Tone Glow 053: Lane Shi Otayonii

An interview with Lane Shi Otayonii + our writers panel on Wau Wau Collectif's 'Yaral Sa Doom' & C.A.N.V.A.S.'s 'Apocope' compilation

Lane Shi Otayonii

Lane Shi Otayonii is a Chinese musician and vocalist who currently records art pop under the moniker Otay:onii, as well as creates sludgy rock music with her band Elizabeth Colour Wheel. Her newest solo album Míng Míng grapples with the titular concept, which refers to “a place between our world and the other world.” Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Lane Shi Otayonii on February 19th, 2021 to discuss her memories of boarding school, how she treats her voice as another entity, and the ideas underlining her newest album.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello!

Lane Shi Otayonii: Hello! How are you?

I’m good, how are you?

Great!

Are you in Shanghai right now?

I’m about a two-hour drive from Shanghai. I’m somewhere in rural China.

What’s it called?

It’s called Haining.

Oh, yeah—that’s where you were born!

Yeah (laughs).

What was it like growing up in Haining? Do you mind sharing a memory that you have of growing up there?

I remember picking up frogs (laughter). I kind of really regret it now because it’s a cruel action. But also, I went to boarding school when I was very young and I remember disliking it. I had trouble staying calm and I think I was pretty agitated when I couldn’t call my parents, or when they threw away my IC card.

I went to the headmaster’s office and essentially told him that if he didn’t expel me or let me out of the school—because you weren’t allowed to leave—that I would do something that would make him regret this decision his whole life (laughter). He got pretty scared so he expelled me the next week. After that I moved to Guangzhou, which is in Southern China. I don’t particularly like this area because it’s famous for furs—real furs.

What did you dislike about the boarding school? Did you just miss your family? Did you find it too restrictive?

I probably just missed my parents. My classmates, though, were fine. They were really supportive. The teachers were fine too. I think it was just too lonely for me, spiritually. I was like nine or ten.

What do you mean that it was lonely for you spiritually?

All I wanted was to contact my parents and, at the time, there was one teacher that told me that I’d get used to [not seeing them]. But I couldn’t sleep when I was young. I would sneak out and call my parents with my IC card. I remember I started to explode when a teacher said to me, “I need to borrow an IC card, could you give me yours?” So I gave it to her under the circumstances that she’d return it, but she didn’t. I realized that she was just trying to get me to calm down in this condescending way, and I was really not into it. I felt like the world was not there to help me contact my parents, that this connection was blocked. It was a mess, to say the least.

You said that you’d do something to the headmaster that he’d regret—do you know what you would’ve done? Maybe you didn’t have anything in mind—

I don’t know. I was pretty on edge at the time. I was a very dark kid and it wasn’t that I liked being dark—I just accepted it was a part of me for a long time. I probably would’ve shouted and cried and… I don’t know… it didn’t happen, so (laughter).

Do you still feel like a dark person?

No, I feel lighter now. When I was in middle school, I was very tired of things around me—my parents included, because they were always fighting. I thought that I should just leave, so I left them and went to the US, and that was great. I decided to change myself in terms of how I communicated with people. I didn’t want to be so dark or stressful, I wanted to be lighter and expand my sense of humor a little bit because, you know, I think I’m a funny person (laughter).

Was it a hard thing for you to do, to change the sort of person you were?

Yeah—it was not natural and required effort for sure. I made an effort to talk with people at school about topics they were interested in even if I wasn’t. I tried to understand others and not be so in my own world.

So you spent all this time learning about other people. I’m wondering, did you have people in your life who did the same for you?

I had some, I would say.

Do you mind sharing about one person that comes to mind?

Yeah, she was one of my best friends in high school. She was really cute. She encouraged me to sing. I started to write songs myself but they didn’t sound like happy, popular music. What’s that one song? (starts humming “I’m Yours” by Jason Mraz). We were high school kids, and those were the songs they liked. But my songs were always like, “I’m in this valley…” (laughter). People were like, “What the fuck is this kid doing here?”

My friend really accepted me. We would listen to Marilyn Manson in our dorms and we would exchange music together and that was really nice. She also drew a lot, and drew pictures of me. She’s a good painter even though she’s not a visual artist. She painted this one of me that was really dark (laughter). It was me with all my hair down. I really liked her, we were buddies.

This was in high school? And in the US?

Yeah, this was my first year in high school. It was at this place called Cushing Academy in Ashburnham, Massachusetts. I think my math teacher was an ex-FBI agent. She had this Fibonacci tattoo here (points to elbow) and I really enjoyed looking at it. She was cool.

My parents were really scared [about me being at Cushing Academy] because of my former experiences at boarding school, but I was independent and I got out of this mode of missing them too much and wanting my parents to be around. I learned to have my own life.

After all this you went to Berklee College of Music. What was that like?

After a year at Cushing, I went to another high school because I wanted to be in a band. Nobody at Cushing wanted to be in a band with me (laughter). There aren’t “rock” high schools, only classical, so I went to Walnut Hill School for the Arts, and they had writing, dancing, musical theater, classical music, and visual arts all in one school. I learned opera there, which was really helpful because I feel like my singing was really influenced by opera and classical singing and classical composition—all that kind of shit.

Berklee and another school in Minnesota were the only two schools I applied to for college, and I got into Berklee and I really didn’t like it. I remember I went to [a summer program] and I thought it was so lame that we learned how to grab a mic from one corner of the stage [and bring it] to another. That was all we learned as a performing strategy, and I was like, “You all have no talent.” (laughter).

