write, basically. I developed writing skills from just doing that every day, obsessing over that. I feel like this was right before—Facebook might have been around—but it was right before social media exploded. So yeah, the world of message boards, that was the realm I was way into. I would just be jumping between these forums and trying to insert myself into these little communities.

At that time, pretty much all my friends were from those forums. It was kind of a weird mental disconnect—I don’t know if I ever told people IRL about my online friends, because there was still this weird taboo of “No, that’s not real.” I remember one of my good friends online, she lived in the UK and was part of this six- or seven-person friend group, and she actually died of cancer. And I remember this because I was really sad about it—but I absolutely couldn’t tell my mom or any of my IRL friends, because they wouldn’t take it seriously, or believe that this connection was real. If that happened now, it’d be totally different; people’s mindset about online communication has changed drastically since then.

Gosh, I’m really sorry about that.

Were you into any of that online community stuff?

I don’t think so. A lot of time I spent on the computer was just playing Flash games. I was really into Lego as a kid, and I’d play the games they had on their site. They had message boards, too—I was also on those a lot, just writing my own stories and reading others’ stories and talking about them. I wasn’t obsessed, but that was still important to me.

Have you been on Discord at all?

Yeah, I have! Since quarantine began, it seems to be the preferred method of group communication.

It reminds me of some of the old message boards—more private, you know? I feel like a lot of social media… it’s weird, people are drafting press releases with every Twitter post or something. It’s just a bizarre way of interacting with people where you’re calculating your words. So yeah, I’ve always felt a little uncomfortable with that mode of communication, of crafting a message and sending it out. I mean, that’s my own neurosis (laughs). But I guess the more private communities are where I feel a bit more comfortable.

Speaking of community: When you were growing up as a teenager, did you get into music scenes in Dayton and meet people through that?

Yeah, a little bit. There was the harsh noise scene in Dayton, that was big. And there was a pop music scene too—I guess you’d say pop rock. I was in a few bands and stuff. The music wasn’t something I felt real deeply, but I wanted to have that experience of playing live music and stuff, so there was a bit of that. When I started doing Giant Claw stuff, a lot of those early shows were in the noise scene. And I remember there were some parts of my set that had soft synthesizer chords—like a pad synthesizer sound that was pretty consonant, playing a beautiful chord change. And every time that would come on in my set, I would just feel the room grow uncomfortable (laughs). Because everything else was just like (makes noise with mouth)—harsh noise, scraping contact mics on sheet metal and stuff. I mean, I loved that scene, but it still felt a little out of place for me.

So yeah, I’ve dabbled in live local scenes, but I still definitely prefer recording on the computer. Playing live has always been a big source of stress and anxiety for me. Like, I would tour and stuff because that seemed to be the way to make the most money. But if I had my way, I would just be recording and producing and sticking to that side of things.

I’m curious—what prompted your move to Columbus in 2012?

I feel like the period before that was… I just remember mentally feeling like shit constantly. Part of it was probably just hormones or growing up, you know? Your body just feels fucked up for reasons that you can’t even explain (laughs). So I was like, “Well, let me try moving—we’ll see if that does anything. A change of scenery, meeting new people, maybe that will change something.” I had also been working at this Chinese restaurant as a delivery person for five or six years or something, and I was like, “I just need to get away from this.” Sometimes, when I’d get a job, I’d be so stressed out when I first started—and then after a few weeks, a month, I’d get comfortable in it and… it’s just your life. And I would always have trouble exiting that comfort zone to start the process all over again. So yeah, I would stay at jobs way too long, to the point where I was like, “I need to get out of here.” Then at the end, I would just drastically quit and make a change all at once, in one massive spurt. You know what I mean?

Yeah, that makes a lot of sense. So you started Orange Milk Records in 2010, right, with Seth [Graham]? How did you guys get to know each other?

It was similar to how I met the other people [James Webster and Tech Honors] in Death’s Dynamic Shroud; we were in bands in Dayton and crossed paths. I actually first met Seth in a political science community college class that I never finished. I just remember him trolling the professor a bit or something, and I remember thinking, “Damn, what is this person’s deal?” (laughs). But then we met later because our bands played together. I assumed—I think he had a beard, and he just had a look that made me assume he was in the metal community, which I associated with a very unapproachable personality type. But when we met and talked, it was like, “Oh, he’s a very kind person, and I feel like I can express myself.” And we quickly realized that our interests kind of went beyond the music that we were currently playing, and that we had ambition beyond our circumstances. And when you’re in Dayton, and you meet someone like that, it’s like, “I have to hold on to this” because it’s a pretty rare occasion. So that’s how that started.

I’ve heard a bit about how Orange Milk came to be—you guys wanting to put out stuff you liked. So from those DIY roots, over the past decade or so, how has your guys’ approach to running the label—whether in terms of ethos, business, or curatorial eye—changed with time?

I mean, when it started, we just wanted to get our foot in the door. We were just happy that anyone would want to put their stuff out with us (laughs). Actually, the first two releases we planned were total disasters. We were gonna do this vinyl from this Chicago group called Ga’an—they kind of sounded like that ’70s band Magma. And their vocalist [Lindsay Powell], she records now under the name Fielded. But they had this amazing record, and I was so excited. They agreed to put it out, and we sent it to press; I’m pretty sure all the money we had invested in the label at the time went into this record. I showed the album cover to my friend Robert Beatty, who does visual art kind of similar to mine—he was an inspiration to me in those days. I showed him the cover art, and he was like, “Oh, I just did this cover art. It’s coming out on a different label, for the same album.” I was like, “What?!” So long story short, I realized that my contact with the band was an ex-keyboard player who was super bitter and trying to get revenge on the band.

Oh, wow.

So yeah, he was lying to us and gave us permission to release the record, even though it was already planned to be released on another label around the same time.

That’s crazy!

I was like, “What the fuck is going on?” (laughs). We ended up just scrapping the entire album and losing a ton of money. I was like, “I don’t want to work with this sociopath going forward, let’s just scrap it and be done with it.” So that was the first disaster. The second was for this group called Caboladies, who were an amazing abstract synth, avant-garde electronic group—I think they were from Kentucky. We had that all planned and ready to go, and then the group was like, “No, we don’t feel good about the recordings anymore, so we’re not gonna do it.” So Orange Milk started with those two utter failures. I’m actually amazed that we even continued past that point, because I just remember the feeling of being so demoralized from that.

I can imagine.

I’m sorry, I went on a tangent there. But I just remembered that, and I hadn’t thought about that in a while (laughter). Well, not a lot has changed about Orange Milk. I feel like we’ve gotten more specific in our taste over the years—you know, taste changes all the time. And we’ve built more of a community over the years, so there’s certain artists that we just want to keep working with. Like Koeosaeme, who we’ve done a few records with; he has another one coming out later this year. Other artists like Foodman. It’s nice to have these artists that we’ve been working with since they started, that we’re friends with now. I feel like that aspect is what we wanted when we started, and I’m glad we’re at that point now. We still barely make any money, though (laughter). That’s the struggle, I guess.

