Tone Glow 039: Simone Forti

A video premiere of Simone Forti's 'Al Di Là: An Evening of Sound Works' and an interview with Forti herself

Simone Forti

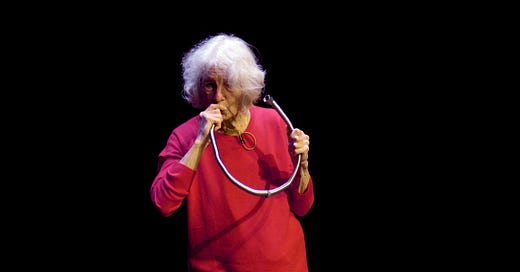

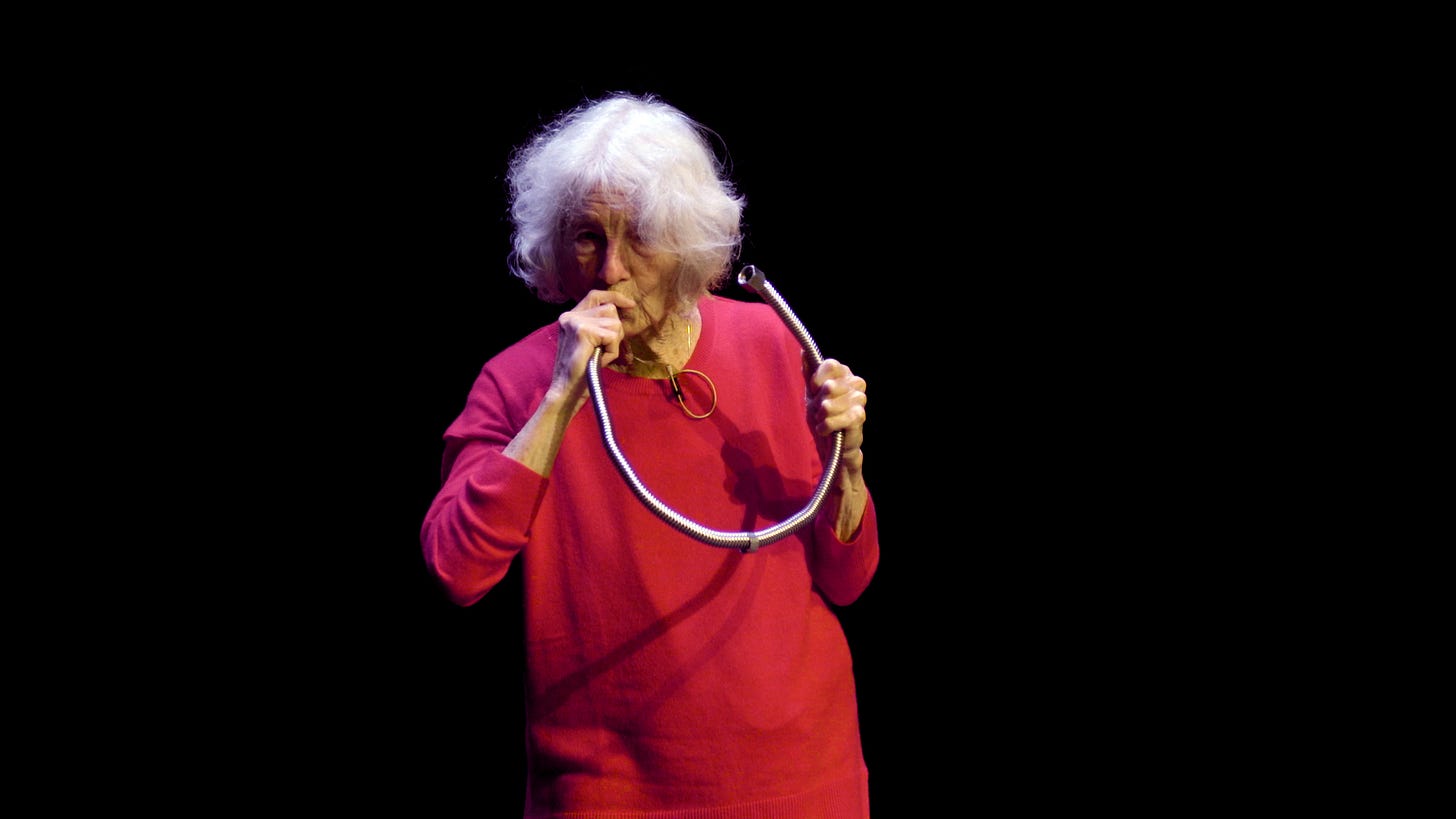

Simone Forti is an Italian born, multi-disciplinary artist currently residing in Los Angeles. Forti’s legendary body of work has always transgressed commonly-held boundaries between dance, performance art, sculpture, and music. Her Dance Constructions were revolutionary not only in challenging basic assumptions about what dance could be, but in their interpolation of her own feelings and experiences into structured, physical improvisations. Since then, Forti has continued to study the capacities of human and animal bodies, producing a body of choreographies, musics, writings, and performances that has spanned six decades. The warmth and generosity of her personality shines through her works, which often leave the performers themselves smiling or laughing by the end.

This month, Saltern is releasing Al Di Là: An Evening of Sound Works by Simone Forti, a two-part video documentation of a live performance in February of this year. You can find both videos embedded immediately below. The performance follows an album of the same name, released by Saltern in 2018 and reviewed positively by the previous iteration of Tone Glow. The performance program comprised some of her most famous pieces, as well as other songs and sound works dating as far back as 1969, but which have rarely been publicly performed. At that event, Forti was joined by Tashi Wada, Julia Holter, Jessika Kenney, and Corey Fogel.

Al Di Là: An Evening of Sound Works by Simone Forti

Part One:

Part Two:

Forti has also released Fool on the Hill and Italian Folk Song (1968) for free download on Bandcamp. Recently, Mark Cutler spoke to Forti over Skype about the performance, her life, her works, and the memories behind them. Forti also discusses her recent work, and recites a poem. The complete interview follows below.

Simone Forti: You can hear me?

Mark Cutler: Yes, I can. I can see two of you.

You see two of me?

Yes, do you see two of you?

That’s because there are two of me!

(laughs). How’s your day been so far?

Very nice. Jason has been my assistant for some ten years, and now with COVID, we meet in the park, and sit on benches and talk about what needs to be done.

It must be nice having—are you surrounded by a lot of parks?

