Xper.Xr

Xper.Xr is a legendary, if poorly documented figure in Hong Kong’s experimental music scene. He first became active in the late ’80s “after a steep learning curve and gobbling up every piece of musical rebellion [he] could get [his] hands onto,” and put out his debut cassette Murmur in 1989. For the majority of his recording career he lived abroad—mostly in the UK and France—but he returned to Hong Kong in 2013 to open the short-lived underground venue CIA, his “payback to the HK arts and music scene.” CIA put on gigs that would be hard to imagine happening elsewhere in the region, like an Aktion for Austrian artist Hermann Nitsch, and a rare Asia booking for Slovenian industrial band Laibach.

Earlier this year, Xper.Xr put out his first recording in 14 years, “Mein Corona,” and has lately been working on various projects with Hong Kong art space Empty Gallery, which is preparing a “greatest (s)hits boxset” reframing his recorded output. Ever a provocative figure in his local scene, Xper.Xr gives his unfiltered take on Hong Kong’s experimental music world then and now in the conversation below. Josh Feola interviewed Xper.Xr via email in October, 2020 to discuss his musical career, the scene in Hong Kong, and more.

Josh Feola: First of all, what are you up to now? Are you in Hong Kong? What current projects are occupying your time and attention?

Xper.Xr: At time of writing I’m indeed in Hong Kong and intend to stay here for the biggest show on earth. After all, it took this long and now that I have a front row seat, it’ll be good to sit through the credit rolls. There might even be an Easter egg just after that.

There’s a few parallel art projects that are in the pipeline with the Empty Gallery: a greatest (s)hits boxset as well as an exhibition that was originally scheduled for July, but due to the current world order, it is postponed indefinitely until the apocalypse reveals itself. On the other hand, a chance also presented itself to help create a new art space called The Catalyst, and naturally the logistical and curatorial side is demanding.

But for the past few years, using alternative medical methods to help people to restore their health has been my main focus: Yes, I’ve indeed become one of those quacks, but I’m also happy to say quacks seem to offer some good results in recent times, which is a huge relief. Though, it’s important to also remind oneself life is fragile, and it is sad to see that there are many who have perished not knowing the truth and did not know their choice and options when it comes to health matters.

I also cook and fix cars.

How did you first begin making music/sound? Were you performing or recording much before the release of your 1989 debut cassette, Murmur? What venues, labels, other artists, etc. were around in Hong Kong at the time? Was there any individual or group that was especially influential to you at the beginning of your artistic career?

The beginning was often more mundane than most would have thought… that was around 1988. After a steep learning curve and gobbling up every piece of musical rebellion I could get my hands onto, it’s only natural that one would want to be able to produce one’s own response to what was important then—what does it all mean? What is creativity? Are these just random noises or is there something more to it? Like all truths, they cannot be told, but only experienced.

Come 1989, and after practicing the art of electrifying electric guitar for the past 7 years, it was time to do something radically different. In the bedroom. Murmur was glued together over many layers with a cassette recorder and an extremely undignifying 4-track mixer that happened to lie around near the bin.

As for the climate at the time: There were some groups playing “alternative” music, but more akin to… well, pop music in my humble opinion. Such as The Box, Blackbird, to recall a couple. But what enlightened me the most back then wasn’t so much what was around, but a fanzine called The Monitor, writing on many of the most iconic groups. It really did provide something critical that was otherwise unheard of in the mainstream media back then. The philosophies and ideologies brought more impact to me personally than anything else.

I’d say what really got me started was the UK experimental group Zoviet France. There were the more legendary names around such as Throbbing Gristle and S.P.K., Nurse With Wound, and Neubauten and co. But Zoviet France’s “packages” literally have their listeners meet more than the ears—the way they have designed the jackets was really an art in itself, and it’s something that impressed me most back in the days.

Can you describe some of your earliest performances in Hong Kong? I've talked with people from the HK experimental music scene like Nerve, and it seems there’s not much documentation about the underground music scene in the late 80s / early 90s. I know from past interviews I’ve done that you performed with Otomo Yoshihide in 1993 at an event organized by Dickson Dee’s Sound Factory label—I’ve heard from several people that this was a particularly influential event.