I definitely get the sense that there are a few artists who have been with you guys for a while and who helped to define what Orange Milk’s vibe or aesthetic is—it’s the kind of thing that comes with enough time.

I saw someone post a meme once that was like, “Orange Milk sounds like”—and then it was like, a can opening, a bubble popping, a basketball dribbling? (laughs). I think Foodman is a great example of that. There are certain artists that have started to be associated with the sound of Orange Milk. And you know, we’ve done so many different things that for me, it’s hard to pin it down. But the fact that has entered meme territory means it’s at a certain visibility threshold where someone can make a meme about it, which is like, okay, I appreciate that part of it (laughter).

I think I’ve seen that meme! It did have that kind of immediate resonance—like, “Yeah, this is Orange Milk.” You guys are definitely at that visibility threshold (laughs).

When did you get into Orange Milk? Were there any albums that you liked?

I think my point of entry was the Noah Creshevsky compilation.

Oh, really? That’s awesome.

Yeah! Just listening to it, and reading about Creshevsky a bit, I was like, “It’s really uncanny that this guy made these sounds all this time ago.” And it shares points of reference with styles of electronic music that I thought were very contemporary. But there he was doing this stuff in the ’80s.

That was pretty much my reaction too—I’d never heard his stuff until 2016 or 2017. Yeah, that was exactly my reaction. Like, “How have I not heard this before?” It sounds like such a clear antecedent to tons of stuff on Orange Milk.

Right—when I listened to other stuff on Orange Milk, I was like, “This all seems aesthetically connected and everything.” Yeah, I love that compilation. It’s sad that he passed recently.

It is… Noah was incredible. I mean, his history is so deep—he worked with John Cage and was a professor; he taught music and was hardcore into academia and stuff. And he could have just settled on those credentials or whatever. But he would communicate with a lot of Orange Milk artists after we started talking with him. He was extremely open, and he was interested in new music, and just had this openness that I’ve found really rare. Or maybe I just haven’t interacted with enough older composers (laughs). But I was taken aback by how open and kind he was.

You mentioned that your interactions and conversations with him were an inspiration for Mirror Guide. So I guess we can pivot to the new album? (laughs).

For sure, I can talk about that. I think the way that I came in contact with Noah was when my album Dark Web came out. I was using the term “hyperreal” to describe some of the music on it, and this journalist Scott Scholz messaged me and was like, “Hey, have you heard of Noah Creshevsky? Hyperrealism is his whole theory, and he goes deep in it.” So yeah, I think Scott Scholz connected us, and that’s how we started talking. I was really interested in Noah’s academic background, because he was deep in that, and he taught at Princeton or something. So he was just deep in that world. And I’ve always felt a little self-conscious about… I took some community college classes, but I never had a college academic experience—I don’t even really have a high school education. So sometimes I kind of feel like a dummy in certain contexts (laughs).

So for my new album, I would send Noah early versions of the tracks. And I was kind of feeling down on them, like, “I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing, I don’t know if I should even go in this direction.” But in some of our back and forth, he gave me a massive confidence boost of, “No, forget about the friction between academic and non-academic music, what you’re doing is valid in any of those settings.” Basically just saying, “This is music that I personally love… keep going!” So yeah, I needed that push to finish this. That was a massive boost. Honestly, I think he served that purpose for a lot of us—Seth and Nick Storring and tons of Orange Milk artists. He would give them that boost of, “This is legitimate music, this is music that should be taken seriously.”

For sure—that kind of external validation can be really helpful.

Yeah, especially coming from someone in another musical world than you. You know, you have your friends, but at a certain point, it’s hard to know if someone’s being honest with you or not, or if they’re just… validating you? (laughter). I don’t know. So to hear that coming from someone in that other musical world, someone who has been around for so long and seen so much, heard so much… yeah, it’s incredible. I would always ask Noah about academic stuff, like, “What kind of stuff are people writing there? Is it interesting? Are they experimenting with computer music?” I was just curious about what the hell was going on in that world. And he would always say, “It’s still a lot of piano and violin sonatas and stuff.” He was like, “If I hear another piano sonata, I’m gonna lose my mind!” (laughs).

Well, conservatories, historically—they’ve been hotbeds of experimentation, because they had the money, but they’re also steeped in tradition as well. So I feel like you have different sides to it.

I think my curiosity with that world is that it’s a bubble, but it’s a bubble of people who are theoretically geeking out over and experimenting with music in more computer-oriented, academic settings. I always had a bit of FOMO. Like, I would love to have the resource of working with a choir or an ensemble of musicians, that’s always been a goal of mine. I’ve always wanted to hear something that I’ve written be performed by other people and morphed into this other thing. In my mind, a lot of times when I’m making music at the computer by myself, I’m just imagining that this is gonna be performed by this ensemble or something. And it’s gonna blow my mind (laughs). One day…

You did mention that when you were composing Mirror Guide, you were thinking about things in terms of instruments, or a synthetic orchestra.

There’s this Philip Glass Ensemble live performance—it must have been from the ’80s, it’s probably still on YouTube. But I remember watching that and just thinking how amazing it was that those compositions were being performed super loud with those instruments in a live setting. It was like a loud band playing, but they’re doing all these intricate arpeggios and stuff. I think I remember reading that Philip Glass said that those performances from that era were like, ear-shatteringly loud. So in my mind, I was picturing that all these Mirror Guide pieces were going to be performed by the Philip Glass Ensemble—like, really loud (laughs). It was a fantasy to keep the compositions going, I guess.

It’s been a few years since you put out the last Giant Claw record—you’ve been doing a lot of visual art freelance and running Orange Milk since then. When you got around to concentrating on music again and finishing the album, did you find that your relationship with the music-making process had changed? How was it different this time around?

In the last year or so, it was harder to get that feeling of raw inspiration. And you know, I just have to assume it’s partly because of lockdown and stuff. Or maybe it’s because I’ve been so busy trying to make a living with visual art; I really had to put in the hours, and there were definitely some moments where I was trudging through it, just finding inspiration from a different place. And then after you break through that initial wall, then it’s the feeling of euphoria, which is what I assume a lot of musicians strive for. Especially when you finish a track, it’s just this—I can’t even explain it, it’s like the best feeling in the world!

So yeah, this album was more difficult, it was probably my most difficult album to make. I think that’s partially because it had been so long since I tried to utilize more melody, more traditional composition. I remember I had this one part—it was in one key, and then I had another part that was in another distant key signature. And I was like, “How the hell do I get between these?” A few years ago I would’ve just put a harsh noise bit, or bridged the gap with some silence or a sample or something. But this time, I was like, “No, I kind of want to just have this make sense from a more notational standpoint.”

