Tone Glow 043.8: Stuart Moxham (Young Marble Giants)

An interview with Stuart Moxham for a special midweek issue. Plus: Moxham shares 20 of his favorite albums.

Stuart Moxham

Stuart Moxham is a Welsh singer-songwriter and guitarist who was part of the minimal pop trio Young Marble Giants. In the years since, he’s released music as The Gist and under his own name. This year marks the 40th anniversary of Young Marble Giants’ landmark LP, Colossal Youth, and Domino is marking the occasion with a limited edition reissue. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Stuart Moxham on the phone on November 19th, 2020 to discuss Young Marble Giants, working on a farm, how he ended up as a painter for Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and more.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hey Stuart!

Stuart Moxham: Hi Joshua!

Just wanted to say thanks for making the time to do this.

I’m really sorry that I didn’t make it a couple times [Editor’s note: this interview had to be postponed multiple times]. I’ve got this heart thing and I’m just exhausted all the time, really. If I forget to set the alarm then, well, that’s what happened. But we’ve made it! And I’m glad!

I’m glad too! And don’t worry about it.

Where are you calling from?

I’m from Chicago.

Ahh, I wish I were there. I love the place. Especially now. How’s the atmosphere? Has it lightened a lot?

Our state is doing pretty bad with the coronavirus. There was a stay-at-home advisory issued on Monday. We have holidays coming up so I’m worried about what everyone’s going to do.

It is bad for you, but if you think about it this way… the UK is the 5th worst in the world and we’ve got like 69 million people in the whole country. We have a bloody worse-than-useless premier. Anyway, I wasn’t thinking about that. I was thinking about the fact that Trump is now throwing his toys out the pram on his way out, isn’t he?

Oh, right. It was nice to see him lose. He keeps going on about the results being fraudulent so it doesn’t seem like he’s gonna leave without putting up a fight.

Do you think that’s because he’s gonna end up in prison or… he’s gonna have to top himself or something. He’s got all these lawsuits and these debts; the whole world knows that he’s a failure and always has been, and that’s the last thing he ever wants to face, so that’s why he’s doing it.

He has both a large and fragile ego, and this sort of thing has come to be totally expected. I think that’s part of it, yeah. How has your day been?

The day today? It’s sunny. I was gonna get on my motorbike but I came over here to my partner’s and of course we got talking so that didn’t happen. I’ve got another interview after this one so I think that’s gonna reduce the possibility of being able to get on my motorbike and go down to my studio. I’ll have to get in my car instead (laughter). We are in lockdown by the way, but this is for work so I’m allowed to do that I think.

Do you just have one more interview after this?

Yeah, and I’m also doing a written one for Billboard. There have been a lot of in-depth interviews lately. Also, I’m on Facebook and have been on it for years. And, like everyone else, I spend a lot of time online and being confronted with people’s truths about something that I’ve had a hand in making… you sort of have to accept some sort of astonishing things. It makes you rethink things and you see them in different ways, which is good because it gives me new things to say.

What are these hard truths? Like with Young Marble Giants being super meaningful to a large number of people?

Yeah, but they’re not hard truths. Well, they are hard truths in a way because lots of people, ranging from Simon Reynolds to Richie Unterberger to a random person on a YouTube comment to people you meet at gigs to people who write books to people who want your music for films… all this stuff just happens. I can only speak for myself—I can’t speak for Phil or Alison—but it’s completely astonishing.

It’s difficult to talk about this because I have to accept in a non-egotistical way that I’m responsible for making a positive difference in how many hundreds of thousands of people’s lives. I’ve done something that I wanted to do. I achieved it. And I didn’t know anything about how to do it and it’s a miraculous thing. I have to accept that I have certain abilities and that’s really difficult to do. And how do you live with that, how do you square it?

On the one hand, I hoped that it would be successful but I had no idea what that meant. On the other hand, I always had a feeling—and it was very, very buried—but always as I grew up, I had a feeling that our family somehow had something about it, that there was something extra going on. My parents are amazing people. They’re beautiful, honest, educated, working class. My extended family as well.