One of the cool things, though, is that you might meet people who like the same kind of music as you. I got to know quite a few people through this band I had called Dent. It was me, another guitar player named Harley Cullen, our drummer Jack Whelan, and our bass player Tristan. We were gigging around Boston and got out of the Berklee bubble by doing that and got to know other musicians. Now I’m in a band called Elizabeth Colour Wheel. That was the biggest achievement for me.

So even more than anything from the school, it was finding these people you formed bands with?

Yeah. I did like my major because I learned stuff on the tech side of things. I did some circuit bending, which was helpful for my multimedia installation stuff. But that was it. I thought all my other classes felt like I was burning money. I would’ve dropped out of Berklee if I didn’t need a visa. At Berklee, you need a principal [instrument] to get in and for me it was my voice.

I thought Berklee was resourceful but I didn’t think they could give every student what they needed. I was specifically required to learn jazz and I wanted to learn it, but I asked to have a teacher who could understand my love for heavier music and electronic music. They gave me an almost-retired, old jazz singer and she specifically told me that she hated rock and I dropped all ideas about becoming a performance major. I went to tech immediately, and thought it was the only way to make my parents’ money worth it.

That makes a lot of sense. Speaking about singing, I wanted to ask about your voice. How do you feel when you’re using your voice and singing your songs? How do you feel about your voice?

Thank you for asking because that’s something I want to dig into more in the future. I think that classical music really set my background for singing, in terms of training, but I think my voice has a psychological component. If I’m feeling a certain way, it will show in my voice.

I used to smoke a lot, especially doing tours when everyone would be hanging out. I destroyed my voice and got nodules, and that’s when I realized that I couldn’t reach the notes that would express the feelings that I had. So I got surgery and couldn’t speak for two weeks. I got my voice back, and that’s when I quit smoking cigarettes. I mean, I still smoke like one cigarette once every two months.

That’s so little!

(laughs). Yeah. I feel like my voice is another being I need to talk to and communicate with. Every morning I drink tea and practice with my voice. And I exercise. I really try to drink water with honey and treat it like a little human. I don’t really like it but it’s the reality of trying to take care of your voice and to not abuse it.

I’m writing something where I’m trying to dig out the frequency responses to your body, especially to your organs and how that’s related to your psychological state. First of all, your throat is an instrument. Second of all, it’s a biological instrument. And third, that means a lot because you can carry your instrument with you at all times. That’s something I’m trying to write about and I want to get into this frequency span that’s very effective for your body. I met somebody who was trying frequency therapy in Colorado—the person uses frequencies to specifically tune into your organs and heal dysfunctions or diseases. It’s all still in an experimental stage but I think it’s a good experiment people should try in music outside of music therapy.

Earlier you said that the way you feel that the emotions you feel really come out of your voice. Can you provide an example of a time when you really felt that was true?

One time I was in Texas for a music festival and I was camping there with a lot of people. There was this person with a guitar who started playing and I felt really happy and started to sing. My body moved with my voice, my voice moved with my body, and suddenly everybody came out with their instruments from their tents. It was rare to see. I have never really been in a setting where people made a little group circle and sang with everybody else. I was happy. People were just saying that my voice was very alluring, and that people wanted to sing with me. If there’s anything in art that’s worth talking about, it’s that moment of connection, of joy with other people. Like, I could have a lot of joy orgasming on my own, but with another person, it’s double happiness, and it’s double magical.

Right, and that connection is so important. When you have that intimate bond, whether we’re talking about orgasming or with music, it’s always beautiful when it’s something that’s bigger than yourself.

Yeah. And there have been times where I performed with Elizabeth Colour Wheel where I felt like I reached that pinnacle of joy. And with Dent too. Interestingly enough, I had a show not so long ago in Guangzhou, in this really low-key venue called OK Center. The crowd was crazy. They were touching the walls while I was playing. I went out during the set and they were blocking me while I was trying to re-enter the room. They wanted to interact with the player, or the “happening.” That was a really cool experience for me.

What do you find meaningful about audience interactions when performing live?

You can’t hide. You can see people being uncomfortable, and that’s it—they’re uncomfortable. If they’re laughing, they’re laughing. I enjoy knowing that that’s you in that very particular moment.

You’ve mentioned how your voice is like a separate human that you take care of. But at the same time, it’s still your voice. Do you feel like in training your voice and performing, that it’s helped you in understanding your own identity?

I don’t think I’m a flawless person in terms of, like, my facial features, especially when I perform. And sometimes people take pictures of me and I’m like, “Holy fuck!” (laughter). I make peace with it in terms of, that’s me, that’s my body, and that’s my voice. That’s me in that very particular moment. It all made me realize that I’m a person who’s very nomadic—I don’t think I hold onto a particular image. I think everybody is wonderful, and I think flaws are what make everybody who they are.

We should talk about your new album, Míng Míng. Do you mind talking about the concept behind your album?

It all started when I realized, “Holy shit, I’ve been in the US for 11 years. I’m losing touch with my culture. My Chinese language is fading.” There’s some folklore or stories that I kind of knew about because they were passed down through oral tradition from my parents, but I don’t know much deeper than that, and that scared me. With my visa and stuff, I might not be able to go back to China either. I feel like I’m trapped with choosing between either side.