Well, not a lot of parks, but there’s one park just almost across the street from me.

That’s very nice. We’re quite lucky, we’re about a block away from Tompkin’s Square. It’s nice to live close to a little bit of nature.

Really, yeah.

Do you have a memory from when you first moved to New York? Something you noticed about it, or do you remember where your first Apartment was?

My first apartment in New York? It was somewhere around 80th Street and 8th Avenue.

Wow, the Upper West Side! That must have been very different.

It was. And, I knew Nancy Meehan, the dancer, in San Francisco. She had just moved to New York, and was just moving out of her apartment when Bob Morris and I were looking for an apartment. So we just moved into the apartment she moved out of. And, she was giving up her job as an assistant nursery school teacher, at Temple Emmanuel, and I was looking for a job. So, I stepped right into her apartment and right into her job!

So, you took over her life! Did you stay there for very long? I know most of the stuff you would have been interested in was happening way downtown.

Yes. We moved downtown to a small loft on 1st Street and 1st Avenue.

And what about San Francisco? What first struck you about San Francisco?

Well, I moved to San Francisco from Portland, Oregon, where I had just done two years at Reed College—and that’s where I met Bob Morris, and we got together. We both dropped out of school and moved to San Francisco. Now, I bet it was more his wanting to be in the art scene [there]. I wasn’t sure about what I wanted to do at that time, until I met Anna Halprin and really clicked with her work. I studied with her for years, and performed with her, and was completely focused in that way. I was taking the Greyhound bus to Marin County, and not very aware of what was happening in San Francisco. Since then, I’ve become aware of the poetry scene—Ginsberg and all those people—and wish I had been a little more hip to that! But I stayed focused with Anna, and that was good for me, it worked out.

Did you feel like that period of work had come to a natural end when you moved to New York? Was that sort of what prompted the move?

Well, I think it did come to a natural end. Four years of working with your mentor, and then it’s time to start complaining about her! (laughs). But also, Bob wanted to get to New York. He was painting abstract expressionist paintings, and, I think, was very much admiring Willem de Kooning, and wanting to be where he could see the paintings he was excited about.