I remember things that happened in my youth, when I was a teenager. For instance, with my first love when I was 15 at school. This was my first proper relationship and it ended when she said, “When are we gonna get married then?” To me it was like the crack of doom. I loved her and she was beautiful but I suddenly realized that I had something to do in life, and I guess this was what it was. It’s a calling, it’s a vocation, actually.

Yeah, for sure. You said that your family was super close. Do you mind sharing a memory you have with your brother?

With Phil?

Yes. Can you share a memory that paints a picture of who you two were as kids?

There were actually four of us. Our elder brother died at the end of August.

Ah, I’m sorry.

Thanks. Richard and I just had two years between us, so we were sort of a pair. And then there was a five-year gap before Phil arrived and I think a four-year gap before Andrew arrived. Richard and I are ’50s babies, while Phil and Andrew are ’60s babies, so it’s a generational gap as well as a birth gap. In a way, I was focused on my elder brother up until he suddenly disappeared—he joined the Royal Navy when I was about 12 going on 13. I felt bereft, you know? I was depressed. I was bereaved, in a way, because he had just disappeared. I didn’t look towards Phil because Phil would’ve been 7 or 8 years old then.

Phil and I were brothers and we loved each other but we weren’t really close in that way. He was too young for me to hang out with. It was only when I started to learn the guitar at the age of 20—when Phil was 15—that I felt this tremendous desire to teach everybody the guitar because for me it was the key to my future. I suddenly realized that this is what I want to do with my life—to write songs—because music had never crossed my mind before.

So I taught Phil how to play the guitar, or just started him off. There used to be a catalogue where you could mail-order guitars and we never had any money so me and Phil would be looking through this catalogue and going, “Aw look at that one! I love that one, that’s my favorite!” I bet Phil remembers that well (laughter). We didn’t know anything about guitars or what the differences were; we were just looking at the pictures.

The funny thing was—just as a little addendum to that—that at one point, I got really hacked off. I was like 21 and nothing was happening in my life and I wanted to get the hell out of Cardiff because I had been there all my life. I got on my motorbike and I headed across the country and I was away for a few months. I was working on a farm in the winter in Norfolk and I popped back to Cardiff every now and again. It was absolutely insane—an eight hour journey. Suddenly, my mate who started me on the guitar asked Phil to play bass and they had formed a band to do cover versions. So Phil went from being my kid brother learning the guitar to being a bass player in a band, and I wasn’t in the band! They asked me to join as a singer and that’s what happened there.

What was it like being on that farm?

I loved it. We all come from farmers, don’t we? It’s in our genes. I know that my ancestors, the English Moxhams, come from Gloucestershire, which is just north of Bristol on the other side of the River Severn from South Wales. I think it’s in my blood. It was January and I was shoveling out three feet of compacted cow shit. It was really hard work but I absolutely loved it.

The thing I liked best was that all the other laborers on the farm were old men, probably in their 50s or their early 60s. They were proper old Norfolk boys and they had such a brilliant, dry sense of humor, which was new to me. They would play practical jokes on me because I was younger. They’d be like, “You’re a student, aren’t you?” They couldn’t place me. And actually, I had done something unusual, to rock up in deeply rural Norfolk and take a laboring job. What happened was that the farmer was very paranoid about me overstaying my welcome. It was a temporary job, and I knew that, but he kept saying to me, “You realize you’ve only got another eight weeks to go, don’t you?” And I’d be like, “Yeah, yeah, sure.”

Anyway, I was living in a youth hostel in Norwich, which is the capital of the county town of Norfolk. There was this couple running this youth hostel and, it was probably against the rules, but because it was winter they were letting people stay for nothing. I don’t think I paid anything. And it was a brilliant scene—there were all these travelers and stuff. But eventually, after the weather improved, they said that the season was about to start and that we’d all have to find somewhere to live.

So I thought, alright, I’ll get a camper van. And this was long before anything digital existed. Somehow or other, I found this scrapyard, but it was a rural scrapyard—it was in fields. It was extraordinary. I went there on my motorbike and it was a long drive to the farmhouse, and on either side of the drive—it was a bit like something out of the Second World War—there were ancient vehicles from the ’20s or ’30s just rotting away in these ditches.

