Tone Glow 051: Suzanne Ciani

An interview with Suzanne Ciani + our writers panel on George Lewis's 'The Recombinant Trilogy' and Xïola Yin's 'Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak)'

Suzanne Ciani

Suzanne is a composer and electronic music pioneer who has released dozens of albums including Seven Waves, The Velocity of Love, and LIVE Quadraphonic, which restarted her Buchla modular performances. Her work has been featured in films, games, and countless commercials. She released multiple albums last year, including A Sonic Womb: Live Buchla Performance at Lapsus and Improvisation on Four Sequences at Festival Antigel. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Suzanne Ciani via phone on October 8th, 2020 to discuss the difference between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, her latest albums, Don Buchla, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello!

Suzanne Ciani: Hi Joshua!

Hi Suzanne, sorry about earlier! I apologize. [Editor’s note: Kim accidentally called Ciani for the interview 30 minutes prior to the scheduled timed].

Oh no, it’s fine! No problem. It’s funny—the neighbors were doing power cleaning until a couple minutes ago, so it’s good timing. It was very noisy. Where are you?

I’m a little outside Chicago.

How’s Chicago right now?

The weather’s great right now. I was just outside, actually (laughs). I went for a walk after I called you since I had some time to kill. It’s in the mid/upper 60s right now, it’s a little windy, but it’s sunny. I like this weather.

They do say that Chicago is the windy city!

They do!

I guess it’s true! (laughter). My niece is in Michigan—she’s in Ann Arbor. She went there because the air was bad here [in California]. She teaches there so she goes back and forth, and she says that we’ll all be living in Michigan before this is over because with global warming it’ll be the only nice place.

Oh, what does she teach? I’m a teacher as well.

She teaches research in the school of nursing at the university there. Her training is in psychology but she kind of went from psychology into diet because she saw how impactful diet was on the psychology of happiness. So now she’s doing groundbreaking research in diet, especially in diabetes.

That’s exciting!

It is exciting! It seems so obvious that people shouldn’t be eating carbohydrates if they have diabetes (laughter). But anyway, what do you teach?

I’m a high school teacher. I teach science. You know, prior to becoming a teacher I was heavily considering becoming either a dentist or a nurse—with the latter, I was volunteering in the pediatric department of a hospital when I was in college and loved my experience there. I ended up going for dentistry, but after being in a program for a little bit, I dropped out because I couldn’t see myself doing it for a living.

Yeah, it’s a calling. It’s not just an idea, right? Once you realize that making a living is all-encompassing of your life, you have to choose wisely. I think it’s wonderful that you’re teaching in high school—the kids are so amazing at that age.

I love it. It really is an incredible profession. I love that age group because with high schoolers, my goal is to foster an environment where they can learn who they are and what they can do. I want them to grow but I also want them to feel comfortable relying on each other. It’s fun.

And science, of course, is at the top of the list right now (laughter).

Yes! So, I wanted to start off by asking you: You were born in Indiana and grew up in Quincy, Massachusetts, which is right next to the Atlantic Ocean. Do you mind sharing an early memory you have of spending time in or around the ocean? Do you have memories of that from when you were a child?

Absolutely. When I was very young, I had chronic earaches. They were painful and sometimes kept me up at night. The main thing was that when I went to the water, I had to wear a bathing cap. One of my most poignant memories was being in the water and taking off the bathing cap and hearing the sound—the sparkly sound of the water. This was kind of a life-changing moment that implanted on me the beauty of that sound, just that abstract water sound. I’ve always been… it’s not a secret that I have a deep connection to the ocean (laughter).

It is not a secret! (laughter).

I don’t know exactly where that comes from, but it is definitely a leitmotif or a theme in my life. And now I live in the ocean, directly on it. I sleep with the sound of the ocean.

Were your parents and your siblings also into these things—visiting the beach or swimming or the sounds of the ocean?

Well, you’d have to ask them (laughter). We rented a house in Cape Cod in the summer. Oh, hold on, I’ve got this cat here (picks up cat). This 20 pound cat! If it sees me relaxing, it figures it’s time for it to get attention.

That’s what cats do! What’s your cat’s name?

This one’s name is Mouse. And then I have another one named Minnie.

I love it!

Minnie and mouse (laughter). You take things for granted when you’re growing up. You don’t know anything else; you only know what you know. Everything always goes into the background. I wasn’t even conscious that I was living on the ocean—it was the norm. I’m sure it had an impact but it was all on an unconscious level.

I’ve only really spent time on the Pacific Ocean. Do you feel like there’s a noticeable difference between the Atlantic and the Pacific?

Absolutely! Maybe because I grew up on the Atlantic, but I miss it so much. First of all, it smells different. When you’re on the seaside on the East Coast, it’s more redolent… you can smell the fish and the clams. The air is different; it’s like the smell of autumn, and you don’t get that on the West Coast. The West Coast is an expansive version of the East Coast, even if you just look at a map it’s all scrunched up on the East and that spreads out as it goes west. The Pacific is grandiose, it’s got big waves and big beaches.

I miss the East Coast. It’s like a Proustian experience. If I could smell it—if I could get just one little whiff of that—I’d be transported back to the East. Sometimes I think I smell it.

Is scent a big thing for you in addition to sound?

Well, I guess so (laughter). In the COVID times now, a good friend of mine lost his sense of smell. And this happens—it’s one of the defining features of COVID. It must be a terrible thing because that olfactory system is our primitive connection to a primal identity and essence. It’s a very direct connection to a deep part of our primitive brain. So, yeah, smell is important. I miss all the smells of the East Coast. I might have to go back but no one is traveling now.