In a lot of your music, there are climactic moments where chord progressions and sequences take on a blown out, dramatic role—and I think that was really honed in on [Mirror Guide]. Especially in the first half of the album, with those chord suspensions resolving with that dramatic bouncing ball rhythm. But I do feel that the harmonic continuity of it all came through more.

That’s good! It’s tough—like, I wish I was aware of more sound design music that has that element of traditional composition side by side, I guess. Because I love pure texture, but I also love notes and harmony. I was definitely trying to find a more equal balance. Honestly, it’s kind of two different disciplines. I think that was part of the reason it took so long—not settling for just one or the other, but trying to make something that combined those two worlds. I hope it worked! I don’t know… (laughs).

I really liked it! I do think the accelerating rhythm—what do you call it, the bouncing ball? I feel like that worked really effectively. I think that in an interview with RYM, you talked about this Myriam Bleau record on Where to Now? Records—Lumens and Profits?

I love that album!

I listened to that when it came out; I didn’t make the connection immediately, but when I read this interview, I remembered that album and was like, “Oh, wait, I see it!” (laughter). I heard the rhythmic thing you do on Mirror Guide.

I played with Myriam in Canada in 2018—I was performing the first song on Mirror Guide live at that point. And we kind of geeked out after the show specifically about that rhythm (laughs). That album you mentioned, I love that album so much; it definitely has that rhythm a lot in there too. I’d be improvising on the keyboard, and I felt my hands just naturally going to that rhythm. And I started picking up on it and being like, “This feels kind of natural.” So after that, I was more conscious of it and tried to highlight it a bit more. Even when I go back and listen to Soft Channel and pick out moments on there, it’s like, “Oh, it’s kind of on there as well!” Like, almost any time I leave the metronome or the grid of the workstation, I kind of gravitate towards that exponential acceleration rhythm.

I feel like Soft Channel was a distinct break with previous Giant Claw stuff in terms of leaving the rhythmic grid more. And I do hear strong connections between Soft Channel and Mirror Guide, especially the stuff that uses those string or orchestra plugins.

I think the big break with Soft Channel was… I want to say most of the things I did before that were on the grid. I’d stray from it occasionally, but for the most part, my workstation was set up with that grid as a kind of foundation or guide. And I think Soft Channel was the first time that I just completely got rid of that. Actually, James and Tech from Death’s Dynamic Shroud—I kept using that term when we were recording, that I had been recording “off the grid,” and they started making fun of me for saying it too much. So I got a bit self-conscious about it (laughter). I mean, what can I say? It did change the music a lot. It’s just a totally different feel when you’re not thinking in terms of a bar of music or a pulse. It feels more flowing—you can hear it in the music, I think.

To touch on the orchestra stuff: me and Seth got a hold of these—it’s this company called EastWest. They do these orchestra libraries for film composers and stuff. You know, you could work on CSI: Miami or whatever and have a string section that sounds semi-realistic. So we got a pretty expensive sample library. Well, it’s not a sample library; you play the stuff on MIDI, and the sounds are very realistic. So all the orchestra stuff on Soft Channel and Mirror Guide, and even some of my older stuff—all that stuff is performed on the keyboard. And you can go into the settings of this orchestra library and get a really up-close, dry sound, which I love. Like, I love that feeling of it being right in your ear, almost a little blown out—just a very present sound. If you take a lot of these libraries, or VSTs, and push them a little past their intended use, you get this kind of magic, this sound that really appeals to me. We’ve used those sounds to death, me and Seth have (laughs). It might be time to retire them soon. I think they’ve run their course.

One of the most notable things that’s new on Mirror Guide is the performed vocals—there’s the spoken stuff by… how do you say it, NTsKi?

N-T-S-K-I.

Oh, you just spell it out like that?

Yeah, her name is Natsuki, so it’s N-T-S-K-I.

Got it—so, NTsKi’s vocals, the spoken word stuff—and there’s these sung performances, too. I don’t think I’ve heard that on a Giant Claw record before! So I was wondering how you came to have these performances in the compositions?

I mean, I’ve always loved working with vocals. But I’ve always had the problem of not really knowing many people in real life who are into the same music that I am and would have vocals that would be appropriate for the music. So because of that, I’d relied on a lot of pop a cappellas—vocal a cappellas I would find online. And then I would chop them up into single syllables and rearrange them into new melodies.

I’ve always wanted to work with more continuous, live-performed vocals. So I contacted this vocalist I know, Tamar Kamin, who’s in this indie rock band called The Van Allen Belt. And our music is extremely different—like, totally different musical worlds, I would say. But I just started imagining what her vocals would be like in this other context. She even appears on Soft Channel in a few places; she sent me clips that I edited into the tracks. But on this one, I actually went to where she lives in Pittsburgh, and we recorded for a few days. We generated tons of material, a lot of improvised stuff: I’d just be playing the keyboard, and she would sing along to what I was improvising. A lot of that material is what made it onto the album—just picking out these little improvised moments that had a spark of interest. Getting away from the cut-up, chopped sound just felt really good to me.

As for the NTsKi vocals: she had actually recorded vocals for me and the artist Holly Waxwing. We had been making music, and she recorded vocals on a song, but then that project was shelved or put on hold for a long time. So I just took her vocals from that and edited them into this new stuff I was making. It almost was like my old method of working with an a cappella, but I didn’t cut it up nearly as much; I left it pretty much intact and just composed around it. I feel like the moments with her on the album are some of my favorites—where it’s more still, where there’s just synth pads and her vocals. I don’t know, I just think those moments are so beautiful. I really want to do more with her. I just did a track—well, she has an album coming out on Orange Milk. It’s so good, it’s incredible! And I just did a remix for one of the tracks on that where I took her vocal and wrote a new track underneath it. I’m really excited about that. There’s definitely way more for me to do in the area of working with live vocals. If anyone reads this interview and wants to work with me, hit me up! (laughs).

Yeah, we can definitely leave this part in. Maybe we’ll insert your email address right here (laughter).

I’ve cold messaged a lot of people and been like, “Hey, do you want to collaborate?” And I have to acknowledge that it’s kind of awkward to collaborate with someone you just don’t know, you know? There’s always that element too. I always feel a little weird asking people when we know nothing about each other; we’d have no foundation to build on. So I guess on this album, I chose people that I trust a little more, or at least were in my sphere. Like, Natsuki has worked with Foodman and CVN—there’s this Japanese Orange Milk crew that I would consider her a part of. I like the feeling of working with people who are in your sphere, that you can trust and know a bit more.

That makes sense! So, one last broad subject I wanted to touch on was the visual art that you do. Actually, I meant to ask about the art for Mirror Guide—it’s credited to you and Ellen Thomas. Who contributed what in the making of that cover?