I made this piece of art where someone’s on the shore and there’s a person in the water who’s drowning, but there’s a red string that’s tying their hands together. I’m making an animation where there’s one person who’s gonna drown while the other person won’t get drowned physically, but will drown mentally. And they [end up being] the same person. It’s a metaphor for myself because I’m at this stage where I’m passing by my history and am losing it.

I’m more aware now of my surroundings and the things that separate myself from my history, including experiences like getting my visa at the Belgian consulate. At the time, me and my band were scheduled to tour Europe, which is cancelled now, and I recorded a lot of the songs in this moment of being alone and reading all these sagas that were happening. I read a lot of Chinese folklore and myths and about magical figures and while I enjoyed being in that world, I felt distant from it.

I was very into the metaphysical construct of one’s being. It’s important because it relates to the relationship between me and my voice—of my body and my voice. The word Míng has multiple meanings, one of them refers to the place your soul gets stored before reincarnation. That’s a stage—it’s a gap between the future and the past—where I feel like I’ll find the answer to what mythical being I was, and what that’s like in a modern setting, and in the US.

That was how I started the album, so the artwork and the music grew together simultaneously. I think I’ve spit out some harsh words in the songs, but they were necessary because I thought I was honest in expressing something. And my individual experiences might be meaningful to a larger group of people.

Out of all the songs on the album, which one do you feel provided the most transformative experience?

There were two songs that I really liked. One was “Subhuman Sings.” It was based on the intense experience of getting my visa. I was teased by my interviewer, and she was annoyed that I didn’t collect all my materials. She said something like, “You’re not European, you’re not American, you’re not Japanese, you’re Chinese, so get over it.” I started to cry in the consulate and she even asked, “Why are you crying? There are more unfortunate people in the world.” And yes, sure, but crying is the only right that I have, so let me cry. It was sad.

I went home and went to the studio and was laying down for a little bit. I stood up and felt like a zombie. I started to noodle on my Prophet and the beginning of the song came out very naturally. If I had to choose, I wish I never had to encounter that experience. If I hadn’t experienced it, the song would never have existed, and that’s fine with me. I don’t think a person should have to experience things like that to write songs.

There’s also the last song [“Un deciphered”], which is in Chinese. I recorded a lot of things in Chinese, telling myself, “Learn how to be a human before anything.” And whenever I’m feeling down, I listen to that song. That was a song where I felt like I was looking to the future. It’s almost like a capsule—the song is like a lost voice message sent out in space, where people can find it and decipher it.

The song is called “Un deciphered” which means “A deciphered ______,” and in this story that I’m constructing for the music video, there’s a person who finds a house where there’s nobody around. The resources on earth are destroyed and people are trying to find a way to survive individually. And a person finds this house and hears this song, this noise, and beside the house is e shou (讹兽), who’s the symbol of lies and all this shit that people endure that prevents them from getting to fundamental ideas and theories. I’m imagining this video where a person, through the effort of deciphering, will be able to hear this song.

Sorry you had to go through all that with your visa.

It’s alright. I’ve realized that people at the top are the ones with human rights, and they then use them to fight against people who don’t have them. China has a lot of problems, but people criticize it by saying, “Oh, China doesn’t have human rights.” But I don’t know—if we’re gonna help each other, let’s not bullshit around and let’s talk about things that’ll really help. But now, it’s easy to see who may be smart but has bad intentions.

I wanted to ask… what does it mean to be human? What does that entail?

I think the first thing is honesty. I think that’s the foundation for everything else. Honesty and authenticity. The synchronicity of body and mind. Even if you’re or you’re being dishonest, you can always have a friend who can tell you when something’s wrong, like “Hey, come back!”

If you could be reincarnated into any being, what would you wanna be?

That’s a cool question. I think I’d be a bird. I’d like to fly. I’m obsessed with the feeling of falling down, and also, I feel like the sky is so boundless. So right now, yeah, I’d like to be a bird. There are birds chirping right now outside of my window. (laughter).

I can hear them! That’s a good choice. I was wondering what other plans you had coming up.

I think I’m gonna wear my costume, which is a performing suit. I collaborated with a friend. I’m gonna walk around the shopping mall and dance with my music on. Maybe I’ll get a haircut. I’m gonna ask my sister to film me, but it might be too much for the townspeople—this is in rural china. But I’m excited for that. Also, it’s my birthday, so I have an extra excuse for all that.

Oh my god, when’s your birthday?

It’s Monday.

The album comes out on your birthday? That’s amazing!

I’m giving myself a gift! I think that’s the one time I’ll give myself one.

Well, happy birthday! I hope you enjoy it.

Thank you, Joshua.

I wanted to ask one last question and it’s one I ask everyone: What’s one thing you love about yourself?

(thinks) I can have some distance from things, even things that I’m close with. I can be involved with something but also observe it from the outside and have that perspective. A really funny thing is that I have poor eyesight—I’m blind if I take out my contact lenses. And as I get older I’m gonna get farsighted too. I feel like that’s a metaphor for how I feel with being able to tap in and tap out things—it helps me to observe myself and be honest.

