Tone Glow 058: Daniel Lentz

An interview with Daniel Lentz + our writers panel on Duncan Harrison's 'Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos' & Susumu Yokota/246's 'Classic & Unreleased Parts One & Two'

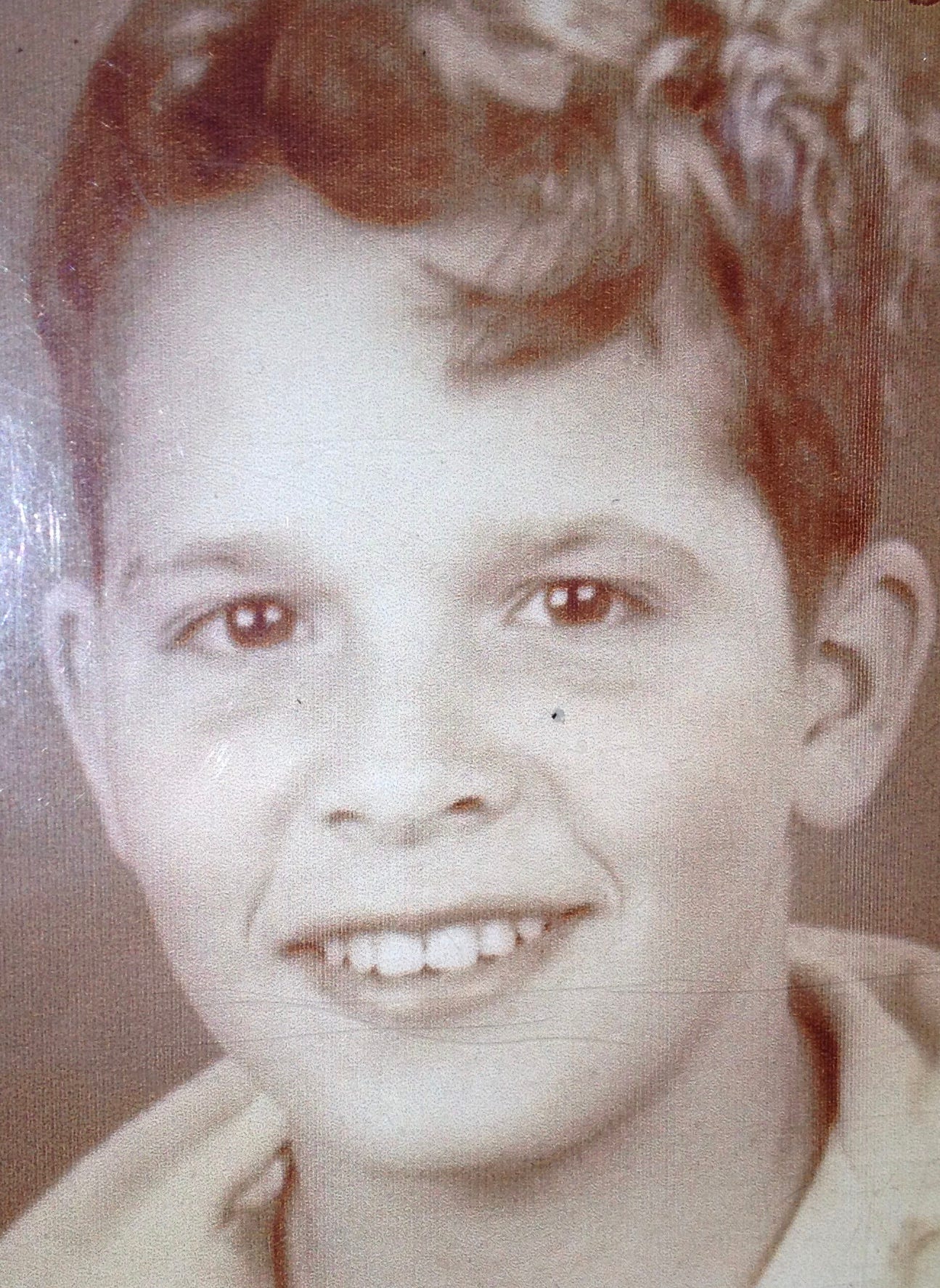

Daniel Lentz

Daniel Lentz is an American composer born in Pennsylvania and currently based in California. In the ’70s, he formed the groups California Time Machine and San Andreas Fault. In the mid-80s he would start releasing studio albums, of which Missa Umbrarum is his best known. He would continue to collaborate with numerous artists throughout his career, including Harold Budd and Ruben Garcia. His most recent album, In a Word, is a collaboration with vocalist Ian William Craig. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Daniel Lentz on October 23rd, 2020 to discuss his childhood, his “best friend ever” Harold Budd, his latest album, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello, is this Daniel?

Daniel Lentz: Yes, Joshua?

Yes, this is Joshua. How are you?

I'm pretty good. How are you?

I’m pretty good. I had a busy day and a busy week, but I’m here. I’m ready for the weekend. How are you? Did you have a good day?

Yeah, it sounds pretty much like yours was.

What were you up to?

I’m dealing with a group in Australia now about a tour but who knows when that’ll happen… it might be 2021 or the 2022 season. And the 17-hour time difference doesn’t help me much (laughter). But you know, that’s normal stuff.

Where are you currently based?

In Santa Barbara.

I assumed so. How do you like it?

I hate it.

Why do you hate it?

Well, I’ll put it this way. 99% of the people here are in the upper one percent. So as a socialist I don’t feel very welcome, but my family lives here, so I moved back a number of years ago. As soon as this virus is over I’m gonna move.

Do have your eyes on somewhere in terms of where you want to live?

Porto, Portugal if it’s out of the country. If it’s in the country, New Mexico—I really like Albuquerque. I don’t like Santa Fe, but I like Albuquerque.

What about Albuquerque speaks to you. What do you like about it?

To compare it to Santa Fe is like comparing L.A. to San Francisco. I always lean towards L.A. I like the vibrancy of it.

I know you were born in Pennsylvania.

Yeah, southwestern.

Can you describe for me what it was like where you grew up? What sort of place was it? I saw that you were in Latrobe, is that right?

Oh, that’s the closest town. I was like 15 miles from there and 15 miles from Ligonier. It’s right on the Appalachians. The closest village was Baggaley, which is like a coal mining strip, like two strips of houses. So I grew up a country boy for sure. My dad was a lumber man and all my uncles were farmers. And that has gone into my music, especially lately; I’ve been doing a lot of bluegrass stuff—and this is how I like to put it—as seen through the ears of Salvador Dalí.

What do you mean by that? What’s the connection between Dalí and the bluegrass you’re doing?

Well, I’m doing a set of four pieces for string orchestra and number three that I just finished was a real down kind of bluegrass thing. When you use strings and they have to read the music using classical string players, I have to notate it in such a way that the way they play is the way bluegrass players do it naturally. It’s mostly a bowing thing. So if you have a bluegrass tune it’s normally in sixteenths (starts humming a melody) and I put those things in phase with the different strings, so that with every sixteenth note, you might have the first violin and then the third violin and the fifth violin are one sixteenth behind.