I moved to New York in November 2018, and of course, on my second or third day here, I went to visit the Museum of Modern Art. I was just walking around in the museum, and I accidentally walked right into the middle of a performance of the Dance Constructions. I didn’t realise at the time that the Museum had recently ‘acquired’ those pieces, and that in your performance [in February], those pieces were ‘on loan’ from the Museum. I wonder, how it changes the pieces for you, now that their ‘home’ is no longer the theater, but the museum?

Well, their home has always been more than the theater. They’re meant to have the audience be able to walk around them, to look at them as sculptures as well as performance. But it does make a difference from the gallery to the museum, but not so much a spatial difference—because they’re in a room, they’re in a hall, they’re in a gallery. Doing Accompaniment for La Monte’s “2 Sounds” and La Monte’s “2 Sounds” on stage, that was the first time we did that on stage.

It also changes, it seems to me, the accessibility of the pieces, because historically, dance has been one of the more privileged or restricted art forms—you often have to live in the right city, and be able to afford tickets, whereas now the works can reach a much wider audience for a much longer time.

Yes, although the first… ‘concert’, I’ll call it, when I first showed all of the pieces, was in a loft in New York, a downtown loft which happened to be Yoko Ono’s loft. She wasn’t, at the time, “The Great Yoko Ono”. I mean, she was, but (laughs) people didn’t know it!

The program that you performed that night, which was documented in the video: I was very excited, because I had already been curious about the time you spent in Woodstock in 1969-70, and I know in the Handbook in Motion, that time of your life kind of forms an anchor point for a lot of what you write, but until a couple of years ago, it seems like the works from the time [the Hippie Gospel Songs] were largely inaccessible. What inspired you to bring them more to light now?

Well, I hadn’t thought of them as public! They were what I sang in my car! So, I guess I sang them for a friend, and I probably sang them for Tashi [Wada], and it came out in the group of friends that ‘Simone had these songs’. So then it became public.

A lot of the Dance Constructions have been thought of as ‘dance’ works for decades, and it seems more recent that the focus has shifted to looking at them as sources of sound, or as musical in themselves. I wonder if that comes from a relatively recent shift in the way that you think about them?

I think that being in The Box Gallery—being one of the artists in The Box Gallery—which I think happened eight years ago… Mara [McCarthy] had the idea that a lot of my pieces have an element of sound, so why don’t we do a show?—and the title of the show was Sounding. We pulled together several of my pieces that have this element of sound, but I was [already] generally using whatever—whether sound or objects. One of the [Dance Constructions] is called Cloths and it consists of three frames with cloths that the performers toss over the top. And the performers are singing, so you don’t see the performers, or the ones who work the piece, but you hear them singing songs, and it came to me with those parts, with the cloths and the people being hidden behind the cloths, and the action being the cloths themselves, falling over the top. It isn’t that I thought, or that I made a body of work that ‘has sound’ in it, it’s just that a lot of my work does have sound in it.

And of course, dance has always been historically linked to music, to musical accompaniment, but it’s rarely considered in itself to be a source of sound, or that it could produce, or be music.

Yes, and you might think of those pieces [not as dance] but as performance art, because cloths—where’s the dance? Cloths are the dancing. I don’t think of all the pieces as being dances, necessarily.