Purchase Míng Míng at Bandcamp.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

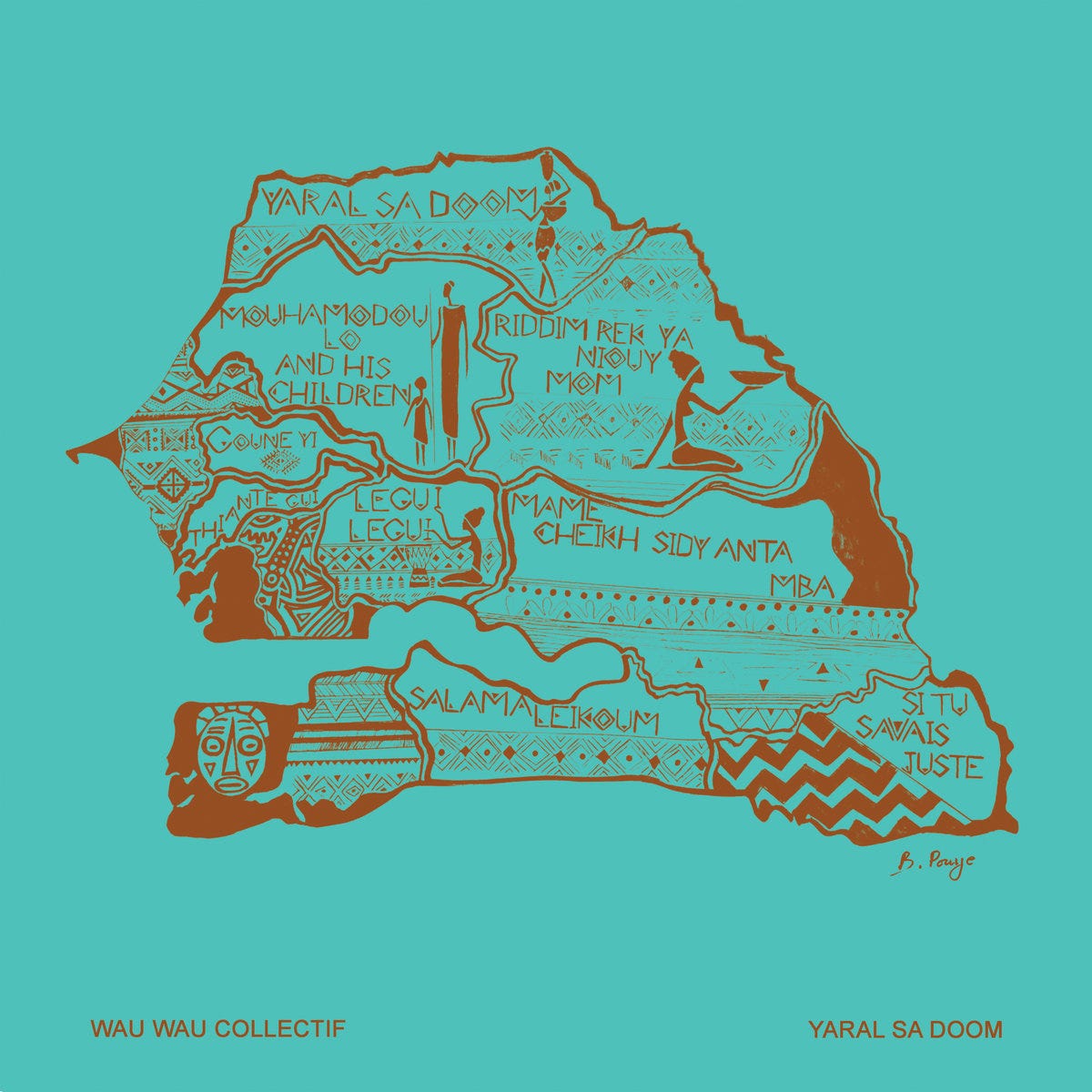

Wau Wau Collectif - Yaral Sa Doom (Sahel Sounds, 2021)

Press Release info: In 2018, Swedish music archeologist and leftfield musician Karl Jonas Winqvist traveled to Toubab Dialaw, Senegal, a small fishing village turned hub of Senegal’s bohemian art scene. Over the next weeks, local musicians, percussionists, poets, and beat makers came together, sketching out ideas and recording free improvisation. Winqvist returned to Sweden, trading recordings back and forth over WhatsApp with Senegal based collaborator and studio engineer Arouna Kane.

“Yaral Sa Doom” is a Wolof phrase that means “educate the young.” Central to the album is this theme of education, with songs that directly address social issues facing contemporary Senegal, education, and immigration. "Today you must educate children with an instrument and art, when you teach them an instrument you teach them to use their spirit," says Djiby Ly.

With over 20 contributing performers from Senegal and Sweden, the resulting album is layered and complex, yet maintains a central vision. “It’s like diving into the sea,” explains Kane. “There are all different species of fish swimming around, but together they make the ocean.” Nonetheless, it's also a geographic anomaly, made possible only by exchange of the internet age. An exceptional recording on its own, "Yaral Sa Doom" is a visionary entry in the future of transglobal collaboration.

Purchase Yaral Sa Doom at Bandcamp.

Jesse Locke: Wau Wau Collectif’s Yaral Sa Doom is an understated yet enchanting experiment in long-distance collaboration. Spotlighting a large group of Senegalese musicians recorded by Swedish producer Karl Jonas Winqvist during his trip to Toubab Dialaw, the improvised sessions were edited back and forth online until they became a lively cross-cultural jam. You can feel the communal spirit in this collection of songs with a title that translates to Educate the Young.

The album covers an impressive range of musical territory as it drifts from the dub-like pulse of the title track to the stuttering beats and soft woodwinds of “Yaral Sa Doom II.” Elsewhere, “Gouné Yi” slows the pace to a sparse, mournful lament, before the good vibes return on “Riddim Rek Sa Niouy Mom”—chicken-scratch funk guitars, hot sax, and the emergence of disco hi-hats turn this song into the album’s most infectious moment, transporting the mind’s eye to an outdoor dance party.

