Tone Glow 042: Graham Lambkin

An interview with Graham Lambkin + an exclusive mix + reviews of albums and singles from throughout his discography

Graham Lambkin

Graham Lambkin is a multidisciplinary artist and publisher whose work embraces audio, visual, and text-based concerns. Lambkin first came to prominence in the early ’90s through the formation of his amateur music group The Shadow Ring, who fused a D.I.Y. post-punk aesthetic with folk music, cracked electronics, and surreal wordplay, to create a unique hybrid sound that set it apart from its peers, and continues to exert an influence today.

After the dissolution of The Shadow Ring, Lambkin embarked on a series of striking and highly original solo releases, including the critically acclaimed Salmon Run, Amateur Doubles, and Community, as well as undertaking a string of collaborative projects with the likes of Joe McPhee, Keith Rowe, Moniek Darge, Jason Lescalleet, Michael Pisaro, and most recently Áine O’Dwyer. An LP box set of his major solo records is up for pre-order via Blank Forms. A box set of Shadow Ring LPs is forthcoming. Joshua Minsoo Kim talked with Lambkin November 18th, 2020 via WhatsApp to discuss his childhood, The Shadow Ring, his visual art, his solo work, and more.

A note about this interview: After this interview you will find a mix that Graham Lambkin has made featuring songs (including unreleased ones) which relate to things discussed here. Please listen while reading.

Joshua Minsoo Kim: Hello, hello! How are you Graham?

Graham Lambkin: Hey! Good, man. How are you doing?

I’m good. Just finished up work and now I’m just here.

And your dog has been sated? [Editor’s note: I told Lambkin that I needed to push the interview back a few minutes because one of my dogs needed to pee].

Yes! My dog is perfect now.

What do you have?

I actually have two dogs. I have a lhasa apso, her name is Charlie. And I have a maltese and his name is Rocketship. It’s Rocky for short—my cousin got Rocky’s brother, and that dog’s name is Rambo. Two Sylvester Stallone characters.

When’s Demolition Man joining the family? (laughter).

Sometime soon, hopefully. Have you been having a good day?

Yeah, I’ve been good.

What have you been up to?

I just got finished putting that Call Back the Giants Bandcamp page together for Tim [Goss], so I just went back after a couple days and checked all the links and made sure they were all working for him.

Was really happy to see that. You know what’s on my mind right now? Earlier this year you said that I was “tireless” because I do so many interviews (Lambkin laughs hysterically). And I’ve done a ton this year.

Yes.

And you’re probably gonna be one of the last ones I do for 2020. Anyways, something I kept thinking about today was that I hadn’t kept up with films this year. I like to keep up with that, especially avant-garde shorts, but I was so busy with music and interviewing people that I didn’t have time for it. A part of me was just like, man, you can only do so much in life.

When I think about your career, you’ve done a lot of different things. So I was wondering: Do you ever have this sadness, or just this understanding and acceptance, that you can’t do everything you want to do? Do you ever have those feelings? And if so, how do you go about managing them?

I think there’s a distinction to be made between feeling like you can’t do everything—that realization that may or may not come over you—and a need to hone in on one specific area. That’s more how I’d have it. I would hate to imagine that there was a point in my career, as you put it, where doors were closing. I try not to think that way, and I don’t think that way; I never have thought that way. I think that’s one of the fundamentals of my way of thinking about taking life and processing it into art; I always enjoy that equation of ambition over ability. I think if that’s present and true in the project, then it validates it no matter what the focus is on.

Can you speak on that more? With ambition over ability, how do you see that playing out in your own life?

I suppose the first example was Darren [Harris] and I deciding way back in ’91 that, yes, there’s no reason we can’t launch ourselves into a music career (laughter), ignoring the fact that we had no instruments or musical training. We were only fans of music but somehow that seemed a strong enough reason to jump in and see what happens. This was based on enthusiasm, based on the types of things that were in the air that we could identify, at least in part. A lot of different factors influence it but it was the realization of that—that it’s not necessary to be fully aware of the laws of something in order for you to have a go.

So you must have been like 18?

Yes, 18. Darren and I actually had an earlier example of this kind of tomfoolery. At school. We had to come up with some kind of business vehicle within your means as a schoolchild. It was part of the school’s Works Enterprise week. Lots of people came up with different solutions: washing cars, taking neighbors dogs out...

We decided that we were gonna put together a cassette of songs and sell it alongside what we termed “psychedelic fruitcakes” as they were advertised at the time. These were sponge cakes with ribbons of food color running through them and you had to imagine it was some psychedelic odyssey you were about to embark on when your teeth sunk through the sponge. It was accompanied by this tape of us knocking around called The Heart Tower Singers, which I have almost no memory of besides what I’ve just told you. I don’t have a copy of it. We only sold two copies (laughter). It wasn’t a tremendous success, but it was the start of something.

Can you paint a picture for me of what it was like for you growing up? Were you close with your family.

Not a tremendously large family but yeah, close relations with my parents and my sister. I was definitely a child who was living in a fantasy world.

How so?

I wasn’t very outgoing or interested in communal things. Sports. Socializing. I was much happier with my own company. I spent many hours drawing and playing in the garden.

Was drawing the first artform that you got into?

Oh for sure. My dad used to work at an automobile manufacturing factory called Dormobile and he would bring these paper sheets home. They showed a breakdown of the different parts of cars that would be assembled to complete the vehicle, but on the other side—the more important of this story—the sheets were blank. They would come in different colors in reference to the vehicle that they were connected to. So I would have access to white paper and green, blue, pink on occasion—that was the really exotic draw. These were invaluable.

Were you trying to emulate artists or illustrators at all at the time?

None of that. Once I started school, I fell in with a friend of mine—Howard ‘Bloodmouse’ Lester—who was in and out of The Shadow Ring in various ways. We kind of formed an art club between us and we would work on these drawings together and would meet up after school and have this saga play out over pages and pages on these automobile sheets.

How old were you when you started this club?

I met Howard when I was five, so it was between the ages of five and twelve. It was called TEZMON (laughs).

What does that name mean?

It doesn’t have a meaning (laughter). It was just phonetically attractive.

What was it like being in that club? What was it like being with Howard?

Howard was… I guess you could call him a colorful character. He was very important to me as a friend and as someone who influenced my thinking. One of his two older sisters, Caroline, had—what seemed to me at the time—a mature and exotic record collection. So it was always a learning experience to go over to Howard’s to work on our art and also to interact with Caroline and listen to what she was playing through her bedroom wall. I was curious and would ask questions. It was a very rich experience.

Do you remember any records you got into because of Caroline?

It’s all fairly route stuff. Syd’s Pink Floyd. Bowie. Tyrannosaurus Rex. All this kind of stuff that you wouldn’t necessarily run into on the Top 40. I’m trying to think of what else she had (pauses). Just things like that… underground UK things.

So that’s between five and twelve. You eventually get into high school and you meet Darren. Do you remember your first impression of him? Were you in the same class together?

I met Darren and Tim at the same time, on the same day.

The same day? Wow, how did that happen?

Umm… (laughs). I swore that I wasn’t gonna go down this road, talking about (laughs) memories and shit (laughter).

Why’d you promise yourself you wouldn’t do that?

I mean, the interviews I read from you, you always get them to talk about why they love their sister or their first memory of the snow or something like that (laughter). It’s like, “What the fuck is this guy doing?” And now here I am, back at Amanda Langford’s 13th birthday party (laughter).

Tell me about her birthday party!

She was like 12 or 13, I remember that. It was some school party where the parents were stupid enough to let the kids have free rein over their house for the night. All and sundry were invited over and all hell breaks loose, but that’s when I met Darren and Tim (laughs).

Did you all just click right away? Or was it like, okay these are some other boys and I’m just talking with them.

They were both into music and I think that’s how we connected. I knew Darren was into music, as I’d heard—there was talk going around the school. And I heard Tim was too so we found some common ground in that. We weren’t in any shared classes or anything like that.

Did you three often hang out together after school?

There’s photos all in this Shadow Ring box set that’s coming out. There’s photos of us in the photo booth in Boots the chemist in 1985 or so. We were crammed in with our strip of four black-and-white pictures. All this crap. It’s all documented (laughter).