What’s the name of the piece?

I don’t know yet. The working title… what was it… “Hillbilly Blues” or something. I used to hear bluegrass a lot especially as a kid, and then I started hearing jazz and then I let the bluegrass influence go until recently (laughs). I’m tracking back.

Were your parents and uncles big into music? Were you surrounded by music as a child?

Well, sort of. My mother was an amateur pianist, so we always had a piano. My dad claimed to play the saxophone. I can’t quite give him credit for that (laughter). But he was a music lover, he loved jazz. I get the classical, the jazz, the bluegrass all from him. And then I went to a Catholic college and that’s another influence, you know, with the Gregorian chant and things like that.

To stay with these early experiences of when you were a child, do you remember when you were first really enamored with music, with the possibility of music?

That’s tough. I don’t even remember learning to read music, it just seemed to happen. In those days, I went to a two-room schoolhouse for my first six grades. But for some reason, every student there had music every day, so that’s possibly where I learned to read music. That sort of thing doesn’t exist anymore. I also formed a polka band in the fourth grade or something like that. We did polkas and got on the Pittsburgh radio stations—there’s a big Polish community in Pittsburgh.

Before that my dad bought me a trumpet, but he started buying me Louis Armstrong sheets of music, you know, so I would read out Louis Armstrong’s improvisations, which are not simple, but I would learn to play them and sound like a 10-year-old Louis Armstrong I guess (laughter).

Was was the trumpet the first instrument that you felt a kinship with or was that the piano?

The piano was like a necessity because it was always there but I loved the trumpet. Maybe because it was louder and it got more attention (laughs). I got very good at it. And then I think it was in college, I was so used to playing and practicing for many hours a day that I developed a cold sore on my upper lip and I kept practicing which was stupid, and then it got infected. And then I lost the top octave of my range.

How old were you that happened?

I was probably 17. I was already starting to write music then.

You mentioned earlier that when you were at college, you were influenced by the Gregorian chant. Can you speak to how that works its way into your music?

It was a small Catholic college, Saint Vincent College. I would say half the teachers were monks or priests and the other half were from Pittsburgh, from the Pittsburgh Symphony and the Pittsburgh Opera. You had to be in a chant choir so you had to learn to read neumatic medieval notation. I had great teachers. While it’s happening you don’t realize it but it’s constantly infiltrating in your head and it has cropped up later in my life. With Missa Umbrarum and some masses… even though I’m an atheist, I love the form. Well, I’m not an atheist, I’m an agnostic.

You said you had some great teachers. Was there anyone in particular you liked?

Oh, yes. He was a priest and his name was Rembert Weakland. He was my theory, composition, and chant teacher. His expertise was Ambrosian chant. It was very much like a Gregorian chant—if he heard me say that he’d slap me in the hands (laughter). He became the Abbot Primate at a very young age—he was in his 30s—which means he was the bishop of the whole continent of Africa. He was in line to be, maybe, the first American pope. It didn’t work out.

The pope at that time took power was that real conservative Polish pope while Rembert was very liberal, so he never got in line to do all that stuff. He was a fantastic musician and spoke seven languages, and I’m still working on English (laughter). I would say he was my most influential, my best teacher in all my years.

Do you recall any specific lesson or thing that he taught you that you feel changed the way in which you approached or thought about music?

No, it was just kind of the rules, which I probably needed. The rules of counterpoint and harmony and all that. At least for me, he gave me free rein so I would go to the music library and find records of Stockhausen and people I got to know later in life, like John Cage and Luciano Berio. I did that on my own and of course I started to write like that in college and it was fine with him and he even baptized me. Both my parents were atheist, I can’t even say they were agnostic, but I was marrying a Catholic girl so I had to be Catholic. He also did the wedding and he wrote some of the music for it and I did too and we had a High Mass. He got outed by an assistant [for sexual abuse] when he was the Archbishop of Milwaukee. He might still be alive. He’d be in his 90s.

Are you still married to the same person?

No, no. She died in 2013, so 7 years ago. But we had been divorced—I married twice after that. We stayed friends though.

What was it like making music for your wedding?

Well, we had to deal with what we had, which was mostly organ. How can I say this… I can’t write idiomatically for it. I just wrote it like a keyboard piece and he played it. I think I wrote the processional and he wrote the recessional and in between he did the actual ceremony. My colleague band—a little jazz quartet—played the music for the reception.

We used to do concerts occasionally in this wonderful space in Milwaukee on the shore. There was this art museum that was new then and he would show up—he came to a couple of those. And that was the last time I saw him. That would have been in the late ’80s, early ’90s.

I know that right after Brandeis University you were in Stockholm.

Yeah, I had a Fulbright.

What was it like in Stockholm? What was your experience there?

I went there because there were two electronic music studios in the world outside of the US, and the only one in the US—a classical studio—was at Brandeis, which Alvin Lucier ran. And so I was going to go to Italy and study with Berio but I found out he was coming—guess where—to Brandeis! And so I ended up going to Stockholm and I hardly ever went to the electronic music studio there (laughter).

What sort of defines your time for you in Stockholm? Like you could maybe share an accomplishment.

I didn’t do any performances in Stockholm until the mid-70s—I came through there on a tour. I never attached to it musically and by the time I got there, I was losing interest in electronic music and getting more interested in what I called conceptual music. Electronic music was already getting old in my too-young of a head. Stockholm’s beautiful and has beautiful people, but I lasted a year. It’s not a place I’d want to live in again.

Why not?

Well, the six months of darkness. When I lived there, I had never been west of Chicago, so I came to Santa Barbara. Originally, I had job offers from the University of Hawaii and the University of California, Santa Barbara. So I took the one in Santa Barbara, which lasted two years. I had never been in a climate like that. I lived in Pennsylvania, Boston and Stockholm, so I was struck by the spaces more than anything in California, especially this part along the coast.

The first night I was here I landed in LAX, rented a car and came along the Interstate 5. I took the Interstate 5 to Ventura and that was the first time I’d ever actually seen the Pacific. I could see the Channel Islands straight ahead, which are like 50 miles away. And I look back and I see the mountaintops and they’re like 50 miles away. I went to a restaurant in Santa Barbara that night and it was the first time in my life I could sit in a restaurant and see everybody else in the place. It was wide open. Where I grew up—Boston and Pennsylvania—they’re all booths. You see the people you’re having dinner with. That’s one thing I’d have trouble with if I ever had to go back to Europe, or Northern Europe or anywhere like that.

I wanted to ask about your relationship with Alvin Lucier. Can you talk to me about him?

Well, he directed the studio and he would get people there, like Luciano Berio and John Cage. People like them would come to the studio to work and I learned there just by watching him and doing my thing. I think he’s a genius. I haven’t seen him in so many years but I used to do his brainwave piece and I performed that twice—it’s very hard to do. He didn’t have a musical influence on me as much as an intellectual one.

What do you mean by that?