Sure! Ellen is my partner—we’ve lived together and been together for a long time, since 2013 or something. And we’ve always collaborated on visual art. It usually takes the form of me making a digital collage—then we’ll print that out, and she’ll paint it. And it takes on this whole new texture, this whole new feel that I think is incredible. The ones we’ve worked on together are some of my favorite pieces I’ve been involved with. For the Mirror Guide cover, the collage was really simple—it was just this empty Boeing airplane, this picture I’d seen online; it looks so familiar, but so bizarre sci-fi. It just made me think of how our present world is a bizarre sci-fi world from a lot of viewpoints, you know? Even from our position, if we were to step into certain industries and really get into the minutiae of how they operate, it’s just mind blowing, the levels of technology that are going on. So it made me think of that. And then I just plopped that hooded figure in the center of that—almost like a Lord of the Rings-looking figure, from a very different world from that hyperreal technology world. Yeah, it was just those two elements that I thought were evocative. Most of the hard work was on Ellen’s part for that (laughs).

That’s cool! I mean, on a lot of Orange Milk album art, there’s collage stuff. And there’s also the Giant Claw album covers and others that have that blend of the plastic and synthetic and collage-like with painterly elements and more traditional art. That synthesis definitely reads as one of the label’s visual art signatures.

Yeah—I mean, my usual visual art method is essentially just painting in Photoshop. I do a technique similar to physical airbrushing, just on the computer. People ask me a lot for visual art tips or whatever, but it’s really just similar to painting: blending color, considering how light hits objects, stuff like that. But when it’s on the computer versus when it’s on a canvas with oil paint, it’s a way different feel.

I was thinking that the cover for Gasp by Seth Graham, or Reanimator [by Noah Creshevsky], or a lot of others with various objects and symbols isolated in stark landscapes—it’s very late 19th, early 20th century Surrealist to me. Is that an influence for you?

Well, I’ve said this in interviews before, but every time I see an image I like online, I save it. And I’ve been doing that for years. So, like you mentioned, the early Surrealist period, I love that stuff. But that also permeated into ’80s and ’90s advertising in a way that I don’t hear mentioned as much. I think what’s almost a bigger influence for me is the second, third, fourth wave absorption into culture of that early Surrealist vibe, where people have internalized that. Because I’m sure early Surrealist stuff—like, whenever there’s an art movement that just starts out, there’s this initial shock to the system, or a shock to the culture.

I guess you could call it an initial novelty or something. It’s like comparing early Merzbow to harsh noise in 2021 or something, you know? There’s just a gulf of contextual difference between the two. But I love when an initial style like that Surrealist style becomes internalized by people and they play with it as an accepted base of reality. Like, “We understand this—now what can we do with that?” There are a lot of Japanese airbrush artists from the ’80s and ’90s that definitely have that going on—they’re just taking that Surrealist stuff to wild extremes, or mixing it with realism to a really cool extent that I like a lot.

I think that’s interesting—what you said about that “initial wave,” and how it’s the later movements, or other vectors of transmission, that are, in terms of cultural reference, more immediate for you. I guess it’s funny that I assumed direct Surrealist influence… I think it has to do with my own lack of knowledge of that in between stuff. So I just take what I’m aware of—in this case, late 19th century paintings by dead white dudes (laughter) and Orange Milk album covers—and I’m connecting those two.

Have you ever seen Instagram posts where someone will comment, “First”? There’s excitement about the first instance of something—this obsession with who did it first.

With originality, you mean?

Yeah! I mean, I guess there’s something to that. Like, people should get credit where credit is due. But in general, I feel like culture just moves in larger waves. I’ve seen this thing happen a lot before where all these artists I know, they’re on the cusp of these ideas, and then one person will release something that crystallizes those ideas. And that pushes this wave forward, because everyone sees that and is like, “Oh, this is a guide for how to actualize these thoughts that I’ve been having that were vague, or that I hadn’t formed solidly enough to make something stable from,” or whatever.

So yeah, it’s like culture happens in giant swathes, and we’re all riding that—we’re all part of that in a way. I think it’s interesting to look at the peaks and valleys of those cultural waves and the flow of trends and stuff; a lot of times you find some wild stuff in the third or fourth iterations of a style. Do you have any background in visual art or anything?

Not in visual art! My visual sense in general is actually a weak point (laughter).

Like, you have bad eyesight or something?

I actually do, but that’s not what I was talking about (laughter). As far as background in the arts, I took piano lessons for 13 years or so.

Wow! Did you start young?

Yeah, I started when I was five or six. I took piano lessons, played classical stuff.

So you are kind of familiar with the classical world, I guess?

I wouldn’t say I’m familiar with the nitty gritty of how the world of conservatories and contemporary classical music works, but I have a base knowledge of classical music history and theory.

Do you think it’s useful to have that? How do you use that?

(cat crawls onto Keith’s desk). It looks like your cat is—(laughter). What’s your cat’s name?

Payne! P-A-Y-N-E (pets Payne).

Hi Payne! I thought I saw a cat earlier—I don’t know if it was the same one or a different one, I couldn’t tell—wandering around in the background?

Yeah, we have three cats!

Oh okay, probably a different one then (laughs). Anyway, as for classical music theory, the more the music I’m listening to aligns with those compositional values, the more it’s useful descriptively.

Yeah, that makes sense.

It’s a banal point to make, but that’s kind of how it is, I think. I think a lot of the stuff I got into starting in high school didn’t necessarily align with that. But I wasn’t that into experimental music yet, so there was still a lot of diatonic stuff—music that was still relatively note-based and rhythm-based. So maybe music theory was still helpful for grasping a cool chord change, or a weird rhythm, or something like that.

It’s funny—I’ll watch some YouTubers who are music theory people, and they’ll be flipping out over an Earth, Wind & Fire chord change or something. Like, “Listen to this modulation, holy shit!” (laughs). I just always think the general listening public has internalized these more “complex” chord changes, or a more general sophistication about harmony. So a lot of these technically impressive harmonic feats are just—like, no one cares anymore. It’s only the music theory YouTubers who are having their minds blown (laughs).

Well, it’s kind of like describing the same thing in different languages—something may be a simple word in one language, but to describe the same thing in another language could require more complexity, because you’re coming at it from a different angle.

That’s a good way to put it. And honestly, I watch those YouTube videos because when I hear songs—the complex, harmonic stuff, I’ll hear it and I’ll be into it, but it goes over my head a little bit. So hearing people break it down and feeding off of their excitement lets me enjoy it from another perspective, you know what I mean?

Yeah, I get that.

And I also have to consider that there’s tons of really young people who are still—I mean, earlier I was saying how my first instance of being turned on to music was just hearing a really simple chord change. So I imagine there have to be really young kids who are hearing some YouTuber talk about jazz harmony and are getting their minds blown, which is an amazing function of those videos. Are you familiar with any—I guess you’d say more academic, new avant-garde music?

It’s not really my area, but there’s a few labels like New Focus Recordings that I keep up with.

I’m gonna write this down… New Focus?

New Focus Recordings, yeah. They focus on contemporary classical; they have a lot of stuff that’s from the conservatory world, I guess you would say, that’s still experimental.