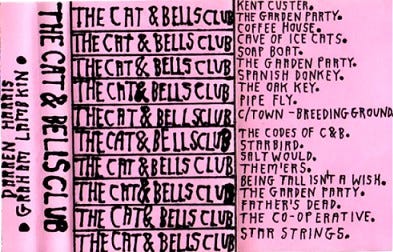

I think what you shared earlier about you and Darren creating music was super interesting. You had The Cat & Bells Club. What was the timeline between making music together, releasing that cassette and then eventually having Tim as part of The Shadow Ring later on?

Well Tim actually auditioned to be part of The Cat & Bells Club. We were looking for a third member to flesh out the sound and he was one of two people who applied.

And he didn’t make it?!

The other kid who showed up brought a guitar and ran through some blues licks. I don’t think he understood what our agenda was and kind of withdrew his application (laughter).

The fact you even had auditions indicates that you had a vision of some sort. Were there specific rules or ideas that you two told each other that you wanted to follow? Or was it more like, okay we’ll do whatever and record it.

It was just mindless naivety, pure and simple. Just a need for some kind of self-expression with almost no tools in our toolkit. But it was building something up from nothing at the same time. We had things we were influenced by and perhaps tried to emulate in our own way. It wasn’t completely out of leftfield but in terms of an agenda or a goal in mind specifically with where we wanted to be or who we were: no, it was just in the moment.

When The Shadow Ring started up, how come it wasn’t just The Cat & Bells Club again? I’m curious why it wasn’t The Shadow Ring at the point that Tim came around.

Well, the answer to that is just the advent of the 4-track. Darren and I were able to double track ourselves and we just thought, problem solved. And we had some friends who would occasionally come and help out and it was just Darren and I until it got to the point that we got live invitations and offers to do things. Suddenly, we realized that we couldn’t accept any of them and sound the way we did on the vinyl.

We went to the States for the first time in ’95 as a duo and did some shows. We were supplemented on stage with this band called Coffee. The band that was advertised as being The Shadow Ring on that tour really wasn’t. We didn’t want to get in that position again so Tim was still on the scene and had this new keyboard he brought around. As our music as The Shadow Ring was starting to extrapolate and as we were losing interest in doing sort of songs—to call them songs is generous, it was these condensed things with structure, I don’t know what you’d call them—but it made a lot more sense for Tim to come back on with what he was currently displaying. It made sense. Does that make sense to you as a listener? Or does it seem erratic to go from this duo with just acoustic guitars to adding a Moog.

I think it’s normal. I think adding electronics of any kind is sort of a natural progression that bands do regardless of genre.

Can I ask you, when did you first hear The Shadow Ring?

Well, I’m 28. I heard The Shadow Ring for the first time in like 2012.

Ah, so we were all wrapped up by that point.

Oh yeah, for sure. By the time that Shadow Ring’s last LP came out I was 13. I was definitely not familiar with that music back then.

That would not have been on your Christmas list (laughter).

Unfortunately not, no. There are a lot of Shadow Ring records, and obviously when Tim comes on that’s huge, but is there a specific moment or moments within the Shadow Ring’s career that you felt were super important to you and the way you viewed art? Was there a breakthrough for you?

Yeah, when we recorded Lighthouse. That was the record we were meant to make.

Why?

Everything up until that point had been about growth and development and making us a stronger, more convincing band that was muscular enough to recreate things live and to be fully-formed. After that moment had come and gone, I think it dawned on all of us that we were being disingenuous to the kernel of what made this thing great, which is the amateurish quality of it, the acceptance or the unavoidance of error, the humor. To try and hammer that out and become a more solid-state group was really a lie to ourselves. We then began this process of quite consciously dismantling everything. Taking the songs apart.

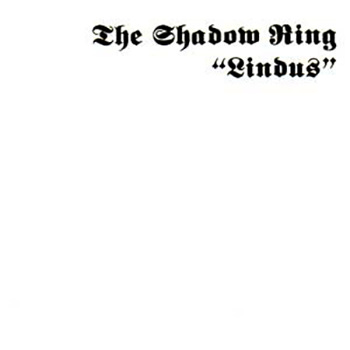

If we’re going to recognize that these things are songs—let’s agree that they’re songs—let’s reverse-engineer them and do as many things to the template of a song where it still retains its identity. Where are its wounds? With Lighthouse, Lindus, and I’m Some Songs, they were so flattened out that if your definition of song is a sonic element and some kind of human voice in some battered form, then okay that’s a song. But beyond that, there’s nothing that really qualifies it. It was one of the reasons we stopped the group.

The other was that it was a 10 year period and that seemed really attractive to me—it always has—to announce a conclusion with the same confidence that you announce an inception. There’s nothing worse than, “What happened to _______?” It’s nice to have death confirmed. It made sense on those two levels and it also acted as a baton change to start a solo record, which was happening concurrently with those last Shadow Ring records. It just takes things off in a different direction.

What do you feel like you brought to The Shadow Ring that Darren and Tim didn’t? And what do you think Darren and Tim brought that the others couldn’t?

Perhaps I brought the drive that got these things happening. And, to some extent, I was in charge of the demolition of the group. Although, of course, I’m not suggesting that they were completely under my command, but they understood what I wanted of them and I left it to them to take the pieces apart in a way they wanted to do it.

Darren had a bravery and a willingness to step into a world which is completely alien and uncomfortable to him, and to find some pleasure in that. And he got to enjoy the sound of his own voice—he’s really proud of those records. I mean, he doesn’t see them as a source of embarrassment—they’re not hidden under the bed—but he recognized quite nobly that he had made his point and that he didn’t need to get involved in the music world beyond that. He never has. He’s never even been curious.

Tim’s strengths really reveal themselves in hindsight when you listen to a project like Call Back the Giants, how incredible that project is. And then you can start to hear the germs of Call Back the Giants in things like Lindus. I think in the Wax-Work Echoes record he’s just a texture, but his identity starts to form in the subsequent releases. I think by the point of Lindus he’s really strong, but you still have no real appreciation for how much stronger he was gonna become.

When you listen to the track “The Rising,” that’s an incredible piece of music as far as I’m concerned. The first Call Back the Giants 7-inch… when he told me he was making music again and gave me that I was like, “Oh this is going out as a 7-inch. It’s one of the best things I’ve ever heard.” And I still think it is. That 7-inch—“Call Back the Giants” and “Ms. Maris Lopez”—I’d put that against anything. That’s the killer 7-inch. Him and Chloe, who at the time was 10. What a fucking weird project. Tim from The Shadow Ring and his 10-year-old step daughter making these lo-fi, apocalyptic, electronic gloomy 7-inches. That’s not what most 10-year-olds are doing.

I forget, how many kids do you have?

I have two sons.

Have you wanted to record with them in a similar way?

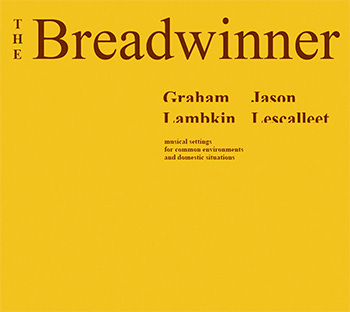

They’re on loads of records. My oldest son Oliver is on The Breadwinner, he’s on the thing with Taku [The Whistler], he’s on C05, he’s on Amateur Doubles, he’s on the Batcave record. I mean, he’s on more of my bloody records than I am (laughter). Tom is on The Whistler as well, and Amateur Doubles. I mean, if they’re around me when I’m making a record, then, yeah. They’re on Community. They’re on all of them probably. They’re probably on records I don’t even know I’ve made (laughter).

Do they make music themselves outside of the things you’ve recorded?

Joe [McPhee] used to give Tom violin lessons. He used to come by to do that. Other than what they’ve had to do at school, no; they’re just listeners.

I was curious because when Live in the Batcave came out last year, it was the first time Oliver’s name was there.

That could be true. It was his first so-called music credit but he’s credited on sleeves where he’s involved in the record.

With The Shadow Ring, you said that you had come to a point where the project had been finished and you had reached this culmination of what you wanted to do. What still needed to be done, then, with your solo work?

By flattening the landscape of The Shadow Ring, it gave me the experience of that group for 10 years, but there were things I wanted to do that didn’t make sense within a group. These are very much solo, personal explorations that I’m not… (pauses). They’re almost selfish. They’re at the expense of everyone else in terms of, I have no interest in someone else’s opinion. It was personal to me.