I got to meet the farmer and he had separate fields. He had a field full of buses, a field full of cars, a field full of lorries, and a field of caravans and camper vans. And I bought this beautiful 1960s camper van and the farmer allowed me to live in it on the farm until I finished my job there. So it was a really happy time.

Was it a hard decision, then, when you came back and decided to make music?

It wasn’t because I couldn’t find another job. The only job I could find was on a turkey farm, and I really didn’t wanna do that. You know, who would want to work on a bloody turkey farm? Disgusting (laughter).

So I had been going back and forth to Cardiff anyway. I’d gone back and the first time I ever saw True Wheel—the band with Phil—I met Wendy Smith. I asked her for a dance. It was a momentous night because they had asked me to join the band and I met my new girlfriend all in the same evening. And I had plenty to go back for, so I got in this camper van—and I wish I had it now because it’d be worth tens of thousands of pounds, it was so rare and I’ve never seen one since—and I lived in it for a while and then Wendy and I got a flat together. By then I was in the band.

I didn’t realize you met Wendy on the same night. And she’s been a part of the band in some way, in helping with art work. Did she help out the band in any way aside from doing some art?

No, because at that time we were still in True Wheels. I really can’t remember the timing with how long that band lasted or anything. It wasn’t very long, and I don’t know why it finished either, but what I do remember is—and this was probably in September of 1976—we parted. She left and went up to get her art degree in Nottingham. And I was on my own in the flat then. And then we started Young Marble Giants. And I’m sure you know that whole story so I won’t bother sharing it.

So you were the principal songwriter and lyricist of the band. When writing these songs, were you keeping in mind the fact that Alison would be singing them? Were you thinking about her voice, the way she sings, the fact it was someone else singing it—was that distance something you were thinking about?

That’s a very good question. I’ve only realized this after years of talking about it, but at the time, the thing that excited me about writing for our band was… to me, everything depended on the success of this. My future. Everything. I can’t tell you how profound that was. And yet I didn’t know anything about how to do it. I had only been writing really terrible songs for three years on an acoustic guitar. I never played anything, never recorded anything. I felt like this was my one chance to start a career. So it was a massive, massive ask. I didn’t communicate that with anyone, not verbally at least.

So for me, I had this idea that in order to make this less daunting, I’d write for an imaginary band. What would I like a band to sound like? What would I like a band to play? What would I like to hear? So that was one stage removed, musically. And then having someone else sing it was another stage removed. And then having a woman sing it was another stage removed. All these things made it possible, actually, to write lyrics that meant anything. I didn’t do that before, I didn’t know how to do it. I wasn’t conscious of not knowing; I just didn’t like what I was writing. There was maybe a line that was okay, and maybe some of the music was okay with the earlier stuff, but this band was the catalyst for me, personally, to be able to write.

The other element to [your question] was about Alison’s range and all the rest of it. I mean, I didn’t know anything about those things—I don’t know much about it now! It was just very fortunate that she has a brilliant ear. The way it worked was that Phil and I would sit down together and I’d say, “What do you think of this?” I’d play him a riff and he’d go “Aw yeah” and he’d start playing the bass. It’d be great. And we’d start to write and I’d sing the words.

Then at a later time, Alison would be there and we’d play it for her. And she would get it note perfect and, even more importantly, I had no idea if she’d be able to sing it—if it was in her range—but it always was! Just by pure chance! And also, the phrasing—and obviously I’ve worked with lots of people since then—and people like Louis Philippe, who knows everything about music—is always complaining about how hard my phrasing is. But she never had any problems! I just thought that anybody could do this stuff. I didn’t really value what she was doing and how unusual it was that somebody could do those things (laughs).

Obviously you needed the other band members to do what you needed to do, but you also needed them on a deeper level. You wouldn’t have been able to get to this point without them, without feeling this comfortable.

Absolutely.

You were talking about this imaginary band you had to help you get in the mindset for writing music. Were there reference points you had? What were you thinking of?

It was more a question of what we didn’t want. Phil and I really knew what we didn’t want. And I remember Phil saying to me, “So what sort of sound are we gonna go for?” And I was like, “What do you mean what sort of sound?” “The overall sound of the band.” And I hadn’t thought about that before. Musically, it was very much between Phil and I. He was always the one who would get the say on whether we’d do something or not—he was the taste filter. 90% of the time he liked what I brought out, so that was fine.