Is Tzadik, the John Zorn label—is that in that world, too?

I don’t keep up with what Tzadik does nowadays, but yeah, definitely back in the day.

They put out what’s probably my favorite Noah Creshevsky album—The Four Seasons, that was on John Zorn’s label, I think? They used a stock image for the album art. I think when I saw it, I recognized it, like, “I’ve seen this stock image before” (laughs). I think Noah was always unhappy with a lot of the album covers he had. I think he did like that one, though!

Also—Room40 occasionally releases stuff in that contemporary classical vein. They had a compilation of some older stuff by this composer Beatriz Ferreyra, who was an important early electroacoustic composer.

Is that Lawrence English’s label?

Yeah, it’s his!

Wow, I haven’t heard from him in a long time. I need to look that up! So I used to work at Tiny Mix Tapes.

I did want to ask you about that! I knew you did, and I was trying to look up stuff by you on TMT, but I couldn’t find much. How’d you start?

I need to keep all my old reviews buried (laughter). Too embarrassing!

So you wrote reviews?

When I started I did reviews, but then I switched to editing people’s stuff. The bulk of what I did was just fixing people’s grammar and sentence structure—which is ironic coming from a high school dropout who doesn’t know anything about sentence structure… I barely even know what a verb is (laughs). But regardless, that’s what I was doing a lot of. And I would contribute a lot to the Chocolate Grinder section, which was just finding single tracks and putting them up there.

Right… I miss Tiny Mix Tapes.

Oh yeah, the Tiny Mix Tapes community was incredible. It spawned a lot of interesting writers and musicians. A lot of people who were in that orbit have gone on to do some amazing stuff.

Tone Glow’s home to some!

Is Sam Goldner there?

Yeah, he is!

I know Josh was gonna interview [site founder] Marvin [Lin] from Tiny Mix Tapes. I don’t know if that ever happened, though. I always champion Marvin Lin; I think he pushed abstract music forward in a way that doesn’t get mentioned enough. He was such an influence behind the scenes for a lot of the community. And the job of running Tiny Mix Tapes was such a thankless one—you know, no money involved. He’d always resist. Like, he could have gone the Pitchfork route and gotten absorbed by a bigger company or have more advertisements. But yeah, he gave up money to maintain that freedom to cover what they wanted to cover, you know what I mean? It’s sad that it’s over.

Were you in touch with him before you got on board with Tiny Mix Tapes? How did you join?

That’s funny, it was on that anime message board I mentioned. There was this writer, Katiedid—she was on that message board also.

Oh, okay!

And we’d talk about music, and I randomly just applied to Tiny Mix Tapes, way back. It must have been around when it first started, the very early days—like, 2007? No, way earlier than that, maybe 2003 or something?

I thought it was the early ’00s, right? 2001 or so?

I think it was 2002 or 2003, I can’t—my dates are fucked up (laughs). But yeah, funnily enough, it was through that anime message board.

That’s a wonderful story! (laughs).

My name was Keith Kawaii, which—you know, kawaii is “cute” in Japanese. And that’s directly from the anime message board.

I like how this all came full circle!

(laughs). It’s kind of embarrassing, I don’t know. A lot of times when you’re reviewing music—like, people read reviews and kind of look at them as these definitive statements on an album. But they don’t realize how often writing is just, “I have to think of something.” And there’s a lot of bullshitting involved sometimes, or just a lot of guesswork, like, “I think this makes sense.” I think a lot of reviewing has to do with projecting confidence about a subject, which was why I stopped. I feel like every review, I just had to break it down to the raw materials: “What is taste? Why do we like things? Why do I gravitate towards this?” And that just felt exhausting to do.

I feel you (laughter).

You do reviews too, right?

Yeah, I write for Tone Glow!

How’d you get involved with that?

I’ve always been into music, but I hadn’t really done music writing, I guess—other than diary entries from when I was in high school (laughs). But when lockdown began, I think I saw a Pitchfork review—and the guy who wrote it was Joshua [Minsoo Kim]. And the name all my friends and family know me by in real life is Josh—I have my Korean name, which is what I use for bylines, but my friends know me as Josh—so I’m also Josh Kim.

So I saw this other Josh Kim writing about an experimental album, and I was like, “Oh, this is interesting! What else does he do?” And that’s how I found out about Tone Glow. So that inspired me to start a Substack and write about newer experimental stuff. I also started this other Substack where I write with other people about music. Eventually, I got in touch with Joshua, and then I ended up writing for Tone Glow.

That’s awesome! Yeah, I feel like those mailing lists and Substacks and stuff are replacing a lot of the old blogs. Is that the sense you get as well?

That’s what other people tell me—I didn’t start writing until last year, so I never had a blog or anything like that, and I didn’t read a bunch either. So I’ve heard about how Substack and the whole newsletter wave are replacing blogs and older media. But I don’t feel any kind of loss because I never participated initially.

Yeah, it’s just a slightly different format. When you think about it, nothing much has actually changed. It’s just a slight format tweak, you know what I mean?

I guess there’s also this premise of people wanting things in their inbox as opposed to multiple sites that they keep tabs on and check. But on the basis of content, the vibe is kind of similar.

I mean, at least from what I’ve seen, it feels like the music writing world has shifted a little bit. Maybe it’s just because I was so interested in Tiny Mix Tapes. But since that left, it feels like places are less eager to cover emerging stuff. With a lot of places, it’s more about clicks, I guess. Which, I mean, makes sense—it’s difficult to make money writing about music unless you’re writing about Ariana Grande and stuff like that. But coming back to Tiny Mix Tapes or Tone Glow. Sadly, it takes people who are willing to give their own time with barely any pay to prop up a small segment of the culture. I wish there was universal income or something—like, artists could just get paid (laughs) and feel more free to do these things without, you know, the crushing weight of money.

For sure. The fact that Joshua does this not only at a net loss, but also in addition to teaching full time and everything, is really something.

Yeah, it’s wild. The thing is, I feel like he’ll get burnt out. He probably is already, but the burnout becomes inevitable when you’re pulled in so many directions. I feel that with Orange Milk; it’s the same situation. We’ve started paying ourselves when we do album covers—we’ll pay ourselves a few hundred dollars for the labor of doing an album cover. We started that last year, but prior to that, we never paid ourselves for that.

Oh, wow.

All the money we make has gone back into pressing vinyl and stuff. So it’s a similar situation—it’s just born out of loving a section of the culture. But you start to feel the strain of it when the weight of money comes in and you’re pulled in all these other directions. I hope Tone Glow keeps going, though!

I’d love to keep contributing! Okay, I think I’ve hit all the stuff I wanted to. One last question: Is there anything you want to talk about that we haven’t already? Or something you’ve always wanted to be asked?

Um, I can’t think of anything off the top of my head. I’m sure once we end I’ll think of ten things (laughs). But I think we covered a lot!