I didn’t wanna have Tim and Darren involved in a record where they weren’t allowed their own voice; it wouldn’t have been a democratic process anymore. Although they’re on Poem (For Voice & Tape), I think it’s unfair to call it a Shadow Ring record because they were recorded and then I made of it what I wanted, and they really had no say in it beyond that. Does that make sense?

Yeah, it does. What was the first satisfying moment you had in creating music for your solo records? The first time you had an idea that you thought only would’ve worked solo and the recording came out and confirmed for you that this was the right path.

It was Poem, the first one.

With that, what made you feel like this was something you felt was right and something worth exploring? What were the selfish ideas you had that you wanted to explore?

Removing the artifice and polish, getting down to something raw and feral. No longer a need for formality or words, just phonetic deconstruction, and revealing something new behind that. It was an eye-opener.

Were there artists across any medium who you felt were doing things like this that you were looking to in order to make your own music?

Not really a direct influence but one that came up that people don’t often talk about is Whitehouse. I really like some of the earlier records. Scott [Foust] was a big fan of them as well. By that time I was hanging out with Scott and listening to things like Great White Death—how simplistic those records are, or seemed to be. The economy of means and the power that delivers was attractive.

It didn’t seem beyond the realm of possibility that this recording of Tim, reduced down to a molasses, against this patchwork of fairly motionless synth and water could also deliver something greater than the sum of its parts.

Do you revisit your old records?

I don’t usually but I’ve been doing a lot of it this last year putting this Solos box together. I’ve been back in the trenches with these old things.

Are there any things you realized about these records while revisiting them that you didn’t recognize when they were released?

They’ve been varnished by time. My relationship with them is different but I think that’s happened throughout my career and that it happens to everybody. There’s a closeness to the thing you’ve just made and it’s unbearable; you have to put it away. There’s something unusual about someone who spends their entire listening time in self-celebration. I don’t wanna know about it for a long time but then I’ll go back and take a peek.

The mistakes you make on earlier records—and perhaps they’re not mistakes, but things you realize in hindsight you could’ve done better—no longer embarrass you when you see them as part of a chain of evolution. I think that’s a healthy way to be about it but it takes a long time, at least for me, to get there. And I’ll say the currency of my music is rife with potential embarrassments. It’s personal to me so I understand it better than anybody else.

I know you might not have one but is there a specific example of something that you thought could’ve been better on any of these records but in hindsight you see a throughline between that point and where you are today.

I think there are parts of that Footprint cassette I wish I could go back and change because it’s just too badly recorded and some of the ideas outstay their welcome. We [Graham Lambkin and Darren Harris] did this piece where we went into a local DIY store and played with their doorbell display and then overdubbed it and mixed the tapes and mangled everything up. At the time we thought it was some kind of noise opus but listening back, it’s an exercise in extravagance. Moments like that come up and you often can’t do anything about it unless you’re no longer true to the course you’ve taken. You learn to live with it.

Where do you want to be five years from now? How do you feel like you’ve evolved and where do you still want to go?

(laughs). Where do I wanna be in five years? I wanna open up a coffee shop in the Canary Islands (laughter). A call was coming through and beeped while you were talking so I didn’t actually hear everything you said.

Well let’s talk about this idea of evolution. Let’s say in the past ten years, are there things you feel like you have a stronger handle on today, and what throughout the past ten years has helped you get to this point? Feel free to take your time.

I want to give you an honest answer. It loops back a little bit to one of the first things you asked me, and it contradicts it. My answer is that you start to realize that you can’t do it all (laughter) and you do have to make choices and I’ve been doing a lot of that. I’ve been focusing a lot of my time in the past three years on visual art and art archiving. Or finalizing existing projects like the thing with Bill Nace [The Dishwashers]. There are little things here and there but it’s mainly just visual work. I have made about 60 hours of audio recordings but they’re all just talking, there’s no composition to them at all.

What do you feel like you get out of your visual art that you know that you can’t get out of music?

That I don’t have to think about it for it to be a success. The more I think about the visual work as it’s progressing and forming, the more I realize it’s going the wrong way. Now obviously there are exceptions to that when I start to understand what I’m doing, but once I’m on that road and it’s not going on autopilot, I’m probably going the wrong way.

With the sound work, there’s an incredible amount of thought that goes into it and it’s a constant. There are times when you have to walk away from it, let things rest, and come back and hear things again. It’s a much more intense experience for me to critically make these sound works and be able to validate those because it’s a whole other process of thinking. Visual work for me is like being asleep.

Oh, wow. It’s so interesting that the music is something you think deeply about while the visual art isn’t. I guess that’s how you get to removing the artifice; it’s not a thing you just do. What’s the most challenging time you’ve had with any of your sound works? What made you lose your mind?

(laughs). You wouldn’t know it because it never got to the point of release. I’ve had lots of projects where I’ve wrestled with them and we’ve had terrible times together and they’ve never made it through. Anything that you would know about has been fairly harmonious. It might have taken a while to understand each other, but it always happened eventually. I have projects I started and had early drafts of records I canceled out.

I made a record with that guy from Squirrel Nut Zippers, Don [Raleigh], when I was living in Miami. We made a record together and handed it into Scott [Foust] to release on Swill Radio. It never happened in the end because I pulled it. There’s all sorts of weird stuff. Obscure things that are sitting in the shadows that never really had their day.

Of all the people you’ve collaborated with, who do you feel like you instantly connected with and were on the same page? I’m talking after The Shadow Ring.

This is kind of a wet response but honestly all of them because one of the key requirements for me if I’m working with someone is not what they’ve done musically or what they sound like. It’s whether I like them as people and we get on. That’s absolutely crucial. If there’s any kind of uncertainty or animosity with someone, how can you possibly enter into something as all-encompassing and emotionally driven as artmaking? I have to have a good personal relationship with a collaborator-to-be.

It’s important because you have to be able to tell someone—and you have to be able to be told—that things aren’t going well. People get really prickly when their ideas are changed—all these kinds of things can happen. How can that be a productive and nourishing environment to work in? I have to be good friends with the person first, you see?

With all these records, then, were you first friends with these artists before you made a record with them?

Yeah. Well, maybe not Taku [Unami], just because of where we are geographically. We’d corresponded before and I may have even met him once before. But Joe, you know, I’d see him all the time. And for all the others, it’s true for those too.

I loved what you said earlier about how Darren was comfortable with going into these uncomfortable spaces, or that he was willing to be uncomfortable—

For the good of the work.

Yes. I think being uncomfortable is such a difficult but important thing anyone can do, not even with art but just in general. If art allows for those opportunities it’s such a beautiful thing. So I wanted to ask, what’s the most uncomfortable you’ve ever had to be for your art?

(laughs). Probably when we first started, revealing ourselves in a local music community which was very unforgiving for anything that wasn’t garage rock or cover bands. That was uncomfortable. We were kind of waking up in the enemy’s garden and not being sure how to get beyond that point. Being somewhat known about that we were doing this music—so-called music—and being asked to perform… the whole thing was uncomfortable. It was nice to get out of that fairly quickly and enjoy distribution. A lot of these groups only sold records at their local shows so once we hooked up with distribution we were able to get our message out beyond that point. It didn’t feel so much like we were howling into a void.

Do you generally feel confident about the ideas you have now?

I couldn’t care less anymore what anyone thought about it. If I like it, it’s good enough. And if I don’t like it, you won’t know about it.

I wanted to ask about you running Kye. I remember the day you shut it down and it echoes what you said earlier about wanting to end The Shadow Ring. You ended Kye at 50 records, another attractive number.

(laughs hysterically). Yeah.

It’s been a few years since the operation stopped. Can you share your experiences with running it? What was it all like?

The model for Kye was that it was a three-tier thing. One to promote my own work. Second to promote new artists who perhaps didn’t have a platform to release their work through, that understood them or was empathetic to them or was excited by them. And third to pay homage to artists who I personally felt as influential to my own work, or inspiring to me in some way. So I wanted to fuse those three objectives together and have that as the drive for the label.