It’s something I haven’t gotten to the bottom of… this ability to do something good when you don’t know what you’re doing. So we threw out everything. All the stuff we thought was cheesy. Because music was so linked with shareholders and money—it was a totally conservative thing—we just threw out stuff like introductions to songs, strings, brass, choirs. We don’t need any of that stuff! What we need is great songs, and we want to be as minimal as possible.

What we were doing was reacting to punk. Punk was, I thought, so overrated musically. It was rock ‘n roll all over again but a bit faster. In those days there was this thing, rockism. We didn’t want to be rockists. We didn’t wanna do encores! We refused to do them to begin with. All those conventions, like… why? It’s fake! It’s phony! So we developed this attitude. It was like being in this gang. When you’re in a gang you have this philosophy and it was really great. It was one of the most enjoyable things about being in the group. We felt very strongly and confident after writing our one hour of music.

I was convinced it was gonna fail. We might as well have been in Tasmania, as far as the music business was concerned. And nobody had ever made it on a street level that we knew of. In fact, they had, but I didn’t know about them. Amen Corner, for instance, were a Cardiff band. It was kind of a crucible, it was a massive challenge in a lot of ways. The only way to get attention was to be as gimmicky, as original, and as different as possible. Very quiet, very minimal, totally about short and very melodic songs. I’m a Beatles boy. That’s how I grew up, with that music—The Kinks and people like that.

On one hand, we were very anti-everything and on the other, we were very pro-good music. My dad had been a singer all his life—the highest amateur level. He sang for the BBC Welsh Chorus for years and he was also an actor at a very, very high amateur level as well. So the house is full of this classical music and also musicals. He and I acted in musicals when I was a kid. And we all went to church and sang beautiful hymns and carols. We came from a family which was culturally aspirational but not materially. Education and culture were the great things.

Do you mind sharing about one of the musicals you acted with him in?

The main one was The King and I and I played the junior lead—I was about nine. I played the part of Louis Leonowens, who actually is the first person on stage at the very beginning of Act I and says the first lines. This was in the only theater that was in Cardiff. Proper proscenium arch and red plush boxes—the lot. [In the play] there’s a ship going into the Bangkok harbor, supposedly. On the first night I ran on stage and went, “Oh look, look! It’s the lights of Bangkok!” And that was the cue for the captain, who was in his little wheelhouse on the stage, to give his line. But the actor was drunk. I didn’t realize this—I was oblivious to this—and he didn’t say anything (laughter). He didn’t say anything! So without missing a beat I just gave him the line again and my dad told me later on that this actor was bloody unconscious—he was drunk! My dad and the producer were in the wings, saying that I gave the line again like a true professional! And the show went on (laughter). I was also a spear carrier in Camelot.

All the auditioning, meeting all the grown-ups, the makeup, the rehearsals, the whole build-up and the whole show biz dynamic of, oh, everything’s relaxed and happy at the beginning and then it all gets a bit serious and tense and then “Oh we’re not ready!” and then bang you do the show and it’s marvelous! I was addicted to that straight away. Of course in later life, I worked on cartoon feature films like Who Framed Roger Rabbit and the one after it [The Thief and the Cobbler]. And it’s exactly the same thing there. Everyone’s laissez-faire to begin with. “Oh we’ve got all the money and all the time.” And then it gets absolutely insane and intense and shouty and tearful (laughter). It’s beautiful! I love the theater.

It makes so much sense to me, from knowing that you love this sort of environment, that you’re a “born show-off,” as you said in another interview. And that you sort of filled this role in the band compared to Phil and Alison.

I guess so. It gave me stage confidence, which is a wonderful thing to have. Alison always really struggled to get on stage. Right up until the last time we did it, she was kind of using all these techniques to keep it together. She found it really hard. And, well, Phil… he’s a bass player. Bass players, they turn their back when when they stand behind curtains (laughter). It’s the nature of bass players.

People are drawn to instruments for a reason. It relates to your personality.