I’ve also heard about a memorable performance you gave around then at a small bar called Amoeba. In other sources I’ve seen spaces like Quart Society Gallery mentioned, but very little info beyond just the venue name. Can you describe your early shows? Where in the city were they held, what other artists did you share the bill with, what was the audience turnout and reaction like? Were your early performances organized within a group of other musicians or was it a more interdisciplinary group of visual/performance/sound artists?

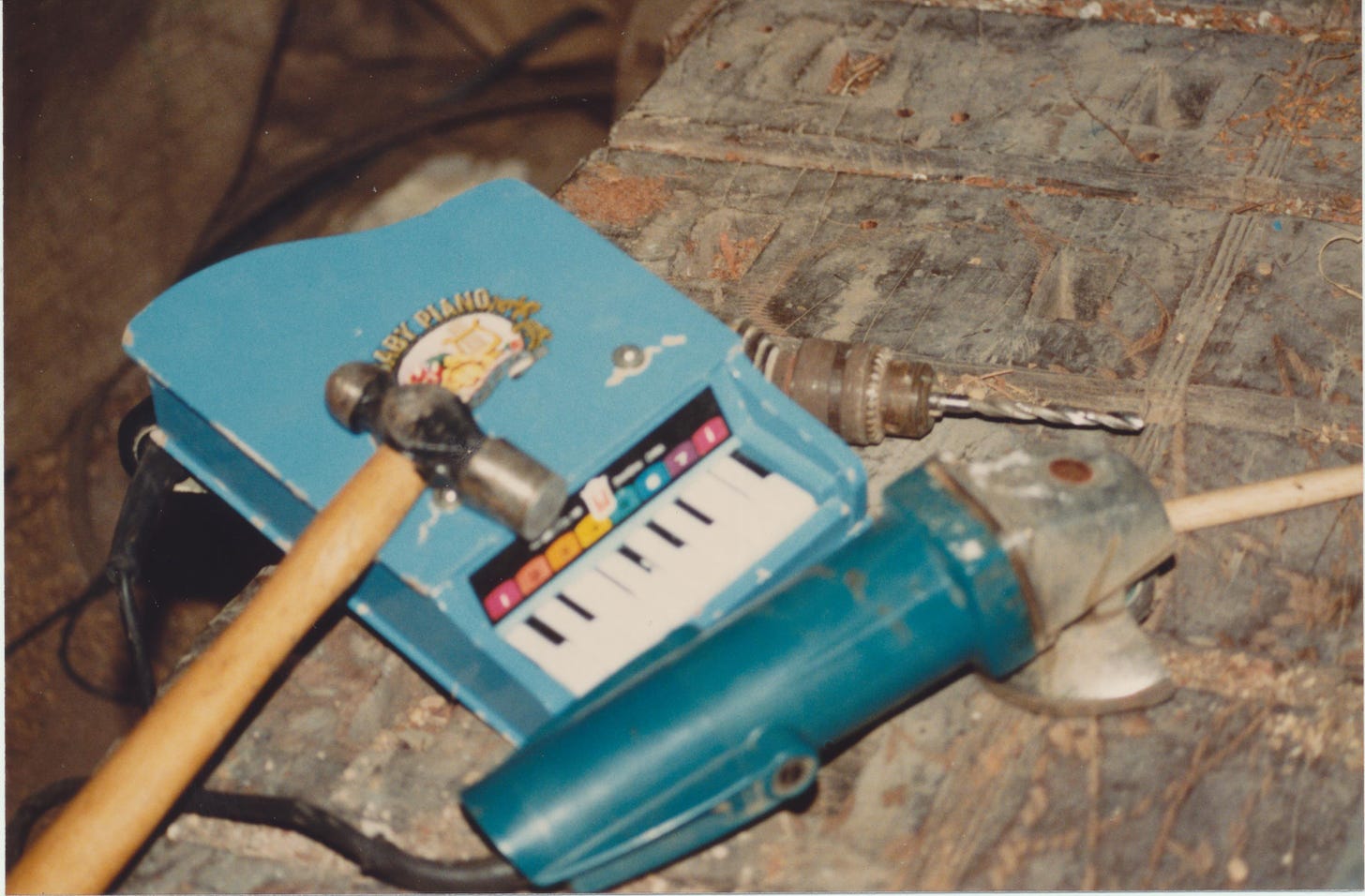

The first ever show was performed at the Man and Earth Gallery in a local area called Sheung Wan. The show itself lasted for no more than 10 minutes tops. It left a broken grinder (with pieces missing, presumably hit a member of the public?) in its wake, a guitar full of heavy indentations and had chunks removed (it must have been the grinder! Snapped arm / cracked pickups, all strings missing), a broken hammer, a large metal pipe (borrowed from the nearby construction site) which collapsed in the middle (did he really hit it that hard?) and a cloud of thick smog hanging over the entire gallery space suggested something terrible had occurred, and to top it all off, later the gallery would even discover a broken office chair.

Truth is Nerve wasn’t even around at the time. The witnesses of the show didn’t even want to talk about it, apart from one short review in the local music mag—that was it. Those were the days and that was the time, and doing something that never happened before might be something the Chinese general population found hard to fathom, even in the year 2020.

But a door was opened and someone called Dickson would take advantage of that. Sorry but I’ll have to start bad mouthing about that character, which I know too well I’m not supposed to do in this interview, but the truth needs to be known that Dickson has done a lot of damage and ripped off artists.