Hopefully you get a chance to do that soon.

Thank you, I’d like to, too.

Do you mind sharing something about your parents? What kind of people were they and how did they impact your life?

I had a big family—there were six kids. My father was of Italian descent; his father came over from Italy and was a physician. My mother was of Germanic heritage and came from Iowa, so they were kind of opposites. My mother has the distinction that she is the only person that I’ve ever known who has never complained. She never, ever complained, but I complain all day! “It’s too hot!” “it’s too cold!” “Why doesn’t this work!” (laughter). My mother never complained. Just take that in—it’s huge! She had patience and quietness and steadiness. She was the most placid and brilliant person.

She also had an amazing sense of humor. Her side of the family is funny, but I never knew that side until I lived in California. My dad’s side of the family was very dominant because he was an Italian patriarch—larger than life—just big and boisterous and in charge. And the poor guy had five daughters—that wasn’t easy.

You started playing piano when you were younger—what drew you to it when you were a child?

Well, we had a piano in the house. I think that’s important. I’m always encouraging people with children to have a piano in the house because the child can gravitate to it. It’s a very private thing to have that connection to the piano. We had a lovely Steinway piano and my mother got it—she always bought everything at fire sales. My two older sisters were taking lessons and I heard the piano and I wanted to learn.

I actually taught myself to read because it is logical. If you know where middle C is on the piano and on the piece of paper, it’s just a graphic system from then on; you go up one note on the piano and then one note on the paper! It’s just all very clear and I figured it all out. I loved reading music—there was no limit to what I could explore. It’s like with kids reading books and when they discover that they can have access to any number of stories and experiences—that was it for me with music. I could explore.

Do you remember what sort of composers you liked playing when you were younger?

Romantic. Brahms. That’s where I started out. I fell in love with Chopin—he’s very pianistic. And then I fell in love with Bach. Bach had everything.

Do you play piano at all nowadays?

I don’t at all. I had a tennis accident and my left hand… it’s painful for me to play the piano. Maybe I can get further care for that but right now I’m not playing.

Ah, I see. You said that reading music was a very logical thing… do you see yourself as being a very logical person? Do you see the act of composing as a very methodical and logical thing?

You can’t compose without logic. It depends on the medium. I’ve composed in traditional media where everything is written out and orchestrated. I’ve done things that are improvised. And I’ve done things in electronics where you’re working more as a sculptor—the language is different. But you still have the training, and all that comes to bear in anything you do because you can change approaches but you still are who you are. Does that make sense?

It does, it makes a lot of sense. I wanted to ask—what initially interested you in attending UC Berkeley?

I had a fellowship. They paid me to go there, and that’s why I went. I didn’t know UC Berkeley. I had a choice to go to Paris and study with Nadia Boulanger like other composers did, but that would’ve cost money. To go to Berkeley I could be completely financially independent from my family.

I know you’ve talked about this a lot, with wanting to quit the piano to play the Buchla. During these initial years of playing the Buchla, did you just never even have the thought of playing the piano then?

That is correct.

What about the Buchla has made you want to stick with it?

I call it developing a relationship with the instrument, and that expands and deepens the more time you spend with it. And the more time you do spend with it, it’s more rewarding. And it’s technology so it’s changing all the time; it’s not a static thing. That newness, that continuous evolutionary aspect of the machine is very engaging—there’s always something new!

When I think of the time that I spent just on mastering certain technological things… if I had spent all those hours playing the piano I would’ve been a concert pianist. But I didn’t! To be really good at the piano—or anything—takes a lot of time. But I always thought of those as “lost hours” in technology. For the piano, you’re doing the same thing—you’re building a technique, you’re building on familiar territory, and you can feel it accreting. Whereas with technology, you’re never any place—you never get to first base (laughter). It’s always something new! I mean it!

Even to this day, now that I’m back in it, it’s like oh my god—I have to learn this and that and it’s ongoing. It’s a continual process of learning. I just got a new audio interface—I had to, because I had to get a new computer. Now I’m in [macOS] Catalina and my old audio interface didn’t work so you’re forced to move and to change. And then you have to embrace that thing and it’s unfamiliar. I guess that keeps your brain alive, when you’re dealing with unfamiliar territory to some degree.

Do you feel closer with the Buchla than with any actual person you’ve had a relationship with?

I wouldn’t compare. They’re all relationships, but I wouldn’t compare human relationships with that.

That’s fair and makes a lot of sense. Do you mind sharing any memories of Don Buchla that are emblematic of the sort of person he was?

Buchla changed over the years. When I first met him, he was very difficult. He was in his own world, he had no social graces, he wasn’t communicative. And then as he went on in life, he became much more, I would say, humanized. Maybe he was less of an introvert or… well, he was famous for being very abrupt and a man of almost no words at all.

I reconnected with him when I moved back here in 1992 and we became friends. I loved his wife—that was his third wife—and I always credited his wives with humanizing him. He had wives, he had children, he had a life! He has an amazing sense of humor that comes out in his performances. His performances were always charming and offbeat, so he runs deep. He’s just a simple genius.

Regarding what you said about Don having wives and children… do you think it’s necessary for artists to have a life outside of their music and art?

You have to have a life outside of all that. Music in the abstract… I’ve always appreciated the emotional dimension of music, so I’ve never been a fan of pure abstract systems to organize composition, but you have to have something to say.

What do you feel like you’ve been trying to say through your music? And maybe that’s changed throughout the years, but what’s the message you want to relay to those listening to your works?