When I was at Santa Barbara—the university—for those two years. Somehow I got into the position to get Alvin a month-long residency here in music. But the music department wouldn’t accept him so the powers that be made it a science appointment. I forget which science department it was but he was there because of his brainwave piece and the pieces where he works with speech. He was into vocoders at the time too. I was hanging with him and his friends like Bob Ashley. I got to know them and talk with them—that’s the intellectual part. I never actually performed with any of them, except maybe Cage once a long time ago.

You said that Alvin was a genius—is there a thing he did that made you really feel that way?

His whole repertoire. Music on a Long Thin Wire and his most famous piece, I Am Sitting in a Room, is a masterpiece. It’s that he takes his own shortcomings of stuttering and makes a beautiful piece of it. I find that true of a lot of artists and musicians—the ones who capitalize on their weaknesses are the strongest ones. You don’t have to be deaf like Beethoven but knowing your weaknesses really help. I would give an example or two but I won’t because they’re still alive, including myself (laughter). Stravinsky supposedly had a problem with hearing and pitch, so his comeback to that was to write something like The Rite of Spring, you know, which is in different keys a lot of the time simultaneously. He was like, “Well listen to that,” to his listener. “You don’t have good ears either!” (laughter).

Are you comfortable with sharing what you feel your shortcomings are and how you deal with that in your art?

God, I need to make a long list for my shortcomings (laughter). I can be honest about it. I’m self-diagnosing, and it’s probably a touch way too late in life, but I maybe have a touch of ADD. And I see that sometimes in my music and my inability to stay on one thing for very long. I did recognize that, or at least intuitively made that “one of my things,” I feel like. When you listen way back, like with On the Leopard Altar, you may hear a harmonic change on every beat. And my contemporaries were having one harmonic change in the whole piece. But if you do it a certain way, it becomes “one thing”—it creates its own field. That’s just one example. I’m not a great pianist, and I think that’s kind of helped me in a way, because otherwise I’d have been a pianist my whole life and I’d have written terrible piano music (laughter).

It’s interesting you mention On the Leopard Altar because even on the title track, you put six individual songs together for that. Do you mind speaking about how you made that piece? And on that note, I remember in the liner notes you mention that you’re interested in a musical “state of becoming.” Can you talk about that as well?

Yeah, that would be a good piece to emphasize that. I’m trying to remember the text for that. I wrote a full text out and then I broke it down into six different parts that all worked alone and together, at least phonetically. Any one of them could be its own little piece but Jessica [Lowe], the singer, we didn’t have much electronic keyboards like there are now. We had a Yamaha CP-30 and another synthesizer—it wasn’t a Moog and it wasn’t a Buchla—that we used to get harp-like and vibraphone-like sounds.

Each song has its own little keyboard lick in the instrumentation. She sings song one and then she sings song two, and then there’s an interlude that’s a few seconds long, and then one and two sound together, and then she does a third song and maybe song two and song three sound together, and eventually she does the sixth one and you have everything. That’s what I mean—I don’t blow the wad right away. I introduce things one at a time so you’re in a state of becoming.

I did tape delay pieces in the ’70s, which is the same principle regarding layering and time. We got into live multitrack recordings, so I’d take the studio into the concert hall and lay your multitrack and do it all in real time. That was really challenging because one mistake and you’re screwed. But yeah, that’s what I think I meant by “state of becoming.”

How important to you is one’s experience of time feeling different—of one’s experience of time shifting or feeling slower or faster—when listening to a piece of music?

That’s a good question but it’s not an easy one. Musical time is a special kind of thing and the only way to hold it together is, what I call the glue of music, repetition. In every age and every era, musicians and composers have a way of repeating themselves—there’s early rounds, fugues, sonata form, twelve tone, and so forth. I’ve always been interested in finding a new way to repeat myself, and that’s still a challenge and I’m still working on it. That’s the first thing I consider.

I did a piece recently—and this is why I’m dealing with Australia now—that’s called I Am Nature and it’s a homage to Jackson Pollock, especially his drip paintings. I’m sure you’ve seen videos of him doing his drip painting. He layers it and it’s not what it looks like—throwing and dripping is very brilliantly worked out. He emphasizes making a painting in time, as you would a piece of music. So the way I write music, it’s me adding one layer at a time until you have the full picture.

That piece is for solo piano and I used Ableton Live Suite. There’s this brilliant young pianist in Brooklyn, and it’s remarkable because he also made the software patches for it, and there’s 273 little figures that he has to play and they can appear at any time exactly as he played them. There’s no tapes, nothing like that. He sent me a recording and it’s incredible. His technique and his ability to create the patch… I think it’s what a contemporary keyboard player has to be able to do, though of course most of them play Chopin and all that, but I mean the other kind of pianist. But yeah, it’s an interesting study in repetition.

It would seem that your desire to repeat yourself would ostensibly be at odds with your proclivity to not stay on one thing for very long. What’s the throughline there?

That’s a great question. That’s why I imagined this piece. When I wrote 273 different little pieces, they could be 1 or 2 seconds long or 15 seconds long. Any of those pieces—whether they’re a bar long or, I think the longest is 8 or 12 bars—can come back in any combination at any time. The first note you hear can come back 20 minutes later, which is about the length of that particular piece, which Andrew Drannon played. I heard another person play it and it was 24 minutes, so it all depends on tempo. It’s about musical memory. And when you hear it, you might not even know that’s what’s happening. In a really good performance, it wouldn’t be that obvious, though if you’re seeing the player it would sound like there’s 12 of them. I really like that technology because it feels so clean. I’ve used it and I’d use it again. I went from that to a string orchestra, just all acoustics.

In the ’70s you recorded a piece called Song(s) of the Sirens and it was performed by a trio named after Domenico Montagnana.

Yeah, they commissioned the piece in I think 1973, which was before you were even an idea in your parents’ minds (laughter). It was recorded in 1975 and released on ABC Records, and it was a quadraphonic record, which was very unusual.

Do you remember anything about composing that piece?

I had a weird combination where it was a cello, piano, and clarinet. I kept the clarinet out until the end, and for the lyrics I combined different things, but the source was Ulysses, [the eleventh episode] “The Sirens.” “Listen to the sound of my lips”—the cellist whispers things like that. That’s a long time ago, that was my first ever record.

That was a trio and then you yourself had a trio with Harold Budd and Wolfgang Stoerchle. And then you ended up working with Harold Budd multiple times as the years went on.

Yeah, that group was called Budd, Lentz, & Stoerchle. We just did a Midwestern tour and a few shows in California and that was it—we didn’t stay too long together. I met Harold before I met Wolfgang by about a year and put that little group together and they agreed to it. Harold took a job at CalArts and then Wolfgang took one there too.

Can you talk about Harold Budd for me? What was it like collaborating with him? How do you feel like you’d grown with him throughout the years?

He’s my best friend ever, so I can’t say anything bad about him except that I don’t like his music or him. (pauses). I’m kidding (laughter).

I was about to say (laughter).