By the time there were 50 releases—there are actually 60 total if you count the 7-inches and the tape and all that—I felt I said what I really wanted to say. It was really convenient because it came at a time when manufacturing became much more difficult. It was much more taxing to run a label in that last year. The amount of returns you’d have, delays. I was with the same pressing plant for all of my time up until the last couple years. And I went through four different ones and it was waking up from one nightmare and falling asleep into another. It really got to the point that I was fucking sick to death of it and was quite happy that number 50 revealed itself.

I can’t imagine what it’s like now. I talk to Mark [Harwood] and he still runs his label [Penultimate Press]. I don’t need that headache again. I’ll leave it to someone younger and driven. I’m out of that one.

So you’re 47 now?

That’s what they say.

Going back to this question from earlier—what sort of things do you still want to do? In the next decade, or, I don’t know, for however long you have left of your life.

(laughs) However long you’ve got left (laughter). What do I wanna do? I’ve been doing a lot of writing. I had half a mind to publish some anthology of writing I’ve been doing for the past three years since living in London. I might do that. I’m just waiting to find out what’s next.

Is there something that you’re into that people would not know about?

Calling the numbers.

What does that mean?

It’s when you become attuned to certain numerical sequences. 2020, let’s say, or 1616. You start to receive them with more frequency. They stop becoming randomized to the point where even without realizing it, you open your phone or you turn to a clock and it’s 23:23, or you wake up in the middle of the night and it’s 4:44. It’s these kinds of situations. You start to read code into the numbers and they suspect that there might be something inherent in this that you need to know about.

What’s the most recent incident of that?

Oh this week they were going crazy.

How so?

It’s endless, just all the time. I couldn’t look at a phone or a watch without them speaking. It got to the point where it felt like we were being hunted.

Was it always like that for you?

No, I first noticed it about 20 years ago.

Thanks for sharing that. I never would’ve known that about you.

Yeah. Calling the numbers. It’s great. [Editor’s note: after this interview, Lambkin sent me a screenshot of his phone and the time was 22:44, and then he sent me a mix which had a duration of 51:51].

Is there anything you’ve ever wanted to be asked in an interview?

No (hysterical laughter).

Well, I’ve gotta ask the question that I always ask, and you’re probably like, “Oh god, Josh is gonna ask this to me right now.” (laughter). Tell me one thing you love about your partner and you love about yourself.

(laughs hysterically for 30 seconds). She’s an original thinker. (through laughter) And one thing I love about myself? (pauses). (mutters under breath) One thing I love about myself… (pauses). I was too stupid to say no.

Say no to what?

I was too stupid to talk myself down from some of these things which seem ludicrous (laughter). You’re here once, right? You might as well enjoy it (laughter).

Purchase Solos at Bandcamp. A Shadow Ring box set is to come in 2021.

Tone Glow Mix

Every now and then, artists will provide a mix personally made for Tone Glow. Mixes will always be available for streaming and download.

I tried to find things that related to what I remember us talking about. There’s some never-before-heard things in the mix and a few early obscurities so hopefully it’ll please all.

—Graham Lambkin

The tracklist for Graham Lambkin’s mix is as follows:

1. The Shadow Ring - “Mindart”

2. V/A ‘Bishopsgate Voices’ excerpt from ‘World War II’

3. Call Back The Giants - “Call Back The Giants”

4. Call Back The Giants - “The Rising / The Lizard”

5. Call Back The Giants - “Fever Dreams / The Hunt”

6. V/A ‘London Sound Survey’ - “The Poet of Villiers Street”

7. Graham Lambkin - “Death Stones”

8. Graham Lambkin - “Pluralism”

9. V/A ‘Paul Buck’s Pressed Curtains’ excerpt from Bill Griffiths

10. The Cat & Bells Club - “Clip Blue Ceap”

11. Anton Heyboer - “Zen Rust”

12. Footprint - “Wooden Fishes In Their Juices”

Download: FLAC | MP3

Stream: YouTube

Discography Dive

Graham Lambkin has released dozens of releases from throughout his career in varying forms, from The Shadow Ring to solo works to one-off collaborations. Below, find reviews of 35 different releases from our writers.

The Cat & Bells Club - The Cat & Bells Club (self-released, 1991)

In listening to The Cat & Bells Club, an early tape from Darren Harris and Graham Lambkin, I’m reminded of the time I’ve spent perusing the Daigoretsu tapes archive. There’s an excitement in hearing the beginnings of artists, of peering into the private space of musicians, of the simple but beautiful ideas that arrive in lo-fi mischief. There’s much of what you’d expect here: ramshackle and unmelodic music, talking that’s serious but humorous as a result, and some charming ideas that stick out amidst all the amusingly dreary sludge.

“The Garden Party” has the funniest trick: imagine someone reciting a story on a tape recorder, stopping because they think they’re done, and then repeatedly starting it up again to share the next passage. It’s self-knowingly clever in the way teenagers often are, which is to say it’s obnoxious but still gets me to laugh. “Father’s Dead” pairs another story with the pre-recorded sound of women quietly talking in the background, this juxtaposition bolstering the dry humor (“I buried Father while my Mother made the sandwiches”). The mangled guitar strums throughout the album occasionally make me smile, and the animal-like sounds on “Them’ers” is a welcome bit of silliness. And really, that’s what all this is, and I mean that as a compliment. Sometimes when I listen to music or read music criticism, I feel like old and self-important adults have forgotten that fun and absurd moments can come from taking things seriously. That was true for Harris and Lambkin when they were 18, and it remained true for everything else they did. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Purchase The Cat & Bells Club secondhand at Discogs.

The Shadow Ring - City Lights (Dry Leaf Discs, 1993)

Though by all means an accomplished album, City Lights is the work of a very different Shadow Ring, one situated comfortably somewhere between The Fall, Jandek, and The Dead C. It is more conventionally guitar-focused than anything they’d make afterward, and Harris actually sings throughout. Yes, sings. Don’t get me wrong; no fan of Dinosaur Jr. or Nirvana or even Sonic Youth would likely recognize this as “rock” music, but at the same time it feels the work of players who had not yet writhed themselves free of the songwriting and performance idioms of a rock-and-roll band.

Graham Lambkin and Darren Harris employ an “S. Fritz” (who would stay on through to Wax-Work Echoes) and Tony Clark to help realize their compositions, with the result that we are frequently listening to three or four guitars battling it out across the full stereo spectrum. Though playing in a decidedly primitivist style, all four performers are clearly quite accomplished at their instruments, winding around one another and occasionally clashing in pleasing bursts of classic 90s-y noise-rock. Nevertheless, among the dissonant, tempoless jamming, there are flashes of what the band would become, like the unexplained bursts of noise scattered across “Oooh Ahh”, or the melodica-harsh noise duet which obliterates whatever melody existed on “Faithful Calls”.

Likewise, on “Cape of Seaweed”, Harris delivers his first, soon-to-be-trademark monologue, about ripped-open mountains, drained oceans, and burning grass, before turning away from the mic and retelling the story as if it were a bar-stool anecdote. Soon, the song unravels entirely, as he and Lambkin get into a shouting match about...something. It’s the kind of moment which would be a bold gesture on any debut album; if it does not quite stand up to the band’s later, dazzling experimentations and ceaseless evolutions, that is nothing to hold against it. City Lights remains an impressive first statement from a brilliant band, and an all-around pleasurable romp of dissonant, freeform guitar skronk. —Mark Cutler

Purchase City Lights secondhand at Discogs.

Klaus Canterbury & The Aces - Energy Ward (Dry Leaf Discs, 1994)

Released the same year as The Shadow Ring’s Put the Music in it’s Coffin, Energy Ward is an interesting Darren, Lambkin, and Goss-featuring release that asks the question: what if The Shadow Ring wanted to sound messier by adding more instruments? The result is a relatively traditional bit of free improv’d rock, with enough of the “Okay, these guys are just fucking around” feeling to keep you admiring all the memorable bits. In particular, it’s Goss on the piano that shines, his keyboard plinks and glissandos sounding cutesy amidst the cacophony. The lo-fi recording is crucial because it doesn’t make the music sound overwhelming (which is boring) as much as it makes it sound boring (which is good). It’s like having a slightly stuffy nose. These guys are sort of just there; noticeable, looming, minding their business. Music like this rarely feels so comfortable in this space. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Purchase Energy Ward secondhand at Discogs.