Before I came back to the Buchla, my message was about emotion, safety, beauty, passion. Now that I’m back to the Buchla, my message is about the experience of interacting with the machine. It’s about the playfulness. The compositional approach to electronics is very immediate. You’re sculpting in the moment. You have to set up the opportunities to be able to play. You have to define the playfield, but once you get it all together you can just play within that.

How do you feel like you’ve grown as a musician throughout these years? When you see yourself from when you played the Buchla, then went back to the piano, and now that you’re back at the Buchla again, where do you feel like you’ve grown the most? And this can be growth as a musician or as a person.

I think it’s just a long evolutionary path. One thing leads to another—it’s a flow. I’ve always gone with the flow and that’s why I’ve always surprised myself. And I know now that I don’t know what’s next. Whenever I’ve made these total statements, I’ve been proved wrong. “I’ll never go back to the piano!” “I’ll never go back to the Buchla!” (laughter). It doesn’t matter what I say, because something’s gonna happen and I’m not gonna know what it is.

Is there anything you want to make sure you accomplish? As you’re getting older, I’m wondering if you’re thinking about things you want to make sure you do before you eventually pass away.

One of the things that I have to say now is really about that dance with the machine. That dance that I did 40 years ago is coming back now. The consciousness of analog performance without a traditional keyboard—that’s what I always wanted to happen. And it didn’t happen, and it can’t happen. There’s no definition of what that looks like really because this field is highly personal and nonspecific because there are thousands of modules now. There’s no there there. It’s not like a piano with 88 keys and 3 pedals.

I say it’s a collaborative field. Because of the technology, the tools are made by the toolmakers. And then they’re used by people like myself who explore those tools and create things with them—unexpected things. It comes to life in that duality. A toolmaker but they don’t know what you’re gonna do with it.

So anyways, what I’m trying to impact now is the tools. I want people to be aware of that collaboration. It’s a back-and-forth and it’s a very complex thing because everyone has their ideas. I try to take a step back and think of the big picture and think of what’s important to do. We need more spatial control, and my thing is live performance. Electronic music is huge and there are so many aspects to it. I’ve participated in a lot of those. I’ve done studio albums and non-Buchla works and now I’m back on the Buchla, and I’m now all about live performance. Am I so great at that? You know, I have the tool that I have now. So when I was doing this 40 years ago it was a different tool. That was the [Buchla] 200. Now I have the 200e. It’s different and I cannot do what I did then. But it’s all interesting.

You have two albums of live performances that were released recently, the one at Lapsus and the one in Geneva. What’s your favorite thing about performing live?

All of these are improvisations on the same basic, raw material. They have certain identities that are the same. I start with the ocean and then I go into different sections. And they’re different because nothing’s ever the same when you perform live. I think I do good performances and bad performances—or, let’s say I do performances that I like more than others. When that quadraphonic LP was put out, I thought, “Oh my god, this is my very first live Buchla concert,” and I didn’t like it! But now I love it.

What changed that made you like it?

I had such challenges with the tools. I wasn’t able to do a lot of things. I didn’t like the filters. I was just so confronted with all the things that I missed with the 200 and in the end I just performed it, and when I listen to it now, I appreciate it for what it is and not what it isn’t.

I want to be mindful of your time because I know there was a hard time you wanted to end this by.

Yes. Do you have anything else?

This is a question I always like asking people: Do you mind sharing something you love about yourself?

Something that I love about myself… let me think about that. (pauses and thinks). Well, what I love about myself is that I can listen to and trust what I call my little voice. So, I’m aware that I have within me a very good friend who takes care of me (softly laughs) and keeps me on course. That little voice… I love that I have that and I’ve grown over the years to be respectful of it. In the old days I could tamp it down—“Why am I thinking that?”—and then ignore it. But whenever it speaks now, I listen. It could be something simple, like “Don’t do this, the house will burn down” (laughter).

Thanks for sharing that, I’m happy you’re listening to it more and more.

Yeah. I’m sure we all have something like that.

Thanks so much for talking, I hope you have a great rest of your day.

Thank you Joshua, it’s been very sweet speaking with you. Take care.

You can purchase A Sonic Womb at Bandcamp. Other albums can also be found on her main Bandcamp page.

Writers Panel

Every issue, Tone Glow has a panel of writers share brief thoughts on an album and assign it a score between 0 and 10. This section of the website is inspired by The Singles Jukebox.

George Lewis - The Recombinant Trilogy (New Focus Recordings, 2021)

Press Release info: Pioneering composer George Lewis releases "The Recombinant Trilogy," an album consisting of three works for solo instrument and electronics that use interactive digital delays, spatialization and timbre transformation to transform the acoustic sounds of the instrument into multiple digitally created sonic personalities that follow diverse yet intersecting spatial trajectories. Featuring virtuosic soloists flutist Claire Chase, cellist Seth Parker Woods, and bassoonist Dana Jessen, doppelgängers are created that blur the boundaries between original and copy, while shrouding their origin in processes of repetition.

Purchase The Recombinant Trilogy at Bandcamp and the New Focus Recordings website.

Nick Zanca: Let’s address two elephants in the room: the first is the fact that this release marks my first encounter with this pioneer of improv and computer music—we all have our blind spots as listeners—and the other is that sinking feeling that half the hopefuls who self-identify as composers of capital-e Electroacoustic music at present hardly possess an understanding of what said idiom should entail. To them, I might offer this trilogy as a masterclass—to say the least, these pieces display an equanimous equality between performer and programming; then (and only then) can the two converge and become indistinguishable, alien, truly captivating in the act of listening.