Firstly, Sound Factory’s existence was based on ripping off my personal contacts and financial partnership with its other director, Henry [Kwok]. The pair took off leaving me and my friend penniless, and set up Sound Factory about a year later. Could be the guilt? I then received an offer for the recording of Voluptuous Musick, though again seeing no artist fee nor sales revenue from them. To top it all up, they claimed the idea for the first international independent music festival as their own.

But by then I was pursuing my own way in the UK and thought nothing more about Sound Factory. Years later I’d heard that Dickson managed to carry on his boasts around China and many artists also fell victim to his scams. Henry lost his fortune and Sound Factory closed its door back in the ’90s.

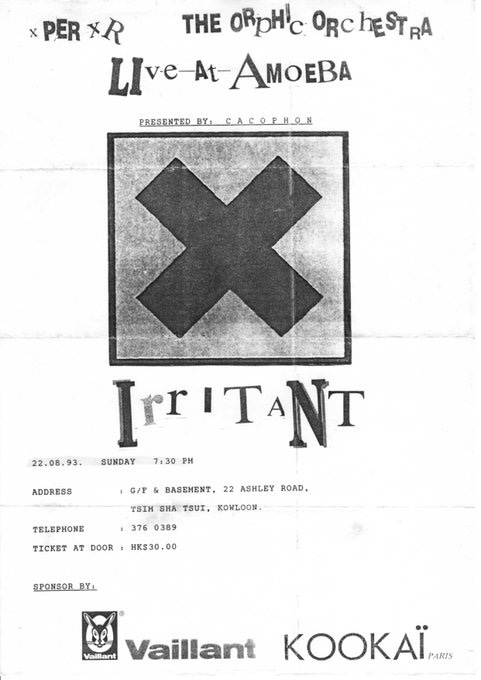

Yes you did some good research and nobody even remembers the show at Amoeba! That was a test run just before the show at the independent music festival a week later. The performance and exhibition at the Quart Society in comparison, was a more introspective show that reflected changes in the creative process at the time.

The thing about the olden days is that everything is a lone wolf operation, perhaps it was due to the kind of sound and visuals that I was into, that the more challenging, extreme end of the spectrum wasn’t a thing to be appreciated, even in the so-called alternative circle. Man and Earth and the Quart Society were about the only ones that allowed something quirky to happen. (Perhaps it’s true that they were about to close permanently and therefore had nothing to “lose”?)

There was however one contemporary dance group called the Zuni Icosahedron that seemed interested but I guess they were of a certain reputation and did not really want to risk losing their government grants by working with this wild kid coming out of nowhere… ironically, one of my releases, Entomb Vol.1, was made for one of their artist’s video piece… which never got to materialise.