Transmission - Transmission (Audible Hiss, 1996)

If you want to understand the trajectory of Lambkin’s musical history then the two collaborations he had with Adris Hoyos—Transmission and Elklink—are among the most important and underheard in his discography. Together they map out one of the major turning points in his career, one that led him away from any vestige of traditional form and towards a sonic language all his own. Featuring Adris Hoyos on vocals and drums and Lambkin on guitar, Transmission’s lone album is easily the most out-and-out “rock” album Lambkin has ever participated in. Though there’s plenty of The Shadow Ring’s dementedly simple ear for melody and rhythm here, in most ways it is easier to view it as an outgrowth of Harry Pussy’s no-fi universe. Nowhere else in Lambkin’s discography will you find music this aggressive or sharp, and never again do you see him so close to the influence of No New York. It’s cathartic and throat clearing stuff, though often more valuable as a glimpse of raw emotion than as an album. —Samuel McLemore

Purchase Transmission secondhand at Discogs.

The Shadow Ring - Wax-Work Echoes (Corpus Hermeticum, 1996)

On Wax-Work Echoes, The Shadow Ring ascended from a very accomplished noise-rock/free-improv band to something wholly incomparable and, more importantly, inimitable. This is in no small part due the addition of Tim Goss, whose nasal, analogue synth drones would increasingly come to define the band’s entire sound. What’s extraordinary about Goss’s playing is that it is at once both totally transparent and utterly alienating: on the one hand, we hear every knob-twiddle, filter-sweep and switch-flip he makes. Goss doesn’t hide the fact that he is often improvising, or even the hastily-corrected mistakes which sometimes marr a song’s overall flow. On the other hand, these high-pitched whines are so flat and affectless that they barely sound like the work of a human musician.

This is not to suggest the band were modest about Goss’s inclusion. From the album’s very first moments, his synths are front and center, washing over Lambkin’s and Harris’s tinny guitars and phone-booth vocals, until the latter two simply step out. This sense of drowning-out recurs, here and there, as the band struggles to find the right balance of guitar, piano, synth and voice. I can’t say that they are always successful. As on the opener “You're Holding All Your Feathered Stock”, there are multiple occasions when any recognizeable instrumentation just comes to a stop, as if giving up the fight against waves and waves of jagged noise.

Yet I think, paradoxically, The Shadow Ring best incorporated Goss’s synth by capitulating even further to it; on their subsequent albums, Lambkin and Harris learned to wrap their vocals and instruments around the ear-shredding drones, finding ways to play with rather than against it. This is not to say Wax-Work Echoes is by any means of a waste of time. From the fifteen-minute epics to the thirty-second asides, we find some of the wildest, most abstract experiments in the entire Shadow Ring discography, as well as delightful moments like “Camel Or Carthorse”, on which all of the lyrics self-referentially describe their exact position in the song. For all its occasionally awkward or lopsided moments, Wax-Work Echoes is to my mind the band’s first true masterpiece. —Mark Cutler

Purchase Wax-Work Echoes secondhand at Discogs.

The Shadow Ring - Hold Onto I.D. (Siltbreeze, 1997)

In a way, this is the most consistent album in the band’s 1990s output. Before their freeform tape-noise-rock crumbled apart on the massive, magnificent Lighthouse, The Shadow Ring had settled into a kind of groove, reliably churning out five-to-seven-minute dirges of tuneless guitar, hissing electronics, and ominous, elliptical monologues. It’s no surprise that the band returned to the legendary Siltbreeze label for this release; it sits right at home among albums like the Charalambides’ Union, released the same year, and The Dead C’s The White House, released the year after. These songs have a relaxed, jammy feel, which would soon evaporate as the band pursued darker and more extreme sonic fascinations.

Still, throughout Hold Onto I.D., there are smatterings of the incidental and extra-musical sounds Lambkin would soon obsessively explore in his solo career. “The Way of The World” begins with a few seconds of what I think is a cup of tea being stirred, a tinkling which persists sporadically through the track. Elsewhere, we hear cardboard boxes and even the microphone itself used as percussive instruments. Band members mumble among themselves, and sometimes audibly get up to change instruments. The piano-synth duet on “Wash What You Eat” is interrupted by a barrage of what sound like genuine recording errors, until we realize that they are carefully timed to the rhythm.

These small slippages and blemishes at the margins of the actual playing indicate the band’s increasing disinterest in explicit composition, and even with musicality as such. Nevertheless, Hold Onto I.D. is a phenomenal album which still stands out in a string of phenomenal albums. It strikes the most consistent balance between music and experimentation, between instrumentation, synthesizer, and inscrutable monologues, of any Shadow Ring album. With this album, the band established a method which was so confident and fruitful that one feels they could have put out two or three more albums in the same style. Perhaps that’s why, by the next year, they decided to blow it all up forever. —Mark Cutler

Purchase Hold Onto I.D. secondhand at Discogs.

Elklink - The Rise of Elklink (Polyamory, 1999)

While Hoyos’s presence and style dominates Transmission, Elklink has Lambkin’s thumbprints all over it. The Rise of Elklink fits into the Lambkinverse as an early incarnation of the forms he would explore in his later solo career. From here Lambkin’s sound starts to diffuse and become more abstract; the narratives and surrealist semantic games of The Shadow Ring fall away to be replaced by rustling vocalizations and grimy field recordings. The multi-tracked groans and rasps of “Spoons,” which slide up and down the stereo field before slowly being replaced by what sounds like a bunch of kissing noises, are a perfect example of the hard to define sound they were going after. Predating the boom of lo-fi psychedelia that would emerge in the next decade they were at the forefront of a wave of art music that would soon crash into an unsuspecting 21st century. The Rise Of Elklink doesn’t quite pull together as a full listening experience, but in hindsight it’s a key early document of some of the most important music of modern times. —Samuel McLemore

Purchase The Rise of Elklink at Bandcamp.

The Shadow Ring - Lighthouse (Swill Radio, 1999)

With a few years of touring and four albums under their belt, The Shadow Ring now had the confidence to tackle their longest and most ambitious work to date. With their previous albums marked by the experimentation of a band finding their sound, and their latter albums charting territory that reached clearer definition in Lambkin’s solo career, Lighthouse stands easily as the most complete statement they released during their lifetime. Not coincidentally, this is also the last album they completed before Lambkin moved to the United States in 1998 and is the only album that finds Karla Borecky and Adris Hoyos credited.

The basic building blocks are much the same as before, but have more depth and density, with the sheer length of the album allowing the band to contrast moods against each other and build fragmented narratives across the whole. The Shadow Ring’s philosophy seems to be to undercut expectations at every turn, so when they build themselves up in a lather, such as on highlight “Knock Between Doors”, this is also when they try their hardest to pull the rug out from under the listener. Most of the time this is quite successful, the main difference between this album and others is how cleverly it grows across its length. Alternating between strangled humor (“Mindart”) and sick familial warmth (“If It Is A Boy”), Lighthouse is a masterpiece of cyclical form, spiraling in and out until it collapses in on itself and must start all over again. Five bloody stars. —Samuel McLemore

Purchase Lighthouse secondhand at Discogs.

The Shadow Ring - Lindus (Swill Radio, 2001)

Lindus captures a pivotal moment in Lambkin’s career, between when he made what most people would still recognise broadly as “music”, in the sense that it featured instruments and (spoken) vocals, and his subsequent, ongoing explorations of field recordings and the furthest fringes of sonic minimalism. There are still melodic tracks here. As the title suggests, “We’re Complex Piss” has some of the silliest lyrics, but also the greatest moment of transcendence, when Lambkin’s voice gives way to a series of thundering synth chords. “Lindus Hologram” is seven minutes of blissful vintage synth arpeggios, like a Nintendo Game & Watch having a wonderful dream. And then there are tracks like opener “New Born”, which could easily be either the muted sound of a tire on gravel, or the amplified sound of pure, empty vinyl hiss. (Listening again, it uncomfortably reminds me of some of my own recent music, and I realise just how deeply Lindus and I’m Some Songs are embedded into my own psyche.) “New Born”, “I Lap It Up” and “The Liquid Boys” are like open doors, leading somewhere beyond ‘music’ entirely. They indicate not only the direction of the next and final Shadow Ring album, but, in a sense, the direction experimental music as a whole has followed in the twenty-first century. —Mark Cutler

Purchase Lindus secondhand at Discogs.