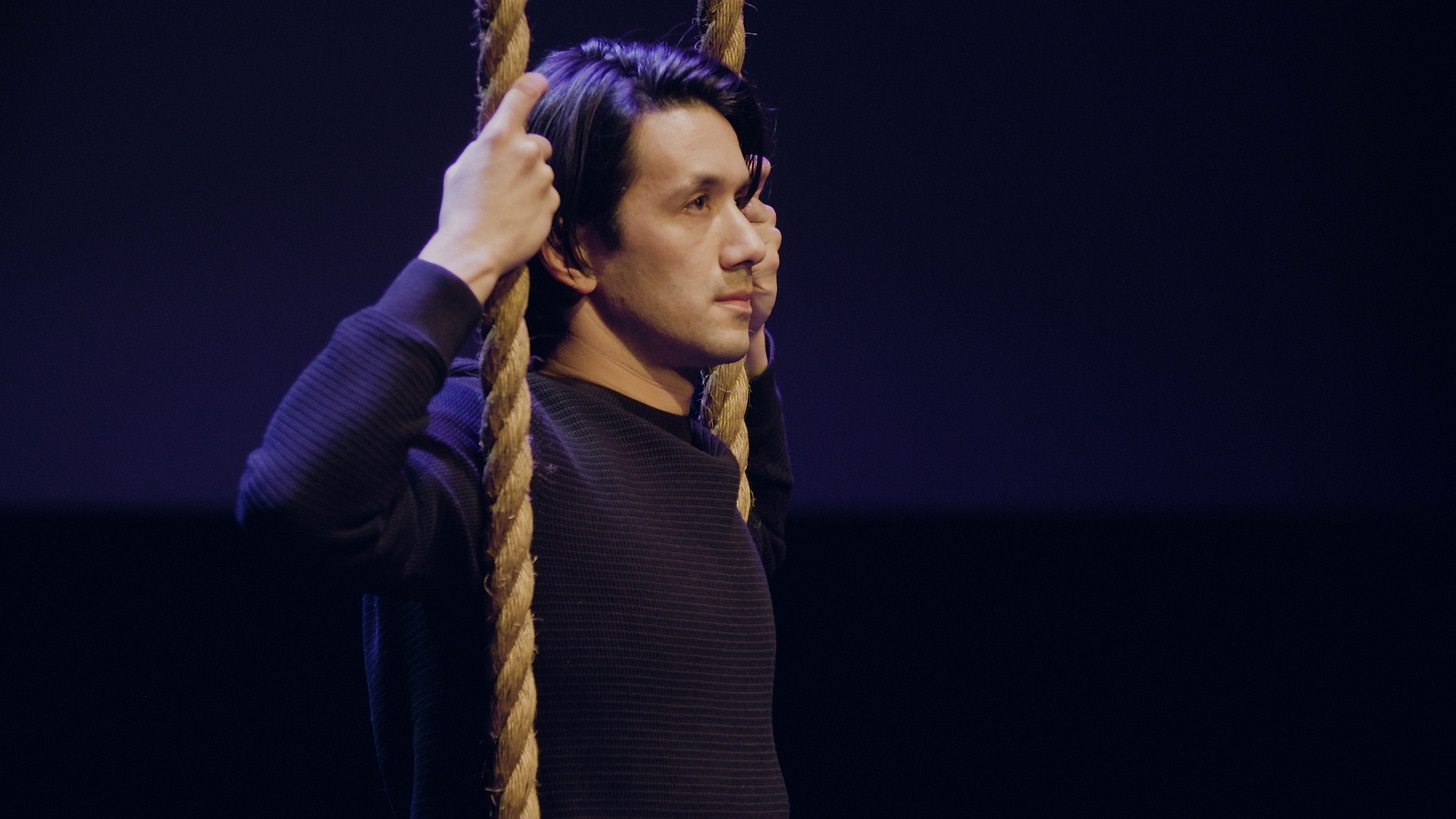

Like in Accompaniment, what you might think of as the main performer in the room, doesn’t make any movements—mostly, the only element really moving is the rope.

But they [the performer] have presence.

Exactly. So I was wondering what your earliest memory is, of making music? Maybe from your childhood?

Oh, that’s an interesting question. I’ve never thought of that. I know that when I was in grade school, or junior high, that Kay Starr was a big singer, and I liked to imitate her. But going further back, I learned Italian folk songs from my cousins, but I don’t think any instruments. I know I wanted to take the music class in grade school. But the only instrument they had available would have been the trombone, and my parents said no!

Understandable. But then you sort of bring back the trombone form with the molimo.

Yeah—but you know I have a trombone!

I didn’t know that!

And the way I’ve used it has been, when I did a piece with a lot of people, and we made a lot of observations of animals in the zoo, I used it as the lion roar, so it was like WAUUGHHHHH, WAUUGHHHHH, WAUUGHHHHH. (laughter).

That’s amazing! Yet on the works that you performed [in the video], that were also on the album [Al Di Là] on Saltern, you mostly avoid any kind of traditional instrumentation. I wonder when you first decided on objects that were more like…piping, and a pan of nails, as opposed to, say, the trombone.

Well, the house I grew up in with my parents, there was almost no music. My sister used to listen to the radio, to something called The Hit Parade…

I know that!