You mentioned your first full-length CD, Voluptuous Musick, released on Dickson Dee’s Sound Factory label in 1992. Can you talk about that label and your relationship with Dickson Dee over the years? I get the sense that before this release, Xper.xr was more of a performance than a recording project, as many of the tracks on the CD were recorded at a live show in 1990. Would you say that's accurate?

Again, I can bitch about Dickson for another 10 years but truth is he should have learned his lesson by now… Oh wait, maybe not. I guess we have our differences but what’s important is art for art’s sake. When the heart is not in the right place, maybe [one] should just do something else? Stealing others’ ideas and pretending to be something he’s not won’t get very far… in some way that’s perhaps now an accurate description of his current status: the last I heard is that he’s burned all [his] bridges in the HK scene and almost used up all his lives in the mainland… there were threats to his dear life at one point as he’s been underpaying a lot of people.

Voluptuous Musick, while it may seem like a big mishap with bits of recorded sound jumbled up together, was in fact all recorded inside a rather kitted-out studio, though we did not use the designated recording rooms but ventured out into the toilets, building staircases, etc., and just wanted to break every rule in the book. That part was fun. The materials however, in retrospect, should have been better composed and edited.

In this same period you also published an arts magazine, Cacophon. What kind of content were you interested in curating or exploring with this magazine? What was your approach to writing about or documenting experimental music/sound in particular?

You impressed me very much with your research—again not many, even local fans in HK will remember that fanzine. It was a last-ditch attempt to revive the arts of communication through a published, materialised body of writings that captured what I’ve been exposed to and found on the way, much like a journal of discoveries in the world of everything alternative that I knew at the time. The people who I’ve met, artists I’ve spoken with, interviewed, etc. It was a single-minded project and only 60 copies were hand-printed from films; I didn’t manage to break even with the production costs as more and more inserts were made…

The fanzine follows the same journey from earlier on: it’s devoid of politics and anything practical, just pure appreciation for what art can be, breaking down categories and boundaries that separate. There were visual artists and photographers whom I admired that I found equally creative and even parallel to some of the musicians’ aesthetics that I appreciated deeply. I’d try to draw similarities in some cases, and be critical and despising on some that I believed were intellectual and artistic charlatans… all with extreme prejudice and I of course was totally personal about it!

The cover is a tool or tactic that’s popped up repeatedly throughout your discography, from your 1990 take on “Nothing Compares 2U” (I saw it mentioned in the liner notes to Voluptuous Musick but can’t find this recording anywhere?), to your 2006 pipa and cymbals versions of “No Limit” by 2 Unlimited and “I Feel For You” by Chaka Khan, to your 2020 cover of “My Sharona” by The Knack. What appeals to you about using references from pop music in the framing of your work? What goes into the selection process when you decide to “cover” or interpret a well-known tune?

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” someone said once. The phrase both affirms the death of creativity but at the same time challenges the very definition of originality: After all, there are only 7 musical notes and a 7-colour spectrum in this dimension, yet we claim copyrights to the arrangements of these ingredients and sue the arse off someone who arranges them in a similar way, when none of us in fact had created anything original in principle. I guess I did really have a problem with that but then again, copying the copies still seem like a pretty good idea!

The instant recognisability of “hits” is a sure way to get to people, and what’s better than altering their fond memories by having a real go at it, embarrassing everyone in the process? Pop culture, like it or not, will always be the most successful mode of communication—it has its own syntax, vocabs and terminologies that are driven by fashion and trends, also it has little morality and is not afraid to betray itself in the most spectacular way, much like humanity today!

But I’m glad to say that some form of sincerity has been kept alive. Most of the songs covered were actually something that speaks more profoundly to myself at least. Well, then there’s those tracks that said nothing at all, as a pure ironic statement even. They usually are there to… simply embarrass the crap out of us all…

Can you talk about the influence of rave music and culture on your practice as both a musician and organizer/venue operator? You lived in London from 1990-1993 and 2000-2012, is that right? And you spent some time in NYC in between? How did your time in these cities influence your perspective on or approach to rave/club culture?