Oh, absolutely. It’s corny, isn’t it? But it’s true. The lead guitarist is too loud, the drummer wants to write the songs on his drums (laughter). It’s a very tricky business forming a band because you have to have equal commitment. That’s a huge thing. And that means time. Everyone has to give time and be there. It’s very demanding. It was easier for us because it was really me and Phil, and Alison could come in and she’d pick up the songs immediately. She got them and never lost them, ever. They’re in her, you know? She was ideal.

In a way, that band was relatively easy. But in some ways it wasn’t because I was really horrible. I was always trying to kick Alison out of the band because I wanted to sing my own songs. Luckily that didn’t happen. But it was horrible for her, and we never talked about anything. Certainly, Phil and I came from a family where you could never talk about anything actually important. Like a lot of families, there’s a lot of taboos. And of course that’s a weakness because once things get really tough on the road, you’re not talking about it. It all builds up and up and up, and then it crashes. Which is what happened.

Wow, I didn’t realize you were trying to kick her out of the band.

I don’t like to admit it but it’s true.

It’s interesting hearing you say this because when I was talking with Alison about the band’s end, she was saying how much she wished there was better communication.

Right. In later life, in recent years… I have my own children and I’ve also worked with kids in various ways and in various jobs—I’ve had lots of different day jobs—and it struck me that when you’re 20 to 25, you think you’re there, but you actually don’t know anything.

Everyone focuses on the teenage years, which are fascinating because they’re transitional and messy and intense—you’re getting your first sexual feelings and experiences and whatever—but then you’re out of school and you’re on your own and having to make your own way. And you don’t feel like when you were a spotty teenager, because you’re not—you’re an adult. But you don’t really know anything. All you’ve done is been in school, and school is a ladder. If you want to get ahead you just keep climbing the ladder and life is nothing like that.

It depends what you do—if you join civil service for life, that’s one thing—but [for most people], suddenly, there’s what’s called the mire of options. And most people don’t know what they want to do, do they? They just settle for something or events lead them somewhere, but if those things don’t happen then you’re kind of… hmmm. So what people do now, or what seems to happen now—at least certainly in this country—is kids go to university and have a gap year before, during, or after it. So that’s a way of getting away from home, which I didn’t have because I didn’t go to university.

So we were people who didn’t talk. And I should speak only for myself: I didn’t know anything. I just had a bit of wit and cunning and I knew I had to pull something out of a hat, musically. I wasn’t really conscious of my ignorance. My friend Matthew [Davis], who started me on the guitar, was much more worldly. He’d come from an English public schoolboy background—he’d read NME and I’d never heard of it. I mean, Wales is the poorest country in Western Europe, so I just wasn’t in that milieu of people who were up on what was going on.

I didn’t know the competition. I was like a hermit in a cave who, well, someone gave him a guitar and he played it in a way that no one’s ever played it before. There was a sui generis thing going on. And it was driven by fear. My god. I’m 24, I don’t know what the hell to do, and I’m off the dole and working in bookshops and hospital kitchens and I even did life modeling for a while in the art college. I was just banging around Cardiff. Deep down I had this feeling that there was something I could do. It was the vaguest thing in the world but it was there in the dark.

You mentioned earlier how you were on Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and I know you were also on The Thief and the Cobbler. What do you feel was your big takeaway from working in these animation studios?

It was a different world, it was a different level. Everything about it is very pleasant. You’re in a silent room, pretty much, and everyone’s got headphones on. You’ve got the joy of an inbox and an outbox, and you can see what you’re achieving. It’s a bit like that scene in Bruce Almighty where he meets God and he’s sweeping the floor. You know that one?

Yes I do.

And he says, “I can’t believe God is sweeping the floor.” And God says, “There are very few jobs in life where you get total satisfaction. There’s the muck, you sweep it up, and you see it clean.” It’s like that. The actual nitty gritty is very demanding of your patience. It actually taught me patience and taught me to be physically accurate. If you make a mistake you have to start over, and if you made the same mistake all day, you have to scratch off what you’ve done and the next day you have to go do it again. You only make that mistake once.