Tart - Radio Orange (Swill Radio, 2001)

I’ve always been pretty suspicious of The Shadow Ring, who seem so preconceived and passionless, they might well have singlehandedly invented the bedroom improv-geek loser genre.

—David Keenan on The Shadow Ring’s Hold Onto I.D. for The Wire, May 1998

Our main heritage from the Aesthetes of the 19th century is the general notion that one’s life should be a work of art. But we take the idea further. Everything, from the individual to the social, should be a work of art. The old avant-garde axiom, “everyone an artist,” has been largely misinterpreted (often by the avant-garde itself) to mean that everyone can be a musician, poet, etc. The underground is smothered in waves of bad art which effectively silence its revolutionary voice. This is just the sort of brilliant recuperation scheme we have come to expect from the Spectacle.

The correct interpretation of the idea of total aestheticization is that all actions can be carried out in an aesthetic manner.

—The Anti-Naturals (who at the time included Scott Foust, Prof. Timothy Shortell, Karla Borecky, Graham Lambkin, Michael Popovich, Adris Hoyos, Darren Harris, Robert Beerman, Howard Lester, and Tim Goss), in an interview with 3:AM Magazine, 2001.

The debut album from Tart, the trio featuring Lambkin and Idea Fire Company’s Karla Borecky and Scott Foust, has a beautiful opener in “The Rabbits Of Mangtarau Pt 1.” While it bears resemblance to the intimate collaging found in Idea Fire Company’s The Fourth Dimension is Money and Lambkin solo pieces, it also has an especially thought-provoking moment provided by playful arranging. We hear the sound of an object rolling around on a table, and then the faint sound of someone screaming in anguish, all before that same object falls down to make a loud sound. While these noises are obviously not directly connected, it evokes the playful imagination of a child bored in their bedroom and wishing they could do more; in this case, it’s as if they’ve inflicted physical pain on an enemy from a distance.

This sense of the supernatural sets the album up nicely for “Chopin in a Shell,” a droning sci-fi horror romp akin to much of Idea Fire Company’s 90s output. But more than that, it’s an individual moment that gets at what is so spectacular about much of this music, Lambkin or otherwise: there’s a sense of the impossible being captured in the smallest of moments and their interactions. It’s the action of having fun with what’s given, much like a child would without any traditional toys. It’s the fantasy world of a kid lived out in the midst of adult disenchantment. It’s a reminder of music’s infinitude, and how music is, in that way, very much like play. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Purchase Radio Orange secondhand at Discogs.

Graham Lambkin - Poem (For Voice & Tape) (Kye, 2001)

There are certain albums that, when they begin, are like plopping down and settling into your favorite chair after an exhausting day, an instant fix of coziness that brings a contented smile to the face. Poem (For Voice & Tape), Lambkin’s 2001 debut solo LP, is one of those for me. Released while The Shadow Ring was still active—four years before I’m Some Songs would be released, and one before fan favorite Lindus—Poem is a bit of an oddball in the prolific artist’s discography, more of an experiment or a focused conceptual piece than anything (as opposed to the quite eclectic range of sources and techniques he would soon develop), but anyone who knows me can probably guess that for me, that designation is far from detrimental. The LP was also the inaugural entry in the catalog of Lambkin’s legendary Kye Records, which ceased operations in 2017 following its fiftieth and final release: Gabi Losoncy’s HH, a document that, fittingly, rivals Poem in its obstinate reductionism and hypnotic stagnancy.

Yes, I would certainly call Poem (For Voice & Tape) cozy (although if past interactions have taught me anything, my version of coziness seems to be very different from most others’), but there are so many more layers to it than that. And by “layers” I’m not referring to the sounds, of which there really aren’t that many—in both parts, a heavily slowed tape recording of Lambkin’s speech coupled with the constant slaps of a sputtering faucet; in part I, a thick droning hum; in part II, assorted but sparing bits and bobs (stick around to the end of this half for a lovely surprise!). Anyone who’s heard a Shadow Ring record or pretty much any of Lambkin’s solo work besides this one knows the guy already has an amazing, full-bodied Kent accent that makes every word drip like treacle, so it’s not surprising that even when altered so drastically it retains, even heightens that sonorous resonance. Though played back at a sluggish crawl, dissolving any remnants of intelligibility into the slobbering yawns of a massive beast, the presence of words at all introduces an indelible linearity to the proceedings, somehow enabling what are almost entirely static soundscapes to progress at an engaging pace. All of time seems to simultaneously speed up and stop when one spins this album. —Jack Davidson

Purchase Poem (For Voice & Tape) at Bandcamp.

Tart - Bring in the Admiral (Swill Radio, 2003)

“Two small Casios, guitar, and shortwave/cassette boombox, plus a few odds and ends and the Anti-Naturals trademark tight editing.” These are the instruments credited on Tart’s Bring in the Admiral. And really, it’s the editing that’s crucial on this album of quiet and cloudy drones. There’s a sublime, thalassic movement to “Sailor’s Story,” the sound of insects providing solace amidst the undulating synth. It pairs nicely with “Emergency,” which also feels nautical but creeps and stutters along with a nighttime mystique. The real keeper, however, is “Right Now!”, a short track comprised of heavy breathing intermingled with squiggling and stomping electronics. Much credit, though, to the song title I’ve laughed hardest at in Lambkin’s discography: “Great Sadness in an Italian Restaurant.” I listen to its austere church-like organ drone and imagine a meatball falling to the ground. —Joshua Minsoo Kim

Purchase Bring in the Admiral secondhand at Discogs.

The Shadow Ring - I'm Some Songs (Swill Radio, 2005)

This is one of the chilliest albums ever. An absolute eldritch nightmare. In theory, the same elements all carry on from Lindus—the synth drones, the sounds of scratching, rustling, and inscrutable monologues—but they are all stretched, warped, buried deeper in the mix… It's unsettling, and the sparsity gives our mind ample time to wander towards gruesome imagery when, for instance, we hear the slowed, laboured sound of someone breathing through a tube or pipe, and then, somewhere in the distance, a door creaks open and shuts again.

That this comes from a band which once specialised in a kind of talky, noisy maximalism, somewhere between Captain Beefheart and The Fall, makes this album more unnerving than if it had been released by some prolific ambient producer like Celer. There is something terminal about it—beyond its being in fact the Shadow Ring's final album. One feels distinctly that they could have gone no further, that they could have stripped no more away. The album feels like a ghostly remainder, made by nobody but nevertheless present. The band is gone, or dead, it seems to say, and this is all that's left: echoes, fragments. Beyond that, we discern nothing. The album does not feel like gazing into the inky abyss of a deep chasm or night sky, but rather like a blank white surface, like a boundless plane. It's right there, so close we can touch it, and yet it gives us nothing, says nothing, except exactly what it is: I’m Some Songs. It's a frightening, maddening work of utter genius. —Mark Cutler

Purchase I’m Some Songs secondhand at Discogs.

Graham Lambkin - Salmon Run (Kye, 2007)

Salmon Run is the best Lambkin solo record, the most famous, the most well-regarded. I’ve always known this. Everybody knows this, I thought. So in researching for this feature, I was bewildered to find that it had no contemporaneous reviews in any of the established music outlets save one. But in a whisper network based around the electroacoustic improvisation scene, the I Hate Music forums, and Rate Your Music, its reputation grew. Brian Olewnick, biographer of Keith Rowe, wrote a blog post about how he turned his friends onto the album: “Last night I played it at Record Club and wowed the group, a couple of members insisting on acquiring the disc.” Jon Abbey, head of Erstwhile, subsequently said that he wishes he’d released it (though he got an enviable consolation prize in releasing the Lambkin/Lescalleet trilogy). Rate Your Music user Hivedrops has kept a running diary of experiences with the album since first hearing it in 2017, including this post from a year ago: “Everyone at the dinner table looked distraught, we all talked like we were on the edge of a breakdown. I thought of Salmon Run for the first time in a few months.” These posts are only select visible traces of conversations that took place on private forums and file-sharing sites, many now lost. But the groundwork was laid, and now an edifice of public reappraisal, like this feature itself, can be built.