I’ll tell you what happened. I had met him at a concert in a big mansion in the rich part of Montecito, California. I did a piece called Canon and Fugle, which means Law and Order. There was a trio I made, which was part of my California Time Machine group, and there was a cellist, myself on keyboard, and a baritone singer named Fred McFadden. We wanted to do a preview because we were gonna take it to Europe, and this would’ve been 1971.

I invited Harold and a couple other guys I knew at CalArts—Gene Bowen, Ingram Marshall, Lucky Mosko—and they came and what was interesting about it was that we played the piece and we had the reception but the only person who stayed was Harold Budd, which I think is because he was the only one who liked the music. At that point they were used to that twelve tone crap, serial music. It was dominant even at CalArts—Mel Powell was there and all these other people. An exception was Ingram, who was moving away from that at the time. I don’t think Jim Tenney had gotten to CalArts yet, but he changed things a lot. But with Harold, we started going to gigs together with Wolfgang. He’s probably going to come up this weekend. He’s still hanging in.

What’s something that you feel you learned from him? And this could be with music or with life in general. Just something you feel you never would have learned if you hadn’t been his friend.

That’s a great question. Where life happens for musicians is in the recording studio. And recording with Harold on a few occasions, we did Music For 3 Pianos together and Walk Into My Voice, and some other things. He was the first person I had seen use the studio as an instrument, as its own soloist. I learned a hell of a lot from that—not that I’ve been able to apply it successfully. Also, how to improvise. I don’t know if I learned anything about that from him but I assimilated the simplicity of it.

When we did 3 Pianos, we only had one piano so we’d play one at a time. Each time, a different one of us would start something and that would be recorded and the other one would then sit down and play something against it or with it. Ruben had a little problem with that because that was new to him so we had to help him. But the simplicity of Harold’s playing attracted me, you know what I mean? I needed that. I always need that. I have to hold myself back.

You’ve had a lot of albums from throughout your career. I’m wondering if there were any where you felt like you held yourself back, and the result was phenomenal because of that specific restriction.

Wow, you’re good. It’s always the next album (laughter). Let me see (thinks). Probably Apologetica because I still like a lot of those pieces. And they’re simple. The piece “Totoka” is so simple. It’s just a couple words. “Totoka” means “Rest in Peace”, it’s a Hopi requiem word. I used to hang out at the Hopi Reservation a lot—I had a lot of Hopi friends. So of course that gets in there. Let’s see… I still like On The Leopard Altar and The Crack In The Bell, although there’s nothing simple about that.

Can you talk about your time spent with Hopi at the Hopi Reservation?

I was friends with Thomas Banyacya. He was the spiritual chief of the Hopi, and when I met him, he had just talked with the United Nations and that was a big deal back then in the 70s. I got to know him through a friend of mine who was a friend and supporter. Because she was so wealthy and liberal, she gave to a lot of causes and one of them was the Hopi Nation. After a while I’d go there myself and stay at Thomas’s house in Old Oraibi. I think he identified with me because I have a bit of Indian blood, which he saw. But I don’t know, I was a bad boy then and he was a saint (laughter). But sometimes that makes for a good mix.

Do you mind sharing a memory of him that’s emblematic of the relationship you two had?

Sure. I don’t know if this should be printed. (pauses). Okay, I’ll tell you. Don’t print it. [Editor’s note: We have redacted the story that Lentz has shared about himself and Banyacya]. I think you’re the only person I’ve told that to, though maybe I had mentioned it to one of my wives.

What sort of things would you two talk about when you were together?

Certainly not music or art. Politics, especially Indian politics and American politics, white American politics. He was really in tune with that stuff—he had to be. He was a very smart man.

You said you were a “bad boy” earlier, what makes you say that?

Well, I wasn’t him (laughter). He didn’t smoke. He would’ve known the real meaning of Koyaanisqatsi, you know? That was his world. I mostly listened, which is what you do. All the times I met with him were in his house. When I stayed at the Hopi Center there, it was like a hotel in the middle of Second Mesa, but he wouldn’t come there. He wouldn’t be seen there or any public place. I was a very unusual friend for him (laughter).

I have a lot of Sioux friends too. I don’t know if you know the Three Affiliated Tribes area of North Dakota. It’s where the Yellowstone meets the Missouri. I spent a lot of time up there. I had a friend who was an expert anthropologist and her expertise was that part of Native America. I would go with her and meet her. It’s hard to explain but she was informally welcomed and made a family member, and I met a lot of her… I’d hate to call them her family members. They were lovely people.

Are you Sioux?

Seneca. I think my family exaggerated that, though. My great-grandmother might have been full or half-blood, but I don’t like to play that wannabe game.

Do you think you’re the sort of person who always needs to be around other people? Who needs to work with other people?

You know, I don’t do a lot of collaborations. Yes, the first thing I did in California was form California Time Machine and then I formed The San Andreas Fault, and we did a lot of touring in Europe. When I moved to LA there was the Daniel Lentz Group. But this is not the kind of “performing with groups” where there’s a director and you do the music; I’m talking about living with these people and rehearsing with them, eating with them and partying with them. It’s a whole different thing.

There’s an intimacy there and in growing in your relationships, you collectively grow in your artistry as well.

Yeah. You work with the strength of the people you get to know. Such and such does something really well and you start to go that way for that person—you go towards their strengths. I found that especially true with Jessica, and Brad Ellis who’s a brilliant keyboard player who’s been working with me since 1982 and he was 20 years old.

What were their strengths and how did you move in their direction?

Brad is an incredible keyboard player and he’s very open-minded. When I met him he was 20 years old. I’ll share a story, and you can print this. When he was 21 we were in Holland and we happened to be in Amsterdam. For his birthday I gave him a free night in the red-light district, and I would pay up front—he could go from one to the other. When you’re one day away from 21, you have that energy I guess (laughter). But that’s how long I’ve known him, and that was 1983. Jessica had the rhythm of a percussionist, which is very unusual for a singer. I jumped all over that in my music with and for her.

Is there a piece of music you composed where you had this percussive style of singing in mind? And I guess I’m wondering how this allowed for the piece to succeed.

Well if you take a piece like The Crack In The Bell, which she solos on, I don’t know another singer in the world who could do that to be honest. That combination of rhythm and scat. To be able to read it and not improvise it. I think that’s a pretty good example. And then we collaborated on a whole big piece called Wolfmass, which we did get to tour once in Europe. And we recorded it.

You know Nicolas Slonimsky? He wrote a book on scales that every jazz musician uses, and he edited the Baker’s Dictionary of Musicians. I remember we did a preview of Wolfmass at Betty Freeman’s salon. She lived in Beverly Hills and was the subject of David Hockney’s matron paintings. After we did the whole thing there, Nicolas said, “What you just put her through was like somebody trying to do two Wagner operas for one person.” (laughter). But she could do it. Those two stand out as performers for me.

Out of all your works, I feel like the one people generally know is Missa Umbrarum. How do you feel about that album?