I did have my brush with NYC before I was even in London—that was very early on and I was too young to even appreciate what the NY arts scene had to offer. I was almost forced to go study by my parents—and who can blame them, especially since I’d managed to fail my exams in every subject in school. But I naturally chose [music] and before you knew it, 25 years were gone. More accurately, I went to London in late ’89, then took a sabbatical to Paris from late ’94 to ’96, shipped myself back to London, all the way until returning to Hong Kong in late 2013 to start the CIA.

One of the major turning points of industrial music was that it morphed into techno, house and other electronic dance categories, perhaps by design, or was it out of desperation? In any case, groups like S.P.K., Psychic TV, Chris and Cosey, Coil, Laibach, and others had their fair share in it. After all, dance music in general is extremely effective in that it provokes an almost immediate emotional and physical response, it can instantly manufacture a state of coexistence and bounding towards certain tastes and ideologies. In short, the perfect tool for manipulation of the masses by the powers that be.

It’s nevertheless a useful element in music that it can help create an agreeable element no matter how terrible the actual sound is! Seeing and hearing the different evolution of dance music in Europe is something of a journey itself. I in fact have a natural aversion to dance around. From the rise of house and the black notes, to the techno and break beats, then came the hardest core of gabba, to the illbient, darkwave, EDM and then dub and godknowswhat next, one can see the same principle being employed over and over again: the aim is to produce an excuse for an out-of-body experience.

The influence of rave, industrial, and breakbeat are pretty evident throughout your discography. I also sense a deep influence from folk rock—the acoustic guitar pops up occasionally in your compositions, as on one of my favorite albums of yours, Because I’m Worth It. Can you talk about your approach to combining pop, techno/electronica, noise & industrial, and folk/rock in your work (sometimes all in one track)?

Golden Wonder was the one album that I went mad with gabba and bad dance beats, though it turned out being quite well appreciated, especially in France at the time. The joke was then firmly on me. To make things worse, one just had to pick up that acoustic guitar and strum it to the heart. A compilation called Love is This was the test ground for Because I’m Worth It—glad you like it!

It took some serious practices to brush up the old forgotten skill before going for gold. Because I’m Worth It was simply a no-holds-barred pure indulgence of “keep rubbing salt into the wound until the nerves are fried.” Once I understood that the “Hotel California” guitar solo was absolutely necessary for every song, it no longer mattered if the chords, rhythm, or tempo matched. You know you want it.

I think since Golden Wonder, it was apparent to me that breaking down all the boundaries of styles was important if the art of music-making is to survive the next decade… that it’ll be the only option left after Cage and co. declared war on sounds.

In 2012 you opened CIA, which was a seminal and kind of legendarily underground HK experimental arts venue that ran for three years. Given your decades of experience as an artist & cultural producer via various labels and publications, and your extensive experience overseas, what was your driving mission in establishing CIA? What were the venue’s greatest successes, and what were some of the most challenging or frustrating parts of running it?

CIA was my payback to the HK arts and music scene. It was unfinished business. When I left HK in the late 80s, there was a sense of defeat because the culture and climate back then did not allow something different to coexist, and everything was down to commerce. Europe, and the UK however, was somehow catching up to that situation for artists around the time from 2009, where most independent labels were swallowed up by major corporations and musician-run record shops could no longer help promote indie artists with their releases; the window displays were being bought by Sony and Warner. So that was a cue for me to return to Hong Kong and right some wrongs.

The premise is simple: Just do what I believe is worth doing. It did not make much financial sense but given the entirely self-financed and next-to-nothing budget, CIA did manage a few projects that proved it could be done—we managed to put acts and shows on where literally no one else could or would do! We have worked with artists and musicians that I can only dream of sitting with in London all those long years ago—these are people that I admired and respected enormously. Knowing them on a personal level and becoming friends was simply beyond a dream.

However, in the darkest hours, I also got to see that my longtime friends turned against the cause and acted hostile towards the end. So much so that I lost the revenue from an agreement and CIA had to close its door as a result. Other than that, I’m glad to report there’s no regret whatsoever.