So what makes Salmon Run so special? For one, it represents the moment—includes the moment, actually—that Lambkin discovered a new practice. He describes to Nick Cain of The Wire (“Happy Accidents,” June 2009) that he was recording audio of himself taking photographs of himself with classical music playing in the background. When he played the tape back, he had a revelation: all the sounds he was making were superimposed over the classical music in an aural equivalent of the work of artist Arnulf Rainer, who painted over already-existing art. You can hear this on “The Currency of Dreams,” wherein digital camera shutters and beeps are interspersed with bouts of laughter over a piano and string piece. The whole thing is frankly unsettling. You’re listening to someone listening to music, more interested in the sounds they make than the music itself. Wait, no—you’re listening to somebody listening to music as they record themselves taking pictures of themselves, laughing all the while, like a fun-house mirror of reflexivity and voyeurism.

Add to this the fact that Lambkin overdubs other sounds and alters the musical portion itself—as in the repeating piano segment at the end of the above track—and the whole thing becomes a puzzle. Recorded music merges with domestic sounds that may or may not be occurring simultaneously. Halfway through “Glinkamix” the music falls away in favor of a distant rumble and clinking glass. “Jungle Blending” features windchimes along with what might be an actual jungle. “Jumpskins” opens with a full minute of Lambkin panting and squealing into a handheld recorder. It’s impossible to anticipate what will happen moment to moment, and traditional categories of music/noise, live/recorded, private/public fail completely. Perhaps this is why Salmon Run inspires such devotion in those who hear it—you simply cannot, unless you are Lambkin himself, understand it. But it becomes important unto compulsion to try. —Matthew Blackwell

Purchase Salmon Run at Bandcamp.

Graham Lambkin / Jason Lescalleet - The Breadwinner (Erstwhile, 2008)

The Breadwinner is the first part of a four-disc set across three albums. Jason Lescalleet visited Lambkin’s home in Poughkeepsie, New York for this one; his visit was reciprocated by Lambkin at his own house in Berwick, Maine for Air Supply in 2010; the duo traveled together to one another’s childhood homes in Folkestone, Kent, UK and Worcester, Massachusetts, US for the double-disc Photographs in 2013. There are all sorts of patterns and symmetries to be found across these four discs—for example, the run times for all the tracks on The Breadwinner match those of the “Lambkin disc” of Photographs, while the same is true for Lescalleet. Taken together, the four discs present an investigation into location, friendship, and memory. But of course in 2008 we didn’t know all this. We just had a new album from two towering figures of field recording and improvisation.

The subtitle of The Breadwinner is “musical settings for common environments and domestic situations,” and that’s what it gives us, in a way. Except that this is not music that you would want to play to spruce up your own domestic situation a la Satie’s furniture music. Instead it’s music—often other people’s music, not Lambkin’s—played in his house, then recorded along with all manner of ambient noise and field recordings. The first track “Listen, the Snow Is Falling” features a lovely choir along with creaks from Lambkin’s chair and the sounds of his children playing in the next room. At some point the crackle of a fireplace enters. It’s all very nice and certainly domestic but unless you live alone I would recommend headphones. Especially because, though this is a “Lambkin disc,” Lescalleet’s noisier tendencies dominate at times. “E5150 / Body Transport” features more atonal humming than one would expect from Lambkin, though the more natural tracks that feature his sonic signature, like the clicking and clacking and bubbling and burbling of “Two States” (solid and liquid, I assume) are quietly unsettling in their own way.

This is part of the fun: figuring out who was responsible for which sound by comparison with each musician’s catalogues. But more often than not it’s impossible to say with any confidence who did what. Instead, this is a true collaboration, a portrait of a duo at the beginning of one of the greatest runs of albums in the twenty-first century. Whoever initiated them, these sounds—the soft crackle of “The Snow Is Falling,” the distorted piano of “Lucy Song,” the bassy growl of the title track—welcome the listener into Lambkin's strange, fractured dreamlike home. —Matthew Blackwell

Purchase The Breadwinner at Bandcamp.

Graham Lambkin - Softly Softly Copy Copy (Kye, 2009)

Ursula K. Le Guin’s “Texts” paints a woman in flight from language. This is not a recapitulation of the classic psychoanalytic drama—the originary violence of being ushered into the world of signs and all attendant complications—that completes in utter rejection and anti-linguistic atavism à la Themroc. Rather, Johanna escapes to free herself from the demands of language, to free herself from the ceaseless scanning, parsing, coding, and decoding of the world as it appears to her. Words hunt her down and insist upon a response. Language leaks into her little seaside hideaway, in Finnish radio programs and tourist t-shirts. Even the waves leave behind messages in spumy calligraphy.

“If she could read them they might tell her a wisdom a good deal deeper and bitterer than she could possibly swallow. Do I want to know what the sea writes? she thought, but at the same time she was already reading the foam…”

I felt that same exigency, that same tension of being tangled in the semiotic chain, when first trying to read Softly Softly Copy Copy. A procession of sounds through spaces, legible yet unintelligible, unbothered by definition. “[E]sse hes hetu tokye to’ ossusess ekyes. Seham hute’ u,” says the sea at the beginning of the first piece. Woolgathering along the shoreline before being thrown into groaning grottos, across its two arrangements Softly Softly pulls you through the thinnest capillaries into the nave bells bursting. Sharpening scimitars seethe while your face rolls through gravel. Lambkin drops the recorder and it clambers down the riprap ears first. The hull of the submersible wails against the pressure. The piano under the water looks like a shark. The tightening of breath in every chest.

It is a disorienting tour though carefully arranged. With microscopic focus, each grain of sand along the shore speaks as clearly as the deft curl of Samara Lubelski’s violin or the languid scrawl of Austin Argentieri’s guitar. Like the tourist t-shirt or the Quaker lace tablecloth Johanna discovers when she returns from deciphering the shore, as signs, semaphores in the most literal sense, so too do the sounds of Softly Softly demand to be read even as the scouring decontextualization of its elements thwart any confidence in our attempts to provide interpretation. We struggle to situate ourselves between the sea and the shushing voice, the church and the tumbling piano, animal bellow and birdsong.

What we are looking for is not a hermeneutic but a posture. It is a posture that allows oneself to be thrown, as script is thrown across a surface and sound across a space. From this position, Softly Softly is beautiful in a dazzlingly obvious way. In a bizarre antinomy of easygoing restlessness, the compositions move with rough grace across plunging depths and scraping airs. Everything from church bells to goosetalk to a microphone dragged across concrete to three carefully plucked strings to water in all its intensity is luminous.

Still, despite now having lived in this work for years, having charted the surround, I feel no closer to understanding it, to making something out of its sigillary collage, than when I first listened. I can read it, “pith wot pith wot pith wot,” clear as day, but I cannot tell you what it means. This, of course, is what I find most invigorating about Softly Softly. There is an open-endedness, an ambiguousness, a playfulness to all language, though not every text can so ably dramatize the opacity of signs.

The further I go, the deeper I dive, every time I return with something, a little bit of presque rien. My collection, though sizeable, takes up thankfully little space, and though devoid of content, it’s hard to imagine parting with it. What does it mean, and what do I do with it? I’m not sure, but, for now, I plan to treasure it.

Le Guin’s story ends with Johanna being drawn deeper into language, reading the wide-looped script along a lace collar:

“My soul must go,” was the border, repeated many times, “my soul must go, my soul must go,” and the fragile webs leading inward read, “sister, sister, sister, light the light.” And she did not know what she was to do, or how she was to do it.

Purchase Softly Softly Copy Copy at Bandcamp.

Graham Lambkin - Dumb Answer to Miracles (Penultimate Press, 2009)

Primarily a written work, Dumb Answer to Miracles is a collection of Lambkin’s lyrics and poetry. It comes with a CD of music that, according to Lambkin’s site, is related to what’s in the book—but I don’t have the book. It might very well be the case that the written work elevates the musical work and vice-versa, but even though I am almost surely lacking the complete context that frames this release the single fifteen minute track on the disc is my most played track of anything in Lambkin’s discography besides “Abersayne” and “Attersaye” split single—which has a strong chance of remaining my favorite single until I’m dead and in the dirt.

To explain it simply, the track is a loop of the first minute of a choral chant by The Russian State Symphony Cappella—music from the Russian Orthodox Church—repeated unchanged for the entire runtime of the track. It sounds simple, and perhaps even a little boring, but something about taking a fairly compelling phrase from a piece of music and stretching it out ad infinitum is fascinating to me. I would normally never go through the effort of isolating a piece of a piece of music to listen to over and over, and what Lambkin has done here has pointed an electron microscope at this one minute phrase; every time it loops I hear something different, think of something different, and focus on something different.