Yaral Sa Doom’s efforts in intergenerational inclusivity are showcased most prominently in the plainly titled “Mouhamodou Lo and His Children.” Here, the deeply resonant intonations of the lead vocalist are echoed by a plucky, youthful chorus as their voices swirl in a languid atmosphere of synth, sax, and ’50s surf guitar laying back on the beach. If you’ve ever found a smile creeping across your face listening to Bill Callahan’s droopy baritone accompanied by a children’s choir on “Hit The Ground Running,” this song will hit you in the same pleasure centers.

[8]

Marshall Gu: “Mouhamodou Lo and His Children” brings me such joy: easygoing guitar over the clomp-clomp of bass; it’s like being a part of a gathering around a campfire, nevermind that the instruments are electric. And then a male voice comes in, his speak-singing and deep voice interrupted by his children’s much brighter ones—you can picture the smile on their faces!—and the image intensifies: it’s not just friends playing and singing together as a collective on Yaral Sa Doom, but family too.

The entire album follows suit: Yaral Sa Doom is full of warm and golden tones. I can live in these sounds: the deep hum of the bass on the title track, the joyous kora lead on “Thiante”, the reflection of the Senegalese coast on the lulling “Salamaleikoum,” shimmery piano backing the wind instrument on closer “Legui Legui.” That Yaral Sa Doom was made out of recordings from local musicians from Toubab Dialaw is fairly evident from the diverse range of sound; when the electronic drum sound of “Yaral Sa Doom II” shows up, or “Riddim Rek Sa Niouy Mom” works up a sweaty groove, the album never sounds disparate. Instead, it has that communal feeling of local musicians playing their favourite songs, further collaborated by Swedish musicians and then disseminated to this Canadian boy over the Internet. This album makes me feel so, so small and happy: a reminder that there’s just so much music being made out there, just waiting for me to discover.

[8]

Sunik Kim: The fairly polished and potentially anonymous sound of the production here initially had me wary, but as the album unfolded, the tension between the shinier production and the looser, loopier, ramshackle, sketch-like nature of the tracks themselves established a compelling (and cozy!) sound in its own right. The key is “Yaral Sa Doom II”: its bouncy cookie-cutter kick-snare beat (complete with mechanistic rolls every few bars), anemic in other contexts, here functions quite differently. The beat’s flat character only accentuates the weightiness and warmth of the song's other elements—especially the vocals, whose interlocking, densely-layered quality shines through as a result.

While the album offers a consistent experience front to back, few tracks stand out quite like “Yaral Sa Doom II,” and instead mostly teeter between pleasant and forgettable. In this case, forgettable is fine, forgivable; the formula offered—dynamic vocal performances backed with cheerful instrumentals and shuffling rhythms—simply works. Plus, it’s hard to resist the music’s succinct, relaxed intimacy—which feels effortless, despite the fact that it’s the product of a complex “transglobal” collaborative process.

[6]

Mark Cutler: Traditional instruments and Wolof lyrics are bracketed by slappish bass lines on the low end, and ethereal synth washes on the high, recalling the loungier strains of trip hop. Guitars, flutes, and saxophones drift in and out inoffensively. The whole thing is pleasant enough, but it all feels worked over, smoothed out. Averaging around the three-minute mark, the songs rarely have time to develop, or even really breathe. Once you lop off the gauzy track transitions, the core of each song feels closer to 90 seconds in duration. It’s hard to imagine this is how the Senegalese contributors generally perform or present their music.

Much of what Winqvist has put out on his label leans to the twee side of experimental music—‘experimental’ in the sense that Jon Brion or The Polyphonic Spree are experimental. The album is presented as ‘spanning borders,’ as a ‘genre defying entry in outernational sound’. Yet it feels like much of what would have made this album unique has been excised, and the remaining snippets flogged into a shape that will be readily intelligible to white, European ears. It’s hard to conclude anything else from liner notes which fail to include any specific instrumentation, but make room for the frankly galling line, “Artistic Vision by Karl Jonas Winqvist.” Despite the ostensible, active participation of the Senegalese players and vocalists, I imagine this album aging about as well as Moby’s Play. I’d give the musicians a 7, but Winqvist gets a big fat 0. Let’s average, round up and say

[4]

Samuel McLemore: Though still a drop in the bucket compared to what is intended for local consumption, music from African musicians that’s have intended solely for the Western market has been around since at least the 1980s. Labels like Peter Gabriel’s Real World Records specialized in bringing both “authentic” and “progressive” examples of African music to western audiences, and the occasional star—like Youssou N’Dour or Ali Farka Toure—found real popularity there as well. In other words, even though Yaral Sa Doom’s breathless one-sheet describes it as “avant-garde” and “genre defying,” and even as “a groundbreaking album spanning borders and musical scenes,” the truth is that it doesn’t do much that hasn’t already been done before, nor does it do it better.

Sounding distinctly like loose jam sessions that got massaged into finished tracks during editing, the songs are generally unmemorable and short. When judged as a cross-cultural collaboration it falters as well—the different collaborators (over 20 in all apparently, not that you can tell) are mashed together such that none of them ever stand out as unique voices. Instead of a mixture of styles and approaches one gets a hazy soup that sounds rather similar to lots of “world music” we’ve been hearing for decades now.