Yeah, I think so too. It was really great talking with you and getting to know your art and life—I really enjoyed it!

Cool, anytime. Me too!

Have a good rest of your afternoon!

Yeah, you too—thanks a lot!

Keith Rankin’s Mirror Guide is out now on Orange Milk.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Fatima Al Qadiri - Medieval Femme (Hyperdub, 2021)

Press Release info: Fatima Al Qadiri returns to Hyperdub, with a suite inspired by the classical poems of Arab women. Medieval Femme invokes a simulated daydream through the metaphor of an Islamic garden, at the border between depression and desire, where the present temporarily dissolves, leaving only past and future.

Since Shaneera, her last release for Hyperdub—a homage to hometown friends and a celebration of regional queer influences—Fatima recorded the soundtrack for French Senegalese director Mati Diop’s Cannes 2019 Grand Prix winning feature Atlantics. The restrained soundtrack to Diop's supernatural storytelling, sympathetically mixes neon drones and the faint outlines of Arabesque melody, intensifying Diop’s journey between worlds, rendering the complex emotions of the film.

Medieval Femme expands on ideas instilled from Atlantics to capture a fully realised, dreamlike setting, shaded with colour and subtle friction. The theme of the album is the state of melancholic longing exemplified in the poetry of Arab women from the medieval period. Fatima seeks to transport the listener to a place of reverie and desolation, to question the line between two seemingly opposite states and rejoice in celestial sorrow.

Purchase Medieval Femme at Bandcamp.

Mark Cutler: The thing about Fatima Al Qadiri is that her compositional style has never really changed. Each track, she introduces a few elements which loop and modulate, interacting in different permutations, and usually with a pitch change or two in the middle. What keeps her work interesting is how she filters her compositions through whatever aesthetic currently interests her—video games, Middle-Eastern dance, chinoiserie, and so on. Each new release refracts Al Qadiri’s vision in new shades, finding unexpected consonances between her prickly, minor-key melodies and the instruments or palette she adopts.

In this sense, Medieval Femme might be her best marriage of style and method to date. Her clipped toplines, here played on synthesised lutes, reeds and harpsichords, are set against shrill, reverberating synth washes and deep, rumbling pads. On tracks like “Vanity” and the self-titled opener, the effect is as haunting as Qadiri intends it to be, suggesting at once an ornate Persian palace and a ’70s sci-fi soundtrack. Not everything succeeds to the same degree. “Sheba” feels for the most part like an Asiatisch track that somehow took seven years to make its way here. A number of tracks toward the album’s conclusion feel similarly sketch-like. They aren’t unpleasant, but they feel like, with some swapped-out soft-synths, they could appear on any of Qadiri’s releases to date—a disappointment after the particularly strong opening suite.

[7]

Sunik Kim: This is a lovely turn for Al Qadiri—the synthetic, futuristic medieval lutes and pipe organs that criss-cross Medieval Femme sound like natural extensions to the MIDI-fied steel drums and digital choir patches that characterize much of her earlier work. The music is indeed dreamlike in the stereotypical sense, stripped down to spectral counterpoint, wisps of sound reflected in a still lake. Al Qadiri’s spiraling vocals further enhance this effect: their patient repetition mimics that dream-state feeling of constantly moving forward yet arriving at the same place. The barebones, suspended quality of her new sound does initially sounds like a clean break with deconstructed-club clichés, but as the album progresses, the ghosts of these tropes become audible; there is undeniably a flattened, movie trailer-esque quality to this music—disembodied IMAX-ed Blade Runner synth burps, merciless slathering of reverb—that ultimately diminishes its initial, intriguing promise.

[5]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Medieval Femme’s conceptual gambit is Fatima Al Qadiri’s strongest yet: the garden, as used in the Arabian poetry she takes inspiration from, reveled in juxtapositions. In Wine, Women, & Death, Raymond P. Scheindlin notes that in these spaces, “the boundary between inanimate objects and living beings is deliciously vague”—apt given the ambiguity and polysemic phrases found in ghazal poetry. Poetesses utilized the medium to assert autonomy and challenge gender roles, and Wallada bint al-Mustakfi—who refused to wear a veil—went so far as to embroider couplets on her robe: on the left side was text proclaiming her sovereignty over romantic affairs, on the right was a declaration of her Allah-given noble status.

This mixture of public and private, of human and spiritual, of the natural and man-made, offers a strong foundation for the traditional-cum-MIDI approach of Medieval Femme. At its best, the album offers up a space much like the symbolic garden itself: a mystical locale within the everyday where everything seems possible. On the title track, reverb-soaked instrumentation flows in dramatic fashion, and the mood is at once mysterious and forlorn and sensual. Much like the rest of the album, it strategically opts for a muted, stately atmosphere, making the listening experience quietly reverential—when multitudes of emotions arise, it feels both surprisingly and expectedly grand. But most of Medieval Femme doesn’t ever reach such kaleidoscopic heights. Oftentimes, the music has a 1:1 sound-to-signifier match—Al Qadiri’s soundtrack work should feel different from this, but that’s rarely the case—resulting in sounds that are too contemporary or too dark or too obvious. I want more uncertainty-as-infinitude, I want the legitimately enigmatic.

[4]

Gil Sansón: This record frustrates me a bit. When I like it, I really like it, and when I don’t, I think to myself, “Are you kidding me?” Part of my response is due to my personal aversion to MIDI instruments, which comprises the bulk of the sound here. I even think that this MIDI mindset, at least the way it is now, is designed within the frame of the equal temperament system that’s unique to Western culture. Arab scales, by their very nature, are often in conflict with equal temperament, and this reflects in every aspect of sound, from intonation to phrasing. It’s like the technology being used undermines the strengths of Arabic music, but I run the risk of overstepping my boundaries and am willing to admit that I may be missing the point.

Still, there’s much to enjoy here. I’ve been a sucker for Arabic music since I was a kid, so the simple notion of pop-inflected music made of Arabic scales is always an enticing proposition to me, and even in this shiny, streamlined MIDI universe I find tasty nuggets: a tangy key change when you don’t expect one, the possibility of dream pop that sounds Arabic despite the sheen (“Sheba”), but it’s only near the middle of the album that we get a track that truly sounds like the XXI century (“Golden”), with the album up to that point feeling a bit tentative—few tracks sound more like soundtrack bits than proper album tracks (“Stolen Kiss From a Succubus” most definitely doesn't deliver on the promise of the title). However, standout tracks like “Malaak”—minimal, spellbinding, beautifully stoned—save the album from being pretentious.