The vivid mental imagery this stirred in me on first playback speaks to the strength of the balancing act: Claire Chase’s stilted respirations collide with displaced digital delay and leave behind that same pointillist blood spatter that makes the hairs on the back of my next stand up in the opening moments of Plux Quba; when the strained timbres of Seth Parker Woods’s cello are digitally mangled, the effect called up an octopus performing Rădulescu; Dana Jenssen’s bassoon is transfigured into that sort of shrill aviary I associate with Hitchcock’s most memorable title sequence. It should go without saying that this was an inspiring listening experience, that I want more where this comes from, and the moment I file this blurb, a deep dive will be in order.

[8]

Vanessa Ague: Composer George Lewis has long been a pioneering figure in the avant-garde. His music is the kind of music that makes you constantly think, constantly question, constantly listen deeper. The Recombinant Trilogy is no different. From its first moments, it provides us with a listening exercise: what’s a performer playing an acoustic instrument, and what’s an electronic simulation? Each track opens with acoustic extended techniques, like a flute’s echoey trills, a cello’s raucous glissandi, or a bassoon’s dark grumbles. But from there, the sound gets murky.

The most enticing tracks on the album are “Emergent,” performed by MacArthur Fellow and flutist Claire Chase, and “Not Alone,” performed by cellist Seth Parker Woods. Chase’s flute flutters, punches, bursts, and tingles with electricity, as if it’s made of shooting stars that leap across an endless black sky; Woods’s cello squeals between prickly, harrowing strokes and spooky harmonies, jumping between sporadic mayhem and ethereal sparsity. Each piece feels like six vignettes in one, smashed together by spontaneity. The Recombinant Trilogy is a resting place that makes us dig deeper to uncover what’s hiding underneath its hazy surface, to challenge us to stop and really listen. Eventually, it envelops us into its swarm of mysterious sound.

[8]

Gil Sansón: Lewis is one of the links between Black music and the European avant-garde. His work is quite varied in scope to be represented by one recording, but this one is a good introduction to his work. Lewis belongs to a generation that didn’t have the luxury to work with personal computers for his electronic explorations and only his standing in academia enabled him to work at electronic studios. On the surface, this sounds like typical fare from the post-WWII avant-garde: solo instruments with electronics, the classical “solo flute in a room full of distorted mirrors” trope being featured here for cynics to dismiss the music as hopelessly academic and square. Naturally, concentrated listening pays many rewards, and signs of identity appear as the listener gets deeper into the music.

One thing that comes out quite clear is that Lewis has benefitted from historical perspective, and he’s aware that some of those signature sounds of earlier decades have not aged well. Nothing here will remind the listener of Subotnick, for example. In fact, occasionally the ear will detect nods to free jazz (the second piece for solo cello and electronics did remind me at times of the guitar blasts of Sonny Sharrock), and there’s a melodic ear for much of the material that hints at that other side of Lewis, the improviser side.

The first two pieces are quite engaging, but the third is the one that really grabbed me and captured my attention in full. The contrasts are much more marked in this piece and the piece breathes deeper and also more menacing. The level of transformation and complexity of the brass part make for a very eventful experience, with many moments to savor. It’s a cliche to say that The Recombinant Trilogy shows a mature master in great form, but this is one instance in which the truism applies in full. This may win you over where Berio’s Sequenzas left you cold.

[8]

Jesse Dorris: The Recombinant Trilogy arrives in a field of text about doppelgängers and Varèse blurring telephones and teleportation (at which, in the depths of quarantine loneliness, I won’t pretend I didn’t ache) which (from the depths of my quarantine fog) I sort of distilled into a situating of this work as dub. This is the sound and this is the echo of the sound. This is a replication of the echo of the sound and this is a transformation of that echo. A flute swoops, waves hello to itself, ruffles its timbre and grows breathier, reminds you of lips involved, squelches. The wind from a wind instrument must come from somewhere. Cellos double and triple and compute themselves into spatters, these harsh smears which then curdle between speakers. There is no map but there are patterns, and patterns imply travel—or maybe just movement. A bassoon or its outputs crunch. They ululate like Diamanda Galás, which I’m grateful to know a bassoon can do but nonetheless makes me itch to flee. The unpredictability of Lewis’s repetitions forgoes dub’s eternal familiarity and abandons the possibility for recognition. It’s less ruminative than argumentative and, trapped for months alone or online, sounds like now to me.

[7]

Sunik Kim: The stark ‘scratchiness’ of the opening piece is a sound I’m often a bit allergic to: with a few exceptions, I often find it extremely difficult to sit through solo instrument performances or improvisations, digitally manipulated or not. More often than not, I hear what is lacking; I can’t help but wonder what other elements could intervene, raise, gather and cohere the meanderings and wanderings of the instrumentalist into a focused wave. Too often, solo works in this vein remain a stagnant pool filled with snippets, fragments of compositional or timbral ideas that are quickly dropped and rarely ever carried to their conclusions.

“Emergent” does coalesce near its end with the introduction of intense panned breathing sounds, and the following two pieces do pick up a bit; whenever things dip into the lower frequencies, my ears suddenly perk up, seeking some kind of grounding. There are compelling moments in “Not Alone” that are reminiscent of Nono’s late string works, complete with jagged real-time audio manipulation. But even the most relatively thrilling moments here (the screeching swarming on “Seismologic” being one example) feel staid and familiar, in a way that contradicts the overtly ‘experimental’ approach and methodology at play. I wonder how it would sound if all three pieces were pasted on top of one another, played simultaneously—but that might be bordering on blasphemy.