Other than that, the money was really good. That’s the main thing. And that made a huge difference. And it was also a great bunch of people and a nice business to be in. In terms of all the jobs I’ve done, the basic fact is—in a way to my detriment—I’m so focused on writing that I only ever do jobs that have no responsibility, where you’re the bottom rung of the ladder, where I can go home and get back to what is important. So I was never earning good money. I was mostly driving, doing driving jobs and things like that. So doing animation was definitely a step up. And I got above the first rung. The first rung is painting—cel painting—and the next one is tracing. And I became a tracer on The Thief and the Cobbler. And that’s better money again.

Was there a reason you didn’t go further into that world?

Well, actually, it started when I was still in Cardiff in the mid-80s and I’d met Cindy, who eventually became my wife. I thought, mmm, I better get a job here or I’m gonna lose this woman. A couple of friends told me that there was work in an animation studio in Cardiff and it was the people who made a children’s cartoon called SuperTed about a teddy bear and his friends. I went down and met Phil Watkins, a guy who was the head of paint and trace.

I did a test, and I’ve always been good at art—it was my major thing apart from English at school—and I was confident and I got the job. It just so happened that SuperTed was very successful. It was the first thing that Disney licensed in their history. So what happened was I was with Cindy for a little while—probably about six months—and she had just finished her degree in art at Cardiff and wanted to move back to London, since she’s from that area. She wanted to work in the West End in fashion—she did textiles and stuff. So I had a choice: Am I gonna say goodbye to this relationship, stay in Cardiff, and move up, or am I gonna go with this lovely girl to London? And I went with the lovely girl.

There I became a bicycle carrier. I’d seen these guys go around in London with these radios and I thought, “Oh, that’s glamorous. I fancy that.” So I must have been the oldest carrier in London (laughter). I can’t believe I did it. It would kill me just to get on a bike now. I would commute to London and cycle around all day, cycle home. And one day, I had this letter to deliver to Walt Disney UK. And I thought, “Walt Disney UK?” I went into this massive building in Tandem, which is this massive studio doing Who Framed Roger Rabbit and I went in and I gave this lady the letter and I said, “Are you looking for cel painters?” She grabbed me and said, “Sit down and do this test.” And that’s how I got into it. It’s like a film, isn’t it? That’s how I got the gig.

Wow. Do you feel like you’re the sort of person who constantly needs to do new things?

Good question. Yeah, I do like novelty. I think I’m very restless. I worked it out recently: I left home at 19, and I’ve moved house a lot and I had one six-year stay in one place, and I worked out all the addresses and I’ve averaged it out and I’ve moved every six months of my life, including when we were married. It’s kind of pathological, isn’t it?

You’re still currently moving every six months?

Not anymore. I’ve been where I am now for… it’s coming up to seven years. I’m very happy I’ve found a place I love to be. I love it here. Everything seems to get better as you get older. I suppose the main thrust of my personal life has been to untangle my poor mental health, so I’ve been on that mission and I’m still on that mission. I’m not the sort of person who locks things away—I’m open to discovering things.

My surname, and I have this on very good authority, “Mox” is from the Greek for “soon” and “Ham” is Old English for “Home.” So I’m a home-loving person but I also love traveling. Even if it’s just going on the motorbike to go to a corner shop. And I’m a person who’s never had a proper career in anything. I’ve done an office job and, Jesus, I never want to do that again. That world where you’re hungover from the night before because you’ve been out with everyone in the office, and then you go to work and you go to lunch with them and you go to the pub again in the evening—your whole life is the job. It does my head in completely. In fact, I got sacked and they said, “We’re gonna have to let you go Stuart—you’re too much of a free spirit.” I thought, “Well, I’ll take that!” (laughter).

In a funny way I’m very secure. I had a very secure family, and it’s allowed me to live in this fairly risky way. I look back on it and there have been many times where I’m skating over homelessness and not even realizing it. I’m always focused on music and songs and that’s my heroin.

Is there anything you miss about Cardiff? I know that you weren’t fond of it.

Well, I love it as well. I mean, I do love it. It is home, really, and always will be. (thinks) Anything I miss about it… (pauses). Well, I miss the past. If I go there now I don’t recognize it—it’s so different. Like everywhere, it’s changed so much, and deteriorated as well. It never used to be people getting absolutely slaughtered and pissing in the street, and women doing that as well. To me that’s really grim. I miss it in a nostalgic way, but it rains more in Cardiff than it does in Manchester, and that is hard to put up with.