But I didn’t grow up hearing music. I’m sorry about that. But there were art books, lots of books of reproductions—mainly Renaissance and Impressionism—so I had a sense of aesthetic. I knew I liked art, but I didn’t hear much music. Then, when I started making things, in my twenties, I was more aware of [people like] John Cage and Marcel Duchamp. So I felt that I was allowed, that I had a green light on putting things together however I wanted. So, just because I didn’t know music, and couldn’t read music, and couldn’t play any traditional instruments, it didn’t mean that I couldn’t use sound.

I love that idea, and that there seems to be an element of egalitarian access, because of course musical instruments and musical lessons, etc. are very expensive.

Mmmmmmhmmmm.

Whereas you use objects that I could go to the hardware store and buy and play now. A little bit of a left turn: This performance that you’ve documented, and will be releasing, is going to make these works available to a lot more people. But I know that it’s not the first time that you’ve captured yourself in motion. That was in the 1970s, in the amazing holography works with Lloyd Cross. Would you mind sharing how that came about?

I was married to Peter van Riper, and he was very good friends with Lloyd. Peter thought it would be great if Lloyd and I got together on a project, so I applied, I think, to the New York Arts Foundation, and got a grant for a collaborative project. I think I saw my role in the making of the holograms as, in a way, coming up with a movement haiku: a very small phrase of movement that held its own.

Wow.

Lloyd was developing… what does he call it? Anyway, I call it animation holography, because it’s a series of holograms of frames of a 35mm film. So, with each frame, you see movement.

How do you feel that performance art differs on film or on video than in person?

I think they’re fundamentally different! For one thing, I’m an improviser, basically. I improvise within a certain… form, let’s say, but in a live performance, you’ve got that excitement. You don’t know if it’s going to work, you don’t know if you’ll get inspired. In a video, you’ve got that secured. “Oh yeah, they’re showing it as a video, so it must be good.” (laughs).

I’ve seen Censor performed a couple of times now, and I’ve noticed that, when it’s over, often both the performers and the audience start laughing. It’s a work that seems to exhilarate people. How did Censor come about?

I was living in New York, and riding the subway. I think it was at 14th Street, the train always made a very loud screech, and at least once, I just sang as loud as I could, while the train was screeching. I felt free to do that, because—I don’t know if I could say that no one could hear me—but it just happened so fast, and I sang very loud, and I got away with it! Nobody seemed to think that was weird.

It was also New York, so I’m sure they just assumed you were another—

And it was the 60s!

Another thing I was really taken by, when Julia Holter was performing Ocean Song, you started crawling across the room in the background…

(laughs) Yeah! Well, before she sang the Ocean Song, I believe I sang “Did We Fly To Earth or Will We Fly Away…”. [During that], I’m running in a figure eight, and then Julia starts singing. When I run in that figure eight, I’m working with this [successively sweeps her left and right arms outward] which is kind of a reptilian motion. I start out almost flying, and then I get to the ground, and then I’m crawling with the same basic motion, but adjusted. And I also like to surprise the audience, and I thought oh this will be good, I’ll crawl away! (laughter).

I do that figure eight as a study of movement, and to take it to the floor… I’ve done a lot of trying out, in my own body, the transition between being upright and being on all fours, and then being like a reptile, with the limbs to the side. I’ve done a lot of improvising, studying those transitions. So I would often get down to crawling. Crawling has been an important part of my movement vocabulary. But in this context, I knew it would be funny, and I like that.

It was! It was a very disarming moment. What I think I’ve come to appreciate more is the role that nature has always played in your work—nature and animals and natural forms—and it seems that New York is very antithetical to that. Did you feel that way?

Yes, I did feel that. I found it very difficult. I remember saying that everywhere my eye fell, was on something that had been designed and built by humans. I felt like I was in a room with walls made of mirrors, that the only nature was the force of gravity, and my own mass. I think that’s what part of influenced those Dance Constructions. Especially Accompaniment for La Monte’s “2 Sounds”, where you’re standing on a rope, but it’s suspended. So you feel the weight of your body, and that’s enough.

That reminds me of you saying that crawling and being low to the ground have always been very important to your work. That strikes me as being very similar.