[5]

Jinhyung Kim: George Lewis’s computer music puts human and AI musicians in dialogue with each other. The latter aren’t subservient to the former, nor do the two form an indivisible performing unit; each comprises individual members on a playing field that Lewis, over the past few decades, has tried to make as even as possible. The solo works that make up this trilogy, however, incorporate live electronics to help the player manifest inner worlds of possibility. Programmed by Damon Holzborn, the software used spawns spectral performers that trace potential gestural paths and populate the soundscape with a diversity of mirror images. There’s still dialogue going on, but of a more internal and psychological sort.

The second piece, “Not Alone” (for cellist Seth Parker Woods), feels least adventurous in its probings of a purportedly wider sonic palette—possibly because the cello is already such a versatile instrument, even without extension by electroacoustic means, that it’s hard to find novel ways to extend it. Live electronics bring more to the table on “Emergent,” where they augment the dynamism of Claire Chase’s flute playing with fiery contrails of varying length and other patterns that cut through the air. On “Seismologic,” they intensify the fission bassoonist Dana Jessen generates as she smashes through the registral and timbral boundaries that normally define the instrument: we hear everything from guttural, earth-undulating rumblings (which point to the piece’s title) to strained, piquant squeals, insectile buzzing and swarming to brassy walls of sound; not a minute goes by without some kind of rupture, and the sum of these ruptures produces an undeniably electric rush.

Nevertheless, while listening to these pieces, I get the general impression that they’re test tube-ish compositions with clearly prescribed limits, lab theories let loose in an ideal vacuum or petri dish. There’s occasional awkwardness and cliché in Lewis’s earlier computer music, but it possesses an element of unpredictability that reminds me that what I’m hearing is praxis, ideas and moves being negotiated in real time. Plenty of moments on The Recombinant Trilogy feel visceral—few of them are actually surprising.

[5]

Samuel McLemore: For decades now, composers and performers have been attempting to combine solo instruments with electronic playback and manipulation. In art music the goal has varied from using technology to explore old compositional forms to mining the possibilities that were newly opened to performers. George Lewis has been using similar techniques in his music since shortly after he started his professional career. The technology has changed dramatically since the ’70s, from tape machines and banks of elaborately synchronized quadraphonic speakers to carefully programmed Max/MSP software, but Lewis’s new set of compositions, The Recombinant Trilogy, all seem to fit neatly into this nearly forgotten compositional mold.

Perhaps that explains how little new ground Lewis seems to be covering here, or how remarkably similar all three compositions wind up seeming when you play them back to back. The instruments methodically cover their entire dynamic range while ghostly copies play mirrored and distorted versions of the same. It sounds thrilling and satisfying to play, and all of the compositional pieces “fit” into each other in a way that must have been pleasing to the composer, but the audience is mostly just left to gawk at the extravagant style that’s on display. When you pause to consider just how much similar ground has already been covered by composers new and old it all seems much less interesting or thrilling.

[4]

Mark Cutler: However it is adorned, the solo-instrumental piece is quite often taxing for both the performer and listener. Even the most versatile instruments, in the hands of the most virtuoso players, can only go so far in ‘filling’ the sonic spectrum. The performer generally finds themselves venturing into stranger and more difficult territory in order to hold the attention of the audience, who in turn find their own concentration exercised by such prolonged engagement with a single source of sound. This might be partly why solo instrumental records have often found warmer reception in noise and drone circles than they have among aficionados of more conventional jazz and classical music.

George Lewis, of course, is recognized as a master by all of the aforementioned. By his mid-twenties, he had already played extensively with Anthony Braxton, and would soon go on to play on record with Gil Evans, David Murray, Roscoe Mitchell, and a stack of other jazz luminaries, as well as genre-straddling composers like Rhys Chatham and Laurie Anderson. Since then, like many of New York’s most celebrated jazz figures in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, Lewis has veered increasingly towards the kind of cerebral composition which feels more at home in an uptown recital hall than a downtown jazz club. Yet these three pieces, each written for a single instrument and unspecified digital manipulation, also call to mind Lewis’s 1977 debut, a so-called Solo Trombone Record which nevertheless employed, on its first side, extensive overdubbing to generate complexity and self-interaction.

In this way, The Recombinant Trilogy can be seen as a direct extension of some of Lewis’s lifelong concerns. On these pieces, thanks to seamless, realtime digital processing, the relationship between performer and electronics is never quite fixed. Often, the electronics seem merely to echo or pitch-shift or pan the performer’s playing, like a table of malfunctioning effects pedals. Yet when flautist Claire Chase lets her playing on “Emergent” lapse to a few, sporadic notes, digitized, pitch-shifted artefacts take over, skittering between the left and right audio channels. On “Not Alone,” the playback seems to run ahead of the player, causing us to wonder if anything we’re hearing is being performed ‘live’, or if it has all already been digested and regurgitated by some unseen machine.

As a single, hourlong listen, The Recombinant Trilogy doesn’t quite escape the pitfalls accompanying all but the pinnacles of the solo-instrument canon. Each performer strains admirably against the capacities of their respective instrument, aided by digital manipulations which occasionally warp their material into beeping, buzzing abstractions. However, played consecutively, the three pieces don’t sufficiently distinguish themselves from one another to convey to the listener a feeling of progression. It is not clear, despite its three-year composition, whether or how this ‘trilogy’ develops its central concerns. Each piece offers numerous moments of virtuosic performance and sonic delight, but I cannot say that they collectively reward listening in a single session. Rather, I’d advise picking your favourite of the three instruments, and diving in from there.