I know you have another interview soon, so I want to just ask two more questions. We haven’t talked at all about the music you made after Young Marble Giants. And you had an album this year too, The Devil Laughs. How do you feel like you’ve grown over the years and what sort of things do you still want to do with your life? And this could be music-related or not.

I didn’t consciously do this but I had to get out of the Young Marble Giants musical formula, which was much more difficult than I thought it would be. And I’m still struggling to get completely out of it. I think I sort of found my singing voice. A lot of the progress I’ve made has to do with recording—I love that stuff. I recorded before I ever picked up an instrument; I always loved that technology and that skill set. I do things like mastering now and I’ve recorded other people and I love that side of it.

Musically, and I wish I had more time to talk about this, with Young Marble Giants I knew exactly what to do, and I felt very confident about it. Coming out of that, I was very wobbly and I had no idea what I was doing. I felt numb emotionally. It’s like a divorce when a band splits up. And I just worked on absolutely basic… I can’t explain what I did. The early Gist stuff, Embrace the Herd, I was still recording in the same studio that Young Marble Giants recorded in. And in fact, our last session was a double session where we did the Testcard EP and then I did the early Gist stuff with Phil [Moxham]. That’s all a daze. I really don’t know how I did “Here Comes Love” and “Yanks” and things like that.

And then I was squatting with the remnants of Essential Logic, with my mate Phil Legg from the band. He got me into multitrack recording and that became my way of composing, really; Embrace the Herd is my sketchbook of teaching myself to multitrack. So there was that stage, and then I moved back to Cardiff and hunkered down in ’82 for the long run. I followed my nose, and I’ve always followed my nose. Somewhere in there I found my voice, and I can actually hear it if I listen to Holding Pattern and Interior Window and The Devil Laughs. I can actually trace the development.

In ’85 when I went to London with Cindy, when I left Cardiff, I decided that I was gonna have to be a solo artist with an acoustic guitar and I did a few gigs like that. I just saw myself in that mode and I’m pretty much still in that, but it’s much more now about making recordings, about production, about being a solo artist but making much more involved recording. Overdubbing and stuff. It’s about record production. I feel like I know how to write a song—my brain is hard-wired to do it—so that I don’t really have to worry about. There’s a lot of material that’s not been recorded, and I’m writing new stuff. So it’s about the studio, it’s about bringing the best out of a song, and still in a minimal way and still with very short songs.

Are there still things you wanna do in life outside of music? Or do you move spontaneously through life?

To put it in a word, I’m sort of stuck. I’m emotionally stuck by childhood trauma. I’m realizing, and I’ve had some therapy, that most of my life’s been dictated by that and a total lack of money. But now, over the years, and with the help of partners and therapists and my own children and friends and experiences and reading and all that, I’m writing about all this stuff in my songs. I’m starting to break up that stuckness. I’d like to break that up. I’d like to be free of these restrictions. For the final chapters of my life, I’d like to be financially comfortable.

My music is so nourishing for me. I love it so much. And also writing. I do write a lot of poetry, and have done so ever since the late ’80s. In fact I’m having several books published starting next year hopefully. I have three beautiful, well, they’re not children anymore, but three beautiful children. And I have a wonderful partner and I live in a place I love. I’m a pretty happy guy, I’m glad to say.

I’m happy for you, and I hope you get to a stage where you can be financially comfortable soon.

Yeah. It’s actually starting to happen. I’m working with John Henderson at Tiny Global Productions. He’s an old friend from the early ’90s and he’s a fantastic human being and he’s just the right person for me. We’re just starting to make something really big happen. The Devil Laughs is the first record that’s made a profit since Colossal Youth. Check it out!

And there’s stuff in the pipeline. The next thing is gonna be called Fabstract. It’s gonna be a career-spanning release and it’s gonna have everything, including unheard Young Marble Giants stuff and not-very-well-exposed stuff. My plan, and this is an exclusive, is that I’m gonna put out booklets of beautiful fabstract art that I’m gonna invite friends to contribute to. And the cover of the record is a painting by Wendy Smith’s brother Duncan, which I just love. It’s this lovely abstract image. But hey, I better go.