[3]

Gil Sansón: Oh boy. Why is it that every time I read the word “collective” in relation to a non-US/European musical project there’s always one European or US musician running the show? Is it a natural handicap that prevents them from enjoying these sounds in their natural state? Why is it that they need a curator from a Western country? Chalk it up to Western liberalism and its guilt complex, where patronizing is done with the best intentions at heart…

But what about the music? A fishing village in Senegal that has its own music scene meets a sympathetic producer from outside. It’s implied that the producer will have smarts and state-of-the-art production techniques to make the music shine. But does it really need them? I suppose one would have to listen to the originals before this meeting to make that affirmation. Personally, I don’t see what’s gained by applying MIDI and VST pads to such music, here or anywhere else—they have a tendency to turn everything into the equivalent of a TV dinner for the ears.

Being clear, some tracks really hit the pleasure buttons for me, especially the ones that stick closely to the original spirit without studio “improvements,” but to me this isn’t far removed from Buddha Bar or those dreadful Putumayo anthologies. This is the type of project Western people use to congratulate themselves on being good citizens of the world, music for UNESCO cocktails and parties, sanitized for market consumption. When will we see the opposite—African producers and their ideas of production calling the shots and Western musicians following their lead?

[4]

Eli Schoop: It might be stereotypical to assign African art with wide swathes of ideas, but one thing I notice in the continent’s music is its genuine love and joy in making it. There’s no irony, no artifice, just a communal pride and creativity that permeates so many of the best regional genres and styles. Wau Wau Collectif’s Yaral Sa Doom continues this by showcasing Senegal’s version of this phenomenon. It’s both rooted in the local tradition, and fiercely committed to integrating non-endemic sounds to its oeuvre, using MIDI synths, dub rhythms, and samples to enrich the lush atmosphere on display.

Yaral Sa Doom means “educate the young” in Wolof, the local tongue, and it’s an apt descriptor for how formative this varied collection can be, a substantive sampler for kids interested in music and what the artform could mean to them. Not just satisfied to be targeted towards children, the song “Mouhamodou Lo and His Children” features the voices of kids just as engaged with the tune as the elder narrating over its softly rumbling guitar. Ingenuity is at the helm of Yaral Sa Doom, its heart based in the true power of music and its effect on all of us. We’re all just really big children after all.

[8]

Oskari Tuure: Yaral Sa Doom simultaneously inhabits two different realities: the album has its roots in organic folk music, but they have been augmented with the flourishes of more Western production and psychedelic influences. Because of this it's easy to see the album as both a continuation of the Senegalese music tradition, but also as an example of modern and global, continent-spanning collaborative music. Often it's hard to tell where Senegal ends and Stockholm begins.

The album is at its best on "Mouhamodou Lo and His Children", a protest song, the lyrics about uniting the workforce and shoving fists in the faces of your oppressors. But unexpectedly the production and songwriting don't have even a tinge of aggression to them. Instead, the track moves at a leisurely pace, sounding like a pleasant walk on the street of a small town on a summer day. A man and children are singing a call-and-response melody over a backing track playing from and old cassette – they walk away, but the cassette keeps playing, and a distant saxophone and gentle synthesizers lull the street into a daydream. The track segues into "Salamaleikoum", a ballad scored by a music box playing glitched-out voices of children, its text a manifesto about how the natural order of the world is to be without borders. These two tracks exemplify the album's theme of educating the kids: children's voices have a central part in the music, and the album's lyrics convey a heartfelt wish for their future to be better than the present.

[7]

Average: [6.00]

Various Artists - Apocope (C.A.N.V.A.S., 2021)

Press Release info: Apocope is the second C.A.N.V.A.S. compilation, following Cipher (2019) and featuring another grouping of dispersed artists responding to a call-out under a unifying theme/sky. Where Cipher approached codification, Apocope approaches the cut-off point of a pop operative. An ‘apocope’ is a word truncated—a sound omitted—moulded into a shape that rolls off of the tongue yet carries within it further significance.

Together as C.A.N.V.A.S; Lugh, Olan Monk and Elvin Brandhi invited Alpha Maid, Bashar Suleiman, Billy Bultheel, Hulubalang and Nadah El Shazly to join them in excavating ‘POP’—a boundless yet always personal subject, specific to context and forms of co-existence.

The resulting record created by the group is a warped hypogeum of dissonant intimacies, the texture of the post-POPped bubble strewn into unpredictable hymns of prophetic onomatopoeia. Together this collection of tracks sustains tangible reciprocity between those involved, despite the dislocation of the time during which it was made and the physical distance which separated the artists who communicated remotely.

Purchase Apocope at Bandcamp.

Gil Sansón: Not having heard the previous C.A.N.V.A.S. compilation, I was immediately intrigued by the first couple tracks. There’s an emphasis on the “post”-prefix genres on both, and they’re quite different: Alpha Maid’s “Harry wants to imagine a world without you” is angular while Bashar Suleiman’s “Safeway” is smooth and spacey while keeping a grainy, gritty texture. Elvin Brandhi’s “FRIDGE! Ez_virus” is close in spirit to the Alpha Maid track but nastier in expression, like mangled data thrown at your face. Billy Bultheel’s “The Sky Bent” is, in contract, a thing of beauty—the sound of Mark Hollis and late Talk Talk reimagined for 2021.