I just got an email from somebody who wanted the score. The title translates to Mass of Shadows. I would love to hear it with at least a 64-voice choir—we used 8 voices. That would eliminate the need for any electronics or amplification. You would have 64 voices and 32 wine glass players and it could be done live. Getting it done is another thing (laughter). I’m looking at a piece, I should send it to you. It’s from 1971 and it’s called Kissing Song.

I remember reading about that.

A half-dozen choirs have asked for it, but I send it to them and then they send it back to me. They refuse to do it. There’s a choir in Berlin and a choir in Rotterdam, and I was hired by Antioch College in Ohio to come for a semester to teach that piece to the choir. And the idea was that at the end of the semester we’d perform it. We got through about five minutes of the first rehearsal and all the girls quit.

Do you remember what inspired you to make the piece?

Maybe I was experimenting with singing into someone else’s mouth. If you both sang the same note, one of you would eventually drift off a little bit, like an eighth of a tone. I got together with about four people and we just tried it and would see what it’d sound like with four people instead of two. I double tracked it so you could hear eight people. And then I found out French kissing changes the width of the beat frequencies. I think it would’ve been a wonderful sound.

I’d love to see a group of people perform that.

You live in a big city, right? (laughter).

I’ll get it set up.

And it’ll be especially easy to do in the time of COVID, right? (laughter).

You have your new albums that you’ve been making in the past half-decade or so. How do you feel like you’ve grown throughout your career? When you look at In the Sea of Ionia, River of 1,000 Streams and Ending(s), who do you feel Daniel Lentz is today and how is that different from yourself in the ’70s or ’80s?

That’s a good question. One thing I notice when I look back is how where you live at any given time is very important. And then, have you lived there long enough to assimilate into what music is like in that place? When I moved from LA, I had a big fight with the director of the LA Phil. He controlled the whole new music scene in the city so I moved to Arizona. When I look back, the music change was drastic. I went from The Crack in the Bell to Apologetica and so things got darker and slower and simpler. I did a piece called Café Desire towards the end of my time in Arizona, which I did get recorded, though I have to find that some day. In LA, the music’s full of energy and the music sounds like what LA is. It’s upbeat and optimistic. That’s what I mean about place.

Have you been in Santa Barbara for the past decade then?

Yeah, about eight years.

How do you feel that Santa Barbara, especially with you saying that you don’t like it or the people there, has impacted these three albums I mentioned.

Well one thing is it’s close to LA. When I do music it’s always there. It’s been a long time since I did something in Santa Barbara in Mission. Harold and I did a concert here in 1974, and then we did a couple at La Casa de Maria, which is a Cathloic retreat center that got destroyed in the mud slides. But that’s it, it’s all churches or missions. There’s a Santa Barbara symphony and the Music Academy of the West but I don’t connect to that at all.

I think we should finally talk about the new album you made with Ian William Craig, In A Word. How was it collaborating with him?

In a way, he’s an old soul. An old soul with a nose ring (laughter). It was great. We lost a couple days of recordings, though—they were accidentally erased—but we had these three other days. We basically improvised. My favorite piece on it is “Joyce”.

Earlier you were talking about finding out the strengths of artists and working with that, like with Jessica and her percussive singing. What do you feel like Ian’s strengths are?

With Jessica it was different because everything was written out—this was more like collaborating with Harold. When Ian and I first sat down, I was at the piano and he was standing in front of me, and I think I played something first and it went through his system and it came back to me in that Ian Craig world and I fell for it. And then he would sing and I’d play, both things would go in and out. We had a fantastic time to be honest.

Before this, I had never heard sound come back at me in another sonic world. I would play, say, an E-flat minor chord and it would come back as an A minor chord. So then I’d play it and hear it come back differently, and I’d have to adapt differently to the next thing I had to play. I loved his voice and so that was all good. We performed together at a concert in Holland. It was a little weird, though perhaps more for Ian than for me. The audience looked like it was going straight up in the auditorium, and it was a little intimidating (laughter). I hope we can do some more.

Are there still things that you want to do before you pass away?

Hey, I can still run 10 miles and be fine (laughter). People in my family tend to die in perfect health. I have a lot of things left to do, though. I want to get out of the US. I have so many projects going. I don’t think real, real long term. I think this time we’re in now… not only is the present fucked up, but the future is pretty cloudy. I’ve never lived in a time like this, and I grew up hiding under a desk in fear of atom bombs.

I wanted to ask a question that I ask everyone. What’s something you love about yourself?

That I’m not me.

What do you mean by that?

(laughs). I’m just kidding. It just popped out of my head. What I love about myself is how I can love other people I guess, because I do. Sometimes too easily. But I haven’t turned away from people yet, that’s for sure.

You can purchase some of Daniel Lentz’s albums at Bandcamp. His collaborative album with Ian William Craig can be purchased at Bandcamp or RVNG Intl.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

Duncan Harrison - Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos (TakuRoku, 2021)

Press Release info: Brighton's Duncan Harrison presents an all new work of bizarre and beautiful junk-concrete, pieced together from unedited phone recordings and spread between two channels (left and right audio).

Like the two channels that unfurl the collection of unedited phone recordings, the sounds Duncan reveals are caught in dualities; the serious and unserious, the sad and ecstatic, the planned and unplanned; the musical and non-musical; the meaningful and meaningless. Whether twanging a guitar, walking into a rock bar, having chats with pals, rattling junk in a sink, making voice notes to himself, burping into the mic or rehearsing wrestling moves from memory, he provides a peep-holes to his inner and outer life, while never revealing a full picture. Through narrative juxtaposition, crude editorial cuts and double exposition, he plays a masked game of sleight of hand, unveiling layers of truth and untruth.

“Man is least himself when he talks in his own person” said Oscar Wilde. “Give him a mask and he will tell you the truth.”

Purchase Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos at the Cafe OTO website.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: If you listen to any of Duncan Harrison’s music, it’s clear that he’s got a keen ear for arrangement; he’ll take his pieces, which utilize voice and electronics and various odds-and-ends, and find delight with juxtapositions in texture and tone and recording quality. On “A Good Night,” the sound of broken glass being thrown onto a pile of more glass sounds like a sharp comedic bit when its placed alongside a sudden moment of silence. On “Rattles in the North,” looping whispers and field recordings coalesce in a mesmerizing ebb and flow, the confluence so effective that it captures you in a way that cut-and-paste collaging usually doesn’t due to the seams being too stark.

This is all to say that Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos feels like a major work for Harrison because it brings his strength to the forefront. Instead of being surprised by sudden moments of sonic clashes or coherence, we’re faced with a clear understanding that juxtaposition is the album’s main thrust. But in showing his hand right from the get-go, the reverse of the typical Duncan Harrison musical experience happens: there’s a questioning of how much of this was configured indeterminately, and this process of sleuthing—some of these sounds pair too perfectly and imperfectly with each other—is a charming game in and of itself. The end result is an encouragement to enjoy what’s in front of you, something I had in my play-with-nothing-but-still-have-fun childhood days but lost along the way. Harrison offers an example to us in the album’s closing: a recitation of as many wrestling moves as he can recall. You don’t need anything for that, just as much as you don’t need anything beyond your phone to create an album like this.