[6]

Joshua Minsoo Kim: In the liner notes to George Lewis’s landmark album Voyager, the composer writes, “What the work is about is what improvisation is about: interaction and behavior as carriers for meaning. On this view, notes, timbres, melodies, durations, and the like are not ends in themselves.” The idea is to think of music that’s aided by this sort of software—be it Voyager or what Damon Holzborn’s made for The Recombinant Trilogy—as something beyond its mere sonic qualities. I’m reminded of a quote that appears near the end of Lewis’s A Power Stronger than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music:

Really, Great Black Music is an aspect of the Holy Ghost, for us as a people […] it’s the music that brought us into existence. Great Black Music is one of the blessings that came with us standing up to a white world and saying, we’re going to do what we want to do, despite what you try to do to us. Great Black Music is a result of us having the courage to use our Great Blackness, and realizing that this is our only power.

—Ameen Muhammad

Of course, the people who partook in this record aren’t all Black, but it’s hard to listen to something with Lewis’s name—especially something that also involves AI software—and not approach it with ideas about one’s own infinitude. When I listen to the tracks on The Recombinant Trilogy, I find myself tracing melodies, trying to determine which bits are performed in the moment and which are a result of the software. At times, it’s easy to do—we may just hear a simple delay effect—but there are moments where the borders are unclear. And it’s at these borders where I feel relinquished from any such deciphering, letting myself become enmeshed in these networks of constantly-expanding sounds.

As with Lewis’s best work, The Recombinant Trilogy features a subtle but addictive sense of playful movement, one that points to newness, to a broadened identity—something further hinted at by the album’s title and the nucleotides that adorn the cover. The music itself isn’t particularly new-sounding, but one must think of the idea of music-as-Holy Ghost: it’s a familiar portal to a sense of invigoration. If you allow yourself to get lost in the breathy wheezes of “Seismologic” or the intersecting textures of “Not Alone,” there’s a marveling with which one approaches its expansive nature. To me, these pieces don’t feel like they have a discernible narrative thrust as much as they periodically bob and burst, and that’s what I like most about music like this: its unpredictability is a signpost for endless capability. Which is to say, “notes, timbres, melodies, durations” may not be “ends in themselves,” but the “ends” aren’t even what’s important; when one can feel the beauty of software-generated music as being extensions of one’s own playing, or when one can get lost in these vast and dense pieces, one is reminded of their own ongoing, limitless potential.

[6]

Average: [6.33]

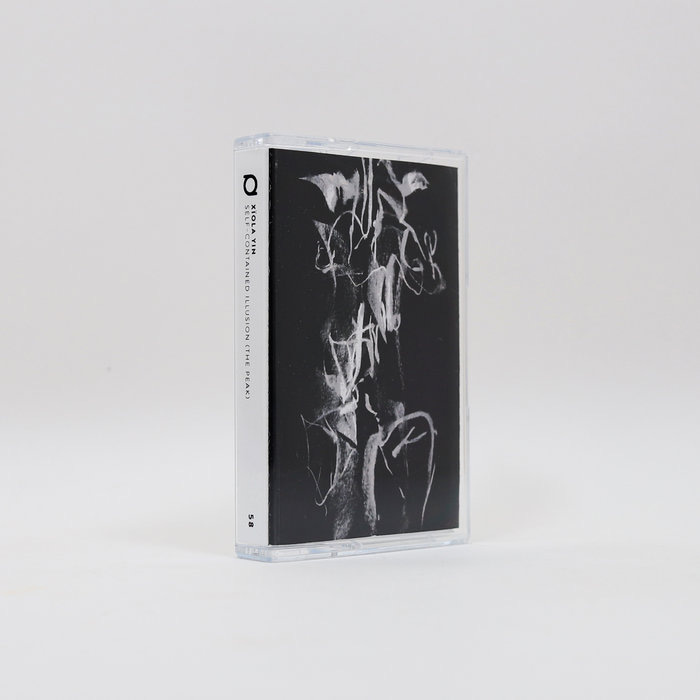

Xïola Yin - Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak) (Dinzu Artefact, 2021)

Press Release info: Xïola Yin is the opposite yet not contradicting side of Aloïs Yang. This project focuses on deconstruction of existing works and recordings, random access and blending memories. Exploring the unstable and unpredictable outcomes of digital environment, through bespoke software instrument and live improvisation.

Purchase Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak) at Bandcamp and the Dinzu Artefacts website.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak) begins with a bang: “Duplicated Joy” spirals continuously, its whooshes and whirrs and false-start revving less an assault on the senses than a bubbling stew of electronics. Given that Aloïs Yang is working with existing material, it’s no surprise that the occasional aquatic noises here bring to mind Micro Loop Macro Cycle, an album that looked at “environmental cycles through the studies of various states of water” and was far more patient. It aimed to “present how a tiny event [...] creates feedback loops that eventually can be seen as the whole”, and Self-Contained Illusion feels like the inverse: Yang presents the whole as to make evident its existence as something composed of a million tiny events. It’s a lot to take in; when the first track ends, I’m exhausted from the hyperstimulation.

Still, the best moments on Self-Contained Illusion are those that prevent me from relaxing. “Overloaded Beauty (Without Ends)” features a flurry of 2000s cell-phone-like ringtones colliding with manipulated birdsong. That one can make out that field recordings are underneath and causing all the discord grants a peculiar feeling of unrest, one of searching for a peace located between domestic spaces and a sprawling metropolis, amidst towering buildings and humanless stretches of land—I thought, more than anything, of how this could soundtrack a film like Simon Liu’s neon-drenched Fallen Arches, a work of art equally immediate in providing sensuous experiences via collaged materials, heightened greatly by the interactivity of its elements.