The differences abound: there’s Nina Hagen vibes amidst the bass-heavy rubble of Hulubalang x Elvin Brandhi’s apocalyptic gospel track “Cekik.” There’s unsettling, urban soundscapes—too formless to fit a style, too busy to be ambient—in Lugh’s “Nu,” channeling Techno Animal during their isolationist phase, while Nadah El Shazly’s “Fl3ln” features welcome Arabic scales. The record closes with Olan Monk’s “Na Madraí go Léir,” a track that more or less mixes all strands of the previous pieces into one, and its vocal delivery feels like an incantation. Compilations are rarely this cohesive and consistent, and with only eight tracks—none of which outstay their welcome—you need this one in your life.

[8]

Sunik Kim: The splintered, splitting guitar sounds in the first track had me intrigued; they disoriented—I wasn't quite sure what to expect afterwards, a somewhat rare and delightful occurrence in this little experimental corner of the world, where familiar tropes often announce themselves from the get-go. Unfortunately, the album quickly settles into tired post-Amnesia Scanner sounds—mournful, serrated synth lines; frantic gabber kicks; disembodied hoover sweeps; discordant vocal helium—that, while perhaps on the more interesting end of the ‘deconstructed’ spectrum (the extra high-pitched vocal fuckery stands out), still fall flat in their dated and formulaic approach.

There is a deep irony to the ultimate lack of invention present here. The compilation positions itself as an “excavation” of “POP,” a “burnt out landscape of post-pop memories,” and even claims to strive to “redefine the realm of the possible”; but the end result is simply a nihilistic shuffling and re-shuffling of already ‘post-[insert genre here]’ tropes, a deconstruction of a deconstruction (of a...), a dead-eyed, zombified iteration of the critical vitality present in the “excavation of pop” as exemplified by an artist like DJ Screw. If that really is the goal here, then so be it, but I have serious trouble with jaded end-of-history art that offers no actual positive project of its own.

[3]

Marshall Gu: Alpha Maid’s “Harry wants to imagine a world without you” starts the compilation off promising: arpeggiated guitar chords creating a familiar point of entry, with the song turning into some deranged madhouse halfway through. But the title is the most interesting thing about it; the sonics are abrasive to the point of annoying. I would have preferred what came next with Bashar Suleiman’s lone contribution: six minutes of scraping textures in search of a song.

The rest of Apocope is in these two modes: abrasive sonics that, if they didn’t succeed in turning me off, weren’t going to be things I’d replay (Elvin Brandhi’s “FRIDGE! Ez_virus”); or the boring, dronier stuff (Olan Monk’s “Na Madraí go Léir,” which, had it had a trap beat, could’ve been some SoundCloud C-lister’s Travis Scott impression). I couldn’t find the overarching narrative for this compilation, one the accompanying press release makes the case exists in the first place: “Apo-Cope, understood also as apocalyptic hope.” I demur: it is not hopeful to think of the end of days as something as joyless as the songs in this compilation.

[4]

Maxie Younger: I’m thrown for several loops by Apocope every time I listen to it; I’m undecided on whether or not this is a good thing. I enjoy being taken off guard by music, but befuddlement is a difficult state to stew in for upwards of thirty minutes. While the compilation’s deconstructionist riffing on pop signifiers is undoubtedly a compelling idea on paper, in practice it leads to a wildly uneven mix of cheeky sample interpolations (track one, Alpha Maid’s “Harry wants to imagine a world without you,” pulls from the Hip Hop Harry dance circle breakdown), vacant soundscape noodling, and flat, wet stabs of industrial noise.

There isn’t a single unifying element that shines through consistently across these tracks; pop is so uniquely elastic as a genre—a blank canvas on which to project any number of sensibilities, emotional landscapes, or deeply personal memories—that it’s hard to imagine any two people would end up interpreting it in a similar way. As such, the songs on Apocope collide awkwardly in a disjointed puddle of aesthetics that zigzags between diverse inspirations from artists based in Britain, Ireland, Jordan, and Egypt, among others. I’d be much more interested in seeing just one of the featured contributors’ takes on the brief in an extended, EP- or LP-length format.

The wide variation is, of course, kind of the point of a compilation like this, but I don’t think that it works to the benefit of the tracks themselves. There are standouts from the bricolage regardless: closer “Na Madraí go Léir” from Olan Monk is a gorgeously dark, gothy descent into oblivion by way of a blown-out drum machine and ominous, detuned guitar riffs that sway over Monk’s brooding voice like ticking pendulums. When I think about Apocope, I picture the fumbles of the earliest eras of paleontology: mutant skeletons cobbled together from the fossils of dozens of different animals, joints upon joints interlocking, feet for wings, tibias where fibulas should be and vice versa; it’s a dazzling flourish of creativity, but the parts aren’t creating the right whole.

[5]

Samuel McLemore: The first three tracks here, before the vocals begin to seep in, are more to my taste than the back half. The best of it reminds me of the impossible-to-name and difficult-to-define underground electronica I grew up listening to in the late 2000s. Whether it got called floorcore, pedalcore, or just “drone”, it felt like a new and exciting sound, and it’s a little odd, and a little sobering, to see a whole new wave of artists approach this sound again over a decade later. About time! It’s a sound that’s long been ripe for reinvention.