[7]

Gil Sansón: What the title says, pretty much. Casual conversation, voice note to self, guitar harmonics, electronic toys, snoring, street sounds, black metal vocal impersonation, club and pub ambience—all on two independent channels. At times it sounds like outtakes from the Faust Tapes, and while at first it may seem like the juxtaposition of sounds is haphazard, it becomes quickly obvious that there’s an artistic will behind the wheel and the result is more musical than what the title implies.

Unlike the work of, say, Aki Onda, I find this work to be unencumbered by the nostalgic element or the memory revisiting aspects of Onda’s cassette music, and I’m thus much more able to enjoy it as it is, without the need to attach emotional signifiers. The matter-of-fact simplicity allows for freshness; nowhere do I think “musique concrète” or “huh, clever.” I’m constantly reminded of the aim of the record as stated in its title, and it makes it all much more enjoyable than the game of find-the genre-elements-or-influences. It’s also more enjoyable than mere quotations (though I do detect seconds-long informal paeans to Iron Maiden), or documental pretensions, media criticism—it’s just a collage made of slices of life as captured by a cellphone, done by someone who knows how to keep the listener’s attention without the need for fancy concepts or ideological imperatives.

As most of the sounds here are not too different from what any person living in a large city will experience, there’s an aspect of recognizing that our city lives are predetermined—made of parts that in themselves can be quite amazing. Even the more puerile elements can’t help but add to the listening pleasure.

[8]

Vanessa Ague: Recording the sounds of every day has the potential to illuminate the simplicity of existence. It can transport us to someone else’s individual life, to places we’ve never been, to places we’ve never even dreamed of. Recorded, ambient sound captures this hidden intimacy precisely because it contains no prescribed imagery; rather, it forces us to create our own personal visuals in our minds.

Of course, some musicians may choose to provide a narrative for us to follow as the unknown sounds unfold, but that certainly isn’t Duncan Harrison’s prerogative. Instead, he allows our brains to wander to dreamland, asking us to fill in the gaps. Yet the sounds he chooses are too ambiguous to derive any tangible meaning from: chatter at a dinner table, chatter at a park, birds at a park, coughs outside or inside, scratches and squeals, train horns, street bands. Two streams of consciousness always flow at once, often creating a disjointed jumble that obfuscates visual imagery rather than encourages it. The best moments come when he strums catchy melodies on his guitar, layering them above the airy, distant chatter, or when the phrase “anarchy is upon us” appears from nowhere.

Perhaps the point of Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos is to eschew narrative in order to highlight the soundscapes that exist around us. But when I listen to music that intentionally lacks a concept, I’m still interested in searching for some reason to pick up the recording. I want Harrison’s Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos to speak to some deeper understanding of life, to create a vibe that’s so irresistible I can’t put the music away. Yet as I listen, I can’t find anything to latch onto. I’m left empty, wondering what the chaos he’s created actually looks and feels like.

[4]

Nick Zanca: Here, I am thrown by the word “unedited” in the title—not only does it suggest an assemblage more haphazard than what is heard, but also calls into question when one starts the process of the cut in the context of collage. It’s been said that the best microphones we possess are our own ears, but as smartphone solipsists with an ease of 64kps access, the edit now precedes the raw document; the choice is ours only when and where we choose to hit record, let alone what we flaneurs-turned-voyeurs choose to capture as we witness it. The dual-mono presentation of this half-hour of recordings invites a dominant-submissive roleplay between channels—burps usurp birdsong, unplugged solid-body noodling distracts us from tipsy conversation, flashes of erstwhile Top 40 float fathoms below public transit—but this approach to “contrapuntal audio” can often inundate the ear in attempts to lean in to its varied fragments. Despite no declutter, Duncan Harrison doubtless bears a sense of whimsy rare to the idiom; not nearly enough practitioners of “focused ennui” approach their own mundanities with such a straightforward sense of humor.

[6]

Mark Cutler: I almost feel like I should recuse myself from this review, since the method of combining unedited recordings made with the iPhone’s Voice Memos app was precisely how I played my first live shows in 2016 (I played as DJ Mark Cutler). Consequently, I’m wary of projecting my own understanding of and feelings toward this method onto Harrison’s piece. What are those feelings, you ask? Well, that it’s an extremely brilliant method, of course, and that anyone who employs it is probably very handsome and good at sound art.

In all seriousness, one of the great strengths of the iPhone-as-instrument is that each person will use it in a different way. Despite the self-consciously dry, conceptual method implied by the title, there are an abundance of ‘explicitly’ musical elements here—whether it’s Harrison doodling on an acoustic guitar, or snatches of song recorded on the street, or in a mall or bar. There is enough such material that it pretty consistently appears in either the left channel or the right, anchoring the fragments of poetry and dialogue, bird chirps, passing cars and other, more obscure sounds.

These are all materials Harrison has worked with before, in various capacities. It’s possible that some of these materials are sources or sketches for his speech- and sound-based works on albums like Preamble to Nihil and Others Delete God. However, where those releases excelled at paring each track down to a single idea or sound, Two Channels of Et Cetera feels designed to overwhelm, a deceptively, carefully-composed chaos. I suppose, on those terms, it succeeds, but it’s not one of my favourites from him.

[Editor’s Note: Mark’s score has been expunged from record due to his stated conflict of interest, and because editorial determined that a link to Mark’s Bandcamp is not a valid numerical score.] [Actual Editor’s Note: Mark wrote that.]

Marshall Gu: The title announces exactly what this album will be in six words. There is little appeal in the words “unedited voice memos,” so the music’s pull stems from how well Duncan Harrison is able to present them across “two channels.” I’ve heard this one-track album as intended, and then through only the left channel, and then through only the right channel, and never did it feel organized in any particular way to engage listeners, let alone to replay it after the fact.

By way of example, here’s one section that stood out to me: at the 4:48 mark in the right channel, a woman says “think so,” and there’s a brief spell of laughter. A man says “Where you trying to get to?” but immediately we’re in another room, and it’s presumably Harrison who announces “A Poem About the Triggering of Article 50” before we’ve moved on into the corner of some ballroom. In the span of these 10 seconds, the left channel features the drab sounds of what is probably a spoon scraping at the bottom of a can. And on and on this goes for another half-hour. A series of snapshots that proves what I already knew as we pass a year into pandemic and quarantine: domestic life is boring.

[1]

Samuel McLemore: One of my major pet peeves in music production is misuse of the stereo field. That strange period when stereo technology was still in its infancy and producers struggled to figure out how to split music across the stereo field produced many casualties in my estimation. I remember vividly listening to Giant Steps for the first time, choosing the stereo version because that sounded more “hi-def” to my naïve self, and being viscerally shocked that the drums were only in my left ear and the sax only in my right. It’s one of those things where I understand it’s a quirk of my own and I don’t expect others to share in my opinion, but how any person could have ever thought that was a good aesthetic choice is completely beyond my comprehension.