[6]

Samuel McLemore: The concept of Fatima Al Qadiri’s newest release is certainly good enough to base an album around: Utilizing modern digital instruments to accompany ancient poetic traditions, and, rather than reveling in the fidelity provided by modern technology, emphasizing the artificiality of the arrangements through their production—creating a meeting point where tradition and technology can merge together. Though the chain of logic that leads to this concept feels solid, the end result unfortunately is just an album that sounds like it was made with preset MIDI instruments and some reverb added in post. This isn’t really much different than Al Qadiri’s previous albums, all of which used artificial instrumentation to comment or play with a single guiding concept in some sort of camp or kitsch manner. And, as with all of Al Qadiri’s albums to date, the concept is presented as literal and as straightforward as possible, turning what should be a jumping off point for further exploration into the entirety of the work.

Despite all of the (completely accurate and fair, imo) criticisms I just laid out, Medieval Femme is actually not that bad to listen to—because of the simplicity of the execution and the referentiality of the concept, it’s a comforting album to listen to (the similarities to the best Dungeon Synth are notable here). It’s a pleasant album to put on and zone out to, but I’m not quite sure that’s what the artist intended to accomplish.

[4]

Vincent Jenewein: Reverb is cool. It usually (always) makes things sound better. Which is why anyone in their right mind tends to add more, rather than less. However, it is also highly addictive and easily abused. And in a modern production environment, there are virtually unlimited amounts of it on tap, making it very easy to overdose. When such uncontrolled reverb use spirals out of control, it can cause serious sonic harm to even otherwise decent records. Our patient at hand, Medieval Femme, is a textbook example for a terminal case of the disease known as “cathedral-reverberitis.”

Throughout the record, the majority of sounds come drenched in downright ludicrous amounts of Taj Mahal-sized reverb. This failing of measure would, in itself, not be as big of a problem if it was at least overdoing an interesting big reverb sound. But Fatima Al Qadiri goes straight for that YouTube Strymon-pedal demo sound, rather than any kind of unique reverberant signature. The reverbs’ room sizes are gigantically bland, failing to conjure any kind of memorable virtual sonic space. Their textures are overly smooth and lack grit. Their tails are generally loooong and dynamically static, at times their endless array of washy, noisy harmonics even starts to genuinely tire out my ears.

Also prominent are copious amounts of “shimmer” reverbÿthat upwards pitch-shifted, glimmery, crystalline sound that Brian Eno famously pioneered on Apollo. It’s a sound that is instantly recognizable, more or less always sounds the same, and has been abused on so many records in recent years that it might as well be 21st century ambient’s version of that ’80s gated snare reverb.

I will admit that trashing a record solely for its reverb usage is nerdy and possibly petty, but I am a reverb nerd and it is hard to ignore when the reverb is often almost as loud as the music. For better or worse, this is the kind of music that stands and falls by its reverb programming, and here, it resembles generic, toothless laptop-ambient more often than not. Some of the medieval-sounding instrumentation, for example on “Zandaq,” certainly is more memorable than that, but the cheap-sounding reverb drenching ends up giving it a canned Kontakt-library vibe that undermines the intended mysterious, mythical feel. I struggle to sit through ten tracks that all sound like they’re set in a gigantic reverberant outer-space bathtub. What is happening here is neat at times, I really just wish it was happening somewhere else.

[3]

Ashley Bardhan: Medieval times were long ago enough and filled with swords enough to exist in modern consciousness as life at its most delectably unreal. Some romantic things that might come to mind if you’ve ever attended a ren faire or watched Braveheart: flowers braided into thick twirls of hair, wicker baskets heavy with something from-the-earth and sumptuous, like figs, peaches, or quince, and Mel Gibson shirtless. Fatima Al Qadiri’s twisting knife of an album Medieval Femme enjoys slicing itself into these images (minus Mel Gibson), breathing waifish melodies made up of synth lutes and organs soaked in reverb, dripping with themselves like sweating chocolate.

Al Qadiri’s vocals are kept to brief, repeated phrases; she soothes you to sleep on “Qasmuna (Dreaming)” and entices you with sin’s “celestial sparkle” in the coquettish and fiendish “Vanity.” Medival Femme, despite the briefly off-putting 808 in “Sheba,” is successful in cloaking you in imagined history, a dreamed-up place where all you have to worry about is the endives in your garden, silk slipping off your shoulder, whether the hot succubus you saw drinking from your wine cup was real or imagined. It’s real if you want it to be.

[7]

Shy Thompson: A couple of weeks ago, someone in a Discord server I’m in dropped a medieval-styled cover of Lil Nas X’s “Montero (Call Me by Your Name)” in a music channel. I laughed pretty hard about it on my first listen, but found myself slamming the replay button immediately. There’s something compelling about the re-contextualizing of a pop song with a sonic signature that feels like it belongs hundreds of years in the past. It sounds enough like the familiar song you know, but now your mind is running wild with imagery that makes it a little fun to think about—how would the average serf react to the notion of a musician descending to face the angel of death and snapping his neck? I went down the rabbit hole of bardcore shortly after hearing it, and sure enough, there are hundreds of re-tooled pop songs in this style. “Why does this go so hard?” is a common refrain in the comments when someone is surprised that something intended as a joke ends up being oddly compelling to them. There’s something to this marriage of aural oil and water that feels right.

I’ve enjoyed early-music styled things prior to learning about this internet-driven subgenre, but now my perception of these sounds is permanently altered. Fatima Al Qadiri’s Medieval Femme comes in the wake of this revelation, and you’re probably expecting me to say that it hurt my ability to give it a serious chance—but it ends up benefiting in the end. An album like this lives or dies on how effectively it can pull you into the narrative it’s trying to build, and I don’t think this would normally succeed for me; I find the distant past uninteresting due to how nebulously it can feel connected to what I’m currently experiencing. Exploring the sounds of the past as a function of a present trend is a lot more interesting, and something the silly bard music gave me a better framework for appreciating. The lead single “Malaak” stands out: it has an incredible gravity, shrouding you with its reverberating vocals like a weighted blanket while the lute suggests something gentler just beyond the void. It doesn’t whisk me away to the Islamic garden of Al Qadiri’s imagination, but it makes me think about what these worlds might mean to her, and why she chose to set them on a collision course. At the very least, it’s fun to think about.

[5]

Maxie Younger: I don’t remember many gardens. The one I come back to most often is a photoshoot set my mother took me to when I was a kindergartner. I posed on a stepladder next to a bed of artificial flowers and a Styrofoam birdbath that I picked loose white beads off of between camera flashes. My mother paid forty dollars to print five proofs, one of which hangs proudly in her bedroom, right above an old patent-leather jewelry box; the box used to house a crudely shaped ballerina figure that would spin and play a song when you wound up a lever on the side. As a child I always wondered what that ballerina must have felt like between closings and openings of the box, trapped in darkness, uncertain of when it would give its next performance. I think now about the tension of being wound up, spinning in slow circles without consent; when I wake in the morning, the lever prods, but I stay wrapped in blankets, silent.