Not all of it succeeds: the clanging industrial beat of “Spiritual Rave (Muted)” is tedious, though does unveil more versatile utility when we hear similar noises situated in different contexts. The title track is even more dry, and its consistent beat makes evident how such an approach is faulty for reasons beyond mere stasis: when Yang employs such a method, a clear foregrounding of an individual sound strips away the magic of such cavernous sonics. “A Sinkable Chat” concludes the album with its most direct recordings of water: a fine if uneventful reminder of the album’s source material and themes.

[6]

Mark Cutler: In this extreme exercise in recombination, Aloïs Yang feeds his own recorded materials into a shredder, yielding novel and unexpected combinations of sound. Whereas Yang’s music under his own name lean into a stately, ambient minimalism, these tracks bounce and ricochet ten times per second. Massive synth chords start and stop, detune and collide with themselves as diced-up percussion rattles and spills all over the mix. Snippets of sound sometimes loop and curl until they almost resemble beats and hooks. The whole thing has a rare sense of fun, calling to mind the playful noise of Black Dice, or the tongue-in-cheek techno of Mouse on Mars.

For me, the opening trio are the most successful. Largely built around unidentifiable trickles, clangs and thuds, they feel like the best use of sound-design-as-composition. After this, vocal tracks, bird chirps and other placeable samples start to slip in, puncturing the otherworldly aura Yang had already established. “Spiritual Rave (Muted)” slows to a crawl for much of its eight-minute runtime, losing any real sense of juxtaposition between its too-literal industrial rhythm and tortured sine-wave melodics. Yang’s method here functions best when the music itself is at its fastest and most disorienting. I hope, in the future, he pushes that method to new, dizzying heights of abstraction.

[7]

Sunik Kim: The opening “Duplicated” tracks are strong—dense, focused (versus meandering), evocative of classic 90s/00s digital sounds but rooted in a novel ‘physical’ or pseudo-acoustic environment (the rattling and clacking sounds remind me of Ryu Hankil's Becoming Typewriter). The queasy ratcheting on “Duplicated Madness” and the rhythmic acrobatics on “Duplicated Duplication” engage with familiar tropes, but there is an undeniable freshness here that is uncommon in these waters—likely due to the (by definition) one-of-a-kind “memories” that Yin is fragmenting and manipulating here. The second half falters: there is less focus, more ‘soupiness’ and processing ‘for its own sake’—as a result, from its peak in tracks 1-3, the release gradually sinks into the ever-present bog of anonymity.

[6]

Jinhyung Kim: Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak) isn’t just in a state of constant flux: it’s fully committed to its indeterminacy and all the shifting layers that make it up. It respires not with calm, meditative cyclicity but heaving irregularity, a tumbling, irresistible forward motion. The shape and position of each slab of sound in the mix are clearly delineated, allowing for transitions from one sonic array of moving parts to the next to feel spatially organic, like changes in lighting on a stage—no hard cuts, no shoehorned crossfades. All too often, fluidity in synthesized music implies an amorphous blend from a rather limited aural palette, tending toward homogeneity. The tracks Xïola Yin presents here, however, are small ecosystems teeming with varieties of sounds sharp and nebulous, cavernous and narrow, grounded and ethereal. Though heavily manipulated and processed, they have the internal consistency of field recordings when taken as a whole. Neither the din of city streets nor the quiet ambience of a forest seems natural because the noises that make each up are similar to one another—it has instead to do with the ways disparate sounds coexist.

It’s not music that lends itself well to concrete analogy, but Self-Contained Illusion evokes a scene for me every now and then: an object knocking in harmonic oscillation on “Duplicated Madness,” water gurgling/wind blowing in a cave on “Overlooked Beauty (Without Ends),” some incessant factory machine rhythm on “Spiritual Rave (Muted).” I know for certain that these aren’t factual accounts of what I’m hearing—besides, the music usually shifts too quickly for there to be time to nail down visual pneumonics for your auditory experience. You don’t really need to pick it apart like that; just imagine this as field recordings from another world.

[8]

Gil Sansón: What we have here is a set of processes governing a specific palette of sound of a decidedly urban nature, presented as a collection of individual tracks that are related to each other by way of the processes and colors unique to the work, not unlike painters working by way of a series related to a single concept or idea. The sound world thrives in the gray area between noise and music, making the most of this difference for the benefit of the album, which is also helped by the engaging textures of digital food-processing origin. No track really stands out on its own—they’re all variations of this set of processes and sounds to which the artist sticks to stubbornly, and with good reason: the record is thoroughly engaging and enjoyable, having both a sense of urgency that’s not too in your face, and a playfulness that allows the listener to dig into some really tasty sounds.

[8]

Marshall Gu: At first, the actual sounds that Xïola Yin immerses you in are individually memorable. The start-stops that move to swallow you in “Duplicated Joy,” reminiscent of Tim Hecker’s Virgins; the blips coming in via Morse code on “Duplicated Duplication”; the babbling of children, distorted and far away, on a song titled “Passing by Pasts (Overlooked)” that make it seem like a distant memory. But it is unclear to me how these sonic elements relate to one another and form the eight supposedly individual songs or compositions or what-have-you of Self-Contained Illusion. Or more broadly, it is unclear to me how these songs come together as a whole—how they are supposedly the ‘Yin’ to Aloïs’s Yang. Is that ‘joy’ and ‘madness’ that are duplicated on the first two songs? Is that what beauty that’s ‘overloaded’ sounds like? It’s possible that I am digging too deeply into madman experiments and should just let the various sounds take hold and wash over me. But I’d like images with my sounds, please, and no images come to mind here.