So, when I started Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos and realized that it would be 30+ minutes of asynchronous stereo channels I was, uh, not excited. Using only material recorded on his phone during the course of his daily life would suggest a diaristic approach to this album, an idea that is thoroughly undercut by Duncan Harrison’s intense focus on his chosen formal constraint. Using it like an aural fisheye lens, he replicates and amplifies the dislocation and separation that crippled many an album like Giant Steps. It’s not engaging the whole way through, but when it’s good it’s very good. Considering my initial biases, the fact that I liked this as much as I did is honestly impressive.

[6]

Sunik Kim: The lone string twang that opens the album immediately destabilizes: given the title—Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos—I was expecting whispered confessions, domestic minutiae. Shortly after, the human voice does begin to trickle in, but it’s warped, contorted, even disturbing (those Gollum-esque gurgles and shrieks around a minute in had me in a panic), reminiscent of Graham Lambkin’s most delightfully off-putting garble. Harrison’s piece certainly shares some surface-level features with Lambkin’s work, but there’s less of an occult mystique here—Harrison’s piece has a certain lightness, crisscrossed with interlocking scenes and narratives that flow effortlessly into one another.

The piece’s most compelling moments involve rhythmic interplay between two entirely unrelated sounds: a filtered house beat wrangles with café chatter; meandering guitar strums are accented with ambient, metallic clanks. Harrison’s final monologue is brilliant—it ties the entire piece together and gives it a cohesive thrust, pushing it beyond a mere scattered collage. Here, a seemingly random assortment of suggestive words gradually coalesces: these are wrestling moves, terms identifying the specific forms of struggle between two human entities. This is the fundamental tension that drives the piece: the fact that the memos are unedited means Harrison is simply pairing unvarnished fragments of life, letting them battle it out on the soundstage, drawing out and heightening their inherent vitality. Many artists work in similar territory, but Harrison’s piece stands out for its almost rigid structural approach, which gives his piece a tangible compositional integrity even in its meandering sprawl.

[7]

Jinhyung Kim: I first gave Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos a spin while walking around the city. The weather was finally getting warmer, and a lot of people were dressed nice—it wasn’t that warm yet, but dressing for weather on the cusp of arrival is a way of wishing it into being. Snippets of conversation and the din of traffic flowed past either side of me, mixing with the sounds coming through my headphones: meandering guitar, squeaking and rustling, guttural straining, muttered recitations, casual chatter, bits of music amidst the diegetic clutter…. What I like about the two-channel setup is that while something is going on, something else is always going on; with any abundance of stimuli, your attention constantly shifts from one thing to another, and by having parallel streams of field recordings just play out, Harrison lets the listener exercise a wandering attention that finds its own focal points, even as the spotlight drifts from left to right and vice versa. Listening to Two Channels reframed the commotion of the city as a third channel—one that, while peripheral, sometimes brought my surroundings into focus in a way I wouldn’t have experienced if I hadn’t been wearing headphones at all. Sitting here at home and listening now has me yearning to go out again, even if going out isn’t the same as it was before. An end to the pandemic seems to be in sight, but we’re certainly not there yet. I’ve had this album on pretty heavy rotation for the past few days… maybe it’s just my way of wishing the future into being.

[8]

Shy Thompson: More than a couple of times, while getting a couple of tracks deep into an album, I have been floored by its novel use of stereo separation—only to realize that, once again, I neglected to push my headphone plug all the way into the jack so that both stereo poles have made proper contact. Messing with the stereo channels in a way that makes the music sound unbalanced is an easy trick, but it really gets me good. Music functions exceptionally well as a way to block out what’s around me, but when it tricks me into engaging with what I’m trying to ignore, I find that especially compelling. When I can’t be sure which sounds are coming from inside or outside of my headphones and I’m constantly looking to see if the cat is knocking something over or a murderer has crawled through the window, I absolutely love it. Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos makes it obvious right from the outset that it’s going to get up to some audible trickery, but I still double-checked that my headphones were all the way plugged in. I was pleased to find that I wasn’t enjoying myself by accident this time.

This album makes me feel really anxious. Certain kinds of sounds drive me up the wall, and many of them make an appearance here. The belching directly into my left ear is repulsive; metal-on-metal makes my skin want to peel away from my bones; the mouth sounds make me want to take a swing at whoever’s making them. Even worse, the audio coming in from one channel seems to have no relation to the other. The singular act of listening to this album feels like trying to do two incompatible tasks—and I’m no good at multitasking. Duncan Harrison has shoved me into the cramped closet where I keep all the crap I don’t want to look at, and it’s too cramped in here to sort through it. I’m not sure what it is about subjecting myself to unpleasant things on purpose, but it’s sort of like the sensation that makes you want to pick at a healing scab even though it hurts; it’s an interesting experience because I’m the one making the choice to have it. Two Channels of Unedited Voice Memos is the junk I’ve chosen to keep around because I know I’ll regret it the moment I throw it away.

[7]

Average: [6.00]

Susumu Yokota as 246 - Classic & Unreleased Parts One & Two (Cosmic Soup, 2021)

Press Release info: 26 years after their original release, against the backdrop of the recent reevaluation of Japanese house music worldwide, this 246 Classic and Unreleased Works two part album is filled with techno and deep house tracks created by Susumu Yokota under his 246 alias.

Hideo Sakuma (manager of Technique Record Store, Japan) states, “Even if his death never happened, it is necessary for these works of his to be reissued now for the world to discover.”

This two-part album compiles the numerous tracks that Susumu Yokota produced as 246. The first release of 246 came out in 1995 via Sublime Records’ sub-label, Reel Musiq for the label’s inaugural joint release, along with Flare (Ken Ishii’s alias) track, “Nettin Pure 1” and Co-Fusion’s track, “Frontier”. The vinyl version of this record was cut by Ron Murphy (RIP), the legendary cutting and mastering engineer at National Sound Corporation in Detroit.

You can purchase Classic and Unreleased Part One & Part Two at Bandcamp.

Mark Cutler: It is difficult to overstate just how beloved Susumu Yokota’s discography is by so many different kinds of music nerds around the world. Whether you want crisp house, spaced-out techno, pianissimo ambient, scratchy lowercase, or baroque plunderphonics, there’s a Yokota album for you, and it’s probably excellent. So, naturally, any newly unearthed Yokota material is a cause for celebration. Additionally, many of these tracks come from a relatively quiet period between Acid Mt. Fuji—in my opinion, Yokota’s masterpiece—and the ambient albums of the late ’90s. What’s striking is that they don’t really sound like either. While Acid Mt. Fuji is ostensibly an album of acid techno tracks, it feels more like floating, disembodied, through several disjoint spaces simultaneously: dissonant melodies drift by, out of step and out of time with the main synth- or bass-line. Sometimes, a song seems to dissolve entirely, each element veering off in its own direction.