The press release is a soup of mind-numbing gobbledygook but it appears to state an intention to use the concept of the apocope as an organizing principle to make fractured pop music. I think I also like the first three tracks better because, unlike the latter half of the comp, the musicians seem to take this idea seriously and stopped themselves just short of making pop songs. The artists in the back half (who I realized just now are also the instigators of this compilation and the originators of the apocope concept, hmm) are far more messy and unorganized. Unfortunately I don’t think pop music becomes avant-garde when it’s played as sloppy as possible, it just becomes sloppy pop music.

[4]

Evan Welsh: The concept of “apocope” in relation to pop is risky for a couple of reasons. The first is assumed pretention: the use of an obscure linguistics term as a foundation for a study on pop music is a certain I-retweet-Deleuze-memes level of insufferable—I am one of these people—that can initially be off-putting. The second is that if the idea of “apocope” is to be translated into music, there is the possibility of coming away with songs that never quite get to where they’re going, and leave the impression that they were just never finished as opposed to being interrupted or suspended to fit an aesthetic purpose.

On the opening track, “Harry wants to imagine a world without you,” Alpha Maid layers dissonant samples of guitars, drums, and a music-box into a rickety carnival entryway. Without time to develop, the song really only acts as an intro, which is disappointing given how invitingly askew it is. The next few songs are given the most time and space to exist as entireties unto themselves. The dense ambiance of “Safeway” by Bashar Suleiman succeeds by the nature of it being a longer piece, allowing the environment to settle. “The Sky Bent,” achieves the sensation of melancholic tranquility that is constantly threatened and fragile. Then, the jolting electronics and vocals on “FRIDGE! Ez_virus” comes to re-infuse some of the chaotic noise gestured to by the opening track. The first half of Apocope works by giving us at least mostly complete thoughts, but like the concept itself, the album gets cut off, and never quite reaches what sounds like a final form.

On the way to its conclusion, three of the final four songs—“Fl3ln” being the exception—might as well be marked as drafts. “Cekik” builds a sense of claustrophobia slowly as the song progresses but loses out on any sort of affective manifestation of hysteria with the brief runtime. The glitchy-beats in “Nu” never pierce through the foggy atmosphere of the synths, so while they add some texture, the whole thing ends up feeling like an interlude. Closer “Na Madraí go Léir” remains in the same dull register the entire time—it doesn’t disappoint as much as bores. In all fairness, the album does embody apocope, it just does so in a manner that creates more frustration about unfinished experiments and unfulfilled potential than it does inspire serious interrogation or interaction with the concept.

[5]

Mark Cutler: The C.A.N.V.A.S. collaborative intend these tracks as a kind of referendum on pop, “approach[ing] without reaching their referent.” Yet very little here feels linked to any era or variety of pop music from the last several decades. More often, the music recalls the early, so-bad-it’s-good club music of the infamous JANUS parties, throwing tuneless synth squiggles and rhythmless beats together, and seeing what comes out.

Billy Bultheel’s “The Sky Bent” veers between snatches of slow singing, string arrangements, and blasts of speaker-rattling, Alec Empire-esque synth beats. Actually, it makes me think of 16bit’s production on Björk’s “Mutual Core”—which was already criticized for sounding dated in 2011, but which I always kind of liked. Elvin Brandhi’s “FRIDGE! Ez_virus” is a squall of chipmunk vocals and abrasive whines, sounding very much like an Amnesia Scanner offcut. We feel the whole thing trying way, way too hard to be interesting, well before the last few seconds, when a pitch-shifted voice starts shouting what sounds like “AIDS AIDS AIDS AIDS AIDS AIDS AIDS.”

“Cekik” is one of the more successful tracks here, and, being the only direct collaboration, perhaps makes the best argument for C.A.N.V.A.S.’s vision of collective creativity. Brandhi and Hulubalang pair shouty, almost-crunkcore vocals with a deluge of bassy drones, suggesting a missed opportunity for ’00s acts like brokeNCYDE. Lugh’s “Nu” is similarly interesting, sounding like a nervous percussion section approaching and retreating from a choir of vuvuzelas.

These tracks, however, do little to elevate a listening experience which often feels like a slog through well-worn experimental music tropes. It is typical for label comps to sound disjointed—part of the intent is to showcase each individual artist’s unique point of view—yet Apocope somehow feels both incoherent and samey, distinctive neither in its subject matter nor its variety of approaches.

[5]

Eli Schoop: First, the good. Elvin Brandhi’s “FRIDGE! Ez_virus” is rather arresting, voice modulated noise that over-stimulates and provokes confusion, something that’s always fun for experimental music. And Olan Monk’s “Na Madraí go Léir” is a cool piece of dank Gaelic pop—his unemotional singing reminiscent of Dean Blunt but with the instrumental core of Type O Negative seeping through the walls. This concludes the good.

The bad: If you put out a 472 word press release that reads like a revolutionary manifesto, your music better rival the best pharmaceuticals. This compilation is touted as a call to arms and a “defiant and hopeful gesture, striving to redefine the realm of the possible.” There’s like five tracks on here that are just wailing guitar feedback mixed with voice synthesizers. It’s like a National Review contributor’s idea of avant-garde music: pure self-indulgent nonsense with delusional ambitions of grandeur. Both “Harry wants to imagine a world without you” and “Safeway” are examples of this; completely low-effort creations that fail to justify any of the lofty claims given in the album’s liner notes. I personally hate the word “pretentious,” but I have never seen its usage more justified than for Apocope, a wet fucking fart disguised as elevated idealism.

[1]

Average: [4.38]

Thank you for reading the fifty-third issue of Tone Glow. Be honest with yourself.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.