[5]

Nick Zanca: For music in the realm of this kinetic exotica-cum-plunderphonic soup to truly hit me hard, the sounds must at least reveal remnants of human intervention, and by proxy, intention behind the cut. Instead, I imagine our assembler here running this sylvan-shamanic source material through all the LFO-controlled stochastic processing they can muster, hitting record, taking a backseat, and hoping for the best. That’s not to say the results always fall short—the concrète whirlwind that appears at halftime has potential to suck one in after repeat listening, much in the manner of Valerio Tricoli’s still-enticing tornadoes of tape—but these sections are far too fleeting for my tastes and give way to an austerity perhaps better suited for colder ears.

[4]

Jesse Dorris: My upstairs neighbor has a toddler and no rugs. The toddler rises around 6:30 AM and begins running, sometimes in circles, sometimes in tear drops, sometimes in Pollackian arcs and bends. This sets off a reaction including my lamp swinging, my cats scattering, my mood, let’s say, changing. The accretion of rhythms on tracks like “Duplicated Joy” are more interesting than what my apartment sounds like in the morning. But they’re the same sort of exploration of what happens when actions exist with each other, their relationships causal but unintentional. I’m writing this in a blizzard and thinking about dub, and that combination causes me to hear “Passing by Pasts (Overlooked)” as SND remixing Basic Channel, skipping through flooding basements. Xïola Yin surely doesn’t intend this. My windows are condensing in sync with the murky sturdy structure of “Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak),” but the other living creatures around me are on their own.

[7]

Maxie Younger: I’m a little embarrassed to admit how long it took me to realize how Xïola Yin’s name directly reflects his main persona, Aloïs Yang; it clicked for me sometime during my third listen of Self-Contained Illusion (The Peak). It’s an interesting album, one whose shuddering experiments in sample manipulation elastically straddle the line between ornamental and attention-grabbing. Where Yang looks outward, exploring the ways in which organic, aleatory exciters (the melting of ice in a bowl, the slow release of water vapor onto colored paper) interact with his unique acoustic post-processing, Yin looks inward, tearing apart and reconfiguring prerecorded material into a relentless barrage of spectral thumps, stutters and squeals.

“Relentless” is the key word here; of the difficulties I had with Self-Contained Illusion, its breakneck pace was what I found to be the hardest to reconcile with. There are few moments of real calm in the work, and even fewer of respite: Yin’s restless energy is invigorating, for sure, but it also infects his most beautiful passages with a kind of haunting, discomfiting tension. Which, of course, isn’t a bad thing per se; but, it does tend to grate after so many tracks that move at the speed of a jet plane without much in the way of an overarching rhythm to anchor them.

I find the album’s middle section, after you’ve been given some time to become accustomed to its universe but not enough to internalize all its tricks, the most enjoyable. From these tracks, “Passing by Pasts (Overlooked),” a wide, kinetic collage dominated in turns by watery sub-bass splashes, high-pitched vocal snippets that mimic birdsong, the sounds of a moving train car, and flat, eerie midrange drones, is a personal favorite. Yang likes to frame Yin as an opposite, yet complementary force to his main body of work, a cogent nod to the dualistic philosophy his two personae allude to; I certainly hope that he continues to explore both sides in earnest.

[7]

Shy Thompson: Almost all creative people have probably had the desire to destroy something that they’ve created. With finality, inevitably, comes disappointment; you realize you could have done something better, you think of something you wish you had thought of earlier, or you simply wish you could take it back and start over. To avoid the painful regret of making an attempt and being unsatisfied, I’ve struck the concept of “finishing” something from my mind. Even if I publish a piece of writing, the weathering of context will constantly change one’s perception of it. Where you found it, where you’re reading it, when you’re reading it, and what I’ve done both before and after will have an impact on how you perceive it. I can simply let something be a snapshot in time, and let the air around what I’ve created give it a flavor that might age it like wine or spoil it like milk—and I won’t worry too much about which of those ends up applying.

Marcel Duchamp worked on one of his most famous pieces, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, for eight years before deciding to leave it “definitively unfinished”—an important distinction to taking your hands off of it because you’re satisfied with the result. When the panes of glass had been cracked en route to the home of the collector that owned it, Duchamp declared the piece to have been “finished” by circumstance in a way that he never could have done himself. He decided, simply, to put the broken glass back in place and let his creation show its scars rather than replacing the panes with new ones. I aspire to that level of not-giving-a-fuckitude.

Aloïs Yang’s work is all about being a participant in the endlessly running river of time, and assuming the alter ego of Xïola Yin and taking a torch to previously existing sounds feels like a statement: don’t assume the work is finished just because I’ve put it out there. Not being familiar with the source material being manipulated here, I still get a clear feeling that some scars are audibly showing on these recordings; sounds stutter, distort, unravel, and sound like they’re flaking away from the canvas to which they’ve been applied. Replacing the broken piece of glass is like trying to fight entropy. You’re swimming upstream against a river that’s running faster than your limbs can propel you. Letting the cracks show tells a story—one you can still be part of as long as you’re willing to hold up the frame around what’s left.

[6]

Average: [6.40]

Thank you for reading the fifty-first issue of Tone Glow. Listen to your little voice.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi or becoming a Patreon patron. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.