Solitude animates just as well as it stifles. Fatima Al Qadiri suspends her garden of the mind between these two states, bright leaves trapped in amber that shudder to an unseen wind. Medieval Femme sees the direct simplicity and sparing instrumentation Al Qadiri has developed throughout her career applied to possibly its best and most harmonious use yet; her work, highly conceptual and individual, naturally lends itself to a foundational idea of loneliness, longing, the feeling of talking to oneself behind closed doors and tall hedge walls. Deep swells of synthesizer and shallow, smoky plucked strings float gently in warm pools of reverb, muddled by the patient intonations of Al Qadiri’s voice; she repeats words and phrases that lay across the ear like soft poultices, damp flowers bound loosely with gauze. The songs are transcendent when experienced as part of the seamless whole of the album; individual tracks don’t stand out so much as small moments—the patient, meditative garden soundscape that opens “Zandaq,” the muted harp arpeggios that dot the landscape of “Vanity.” Medieval Femme is a sublime feat of concept, transportive and endlessly relistenable; now, when I think of gardens, this is the picture my mind’s eye will summon first.

[8]

Average: [5.44]

Various Artists - Imaginal Soundtracking 2: The Demon (Phantom Limb, 2021)

Press Release info: Phantom Limb continues its soundtrack series Imaginal Soundtracking, in which contemporary musicians are invited to re-score existing film pieces, with five new scores to a 1972 stop-motion work by Japanese master puppeteer Kihachiro Kawamoto.

Designed to reframe overlooked or forgotten works of cinema and to offer a new artistic challenge to the contributing musicians, Imaginal Soundtracking acts as a dialogue between the creative minds at play. The second release in the series sees a quintet of highly inventive, wildly varying takes on Japanese stop-motion animation 鬼 [eng: The Demon], created in 1972 by Kihachiro Kawamoto. The film is based on ancient Japanese mythology, telling the story of a demon-possessed mother hiding her true identity from her sons.

Created from traditional bunraku puppetry, painstakingly shot with manual stop-motion, Kawamoto’s film is beautifully expressive. It conjures sorrow, superstition, horror and honour, all uniquely materialised within a delicate and ornate miniature world. Two brothers - hunters - go out into the woods to trap deer, but find a terrifying, demonic presence haunting the darkness. With a macabre sense of humour, the piece ends with a retelling of the legend on scrolling title cards - when people grow old they turn into demons who will devour their own children: “how horrible.”

Purchase Imaginal Soundtracking 2: The Demon at Bandcamp.

Samuel McLemore: When tasked with a prompt like “re-score an existing film piece,” the first obvious issue facing the musician is how faithful and reactive they should be to the events happening onscreen. This is also the most obvious difference between listening to Imaginal Soundtracking 2 as an album and watching newly-scored versions of the same film. It’s hard to tell the difference with just audio, but when paired with The Demon, a short film by Kihachirō Kawamoto, it becomes obvious and unignorable when and how much each musician tried to sync their work to the film.

Midori Hirano and Ami Dang take the more classical approach, closely hewing to the moods and rhythms Kawamoto laid out in the original film. They are both excellently evocative tracks that sound even better when paired with the film. Tori Kudo’s track, wisely saved for the finale, is the most surprising and avant composition of them all: a meandering domestic collage that barely seems connected to anything at all, occasionally snapping into place (that vacuum cleaner!) with a precision that belies the previous impression of disorganized naivete. Sabiwa and Foodman, whose contributions are not as shocking as Kudo’s nor as satisfyingly crafted as Hirano’s or Dang’s, wind up as the odd ones out. Neither piece gels with the film, more so in comparison to their peers than for any fault of their own.

[6]

Mark Cutler: I’ll start out by saying that I did not listen to the album as presented, i.e. as a series of audio files to be heard in sequence. Rather, I just watched Kihachirō Kawamoto’s The Demon five times back to back, with each of the scores. Consequently, I’ll abstain from scoring the album as I normally would, and say instead that I found the whole experience very enjoyable and interesting.

The first two tracks are the most conventionally-conceived scores, and consequently the most illuminating to listen to in conjunction with the film itself. Ami Dang processes traditional Japanese instruments through a battery of effects, to cast a psychedelic warp over the events of the film, whereas Midori Hirano’s waterlogged piano arrangements combine with the film’s starry imagery to produce a sense of cosmic melancholy. Each score completely transforms the mood of Kawamoto’s film, without altering a single frame of its contents. By contrast, Sabiwa’s digital shrapnel and raspy, tortured vocalisations work best when Kawamoto’s imagery is at its most horrific, but the score fails to connect to the artfully orchestrated hunting scenes in the film’s middle.

Tori Kudo’s score seems to be an unedited live take, in which an older woman—presumably his wife—is talking and laughing about something I can’t make out. Otherwise, we hear the faint hum of machinery and occasional swell of crickets, until a piano swoops in around the three-minute mark. Although this highly cerebral piece strains the concept of a ‘score,’ I quite liked the juxtaposition of mundane, domestic sounds from around Kudo’s house, with the stylised, gothic setting of the story. Foodman’s score is the second-most radical departure from the original, after Kudo’s, and for me is the least successful of the five. It consists of what sound like scattered Casio ‘drum’ sound effects, which take half the film’s seven-minute runtime to coalesce into something like a melody. The way he eventually uses these MIDI chirps and clangs to approximate traditional music is interesting, but far too distracting from the actual events of the film.

My main takeaway from watching The Demon five times, with five different scores, was a renewed sense of just how vulnerable a filmmaker’s vision is to the hands of their collaborators. What other films might have been masterpieces or misfires based on a different choice of composer—or art director, or cinematographer, or editor? In this sense, even Foodman’s version was instructive, as it made me reflect on what other films I might have liked more if I hadn’t been distracted by a mismatched score. What I mean to say is: it’s all very perplexing, this matter of music in experimental film. I really wish someone would write a book to clear it up, perhaps to be published by Repeater in 2023. Until then, I hope Phantom Limb continues with this intriguing series.

[N/A]

Sunik Kim: This is a simple but inspiring concept that places the under-examined relationship between sound and visual under a microscope, painstakingly displaying the near-infinite range of effects that can result from their mutual interaction. Here, the music acts as a filter, selectively drawing out and highlighting different elements contained within the unchanging visual—from the comical and quirky to the mysterious and melancholy. The admittedly obvious but profound truth that this fascinating experiment uncovers centers on context: this visual will always be the same, but it will also never be the same—the immediate conditions in which it is being experienced are always shifting.

While the concept is extremely compelling—I’m curious to see this pushed to an extreme, e.g. with different soundtracks over a single still image—the music is still trapped within the constraints of the stereotypical soundtrack. Somehow there is this ever-present fear of sound and image crowding each other out; the stereotypical soundtrack is too respectful of the image, afraid of encroaching upon it or overloading the viewer. This flaw is registered in most of these contributions, which have their compelling moments (the intro of Sabiwa’s track, with its guttural vocalizations and filtered synth scythes) and their lulls (Foodman’s track feels half-baked and out of place), but are all ultimately somewhat forgettable in their tip-toeing.