You may have answered this in the previous question, but I want to ask about two CIA events in particular. In 2014 you hosted an event for performance artist Hermann Nitsch, famous for his Aktions including the ritual dismemberment of animals and other gore. A few months before that you hosted the infamous Slovenien industrial band Laibach, who’d go on to perform in Pyongyang the following year. I was trying to help you set up a Beijing show for Laibach in 2015 and there was a sponsor on board, but that fell through... Nitsch’s art is too extreme to even entertain the possibility of hosting an event for him in mainland China in my opinion.

I want to ask you how these two events came together—did you contact the artists? How or why did you select them to bring to Hong Kong? Do you think you could do these shows in 2020 Hong Kong? (I saw that Laibach was scheduled to perform in HK on January 22 of this year, one day before Wuhan went on lockdown in the initial Covid outbreak. Did this show happen?)

First of all—yes, I thought your name sounded familiar and my apologies for not pointing it out earlier! And I still want to thank you for your help with organising Laibach in Beijing even though it all went south…. it’s just business I guess. But I was prepared to put in all my own money to make it happen, just that Guitar China seemed to not appreciate it enough to stick to their end of the agreement…

But [putting on] Nitsch was my childhood fantasy. I had the idea of showing his work long ago, if only one day I’d have a space of my own—and I did. Back in London in the early 90s, I was in touch with him and exchanged some ideas, though it took 20 odd years to materialise. I flew to Vienna to meet with him just a weeks after Laibach left Hong Kong in 2014 and it was great to meet a hero at last—he did not remember me writing to him at all!

Funnier still is that Laibach had their story with Nitsch as well and they hung out in Ljubljana when Nitsch performed his Aktion there—one of Laibach’s singles did use Nitsch’s painting as the background it turned out. So it was a small world after all.

That’s it. They are all part of my tiny universe, and it’s an honour if I can one day work with them somehow—artistically it’s not compatible, but at least to host their own shows will be the 2nd best thing to happen. Also, precisely because they are NOT supposed to come to Hong Kong, and these shows are NOT supposed to happen. That, is perhaps the reason of all reasons…

I also had the opportunity to go to North Korea with Laibach in 2015 and be part of the organisation, which I’m extremely honoured. Then came the show in January this year—we had it by the skin of our teeth—it was a short-notice gig and logistics were insanely tight, plus the protests earlier, then came the scamdemic*—but again for all the wrong reasons, the show was a huge success (in my opinion, though we still managed to make a heavy loss) with crowds coming out of nowhere to see Laibach play.

*EDITOR’S NOTE: Although we felt it was important to present the artist’s quote unedited and in full, as a publication we deemed it ethically necessary to remind readers that the scientific consensus overwhelmingly supports the facts that 1) the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a real threat to human life, likely resulting in long-term disability even for survivors, and not a hoax, 2) that it is the result of zoonotic transmission, likely via wildlife trafficking, and not of laboratory origin, and 3) that the spread of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic is strongly mitigated by social distancing measures, consistent mask usage, and extensive testing with contact tracing. These measures have saved millions of lives, and their continuation is essential to save millions more.

As of this writing, there have been over 68,500,000 million cases and over 1,500,000 million deaths worldwide. Although non-scientists, including artists, may vary in their views on these issues, it is critical to take into account the role of governmental leadership in setting forth guidelines, combating misinformation surrounding the pandemic, and providing resources to support communities who have been impacted both directly and indirectly. The degree to which governments have succeeded or failed in these tasks strongly factors into how individuals respond to such an unprecedented crisis, especially given the complex relationships many artists have with their nation’s governments.

Last November/December, you gave a performance called “The Body Electric” at Hong Kong arts space Empty Gallery. This followed half a year of major street protests connected to the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement that began in March 2019. The relationship between Hong Kong and Beijing has only gotten more tense with recent developments like the Hong Kong security law passed in June 2020. How do you think Beijing's increasingly tight grip on Hong Kong sovereignty is being processed by artists in the city? How have recent projects of yours—like The Body Electric and your latest recording, “Mein Corona”—engaged with recent social or political events in the city?