I just want to say thank you so much! It was a pleasure talking with you.

It was fun. And back at you, see ya.

Purchase Colossal Youth at Domino.

Stuart’s Picks

I asked Stuart to create a list of hisfavorite albums. The following 20 albums were what he sent to me and are presented in the same order. Discogs pages are linked for each record.

Blind Faith - Blind Faith (Polydor, 1969)

Eiks - Morsel Of Love (Bibichan, 2013)

Emilíana Torrini - Fisherman's Woman (Rough Trade, 2005)

The Beatles - A Hard Day’s Night (Parlophone, 1964)

Les Swingle Singers - Jazz Sébastien Bach (Philips, 1963)

Emerson, Lake & Palmer - Pictures At An Exhibition (Island, 1971)

Iggy Pop - The Idiot (RCA Victor, 1977)

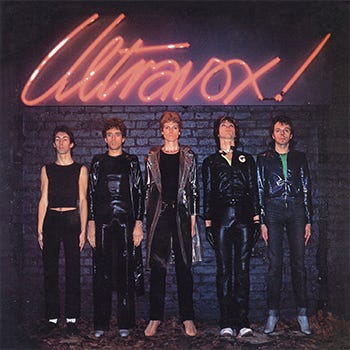

Ultravox! - Ultravox! (Island, 1977)

Bob Marley & The Wailers - Exodus (Island, 1977)

Steely Dan - Pretzel Logic (ABC, 1974)

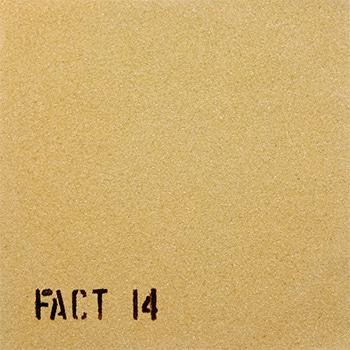

The Durutti Column - The Return Of The Durutti Column (Factory, 1980)

The Beach Boys - Pet Sounds (Capitol, 1966)

Joni Mitchell - Blue (Reprise, 1971)

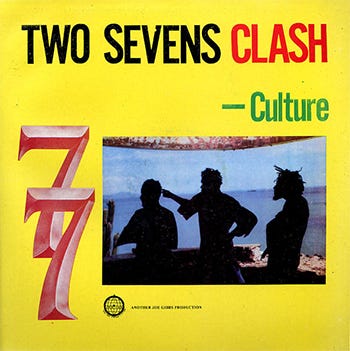

Culture - Two Sevens Clash (Joe Gibbs Record Globe, 1977)

Eek-A-Mouse - Skidip! (Greensleeves, 1982)

Nick Drake - Five Leaves Left (Island, 1969)

Little John - Reggae Dance (Midnight Rock, 1982)

Brian Eno - Before and After Science (Polydor, 1977)

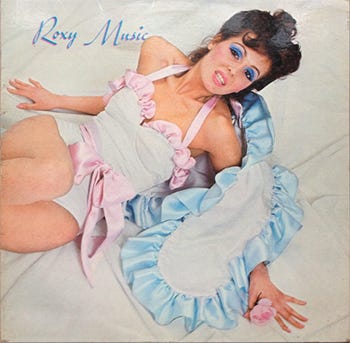

Roxy Music - Roxy Music (Island, 1972)

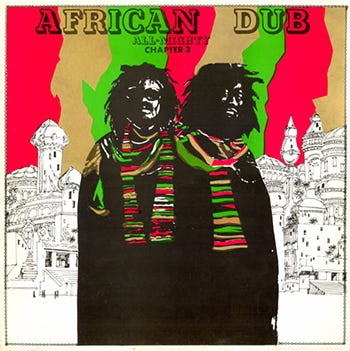

Joe Gibbs & The Professionals - African Dub All-Mighty Chapter 3 (Joe Gibbs Record Globe, 1978)

Thank you for reading our special midweek issue of Tone Glow. We hope all our readers can be financially comfortable.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.