Yes, and also part of my study of crawling was an interest in how we made the transition from being on all fours to being standing upright, exploring how you can be striding along or be crawling along, and then start to get up without breaking your pace, without breaking your rhythm. You can go from up to down to up, with your limbs splayed out to the side like a reptile, and then the limbs get under you, and then you get up. So I was studying that, and then going to the Natural History Museum, to see how the bones had changed during those transitions, and looking at animals in zoos to see how different animals moved because [of the differences in their bodies]. I was interested in my movement, just naturally, without stylisation.

I realised how much of your work really concerns the feelings and experiences of the dancer; rather than considering the dancer from the outside, it’s about what the dancer or performer is feeling. Has that always been important to you?

I think so, and I think it’s of concern that when the audience member is looking at me, that they are able to get just a taste of what I’m feeling, that they can feel what I feel. I remember being a child in Los Angeles, and being brought to see the Bolshoi Ballet. I especially remember a piece in the program that was very exuberant and very energetic. I was sitting in the audience, but my legs would kick out without my meaning to do it. It was happening in me. That’s the kind of thing I like. I mean, I haven’t done a lot of exuberant high kicks! (laughter). But when I’m crawling and literally feeling my weight on the ground, I feel that’s a chance for an audience member to really feel their weight on the ground.

Was that your first memory of seeing dance, the Bolshoi Ballet?

It might be!

And did you already have any inclination that you’d want to work with dance, at that point?

I don’t think so, although I knew I wanted to be an artist of some sort. There were the art books in the house. Father read a lot of philosophy, and history, and art criticism, but I wasn’t interested in that, and mother read the Reader’s Digest. So reading wasn’t really offered to me—but art, visual art; I’d pore over those books.

In a similar way to wanting the audience to feel what you experience, it also strikes me that, with the Hippie Gospel Songs, and working with your own drawings and journals, that there’s a very porous boundary between your memories and personal life, and your artistic life. Do you feel that your own memories are the main material for your performance pieces?

I think, for me, a very personal connection comes naturally. I don’t have that distance.

So you would say that most of your works do connect to memories or experiences you’ve had in your personal life, or day-to-day life?

That’s an interesting question. Things I do… yes, looking at the animals, for instance. There was the looking at the animals, but the reason I was doing that had a lot of personal stuff in it. It’s interesting, but that started—the looking at the animals—when I was in Rome, and I just happened to be in an apartment near the zoo. I’d also just gone through a bad breakup. So, I’d go hang out with the animals, and they were sad, and I was sad! (laughter).

Oh, that’s so sad!

But that had a lot to do with it. I felt better when I was there. Then, many years later, with the moving and speaking, and working with the news—that was out of a need to understand the news. Partly because my father had died, and he always read the newspaper. So, when I had a newspaper in front of me, like an LA Times, the paper itself was comforting. The feel of the paper, but also getting interested in what Father had been interested in, and also feeling that I should understand things because Father wasn’t there anymore to understand what was going on, and when it was time to pack up and run for the hills.

It seems like a lot of these are connected to pretty sad times…

Yes! I’ve found that sad times have really inspired me.

Well, it’s hard to imagine a sadder time than right now…

Oh, well, I keep treasuring these days before the election! But, for instance, I’ve been really trying to focus on writing. And I think that comes, to a great extent, from having gotten Parkinson’s. That cut me off from how I had been functioning, and I had to find another way.

Right, so do you feel that, when your relationship to your body changed, that the flow almost diverted?

Yes!

Do you mind if I ask what you’ve been writing about?

I’ll recite a poem to you.

Oh, I’d love that!

It’s from the lockdown:

These days bunched together like bananas

Bland, like dizzy spells

That’s it!

That’s lovely, and incredibly accurate! I don’t know if I can follow that up!

Well then I’ll plug something! I have a few poems in the latest issue of PEAK Performances Journal, which just came out. That was the shortest one, that I just recited, but if you go to PEAK Performances, I’m one of three artists that are featured this month.

Watch Al Di Là: An Evening of Sound Works on Vimeo (Part 1 | Part 2). Download Fool on the Hill and Italian Folk Song (1968) at Bandcamp. Purchase Al Di Là at Bandcamp.

Thank you for reading the thirty-ninth issue of Tone Glow. Bunch together.

If you appreciate what we do, please consider donating via Ko-fi. Tone Glow is dedicated to forever providing its content for free, but please know that all our writers are paid for the work they do. All donations will be used for paying writers, and if we get enough money, Tone Glow will be able to publish issues more frequently.

Beautiful interview. Greetings from México.