What makes Yokoto’s best acid and techno music so compelling on-album is also, of course, what makes it impractical for actually dancing. These tracks, by contrast, are by-the-book dance music, maintaining an unwavering pace and deploying each beat, effect, and melody with machinic precision. Yokota is broadly working within the confines of house music, incorporating some elements of garage and classic electro. The mood ranges about as much as it can within the house rubric, calling to mind a PS1 racing game at its most energetic, and an extremely trendy cocktail lounge at its least. In stark contrast to the work Yokota would make immediately after, even the most ambient-ish tracks here never dip below a steady 120.

Generally running more than six minutes long, these tracks do sometimes overstay their welcome. We feel that, having heard each element, we are simply waiting for Yokota to spin through all the permutations before permitting the track to end. Ultimately, I think there’s probably a reason Yokota didn’t put all these tracks on an album back in 1995—it’s not like the man was averse to putting out albums. Still, I’m thankful they are seeing the light of day now. They reveal another facet of one of electronic music’s most prolific, polymorphic artists.

[6]

Sunik Kim: This is an immediately lovely sound—Yokota’s clacky 909 hits and blurry acid washes tickle the ear, driving forward with a confident but understated ease. His simple two or three note basslines are Mills-esque—abbreviated, fragmented, but they don’t pound as much as bounce; there is an almost cartoonish lightness to some of these tracks, even as they veer towards the austere and minimal. The nearly-identical structural, sonic and rhythmic template of every track gives the entire release the feeling of a laboratory experiment: Yokota has established his variables from the start, and the album is simply an unfolding of their interaction, a series of studious workouts. His unflashy use of delays and studio trickery only heightens this effect—if he veered too far into fiddly sonic extremities, the tracks would lose their rhythmic and compositional cohesion.

The highlights tend to center on a single, central element—a looped, warped synth rush or the meanderings of a synthetic fretless bass—giving the music a rare focus, even as it fluidly shifts registers between different tracks and the sections within. There is a spectrum within club music: on one extreme, the sounds themselves are little more than anonymous stand-ins, conduits for the arrangement of musical events in time; on the other, the sounds themselves—their painstaking design and sculpt—are the primary focus. Yokota’s release sits solidly in the middle: there is a classic familiarity to the sounds on display, but he manages to arrange and rearrange them so effortlessly that they whizz and crackle with an undeniable freshness. In a field that is literally built on formulas and templates (not a judgment), this is an usual feat—a reminder that rhythm is an infinite substance, but one that must be carefully, exactingly embodied in order to enjoy it in its fullest splendor.

[7]

Samuel McLemore: A brief look at the history behind Susumu Yokota’s 246 alias should give everyone a few clear expectations for the music he made under it. 14 tracks recorded by Yokota entirely over the first half of 1995 and released under a simple numerical pseudonym designed to evoke Detroit's iconic 313 area code. So: an homage to Detroit techno from one of the best producers ever, circa ’95 Japan. Each track is so logically consistent in its progression and so rooted in the formal tics of classic Detroit Techno that you can almost predict its progression from just the first few bars. In most music, such predictability is a death knell for engagement or pleasure, but here it’s as enjoyably predictable as a Haydn symphony. Saying an album is 90 minutes of exactly the music you expect it to be isn’t normally considered a compliment, but, to be clear, that’s exactly this collection’s strong point. When you start dancing is when this music really starts to make sense. The predictability is now a guide, giving you leverage and space to dance with. It’s much easier to get caught into a groove when you can see it sneaking up on you.

[7]

Nick Zanca: Perhaps my present impatience for old club ephemera is to blame—our current world is deprived of dancefloors, after all, hopefully not for much longer—but I found this compilation a complete chore to sit through. The forward fluidity and the kaleidoscopic breadth of sound sources that once made Sakura and Grinning Cat ideal looking-glass contributions to the YouTube-sidebar ambient “canon” are fully absent here; in their place sit rigid Roland machinery seemingly disinterested in much else other than occasionally riding one or two faders on the Mackie mixer. This is a curatorial situation not unlike the Music From Memory-released retrospective of CD-era Japanese pop our team was recently tasked with reviewing: ultimately, an archival grasping-at-straws from the annals of a discography whose ripest fruits have already been ravaged, serving no listeners but the occasional cult completists. It takes a lot to get me to never want to hear a 909 rimshot ever again.

[1]

Maxie Younger: 246 Classic & Unreleased Parts One & Two trades in a diverse range of moods: melancholy, ebullience, comfort, solitude—feelings that sweat out on the dancefloor and bury themselves in the club’s foundation, ghosts that rise into the atmosphere in response to the heat of new bodies. Like with most releases that collect Susumu Yokota’s archives, Classic & Unreleased obscures rather than illuminates; in these efforts to bring us in closer contact with Yokota’s multidimensionality, it only becomes more apparent that his depths as an artist lay at a distance far beyond the shallow reach of archivists and would-be tastemakers.

The music itself is serviceable, if not extraordinary: as 246, Yokota seems to lack trust in his audience. The tracks are often overpaced with constant addition and subtraction of new rhythmic and melodic figures, especially in the compilation’s first half; opener “Do Up” tires itself out quickly with a tumultuous barrage of claps, kicks, hi-hats and snares encroaching to fill practically every spare sixteenth-note space before the song even reaches its first minute, dipping into brief interludes of piano and filter-swathed synthesizers that lurch unsteadily around a muted four-on-the-floor pulse.

Other songs fare better: “Ambient Love” anchors its beat around an iridescent, echoing melody played on digital bells that slips in and out of focus over a steadily throbbing bassline; “Squeeze Up”’s jaunty, swung groove surfs across waves of flanging tom hits with ease. Not much of what defines Yokota’s most enduring later-career works shows its face here, however, and if his name weren’t attached to it, I’d find it tough to give it a second thought. Classic & Unreleased is good fodder for marathon DJ sets and relaxing afternoons, but it’s no replacement for what was lost with his passing.

[6]

Gil Sansón: There’s no need to introduce Susumu Yokota to anyone remotely interested in electronic music. His influence is immense and the respect he achieved in his life was unanimous among both public and critics. There’s always been an element of house in much of his work, but this release focuses on his 246 alias, the one he used when he wanted to do house full-on. This is a functional type of music that’s made for the dancefloor; people come expecting to meet a certain criteria, a specific set of sounds. It is, thus, a genre that sees music as product and strives to make the production of said sounds as streamlined and functional as possible. Just as with music from the classical eras, one finds evidence of genius not always in melodies and harmonies, but rather in transitions or passing modulations between the strictures of the style. Similarly, Yokota’s brilliance can be found here not so much in the sounds and timbres, but in the details. Upon close inspection, we find many odd transitions, rhythmic problems set to be solved, even instances of virtuoso handling of handclaps and claves. Nothing on this compilation will sound like anything unusual in 2021, but there’s this utopian quality to house music, and Yokota was very good at it. This type of music had no secrets for him.

[7]

Average: [5.67]

Thank you for reading the fifty-eighth issue of Tone Glow. Don’t turn away from people just yet.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.