Thanks to the Empty Gallery, I was given a chance to address the “aftermath” of the protests in HK, through an earlier proposed idea of using the Rife healing frequencies for a public event in an attempt to restore physical as well as spiritual health. I know how this must sound. Without getting all political about it, we’re most concerned with the devastating effects from what had happened during the protest—the hopelessness and general hysteria, unhealthy daily hostility against anything and anyone. It is my belief, in short, that the people of HK had been manipulated by those behind the scenes and divided intentionally. We’ve been played. There’s no black shirts vs. white shirts or yellow vs. blue ribbons—it’s naïve to even think such simplicity exists.

So we revisited the idea of performing the Rife frequencies with Pan Sonic but with the passing of Mika [Vainio], Ilpo [Väisänen] has been keeping himself away from doing any work that reminds him of the collaboration with Mika. Fortunately for us, Dirk [Dresselhaus] and Ilpo still operate under die ANGEL and we found a way (after some serious discussions) to make this show happen. And for me personally, it’s a wonderful opportunity to be able to work with two such legendary artists of our time. The show received a huge turnout and the gallery floor was packed from end to end, though some experienced strong physical reactions from the frequencies—Rife wasn’t joking with his plasma energy.

In terms of artists in HK, they naturally were reacting to the situation through their works, in support to either “side.” Though I do think art should be apolitical—to have a purpose or an agenda would render the very concept of art to be “impure,” therefore contradicting the very idea of art. There were moments in history where artists “ridiculed” politics and use irony to attempt to short-circuit the tyranny, and it’s always refreshing to receive a different perspective through art, for it helps to bring change and bridge new connections when it’s needed most. It’s one of my favourite parables to point out that some of the best arts to ever grace the face of the earth came out at the most terrible of times.

“Mein Corona” follows this logic and manifested itself through the urgency of the situation, to amplify the fear mongering, the hysterias, the losing control of common sense and the blind obedience of the masses to authority without question, throwing it all back at their faces with a message saying, “I’m not buying any of it.”**

**Please refer to the previous Editor’s Note.

“Mein Corona” is your first official release since 2006, and was put out by the label arm of Empty Gallery. It sounds to my ear like a comprehensive synopsis of your musical output to date. It’s high-tempo, high-frequency, verbally caustic, very loosely based on a well-worn pop tune (The Knack’s 1979 original version of “My Sharona”). It incorporates what sounds like a digital version of traditional instruments (suona?), but ultimately coheres into an aggressive sound collage divorced from all of these referents. What prompted you to release new music after a 14-year gap? Has your approach to composition changed at all in that time?

Truth is I thought I’d already hung up the mic all those years ago, as I was rather discouraged from working musically anymore, after experiencing the dark age of creativity in the UK with my last album. But desperate times do call for desperate music, so there I was, answering that call. From the word “go” we knew it had to be absolutely insane—only that degree of insanity can match the absurdity of the biggest fraud in human history.***

Though I guess deep down the drive was almost the same—it was the same urge to “do something” about what is (not) happening as it was in the very beginning, only this time having the benefits of the experiences from the whole journey to the west and back.

***Again, please refer to the previous Editor’s Note.

I saw that all proceeds from the sale of “Mein Corona” will be matched by Empty Editions and donated to the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention at the University of Hong Kong. Why did you select this institution to receive the proceeds?

This was a little embarrassing, as my original proposal was a convoluted way of launching a law suit against the chief executive of HK with the proceeds… I guess it proved to be a little too much and Empty Gallery went to the suicide prevention route after some deliberations…

What’s your view of the Hong Kong noise/experimental music scene today? CIA closed five years ago, but there are some spaces and groups preserving cultural space in the underground, like Nerve’s venue Twenty Alpha and Hong Kong Community Radio. What's your opinion of the state of Hong Kong's experimental music scene today? What are your hopes or concerns for its future?

Please refer this to my earlier damning report on the HK scene… I managed quite successfully to piss off about 99% of everyone attended that symposium on HK independent music production.

Thank you for reading our special midweek issue of Tone Glow. Please try not to piss everyone off.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.