Today, while looking for the source of a meme I saw on twitter featuring a dog with a slice of butter on its head, I found a ten hour version of it instead. I ended up leaving it on for a solid hour or so and it was so funny to me that I was in tears from laughing so much. It’s pretty funny on its own, but not that funny—but every pass through this seven second snippet slowly caused a phase shift in my head and I started hearing new sentence constructions of the same words depending on where my brain decided the starting point should be. Dumb Answer to Miracles is a masterclass in the butter dog effect; it allows me to consider every facet of something I might otherwise not have given a second thought. —Shy Thompson

Purchase Dumb Answer to Miracles secondhand at Discogs.

Graham Lambkin - Dripping Junk (Penultimate Press, 2010)

The music of Dripping Junk is also supplemental to a bound tome, this time a collection of his drawings. I don’t own the book for this one either, but you can see many of the drawings online; Lambkin’s art is strange and wonderful—skillfully twisted and abstracted versions of familiar forms with loose lines that suggest movement and draw your eyes in all directions. Graham Lambkin seems skilled in nearly equal measure as a visual artist, writer and musician and it’s just not fair that some people in this world get all the talent. I occasionally do look at the drawings while listening to the music meant to accompany them, but it’s such a compelling track that I often just listen to it by itself.

Similarly to Dumb Answer to Miracles, Dripping Junk consists of a short ten minute piece of music that is one unchanging loop. The source of the loop is significantly shorter: one bar of relaxed playing on an acoustic guitar, with what seem to be a couple of incidental sounds caught in the mix. To my ear, it sounds like some sort of field recording underpinning the recording—maybe a pile of leaves blowing around in the wind? There’s also some sort of breathy sound that could have been made by a person, the bellows of an accordion, or god knows what else. At various points in the loop these difficult to identify sounds have evoked the imagery of a windy autumn day, a peaceful beach, a winded runner, and a sickly person on a respirator. Lambkin’s ear for musical phrases that bear repeating legitimately floors me, and this pair of tracks that very well may have been considered nothing but a nice bonus on top of other work keep me coming back to them often because of their unique ability to re-contextualize themselves constantly. —Shy Thompson

Purchase Dripping Junk secondhand at Discogs.

Graham Lambkin / Jason Lescalleet - Air Supply (Erstwhile, 2010)

Air Supply is either the middle entry in a trilogy of albums by Lambkin and Jason Lescalleet, or one half of a diptych (so, a half of a half) which places it and The Breadwinner on one side, and the two discs of Photographs on the other. The fact that Lambkin and Lescalleet decided to mirror the track titles and exact runtimes of the first two discs on the latter two make this series of albums impossible to think about as wholly separate entities. What could it mean? Are they meant to be played simultaneously, like some elaborate Dark Side of the Cast-Iron Pan? Probably not, but the mystery of it all is indicative of the way Lambkin and Lescalleet work across all four discs, using subtle clues and surface traces to indicate whole, hidden worlds of meaning.

On Air Supply, those worlds are especially hidden. Where The Breadwinner and Photographs generally both make their domestic focus explicit, placing the listener in a milieu of household appliances, creaking floors, grocery trips, and everyday chitchat, nothing on Air Supply sounds so familiar. Instead, deep, intermittently melodic drones and blasts of screeching noise sluice around beneath unplaceable sounds which, at best, merely suggest walking, scratching, wheezing, digging, boiling, and so on. If the surface sounds sometimes tell fragments of a story, the others suggest a vast, dark chasm yawning somewhere nearby. For some reason, I keep thinking of Antarctica.

This album is often not as highly regarded as its older and younger siblings. If the other two are generous entryways into Lambkin and Lescalleet’s homes, social circles, and headspaces, Air Supply is withholding, disorienting, and sometimes abrasive. It feels the most heavily manipulated, yet paradoxically, also where Lambkin and Lescalleet seem most absent, lost in ominous whorls of sound. Nevertheless, Air Supply is a formidable, unnerving listen on its own terms. It is a dark journey well worth taking, and deserves its place in the all-time great musical trilogies. —Mark Cutler

Purchase Air Supply at Bandcamp.

Graham Lambkin - Amateur Doubles (Kye, 2011)

Amateur Doubles is in large part a love letter to listening. I remember well the first time I was able to document a sublime marriage of, if you will, atmospheric music and “musical atmospherics” (check that out here), but not whether it was before or after I’d heard this record; regardless, Lambkin’s 2011 opus, which essentially marks the halfway point between the beginning of his solo career and now, both captures and has influenced my personal approach to appreciating sound. I’ve never thought of this comparison before, but ever since I was a kid I needed mixes of different textures in food—crunchy peanut butter in PB&Js, M&M’s in ice cream, spaghetti and garlic bread sandwiches—and I think my constant search for environmental harmony is somewhat similar. So, unsurprisingly, the particularly delightful sonic contrasts and complements (often both simultaneously) that comprise Amateur Doubles have a special place in my heart.

The LP consists of two side-long tracks, each structured around extended tape recordings of Lambkin riding in the car with his family as an instrumental electronic CD originally released in 1975 plays: first, Besombes/Rizet’s Pôle; second, Philippe Grancher’s 3000 Miles Away. Augmenting these gorgeous ennui-scapes, which mostly take on the form of mesmerizing, shifting drones as the microphone is moved around and the shimmering pulses of the music meld with the yawning rush of the moving car, are various trademark-Lambkin festoonments—mouth sounds and whistle ditties reminiscent of his more recent material with Joe McPhee and Bill Nace, abrupt jump cuts and splices, snatches of speech not quite stripped of all their context, liberal wind distortion—as well as bits and pieces of humanity as Oliver pipes up from the backseat to tell his dad what time it would be in space, a horn is indignantly honked at an intersection, the engine is stopped and started unceremoniously.

According to the original liner notes, Amateur Doubles was intended, at least in part, as “a perfect snapshot of life on the open road,” but to me it is so deeply interior, nestled and enveloping but not at all claustrophobic, a perfect encapsulation of the comfortable, well, capsule one’s car becomes while cruising down a beautiful road with the right music playing. I’ve been thinking about attempting to immortalize the same using my ripped CD of Chief Keef’s Back from the Dead 2 as the musical groundwork. Crowdfunding campaign for “materials” coming soon; keep an eye out. —Jack Davidson

Purchase Amateur Doubles at Bandcamp.

The Shadow Ring - Remains Unchanged (Kye, 2012)

A companion to Life Review (1993-2003), which compiled tracks from every release made during The Shadow Ring’s lifetime, Remains Unchanged is instead pulled from their unheard archives. That a compilation covering their entire career is their most wide-ranging album is no surprise, but that something culled from over a decade’s worth of cast-offs can also be the most satisfyingly complete release in their discography is perhaps not nearly as expected. Essentially a posthumous album that caps off the artistic and narrative arc of the band, it’s great evidence for something I’ve long believed: that Lambkin's greatest artistic gift is as an arranger instead of a performer or writer.

Sequenced chronologically, Remains Unchanged follows the narrative of The Shadow Ring from their uncertain early years through successive iterations of their aesthetic until they had fully fine tuned their conceptual and sonic aims. Always keenly aware of the album form, Lambkin structures Remains Unchanged so that as it sprawls across 2xLPs worth of vinyl, each side covers progressively less and less time in the band’s history, until all of side four is given to their final album, I’m Some Songs. Placed into this context the diffuse, ghostly compositions of their final period gain an incredible weight. One of the greatest accomplishments from a band who have never quite gotten the recognition they deserve. —Samuel McLemore

Purchase Remains Unchanged secondhand at Discogs.

Keith Rowe / Graham Lambkin - Making A (Erstwhile, 2013)

Making A is all about perspective. It begins with a wide shot of a nation in decline. The first thing you hear is audio from an airport waiting area, which means, in the United States, a news broadcast of another school shooting (Newtown, this time). This is briefly interrupted by an announcement that military personnel are welcome to a special USO lounge. In the background are pop radio songs, people walking by, chatting, coughing. It’s horrifying and mundane.